Chapter 3

1 John 2:1–6

Literary Context

This pericope continues the topic of sin that was introduced in 1:5–10, but moves the discussion from the more general level of “if we say …” to a more personal, direct address to “my little children” (τεκνία μου). This term occurs several times within the letter, most often in discussions involving the fatherhood of God. It may reflect Jesus’ use of the same term in the Upper Room Discourse (John 13:33).

The opening verse of this unit states the reason that the author writes “these things” (2:1), presumably referring back to the topic of sin and confession. John switches from “if we say” to “the one who says” (vv. 4, 6), which continues the discussion of consistency in the Christian life between a profession of faith in Christ and how one lives.

- I. John Claims the Authority of the Apostolic Witness (1:1–4)

- II. Announcement of the Message (1:5–10)

- III. Dealing with Sin (2:1–6)

- A. Bringing the Topic of Sin to Bear on His Readers (2:1–2)

- B. Knowing God Means Avoiding Sin by Keeping His Commands (2:3–6)

- IV. Love, Light, and Darkness (2:7–11)

Main Idea

This section addresses the relationship between two major concepts of authentic Christian living: the need to deal rightly with sin and the expression of love for God in Christ through obedience to his command. Both of these thoughts are integral to knowing God and, consequently, to having assurance of eternal life.

Translation

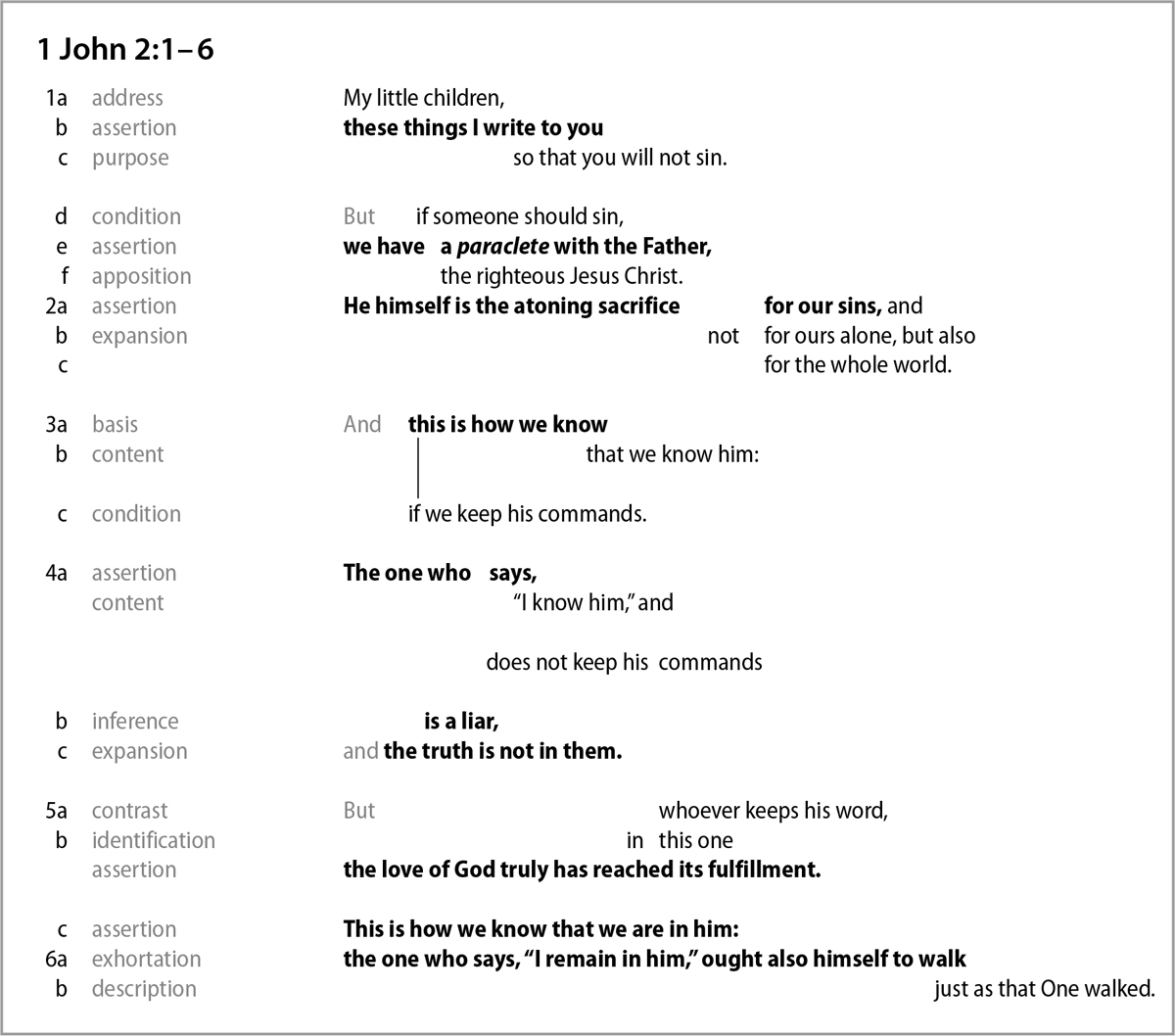

Structure

These verses are part of a larger discourse unit that extends from 2:1 through 2:17. Its span is marked by the vocative “my little children” (τεκνία μου) in v. 6 and the vocative “dear friends” (ἀγαπητοί) in v. 7 that begins a smaller discourse unit. Verse 1 (“these things I write to you so that you will not sin”) stands as the summary statement of the pericope.

The passage divides into two segments: vv. 1–2 and vv. 3–6 (which is further structured by the two statements in vv. 3 and 6, “this is how we know….” Each of these two statements is followed by the example of “the one who says….”

Exegetical Outline

- III. Dealing with Sin (2:1–6)

- A. Bringing the topic of sin to bear on his readers (2:1–2)

- 1. An admonition not to sin (2:1a-c)

- 2. Reassurance if one should sin (2:1d–2c)

- a. Jesus is the paraclete (2:1e-f)

- b. Jesus is the atoning sacrifice for sin (2:2)

- B. Knowing God means avoiding sin by keeping his commands (2:3–6)

- 1. Keeping God’s commands is the completion of God’s love (2:3–5)

- 2. Remaining in God means living as Jesus did (2:6)

- A. Bringing the topic of sin to bear on his readers (2:1–2)

Explanation of the Text

2:1 My little children, these things I write to you so that you will not sin. But if someone should sin, we have a paraclete with the Father, the righteous Jesus Christ (Τεκνία μου, ταῦτα γράφω ὑμῖν ἵνα μὴ ἁμάρτητε. καὶ ἐάν τις ἁμάρτῃ, παράκλητον ἔχομεν πρὸς τὸν πατέρα, Ἰησοῦν Χριστὸν δίκαιον). John states a second purpose for his letter: that his readers will not sin. This is entailed in having the joy of fellowship with God, the first stated purpose in 1:3–4.

After correcting anyone who might be denying or rationalizing their sin, John introduces an affectionate, conciliatory tone by addressing his readers as “my little children” (note the diminutive form of the plural, τεκνία). This vocative establishes his affection for his readers, while yet maintaining his authority to instruct them as someone older and wiser in the faith, and possibly someone who may have directly or indirectly been responsible for their conversion to Christ. Tradition holds that the apostle John left Palestine about the time of the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem in AD 70 and settled in Ephesus, from where he evangelized and planted churches in the surrounding region. Since the gospel had been so well received through the apostle Paul, who was executed in the mid-60s, John may have chosen Ephesus to continue an apostolic witness there.

Here, for the first time in the letter, the author refers to himself in the first person singular, “I write” (γράφω), which argues against the theory that this book may have begun solely as an oral form such as a homily or speech. Clearly the author foresaw as he wrote that his words would be sent in written form to their readers, even if the letter was read aloud to them. John’s intent with respect to the topic of sin is clear: he writes to warn his readers against sinning, in the many ways that sinning is possible, including a denial of sin. His explanation of sin as walking in a darkness that has no place in the Christian’s life both underscores the serious nature of sin and at the same time raises questions about the existential reality of sin, especially in the lives of believers. Much of what he subsequently will say on the topic addresses this tension. The subjunctive verbal form “will not sin” (μὴ ἁμάρτητε) is required in a hina clause expressing purpose, but that purpose is the admonition not to sin, which is better expressed in English with a future, imperatival form.

As Lieu observes, “the purpose of God’s forgiveness is to prompt those who experience it not to repeat the wrongs of the past.”1 But John’s wisdom also leads him to acknowledge immediately the reality that “someone” will likely sin. The subjunctive in the general, third class condition, “if someone should sin” (ἐάν τις ἁμάρτῃ), allows for that reality without countermanding his prior statement that they should not sin. In that case of someone sinning, his overarching purpose to reassure his readers that they have eternal life (5:13) comes into play. He asserts that “we have” a paraclete with the Father, the righteous Jesus Christ (see 1:9).

The frequent use of the first person plural pronoun (“we”) is distinctive of the Johannine writings. Its many occurrences in 1 John do not all have the same referent. In 1:1–4, regardless of whether it represents a genuine plural or stands as the author’s singular self-reference, its sense is dissociative. There the author was distinguishing himself from his readers on the basis of his role as an authoritative witness to the incarnation and its significance. Here in 2:1 it is an associative or inclusive “we,” for the author would certainly include himself among those for whom Jesus Christ is their paraclete.

The word paraclete (παράκλητος) is unique to the Johannine writings, but it does occur in Aquila’s and Theodotion’s versions in Job 16:2, replacing the cognate, παρακλήτωρ, found in Old Greek Job 16:2. There it refers to Job’s supporters, as wrongheaded as they may have been. Outside the Bible, it occurs several times in Philo to refer to an eminent person “giving support to someone making a claim, or settling a dispute, or rebutting a charge,”2 often in the context of the royal court. Philo’s use of the word in the context of sacrifice for sin following restitution of an injured party is particularly of interest, for after propitiating the injured party, the guilty party is to go to the temple to ask for God’s forgiveness, taking an irreproachable παράκλητος with him, which in this case is his own repentence (Spec. 1.237).3

Stoic influence in Philo casts the divine Logos as the paraclete who accompanies the high priest when he goes before God in the Holy of Holies on the Day of Atonement (Mos. 2.133–34).4 In Jewish thought of that time, one’s own good works were often thought to function as the paraclete before God’s judgment.5 Although sometimes interpreted as a legal advocate in court, it appears that it was a more general word with a broader meaning that has survived in several texts with a legal context. As Culy points out, the focus “is not so much on the ability of the [paraclete] παράκλητος to defend someone, but rather on the status of the παράκλητος, which allows him to bring about a good outcome for the one being accused” (italics original).6

The use of the word here echoes its occurrence in John 14:16, where Jesus says, “And I will ask the Father, and he will give you another advocate [παράκλητος] to help you and be with you forever” (italics added). Jesus refers to himself as the paraclete, or “advocate,” of his disciples, and he promises the Holy Spirit will also function in that role. The “righteous Jesus Christ” (Ἰησοῦν Χριστὸν δίκαιον) is in apposition with paraclete. Although the Spirit is also a paraclete, it is the unique status of Jesus as the atoning sacrifice for sin (see 2:2) that is the basis of his advocacy for sinners, which therefore provides consolation for anyone who sins.

2:2 He himself is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not for ours alone, but also for the whole world (καὶ αὐτὸς ἱλασμός ἐστιν περὶ τῶν ἁμαρτιῶν ἡμῶν, οὐ περὶ τῶν ἡμετέρων δὲ μόνον ἀλλὰ καὶ περὶ ὅλου τοῦ κόσμου). John makes a universal claim for the efficacy of Jesus’ atonement both here and in 4:14, where Jesus is described as “Savior of the world” (σωτῆρα τοῦ κόσμου). If and when someone sins, our advocate is someone who has standing with the Father, the righteous Jesus Christ, because he himself (αὐτός) is the atoning sacrifice for our sins.

Brown points out that Jesus is the hilasmos (ἱλασμός, atonement), not the hilastēr (ἱλαστήρ), the one who offers the atonement.7 How to construe and then translate the Greek word hilasmos here and in its only other occurrence in the NT at 4:10 is one of the perennial issues raised by this verse.8 The word occurs six times in the LXX (Lev 25:9; Num 5:8; Ps 129:4; Ezek 44:27; Am 8:14; 2 Macc 3:33) to refer to the removal of guilt achieved by the ritual practices of Israel’s ancient priesthood. The cognate noun hilastērion (ἱλαστηρίον) occurs frequently in the LXX Pentateuch to refer to the top covering of the ark of the covenant in ancient Israel’s Most Holy Place, where blood was sprinkled on the Day of Atonement.

Older English versions translated hilasmos in 1 John either as “propitiation” (e.g., KJV) or “expiation” (e.g., RSV), neither of which is easily defined and understood by the average person today. Propitiation is something done to win the favor of a, usually angry, god, spirit, or person,9 whereas expiation is directed toward nullifying an offensive act that has set in motion a train of undesirable events that has caused a breakdown in a relationship. However, the terms are not always used with clear distinction by modern authors, and more importantly, the Greek word does not clearly indicate the degree of nuance that is sought by modern theologians.

Throughout the history of the church, theologians have struggled to articulate a theory of atonement that adequately includes all the New Testament material.10 In distinction from the Christus Victor view that atonement is achieved by Christ’s victory over evil (cf. 1 Pet 3:22), or from the view that Christ’s death appeases God’s anger (cf. Rom 1:18), John’s writings present Christ as a replacement for animal sacrifice in the temple. Early in his story of Jesus, John reports John the Baptist’s exclamation, “Look, the Lamb of God!” (John 1:36), surely an allusion to the sacrificial lambs of temple sacrifice. The parallel structure of 1 John 2:1 with 1:7, 9 confirms that “Jesus Christ … the hilasmos for our sins” is parallel with “the blood of Jesus his Son cleanses us from all sin” (1:7) and “to cleanse us from all unrighteousness” (1:9).11

However, atonement for sin in John’s thought is not a reference to God’s anger, but to his love. “In this way is love [defined]: not that we have loved God, but that he loved us and sent his Son to be an atoning sacrifice for our sins” (4:10).12 In Johannine thought, the cross is the exaltation of Jesus and the clearest expression of God’s love. (See Theology of John’s Letters.)

In 1 John 2:1–2, Jesus is called both our paraclete and our hilasmos. The meaning of this distinctive combination is to be found in Jewish thought, not Hellenistic.13 If a Christian sins, his or her otherwise good works cannot function as the paraclete before the Father (πρὸς τὸν πατέρα). Only Jesus Christ, who died to atone for sin and who lives to intercede and mediate our petition for forgiveness, can fill that role.

John’s further statement that Jesus is the atoning sacrifice, not only for “our” sins, but also for those of the whole “world” (κόσμος), is sometimes used to support the idea of universalism—that is, that everyone in the world will be saved by Christ’s atoning sacrifice, apparently whether they know it or not. But such a thought ignores both the historical context of the book and the particular use of kosmos in the Johannine corpus (cf. John 3:16, which presupposes the death of Jesus and consequent forgiveness of sins). One response to claims of universalism is to argue that Christ’s death is sufficient to atone for the sins of the whole world, even if only those who actually come to faith in him are saved from their sin. While that may be true, as John Calvin acknowledges, it is not what John is saying here.14 If here it is a reference to the whole planet, consideration of the historical context in which John wrote makes a more likely interpretation to be the universal scope of Christ’s sacrifice in the sense that no one’s race, nationality, or any other trait will keep that person from receiving the full benefit of Christ’s sacrifice if and when they come to faith.

In the ancient world, the gods were parochial and had geographically limited jurisdictions. In the mountains, one sought the favor of the mountain gods; on the sea, of the sea gods. Ancient warfare was waged in the belief that the gods of the opposing nations were fighting as well, and the outcome would be determined by whose god was strongest. Against that kind of pagan mentality, John asserts that the efficacy of Jesus Christ’s sacrifice is valid everywhere, for people everywhere, that is, “the whole world.” The Christian gospel knows no geographic, racial, ethnic, national, or cultural boundaries.

But “world” in John’s writings is often used to refer not to the planet or all its inhabitants, but to the system of fallen human culture, with its values, morals, and ethics as a whole. Lieu explains it as that which is totally opposed to God and all that belongs to him.15 It is almost always associated with the side of darkness in the Johannine duality, and people are characterized in John’s writings as being either “of God” or “of the world” (John 8:23; 15:19; 17:6, 14, 16; 18:36; 1 John 2:16; 4:5). Those who have been born of God are taken out of that spiritual sphere, though not out of the geographical place or physical population that is concurrent with it (John 13:1; 17:15; see “In Depth: The ‘World’ in John’s Letters” at 2:16).

Rather than teaching universalism, John here instead announces the exclusivity of the Christian gospel. Since Christ’s atonement is efficacious for the “whole world,” there is no other form of atonement available to other peoples, cultures, and religions apart from Jesus Christ. As Calvin comments:

Therefore, under the word “all” he does not include the reprobate, but refers to all who would believe and those who were scattered through various regions of the earth. For, as is meet, the grace of Christ is really made clear when it is declared to be the only salvation of the world.16

2:3 And this is how we know that we know him: if we keep his commands (Καὶ ἐν τούτῳ γινώσκομεν ὅτι ἐγνώκαμεν αὐτόν, ἐὰν τὰς ἐντολὰς αὐτοῦ τηρῶμεν). John turns to a major theme of knowing God. To know God means to be in covenant with him, as God revealed through the prophet Jeremiah: “ ‘they will all know me’ … declares the LORD” (Jer 31:34). As Dodd pointed out, this is a summary statement of the new covenant promised by God, when he forgives sin and forms a people by writing the law on their hearts.17

To know God is to be in covenant with him, and consequently to have eternal life, as Jesus defines it in the Upper Room Discourse of John’s gospel: “Now this is eternal life: that they know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom you have sent” (John 17:3). If that is the case, then John’s desire to assure his readers that they have eternal life means assuring them that they do, in fact, know God truly (1 John 5:13). Therefore, knowing God, and how we know that we know God, is central to the purpose of the letter, a theme occurring eight other times in 1 John (2:4, 13; 3:1, 6; 4:6, 7, 8; 5:20).

One of the problems with religion in the Greco-Roman world was that it was impossible to know what the pagan gods and goddesses wanted from people to avert their disfavor. Pagan religion centered largely on placating the gods with the goal of avoiding any unpleasant circumstances that it was believed the gods would send in their displeasure. There was no true quest for a relationship or personal knowledge of the deities, just an appeasement of the gods to avoid their disfavor.

It was natural to extend this motive of avoiding misfortune into the sphere of life after death for those who embraced the concept. The second-century movements of various forms of Gnosticism, a modern term derived from the Greek word for knowledge (γνῶσις), offered ways of achieving deliverance of the soul after death through spiritual knowledge about oneself and one’s destiny that could be gained only by mystical experience in this life. Gnosticism was not a religion, but a worldview that cut across many religions of its time.18 Although gnostic thinking flourished much later—in the second and into the third centuries—its foundational principles, at least in embryonic form, were influential much earlier, even in the late first century.

In one of the later Christian expressions of a gnostic movement reflected in the (so-called) Gospel of Thomas, it was interpretations (or fabrications) of Jesus’ teaching that were seen to be the central advantage of Christianity. Jesus was valued not for atonement but as a source of gnōsis (“knowledge”). The Gospel of Truth, a second-century gnostic writing, also centers on the redemption of people not out of sin and its consequences, but from ignorance and error by giving them knowledge that will benefit them in the afterlife.19 But when the NT speaks of knowing God, a different kind of knowledge is in view. Yes, it is redemption from the ignorance and error of a fallen world, but it is knowledge of God that brings people into a personal and proper relationship with him as Creator, Redeemer, and Judge of the universe.

In sharp contrast to the value of Jesus as a source of gnōsis that will provide the passcodes to the afterlife, John has clearly stated the central atoning role of Jesus’ death in the preceding two verses. The central truth of the Christian gospel is that God has revealed himself in the sacrificial death of his Son, which atones for the evil, immoral behavior of people—our sin. And in this way, the Son has made God the Father known as a personal being (John 1:18). While Jesus’ teachings are important, they are so because of his unique identity as the Son of God, who has conquered sin and death by rising from the grave, and not because he is simply a good teacher of gnōsis. Furthermore, gnōsis was a formal philosophical construct that did not strive for relationship with the creator God, whereas Jesus taught within the structure of a historical convenantal framework that had relationship with God at its heart.

Because the fundamental problem is sin, John relates the assurance of eternal life (1 John 5:13)—that we can know we have come to know God—to one’s response to God’s revealed will (see The Theology of John’s Letters). The Father of Jesus Christ is not capricious, nor has he failed to communicate his will, as was thought in the ancient pagan world of the pantheon. He has revealed himself to mankind in various ways and at various times throughout human history (cf. Heb 1:1–2), but has spoken the last word in his Son. In the Bible he documented his redemptive work in human history and its significance so that all who read it may know him. The goal of God’s redemptive work is to restore to himself a covenant people who will live every day of their lives in the knowledge of God’s revealed will. This is a different kind of spiritual gnōsis than is found in the various forms of Gnosticism, even in its Christianized forms.

In keeping with the objective of reassurance, John writes that we know (present tense, γινώσκομεν, a reference to having confidence in the present) that we have come to know God (perfect tense, ἐγνώκαμεν, a reference to a past experience of God that brought us to a knowledge of him that continues in the present)—in this way (ἐν τούτῳ), a forward-pointing (cataphoric) reference to what he says next.20 We may find reassurance that we know God truly “if we keep his commands” (ἐὰν τὰς ἐντολὰς αὐτοῦ τηρῶμεν). Conversely, if we do not keep his commands, then we have good reason to question whether we truly know him and have eternal life.

The idea of obedience to God is central to knowledge of him, for to know him truly is to know that he is the sovereign Lord of the universe, to whom all owe obedience. To be clear, John is not teaching that obedience is necessary as a condition of knowing God; rather, it is a result of true knowledge of God and of ourselves as sinners (cf. 2 John 4–6). As Lieu puts it, “obedience to the commands … is the sure evidence of a knowledge of God or of Jesus that cannot otherwise be proven” to ourselves or to others.21 In fact, as 1 John 2:4 claims, the one who claims to know God but does not keep his commands is a liar in whom there is no truth.

Before thinking about what commands John might have in mind, we should note the important point John is making, that knowing God and having fellowship with God must be expressed in how we live. There was little ethical content relevant to living in this life in the pagan religions of John’s day. But a gnostic worldview did have an influence on how people lived, often a negative influence. Because of its focus on the afterlife, Gnostics believed that the material world, including our bodies, was irrelevant to their redemption at best. That view could lead to a licentious lifestyle in which the carnal and worldly urges were indulged. The alternative view in Gnosticism that the material world was evil often led to a harsh ascetism in which the body was punished by self-abuse. In sharp contrast to this kind of belief, John teaches that the kind of knowledge of God revealed in Christ must be expressed in a life lived in the here and now in obedience to “his” commands.

John’s statement immediately brings at least two important questions to mind: (1) What commands? and (2) Does this reduce the Christian gospel to a form of legalism? One aspect of addressing the first question involves determining the referent of the pronoun “his” (αὐτοῦ). Are they God’s commands, as for instance in the OT, or Jesus’ commands as taught, for instance, in the Sermon on the Mount? The nearest antecedent in this unit of discourse is “the righteous Jesus Christ” (v. 1), and Jesus makes an appropriate referent for all similar pronouns in this unit, particularly in the admonition in v. 6 to walk as “that One” walked. Furthermore, v. 5 distinguishes between keeping “his word” (αὐτοῦ τὸν λόγον) and “the love of God” (ἡ ἀγάπη τοῦ θεοῦ). Based on this, it is likely that John had Jesus in mind throughout.

Nevertheless, when John subsequently picks up the concept of commands in 3:23–24, it is clearly God’s commands in view: “And this is his command: to believe in the name of his Son, Jesus Christ, and to love one another, just as he gave the command to us. And the one who keeps his commands remains in him [God], and he himself in them.” Furthermore, the statement in 2:5 that “this is how we know that we are in him” in the context of keeping the commands is parallel to the thought in 3:24, that the one who keeps God’s commands lives in him. Consistent with Johannine thought, God’s commands and Christ’s commands are one (cf. John 5:19; 10:30).

So do “his commands” refer to the Ten Commandments? Is keeping the Ten Commandments a Christian expression of knowing God? And if so, would that be any different qualitatively from the ancient Israelite’s knowledge of God? Surely Jesus kept the Ten Commandments perfectly, and John says the one who claims to know God should walk as Jesus walked (2:6). But as Yarbrough points out, part of the issue may be the English translation of the word translated “command” (ἐντολή) as “commandment.”22 The Ten Commandments are not referred to in the LXX with this word, even though it is used many times elsewhere. Furthermore, there is no reference to keeping the Mosaic law in John’s writings as there is, by way of comparison, in Paul’s writings. As Lieu puts it, the commands here are “not a particular set of instructions about behavior” but “an acceptance that to be brought into and to remain in a relationship with God is to recognize and to respond to whatever God requires, simply because it is what God requires.”23 One who truly knows God recognizes his glory and excellence and obeys God’s commands because they are excellent and beautiful.

Moreover, there is the clear definition of God’s commands within the context of 1 John itself, corroborated by John’s gospel, and that should inform our interpretation here. “And this is his command: to believe in the name of his Son, Jesus Christ, and to love one another, just as he gave the command to us” (3:23). God commands us to believe in the name of his Son (see comments on 3:23) and to love one another, just as Jesus commanded his disciples in John 13:34–35. The two components of this command are specifically the two major themes of John’s letters. What does it mean to believe in the name of Jesus Christ? What does it mean to love one another? The answer to both questions is tightly connected to living in a way that honors God’s revealed will.

2:4 The one who says, “I know him,” and does not keep his commands is a liar, and the truth is not in them (ὁ λέγων ὅτι ἔγνωκα αὐτόν καὶ τὰς ἐντολὰς αὐτοῦ μὴ τηρῶν, ψεύστης ἐστίν, καὶ ἐν τούτῳ ἡ ἀλήθεια οὐκ ἔστιν). Again John states the importance of Christian profession and moral integrity. The assertion of v. 3, that we know we have come to know God if we are living out the truth God has revealed in Christ, leads John here to state its inverse. If anyone claims to have true knowledge of God but does not order their life according to God’s revealed truth (“does not keep his commands”), that person is living a lie. They cannot know God while continuing to ignore his moral will.

The perfect form of the verb “I have come to know him” (ἔγνωκα) implies a continuing relationship with God based on past experience, so this remark is directed toward those who claim to be Christian but who have not learned to respond in obedience to whatever God requires.24 Obedience to God, from whom all of life flows, is the definition of knowing him (John 17:3).

This is the third time “the truth” (ἡ ἀλήθεια) has been mentioned. In 1:6 the one who walks in darkness does not do the truth; in 1:8 the truth is not in those who claim to have no sin; here in 2:4 a similar statement is individualized to the one who claims to know God in Christ but is indifferent to his revealed will. Such a person does not have the truth. As Lieu observes, the words “truth” (ἀλήθεια) and “word” (λόγος) are paralleled: “the truth is not in us” (1:8) and “his word is not in us” (1:10). Here in 2:4 “truth” is put in parallel with “commands” (ἐντολάς). “The effect is not to reduce the scope of ‘word’ to only the command to love one another (3:11), but to elevate the idea of the command so that it is intrinsic to the message about Jesus, and about God’s activity in Jesus (see 1:2).”25

In vv. 5 and 7, “command” will be identified with “word,” which strongly suggests that “truth,” “word,” and “command(s),” although not exactly interchangeable in John’s thoughts, are closely related. Anyone who wishes to walk authentically in the light of God cannot pick and choose which of the three is preferable. All three must be present in the believer’s life. Therefore, truth in John’s thought is not simply a collection of facts, but “represents the integrity and authenticity” of the entire message of redemption that God has revealed.26 (See “In Depth: ‘Truth’ in John’s Letters” at 1:6.)

2:5a-b But whoever keeps his word, in this one the love of God truly has reached its fulfillment (ὃς δ’ ἂν τηρῇ αὐτοῦ τὸν λόγον, ἀληθῶς ἐν τούτῳ ἡ ἀγάπη τοῦ θεοῦ τετελείωται). This is the first mention of “love” (ἀγάπη), a major theme in the epistle (see “In Depth: ‘Love’ in John’s Letters” at 4:16). Here the sense of the genitive τοῦ θεοῦ must be resolved. Is it subjective (God’s love for the one who keeps his word)?27 Or objective (human love for God)?28 As Kruse points out, both options are clearly represented elsewhere in the letter: God’s love for believers in 4:9, and the believer’s love for God in 5:3.29 In 4:12, where the sense is clearly subjective, the verb τελειόω in the perfect tense also occurs, which suggests that this is also the sense here. The statement should not be construed to mean that God’s love is not complete or perfect but must be made so by human involvement. In Johannine thought, God’s love, which is indeed perfect, must be lived out in the believer’s life; therefore, the goal of God’s love for believers is reached in the transformation of how believers treat others.

John points out that God’s love for us has a goal of moral transformation. This statement stands in contrast with v. 4, where someone was saying that they knew God in Christ but were not keeping his commands. The adverb ἀληθῶς implies that any claim for God’s love in those who are not keeping his word is false. Verse 5 advances the argument in positive terms by turning our focus to the one who does keep his word. Truth is not simply a collection of facts about God or Jesus, but demands a response in lifestyle that is mindful of who God is. Commands are not simply a list of rules and regulations that reduce Christian religion to a legalistic system, but refer to believing in Jesus Christ, the Son of God, and loving one another as he taught (3:23). The “word” (λόγος) is the full message of redemption that God has revealed in Christ, not simply the words on a page.

The ambiguity of the antecedent of “his word” (αὐτοῦ τὸν λόγον), whether God or Christ, continues here. Although we have argued above that Christ is the likely referent, John’s Christology, which understands the Son and the Father to be one (John 10:30), would allow God as the referent as well. But resolving the ambiguity brings an exegetical crispness: “Whoever keeps Christ’s word, that is, his command that we are to love one another, truly in this one the love of God (θεοῦ) has reached its fulfillment.”

Of the 116 times the noun “love” (ἀγάπη) occurs in the NT, a full quarter are found in John’s writings, and more than half of those in John’s writings are found in 1 John. The theme of love among believers in Christ is a major thought in John’s writings, and particularly in his letters (see The Theology of John’s Letters).

This discussion of “love” in John’s writings helps us to further the discussion of how to construe the genitive construction “love of God” (ἡ ἀγάπη τοῦ θεοῦ) here. As noted above, scholars have argued for both options. But if, as we have already suggested, “Jesus Christ” is the antecedent of “keeps his word,” then Jesus had much to say in the gospel about the believer’s love for him (italics added below):

- John 14:15: “If you love me, keep my commands.”

- John 14:21: “Whoever has my commands and keeps them is the one who loves me. The one who loves me will be loved by my Father, and I too will love them and show myself to them.”

- John 14:23: Jesus replied, “Anyone who loves me will obey my teaching. My Father will love them.”

These verses may suggest that in 1 John 2:5 we have an objective genitive, that the believer’s love for God reaches its fulfillment when that person loves Christ by living out his commands.

But Jesus also says in John 14:23 that the Father will love the one who loves Christ and obeys Jesus’ teaching, which suggests a subjective genitive in 1 John 2:5, God’s love for the believer. There is a decided ambiguity and reciprocity in the phrase “love of God.”30 Moreover, the concept of love for Christ is extended to love for others by the fundamental command of Jesus in John’s gospel (italics added):

- John 13:34: “A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another.”

- John 15:12: “My command is this: Love each other as I have loved you.”

- John 15:17: “This is my command: Love each other.”

Living out Jesus’ command to love is John’s major focus when he refers to commands in this letter (italics added):

- 1 John 3:11: For this is the instruction that you heard from the beginning, that we love one another.

- 1 John 3:23: And this is his command: to believe in the name of his Son, Jesus Christ, and to love one another, just as he gave the command to us.

- 1 John 4:7: Dear friends, let us love one another, because love is of God, and everyone who loves has been begotten of God and … knows God.

- 1 John 4:11: Dear friends, if God loved us like this, we also ought to love one another.

- 1 John 4:12: No one has ever seen God. If we love one another, God lives in us, and his love is completed in us.

- 2 John 5: And now I ask you, lady—not as writing you a new command but [as writing a command] that we have had from the beginning—that we love one another.

Taking “love of God” as an objective genitive in 1 John 2:5 produces a wonderful logical flow to John’s thought that helps to understand what the verb “reached its fulfillment” (τετελείωται) means, a word that is often translated with an English phrase including “perfected” (NASB, NKJV, ESV) and “perfection” (NRSV, NJB). And the shift in 2:7–11 to explicitly address love for others seems to confirm that here an objective genitive is in view (see comments on 2:7). But that translation doesn’t capture the sense of teteleiōtai in middle voice, which is more about reaching an intended goal than about meeting an impossibly high standard.31 In other words, God in Christ has loved us by redeeming us from sin (John 3:16; 1 John 4:10), and that love has a transformative goal in the life of the believer, that they should love God, both the Father and the Son, which is expressed by love for others (John 13:34).

That transformative goal has been reached in the one who lives out the message that God has revealed, for by doing so, the believer turns from sin and begins to relate rightly to God and to others. This does not mean that the believer has been perfected and no longer needs to continue to exercise love. Rather, when a believer loves others, the goal of God’s redemptive love in that person’s life has been achieved in that behavior.

Love as Jesus defined it is not an emotional response, though emotion may be involved; rather, love is the considerate treatment of others in accord with God’s revealed will (cf. the parable of the good Samaritan in Luke 10:25–37). Brown states this idea well: “Agape is not a love originating in the human heart and reaching out to possess noble goods needed for perfection; it is a spontaneous, unmerited, creative love flowing from God to the Christian, and from the Christian to a fellow Christian.”32 This flow of love from God to the Christian believer to others comports well with what John says in 1 John 4:10–11: “In this way love is [defined]: not that we have loved God, but that he loved us and sent his Son [to be] an atoning sacrifice for our sins. Dear friends, if God loved us like this, we also ought to love one another.” The circularity continues in 2 John 6a-b, “And this is love: that we walk according to his commands.”

2:5c–6 This is how we know that we are in him: the one who says, “I remain in him,” ought also himself to walk just as that One walked (ἐν τούτῳ γινώσκομεν ὅτι ἐν αὐτῷ ἐσμεν· ὁ λέγων ἐν αὐτῷ μένειν ὀφείλει καθὼς ἐκεῖνος περιεπάτησεν καὶ αὐτὸς [οὕτως] περιπατεῖν). John here introduces the idea that Jesus, in his life on this earth, is the role model for the Christian believer. In 1:7 the significance of Jesus’ death for cleansing sin was stated; here the significance of Jesus’ life on this earth is presented as an example for the believer who wants “to remain” (μένειν) in him.

There is considerable debate over whether “in this way” (ἐν τούτῳ) points backward (anaphoric) or forward (cataphoric). Is it that we that we can enjoy the assurance of eternal life that comes from knowing “we are in him” because we keep the command to love others (a backward reference)? Or does “in this way” point forward to v. 6, that it is only the one who walks as Jesus walked who can authentically claim to remain in him? In a change of punctuation from NA27, the editors of the NA28 Greek New Testament have punctuated the verse to leave the question unresolved. Nevertheless, a number of interpreters argue that the way one knows that they are “in him” is stated in v. 6. The disagreement suggests that this expression links what has just been said about loving God by loving others with the statement that follows about remaining in him.

Kruse notes that the phrase forms an inclusio with v. 3, but also notes that the topic of being in him anticipates v. 6.33 Culy offers the helpful data that clear cataphoric (forward-pointing) uses of the demonstrative pronoun in 1 John are usually followed by syntax that is not present here (an epexegetical hoti or hina clause), and he agrees with the editors of NA27 that the reference is anaphoric (that is, referring to a previous thought).34 While the reference primarily points backward, it also forms a transition to the thought that follows.35 This is reflected in the change in punctuation in NA28.

Believers in whom the love of God has attained its goal by producing love for others may know that they “are in him” (ἐν αὐτῷ ἐσμεν). John’s concept of being and remaining “in him” (ἐν αὐτῷ) is comparable to the apostle Paul’s foundational concept of being in Christ (e.g., Rom 8:1; 1 Cor 1:30; 15:18, 22; 2 Cor 1:21; 5:17; 12:19; Gal 3:26; 5:6; Eph 1:13; Phil 1:1; 4:21; 1 Thess 4:16). As Smalley notes, “When the writer speaks here of ‘existing in him’ we may conclude that a reference to Jesus is not entirely excluded. John is in fact asking how we can be sure that we are ‘in’ God, as he has made himself known in Christ Jesus.”36

The syntax of the Greek is the infinitive of indirect discourse.37 For an analogous English example, someone might say, “I know her,” which when repeated to a third party would be expressed as, “She claimed to know her” (using the English infinitive). The similar syntax in the Greek of v. 6 means that someone might claim, “I am abiding in God/Christ.” The subject of the verb “ought” (ὀφείλει) is the entire expression “the one who says, ‘I remain in him.’ ” What John is saying is to walk the talk. If one claims to abide in God, then one must also walk as “that One” (ἐκεῖνος) walked, an allusion to Jesus (e.g., John 1:18; 2:21; 5:11, 19). (One of the distinctive characteristics of John’s writings is his frequent use of the demonstrative pronoun instead of the personal pronoun and how often he uses it, though not exclusively, to refer to God or Jesus.)

“Remain” (μένω) is a favorite Johannine verb. More than 55 percent of all occurrences of this verb in the NT are found in John’s gospel and letters. Of the sixty-seven occurrences in John’s gospel and letters, twenty-one of these are found in the letters in reference to the believer remaining, or abiding, in God or Christ (e.g., 1 John 2:6, 10, 14, 17, 19, 24, 27, 28; 3:6, 9, 24; 4:15; 2 John 9). The concept of remaining or abiding is an important theological theme in Johannine thought. In John’s gospel, the mutual abiding of the believer in Christ and Christ in the believer is pictured beautifully in Jesus’ analogy of the vine and the branches in John 15. In the letters it refers to the presence of the Spirit in the believer (1 John 3:24; 4:13), and consequently the believer’s continuing belief in the gospel of Christ (1 John 4:15; 2 John 9) and their behavior toward others that expresses love for God (1 John 3:6; 4:12). The possibility of not remaining in him is also mentioned (1 John 3:6, 9; 2 John 9). In fact, John’s pastoral concern that his readers remain in God as revealed in Christ is arguably the major motivation of these letters.

The background for this idea is probably to be found in the promises of a new covenant relationship (Jer 31:33; Ezek 36:26, 27) that involves a new knowledge of God and the indwelling of his Spirit that transforms the believer (cf. John 14:16–17). The new covenant signals a relationship to God that is characterized not by cultic observances or the legalistic performance of requirements, but by a heart that has been changed to agree truly and sincerely with God and to follow after him.

The concept of a mutual indwelling of God and the Christian believer is distinctively different from God’s presence with his people in the OT, which was mediated through the tabernacle or temple (Exod 17:7; Deut 31:16–17; 2 Chr 6:18). The Spirit of God came upon people to equip them for specific redemptive acts, but it did not indwell them (Num 11:25; 24:2; Judg 3:10; 6:34; 11:29; 14:6, 19; 15:14; 1 Sam 10:10; 11:6; 16:13; 18:10; 19:23; 2 Chr 15:1; 20:14). To have God dwell within the believer and the believer within God is not a reference to some mystical experience, but to the fact that the believer partakes of the eternal life that characterizes God (1 John 1:2). Therefore, the earthly life of the Christian should manifest the qualities of the eternal life he or she has received.

This concept of the abiding life and love of the Christian in the Father and the Son, and their abiding presence and love in the believer, communicates that the “Christian’s relationship with God is not a series of encounters but a stable, continuous way of life” that begins with the new birth (John 1:13; 3:3; 1 John 2:29; 3:9; 4:7; 5:1, 4, 18).38 And that stable, continuous way of life with God is characterized by a vitality that is visible, just as fruit on the vine is the proof of vitality (John 15). By virtue of this new and vital life, other realities abide in the believer, such as love and the Spirit.

Because of this vital, new life that is born of God, the one who claims to remain or abide in him “ought” to walk (i.e., live) as Jesus did. So what specifically does it mean to live as Jesus did? The Jesus movement of the 1960s seemed to believe that to wear long hair and sandals encouraged one to live as Jesus did. But even “the Jesus people” recognized that to live as Jesus did goes far beyond fashion and other elements of the culture into which one happens to be born.

This new life that is based on Jesus’ atoning death is for “the whole world” (2:2), and so must transcend culture in significant ways. The blood of Jesus cleanses sin, but to love God means obedience to his revealed will, which Jesus accomplished perfectly, even though it meant he had to suffer the horrors of the crucifixion. Jesus was without sin because he won the struggle in the garden of Gethsemane over whether to obey God’s will and go to the cross or to turn away. Jesus won that struggle because he was completely committed to obeying God, a commitment completely motivated by love for others. To walk as “that One” walked means to live in unflinching obedience to God, which constitutes love for him and for others.

Theology in Application

Our Need for God

God is an inescapable part of human experience. Although called by many different names and conceptualized in many different forms, some concept of deity is present in every culture. Even the atheist must hold a conscious position of rejecting God’s existence, as opposed to living in a world in which there is simply no concept of God at all. And yet not every concept of deity can be true. Every human being needs to know the truth about who God is and how to have a relationship with him. While knowledge of other things may seem more relevant and pressing to some—things such as how to drive a car, balance a checkbook, make friends, and do our jobs well—knowing God is the most essential kind of human knowledge. For at the ultimate and inevitable end each of us must face, everyone will realize that there is nothing more important than knowing the God who created us and to whom we each return either in fellowship or under judgment. God wants us to know him, and he has revealed himself throughout human history, finally and most completely, in the incarnation as the human being we know as Jesus Christ.

Sin Blocks a Relationship with God

In the opening verses of the body of this letter (1:5–10), the apostolic author, whose knowledge of God as revealed in human form goes back to Jesus himself, establishes a basic principle: we cannot know God as God deserves to be known until sin has been defeated in our lives. It may be possible to know about God without dealing with our sin (and even possible to teach and preach about God), but it is not possible to have fellowship with God without acknowledging our sin and receiving his forgiving cleansing by the blood of Christ. As Lieu has put it, “Claiming not to have sin is not a matter of arrogant self-righteousness but of misrepresenting the very nature of God.”39

Now in 2:1–6, John brings that general principle to bear more specifically on the readers of his day. Even while, on the one hand, it is itself a sin to claim one has no sin, John also needs, on the other hand, to teach that it is important not to sin. In other words, the existential reality of our sin does not give a license to indulge in it, because God has revealed that he doesn’t want his creatures to sin against him or against each other.

John teaches that the proper attitude toward sin is to avoid it. But when we sin by commission or omission, whether intentionally or not, we can bring our sin to Jesus, our paraclete before the Father, who pleads his blood on our behalf. On that basis God will cleanse us of sin (see comments on 1:9).

John also teaches the universal scope of sin and Jesus’ atonement for it. Christ died not only for “our” sins, but for the sins of “the whole world.” This important point is relevant to how Christians engage with other religions in our pluralistic society today. There are many points of ethics and practice that Christianity shares with the other great world religions. If Jesus were only human and nothing more, his teachings could be put on par with those of other great teachers and philosophers. And while it may be right and good at times for the Christian church to join in common cause with other religions, it must never be done in such a way as to suggest that there are many different but equivalent roads to knowing God.

Monotheism Misunderstood

A misunderstanding of the monotheism embraced by the three great world religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) may confuse some so that they think we are all worshiping the same God just by different names or practices. That line of thought runs counter to what the NT teaches. When the Romans conquered the Greeks, they did not destroy Greek culture, but largely integrated it with their own. For their religious framework, this meant harmonizing the pantheon of deities by allowing that the same god or goddess was known by two different names. For instance, the Roman goddess Diana was identified with the Greek goddess Artemis, and their different functions merged.

But notice that when the apostle Paul went to evangelize the Greco-Roman world with the good news that God had become man, he did not say, “You Romans call him Jupiter, and you Greeks call him Zeus, but we call him Yaweh.” Even though Paul knew there is only one God, to identify him with Zeus or Jupiter would be to mix heretical cultural notions with what God had revealed about himself. Instead Paul says, “We are bringing you good news, telling you to turn from these worthless things to the living God, who made the heavens and the earth and the sea and everything in them” (Acts 14:15). This is not to say that God does not use the religious experiences of people from various cultures to bring them to himself in a true, saving knowledge of Jesus Christ. But religious experience apart from Christ is insufficient to know God truly as he has revealed himself.

We Don’t Get to Make Up Our Own Truth

The privatization and individualization of religious belief seem to lead people to believe that they are entitled to pick and choose their own religious truth. But when John states that Jesus atoned not for our sins only but also for the sins of the whole world (2:2), he excludes the argument that Jesus is truth for Christians only, but not for Jews or Muslims or atheists. Upholding the universal scope of the exclusive message of the gospel of Jesus Christ in an increasingly pluralistic world will be arguably one of the most difficult challenges to the future of the church.

Obedience Is Not Legalism

John moves from the basic principle that dealing rightly with sin is necessary for knowing God to the necessity of obedience. In 2:3–6 he specifies that to know God means to live as God says we should, because to think otherwise is a failure to recognize who God is and his right to have a claim on our lives. As discussed above on 2:3, God’s “commands” do not refer to a list of dos and don’ts, but should be understood in light of 3:23–24, where God commands Christians “to believe in the name of his Son, Jesus Christ, and to love one another…. And the one who keeps his commands remains in him [God], and he … in them.” Rather than legalism, obedience means living in God and he in us.

God’s love reaches out to his fallen creatures in Christ’s cross, with the goal of restoring them to living rightly as he created us to live. His love achieves that goal when we come to faith in Christ and, consequently, learn to love others. These are not onetime events, even though John stresses elsewhere the need to be born again (John 3:3). Furthermore, the use of the perfect tense where he refers to the new birth indicates that he assumes a Christian has been born again sometime in the past, but that fact has continuing meaning in the present and throughout life (1 John 2:29; 3:9; 4:7; 5:1, 4, 18).

Every day Christians must decide to live with faith in Christ in everything they do and say. Every word and act offer the opportunity to express love for another or not. Thus, Christianity is not only a matter of cognitive assent to the right doctrines, even though statements of faith are an important part of identifying ourselves with biblical truth. If we say we have been born again and have come to know God in Christ, we must either live in accordance with God’s revealed will or reveal ourselves as liars. If we say we are followers of Jesus Christ, we must live as Jesus did, with total commitment to obedience to God every day of our lives.