LIKE QUEEQUEG’S HOMELAND of “Kokovoko” in Moby-Dick, Atlantis “is not drawn on any map”; nor will you find it in any compilation of Greek mythology. It is sui generis, an island unto itself, a chimeric place that takes whatever form its describer wishes to give it. It can be a great city that sank into the sea, or a continent that was destroyed by an errant asteroid. It can be a city in the Aegean, or an outpost in the Sahara Desert. It can be a submerged island in the North Atlantic, or a community high on the slopes of California’s Mount Shasta. It has appeared in historical studies, projections of the future, archaeological monographs, philosophical discourses, geological tracts, astronomical treatises, science fiction novels, sea stories, studies of ancient hieroglyphics, travel books, psychic revelations, poems, movies, and comic books, and there are countless crackpot explanations about what and where it really was.

As we shall see, some writers produced what was clearly fiction, but what are we to make of some of those who wrote about Atlantis a few years after Plato? In his treatise On Meteorology, Plato’s student Aristotle (384–322 B.C.) says that the sea outside the Pillars of Hercules is shallow because of mud, echoing his teacher’s description, but he also says that Atlantis does not exist. The philosopher Crantor, who lived somewhat later than Aristotle, wrote the first known commentary on Plato’s dialogues, in which he accepted the story of Atlantis without qualification. Pliny the Elder, describing the formation of the Atlantic, speaks of great formations of land being swept away “where the Atlantic Ocean is now—if we believe Plato.” By the time of Christ, Atlantis had taken its place as a quasi-official island somewhere beyond the Pillars of Hercules. Around 30 B.C., the Roman historian Diodorus Siculus completed his forty-volume World History, in which he discussed the battle between the Amazons and the Atlanteans, “who dwelt in a prosperous country and inhabited great cities.” (Of this battle, Ramage says, “For Diodorus … it is no longer a case of whether Atlantis ever existed or not, but of how to relate its inhabitants to the other mythological peoples that lived out here at the end of the world. Most of what Diodorus says has to be taken as sheer embroidery.”)

In his Life of Solon, written a century later, Plutarch gives the previously anonymous Egyptian priest of Saïs a name (Sonchis), and Solon is described as studying with him at Heliopolis. Plutarch writes, “He heard the story of the lost Atlantis, and tried to introduce it in a poetical form to the Greeks.” Later in Solon, Plutarch writes:

Plato, ambitious to elaborate and adorn the subject of the lost Atlantis, as if it were the soil of a fair state unoccupied, but appropriately his by virtue of some kinship with Solon, began the work by laying out great porches, enclosures, and courtyards, such as no story, tale or poesy ever had before. Therefore the greater our delight in what he actually wrote, the greater our distress in view of what he left undone. For as the Olympieium in the city of Athens, so the tale of lost Atlantis in the wisdom of Plato is the only one among many beautiful works to remain unfinished.

It appears from Plutarch’s description of Plato’s “lost Atlantis” story (or fable) that Plato had embellished the story told to him by Solon, fabricating those very elements (great porches, enclosures, courtyards) that make the story read more like fantasy than fact. Later on, Plutarch wrote, “Now Solon, after beginning his great work on the story or fable of the lost Atlantis, which, as he had heard from the learned men of Saïs, particularly concerned the Athenians, abandoned it, not for lack of leisure, as Plato says, but rather because of his old age, fearing the magnitude of the task.”

Some two hundred years after Christ, the Roman scholar Aelian (170–230 A.D.) wrote De natura animalium,* in which he discussed an animal called the “sea ram” (“which many have heard tell but few know the natural history”), said to be found in the straits between Corsica and Sardinia. “The head of the male sea ram,” wrote Aelian, “is bound with a white band, like the diadem, one might say, of Lysimachus or Antigonus or some other Macedonian king.… Dwellers by the ocean tell the story that the ancient kings of Atlantis who traced their descent from Poseidon, wore head-bands of the skin of male sea rams, as a sign of authority. The queens likewise wore fillets of the female sea ram.…” Aelian also supplied Theopompus’s description of the vast continent, “beyond the boundary of this world … with huge animals and men twice the stature of ours.” (Other than Aelian’s transcript, all of Theopompus’s works have been lost.) Of this story, Aelian wrote, “Those who consider Theopompus of Chios as a trustworthy writer may believe this story. For my part, in this story and in several others, I can only see the writer of fairy tales.”

After Plato had introduced the concept of a utopian society that vanished, other authors picked up the theme. Their interpretations sometimes differed from the legend of the Greeks, where the dissolute inhabitants of a flourishing civilization were punished by the cataclysmic destruction of their city. Atlantis was also used as a structure for fictionalizing an ideal modus vivendi, as in The New Atlantis, an essay published posthumously in 1627, a year after the death of its author, the English statesman, scientist, and philosopher Francis Bacon. Like many of the Atlantis stories that followed, it concerns some travelers blown off course (they are on their way from Peru to China and Japan) who fetch up on a previously undiscovered shore on an island in the South Sea. (In seventeenth-century England, the little-known Pacific Ocean was often referred to as the South Sea; Balboa had viewed its vast expanses one hundred fourteen years earlier, and Sir Francis Drake had crossed it in the Golden Hind in 1579, only forty-seven years before the publication of Bacon’s essay.) At the suggestion of St. Bartholomew, the ancestors on the island—which is known in their tongue as “Bensalem”—had built an ark and thus avoided the flood, and settled on this island, where they flourished for “an age or more.”

There is no question that Bacon had read Plato, since his New Atlantis contains many specific references to the Greek philosopher, articulated by the “Governor,” who explains Bensalem to the newcomers. He tells them “of the magnificent temple, palace, city, and hill, and the manifold streams of goodly navigable rivers” and how “within less than the space of one hundred years the Great Atlantis was utterly lost and destroyed; not by a great earthquake, as your man [Plato] saith, but by a particular deluge or inundation, these countries having at this day far greater rivers and far higher mountains to pour down waters than any part of the Old World.” The “Great Atlantis”—having been flooded and drained—is now America.* The “New Atlantis” of Bacon’s study is the island of Bensalem, where the travelers have landed.

SIR FRANCIS BACON, author of The New Atlantis, published in 1627—a fable about a lost island in the Pacific (illustration credit 2.1)

The inhabitants of Bensalem are completely self-sufficient, since their island is “5,600 miles in circuit, and of rare fertility of soil in the greatest part thereof,” and they practice productive commerce and trade with neighboring islands in the South Sea. Some nineteen hundred years earlier, the king of Bensalem had ordained that every twelve years two ships were to set out to collect information “especially of the sciences, arts, manufactures and inventions of all the world, and to bring unto us books, instruments, and patterns in every kind.…” With this information, the people of Bensalem managed to construct a futuristic city with towers a half mile high (“which we use for insulation, refrigeration, conservations,” and for a clear view of the weather); fresh- and saltwater lakes; artificial wells and fountains; great and spacious houses, “chambers of health, where we qualify the air as we think good and proper for the cure of divers diseases”; parks and enclosures for all sorts of beasts and birds; “dispensatories or shops of medicines; and divers mechanical arts which you have not; and stuffs made by them, as papers, linens, silks, tissues, dainty works of feathers of wonderful luster; precious stones of all kinds”; “instruments of music and harmonies which you have not”; engine houses, mathematical houses, and “houses of deceits of the senses, where we represent all manner of juggling, false apparitions, impostures and illusions, and their fallacies.” After explaining the wonders of this ancient but advanced civilization, the king presses two thousand ducats upon the English representative who was alone chosen to hear of Bensalem’s wonders, and says, “God bless thee, my son, and God bless this relation which I have made, I give thee leave to publish it, for the good of other nations, for here we are in God’s bosom, a land unknown.” In what is perhaps the greatest tribute to Plato, Bacon’s narrative finishes—as does the dialogue Critias—without an ending. Bacon’s New Atlantis closes with the words “The rest was not perfected.” By the seventeenth century, Atlantis was revived and embedded in the European consciousness.

ATLANTIS LOCATED IN the Atlantic, as shown in the 1665 Mundus Subterraneus by Athanasius Kircher (illustration credit 2.2)

SINCE BACON, there have been more revivals of the Atlantis scenario than “the glittering serpent” would ever have believed possible. Of the more respectable theories, the one with the most current support is the Minoan. For this reason, I have devoted a substantial portion of this study to a discussion of early Cretan civilization. Of all the proposed sites of Atlantis, only Crete and Santorini can be visited and the evidence evaluated by the casual observer. One can see the vast crater where a great island once stood, and the dusty rubble that marks the location of the palaces and houses of the Minoan empire. Even if Minoan Crete was not Atlantis—and it probably was not—the Minoan civilization deserves careful study.

It is, of course, only one of a number of possibilities. As T. Henri Martin wrote in the nineteenth century, “Many scholars, setting sail in quest of Atlantis with a more or less heavy cargo of erudition, but without any compass except their imagination and caprice, have voyaged at random. And where have they landed? In fifty different places.” James Bramwell, writing in 1938, reduced Martin’s fifty places to “eight main hypotheses”: Atlantis in America, in North Africa, and in Nigeria; Atlantis as an island in the Atlantic Ocean; Atlantis as Tartessos; Karst’s theory of a twofold Atlantis; Gidon’s theory of the land subsidences between Ireland and Brittany in the Bronze Age; and the theory that Plato’s Atlantis represents a memory of the flooding of the Mediterranean basin. Bramwell details some of these theories, but, unfortunately, with precious little documentation. Some of these Atlantean theorists, like Francis Bacon, are well known, but others, like Frobenius or Karst, are more obscure. L. Sprague de Camp’s chapter “Through a Glass Darkly” provides an excellent introduction to some of the more dubious theories of the location of Atlantis.

The idea of Atlantis in America originated with Francis Bacon, who wrote The New Atlantis in 1626, shortly after the first Englishmen had crossed the Atlantic to settle in the New World. As for North Africa, its vast expanses of sand seem to have generated any number of Atlantean stories, usually fabricated by Frenchmen who happened to be working there. In 1874, the French archaeologist Félix Berlioux claimed to have found the Lost City at the foot of the mountains in the Moroccan Atlas range, between Casablanca and Agadir. Berlioux’s theory was the basis for a novel called L’Atlantide, by Pierre Benoît, in which two Frenchmen find the Lost City in the mountains of southern Algeria, where for some reason the men wear the veil while the women do not. The heroine Antinéa keeps a pet leopard named Hiram, and she has such power over men that they commit suicide when she discards them. The novel was published in England as Atlantida, and in America as The Queen of Atlantis, and it was made into a movie three times: in 1921 as a silent film, in 1932 as a German-language talkie, and in Hollywood as Siren of Atlantis in 1948.

Claude Roux, another Frenchman, proposed that the Mediterranean coast of northwest Africa was once composed of great shallow lagoons that were extremely fertile and densely populated, but that successive invasions decimated the population until this “Atlantis” became only a memory. (Along with Jean Gattefossé, Roux assembled a seventeen-hundred-item bibliography on Atlantis in 1926.) In 1929, Count Byron Kuhn de Prorok published Mysterious Sahara, in which he contended that he had found traces of Atlantis in the desert, including a skeleton that he announced was that of Tin Hinan, the legendary matriarch of the Berbers. (Tin Hinan was also the subject of L’Atlantide.) The skeleton turned out to be the remains of a recently deceased Berber dignitary. Paul Borchardt, a geologist, claimed to have found Atlantis in Gabès, Tunisia, when he uncovered an ancient fortress, but it turned out to have been of Roman origin. Also in Tunisia, a German named Albert Herrmann found what he described as ancient irrigation works, which he concluded was a colony of Atlantis that had been located in the eastern Mediterranean but had originated in the German region of Friesland (now part of the Netherlands). Herrmann also decided that Plato’s numbers were off by a factor of thirty, and when he shrank the measurements accordingly, his Atlantis fit nicely into a corner of Tunisia. The manipulation of Plato’s dates would later develop into an important element in Atlantological research.

Bramwell also discusses “the explorer Leo Frobenius,” who claimed to have found Atlantis in the Yoruba country of Nigeria, based on a rather imaginative reading of Plato, where he reinterprets the “flourishing vegetation” as palm trees, bananas, and peppers and manages to get Plato’s always difficult elephants onto the right continent. The last of the African-Atlantis theories was propounded in 1930 by Otto Silbermann, who decided that Plato’s nine-thousand-year-old story was ridiculous on its face, since any civilization that old would have been forgotten long before the rise of Egypt. He suggested instead that Plato was recounting a Phoenician story describing a war with Libya that took place around 2450 B.C. in the Libyan desert, and like so many of his compatriots, he wrote a book.

Tartessos remains one of the great mysteries of ancient times. In Beyond the Pillars of Heracles, Rhys Carpenter presents a detailed study of its history—and the confusion surrounding it. In book 1 of the Historia (which Carpenter prefers to translate as “inquiry” rather than “history”), Herodotus tells us that “the Phocaeans were the first of the Greeks to undertake long sea voyages. It was they who made Adria known, and Tyrrhenia, and Iberia and Tartessos.” They hailed from Phocaea, the northernmost of the Ionian cities, on the west coast of Asia Minor, celebrated as a great maritime state. In their great fifty-oared longboats (penteconters), they arrived at Tartessos “and made themselves agreeable to Arganthonius, the King who had ruled the place for eighty years, and lived to be a hundred and twenty.” According to Herodotus’s very specific description, “They were driven westward right through the Pillars of Hercules until, by a piece of more than human luck, they succeeded in making Tartessos.” “If indeed they were the first Greeks to find it,” writes Carpenter, “then they were the first of their race to have seen and passed through the Gibraltar Strait and encounter the Atlantic tides.” Carpenter dates the Phocaean explorations from the early seventh century, which means that Herodotus (c. 485–425 B.C.), who related the story first, had to depend upon tales passed down to him. It also means that Plato, who lived from 428 to 347, would have been familiar with Herodotus’s stories of the Phocaeans’ explorations, and we can therefore safely say that Plato had at least enough knowledge of the Atlantic Ocean to include it in his tale of Atlantis.

In another, unrelated passage, Herodotus discusses the opening of Tartessos to Greek commerce:

A Samian ship whose captain and owner was a man named Kolaios put in at the island of Platea on his way to Egypt.… But as he was putting to sea again with the intent of sailing thither, he was carried off course by an east wind. And because the tempest did not abate, the mariners, thanks to divine guidance, passed out between the Pillars of Hercules and came to Tartessos. Now at this time this was an untouched virgin market, with the result that when they reached home again they made the greatest profit from their cargo of any Greeks about whom we have any reliable information.… So the Samians took out a tenth part of the profits, namely six talents, and had a bronze cauldron of Argolic type made, with heads of griffins jutting out around it; and this they dedicated to the temple of the goddess Hera; and under it they set three huge ten-foot figures of men kneeling.

This passage is, as Carpenter writes, “a nest of difficulties.” The island of Platea has been identified as lying between Crete and North Africa, but how are we to interpret a storm that was powerful enough to drive a ship eight hundred miles off course and out of the Mediterranean into the Atlantic without mishap?

Many scholars want to show that Tartessos was the biblical “Tarshish,” but while the names are similar enough to have caused confusion for two thousand years, the two places are now believed to have been completely different. Tarshish was situated in the eastern Mediterranean; Tartessos was far to the west. Jonah was heading for Tarshish before he had all that trouble with the whale, and in Ezekiel 27:12 we read that “Tarshish was thy merchant by reason of the multitude of all kind of riches; with silver, iron, tin, and lead, they traded in thy fairs.” A German historian named Adolf Schulten identified the parallel between Tarshish and Atlantis, pointing out that both were rich in metals and both disappeared. He spent several seasons digging to the north of the estuary of the Guadalquivir, but all he found was a single iron finger ring, with unintelligible letters engraved inside it. The truth, says Carpenter, is that there was no city of Tartessos, but rather, it was the name of the river (now the Guadalquivir) that served the mining commerce of the region. (There is still a mining town on the Río Tinto in southern Spain called Tharsis.) Tarshish, on the other hand, was probably the Greek trading town of Tarsus, only a few miles along the southern coast of Turkey from the Phoenician shoreland, a much more likely destination for Jonah.

Along came Mrs. Ellen Mary Whitshaw,* director of something called the Anglo-Spanish-American School of Archaeology, who claimed to have found evidence of Atlantis in Andalusia, and wrote a book with that title in 1928. In the practice common to Atlantologists, Mrs. Whitshaw uses Plato retroactively to support her findings. She wrote, “My theory, to sum it up concisely, is that Plato’s story is corroborated from first to last by what we find here, even to the Atlantean name of his son Gadir, who inherited that part of Poseidon’s kingdom which lay beyond the Pillars of Hercules and ruled at Gades, having its echo in the traditional Gadea on the Río Tinto in the jurisdiction of Niebla, an ancient mill under the shadow of a Stone Age fortress, relics of which still stand.”

According to Bramwell, the botanist François Gidon maintained that the Atlantis story contains an echo of the land subsidences between Brittany and Ireland, which opened up the English Channel, and that the Atlantis civilization described by Plato was indeed a Bronze Age civilization. An orientalist named Joseph Karst believed that there was an early Atlantis in the Arabian Sea, and another one in North Africa, “which at that time was still linked to Sicily by a Sicilian-Tunisian land bridge.…”

I have in front of me a book called The Ancient Atlantic. I don’t know who owned the book before; I got it in a used-book store. When I opened it, I found a sheaf of yellowed clippings between the pages, MILD QUAKE IN L.A. and MEXICAN SEXTUPLETS DEAD, and also a map of the Atlantic Ocean floor which had been used in an Alcoa magazine ad (“Come along with Alcoa, as we probe earth’s last frontier—and the richest”). The last owner was obviously interested in unusual phenomena—why else buy this book? It was apparently self-published by the author, L. Taylor Hansen. (From the initials, I could not tell if LTH was a man or a woman, but when I found “L. Taylor Hansen: A Sketch” in the index, I turned to page 423 and found a pencil drawing of the author, Lucile Taylor Hansen, dated 1942 and signed “Regaledo.”) The colophon page reads, “Printing: Tomorrow River Printers, Amherst, Wisconsin, 54406,” and “Binding: National Bookbinding Company, Stevens Point, Wisconsin, 54481,” so I think we are safe in assuming that Ms. Hansen lived (or lives) somewhere in the middle of the Badger State.

Ms. Hansen’s magnum opus is not your ordinary vanity-press book, hastily assembled and poorly manufactured. It has a proper dust jacket (but, alas, no author biography on the back flap), a reasonable binding of a sort of maroon leatherette, and typography that may not be of the highest quality but is not typewriter type, either. Moreover, The Ancient Atlantic is filled with color illustrations (remember, in 1969 they did not have color Xeroxing), a couple of foldout pages, and sixty-five chapters that cover everything from the Atlantis legend to Norse mummies, and include “The March of the Ar-Zawans,” “The Loch Ness Monster: A Plesiosaur,” “The War Dogs of the Ancients,” “The Kerrians or Carians,” and “The Round-Headed Landsmen.” The book, which is the size of a small coffee table, is a hefty 437 pages long, including the index, and cost me fifteen dollars. There are very few photographs, but there are about two hundred maps and illustrations, apparently drawn by the author, all of which are quite terrible. It is tempting to leaf through this book and poke fun at Ms. Hansen’s off-the-wall archaeology, but that is not my intention. Rather, I have cited this curious book to introduce the vast body of literature that is devoted to the myth of Atlantis, usually written to demonstrate that the myth is true, in one form or another.

———

LET LUCILE HANSEN introduce one of the first of the Atlantean scholars: the estimable Ignatius Loyola Donnelly. “During the eighties of the last century,” she wrote, “Ignatius Donnelly wrote a book called ‘Atlantis and the Antediluvian World’ [sic]. It was excellently researched for its day and the mistakes it made were due to the fact that science had not enough material to entertain a different viewpoint.” One of the most imaginative and influential of Atlantean scholars, Donnelly was born in Philadelphia in 1831. In the introduction to the 1976 edition of Donnelly’s book, E. F. Bleiler described him as “short, fat, redheaded … ebullient, witty, hardworking, gifted with remarkable powers of self-conviction, cheerful despite repeated misfortune on all levels of his life.…” A lawyer, he moved to Minnesota in 1856, and with John Nininger he cofounded a cultural center called Nininger City which failed after a year, leaving Donnelly the town’s only resident. This seemed naturally to lead to politics, and Donnelly became the lieutenant governor of Minnesota and then a member of Congress. He read voraciously—especially, it is said, in the Library of Congress—and published books on a wide variety of subjects. These included three novels; Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel, in which he tried to show that certain gravel deposits were the result of a near collision between the earth and a comet (a theme to be developed some sixty years later by Immanuel Velikovsky); and several books in which he argued that Shakespeare’s plays were actually written by Francis Bacon. (He also managed to break the code that proved that Bacon had written the plays of Marlowe and the essays of Montaigne.)

AFTER PLATO, Ignatius Donnelly (1831–1901) was the most influential figure in the history of Atlantology. (illustration credit 2.3)

But by far his most successful and popular work was Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, published in 1882. The book has gone through some fifty editions in several languages and is still being sold in bookstores. “Since Donnelly’s book,” wrote Martin Gardner, “an unbelievable number of similar works have appeared, though none has yet surpassed Donnelly’s in ingenuity and eloquence.” While it is tempting to paraphrase the ingenious and eloquent Ignatius Donnelly, probably the best way to understand the enduring fascination of this book is to quote the thirteen “distinct and novel propositions” with which he begins his disquisition:

1. That there once existed in the Atlantic Ocean, opposite the mouth of the Mediterranean Sea, a large island, which was the remnant of an Atlantic continent, and known to the ancient world as Atlantis.

2. That the description given by Plato is not, as has been long supposed, fable, but veritable history.

3. That Atlantis was the region where man first rose from a state of barbarism to civilization.

4. That it became, in the course of ages, a populous and mighty nation, from whose overflowings the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, the Mississippi River, the Amazon, the Pacific coast of South America, the Mediterranean, the west coast of Europe and Africa, the Baltic, the Black Sea, and the Caspian were populated by civilized nations.

5. That it was the true Antediluvian world; the Garden of Eden; the Garden of the Hesperides—where the Atlantides lived on the River Ocean in the West; the Elysian Fields situated by Homer to the west of the Earth; the Gardens of Alcinous—grandson of Poseidon and son of Nausithous, King of the Phaeacians of the Island of Scheria; the Mesomphalous—or Navel of the Earth, a name given to the Temple at Delphi, which was situated in the crater of an extinct volcano; the Mount Olympus—of the Greeks; the Asgard—of the Eddas; the focus of the traditions of the ancient nations; representing a universal memory of a great land, where early mankind dwelt for ages in peace and happiness.

6. That the gods and goddesses of the ancient Greeks, the Phoenicians, the Hindus, and the Scandinavians were simply the kings, queens, and heroes of Atlantis; and the acts attributed to them in mythology, a confused recollection of real historical events.

7. That the mythologies of Egypt and Peru represented the original religion of Atlantis, which was sun-worship.

8. That the oldest colony formed by the Atlanteans was probably in Egypt, whose civilization was a reproduction of that of the Atlantic island.

9. That the implements of the “Bronze Age” of Europe were derived from Atlantis. The Atlanteans were also the first manufacturers of iron.

10. That the Phoenician alphabet, parent of all European alphabets, was derived from an Atlantis alphabet, which was also conveyed from Atlantis to the Mayas of Central America.

11. That Atlantis was the original seat of the Aryan or Indo-European family of nations, as well as of Semitic peoples, and possibly also of the Turanian races.

12. That Atlantis perished in a terrible convulsion of nature, in which the whole island was submerged by the ocean, with nearly all its inhabitants.

13. That a few persons escaped in ships and on rafts, and carried to the nations east and west the tidings of the appalling catastrophe, which has survived to our own time in Flood and Deluge legends in the different nations of the Old and New Worlds.

It is obvious that in Atlantis, Donnelly had found the cause of almost everything.* Unfortunately, there is neither space nor time for a detailed analysis of his book, but it speaks more than satisfactorily for itself. He believed that Plato’s story was “a plain and reasonable history of a people who built temples, ships, and canals, who lived by agriculture and commerce, who in pursuit of trade, reached out to all the countries around them.” (He dismisses Bacon’s New Atlantis as “a moral or political lesson in the guise of a fable.”) Readers with an interest in his theories about “The Ibero-Celtic Colonies of Atlantis,” “The Turanian, Semitic, and Aryan Links with Atlantis,” or “The Origin of Our Alphabet” may consult these chapters in the book.

ACCORDING TO Ignatius Donnelly, Atlantis was located more or less where Plato said it was: in the Atlantic Ocean, outside the Pillars of Hercules. (illustration credit 2.4)

Donnelly’s thesis explained the similarities between pre-Columbian and Egyptian civilizations, often by bending facts until they were virtually unrecognizable. In Atlantis: Fact or Fiction?, Edwin Ramage wrote: “The propositions … hint at the general lack of critical judgment that pervades the book. On nearly every page there is an example of rash assumption, hasty conclusion, circular reasoning, or argument based purely in rhetoric. Many statements of fact are not fact at all, and in his enthusiastic drive to create his Atlantis he reveals a surprising naiveté.” Examples of his twisting of “facts” to make a point are legion, but here, one example will suffice. Answering his own question “Where was Olympus?” he says, “It was in Atlantis,” and then explains how he came to that conclusion: “Olympus was written by the Greeks ‘Olympus.’ The letter a in Atlantis was sounded by the ancient world broad and full, like the a in our words all or altar; in these words it approximates very closely to the sound of o. It is not far to go to convert Atlantis into Oluntos, and this into Olumpos. We may, therefore, suppose that when the Greeks dwelt in ‘Olympus,’ it was the same as if they said that they dwelt in ‘Atlantis.’ ”

IN RAMAGE’S BOOK (a collection of essays on various aspects of the Atlantean legend), the geologist Dorothy Vitaliano takes Donnelly to task on scientific grounds, which is a little like taking a sledgehammer to a mosquito. She dismisses his above-mentioned proposition 12 by showing that landmasses can sink, but not in a day and a night, and never on the scale attributed by Plato to Atlantis. She writes that “suddenly and catastrophically submerged areas, usually coastal areas depressed as the result of an earthquake, or in rare cases, a collapsing volcanic island, such as Krakatoa in 1883 or Santorini … are seldom larger than a few square miles.”*

Ignatius Donnelly’s Atlantis was published in 1882, the year before Krakatau erupted. We are probably fortunate that he had moved on to other subjects by 1883 (the year of the publication of Ragnarok), for the gigantic explosion of Krakatau would surely have provided Donnelly with an abundance of supporting evidence for the possibility of disappearing civilizations. The explosion, which began on August 27, was heard in Australia, over two thousand miles away, and sent a 50-mile-high cloud of volcanic ash into the sky that circled the earth for two years. A 6,000-foot-high mountain was reduced to a caldera 4 miles across with only portions of the rim (now the islets of Rakata, Pulau Sertung, Lang, and Polish Hat) projecting above the surface of the Sunda Straits (see this page–this page). He did, however, devote an entire chapter to the question “Was Such a Catastrophe Possible?,” in which he wrote that “there is ample geological evidence that at one time the entire area of Great Britain was submerged to the depth of at least seventeen hundred feet,” and that “the Canary Islands were probably a part of the original empire of Atlantis.” Not only is such a catastrophe possible, but comparable events have occurred time and again throughout history. He mentions the 1775 earthquake at Lisbon (“the point of the European coast closest to Atlantis”), the 1815 eruption of the Javan volcano “Tomboro,” and Santorini, of which he wrote:

The Gulf of Santorin, in the Grecian Archipelago, has been for two thousand years a scene of active volcanic operations. Pliny informs us that in the year 186 B.C. the island of “Old Kaimeni,” or the Sacred Isle, was lifted up from the sea; and in A.D. 19 the island of “Thia” (the Divine) made its appearance. In A.D. 1573 another island was created, called “the small sunburnt island.” In 1848 a volcanic convulsion of three months’ duration created a great shoal; an earthquake destroyed many houses in Thera, and the sulphur and hydrogen issuing from the sea killed 50 persons and 1,000 domestic animals. A recent examination of these islands shows that the whole mass of Santorin has sunk, since its projection from the sea, over 1,200 feet.

“All these facts,” he wrote, “would seem to show that the great fires which destroyed Atlantis are still smoldering in the depths of the ocean; that the vast oscillations which carried Plato’s continent beneath the sea may again bring it, with all its buried treasures, to the light; and even that the wild imagination of Jules Verne, when he described Captain Nemo, in his diving armor, looking down upon the temples and towers of the lost island, lit by fires of submarine volcanoes, had some groundwork of possibility to build on.”*

Although Donnelly’s Atlantis is a garbled muddle of misunderstood geology, anthropology, mythology, and linguistics, it had twenty-three printings from 1882 to 1890, and a Dover edition was issued in 1976, almost a century after it was written. In the introduction, Bleiler asks, “Why should Dover Publications reprint a book that cannot be taken seriously, a book that is admittedly wrong in all its major conclusions, and can never be rehabilitated?” His answer:

Donnelly’s Atlantis: The Antediluvian World is a remarkable tour de force. His enthusiasm vivified what might have been embalmed in a cabinet, and turned it into a book vital for certain temperaments. Donnelly created a vision of a golden past, of soaring adventurers, spreading civilization around the world, of Edens that once existed, were let perish—and should be a lesson to all of us. Strangely enough, there is a moral in Donnelly’s Atlantis, just as there was in Plato’s: power corrupts.…

Did Donnelly pay any attention to his critics and detractors? We will never know, but a careful reading of his book leads to the almost inescapable conclusion that he believed every word he wrote. Certainly a lot of other people did, including the Scottish mythologist Lewis Spence, who published The Problem of Atlantis in 1924. (Subsequently, he would produce several more books on this subject, including The History of Atlantis, published posthumously in 1968; he died in 1955.) In the introduction to the 1949 “modern revised edition” of Donnelly’s book, Spence wrote, “I should like to make it clear that my hypothesis respecting the existence of an Atlantean culture-complex in certain parts of Europe and America … is the direct outcome of Donnelly’s method, a mere modern application of it, indeed.… If Plato stands at the threshold of our quest, it is the torch of Donnelly which most brightly illuminates our passage along the rough and shadowy highway which we hopefully traverse.”

One of history’s most dedicated Atlantean scholars, Spence was a newspaperman, a poet, and cofounder of the Atlantis Quarterly, a journal devoted to Atlantean and other occult studies. Although Spence would not have us accept the fundamentalist view of Plato’s description (“We must remember that it is not by any means incumbent upon us to attempt to justify Plato’s account word for word.… It is obvious that we are dealing with a great world-memory, of which Plato’s story is merely one of the broken and distorted fragments”), he assembles material from many disciplines, among them ethnology, geology, history, biology, and folklore, and then concludes that an entire continent used to bridge Europe and America. (In their 1952 study of the Gulf Stream, Henry Chapin and F. G. Walton Smith said that Spence “has made the most thoroughgoing and serious study of the Atlantis question since Donnelly.”) He says the continent sank in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, leaving as evidence of its existence the Azores, the Canaries, and Madeira in the east, and in the west, where there was another sunken continent called Antilla, now the location of the West Indies.* He further describes the Atlantean inhabitants of the predeluge continent as “Aurignacians or Cro-Magnons … exceptionally tall, sons of the gods indeed, the male height averaging from 6 ft. 1 in. to 6 ft. 7 in., although the women were small, the proof of a mixed race.” Lest this sort of thing sound like advocacy of a master race, Spence was obsessed with what he believed was a parallel between the fall of Atlantis and the decadence of Europe in the 1940s. In 1942, he published Will Europe Follow Atlantis?, in which he argued that all Europe—but especially Nazi Germany—was suffering from great moral decay, and unless they returned to true Christianity, the Germans were going to receive a punishment “of the self-same form meted out to the people of Atlantis.”

Spence falls into the protohistorical trap of assuming that since other myths—such as Homer’s account of the Trojan War—had proved to be based on fact rather than fiction, therefore Plato’s story of Atlantis must also be true. He writes, “It is now generally accepted by critics of insight—the others do not matter much—that when a large body of myth crystallizes round one central figure, race, or locality, it is almost certain to enshrine a certain proportion of historical truth capable of extraction from the mass of fabulous material which surrounds it, and when so refined, is worthy of acceptance by the most meticulous of historical purists.”

Somehow, Spence manages to demonstrate that Plato’s detailed plan of Atlantis is so similar to that of Carthage, and that “a comparison of these resemblances, which include the most unusual features, will leave no doubt in any unbiased mind that the plan of Carthage was substantially the same as that of Atlantis.” Unfortunately for Spence’s theory, Carthage’s “unusual features,” consisting of a citadel on a hill (the “Byrsa”), docks, canals, a circular colonnade, and a great seawall, were built long after Plato’s Atlantis, even if we afford Spence the benefit of the doubt and assume that Atlantis existed only nine hundred years before Plato, and not the nine thousand years that Plato claims. How to deal with this? Easy: “Plato could not have been aware that this description [of Atlantis] could apply to a future Carthage, therefore it seems probable … that Carthage was planned in accordance with ancient Atlantean design which had long been in vogue in North-Western Africa and Western Europe.” In the middle of his learned discussion, Spence throws this in: “I must also point out that the passage which speaks of the twenty golden statues of the kings of Atlantis and their wives has a striking parallel in Peruvian history.” (In later chapters, he will incorporate intricate elements of Peruvian history, as well as other Mesoamerican cultures, to prove that the history of Atlantis was closely connected with that of Mexico and South America.)

In The Ocean River, Chapin and Smith invoke “the French savant Termier” (actually Professor Pierre Termier of Paris, a geological Atlantologist), describing him as “convinced that there is enough geological evidence to put solid ground under the overseas legends.” (Spence identifies Termier as “a geologist of the highest standing and authority, Director of Science of the Geological Chart of France.”) In 1915, Termier wrote: “Geologically speaking, the Platonic history of Atlantis is highly probable.… [I]t is entirely reasonable to believe that long after the opening of the Strait of Gibraltar, certain of these emerged lands still existed, and common among them a marvelous island, separated from the African Continent by a chain of smaller islands.”*

Although “a geologist of the highest standing,” Termier could have had only vague knowledge about the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (which was first examined in the late 1940s), so his description of the floor of the Atlantic has to have been based on what was known at the time. Nevertheless, he came surprisingly close to describing what would eventually prove to be a vast undersea mountain range when he postulated two great valleys parallel to the coastlines of Europe and North America, separated by an elevated “middle zone.” He believed that the “middle zone” was S-shaped (which it is) and ran from Greenland to 70° south latitude (which it almost does). But then he says that the eastern region of the Atlantic is “a great volcanic zone,” and that the bottom of the ocean there is “the most unstable zone on the earth’s surface, where at any moment unrecorded submarine cataclysms may be taking place.” (And so they are, but they are not dropping the continents into the sea.) In his richly textured prose (Termier’s theories were published in 1912 in France, and reproduced in translation in the Smithsonian Institution’s Annual Report for 1915), Termier said:

Meanwhile, not only will science, most modern science, not make it a crime for all lovers of beautiful legends to believe in Plato’s story of Atlantis, but science herself, through my voice, calls their attention to it. Science herself, taking them by the hand and leading them along the wreck-strewn ocean shore, spreads before their eyes, with thousands of disabled ships, the continents submerged or reduced to remnants, and the isles without number enshrouded in the abyssmal depths.

(Although he does not mention Termier by name, W. D. Matthew of the American Museum of Natural History in New York wrote a brief reply to “some writers” who believed that a land bridge across the Atlantic in former geological times could be equated with Plato’s Atlantis. Matthew (writing in 1920) said, “Examination of the story in detail shows that it is a fable, and that the scientific evidence does not lend any support whatsoever to it nor vice versa.”)

As the agent that caused the Atlantean continent to disappear into the ocean, Spence invokes continental drift, although he does not actually name it. In his 1924 book, he cites Termier, J. William Dawson, Henry Fairfield Osborn, Alfred Russel Wallace, and Professor Edward Hull (“whose investigations have led him to conclude that the Azores are the peaks of a submerged continent that flourished in the Pleistocene period”) as his sources, but he does not mention Alfred Wegener, who first published the theory in 1915. Spence says that

more daring speculators believe that beneath the ocean spaces no solid Sal [silica and aluminum] exists at all, and the continental masses float on the liquid Sima [silica and magnesium] much as icebergs in the ocean. If, for any reason, a fissure develops in these floating masses the break may grow until at last two separate bodies appear, which will naturally drift away from each other by degrees. Such a condition, it is thought, accounts for the separation of the American Continent from the Old World.

More often than not, Atlantean scholars manipulate existing science in a convoluted way to prove their specious doctrines, but in this instance, an Atlantean proponent accidentally incorporated a highly speculative (but now accepted) doctrine—that of continental drift—into his arguments. Among the “more daring speculators” was Alfred Wegener, who had published The Origin of Continents and Oceans in 1915, to almost universal rejection.

In 1926, at a symposium called by the American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Wegener’s theory was widely ridiculed, since it was impossible for anyone to imagine what forces could possibly move entire continents. In his “definitive” study (of 1924), Sir Harold Jeffreys, a British geologist, dismissed the theory of continental drift in these words: “It is quantitatively insufficient and qualitatively inapplicable. It is an explanation which explains nothing we want to explain.” In their unfortunate analysis of the Atlantean and continental-drift hypotheses, Chapin and Smith wrote that Wegener’s theory was only one possibility, and that “a newer but equally fascinating proposal has recently been advanced by J. P. Rothe, who believes that that the Mid-Atlantic Ridge is really the submerged coastline of Africa and Europe, now sunk beneath the waves. The western basin is thus the true ocean, while the eastern basin is really part of the sunken mainland.” If the “eastern basin” is part of the sunken mainland, then part of that submerged continent was very likely to be Atlantis. J. P. Rothe’s ideas have faded into oblivion, and Wegener was vindicated—the continents do drift around like icebergs, albeit somewhat more slowly—and so far, there is no evidence to indicate that the mysterious island (or continent) of Atlantis disappeared into the Atlantic Ocean.

Chapin and Smith concede that “sub-marine dredging and the firing of explosive charges and the painstaking reading of delicate instruments will bring new evidence to clinch the matter,” and finally label the legend “a fascinating myth or fable.” But, they write, “perhaps the reverse may come about, and the future thus bring new life to Atlantis in the mind of man.” Of course, Chapin and Smith, writing in 1952, did not have the advantage of the discovery of sea-floor spreading, and they believed (following Termier) that the Mid-Atlantic Ridge was “a great 7,000-mile submarine mountain chain from Iceland in the north to Bouvet Island … [that] divides the Atlantic Ocean into eastern and western basins.” Such an underwater chain exists, but it has now been recognized as a mountainous seam of volcanic action, surrounded on either side by fracture zones, which would make the existence of a submerged continent more than a little implausible, and would substantially detract from the credibility of Donnelly, Spence, and “the French savant Termier.”

Many of the early Atlantologists—including Donnelly, Spence, and Termier—liked to use complex scientific arguments to prove the existence of Atlantis. Always the innovator, Donnelly came first, with his chapter “The Flora and Fauna of Atlantis.” In addition to a garbled discussion of fossil camels, cave bears, and domesticated animals, Donnelly believed that one of the strongest indicators of Asia and Africa’s dependence upon Atlantis thousands of years ago is the presence of the seedless banana. “Is it not more reasonable,” he asks, “to suppose that the plantain, or banana, was cultivated by the peoples of Atlantis, and carried to their civilized agricultural colonies to the east and west?” He answers: “It would be a marvel of marvels if one nation, on one continent, had cultivated the banana for such a vast period or time until it became seedless … but to suppose that two nations could have cultivated the same plant, under the same circumstances, on two different continents, for the same unparalleled lapse of time, is supposing an impossibility.” Q.E.D., Atlantis proved by a banana. (Fifty years later, when Lewis Spence wrote about the biological evidence, he said that “the prolonged controversy which raged round the question of the Atlantean origin of the seedless banana … seems to me worse than futile.… I propose to adhere to the conclusions of tried modern scientists, and to disregard the gropings of the older school as no longer of much avail in our quest.”)

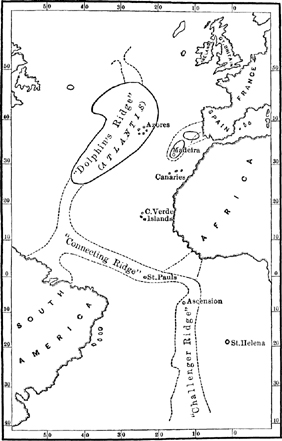

ATLANTEAN SCHOLARSHIP often depends on the refutation or denial of previous theories; Atlantis cannot have been in the Bahamas and Mediterranean at the same time. (At one time or another, Atlantis has been located in the Arctic, Nigeria, the Caucasus, the Crimea, North Africa, the Sahara, Malta, Spain, central France, Belgium, the Netherlands, the North Sea, the Bahamas, and various other locations in North and South America.) But Spence pinpoints the actual location of Atlantis—even though he quotes Termier as saying “we must not even consider this problem.” Based on a convoluted discussion of Carthage, the stone forts of the Aran Islands, the design of Mexico City, and the Egyptian pyramids, he says, “Dolphin’s Ridge, then, I accept as the site of lost Atlantis.” Named for the ship Dolphin that took soundings in the vicinity, the ridge is a long oval, connected underwater to the Azores, South America, and the “West African island of St. Pauls.” (It turns out that Ignatius Donnelly also thought that Dolphin’s Ridge was the long-sought location; he wrote, “The Atlantis of Plato may have been confined to the ‘Dolphin Ridge’ of our map.”)

At the conclusion of the preface to The Problem of Atlantis (reissued in 1974 as Atlantis Discovered), Spence declared, “On the other hand, I think I have brought cogent arguments against the now widely accepted theory that the idea of Atlantis arose out of a memory of the former civilization of Crete.” He launches into a spirited devaluation of the story—which first appeared in the British newspapers in 1909—that the palace at Knossos in Crete recently discovered by Sir Arthur Evans was concrete evidence of the existence and location of Atlantis. Spence argues that, rather than the Atlantis legend being based on the downfall of Knossos, the mythology has become confused, and “it is the Cretan civilization that was modeled on that of Atlantis.” He defends this argument as follows: “The theory that Crete was a colony of Atlantis is greatly assisted by the circumstance that the Cretans were largely of that Iberian race which undoubtedly emanated from Atlantis.” Undoubtedly. “They worshipped a goddess who was connected with the serpent like the Mexican Coatlicue, whom she remarkably resembles in details of costume.” In his final argument, Spence enlists the support of Heinrich Schliemann: “And let it be remembered,” he crowed, “that the man who justified his dreams of Troy to the confusion of a thousand scoffers entertained as firm a belief in the existence of a submerged Atlantis.”

An even more bizarre footnote to the annals of Atlantean scholarship was added by Paul Schliemann, who identified himself as the grandson of the German archaeologist who excavated Troy and Mycenae (see this page–this page). He claimed that among his grandfather’s papers was a note instructing the reader to break open the “owl-headed vase” that contained certain documents relating to Atlantis. Breaking it open, Paul Schliemann found bits of pottery, objects made of fossilized bone, and a silvery coin. In October 1912, in the New York American, young Schliemann told the story he called “How I Found the Lost Atlantis, the Source of All Civilization,” in which he described his worldwide search for the evidence mentioned by Heinrich, which took him to Egypt (where he found coins like the one in the vase, made of an alloy of platinum, aluminum, and silver), Central America (where he found another owl vase), and West Africa. In his article, Paul Schliemann included the startling revelation that a Mayan text and a Tibetan manuscript both told the story of a cataclysm in a country called Mu, and, even more sensationally, that he had actual Atlantean artifacts in his possession. Schliemann claimed that all this material unequivocally proved the existence of Atlantis—which he said had sunk, leaving only the Azores as the tips of the submerged mountains—and he promised to reveal all in a forthcoming book. (He also identified his grandfather as “excavating at the Lion Gate at Mycenae in Crete,” a most unlikely quote, since of all people, Heinrich Schliemann would know that Mycenae was not in Crete.) Neither the book nor Paul Schliemann’s “evidence” ever appeared, and under close examination, his references bore a strong resemblance to other published texts, especially those of Ignatius Donnelly.* Most writers repeat this story without taking the trouble to question whether Paul was really Heinrich’s grandson, but several dubious investigators have revealed that while Heinrich had a brother named Paul, he had no grandson by that name.

PAUL SCHLIEMANN, who claimed to be Heinrich Schliemann’s grandson, said that he found evidence of Atlantis in his grandfather’s papers, including this map, which was published in the New York American on October 20, 1912. (illustration credit 2.5)

With the advent of more sophisticated tools for underwater exploration, one might assume that searchers would be able to see that there is no drowned continent on the bottom of the ocean, but the pull of the legend is so powerful that despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, we are still getting books purporting to prove the existence of Atlantis. (And such books will continue to appear, since it is impossible, of course, to prove that it does not exist.) To write one of these books, the author has to be predisposed to believe not only Plato but the veritable legion of Atlantologists who succeeded him.

Charles Berlitz, the grandson of the founder of the language schools, in 1974 published a book called The Bermuda Triangle, in which he discussed the “hundreds of ships and planes, with their crews and passengers, [that] have disappeared without a trace during the last fifty years,” and in 1977, he published Without a Trace, which is (according to its flap copy) “filled with startling stories of strange occurrences within the Triangle: peculiarities of sea and weather; the appearance of ‘ghost ships’ and a catalog of vessels which have disappeared from 1800 through 1976; clouds that seem to chase and capture planes; time warps; and the possibility of a doorway in the area leading to another dimension, or even to outer space.” In his chapter “Lost Atlantis—Found in the Bermuda Triangle?,” Berlitz introduces his idea that the “Triangle,” in addition to swallowing ships, has also gobbled up an entire continent. He finds support for this idea in the Bimini explorations of Dr. David Zink, the prophecies of Edgar Cayce, and the research of “Ronald Waddington of Burlington, Canada, a researcher and theorist on the Bermuda Triangle.” Waddington—who is quoted at length in Without a Trace—theorizes that underwater volcanoes are constantly shooting chunks of radioactive, densely magnetic material into the air, short-circuiting the electrical equipment of passing airplanes and causing them to nose-dive into the ocean. As for ships, “chunks of this radioactive material could shoot to the surface with the velocity of a hydrogen bomb and home in on the steel hulls of ships like the magnetic head of a torpedo.…” Berlitz acknowledges that “Waddington’s suggestions predicate no link between Atlantis and the present occurrences in the Bermuda Triangle, [but] the series of reactions he describes might, nevertheless, have endured as a by-product of the catastrophe that caused the Atlantean lands to sink beneath the ocean.” Berlitz was evidently so entranced with the mystery of Atlantis that he wrote another book about it, Atlantis: The Eighth Continent.

On the endpaper maps, which consist of a drawing of the eastern Atlantic basin drained of water, Berlitz sets the tone for this exposé: “On this modern map of the Atlantic Ocean Floor we can see that oceanic islands such as the Azores, Madeira, and the Canaries are connected to great submerged plateaus, some of them in the very area that this sunken land was supposed to be, as if they were the mountaintops of Atlantis, the eighth continent.” The map shows no such thing; it simply shows the seamounts that characterize this region of the Atlantic and the abyssal plain between the Canaries and Madeira. There is nothing on Berlitz’s map that looks anything like a plateau or a missing continent. But by the time we get to the introduction, Berlitz (who lists Ignatius Donnelly and Lewis Spence in his bibliography) is in full cry: “A civilization developed in these huge islands and spread, through conquest and colonization, throughout the Atlantic Basin and farther to the islands and coasts of the Mediterranean. Thousands of years before the beginnings of history in Egypt and Mesopotamia, this civilization disappeared into the Atlantic Ocean, leaving only isolated colonies on the surrounding continents which grew into the civilizations that we consider the beginnings of history.”

Berlitz covers all the possible locations discussed by earlier authors, including Tunisia, Heligoland (a German pastor named Jürgen Spanuth located Atlantis in the North Sea off Germany), Yucatán, Bolivia, Morocco, Nigeria, Arabia, Brazil, Antarctica, the Indian Ocean, the Sahara Desert, and “other parts of Europe and Asia,” but in the end, although he cannot locate it exactly, he says that the very number of possible sites “may also be considered as an indication of the common culture of a previous civilization, whose great stone remains on all continents (except Australia and Antarctica—and perhaps there too when further explorations are made) tend to resemble one another in construction and astronomical orientation.” In other words, the proliferation of reports, none of them more dependable than the others, suggests to Berlitz that Atlantis must have existed, even if we are not sure where it might have been. And as for Thera, he dismisses it as a legitimate possibility and says it was “simply one more victim of natural disasters in the Mediterranean and is not in name or description connected with the Atlantis of Plato and other commentators.” (Anyway, he says, Thera is too small to have been occupied by the number of people Plato said lived in Atlantis.)

For skeptics who require documentation, Berlitz provides a story that he says is “well reported in a ship’s log and also in the press.” In March 1882, the British merchant vessel Jesmond, Captain Robson commanding, was sailing from Messina, Sicily, to New Orleans with a cargo of dried fruit. A couple of hundred miles west of Madeira, the ship encountered muddy water and enormous shoals of dead fish. They sighted smoke coming from an island where no island was supposed to be, dropped their anchor, and went ashore on an island that had “no vegetation, no trees, no sandy beaches … [and was] bare of all life as if it had just risen from the ocean.” What do you do when you land on an uninhabited, barren island in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean? Why, naturally, you begin to dig. The crew uncovered massive walls, and then “bronze swords, rings, mallets, carvings of heads and figures of birds and animals, and two vases or jars with fragments of bone, one cranium almost entire … and what appeared to be a mummy enclosed in a stone case.” Captain Robson loaded all this booty aboard the Jesmond and continued his voyage. Berlitz does not say whether he off-loaded his cargo at New Orleans, but he does tell us that Robson intended to present the stuff to the British Museum. Alas, the log of the Jesmond was destroyed in the Blitz of 1940, and the artifacts never showed up at the museum. Berlitz thinks they may still be there, “filed in the capacious attics and basements common to all great museums.”

Beyond the unfortunate loss of the Jesmond’s log, there are more than a few problems with Berlitz’s approach to his subject. First is the wholesale inclusion of statements and data without attribution. Ordinarily, attributions are identified by including the name of the author and the work in the sentence, as in, “as Conan Doyle said in The Maracot Deep.…” Another method involves footnotes or notes in the back of the book identifying the source of the information, neither of which device is employed here. (Another mechanism, used primarily in scientific publications, is the use of parenthetical citations, e.g., “(Verne 1870),” which follow a quote and enable the reader to check the source of a particular quote and, if necessary, verify it.) In Berlitz’s Atlantis, we are given all sorts of “facts” used to make a particular point, but without the possibility of knowing who was responsible for the statement in the first place, or, indeed, if anyone other than Berlitz himself was the actual source.

In his chapter entitled “The Great Islands Under the Sea,” Berlitz outdoes himself in non- or misattributed statements. The entire book is filled with such useless data, but a couple of examples will serve as demonstrations: To explain the presence of “architectural remains” on the sea floor, Berlitz refers to “pictures taken from the Anton Bruun research vessel for the purpose of photographing bottom fish in the Nazca Trench off Peru in 1965,” where “a chance photograph showed massive stone columns and walls on the mud bottom at a depth of one and a half miles.” In fact, there is no such thing as the “Nazca Trench,” but off Peru, the Peru-Chile Trench is some 10,000 feet deep. In 1965, if such a sighting had somehow been made, it probably would have been published somewhere. But Berlitz does not say how he knows about it, and moves right on to the next sentence, which is about the submersible Archimède that encountered a “flight of giant stone steps at a depth of 1,400 feet off the Bahamas.”

Berlitz introduces the theory of continental drift and somehow contorts it to verify the existence of Atlantis. He has oceanographer Maurice Ewing discuss beach sand on the floor of the ocean, and he quotes him as saying, “Either the land must have sunk two or three miles or the sea must have been two or three miles lower than now.” Ewing did say this (in a 1949 National Geographic article on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge), but he followed it immediately with, “There is no reason to believe that this mighty underwater mass of mountains is connected in any way with the legendary lost Atlantis which Plato described as having sunk beneath the waves” (my emphasis). Berlitz then presents “Dr. R. Malaise” (but gives no supporting reference in the bibliography), who found the “remains of land-grown plants in cores taken two miles down in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.” Ignoring the information that would refute such a statement, Berlitz then goes on to say that “the theory of the vertical movement of tectonic plates and its modification of the continental-drift theory has brought about a reassessment of the possibility that Atlantis once really existed as lands in the Atlantic Ocean.” His conclusion—that the various seamounts off the Azores prove the existence of a sunken continent—is not supported by any of his quotes, but the quotes and conclusions are mostly fabrications and distortions, anyway.*

Berlitz’s comprehension of biology and zoogeography is so wrongheaded that it beggars understanding. For example, he wrote that there are “two kinds of seals, the monk and the siren, found off the coast of the Azores,” from which he infers that “they were among the birds and animals isolated on the ocean islands after the disappearance of their former habitat of continental proportions.” In fact, there are monk seals on various islands in the Mediterranean and eastern North Atlantic, but they did not find themselves stranded there when a continent disappeared out from under them. (Seals are good swimmers, and could easily have colonized the islands from other European or African locations.) There is not now, nor has there ever been, a seal known as the “siren”; the only creature that bears this name (because it belongs to the family Sirenidae) is the manatee, a mammal not related to the seals and certainly not found in the Azores. (The closest manatees are found in West Africa.)*

Charles Berlitz’s chapter on animal life is obviously derived from Spence’s “biological evidence,” since it makes just as little sense and, in one instance, lifts a whole paragraph about birds circling around an open area of the sea as if trying to land where there is no land—an obvious indication that there used to be a continent there. Further using animals to verify the existence of Atlantis, Berlitz incorporates a long-winded, irrelevant section on dinosaurs in which he proves—at least to his own satisfaction—that a large-scale catastrophe was responsible for their disappearance, and argues that if such a catastrophe could cause such creatures to vanish, it could certainly eradicate a city. He writes: “Perhaps the combination of fiery shocks from the sky, the resultant shaking of the Earth, and flooding from the sea was the sequence of events that occurred in the prehistoric world that perished.” †

In his 1950 Worlds in Collision, Immanuel Velikovsky (1895–1979) argued that the planet Venus had closely approached Earth as a comet and caused tremendous upheavals on this planet, many of which—like the downfall of Atlantis—are documented in ancient texts. Velikovsky also seems to be among the first to identify Plato’s 8,100-year chronological error, and wrote, “There is one too many zeros here.” He says that the cause of this mistake is that “numbers that we hear in childhood often grow in our memory, as do dimensions. When revisiting our childhood home, we are surprised at the smallness of the rooms—we had remembered them as much larger.” Regardless of this somewhat unproductive interpretation of the compression of time, however, Velikovsky’s often bizarre ideas about the history of catastrophe received great publicity. In discussing Velikovsky’s ideas, L. Sprague de Camp wrote, “An even madder theory of periodical catastrophes was brought out recently by Immanuel Velikovsky, a Russo-Israeli physician and amateur cosmogonist whose publishers stirred up an extraordinary hoopla in 1950 to sell his book.”

It has not been shown that Venus came close enough to Earth to cause “a torrent of large stones coming from the sky, an earthquake, a whirlwind [and] a disturbance in the movement of the earth,” but many of the phenomena described by Velikovsky could easily be attributed to large-scale volcanic eruptions. For example, in the Plagues of Egypt, where he ascribes “a thick darkness … which may be felt” (Exodus 10:21–22) to “onrushing dust sweeping in from interplanetary space,” a more logical interpretation of the darkness would be the ash cloud emitted by a great volcanic eruption, as has been observed many times in recent history.

Velikovsky believed that “the swift shifting of the atmosphere under the impact of the gaseous parts of the comet, the draft of air attracted by the body of the comet, and the rush of the atmosphere resulting from the inertia when the earth stopped rotating or shifted its poles, all contributed to produce hurricanes of enormous velocity and force and of world-wide dimensions.” But again, a somewhat more prosaic—albeit immense and terrifying—explanation for this catastrophe can be found in the phenomenology of volcanoes. The nuée ardente, or “flaming cloud,” produced when a heavier-than-air ash cloud cascades down the slope of an erupting volcano at speeds up to 100 miles an hour, as it did at Mount Pelée in 1902 (see this page–this page), seems to be a more likely explanation. As for “rising tides,” certainly tsunamis are a more reasonable explanation than “a comet with its head as large as the earth, passing sufficiently close [that] would raise the oceans of the world miles high.”

Velikovsky quotes the Popul Vuh,* the Manuscript Cakchiquel, and the Manuscript Troano, sacred Mayan texts that describe a time when “the earth burst and the lava flowed,” and biblical passages where “the mountains shake with the swelling” (Psalm 46:3) and “the earth trembled … the mountains melted …” (Judges 5:4–5). It takes very little imagination to see that in Job (9:6–7), when “the pillars [of the earth] tremble … the sun … riseth not and sealeth up the stars,” the events being described might easily refer to a volcanic eruption. It is not that Velikovsky does not know of or acknowledge volcanoes; he says, “An entire year after the eruption of Krakatoa … in 1883, sunset and sunrise in both hemispheres were very colorful.… In 1783, after the eruption of Skaptar-Jökull in Iceland, the world was darkened for months.…” He simply does not believe that a single eruption would have been sufficient to cause the massive disruptions he discusses. “If the eruption of a single volcano can darken the atmosphere over the entire globe,” he wrote, “a simultaneous and prolonged eruption of thousands of volcanoes would blacken the sky.”

And what did all of this have to do with Atlantis? In Plato’s Timaeus, Velikovsky found a passage that echoed all the other references to the earth standing still, or the sky going black:

“Your story,” says the Egyptian priest to Solon, “of how Phaëthon, child of the sun, harnessed his father’s chariot, but was unable to guide it along his father’s course and so burnt up things on earth and was himself destroyed by a thunderbolt, is a mythical version of the truth that there is at long intervals a variation in the course of the heavenly bodies and a consequent widespread destruction of things on the earth.”

To Velikovsky, this is one more validation of his theory of planetary interference with the earth, and he says that Plato himself has verified it. In Worlds in Collision, Velikovsky follows his discussion of Atlantis with a lengthy discourse on the origin of Venus as a comet, as described by various observers—he quotes Alexander von Humboldt as asking, “What optical illusion could give Venus the appearance of a star throwing out smoke?”—and then presents a detailed survey of Venus-worship in ancient literature, from Egyptian, Greek, and Indian; and from the “Indians” of North and South America.

At this point, he introduces an entirely new concept: that Mars and Venus collided (hence the title of his book) and “the planet Mars saved the terrestrial globe from a major catastrophe by colliding with Venus.” He provides documentation for this revelation from the mythology and folklore of the ancient Greeks—he says that the conflict in the Iliad is really between Mars (Ares) and Athene (the planet Venus)—as well as from Toltec mythology, the Tao of Chinese cosmology, the Yuddha of Hindu astronomy, and the Babylonian sword god Nergal.

“One of the most terrifying events in the past of mankind,” wrote Velikovsky, “was the conflagration of the world, accompanied by awful apparitions in the sky, quaking of the earth, vomiting of lava by thousands of volcanoes, melting of the ground, boiling of the sea, submersion of continents, a primeval chaos bombarded by flying hot stones, the roaring of the cleft earth, and the loud hissing of tornadoes of cinders.” That events of this magnitude could have gone largely unrecorded, he attributes to collective amnesia; people forgot it because it was too terrible to remember: “The memory of the cataclysms was erased, not because of a lack of written traditions, but because some characteristic processes that later caused entire nations, together with literate men, to read into these traditions allegories or metaphors where actually cosmic disturbances were clearly described.”*

The possession of scientific credentials does not automatically bestow verisimilitude on one’s work, especially if one is working outside one’s field of expertise. As Moses Finley asked (in his review of Mavor’s Voyage to Atlantis), “What is it that prompts scientists capable of precise and rigorous work in their own disciplines to career about in other fields of inquiry, where they lack the knowledge, the tools of analysis, or even common sense?” A case in point is the German scientist Otto Muck, who graduated with a degree in engineering from the Munich College of Advanced Technology in 1921 and worked as a scientist/inventor during World War II, inventing the Schnorchel for U-boats and contributing to the development of the V-2 rocket at Peenemünde. Somehow, his studies and experience developing Nazi weapons of war qualified him as an expert on Atlantis, so he wrote The Secret of Atlantis, which was published in English in 1978. (He died in 1956.)

It is a maddeningly inconsistent book, alternating lucid passages with absurd statements such as: “In 1836, strange letters were discovered on the rock of Gávea in South America. One of the rocks was sculpted into an enormous bearded man’s head wearing a helmet.… Bernard da Sylva Ramos, an amateur Brazilian archaeologist, thinks it likely that the letters are genuinely Phoenician.” After writing about the “tragicomic chapter in recent research about Atlantis” (“Olaus Rudbeck rediscovered it in Sweden, Bartoli in Italy, Georg Kaspar Kirchmaier shifted it to South Africa, Sylvan Bailly to Spitsbergen, Delisles de Sales preferred the Caucasian-Armenian highlands, Baer suggested Asia Minor, Balch Crete, Godron, Elgee, and later Count Byron de Prorok were certain it was in the oasis of Hoggar, and Leo Frobenius chose Yorubaland”), Muck introduces his own theory, wilder than any of them. He says that where the Gulf Stream intersects with the Atlantic Ridge, there is a vast submerged island that precisely conforms to Plato’s description of Atlantis as “larger than Asia and Libya together.” Based on the “mean of eight geological estimates,” Muck estimates that this island—which he calls “Barrier Island X”—sank about ten thousand years ago, which also coincides with Plato’s description. And since this took place outside the Pillars of Hercules—where the Azores are today—there is no question in Muck’s mind: Atlantis has been found.

Otto Muck examines the geological evidence and concludes that Alfred Wegener was right about the fit of South America and Africa, but wrong about North America and Europe. In fact, he says, Wegener was so mistaken about the North Atlantic that there is plenty of room for a whole—albeit small—continent. “Every true cataclysm has a center,” writes Muck, and this one is no exception. At a depth of about 23,000 feet near the Puerto Rican Plateau, there are two great impact craters that (says Muck) were caused by the arrival of an asteroid—“worlds in collision” again. When this celestial body smashed into the earth, causing a gigantic rift to open on the floor of the Atlantic, and to the accompaniment of great waves and clouds of asphyxiating gases, a 400,000-square-mile island (approximately the acreage of Peru), inhabited by a red-skinned people, sank into the middle of the Atlantic. To support his thesis, Muck mentions the German Meteor expedition, which collected data in the Atlantic in 1925: “Did anyone on the survey ship realize what it was they were hearing?” he asks. “Those highly sensitive microphones … were recording something very mysterious, very strange—echoes of a world drowned long ago, echoes from Atlantis. Those sound impulses from a Behm transmitter were the first call for 12,000 years by living men of the forgotten island beneath the waters of the Atlantic.” He then resorts to a painstaking examination of Mayan astronomical records, which enables him to “determine the exact day on which Atlantis perished and even the approximate hour when the catastrophe began.” On June 5, 8498 B.C., at 8:00 p.m., there occurred “the most terrible event that has ever taken place in all the dramatic history of mankind”: the sinking of Atlantis—exactly where and when Plato said it sank, but with some causal modifications that the Greek philosopher might not have understood.

One of the more unusual solutions to the problem of Atlantis was proposed in 1979 by another German, a clergyman named Jürgen Spanuth. He had published an earlier study in 1965 (Atlantis), and his later book, called Atlantis of the North, “restates the conclusions of my earlier researches and adds the new evidence that has accumulated over more than a decade.” Spanuth recognizes that the “key to the riddle of Atlantis” lies not in finding where it might have been, or when it sank into the sea, but, rather, in the identification of the original records that Solon mentions, which he believes are Egyptian temple inscriptions and papyrus texts. To the problem of dating Plato’s story, Spanuth provides a most inventive solution, easily on a par with Galanopoulos’s downward revision of Plato’s numbers by an order of magnitude. Spanuth simply decides that “the Egyptians reckon a month as a year,” an adjustment he attributes to Diodorus Siculus. Thus, he writes, “if the 9,000 or 8,000 ‘years’ of the Atlantis story are converted into the moon-months of the Egyptian calendar—a year has 13 months—then we arrive at a period between 1252 and 1175 B.C., precisely the time during which all those events of which the Egyptian priests told Solon did in fact occur.”

The Atlanteans, says Spanuth, came not from the Mediterranean but from the North Sea, demonstrable by the presence of figures with horned helmets in the Egyptian “Medinet Habu” inscription which resemble Danish helmets from 1200 B.C.* According to Spanuth’s reading, Plato’s description of Atlantis could apply to no other location than “the area between Heligoland and the mainland at Eiderstedt.” (Heligoland—also spelled “Helgoland”—is an island in the North Sea off the coast of Schleswig-Holstein which has been greatly reduced in area because of wave action and erosion.) In precise detail, Pastor Spanuth points out every correlation between Heligoland and Plato’s Atlantis, including the island of Basileia that sank into the sea, the red cliffs, the copper mines, and even the mysterious “orichalc,” which Spanuth identifies as amber. (He says that this is another “mistranslation,” like the one that substituted “year” for the lunar month.) The impenetrable mud that Plato says “made the sea impassable to navigation” is identified as the sandbanks that were left behind when the island of Basileia disappeared, and although Spanuth writes that the Temple of Poseidon described by Plato “sounds so improbable that one might be tempted to assign it to the realm of fantasy,” the “almost incredible wealth of decoration in gold, silver and amber, found in Germanic temples [of pre-Christian times]” demonstrates that Plato was describing a real edifice that had been on Heligoland.