CONCEPT 21

Whipped Egg Whites Need Stabilizers

One of the greatest feats of culinary magic is taking a few egg whites and whipping them into a billowy mound of cloudlike foam that fills the entire bowl. A range of recipes—from soufflés to angel food cake to lemon meringue pie—rely on whipped egg whites. How does beating transform a few tablespoons of liquid into several cups of foam? Let’s find out.

HOW THE SCIENCE WORKS

Egg whites are different from egg yolks, and while we mix the two together for scrambled eggs, omelets, and many baked desserts, we just as often split them up and use each separately. Sometimes we need just the yolks, such as for ice cream, which is dense and rich, but here we explore using the whites alone.

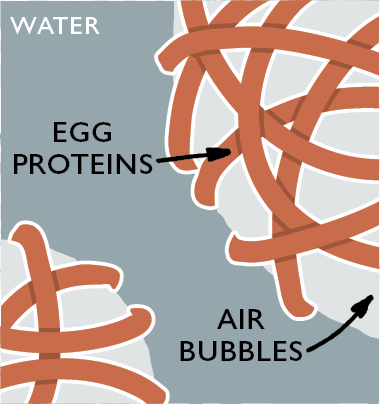

The most common way to use egg whites is to beat them, changing their structure from a liquid to a voluminous foam. As an egg white is beaten, its proteins unfold and bond to create a meshlike network that coats and reinforces the surface of the air bubbles produced in a sea of water (remember, egg whites are composed of about 90 percent water). These unfurled proteins actually increase the viscosity of the water immediately surrounding the air bubbles, enhancing their stability. As the whites are beaten further, more air bubbles form and more proteins bond to coat and reinforce them. Eventually the whole mix will puff up and take on the firm texture of shaving cream. The trick here is to neither underbeat the whites (the mixture will not be stable) nor overbeat them (the foam will become too rigid and will rupture, squeezing out the liquid contained in the whites).

Though this seems simple, things can easily go astray. If any fats, oils, or emulsifiers (for example, a bit of the yolk) get in the mix they can compromise the success of an egg-white foam, because these substances will coat the proteins, preventing them from unfolding and bonding. Fats and oils also take up valuable space on the surface of the air bubbles created when whipping egg whites, which disrupts and weakens the network of protective proteins, causing the foam to collapse very quickly and resulting in a soggy, deflated mass.

As a rule, whipped egg-white foams are temporary things. Whether the foam is raw or cooked, the water surrounding the air bubbles will eventually succumb to the force of gravity and begin to drain away, causing the foam to separate and release its liquid. Our goal is to delay this as long as possible.

We’ve seen the role of starch when it comes to stabilizing fully cooked eggs and preventing a curdled mess (concept 20). But when we isolate and whip egg whites, a different kind of stabilization is called for. Two ingredients help.

The first is sugar, which slows the drainage of moisture from the film surrounding the air bubbles in egg foams, helping the whites to remain stable as well as achieve maximum volume. Here, the timing is key.

In the early stage of whipping, the proteins have not completely unfurled and linked together, so the air bubbles that ultimately give the foam its volume can’t hold a firm shape. Sugar, however, interferes with the ability of proteins to cross-link. If it’s added too early, fewer proteins will bond and trap air, resulting in a foam that is less voluminous. If, on the other hand, you beat the egg whites until they are very thick and dense, the sugar added at this stage will have less water to dissolve in, giving the finished meringue a gritty texture and a tendency to form drops of sugar syrup during baking. The key is to add sugar only when the whites have been whipped enough to gain some volume but still have enough free water left in them to dissolve the sugar completely. The right moment? Just before the soft peak stage, when the foam is frothy and bubbly but not quite firm enough to hold a peak.

The second stabilizing ingredient is cream of tartar, an acid that alters the electric charge on the proteins of the egg whites, in turn reducing the interactions between protein molecules. Because this delays the formation of the foam, whipping takes longer but also results in a much more stable foam.

TEST KITCHEN EXPERIMENT

To demonstrate the effects of adding cream of tartar to egg whites when whipping them to stiff peaks, we devised the following test: We beat eight batches of four egg whites in a stand mixer (starting on low speed to unravel the egg proteins and finishing on high to incorporate significant air) until they achieved stiff peaks. In half the batches we included ¼ teaspoon of cream of tartar before whipping, while the others were left plain. We transferred the fluffy eggs to funnels set over beakers and collected exuded water for 60 minutes, long enough to see significant results.

THE RESULTS

The whites whipped without any stabilizers lost 23 mL of liquid on average. The whites stabilized with cream of tartar lost less than half that amount, about 10 mL on average.

THE TAKEAWAY

While our egg foams made with and without a stabilizer did not look different—both were light and fluffy foams holding stiff peaks—they released a drastically different amount of liquid with time. Why is this important? Beating air into egg whites transforms them from a liquid to a foam. But whipped egg whites can revert, at least partially, to their liquid state over time. This is what is happening when the meringue topping on a pie “weeps”—the egg foam is breaking down and becoming soft and wet.

The addition of cream of tartar changed the electric charges of the egg-white proteins, delaying their ability to link together and therefore creating a stronger network around the air bubbles of the foam. This stronger network is better able to withstand gravity and hold moisture within. Keeping whipped egg whites stable is important in a variety of recipes. If your egg whites are not stabilized (with cream of tartar or sugar), they can lose a large amount of liquid while baking, causing gritty, weepy meringues or baked goods that deflate disastrously in the oven.

STABILIZING EGG WHITES AT WORK

SUGAR

The addition of sugar stabilizes whipped egg whites in two ways. First, it slows the unfolding of egg proteins, delaying the formation of foam and protecting against overwhipping. Second, sugar dissolves in the liquid surrounding the air bubbles in an egg foam, forming a thick and viscous syrup that is slow to drain. (If the liquid drains too quickly, the air bubbles, and therefore the foam, will collapse.) Here, we look at the stabilizing effect of sugar when used alone in our Meringue Cookies and when combined with other ingredients in our Bittersweet Chocolate Mousse Cake.

MERINGUE COOKIES

MAKES ABOUT 48 SMALL COOKIES

Meringues may be a little soft immediately after being removed from the oven but will stiffen as they cool. To minimize stickiness on humid or rainy days, allow the meringues to cool in a turned-off oven for an additional hour (for a total of two hours) without opening the door, then transfer them immediately to airtight containers and seal.

|

¾

|

cup (5¼ ounces) sugar

|

|

2

|

teaspoons cornstarch

|

|

4

|

large egg whites

|

|

¾

|

teaspoon vanilla extract

|

|

1⁄8

|

teaspoon salt

|

1. Adjust oven racks to upper-middle and lower-middle positions and heat oven to 225 degrees. Line 2 baking sheets with parchment paper. Combine sugar and cornstarch in small bowl.

2. Using stand mixer fitted with whisk, beat egg whites, vanilla, and salt together on high speed until very soft peaks start to form (peaks should slowly lose their shape when whisk is removed), 30 to 45 seconds. Reduce speed to medium and slowly add sugar mixture in steady stream down side of mixer bowl (process should take about 30 seconds). Stop mixer and scrape down bowl. Increase speed to high and beat until glossy and stiff peaks have formed, 30 to 45 seconds.

3. Working quickly, place meringue in pastry bag fitted with ½-inch plain tip or large zipper-lock bag with ½ inch of corner cut off. Pipe meringues into 1¼-inch-wide mounds about 1 inch high on baking sheets, 6 rows of 4 meringues on each sheet. Bake for 1 hour, switching and rotating baking sheets halfway through baking. Turn off oven and let meringues cool in oven for at least 1 hour. Remove meringues from oven, immediately transfer from baking sheet to wire rack, and let cool to room temperature. (Meringues can be stored in airtight container for up to 2 weeks.)

CHOCOLATE MERINGUE COOKIES

Gently fold 2 ounces finely chopped bittersweet chocolate into meringue mixture at end of step 2.

TOASTED ALMOND MERINGUE COOKIES

Substitute ½ teaspoon almond extract for vanilla extract. In step 3, sprinkle meringues with 1⁄3 cup coarsely chopped toasted almonds and 1 teaspoon coarse sea salt (optional) before baking.

ORANGE MERINGUE COOKIES

Stir 1 teaspoon grated orange zest into sugar mixture in step 1.

ESPRESSO MERINGUE COOKIES

Stir 2 teaspoons instant espresso powder into sugar mixture in step 1.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

A classic meringue cookie may have only two basic ingredients—egg whites and sugar—but it requires precise timing. Otherwise, you’ll end up with a meringue that’s as dense as Styrofoam or weepy, gritty, and cloyingly sweet. A great meringue cookie should emerge from the oven glossy and white, with a shatteringly crisp texture that dissolves instantly in your mouth. The key to glossy, evenly textured meringue is adding the sugar at just the right time—when the whites have been whipped enough to gain some volume and strength but still have enough free water left in them for the sugar to dissolve completely. Surprisingly, we find that cream of tartar is not necessary here. The sugar and cornstarch are stabilizers enough.

PICK FRANCE There are three types of meringue: Italian, in which a hot sugar syrup is poured into the egg whites as they are beaten; Swiss, which heats the whites with the sugar; and French, in which egg whites are whipped with sugar alone. For this recipe, French is best. We find that it’s the simplest of the meringues, and we prefer the results in comparison, for example, to the dense and candylike cookies made by the Italian method.

ADD SUGAR Pay attention to your egg whites as you beat them. You don’t want to add the sugar too early, when it will interfere with the cross-linking proteins, or too late, when there isn’t enough water in which the sugar can dissolve, resulting in a gritty, weeping meringue. Add the sugar just before the soft peak stage, when the whites have gained some volume but still have enough water for the sugar to dissolve. Adding the sugar in a slow stream down the side of the bowl of a running stand mixer helps distribute the sugar more evenly, which creates a smoother meringue.

USE CORNSTARCH When tasting traditional recipes, we found the majority of them to be too sweet. But when we cut back on the amount of sugar, it produced disastrous results. The meringues with less sugar started collapsing and shrinking in the oven. Why? Turns out sugar stabilizes in both the mixing bowl and the oven. Without sufficient sugar, the meringues lose moisture too rapidly as they bake, causing them to collapse. We solve this problem with a bit of cornstarch (see “Twin Stabilizers—Sugar and Cornstarch”).

PIPE THE COOKIES To guarantee uniform shape and proper even cooking, it’s essential to pipe the cookies rather than use a spoon. A pastry bag produces perfectly shaped meringues; a zipper-lock bag with a corner cut off works nearly as well.

TURN OFF YOUR OVEN Traditionally, meringues are baked at a low temperature and then left in the turned-off oven, sometimes for as long as overnight. The idea is to completely dry out the cookies while allowing them to remain snow white. We tried baking ours at 175 degrees, but our ovens had trouble maintaining this temperature. An hour in a 225-degree oven followed by another hour in the turned-off oven produces perfectly cooked meringues every time.

BITTERSWEET CHOCOLATE MOUSSE CAKE

MAKES ONE 9-INCH CAKE, SERVING 12 TO 16

If the sugar is lumpy you should crumble it with grease-free fingers. Any residual fat from butter or chocolate might hinder the whipping of the whites. If you like, dust the cake with confectioners’ sugar just before serving or top slices with a dollop of lightly sweetened whipped cream.

|

12

|

tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into 12 pieces

|

|

12

|

ounces bittersweet chocolate, chopped

|

|

1

|

ounce unsweetened chocolate, chopped

|

|

8

|

large eggs, separated

|

|

1

|

tablespoon vanilla extract

|

|

1⁄8

|

teaspoon salt

|

|

2⁄3

|

cup packed (42⁄3 ounces) light brown sugar

|

1. Adjust oven rack to lower-middle position and heat oven to 325 degrees. Grease 9-inch springform pan, line with parchment paper, grease parchment, and flour pan. Wrap bottom and sides of pan with large sheet of aluminum foil.

2. Melt butter and chocolates in large heatproof bowl set over saucepan filled with 2 quarts barely simmering water, stirring occasionally, until smooth. Remove from heat and let mixture cool slightly, then whisk in egg yolks and vanilla. Set chocolate mixture aside, reserving hot water, covered, in saucepan.

3. Using stand mixer fitted with whisk, whip egg whites and salt on medium speed until frothy, about 30 seconds. Add 1⁄3 cup sugar, increase speed to high, and whip until combined, about 30 seconds. Add remaining 1⁄3 cup sugar and continue to whip until soft peaks form when whisk is lifted, about 2 minutes longer. Using whisk, stir about one-third of beaten egg whites into chocolate mixture to lighten it, then fold in remaining egg whites in 2 additions using whisk. Gently scrape batter into prepared springform pan, set pan in large roasting pan, then pour hot water from saucepan into roasting pan to depth of 1 inch. Carefully slide roasting pan into oven and bake until cake has risen, is firm around edges, center has just set, and center registers about 170 degrees, 45 to 55 minutes.

4. Remove springform pan from water bath, discard foil, and let cool on wire rack for 10 minutes. Run thin-bladed paring knife between sides of pan and cake to loosen; let cake cool in pan on wire rack until barely warm, about 3 hours, then wrap pan in plastic wrap and refrigerate until thoroughly chilled, at least 8 hours. (Cake can be refrigerated for up to 2 days.)

5. To unmold cake, remove sides of pan. Slide thin metal spatula between cake and pan bottom to loosen, then invert cake onto large plate, peel off parchment, and reinvert onto serving platter. To serve, use sharp, thin-bladed knife, dipping knife in pitcher of hot water and wiping blade before each cut.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

This recipe combines the techniques of using sugar to stabilize the egg whites and a water bath to cook the cake gently and evenly (see concept 19). It’s important to whip the egg whites well before folding them into the chocolate mixture. The Bittersweet Chocolate Mousse Cake is nothing without stable, voluminous egg whites.

PREPARE THE PAN To keep the cake from sticking, be sure to butter, flour, and then line the bottom of the springform pan with parchment paper. We also wrap the outside of the pan with foil to prevent leakage when in the water bath. (See “Leak-Proofing Springform Pans” for an alternative to wrapping the pan in foil.)

USE LOTS OF YOLKS Butter and egg yolks are the ingredients that give this cake its melt-in-your-mouth texture. Twelve tablespoons is the perfect amount of butter. Any more makes the cake unpalatably greasy; less makes it dry. As for the egg yolks, we made cakes using as few as four and as many as 10. The 10-yolk version remained a little too damp in the middle, even when thoroughly baked. Eight is the magic number.

PICK BROWN SUGAR When we tried using light brown sugar rather than granulated, we knew we were on to something good. The flavor was fabulous, with just the right amount of sweetness and a tiny hint of smokiness from the molasses. Brown sugar offers an additional bonus, too: The molasses in brown sugar is slightly acidic, eliminating the need for cream of tartar (another acid) to stabilize the egg whites. When beaten together, the whites and brown sugar turn into a glossy, perfect meringue.

FOLD IN THE FOAM After beating the egg whites, we fold them into the batter for our cake. But if the meringue is not the proper consistency, this can be problematic. Delicate egg whites beaten with nothing added to them will collapse under the weight of the chocolate, giving the cake a dense, bricklike structure. Beating the egg whites further, until they are almost rigid, will just make the cake unappealingly dry. Beating them less will only make the cake more dense. But adding the sugar to the egg whites as they are being beaten will create a thicker, more stable egg foam. This method will produce a creamy meringue that holds up well when folded into the chocolate mixture, creating a baked mousse cake that is moist, rich, and creamy. Because the egg whites are only beaten to soft peaks—and no further—we add the sugar a bit earlier in the process, as compared to recipes where egg whites are beaten to stiff peaks. We use a similar technique in our Angel Food Cake recipe.

BAKE IN A WATER BATH Baking the mousse cake on its own in an oven set to the standard temperature for cakes (350 degrees) turns it into a giant mushroom that collapses after cooking. A more gentle heat level (300 degrees) causes the outside of the cake to be overdone while the center remains raw. The solution? A water bath. A mousse cake baked in a water bath in a 325-degree oven rises evenly and has a velvety, creamy texture throughout. The extra step is worth the effort.

STABILIZING EGG WHITES AT WORK

CREAM OF TARTAR

Cream of tartar, also known as potassium bitartrate, or potassium acid tartrate, is a powdered byproduct of the winemaking process and, along with baking soda, is one of the two main ingredients in baking powder. Cream of tartar’s acidic nature lowers the pH of egg whites, altering the electric charge on the proteins and encouraging them to unfold, thus creating more volume, greater stability, and a glossier appearance. We use it here to help stabilize egg whites in pies, cakes, and soufflés.

LEMON MERINGUE PIE

SERVES 8

For the best flavor, use freshly squeezed lemon juice; don’t use bottled lemon juice. Be sure that the filling is cool when spreading the meringue onto the pie. This pie should be served the same day that it is prepared.

|

FILLING

|

|

1½

|

cups water

|

|

1

|

cup (7 ounces) sugar

|

|

¼

|

cup cornstarch

|

|

1⁄8

|

teaspoon salt

|

|

6

|

large egg yolks

|

|

1

|

tablespoon grated lemon zest plus ½ cup juice (3 lemons)

|

|

2

|

tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into 2 pieces

|

|

MERINGUE

|

|

¾

|

cup (5¼ ounces) sugar

|

|

1⁄3

|

cup water

|

|

3

|

large egg whites

|

|

¼

|

teaspoon cream of tartar

|

|

|

Pinch salt

|

|

¼

|

teaspoon vanilla extract

|

1. FOR THE FILLING: Bring water, sugar, cornstarch, and salt to simmer in large saucepan over medium heat, whisking constantly. When mixture starts to turn translucent, whisk in egg yolks, 2 at a time. Whisk in lemon zest and juice and butter. Return mixture to brief simmer, then remove from heat.

2. Pour filling into baked and cooled pie crust. Lay sheet of plastic wrap directly on surface of filling and refrigerate pie until filling is cold, about 2 hours.

3. FOR THE MERINGUE: Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 400 degrees. Bring sugar and water to vigorous boil in small saucepan over medium-high heat. Once syrup comes to rolling boil, cook for 4 minutes (mixture will become slightly thickened and syrupy). Remove from heat and set aside while beating whites.

4. Using stand mixer fitted with whisk, whip whites, cream of tartar, and salt on medium-low speed until foamy, about 1 minute. Increase speed to medium-high and whip until soft peaks form, about 2 minutes. With mixer running, slowly pour hot syrup into whites (avoid pouring syrup onto whisk or it will splash). Add vanilla and beat until meringue has cooled and becomes very thick and shiny, 3 to 6 minutes.

5. Using rubber spatula, mound meringue over filling, making sure meringue touches edges of crust. Use spatula to create peaks all over meringue. Bake until peaks turn golden brown, about 6 minutes. Transfer to wire rack and let cool to room temperature. Serve.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

We wanted our Lemon Meringue Pie recipe to produce a tall and fluffy topping, so we make the meringue with a hot sugar syrup and add a bit of cream of tartar to the egg whites before beating them. This technique ensures that the meringue is cooked through and stable enough to be piled high on top of the filling.

ADD GRAHAM CRACKERS TO CRUST To promote browning and really crisp the crust, we roll our Foolproof Single-Crust Pie Dough for Custard Pies in graham cracker crumbs. Not only does this help the texture of our crust, but it adds a wonderful graham flavor to complement the lemon pie without masking the character of the dough itself. It’s important to note that the crust is fully baked and cooled before it is filled and chilled.

MAKE THE RIGHT FILLING The filling for our Lemon Meringue Pie is a close relative of Lemon Curd, but because you need so much more of it to fill a pie shell it’s diluted with water (all lemon juice would be too intense) and stabilized with cornstarch (so you can slice cleanly through the thick filling).

PICK ITALIAN Rather than simply beating egg whites with raw sugar (the French method), here we pour hot sugar syrup into the whites as they are beaten (the Italian method). The hot syrup cooks the whites and helps transform them into a soft, smooth meringue that is stable enough to resist weeping during its short time in the oven. With a French meringue, the bottom portion often doesn’t cook through and weeping is a greater risk.

BAKE, DON’T BROIL While some recipes throw the pie under the broiler, a hot oven greatly reduces the risk of burning the meringue.

ANGEL FOOD CAKE

SERVES 10 TO 12

Do not use all-purpose flour. Our tasters unflatteringly compared a cake made with it to Wonder Bread. If your angel food cake pan does not have a removable bottom, line the bottom of the pan with parchment paper. In either case, do not grease the pan (or the paper).

|

1

|

cup plus 2 tablespoons (4½ ounces) cake flour

|

|

¼

|

teaspoon salt

|

|

1¾

|

cups (12¼ ounces) sugar

|

|

12

|

large egg whites

|

|

1½

|

teaspoons cream of tartar

|

|

1

|

teaspoon vanilla extract

|

1. Adjust oven rack to lower-middle position and heat oven to 325 degrees. Whisk flour and salt together in bowl. Process sugar in food processor until fine and powdery, about 1 minute. Reserve half of sugar in small bowl. Add flour mixture to food processor with remaining sugar and process until aerated, about 1 minute.

2. Using stand mixer fitted with whisk, whip egg whites and cream of tartar on medium-low speed until foamy, about 1 minute. Increase speed to medium-high, slowly add reserved sugar, and whip until soft peaks form, about 6 minutes. Add vanilla and mix until incorporated.

3. Sift flour mixture over egg whites in 3 additions, folding gently with rubber spatula after each addition until incorporated. Scrape mixture into ungreased 12-cup tube pan.

4. Bake until toothpick inserted in center comes out clean and cracks in cake appear dry, 40 to 45 minutes. Let cake cool completely in pan, upside down, about 3 hours. Run knife around edge of cake to loosen, then gently tap pan upside down on counter to release cake. Turn cake right side up onto platter and serve.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Unlike other cakes, angel food cake uses no oil or butter—you don’t even grease the cake pan. It doesn’t call for baking soda or baking powder, either, relying solely on beaten egg whites for its dramatic height. To make angel food cake, you whip egg whites with sugar and cream of tartar—stabilizing ingredients, as we know—until soft peaks form, fold in flour and flavorings, and bake.

GRIND SUGAR EXTRA-FINE Granulated or confectioners’ sugar will make acceptable but somewhat heavy cakes. For an extraordinary angel food cake, process granulated sugar in the food processor until powdery. It will dissolve much faster, so it won’t deflate the egg whites.

KEEP YOLKS AT BAY We stirred ½ teaspoon of egg yolk into a dozen whites, just to see what would happen. The eggs turned white and frothy with whipping, but even after 25 minutes, they failed to form peaks. Lesson learned: Separate eggs with care.

FLUFF WITH FLOUR Some recipes call for sifting the flour and/or sugar as many as eight times. What a pain! We tried skipping sifting altogether, but the resulting cake was squat. Ultimately, we figured out that by processing the flour (with half the sugar) in the food processor to aerate it, we could get away with sifting just once.

FOLD GENTLY Use a rubber spatula to gently turn or “fold” the flour and egg whites over one another until they are thoroughly combined. Add the flour in three batches so you don’t deflate the whites.

COOL UPSIDE DOWN Invert the cooked cake until it is completely cool, about 3 hours. If you don’t have a pan with feet, invert it over the neck of a bottle. Angel food cakes cooled right side up can be crushed by their own weight.

GRAND MARNIER SOUFFLÉ WITH GRATED CHOCOLATE

SERVES 6 TO 8

Make the soufflé base and immediately begin beating the whites before the base cools too much. Once the whites have reached the proper consistency, they must be used at once. Do not open the oven door during the first 15 minutes of baking time; as the soufflé nears the end of its baking, you may check its progress by opening the oven door slightly. (Be careful; if your oven runs hot, the top of the soufflé may burn.) Confectioners’ sugar is a nice finishing touch, but be ready to serve the soufflé immediately.

|

3

|

tablespoons unsalted butter, softened

|

|

¾

|

cup (5¼ ounces) sugar

|

|

2

|

teaspoons sifted cocoa

|

|

5

|

tablespoons (1½ ounces) all-purpose flour

|

|

¼

|

teaspoon salt

|

|

1

|

cup whole milk

|

|

5

|

large eggs, separated

|

|

3

|

tablespoons Grand Marnier

|

|

1

|

tablespoon grated orange zest

|

|

1⁄8

|

teaspoon cream of tartar

|

|

½

|

ounce bittersweet chocolate, finely grated

|

1. Adjust oven rack to upper-middle position and heat oven to 400 degrees. Grease 1½-quart soufflé dish with 1 tablespoon butter. Combine ¼ cup sugar and cocoa in small bowl and pour into prepared dish, shaking to coat bottom and sides of dish evenly. Tap out excess and set dish aside.

2. Whisk flour, ¼ cup sugar, and salt together in small saucepan. Gradually whisk in milk, whisking until smooth and no lumps remain. Bring mixture to boil over high heat, whisking constantly, until thickened and mixture pulls away from sides of pan, about 3 minutes. Scrape mixture into medium bowl; whisk in remaining 2 tablespoons butter until combined. Whisk in egg yolks until incorporated; stir in Grand Marnier and orange zest.

3. Using stand mixer fitted with whisk, whip egg whites, cream of tartar, and 1 teaspoon sugar on medium-low speed until foamy, about 1 minute. Increase speed to medium-high and whip whites to soft, billowy mounds, about 1 minute. Gradually add half of remaining sugar and whip until glossy, soft peaks form, about 30 seconds; with mixer still running, add remaining sugar and whip until just combined, about 10 seconds.

4. Using rubber spatula, immediately stir one-quarter of whipped whites into soufflé base to lighten until almost no white streaks remain. Scrape remaining whites into base and fold in whites, along with grated chocolate, with whisk until mixture is just combined. Gently pour mixture into prepared dish and run your index finger, about ½ inch from side of dish, through mixture, tracing circumference to help soufflé rise properly. Bake until surface of soufflé is deep brown, center jiggles slightly when shaken, and soufflé has risen 2 to 2½ inches above rim, 20 to 25 minutes. Serve immediately.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

We wanted our Grand Marnier Soufflé to be airy and light, yet still taste creamy. Knowing the finicky reputation of soufflés, we wanted it to be reliable, too. Because of the soufflé’s airy texture, we knew that we needed to increase its stability. We found that building the soufflé base on a bouillie (a paste made from flour and milk), enhanced with butter and egg yolks, gives us the richness we wanted without harming the soufflé’s texture. And no surprise here: Whipping the egg whites with both cream of tartar and granulated sugar serves to enhance the soufflé’s stability.

MAKE A BASE The base for this soufflé, into which the beaten egg whites are eventually folded, provides flavor and additional moisture to help it all rise. We prepared a blind taste test with three different base options: béchamel, a classic French sauce made with butter, flour, and milk; pastry cream; and bouillie, a paste made from flour and milk. The bouillie soufflé had the creamiest, richest texture.

WHIP IT RIGHT The technique used to beat egg whites is crucial to a successful soufflé. The objective is to create a strong, stable foam that rises well and is not prone to collapse during either folding or baking. As we’ve learned, adding sugar to the egg whites as they are whipped enhances their stability. This makes them more resilient to a heavy hand during the folding and less apt to fall quickly after being pulled from the oven. Most of the sugar must be added after the eggs have become foamy and should be added gradually. If it’s added all at once, the soufflé will be uneven, with a shorter rise, and a bit of an overly sweet taste. Don’t forget the cream of tartar; it makes for a more stable soufflé with a bigger rise.

FOLD IT OVER When combining the voluminous whipped egg whites with the dense batter, vigorous stirring will get you nowhere, quick. The technique we use is called folding. The goal is to incorporate the light egg whites with the heavy batter without deflating the foam.

GIVE A QUICK SWIPE Our Grand Marnier Soufflé relies on little beyond eggs, milk, and a little flour for structure and benefits from the following technique: After pouring the batter into the dish, trace a circle in the batter with your finger, ½ inch from the edge of the dish. This breaks the surface tension and helps the ultra-light soufflé achieve a high, even rise.

DO NOT OVERCOOK Most important: Never overcook a soufflé. It should be very creamy in the middle and firm around the outside, almost like a pudding cake. Don’t wait until the center is completely solid; it will be too late. The center should not be liquid-y, but it should still be quite loose and very moist. Once you can smell a soufflé baking in the oven, it’s about ready to come out.