AS MEMBERS OF THE ORDER CARNIVORA, the majority of canids are predators. Thus throughout their evolutionary history, canids have been closely intertwined with their prey, which in turn have been directly affected by the surrounding plant communities.

During the past 20 years, a global picture of the long-term paleoclimatic record has emerged. Through studies of air trapped in ice cores in polar regions, of drill cores from oceans and lakes, and of wind-blown sediments, we can learn much about the climatic histories of various regions. In particular, microorganisms such as the single-celled foraminifera preserved in marine sediments permit us to obtain a fairly detailed picture of ocean temperatures in the past, which serve as an approximate indicator of global environments (figure 6.1). From such studies, we know that throughout the Cenozoic (most of the past 65 million years), numerous fluctuations in temperature have profoundly affected these environments. The abbreviated narrative in this chapter attempts to give readers a sense of overall climatic changes during the Cenozoic and its effect on the associated biological communities. Against this background, we can begin to appreciate the dramatic changes in physical environments and the associated biological responses. Because canids were confined largely to North America during much of their early existence, we need concern ourselves with only their immediate environments in North America in this era.

The Paleocene and the Beginning of Carnivora

The Cenozoic era immediately followed the extinction of the dinosaurs at the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary (65 Ma) in a global catastrophe apparently caused by the impact of an asteroid. After the dust settled, the beginning of the Cenozoic is marked by a rather warm period in the Paleocene (65 to 55 Ma). During this epoch, mammals finally became the dominant land vertebrates, taking over many of the niches previously occupied by the dinosaurs. An explosive radiation of early mammals rapidly filled the ecological space left open by the dinosaurs’ demise. Many of the Paleocene mammals increased in body size, as contrasted with their largely mouse- and rat-size ancestors in the Mesozoic (248 to 65 Ma), and some of them included the earliest members of lineages leading to modern forms, including the order Carnivora, which saw its first members in the early Paleocene in the form of the family Viverravidae (some interpretations of the fossil record suggest that carnivorans were present in the late Cretaceous [75 Ma] of North America; see “Cimolestids” [chapter 2]). However, the archaic viverravids featured a precociously reduced set of teeth and were probably not closely related to canids. During the late Paleocene (56 Ma), the ancestral group that gave rise to canids, the family Miacidae, also began to appear.

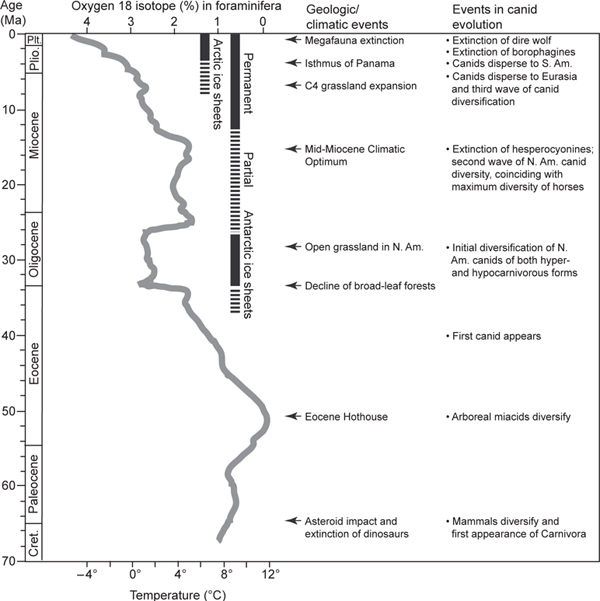

FIGURE 6.1

Events in the evolution of canids

Major events in canid evolution and corresponding geologic and biotic events, as associated with a global temperature curve (scale on bottom) during the past 65 million years throughout the Cenozoic (vertical axis). This paleotemperature curve (simplified from Zachos et al. [2001]) is compiled from oxygen isotopes (scale on top) preserved in bottom-dwelling, deep-sea foraminifera contained in sediments from multiple drill cores in various oceans. A clear trend of climatic deterioration from a global greenhouse to icehouse during the Cenozoic is readily apparent, and many of the more drastic temperature disturbances were triggered by major geological events. In an increasingly open landscape, canids thrived by becoming increasingly cursorial.

The Eocene Hothouse and the Origin of Canids

From the already warm and humid conditions in the Paleocene, the beginning of the Eocene (around 55 Ma) was marked by a rapid warming to a peak temperature more than 14°C higher than today’s average global temperature. This extreme warming event is called the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum or, more colloquially, the Eocene Hothouse. With these warm conditions, the Eocene global climate was perhaps the most homogeneous within the Cenozoic as a whole. The temperature gradient—the differences between temperatures along the equator and temperatures at either pole—was only about half as much as it is today, resulting in a very equable climate with low seasonality. The climate was so warm that even the polar regions could support a diverse and productive biota, including the miacids.

The warm and humid conditions during the Eocene—coupled with a high level of the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4)—were ideally suited to the growth of dense forests in much of the world. During the Eocene Hot-house, tropical forest conditions expanded to the latitude of northern Wyoming, as recorded in the fossil plants from the Bighorn basin. Lush forest canopies dominated much of North America. It is perhaps no coincidence that primates, along with other forest-dwelling mammals, flourished under such conditions. Carnivores in the Eocene were similarly adapted to life in and around trees. A modestly diverse group of miacids began to explore various environments for opportunities, although they were mostly the size of small foxes or smaller and lived in the shadow of the hyaenodonts, a group of archaic predators that were not closely related to carnivorans and that were generally larger (coyote to wolf size) than the miacids and better equipped to prey on larger herbivores (chapter 2).

Through a series of small, foxlike miacids, the proto-canids gradually emerged. In the late Eocene (40 Ma), the first unambiguous canid, Prohesperocyon, appeared in southwestern Texas, represented by a single skull and lower jaw. Prohesperocyon probably did not differ substantially from other ancestral miacids in its way of life in the forest, but it bore the unmistakable marks of being a true canid: an inflated bony bulla covering the ear region and subtle dental features, such as the loss of the upper third molars. Prohesperocyon’s immediate descendant, Hesperocyon, appeared very soon thereafter in the northern Great Plains and Canada (figure 6.2). Fossil records of Hesperocyon are far more abundant than those of its Prohesperocyon predecessors. The profusion of fossil records of this early canid indicates its central role in the phylogeny of all canids. At this stage of canid evolution, it is difficult to point to a particular skeletal feature that may have given canids an overwhelming advantage, but a slightly more elongated limb with compressed digits seems to hint at their preadaptations to an increasingly open environment. However, their limbs were not fully digitigrade, and they were probably more suited for lives on the forest margin, where the ability to climb trees helped them escape formidable predators (figure 6.3). Nonetheless, the evolution of cursorial feet may have been a key adaptation that enabled canids to succeed in later, more open environments.

The Oligocene Cooling and the Initial Diversification of Canids

From the peak of the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum more than 50 Ma, the first major step toward a long trend of climatic deterioration during the Cenozoic occurred near the Eocene–Oligocene boundary (around 33.7 Ma), apparently associated with the initial appearance of ice sheets on the Antarctic continent. James P. Kennett (1977) proposed that plate tectonics was the ultimate cause of the formation of the Antarctic ice cap. He suggested that the formation of Antarctic circumpolar currents in the Southern Ocean thermally isolated the Antarctic continent from the world ocean. These circumpolar currents were initiated because of the initial tectonic opening of a plate boundary between Antarctica and Australia (Tasmanian Passage) and the later extension of this spreading center between Antarctica and South America (Drake Passage). However, computer modeling of the climatic processes seems to indicate that a drop in atmospheric CO2 may also be to blame for the formation of Antarctic ice (DeConto and Pollard 2003). Whatever the cause of the Antarctic ice sheet, global temperatures dropped by 4 to 5°C or even more within a short span of 1 to 2 million years. Such a significant temperature change caused a major faunal turnover among marine organisms, but the land animals were less affected (Berggren and Prothero 1992).

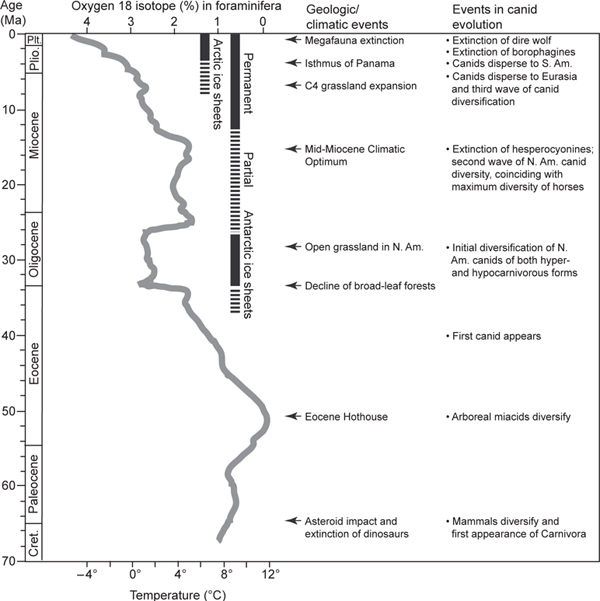

FIGURE 6.2

Comparison of size among mammals from the late Eocene (Chadronian)

From left to right: Hesperocyon gregarius, Palaeolagus, Mesohippus, and Leptomeryx. Few ungulate species attained large size during the Chadronian of the late Eocene (35 Ma), but not even the small species depicted here would be suitable prey for Hesperocyon, and only the early lagomorph Palaeolagus, along with rodents and other smaller vertebrates, would feature regularly in this early dog’s menu.

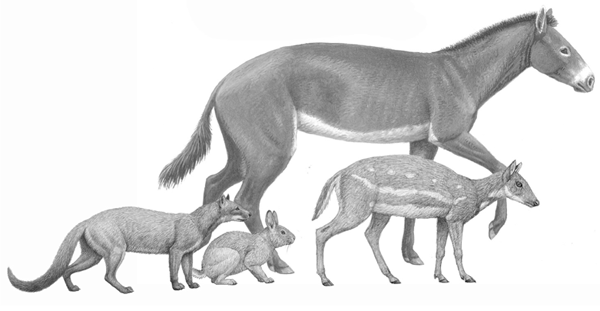

FIGURE 6.3

A scene in western North America during the late Eocene (Chadronian)

The ability to climb onto thin branches would have helped the early canid Hesperocyon (right foreground), from 35 Ma, to escape from potentially dangerous, much larger animals, such as the saber-toothed nimravid Hoplophoneus primeavus (left) or the entelodontid Archaeotherium mortoni.

After the tropical forest conditions in the early Eocene, a steady decline in global temperatures throughout the Eocene gradually turned the plant communities into something close to warm-temperate forests. The sharp drop in temperatures at the Eocene–Oligocene boundary due to the isolation of Antarctica was associated with a shift from warm-temperate, angiosperm-dominated forest types to cooler-temperate, gymnosperm-dominated (mainly coniferous) forest types in high latitudes. In midlatitude North America, the climatic deterioration initiated a process of progressively drier conditions and more seasonal environments. Plant communities at midlatitudes responded to this trend of decreasing rainfall by changing from high-productivity, moist forests in the late Eocene to low-biomass, dry woodlands at the beginning of the Oligocene (34 Ma), progressing to wooded grasslands and ultimately to large areas of open grassland in the middle Oligocene (30 Ma) (Leopold, Liu, and Clay-Poole 1992).

The initial opening up of the continental interiors by the retreat of the woodlands and the development of a woodland-savanna-grassland mosaic landscape were the impetus for the evolution of the grassland vertebrate communities (figure 6.4; see figure 6.1). Mammalian herbivores began to develop high-crowned teeth and increased cursoriality. To a large extent, the history of canids is a story of the coevolution of a group of cursorial carnivorans with the emerging grassland communities. Carrying over from the late Eocene, Hesperocyon remained the only canid with a consistent fossil record during the early Oligocene. However, we also possess a few tantalizing fossils indicating that Hesperocyon had begun to diversify in the early Oligocene, seizing the opportunities afforded by the opening up of the landscape. This initial radiation of Canidae produced ancestral members of all three subfamilies of canids (Hesperocyoninae, Borophaginae, and Caninae). All these early progenitors were fox-size small canids, but each bore the morphological hints of later events. They suddenly appeared in the badlands of Nebraska, Colorado, South Dakota, and Wyoming during the Orellan age (34 Ma) at the beginning of the Oligocene. For the subfamily Hesperocyoninae, members of the Mesocyon–Enhydrocyon group and of the Osbornodon group emerged, and for the subfamily Borophaginae, the earliest member, Otarocyon, is recorded in the Orellan. For the subfamily Caninae, a single jaw fragment indicates its presence as a progenitor of Leptocyon.

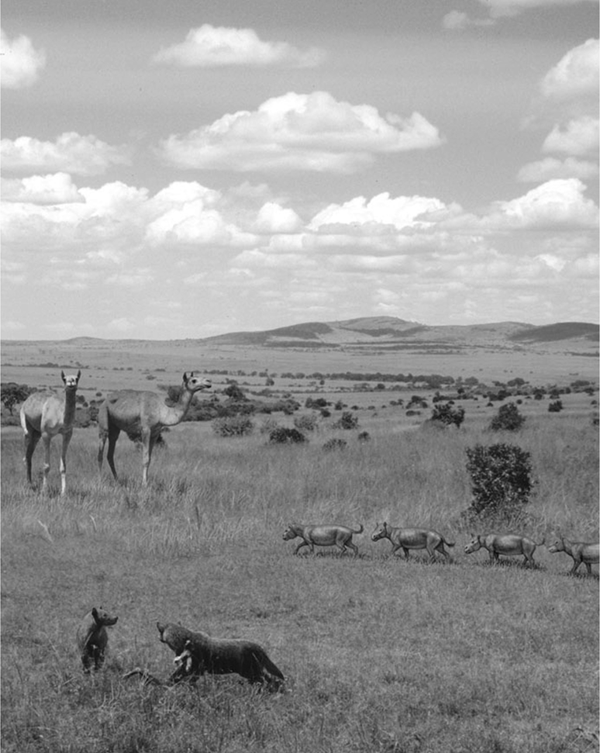

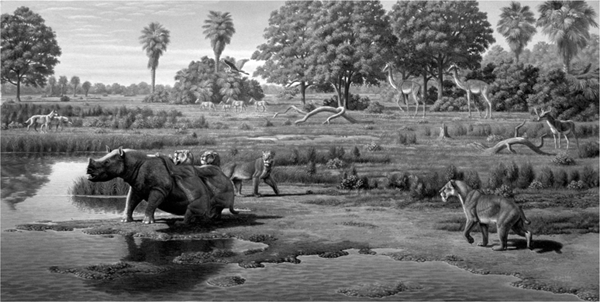

FIGURE 6.4

A scene in western North America during the late Oligocene (Arikareean)

Left background, the large camelid Oxydactylus wyomingensis; left foreground, the canid Enhydrocyon crassidens; right center, the oreodontid Leptauchenia decora, from 27 Ma.

The rest of the Oligocene saw the continued diversification of canids and the first dominant dogs in the Hesperocyoninae’s history, such as Sunkahetanka, Philotrox, Enhydrocyon, and Paraenhydrocyon. These hesperocyonines evolved highly hypercarnivorous dentitions that are comparable to the dentition of the modern African hunting dog, and they achieved the body size of small wolves to begin hunting prey larger than themselves. In contrast, facing competition from the dominant hesperocyonines, the early borophagines tended to evolve toward hypocarnivorous dentitions and small body sizes to exploit less predaceous lifestyles. These borophagines were represented by Archaeocyon, Cynarctoides, Phlaocyon, and others (figure 6.5). Meanwhile, the canines were still biding their time with a few inconspicuous species of Leptocyon throughout the Oligocene and early Miocene. By the middle to late Oligocene (around 30 to 28 Ma), the combined diversity of canids had reached its peak of about 25 species in western North America (figure 6.6). Such a high taxonomic diversity within a single family of carnivorans on a continent was unprecedented before this time and has not been seen since, and it demonstrates the impact of early canids in the carnivoran communities of North America. This peak diversity was also the first by a carnivoran family in a time otherwise dominated by archaic predators, such as hyaenodonts, in most parts of the world. It signaled that the time for carnivorans had arrived. Indeed, hyaenodonts and other archaic predators had begun to decline, and their roles were eventually taken over by members of the Carnivora.

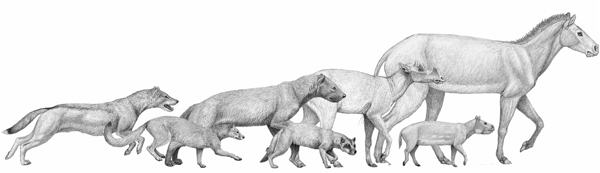

FIGURE 6.5

Comparison of size among mammals from the late Oligocene (Arikareean)

From left to right: the canids Mesocyon coryphaeus, Archaeocyon leptodus, Enhydrocyon crassidens, and Phlaocyon leucosteus; the protoceratid Protoceras skinneri; the oreodont Leptauchenia decora; and the equid Miohippus gidleyi. Horses such as Miohippus were among the largest potential prey for dogs in the Oligocene (27 Ma), and catching them would normally have required group action. Smaller ungulates such as the protoceratids and the abundant Leptauchenia could have been taken even by lone individuals of the largest dog species. Ungulate prey was essentially out of range for the smaller dog species, which would have taken rodents and other small mammals, as well as, in the case of Phlaocyon, a large proportion of nonvertebrate food. Reconstructed shoulder height of Miohippus: 70 cm.

The Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum and the Second Diversification of Canids

After the initial shock of plummeting global temperatures in the early Oligocene, temperatures began to rebound modestly, but were largely stable through much of the Oligocene and into the middle Miocene (about 30 to 15 Ma). World climates during this time were still rather mild in modern terms. This stable period, with a gradual warming trend, peaked at the so-called Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum. Although Antarctic ice first had formed at the beginning of the Oligocene (34 Ma), the ice caps during that epoch were small, located mostly on the high Antarctic plateau, and highly dynamic (fluctuating with time). By the end of the middle Miocene (14 Ma), another drastic drop in temperature occurred, this time with the formation of a permanent Antarctic ice sheet. This fall in temperature precipitated a massive response from plant communities.

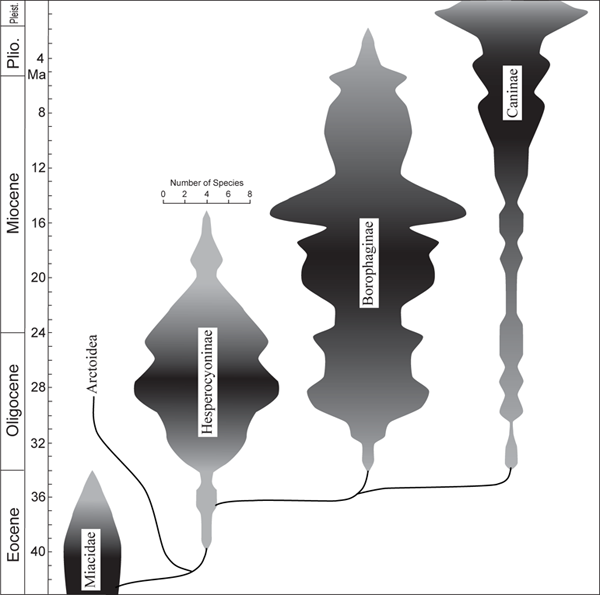

FIGURE 6.6

Diversity of species through time in the three subfamilies of Canidae

The width of each subfamily at a particular time slice in the figure corresponds to the number of species within the subfamily (shown in the scale above the Hesperocyoninae). Although both the Hesperocyoninae and the Borophaginae had a substantial diversity during the Oligocene, members of these subfamilies occupied different niches. The early borophagines were predominantly hypocarnivores, which complemented the hesperocyonines’ hypercarnivory. By the time the Hesperocyoninae underwent its drastic decline in the early Miocene, the borophagines began to occupy the hypercarnivorous niches left open by the disappearing hesperocyonines. A similar complementary relationship also existed later between the borophagines and canines.

Direct records of the plant communities in the Miocene are relatively rare. Existing evidence, however, indicates the presence of a certain amount of open grassland, perhaps alongside forests, in the midlatitudes of North America during the early Miocene. During these dramatic climatic changes, mammalian herbivore communities in the continental interiors underwent a similarly drastic turnover. In part because of evolution and in part, for the first time, because of immigration by Eurasian natives, herbivore diversity steadily increased through the early to middle Miocene until reaching an all-time peak in the Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum (around 15 Ma). This peak is revealed in the extraordinary fossil record of North American horses, a celebrated example of evolutionary adaptation for open vegetation communities. As many as 16 genera (probably including many more species) of horses were present in the middle Miocene, a peak diversity that has steadily declined ever since (figure 6.7). Although lacking a correspondingly rich fossil record of plants, we can reasonably deduce that a high diversity in mammalian herbivores probably corresponded to a high diversity in the plant community as well.

Perhaps not coincidentally, canids experienced their second spurt of diversification in the middle Miocene, although it involved mostly borophagines. (Hesperocyonines were on their way to becoming extinct, and canines were still relatively inconspicuous.) This peak had a somewhat lower taxonomic diversity (20 species) than that of the late Oligocene (25 species), but canids nevertheless experienced their maximum ecological breadth during this time. Canids had by this time acquired more complete hypercarnivorous or hypocarnivorous morphologies, corresponding to a wide range of diets from pure meat to a mix of foods, including a large component of fruits and vegetable matter. In an indirect way, such a high ecological diversity by a family of carnivorans was also a reflection of variable plant communities and perhaps also of competition (or lack thereof) from other groups of carnivorans in North America.

By the late Miocene (8 to 7 Ma), apparently in response to the presence of the permanent Antarctic ice sheet, open grasslands became dominant in midlatitude western North America. Furthermore, near the end of the Miocene, there was a worldwide turnover of the plant communities in the midlatitudes: from C3-photosynthesizing plants adapted to a high level of atmospheric CO2 to C4-photosynthesizing plants adapted to a reduced level of atmospheric CO2. C3 plants have a three-carbon photosynthetic pathway and include trees, shrubs, forbs, and cool-season grasses. In contrast, C4 plants have a four-carbon photosynthetic pathway and include mostly grasses that are better adapted to hot, high-light, and water-stressed environments. C4 plants seem to have a competitive advantage over C3 plants in lower levels of CO2. The transition from C3 to C4 plants in the late Miocene was thus another major indication of further climatic deterioration.

In addition to changes in the photosynthetic pathways of plant communities in a lower level of atmospheric CO2, numerous mammalian herbivores had independently evolved high-crowned cheek teeth by the late Miocene. The height of the crown in herbivores’ teeth is defined by the total height of the enamel, including parts that are buried deep in the jaws but that will eventually emerge from the jaws when the crown surface is ground down by use. The high-crowned (also known as hypsodont) cheek tooth is defined by a crown height greater than its occlusal length, and it is an ecologically important indicator of diets because it can sustain much more wear associated with the eating of fibrous and abrasive vegetation such as dry grasses. Grasses generally grow in open and seasonally dry environments. Mammals with low-crowned teeth generally eat tender tree leaves and low shrubs and are commonly referred to as browsers. By contrast, mammals with high-crowned teeth can handle tougher and drier grasses that are closer to the ground and thus contain more grit that helps wear the teeth faster. These grass eaters are referred to as grazers. Late Miocene grazers faced the prospect of eating low-quality vegetation (dry grasses) in greater quantity to compensate for its low nutrition. The high content of grit (wind-blown sands attached to grasses) and the presence of phytoliths (microscopic particles of silica contained in leaf epidermis as a self-defense mechanism) in many grasses caused additional tooth wear. The combination of these factors was a powerful inducement in the evolution of hypsodont teeth.

FIGURE 6.7

Comparison of size among mammals from the Miocene (Barstovian) of North America

From left to right: the borophagine dog Aelurodon ferox, the small ruminant Blastomeyx gemmifer, the hipparionine horse Neohipparion coloradense, the ruminant Cranioceras skinneri, and the small hipparionine Pseudhipparion retrusum, from around 12 Ma. Reconstructed shoulder height of Neohipparion: 110 cm.

As the landscapes opened up, it became increasingly critical for the grazing herbivores to be more cursorial (figure 6.8). A cursorial grazer can better escape from predators and has the added advantage of covering larger grazing range in order to avail itself of optimal pastures. Again, the classic story of the evolution of horses serves as a perfect example. One of the most common ways to develop the ability to run faster and walk for longer distances in a more open landscape is for the limbs to be elongated and lightened, particularly the more distal limb segments (those toward the hands and feet rather than those in the upper arms and thighs). This process is perfectly illustrated in horses by the elongation of their finger and toe bones and the loss of their lateral digits until they eventually stood on a single finger/toe in an ultimate unguligrade posture, as seen in modern horses (Miocene horses did not reach this stage and commonly had three toes).

Against the background of rapid evolutionary change among mammalian herbivores during the late Miocene, canids had to adjust to keep up with their prey. Although carnivorans probably did not care much what their prey ate, they did have to adapt to the increasingly cursorial nature of the herbivore communities. The result is the ever-present saga of the coevolution of predator and prey. It is particularly pronounced among large, pursuit predators such as Aelurodon, Epicyon, and related forms of borophagines (figure 6.9). The late Miocene canid evolution also marked a decline in diversity and ecological breadth in the borophagines. Competition from new immigrants—such as felids, false saber-toothed cats, large mustelids, and giant ursids—intensified, leading to adaptations for bone cracking among borophagines such as Epicyon and early Borophagus. Bone cracking as a scavenging strategy was also facilitated by a more open environment, which permitted greater visibility of carcasses and thus more efficient use of leftover skeletons.

FIGURE 6.8

A scene in Florida during the late Miocene (Clarendonian)

From left to right: the canid Epicyon haydeni, the rhinocerotid Teleoceras fossiger, the barbourofelid Barbourofelis loveorum, the three-toed horse Neohipparion leptode, the camelid Aepycamelus major, and the protoceratid Synthetoceras tricornatus, from around 9 Ma.

The expansion of open grassland in North America in the late Miocene seems also to have set the scene for an early diversification and dispersal of the canines. For much of the time since the origin of the subfamily Caninae at the beginning of the Oligocene (about 33 Ma), the subfamily line of descent was sustained mainly by a few species of Leptocyon that were no match for the contemporaneous and more formidable hesperocyonines and borophagines. One feature of Leptocyon that distinguished it from the canids of the other two subfamilies was a slender and elongated limb, which, with the loss of a functional thumb and big toe, became a critical advantage when the landscape opened up. By the late Miocene, the early precursors of modern foxes (tribe Vulpini) and an ancestral genus of modern canines (tribe Canini), Eucyon, had emerged. In addition, other canids were no longer competing for the foxlike niches for the first time in their long but inconspicuous early history—borophagines had become ever larger and more powerful hypercarnivores and no longer vied for a more generalist predator’s way of life.

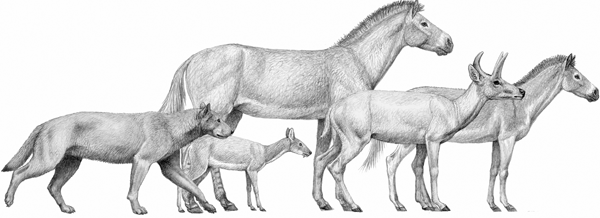

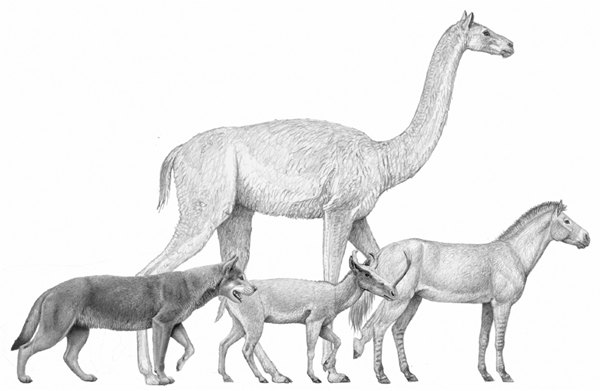

FIGURE 6.9

Comparison of size among mammals from the late Miocene (Clarendonian) of North America

From left to right: the borophagine dog Epicyon haydeni, the camelid Aepycamelus, the ruminant Synthetoceras tricornatus, and the hipparionine Neohipparion, from around 9 Ma. As shown by this comparison, Epicyon was large enough as an individual to hunt some of the medium-size ungulates, although prey the size of the Neohipparion and larger would have required group action. Total height to the head of Aepycamelus: 3 m.

The time for the subfamily Caninae had finally arrived. One of the most important events in the subfamily’s history is its breaking out of North America, the continent that had been the cradle of the family Canidae’s evolution for more than three-quarters of its existence and from which the first two of the three subfamilies (Hesperocyoninae and Borophaginae) could not escape (except for a single incidence in the middle Miocene [chapter 3]). A species of Eucyon first made it to Eurasia in the late Miocene, setting the scene for the canines’ ultimate triumph in the world (chapter 7).

The Pliocene Upheaval and the Great Canid Expansion to the World

Through much of the Pliocene (5 to 1.8 Ma), global climates steadily deteriorated with a precipitous drop in temperatures. By the late Pliocene (about 3 Ma), an arctic ice sheet had begun to develop. This time, ice growth once again coincided with another important tectonic event, the formation of the Isthmus of Panama, which blocked direct ocean circulation between the Atlantic and the Pacific, although global factors probably contributed to the arctic ice formation as well.

Continuing the trend that had started in the late Miocene (6 Ma), the expansion of C4 grasslands was the main theme for plant communities, particularly in the midlatitudes of the world, in an increasingly open landscape caused by a drier, colder, and more seasonal climate during the Pliocene. Mammalian herbivores adapted by acquiring increasingly high-crowned cheek teeth to tackle the tougher and more seasonal grasses. Their limbs also became more cursorial, continuing the earlier trend of lengthening in the distal segments of limbs and reduction in the number of toes. By the Pliocene, the Dinohippus–Equus lineage had emerged, and it achieved the ultimate reduction in the number of toes—it retained only the single middle digit, with the second and fourth digits on either side reduced to no more than small remnants of their former sizes. The single-digit horses outcompeted their three-toed horse ancestors and within a short period became the dominant horses in North America. By the late Pliocene to the early Pleistocene, Equus immigrated to Eurasia and South America, along with the camels, which, like canids, had been confined to North America during much of their existence.

Borophagines were down to one or two species of Borophagus during the Pliocene. Borophagus was a highly specialized bone-cracking dog capable of consuming bones to make efficient use of carcasses. The more open landscape probably also aided in better visibility of carcasses left over by other carnivores, but the increasingly cursorial herbivores proved more and more difficult to catch for Borophagus, whose skeleton was not adapted for great speed. Low diversity, high specialization (such as bone cracking), and giant size are often signs of terminal lineages in carnivorans. Indeed, the great borophagine subfamily became extinct by the latest Pliocene (2 Ma), when its last species, B. diversidens, disappeared from the fossil record.

The subfamily Caninae, however, thrived among the newly emerging, highly mobile herbivore communities. As noted previously, the canines started with longer and more slender limbs, characters that gave them a significant advantage when dealing with increasingly swift prey.

In a wider perspective, the Pliocene was a critical period of expansion for canids. The combination of the most mobile canids ever evolved (in the form of early vulpines and canines), easy access between continents (between North and South America, between North America and Eurasia, and later between Eurasia and Africa via western Europe), and more availability of open grassland created optimum conditions for the greatest expansion of canid distribution ever. During the early Pliocene, canids finally became established in the Old World. Early records of canids in Asia, Europe, and Africa show that they lived in these areas almost simultaneously. Their first appearances on these continents differs by at most 1 to 2 million years. In Asia, canids arrived in the Yushe basin in the early Pliocene (around 5 Ma). In Europe, the record may be slightly older, as suggested by the presence of “Canis” cipio in the latest Miocene (7 Ma) of Spain (Crusafont-Pairó 1950). In Africa, the first appearance of canids is recorded by the fossil of a small fox (Vulpes riffautae) from the Djurab Desert in northwestern Chad (7 Ma) (Bonis et al. 2007). As canids arrived on these continents, they quickly diversified in their new homes. This is the third and last peak of canid diversification, which has continued through the Pleistocene until today (chapter 7).

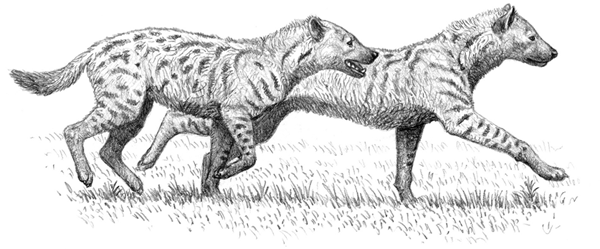

The great canid expansion also brought into contact Old World hyaenids and New World canids, two families that are probably the most comparable ecologically (chapter 5). However, by the Pliocene, the competitive landscape had changed significantly, such that members of the two families were not direct competitors. The newly arrived foxes and jackal-like canids were much smaller than most hyaenids, which by now were large, bone-cracking hypercarnivores. North American canids, those that remained in the New World, also had a limited chance to encounter a highly derived hyaenid, Chasmaporthetes, which was the only hyaenid to make it to the New World (figure 6.10). Chasmaporthetes may have competed with the last species of borophagines, Borophagus diversidens; whereas the former was better at running with a more cursorial limb, the latter was better at cracking bones. If judged by the fossil record, Borophagus seems to have outnumbered Chasmaporthetes and thus to have made a greater contribution to the carnivoran community.

FIGURE 6.10

Chasmaporthetes

The Pliocene hyaenid Chasmaporthetes. Reconstructed shoulder height: 80 cm.

By about 3 Ma in the Pliocene, the formation of the Isthmus of Panama connected the North and South American continents, which had been isolated from each other for millions of years, since the end of the Cretaceous (65 Ma). This connection resulted in the Great American Biotic Interchange, in which numerous land mammals on either continent were able to cross the land bridge and became part of the fauna on the adjacent continent. Carnivorans that immigrated to South America generally outcompeted native predators (such as borhyaenid marsupials) and quickly established themselves as the dominant components of the predatory communities.

Canids were certainly players in this success story. Starting with only a few lineages of canines in the Pliocene of Central America and southern North American, they experienced an explosive radiation once they arrived in South America. Today, the South American canids are the most diverse group of canids on any continent. The 11 species of South American canids constitute almost one-third of the entire canid diversity and are the largest group of predators in South America among various families of living Carnivora (see appendix).

The Pleistocene Ice Age and the Establishment of Modern Canids

The last epoch in the Cenozoic is the Pleistocene (1.8 to 0.01 Ma). Often called the Ice Age, this epoch is marked by extensive continental ice sheets that repeatedly advanced toward the midlatitudes. Temperatures dropped to the lowest levels ever in the Cenozoic, and during the peak glaciations continental ice sheets up to 3,000 m thick (nearly 2 miles) advanced as far south as Nebraska, Illinois, and Kansas in North America, as well as over Scandinavia and much of northern Europe, occupying about one-third of the globe. When climates shifted from warm and humid to cold and dry, and vice versa (during the interglacial periods), the plant communities underwent drastic, cyclical changes, often within short periods of time. During the glacial maxima, distributions of animal and plant communities suffered from contractions toward the equator; during the interglacial periods, they reoccupied formerly lost ground toward the higher latitudes.

To cope with the extreme coldness during glacial maxima, many large mammalian species, particularly herbivores, attained giant sizes in accordance with the general biological rule that animals in colder climates tend to increase their body sizes to help conserve body heat and to store larger quantities of fat to cope with winter weather. As a result, Pleistocene megafauna emerged in the northern continents (North America and Eurasia). Such giants as woolly mammoths, buffalo, giant deer, and woolly rhinos roamed in Eurasia; mammoths, mastodonts, giant ground sloths, large saber-toothed cats, and dire wolves reigned supreme in North America. Most members of these megafauna, especially those from North America, became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene. Interestingly, the gray wolf (Canis lupus) was one of the few exceptions and is still one of the most successful large canids in the world. If one counts the domestic dog as a highly specialized adaptation for cohabiting with humans, as some people have claimed, then Canis has achieved its ultimate success in occupying nearly every corner of the world.

Canids had lived in the harshest climates since the beginning of the Cenozoic, and Pleistocene canids were probably little affected by climatic conditions, judging from the existence of modern arctic wolves and foxes, which, along with polar bears, are the hardiest carnivorans in the Arctic. In fact, much of the gray wolf evolution apparently played out in high-latitude or even circum-Arctic regions. Given the worldwide distribution of canids during the Pleistocene and the diverse environments in which they lived, it is difficult to detect general patterns of canid evolution associated with changes in environment or in herbivore communities, as happened more obviously in the late Miocene. In general, large canines, such as the genus Canis and related genera such as Cuon and Lycaon, tended to become larger and more hypercarnivorous, a trend possibly accelerated by periodic glaciations, but perhaps also simply by their own tendency to become larger as their body size passed a certain threshold, as also happened to the earlier hesperocyonines and borophagines, which did not experience glaciations (chapter 5).

In Europe, the beginning of the Pleistocene was marked by the so-called Wolf Event, the appearance of wolflike Canis near the Pliocene–Pleistocene boundary (1.8 Ma). Since then, Canis has had a continuous presence in Eurasia, along with various species of foxes and raccoon dogs. Early humans, both Homo erectus and H. sapiens, must have had close encounters with canids because the hunter-gatherer lifestyle is broadly similar to the canid lifestyle. Ice Age humans thus may have competed with some larger species of canids. By the latest Pleistocene, this close encounter resulted in the domestication of the first canid in the Middle East or Europe or possibly China (chapter 8).

In North and South America, canids played an important role as top predators in the megafauna. The best-known example is the dire wolf (Canis dirus), which by this time had reached 68 kg in body weight, not exceeded by any other canine before or since (the only canids larger than the dire wolves were advanced species of Aelurodon and Epicyon). Fossil records of the dire wolf are widespread in much of the United States and Mexico south of the last glacial ice cap. Dire wolves also ranged into Andean South America. In the southern California locality of Rancho la Brea, they, along with the saber-toothed cat (Smilodon), occurred in high numbers relative to other carnivorans. Blaire Van Valkenburgh and Fritz Hertel’s (1993) study of canine tooth breakage on the La Brea dire wolves suggests that by the late Pleistocene, dire wolves used carcasses more systematically than is seen in modern wolves, and they were probably in intense competition with other large predators, such as saber-toothed cats and lions, for limited resources. Along with the megafauna, dire wolves became extinct by the end of the Pleistocene.

FIGURE 6.11

Cynotherium sardous

Life reconstruction of Cynotherium sardous, an extinct canid from the late Pleistocene (around 15,000 years ago) of Sardinia. Shoulder height: 44 cm.

The frequent advances and retreats of continental ice sheets caused correspondingly drastic rises and falls of sea levels. Massive amounts of seawater were stored in the ice sheets, and sea levels dropped by as much as 120 m during the glacial maximum. A direct consequence of this lowering of sea levels was the emergence of connections between the mainland and some of the surrounding islands, and then the reisolation of the islands when sea surfaces returned to higher levels. Such a repeated connection and disconnection between mainland and islands created opportunities for mainland animals to invade islands, but then to be subsequently cut off from their mainland relatives. Isolation on an island is often a direct impetus for speciation, commonly through adaptations to island conditions and a lack of genetic exchange with mainland populations. Two such examples of canid speciation are the extant island gray fox (Urocyon littoralis) from the Channel Islands, off the shore of southern California, and the extinct Pleistocene Cynotherium sardous from the island of Sardinia, off the west coast of Italy (figure 6.11). The former is a sister species of the mainland gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), and the latter may be derived from a hypercarnivorous, wolflike Xenocyon (Lyras et al. 2006). Finally, the Falkland Island fox (Dusicyon australis), which was hunted to extinction in the nineteenth century, may also be a product of speciation as a result of connection with the South American mainland and then isolation afterward, although the great distance between the Falkland Islands and Argentina makes such a connection more difficult to imagine, and some measure of overwater rafting may have been involved for the fox to arrive on the islands.

Finally, the modern Holocene epoch (the previous 10,000 years) is marked by a rebound of temperatures and retreat of polar ice caps, creating the environmental conditions that we live in today. Pleistocene canids on the various continents, particularly those in the late Pleistocene, are increasingly similar to their living counterparts. Probably all extant canine species evolved during the late Pleistocene, as is the case for most, if not all, extant carnivorans.

In figure 6.6, we chart the changes in diversity through time to compare the histories of the three canid subfamilies. The figure reveals a relay race among these groups since their origin in the early Cenozoic (around 40 Ma) of North America. Each subfamily shows an increase in diversity following the extinction of the preceding lineage. In the Caninae, the increase did not happen until the end of the Miocene, with maximum diversity not established until the Pliocene. Interestingly, the first departure from the generalized mesocarnivorous adaptation was to hypocarnivory, a broadening to a mixed diet. This adaptation is still represented by the gray fox (Urocyon) of the New World (whose fossil sister lineage was Metalopex), the raccoon dog (Nyctereutes) of eastern Asia, and the crab-eating zorro (Cerdocyon) of South America, which is related to Pliocene species in North America. The Borophaginae had a similar adaptive history while it was represented by small species. The relationship between the established group and the new group is suggestive of competition until extinction of the older group reduces competitors, allowing diversity to increase markedly in the younger group. Figure 6.6 suggests that the strong differentiation in the Caninae over the past 4 million years was promoted by the loss of the Borophaginae. A similar relationship is indicated by the history of the Hesperocyoninae and its effect on the Borophaginae.

Another feature of this successive aspect of canid evolution is that the adaptation of hypercarnivory is restricted mostly to lineages in the later part of each subfamily’s history, and the adaptation seems to be related mostly to the increasing size of both predators and prey. Of course, this generalization applies most clearly to the Borophaginae and the Caninae. The Hesperocyoninae was primitively hypercarnivorous and developed the molariform lower carnassial only in its latest genus, Osbornodon, which perhaps increased its longevity as a group until comparable large borophagines (for example, Tomarctus) came into existence in the middle of the Miocene (16 Ma).