THE BASIS FOR A CONSISTENT CLASSIFICATION of living organisms began in the mid-eighteenth century with Carolus Linnaeus’s (Karl von Linné) monumental work Systema naturae. In the tenth edition of that work in 1785, he proposed that the group Canis include three genera—Canis, Vulpes, and Hyaena—based on similarities in form and function (such as wolflike and foxlike predations). The hyenas were later placed in their own family, Hyaenidae, within the order Carnivora, and the family Canidae, also within that order, was to hold Canis, represented by the wolf (C. lupus), the fox (Vulpes vulpes), and a number of other species formalized during the nineteenth century (Mivart 1890). In this book, we use the term dog informally to denote members of the family Canidae rather than just the domestic dog (Canis familiaris or Canis lupus familiaris).

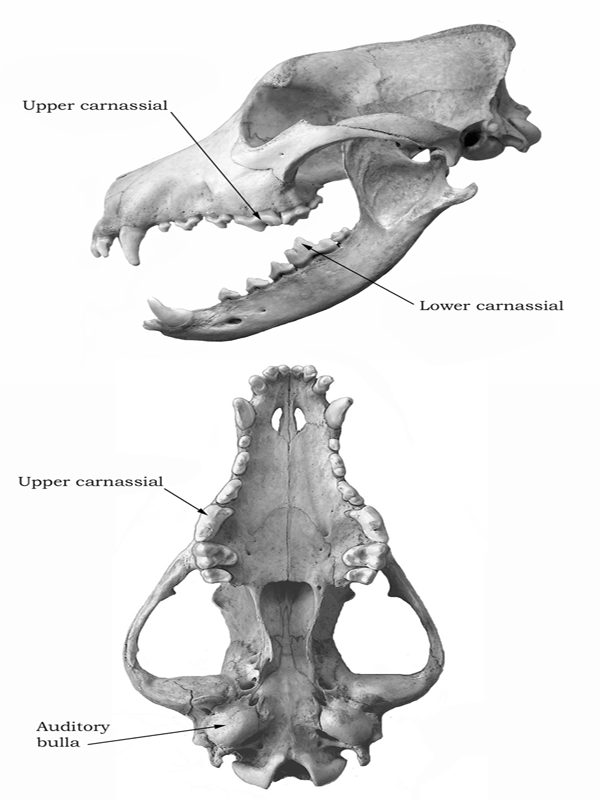

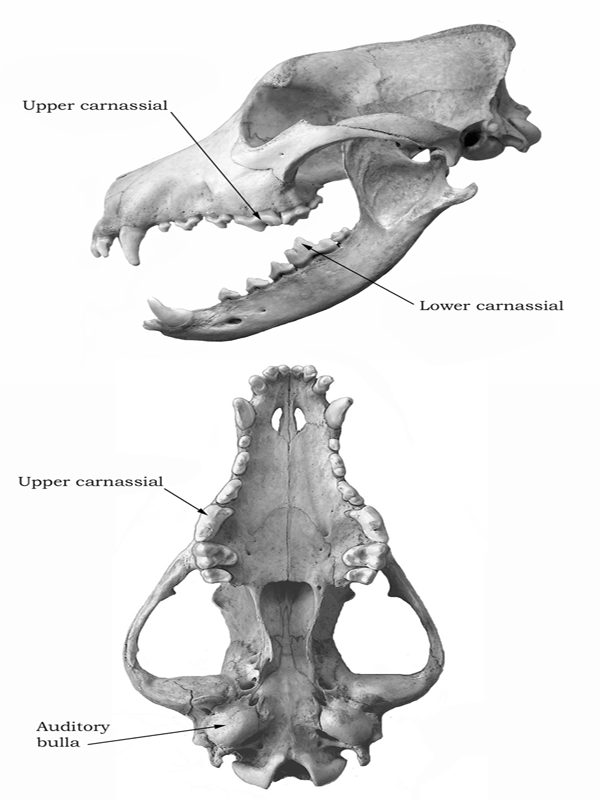

It was recognized early on that all members of the order Carnivora (collectively called carnivorans) possess a common arrangement of teeth, in which the last upper premolar and lower first molar have bladelike enamel crowns that function together as shears (figure 1.1). This dental arrangement was a fundamental adaptation to cutting meat, and all carnivorans are characterized by the possession of these teeth, which are called carnassials (chapter 4). Through the long history of the Carnivora (more than 60 million years), this dentition has been modified for many adaptations—some focused exclusively on a diet of meat (hypercarnivory [chapter 4]), some on the crushing of vegetation (hypocarnivory), and some on generalized (“primitive”) functions (mesocarnivory) or the loss of the carnassial function altogether, as in the termite-eating hyaenid Proteles, fish-catching seals and sea lions, and mollusk-crushing walruses. This diversity of dental adaptations provides many ways to characterize species and some species groups (genera or families), but the form of the carnassials themselves limits the number of ways that they can function. In the past, the chance of similar adaptations unrelated to genealogy was great and could confuse a classification intended to give evidence of evolutionary relationships. This was not a problem for Linnaeus or the eighteenth-century biologists, but it did become a concern for Charles Darwin and other nineteenth-century evolutionary biologists who followed him.

FIGURE 1.1

Skull and mandible of a domestic dog

Top, lateral view; bottom, ventral view.

The British anatomist William Henry Flower (1869) noticed that the form and composition of the bony structures that surround the middle ear of the carnivoran skull provide another means of subdividing the Carnivora into three groups based on features other than the teeth. These structures include the size, form, and composition of the bony covering at the base of the skull that encloses the middle-ear space in which lay the tiny auditory ossicles (bones) essential to hearing (see figure 1.1). This bony structure, called the auditory bulla, is formed of two major sites of ossification. The ectotympanic bone contains the external opening of the middle-ear space and incorporates the bony tympanic ring that holds the tympanic membrane (“eardrum”), into which the malleus, the outermost part of the ossicular chain, is inserted. The entotympanic bone forms the inner and most inflated part of the bulla, often enclosing part of the internal carotid artery. These two parts of the bulla are fused together, the junction often prolonged internally to form a septum dividing the middle-ear cavity into two chambers. Flower found that the living carnivoran families form three large groups according to the shape and construction of the bulla. The catlike carnivores (Aeluroidea) have an inflated bulla with a large septum that nearly subdivides the middle-ear space (see figure 4.10). This septum is derived in nearly equal contributions from the ectotympanic bone and the entotympanic bone, but the entotympanic encloses the internal carotid artery. The bearlike carnivores (Arctoidea), in contrast, have a little inflated bulla that lacks a septum, but the internal carotid artery is enclosed by the entotympanic bone. The doglike carnivores (exclusively Canidae and Cynoidea) have an inflated bulla and a low, unilaminar septum composed largely of the entotympanic bone, but the internal carotid is enclosed for only a short distance anteriorly in the latter bone. Once identified, these bony features and the distinctions among them in different carnivoran families became of great value to paleontologists in their attempts to group carnassial-bearing fossils into evolutionary units.

With Charles Darwin’s introduction in 1859 of natural selection as the mechanism of evolution, evolution became more widely accepted. The fossil record of animals and plants had also been accepted as evidence that a history of life was contained in the geological record. This acceptance enabled evolutionary reconstructions to be carried into the geological past. Early evolutionists were unaware of the genetic bases for evolution until Gregor Mendel’s work was discovered in the early twentieth century, but discovery of the means of genetic change had to wait until later in that century.

Most twentieth-century biologists and paleontologists continued to describe the form, or morphology, of canids in order to use resemblance as a tool to establish biological relationships consistent with evolution. Because species are the smallest units usually dealt with, the nature of these units needed definition. At midcentury, with the acceptance of genetic and morphological bases for definition, a species was regarded either as a biological species (a group of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations that are reproductively isolated from other such groups [Mayr 1940]) or as a morphological species (a group of individuals or populations with the same or similar morphological characters). The range of morphological variation among the individuals recognized as a species would approximate those characters observed in related living species. The morphological definition is the only practical approach when considering the fossil record and living species where interbreeding in nature has not been observed.

The determination and definition of canid species are thus fundamental to our quest for the history of the family Canidae, or its phylogeny. We have used the principles of phylogenetic systematics in determining evolutionary relationships among species because we believe this approach leads to conclusions that can be tested by the hypothetical-deductive methods most consistent with modern science. Hypotheses about the evolutionary relationships between species are demonstrated by the common possession of specific features unique to these species and derived from a single source common to both (homology). This evidence indicates a monophyletic relationship between the species if the ancestor in common is not found in common with any other species. Such statements are dependent on the quantity of the evidence and are intrinsically better tested among living species than among fossil species, where the evidence is restricted not only to the skeleton, but also to its state of preservation.

This kind of phyletic analysis is often termed cladistic because it reconstructs clades, or monophyletic branches, into a “cladogram,” or diagram, of mutual relationships based on a specific set of morphological features. Inadequate evidence may lead to several alternative fits of the data underpinning the cladogram. In these cases, the principle of parsimony guides the first choice among fits: the simplest explanation of the cladogram is most likely the best.

In this book, we discuss the evolution of the Canidae. We include some features that are not demonstrably cladistic, but that seem compatible with more general biological relationships, in particular those that suggest direct or anagenetic processes in evolution rather than bifurcating, cladogenetic ones. We also place the phylogenies in time so that the tempo of biological change is shown and thus the history of the canid family can be depicted (appendix 2).

FIGURE 1.2

Time scale of the Cenozoic era

The time scale for the history of canids, most conveniently expressed in units of millions of years ago (figure 1.2), has been developed from more than 200 years of study, first only of the rock record (stratigraphy) in which the natural superposition of strata (younger over older) provides evidence of the relative ages of the contained fossil samples, but later from correlation using a variety of tools such as specific paleontological similarity and radioactive elemental isotopes that give direct ages of rocks based on known rates of elemental decay.