WATER BATH AT WORK

CHEESECAKE AND CUSTARD

We use water baths in order to cook delicate custards and custardy cakes slowly and evenly throughout. After all, the water in a water bath never reaches more than 212 degrees. We nestle the ramekins or cake pan in the bath (so that the water comes at least halfway up its sides) in order to moderate the temperature around the perimeter and prevent overcooking around the edge.

SPICED PUMPKIN CHEESECAKE

SERVES 12 TO 16

This cheesecake is good on its own, but either Brown Sugar Whipped Cream or Brown Sugar and Bourbon Whipped Cream (recipes follow) is a great addition. When cutting the cake, have a pitcher of hot tap water nearby; dipping the blade of the knife into the water and wiping it clean with a kitchen towel after each cut helps make neat slices.

|

CRUST

|

|

9

|

whole graham crackers, broken into rough pieces

|

|

3

|

tablespoons sugar

|

|

½

|

teaspoon ground ginger

|

|

½

|

teaspoon ground cinnamon

|

|

¼

|

teaspoon ground cloves

|

|

6

|

tablespoons unsalted butter, melted

|

|

FILLING

|

|

11⁄3

|

cups (91⁄3 ounces) sugar

|

|

1

|

teaspoon ground cinnamon

|

|

½

|

teaspoon ground ginger

|

|

¼

|

teaspoon ground nutmeg

|

|

¼

|

teaspoon ground cloves

|

|

¼

|

teaspoon ground allspice

|

|

½

|

teaspoon salt

|

|

1

|

(15-ounce) can unsweetened pumpkin puree

|

|

1½

|

pounds cream cheese, cut into 1-inch chunks and softened

|

|

1

|

tablespoon vanilla extract

|

|

1

|

tablespoon lemon juice

|

|

5

|

large eggs, room temperature

|

|

1

|

cup heavy cream

|

|

1

|

tablespoon unsalted butter, melted

|

1. FOR THE CRUST: Adjust oven rack to lower-middle position and heat oven to 325 degrees. Pulse crackers, sugar, ginger, cinnamon, and cloves in food processor until crackers are finely ground, about 15 pulses. Transfer crumbs to medium bowl, drizzle with melted butter, and mix with rubber spatula until evenly moistened. Empty crumbs into 9-inch springform pan and, using bottom of ramekin or dry measuring cup, press crumbs firmly and evenly into pan bottom, keeping sides as clean as possible. Bake crust until fragrant and browned around edges, about 15 minutes. Let crust cool completely on wire rack, about 30 minutes. When cool, wrap outside of pan with two 18-inch square pieces of heavy-duty aluminum foil and set springform pan in roasting pan. Bring kettle of water to boil.

2. FOR THE FILLING: Whisk sugar, cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, cloves, allspice, and salt together in small bowl; set aside. Line baking sheet with triple layer of paper towels. Spread pumpkin on paper towels in roughly even layer and pat puree with several layers of paper towels to wick away moisture.

3. Using stand mixer fitted with paddle, beat cream cheese on medium speed until broken up and slightly softened, about 1 minute. Scrape down bowl, then beat in sugar mixture in 3 additions on medium-low speed until combined, about 1 minute, scraping down bowl after each addition. Add pumpkin, vanilla, and lemon juice and beat on medium speed until combined, about 45 seconds; scrape down bowl. Reduce speed to medium-low, add eggs, 1 at a time, and beat until incorporated, about 1 minute. Reduce speed to low, add cream, and beat until combined, about 45 seconds. Give filling final stir by hand.

4. Being careful not to disturb baked crust, brush inside of pan with melted butter. Pour filling into prepared pan and smooth top with rubber spatula. Set roasting pan on oven rack and pour enough boiling water into roasting pan to come about halfway up sides of springform pan. Bake cake until center is slightly wobbly when pan is shaken and cake registers 150 degrees, about 1½ hours. Set roasting pan on wire rack, then run paring knife around cake. Let cake cool in roasting pan until water is just warm, about 45 minutes. Remove springform pan from water bath, discard foil, and set on wire rack; continue to let cool until barely warm, about 3 hours. Wrap with plastic wrap and refrigerate until chilled, at least 4 hours.

5. To unmold cheesecake, wrap hot kitchen towel around pan and let stand for 1 minute. Remove sides of pan. Slide thin metal spatula between crust and pan bottom to loosen, then slide cake onto serving platter. Let cheesecake sit at room temperature for about 30 minutes before serving. (Cake can be made up to 3 days in advance; however, crust will begin to lose its crispness after only 1 day.)

PUMPKIN-BOURBON CHEESECAKE WITH GRAHAM-PECAN CRUST

Reduce graham crackers to 5 whole crackers, process ½ cup chopped pecans with crackers, and reduce butter to 4 tablespoons. In filling, omit lemon juice, reduce vanilla extract to 1 teaspoon, and add ¼ cup bourbon along with heavy cream.

BROWN SUGAR WHIPPED CREAM

MAKES ABOUT 2½ CUPS

Refrigerating the mixture in step 1 gives the brown sugar time to dissolve. This whipped cream pairs well with Spiced Pumpkin Cheesecake or with any dessert that has lots of nuts, warm spices, or molasses, like gingerbread, pecan pie, or pumpkin pie.

|

1

|

cup heavy cream, chilled

|

|

½

|

cup sour cream

|

|

½

|

cup packed (3½ ounces) light brown sugar

|

|

1⁄8

|

teaspoon salt

|

1. Using stand mixer fitted with whisk, whip heavy cream, sour cream, sugar, and salt until combined. Cover with plastic wrap and refrigerate until ready to serve, at least 4 hours or up to 1 day, stirring once or twice during chilling to ensure that sugar dissolves.

2. Before serving, using stand mixer fitted with whisk, whip mixture on medium-low speed until foamy, about 1 minute. Increase speed to high and whip until soft peaks form, 1 to 3 minutes.

BROWN SUGAR AND BOURBON WHIPPED CREAM

Add 2 teaspoons bourbon to cream mixture before whipping.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Adding pumpkin, with all of its extra liquid, to a cheesecake makes everything more challenging. An unusual method to remove moisture from pumpkin (which includes paper towels) and the use of a water bath ensure that our Spiced Pumpkin Cheesecake has a velvety texture.

PREBAKE THE CRUST We use crumbled graham crackers for the crust, as we do in our New York–Style Cheesecake recipe. Here we add butter and sugar and a bit of ground cinnamon and ginger to them in order to complement the spices in the filling. Also, as with our New York cheesecake, we prebake the crust. This way a sturdy, crisp, buttery crust forms. (Without prebaking, the crust becomes a pasty, soggy layer beneath the filling.)

DRY YOUR CANNED PUMPKIN Anyone who has prepared fresh pumpkin for pumpkin pie can attest to the fact that cutting, seeding, peeling, and cooking it can take hours and is not time and effort well spent. We prefer opening a can, which takes only a few seconds. But pumpkin in any form is filled with liquid. We could remove some of the moisture by cooking, as we do in our Pumpkin Pie. But that involves frequent stirring, a cooking period, and waiting for it to cool. An easier way? Paper towels. Spread the pumpkin on a baking sheet lined with paper towels and then press additional paper towels on the surface to wick away more moisture. In seconds, the pumpkin will shed enough liquid to yield a cheesecake with a lovely texture, and the paper towels will peel away almost effortlessly. Removing this moisture allows us to add heavy cream to the mix, which gives us a cheesecake that is smooth and lush.

PICK YOUR EGGS While cheesecake recipes can take various amounts of eggs in different configurations (whole eggs, egg whites, or egg yolks for a range of textures), we prefer simply using five whole eggs here. This produces a satiny, creamy, unctuous cheesecake.

FLAVOR IT UP Our Spiced Pumpkin Cheesecake is flavored with lemon juice, salt, and vanilla extract to start. But we also add sweet, warm cinnamon and sharp, spicy ground ginger alongside small amounts of cloves, nutmeg, and allspice. In unison, these spices provide a deep, resounding flavor but not an overspiced burn.

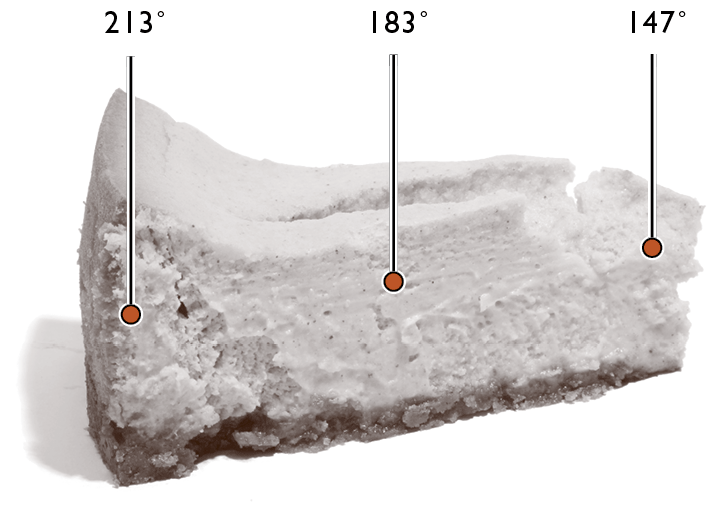

GIVE IT A BATH In a springform pan, a cheesecake can be baked either directly on the oven rack like a regular cake or in a water bath like a delicate custard. Because we bake this cheesecake at 325 degrees, a water bath is needed for even cooking on the edges and the center (for more on this, see Test Kitchen Experiment). For the water bath, the pan must be wrapped in a double layer of foil to prevent leakage (or placed within another pan, see “Leak-Proofing Springform Pans”). The water, which moderates the cooking temperature and protects the edges of the cake, should come halfway up the sides of the springform pan. The extra humidity in the air due to the steaming water helps to reduce the level of evaporation from the cake, for a better, moister cheesecake after it exits the oven.

CRÈME BRÛLÉE

SERVES 8

Separate the eggs and whisk the yolks after the cream has finished steeping; if left to sit, the surface of the yolks will dry and form a film. A vanilla bean gives the custard the deepest flavor, but 2 teaspoons of vanilla extract, whisked into the yolks in step 4, can be used instead. While we prefer turbinado or Demerara sugar for the caramelized sugar crust, regular granulated sugar will work, too, but use only 1 scant teaspoon on each ramekin or 1 teaspoon on each shallow fluted dish.

|

1

|

vanilla bean

|

|

4

|

cups heavy cream

|

|

2⁄3

|

cup (42⁄3 ounces) granulated sugar

|

|

|

Pinch salt

|

|

12

|

large egg yolks

|

|

8–12

|

teaspoons turbinado or Demerara sugar

|

1. Adjust oven rack to lower-middle position and heat oven to 300 degrees.

2. Cut vanilla bean in half lengthwise. Using tip of paring knife, scrape out seeds. Combine vanilla bean and seeds, 2 cups cream, granulated sugar, and salt in medium saucepan. Bring mixture to boil over medium heat, stirring occasionally to dissolve sugar. Off heat, let steep for 15 minutes.

3. Meanwhile, place kitchen towel in bottom of large baking dish or roasting pan; set eight 4- or 5-ounce ramekins (or shallow fluted dishes) on towel (they should not touch each other). Bring kettle of water to boil.

4. After cream has steeped, stir in remaining 2 cups cream. Whisk egg yolks in large bowl until uniform. Whisk about 1 cup cream mixture into yolks until combined; repeat with 1 cup more cream mixture. Add remaining cream mixture and whisk until evenly colored and thoroughly combined. Strain mixture through fine-mesh strainer into large liquid measuring cup or bowl; discard solids in strainer. Divide mixture evenly among ramekins.

5. Set baking dish on oven rack. Taking care not to splash water into ramekins, pour enough boiling water into dish to reach two-thirds up sides of ramekins. Bake until centers of custards are just barely set and register 170 to 175 degrees, 30 to 35 minutes (25 to 30 minutes for shallow fluted dishes), checking temperature about 5 minutes before recommended minimum time.

6. Transfer ramekins to wire rack and let cool to room temperature, about 2 hours. Set ramekins on baking sheet, cover tightly with plastic wrap, and refrigerate until cold, at least 4 hours.

7. Uncover ramekins; if condensation has collected on custards, blot moisture with paper towel. Sprinkle each with about 1 teaspoon turbinado sugar (1½ teaspoons for shallow fluted dishes); tilt and tap each ramekin to distribute sugar evenly, dumping out excess sugar. Ignite torch and caramelize sugar. Refrigerate ramekins, uncovered, to rechill, 30 to 45 minutes; serve.

ESPRESSO CRÈME BRÛLÉE

Crush the espresso beans lightly with the bottom of a skillet.

Substitute ¼ cup lightly crushed espresso beans for vanilla bean. Whisk 1 teaspoon vanilla extract into yolks in step 4 before adding cream.

MAKE-AHEAD CRÈME BRÛLÉE

Reduce egg yolks to 10. After baked custards cool to room temperature, wrap each ramekin tightly in plastic wrap and refrigerate for up to 4 days. Proceed with step 7.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Crème brûlée is all about the contrast between the crisp sugar crust and the silky custard underneath. But too often the crust is either stingy or rock-hard, and the custard is heavy and tasteless. We found that the secret to a soft, supple custard is using egg yolks rather than whole eggs, and a water bath for gentle, even cooking. For the crust, we use crunchy turbinado sugar and a propane or butane torch (which work better than the broiler) for caramelizing the sugar. Because the blast of heat inevitably warms the custard beneath the crust, we chill our crèmes brûlées once more before serving.

START WITH HEAVY CREAM There is no point cutting corners here. We tried this crème brûlée with half-and-half (with a fat content of around 10 percent), whipping cream (30 percent fat), and heavy cream (36 percent fat). The half-and-half was far too lean, and the custard was watery and lightweight. The whipping cream custard was an improvement, but still a bit loose. Heavy cream makes a custard that is thick but not overbearing, luxurious but not death-defying. In short: everything we want.

USE YOLKS ONLY Firm custards, like crème caramel, are made with whole eggs, which help the custard to achieve a clean-cutting quality. Crème brûlée is richer and softer—with a puddinglike, spoon-clinging texture—in part because of the exclusive use of yolks. Using 4 cups of heavy cream, we played with the number of yolks here. The custard refuses to set with as few as six; eight is better, though still slurpy. With 12, however, the custard has a lovely lilting texture, a glossy, luminescent look, and the richest flavor.

PICK VANILLA BEANS We prefer the use of a vanilla bean, rather than vanilla extract, in this custard. The downside to starting with cold ingredients (as we do to prevent any curdling eggs) is that it becomes almost impossible to extract the flavor of a vanilla bean. We solve this problem with a hybrid technique: We scald half the cream, along with the sugar (to dissolve) and vanilla bean, and let it sit for 15 minutes to extract the flavor of the vanilla. Later, we add the cold cream to lower the temperature before mixing in the eggs. You end up with the tiny black flecks of vanilla bean seeds in the final dish, but don’t worry, it’s only added flavor. (It’s possible to use vanilla extract, but a bean is far better.)

COOL THE CREAM Even though we warm some of the cream to better extract the flavor of the vanilla, it’s important to lower the temperature before adding the eggs. Cold-started custard and scalded-cream custard display startling differences. As we’ve learned, eggs respond favorably to cooking at a slow, gentle pace. If heated quickly, they set only just shortly before they enter the overcooked zone, leaving a very narrow window between just right and overdone. If heated gently, however, they begin to thicken the custard at a lower temperature and continue to do so gradually. Therefore, cooling the cream before adding the eggs gives us more time to develop a perfectly textured crème brûlée before we enter the danger zone of overcooked eggs. Because the cream is not straight-from-the-fridge cold, the baking time is nicely reduced.

BATHE THE RAMEKINS We use a large baking dish for our water bath (or bain-marie, which prevents the custard from overcooking while the center saunters to the finish line), one that can hold all of the ramekins comfortably. (The ramekins must not touch and should be at least ½ inch away from the sides of the dish.) Line the bottom of the pan with a kitchen towel to protect the floors of the ramekins from the heat of the dish.

PICK THE BEST SUGAR For the crackly caramel crust, we prefer Demerara and turbinado sugars, which are both coarse light brown sugars. They are better than brown sugar, which is moist and lumpy, and granulated sugar, because it can be difficult to distribute evenly over the custards. Don’t use a broiler to caramelize; it’s an almost guaranteed fail with its uneven heat. A torch accomplishes the task efficiently. (And be sure to refrigerate the finished crèmes brûlées—the brûlée can warm up the custard, ruining an otherwise perfect dish.)

LOW OVEN HEATING AT WORK

CHEESECAKE AND CUSTARD PIE

Though we often use water baths to help our custards bake gently, sometimes just the oven is fine. For silky cakes and pies without rough edges and jiggly centers, we set our ovens low—very low. This helps the eggs to cook slowly and evenly. It also expands the window of opportunity before our desserts are cracked, rough, and woefully overcooked.

NEW YORK–STYLE CHEESECAKE

SERVES 12 TO 16

For the crust, chocolate wafers can be substituted for graham crackers; you will need about 14 wafers. The flavor and texture of the cheesecake are best if the cake is allowed to sit at room temperature for 30 minutes before serving. When cutting the cake, have a pitcher of hot tap water nearby; dipping the blade of the knife into the water and wiping it clean with a kitchen towel after each cut helps make neat slices. Serve with Fresh Strawberry Topping (recipe follows) if desired.

|

CRUST

|

|

8

|

whole graham crackers, broken into rough pieces

|

|

1

|

tablespoon sugar

|

|

5

|

tablespoons unsalted butter, melted

|

|

FILLING

|

|

2½

|

pounds cream cheese, cut into 1-inch chunks and softened

|

|

1½

|

cups (10½ ounces) sugar

|

|

1⁄8

|

teaspoon salt

|

|

1⁄3

|

cup sour cream

|

|

2

|

teaspoons lemon juice

|

|

2

|

teaspoons vanilla extract

|

|

6

|

large eggs plus 2 large yolks

|

|

1

|

tablespoon unsalted butter, melted

|

1. FOR THE CRUST: Adjust oven rack to lower-middle position and heat oven to 325 degrees. Process graham cracker pieces in food processor to fine crumbs, about 30 seconds. Combine graham cracker crumbs and sugar in medium bowl, add melted butter, and toss with fork until evenly moistened. Empty crumbs into 9-inch springform pan and, using bottom of ramekin or dry measuring cup, press crumbs firmly and evenly into pan bottom, keeping sides as clean as possible. Bake crust until fragrant and beginning to brown around edges, about 13 minutes. Let crust cool in pan on wire rack while making filling.

2. FOR THE FILLING: Increase oven temperature to 500 degrees. Using stand mixer fitted with paddle, beat cream cheese on medium-low speed until broken up and slightly softened, about 1 minute. Scrape down bowl. Add ¾ cup sugar and salt and beat on medium-low speed until combined, about 1 minute. Scrape down bowl, then beat in remaining ¾ cup sugar until combined, about 1 minute. Scrape down bowl, add sour cream, lemon juice, and vanilla, and beat on low speed until combined, about 1 minute. Scrape down bowl, add egg yolks, and beat on medium-low speed until thoroughly combined, about 1 minute. Scrape down bowl, add whole eggs, 2 at a time, beating until thoroughly combined, about 1 minute, and scraping bowl between additions.

3. Being careful not to disturb baked crust, brush inside of pan with melted butter and set pan on rimmed baking sheet to catch any spills in case pan leaks. Pour filling into cooled crust and bake for 10 minutes; without opening oven door, reduce temperature to 200 degrees and continue to bake until cheesecake registers about 150 degrees, about 1½ hours. Let cake cool on wire rack for 5 minutes, then run paring knife around cake to loosen from pan. Let cake continue to cool until barely warm, 2½ to 3 hours. Wrap tightly in plastic wrap and refrigerate until cold, at least 3 hours. (Cake can be refrigerated for up to 4 days.)

4. To unmold cheesecake, wrap hot kitchen towel around pan and let stand for 1 minute. Remove sides of pan. Slide thin metal spatula between crust and pan bottom to loosen, then slide cake onto serving platter. Let cheesecake sit at room temperature for about 30 minutes before serving. (Cheesecake can be made up to 3 days in advance; however, crust will begin to lose its crispness after only 1 day.)

FRESH STRAWBERRY TOPPING

MAKES ABOUT 6 CUPS

This accompaniment to cheesecake is best served the same day it is made.

|

2

|

pounds strawberries, hulled and sliced lengthwise ¼ to 1⁄8 inch thick (3 cups)

|

|

½

|

cup (3½ ounces) sugar

|

|

|

Pinch salt

|

|

1

|

cup strawberry jam

|

|

2

|

tablespoons lemon juice

|

1. Toss berries, sugar, and salt in medium bowl and let sit until berries have released juice and sugar has dissolved, about 30 minutes, tossing occasionally to combine.

2. Process jam in food processor until smooth, about 8 seconds, then transfer to small saucepan. Bring jam to simmer over medium-high heat and simmer, stirring frequently, until dark and no longer frothy, about 3 minutes. Stir in lemon juice, then pour warm liquid over strawberries and stir to combine. Let cool, then cover with plastic wrap and refrigerate until cold, at least 2 hours or up to 12 hours.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

A rejection of the Ben and Jerry school of everything-but-the-kitchen-sink concoctions, the ideal New York cheesecake is timeless in its adherence to simplicity. It is a tall, toasty-skinned, dense affair, a classic cheesecake with bronzed top and lush interior. After giving it a quick blast in a hot oven, we bake it low and slow for even cooking and a lovely graded texture.

MAKE A HOMEMADE CRUST Though some New York–style cheesecakes have pastry crusts, we find they become soggy beneath the filling. Our preference? Graham crackers. Store-bought graham cracker crumbs don’t taste nearly as good as crumbs you grind in the food processor from real graham crackers. We enrich ours with butter and sugar and press them into place in a springform pan with the bottom of a ramekin. Prebaking keeps this crust from becoming soggy.

USE ROOM-TEMPERATURE CHEESE A New York cheesecake should be one of great stature. When we made one with 2 pounds (four bars) of cream cheese, it was not tall enough. Therefore, we fill the springform pan to the very top with an added half-pound. It’s important that the cream cheese is at least moderately soft so that it can fully incorporate into the batter and you aren’t left with a piece of cake containing small nodules of unmixed cream cheese amid an otherwise smooth bite. Simply cutting the cheese into chunks and letting them stand while preparing the crust and assembling the other ingredients—30 to 45 minutes—makes mixing easier.

CHOOSE THE RIGHT DAIRY Cream cheese alone as the filling of a cheesecake makes for a pasty cake—much like a bar of cream cheese straight from its wrapper. Additional dairy loosens up the texture of the cream cheese, giving the cake a smoother, more luxurious texture. Although some recipes call for large amounts of sour cream, we use only 1⁄3 cup so that the cake has a nice tang but won’t end up tasting sour and acidic.

MIX WHOLE EGGS AND YOLKS In this cheesecake, eggs do a lot of work. They help to bind, making the cake cohesive and giving it structure. Whole eggs alone are often called for in softer, airier cheesecakes. But recipes for New York cheesecakes tend to include additional yolks, which add fat and emulsifiers, and less water than whole eggs, to help produce a velvety, lush texture. We use six eggs plus two yolks, a combination that produces a dense but not heavy, firm but not rigid, perfectly rich cake.

FLAVOR, PLEASE We keep the flavor of this cake simple. Lemon juice is a great addition, perking things up without adding a distinctively lemon flavor (no zest!). Just a bit of salt (cream cheese already contains sodium chloride) and a couple of teaspoons of vanilla extract round out the flavors well.

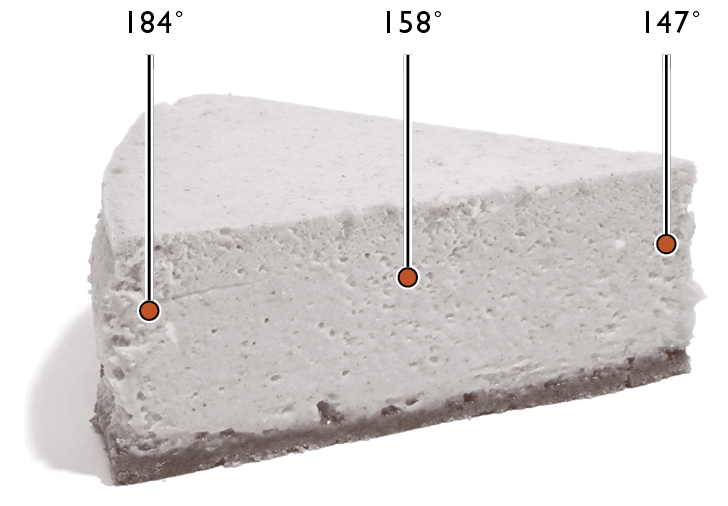

GO HIGH TO LOW There are many ways to bake a cheesecake—in a moderate oven, in a low oven, in a water bath, or in the New York fashion, in which the cake bakes at 500 degrees for about 10 minutes and then at 200 degrees for about an hour and a half. This super-simple, no-water-bath (no leaking pans, layers of foil prophylactics, or boiling water), dual-temperature baking method produces a lovely graded texture—soft and creamy at the center and firm and dry at the periphery. It also yields the attractive nut-brown surface that we’re after.

PREVENT CRACKS Some cooks use the crack to gauge when a cheesecake is done. But we say if there’s a crack it’s already overdone. The best way to prevent a cheesecake from cracking is to use an instant-read thermometer to test its doneness. Take the cake out of the oven when it reaches 150 degrees to avoid overbaking. Higher temperatures cause the cheesecake to rise so much that the delicate network of egg proteins tears apart as the center shrinks and falls during cool-down.

SEPARATE AND COOL During baking is not the only time a cheesecake can crack. There is a second opportunity outside the oven. A perfectly good-looking cake can crack as it sits on the cooling rack. The cake shrinks during cooling and will cling to the sides of the springform pan. If the cake clings tenaciously enough, the delicate egg structure splits at its weakest point, the center. To avoid this type of late cracking, cool the cheesecake for only a few minutes, then free it from the sides of the pan with a paring knife before allowing it to cool fully.

PUMPKIN PIE

SERVES 8

Use the Foolproof Baked Pie Shell. If candied yams are unavailable, regular canned yams can be substituted. When the pie is properly baked, the center 2 inches of the pie should look firm but jiggle slightly. The pie finishes cooking with residual heat; to ensure that the filling sets, let it cool at room temperature and not in the refrigerator. Do not cool this fully baked crust; the crust and filling must both be warm when the filling is added.

|

1

|

cup heavy cream

|

|

1

|

cup whole milk

|

|

3

|

large eggs plus 2 large yolks

|

|

1

|

teaspoon vanilla extract

|

|

1

|

(15-ounce) can unsweetened pumpkin puree

|

|

1

|

cup candied yams, drained

|

|

¾

|

cup (5¼ ounces) sugar

|

|

¼

|

cup maple syrup

|

|

2

|

teaspoons grated fresh ginger

|

|

1

|

teaspoon salt

|

|

½

|

teaspoon ground cinnamon

|

|

¼

|

teaspoon ground nutmeg

|

|

1

|

recipe Foolproof Baked Pie Shell, partially baked and still warm

|

1. Adjust oven rack to lowest position, place rimmed baking sheet on rack, and heat oven to 400 degrees. Whisk cream, milk, eggs and yolks, and vanilla together in bowl. Bring pumpkin, yams, sugar, maple syrup, ginger, salt, cinnamon, and nutmeg to simmer in large saucepan and cook, stirring constantly and mashing yams against sides of pot, until thick and shiny, 15 to 20 minutes.

2. Remove saucepan from heat and whisk in cream mixture until fully incorporated. Strain mixture through fine-mesh strainer into bowl, using back of ladle or spatula to press solids through strainer. Whisk mixture, then pour into warm prebaked pie crust.

3. Place pie on heated baking sheet and bake for 10 minutes. Reduce oven temperature to 300 degrees and continue to bake until edges of pie are set and center registers 175 degrees, 20 to 35 minutes longer. Let pie cool on wire rack to room temperature, about 4 hours. Serve.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Too many pumpkin pie recipes result in a grainy custard in a soggy crust. For our pumpkin pie recipe, we avoid this outcome by drying out the pumpkin puree (with yams added for complex flavor) on the stovetop before whisking in dairy and eggs. The hot filling lets the creamy custard firm up quickly in the oven, preventing it from both curdling and soaking into the crust.

PREBAKE PIE SHELL Prebaking the pie crust is an essential step here. If we skipped it, and instead poured the pie filling straight into the raw dough, we would end up with a soggy, sad crust when the pie finally exited the oven. This is because the filling is very wet, and the crust needs that extra alone time in the oven to crisp up before coming in contact with all the extra moisture. (For more on pie crust, see concept 44.)

PUT HOT FILLING IN WARM CRUST If you’re tempted to bake the pie crust way ahead of time, don’t. It’s imperative that the pie crust is warm when you add the hot filling. If it is not, the pie will become soggy. Using a hot filling in a warm crust allows the custard to firm up quickly in the oven, preventing it from soaking into the crust and turning it soggy. This is even true if you let the filling cool to room temperature. Keep that crust warm!

COOK THE PUMPKIN To maximize flavor, we concentrate the pumpkin’s liquid rather than remove it, and we’ve found it best to do this on the stove. This is an added bonus for the spices that we add to the filling as well. Cooking the fresh ginger and spices along with the pumpkin puree intensifies their taste—the direct heat blooms their flavors (see concept 33). In addition, cooking minimizes the mealy texture in this pie where pumpkin is the star.

SUPPLEMENT WITH YAMS When we used solely pumpkin puree, we craved more flavor complexity. Therefore, we experimented with roasted sweet potatoes, which added a surprisingly deep flavor without a wholly recognizable taste. In an effort to streamline this technique, we tried adding canned sweet potatoes—commonly labeled as yams—instead. They were a hit. The yams add a complex flavor that complements the pumpkin.

ADD EXTRA YOLKS Our goal with this pie was to eliminate the grainy texture that plagues most custard in favor of a creamy, sliceable, not-too-dense pie. We start with a balance of whole milk and cream, and firm up the mixture with eggs. We don’t simply add whole eggs, though—that just makes the pie too eggy. Because the whites are filled with much more water than the yolks, we exchange some whole eggs for the yolks alone. Don’t forget to pass the mixed filling through a fine-mesh strainer to remove any stringy bits. This will ensure the ultimate smooth texture.

TURN OVEN HIGH TO LOW Most pumpkin pie recipes call for a high oven temperature to expedite cooking time. But as we’ve learned, baking any custard at high heat has its dangers. Once the temperature of custard rises above 185 degrees it curdles, turning the filling coarse and grainy. This is why we cannot bake the pie at 425 degrees, as most recipes suggest. Lowering the temperature to 350 only provided us with a curdled and overcooked pie at the edges that was still underdone in the center. But baking at a low 300 degrees would mean leaving the pie in the oven for two hours. What to do? As with our New York–Style Cheesecake we combine the two techniques, blasting the pie for 10 minutes on high heat and then baking it at 300 degrees for the rest of the baking time. This lessens the cooking time exponentially and leaves us with a creamy pie fully and evenly cooked from edge to center.

TEMPERING AT WORK

CHEESECAKE AND ICE CREAM

Another technique we use to cook eggs gently and slowly for our stovetop custards is tempering. Tempering is the act of gradually increasing the temperature of a sensitive ingredient—in this case, eggs—to prevent it from curdling once added to a hot liquid. This is done by adding a small portion of the hot component (the base for lemon curd, for example) to the cooler ingredient (eggs) and stirring it in before adding the now-warmed ingredient to the rest of the hot component.

LEMON CHEESECAKE

SERVES 12 TO 16

When cutting the cake, have a pitcher of hot tap water nearby; dipping the blade of the knife into the water and wiping it clean with a kitchen towel after each cut helps make neat slices.

|

CRUST

|

|

5

|

ounces Nabisco Barnum’s Animals Crackers or Social Tea Biscuits

|

|

3

|

tablespoons sugar

|

|

4

|

tablespoons unsalted butter, melted

|

|

FILLING

|

|

1¼

|

cups (8¾ ounces) sugar

|

|

1

|

tablespoon grated lemon zest plus ¼ cup juice (2 lemons)

|

|

1½

|

pounds cream cheese, cut into 1-inch chunks and softened

|

|

4

|

large eggs, room temperature

|

|

2

|

teaspoons vanilla extract

|

|

¼

|

teaspoon salt

|

|

½

|

cup heavy cream

|

|

1

|

tablespoon unsalted butter, melted

|

|

LEMON CURD

|

|

1⁄3

|

cup lemon juice (2 lemons)

|

|

2

|

large eggs plus 1 large yolk

|

|

½

|

cup (3½ ounces) sugar

|

|

2

|

tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into ½-inch pieces and chilled

|

|

1

|

tablespoon heavy cream

|

|

¼

|

teaspoon vanilla extract

|

|

|

Pinch salt

|

1. FOR THE CRUST: Adjust oven rack to lower-middle position and heat oven to 325 degrees. Process cookies in food processor to fine crumbs, about 30 seconds (you should have about 1 cup). Add sugar and pulse 2 or 3 times to incorporate. Add melted butter in slow, steady stream while pulsing; pulse until mixture is evenly moistened and resembles wet sand, about 10 pulses. Empty crumbs into 9-inch springform pan and, using bottom of ramekin or dry measuring cup, press crumbs firmly and evenly into pan bottom, keeping sides as clean as possible. Bake crust until fragrant and golden brown, 15 to 18 minutes. Let cool on wire rack to room temperature, about 30 minutes. When cool, wrap outside of pan with two 18-inch square pieces of heavy-duty aluminum foil and set springform pan in roasting pan. Bring kettle of water to boil.

2. FOR THE FILLING: While crust is cooling, process ¼ cup sugar and lemon zest in food processor until sugar is yellow and zest is broken down, about 15 seconds, scraping down bowl as needed. Transfer lemon-sugar mixture to small bowl and stir in remaining 1 cup sugar.

3. Using stand mixer fitted with paddle, beat cream cheese on low speed until broken up and slightly softened, about 5 seconds. With mixer running, add lemon-sugar mixture in slow, steady stream; increase speed to medium and continue to beat until mixture is creamy and smooth, about 3 minutes, scraping down bowl as needed. Reduce speed to medium-low and beat in eggs, 2 at a time, until incorporated, about 30 seconds, scraping down bowl well after each addition. Add lemon juice, vanilla, and salt and mix until just incorporated, about 5 seconds. Add cream and mix until just incorporated, about 5 seconds longer. Give filling final stir by hand.

4. Being careful not to disturb baked crust, brush inside of pan with melted butter. Pour filling into prepared pan and smooth top with rubber spatula. Set roasting pan on oven rack and pour enough boiling water into roasting pan to come halfway up sides of pan. Bake cake until center jiggles slightly, sides just start to puff, surface is no longer shiny, and cake registers 150 degrees, 55 minutes to 1 hour. Turn off oven and prop open oven door with potholder or wooden spoon handle; allow cake to cool in water bath in oven for 1 hour. Transfer pan to wire rack. Remove foil, then run paring knife around cake and let cake cool completely on wire rack, about 2 hours.

5. FOR THE LEMON CURD: While cheesecake bakes, heat lemon juice in small saucepan over medium heat until hot but not boiling. Whisk eggs and yolk together in medium bowl, then gradually whisk in sugar. Whisking constantly, slowly pour hot lemon juice into eggs, then return mixture to saucepan and cook over medium heat, stirring constantly with wooden spoon, until mixture is thick enough to cling to spoon and registers 170 degrees, about 3 minutes. Immediately remove pan from heat and stir in cold butter until incorporated. Stir in cream, vanilla, and salt, then pour curd through fine-mesh strainer into small bowl. Place plastic wrap directly on surface of curd and refrigerate until needed.

6. When cheesecake is cool, scrape lemon curd onto cheesecake still in springform pan. Using offset spatula, spread curd evenly over top of cheesecake. Cover tightly with plastic and refrigerate for at least 4 hours or up to 1 day. To unmold cheesecake, wrap hot kitchen towel around pan and let stand for 1 minute. Remove sides of pan. Slide thin metal spatula between crust and pan bottom to loosen, then slide cake onto serving platter and serve. (Cake can be made up to 3 days in advance; however, the crust will begin to lose its crispness after only 1 day.)

GOAT CHEESE AND LEMON CHEESECAKE WITH HAZELNUT CRUST

The goat cheese gives this cheesecake a distinctive tang and a slightly savory edge. Use a mild-flavored goat cheese.

For crust, process generous 1⁄3 cup hazelnuts, toasted, skinned, and cooled, in food processor with sugar until finely ground and mixture resembles coarse cornmeal, about 30 seconds. Add cookies and process until mixture is finely and evenly ground, about 30 seconds. Reduce melted butter to 3 tablespoons. For filling, reduce cream cheese to 1 pound and beat 8 ounces room-temperature goat cheese with cream cheese in step 3. Omit salt.

TRIPLE-CITRUS CHEESECAKE

For filling, reduce lemon zest to 1 teaspoon and lemon juice to 1 tablespoon. Process 1 teaspoon grated lime zest and 1 teaspoon grated orange zest with lemon zest in step 2. Add 1 tablespoon lime juice and 2 tablespoons orange juice to mixer with lemon juice in step 3. For curd, reduce lemon juice to 2 tablespoons and heat 2 tablespoons lime juice, 4 teaspoons orange juice, and 2 teaspoons grated orange zest with lemon juice in step 5. Omit vanilla.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

We love cheesecake it in its unadulterated form, but sometimes the fresh flavor of citrus can take it to a refreshing new level. We aimed to develop a creamy cheesecake with a bracing but not overpowering lemon flavor. The use of animal rather than graham crackers, lemon zest, heavy cream, lemon curd, and—of course—a water bath helps us to achieve the ultimate lemon cheesecake. In addition: This cheesecake has a crowning layer of lemon curd, which in turn demonstrates the power of tempering at work.

USE ANIMAL CRACKERS Most cheesecakes have sweet and spicy graham cracker crusts that remain crunchy under the weight of the cheesy filling. But here the strong molasses taste of the graham crackers overwhelms the lemon flavor. We experimented with several kinds of more neutral-flavored crumb crusts and found that we liked the one made with animal crackers the best.

PROCESS ZEST FOR FLAVOR Zest offers a nice balance of lemon flavor, but it comes with a hitch: The fibrous texture of the zest can mar the creamy smoothness of the filling. To solve this, we process the zest and ¼ cup of sugar together before adding them to the cream cheese. This produces a wonderfully potent lemon flavor by breaking down the zest and releasing its oils. Don’t process all the sugar, though; that would wreak havoc with its crystalline structure (necessary for aerating the cream cheese) as well as meld it with the oils from the lemon zest, creating a strangely dense cake.

BAKE IN A BATH Like our Spiced Pumpkin Cheesecake, this cheesecake is baked in a water bath in a 325-degree oven. But here we turn the oven off and leave the cake in the oven for an additional hour with the door ajar. This technique of cooking at a very slow crawl so as not to overcook the eggs gives us a foolproof creamy consistency in our cheesecake from edge to center. We cook our cheesecake until it reaches 150 degrees in the center; this accounts for the fact that the edges, which generally cook faster, have already reached 170 degrees.

CHILL THE CAKE If the cheesecake is not thoroughly chilled, it will not hold its shape when sliced. After four hours in the refrigerator (and preferably longer), the cheesecake has set up. The fat in cream cheese has a relatively low softening temperature, and the high proportion of cream cheese to eggs makes it difficult for the egg proteins alone to provide enough structure when the cheesecake is warm. The solution is to ensure the cream cheese is cold enough to be firm. Likewise, the curd will firm up only when the cheesecake is thoroughly chilled. Only then can the cake be sliced neatly.

USE ACID To make a creamy curd with a silken texture, acid is key. Here, we get it from the lemon juice. The acid changes the electrical charge of the egg proteins, causing them to denature and eventually form a gel (see “How Does Acid Affect the Texture of Eggs?").

TIME TO TEMPER Like other stovetop custards, lemon curd combines eggs with hot liquid. To heat the eggs gently, we temper them, or slowly whisk in the hot liquid before putting the eggs on the stove. On the stove, we stir the mixture constantly (this motion reduces the amount that the egg proteins will bond so that our end product is a sauce rather than a solid mass) until it reaches 170 degrees. Be careful not to overcook the curd. While we want to get the maximum thickening power from the heat, we don’t want so much that the eggs will curdle.

COLD BUTTER COOLS DOWN CURD Once the curd reaches 170 degrees, immediately remove the pan from the heat and stir in cold cubed butter, which cools the curd and prevent curdling and overcooking. The butter also helps to create a smoother emulsion. (For more on emulsions, see concept 36.)

VANILLA ICE CREAM

MAKES ABOUT 1 QUART

Two teaspoons of vanilla extract can be substituted for the vanilla bean; stir the extract into the cold custard in step 3. An instant-read thermometer is critical for the best results. Using a prechilled metal baking pan and working quickly in step 4 will help prevent melting and refreezing of the ice cream and will speed the hardening process. If using a canister-style ice cream machine, be sure to freeze the empty canister for at least 24 hours and preferably 48 hours before churning. For self-refrigerating ice cream machines, prechill the canister by running the machine for five to 10 minutes before pouring in the custard.

|

1

|

vanilla bean

|

|

1¾

|

cups heavy cream

|

|

1¼

|

cups whole milk

|

|

½

|

cup plus 2 tablespoons sugar

|

|

1⁄3

|

cup light corn syrup

|

|

¼

|

teaspoon salt

|

|

6

|

large egg yolks

|

1. Place 8- or 9-inch square metal baking pan in freezer. Cut vanilla bean in half lengthwise. Using tip of paring knife, scrape out vanilla seeds. Combine vanilla bean, seeds, cream, milk, ¼ cup plus 2 tablespoons sugar, corn syrup, and salt in medium saucepan. Heat over medium-high heat, stirring occasionally, until mixture is steaming steadily and registers 175 degrees, 5 to 10 minutes. Remove saucepan from heat.

2. While cream mixture heats, whisk yolks and remaining ¼ cup sugar together in bowl until smooth, about 30 seconds. Slowly whisk 1 cup heated cream mixture into egg yolk mixture. Return mixture to saucepan and cook over medium-low heat, stirring constantly, until mixture thickens and registers 180 degrees, 7 to 14 minutes. Immediately pour custard into large bowl and let cool until no longer steaming, 10 to 20 minutes. Transfer 1 cup custard to small bowl. Cover both bowls with plastic wrap. Place large bowl in refrigerator and small bowl in freezer and cool completely, at least 4 hours or up to 24 hours. (Small bowl of custard will freeze solid.)

3. Remove custards from refrigerator and freezer. Scrape frozen custard from small bowl into large bowl of custard. Stir occasionally until frozen custard has fully dissolved. Strain custard through fine-mesh strainer and transfer to ice cream machine. Churn until mixture resembles thick soft-serve ice cream and registers about 21 degrees, 15 to 25 minutes. Transfer ice cream to frozen baking pan and press plastic wrap onto surface. Return to freezer until firm around edges, about 1 hour.

4. Transfer ice cream to airtight container, pressing firmly to remove any air pockets, and freeze until firm, at least 2 hours. Serve. (Ice cream can be stored for up to 5 days.)

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

While you might not think of heat and eggs when making ice cream, eggs give homemade ice cream its silky texture. But heat the eggs and cream incorrectly and you get ice cream with odd lumps and awful eggy flavor. The quicker it freezes, the smoother the ice cream, so we speed up the freezing time of our homemade Vanilla Ice Cream recipe by starting with a colder base. Supplementing the sugar with corn syrup gives us ice cream that freezes faster, remains hard at home-freezer temperatures, and is free of large ice crystals.

TEMPER THE EGGS Because we are making this custard on the stovetop, as we do for Lemon Curd, the techniques of a water bath or a low-temperature oven are not available to help us cook the eggs gently. Instead, we temper them by adding 1 cup of the hot cream mixture to the yolks, slowly whisking away. This not only warms the eggs up gently, it also dilutes the proteins so they are less likely to bond so tightly that they curdle when cooking on the stovetop.

COOK TO 180 DEGREES Though on their own, egg yolks begin to solidify around 150 degrees, the other ingredients that we add to this custard change the temperature of coagulation. For example, milk dilutes the proteins as well as introduces some fat, both of which raise the temperature at which eggs coagulate because in their presence the proteins don’t bump into each other as readily. Sugar slows down protein unfolding as well. So together, the extra ingredients in our custard base raise the coagulation temperature of egg yolks to around 180 degrees. This is why it’s so important to cook the custard until it reaches that point. Below that temperature, the egg proteins will not have uncoiled enough to form sufficient bonds to create the solid gel structure we need. (Make sure to strain the custard before freezing to remove any little bits that may have curdled along the way.)

SUPER-CHILL THE CUSTARD Smooth ice cream isn’t technically less icy than “icy” ice cream. Instead, its ice crystals are so small that our tongues can’t detect them. One way to encourage the creation of small ice crystals is to freeze the ice cream base as quickly as possible. Fast freezing, along with agitation, causes the formation of thousands of tiny seed crystals, which in turn promote the formation of more tiny crystals. Speed is such an important factor in ice cream making that commercial producers as well as restaurant kitchens spend tens of thousands of dollars on super-efficient “continuous batch” churners. The best of these can turn a 40-degree custard base (the coldest temperature it can typically achieve in a refrigerated environment) into soft-serve ice cream in 24 seconds. Our canister-style machine, on the other hand, takes roughly 35 minutes. No wonder our ice creams had always been so icy!

To combat this, we start with a colder base. After letting the hot custard cool for a few minutes, we pop 1 cup of it into the freezer and let the rest of the custard chill in the fridge overnight. The next day we mix the two together and churn the blend (now a cool 30 degrees) in our machine for a much smoother result.

COMBAT ICINESS WITH CORN SYRUP One key to our ice cream’s smoothness was to replace some of the sugar with corn syrup. (This was after trying other ice-crystal-reducing ingredients—condensed and evaporated milk, cornstarch, gelatin, pectin, and nonfat dry milk—to no avail.) This sweetener has a twofold effect: First, it is made up of glucose molecules and large tangled chains of starch that interrupt the flow of water molecules in a custard base. Since the water molecules can’t move freely, they are less likely to combine and form large crystals as the ice cream freezes. Second, corn syrup creates a higher freezing point in ice cream than granulated sugar does. Since the water in ice cream made with corn syrup freezes at a higher temperature it is less likely to thaw and refreeze. This makes the ice cream less susceptible to the temperature shifts inevitable in a home freezer. These shifts cause constant thawing and refreezing, which creates large crystals even in the smoothest ice cream. Our ice cream stays smooth for nearly a week—far longer than most homemade ice creams do.

HARDEN FAST But we don’t stop there. For creamier results, we also needed to figure out a way to get our already-churned ice cream to freeze faster than it had in the past. With no way to make our freezer colder, we took a different route. Instead of scraping our churned ice cream into a tall container before placing it in the freezer, we spread it into a thin layer in a chilled square metal baking pan (metal conducts heat faster than glass or plastic). In an hour’s time, the ice cream firms up significantly and can easily be scooped and transferred to an airtight container.