The WFM, Big Bill, and the Wobblies

WRITING IN 1907, John Curtis Kennedy of the University of Chicago argued that trade unionism and Socialism were essentially the same movement. Trade unionists and Socialists, he argued, “hold to practically the same views and are seeking the same ends . . . it is only a question of time before trade-unionists in America will recognize this fact and lend their support to the Socialist party”—and, indeed, many were already doing so.1 Even the American Federation of Labor (AFL) during this period was not as anti-Socialist and revolutionary as commonly supposed. Its step toward independent political action in 1906 led, in many cases, to closer working relations with Socialist parties. Socialists within the AFL and various trade unions had been working for this result. Still, the AFL had an ample number of critics from the left. Many Mountain westerners, especially the unskilled and semiskilled workers in and around mining areas, were impatient with what they saw as the slow-moving, conservative AFL. For radicals the craft unions, which the AFL prized, stood in the way of worker solidarity.

At the same time, the region’s chief industrial union was having its own problems. Following the violent and unsuccessful confrontation with mine owners in Colorado, overall membership in the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) fell from around 28,000 in 1903 to 24,000 in 1904 and did not rebound to the 28,000 level until 1906. The major losses were in Colorado, and these were only partially offset by gains in Nevada. In Arizona, Utah, and Idaho, the union was maintaining its strength, neither gaining nor losing much. Membership drops in Colorado from 1903 to 1905 included declines from 800 to 185 in Telluride, 530 to 134 in Cripple Creek, 508 to 202 in Ouray, and 280 to 113 in Cloud City (Leadville).2 The total number of locals in Colorado also declined in these years (see Appendix, Table 1).

The failure in Colorado convinced WFM leaders of one thing: the great struggle against giant corporations required a union of all working-class people, a role not even close to being filled by the American Labor Union. This union had picked up some affiliates but had not been successful in reaching the East or competing with the AFL, and it did not seem to have the potential to become a truly national organization. To accomplish this objective, the WFM took up leadership in a movement that led to the creation of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

Gathered together at the founding convention of the IWW in Chicago during June and July 1905 was a familiar set of prominent radicals, including Bill Haywood, the black-bearded Father Thomas Hagerty, David Coates, Emma Langdon (who after Cripple Creek had moved to Denver, where she organized for the Socialist party), Guy E. Miller, Albert Ryan (from Jerome, Arizona), Mother Jones, Lucy Parsons (widow of one of the martyrs killed in the Haymarket riot), and Algie Simons, editor of the International Socialist Review. Eugene Debs and Daniel De Leon also attended, although the Socialist party and the Socialist Labor party (SLP) were not formally represented. De Leon brought several delegates from the party’s trade union wing, the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance.

WFM secretary-treasurer and Socialist William D. Haywood opened the first IWW convention in Chicago on June 27 by announcing: “This is the Continental Congress of the working class. We are here to confederate the workers of this country into a working class movement that shall have for its purpose the emancipation of the working class from the slave bondage of capitalism.”3 Haywood warned, “When the corporations and the capitalists understand that you are organized for the express purpose of placing the supervision of industry in the hands of those who do the work, you are going to be harassed and you are going to be subjected to every indignity and cruelty that their minds can invent.”4 Later in the proceedings, Algie Simons also warned that the effort to overthrow plutocracy meant that “all the cohorts of hell and capitalism” and the “powers of a prostituted press” would be used against them.5

Members of the new organization left Chicago with a show of unity, but the alliance they had forged was fragile. As with the Socialist party, within the IWW differences existed over the basic approach the union should take. Some, particularly those affiliated with the Socialist party and the SLP, saw value in an organization that heavily emphasized political activity. If he had his way, De Leon would have made the IWW an arm of the SLP. Debs and others with the Socialist party had different ideas as to with which party the new organization should be affiliated. A large number of delegates wanted the new organization to have nothing at all to do with political parties or elections. Many WFM members, fresh from bloody labor wars in which state and federal officials had lined up with employers, had concluded that trying to influence elections was a waste of time, that governors such as Waite were rare exceptions.6 Speaking for this group at the founding convention, Father Hagerty declared, “The ballot box is simply a capitalist concession. Dropping pieces of paper into a hole in a box never did achieve emancipation for the working class, and to my thinking it never will achieve it.”7 Those opposed to political action favored direct attacks on employers at the point of production. At the end of the debate, as historian Melvin Dubofsky has noted, “[I]t would have taken an expert on medieval theology to define the IWW’s position on political action.”8 The lack of a clear position on the issue was useful in that it kept both the political and anti-political (direct action) groups in the organization for the time being.

The organization began life by focusing on bread-and-butter labor issues in an effort to take over AFL affiliates. At the IWW’s second convention in 1906, however, an insurgent faction led by De Leon, William E. Trautmann of the AFL brewers’ union, and Vincent St. John took control of the organization. Those opposing this move, including the WFM delegates and many members of the Socialist party, withdrew from the convention en masse. With these groups gone, the IWW became a mix of De Leon’s SLP and a group of unskilled and semiskilled workers largely from the West. Many of those in the second group were American-born migratory laborers who, deprived of the vote, had no interest in political action. A split over political versus direct action led to the expulsion of De Leon’s political action Socialists two years later.

By 1906–1907 the radical movement was badly splintered. The WFM and IWW were becoming bitter enemies, differing in philosophy and competing for influence in mining camps. The IWW was unacceptable to the right-wingers who controlled the Socialist party nationally and in several Mountain West states. In return, Wobbly leaders contended in criticizing the right wing: “Socialism is not a bit of sentimentality. It is not a political nostrum compounded of equal parts of sighs and yearnings, brotherly love, golden rule, municipal ownership and an accidental vote. It is an economic system and requires an economic organization, educated and disciplined, as the primary force for its achievement.”9 Further fracturing the movement, the WFM, perhaps largely for strategic reasons, distanced itself from the Socialist party. In 1906, for example, a special WFM committee went to considerable lengths to make the point that the organization’s mission was purely economic and one being pursued “without affiliation with any political party.”10 For all of this, the WFM continued to be left-leaning.

During the years 1905–1908 the WFM and the IWW were the principle noise-making unions in the region and stood out nationally in the eyes of many in their commitment to radicalism. Also attracting national attention were sensational events involving Bill Haywood—his arrest on a murder charge, his bid for office while in jail, his sensational trial—and labor disturbances in Nevada, Montana, and Arizona, all of which had implications for both the radical labor and Socialist party movements.

Speaking at the first IWW convention, Bill Haywood declared with considerable pride, “The capitalist class of this country fear[s] the Western Federation of Miners more than they do all the rest of the labor organizations in this country.”11 For many, confirmation of this point came on February 17, 1906, when Pinkerton agents, armed with extradition papers, arrested WFM officers Haywood and Charles H. Moyer and WFM business agent George A. Pettibone in Denver near WFM headquarters and rushed them by a special nonstop train—which radicals later called the “Kidnapper’s Special”—to Boise, Idaho, to stand trial for the murder of former Idaho governor Frank Steunenberg. Steunenberg had been killed in Caldwell, Idaho, the previous December when he was blown apart by a bomb attached to his gatepost. There had been much bitterness among miners over his actions during the Coeur d’Alene strike in 1899, and, following the murder, attention immediately turned to the miners’ union. Idaho authorities took action following the arrest of a drifter named Harry Orchard, who claimed the WFM officials were behind the murder. Ultimately, however, the effort to convict the officials failed, in part because the prosecution could not find anyone to corroborate Orchard’s account.

Adding insult to injury, the three unconvicted prisoners spent much of the twenty-seven hours it took to make the journey from Denver to Boise (actually a record time) in a Pullman car.12 Idaho officials initially put them on death row in the state penitentiary in the hope that conditions there would prompt at least one of them to crack. Later they were sent to a jail facility in Caldwell and then to the Ada County Jail in Boise. In March 1906 the defense was granted a change of venue for the trial from Caldwell, where Steunenberg had lived, to Boise. Meanwhile, the arrest, imprisonment, and pending trial of Haywood and the others riveted the attention of labor and Socialist leaders. Typical of the reaction from the left was a resolution put together by radicals in Goldfield, Nevada, that charged: “The outrageously conducted arrests and subsequent villainous persecution of the officers of the Western Federation of Miners are clearly parts of a subtle and deep-laid conspiracy, darkly concocted among the capitalistic vermin that infests the states of Idaho and Colorado and lays an immoral claim to the natural resources of these states, to destroy and disrupt the W.F.M., an organization which has proved itself an effective check to the rapacious greed of the exploiters of labor.”13

From the left’s perspective, the arrests were nothing more than a murderous conspiracy by the capitalistic class intended to destroy a strong labor union by brutal and illegal methods. An editorial in the International Socialist Review contended, “There is no question to-day but that capitalism is in the saddle and the fate of the three men in Idaho depends entirely upon whether those in control of the capitalist machinery of government decide that they will be less dangerous if dead than alive.”14 The root of the problem, suggested the review’s editor, Algie Simons, on another occasion, was that the WFM, blessed with “a breadth of character and depth of outlook unknown to the average eastern trade union,” had “recognized the truth of the socialist philosophy, and urged those truths upon their membership. This was the culminating crime that loosed all the bloodhounds of capitalism upon their track.”15 While absolving the WFM of responsibility for the murder, Simons conceded, as a way of illustrating Steunenberg’s sins in Coeur d’Alene, “It may be possible that some man who had been brutally beaten or bayoneted by the bestialized Negro soldiery at that time, whose home was destroyed, or wife insulted, or who saw his comrades shot down like dogs because they had dared to be men, might have revenged himself upon the man who directed the conduct of these outrages.”16

In Idaho the mainstream press charged that followers of Socialism, now displaying their outrage over the arrests, were simply the cat’s paw of the WFM, which “stands for anarchy, pure and simple” and is “an outlaw organization of foreign laborers that has for its argument the one word, dynamite.”17 President Theodore Roosevelt joined in by referring to Haywood and Moyer as “undesirable citizens.” This comment, the president later contended, was not intended to influence their trial; he had no opinion as to their guilt. At the same time, the president was of the opinion that the two individuals “stand as the representatives of those men who by their public utterances and manifestoes, by the utterances of the papers they control or inspire, and by the words and deeds of those associated with or subordinated to them, habitually appear as guilty of incitement to or apology for bloodshed and violence. If this does not constitute undesirable citizenship, then there can never be any undesirable citizens.”18

Haywood’s kidnapping, arrest, and pending trial were central themes of radical election activity in 1906. This was especially true in Colorado and Idaho. In the former, the Socialist party came up with an unusual form of protest. Coming to the floor of the Colorado party’s convention in Denver on July 4, 1906, Secretary J. W. Martin made what to many was a startling announcement regarding the party’s gubernatorial nomination:

I do not rise to name a well-groomed business man nor a professional politician seeking graft. Nor do I name a labor leader who is dined and wined at Civic Federation banquets, or who hobnobs with Grover Cleveland, August Belmont or Theodore Roosevelt. But I rise to name a man who in executive ability is the peer of the best, and whose personal integrity is without stain. A man whose hands have been calloused by honest labor, and whose every heart throb is in sympathy with those who toil. A man who has never been praised by the capitalist press as “the greatest labor leader” in the world; but who, as a labor leader[,] has never betrayed his trust nor sold out a strike. A man who because of his loyalty to the working class has been struck down by a brutal soldiery on the streets of our city. And who, for that same loyalty was kidnapped by the command of the powers of capitalism and contrary to all legal forms and observances was carried to a distant state and thrown into a felon’s cell, where for months he and his faithful comrades have waited, demanding in vain the speedy trial guaranteed to every citizen by our constitution and laws—Wm. D. Haywood, the prisoner in Caldwell jail.19

Later in his speech Martin noted with pleasure that “Haywood is not only hated, but feared by the capitalist class.”20

At the time of his nomination, Haywood was in jail awaiting trial. His nomination by Colorado Socialists generated considerable comment, favorable and unfavorable, both inside and outside the state. An editorial in the left-wing International Socialist Review noted, “In nominating Comrade Haywood for governor, the socialists of Colorado have done one of those splendid things that sound the bugle call for action.”21 Milwaukee Socialists, on the other hand, protested the sending of campaign aid to Colorado, where they described the situation as “picturesque but unsubstantial.”22 Outside the movement, the less-than-friendly Caldwell News noted that, as a practical matter, Haywood’s nomination was of little importance: “Even Colorado, with all its turbulent mining camp politics, is not in the least likely to elect as Governor a man who might be hanging from the gallows before he could take office.”23

Socialists and labor leaders from around the country, contrary to the sentiment expressed by Milwaukee Socialists, joined the Colorado party in an effort to produce a large vote for Haywood as a way of protesting the trial, which they felt was part of a broader war on the WFM. A campaign fund of around $5,000 was raised, and three national organizers were sent to Colorado during the campaign.24 Socialist insiders saw little possibility of a Haywood victory—the level of Socialist support, principally in Denver and a few mining camps, was not strong enough to give him a fighting chance—but noted that “the fight which is being put up is serving to attract attention and to educate the workers as never before.”25 Campaigning around Colorado, Guy E. Miller, the party’s candidate for congressman at large, contended that the loud protest from the Socialists had already prevented a speedy verdict of death.26

Joining the Haywood campaign, Debs intoned, “Comrades of Colorado, the eyes of the century are upon you, and we know that you will do your duty and that the banner you have placed in Haywood’s hands will be emblazoned with victory.”27 Another national figure, Ernest Untermann, noted more negatively that the working people of Colorado had the unfortunate habit of electing their worst enemies: “The question is: How long will the working people of Colorado try to reap figs from thistles? How long will they deliver themselves gagged and bound to the corporations? How long will they vote for injunctions, militia raids, kidnapping expeditions, deportations, murder plots and dynamite explosions?”28

In his acceptance speech, sent from the Ada County Jail, Boise, Idaho, on July 14, 1906, Haywood pulled few punches, seemingly refusing to adjust his views because of his upcoming trial. He declared: “The Socialist platform is the corner stone of industrial liberty. The program is clean, clear-cut, uncompromising. Principles cannot be arbitrated. Let the campaign slogan be, ‘There is nothing to arbitrate.’ The class struggle must go on as long as one eats the bread in the sweat of another man’s face.”29 Haywood later gained fame as a direct actionist of the first order. In the 1906 campaign, however, he saw the value of political action. The candidate said: “The economic power of organized labor is determined by united political action. To win demands made on the industrial level, it is absolutely necessary to control the branches of government, as past experience shows every strike to have been lost through the interference of courts and militia.”30 Over the next few months Haywood personally directed his campaign from his prison cell, staying in touch with speakers working on his behalf and dictating the positions articulated. One reporter noted, “Haywood has waged a practical battle, along practical lines, for the accomplishment of practical results.”31 From July to October 1906 the campaign led to the addition of fifty Socialist locals in Colorado and an increase in the number of subscriptions to Appeal to Reason in the state, from 5,000 to 15,000.32

During the campaign, left-wing party leaders made it clear that they were in control; while the party offered immediate relief to workers in their struggle against mine owners, “it does so with the distinct understanding that it will stop short of nothing but the complete overthrow of the capitalistic system and the establishment of the cooperative commonwealth.”33 In promoting the party platform, leaders also reminded workers that every vote cast for the Socialists would help, even if the party fell short of capturing offices: “A large vote for the Socialist party, even though we should fail to elect our candidates, will compel the respect of the capitalist class, and secure concessions to the workers which they can never secure by voting the Democratic, Republican and Municipal Ownership tickets.”34

Socialists working in Colorado in the fall of 1906 appeared to enjoy themselves, although they frequently ran afoul of the law. Around sixty were arrested while campaigning on the streets. The unlucky A. H. Floaten was arrested in Fort Collins, Colorado, for riding his bicycle on the sidewalk while distributing Haywood-Moyer leaflets. In some places Socialists felt compelled to organize in secret and to conduct agitations by stealth.35 On the electoral level, all of this produced around 16,000 votes for Haywood—an improvement over the 4,000 votes the party had received two years earlier but hardly enough to make a dent in the race. Reformer Ben Lindsey, an anti-corporate candidate of the Independent Republicans, received 18,000 votes, finishing ahead of Haywood. The winner, Republican Henry Buchtel, received close to 93,000 votes.36

At the time of Haywood’s arrest, the Idaho party was in poor shape. Statewide membership dropped from an average of 364 in 1904 to an average of 261 in 1905. State Secretary T. J. Coonrod wrote in early 1906, “Under the circumstances, with a state-organizer in the field a great part of the year, such a decrease is positively criminal . . . it is up to the membership to do a little housecleaning and see that the work is done properly.”37 Factionalism and a tendency to engage in personal revenge had also gotten in the way of party building. In one 1905 episode the Boise local brought charges against A. G. Miller that caused his suspension from the office of state organizer, but Miller was cleared of the charges by the state committee and, turning on his accusers, got the committee to revoke the charter of Local Boise and to bounce a fellow named Carter out of his national committeeman position. Only 89 party members of an estimated 300 bothered to vote to fill the vacant national committeeman position. In this election E. J. Riggs received 61 votes, defeating Vincent St. John (running as J. W. Vincent).38

Early in 1906, party officials in the Coeur d’Alene area boasted of large increases in party membership.39 In August the state secretary proclaimed: “Socialism in Idaho is going to reach the high-water mark this fall. Truth to tell, it is going to slop over the banks and spread out all over the state.”40 The Idaho Socialist party directly benefited in 1906 because the pending Haywood trial (he was to be tried first) had attracted several Socialist agitators, who lectured all over the state, and prompted Herman Titus to move his left-wing paper, The Socialist, to Caldwell from Toledo, Ohio, to give the workers’ side of the story. Titus, born in Massachusetts, had been a Baptist minister for several years but resigned from the ministry, contending that the church had abandoned Jesus. He became a medical doctor, first in Newton, Massachusetts, and later in Seattle. Titus offered his paper’s services in getting Idaho Socialists elected in 1906, declaring that because of the Haywood trial and the obvious failure of the Republican and Democratic parties on the matter, “the Socialist Party in Idaho faces the greatest opportunity ever offered a workingman’s party in any state.”41 Titus, however, was a “by-the-book” Socialist and was angered by the apparent effort of the defense team and those going on trial to align Socialists with Democratic voters to defeat tough-minded Republican judge Frank J. Smith, who was scheduled to preside over the proceedings involving Haywood and the others. Titus later reported, “Comrade Moyer said to me, ‘If your neck was in the noose, you would talk different.’”42

According to operative reports, around 400 people showed up in April 1906 to hear Dr. Titus speak on the subject of “Who Killed Steunenberg.”43 Titus had no doubt that Orchard was the murderer. As for motive: “My theory is, and I am an experienced physician of long years practice, that Orchard is a moral degenerate. His head shows it. Most men’s two sides are alike, Orchard’s are not. He was born a degenerate and cannot help it. He has a mania for killing people with explosives.”44 According to operatives in attendance, Titus’s lengthy remarks, in which he linked Orchard’s guilt to the fact that one of his ears was much higher than the other, made less of an impact with the audience than did David C. Coates, the chair of the meeting and the first speaker. Coates talked for an hour, roasting the Mine Owners’ Association, saying that Governor Frank Gooding was their tool and that they were trying to break up the WFM. The operative noted, “Coates was frequently interrupted by applause. He was more radical than Titus and the audience applauded him more freely.”45

The Idaho party, holding its 1906 convention on July 4 at Caldwell, nominated a card-carrying union man, Thomas F. Kelly, for governor and made the treatment of the WFM officials currently held in the Caldwell jail a major issue.46 Kelly, a stonecutter, drew large and enthusiastic audiences in the Coeur d’Alene mining camps during the campaign.47 Miners, however, were divided over whether to take their leaders’ advice and vote for the Socialist or to support the Democrat in their effort to oust Republican governor Frank Gooding, who had alienated much of the labor movement with his hard-line stance on the arrest and trial of Haywood, Moyer, and Pettibone—he had been quoted as asserting the three prisoners’ guilt. Socialist party leaders in Idaho in 1906 acknowledged what those on the left could agree on—that the Republicans were a bad lot—but had a harder time promoting the theme adopted at their convention earlier in the year that “Democrats are only Republicans out of office.”48

In 1906 party leaders in Shoshone County rejected Democratic leaders’ offers to fuse with the Democrats in a joint effort to defeat the Republican party ticket, which was backed by the Mine Owners’ Association. Like Socialists elsewhere, Idaho Socialist leaders cited the Populists’ sad experience with fusion in 1896 as a reason for remaining independent. As the election neared, mining companies began to fire miners in the area who expressed support for the Democratic or Socialist parties and let it be known that more firings might take place after the election. Election board officials, it was rumored, would be more than willing to tell mining companies how individuals had voted if the Republicans failed to win.49 Given the hostility of the mining companies, much of the activity of Socialists in the county took place off mining property. Two left-wing self-employed barbers, William Stache and David Pifer, who ran shops in Wallace, emerged as leaders of the local party in Shoshone County.50 Undercover detectives working for the mining companies warned that Pifer in particular was a dangerous radical, very near an anarchist, who agitated at every possible chance. His shop, they reported, was “a bad hangout.”51

Numerous Socialist speakers came to the Coeur d’Alene area in 1906, and Socialism was a regular topic at union meetings. In Wallace, however, some of the speakers experienced official harassment. The local sheriff, for example, ordered the street lights to be turned off in the middle of a street-corner speech by organizer Ida Crouch Hazlett—an event she later remarked upon with considerable venom before 150 people in the miners’ hall.52 The sheriff did the same thing to national organizer George H. Goebel of New Jersey, who, being prepared, proceeded to address a large crowd by torchlight.53 Goebel, one of the organizers sent in by the national party, worked the northern end of Idaho—including the Coeur d’Alene, Wallace, and Wardner districts—and close to thirty towns in the four counties (Kootenai, Shoshone, Latah, and Nez Perce) where about half of the Socialist vote in the state had been cast in 1904. Montana secretary James Graham also sent Hazlett and other speakers to help out in this area.

In spite of all this activity and the excitement brought about by the Haywood trial, the Socialist Kelly fared poorly in his campaign for governor. Organized labor backed Gooding’s Democratic opponent as the candidate most likely to turn the incumbent out of office. Many workers also appeared to have done so. Even so, Gooding emerged the winner. The top Socialist vote getter in 1906, the candidate for mine inspector, received only 7 percent of the statewide vote, 13 percent in Shoshone, and 21 percent in Burke.54 On the positive side, in a victory for political action, Frank J. Smith, the tough Republican judge scheduled to hear the Haywood case, was turned out of office, defeated by a Democrat, Edgar L. Bryan, who appeared to have had considerable support from WFM members and Socialists. Bryan, though, had a conflict of interest and was replaced by Judge Fremont Wood as judge in the Haywood trial. Wood, age fifty, was a Republican but was generally regarded by both sides as fair-mined.55

Haywood’s trial began a few months after the 1906 election. The radical press showed up, vowing to make sure the trial was a fair one.56 Not surprisingly, radical reporters were not always received with open arms. The Socialist press reported that several of these journalists, including Ida Crouch Hazlett, now with the Montana News, “have been spat upon in the streets and hissed [at].” Others had trouble getting lodging, had their mail tampered with, and had to put up a fight to get into the courthouse where the trial was held.57 Socialists also complained that prison authorities gave the regular press the right to interview Harry Orchard in his cell but denied that right to reporters for left-wing newspapers.

In the end, the jury came down on the side of Haywood. The editor of the conservative Caldwell Tribune gave considerable credit to the eloquence of Haywood’s attorney, Clarence Darrow, who, the editor felt, captivated the jury. Darrow, in defending the WFM, had successfully put Steunenberg on trial for calling out the troops and the state on trial for excessive spending on Pinkerton services.58 The editor concluded, though, “When The Tribune states that the people of Canyon county were disappointed in the recent decision in the Haywood case, the statement is drawing it mild, never were the people more disappointed.”59 On the other hand, a newspaper in Goldfield, Nevada, reported that around 1,500 miners celebrated the acquittal with speeches and a parade. One speaker cried, “What’s the matter with undesirable citizens?” Another asked, “What shall we do to Roosevelt?”60 Later, Pettibone was acquitted and charges against Moyer were dismissed. Bill Haywood, meanwhile, fresh from jail, made personal appearances around the region. One report from Idaho Falls stated: “The demonstration that met the Haywood train was a marvel. The machinists had the band out, and 5,000 people thronged the streets. It was a wonder where they all came from. Haywood was dragged from the car with Henrietta, the youngest girl, and mounted on a trunk where he made an inspiring speech of a few minutes’ length. The coach was filled with flowers taken in to Mrs. Haywood.”61

Even the most alienated and bitter radicals were forced to admit that the outcome of the trial could possibly be taken as evidence that the “system” was not entirely corrupt. Radicals had been greatly worried about whether Haywood could get a fair trial, especially considering where the trial was located. One radical had warned, “If you wanted to take a labor agitator to a place where you could murder him without local protest, no better spot in the country could be found than this region of Southern Idaho.”62 The verdict apparently came as a genuine surprise to Haywood and most of the radicals who had gathered in Idaho. A radical paper admitted that “everyone had guessed wrong” in sizing up the jury.63 A headline in an IWW paper read “Haywood Acquitted by Honest Jury,” leaving the impression that an “honest jury” was as newsworthy as the acquittal itself. The story also credited the judge as fair-minded.64 Other radicals considered the verdict as evidence that Haywood had “been innocent to a sickening degree.”65

Overall, though, the dominant theme in the radical press was that the working class, against all odds, had won an enormous victory and was eagerly looking forward to the next conflict. As a writer for the Socialist Wilshire’s magazine proclaimed:

We are mightily cheered and invigorated, we feel the power of the united millions of workingmen, we gird up our loins and joyously await the next conflict with baffled capitalism. We did not know our strength and our resources before the Idaho battle. Neither did the enemy. A draw seemed the best thing we could hope for in view of the complete capitalistic machinery that opposed us. They had unlimited wealth, the courts and the laws, a legion of spies and thugs, the newspapers, a poisoned local atmosphere, the approval of presidents, governors and all respectable people, yet they were unable to win. They tried to teach labor a lesson of terror, but they only succeeded in exposing the rottenness of the ruling class and in emboldening the nation’s toilers to march on to final victory.66

The writer also ventured the belief that Haywood knew the Socialist party had stood behind him and would never forget his debt to that organization. In fact, while Haywood might not have forgotten, his relations with the Socialist party went rapidly downhill.

Other observers saw the arrest and trial as promoting class consciousness among trade unionists throughout the country.67 Yet, while the trial stimulated a great deal of Socialist party activity, such as rallies to raise funds and arouse sympathy for the prisoners, the impact of this on votes for Socialist candidates was difficult to decipher. If nothing else, the trial may have provided the benefit of informing the public about, as the radicals saw it, the brutality of the class struggle and the “criminal career” of mine owners.68 On the negative side, however, the trial had also produced a great deal of press coverage of the WFM and the IWW, which helped paint their members in the public eye as bloody revolutionaries. The episode also added to the tension within the WFM and the IWW, making some, such as Haywood, even more determined to overthrow the system through direct action and others, like Moyer, to tone down the revolutionary rhetoric and build more respectable unions.69

While the IWW and Haywood were making national news, the Socialist party in Nevada was starting to take root in the WFM and IWW locals found in mining areas. In 1906 the Nevada party’s slate of state candidates consisted almost entirely of flaming revolutionaries who were IWW members. Harry Jardine, the party’s candidate for Congress, fit that description. Making “the ownership of your own job” his central theme, he picked up about 9 percent of the votes cast—1,250 out of 14,000.70 Goldfield, a booming mining camp of around 15,000 people in Esmeralda County (there were only 70,000 people in the state), was a particularly strong hotbed of radical activity. Socialists met at Goldfield for their first state party convention in 1906. The IWW, under the leadership of Vincent St. John, organized Goldfield from top to bottom in 1906–1907. Eager to replace the traditional craft unionism in the city with the IWW’s idea of an industrial union, St. John began by organizing nearly all the “town workers”—dishwashers, engineers, stenographers, teamsters, and clerks—into a single IWW local. Later, the IWW took over and proceeded to dominate the WFM’s Goldfield Local Union No. 220—at the time, the WFM existed nationally as the mining department of the IWW.

St. John boasted about labor’s dominance over the town: “No committees were ever sent to any employers. The union adopted wage scales and regulated hours. The secretary posted the same on a bulletin board outside the union hall, and it was the LAW. The employers were forced to come and see the union committees.”71 Goldfield’s IWW, on January 20, 1907, put on a radical display with a “Bloody Sunday” parade that both commemorated the massacre that followed the failed Russian Revolution of 1905 and protested the trial of Haywood in Idaho. Following the parade came a series of fiery speeches by St. John and others condemning capitalists in Nevada and in general. St. John promised, “We will sweep the capitalist class out of the life of this nation and then out of the whole world.”72

The capitalists struck back, led by the mine owners. In the forefront was George Wingfield who, along with George S. Nixon, a U.S. senator from Nevada, headed the Goldfield Consolidated Mines Company, which had opened operations in 1906.73 As in Colorado and Idaho, the mine owners pulled together in a Mine Owners’ Association, formed alliances with state politicians, and ultimately were able to use troops to destroy the unions. Nevada also had its own Haywood trial. This involved union members and Socialists Morrie Preston and Joseph Smith who, in 1907, were accused and later convicted, on the basis of highly questionable evidence, of killing a restaurant owner during labor trouble. Mine owners tried to use the trial to convince the public that the unions represented a violent movement and should be eliminated.74

A little more than six months after the Preston-Smith trial, federal troops moved into Goldfield to put down a mining strike. In the mines the ostensible issues revolved around the owners’ efforts to crack down on high grading, which had become a standard practice among miners of taking rich ore out of the mines for their own use. Miners “regarded stealing ore as a fringe benefit to which they were morally entitled” and resented the company’s installation of change rooms to curb the practice.75 Miners also became unhappy over being forced to accept scrip rather than cash because of a cash shortage following the October 1907 bank panic. Mine owners, intent on driving Socialists and radical labor out of the camp, refused to bargain with the Goldfield Miners’ Union, closed down operations, and, on November 30, declared that the mines would remain closed until labor conditions could be settled to their satisfaction.

Soon thereafter, Governor John Sparks, acting on behalf of the mine owners, asked President Theodore Roosevelt to send troops into the area. Roosevelt did so on December 6. A contemporary nonradical observer noted: “There is talk of trouble, and a call for help is sent to the Governor. He sends in the United States regulars, who make camp over on the hill near us. They help the stores, saloons, and amusement places, and, as there is no trouble to quiet, have an easy time of it, skating at the rink, and getting drunk. But they were never arrogant with the miners, and I think they realized that having been ordered there was a mistake. Some of them did do a good turn by stealing provisions from the Government and selling them cheaply to the miners.”76

Ultimately, though, the miners got the short end of the stick. With federal troops present as security against disorder, the mine owners announced they would reopen the mines on December 12 but that wages would be reduced and workers who wished to keep their jobs would have to sign an anti-union pledge card. When the mines reopened, very few miners reported for work, as most stood with the WFM, and owners were forced to begin recruitment drives in neighboring states. Reporting from Goldfield in January 1908 as a special correspondent for The Socialist, Ida Crouch Hazlett found everything was quiet. Lots of soldiers were living in comfortable quarters in a hotel, around sixty scabs were at work for Consolidated, and its vice president, George Wingfield, was in Salt Lake City trying to recruit more scabs.77 Expressing her anger, Hazlett also reported: “Everything points to the fact that Governor Sparks was paid $50,000 for getting the troops in here. He is nothing but a drunken sot, as tough and disreputable as they make them, and nothing else could be expected.”78

The record indicates that the governor had assured Roosevelt that violence in the camp justified the sending of troops. Roosevelt, however, later became suspicious that this was not the case—people in Goldfield seemed surprised to see the troops and wondered why they were there—and sent a commission to investigate conditions. The commission found that the sending of troops had not been warranted, indeed, that it had been requested for the sole purpose of helping mine owners get rid of a troublesome union. The president, in response, said the troops would have to be withdrawn, but the governor continued to insist that the situation in Goldfield was dangerous and blamed the lawless and anarchistic WFM for the turmoil. At the governor’s request, the legislature passed a resolution asking that federal troops be kept in the area until the state had time to create its own military force.

The legislature proceeded to pass a bill that, as radicals saw it, brought “into being an irresponsible body of armed men”—in effect, “a body of legal thugs”—for the governor to use to club wage earners into submission.79 The legislation, known as the State Police Bill, gave the governor control over an active police force of 31 men and a reserve force of 250 men, which he could use as he deemed appropriate. Radicals warned, “[I]n the control of such a man as Sparks has shown himself to be, this armed force of legalized guerillas can only become a weapon of revenge and oppression.”80 In February 1908, Nevada state police began replacing federal troops in Goldfield. Feeling secure, mine operators posted regulations at each mine declaring that they would not recognize unions and that no union representatives were allowed on the premises.81

The effect of all this was to eliminate the WFM and the IWW from the camp. Many miners left the area. Many who stayed dropped out of the unions. The few who continued as union members voted to end the strike on April 3, 1908. While the strike had not been accompanied by anything close to the level of violence that had characterized disturbances in Cripple Creek, when a settlement came, union labor at Goldfield was as thoroughly defeated as it had been at the Colorado camp.82 With the defeat, the base of Socialist movement in Nevada moved north to the Reno area and toward a more moderate tone. For the IWW, the experience in Goldfield encouraged its members to think about concentrating more of their efforts on the more civilized and industrially developed eastern part of the country.

In December 1907 WFM president Moyer took note of troops going into Goldfield in stressing the need for independent political as well as industrial action—troop movement, he argued, would not have happened if labor had had a friend in Nevada’s office of governor.83 However, he was not anxious to write off working with direct actionists in the IWW. He went on record as saying that the WFM still believed in the principles of industrial unionism and was looking forward to the IWW conference in Chicago in hopes that the IWW could be reestablished “and emerge from its present state of disruption and uncertainty.”84

Meanwhile, things were not going smoothly for the WFM. It faced an uphill struggle in several other places in addition to Nevada. Organizers, showing their frustration, put much of the blame for failure on the workers, although not forgetting to condemn the activities of employers and churches as well. Reporting from Leadville in April 1906, for example, Marion W. Moor wrote: “The chief obstacle to the organization of the English-speaking people of Leadville is their ignorance and cowardice. They are in constant fear of their jobs, though I found after careful investigation that not one man had been discharged in the past year on account of his membership in the union. A strong influence was brought to bear by the church on the Austrians, Italians, and other Latin races to refuse to join the union, and we have ample proof that the employers of Leadville gave a priest in the camp the sum of $2,000 for this purpose.”85

At the time, relations between WFM officials and the conservative, if not corporate-dominated, Butte Miners’ Union were strained, with Socialism part of the issue; many in the Butte union felt the national organization had ventured too far to the left. Leaders of the Butte union were also being challenged by Wobblies who, working from within, were attempting to develop an anti-company, pro-Socialist left wing. The decision of union leaders in 1906 to accept Amalgamated’s offer of a token raise played into the hands of Wobblies and so greatly angered many rank-and-file union members that they threatened to go on strike, claiming the leaders had sold out to management. The company stymied this development by suspending all mine operations. In no time at all the entire move for a strike collapsed, and the company’s men retained control of the union.

While the Wobblies and the WFM and, with them, the core of the Socialist party were being squashed in Nevada, the WFM, aided by Socialists, was spending considerable energy in Arizona in an effort to organize miners in Bisbee at the southern end of the state. A central target was the Copper Queen Consolidated Mining Company, owned by the Phelps-Dodge Company. Organizers were particularly upset with the intransigence of the company’s local managers. One reported in 1906 that while Phelps-Dodge, “with offices in John street, New York, apparently does not care whether its mines are operated by union or non-union labor so long as dividends are forthcoming, there is a bunch of Copper Queen officials in Bisbee who imagine that every vice and iniquity in the universe emanates from the Socialist party and the Western Federation of Miners.”86 The chief obstacle to organization, however, was simply that Copper Queen had played it smart—it had paid its employees the union wage and strictly complied with the eight-hour law.87 The company was also not above firing anyone suspected of favoring a union and did so in 1906 without hesitation.

The company was also openly hostile to Socialists. Still, the Bisbee local had some success in attracting miners to its meetings. In the spring of 1906, for example, it proudly reported it had held a successful “indignation meeting” out of which it raised funds for the Moyer-Haywood-Pettibone defense fund. The Socialists reported that they were surprised by the size of the turnout because “any one working for the ‘good Copper Queen Company’ will be discharged for even speaking to a Socialist on the street, let alone going to a Socialist meeting. But there are times when the wage workers throw all caution to the winds and express themselves openly and this was one of them.”88 The report concluded, “The meeting was a demonstration of the fact that the Copper Queen had not succeeded in driving all the union men out of Bisbee and also that the recent struggle here over the question of unionism instead of killing it, has kindled the spark until now it is liable to burst into flame at any moment, and when the next question comes up the issue will terminate successfully.”89 In 1906, however, the Bisbee miners voted against organization. That same year the Arizona Socialist party nominated Joseph D. Cannon, who had led the unsuccessful fight to organize Bisbee miners, as their candidate for delegate to Congress. With Cannon, the Socialist vote increased from 1,304 in 1904 to 2,078 in 1906, about 9 percent of the vote. Socialist candidates did best in places where miners were relatively numerous.90

The following year the Bisbee miners organized and struck for higher wages, but the strike failed. Reporting to the WFM convention in 1907, Cannon said the company would fire WFM members as fast as Cannon could recruit them. The union, he went on, constantly met the opposition of newspapers, tangled with Pinkerton spies, and ran the risk of violence. Cannon told the assembly, “It is a pretty hard proposition to be a union man when your life is at stake, when your job is at stake, and when your family is at stake.”91 Another delegate, P. C. Rawlings from the new Bisbee local, though, added with pride, “The words ‘Western Federation of Miners’ in Bisbee is a bugaboo that haunts the dreams of the corporate managers of that place.”92

Following the 1907 conflicts in Bisbee and elsewhere in Arizona, employers launched what a leading labor official called “a ruthless campaign of blacklisting” against the workers who had participated in the strikes.93 In Bisbee, Morenci, and other camps, prospective workers were required to give detailed histories of their lives, in some cases of their families, as a precondition of employment. The end result of blacklisting was that miners who had joined the WFM were often forced to move from camp to camp to secure employment. A labor official described the process thus: “A union man would secure a few days’ work, attend a union meeting and a detective would report him, with the result [that] he would soon be on the tramp again.”94

Organized labor and the Socialist movement may have been growing hand in hand on a national basis, but the various unions and political elements within the radical movement in the Mountain West in the years 1905–1908 were, at best, in a fragile alliance, and progress on both the industrial and political fronts in terms of union organization and winning votes was limited. The kidnapping and trial of WFM officials provided a rallying point. Radicals were one in calling attention to this outrage and in condemning what had happened. Cracks in the movement, however, were also apparent as the WFM backed away from both the Socialist party and the IWW, even though the latter was largely its own creation. Within the Socialist movement, midwestern and eastern Socialists were less than enthusiastic over the attention given to radicals like Haywood. While Socialists had a measure of success in using the arrests and trial of the WFM officials to build class consciousness and the ranks of radical organizations, this seemed not to have added appreciably to the votes for Socialist candidates. Haywood’s candidacy gave a boost to the Colorado party but not enough to result in anything close to victory, leaving some to ponder if there was any Socialist who could win an election. In Idaho, where the arrests and trial had spurred considerable Socialist activity, the attention of labor and many workers was focused on getting rid of a hostile Republican governor, and they rallied behind a Democratic candidate rather than the Socialist candidate as the best way to achieve that goal.

On the industrial front, as the Nevada events indicated, the federal and state governments continued to demonstrate a willingness to come down on the side of mine owners. Indeed, in 1906 the governor of Arizona went so far as to send troops, around 250 Arizona Rangers, into Mexico where they were sworn in by the governor of Sonora as Mexican volunteers and used to help put down a 1906 strike against the American-based Consolidated Copper Company. The crushed strike had been led by Mexican and American Wobblies and the WFM in protest over the low wages paid to Mexican workers. Corporate resistance in Montana was built around capturing the mining union, a less violent but equally effective tactic. Even with all this, however, there was considerable enthusiasm among radicals in the region as the nation approached the 1908 election.

Ida Crouch Hazlett, Socialist editor and organizer. Photograph courtesy of the World Museum of Mining. Copyright World Museum of Mining.

Joe Cannon, Arizona labor and Socialist leader. Courtesy Arizona State University Libraries.

A. Grant Miller, Nevada Socialist leader. Courtesy of Anne Ward.

Mayor Duncan of Butte. Photograph courtesy of the World Museum of Mining. Copyright World Museum of Mining.

W.C. Tharp, Socialist in New Mexico state legislature. Photo: Nerw Mexico Blue Book, 1915.

Ruins of Ludlow Colony, Trinidad, Colorado. Library of Congress.

Butte Miners Union Hall Riot. Photograph courtesy of the World Museum of Mining. Copyright World Museum of Mining.

Butte Miners Union Hall after blast. Photograph courtesy of the World Museum of Mining. Copyright World Museum of Mining.

Butte Court House during martial law period, 1914. Photograph courtesy of the World Museum of Mining. Copyright World Museum of Mining.

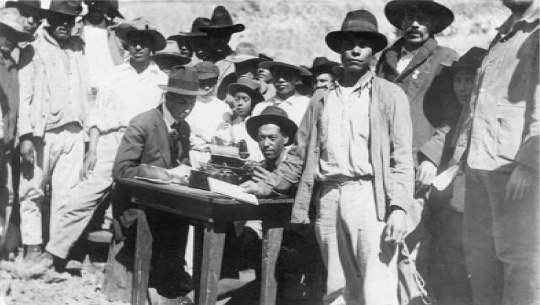

Taking Applications for Membership in the WFM, during strike in Morenci, Arizona, 1915-1916. Courtesy Henry S. McCluskey Photographs, Arizona Collection, Arizona State University Libraries.

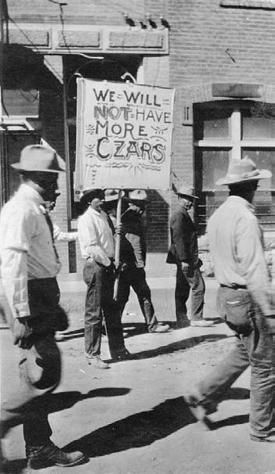

Picketing at Morenci during strike, 1915–1916. Courtesy Henry S. McCluskey Photographs, Arizona Collection, Arizona State University Libraries.

Picketing at Morenci during strike 1915–1916. Courtesy Henry S. McCluskey Photographs, Arizona Collection, Arizona State University Libraries.