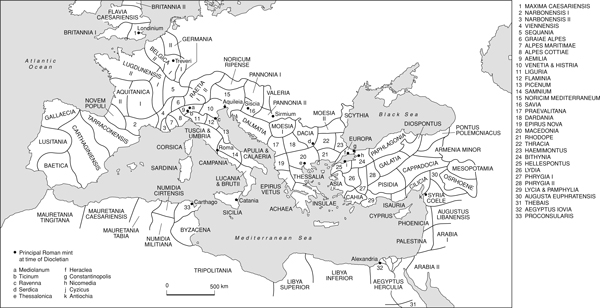

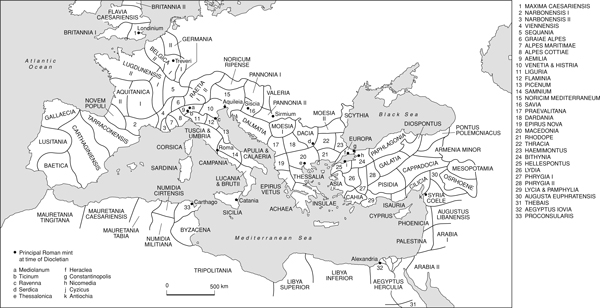

Map 0.1 The Diocletianic provinces of the late Roman empire

Part I: Approaching the Period

The division between East and West

In the year AD 395 the Emperor Theodosius I died, leaving two sons, both of whom already held the rank of Augustus. Arcadius became emperor in the east and Honorius in the west. From then on the Roman empire was effectively divided for administrative purposes into two halves, which, as pressure on the frontiers increased through the fifth century, began to respond in significantly different ways. AD 395 was therefore a real turning point in the eventual split between east and west.1

Until then, and since the time of Diocletian (284–305), the late Roman empire had been a unity, despite having at times a multiplicity of emperors, and embracing all the provinces bordering on the Mediterranean and much more besides (Map 0.1). While Constantine had made himself sole emperor by eliminating his rivals, and thus destroyed the tetrarchic system from which he had emerged himself, there were often multiple emperors in the fourth century, and the idea that emperors had their own territorial spheres and bases was not new. However, Theodosius himself (379–95) had not hesitated to move from Constantinople to the west when it was necessary to deal with potential challenges, and there had not been a formal division. In the west the empire stretched as far as Britain and included the whole of Gaul and Spain, while in the north the frontier extended from Germany and the Low Countries along the Danube to the Black Sea. Dacia, across the Danube, annexed by Trajan in the early second century, was given up at the end of the third after a series of Gothic invasions, but otherwise the empire of Diocletian was impressively similar in extent to that of its greatest days in the Antonine period. To the east, it stretched to eastern Turkey and the borders of the Sasanian empire in Persia, while its southern possessions extended from Egypt westwards to Morocco and the Straits of Gibraltar; Roman North Africa (modern Algeria and Tunisia) was one of the most prosperous parts of the empire during the fourth century.

Map 0.1 The Diocletianic provinces of the late Roman empire

In Diocletian’s day, though Rome was still the seat of the senate, it was no longer the administrative capital of this large empire. Emperors moved from one base, or ‘capital’, to another – Trier in Germany, Sirmium or Serdica in the Danube area or Nicomedia in Bithynia – taking their administrative apparatus with them. By the end of the fourth century, however, the main seats of government were at Milan in the west and Constantinople in the east. The empire was also divided linguistically, in that while the ‘official’ language of the army and the law remained Latin until the sixth century and even later, the principal language of the educated classes in the east was Greek.2 But Latin and Greek coexisted with a number of local languages, including Aramaic and Syriac in Syria, Mesopotamia and Palestine, and Coptic in Egypt (demotic Egyptian written in an alphabet using mainly Greek characters) as well as the languages of the new groups which had settled within the empire during the third and especially the fourth century, in particular Gothic.3 By the late sixth century, Arabic was also beginning to emerge (Chapter 9). Even in the early empire, laws had circulated in the east in Greek, and there had always been translation of imperial letters and official documents, so that on the whole the imperial administration had managed to operate successfully despite such linguistic variety. But from the third century onwards local cultures began to develop more vigorously in several areas; the eventual divide between east and west also became a linguistic one (as has often been noted, Augustine’s Greek was not perfect, and his own works, in Latin, were not read by Christians in the east), but especially in the east, language use was in practice highly complex.

The period covered by this book saw a progressive division between east and west, in the course of which the east fared better. Even though it had to face a formidable enemy in the Sasanians, its economic and social structure enabled it to resist extensive barbarian settlement far more successfully than the western empire could do; there was no ‘fall of the eastern empire’ in the fifth century, and the institutional and administrative structure remained more or less intact until the Persian and Arab invasions in the late sixth and seventh centuries. The east was also more densely urbanized and from the fourth century onwards the Near Eastern provinces achieved an economic prosperity and size of population unparalleled until modern times. Nevertheless many details remain debated, and the sheer volume of recent archaeological evidence makes this one of the fastest developing scholarly areas in the period. Though poorly documented, the Persian invasion and occupation in the early seventh century has been thought to have had a severely negative effect, especially on the cities of Asia Minor, but in Syria and Palestine its impact is hard to trace in the archaeological record, and Umayyad Syria remained prosperous; similarly, little if any archaeological damage can be securely attributed to the Arab conquests (Chapter 9). In the west, by contrast, the government was already weak by the late fourth century, and the power of the great landowning families correspondingly strong. Furthermore, the western provinces had been badly hit earlier by the invasions and civil wars of the third century. The defeat of the Roman army at Adrianople in AD 378 (see below) was a symbolic moment in the weakening of the west, and pressures grew steadily until in AD 476 the last Roman emperor ruling from Italy was deposed; this date therefore traditionally marks the ‘fall of the western empire’. The eastern Emperor Justinian’s much-vaunted ‘reconquest’ (Chapter 5), launched from Constantinople in the 530s, aimed at reversing the situation, but was only partially successful. North Africa remained under Byzantine rule until the late seventh century, and a Byzantine presence was maintained in Italy in the face of Lombard incursions, based round the exarchate of Ravenna, but the west remained divided in the late sixth century, the Merovingian Franks ruling in France and the Visigoths in Spain. In Italy itself, the eventual but very hardwon Byzantine victory hailed in the settlement known as the ‘Pragmatic Sanction’ of AD 554 and accompanied by concerted attempts to impose orthodox Christianity, not least in Theoderic’s capital at Ravenna, met with a new challenge from the Lombards; the Fifth Ecumenical Council held by Justinian in Constantinople in 553 received a negative reception in Italy, and the papacy, especially under Gregory the Great (590–604), acquired considerable secular power in the context of increasing fragmentation. All the same, much that was recognizably Roman survived in the barbarian kingdoms, and the extent of real social and economic change is still debated.4

The debate about periodization (when did the ancient world come to an end?) is livelier than it ever was. On the one hand, we have the concept of a ‘long’ late antiquity, with continuity observable even as late as the Abbasid period,5 on the other, a reassertion of the ‘fall’ of the Roman empire in the fifth-century west.6 However, Christopher Wickham’s magisterial book, Framing the Early Middle Ages. Europe and the Mediterranean, 400–800 (2005),7 avoids such choices, while also providing a comparative analysis of overall trends which affected both west and east. Peregrine Horden and Nicholas Purcell, The Corrupting Sea. A Study of Mediterranean History (2000), also avoid periodization, by concentrating on continuities over very long periods. For Peter Heather, the story of the first millenium is that of the transition from a Roman, Mediterranean hegemony to the beginnings of Europe.8 Whether the notion of a Mediterranean world really does work for late antiquity, or whether this is an example of ‘Mediterraneanism’, rather like Orientalism,9 is a topic to which we will return at the end of this book.

Previous Approaches

The transition from classical antiquity to the medieval world was the subject of Edward Gibbon’s great work, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1787), and very few themes in history have been the subject of so much hotly debated controversy or so much partisan feeling. For Marx and for historians in the Marxist tradition, the end of Roman rule provided cardinal proof that states based on such extreme forms of inequality and exploitation as ancient slavery were doomed eventually to fall. On the other hand, many historians, including Gibbon himself, and the Russian historian M.I. Rostovtzeff, who left Russia in 1917, also saw the later empire as representing a sadly degenerate form of its earlier civilized and prosperous self, which (like Gibbon) they regarded as having reached its apogee under the Antonines in the second century AD. Rostovzeff applied to Rome the lessons he had taken from the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, and saw the later Roman empire as a repressive and uncouth system which had emerged through the destruction of the ‘bourgeoisie’ by the peasants and the army, an example of state control at its worst.10

In English scholarship the period covered in this book has been dominated by A.H.M. Jones’s massive work, The Later Roman Empire 284–602. A Social, Economic and Administrative Survey (Oxford, 1964), also issued in shortened form as The Decline of the Ancient World (London, 1966). Jones was much influenced by the emphasis given by Rostovtzeff to social and economic factors, and his great work consists in the main of thematic chapters on individual aspects of late Roman society rather than political narrative. Jones had travelled extensively over the Roman empire, and taken part in archaeological work, but he wrote before the explosion of interest and activity in late Roman archaeology and made little use of archaeological evidence himself; instead, he demonstrates a incomparable mastery of the written material, and this means that his book remains a fundamental guide. Jones defined the period chronologically as reaching from the accession of Diocletian (AD 284) to the death of Maurice (AD 602), a choice of coverage which the first edition of this book essentially followed but which I believe now needs to be extended in order to take account of the trends in current scholarship.11

Jones’s approach was pragmatic and concrete; he was not very interested in the questions of religious history which many now regard as primary and exciting factors in the study of late antiquity. For him, studying the development and influence of the Christian church in this period meant following its institutional and economic growth rather than the inner feelings of Christians themselves. He looked to Christian writing principally for social and economic data, and most famously, he included Christian monks, ascetics and clergy in the category of ‘idle mouths’ who now had to be supported by the dwindling class of agricultural producers, and who in Jones’s view contributed to the difficulties to be faced by the late Roman government, and to its eventual decline. J.H.W.G. Liebeschuetz’s book, The Decline and Fall of the Roman City (2001), is a modern treatment which returns to the theme of Christianity as a negative factor in the history of the Roman empire.

Jones’s work opened up the period to a new generation of English-speaking students. They were soon to be stimulated by the very different approach of Peter Brown, vividly expressed in his brief survey The World of Late Antiquity (1971), published only a few years after Jones’s Later Roman Empire. Brown is altogether more enthusiastic, not to say emotive, in emphasis. Instead of dry administrative history, ‘late antiquity’ now became an exotic territory, populated by wild monks and excitable virgins and dominated by the clash of religions, mentalities and lifestyles. In this scenario, Sasanian Persia in the east and the Germanic peoples in the north and west bounded a vast area within which several new battlelines were being drawn, not least between family members, as individuals wrestled with the conflicting claims of the church and their own social background. Great new buildings, churches and monasteries epitomized the rising centres of power and influence; the Egyptian and Syrian deserts became the home of several thousand monks of all sorts of backgrounds, and the eastern provinces a heady cultural mix, ripe for social change.

This very different perspective has attracted criticism for being based largely on the evidence of religious and cultural development and failing to do justice to economic and administrative factors.12 But it has had immense value as a stimulus to further work and to the establishment of ‘late antiquity’ as a field of study in its own right. One of the most notable and important developments in this field in recent years has also been the amount of interest shown in the period by archaeologists, especially after pioneering work done since the 1970s on the dating sequences of late Roman pottery, which together with a more rigorous approach to excavation made possible an accurate chronology for late Roman sites. One should also mention the level of interest shown at present in urban history, which is especially relevant to this period, the latter part of which saw a basic transformation in urban life, and indeed the effective end of many, though certainly not all, classical cities in the eastern Mediterranean (Chapter 7). The synthesis of the new archaeological material often remains incomplete – some is badly published or still awaiting publication – and in many cases the interpretation is controversial, but no historian of the period can ignore it.13

One of the striking features of Brown’s World of Late Antiquity was the use it made of illustrations and visual evidence, yet visual evidence has proved more difficult for historians to use than archaeological, perhaps because art history as a specialist field has been perceived to rest on different methodological principles. It has also been difficult to escape the deep-rooted assumption of a clear-cut distinction between Christian and non-Christian art, and the corresponding notion that late antique art represented a step towards a more spiritual, because more religious, style. The work of Jas Elsner and others offers an important corrective,14 as have several exhibitions emphasizing objects from the secular sphere and ‘daily life’ over religious art. The concept of material culture, more neutral than ‘Christian’, or classical, seems to offer a promising way round this problem, but materialist approaches to this period find it difficult to accommodate the huge amount of evidence for religiosity and religious change. There needs to be a synthesis between these approaches and that of cultural history, which has its own problems in finding a satisfactory explanation of religious change.15

‘Late Antiquity’

The terminology used by scholars for historical periods, in this case terms such as ‘late antiquity’, ‘medieval’ or ‘Byzantine’, is on one level largely a matter of convenience. However, the question of where to draw a line between the later Roman empire, or late antiquity, and Byzantium has proved difficult. Many books on Byzantium choose the inauguration of Constantinople by Constantine (AD 330) as their starting point, since Constantinople remained the capital of the Byzantine empire until its fall in 1453, but others only begin with the sixth or seventh centuries. From a quite different perspective, western theologians tend to place a major break at 451, the date of the Council of Chalcedon; however, this is to exclude the large and growing amount of scholarship – historical as well as theological – that deals with the eastern church in the period that saw the rise of Islam. Readers of this book may therefore find that they will also be consulting modern works which at first sight seem to belong to other disciplines or specialisms, and should not be put off by a seemingly irrelevant title.

Terminology does matter, and whether we like it or not, it shapes our perceptions, especially of controversial issues. The title of this book, The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity, invites consideration of the two concepts ‘Mediterranean’ and ‘late antiquity’. The first will be discussed further in the Conclusion. As for ‘late antiquity’, this is a term which has come to denote not simply a historical period but also a way of interpreting it – ‘the late antiquity model’, or what I have called elsewhere for shorthand ‘the Brownian model’, since it has been so much associated with the work of Peter Brown. As suggested already, this has been an enormously fruitful way of looking at the period, and has the great advantage of avoiding the ‘decline and fall’ scenario, but it does not preclude critical approaches or changed emphases, as is clear from several of the contributions to Philip Rousseau’s Companion to Late Antiquity. I hope that these will become clear in the chapters that follow.

The Sources

The source material for this period is exceptionally rich and varied, including both the works of writers great by any standards, and plentiful documentation of the lives of quite ordinary people. Changing circumstances also dictated changes in contemporary writing: St Augustine, for example, was a provincial from a moderately well-off family, who, having made his early career through the practice of rhetoric, became a bishop in the North African town of Hippo and spent much of his life not only wrestling with the major problems of Christian theology but also trying to make sense of the historical changes taking place around him. Instead of a great secular history like that of Ammianus Marcellinus in the late fourth century, Augustine’s Spanish contemporary Orosius produced an abbreviated catalogue of disasters from the Roman past which was to become standard reading in the medieval Latin west, while numerous calendars and chronicles tried to combine in one schema the events of secular history and the Christian history of the world since creation. In the sixth century one man, the Roman senator Cassiodorus, composed Variae, the official correspondence of the Ostrogothic kings, a history of the Goths, and later, after the defeat of the Goths by the Byzantines in 554, his Institutes, a guide to Christian learning written at his Italian monastery of Vivarium in Caiabria. The history of the Goths was written in Latin in Constantinople by Jordanes, and has been the subject of important recent scholarship, though recent years have seen a corrective to the previously strong influence of Jordanes’s account on modern views about the Goths (Chapter 2).16 A century earlier Sidonius Apollinaris, as bishop at Clermont-Ferrand in Gaul, had deplored barbarian rusticity and continued to compose verses in classical style. A host of Gallic ecclesiastics in the fifth century, especially those connected with the important monastic centre of Lérins, wrote extensive letters as well as theological works, and this was also the age of the monastic rules of John Cassian and St Benedict. At the end of the sixth century, the voluminous writings of Pope Gregory the Great, the lively History of the Franks and hagiographical works by Gregory of Tours, another bishop of Roman senatorial extraction, and the poems of Venantius Fortunatus, combine with other works to provide a rich documentation for the west in that period. Two other great figures in the intellectual and theological history of the early medieval west were Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636) and Bede (672/3–735), author of the history of the English church. In 668 Theodore of Tarsus (602–690), an easterner who had studied in Constantinople, became Archbishop of Canterbury, and established a school and scriptorium there for the copying of manuscripts.

The Greek east was even more productive. Secular history continued to be written in the classical manner, and although the works of several fifth and sixth-century writers survive only in fragments, we have all eight books of the History of the Wars in which Procopius of Caesarea recorded Justinian’s wars of ‘reconquest’. Procopius is undoubtedly a major historian; in addition, his Buildings, a panegyrical account of the building activities of Justinian, provides an important checklist for archaeologists, while his scabrous Secret History, immortalized by Gibbon’s description of it, has provided material for nearly a score of novels about the variety artiste who became Justinian’s wife, the pious Empress Theodora (Chapter 5). With its greater cultural continuity, the east was better able than the west to maintain a tradition of history-writing in the old style, and it continued until Theophylact Simocatta wrote under the Emperor Heraclius about the Emperor Maurice (AD 582–602).17 Other writers, however, composed ecclesiastical history, including in the fifth century Socrates and Sozomen, both of whom continued Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History in Constantinople in the 440s, the Syrian Theodoret, bishop of Cyrrhus, and the Arian Philostorgius, whose work is only partially preserved. In the late sixth century the tradition was continued, again in Constantinople, by the Chalcedonian Evagrius Scholasticus, writing in Greek, and the Miaphysite John, bishop of Ephesus, writing in Syriac.18 The Christian world-chronicle characteristic of the Byzantine period also begins now, with the sixth-century chronicle of the Antiochene John Malalas, ending in the year 563, and there are very many saints’ lives in Greek and Latin, and sometimes in other languages such as Syriac, Georgian, Armenian or Ethiopic; the frequency of translation to and from Greek and eastern languages, especially Syriac, is a very important aspect of eastern culture in this period.

An enormous number of saints’ lives (the genre known as hagiography) survive from this period, after the example set by Athanasius’ unforgettable Life of Antony (c. 357–62), and this material has provided the stimulus for some fine recent work. Saints’ lives can provide historical information, but they are also invariably written with an apologetic purpose, and many are based on the rhetorical structure of encomium or panegyric. They therefore need to be used with caution by the historian, though they also provide very important ways into social and cultural questions. Indeed, the recognition of the great importance of rhetoric in all forms in the interpretation of late antique writing has been one of the major advances since 1993, as instanced in many contributions to the influential Journal of Early Christian Studies. Saints’ lives are also well represented among the texts covered in the series Translated Texts for Historians, which at the time of writing has published more than sixty volumes. Designed to make important, but otherwise hard to find, texts available in reliable translations and with annotation, this wide-ranging series is one of the most important factors in making late antiquity so accessible a field. The impact of its recent publication of the entire Acts of the Council of Chalcedon (451), followed by those of the Second Council of Constantinople in 553,19 a major departure for the series, is already evident.

In addition to the abundant written sources, there is a wealth of documentary material, ranging from the proceedings of the major church councils (Ephesus, 431, Chalcedon, 451, Constantinople, 553) to the law codes of Theodosius II and Justinian. The acts of the second council of Ephesus (449) are known from the proceedings of the Council of Chalcedon two years later, and partly survive in Syriac (Chapter 1). The official document known as the Notitia Dignitatum, drawn up some time after AD 395 and known from a western copy (see Jones, Later Roman Empire, Appendix II), constitutes a major source for our knowledge of the late Roman army and provincial administration. There is also a large and increasing number of dedicatory inscriptions from the Greek east in the fifth and sixth centuries, sometimes written in classicizing Greek verse, and while major public inscriptions are few in comparison with their number in the early empire, large numbers of simple Christian funerary epitaphs survive, often inscribed in mosaic on the floors of churches, which also frequently carry dedications by the builder or the local bishop. In churches of the Near East these are sometimes written in Aramaic or Syriac. The first inscriptions in Arabic script begin to appear in the sixth century. Important papyri also survive from the desert region of the Negev in modern Israel, from Petra in Jordan and from Ravenna in Italy, as well as from Egypt. Language change, especially as demonstrated in the epigraphic evidence, is a major concern of current scholarship.20 Finally, the archaeological record is now huge, and increasing all the time, and while it is still necessary to consult individual excavation reports, more and more recent publications provide overall or regional surveys of archaeological evidence; these are noted at suitable points below, especially in Chapters 7 and 8.

Main Themes

A major issue in the period is that of unity and diversity. In what sense is it still possible to think of a ‘Roman’ world after the fifth century? Some would say that there was already a major downturn in prosperity, especially in the west, and with it the disappearance of the traditional Roman elite lifestyle. There is evidence to support such a view, especially from Britain, which Rome ceased to regard as a province in 410. Bryan Ward-Perkins has memorably described what happened as ‘the disappearance of comfort’.21 A major programme of building under Anastasius (491–518) and especially Justinian (527–65) partly explains the survival of sixth-century basilicas (and fortifications) at many sites in the Balkans, but by the end of the century new threats, combined with economic decline, were leading to a retreat in many places to more secure hilltop fortifications. The important city of Thessalonica suffered particularly badly from Slav attacks in the seventh century, and Constantinople was threatened by Huns in 559 and besieged by Avars and Persians in 626. Justinian’s fortifications did not protect the Peloponnese, and a general economic downturn is posited by c. 700 by Michael McCormick (see also Conclusion).22

On the other hand, a wealth of evidence shows that the eastern provinces, and especially the Near East, continued to prosper. While the Persian wars of the sixth century and Persian invasion of the early seventh century brought major damage to some urban centres, such as Antioch and Sardis, other cities, such as Scythopolis (Bet Shean in Israel), show little sign of decline until the eighth century, while the Arab conquests hardly show in the archaeology of the Near East.23 The state of these provinces on the eve of Islam and the degree of continuity and change that can be traced in the Umayyad period is one of the liveliest issues in current scholarship, and recent work suggests that there was considerable local variation; a micro approach is needed. The question of whether the development of Islam does indeed belong in the context of late antiquity, as argued by a growing number of late antique scholars, is also being challenged by some Islamicists;24 it is also noticeable that important developments under the Umayyads in the east, in Iraq and the former Persian empire, are not usually central in the scholarship on late antiquity, though they too are part of the story of continuity and change. Perhaps the days of grand generalizations about the end of antiquity are over.

The title of this book also evokes a current debate: in what sense can or should we talk of a ‘Mediterranean’ society, and indeed, if this is permissible, how is that affected by this apparently increasing divergence between west and east? I will return to these questions in the Conclusion. Meanwhile it will be enough to refer to some of the responses to Horden and Purcell’s first volume, The Corrupting Sea.25

Other major themes to be considered must include what has commonly been seen as the process of Christianization, although a better formulation in the light of current work would be religious change, encompassing the relations between a whole variety of religious groups, the degree of local variation, questions of religious identity and especially self-identity, the history of Judaism in the late Roman empire, and especially in Palestine on the eve of Islam, and the context and processes which gave rise to another major religion of the book. Far more has been written on all these subjects since the publication of the first edition of this book, not least perhaps under the stimulus of external events. But the discovery of rich new material, including for instance pre-Islamic monotheistic inscriptions from south Yemen, and the publication of studies of spectacular synagogues in Palestine, notably at Sepphoris, have also made new interpretations possible. A hugely increased scholarly interest has also developed in the divisions in the eastern church after the Council of Chalcedon, drawing especially on the very rich written evidence in Syriac sources (Chapters 5, 8 and 9).

Diversified, localized and fragmented, the Roman army, or rather armies, of the fifth and sixth centuries were far different in composition and equipment from those of earlier days. Whether the army could now effectively keep out the barbarians, and if not, why not, were questions as much debated by contemporaries as by modern historians; the nature of the late Roman army, and the context of defence and frontiers, together with the new revisionist approaches towards the barbarian invasions, need therefore to be discussed again (Chapters 2, 5 and 8).

Finally, the late Roman economy (Chapter 4). How much long-distance exchange continued and for how long, and if it did, in whose hands was it? Large estates and landowners are argued by some to be more important players than has recently been assumed, while the traditional problem of the status of ‘coloni’ has been subjected to radical new interpretations. In the Near East, the reasons for the prosperity of hundreds of ‘dead villages’ in Syria, some of whose remains can be clearly seen, with stone houses and public buildings still standing to their upper levels, are still not fully understood; yet the local population was clearly able to engage in fairly elaborate forms of exchange. Christopher Wickham has stressed the effects of the ending of the annona system in the early seventh century, and the impact of the seventh-century invasions included a massive loss to the eastern empire of basic tax revenue. In Umayyad Syria, the Muslims instituted a completely different tax system, and as their priorities crystallized, elements of the Roman provincial structure inevitably began to weaken. But many questions remain about economic life towards the end of our period, and this perhaps cautions more than anything else against the too easy absorption of the early Islamic world into that of late antiquity.

The Fourth Century

Although the overall period covered in this book begins only in 395, it will be useful to provide a short introduction to the fourth century.26 Traditionally, and certainly in English-speaking scholarship since Jones’s Later Roman Empire, the ‘later Roman empire’ has been thought of as beginning with the reign of Diocletian (284–305). A strong division was made between the mid-third century, seen as a time of civil strife, usurpation and financial crisis manifested in debasement of the coinage and spiralling prices, or even the virtual collapse of the monetary economy, and the era which followed, when policies associated with Diocletian led to greater bureaucratization, attempts to control prices by law, an attempted power-sharing between two Augusti and two Caesars, collectively known as the ‘tetrarchs’, and a new division of the provinces and separation of civil and military rule, together with a much increased pomp and ceremony surrounding the imperial court (‘an Oriental despotism’).27 The extent of the so-called ‘third-century crisis’ remains debated, and some recent works also resist this sharp dividing line and lay emphasis on the connections between the later empire and what went before.28 ‘Late antiquity’ as defined by Peter Brown in The World of Late Antiquity of 1971 (subtitled From Marcus Aurelius to Muhammad) is generously envisaged as inclusive at both ends of its chronological range.

Scholars are still divided on whether the reign of Constantine (306–37, sole reign 324–37) represented a ‘revolution’, or substantially continued trends already evident during the immediately preceding period.29 Constantine’s famous ‘conversion’ before his defeat of Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in AD 312 and his religious stance and policies are still at the centre of the debate, which shows no sign of abating, but the administrative, financial and military aspects of his reign are also important. Constantine himself was a product of the tetrarchic period. He was the son of Constantius Chlorus, who had risen through the army to be promoted by Diocletian to Caesar and subsequently became Augustus, and had successfully circumvented the hostility of his rivals to have himself declared Augustus by his father’s troops when the latter died at York in 306; the years 306–312 were spent eliminating rival contenders in the west, and his final defeat of Licinius, emperor of the east, in AD 324, made him sole ruler of the empire. This spelled the end of the tetrarchic system introduced by Diocletian; instead, Constantine adopted a dynastic policy for the succession. He promoted his own sons to the rank of Caesar and at the end of his life he initiated a new settlement in the hope of guaranteeing the succession. These hopes were not realized, but after 324, Constantine had been able, as no other emperor had been able to do for many years, to preside over a more secure and settled empire.

Constantine’s victory in 324, followed by the death of Licinius, was marked by the immediate issue of important legislation reinforcing the new security already offered to Christians.30 But Constantine had not waited until 324 to introduce change; already in the winter of 312–13 he intervened in disputes between Christians in North Africa, calling a meeting in Rome to settle them, and then a council at Arles in 314. The issues were not new, especially in North Africa: the question was how the church should treat the lapsi (compromisers) in the aftermath of persecution. It was thus a very modern problem, with church property and careers at stake, and North Africa was not the only part of the empire where these divisions showed themselves. However, this early effort on Constantine’s part at solving inter-Christian disagreements was unsuccessful, and in 315 we find him threatening the persistent hardline ‘Donatists’. By 321, under pressure of other concerns and apparently realising the limits of practicality, he advised the mainstream catholic Christians in North Africa to be patient and wait for God to bring justice. But the great Council of 411, at which St Augustine was prominent, shows that the Donatist and catholic division in North Africa remained a major problem throughout the fourth century, and even the strong measures taken at that time failed to eliminate Donatism completely. By 324, Constantine had learned from his earlier mistakes. He now called a much bigger council of bishops, to meet at Nicaea and settle a further dispute identified with the views of an Alexandrian priest called Arius about the relation of the Son to the Father in Christian theology. This time the meeting resulted in a statement of faith, to which all had to subscribe, and which was eventually to become enshrined as the Nicene Creed; public resources were deployed, and the few who refused to sign the Council’s statement were exiled. The Council of Nicaea took on an iconic status: the number of those attending was soon claimed to have reached 318, an improbably high figure, but the same as that of the servants of Abraham, and Theodoret of Cyrrhus, writing in the fifth century, told an affecting story of how some of those present had been mutilated in the persecutions. When Constantine invited the assembled bishops to dinner, it was claimed that he even kissed the eye sockets of some who had been blinded.31

These were powerful precedents for the subsequent position of the church, its bishops and Christians generally in the empire, but they did not make the empire officially Christian, as many still imagine. However, Constantine also set about building churches, at first on the sites of Roman martyr shrines and, in the case of the Lateran basilica, on the site of the demolished barracks of the imperial guard of his defeated enemy Maxentius. This huge basilica was to be the seat of the bishop, and was sited away from the main existing Christian areas but near an imperial palace. We know about Constantine’s Roman churches and the donations he made to them mainly from a sixth-century history of the bishops of Rome, and some, including St Peter’s on the Vatican hill, may have been built by his successors rather than Constantine himself. Yet while even in the time of persecution there were certainly some substantial church buildings, Constantine’s imperially sponsored churches in Rome, Antioch, Jerusalem and elsewhere in the Holy Land instituted a new development in architecture and in Christian visibility. It is interesting therefore, that in his newly refounded city of Constantinople (‘the city of Constantine’), begun after his victory over Licinius in 324, he seems to have concentrated on the secular buildings needed for an imperial centre rather than the panoply of churches we might have expected (Chapter 1). Constantine was a traditionalist as much as an innovator. He seems to have had a special sense of affiliation towards the sun god, and much of his legislation on matters affecting religion was ambiguous; after all, more than 90 per cent of the population was still pagan. Nor was religion his only or even perhaps most important concern; he also continued Diocletianic precedent, if with developments of his own, in military and administrative matters. He turned to members of elite Roman senatorial families in building his administration while also expanding the senatorial order and cutting its territorial connection to the city of Rome. If the empire’s financial stability improved during his reign, this had much to do with increased security. A new gold coin, the solidus, was introduced under Constantine, allegedly made possible by the availability of gold confiscated from temples, but also by special taxes on the rich; it remained the highest value currency in the Byzantine empire for many centuries, but the problem of inflation of the base metal coinage used by most people was not so easily solved.

Constantine was controversial in his own day and is still an iconic figure, as demonstrated by several exhibitions held to commemorate the 1700th anniversary of his proclamation at York. For many, his support of Christianity will always be the most important thing about him. But he deserves a broader and more objective approach; in particular he invites comparison with Augustus, as an emperor who also came to power by eliminating his rivals in civil war, and found subtle ways of dealing with division and hostility within the upper class. Each succeeded in establishing a new elite, and each was a master of public relations. In each case too, religious change was a feature of their reign, but in both cases it was embedded in a broader context.

Constantine also resembled Augustus in that he failed to ensure a smooth succession. His death in 337 while en route to campaign against Persia was followed by an awkward period of uncertainty before his three surviving sons were all declared Augusti. In the process, the descendants of Constantine’s half brothers, who included the future emperor Julian (361–63) were set aside or even eliminated. Constantine’s sons promptly turned on each other in civil conflicts which continued until Constantius II (337–61) emerged as sole emperor in 353.32 Constantius continued his father’s policy of intervention in church affairs, but in a context of reaction against the decisions taken at the Council of Nicaea. Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria and a strong pro-Nicene supporter and propagandist, had already been exiled in the last years of Constantine and was condemned several times by church councils, and exiled twice more under Constantius. However, ‘Arianism’ is a term that strictly denotes a whole spectrum of theological understanding rather than a single position. The Council of Nicaea had resulted in a statement according to which the Son was of the same substance (homoousios) as the Father, but dissatisfaction with this formula was now represented by groups variously known as Anomoeans or Homoeans. Constantine himself had veered away from the Nicene position before his baptism and death in 337 and this continued under his son and successor Constantius II. The disputes continued until the Council of Constantinople called by Theodosius I in 381, the second ‘ecumenical’ council, which returned to the Nicene formula, and after which the ‘Nicene’ creed ceased to be questioned as the central statement of Christian belief.

Of the three sons of Constantine who gained power after their father’s death in 337, Constantine II had been eliminated in 340 and Constans fell to the usurper Magnentius at Autun in 350. Gallus and Julian, the grandsons of Constantine’s father Constantius II and Theodora, had been regarded up to then as threats to the succession, but Constantius now made Gallus Caesar while he himself moved to crush Magnentius; however, Gallus was killed at Constantius’ orders in 354. As sole ruler, Constantius made a famous visit in 357 to Rome, no longer the seat of government in the west, which was memorably described by the historian Ammianus Marcellinus, whose surviving history is a main and very important source from the year 354.33 The historian was struck by the emperor’s pose of grandeur and impassivity (‘as if he were an image of a man’, Hist. 16.10.10), and this brought out in him all his considerable powers of virtuoso description. The years of Constantius’ sole reign were also occupied in dealing with military threats in the west from the Alamanni and Sarmatians and in the east from the Sasanians, who took Amida (Diyarbakir in eastern Turkey) in 359. He brought back Gallus’ half-brother Julian from his studies at Athens and the latter successfully campaigned as Caesar against the Alamanni, winning a major battle at Strasburg in 357. But in 360 Julian’s troops proclaimed him Augustus in Paris,34 news that Constantius heard while campaigning in the east. There was little likelihood that Constantius would accept Julian as co-emperor, and the latter marched east, entering Constantinople to general acclaim in December 361, a few weeks after Constantius had died in Cilicia.

Julian’s short reign as sole emperor (he died from a spear wound in mysterious circumstances when on campaign against Persia) is one of the most controversial, partly because of his own considerable and self-conscious literary output. Brought up a Christian, at first under the care of Eusebius the bishop of Constantinople, he was later allowed contact with leading philosophers at Ephesus and Athens, and adopted an enthusiastic form of pagan Neoplatonism. Among his writings are a hymn to King Helios and a treatise against Christianity (Against the Galilaeans) and as emperor he attempted to ban Christians from teaching and to organize paganism along the institutional lines adopted by the Christian church. However, he lacked the persuasive and other skills necessary to carry this through, even in a city still full of intellectuals and many pagans such as Antioch, where he arrived from Constantinople in July 362 and where he stayed for some months before setting off on his eastern campaign.35 Not only did Christians such as Gregory of Nazianzus, Ephraem the Syrian and John Chrysostom react violently against this threat; Julian’s eccentricities also managed to alienate the pagan population, who lampooned and jeered at the emperor. He further excited Jews and outraged Christians with an abortive plan to rebuild the Temple at Jerusalem.36 Julian was not easy to assess: his rise inspired pagan philosophers and intellectuals such as Eunapius and Libanius, but the historian Ammianus Marcellinus, who had served as an officer in Gaul and on the Persian expedition in 363, and admired Julian greatly, was also clear-sighted about some of his faults. Julian was the only emperor after Constantine to try to promote paganism, but his personal unpredictability, his lack of tact and his proneness to grand gestures made it unlikely that he could have been successful in reversing the solid gains which Christians now enjoyed, even had his reign lasted longer.

Julian’s death at Samarra, east of the Tigris, left the army dangerously exposed and his successor, Jovian, an obscure cavalry officer, proclaimed by soldiers on the field, immediately had to deal with a major Persian attack. The price of extricating the Romans from this difficult situation included the surrender of Nisibis and Singara on the frontier with Persia, and led to the removal of Ephraem the Syrian from Nisibis to Edessa.37 Jovian survived for only one year and was succeeded by Valentinian I (364–75), a Christian officer originally from Pannonia, also chosen by the army, who within weeks co-opted his brother Valens (364–78) as co-emperor. Their accession marked a new dynastic departure, and they were able to fight off a challenge in Asia Minor from Procopius, another officer, who was related to the Emperor Julian and had been promoted by him; he had even been responsible for burying Julian’s body in Tarsus.38 In a clear dynastic move, Valentinian also made his seven-year old son Gratian consul in 366 and Augustus in 367, as the first of the ‘boy-emperors’. Gratian survived on the throne until he was killed by his own soldiers at Lyons in 383, while attempting unsuccessfully to control the threat to Britain and Gaul mounted by the Spaniard Magnus Maximus; when Valentinian I died in 375 his generals had declared his four-year old son Valentinian II Augustus, and the Spaniard Theodosius I was recalled from exile in Spain and declared Augustus by Gratian in January 379, a few months after Valens was killed on the field in the disastrous defeat of the Roman army by the Goths at Adrianople (below and Chapter 2).

The advent of the Pannonian emperors marked a new and ominous turn. In the first place, as Ammianus’ account made very clear, it brought profound issues about succession and legitimacy to the fore.39 Valentinian was easily presented as uncouth, not least because he kept two she-bears as pets; Valens is compared to a beast of the arena.40 Their reign was also marked by a notorious series of trials of members of the senatorial class on charges which included conspiracy and magic, and which gave Ammianus plenty of scope to underline the cruelty of Valentinian.41 Julian had campaigned to secure the frontier along the Rhine and the Danube, and Valentinian and Valens at first sought to consolidate relations with the Alamanni and Goths by diplomacy. By 369 Valens had adopted a more aggressive stance and forced the Gothic leader Athanaric to sue for peace, ending the subsidies previously paid to them by Rome. But by 376 Gothic envoys had come to Valens in Antioch asking to be allowed to cross the Danube into Thrace; Valens, engaged in preparations for renewed warfare against the Persians, was in no position to refuse, and the Tervingi and Gruethingi crossed the Danube on a mass of boats, rafts and canoes. Ammianus’ explanation is that they were being pushed by movement of the Huns into their own territories42 but the attractions of sharing in Roman prosperity were also a major factor. Roman hopes of peaceful settlement by the Goths, if such existed, were quickly dashed; the Goths began to pillage Thrace and Valens hastily patched up peace with Persia and sent a too-small force to deal with the situation. A battle damaging to both sides was fought in 377, and in 378 Valens engaged the Goths at Adrianople without waiting for the arrival of Gratian and the western army. The result was a disaster for the Romans compared by Ammianus to the Roman defeat by Hannibal at Cannae, with the emperor himself among the dead.43

What used to be called the ‘barbarian invasions’ have been among the most debated issues in late antique scholarship since the publication of the first edition of this book.44 Earlier scholarship was strongly marked by attempts to trace an unbroken Germanic identity, but this and the old idea of massive numbers of German invaders pressing on the frontiers of the empire has given way since the 1990s to the concept of ethnogenesis, referring to the processes whereby barbarian groups gradually acquired a self-conscious identity, largely through their contact with the Romans;45 this has gone alongside a revisionist interpretations of material evidence by archaeologists.46 In the case of the Ostrogoths a self-serving royal genealogy of the Amals was produced by Jordanes, a Gothic writer in sixth-century Constantinople, drawing on an earlier work, now lost, by Cassiodorus. One of the key issues in the current debates concerns the extent to which Jordanes’s account should be used by modern historians.47 The assumptions attached to the idea of ethnogenesis have also come under criticism, and this too centres on the problematic concept of ethnicity. In fact the categories ‘Romans’ and ‘barbarians’ are themselves derived from the tendentious accounts in our Roman sources and did not of themselves correspond to real differences; indeed, the ‘barbarians’ usually aspired to the advantages of being Roman. Using the common designation of ‘Germanic’ imports ethnic assumptions, and even the term ‘barbarian’ is perhaps now best used simply to denote ‘non-Roman’, without ethnic connotations. This sensitivity to issues of identity and self-definition also involves a rethinking of the concept of frontiers, as can be found in much of the scholarship since the early 1990s, for example in the series of conferences with the title Shifting Frontiers. These are difficult issues, and indeed ethnicity and identity remain major topics for both east and west in late antiquity.48 The de-emphasizing of barbarian identities may have been taken too far, and the minimizing of invasion and conflict in the story of Roman-barbarian relations in the west in late fourth and fifth centuries has itself provoked a reaction, notably from Peter Heather and Bryan Ward-Perkins, who again stress the ‘fall’ of the western empire in the fifth century under the pressure of barbarian invasion.49 Both Heather and Ward-Perkins, especially the former, are mainly concerned with the western empire, but are also reacting against what they see as the excessively bland approach established by Brown, The World of Late Antiquity.

According to Ammianus, whose narrative stops at this chronological point, the Goths came dangerously close after their victory at Adrianople to threatening Constantinople itself, but while they had defeated and killed a Roman emperor, capturing the city was far beyond their capacities, and in 381 Roman forces drove them back from Macedonia and Thessaly into Thrace; Athanaric had died in Constantinople early in 381 and was given a ceremonial funeral, and a treaty was concluded in 382; it was accompanied by grants of land. Some contemporaries, including Ambrose, bishop of Milan, realized that these events were the beginning, not the end of Roman difficulties, but the orator Themistius depicts the treaty as an act of far-sighted Roman generosity inspired by the new emperor Theodosius.50

Theodosius I (379–95) spent much of his reign in Constantinople, apart from his move to crush Magnus Maximus in northern Italy in 388, and Eugenius, defeated at the river Frigidus between Aquileia and Emona in 394. Milan, the episcopal seat of Ambrose, was an imperial residence in this period, and Theodosius himself died there in 395, but from the early fifth century Ravenna became the main imperial centre in the west. Theodosius visited Rome in 389, where he was praised in an extant speech by the Gallic orator Pacatus. Valentinian II was expected to base himself in Trier, under the eye of the Frankish magister militum Arbogast, but met his end when Eugenius made common cause with Arbogast and took the title of Augustus. Though he was a Christian himself, his attempt was represented as a pagan challenge to the Christian Theodosius and his young sons Arcadius and Honorius, both now also Augusti, and caused some excitement among the Roman senatorial aristocrats; however, the view put forward by Herbert Bloch in 1963 and maintained by many others thereafter that there was a real ‘pagan reaction’ has now been shown to be fundamentally misconceived.51

The final decades of the fourth century marked a distinct intensification of the Christian offensive. The pro-Nicene Ambrose, bishop of Milan since 374, was a forceful advocate and politician who had to deal with several emperors, their families and their rivals.52 He influenced first Gratian and then Valentinian II to resist the pleas of the senate, led by Symmachus, to restore the altar and statue of Victory to the senate house in Rome, he resisted imperial pressure to favour the Homoeans, and in the case of Theodosius he used his power to deny the emperor communion as a weapon and forced him to do humiliating public penance for the actions of imperial troops at Thessalonica. In Rome another forceful churchman, Damasus, had become pope (bishop of Rome) in 366 amid scenes of public tumult, and in the early 380s was the patron there of the controversial Jerome, while in the east John Chrysostom was preaching in Antioch and became an equally controversial bishop of Constantinople in 398.53 Under the late fourth-century emperors a series of laws were brought in laying down increasingly severe penalties and exclusions, not only on pagans and Jews but also on heretics.54 Penalties against Manichees, ‘Eunomians’, ‘Phrygians’, ‘Priscillianists’ and ‘Donatists’ were laid down in constitutions starting in 381, and similar civil disabilities were also applied to ‘apostates’ from Christianity, whether to paganism or Judaism. It would be a mistake to imagine that this legislation was everywhere enforced, or even that it represented laws applicable to the entire empire. It has come down to us in the Theodosian Code, a highly edited collection made under Theodosius II (408–50). But it had more than symbolic importance. It could be exploited by powerful bishops, who could claim imperial support even more confidently than before;55 it also invited informers to lay charges against individuals, and even allowed the possibility of challenging inheritances from persons alleged to have been Manichees or ‘apostates’. Sometimes it also led to public prosecutions of which detailed accounts remain, as in the case of Augustine’s two public debates with Manichaeans in Hippo in 392 and 404, for which the surviving texts by Augustine are actually records made as part of the legal process.56

By 395 it was possible to feel that the organisational and military changes introduced under the tetrarchy and continued by Constantine had on balance been successful.57 The empire had recovered economic stability and was largely able to maintain and defend its provincial organization; it was even able to conduct offensive wars. But the problem of ensuring a smooth succession to the imperial power had not been resolved, though much effort had been expended on it. The state was now taking, and was willing to take, a far more interventionist approach towards religious change, even if it still had to balance the competing claims of established practice. The Christian church, represented by leading bishops, and indeed also some influential ascetic figures, was far more visible than before. It was also developing systematic mechanisms for defining doctrine, notably through church councils, and this process would continue in the fifth century with the councils of Ephesus (431 and 449) and Chalcedon (451).58 On the other hand, there were already at the end of the fourth century signs of the religious conflict that was to be one of the features of urban life in the fifth century (Chapter 7). Finally, the last decades of the fourth century presented some troubling precedents in relation to the rise to power of a class of military power-brokers, and the likely future problems in dealing with pressure from non-Romans, while in the east the Sasanian state remained a powerful danger to the security of the cities of the eastern provinces.