The mission: To create a flavored gel in a range of textures from firm and moldable to smooth and spoonable. Unlike other applications in this book, these gels are set and held in place primarily by the coagulative power of egg yolks. Due to the particular nature of the egg, particular procedures must be observed.

The word “custard” comes from the Anglo-French crustade, which in turn comes from the Latin crusta (from which we also get “crust”). What’s most interesting to me is the word’s relationship to the Greek crysta or “crystal.”

An egg can thicken a liquid in two ways. It can emulsify it with fat, as is the case with mayonnaise and hollandaise, or it can thicken by capturing the liquid (particularly dairy products) in a mass of coagulated protein molecules. When the latter is the case we call the result a custard. A surprising number of common culinary applications are indeed custards, including quiche, most puddings and ice creams, curds, various dessert sauces like zabaglione, various savory sauces, cheesecake, and good ole pumpkin pie.

Despite the custard’s limitless incarnations, all custards are either stirred or still. Both spring from similar shopping lists, but when it comes to procedures, differences abound.

Egg yolks: Freeze the leftover egg whites in ice-cube trays. After the whites are frozen, place the frozen cubes into zip-top freezer bags. The frozen whites can be kept up to a year. What to do with them? See Baked Meringue Pie Crust, here.

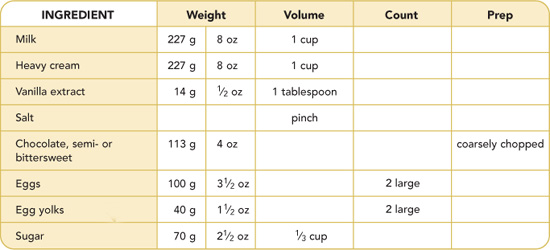

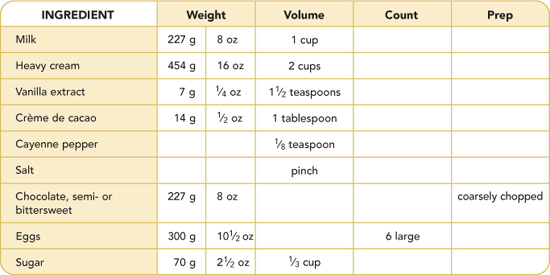

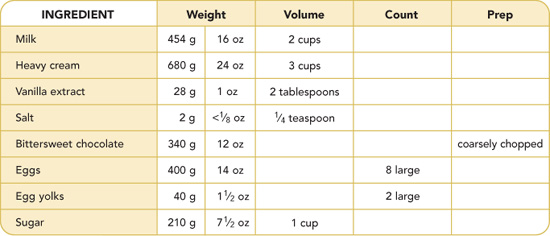

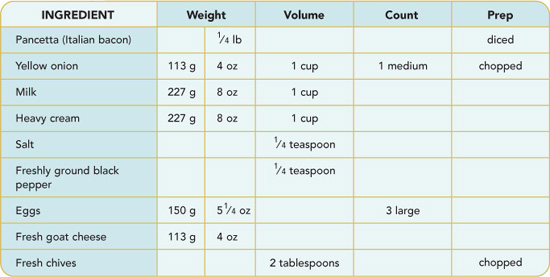

The first list is for a baked (still) pudding, the second for an ice cream (stirred). (When I used the term “stirred” here, I’m not talking about the churning or freezing of the ice cream, but the stirring that goes on during the actual cooking of the custard.) And yet, they are very similar: the ice cream has a third more dairy, twice as much chocolate, and a third more eggs than the pudding. The amounts of liquid flavorings are essentially the same and the sugar amount is identical. So although there are differences here, these applications are still next-door neighbors.

Most of the ingredients added to bring the pudding list up to the ice cream list are there because—although ice cream is indeed a custard—when finished, it will be a custard full of ice. One of the reasons there’s more dairy in the ice cream is that some of the moisture will be bound up in the custard’s protein matrix and some will be turned into ice crystals. Added fat in the form of chocolate and eggs will help to combat the gritty mouth feel that cheap ice creams have. And the added chocolate and the liqueur help make up for the fact that cold greatly turns down the volume on our taste buds. (If you don’t dig chocolate-flavored liqueur, go with an equal amount of coffee-flavored liqueur.) The cayenne in the ice cream is just a little thing I’m fond of. (Okay, so you’re wondering what’s up with the fire powder. Well, it’s an Aztec thing. They mixed hot chiles into their cocoa. The Aztecs may have gotten a few things wrong (blood sacrifices, trusting Europeans with guns), but this they nailed. It’s a great combo and as much as I know you’re going to be tempted to leave it out—just try it, you’ll like it. And if you don’t, I’ll eat your custard.)

Combine the cream and the milk in a heavy saucepan, and add the vanilla and other flavorings. Scald over low heat.

Combine the cream and the milk in a heavy saucepan, and add the vanilla and other flavorings. Scald over low heat.

Add the chocolate and stir to melt.

Add the chocolate and stir to melt.

Set aside.

Set aside.

Whisk the eggs and any additional yolks until light, then whisk in the sugar. Giving the yolks a good beating helps them get ready to denature and breaks up some of those bonds that keep them so darned self-contained. Think of it as a pre-game warm up.

Whisk the eggs and any additional yolks until light, then whisk in the sugar. Giving the yolks a good beating helps them get ready to denature and breaks up some of those bonds that keep them so darned self-contained. Think of it as a pre-game warm up.

Many, nay most, custard recipes call for dissolving the sugar in the milk. I don’t. I add it to the eggs because the sugar will help prevent curdling. On the other hand, I can find no advantage whatsoever to adding the sugar to the dairy.

Slowly temper (see here) the chocolate/milk mixture into the egg mixture.

Slowly temper (see here) the chocolate/milk mixture into the egg mixture.

Only at this point, when the custard is essentially built, do the paths diverge.

Place a oven rack at position B and heat the oven to 300°F.

Place a oven rack at position B and heat the oven to 300°F.

Place six 6-ounce custard cups in a roasting pan or large metal baking pan.

Place six 6-ounce custard cups in a roasting pan or large metal baking pan.

Bring a pot of water to a boil.

Bring a pot of water to a boil.

Strain the custard through a fine-mesh sieve into the custard cups, filling each cup 3/4 full. (Straining is necessitated by those pesky chalazae—the little bungee cords of egg white that keep the egg yolk centered in the egg. They don’t dissolve, they just get hard and nasty.)

Strain the custard through a fine-mesh sieve into the custard cups, filling each cup 3/4 full. (Straining is necessitated by those pesky chalazae—the little bungee cords of egg white that keep the egg yolk centered in the egg. They don’t dissolve, they just get hard and nasty.)

Open the oven door and rest the metal pan on it. Pour enough hot water into the pan to come halfway up the sides of the custard cups.

Open the oven door and rest the metal pan on it. Pour enough hot water into the pan to come halfway up the sides of the custard cups.

Carefully set the metal pan onto the oven rack and bake for 25 to 30 minutes, until the custards are set but still a bit wobbly. (The internal temperature will be between 160° and 165°F.)

Carefully set the metal pan onto the oven rack and bake for 25 to 30 minutes, until the custards are set but still a bit wobbly. (The internal temperature will be between 160° and 165°F.)

Using tongs, remove the cups from the pan to a kitchen-towel–lined sheet pan. Allow the water in the roasting pan to cool before discarding.

Using tongs, remove the cups from the pan to a kitchen-towel–lined sheet pan. Allow the water in the roasting pan to cool before discarding.

Allow the pudding to cool to ambient room temperature, then refrigerate for a minimum of 2 hours before serving.

Allow the pudding to cool to ambient room temperature, then refrigerate for a minimum of 2 hours before serving.

Pour the mixture back into the pot, place over low heat, and bring to 170°F, (If you have a candy/fry thermometer, this would be a good time to clamp it on the side of the pot. If you don’t have one or just don’t want to bother, use your trusty Thermapen instant digital thermometer. (Don’t have one? Just drop by www.Thermoworks.com. They have plenty.)) stirring often.

Pour the mixture back into the pot, place over low heat, and bring to 170°F, (If you have a candy/fry thermometer, this would be a good time to clamp it on the side of the pot. If you don’t have one or just don’t want to bother, use your trusty Thermapen instant digital thermometer. (Don’t have one? Just drop by www.Thermoworks.com. They have plenty.)) stirring often.

Remove from heat and strain through a fine mesh sieve.

Remove from heat and strain through a fine mesh sieve.

Cool to ambient room temperature, then chill in the refrigerator for at least 4 hours, overnight if possible.

Cool to ambient room temperature, then chill in the refrigerator for at least 4 hours, overnight if possible.

(Here’s another mystery for you. No one really knows why this aging or “mellowing” process renders better results. Again, it could be a protein thing, or a sugar thing, or a fat thing. Whatever kind of thing it is, it works. Aged ice cream mixtures are always smoother tasting and smoother melting than non-aged mixtures. If you can’t wait overnight, at least allow the mixture to get down to refrigerator temperatures. The colder the mix is when it goes into the churn, the faster it will freeze and the smaller the ice crystals inside will be—and therefore, the smoother the ice cream will be.)

Churn according to your ice cream freezer’s instructions. When the mixture has increased in size by a third and is very thick, move to an airtight container and harden in the freezer for at least four hours. Now by the way would be the time to stir in any chunks, like miniature pretzels or chocolate-covered cherries, or…well you get the idea. Of course, you could just let it go naked (not everything has to crunch, you know).

Churn according to your ice cream freezer’s instructions. When the mixture has increased in size by a third and is very thick, move to an airtight container and harden in the freezer for at least four hours. Now by the way would be the time to stir in any chunks, like miniature pretzels or chocolate-covered cherries, or…well you get the idea. Of course, you could just let it go naked (not everything has to crunch, you know).

Now, I know what you’re thinking. If you could settle on one application for making custard, then you could just make a big batch and split it, making pudding from one half and ice cream from the other. Then you’d have a veritable cornucopia of chocolaty pleasure.

I hear ya.

Although you’ll sacrifice a little on both ends with this application, odds are good that you and your loved ones will never notice the difference unless you taste samples side by side.

Bake half, turn half, have fun.

Bake half, turn half, have fun.

Of the myriad custard applications that follow, note that the first is a quiche, the classic interpretation of the custard that the French call a sauce royale. (Which should never be confused with a royale with cheese.) In this method, whole eggs are mixed with unscalded dairy and the resulting cold mixture is poured over solids and then baked. You’ll also find a zabaglione, which also involves no scalding or tempering.

Hardware for the Custard:

3 small glass bowls for separating eggs

Digital scale

Wet measuring cups

Measuring spoons

Chef’s knife

Cutting board

Large saucepan

Whisk

Wooden spoon

Fine-mesh sieve

Extra Hardware for the Pudding:

Six 6-ounce custard cups or ramekins

Roasting pan or metal baking pan

Tongs

Clean kitchen towel

Half-sheet pan or cookie sheet

Extra Hardware for the Ice Cream:

Airtight container

Ice cream freezer

MOST COOKS CAN TELL YOU that if eggs overcook, they curdle. That is, they scramble, forming tight curds of over-coagulated proteins. And while this is certainly true, it’s by no means the entire story. The real danger to eggs in custards is not being cooked too hot, but too fast. In fact, the more slowly you cook a custard, the better off you are.

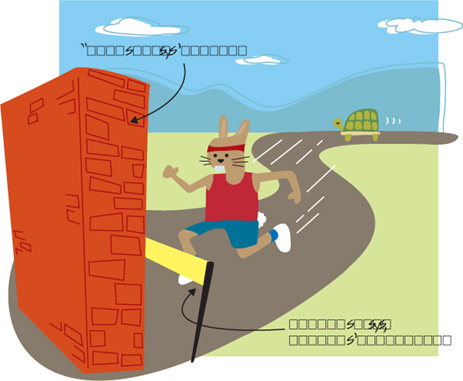

The higher the heat you use, the closer the set point (which you want to hit) and the over-coagulation point (which you want to avoid) are to each other. Imagine trying to win a foot race where the finish line is one foot from a brick wall. What are your chances of crossing the finish line and stopping before the wall? If you’re going fast, well…too bad. If you’re going slow, odds are you’ll be fine. And if that weren’t enough reason to back down on the heat consider this: the slower you cook eggs, the lower the setting point drops—and that means you have even more room between the finish line and the wall of pain and agony (not to mention rubbery curds).

With this truth in mind, just about every custard recipe known to man contains references to “tempering eggs” and the use of either a double boiler or a bain marie (or hot water bath), all of which are methods for slowing down heat.

Tempering is a method by which beaten eggs can be integrated into a liquid that—under any other circumstances—would be too hot for the eggs to be added to without curdling. The idea is to slowly rather than suddenly increase the temperature of the eggs.

1. While briskly whisking the eggs, slowly drizzle (or spoon, if it’s thick) 1/4 to 1/3 of the hot mixture into the eggs, then slowly whisk this mixture into the remaining hot mixture. This will not only slow the absorption of heat by the eggs, it will ensure that the proteins are diluted with other substances, such as sugar, and that will prevent them from reaching each other. The physical blocking of proteins by larger sugar molecules explains why a curd is so much easier to make than say, Hollandaise sauce.

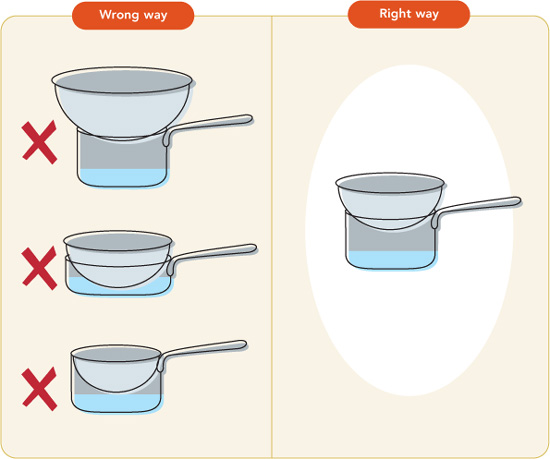

2. A double boiler prevents overheating or the rapid heating of stirred custards by isolating the mixture from the high heat of the cook top. Water is turned to steam and steam bathes the bottom of the vessel. Still, steam is hot stuff and near-constant stirring is necessary.

3. A bain marie, or water bath, is used to keep custards from heating too quickly in the oven. Since water cannot rise above 212°F at sea level this ensures that whatever the water is touching won’t rise above 212°F, even in a 350°F oven.

Moral: Slow and steady wins the custard race.

What the French call a quiche, we Americans might plainly call a refrigerator pie. One of the best ways I know to use up leftovers, a quiche can consist of any manner of cooked vegetables and meats, with a sauce royale (uncooked custard) poured over the top.

Hardware:

Digital scale

Wet measuring cups

Measuring spoons

Chef’s knife

Cutting board

Non-stick frying pan

Medium saucepan

Small mixing bowl

Whisk

Wooden spoon

Cooling rack

Prepare the Basic Pie Dough according to the instructions here.

Prepare the Basic Pie Dough according to the instructions here.

Place an oven rack in position C and preheat the oven to 425°F. Roll out the dough to fit a 9-inch pie pan, pinch the edges, and discard excess dough. Blind bake the crust for 15 minutes. Set the baked crust aside and turn the oven down to 350 degrees.

Place an oven rack in position C and preheat the oven to 425°F. Roll out the dough to fit a 9-inch pie pan, pinch the edges, and discard excess dough. Blind bake the crust for 15 minutes. Set the baked crust aside and turn the oven down to 350 degrees.

Cook the pancetta in a non-stick frying pan just until it starts to get crispy, about 5 minutes. Add the chopped onions to the pan with the pancetta and continue to cook until the onions are translucent and the pancetta is really crispy, about 5 to 7 minutes longer. Set aside.

Cook the pancetta in a non-stick frying pan just until it starts to get crispy, about 5 minutes. Add the chopped onions to the pan with the pancetta and continue to cook until the onions are translucent and the pancetta is really crispy, about 5 to 7 minutes longer. Set aside.

In a medium-sized saucepan placed over low heat, combine the milk, cream, salt, and pepper and heat to just under a simmer. Remove from the heat and set aside.

In a medium-sized saucepan placed over low heat, combine the milk, cream, salt, and pepper and heat to just under a simmer. Remove from the heat and set aside.

In a small bowl, beat the eggs and then temper into the milk mixture (see here).

In a small bowl, beat the eggs and then temper into the milk mixture (see here).

Cover the bottom of the blind-baked piecrust with the pancetta and onions, and then slowly pour in the egg and milk mixture.

Cover the bottom of the blind-baked piecrust with the pancetta and onions, and then slowly pour in the egg and milk mixture.

Crumble the goat cheese over the mixture in small amounts, dispersing it evenly across the surface, then top with the chopped chives.

Crumble the goat cheese over the mixture in small amounts, dispersing it evenly across the surface, then top with the chopped chives.

Bake for 35 to 40 minutes, or until the internal temperature reaches 160° to 165°F. The center should still be wobbly.

Bake for 35 to 40 minutes, or until the internal temperature reaches 160° to 165°F. The center should still be wobbly.

Allow to cool for 15 minutes before serving.

Allow to cool for 15 minutes before serving.

Yield: Serves 6 to 8

The caramel will make a sauce when the custards are inverted.

Hardware:

3 small glass bowls for separating eggs

Digital scale

Wet measuring cups

Measuring spoons

Small saucepan

Medium saucepan

Eight 6-ounce custard cups or ramekins

Kettle

Large stainless-steel bowl with a spout

Whisk

Wooden spoon

Fine-mesh sieve

Roasting pan large enough to accommodate 8 custard cups with at least 1 inch to spare around

Clean kitchen towels

Paring knife

Tongs

Sheet pan

Place an oven rack in position C and preheat the oven to 350°F.

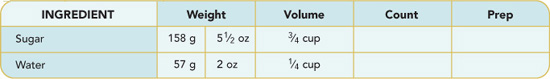

To make the caramel, place the 3/4 cup sugar in a small saucepan over medium heat. Sprinkle the water evenly over the sugar, swirling the pan to combine the sugar and water. Continue swirling until a clear syrup forms, about 3 to 5 minutes. Increase the heat to high and bring to a boil. Cover the pan and boil for 2 minutes. Uncover and continue to cook the syrup until it turns an amber color, 2 to 3 minutes. Quickly pour equal amounts of the syrup into the 8 custard cups.

To make the caramel, place the 3/4 cup sugar in a small saucepan over medium heat. Sprinkle the water evenly over the sugar, swirling the pan to combine the sugar and water. Continue swirling until a clear syrup forms, about 3 to 5 minutes. Increase the heat to high and bring to a boil. Cover the pan and boil for 2 minutes. Uncover and continue to cook the syrup until it turns an amber color, 2 to 3 minutes. Quickly pour equal amounts of the syrup into the 8 custard cups.

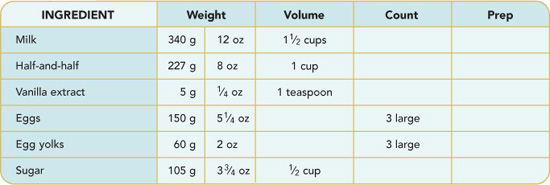

In a medium saucepan, combine the milk, half-and-half, and vanilla. Bring to a bare simmer over medium-low heat and then immediately remove from the heat and set aside.

In a medium saucepan, combine the milk, half-and-half, and vanilla. Bring to a bare simmer over medium-low heat and then immediately remove from the heat and set aside.

Set a kettle of water to boil.

Set a kettle of water to boil.

In a small bowl, whisk the eggs and the egg yolks until they have lightened in color. Slowly whisk in the 1/2 cup sugar and continue whipping until the mixture is slightly thickened.

In a small bowl, whisk the eggs and the egg yolks until they have lightened in color. Slowly whisk in the 1/2 cup sugar and continue whipping until the mixture is slightly thickened.

Temper the eggs into the milk mixture (see here).

Temper the eggs into the milk mixture (see here).

Place a fine-mesh sieve over a glass or stainless-steel bowl with a spout. Pour the milk-egg mixture through the strainer into the bowl.

Place a fine-mesh sieve over a glass or stainless-steel bowl with a spout. Pour the milk-egg mixture through the strainer into the bowl.

Place a clean kitchen towel in the roasting pan and put the custard cups on top. Evenly distribute the custard into the custard cups, going short on the first pass.

Place a clean kitchen towel in the roasting pan and put the custard cups on top. Evenly distribute the custard into the custard cups, going short on the first pass.

Open the oven door and rest the pan on it. Pour boiling water into the pan halfway up the sides of the cups and then carefully move the pan into the oven.

Open the oven door and rest the pan on it. Pour boiling water into the pan halfway up the sides of the cups and then carefully move the pan into the oven.

Bake for 40 to 50 minutes, or until the custards still wobble slightly when the pan is wiggled. You can also insert a paring knife midway between the edge and the center. If it comes out clean, the custards are done.

Bake for 40 to 50 minutes, or until the custards still wobble slightly when the pan is wiggled. You can also insert a paring knife midway between the edge and the center. If it comes out clean, the custards are done.

Using tongs, remove the cups from the pan to a kitchen towel–lined sheet pan. Allow the water in the roasting pan to cool before discarding. Cool, cover, and chill the custards for at least 4 hours. They will keep, refrigerated, for up to three days.

Using tongs, remove the cups from the pan to a kitchen towel–lined sheet pan. Allow the water in the roasting pan to cool before discarding. Cool, cover, and chill the custards for at least 4 hours. They will keep, refrigerated, for up to three days.

To serve, dip the cups into warm water and use a knife to loosen edges, then invert them onto serving plates.

To serve, dip the cups into warm water and use a knife to loosen edges, then invert them onto serving plates.

Yield: 8 servings

This is a nice, simple banana pudding that’s faster than the one on the back of the famous box simply because it’s not baked. That said, it does taste a heck of a lot better the next day. I should also note that this is one of the oldest recipes in the Brown family chronicles, or at least that’s what I’m told. The first time my grandmother made it for me she told me the recipe was written during the Revolutionary War. When I pointed out that Nilla Wafers weren’t invented until 1945, she took the entire pudding and gave it away to the minister who lived next door. That’s the last time I questioned the authenticity of a dessert—any dessert.

Hardware:

Digital scale

Dry measuring cups

Wet measuring cups

Measuring spoons

Chef’s knife

Cutting board

Two medium saucepans

Food processor

Small mixing bowl

Fine-mesh sieve

Large stainless-steel bowl

Whisk

Small clean plastic spritz bottle

9-inch square casserole or baking dish (Glass is best because it lets you see the wafers waiting for you in the bottom.)

(So why the flour? A lot of older pudding/custard recipes include starch to prevent curdling and to absorb any extra liquid that might seep out of the final matrix. Flour is a thickener too, but since this mixture never boils, the flour’s thickening power can never be fully released. Logic might lead you to believe you’d be better off with cornstarch—and that would be true if you planned to serve the pudding within a few hours, but come the next day your pudding would be soup. That’s because egg yolks contain an enzyme that gobbles up starch molecules. And although the eggs cook long enough to be considered cooked, they don’t cook long enough to turn off this enzyme.)

(One serving if it’s serving me.)

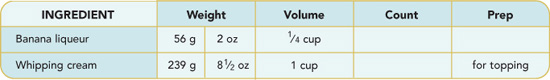

Banana Liqueur: Not part of the original recipe.

In a medium saucepan, bring about an inch of water to a boil, then reduce to a simmer.

In a medium saucepan, bring about an inch of water to a boil, then reduce to a simmer.

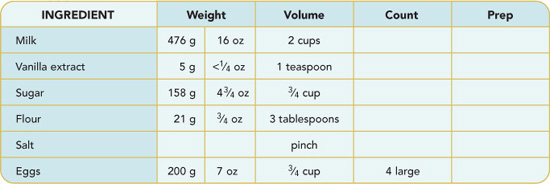

Meanwhile, in another medium saucepan, combine the milk and vanilla. Bring to a bare simmer over medium-low heat and then immediately remove from the heat and set aside.

Meanwhile, in another medium saucepan, combine the milk and vanilla. Bring to a bare simmer over medium-low heat and then immediately remove from the heat and set aside.

Place the sugar, flour, and salt in the bowl of a food processor, pulsing a few times to combine.

Place the sugar, flour, and salt in the bowl of a food processor, pulsing a few times to combine.

In a small bowl, whisk the eggs until they have lightened in color. Slowly whisk in the sugar-flour mixture and continue whipping until the mixture is slightly thickened.

In a small bowl, whisk the eggs until they have lightened in color. Slowly whisk in the sugar-flour mixture and continue whipping until the mixture is slightly thickened.

Temper the egg-sugar mixture into the milk mixture (see here) and then strain through a fine-mesh sieve into a stainless-steel mixing bowl.

Temper the egg-sugar mixture into the milk mixture (see here) and then strain through a fine-mesh sieve into a stainless-steel mixing bowl.

Set the bowl atop the saucepan over the barely simmering water, making sure the bottom of the bowl does not touch the water.

Set the bowl atop the saucepan over the barely simmering water, making sure the bottom of the bowl does not touch the water.

Whisk constantly for 15 minutes, until the temperature taken with an instant-read thermometer reads between 170° and 175°F. Remove from the heat and set aside.

Whisk constantly for 15 minutes, until the temperature taken with an instant-read thermometer reads between 170° and 175°F. Remove from the heat and set aside.

Line the casserole with the vanilla wafers, and if you’re feeling especially frisky, spritz them with banana liqueur. Spread on a thin layer of the custard, then a layer of the bananas. Repeat all the way to the top.

Line the casserole with the vanilla wafers, and if you’re feeling especially frisky, spritz them with banana liqueur. Spread on a thin layer of the custard, then a layer of the bananas. Repeat all the way to the top.

Chill for at least four hours (or preferably overnight) and then top with a layer of whipped cream (see here) before serving.

Chill for at least four hours (or preferably overnight) and then top with a layer of whipped cream (see here) before serving.

Yield: 8 to 10 servings

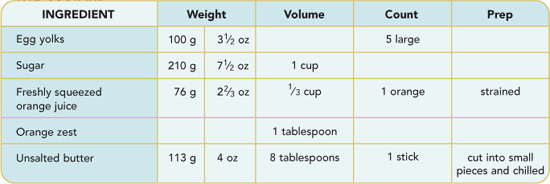

A custard based on citrus juice is usually called a curd. The most common of these is usually made with lemon juice, but orange juice provides a nice change here. And not only is citrus curd shamelessly easy to make, it may actually be the most versatile substance on earth besides duct tape. You can spread it on bread, biscuits, cake, fold it into soufflés, you name it. If you only know how to make one dessert item you might think about making it citrus curd.

Hardware:

3 small bowls for separating eggs

Digital scale

Dry measuring cups

Wet measuring cups

Measuring spoons

Chef’s knife

Juicer

Fine-mesh sieve

Rasp or citrus zester

Cutting board

Medium saucepan

Medium stainless steel bowl

Whisk

Kitchen spoon

1 pint bowl or container

Plastic wrap

In a medium saucepan, bring about an inch of water to a boil, then reduce to a simmer.

In a medium saucepan, bring about an inch of water to a boil, then reduce to a simmer.

Meanwhile, combine the egg yolks and sugar in a medium-size stainless-steel bowl. With a whisk, beat the eggs and sugar together thoroughly for at least 4 minutes. (This is essential—use a kitchen timer if you’re in doubt.)

Meanwhile, combine the egg yolks and sugar in a medium-size stainless-steel bowl. With a whisk, beat the eggs and sugar together thoroughly for at least 4 minutes. (This is essential—use a kitchen timer if you’re in doubt.)

Measure the orange juice. If a single orange has not given you enough juice, add enough cold water to reach 1/3 cup. Add juice and zest to the egg mixture and whisk until smooth.

Measure the orange juice. If a single orange has not given you enough juice, add enough cold water to reach 1/3 cup. Add juice and zest to the egg mixture and whisk until smooth.

Set the bowl atop the saucepan over the barely simmering water, making sure the bottom of the bowl does not touch the water.

Set the bowl atop the saucepan over the barely simmering water, making sure the bottom of the bowl does not touch the water.

Continue to whisk the mixture until thickened, about 8 to 12 minutes. The custard should be a light yellow and coat the back of a spoon.

Continue to whisk the mixture until thickened, about 8 to 12 minutes. The custard should be a light yellow and coat the back of a spoon.

Remove promptly from the heat and stir in the butter a piece at a time, allowing each addition to melt before adding the next.

Remove promptly from the heat and stir in the butter a piece at a time, allowing each addition to melt before adding the next.

Remove to a clean container and cover by laying a piece of plastic wrap directly on the surface of the curd. This will keep a skin from forming on the top. (It’s the same trick that keeps guacamole from turning brown.)

Remove to a clean container and cover by laying a piece of plastic wrap directly on the surface of the curd. This will keep a skin from forming on the top. (It’s the same trick that keeps guacamole from turning brown.)

Refrigerate for at least 4 hours prior to serving. The curd will keep in the refrigerator for up to 2 weeks.

Refrigerate for at least 4 hours prior to serving. The curd will keep in the refrigerator for up to 2 weeks.

Yield: 1 pint

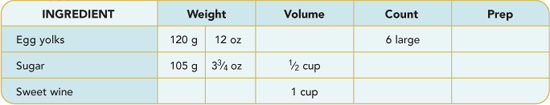

One of the most elegant desserts of all time when served in a goblet with seasonal fruit, zabaglione is so simple the guy from Sling Blade could make it (to top his biscuits, of course). It’s a custard, but instead of dairy or fat the liquid held in the egg yolk’s net is wine. The French call this sabayon and often flavor it with dry white wine and use it as a sauce for fish.

You’ll notice that, operationally speaking, there is only one real difference between this and a curd. The butter in a curd is only added after the custard has cooked because the fat in the butter could get in the way of coagulation. Since the wine holds no such threat, it can be whisked in during coagulation. This also helps to cook away some of the “hot” alcohol flavor and it adds to the speed at which this sauce can be tossed together.

Hardware:

3 small bowls for separating eggs

Digital scale

Dry measuring cups

Wet measuring cups

Large saucepan

Large stainless-steel bowl

Whisk

Sauternes, Muscat, Marsala, or Madeira all work well.

Apply the STIRRED CUSTARD METHOD (see here), whisking the egg yolks until smooth and slightly lightened in color.

Apply the STIRRED CUSTARD METHOD (see here), whisking the egg yolks until smooth and slightly lightened in color.

In a large saucepan, bring about an inch of water to a boil, then reduce to a simmer.

In a large saucepan, bring about an inch of water to a boil, then reduce to a simmer.

Meanwhile, in a large stainless-steel bowl, whisk the egg yolks until they are smooth and slightly lightened in color.

Meanwhile, in a large stainless-steel bowl, whisk the egg yolks until they are smooth and slightly lightened in color.

Gradually beat in the sugar, continuing to beat until thick and lemon colored.

Gradually beat in the sugar, continuing to beat until thick and lemon colored.

Set the bowl atop the saucepan over the barely simmering water, making sure the bottom of the bowl does not touch the water.

Set the bowl atop the saucepan over the barely simmering water, making sure the bottom of the bowl does not touch the water.

Whisk constantly while slowly adding the wine, then continue whisking over the heat until the mixture triples in size, about 10 to 15 minutes.

Whisk constantly while slowly adding the wine, then continue whisking over the heat until the mixture triples in size, about 10 to 15 minutes.

Remove the pan from the heat and continue whisking slowly for 1 minute to dissipate any extra heat.

Remove the pan from the heat and continue whisking slowly for 1 minute to dissipate any extra heat.

Scoop the zabaglione into dessert dishes and scatter fresh berries on top. Serve warm.

Scoop the zabaglione into dessert dishes and scatter fresh berries on top. Serve warm.

Yield: About 6 cups (much of it air), 8 servings

Now let’s say that you like the idea of a light, airy, wine-flavored dessert but you want something more like a mousse. No problem. Now that you’ve seen how easy it is to make zabaglione, all you need are a few additional ingredients.

Hardware:

Digital scale

Wet measuring cups

Measuring spoons

Stand mixer with whisk attachment

Small saucepan

Balloon whisk

Large stainless-steel bowl

Large saucepan

Paper plate

Prepare the zabaglione, following the recipe on the previous page.

Prepare the zabaglione, following the recipe on the previous page.

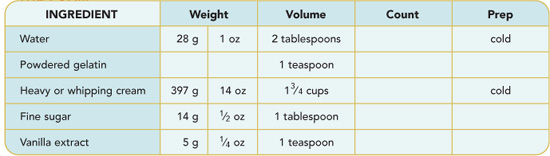

Pour the cold water into a small saucepan and sprinkle the gelatin over the water. Allow the gelatin to bloom (“Blooming” or soaking the gelatin before heating will soften the granules so they’ll dissolve more smoothly.) for 10 minutes, and then place the pan over low heat, bringing the mixture to 140°F and dissolving the gelatin.

Pour the cold water into a small saucepan and sprinkle the gelatin over the water. Allow the gelatin to bloom (“Blooming” or soaking the gelatin before heating will soften the granules so they’ll dissolve more smoothly.) for 10 minutes, and then place the pan over low heat, bringing the mixture to 140°F and dissolving the gelatin.

Meanwhile, in the work bowl of an electric stand mixer, combine the cream, sugar, and vanilla extract. With the whisk attachment, whip the cream to stiff peaks.

Meanwhile, in the work bowl of an electric stand mixer, combine the cream, sugar, and vanilla extract. With the whisk attachment, whip the cream to stiff peaks.

Temper (see here) the dissolved gelatin into the zabaglione and then fold (see here) in the whipped cream.

Temper (see here) the dissolved gelatin into the zabaglione and then fold (see here) in the whipped cream.

Chill for 6 hours before serving—I suggest vanilla wafers and a really fine wine as accompaniments. (This dessert will appear to set quickly, leaving you to wonder “why wait so long?” I’ll tell you why: gelatin can set up to 80 percent in just an hour or so—but the rest takes longer. So it may look like it’s set, but it’s only mostly set. The mixture will be a good deal tighter after 6 hours than after 2, but not radically so. Still, give the gelatin time to do its thing and your patience will be rewarded.)

Chill for 6 hours before serving—I suggest vanilla wafers and a really fine wine as accompaniments. (This dessert will appear to set quickly, leaving you to wonder “why wait so long?” I’ll tell you why: gelatin can set up to 80 percent in just an hour or so—but the rest takes longer. So it may look like it’s set, but it’s only mostly set. The mixture will be a good deal tighter after 6 hours than after 2, but not radically so. Still, give the gelatin time to do its thing and your patience will be rewarded.)

Yield: Eight servings

THIS IS ONE OF THOSE MYSTERIOUS PROCEDURES that seems crucial to the success of every application in which it rears its ill-defined head.

The verb “fold” refers to the folding of an airy mixture like whipped egg whites much in the way you might fold a napkin or handkerchief…okay, not exactly, but the aim is to fold the mixture over onto itself rather than stir it, whisk it, or beat it—any of which would only deflate the precious bubbles you’ve built.

Typically this “folding” is achieved by placing the two substances (a foam and a heavier, more viscous substance) together in a large bowl. The folder then plunges a rubber spatula down the middle of the mass to the bottom of the bowl and sweeps up the side, thus flipping half the mass over on itself. The job is made easier by first mixing about a quarter to a third of the foam directly into the base, quickly, to lighten it.

I do my folding in the biggest bowl I have, which is generally twice the size of whatever I’m folding. And instead of a rubber spatula, I use a paper plate. It’s more flexible, it’s bigger, it makes less of a mess and gets the job done faster than a spatula. But I don’t dig down into the middle, I swoop in from the side while rotating the bowl with the other hand.

Although I always recommend using the best chocolate you can get your hands on, I usually make this mousse with those little bitty bars of Hershey’s Special Dark that you’re always left with after Halloween. It takes 40 of the little guys. By the way, the stubby French painter Toulouse-Lautrec supposedly invented chocolate mousse—I find that rather hard to believe, but there you have it.

Hardware:

Digital scale

Wet measuring cups

Measuring spoons

Chef’s knife

Cutting board

2 large metal mixing bowls

Large saucepan

Wooden spoon

Rubber or silicone spatula

Small saucepan or metal measuring cup

Electric hand mixer

Small serving bowls or martini glasses

Plastic wrap

Not baking chocolate—if it doesn’t taste good by itself, don’t use it here.

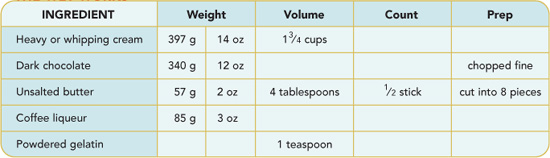

Pour 1 1/2 cups of the cream into a large metal mixing bowl and stash it in the freezer.

Pour 1 1/2 cups of the cream into a large metal mixing bowl and stash it in the freezer.

Place the chocolate, butter, and liqueur in another large metal bowl and melt over a pot of barely simmering water (filled about 1 inch high), stirring constantly.

Place the chocolate, butter, and liqueur in another large metal bowl and melt over a pot of barely simmering water (filled about 1 inch high), stirring constantly.

Remove from the heat while a couple of chunks are still visible. For the next 5 minutes continue to stir occasionally, until the mixture cools to just above body temperature. Set aside.

Remove from the heat while a couple of chunks are still visible. For the next 5 minutes continue to stir occasionally, until the mixture cools to just above body temperature. Set aside.

Place the remaining 1/4 cup of the cream in a small saucepan or large metal measuring cup and sprinkle the gelatin over it. Allow the gelatin to bloom for 10 minutes, then dissolve the gelatin by carefully heating and swirling the pan over low heat. Whatever you do, don’t let the cream boil or the gelatin’s setting power will be greatly reduced.

Place the remaining 1/4 cup of the cream in a small saucepan or large metal measuring cup and sprinkle the gelatin over it. Allow the gelatin to bloom for 10 minutes, then dissolve the gelatin by carefully heating and swirling the pan over low heat. Whatever you do, don’t let the cream boil or the gelatin’s setting power will be greatly reduced.

Stir the mixture into the cooled chocolate and set aside.

Stir the mixture into the cooled chocolate and set aside.

Remove the cream from the freezer and use an electric hand mixer to beat the cream to medium peaks.

Remove the cream from the freezer and use an electric hand mixer to beat the cream to medium peaks.

Before bringing the mousse and the whipped cream together in culinary matrimony, lighten up the chocolate mixture by stirring in just a little bit of the whipped cream—just so the two become a little more alike in texture. Then fold in half of the remaining whipped cream (see here). Don’t overdo it or you’ll beat all that air out of the whipped cream. Then add the remainder of the whipped cream and fold it in. The mixture should remain light and fluffy—if there are still a few flecks of white, it’s okay.

Before bringing the mousse and the whipped cream together in culinary matrimony, lighten up the chocolate mixture by stirring in just a little bit of the whipped cream—just so the two become a little more alike in texture. Then fold in half of the remaining whipped cream (see here). Don’t overdo it or you’ll beat all that air out of the whipped cream. Then add the remainder of the whipped cream and fold it in. The mixture should remain light and fluffy—if there are still a few flecks of white, it’s okay.

Cover the bowl with plastic wrap or spoon the mousse into individual dessert dishes (martini glasses work very nicely for this), cover the dishes, and refrigerate for at least 2 hours.

Cover the bowl with plastic wrap or spoon the mousse into individual dessert dishes (martini glasses work very nicely for this), cover the dishes, and refrigerate for at least 2 hours.

Garnish with fruit—or not—and serve.

Garnish with fruit—or not—and serve.

Yield: 8 servings

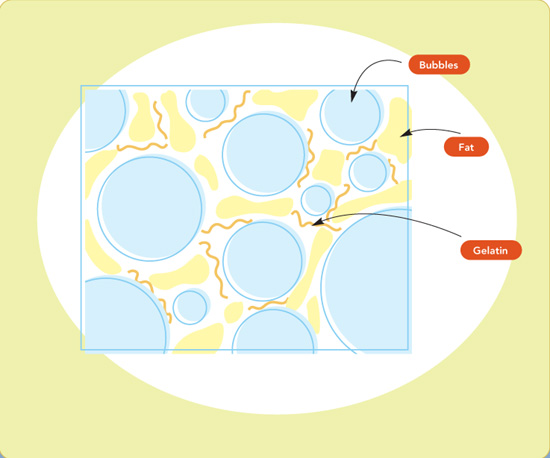

TINY BUBBLES, IN THE MOUSSE MAKES ME HAPPY… makes me feel loose. Okay, so I’m not Don Ho. But like Don I appreciate bubbles—they’re everywhere in this book.

But making the bubbles that make up whipped cream is a little different, because unlike egg whites, which inflate best when warm, whipping cream and everything it touches needs to be kept as cold as possible. Why? Because the bubble walls in whipped cream are supported not by protein but by sticky little globules of fat—and unless they’re cold, they won’t be sticky.

To whip cream you’ll need a big metal bowl and a decent mixer. Although we converted to a stand mixer for most applications in this book, this is the one place I’d rather stick with a hand mixer. It can create more turbulence in the bowl and for whipped cream, at least, that’s good. Start beating the cream on a relatively low speed, just to whip up some big proto-bubbles. As soon as you get a good Mr. Bubble Bath thing going, crank on the power.

Here’s what’s going on:

The walls of these proto-bubbles are made up mostly of water and the water soluble materials inside the cream. There are globs of fat drifting around inside the walls and, of course, there’s air inside. Now, the more air you whip into the cream, the more bubbles you make. But there’s only so much water to go around so eventually you really can’t make more bubbles, you can only subdivide the ones you’ve already made. Eventually these bubbles become so small that the fat globules touch and bingo, you have yourself a stable whipped cream.

What can go wrong, you ask? Well, if you were to continue whipping, the little fats would eventually squeeze out all the water and all the air and you’d find yourself in possession of homemade butter. Good for you. Now go make some toast.

Assuming that you don’t make butter, you’re still doomed because even if you keep it cold, eventually the water and fat, which aren’t very fond of each other even in this microscopic milieu, will separate unless the water is stabilized with a protein mesh like gelatin.

One little teaspoon of gelatin will stabilize all that water, just let it bloom for 10 minutes in cold water, then dissolve it over low heat. Just keep moving it around until you don’t see any more grain and be careful not to boil it because that would damage the gelatin.

Cheesecake is a unique and uniquely significant application. Significant because if you can consistently make good ones, fame shall be yours and strangers will bow low when you walk by. Unique in that cheesecake is one of the few devices that dwells in both the custard world and the realm of the cake. It is a custard because it depends on egg protein alone (not flour) for its structure, and yet its texture is derived from the creaming method. Cheesecake is also significant because it is so fine…oh yes, children, it is.

I have pursued cheesecake for a long time now and a couple of years ago felt certain that I had gotten it right. But now I think this one’s better—not perfect of course, but better. Shall we begin?

Place an oven rack in position B and preheat the oven to 300°F.

Place an oven rack in position B and preheat the oven to 300°F.

Prep a 9 by 3-inch round cake pan (see here).

Prep a 9 by 3-inch round cake pan (see here).

(Clever, huh?)

Unlike finicky pastry crusts, the pressed or crumb crusts upon which classic cheesecakes are constructed are as much fun to make as they are to eat—and they can be made with almost anything. For instance:

Stale cake crumbs

Stale cake crumbs

Crumbled gingersnaps

Crumbled gingersnaps

Crumbled Frosted Flakes

Crumbled Frosted Flakes

Crumbled Ritz crackers (for savory cheesecake only)

Crumbled Ritz crackers (for savory cheesecake only)

Crumbled vanilla wafers

Crumbled vanilla wafers

Crumbled graham crackers

Crumbled graham crackers

Crumbled Honey Grahams cereal

Crumbled Honey Grahams cereal

Beat-up Oreos (Ooh, aah.)

Beat-up Oreos (Ooh, aah.)

Hardware:

9 by 3-inch round aluminum cake pan

Parchment paper

Kitchen shears or scissors

Digital scale

Dry measuring cups

Wet measuring cups

Measuring spoons

Roasting pan

Kitchen towels

Kettle

Electric stand mixer with paddle attachment

Rubber or silicone spatula

Clean kitchen towel

Large mixing bowl

Whisk

Cooling rack

Paring knife

Cake round

Thin, sharp knife

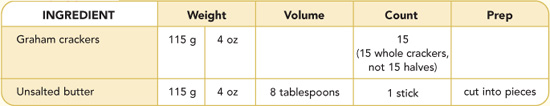

Break up the graham crackers, drop them in the work bowl of a food processor and pulse about 7 times, until there are just a few big pieces left, then add the butter and pulse until the butter disappears and the crumbs slowly fall over when the machine stops.

Break up the graham crackers, drop them in the work bowl of a food processor and pulse about 7 times, until there are just a few big pieces left, then add the butter and pulse until the butter disappears and the crumbs slowly fall over when the machine stops.

Use your fingers to pack the crumb mixture into the bottom of the pan, working outward from the middle. You’ll end up with a smooth bottom and a pile all around the outer edge. You can turn this pile into the sides of the crust by turning the pan with your thumbs on the outside of the pan and the rest of your fingers on the inside. Press, but don’t squeeze too hard or you’ll push through the crust.

Bake this blind for 10 minutes, then stick it in the fridge to cool.

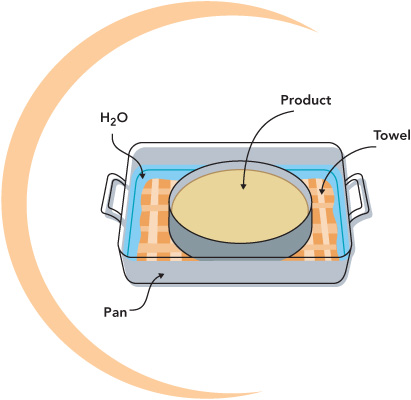

Turn the oven down to 250°F and bring a quart of water to boil in a kettle. If you have a really large roasting pan you may need more. You’ll want the water to come up to within an inch of the top of the pan. Place a kitchen towel in the bottom of the pan (to prevent slippage).

(That doesn’t work as well, does it?)

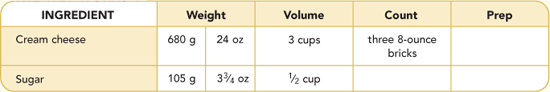

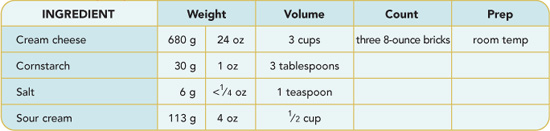

Place the cream cheese with the sugar in the bowl of an electric stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment. Beat on medium speed until completely smooth and creamy. You’ll have to stop and scrape down the bowl sides at least twice—actually, just twice. If tiny little bits of cream cheese reach exit velocity and attempt to leave the bowl, simply drape the mixer with a clean kitchen towel.

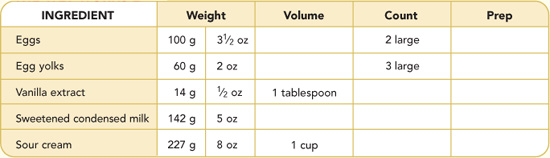

While the mixer’s teaching the cream cheese a thing or two, in a large bowl whisk the eggs and egg yolks together with the vanilla, sweetened condensed milk, and sour cream. (Weighing the sweetened condensed milk is required because it’s almost impossible to deal with any other way.)

Now, turn the mixer down to about 30-percent power and slowly—very slowly—drizzle the egg mixture into the cream cheese. (Why slowly? Because if you add the egg mixture quickly, it’ll sling out of the bowl and all over you.) Stop halfway through and scrape the bowl, sides and bottom. (Although I usually prefer Zyliss spatulas, I have to say that when it comes to scraping down the sides of a KitchenAid mixer, nothing does the trick like a KitchenAid spatula.)

As soon as the egg mixture is completely integrated, pour the batter onto the crust. Place the cheesecake in the roasting pan, then open the oven door and rest the roasting pan on it. Fill the roasting pan with the boiling water and place the whole thing in the oven. Close the door and set the timer for an hour. During this hour you will not:

Open the door.

Open the door.

Touch the door.

Touch the door.

Mess with the door in any way.

Mess with the door in any way.

If you want to see what’s going on, turn on the light and look through the window. If the window is too dirty to see through, make a note to clean the oven. Why? Because heat energy bounces off clean, shiny walls better than uneven, gunked-up walls. If your oven walls (and door) are nasty, then food can’t cook evenly or efficiently. (When I run my oven through its self-clean cycle I usually stick my grill grates in there, too—any built-on gunk will magically vanish, but if they’re iron you’ll need to re-cure them.)

When the timer goes off, turn the oven off, open the door, and take a look. Doesn’t look done, does it? In fact, it looks like soup. Well, that’s because the cooking’s only half over. Wait 1 minute, then close the door and set the timer for another hour.

Open the door.

Open the door.

Touch the door.

Touch the door.

Mess with the door in any way.

Mess with the door in any way.

What the heck’s goin’ on here? The slower we coast across the thermal finish line, the better the odds are that we won’t overcook the custard. At this point there’s enough residual heat in the oven walls, the water, and the custard itself to finish the job.

When the second hour is up, you may still think the cake’s too wobbly for your comfort. But before you curse my name, reactivate the oven, and close the door, remember the scrambled egg axiom: if eggs look done in the pan they’ll be overdone on the plate. If you continue to cook this custard until it really looks done, as soon as it cools it’s going to start cracking on top. Cracks are the number one sign of over-coagulation.

Cool to room temperature for 1 hour, then chill until the edges of the cake pull away from the side of the pan (3 to 6 hours). Run a knife around the inside edge of the pan just to be sure.

Insert a paring or boning knife straight down between the side of the cake and the parchment and spin the pan while holding the knife still. Fill that roasting pan that you probably left sitting in the oven—or the kitchen sink—with 1 inch of hot water. Set the pan in the water, wait about 5 seconds, then slowly pull the paper straight out.

Move the pan to a towel to catch the water. Place another parchment round on top of the cake, then place a cake round or the bottom of a standard springform pan (I said I didn’t like them, but that doesn’t mean I can’t try to find another use for them.) on top of the cake. Holding the round firmly against the top of the cake, flip the whole thing over. Then simply slide the pan off. Place another cake round or your serving plate upside down on the upturned bottom of the cake and re-invert.

If you’ve used a springform pan, de-panning is a pretty simple step. Just make sure the side ring is completely unstuck to the pie, slowly undo the buckle, and remove. As for the bottom disk, most folks leave the pie on it for serving. Now the last challenge is…

You’ve heard the expression “like a hot knife through cheesecake”? Okay, it’s usually butter, but it might as well be cheesecake, because there’s really no other way to cut one. I’ve heard of people who can cut a cheesecake with dental floss, but I’ve never been able to get through the crust. So I use a long, thin, sharp knife (a slicer would be good for this) and, if the going gets tough, dip it in hot water every now and then, wipe clean, and cut again.

No coulis, no sauce, no fruit—okay, maybe fresh fruit—but the way I see it, if the cake is good, why mess it up?

Wrapped first in plastic wrap then foil, cheesecakes freeze well for up to 3 months.

If you’re none too sure about your timing or your oven’s sincerity, you can take out a little crack insurance by adding a tablespoon of cornstarch to the batter when you add the sugar. The starch molecules will actually get in between the egg proteins, preventing them from over-coagulating. No over-coagulating, no cracks. Of course if you do end up with a cake that’s cracked on top, there’s always whipped cream.

What’s in a name? Okay, so here’s a darned tasty, savory cheesecake. Although it is absolutely a cheesecake, more than a few folks have suggested that the idea of trout cheesecake is way icky. Fine. Then I’ll call it a torte (I hope that the culinary brave among you will still call it by its true name… cheesecake.)…Smoked Trout Torte. Is that less icky? Good. This is a darned fine appetizer, or can be served alongside a salad as a light lunch or dinner. At room temp, it’s even a tasty breakfast. Think of it as a new twist on lox and bagels.

Hardware:

Digital scale

Dry measuring cups

Wet measuring cups

Measuring spoons

Small mixing bowl

9 x 3-inch aluminum round cake pan

Chef’s knife

Cutting board

Stand mixer with paddle attachment or electric hand mixer

Rubber or silicone spatula

Large mixing bowl

Whisk

Roasting pan

Kettle

Cooling rack

Place an oven rack in position C and preheat the oven to 350°F.

Place an oven rack in position C and preheat the oven to 350°F.

Prep a 9 x 3-inch aluminum cake pan (see here).

Prep a 9 x 3-inch aluminum cake pan (see here).

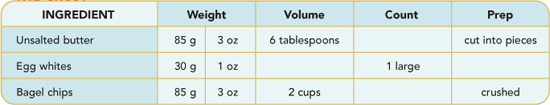

Break up the bagel chips, drop them in the work bowl of a food processor, and pulse about 7 times, until there are just a few big pieces left, then add the butter and egg white and pulse until the butter disappears and the crumbs slowly fall over when the machine stops.

Break up the bagel chips, drop them in the work bowl of a food processor, and pulse about 7 times, until there are just a few big pieces left, then add the butter and egg white and pulse until the butter disappears and the crumbs slowly fall over when the machine stops.

Pack the crumb mixture into the bottom of the pan with your fingers, working outward from the middle and then up the sides.

Pack the crumb mixture into the bottom of the pan with your fingers, working outward from the middle and then up the sides.

Blind bake for 8 minutes, until the crust starts to brown.

Blind bake for 8 minutes, until the crust starts to brown.

Remove from the oven and let cool. Reduce the oven temperature to 250°F while you make the filling.

Remove from the oven and let cool. Reduce the oven temperature to 250°F while you make the filling.

In an electric stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, blend the cream cheese, cornstarch, salt, and sour cream until smooth.

In an electric stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, blend the cream cheese, cornstarch, salt, and sour cream until smooth.

Add the eggs, one at a time.

Add the eggs, one at a time.

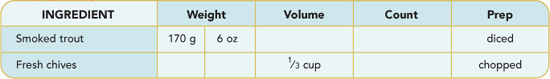

Fold in the trout and chives.

Fold in the trout and chives.

Prepare a roasting pan with a water bath as described here. Pour the batter over the cooled crust and bake for 1 hour. Turn the oven off and leave the cake in the oven for an additional hour without opening the door.

Prepare a roasting pan with a water bath as described here. Pour the batter over the cooled crust and bake for 1 hour. Turn the oven off and leave the cake in the oven for an additional hour without opening the door.

Cool on a rack for at least 4 hours. Carefully unmold as described here. Keep refrigerated until ready to serve.

Cool on a rack for at least 4 hours. Carefully unmold as described here. Keep refrigerated until ready to serve.

This will keep in the refrigerator for up to 5 days.

This will keep in the refrigerator for up to 5 days.

Yield: Serves 12 to 16, more as an appetizer