AS PREDATORS WELL SUITED FOR TRAVELING long distances, modern canids are the only family of Carnivora to have a truly worldwide distribution (except Antarctica). This wide dispersal has in no small part been due to their ability to expand their home ranges and to achieve long-distance dispersal across continents and habitats. Canid zoogeography provides insights into the intricate relationships among canid species around the world. The immigrations of major lineages can be traced across different continents during their geologic history. Studies of ancestral–descendant (phylogenetic) relationships in the fossil record and the history of continental reconfigurations (plate tectonics) allow us to draw some conclusions about the timing, direction, and identity of various dispersals during the canids’ history.

Early Endemism

More than two-thirds of the history of the canids was played out in North America, the family’s continent of origin. With the exception of a single hesperocyonine lineage, two of the three subfamilies, the hesperocyonines and the borophagines, never left their home continent. Almost from the very beginning of their history, canids seem to have had ample opportunities to cross Beringia, a periodic land bridge between eastern Siberia and Alaska (the present-day Bering Strait), to expand to the Old World. Since the late Eocene (40 Ma), numerous carnivorans did just that, including members of the Mustelidae, the Procyonidae, the Ursidae, the Felidae, and the Nimravidae (an archaic group of saber-toothed “cats”), many of which crossed more than once and in both directions.

Despite these intercontinental immigrations, mammalian communities maintained a large measure of identity on their home continents. Land bridges, such as Beringia and the Isthmus of Panama, tended to be intermittent and were controlled by global eustatic sea-level changes due to ice sheet formation at the poles or local tectonic reconfigurations of adjacent plates. Land bridges located in high latitudes or near the equator, such as Beringia and the Isthmus of Panama, had a strong filtering effect in that specific environments in and around the land bridges encouraged the passage of some species, but prevented others from going through. This is the reason why fauna in North America always maintained a distinct identity through time despite the occasional connections with the outside world (either Eurasia or South America). Organisms that are confined to a particular region or continent are called endemics. Several major groups of North American mammals were either entirely or largely endemic in their continent of origin, including the oreodonts (extinct even-hoofed mammals), the camelids (camels, lamas, and their extinct relatives), and the equids (horses). Among carnivorans, the hesperocyonines and borophagines were the best examples of two groups of endemic predators that played a critical role in the North American predatory landscape for many millions of years during the middle to late Cenozoic (30 to 8 Ma) (figure 7.1).

Such endemism in both herbivores and carnivores during much of the middle Cenozoic was apparently the rule rather than the exception. The pattern of endemic distribution may reflect the effectiveness of isolation mechanisms (such as barriers formed by the seas between North America and Eurasia, and between North America and South America) or the filtering effect of a land connection that acted as an environmental bottleneck to prevent easy crossing.

Another factor that contributes to our assumption of this apparent endemism may be related to our highly biased fossil records. Most of the known fossil records are concentrated in the midlatitudes of the northern continents (Eurasia and North America). Although such an aggregation of finds may be partially attributed to socioeconomic factors (industrialized countries in the midlatitudes of the northern continents tend to explore their fossil records more fully than other countries do), this midlatitude bias may also be due to the actual preservation of fossils.

Terrestrial fossils of Cenozoic mammals tend to be more commonly preserved in fluvial (river), lacustrine (lake), and floodplain deposits. Tropical forest environments do not readily preserve fossils, or if they do, the sediments that trap the fossils are often poorly exposed because of the lush vegetation coverage. In high latitudes, in contrast, the continental ice sheets during the Ice Age (Pleistocene [1.8 to 0.01 Ma]) scraped away many of the relatively soft sediments on top that were deposited in the late Cenozoic. The result is a dearth of knowledge about fossils from both high and low latitudes, leaving us a biased view of the middle (see figure 2.14). Therefore, we know preciously little about the high-latitude faunas, which would be the most informative for immigration events across Eurasia and North America.

Nonetheless, paleontologists do occasionally stumble on rare events of animal migrations. Until recently, hesperocyonines were known only in North America, which was puzzling to paleontologists. Why didn’t the hesperocyonines make it to Eurasia? Were they not well adapted to roam large areas, as are their living counterparts, such as the wolves and foxes? Were they confined to the middle latitude of North America and unable to cross the Beringian land bridge in the high arctic region? A tantalizing hint emerged in the summer of 2005 when a team of Chinese paleontologists (led by Xiaoming Wang) unexpectedly found a partial skull of a medium-size hesperocyonine in the middle Miocene beds (Tunggur Formation, around 13 to 12 Ma) of the Inner Mongolia Province in northern China. It is the oldest canid fossil to be discovered anywhere outside North America. Despite this single hesperocyonine in Asia, however, it is fair to say that hesperocyonines did not significantly affect the Old World predator community.

FIGURE 7.1

Phyletic relationships and intercontinental migrations of canid genera

Only selected genera are listed, and the actual diversity in each subfamily (Hesperocyoninae, Borophaginae, and Caninae) is somewhat higher than shown. The width of each lineage in the figure roughly corresponds to the diversity of the lineage through time. For a more realistic sense of diversity through time, see figure 6.6. Arrows indicate directions of migrations.

The record of borophagine dispersal is even more dismal. Known fossil records of the borophagines occur as far north as the northern United States and as far south as Honduras and El Salvador. Despite their successes in both diversity and abundance, the borophagines apparently never left North America. The rise of large, hypercarnivorous borophagines apparently followed the maximum diversification of horses in the middle to late Miocene (18 to 10 Ma). It is thus reasonable to assume that horses probably constituted a major source of prey for the borophagines. Why, then, didn’t the borophagines follow the Hipparion (three-toed) horses to the Old World? The dispersal of Hipparion to Eurasia in the late Miocene (about 12 to 11 Ma) represents a major event in the history of mammalian zoogeography. Upon their arrival in Eurasia, the three-toed horses quickly diversified and expanded to the entire Old World to become a key faunal component wherever they went. They became ubiquitous in the late Cenozoic (11 to 5 Ma), and their impact on the ungulate communities must have been high.

Although for want of fossil evidence we are unable to fathom the cause of the borophagines’ failure to disperse, we can take a look at the competitive landscape as a way to explore possible scenarios. Canids and hyaenids independently evolved many similar features. So convergent were the predatory behaviors of members of these families that competitive exclusion may have played a role in explaining why canids and hyaenids were confined to their continents of origin during much of their histories. Throughout these histories, there were numerous opportunities for canids and hyaenids to disperse to continents other than their own—many other carnivorans, including felids, made the trip several times—and canids and hyaenids, with their highly developed cursorial adaptations that enabled them to travel long distances with ease, were ideally suited to cross the continents. Yet neither family made a significant dent in the other’s “home turf.” A single hyaenid, Chasmaporthetes, arrived in North America in the Pliocene (4 Ma), but was never successful enough to be a significant component of the New World’s carnivoran fauna (see figure 6.10). Chasmaporthetes was probably in direct competition with Borophagus, which was well into the last leg of its journey toward extinction. It is conceivable that some borophagines may have made it to the Old World, but met strong competition from hyaenids and were quickly eliminated.

An alternative scenario may be that the environments in and around Beringia had a strong filtering effect on which species could cross the land bridge. For example, a heavily forested environment would have favored predatory species that preferred wooded areas. Indeed, many of the medium to large carnivorans that successfully immigrated to North America during the Miocene were felids and ursids, two families that tend to prefer the cover afforded by trees (early hemicyonine ursids that came to North America, however, had long, digitigrade legs that were probably adapted to running in open environments). Recent discoveries of late Miocene to early Pliocene (6 to 4 Ma) red pandas and meline badgers (Old World badgers) in eastern Tennessee, which is part of the Eastern Deciduous Forest of the United States, may even suggest the presence of forest corridors across much of Beringia. If so, Beringia may have served as an environmental bottleneck to limit the dispersal of borophagines, which were adapted to open land. Unfortunately, we have preciously few late Cenozoic fossil records in northern Siberia and Alaska, where past faunal exchange must have occurred, and until such a deficiency can be remedied, history’s apparent paradox will remain a mystery.

Dispersal of Caninae

The subfamily Caninae, like its predecessors, remained landlocked in North America for more than two-thirds of its history, during which Leptocyon was living in the shadow of both hesperocyonines and borophagines. Canines, however, did eventually achieve a breakthrough by the late Miocene (7 Ma), making appearances in Europe, Africa, and Asia in short succession. One of the Caninae’s distinguishing characters is its more advanced stage of locomotive adaptation. For example, compared with the more primitive Leptocyon, early Vulpes had lengthened legs, a reduced first digit in the metatarsals, and no epicondylar foramen on the distal humerus—characters that are commonly associated with lengthening of the stride and reduction in the weight of the limbs (chapter 4). These cursorial developments are certainly more advanced relative to developments in the hesperocyonines and borophagines. However, it is not clear if such characters alone were enough to permit the canines to break through the geographic barriers or if environmental factors—that is, the opening up of the landscapes (chapter 6)—may have contributed to the eventual dispersal of canines (figure 7.2; see figure 7.1). Whatever the reason that canines were able to immigrate to the Old World, the predatory community there was never the same after they arrived.

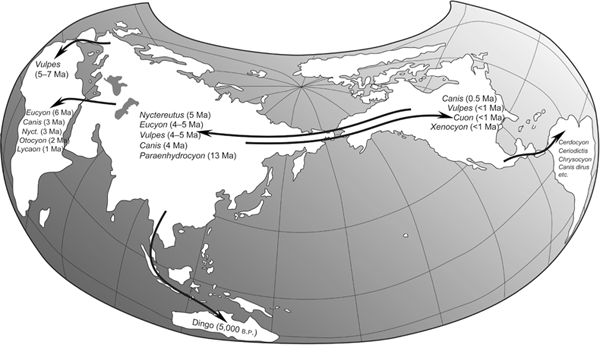

FIGURE 7.2

Intercontinental migrations of canids

As one of the most mobile groups of carnivorans, canids have worldwide distribution as a result of multiple migrations across continents. The lists given here of canids that arrived at each continent are not exhaustive, and the canids listed are a subset of all canids that made it to that particular continent. Numbers following each taxon approximate the time of arrival millions of years ago (Ma).

EUCYON AND OTHER EARLY CANINES IN THE OLD WORLD

The first canine to arrive in the Old World was a coyote-size form named “Canis” cipio (Crusafont-Pairó 1950). A maxillary fragment with P3 to M2 and an isolated lower carnassial (m1) from the Teruel basin of central Spain in deposits of Turolian age (late Miocene [about 8 to 7 Ma]) offer all that we know about this species. The relatively primitive morphology of the teeth suggests that this species was either Eucyon or a very primitive Canis. However, lacking more complete materials, we cannot determine its precise phylogenetic position.

Lorenzo Rook (1992) reported a new species of Eucyon, E. monticinensis, from the Monticino gypsum quarry near the village of Brisighella in Italy and from Venta del Moro in Spain. These Eucyon materials are also late Miocene in age (about 7 to 5 Ma), but probably slightly younger than “Canis” cipio.

In Africa, the relatively poor canine fossil records have traditionally indicated a rather late arrival of canines on the continent. However, recent findings (often associated with the explosive new knowledge of hominid-bearing localities) have pushed the canine records to ever earlier ages, comparable to the European records. Jorge Morales, Martin Pickford, and Dolores Soria (2005) described a new species of Eucyon, E. intrepidus, from the Lukeino Formation (6.1 to 5.7 Ma) in the foothills of the Tugen Hills in the Baringo District, along the Great Rift Valley in western Kenya. This species is morphologically similar to early Eucyon species (but smaller in size) from the late Miocene of Europe and early Pliocene of Asia (China).

In another recent finding associated with the earliest hominid remains (Sahelanthropus tchadensis), Louis de Bonis and his co-workers (2007) report a new fox, Vulpes riffautae, from the Djurab Desert, northwest of N’Djamena in the West African country of Chad. This new fox is associated with fossils from the late Miocene (around 7 Ma). If this age estimate is correct, then Vulpes riffautae would be the earliest vulpine record in Africa, possibly even the earliest in the entire Old World. The Chad fox was very small, barely larger than a modern fennec (Vulpes zerda), which is the smallest living fox in the world.

Based on these materials, it appears that canines of the Eucyon–Canis stage of development and a small fox were already present in the late Miocene of Europe and Africa. Fossil records of canines in Asia, however, are slightly younger, from the early Pliocene and later (less than 5 Ma), even though canines must have passed through the vast stretch of Asia to arrive in Europe and Africa. Such a lag in the arrival of canines in Asia may simply be attributed to relatively poor documentation of the Asian fossil record. However, an alternative scenario may be that the first canines that crossed over Beringia stayed in higher latitudes, bypassing the midlatitude regions of Asia, where our records are currently based, and going straight to Europe.

Whatever the scenario, canines are firmly recorded in the early Pliocene deposits of northern China, particularly in the Yushe basin in central Shanxi Province. In the Yushe basin, Nyctereutes (N. tingi) appeared shortly after 5 Ma, followed by Eucyon (E. zhoui and E. davisi) slightly later. In fact, the presence of Eucyon in the Old World was first documented by Richard Tedford and Qiu Zhanxiang (1996) from the Yushe records. Since then, increasing evidence suggests that this transitional genus had a modest success outside its continent of origin, North America. Several of its species are currently recognized in the fossil records of Asia, Europe, and Africa, and these species are in general considered the earliest canines in the Old World.

RACCOON DOG

The raccoon dog (Nyctereutes) was an important early immigrant to the Old World. In the Yushe basin, the primitive species N. tingi entered the record in the latest Miocene to the middle Pliocene (5.5 to 3 Ma). At about the same time, the European species N. donnezani lived in the area of present-day Perpignan, France. These ancestral raccoon dogs were coyote-size animals, much larger than their modern counterpart. More advanced species, N. sinensis in China and N. megamastoides in Europe, soon appeared in Eurasia, and they eventually led to the living species N. procyonoides in East Asia. By the early Pliocene (3.8 to 3.5 Ma), Nyctereutes had reached Africa, but the African raccoon dog did not survive beyond the Pleistoene (1 Ma) (figure 7.3). The modern raccoon dog is a descendant of the N. sinensis–megamastoides lineage in Eurasia, surviving because it became smaller in size and more hypocarnivorous in dental adaptations. The modern East Asian raccoon dog was introduced to northern Europe in the twentieth century.

FIGURE 7.3

Nyctereutes terblanchei

Reconstructed skull and head of Nyctereutes terblanchei. The mandible reconstruction is based on a fossil from Kromdraai-A (1.6 Ma); the skull, after other species of the genus. Although the modern raccoon dog has an original Asian distribution with artificial introductions into Europe, the distribution of Nyctereutes in the Pliocene and Pleistocene (5 to 1 Ma) reached as far as South Africa. Mandible length: 14 cm.

Although the Old World history of Nyctereutes can be traced by a useful fossil record, it is still far from clear what its original stock in North America was. Nyctereutes seems to be closely related morphologically to the South American crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon) in that both share a somewhat hypocarnivorous dentition and an enlarged angular process (a small bony protrusion on the lower jaw for insertion of the pterygoid muscles), among other characters. According to this scenario, Nyctereutes probably arose from a common ancestor of a Cerdocyon–Nyctereutes lineage in North America. Records of Cerdocyon from the early Pliocene (5 Ma) of Texas and New Mexico suggest that the Old World Nyctereutes could have arisen from a North American stock close to Cerdocyon. However, molecular studies by Robert K. Wayne and his colleagues (1997) place the raccoon dog at the base of the living canines. This hypothesis suggests that the raccoon dog is either more basal to the vulpines or within the fox lineage (see also Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005).

BAT-EARED FOX

The living African bat-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis) is a peculiar canine distinguished by an extra molar at the back of the lower tooth row due to its insectivorous diet. Based on our morphological analysis (Tedford, Taylor, and Wang 1995), Otocyon seems to be closely related to the North American gray fox (Urocyon), which has never left its native continent. The Otocyon lineage had arrived in the Old World by the late Pliocene (3 Ma) in the form of a transitional genus, Prototocyon, from India, although its record in Africa may be somewhat earlier (around 4 to 3 Ma). The extant Otocyon was presumably derived from Prototocyon in Africa.

FOXES

The earliest and most primitive foxes (tribe Vulpini) were a small, California species (Vulpes kernensis) and a larger, continent-wide species (V. stenognathus) from the late Miocene (about 9 to 5 Ma) of North America. Although a small Vulpes, V. riffautae, had made it to West Africa by as early as 7 Ma, Eurasian foxes appeared somewhat later. Vulpes beihaiensis from the early Pliocene (4 Ma) of China and V. galaticus from the early Pliocene of Çalta in Turkey were among the earliest foxes in Asia and Europe. A number of Vulpes species appeared in the Plio-Pleistocene of Eurasia and Africa. Up to 12 species of Vulpes (including the arctic fox, which is sometimes included in a distinct genus of its own, Alopex) have survived to the present time throughout Africa, Eurasia, and North America, making it the most diverse living canine genus.

Vulpes is one of a few canines that returned to North America, where it had originated. After the two ancestral species of North American Vulpes in the late Miocene (6 Ma), V. kernensis and V. stenognathus, foxes became rather sparse during the Pliocene (5 to 1.8 Ma), as indicated by the fossil record. The genus did not reappear in North America until the middle Pleistocene (1 Ma). By then, the main theater of Vulpes diversification had shifted to Eurasia. By the latest Pleistocene, the red fox (V. vulpes) and arctic fox (V. lagopus) had expanded to North America. The swift fox (V. velox) and kit fox (V. macrotis), however, may have been native North American species.

CANIS GROUP

The first Old World immigrants—Vulpes, Eucyon, and Nyctereutes—were not conspicuous predators of their time, despite their presence in the late Miocene and early Pliocene. These small to medium-size canines became important components in the carnivoran community, but were far from achieving a top-predator status. The arrival of Canis, however, finally ushered in the era of dominant canines in the northern continents.

During the middle Pliocene (4 to 3 Ma), a wolf-size Canis, C. chihliensis, first appeared in northern China. Shortly later, Eurasia became a vast playground for Canis evolution, setting off a wave of diversification that established the family’s ultimate success. Canis quickly spread to Europe through the species C. arnensis, C. etruscus (figure 7.4), and C. falconeri, which either retained primitive characters of the genus or acquired hypercarnivorous characters in the direction of the hunting dogs (Cuon and Lycaon). This sudden expansion of Canis at the beginning of the Pleistocene (about 1.8 Ma) is commonly known as the Wolf Event and is associated with the origin of the mammoth steppe biome following intense continental glaciations.

The gray wolf (Canis lupus) appeared in Europe toward the end of the middle Pleistocene (0.8 Ma), but not in midlatitude North America until the latest Pleistocene (about 0.1 Ma). An older record of the gray wolf can be found in the early to middle Pleistocene Olyor Fauna of Siberia and its equivalent in Alaska (the arctic Beringia). Wolves thus originated in Beringia, perhaps in coevolution with the large ungulate assemblage of the arctic biome. They seem to have invaded the midlatitudes of North America, as did many of the large Beringian ungulates, only during the last glacial cycle, becoming characteristic members of the latest Pleistocene and living fauna.

That the modern gray wolf has achieved the ultimate success of being the most widely distributed species of large carnivorans is probably due to its propensity for dispersal. One of the strategies that gray wolves use to obtain a breeding position is directional dispersal. Young adult wolves of both sexes, in order to escape their subdominant position and to establish their own breeding pack, move in a single direction for more than 800 km. Such a remarkable ability to disperse for a long distance in a single generation is perhaps the most important reason behind their wide distribution. The modern gray wolf and red fox have the widest distributions of any mammalian species, occupying the entire northern continents of Europe, Asia, and North America (Holarctic), as well as North Africa in the case of the red fox.

FIGURE 7.4

Comparison of Canis etruscus and Pachycrocuta brevirrostris

Life reconstruction of the European dog Canis etruscus, from the early Pleistocene (1 Ma), shown to the same scale with the giant hyena Pachycrocuta brevirrostris. Large hyaenids and canids sought similar resources (carcasses and live ungulate prey), and they would have competed in the European ecosystems of around 1 Ma.

The dire wolf (Canis dirus), made famous by the stunning number of individuals recovered from the Rancho la Brea tar pits in Los Angeles, is another lineage that can be traced to Eurasia. This wolf of the middle to late Pleistocene (1 to 0.01 Ma) is the largest species ever to have evolved in the subfamily Caninae. Our phylogenetic analysis suggests that C. dirus arose from the large wolf C. armbrusteri, which suddenly appeared in the early Pleistocene (1.5 Ma) of North America. These species share a suite of hypercarnivorous characters, indicating that the dire wolf arose in North America in the middle Pleistocene (1 Ma). Before its extinction in North America, the dire wolf managed to expand to the north and west coasts of South America and establish itself as the most formidable predator in the New World. It had become extinct by the latest Pleistocene (10,000 years ago) as part of the megafauna extinction.

In a comparable evolutionary burst in the middle Pleistocene of Eurasia, the Canis falconeri group gave rise to the widespread hypercarnivore Xenocyon, which in turn gave rise to the dhole (Cuon) and the African hunting dog (Lycaon). Cuon appears in the fossil record in the middle Pleistocene deposits of Southeast Asia (C. javanicus fossilis). An isolated record of Lycaon is found in the late Pleistocene Hayonim Cave of Israel. The Lycaon record in Africa is poorly known, but this genus possibly occurred as early as the middle Pleistocene, as indicated in the fossil records at the Elandsfontein site of South Africa (Ewer and Singer 1956). During the late Pleistocene, Xenocyon and Cuon also wandered into North America, briefly enriching the fauna of the New World.

CERDOCYONINES

Our morphological analysis indicates that the South American canines (subtribe Cerdocyonina) belong to a natural lineage whose common ancestor was a sister group of the Eucyon–Canis–Lycaon clade (Tedford, Taylor, and Wang 1995) (see figure 7.1). Such a relationship is also increasingly borne out by DNA sequence analysis (Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005). Long before the establishment of the Isthmus of Panama in the middle Pliocene (about 3 Ma), however, certain lineages with cerdocyonine affinities had already shown up in North America during the late Miocene to early Pliocene. They are represented by records of Cerdocyon (C. sp. A) from the late Miocene (6 to 5 Ma) and of Theriodictis (T.? sp. A) and Chrysocyon (C. sp. A) from the early Pliocene (5 to 4 Ma). Our proposed sister relationship between the South American clade and Eucyon davisi also implies an early appearance of the cerdocyonines, possibly a few million years earlier than the current fossil record indicates and presumably in the Central America region where the fossil record is very poor.

This early diversification of the cerdocyonines in North America prior to the opening of the Isthmus of Panama implies that the migration to South America must have been undertaken by more than one lineage. Representatives from at least these three genera—Cerdocyon, Theriodictis, and Chrysocyon—must have independently crossed the Isthmus of Panama, and others probably did as well. Thus the large diversity of South American canines was probably built on top of a group that was modestly diverse while still in North America.

Once in South America, the cerdocyonines suddenly faced a fauna made up of native marsupials and notoungulates (large herbivores restricted to South America). The cerdocyonines underwent an explosive radiation to become the most diverse carnivoran group in South America, presumably at the expense of the native borhyaenids (chapter 2). In addition to forms that constitute the modern cerdocyonines—such as the short-eared dog (Atelocynus), the bush dog (Speothos), and the various zorros (Pseudalopex and Lycalopex)—the hypercarnivorous genus Protocyon, which is extinct, was also part of the native radiation. Beside the cerdocyonines, species of Canis were able to take advantage of the land bridge. The oldest canine species, C. gezi, is known only from deposits of Ensenadan age (early to middle Pleistocene [1 to 0.5 Ma]) in Argentina. Canis gezi and C. nehringi found in Lujanian (late Pleistocene [0.2 Ma]) sediments in Argentina possibly are closely enough related to the dire wolf (C. dirus) to suggest an earlier Pleistocene arrival and the modest differentiation of a dire wolf lineage in South America. Together, Cerdocyon and Canis established themselves as a dominant group of predators and permanently altered the carnivore communities in South America.