20

INTELLIGENCE TESTING OF NEW IMMIGRANTS

Mental tests: such a simple and accurate means of rating human intelligence, even, as Robert Yerkes, a leading tester claimed, of appraising “the value of a man.”1 Once Henry H. Goddard had imported Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon’s mental tests into the United States, it became apparent that their usefulness reached far beyond their limited role in France. There, the tests designated schoolchildren for special education; in the United States, they rated the children at the Vineland school for the feebleminded and then went on to serve other, much wider purposes. Officials at Ellis Island figured Goddard’s tests in Vineland could help them decide who, among immigrants streaming into the country, could stay and who had to return.

What were these tests like? In 1917 masses of U.S. Army draftees who could read answered questions like these:

Why do soldiers wear wrist watches rather than pocket watches? Because

they keep better time.

they keep better time. they are harder to break.

they are harder to break. they are handier.

they are handier.

Glass insulators are used to fasten telegraph wires because

the glass keeps the pole from being burned.

the glass keeps the pole from being burned. the glass keeps the current from escaping.

the glass keeps the current from escaping. the glass is cheap and attractive.

the glass is cheap and attractive.

Why should we have Congressmen? Because

the people must be ruled.

the people must be ruled. it insures truly representative government.

it insures truly representative government. the people are too many to meet and make their laws.2

the people are too many to meet and make their laws.2

Men who could not read answered pictorial questions. Soldiers were to say what was missing from each picture:3* (See figure 20.1, “Test 6.”)

Fig. 20.1. “Test 6,” in Carl C. Brigham, A Study of American Intelligence (1923).

Testers aimed high, promising to measure innate intelligence, not simply years of education or immersion in a particular cultural milieu. This claim was obviously absurd, but no matter. The allure of mental testing proved irresistible, because demand for ranking people was high, and the process was cheap and, best of all, apparently scientific. The juxtaposition of congressional mandates and the ambitions of early twentieth-century social scientists explains how Goddard went from degenerate families to intelligence testing of immigrants.

NATIVISTS HAD long denigrated immigrants on the grounds of their supposed inferiority. Prescott Farnsworth Hall, one of the then recent Harvard graduates founding the Immigration Restriction League in 1894, mashed together degenerate families, immigrants, and competitive breeding: “The same arguments which induce us to segregate criminals and feebleminded and thus prevent their breeding apply to excluding from our borders individuals whose multiplying here is likely to lower the average of our people.”4 This logic steadily gained ground.

From the 1890s onward, federal legislation toughened standards for excluding “lunatics,” “idiots,” people likely to become public charges, the insane, epileptics, beggars, anarchists, “imbeciles, feeble-minded and persons with physical or mental defects which might affect their ability to earn a living.”5 But with five thousand immigrants passing through Ellis Island daily, sorting through them imposed an impossible task on ten or so Public Health Service physicians. Something had to be done. Learning of Goddard’s methods, the commissioner of immigration concluded that help lay at hand right there in New Jersey. He invited Goddard to use his newfangled intelligence tests to speed up the exclusion process, an assignment Goddard carried out with the help of his lady testers from Vineland.6* Certain alarming conclusions leaped off the pages of Goddard’s report:

The intelligence of the average “third class” immigrant is low, perhaps of moron grade….

Each test taken by itself seems to indicate a very high percentage of defectness. There is no exception to this….

The immigration of recent years is of a decidedly different character from the earlier immigration…. It is admitted on all sides that we are getting now the poorest of each race…. “of every 1000 Polish immigrants all but 103 are laborers and servants.”…

According to TABLE II. INTELLIGENCE CLASSIFICATION OF IMMIGRANTS OF DIFFERENT NATIONALITIES, 83 percent of the Jews, 80 percent of the Hungarians, 79 percent of the Italians, 87 percent of the Russians were feebleminded. Sixty percent of the Jews were morons.7

In sum: most of the immigrants currently passing through Ellis Island were mentally defective. With this crucial point made and quantified, intelligence testing took a further step, as the new field of psychology seized wartime opportunities.

By 1917 Goddard had joined a new group of immigration opponents who had no connection to charitable institutions. Based in academia, Robert Yerkes and Lewis Terman did not associate with the poor or feel concern for their well-being. As scholars, they shaped their truths—drawn, they said, from science—toward their preferred results. Not compulsory sterilization this time, but the classification of the American population according to intelligence and race on the basis of quantifiable methodology. Once again, Charles Benedict Davenport of the Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor, New York, supplied the missing link.

In the prewar years, Davenport’s institution had diligently compiled hereditary studies of defective families. His statistics dovetailed nicely with omnibus characteristics Davenport considered Mendelian unit traits: pauperism, low intelligence test scores, epilepsy, criminalism, insanity, height, and sexual immorality. While the First World War interrupted such degenerate-family work and sterilization, wartime conscription presented eugenicists with great new opportunities in mass mental testing. Robert Yerkes (1876–1956), Davenport’s erstwhile student at Harvard, moved to the fore.

Yerkes was no vaunted New Englander. His humble provenance does not get much attention from his biographers, in stark contrast to works by and about proud Yankees like Davenport. Perhaps in an elite environment, his farm-boy background contributed to his early reputation for ordinary intellectual ability, coupled with rigidity, stubbornness, and a tee-totaler’s lack of bonhomie. Indifferent to wealth, power, fame, popularity, and personal beauty, he was not the sort to win popularity polls. Born on a farm in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, Yerkes had attended an ungraded rural school, then the State Normal School at West Chester, where Goddard had begun his professional career. With the support of an uncle willing to trade tuition money for chores, Yerkes was able to transfer to Ursinus College, in the greater Philadelphia area, before going on to Harvard, where he took an A.B. in 1898 and a Ph.D. in 1902.8 Once again, the nation’s most prestigious center of learning would play a pivotal role in race theory.

Harvard’s importance in eugenics does not imply some nefarious scheme or even a mean-spirited ambiance. Rather, Harvard’s import in this story attests to the scholarly respectability of eugenic ideas at the time. Yerkes’s most influential teachers at Harvard were the German philosopher Hugo Münsterberg—a great believer in the importance of mental testing, ranking people hierarchically, and letting elites make society’s decisions—and Charles Benedict Davenport, that venerator of Francis Galton.9

Yerkes began teaching at Harvard in 1902 and published his first book in 1907. Entitled The Dancing Mouse and the Mind of a Gorilla, it dealt with animal sexuality considered in the light of evolution.10 He also worked half-time at the Boston Psychopathic Hospital alongside the esteemed Elmer Ernest Southard, inventor of “cacogenics,” the clumsily named study of racial deterioration. Yerkes and Southard started administering mental tests in 1913, just when Goddard began testing immigrants on Ellis Island. Yerkes’s rise was rapid—he was elected president of the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1916—but it was also uncertain, since he had been denied tenure at Harvard, which evidently held a low estimate of the new field of psychology.11 An odd situation.

As president of the APA, but still lacking tenure, Yerkes chafed at his field’s lack of scholarly standing. Not that the prejudice lacked merit. Still separating from philosophy in the 1910s, psychology seemed soft and lacking in scholarly rigor. The beautifully quantified results of mental testing, so Yerkes and others realized, offered a promising route to academic respectability. As the United States prepared to enter the First World War, Yerkes sought to extend intelligence testing to millions of servicemen. Such a mass of statistical data, unique in its comprehensiveness, would doubtless command respect in academe.

But gathering a data bank of this magnitude would obviously be a huge undertaking. Yerkes found a route in the National Academy of Sciences, which in 1916 created the National Research Council to bring scientists into the war effort. In May of 1917 Yerkes convened a committee of testers that included Goddard and Lewis Terman of Stanford. Working at Goddard’s Vineland Training School, the team had by July 1917 created three sets of tests for use on Army recruits.12 The Army Alpha was directed toward men who could read; the Army Beta served illiterates; and individual tests filled in where needed in special cases—in theory, at least.

When the project closed down in January of 1919, some 1,750,000 men had been tested, generating a huge body of data and further encouraging wide-scale use of intelligence tests. Before the war, intelligence testing had sometimes inspired ridicule, not infrequently as leading citizens tested out as imbeciles. The patina of science, however, had carried the day, securing the Army tests’ role as science’s last word on intelligence. This prestige was something new. That word contained overweening ambition. Henry Goddard kindly pronounced intelligence testing “the most valuable piece of information which mankind has ever acquired about itself…a unitary mental process [that is] the chief determiner of human conduct.”13

In a 1923 Atlantic Monthly article Yerkes confidently assumed that intelligence testing could gauge much more than mental capacity. The tests, he maintained, could determine a man’s entire human worth. Yerkes was thinking about the immigrants who, he thought, diminished the effectiveness of the Army and, by extension, the overall health of American society: “Whereas the mental age of the American-born soldier is between thirteen and fourteen years, according to army statistics, that of the soldier of foreign birth serving in our army is less than twelve years….” These numbers would echo loudly in hereditarian circles. Yerkes warned of the recently arrived foreign-born, “Altogether they are markedly inferior in mental alertness to the native-born American.” He explained that differences between the white racial groups were “[a]lmost as great as the intellectual difference between negro and white in the army.”14 Once again, a scientist was speaking of “white racial groups” as a means of classification.

OVERALL, YERKES’S testing project pegged the average mental age of recruits at least eighteen years old at 13.08 years—accurate, it was claimed, to the second decimal place, though nonsensical as arithmetic: how could the average be below average? No matter. For Yerkes, with his unit-trait-unalterable-inherent-mental-ability concept of intelligence, this meant no further intellectual growth was possible, for the tests revealed innate native intelligence. Nothing in life after birth would make any difference whatsoever, not heightened language facility, more effective schooling, or increased familiarity with American culture. Furthermore, mental worth varied by race, as the term was understood in the early twentieth century: as a categorization applicable to peoples from various parts of Europe and its outlying areas. Yerkes and his colleagues drew many lines of race within the American population; one of the deepest separated so-called natives, whose ancestors had immigrated long ago, from recent arrivals.

Not that all was clear sailing. The Army, with war needs uppermost, never supported the testing project, and training procedures aimed at making effective soldiers severely interfered with the tests’ administration. Officers complained that men given the Beta tests’ two lowest grades, D and E, frequently turned into excellent soldiers once taught to read. Another commander dismissed the psychologists as a needless “board of art critics to advise me which of my men were the most handsome or a board of prelates to designate the true Christians.”15

OUTSIDE THE Army, however, intelligence testing succeeded spectacularly. After the war, Yerkes stayed on in Washington, D.C., into the mid-1920s, then moved on to his own laboratory at Yale, where he made a brilliant career in primate research. The National Academy of Sciences’ official report of Yerkes’s Army IQ tests, an unreadable, 890-page document featuring many charts and diagrams, reached only a tiny readership of specialists.16 In light of the controversy over immigration then raging, Yerkes encouraged one of the team of Army IQ testers, his protégé Carl Campbell Brigham of Princeton, to publish a readable digest for the general public.

Like many scholars seeking to place intelligence tests, eugenics, and race on a scientific basis, Brigham (1890–1943) sprang from prosperity and lofty New England breeding. He especially savored his descent from a signer of the Mayflower Compact in 1630. “Socially gifted,” according to his admiring biographer, Brigham “retain[ed] throughout his life the poise, bearing, and social graces derived from the environment of an old and esteemed New England family.”17 Toward the end of his undergraduate career, Brigham fell under the spell of the new methodology of mental tests. His well-regarded 1916 Ph.D. dissertation on the use of Binet tests on Princeton schoolchildren earned him an appointment on the Princeton University faculty. In 1917 Robert Yerkes discovered Brigham’s work and enlisted him to help administer intelligence tests to Army recruits.18

After the war Brigham rejoined the Princeton faculty, plunging once more into mental testing. Testing was now quite popular among educators as a means of ranking college applicants, and among nativists as scientific justification for cutting off immigration from southern and eastern Europe. The cause enjoyed prestigious support. Madison Grant and Charles W. Gould, two wealthy lawyers and Yale alumni, friends and eugenic opponents of immigration, underwrote Brigham’s project of putting Yerkes’s findings in accessible form for general readers, including, not least, members of Congress.19*

Princeton University Press published Brigham’s A Study of American Intelligence in 1923. Robert Yerkes wrote the foreword, assuring readers “no one of us as a citizen can afford to ignore the menace of race deterioration or the evident relations of immigration to national progress and welfare.” Brigham, Yerkes contended, was presenting “not theories or opinions but facts.”20

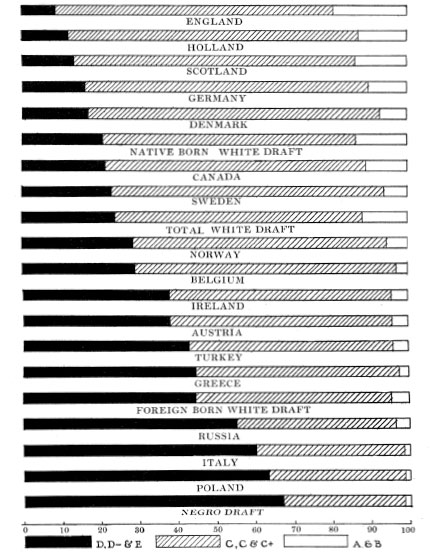

A Study of American Intelligence displayed an abundance of charts and graphs. Brigham divided the population into nearly a score of categories and illustrated numerous relative mental ages: atop the scale, American officers rated a mental age of 18.84 years; at the bottom, “U.S. (Colored)” came in at only 10.41 years. Native white Americans were roughly halfway between the two, achieving a mental age of 13.77 years, lower than immigrants from England, Scotland, the Netherlands, and Germany.21 Native American Indians and Asians did not count.

A dramatic bar graph arranged according to low scores compared racial and national groups in another way, with A the highest, C the average, and E the lowest score (see figure 20.2, Brigham’s bar graph.) Lumping black men of all backgrounds into a single unit, Brigham was respecting the traditional American black white dichotomy. At the same time, he distributed white people across nineteen overlapping categories reflecting current antagonism toward immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. His four major groups consisted of native-born whites, total whites, foreign-born whites, and Negroes. Within these groups, Brigham differentiated between the above-average foreigners and the below-average foreigners. Turks and Greeks just barely improved on the foreign-born average, while men from Russia, Italy, and Poland ranked at the bottom with the “Negro draft.” Northwestern Europeans topped the chart.22

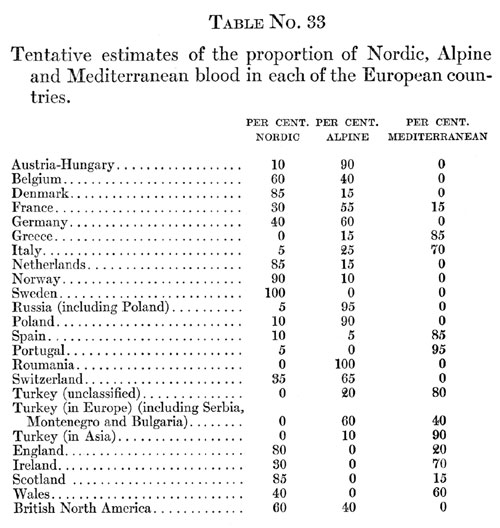

Among Brigham’s noteworthy illustrations was table 33. (See figure 20.3, Brigham’s “Table No. 33.”) This feat of statistics achieved the seemingly impossible task of reconciling the racial groups (William Z. Ripley’s still influential Races of Europe classification of Teutonic, Alpine, and Mediterranean on the basis of cephalic index) with the Immigration Service’s national origins assigned to immigrants.

It is not by accident that Brigham substitutes “Nordic” for Ripley’s “Teutonic,” because Brigham owed a substantial debt to Madison Grant’s Passing of the Great Race, or The Racial Basis of European History. First published in 1916, substantially revised in 1918 and in 1921, The Passing of the Great Race sold well over a million and a half copies by the mid-1930s. Grant uses “Nordic” instead of “Teutonic” in order to include Irish and Germans within the superior category but not Slavs, Jews, and Italians.23

Fig. 20.2. Brigham’s bar graph of mental test results, in Carl C. Brigham, A Study of American Intelligence (1923).

This astonishing table offers nonsensical estimates of national “blood,” presumably on the basis of cephalic indices, without explaining its methodology, which Brigham drew from one of eugenicists’ favorite theorists, Georges Vacher de Lapouge. Lapouge had displayed a similar table showing “proportions of blood” according to cephalic indexes in several countries (distinguishing northern Germans from southern Germans) in his L’Aryen: Son rôle social (The Aryan: His Social Role) in 1899.24* For his part, Brigham in 1923 tabulated the (European?) population of “Russia (including Poland)” at 5 percent Nordic and 95 percent Alpine, while “Poland” is 10 percent Nordic and 90 percent Alpine. With three different subject lines, Turkey is 40, 80, and 90 percent Mediterranean, as though its regions could be demarcated according to “blood” and nobody ever migrated anywhere. Ireland and Wales are 70 and 60 percent Mediterranean, while England is only 20 percent Mediterranean. The high Mediterranean percentages allotted to Ireland and Wales presumably reflect the racist assumptions of John Beddoe and William Z. Ripley that the Irish and Welsh belong to a more primitive and therefore shorter, darker, and long-headed population than the English. After a war in which Germans had been stereotyped as “the Hun,” German “blood” was downgraded from heavily Nordic to majority Alpine. Given the value judgments assigned to “Nordic,” “Alpine,” and “Mediterranean,” table 33 emerges as an exquisite example of scientific racism, one of a series of attempts to combine “blood” with nation. This table intrigued social scientists, whether accepting or skeptical.

Fig. 20.3. Brigham, “Table No. 33. Tentative estimates of the proportion of Nordic, Alpine and Mediterranean blood in each of the European countries,” in Carl C. Brigham, A Study of American Intelligence (1923).

In 1911 the U.S. Immigration Commission, under Senator William P. Dillingham of Vermont, had issued the Dictionary of Races or Peoples, a handbook intended to clear up the “true racial status” of immigrants, on the basis of Ripley’s Races of Europe and reprinting many of his maps. Like Ripley, Dictionary of Races or Peoples appealed to questionable authorities like Lapouge and his German anthroposociologist colleague Otto Ammon.25 Like most attempts to codify racial classification, the Dictionary of Races or Peoples tried to reconcile the warring categories of several different experts through lists of “race,” “stock,” “group,” “people,” and Ripley’s and other scholars’ races. Its mishmash of categories had left open the gap that Brigham tried to fill.

In addition to these European racial “blood” measurements, Brigham reinterpreted the correlation between immigrant test scores and length of residence in the United States. As might be expected, given the questions, the longer immigrants had resided in the United States, the higher their scores. But Brigham followed Yerkes’s reasoning, noting, then rejecting, the obvious causal relationship:

Instead of considering that our curve…indicates a growth of intelligence with increasing length of residence, we are forced to take the reverse of the picture and accept the hypothesis that the curve indicates a gradual deterioration in the class of immigrants examined in the army, who came to this country in each succeeding five year period since 1902.26

In other words, immigrants who had been in the United States longer scored higher because they were inherently smarter, the cream of the crop, as it were, self-starters who had set out from the old country early on, while the way was still hard. Later arrivals had no such pluck. They scored lower because they belonged to inferior races who let shipping companies deliver them the easy way across the ocean. Anthroposociology’s cockamamie notions about headshape differences between urban and rural dwellers were now applied to conditions in the United States.

ARRIVING IN the jittery postwar era, Study of American Intelligence enjoyed a wide popularity that overwhelmed a few critical reviews in liberal journals. Brigham’s credibility rode on a handsome set of advantages—his Princeton Ph.D., his Princeton University Press publication, his Princeton faculty position, and financial backing from Grant and Gould. With this kind of high-level support, his book enjoyed much currency in the early 1920s as scientific proof that immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were as inherently defective as whole races of Jukes and Kallikaks. The idea played well in a country—and its Congress—roiled by economic, political, and social unrest.*