CONCEPT 48

Sugar Changes Texture (and Sweetness)

Even novice cooks understand that if they add more sugar to a dessert it will become sweeter. But what many fail to realize is that sugar can have a huge effect on texture, too, changing the structure of foods ranging from cookies to frozen desserts.

HOW THE SCIENCE WORKS

Sweeteners come in many forms, most of them familiar to the home cook. There is crystalline white table sugar, deep bronze brown sugar, thick, oozy molasses, and the lighter, golden honey. What is less familiar is how sweeteners really work.

Let’s begin with structure. Sugar can be a single molecule made up of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen—like glucose and fructose. Other sugars, like sucrose, are made of two or more molecules (in this case, one glucose and one fructose) tied together with chemical bonds. Table sugar, for example, consists of virtually pure sucrose. (For more information on sugars, see “Sweeteners 101.”)

Sucrose is abundant in many plants, especially fruits. But unlike in fruits, some plants, like potatoes, convert the sucrose they form by photosynthesis into starch. This process is reversible, which explains why some vegetables can become sweeter when stored in the refrigerator. Table sugar is produced from either sugar cane or sugar beets. It is highly water soluble and when dissolved, the sucrose molecules organized within each crystal disperse into the water. Sugar doesn’t melt, not in the traditional sense like an ice cube, but instead decomposes when it is brought to temperatures between 320 and 367 degrees.

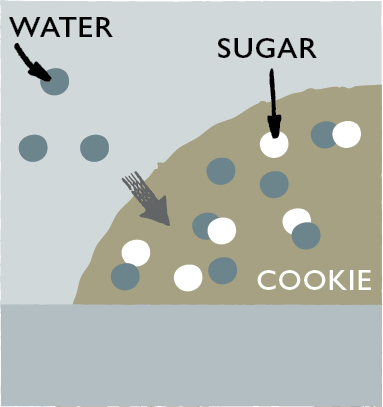

So how does sugar affect texture in cookies, and even frozen desserts? It has everything to do with moisture. Sucrose is hygroscopic, which means it has an affinity for water molecules.

What happens is this: Because of the nature of the hydrogen and oxygen atoms in both water and sugar, they are electrostatically attracted to each other. When water and sugar are combined, they link together and form hydrogen bonds. It takes a fair amount of heat energy to break these bonds and, as a result, table sugar will hold on to moisture in food. Because of this tendency, sugar can slow the evaporation of moisture from cookies and cakes as they bake, which makes a tremendous difference when it comes to producing moist, tender baked goods.

In addition, when sucrose is heated along with some acid, it breaks back down into two simple sugars, glucose and fructose. When this happens, the result is called an invert sugar. Because fructose does not easily crystallize in the presence of glucose, invert sugars are always viscous liquids. A benefit of invert sugar comes into play when making, for example, chewy cookies (see Test Kitchen Experiment, opposite). Invert sugar is especially hygroscopic, pulling water from wherever it can be found, the best source being the air. Because brown sugar has more invert sugar than granulated sugar, it is our sugar of choice when baking chewy cookies—especially because invert sugar keeps on drawing in moisture even after cookies have been baked, thus helping them to stay chewy as they cool.

Finally, sugar likewise affects the texture of frozen desserts. How? When making frozen desserts, sugar is usually heated with a liquid (cream, water, fruit juice) so that it dissolves. When dissolved, sugar lowers the freezing point of water. This means that a sugar-water mixture freezes at a lower temperature than water alone. And because this mixture freezes at a lower temperature, it is able to become far colder than 32 degrees before beginning to form ice crystals while being made into ice cream. This means that when the ice crystals do form they form very rapidly—and stay very small. And tiny ice crystals translate into ice creams, sherbets, and sorbets that we perceive as smooth and creamy, not icy or grainy.

TEST KITCHEN EXPERIMENT

To show the powerful effect that sugar can have on the texture of a baked good, we ran the following experiment: We made two batches of our Chocolate-Chunk Oatmeal Cookies, one with brown sugar and the other with granulated white sugar. To isolate this variable, we kept the rest of the ingredients and the baking procedure identical. We repeated the experiment three times.

THE RESULTS

After the cookies had cooled to room temperature, we tasted them for chewiness and then attempted to bend a sample of each batch around a large wooden rolling pin (no easy task for firm, crunchy cookies). The results were clear as day: The brown sugar cookies had serious chew and the flexibility to conform to the curvature of the rolling pin. On the other hand, the cookies made with white sugar were crunchy rather than chewy and quickly snapped when bent.

THE TAKEAWAY

So you want to make some chewy cookies? Using brown sugar is a good start. Our findings confirm the science that sweeteners (like brown sugar) that contain invert sugar help to retard the crystallization of sucrose, therefore holding on to more moisture than white sugar and better maintaining a chewy texture as the cookie cools.

But there are a few other important steps to take for chewy cookies. First, don’t be afraid of butter. Many of the cookie recipes that follow rely on melted butter. (Remember that butter is roughly 16 to 18 percent water, and by melting the butter you are encouraging the formation of gluten when the flour is added to the batter.) Second, use a generous amount of dough for each cookie. It’s very hard to keep small cookies chewy. Use at least 2 tablespoons of dough (and even more in some cases) for each cookie. Third, don’t overbake. Even with brown sugar and melted butter in the mix, if you overbake any of these cookies they will lose their chewy texture. Fourth, be sure to take the cookies out of the oven when they are set around the edges but look a bit underdone in the center. They will continue to firm up as they cool on the baking sheet. Finally, chewy cookies will become less chewy over time. Storing them in an airtight container helps.

INVERT SUGARS AT WORK

CHEWY COOKIES

The cookie recipes that follow rely on brown sugar, careful baking, and melted butter (in two cases) to create and maintain a good chewy texture. Brown sugar contains invert sugars, which retard the crystallization of sucrose and therefore help the cookies retain moisture as they both bake and cool. Remember to use a generous scoop of dough for each cookie and not to overbake.

BROWN SUGAR COOKIES

MAKES ABOUT 24 COOKIES

Avoid using a nonstick skillet to brown the butter; the dark color of the nonstick coating makes it difficult to gauge when the butter is sufficiently browned. Use fresh, moist brown sugar, as hardened brown sugar will make the cookies too dry. Achieving the proper texture—crisp at the edges and chewy in the middle—is critical to this recipe. Because the cookies are so dark, it’s hard to judge doneness by color. Instead, gently press halfway between the edge and center of the cookie. When it’s done, it will form an indentation with slight resistance. Check early and err on the side of underdone.

|

14

|

tablespoons unsalted butter

|

|

2

|

cups packed (14 ounces) dark brown sugar

|

|

¼

|

cup (1¾ ounces) granulated sugar

|

|

2

|

cups plus 2 tablespoons (102⁄3 ounces) all-purpose flour

|

|

½

|

teaspoon baking soda

|

|

¼

|

teaspoon baking powder

|

|

½

|

teaspoon salt

|

|

1

|

large egg plus 1 large yolk

|

|

1

|

tablespoon vanilla extract

|

1. Melt 10 tablespoons butter in 10-inch skillet over medium-high heat. Cook, swirling pan constantly, until butter is dark golden brown and has nutty aroma, 1 to 3 minutes. Transfer browned butter to large heatproof bowl. Add remaining 4 tablespoons butter and stir until completely melted; set aside for 15 minutes.

2. Meanwhile, adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 350 degrees. Line 2 baking sheets with parchment paper. In shallow baking dish, mix ¼ cup brown sugar and granulated sugar until well combined; set aside. Whisk flour, baking soda, and baking powder together in medium bowl; set aside.

3. Add remaining 1¾ cups brown sugar and salt to bowl with cooled butter; mix until no sugar lumps remain, about 30 seconds. Scrape down bowl; add egg, yolk, and vanilla and mix until fully incorporated, about 30 seconds. Scrape down bowl. Add flour mixture and mix until just combined, about 1 minute. Give dough final stir to ensure that no flour pockets remain.

4. Working with 2 tablespoons of dough at a time, roll into balls. Roll half of dough balls into sugar mixture to coat. Place dough balls 2 inches apart on prepared baking sheet; repeat with remaining dough balls.

5. Bake 1 sheet at a time until cookies are browned and still puffy and edges have begun to set but centers are still soft (cookies will look raw between cracks and seem underdone), 12 to 14 minutes, rotating baking sheet halfway through baking. Let cookies cool on baking sheet for 5 minutes; transfer to wire rack and let cool to room temperature.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Simple sugar cookies, while classic, can seem too simple—even dull—at times. We wanted to turn up the volume on the sugar cookie by switching out the granulated sugar in favor of brown sugar. We had a clear vision of this cookie. It would be oversized, with a crackling crisp exterior and a chewy interior. And its flavor would scream “brown sugar.” We wanted butter for optimal flavor, but the traditional creaming method (see concept 46) gave us cakey and tender cookies while cutting the butter into the flour produced crumbly cookies. The solution? Melting the butter.

BROWN THE BUTTER Melting the butter is a good start if you want a chewy cookie, but if you brown that butter you develop a range of butterscotch and toffee flavors, too. Adding a full tablespoon of vanilla helps boost the nutty flavors in our cookies without using more brown sugar (which would make them overly sweet). Make sure to use the full ½ teaspoon of salt—you need it to balance the sweetness of these cookies.

LOSE A WHITE Egg whites tend to make cookies cakey—they cause the cookies to puff and dry out. We use a whole egg plus a yolk for richness, leaving out the second white.

USE TWO LEAVENERS The choice of leavener is probably the most confusing part of any cookie recipe (see concept 42). Sugar cookies typically contain baking powder—a mixture of baking soda and a weak acid (calcium acid phosphate) that is activated by moisture and heat. The soda and acid create gas bubbles, which expand cookies and other baked goods. However, many baked goods with brown sugar call for baking soda instead. This is because while granulated sugar is neutral, dark brown sugar can be slightly acidic. But when we used baking soda by itself, the cookies had an open, coarse crumb and craggy top. Tasters loved the craggy top, not the coarse crumb. When we used baking powder by itself, the cookies had a finer, tighter crumb but the craggy top disappeared. After a dozen rounds of testing, we settled on using a combination of both leaveners to moderate the coarseness of the crumb without compromising the craggy tops.

ROLL IN BROWN SUGAR Dark brown sugar is the obvious choice for the dough itself—more butterscotch, brown sugar flavor, and more chewiness because it has more moisture and a little more invert sugar than light brown sugar. Rolling balls of dough in more brown sugar boosts their flavor further. Adding some granulated sugar keeps the brown sugar from clumping.

BAKE ONE SHEET AT A TIME We had hoped to be able to bake two sheets of cookies at a time, but even with rotating and changing tray positions at different times during baking, we could not get two-tray baking to work. Some of the cookies had the right texture, but others were inexplicably dry. Baking one tray at a time allows for even heat distribution and ensures that every cookie has the same texture. It’s important not to overbake these cookies. To check cookies for doneness, gently press halfway between the edge and center of the cookie. When the cookie is done, your finger will form an indentation with slight resistance.

CHOCOLATE-CHUNK OATMEAL COOKIES WITH PECANS AND DRIED CHERRIES

MAKES ABOUT 16 LARGE COOKIES

We like these cookies made with pecans and dried sour cherries, but walnuts or skinned hazelnuts can be substituted for the pecans and dried cranberries for the cherries. Quick oats used in place of the old-fashioned oats will yield a cookie with slightly less chewiness.

|

1¼

|

cups (6¼ ounces) all-purpose flour

|

|

¾

|

teaspoon baking powder

|

|

½

|

teaspoon baking soda

|

|

½

|

teaspoon salt

|

|

1¼

|

cups (3¾ ounces) old-fashioned rolled oats

|

|

1

|

cup pecans, toasted and chopped

|

|

1

|

cup (4 ounces) dried sour cherries, chopped coarse

|

|

4

|

ounces bittersweet chocolate, chopped into chunks about size of chocolate chips

|

|

12

|

tablespoons unsalted butter, softened (68 degrees)

|

|

1½

|

cups packed (10½ ounces) dark brown sugar

|

|

1

|

large egg

|

|

1

|

teaspoon vanilla extract

|

1. Adjust oven racks to upper-middle and lower-middle positions and heat oven to 350 degrees. Line 2 baking sheets with parchment paper.

2. Whisk flour, baking powder, baking soda, and salt together in medium bowl. In second medium bowl, stir oats, pecans, cherries, and chocolate together.

3. Using stand mixer fitted with paddle, beat butter and sugar at medium speed until no sugar lumps remain, about 1 minute, scraping down bowl as needed. Add egg and vanilla and beat on medium-low until fully incorporated, about 30 seconds, scraping down bowl as needed. Reduce speed to low, add flour mixture, and mix until just combined, about 30 seconds. Gradually add oat mixture; mix until just incorporated. Give dough final stir to ensure that no flour pockets remain and ingredients are evenly distributed.

4. Working with ¼ cup of dough at a time, roll into balls and place 2½ inches apart on prepared baking sheets. Press dough to 1-inch thickness using bottom of greased measuring cup. Bake until cookies are medium brown and edges have begun to set but centers are still soft (cookies will seem underdone and will appear raw, wet, and shiny in cracks), 20 to 22 minutes, switching and rotating baking sheets halfway through baking.

5. Let cookies cool on baking sheets for 5 minutes; transfer cookies to wire rack and let cool to room temperature.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

It’s easy to get carried away and overload cookie dough with a crazy jumble of ingredients, resulting in a poorly textured cookie monster. Our ultimate oatmeal cookie would have just the right amount of added ingredients and an ideal texture—crisp around the edges and chewy in the middle. To get the results we wanted, we used brown sugar for moisture and a combination of leaveners. Also, keep a careful eye on the timing to make sure the cookies don’t overbake.

MAKING LOADED OATMEAL COOKIES Sure, we like plain oatmeal cookies but here we wanted something special, loaded with flavorful ingredients. Many recipes add too many goodies to the batter. We found that a careful balance of bittersweet chocolate chunks (semisweet is too sweet), pecans (toasting is essential to bring out their flavor), and dried sour cherries (you need something tart) is the way to make a truly great oatmeal cookie. No spices. No coconut. No raisins or dried tropical fruits.

START WITH THE RIGHT OATS When baking we find that old-fashioned oats are far superior to the other choices. Steel-cut oats are great for breakfast but make dry, pebbly cookies. Instant oats will create dense, mealy cookies lacking in good oat flavor. Quick oats are OK, but they taste somewhat bland, and the cookies won’t be quite as chewy.

USE ALL BROWN SUGAR We use brown sugar to help add moisture (it is more moist than white sugar). After testing a half-dozen combinations, we found that using all dark brown sugar is best. All light brown sugar is the second best option. In addition to being more moist, the cookies made with brown sugar are chewier than cookies made with granulated, and the brown sugar also gives the cookies a rich, dark color and deep caramel flavor.

PICK TWO LEAVENERS We began making these cookies with baking soda, which made the cookies crisp from the inside out—a problem, since we want a chewy interior and a crisp exterior. When we switched to baking powder, the cookies puffed in the oven and then collapsed, losing their shape and yielding not a hint of crispy exterior. Because we want a combination of crisp edges and chewy centers, we use a combination of baking powder and soda. This pairing produces cookie that are light and crisp on the outside but chewy, dense, and soft in the center. (For more on leaveners, see concept 42.)

ULTIMATE CHOCOLATE CHIP COOKIES

MAKES ABOUT 16 LARGE COOKIES

Avoid using a nonstick skillet to brown the butter; the dark color of the nonstick coating makes it difficult to gauge when the butter is sufficiently browned. Use fresh, moist brown sugar, as hardened brown sugar will make the cookies too dry.

|

1¾

|

cups (8¾ ounces) all-purpose flour

|

|

½

|

teaspoon baking soda

|

|

14

|

tablespoons unsalted butter

|

|

¾

|

cup packed (5¼ ounces) dark brown sugar

|

|

½

|

cup (3½ ounces) granulated sugar

|

|

1

|

teaspoon salt

|

|

2

|

teaspoons vanilla extract

|

|

1

|

large egg plus 1 large yolk

|

|

1¼

|

cups (7½ ounces) semisweet chocolate chips or chunks

|

|

¾

|

cup pecans or walnuts, toasted and chopped (optional)

|

1. Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 375 degrees. Line 2 baking sheets with parchment paper. Whisk flour and baking soda together in medium bowl; set aside.

2. Melt 10 tablespoons butter in 10-inch skillet over medium-high heat. Continue cooking, swirling pan constantly, until butter is dark golden brown and has nutty aroma, 1 to 3 minutes. Transfer browned butter to large heatproof bowl. Add remaining 4 tablespoons butter and stir until completely melted.

3. Add brown sugar, granulated sugar, salt, and vanilla to melted butter; whisk until fully incorporated. Add egg and yolk; whisk until mixture is smooth with no sugar lumps remaining, about 30 seconds. Let mixture stand for 3 minutes, then whisk for 30 seconds. Repeat process of resting and whisking 2 more times until mixture is thick, smooth, and shiny. Using rubber spatula, stir in flour mixture until just combined, about 1 minute. Stir in chocolate chips and nuts, if using. Give dough final stir to ensure that no flour pockets remain and ingredients are evenly distributed.

4. Working with 3 tablespoons of dough at a time, roll into balls and place 2 inches apart on prepared baking sheets.

5. Bake 1 sheet at a time until cookies are golden brown and still puffy and edges have begun to set but centers are still soft, 10 to 14 minutes, rotating baking sheet halfway through baking. Transfer baking sheet to wire rack; let cookies cool to room temperature.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Since Nestlé first began printing the recipe for Toll House cookies on the back of chocolate chip bags in 1939, generations of bakers have packed chocolate chip cookies into lunches and taken them to potlucks. But after a few samples, we wondered if this was really the best that a chocolate chip cookie could be. We wanted to refine this recipe to create a moist and chewy chocolate chip cookie with crisp edges and deep notes of toffee and butterscotch to balance its sweetness—in short, a more sophisticated cookie than the standard bake-sale offering. Melting a generous amount of butter before combining it with other ingredients gives us the chewy texture we wanted. We also use a bit more brown sugar than white sugar to enhance chewiness. The resulting cookies are crisp and chewy and gooey with chocolate and boast a complex medley of sweet, buttery, caramel, and toffee flavors.

CHANGE SUGAR Traditionally, Toll House cookies have a 1:1 ratio of brown sugar to white sugar. White sugar granules lend crispness, while brown sugar, which is more hygroscopic (meaning it attracts and retains water, mainly from the air) than white sugar, enhances chewiness. All that moisture sounds like a good thing—but it’s too good, in fact. Cookies made with all brown sugar are beyond chewy here. They are so moist they’re nearly floppy. We got the best results when we changed the ratio of brown sugar to white sugar to 3:2. This recipe works with light brown sugar, but the cookies will be less full-flavored.

BROWN THE BUTTER, LOSE ONE WHITE As with our Brown Sugar Cookies, we brown the butter here for flavor. (Melting the butter increases chewiness as well.) Losing an egg white (which makes cookies more cakey) also improves chewiness.

WHISK AND WAIT After stirring together the butter, sugar, and eggs … wait. After 10 minutes, the sugar will have dissolved and the mixture will turn thick and shiny, like frosting. The finished cookies will emerge from the oven with a slight glossy sheen and an alluring surface of cracks and crags, with a deep, toffeelike flavor. This is because by allowing the sugar to rest in the liquids, more of it dissolves in the small amount of moisture before baking. The dissolved sugar caramelizes more easily and helps to create a cookie with crisp edges and a chewy center (see “For Perfect Cookies, Look to Sugar”).

BAKE IN A MODERATE OVEN With caramelization in mind, we bake our cookies in a 375-degree oven—the same as for Toll House cookies. Baking two trays a time may be convenient, but it leads to uneven cooking. The cookies on the top tray are often browner around the edges than those on the bottom, even when rotated halfway through baking. These cookies will finish crisp and chewy, gooey with chocolate, with a complex medley of sweet, buttery, caramel, and toffee flavors. In other words? Perfect.

SUGAR SYRUPS AT WORK

CREAMY FROZEN DESSERTS

When sugar is used in cookies, it is a liquid (dissolved) ingredient in a mixture that is mostly dry ingredients. Sugar behaves differently when heated in a purely liquid medium, as is the case when making frozen desserts. While sugar plays an important role in ice cream (see Vanilla Ice Cream), its effect on texture is less clear-cut in a recipe with so much fat. However, in sherbets and ices, which contain little or no fat, sugar is the key ingredient that determines the size of the frozen crystals and the overall texture of the dessert.

FRESH ORANGE SHERBET

MAKES ABOUT 1 QUART

If using a canister-style ice-cream machine, be sure to freeze the empty canister at least 24 hours and preferably 48 hours before churning. For self-refrigerating ice cream machines, prechill the canister by running the machine for five to 10 minutes before pouring in the sherbet. For the freshest, purest orange flavor, use freshly squeezed unpasteurized orange juice (either store-bought or juiced at home). Pasteurized fresh-squeezed juice makes an acceptable though noticeably less fresh-tasting sherbet. Do not use juice made from concentrate, which has a cooked and less bright flavor.

|

1

|

cup (7 ounces) sugar

|

|

1

|

tablespoon grated orange zest plus 2 cups juice (4 oranges)

|

|

1⁄8

|

teaspoon salt

|

|

3

|

tablespoons lemon juice

|

|

2

|

teaspoons triple sec or vodka

|

|

2⁄3

|

cup heavy cream

|

1. Pulse sugar, orange zest, and salt in food processor until damp, 10 to 15 pulses. With processor running, add orange juice and lemon juice in slow, steady stream; continue to process until sugar is fully dissolved, about 1 minute. Strain mixture through fine-mesh strainer into medium bowl; stir in triple sec, then cover and place in freezer until chilled and mixture registers about 40 degrees, 30 minutes to 1 hour. Do not let mixture freeze.

2. When mixture is chilled, using whisk, whip cream in medium bowl until soft peaks form. Whisking constantly, add juice mixture in steady stream, pouring against edge of bowl. Transfer to ice cream machine and churn until mixture resembles thick soft-serve ice cream, 25 to 30 minutes.

3. Transfer sherbet to airtight container, press firmly to remove any air pockets, and freeze until firm, at least 3 hours. (Sherbet can be frozen for up to 1 week.)

FRESH LIME SHERBET

Substitute lime zest for orange zest, increase sugar to 1 cup plus 2 tablespoons, and omit lemon juice. Substitute 2⁄3 cup lime juice (6 limes) combined with 1½ cups water for orange juice.

FRESH LEMON SHERBET

Omit orange juice. Substitute lemon zest for orange zest, increase sugar to 1 cup plus 2 tablespoons, and increase lemon juice to 2⁄3 cup (4 lemons). Combine lemon juice with 1½ cups water before adding to food processor.

FRESH RASPBERRY SHERBET

In-season fresh raspberries have the best flavor, but when they are not in season, frozen raspberries are a better option. Substitute a 12-ounce bag of frozen raspberries for fresh.

Omit orange zest and juice. Cook 15 ounces (3 cups) raspberries with sugar, salt, and ¾ cup water in medium saucepan over medium heat, stirring occasionally, until mixture just begins to simmer, about 7 minutes. Strain through fine-mesh strainer into medium bowl, pressing on solids to extract as much liquid as possible. Add lemon juice and triple sec; cover and place in freezer until chilled and mixture registers about 40 degrees, 30 minutes to 1 hour. Proceed as directed.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

The perfect sherbet recipe is a cross between sorbet and ice cream, containing fruit, sugar, and dairy but no egg yolks. Like its foreign cousin, sorbet, sherbet should taste vibrant and fresh. In the case of sherbet, however, its assertive flavor is tempered by the creamy addition of dairy. Ideally, it is as smooth as ice cream but devoid of ice cream’s richness and weight. We began with classic orange sherbet. For bright flavor, we started by combining fruit zest and sugar in a food processor before adding 2 cups of orange juice. A small amount of alcohol ensured the sherbet had a smooth, silky texture, and whipped heavy cream lightened the texture of our frozen dessert. To guarantee sherbet with an even consistency, we prepared it in an ice cream machine and then came up with variations with lime, lemon, and raspberries.

START WITH FRESH FRUIT Commercial rainbow sherbet holds a certain appeal, until you actually taste it. If you want sherbet that tastes like fruit, you need to make it yourself, and you have to start with real fruit. For orange, lime, and lemon flavors, you need the zest (which has a good deal of flavorful oils) as well juice. For raspberry sherbet, you need whole fruit (frozen berries are fine).

ADD SUGAR AND CREAM Sherbet requires sugar and a little cream. There are no eggs. (This is what makes sherbet more refreshing than ice cream.) And the amount of dairy is quite small—less than 1 cup of dairy for a quart of sherbet. (A quart of ice cream has 3 cups of dairy.) We found it best to dissolve the sugar right in the fruit juice to make a concentrated base (no water needed). As for the dairy, we like 2⁄3 cup of cream—there’s less water in cream so it makes the sherbet less icy than versions we tested with half-and-half or milk.

GRIND ZEST AND SUGAR To maximize fruit flavor, we found it best to grind the zest with the sugar in a food processor, then add juice, and strain. Oranges and raspberries need a boost from lemon juice (limes and lemons are fine on their own). We add a pinch of salt to balance sweet and tart flavors.

USE BOOZE You can only add so much sugar before the sherbet becomes too sweet. Unfortunately, that amount of sugar doesn’t yield the ideal texture (for more on the role of sugar in frozen desserts, see “Role of Sugar in Freezing”). We tried a variety of tricks used in other recipes to keep the sherbet soft—beaten egg whites, gelatin, and corn syrup—but we ended up preferring a little booze. Like sugar, alcohol lowers the freezing point of the sherbet mixture. In small amounts, you can’t taste the alcohol (we use just 2 teaspoons of triple sec or vodka) but it does have a significant effect on texture without affecting sweetness.

WHIP THE CREAM We tried one last refinement—whipping the cream—to make the finished product lighter and smoother. We found it best to chill the strained liquid base (you want to start with a cold mixture whenever making any frozen dessert; see Vanilla Ice Cream), and then fold the whipped cream into the chilled base right before it goes into the ice cream machine.

CHURN IN A MACHINE An ice cream machine is essential when making sherbet. As with our Vanilla Ice Cream, you need a machine to beat in air and to make the texture lighter and smoother.