On a spring morning so bright that the city seems lit from below the pavement’s crust, I find myself at the end of West Eighty-ninth Street.*1 Riverside Drive broadens here to make room for the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, a tall colonnaded cylinder with a cakelike crown, and Riverside Park falls away below, leaving waves of yellow-green pollen that roll along the sidewalk and fill my eyes with tears. It’s an unusually tranquil spot. A bus pulls up and gives a bull-like snort as it kneels to let an elderly man lower himself to the curb. Down in the park a woman is hooting for her errant beagle, which answers with a hoarse yip. A toddler in the playground at the bottom of the escarpment is loudly demanding something. Suddenly a whir of bicycle tires pans past me and down along the steep path. Each distinct and identifiable sound reinforces the general feeling of tranquility.

Schwab Mansion, 1909

This does not seem like the ideal place from which to launch a fierce campaign against noise pollution, and yet in 1905, when Julia Barnett Rice moved into the handsome villa on the southeast corner of Riverside Drive*2 and West Eighty-ninth Street with her husband and their six children, she found the noise level intolerable and unabating.

Postcard of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, 1903. The Rice Mansion appears on the right.

The Hudson, at the moment a silvery platter bearing a single kayak, was then black with tugboats and barges bellowing through the day and night. Each horn gave off a low, tubalike blast of warning or greeting or just because. Together they massed into a never-ending brass choir that lifted off the river and rumbled through the stone mansions on Riverside Drive. Every few minutes, another freight train pounded down the tracks that ran along Manhattan’s western flank, trailing a plume of oily smoke. Living at the top of this cliff at the turn of the century meant feeling the clangor as a buzzing in your bones. Like any good Upper West Sider, Julia Rice channeled her annoyance into activism: She hired Columbia students to count tugboat toots; she generalized the issue, turning herself into an advocate for ruckus-addled hospital patients; and she formed the Society for the Suppression of Unnecessary Noises, which for a while had real political clout.

Today, the yeshiva that inhabits Villa Julia, as her solicitous husband, Isaac, dubbed the house, has allowed it to subside into quiet dilapidation. The graceful hodgepodge of red brick and white marble, with its elaborate porte cochère and a weathered relief of a Julia-like mother and her six children on the Eighty-ninth Street façade, is an ever-deteriorating relic of the Gilded Age. It looks as though the owners couldn’t make up their minds whether they wanted an austere Georgian mansion, a flamboyant Beaux Arts château, or a Renaissance palazzo, so the architects, Herts & Tallant, swirled them all together. In its some-of-this-and-some-of-that aesthetic, the house broadcast the habits of Julia and Isaac, who pursued a fantastically varied range of passions with expertise and élan.

Born into a Jewish family in New Orleans, Julia Barnett arrived in New York to attend Women’s Medical College, where she graduated with an M.D. degree in 1885, and promptly married Isaac Rice, a gentle, German-born lawyer. They shared a love of music—he published a set of waltzes under the title Wild-flowers and found time to write a book called What Is Music?, which attempted in under one hundred pages to synthesize all the world’s traditions into a “cosmical theory of music.” If this sounds like an amateur crackpot’s task, it’s worth remembering that, nearly one hundred years later, another Upper West Side Jewish polymath, Leonard Bernstein, took a stab at the same topic in his Norton Lectures at Harvard.

Isaac and Julia Rice Mansion

Rice made and spent enormous quantities of money in idiosyncratic ways. He invested in railroads, started a prestigious political journal, and became a defense contractor supplying the government with submarines. But his true passion and cause was chess. While Julia charged out into the deafening world to compel it to lower the volume, Isaac pursued tranquility by blasting a basement vault out of the rock. Down in his chess bunker, Rice developed a gambit, which he named after himself; it involved White sacrificing a knight in order to set up a stealth blitz by the rook. He was so taken with his innovation that he sponsored tournaments in which players had to use it, and he became such a benevolent figure that, on his death in 1915, the American Chess Bulletin devoted a supplement to his praise. (Later experts have felt less indebted: The 1996 edition of the Oxford Companion to Chess dismisses the gambit as “a grotesque monument to a rich man’s vanity.”)

The Rices were also unconventional parents. When their daughter Dorothy claimed she saw “no point in clogging my mind with things that everyone knew” and announced she was quitting school at twelve, her parents acquiesced. She went on to become a motorcycle racer, an aviatrix, and, echoing her father’s chess obsession, a bridge virtuoso. Her younger sister Marion died in 1990, and the Los Angeles Times printed an obituary whose opening sentence intimated a movie-worthy life: “Marion Rice Hart, who sailed a 72-foot ketch around the world and flew solo across the Atlantic seven times between the ages of 74 and 83, has died. She was 98.”

I linger on the Rices’ story because I feel as if I know these restless engines of the Jewish bourgeoisie: passionate activists, idealistic eccentrics, earnest participants in the city’s cultural life. Even in her concern for the precarious psyches of hospital patients, Julia Rice anticipated the torrents of mental-health professionals that later flooded the Upper West Side.

This is now a more moneyed area than it was thirty years ago, and in that sense it has come full circle, back to the enclave of affluence that the Rices settled. But, like them, the neighborhood still draws its energy from the arts and intellectual pursuits. A few random vignettes: Strolling along West End Avenue in warm weather, I stop to listen to some relentlessly practiced Brahms piano music crashing through an open window. In Zabar’s Café, a man consults the Metropolitan Opera’s season calendar on his iPad and tells anyone who will listen what shows they shouldn’t miss. A book-club night at Symphony Space attracts an overflow crowd to hear three novelists discuss W. G. Sebald’s sublimely arcane nonfiction novel The Rings of Saturn. Dog owners cluster in Riverside Park early in the morning, watching their pets tear around a hillside while they chat about Ibsen and canine psychology.

Novelists and musicians converged on Brooklyn in the early 2000s, making it the official epicenter of cultural hotness. But even after the influx of bankers, the Upper West Side still retains the foot soldiers of New York’s creative economy: theorbo-playing lawyers, standing-room regulars, theater mavens entitled to cheap seats for union members, freelance editors who work from their kitchen offices, violinists who like the quick late-night subway ride home from a Broadway pit or Lincoln Center, actors who’ve spent decades playing eyewitnesses on cop shows, percussionists who’ve filled their living rooms with drums and marimbas, Columbia professors who support their ceilings with columns of books, plus a whole army of ad producers, sound techs, lighting designers, choreographers, book-jacket designers, animators…I could go on. Artistic genres, social consciousness, and religious pursuits coexist in an amiable jumble. Last year, I attended a Yom Kippur service that took place in the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew, on the corner of West Eighty-sixth Street and West End Avenue: a thousand atoning Jews packed into a Christian sanctuary. When I slipped out for a bit and wandered around the building, I found a darkened theater on the second floor, where a handful of singers gathered around a piano and belted out Christian tunes by candlelight. “I heard there’s some kind of Jewish thing going on tonight, too,” one of the participants said between numbers. Then I followed the sound of a jazz combo up the stairs and found the group jamming in a top-floor practice room. In the basement, a few homeless people were bedding down in the shelter. Back outside, a Black Lives Matter banner hung on the side of the church.

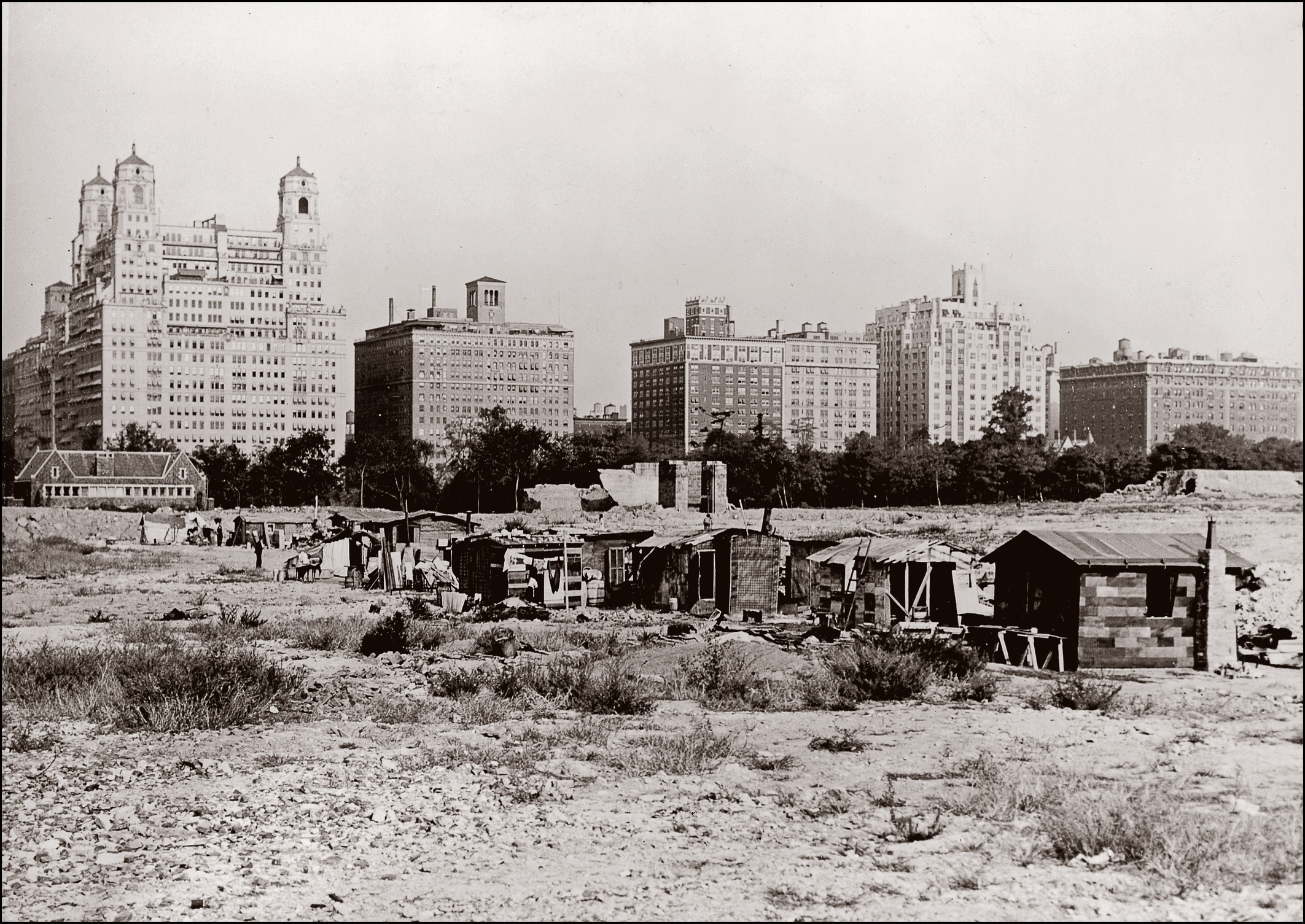

When Isaac Rice was scouting sites for his home, the area was a patchwork of promise and wilderness. Mansions popped up along Riverside Drive—the most sumptuous was Charles Schwab’s seventy-five-room full-block château between Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Streets—but they looked out over garbage-strewn ravines and industrial wastelands. In 1867, after decades of failed attempts to preserve various shoreline patches as parkland, property owners managed to get the cliffs beneath their houses set aside for Riverside Park and gave the job of designing it to Frederick Law Olmsted. But the residents’ desire for scenery collided with the need for a flat zone where the city’s dirty work could take place. The painter George Bellows captured that clash sensitively. In his turn-of-the-century views, elegantly dressed West Siders promenade along winding paths, gazing appreciatively at the ice-crusted Hudson and the far shore’s snow-spangled cliffs. The leisure-seekers doggedly ignore the moorings and garbage dumps lining the river.

My favorite of his many New York winterscapes, Snow-Capped River, from 1911, takes in the sweep of the Hudson, bounded on the far side by the whipped-cream heights of the Palisades. Tugboats and barges slice through hunks of ice, trespassing on the snowy idyll. But the clouds of hot steam have a wispy white beauty all their own; these working vessels provide a picturesque touch for the gentry and their dogs ambling up Riverside Drive. We can’t see the shiny new palaces on our side of the avenue, but we seem to be enjoying the view from one very expensive window. To Bellows, this genteel cliff-top trail provided a vantage point on the seasons. The spring scene, Rain on the River, sweeps from the romantic granite outcrop where Edgar Allan Poe rambled in search of inspiration, down past the pristine sod and gracefully corkscrewing pathways of Olmsted’s fledgling park, to the sooty, clanking railroad tracks and sludge-hued Hudson beyond.

Away from the river, the side streets*3 filled in with townhouses for the affluent, fantasias of carved polychrome brick and limestone trim that gave the neighborhood a reputation for architectural flamboyance. Whereas unremitting brownstone townhouses had given other parts of the city a reputation for mud-colored uniformity, here, the august critic Montgomery Schuyler enthused, “the wildest of the wild work of the new West Side had its uses in promoting the emancipation” of the row house.

Bloomingdale Road (originally Bloemendaal, in Dutch), the meandering country road toward Albany, had been paved, straightened, and widened in 1868. Known as the Boulevard, it was as gracious a street as an American could imagine in the nineteenth century. Ample carriageways ran in both directions, flanking a median shaded by elms, and le tout Manhattan converged there of a Sunday to clop up and down in cabriolets. In 1899, the street was rechristened Broadway,*4 one of the innumerable attempts to nudge along a real estate boom with nomenclature. Farther east still, the Ninth Avenue El, which opened in 1871 and ran steam-powered trains along a viaduct above what is today Columbus Avenue, linked the Upper West Side with the city proper, unstoppering new floods of money. All this new affluence, transit, and real estate—plus the construction of Central Park—was supposed to transform a rocky, rural area into a splendid precinct, set on a picturesque plateau and bounded by noble parks. “Assuredly this region will be the site of the future magnificence of this metropolis,” wrote an early neighborhood champion in 1865. The boosters were right that the wealthy would reinvent the West Side in their image. It took a little longer than they thought, but by 2000 or so, the job was done.

The Dakota broods over frozen Central Park lake, circa 1900.

In the late nineteenth century, sumptuousness advanced slowly and unevenly. Squatters built huts between millionaires’ residences, and the castlelike Dakota on Central Park West at Seventy-second Street looked out on a grid of stony fields and freshly painted townhouses. The building had its own power source; electricity came to the rest of the avenue only in 1896. When the area did begin to develop with dizzying speed in the 1890s, change was fueled by a transformative power that not all developers had fully understood: Jews.

From its earliest days as a strip of settlement along the Bloomingdale Road, the Upper West Side has had, and still has, a startlingly varied population. Turbulent eddies of history deposited Southern blacks, Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Russians, and Ukrainians. The Jewish presence fluctuated, but ever since the Rices’ days, it never stopped shaping the neighborhood’s ethos: politically engaged, culturally aware, and slightly sanctimonious. The Rices lived in their mansion for less than the time it took to build it. In 1907, Isaac’s travel schedule and his finances brought home the lunacy of maintaining a Manhattan villa. The family moved to the new Ansonia Hotel, on Broadway between Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth Streets, a hyper-modern marvel that offered residents luxuries they had never thought to crave, like air-conditioning and, for a few years, geese raised on the rooftop farm.

Even before the townhouse-ification of the Upper West Side was complete, it was already passé. The cost of maintaining a multi-story residence had become prohibitive for all but the hyper-wealthy, and developers saw the economic logic of tearing down a cluster of four-story homes and putting up a single eighteen-story apartment building instead. Photographs of the neighborhood from the early decades of the twentieth century show a skyline that looks like a bar graph: clumps of stubby columns interrupted by the occasional big jump. Some blocks have remained that way. But by the 1920s, the apartment building had become the norm. Especially along West End Avenue, rooflines and cornices more or less lined up to create uniform street fronts that were gray, noble, and formidable, resembling the residential quarters of Vienna and Berlin. The best addresses boasted archways and courtyards. Most made do with a few perfunctory signs of graciousness, lending a patina of delicacy to stolid structures and thick-walled rooms.

Those grave buildings proved to be the enduring backbone of the Upper West Side. Built for the affluent, with maids’ rooms, dumbwaiters, and marbled lobbies, some eventually housed the out-of-work and underpaid. Many of these solid constructions survived neglect and eventually lent themselves to luxurious upgrades. Hitler’s rise in Europe populated this American facsimile of a European city with refugees, survivors, and émigrés. The combination of sturdy architecture and traumatized lives gave the Upper West Side a wistful character that has never quite dissipated. More than most parts of the city, it is shadowed by memory.

The walk south*5 brings me to Isaac Bashevis Singer territory. The Yiddish-language writer who bestrode the Old World and the New also trudged the length and breadth of the Upper West Side. He defined it as the stretch between Seventy-second Street and Ninety-sixth Street, flanked by the two parks, but he is construing the borders too narrowly. Some taxonomists would extend the area as far north as 110th Street; most would go as far south as Fifty-ninth Street, using the length of Central Park as the measuring stick, which would include the area of doomed tenements once known as San Juan Hill, and now called Lincoln Center. Singer made the rounds of his regular lunch spots, Eclair and Famous Dairy Restaurant, both on Seventy-second Street, and the American Restaurant, which was actually a Greek coffee shop, on West Eighty-fifth. All of them are now gone, like so much of what Singer describes. Born out of the ashes of European Jewry, his work now reads as a necrology of the Upper West Side. “Almost every day on my walk after lunch, I pass the funeral parlor that waits for us and all our ambitions and illusions,” he wrote. “Sometimes I imagine that the funeral parlor is also a kind of cafeteria where one gets a quick eulogy or Kaddish on the way to eternity.”

A ruined mansion on West Eighty-sixth Street between Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue, where the Belnord now stands, 1890

The Belnord, 225 West Eighty-sixth Street

Singer lived for decades in the Belnord, a massive limestone palazzo that was built in 1909 and occupies an entire block from Eighty-sixth to Eighty-seventh Street, and from Broadway to Amsterdam Avenue. In his day it sported a distinctly Old World air of decrepit grandeur; now it is the definition of deluxe. Singer described the area he patrolled in tender detail, and he distanced himself from his characters by means of a few blocks. He housed Boris Makaver, the protagonist of his novel Shadows on the Hudson, in a different courtyard château that seemed at once solidly anchored and capable of drifting across oceans of memory:

The apartment building into which Boris had just moved reminded him of Warsaw. Built around an enormous courtyard, it faced Broadway on one side and West End Avenue on the other. The cabinet de travail—or study, as his daughter Anna called it—had a window overlooking the courtyard, and whenever Boris glanced out he could almost imagine he was back in Warsaw. Always quiet at its center, the courtyard enclosed a small garden surrounded by a picket fence. During the day the sun crept slowly up the wall opposite. Children ran around on the asphalt in play, smoke rose from the chimney, sparrows fluttered and chirped. All that seemed to be missing was a huckster carrying a sack of secondhand goods or a fortune-teller with a parrot and a barrel organ. Whenever Boris gazed into the courtyard and listened to its silence, the bustle of America evaporated and he thought European thoughts—leisurely, meandering, full of youthful longing. He had only to go into the salon—the living room—to hear the din of Broadway reverberating even here on the fourteenth floor. Standing there watching the noisy automobiles, buses, and trucks and catching the subway’s roar from under the iron gratings, he was reminded of all his business affairs and thought of telephoning his broker and arranging to meet his accountant.

Singer can only be describing the Apthorp, a full-block colossus between Seventy-eighth and Seventy-ninth Streets*6 that for decades housed both wealthy celebrities (like Al Pacino) and more modest professionals enchanted by the building’s combination of grand spaces and regulated rents. Through the 1990s, more and more apartments were decontrolled and rents multiplied like a drug-resistant superbug. In 2008, new owners converted the building to condominiums, turning it into a bastion of the ultra-rich and also the object of an extravagant adieu by the writer Nora Ephron. “I lived in the Apthorp in a state of giddy delirium for about ten years,” she wrote. “The tap water in the bathtub often ran brown, there was probably asbestos in the radiators, and the exterior of the building was encrusted with soot. Also, there were mice. Who cared?” What she did care about were the feverish rents and the courtyard full of “idling limousines waiting for the new tenants to be spirited away to their fabulous midtown careers.” And so Ephron, one of the most privileged persons on the planet, was forced out of her apartment, and the Upper West Side, by an even more privileged cohort, the People Who Ruin Everything.

Courtyard of the Apthorp, 1905

Maybe because the neighborhood has such gravitas and yet contains such a multitude of agitated lives, change and permanence intensify each other here. Sift through old photographs, or through the memories of longtime residents, and you can make out the layered ghosts on every block. Even casual conversation acquires an elegiac tone, and every observation that a new store is opening contains within it the recollection of all the ones it displaced. Is that a function of the West Side’s ingrained Jewishness? Jewish sacred texts and prayers are cornucopias of lists: catalogs of ancestors, plagues, sins (both committed and hypothetical); forms of death (actual and potential); invocations of the past and terrors for the future. Children grow up to the hum of recited memory. Jews recall vanished towns in Europe, the witticisms of long-dead rabbis, the customs of communities that were extinguished generations ago. These are memories of trauma and dislocation, but the Jewish experience in the United States shows that wistfulness can thrive even during decades of peace and relative stability. The Upper West Side, the American Jerusalem, provides its own steady drip of loss. My wife grew up in two different apartments two blocks apart, and she can still itemize the businesses along the west side of Broadway between Eighty-sixth and Eighty-seventh, circa 1975: Barton’s Chocolates, a tobacconist, Chock Full o’ Nuts, Herman’s stationery store, a shoe repair, and a lingerie shop. That collection of storefronts has been replaced by exactly two establishments: a Banana Republic and a bank.

Railing against change is often an exercise in self-indulgent nostalgia, and we wind up mourning establishments we never patronized or buildings we never really liked. But there are also good reasons to kvetch. One day a few years ago I noticed that a new wound had opened on the east side of Broadway, across from the Apthorp, between Seventy-seventh and Seventy-eighth Streets.*7 One of the last full blocks of low-rise buildings and small shops, it had suddenly acquired that familiar, ghost-town look that precedes obliteration. Shortly before, the restaurant Ruby Foo’s, Manhattan Diner, a Così sandwich bar, a tae kwon do school, the Curl Up and Dye hair salon, a watch-repair service, a travel agency, a jewelry-making school, a pizza joint, a Subway, World of Nuts, and a jewelry shop crammed into two hundred feet of frontage. A dozen businesses in all, catering to vanity, hunger, creativity, and the pursuit of health, had vanished. It was a common enough tale that I knew how it would end: A teeming commercial ecosystem would give way to a pair of vast establishments, stretching from corner to mid-block.

Broadway’s small businesses—bookstores, shoe-repair shops, florists, quirky clothiers, and so on—were being choked by the spread of a toxic commercial monoculture. That wasn’t some inexorable Darwinian process but the desired result of landlords and developers, who always prefer to sign a long-term lease with a clean, quiet, stable, and heavily capitalized corporation rather than risk renting to an amateurishly managed boutique or an odoriferous diner. Sadly, cleansing the sidewalks of small establishments changes the rhythms that give Broadway its character. Businesses and residents pay fortunes to be immersed in the irregular, contrapuntal flow of foot traffic: people striding to work, pausing to scrutinize a restaurant menu, slowing down to covet a pretty pair of earrings, or herding kids in little white uniforms and color-coded belts to a session of martial arts. All this human activity so easily drains away. Who wants to walk along a boulevard where the shop windows offer nothing more tantalizing than mouthwash and free checking? The low Broadway building was—and is—an endangered species. Every sighting feels provisional, and coming across a full block of them is like glimpsing a whole pride of pumas. I believe in height and density—they are the sources of New York’s strength—but not if they are evenly slathered across areas that were once more varied.

In Manhattan, where the value of land is multiplied by the value of the air above, low-rise structures are inherently wasteful. Developers look at a short building on a site where a tall one is permitted and they see hundred-dollar bills flapping away in the breeze. Yet those are the spots where the street lightens, the horizon opens, and the pace slows. The city suddenly seems a little more manageable and humane. The Broadway skyline on the Upper West Side is a jagged thing, a parade of elephantine apartment palaces and tiny, humble stores. That profile is the record of the avenue’s piecemeal evolution, as a farm here and a shed there gradually gave way to the next temporary placeholder: a tenement, a tower, a supermarket.*8 Conventional planning wisdom holds that tall buildings should line the avenues to leave the side streets low at mid-block, which is fine, except that not every boulevard is created equal. Park and West End Avenues were shaped by fell swoops of development that gave them their distinctively gracious uniformity; Broadway was not.

The architect and provocateur Rem Koolhaas once suggested, in a polemical exhibit called Cronocaos, that the world should routinely clear out the underbrush of junk architecture. The habit of preservation, he argued, is keeping cities sluggish and out of date. Koolhaas was once a connoisseur of New York’s contradictory quirks; these days, he has only to stroll up Broadway on the Upper West Side to observe the progressive erasure he advocates doing its baleful work. Here the preservationist impulse is needed not in order to cherish the past but to safeguard the vibrant present.

A few low buildings remain that way, for now, thanks to the Zabar family, which over the years bought up properties and left them alone. The four-story complex that houses Zabar’s, the famous food emporium, displays practically archaic dimensions, like an old wooden house with doorways that force an adult man to duck. Christopher Gray, long the Times’s architectural historian, who knows every limestone lintel’s backstory, outlined the history of the building in a 2002 column, and the tale brings out the threads that bound the whole area together in the first half of the twentieth century. In 1919, a Russian Jewish immigrant named Aaron Chinitz leased the row of derelict tenements, gave it some class and a Tudor makeover, and reopened it in 1920 as the irreproachably un-Jewish-sounding Calvin Apartments. The renovated complex, Gray wrote, was “entered through a one-story cottagelike structure that faced 80th Street and had leaded casement windows, Gothic decoration, a beamed ceiling and decorative downspouts. Advertisements promised ‘dining service on premises’ and offered two-room apartments for up to $165 a month, ‘all bright cheerful rooms’ with radiators set in alcoves and built-in oak settees.” Chinitz was the impresario of Singer’s Upper West Side: He, too, lived in the Belnord, and he had opened the Tip Toe Inn, a delicatessen at the corner of Broadway and West Eighty-sixth Street that closed in the sixties and still today makes Jews of a certain age sigh at the memory of its apple pancakes. In 1941, Saul Zabar, a Jewish immigrant from Ukraine, opened a one-window grocery on the ground floor of Chinitz’s Calvin Apartments, founding a food dynasty. His sons eventually bought the whole building, preserving its English-village façade and growing the business into the neighborhood’s gastronomic nerve center, even now supplying the intelligentsia (and everybody else) with smoked sable and pickled herring in cream sauce.*9

Over the years, the Upper West Side’s identity shifted this way and that between coexisting poles: bohemian and stolid, comfortable and marginal, crime-ridden and somehow serene. I have lived on the Upper West Side for most of my adult life, and whenever I return from a trip out of town, especially at the end of a summer weekend, the neighborhood seems to pulsate and judder. Eddies of heat and music and talk ricochet off the asphalt, and if sanitation crews haven’t come through for a while, homeless people have rifled through the piled trash bags, coating the sidewalks in reeking household debris. But if I come home from an expedition to Midtown or Lower Manhattan, I almost feel like I’m hopping off a commuter train in some verdant Hudson Valley suburb, where the decibel level is lower (thanks, Julia Rice!), the side streets greener, the air cooled by its flanking parks.

I treasure the sense that my slice of Manhattan keeps heading in multiple directions at once. The oil spill of money that has washed over Manhattan has made it among the city’s—and therefore the world’s—priciest zip codes, but along Columbus Avenue, wealthy co-ops coexist with middle-income towers, low-income housing projects, and rambling rent-controlled pads. In 1969, Nicholas Pileggi, who was then cranking out magazine pieces for hire but went on to write the screenplay for Goodfellas (and to marry Nora Ephron and live in the Apthorp), profiled the Upper West Side for New York magazine. His article described a neighborhood that threatened simultaneously to collapse into anarchy and also to become as manicured and dull as the Upper East Side. Crime was high, but so were prices. (Both would later shoot much higher.) During the postwar housing shortage, landlords had chopped single-family brownstones into miniature apartments. Some would erect a Sheetrock partition down the middle of a prewar “classic six” (two bedrooms, formal dining room, living room, a kitchen large enough to eat most meals in, and a maid’s room, plus a couple of bathrooms), turning it into two cramped threes, and then would vie to see how little they could spend on maintaining the bastardized result. Consequently, the wealthy and the practically indigent shared the same blocks, coffee shops, and subway stations, living apparently incompatible lives within inches of one another. “The residents of Manhattan’s Upper West Side make a yeasty polyglot society that is as ethnically diverse and economically varied as any area in the United States, with the possible exception of Honolulu,” Pileggi wrote.

It is a neighborhood, or series of neighborhoods, where certain recently renovated brownstone blocks have already taken on the hushed tone of affluence, while around the corner young Puerto Rican men, wearing sleeveless underwear and religious medals, spend most of their Saturdays rubbing Simoniz wax into six-year-old automobiles. It is an area in which Mrs. Jacqueline Onassis sends her son to a school that is within a block and a half of a Japanese supermarket, an Israeli coffee house with a floor show, a gypsy palmist, a hardware store specializing in “Bueno Bargains,” an excellent Jewish delicatessen (Gitlitz), a pizzeria, a Lebanese restaurant (Uncle Tonoose) and a religious-articles store that sells evil-eye repellents, love potions and numerology books….It is an area that houses, besides many Russian, German, Polish, black and Puerto Rican residents, substantial numbers of Japanese, Chinese, Mexicans, Haitians, Irish, English, Dominicans, Norwegians, Swedes, Czechoslovaks, Austrians, Italians, Canadians and Midwestern Americans.

Pileggi’s article expressed the anxiety that unstoppable market forces were wiping out all this variety—that the neighborhood was too inherently wonderful to remain acceptably crappy. And yet for a long time it remained one of the city’s most dangerous neighborhoods. The year his story appeared, 986 people were murdered in New York, nearly double the number five years before. Still, that number would soon come to seem quaintly low, as the city’s population dropped and crime leaped. By 1989, when I moved to Morningside Heights as a Columbia graduate student, drugs and violence were strangling the city, and the next year the number of murders peaked at 2,245—dozens of corpses hauled off sidewalks and out of blood-spattered apartments, week after week after week. That airborne murder rate left a contrail of other crimes. New Yorkers were being raped, beaten, mugged, and robbed, their apartments burgled, their cars stolen, their lives hemmed in by fear. Those two decades of decline have become mythologized in the story of New York as a frontier of liberty, when punk music and graffiti art thrived and the coffee wasn’t worth spending money on anyway. I, too, fell in love with the city during my first, impoverished years here, and I don’t want to overstate its miseries or shortchange its pleasures, which were plentiful. But I also remember headlines like this one, from July 27, 1990: STRAY BULLET CLAIMS ANOTHER NEW YORK CHILD—the third that week.

While crime rose unflaggingly, economic fluctuations whipped the neighborhood back and forth so quickly that residents weren’t sure whether to fear gentrification or decline, so they worried about both at once. Yuppie boutiques opened, then closed. In the 1980s, Columbus Avenue briefly turned into a strip of loud-music and high-priced restaurants and bars, which shut down when the money ran out.

The Upper West Side has always contained extremes of wealth and poverty. Julia Rice could look out of her bedroom window at the shanties that lined the railroad tracks along the Hudson. Today, the shortest route to Central Park from a pair of luxury towers on Broadway at Ninety-ninth Street runs through a public-housing project; heading for Riverside Park means jogging down a block of single-room-occupancy buildings that take overflow from the city’s shelter system. My route brings me to the historic epicenter of those contrasts: the San Remo, Emery Roth’s twin-towered Xanadu on Central Park West*10 at Seventy-fourth Street. In a case of spectacularly bad timing, the San Remo began construction in 1929, part of the last climactic burst of luxury building before the Depression barreled into the neighborhood.

The San Remo, 145 Central Park West

Successful Jews, unwelcome on the East Side, migrated to the West Side, where their freshly made fortunes took a while to dwindle. In 1930 there were still enough affluent Jewish families to constitute a market for the fanciest residences. Only a generation removed from Lower East Side peddler’s carts, the textile merchants and fashion moguls who converged on Central Park West could afford not just comfort and leisure but a glittering life. They furnished their living rooms with Steinways and Victrolas. They bought concert subscriptions and paid for music lessons and contributed to progressive causes, though not necessarily to synagogues. Like the Rice kids, the offspring of these affluent families were brought up according to the most enlightened science of child-rearing, usually more by nannies than parents, who were busy with their own work and social lives. Two of these gilded children of the garment trade moved into the brand-new San Remo in 1930: Diane Arbus, who grew up to be a photographer of urban eccentrics, and Stephen Sondheim, whose musicals explored the discontents and neuroses of the upper middle class. Arbus’s parents owned the fancy Fifth Avenue fur store Russeks and lived in a fourteen-room apartment facing the park. Diane used it as a launching pad for water balloons that would soak passersby. Sondheim’s family had slightly more modest resources, and they made do with fewer rooms and a less verdant view.

The Jews who settled the Promised Land of Central Park West found that their wealth never sufficed to buy entrée into Knickerbocker society or the most prestigious clubs. So they created their own parallel institutions, their own channels of secular prestige. These included societies, schools, and summer camps that were not overtly Jewish but were patronized almost exclusively by Jews. Among them were Camp Androscoggin, in Maine, where Sondheim spent his summers (and so, some years later, did my father), and the Ethical Culture School on West Sixty-fourth Street, which Sondheim and Arbus both attended in the 1930s. Founded by a German-born rabbi’s son, Felix Adler, in 1878, the Ethical Culture School was a pillar of non-religious Jewry. As a teenager, Adler was already being groomed to succeed his father as rabbi of the ultimate establishment synagogue, Temple Emanu-El, on Fifth Avenue. But then he went off to study at the University of Heidelberg and came back imbued with Kantian ideals and the conviction that ethics were best kept separate from religion. Adler devoted his life to instilling values of tolerance, universal dignity, and social justice, without resorting to ancient texts or rabbinic precedent. That made his school the perfect institution for a social group that treasured Jewish values but weren’t so crazy about being Jews.

“I never knew I was Jewish when I was growing up,” Arbus recalled, many years later. “I didn’t know it was an unfortunate thing to be! Because I grew up in a Jewish city in a Jewish family and my father was a rich Jew and I went to a Jewish school, I was confirmed in a sense of unreality.”

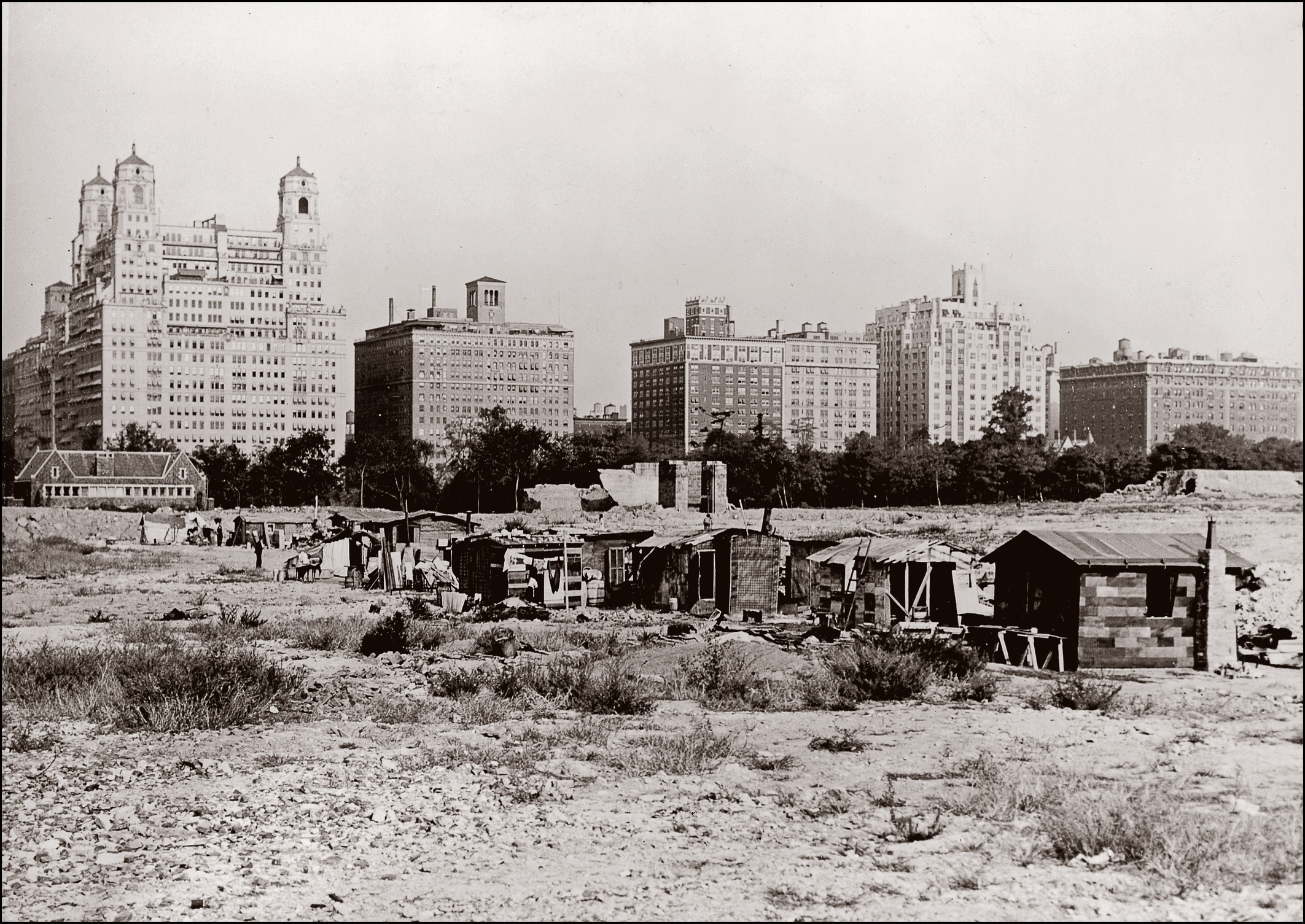

A squatter’s encampment in Central Park during the Depression

At that time, the Central Park that Arbus looked over from her windows was not the landscape of manicured wilderness and jade-green lawns it is today but an urban dust bowl. Until 1930, a pair of adjoining reservoirs had stretched from Seventy-ninth to Ninety-seventh Street. Modern conduits made them obsolete, and the lower section was drained and partially filled in with construction debris. In that great rectangular pit (where the Great Lawn is today), the Depression’s victims erected an encampment of lean-tos, an enclave of wretchedness equidistant from Fifth Avenue and Central Park West. For Arbus, that weird no-man’s land in her vast front yard offered her virtually the only childhood glimpse of poverty she had, and it dramatized the isolation of the fur-lined cocoon that was her life. Later, she told Studs Terkel:

I remember going with this governess that I loved…to the park to the site of the reservoir which had been drained; it was just a cavity and there was this shanty town there….This image wasn’t concrete, but for me it was a potent memory. Seeing the other side of the tracks holding the hand of one’s governess. For years I felt exempt. I grew up exempt and immune from circumstance. That idea that I couldn’t wander down…and that there is such a gulf.

Arbus once again found herself wandering in Central Park in 1962, with her camera this time, when she came across a skinny seven-year-old boy dressed in a sailor suit and playing with a toy hand grenade. Then nearly forty, she hung around watching the kid, annoying him with her camera, until he made an exasperated face, his eyes zombie-like, his mouth stretching into a froglike grimace, the fingers of one hand clutching the realistic little bomb, the others curled into a horrible rictus. That shot, selected from among a contact sheet’s worth of goofy poses, turned the scrawny boy into a symbol of the country’s crazed militaristic obsession and made Arbus the poet laureate of American weirdness. Central Park plays its role, too. Irradiated with bleached light all around the kid’s circle of stippled shade, the park could almost be a landscape caught in the last moment before it’s blasted away. In the middle distance, a darkly dressed woman holds the hand of a little girl in a white frock, who balances on a curb; another grown-up pushes a smaller child in a pram. Those children could all be Arbus in the Depression years—blithe, careless, unaware of the catastrophic wind rushing through the trees.

Sondheim grew up similarly insulated from his Jewishness and from the knowledge of want. The family apartment was a place of glamorous self-invention, where his parents, Herbert and Janet, known as “Foxy,” acted out a carefree marriage that ended abruptly when Stephen was ten. According to Sondheim’s biographer Meryle Secrest, Herbert learned to play seven or eight basic chords at the piano, enough to entertain their frequent guests by banging out a stream of pop songs. Sondheim’s mother held court. She “had a knack for gathering people around her, and a staggering amount of chutzpah,” Secrest writes, “the kind of person who could talk a jeweler like Van Cleef and Arpels into lending her a priceless necklace and matching earrings to wear for the evening….One can easily see why Foxy Sondheim had decided that the San Remo was the perfect background for the sophisticated life she wanted to have.” The pampered boy’s beat took him to Central Park, to Ethical Culture, and to his friends’ homes. It certainly did not take him a ten-minute walk from the San Remo to an area in the West Sixties called San Juan Hill, whose destruction helped launch his career.*11

Herbert Sondheim walked out of his marriage in 1940, and Foxy and her two boys abandoned the San Remo. Seventeen years later, Stephen Sondheim wrote the lyrics for West Side Story, which was set in the tumbledown violent streets just blocks from where he spent his cushioned childhood. In the extended dance sequence that opens the movie version, rival gangs sprint and leap through vacant tenement-lined streets, into high-walled dead ends, and over mountains of debris. Between the time the show opened on Broadway in 1957 and when the movie was shot on location, San Juan Hill had been condemned to mass demolition.

In later years, Sondheim admitted to some sheepishness about the lyrics he had contributed to West Side Story, which in retrospect didn’t feel gritty enough. “I had two street kids singing, ‘Today the world was just an address, a place for me to live in,’ ” Sondheim marveled. It’s hard to imagine that even if he had opted for rougher prosody he would have gotten terribly close to the idioms of San Juan Hill, where Puerto Rican Spanish merged with African American dialect. There’s rich irony in the fact that Leonard Bernstein paid tribute to the neighborhood’s Latino roots in his hip-shaking score and then in 1962 conducted the inaugural concert at Philharmonic Hall, which was built on the rubble of Riff and Tony’s turf.

Until the 1930s, the neighborhood west of Amsterdam Avenue, between Fifty-ninth and Sixty-fifth Streets, contained the city’s largest black population, along with a significant minority of whites, and it was famed for its street fighting and race riots. If the Central Park shantytown was a symptom of a country temporarily in free fall, San Juan Hill seemed to concentrate the city’s perpetual discontents. When right-thinking reformers came to inspect, they found thousands of desperately poor families jammed together in conditions that shamed a modern city: rats galloping through airless tenements made of brittle brick. “Old-law tenements stand, blowsy and run-down, in silent shoulder-to-shoulder misery, full of filth and vermin,” the Times’s music critic Harold Schonberg wrote in 1958, making the case for the construction of Lincoln Center. What those shocked outsiders missed, of course, was the intricate network of economic and human relationships that made the squalor tolerable and made the area feel like home. In any case, Schonberg was castigating a neighborhood that was already doomed. A cadre of planners, led by the master builder and slum-clearance lord Robert Moses and cheered on by much of the mainstream press, had decided to raze the area and start from scratch.

“Why Lincoln Square?” Moses rhetorically asked a banquet room full of construction executives in 1956. “Because these sixty-odd central, diseased and rapidly deteriorating acres can be rebuilt and made healthy only by condemning land and selling it to sponsors….No plasters, nostrums and palliatives will save this part of town. It calls for bold and aseptic surgery.”

Lincoln Square may have been a slum, but it was a slum full of bohemians and distinguished artists, some of whom mobilized to block the destruction and mourned the area once it was lost. The neighborhood looked thrillingly scary to visitors—and did indeed have plenty of actual horrors—but it also incubated a complicated cultural life. Thelonious Monk grew up at 234 West Sixty-third Street, and his biographer, Robin Kelley, writes: “Stories of crime and violence dominated newspaper accounts of San Juan Hill. The neighborhood made great copy for voyeuristic whites fascinated by popular images of razor-toting, dice-tossing, happy-go-lucky Negroes. What the papers rarely covered was San Juan Hill’s rich musical culture.” Until the Harlem Renaissance, the area “boasted the largest concentration of black musicians in the city.”

As Moses saw it, the people who lived on the West Side were merely inconveniences. Their homes were “worthless structures,” their turf a blank canvas on which to paint the gleaming future. Culture was what took place onstage, not in the street. Monk didn’t see it that way: He kept returning to his old home after each tour, even once the demolition got going and parts of the neighborhood resembled Berlin in 1945. Finally, when walking those blocks felt too much like camping out in a war zone and breathing in the dust of destruction, he gave up. Only in 1987 did his music manage to wriggle back into the old neighborhood, with the founding of Jazz at Lincoln Center.*12

After twenty-five years of hanging around Lincoln Center, I still savor its lingering magic. Half an hour before curtain, as dusk falls on the travertine village levitating just above the street, the great white boxes glimmer, the fountain’s spray creates an illuminated corona, and crosscurrents of humanity flow across the plaza. Defiantly rumpled students lope to discounted seats. Women stab the pavement with sharpened heels. Europeans make entrances under the impression that gowns and tuxes are still de rigueur at the opera. I haven’t lost my jolt of delight in the way the Met’s showy staircase gives the arriving audience its moment on a stage, or the way the costume-jewelry chandeliers get sucked up into the ceiling of the auditorium as the house lights dim.

Lincoln Center

It used to be that as soon as the performance started, the plaza cleared out. But these days there’s always something happening—someone taking selfies or irritating the security guards by balancing on the lip of the fountain. This sixteen-acre round-the-clock arts compound keeps churning out culture. More than twelve thousand people use its basement rehearsal rooms and dingy offices and Juilliard classrooms, and on a busy Saturday, thirty thousand ticket-buyers come and go. There are few more effective fusions of indoors and out—or of classical and popular arts—than a summertime intermission, when audiences drift out onto the balconies of the various halls and look down on dancers honing their merengue, backed by a live band, at Midsummer Night Swing.

What affects me most about Lincoln Center is the phenomenal aspiration it represents. Its scale speaks as much of America’s mid-century cultural insecurity as of its pride. In the fifties, New York was still getting used to being a world capital of culture, and its leaders were anxious to show that the city could value the stuff as much as money or military might. Lincoln Center was, among other things, a move in the Cold War prestige game. In today’s cultural climate, where land is precious and the arts have to fend for themselves, it’s hard to imagine clearing so much Manhattan real estate for people to dance and sing.

It began as the brainchild of John D. Rockefeller III in 1955, at a time when the New York Philharmonic was about to be evicted from a dilapidated Carnegie Hall and the Metropolitan Opera had outgrown its creaky West Thirty-ninth Street home. Erecting a sleek new enclave for the arts and inserting it into the teeming West Side tenderloin would solve a barrage of problems at once. It would provide a home for the orchestra; it would allow the Metropolitan Opera to modernize and expand; and it would gather the city’s major performing-arts institutions in a monumental space, appropriate to the cultural capital of a growing American empire. Lincoln Center was conceived to be selectively democratic: sealed off from the low-income neighborhood around it, but welcoming to any citizen with the inclination to climb an actual and metaphoric stairway and partake in the finer performing arts. The hope among arts leaders, planners, and philanthropists was that the benighted mass of Americans might eventually be made less philistine and that a new performing-arts center would serve as an elevating beacon. “Many of the little men and women have still to be sold on culture,” Moses scoffed. Lincoln Center was built to close the deal.

As the idea was taking shape, the conclave of architects and consultants who were called upon to imagine it were unanimous in seeing it as a cloister of sorts: “For the arts and for music one needs to get out of the maelstrom and into a quiet place,” they believed. What was required was “an area isolated from the hubbub of New York City.” The center would be a special place, “concentrated upon an inward space and inward-looking.” That did not please the urbanist Jane Jacobs, who thought such an acropolis would quarantine culture in a cold citadel. In a landmark 1958 article for Fortune magazine, “Downtown Is for People,” she wrote:

This cultural superblock is intended to be very grand and the focus of the whole music and dance world of New York. But its streets will be able to give it no support whatever. Its eastern street is a major trucking artery where the cargo trailers, on their way to the industrial districts and tunnels, roar so loudly that sidewalk conversation must be shouted….

And what of the new Metropolitan Opera, to be the crowning glory of the project? The old opera has long suffered from the fact that it has been out of context amid the garment district streets, with their overpowering loft buildings and huge cafeterias. There was a lesson here for the project planners. If the published plans are followed, however, the opera will again have neighbor trouble…the towers of one of New York’s bleakest public-housing projects.

The architect Wallace Harrison convened the leading lights of American modernism: Harrison’s partner, Max Abramovitz, for Philharmonic Hall, Eero Saarinen for the Vivian Beaumont Theater, and Philip Johnson for the New York State Theater. They were determined to make Lincoln Center a democratic stronghold of the arts. Those were years when culture and mass media reinforced each other’s power, and classical-music record sales were booming. At the old Met, the social register dominated the “golden horseshoe” of private boxes; the new house had more mid-priced seats, and the other theaters did away with private family boxes altogether. And nearly half of Lincoln Center was open to the sky, creating a civic space for which no tickets were required.

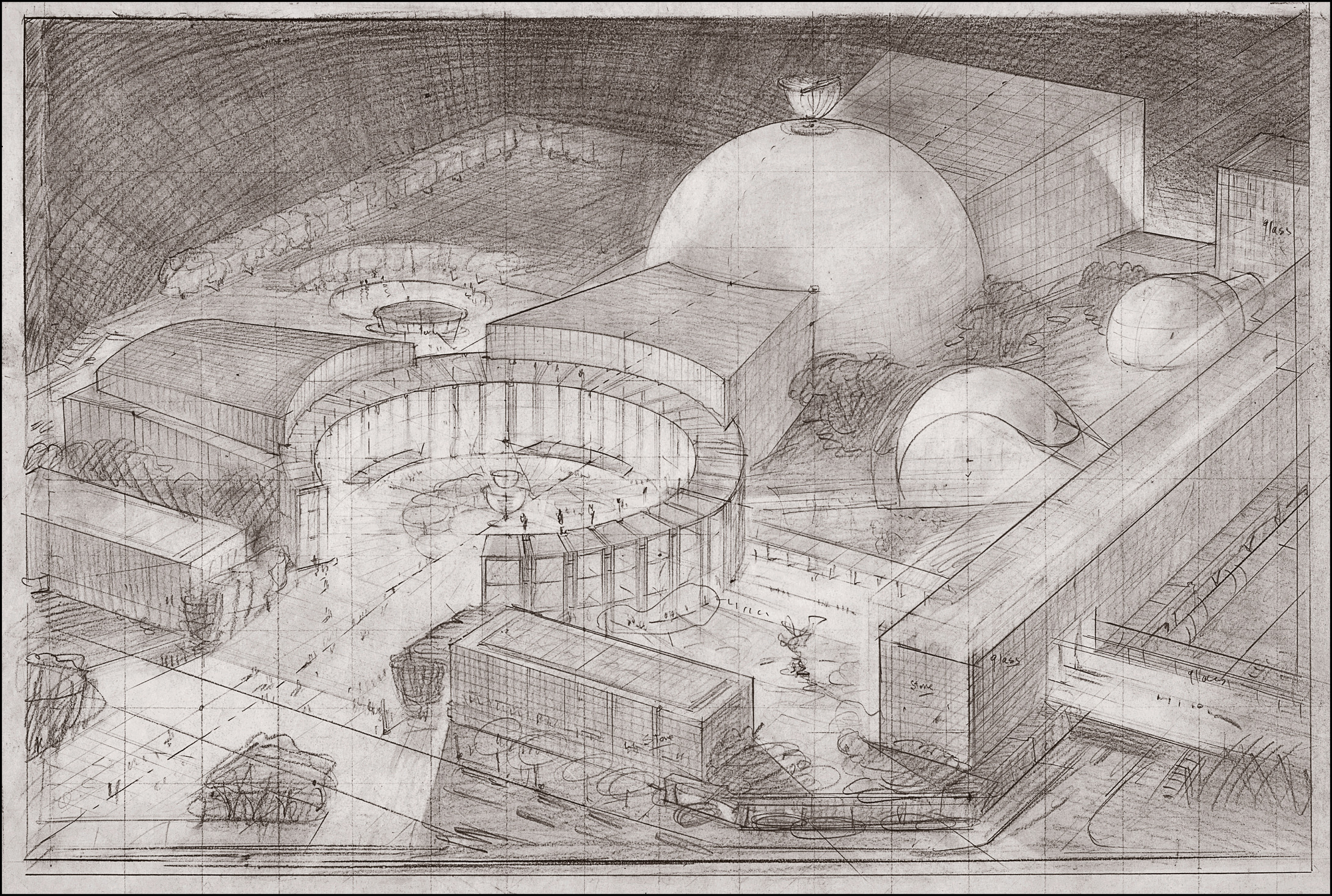

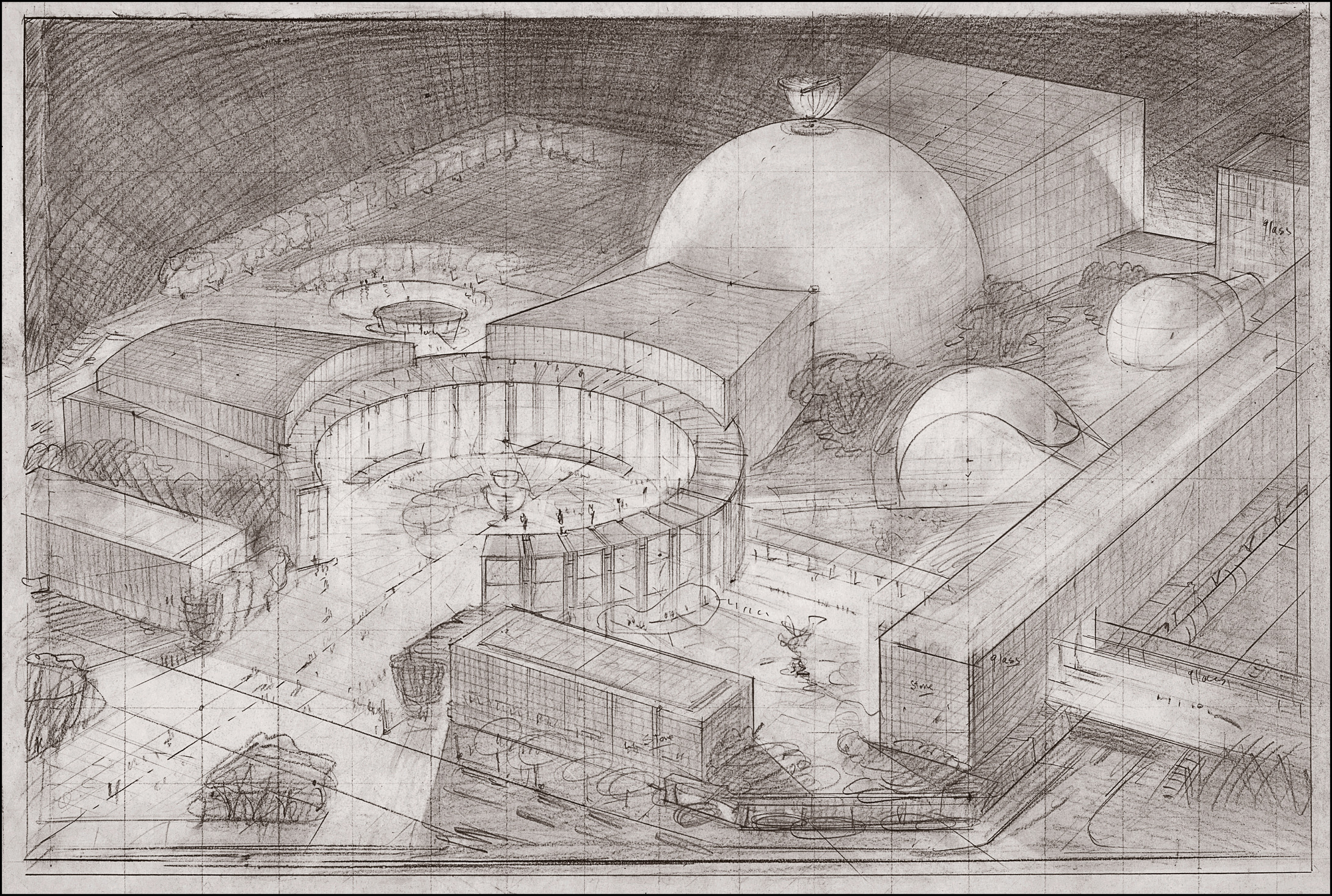

An early, rather imperial vision of Lincoln Center, as rendered by Hugh Ferriss

At the same time, planners did have to deal with “neighbor trouble,” as Jacobs called it, the holdouts who had survived Moses’s bout of slum clearance. In early drawings, Wallace Harrison dreamed up imperial compounds. One version by the magnificent renderer Hugh Ferriss shows a domed Pantheon facing onto a circular, colonnaded piazza reminiscent of St. Peter’s: ancient and papal Rome, fused on Columbus Avenue.

Harrison and his team of architects used an ancient technique to reassure the bluestockings that they wouldn’t cross paths with the wrong sort of people: An unstormable travertine barrier blocks off the temple mount from the housing project to its west. As a space devoted to the classical performing arts, Lincoln Center was clearly an institution that would have to exist in constant dialogue with the past as well as nourish the future. So the architects threw out the modernist tradition of throwing out the history books and turned instead to a range of models. They considered the Paris Opera, with its broad avenue of approach; Piazza San Marco in Venice, a startlingly vast clearing reached from a skein of narrow alleyways; and the sixteenth-century Piazza del Campidoglio in Rome.

You can read the tug-of-war between openness and aloof monumentality in the architecture. Johnson made his State Theater (now the David H. Koch Theater) practically sarcophagal, turning it inward, focusing attention on the ample promenade and the auditorium’s gilded ceiling and fronting the avenue with a featureless slab. Abramovitz conceived of Philharmonic Hall (later Avery Fisher, now David Geffen Hall) as a luminous box inside a cage of slender columns. For the Met, Harrison was forced to tamp down his desire for an exotic arrangement of barrel vaults and sweeping forms and instead produced a simpler structure with a spare arcade and a cramped lobby. The years have cloaked Lincoln Center’s disparate parts in the illusion of harmony, but beneath the patina is an enforced collision of aesthetics, glued together by budget cuts and compromise.

With its white stone façades and noble arcades, Lincoln Center looks as though it’s always been there and always will be, a 1960s acropolis that glows afresh each night, constantly rejuvenated by daily infusions of the performing arts. But in 2002 the campus looked older, sadder, and lonelier. The travertine was streaked, the pavers pocked, and the air conditioners creaky. On rainy nights, audiences exiting the halls picked their way around lagoons that leaked into the garage below the plaza. West Sixty-fifth Street might have been the back end of a big-box store. In the old days, attending a concert in Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center required a certain determination. The sign was easy to miss, but you could recognize the place by the clutch of smokers perched on the planters out front—nobody else would linger in such a hostile, amorphous plaza. To enter, you slunk beneath a forbidding slab, inched past a tiny box-office anteroom, and descended a short flight of stairs into a long and loveless lobby, where daylight trickled in through grudging slits. Another level down, in the buried auditorium, noise from an ancient ventilation system masked the sound of passing subway trains—and deadened the music. The procession suggested a highbrow speakeasy, as if there were something furtive about all that chamber music going on inside.

Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center, post-renovation

The Lincoln Center we see today is the result of a $1.2 billion renovation. The task of rejuvenating the aging complex went to Diller Scofidio + Renfro, a firm that is now among the most prestigious in the world but at that time had yet to complete an actual building. They got the job because they weren’t itching to tear the whole thing down and start from scratch. Instead, they treated the buildings with clarity, tenderness, and, when it was needed, unsentimental rigor. Tully Hall now announces its presence with a sharp prow that steers toward Broadway, riding a spray of light. West Sixty-fifth Street has become a festive thoroughfare, lined with marquees, theater lobbies, and a series of freestanding video screens parading down the newly generous sidewalk. The oppressive viaduct over the street has vanished, replaced by a graceful, twisting glass-and-steel footbridge. And on the main plaza, the dancing jets of water in the sleek round fountain were choreographed by WET Design, which built the aquatic spectacular at the Bellagio in Las Vegas.

The change is embodied, for me, by the new staircase that rises gently from Columbus Avenue. The old drop-off lane, a treacherous river of traffic that cut between stairs and plaza, vanished, to reopen safely underground. The subtle alteration shows the care with which the architects stitched the campus to the city and at the same time preserved its separateness. Now, once I cross the threshold, I find myself slowing down rather than rushing to my seat. The rhythm of the stairs imposes a stateliness of pace. You can’t easily bound up them on the way to the box office or thunder down to grab a cab. The staircase acts as an anteroom, separating the fantastical realm of the stage from the reality lurking at the curb. When Lincoln Center opened, critics accused it of dowdy design, backward-looking values, and diluted modernism. Ah, but it was so much older then; it’s younger than that now.

This area encapsulates how impossible it is to evaluate whether the transformation of a neighborhood is good or bad. To the thousands whose homes in San Juan Hill were razed, whose neighbors were dispersed and lifetime habits undone, the construction of Lincoln Center was a calamity. To all those who trained there for a life in music, opera, theater, and dance, or the millions who had transcendent artistic experiences there, it’s been a boon. Like the areas around it, Lincoln Center draws people from all over the world who organize their lives around their love of the performing arts. Born of rupture, idealism, and injustice, Lincoln Center has gradually fused with the nervous system of the Upper West Side, permeating its spirit and imagination.