There were 33 teams of international observers, or 528 individual team members. Of the 33 teams [counting national delegations], 24 teams or 324 individual team members judged the elections to be generally free and fair while nine teams, or 204 individual team members, generally condemned the elections as neither free nor fair. . . . Taken together, the majority carried the day and so, the minority should submit to the verdict of the majority.

—The Herald, a government-controlled newspaper, after the 2002 Zimbabwe election1

THE RISE OF MONITORING had the paradoxical effect of encouraging numerous countries to invite international monitors and then cheat right in front of them. The election in Panama in 1989 was a prime example, and although the U.S. invasion that followed demonstrated the hazards of such behavior, it nonetheless continues. In 2004, for example, monitors logged enough problems to find about one-fifth of the elections they observed unacceptable. Even in Afghanistan in 2009, when the eyes of the entire world were directed toward the country, cheating was blatant. This chapter explores the challenges continued cheating has raised for international monitors and how it has changed the market for monitoring, that is, the availability and use of different monitoring organizations.

As Chapter 2 made clear, countries invite monitors for various reasons. Perhaps they receive foreign aid and are under some form of democracy-related sanction, or are under pressure to demonstrate improved domestic governance to continue or resume benefits from the international community. Or perhaps they need international observers to obtain domestic approval because the government is unstable or the country is undergoing transition and needs to demonstrate that the election is not stolen. For a variety of reasons countries find themselves in need of international approval of their elections.

For governments that are actually willing to hold honest elections inviting monitors is unproblematic: The monitors will come and praise their progress, and the country will obtain the desired approval. This was the situation facing several countries that underwent transitions in the early 1990s and whose abundant invitations to international organizations helped bring about the rise in international election monitoring.

What is a government to do, however, if it needs the monitors’ approval, but fears that the risk of losing an honest election is too high? A cartoon drawn right after Mexico’s long-ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) lost its legislative majority in the 1997 midterm election illustrates the dilemma of holding honest elections (Figure 3.1). So, what if a governing party is not willing to risk losing? Although international pressure can induce countries to permit monitors into their country and although in some countries opposition parties or electoral commissions are able to make independent decisions to invite monitors, the decisions to allow international monitors are ultimately made by government leaders—persons who aspire to hold power and have the ability to block monitors from being invited or from entering. This is especially true in countries where the governments tend to cheat in elections, because these are the governments that also are most resourceful about bending the rules to their advantage. From their perspective, the legitimacy that monitors can bestow on their country is a poor reward if making the required electoral improvements forces them out of office. What good is legitimacy to an ousted leader? In countries with a history of undemocratic politics, politicians and governments with low odds of winning without cheating are reluctant to run this risk.

On the other hand, for most governments simply refusing monitors is also a bad idea because it essentially amounts to a self-declaration of cheating. As a veteran observer and senior vice president of the International Republican Institute (IRI) has noted: “Those governments that oppose this kind of engagement from the international community have something to hide.”2 Such a characterization may be tolerable for countries that do not need or want to woo the international community or countries whose governments face little domestic opposition (such as Egypt under Mubarak or Cuba), but it is clearly undesirable for countries that may lose aid or other benefits or risk domestic unrest.

However, there is a third alternative to inviting monitors and running clean elections or simply refusing monitors. Governments can invite monitors but continue to cheat and hope monitors will not discover the cheating. That is, governments may count on the fact that monitoring activities are extremely difficult to implement, lack adequate resources, and are subject to many other constraints. To improve their odds, governments can actively seek to manipulate not only the elections, but also the monitors themselves: their access, their working conditions, and even the information they can access. For example, in 2005 Kazakhstan’s government reportedly even conducted intelligence operations against the election monitors,3 and in 2007 the Kazakh Embassy in Washington tried to stack the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) mission in its favor by sending letters to its friends, encouraging them to enlist as OSCE observers.4 Thus, governments may simply gamble on the chance that monitors do not discover their cheating. Such a gamble is, after all, an improvement in the odds over a certain denouncement for refusing monitors.

Figure 3.1: The dilemma of holding honest elections

Jeff Danziger / © 1997 The Christian Science Monitor. Reproduced with permission.

However, for many governments even this gamble is too risky; a safer option is needed, even if the legitimacy or approval it renders is compromised. To meet this need, a shadow market for election monitoring has developed: a supply of lenient monitoring organizations. Rather than taking a chance on the foibles of more critical monitors, governments may avail themselves of a supply of friendlier monitors supported by countries or organizations that realize the benefit of such alternatives. These organizations are akin to the phenomenon of government-organized nongovernmental organizations, or GONGOs, which some governments create to thwart actual nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).5 Frequently these monitoring efforts are small parliamentary delegations from friendly countries, but they may also be delegations from formal organizations such as the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).6 The assessments of these shadow organizations are less respected by the democratic countries of the world, but they may nonetheless be useful with some domestic audiences or with other autocratic governments, and, as the opening quote to this chapter shows, they may be useful in limiting the influence of more critical monitoring organizations.

The 2008 election in Belarus illustrates how international monitors can be used for show. A commentator notes the election was “orchestrated primarily for US and European consumption, with the primary purpose of improving Belarus’ international image. The country’s top election official has made it clear that the Central Election Commission’s primary goal is to ‘have the results be recognized by the international community.’ ”7 Opinion polls showed the people of Belarus were very supportive of international monitoring, but the regime focused on its relationship with Europe and one-third of media coverage was about the international monitors rather than about domestic politics. Furthermore, the government “concentrated on the more friendly Commonwealth of Independent States observers. During the second week of August, the state news agency Belta devoted four times as much coverage to the CIS monitors as to their Western counterparts,”8 and used “cosmetic changes in routine” to “produce good publicity” to impress the international community.9

By inviting friendlier monitors, either alone or together with the more credible organizations, dishonest governments can deflect or spin criticism while still claiming they are participating in the monitoring regime. In 2002, Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe officially prohibited the European Union (EU) from monitoring the election, but admitted other organizations. Sometimes rulers play a complicated game of veiled intentions. Russia, for example, increasingly vexed with the role of the OSCE in the region, formally invited the organization for the December 2007 Duma election and the March 2008 presidential election, technically fulfilling its OSCE obligations to accept monitors. In both cases, however, the OSCE eventually turned down the invitation, citing too many delays and restrictions that would hinder the organization from exercising its mandate. Sometimes the Organization of American States (OAS) also receives invitations rather late, making it difficult to mount proper missions, even if a mission is sent.10 The OAS declined Venezuela’s invitation to observe the October 21, 2004, election, after receiving an invitation only two weeks in advance. The director of the OAS Department for Democratic and Political Affairs, John Biehl del Río, said, “The proximity of the electoral process impedes us from having the necessary time to organize a mission able to meet all the technical, operational and financial requirements that an observation at this level demands.” He urged Venezuela to allow greater lead time as had occurred in the past.11

The shadow market is not confined to specific monitoring organizations; all organizations may behave as shadow monitors at times. Even highly professional and well-equipped organizations face political and normative constraints that sometimes lead them to tone down their criticism of an election. Although monitoring organizations may attempt to avoid sensitive situations, these very situations are often high-profile events in which they may be compelled to participate for a variety of reasons. The 2009 election in Afghanistan, for example, was clearly going to be politically sensitive for the West—and for the United States in particular. Western countries, deeply embroiled in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) engagement in the country, were keen to see a continuation of the regime to ensure maximum stability. Despite their vested interest in the outcome, simply skipping any monitoring of this election was not politically feasible. Similarly, Western governments, which are often the main supporters of international monitoring organizations, may have important state allies. They may push for monitoring organizations in these countries, because they need to be able to claim that the governments they deal with have some legitimacy, even if it is mostly artificial. As a result, some organizations have mixed records, acting critical at times and suspiciously lenient at other times.

The remainder of this chapter explores this pair of conundrums on the part of both monitoring organizations and the governments. It shows the pattern of invitations and the pattern of assessments by different organizations, which are consistent with the argument that a shadow market for monitoring has developed. Together with the following chapter, which statistically examines the factors correlated with endorsements of elections, it thus addresses one of the core questions in this book: Do monitoring organizations actually provide credible and quality information about elections?

International monitors have long been criticized for endorsing flawed elections and failing to condemn flagrant fraud,12 but the extent and nature of this problem has not been systematically evaluated. The fact that monitoring organizations sometimes provide questionable information is apparent in at least two different trends. First, sometimes the assessment of the monitoring organizations flagrantly differs from that of others in the domestic and international community. The Bosnia 1996 election discussed in the following chapter is a case in point. Here both the United Nations (UN) and the OSCE papered over severe problems, which others pointed out frankly. Second, sometimes, as in Chad in 1996,13 monitoring organizations outright contradict each other.

Zimbabwe’s 2000 election exemplifies a case where all the organizations present were too lenient. The election occurred amid deepening economic and political crisis. Although the U.S. State Department criticized widespread voter intimidation, pre-election violence, vote rigging, and other irregularities,14 the missions of the South African Development Community (SADC) and the African Union (AU) endorsed President Mugabe’s victory. The AU observers said voters had been free to express their will and pronounced the election smooth and peaceful.15 The SADC delegation also stressed the orderly polling day.16 The Commonwealth Secretariat (CS) noted many problems that it said had impaired freedom of choice, but it too praised polling day.17 The EU observers were the most critical, but although they noted that violence marred the election, they stopped short of questioning the final results and praised the orderly voting day.18 EU Commissioner for External Relations Chris Patten said in a public speech to the European Parliament (EP) that “the report . . . concludes that [the election] was by and large satisfactory.”19 (Nevertheless, the EU was too critical for Mugabe’s taste, and for the subsequent election in 2002 Mugabe refused several EU monitors access, prompting the EU to refuse to monitor altogether.20) In 2000, after the monitors left, Mugabe noted that “today the majority of them go away both humbled and educated, convinced and highly impressed by how we do things here.”21

Disagreements among international monitoring organizations are quite common. In fact, when multiple organizations are present they disagree more than one-third of the time.22 Sometimes disagreements occur simply because one organization remained ambiguous even if others disapproved of an election, or because some organizations endorsed an election although others chose to remain ambiguous. Particularly striking, however, are cases where organizations were diametrically opposed: One organization said the election was acceptable, while another found the election unacceptable. The elections in Cambodia in 1998 and Kenya in 1992 provide good examples.

The 1998 Cambodia election was held in a terribly violent pre-election environment. The security forces threatened, beat and killed opposition politicians. Brad Adams of Human Rights Watch argued that the brutal murder of opposition journalist Khim Sambo was “timed just before the election to have the maximum chilling effect on journalists, opposition party supporters, and human rights monitors.”23 A last-minute change of rules aided the incumbent’s victory, but rendered the outcome highly questionable.24 A joint memorandum by the National Democratic Institute (NDI) and the IRI called the pre-election environment “fundamentally flawed.”25 Although the NDI chair was criticized for hailing the election as the “Miracle of Mekong,”26 the NDI issued a highly critical detailed report.27 The IRI final report declared that the election “did not meet the standards of democratic elections” and noted that “the final vote count and post-election period were deliberately incomplete as the NEC [national election commission] and Constitutional Council dismissed complaints of vote fraud and irregularities without full and proper legal proceedings.”28 In contrast, the UN and the EU, cooperating under the Joint International Observation Group (JIOG), stated even before counting was complete that “in general the polling achieved democratic standards. . . . What could be observed by us on Polling Day and Counting Day was a process which was free and fair to an extent that enables it to reflect, in a credible way, the will of the Cambodian people.”29 After monitors left, violence erupted and there was an attempt on the life of the victorious incumbent.

Kenya provides another example of assessments that appear contrary to the facts. In the early 1990s, President Daniel arap Moi began to respond to international pressure. He released several political prisoners and reluctantly dismantled the one-party system. A critical opposition press began to flourish before the 1992 election.30 But when it looked like Moi’s political career was over,31 he orchestrated interethnic violence to divide the opposition along ethnic lines.32 The government refused to register millions of eligible voters in opposition strongholds, stacked the electoral commission with its supporters, and denied the opposition access to the media and permits for rallies.33 Election day was fraught with problems, but voting was relatively calm.34 With a fragmented opposition, Moi won the highest percentage of votes and was sworn in as president. After the polling, the IRI said the election was an important step for Kenya, but “the electoral environment was unfair and the electoral process seriously flawed.”35 The CS, however, announced even before the counting was over that “the evolution of the process to polling day and the subsequent count was increasingly positive to a degree that we believe that the results in many instances directly reflect, however, imperfectly, the expression of the will of the people.”36 When ethnic clashes nevertheless erupted, international actors tried to calm the violence and urged the opposition to take the seats in Parliament and seek redress through legal channels. Eventually Moi suspended the new parliament for about six weeks and gained the upper hand. By November 1993, the international donor group resumed aid to Kenya, citing the positive economic and political reforms. The 1997 election was essentially a repeat of this pattern.37

Monitoring organizations do not disagree merely because they apply different standards. As the European Commission has shown in its compendium of legal texts, states around the world are committed, at least on paper, to quite similar standards.38 Experts from the Carter Center (CC) have also compiled international commitments that underscore this.39 Furthermore, election monitoring reports have long shared a basic structure. On some issues such as family voting there may be varying standards, but even this is generally discouraged. Therefore, disagreements cannot simply be dismissed as varying standards or cultural differences.

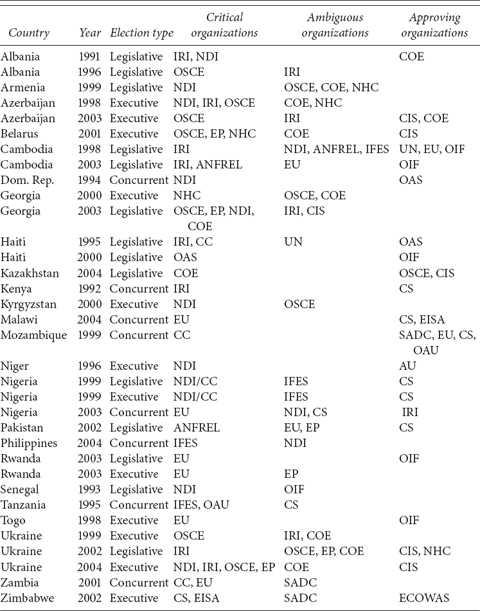

To understand how organizations vary in their propensity to criticize elections, it is useful to examine when they have disagreed with each other. Table 3.1 shows the assessments of different organizations in thirty-four elections where at least one monitoring organization assessed the election as unacceptable, but other organizations either were ambiguous or endorsed the election. Such cases are becoming more frequent with time and the more lenient organizations are often more recently established groups such as the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF) or the CIS.

As the table shows, many organizations—even the most established—at times assess elections more leniently than others. However, before accusing organizations of excessive leniency, it is important to consider other possibilities. Perhaps organizations sometimes have incentives to portray an election as more fraudulent than it was. Evidence for this is scarce, however. Although a few instances have been brought to light where monitors may have been keener to criticize some elections, as in Venezuela,40 there is very little evidence that monitors fabricate irregularities. Russia routinely accuses the OSCE of bias, but there is no evidence that the OSCE or the organizations that often support it are manufacturing reports of election irregularities.41 It of course possible that some observer groups lack sufficient understanding of the local processes and misinterpret their own observations, thus leading to claims of fraud based on misunderstandings. The Independent Review Commission on the 2007 election in Kenya describes this possibility, although the commissioners disagreed whether this was the case.42

TABLE 3.1

Thirty-four disputed elections, 1990–2004

Notes: Data on many OAU/AU and ECOWAS missions are missing. When available, assessments of these organizations were derived from news sources. Had all assessments been available, these organizations would probably figure more often among the approving organizations. Some organizations such as the SADC and the Electoral Institute of Southern Africa (EISA) have conducted relatively few missions and therefore are less likely to appear in the table. For a list of abbreviations, see page xix.

Figure 3.2: The distribution of all election assessments by different monitoring groups Organizations are ordered from left to right by the percent of elections they criticized, with the NDI being the most critical. The figure for the UN should be interpreted with caution, because it rarely issues formal reports.

* Based on less than 10 observations. For a list of abbreviations, see page xix.

**The figures for the OAU/AU and the ECOWAS are estimated based on news reports, because formal reports were seldom available.

Another way of looking at the individual organizations is to compare all their assessments, as in Figure 3.2. This is interesting, but not very helpful in understanding differences between organizations, however, because some organizations may appear more critical simply because they systematically monitor more problematic elections.

It is more useful to compare assessments of elections of similar quality by instead asking: When an organization monitors a highly problematic election, how often does it criticize that election? Figure 3.3 shows the results.43 The CIS is the least critical organization, criticizing only one of ten highly problematic elections. Indeed, the CIS monitoring activity is widely discredited and regarded as having been created merely to counter the criticisms of the OSCE in the former Soviet region.44 The International Human Rights Law Group (IHRLG) also appears rather uncritical. It “observed” the 1984 election in Nicaragua and the 1989 election in South Africa, and did not criticize either. However, the IHRLG was a pioneer in the field of election monitoring, before monitoring practices became standardized. It consisted of American lawyers who attended elections in the late 1980s and scrutinized domestic election laws, but it rarely issued critical statements and has ceased operating. The two UN missions included in this comparison are the 1995 election in Haiti and the 1998 election in Cambodia. In both cases other organizations denounced these elections, but the UN did not. Indeed, the UN is rarely critical, but this is partly because it often does not have a mandate to publically assess the election. OIF, one of the least critical organizations, has been described as “cautious” and rarely critical, and the AU as severely constrained.45 The CS is also often criticized as too lenient.46

Figure 3.3: The percent of highly problematic elections criticized

Problematic elections are those rated unacceptable by other monitoring organizations or the U.S. State Department. For more information on coding, see Appendix A. For a list of abbreviations, see page xix. The numbers in parentheses are the number of highly problematic elections attended by each organization for which public post-election documents also exist.

Perhaps surprisingly, the Council of Europe (COE) and the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), both of which have very good reputations, appear quite uncritical overall. This is because both organizations tend to remain ambiguous in their evaluations when elections are bad. (See Table 3.1 for several examples of this.) It is no wonder then that Russia has continued to cooperate with the COE, while being much less cooperative with the OSCE.47 Overall, this comparison of assessments of problematic elections corroborates the conclusions of many of the case studies written by scholars and practitioners.

The analysis above as well as in the previous chapter reveals that monitoring organizations are a very mixed group. They have different institutional origins, cultures, members or sponsors, ideological contexts, areas of operations, and so forth. Most notably, however, they have very different track records when it comes to criticizing elections.

The fact that some organizations are less critical than others does not by itself mean that countries use these organizations strategically nor does it prove the existence of a shadow market. However, examination of individual cases suggests that cheating governments do seek to invite those organizations they expect will be most friendly. This was the clear strategy of Zimbabwean President Mugabe, whom international donors pressured to invite monitors in 2000.48 Although voter intimidation, violence, and reports of vote rigging and other irregularities were so widespread that the U.S. State Department denounced the election,49 the organizations invited by Mugabe such as the SADC and the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) endorsed his victory.50 Both organizations have strong ties to Zimbabwe and could be predicted to be mild in their criticism based on their records. The SADC delegation even went so far as to say that the election “set a good example” for other SADC countries.51 The CS noted that “these elections marked a turning point in Zimbabwe’s post-independence history.”52 The EU observers were the most critical,53 so for the next election in 2002, Mugabe refused them access and even received OAU support for this.54

Similarly, when Russia released the list of certified international monitors for the March 2008 presidential election, the majority of the invitations were to groups and nondemocratic countries from which Russia could expect a friendly disposition. As Election Commission Chairman Vladimir Churov said of the invitations, “If you invite a guest, you invite someone you want to see, not just someone curious to see your house, right?”55 The OSCE was nevertheless officially invited, because Russia is obliged to do so under its OSCE commitments, but as discussed earlier the restrictions on its work eventually forced the OSCE to cancel its mission.56 Governments such as Zimbabwe’s and Russia’s have learned how to invite a mix of international observers to increase the likelihood of favorable assessments and to foster disagreements among observer groups.57 At best these practices offer only pseudo-legitimacy in the international community, but they do allow dictators who control domestic media to spin the story to the domestic audience and to friendly governments in their regions.

Figure 3.4: Percent of monitored countries inviting only less critical monitors

Number of observations = 438 monitored elections.

Less critical organizations are defined as the ones in Figure 3.2 that are less than 50 percent likely to criticize a highly problematic election. Regime types are measured by political rights as coded by Freedom House.

These are of course only individual cases. Some governments reside in regions where the less critical organizations operate, so an invitation to one of these groups is not necessarily strategic. However, if the government invites only less critical organizations without inviting other more credible observer groups as well, this suggests the invitation may indeed be strategic. A systematic review of the practice of inviting friendly monitors shows a clear pattern. Less critical organizations are twice as likely as the other organizations to monitor elections alone. Furthermore, autocratic governments are most likely to rely on these organizations alone (Figure 3.4). About 45 percent of the time countries having the worst political rights scores invite only less critical observers. This contrasts with just about 20 percent of the time for regimes with the best political rights. There is a clear, statistically significant trend for more autocratic regimes—those with higher Freedom House Political Rights scores—to host less critical monitors without inviting other monitoring groups.58

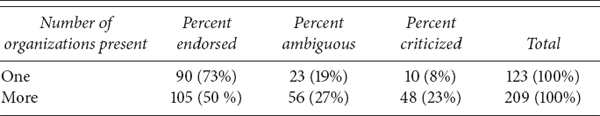

TABLE 3.2

Strictest monitoring assessments when one organization is present versus when more are present

Notes: Pearson chi2(2) = 18.8210; Pr = 0.000.

The data also suggest that organizations tend to be less critical when they monitor elections alone. When monitors are alone, they criticize elections only 8 percent of the time, but when more than one organization is present at least one organization criticizes the election 23 percent of the time. Thus the likelihood of criticism is about two-thirds lower for elections with solitary monitoring organizations (Table 3.2). For an incumbent government, a two-thirds drop in the likelihood of criticism may be very attractive indeed, even if the organizations will not bestow a whole lot of legitimacy.

Of course, it is possible that more organizations simply flock to worse elections, but additional statistical analysis (see Appendix B) confirms that the quality of the election is not likely to explain all the difference, and that solitary monitoring organizations are at least three times less likely to be critical.

Do monitoring organizations actually provide credible information about elections? The analysis suggests that not all organizations do and certainly not all of the time. This confirms longstanding criticisms. Furthermore, assessment problems cannot simply be attributed to the enormity of the task, or that the scarcity of resources sometimes lead organizations to misjudge. Rather, the data reveal distinct patterns. The evidence points to the existence of a shadow market in which organizations are sometimes intentionally too lenient, and in which some organizations are consistently more lenient than others. Thus, monitors sometimes endorse elections that do not meet common international standards. At other times they remain ambiguous despite convincing evidence of significant violations. In these situations the organizations tend to claim that they are simply following organizational policy to remain neutral. However, their willingness to critically assess other elections makes this look more like a convenient excuse. As Figure 3.2 shows, very few organizations never criticize any elections and can therefore claim that they are, as a matter of principle, refraining from judging an election. Only the UN is perhaps credible in this regard because its mandate is often restricted.

Thus, the track record of different organizations varies greatly. This variation stems not only from the fact that organizations monitor different elections. Rather, organizations have different propensities to criticize elections, with several of the more lenient organizations such as the CIS, SADC, and the Electoral Institute of Southern Africa (EISA) having entered the field of monitoring only in the end of the 1990s or later. Importantly, many more autocratic governments strategically invite less critical organizations. Furthermore, when organizations are invited without other organizations to provide a check on them, they are less likely to be critical. And even if governments cannot avoid inviting more critical observers, having less critical observers in the mix can serve their interest by making it easier to spin the statement of the various groups present.

A shadow market of monitoring thus exists, in which some organizations are created or at times willing to provide less critical assessments and bestow pseudo-legitimacy on the governments that are not willing to risk holding clean elections. As the following chapter discusses further, this is a precarious development for the broader election monitoring endeavor and for democracy promotion in general, because it undermines the credibility of the process and thus weakens its leverage.

This troublesome development is somewhat counteracted by efforts by international observers to raise their own standards and to appear as credible and systematic as possible. In the recent years many organizations, led by the EU, the OAS, and the OSCE, have published extensive manuals on election observation. Furthermore, under the UN aegis, several organizations have successfully crafted a declaration on principles of international election observation.59 This is all well and good. However, political concerns can still override even systematic assessments, and any organization is free to sign the UN declaration. Many organizations, even the most experienced signatories, continue to violate its content.

The analysis thus casts some light on one of the central questions of this book: Does international election monitoring improve the international community’s information about the quality of elections? Although monitor information is uncontroversial in many elections, the range of assessments and disagreements discussed above clearly shows that not all information from monitoring organizations is of high quality. Thus, monitoring organizations sometimes fall short in fulfilling their professed primary objective of providing reliable information on the election. Furthermore, the quality of information varies considerably among organizations, but also between elections. This raises the question of the extent to which these patterns are predictable. When are monitoring organizations likely to be less credible? What characteristics do the less credible organizations share? The following chapter examines these questions further.