Figure 6.1 One of the classrooms uncovered at Komm el-Dikka, Alexandria

6

Late Antique Culture and Private Life

The title of this chapter in the original edition of this book was ‘Culture and mentality’. ‘Mentality’ is a concept associated with the French historians and sociologists who together comprised the ‘Annales School’ in the twentieth century, whose aim was to look for deep-seated structures in history over long periods of time, including structures of thought and ideas in particular societies (‘mentalities’). However, this concept, which could be broadly sociological or broadly psychological, has given way to considerations of discourse and power under the influence of Michel Foucault, and of symbols under that of Pierre Bourdieu,1 and given the enormously wide variety of attitudes, beliefs and ideas highlighted by the last generation of writing about late antiquity it cannot be applied in any simple form. Peter Brown’s The World of Late Antiquity, published in 1971, is a book whose approach has often been described as impressionistic or kaleidoscopic, and which presented a world of great variety. In later works Brown himself has turned more to cultural issues and to questions involving discourse and power,2 and many others have taken this emphasis considerably further. Late antiquity used to be seen unproblematically as a time of increased spirituality.3 This too needs to be challenged.

Peter Brown, who would probably best be termed a social historian, has defined the starting point of late antiquity as lying in a ‘model of parity’ which existed among the (male) urban elites of the high empire, with their civic paganism; what emerged from the upheaval of the third century was, on this view, ‘Late Antique man’.4 At the same time he has also suggested that late antiquity saw a distinct shift away from traditional public values towards the private sphere, and, with it, a significant step towards the growth of individual identity. He has also engaged with the suggestion made by the Italian historian Santo Mazzarino that late antiquity saw a ‘democratisation of culture’, a move away from the elite high culture of classical antiquity. Whether this was really the case, and if so how far it may have been connected with the process of Christianization, is a matter of considerable discussion,5 and Brown has also argued against the common tendency to divide late antique culture into elite and popular. If values were changing, how far was this under the influence of Christianity? As we have seen, late antiquity has often been regarded on the one hand as an age of increased spirituality, but on the other of descent into superstition and irrationality. However, after the appearance of Peter Brown’s World of Late Antiquity it would be difficult to find a single ‘mentality’ in this complex, dynamic and extremely varied world.

The period covered in this book was a time of change and variety. The change was at times violent and sudden but more often uneven and gradual, and sometimes hardly perceived by those living through it. The challenge for the historian is to find ways of doing justice to these processes without distorting the enormous mass of surviving evidence. The success of the series of conferences and publications under the title ‘Shifting Frontiers’ is precisely due to its recognition of the problems presented in capturing these multiple processes of change.6 This is all the more the case given the resistance shown in recent scholarship to a one-dimensional emphasis on Christianization in late antiquity, even while recognizing that the Roman empire ‘became Christian’ between the fourth and sixth centuries. If in particular we take a longer chronological view, the religious changes that took place in late antiquity can better be characterized in the words of a recent discussion by Noel Lenski as the process whereby

the kaleidoscopic plurality of religious cults once scattered across the ancient landscape gave way to a homogenization of religious power around the three interrelated Abrahamic traditions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. These squeezed out competing religious traditions by successfully redefining religious truth along monotheistic and theologizing lines, and – in the instance of Christianity and later Islam – by deploying the coercive force of the state as a way to valorize and enforce the truths they purveyed.7

This formulation points to several trends in recent historiography: first, a tendency to place Christianity and the process of Christianization within a broader religious context; second, a recognition of the role played in religious and social change by writing, debate and theological issues, including the enormous weight placed by late antique Christian and Jewish writers (and by Muslim writers, even if considerably later) on exegesis, the interpretation and appropriation of classic texts; and third, an awareness of the place of coercion, whether used by the state or by other agents. It encapsulates the linguistic turn of the 1990s and its move towards a socio-historical paradigm of power and dominance. Lenski’s discussion recognizes the importance of post-colonial approaches in recent scholarship on late antiquity, with a corresponding attempt to get behind the dominant narrative in order to investigate power relations, the dynamics of contemporary discourse, and subjects such as gender history and non-elite groups. The Marxist, structuralist and anthropological approaches familiar in previous decades of historiography on the later Roman empire have been joined by methodologies influenced by Foucault and Bourdieu, and notwithstanding a traditionalist and ‘common-sense’ reactions by some scholars, by a considerably heightened awareness of the literary analysis of textual evidence.8 We have already emphasised the importance of archaeological evidence for any study of late antiquity, but we can also see in some scholars of the period, prominent among them Jas Elsner, an attempt to break down the gulf between textual and visual evidence. Given the wealth of visual evidence for late antiquity and the important developments that can be discerned, this needs to be taken much further.9

The Survival of Traditional Structures

It remains methodologically difficult to integrate these different approaches to late antique culture, and to accommodate both the religious and the secular; a further problem, less often acknowledged, is how far the huge quantity of religious evidence, or the processes of religious change in the period, can actually be reduced to matters of social or cultural history. First, however, we must ask to what extent the traditional high culture was still maintained, a question which is very much connected with urban civic culture.

Late antique secular education was maintained in cities all over the empire, and at the higher level in important centres such as Athens, Antioch, Alexandria, Constantinople and Berytus, the latter a particular centre of legal studies. Well-to-do parents sent their sons to leading teachers and to particular centres: Augustine was first taught in his home town of Thagaste, then sent with the help of a rich neighbour to Madaura, and then to Carthage. Much of his education was in the Latin classical authors, though he also learned Greek, and he went on to teaching posts in Thagaste, Carthage and Rome, from where he was appointed as a teacher of rhetoric in Milan in 384, to be joined there by his Christian mother Monica and several North African friends who were teachers or lawyers. His education included study of philosophy, and he was personally drawn to questions of natural philosophy, astrology and religion. For nearly ten years he was a Manichaean, and before his dramatic conversion back to Christianity under the influence of Ambrose in Milan he was also drawn to Platonism and belonged to an intellectual circle in which serious discussion of both Platonism and Christianity was the norm. The story of his early years story, vividly told in his Confessions, gives us an idea of education and intellectual life in the late fourth century.10 The pattern did not change very much during the fifth century for people like him who came from the better-off classes in urban centres,11 and was reinforced by the founding of the ‘University’ of Constantinople in 425 at the Capitol (not a university in a modern sense, but rather the establishment of teachers in both Latin and Greek in the main fields of grammar, rhetoric, philosophy and law).12 In the sixth century east, Gaza was a major centre of teaching in addition to Constantinople, Athens (see below) and Alexandria; and Berytus remained the main centre of legal studies until hit by a major earthquake in 551.13 Teachers attracted their own followings, and students whose families could afford it chose their centre of higher education according to its teachers.

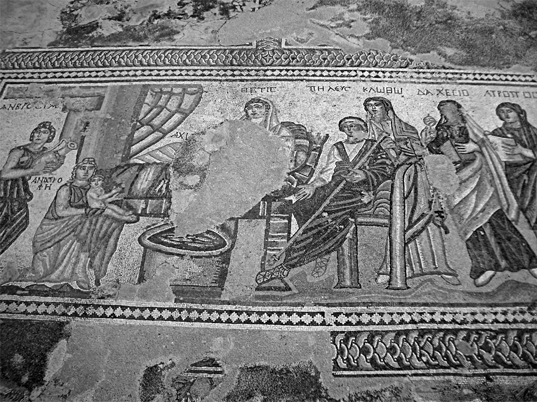

Student life could be rowdy, and at times there was trouble between Christian and pagan students, as in late fifth-century Alexandria, where the Alexandrian teacher Hypatia had been killed in Christian–pagan conflicts earlier in the century (Chapter 1); Zachariah, from Maiuma in Gaza and later bishop of Mytilene, studied grammar and rhetoric in Alexandria and went on to study law at Berytus; he wrote in his Life of the future patriarch Severus about their student days in Alexandria and their adventures with pagan students including Paralius from Aphrodisias in Caria, a small and remote city from which we happen to have good evidence for the persistence of paganism and the educational opportunities open to young men from the better-off families. The interplay of religious affiliation with education is vividly illustrated by the fact that one of Paralius’ brothers was a Christian and lived at the time in a monastic complex near Alexandria, and the fact that while pagan and Christian students studied together, religious rivalry sometimes erupted into violence.14 The extent and organization of higher education in Alexandria has been spectacularly revealed by the excavation of an extensive late antique urban complex in the city, in the area known as Komm el-Dikka, where a large number of classrooms are preserved, where the pupils declaimed or performed their exercises in front of their teacher and fellow students.15

Teachers were needed to perpetuate the system, while in turn training in classical rhetoric was regarded as an essential qualification for the imperial bureaucracy and indeed for any secular office. We can see the process clearly in the mid-fourth century, when Constantine’s new governing class was very much in need of a brief tutorial in Roman history, and again a generation or so later, when the provincial rhetor Ausonius shot to prominence as praetorian prefect and consul, and the Egyptian poet Claudian became chief panegyrist of Stilicho and Honorius. Literary figures who became prominent in the fifth century included the historian Olympiodorus from Egyptian Thebes, who described himself as ‘a poet by profession’, and who was a pagan, well educated in the classical tradition and much-travelled, distinctly more enterprising than most of his peers. Priscus, another fifth-century Greek historian and more of a classical stylist than Olympiodorus, based his history on both Herodotus and Thucydides. He went on a mission to the Hun king Attila in 449 and expressed his admiration for him in his history, while criticizing Theodosius II for his policy of trying to buy off Attila. Yet another colourful character was Cyrus of Panopolis, also in Egypt, a poet who rose to the positions of prefect of the city, praetorian prefect and consul under Theodosius II, only to be accused of paganism in court intrigues and sent into exile as bishop of the small town of Cotiaeum in Phrygia.16 Such a system perpetuated traditional attitudes, as indeed it was intended to do; not least, it imposed fixed categories of thought, and in particular impeded realistic perceptions of relations with barbarian peoples who were by definition seen as lacking in culture. In general the continuity of late antique elite education, based on rhetoric and philosophy, and directed to the classical authors, powerfully maintained and reinforced social attitudes. This was the paideia which was also essential for Christians ambitious to rise and have influence in the wider society. The only Christian alternative lay in the monastic and ascetic formation, and the tension between religion and secular education led to profound dilemmas for many, Augustine being perhaps the most conspicuous example.17 It was a type of education that depended on access to an urban environment. For Procopius, as for Justinian, the idea of civilization also went hand in hand with that of cities; new cities were founded in the reconquered territory, while others were restored, and as long as the cities survived, the apparatus of traditional elite culture – baths, education, municipal institutions – had a chance of surviving as well. Even in Ostrogothic Italy, Amalasuntha, the daughter and only child of Theodoric, and learned herself, wanted a Roman education for her son,18 and defended her choice of Theodahad for her husband (which was to prove unfortunate) to the Roman senate in terms of his education:

Figure 6.1 One of the classrooms uncovered at Komm el-Dikka, Alexandria

To these good qualities is added enviable literary learning, which confers splendour on a nature deserving praise. There the wise man finds what will make him wiser; the warrior discovers what will strengthen him with courage; the prince learns how to administer his people with equity; and there can be no station in life which is not improved by the glorious knowledge of letters.

(Cassiodorus, Var. X.3, trans. Barnish)

Many bishops had also received a high-level education in the classics, such as Augustine, Severus and Zachariah; others, such as Theodoret of Cyrrhus in northern Syria, chose to emphasize their religious upbringing and monastic connections, but clearly acquired an extensive knowledge of classical literature. Synesius in Cyrene and Sidonius Apollinaris in Gaul were both fifth-century bishops who were also accomplished authors in the classical manner. Sidonius, author of Latin panegyrics, poems and letters, came from a family with two generations of praetorian prefects and was himself city prefect of Rome in 468; other former office-holders who became bishops in the fifth and early sixth centuries were Germanus of Auxerre, and in the east Irenaeus of Tyre, Isaiah of Rhodes and Ephraem of Antioch.19 Caesarius of Arles, Avitus of Vienne, Ennodius of Pavia and later Venantius Fortunatus were others who all drew on a rhetorical training in the classics.

Acquiring such a training was a matter of social background: it was necessary to be comparatively well-to-do and, usually, male. Only a few particularly favoured women gained access to these skills, such as Eudocia, the wife of Theodosius II, who was the daughter of a sophist in Athens and herself composed both secular and Christian poetry.20 Greek verse composition was highly valued; many poets flourished in Egypt in the fifth century and were able to sell their services as panegyrists. Nonnus of Panopolis is the most important of the fifth-century poets: author both of an immensely long and elaborate hexameter poem known as the Dionysiaca and of a poetic paraphrase of St John’s Gospel, he set a pattern of poetic style and diction which others followed extremely closely, while his mythological themes provide the literary context for the mythologizing mosaics of late antique sites in Syria, Jordan and Cyprus.21

In the late sixth century, Dioscorus from Aphrodito in Upper Egypt was still writing Greek verse on traditional subjects,22 and at the court of Heraclius in the early seventh century, George of Pisidia was the author of panegyrical poems which combined classical metres and techniques with Old Testament imagery, while Sophronius, monk and patriarch of Jerusalem from 634–38, composed anacreontic verses on the capture of Jerusalem in 614 by the Persians.23 A Christian school of Greek rhetoricians and poets flourished in sixth-century Gaza, which was also home to important monastic figures and the site of a spectacular synagogue mosaic.24 A series of historians wrote classicizing histories in Greek in the fifth and sixth centuries,25 and though the approach of the ecclesiastical histories of such writers as Socrates and Sozomen in the fifth century or Evagrius Scholasticus at the end of the sixth may have been somewhat different, these too were works written from the basis of a thorough training in rhetoric. A similar training continued to be available in Latin in the west. Servius’ commentary on Virgil, Macrobius’ Saturnalia and Martianus Capella’s De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii, in nine books, belong to the first half of the fifth century,26 while the North African poet Dracontius composed lengthy hexameter poems in the Vandal period, from which we also have the collection of short Latin poems known as the Latin Anthology and the epigrams of Luxorius.27 The African Latin poet Corippus composed an eight-book hexameter poem on the Byzantine campaigns there in the 540s and later delivered a Latin panegyric in Constantinople on the accession of Justin II in 565 (Chapter 5); it seems that Virgil went on being taught in North Africa after the reconquest in traditional school contexts, at least for a while. Everyone learning to write Latin seriously learned it from Virgil: papyrus finds from the small town of Nessana in a remote spot on the present Egyptian border show that this continued in the seventh century, long after the Arab conquest.

Figure 6.2 Mosaic of the first bath of Achilles, from the House of Theseus, Paphos, western Cyprus, late fourth century

The literary production of late antiquity has been judged inferior to that of earlier more ‘classical’ periods. But it can also be seen as reflecting an age of fragmentation, when traditional literary accomplishment was fraught with uncertainty, defended with displays of virtuosity or applied to unfamiliar Christian uses. In some fields this presented itself as a new kind of poetics, observable from the fourth century onwards, with an emphasis on display and surface glitter, a style as eclectic in its way as that of contemporary architecture with its juxtapositions and its unashamed incorporation of earlier elements,28 less a late antique mentality than a late antique aesthetic, and one that can all too easily mislead.29

High Culture – Philosophy

Philosophy was vigorously practised in the fifth and sixth centuries, particularly at Athens and Alexandria, and the influence of philosophical ideas was clearly profound.30 Many elements of the Platonic philosophical tradition had been absorbed into Christian teaching and had thereby become available to a wider public in a different guise. Neoplatonist teaching in the fifth and sixth centuries, however, was also often identified with paganism. As taught in the major centres, it took a highly elitist form, and among certain sections of the upper class it still enjoyed considerable prestige; as we saw, the family of Paralius in Aphrodisias sent its sons to Alexandria, and a number of important mosaics from Paphos in Cyprus and Apamea in Syria, home of a flourishing school especially notable for the early fourth-century philosopher Iamblichus, may suggest the diffusion of Neoplatonic ideas in the fourth century.31 Athens was the particular home of Neoplatonism, the late antique version of Platonism associated in the first place with Plotinus, active in the third century, and in our period especially with Proclus, who arrived in Athens in 430 and became head of the school there at the early age of 25 or 26 in 437. He remained head of the school until his death in 485, when his Life was written by his successor Marinus.32

The Neoplatonists evolved their own system of philosophical education, in which the teachings of Aristotle and of the Stoics were harmonized with those of Plato to form an elaborately organized syllabus. The ‘Aristotelian’ philosophers of late antique Alexandria were as much Neoplatonists as the Athenians, and Simplicius, one of the last and greatest of the Athenian philosophers of this period, wrote a series of important commentaries on the works of Aristotle. But Neoplatonism was also deeply religious; indeed, it almost amounted to a religious system in itself. Neoplatonists sought to understand the nature of the divine and to evolve a scientific theology, practised asceticism (Chapter 3), contemplation and prayer, revered the gods and adopted special ways of invoking them (‘theurgy’). They believed in the possibility of divine revelation, especially through the so-called ‘Chaldaean Oracles’ (second century), which claimed to be revelations obtained by interrogation of Plato’s soul. For Proclus and his followers, Plato himself and his writings acquired the status of scripture. Naturally such teachings came to be identified with paganism, but many of the greatest Christian thinkers, such as Gregory of Nyssa and Augustine, were also deeply influenced by Neoplatonism. Certain of Plato’s works, especially the Timaeus and the Phaedrus, were influential on many Christian writers, including Augustine, and there was much common ground between Neoplatonism and Christianity.33 In Athens, Proclus headed a ‘school’ not so much in the sense of buildings or an institution (the teaching of the Academy seems still to have been conducted in a very informal way by modern standards) as in the fact that he had a group of pupils, on whom he exercised a charismatic influence and with whom he celebrated a variety of forms of pagan cult which included prayer, meditation and hymns, and even extended to healing miracles. When the father of a little girl, appropriately called Asclepigeneia, who was desperately ill, asked for Proclus’ prayers:

Taking with him the great Pericles from Lydia, a man who was himself no mean philosopher, Proclus visited the shrine of Asclepius to pray to the god on behalf of the invalid. For at that time the city still enjoyed the use of this and retained intact the temple of the Saviour [i.e., Asclepius]. And while he was praying there in the ancient manner, a sudden change was seen in the maiden and a sudden recovery occurred, for the Saviour, being a god, healed her easily.

(Life of Proclus 29, trans. Edwards)

When in 529 Justinian forbade the teaching of philosophy in Athens,34 seven Neoplatonist philosophers then active there, led by Damascius, the current head of the school, are said to have made a voyage in search of Plato’s philosopher-king to Persia, where, they had heard, the new king, Chosroes I, was interested in Greek philosophy to the point of commissioning translations of Plato (Chapter 5). When they reached the Persian court, they soon became disappointed and returned, though not before securing a safe conduct for themselves under the terms of the peace treaty of 533. The story is told by Agathias in the context of a denunciation of Chosroes and a certain Uranius who had, according to Agathias, absurdly encouraged the king’s philosophical pretensions.35 It has given rise to much discussion, both as to the fate of the Athenian Academy itself and as to that of the philosophers, in particular Simplicius, who went on to conduct a vigorous polemic against his rival, the Alexandrian John Philoponus. One theory suggests that he spent the rest of his active life and founded a Platonic school at Harran (Carrhae) in Mesopotamia, known as a home of paganism until a late date. If correct (apart from possible local references in Simplicius’ commentaries, it depends largely on a single statement in a tenth-century Arabic writer which may suggest the presence of Platonists there), this would have important consequences for the transmission of Greek philosophy into the Islamic world.36 Priscian, another of the seven, wrote a treatise setting out the answers he had given to the questions of the Persian king. Agathias tells the whole story from the point of view of Hellenic superiority, but Chosroes was indeed known in eastern sources for his erudition and curiosity, and himself composed a history of his achievements.37

It was not least the intensity of philosophical debate even in the mid-sixth century that is so notable. Nor was it confined only to philosophers themselves. Philosophical thought also extended to monastic and theological circles,38 and John Philoponus, the leading philosopher at Alexandria at that time, was himself a Christian. He wrote a long series of works in the course of which he argued against the view of Proclus that the world had had no beginning, though his own views were not fundamentalist enough for some Christians. Philoponus also espoused a particular form of Monophysitism known as Tritheism,39 but there seems to have been room for a considerable range of approaches within the philosophical circles of Alexandria. Unlike Athens, which succumbed to the Slav invasions of 582 onwards, and where, if any philosophical teaching continued, it had no chance of doing so on a scale remotely comparable with its long past tradition, Alexandria was able to preserve its philosophical tradition until the Arab conquest.

If anything, the literary culture of late antiquity was even more class-based than previously. It required a specialized training, not only from writers but also from their audiences, and by the sixth century at any rate the spoken language in Greek was diverging markedly from this high literary language.40 The traditional literary culture was still available in Constantinople under Heraclius (610–41), but as urbanism declined or cities were lost to Roman rule, a sharp decline set in; this also affected the availability of books and the knowledge of classical authors, and did not begin to be restored in the Byzantine empire until the ninth and tenth centuries. The social and cultural system which had produced and sustained this very elitist literature was in fact changing fast. One of the main changes was brought by Christianization, but Christian writers were themselves often both highly educated and extraordinarily prolific.41 Many Christian writings are extremely rhetorical in character, and use all the panoply provided by a classical education. Augustine, perhaps the greatest Christian writer of the period, had been a teacher of rhetoric himself, and did not hesitate to use his skill to the utmost when he later came to write religious works. Bishops (including Augustine) and other Christian writers combined secular learning with Christian expression, not least in the form of letters, which constituted a particularly flourishing genre among educated Christians in the early fifth century; a large number survive, testifying to a close network of shared culture and common interests stretching between Gaul, Italy, North Africa and elsewhere. But unlike most classical writers, Augustine was also supremely conscious of the techniques necessary in addressing himself to an uneducated audience, and kept returning again and again to the problems of reconciling intellectual and rhetorical aims with religious faith. His great work, the City of God, written in the aftermath of the sack of Rome by Alaric in AD 410, is less an extended meditation on the reasons for that event than an discussion of the place of the classical world and classical culture in the scheme of Christian providence.

Figure 6.3 The shape of the world as imagined in the Christian Topography of Cosmas Indicopleustes. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurentiana, MS Plut. IX.28, f. 95 v

Christianity and Popular Culture

Hagiography – the lives of saints and holy men – was a major form of writing in late antiquity, and while its literary range varied greatly, many saints’ lives were permeated with literary tropes from secular literature;42 similarly, while Christian world chronicles, running from Adam to the writer’s own day, have often been regarded as ‘credulous’, the genre began with the great Christian scholar Eusebius and the surviving examples have much in common with classicizing historiography.43 But the impact of Christianization changed reading practices, especially through the availability of the Bible. A specifically Christian learning developed, with the early monastic communities in the west, as on the island of Lérins, setting a precedent in the late fifth century for the great medieval monastic centres of learning. A large body of sayings and lives of the ‘desert fathers’ (and a few ‘mothers’) in Egypt also developed, and Palladius’ Lausiac History and Theodoret’s Historia Religiosa collected stories of holy men and women.44 A vigorous culture of translation had developed in the eastern Mediterranean by the sixth century for the circulation of saints’ lives and Christian apocryphal texts dealing with Christ’s descent into Hades and Mary’s assumption into heaven; many such texts, originally composed in Greek, survive only in translations into Syriac, Georgian, Latin or later Arabic.45 Unlike classical culture, Christianity did indeed consciously direct its appeal to all classes of society, explicitly including slaves and women. While it is true that St Paul’s famous declaration that ‘there is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female; for ye are all one in Christ Jesus’ (Gal. 3:28) did not, and was probably never meant to, lead to the abolition of social differences, nevertheless, along with such sayings as that about the difficulty of the rich man in entering the kingdom of heaven, Christianization did bring with it something of a change of attitude towards those groups who had been barely considered at all in the pagan Roman world.

The meeting of the old classical cultural and educational system with Christian ideas has often been associated with the idea of a ‘new, popular culture’, more universal in character and based less on the written word and more on the visual and the oral.46 The increase in attention to Christian religious images in the later part of our period (Chapter 9) has also been ascribed to the influence of popular culture, and indeed one does at times find references to sacred pictures as a way of educating the illiterate. Thus Nilus of Sinai (fifth century), recommended decorating a new church with pictures from the Old and New Testaments:

So that the illiterate who are unable to read the Holy Scriptures may, by gazing at the pictures, become mindful of the manly deeds of those who have genuinely served the true God and may be roused to emulate those glorious and celebrated feats.47

But Christian art and Christian writing alike were often as complex as secular, and in practice, members of the educated upper class were just as enthusiastic about icons, saints and holy men as ordinary people.48 Even secular historians from the late fifth and sixth centuries, such as Zosimus (who was actually pagan) and Procopius (certainly not a ‘popular’ writer), seem to show a greater receptiveness to miracle and other religious factors as part of historical explanation.49

Family and Personal Life

Christianization brought with it the rise of monasticism and the ascetic lifestyle (Chapter 3). Even if we take the figures given in contemporary monastic sources for monks and ascetics in Egypt with a degree of scepticism, the number of men and women in the empire as a whole who had dedicated themselves to the Christian religious life must have amounted to thousands by the fifth century, and some monasteries were very large, with refectories and accommodation for over 200 monks. The general principles of ascetic life were also shared in some pagan circles, notably among Neoplatonists, but they had no such monasteries, and belonged on the whole to elite groups in society; their numbers were therefore in comparison very limited.50 It is difficult to know how widely the ideals of monastic and ascetic life were shared in society generally, but many saints’ lives tell of families dedicating their children to the ascetic life at an early age. Even if idealized and presented within the framework of literary and religious cliché, saints’ lives also seem to signal an increase in the attention given to individuals, and early Christianity has been seen as indicative of a new emphasis in this direction. The advance of Christianization also brought changes in attitudes to the dead, though in many cases there was still little difference between Christian and pagan burials,51 and many monasteries, like that of Euthymius in the Judaean desert, incorporated the tomb of their founder and a charnel house for the monks themselves.

Social and religious change also had implications for family life: under Constantine the Augustan legislation which laid down penalties for members of the upper class who did not marry was lifted and from then on celibacy became a serious option even for the rich. Jerome’s successful efforts to promote an extreme ascetic ethos among the daughters of the Roman aristocracy in the late fourth century are well known, and caused resentment in the parts of their circle that were still pagan. The promotion of ascetic lifestyles, including the dedication of daughters to lives of virginity, destabilized existing family structures and divided loyalties.52 A common form of renunciation for this class occurred when a married couple who had produced one or two children to ensure the family inheritance, decided subsequently to abstain from sexual relations and sell their property for the benefit of the church. For Paulinus, who became bishop of Nola in Campania, and who took this step with his wife in the early fifth century, we have a good deal of detailed evidence in his own letters and other contemporary sources; but the most sensational case was undoubtedly that of the Younger Melania (so-called to distinguish her from her equally pious grandmother of the same name) and her husband Pinianus, chosen for her by her parents in an arranged marriage when she was 13. Melania and Pinianus sold their colossal estates c. AD 410, against the wishes of her father, Valerius Publicola, when she was only 20 and he 24. Melania and Pinianus had properties literally all over the Roman world; when they acquired several islands, they gave them to holy men. Likewise, they purchased monasteries of monks and virgins and gave them as a gift to those who lived there, furnishing each place with a sufficient amount of gold. They presented their numerous and expensive silk clothes at the altars of churches and monasteries. They broke up their silver, of which they had a great deal, and made altars and ecclesiastical treasures from it, and many other offerings to God.53 According to her biographer, Melania made it clear that she did not wish to marry or have sexual relations, but had been forced to give way and had given birth to two children; when both died in infancy, her ascetic wishes finally prevailed. She owned estates in Spain, Africa, Mauretania, Britain, Numidia, Aquitaine and Gaul, several of them having hundreds of slaves, and her estate near Thagaste in North Africa is said to have been bigger than the town itself. Clearly the literal adoption of asceticism at the top ranks of society caused a sharp break with existing social practice, and a considerable disruption of family and inheritance. How far individual renunciation really redistributed wealth towards the poorer classes is less easy to judge (Chapter 3). Yet the development of Christian almsgiving and social welfare is also one of the major features of the period, and it took the form not merely of alms distribution, but also of the building and maintenance of charitable establishments such as hospitals and old people’s homes. Christian charity, which in some senses replaced classical euergetism (civic endowments) – though the latter still continued in some cases – had very different objects and mechanisms.

Changes in family life and sexual practice are among the hardest things to judge with any accuracy. In the ancient world, from which we mostly lack personal sources such as private letters or diaries,54 quite apart from any kind of statistics, the problem is doubly difficult. The goings-on in Merovingian royal circles, recorded, for example, by Gregory of Tours, make it clear that Christianity made little difference to the morals of that court at least, except perhaps when a bold bishop dared to intervene. As for society in general, it is hard to know how much difference the general approval given to asceticism made in the sexual lives of the majority. While many sermons exhorted Christians to sexual continence, it would be natural to assume that there was in practice a gap between what was claimed by the preacher and the real situation. It would be equally dangerous, however, to conclude that they had no effect at all, and the large number of surviving saints’ lives makes plain the extent to which such attitudes were presented as an ideal.55 This does not mean of course that existing sexual practice changed dramatically in all, or even in many, cases. Only inscriptions can give much statistical information about family size in the ancient world (and even these are deceptive, for we rarely have a large enough statistical sample). On this basis a recent study concludes that there was no real difference between pagan and Christian families. It is interesting to find that among the better-off classes, which were able to afford funerary monuments, a family size comparable with the modern nuclear family seems to have been the norm. The church condemned contraception with a vehemence that suggests that it was seen as widely practised, but there were other means of limitation of family size, including the sale of infants and infanticide by exposure, a long-established practice in the ancient world.56

It would be a mistake to romanticize marriage or family life in the late empire – for most people, it remained both brutal and fundamentally asymmetrical, as can be seen from Augustine’s discussion of the role of the father in the City of God, where what is emphasized above all is the power relation in which he stood towards the rest of the household, starting with his wife;57 he also wrote a treatise ‘On the good of marriage’ and had had a longstanding concubine himself and the prospect of a marriage arranged by his mother.58 In some Latin works of the fifth and sixth centuries, we do find more attention, even if somewhat equivocal, being paid to the role of Christian wives and mothers.59 But life expectancy remained short, especially for women of child-bearing age, and infant mortality was high, while the methods available for limitation of families (not necessarily with the consent of the mother) were crude and painful. As for children, they are often the forgotten people in ancient sources, and it is not much easier to find evidence about their lives than it is in earlier periods.60 This does not mean that individuals did not care about the children, but it does mean that children themselves were still given a low priority in the written record, a fact significant in itself. The Gospel sayings about children (see Matt. 19:14) lagged far behind those about rich and poor in their actual social effect.

Yet even on a minimalist view, the drain of individuals and resources from family control to the church in its various forms clearly did have a profound effect on society. Even if in an individual case a family did not send one of its members to the monastic life or change its sexual habits sufficiently sharply to reduce the level of procreation, it probably did, if it was rich enough, make gifts to the local church, and these themselves could be on a lavish scale. Perhaps more important than the practical results of these ideas in individual cases was the degree of moral and social control which the church now claimed over individual lives, and which can be seen, for example, in restrictions on marriage within permitted degrees.61 Justinian legislated on matters such as divorce and the legal position of women in ways that offered a greater degree of protection (see below), but while Christianization may not have changed the hearts of individuals as much as has often been thought, there were important ways in which it did claim to control the outward pattern of their lives.

Women and Men

Christianity did, however, have the effect of bringing women into the public sphere.62 Rich women, at any rate, could now travel to the Holy Land, found monasteries, learn Hebrew, choose not to marry or to become celibate, dedicate themselves to the religious life and form friendships with men outside their own family circle, all things which would scarcely have been possible before. In contrast, we might remember, nearly all Christian slaves and coloni remain among the great mass of unknown ancient people, whom nobody wrote about. When the alternative was probably a life of drudgery or boredom, asceticism offered at least the illusion of personal choice. Women were also seen in Christian writing as the repository of sexual temptation, and much of the theological literature of the period has a distinctly misogynistic tone, but at least no attempt was made to deny women’s equal access to holiness, and, in some circles, close male–female friendships became possible in ways only paralleled in a few recherché Neoplatonist circles.63 It is a notable feature of late antique Christian literature that it began to give attention to women in a way that would have been hard to imagine in the classical past. Like the poor, women became a subject of attention. Inevitably, we know most about upper-class Christian ladies such as Melania the Younger, Jerome’s friend Paula and her daughters, or the deaconess Olympias, the friend of John Chrysostom. In view of Jerome’s awkward temperament, it is touching to see that Paula, Fabiola and Eustochium were buried alongside him at Bethlehem, for it had been foretold that

the lady Paula, who looks after him, will die first and be set free at last from his meanness. [For] because of him no holy person will live in those parts. His bad temper would drive out even his own brother.64

Women such as these were of course not typical; for most, it was not a matter of real change in lifestyle, and the range of possibilities was still defined in an extremely narrow way. Against the apparent broadening of opportunities ran the fact that precisely during this period the Virgin Mary emerged as a major figure of cult and worship. Much of the direct reason may have been christological, connected with the doctrinal issues debated at the councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon (Chapters 1 and 3), though attention to Mary had been building up since the late fourth century, but the emergence of her cult also carried powerful symbolic messages for women: whereas Eve represented woman’s sinfulness and potential to corrupt, Mary stood for her purity, demonstrated by virginity and total obedience.65 This development in the cult of the Virgin, especially around the time of the Council of Ephesus (431),66 was preceded by an increasingly strident advocacy of virginity by many of the late fourth-century Fathers; this, too, while not confined to women, tended to be presented in terms of the woman’s traditional image as seductress. Since, as in most societies before and since, men still represented rationality, while women were defined in terms of their sexual identity, it is hardly surprising if the price of a degree of freedom for women was the denial of their sexuality. The highly popular fictional accounts of female saints such as Mary of Egypt, often former prostitutes, who concealed their sex altogether and dressed as men, usually to be revealed as female only on their deathbeds, demonstrate in extreme form the complexities and contradictions of Christian gender attitudes.67

Close study of the large amount of legislation on marriage and other matters affecting women from Constantine to Justin II (565–78) reveals both continuities and changes. Women are still seen as essentially dependent and in need of protection, their status is strictly subordinate to that of their husbands and their legal access is limited. The great bulk of Roman law affecting individuals was little changed by Christianization, and indeed much of it was re-enacted by the Christian emperors. But new legislation also concerned itself with the protection of public morality, and especially with the protection of chastity; it became much more difficult for a woman to initiate divorce, and obstacles were put in the way of remarriage; from Constantine onwards a succession of laws penalized women far more strictly than men for initiating unjustified divorce proceedings, until in 548 Justinian equalized the penalties. Even under the Christian emperors, however, marriage itself remained a civil and not a religious affair. On the other hand, the rights and obligations of mothers over their children were considerably strengthened, especially by Justinian, to whom the largest body of relevant legislation belongs, and all of whose innovations were actually in the direction of improving the legal position of women.68 The real role of Christianization in bringing about such change is, however, far from clear; the law was changing during this period, certainly, but the motivation for those changes is another matter. Perhaps the most striking feature remains simply the amount of attention given in imperial legislation to matters concerning women; this is important enough in itself.

Thus the ways in which women could enter the public sphere, though they existed for a few, were still limited. The pagan intellectuals Hypatia and Athenaïs, the latter the daughter of an Athenian philosopher who became empress (as Eudocia) after she had been taken up by the Emperor Theodosius’ pious sister Pulcheria (Chapter 1), were equally or even more exceptional. On the other hand, within the religious sphere, on a family basis or in the religious life, some women may have gained more status than they had had before. At least we can say that Christianization brought with it distinct changes in consciousness and new possibilities for individual and group identity. In some ways the constraints on women, which were great, actually intensified, but even within the constraints of contemporary moral and religious teaching, the inner self was not exclusively defined as male. But it was not only women whose lives and consciousness was affected by Christianization. Men too faced adjustments and were presented with dilemmas and opportunities. As we have seen, many adapted enthusiastically, but others, especially elite men of the Roman senatorial class, found more difficulty.69 Late antiquity was also a time when eunuchs became established at court and in the higher administration, a feature began early and persisted into the Byzantine period. There were eunuch generals, such as Narses and Solomon in the sixth century, and later even eunuch patriarchs. They were found useful by emperors as a ‘third sex’, and some families saw prospects of advancement in castrating their sons. Some rose high and became very powerful, as in the early fifth century, but they were also suspected and at times feared, and gave rise to a persistent strain of disapproval and distaste.70

Material Culture

Culture is not of course solely about mentalities and intellectual life. Material objects and material culture are part of what we mean by the overall term, and the incorporation of the study of material culture (including, but not limited to, art history) is a feature of the recent historiography on late antiquity.71 Weights, lamps, textiles, pottery are all types of object that appear alongside luxury items in exhibitions, museum displays and illustrated books, and which feature in discussions of ‘daily’ or ‘everyday’ life. Wanting to avoid the associations of an emphasis on spirituality or on theological issues, some art historians also cast their subject in terms of material culture.72 In this regard several issues present themselves during our period. They include the question already mentioned of how far ethnicity can be deduced from assemblages of archaeological material, and the related issue of what material culture can tell us about religious sensibility. In our period, material culture also changed alongside social changes, and as Christianity developed the cults of relics and religious images. Material culture also became highly contentious as these practices were questioned, both by Christians themselves and under the impact of Islam (Chapter 9). What the impact was on individuals of the material culture which they experienced is a question that is being addressed for other periods but which still needs to be asked about late antiquity and Byzantium.73

In many ways this was a tumultuous period, when many existing social barriers were weakened, if not actually broken, and others formed. One of the most marked features of the period is clearly the progress of Christianization, which involved social change and the development of an authoritarian ideology.74 But the fragmentation of Roman society in the west, the advent of barbarian settlement and the subsequent development of barbarian kingdoms also disturbed existing norms, though whether they brought any greater freedom is a different matter. In the eastern empire the sixth century, and especially the reign of Justinian, marked an apogee in the history of early Byzantium, with a strong emperor, powerful ministers and centralized government. At the same time, however, urban violence reached unprecedented levels (see Chapter 7), and there was much questioning of the relations of centre and periphery. The ambitious policies of Justinian brought the empire, and Justinian’s successors, into difficulties which are clearly perceptible in their relations with the strong neighbouring power of Sasanian Persia in the late sixth century. Justinian was a codifier of the law and a legislator of unparalleled energy. But he did not succeed in achieving long-term security or internal harmony for the empire. The end of the sixth century brought the Persian occupation of the Byzantine Near East and renewed war with Persia on a major scale, followed immediately by the Arab conquests which seriously threatened Constantinople itself and led to the loss of huge amounts of territory. The urban structures of late antiquity, on which its educational system depended, underwent fundamental change. This is the subject of the next chapter, while Chapters 8 and 9 focus on the east, its prosperity in the sixth century and later, its religious ferment and the momentous events it experienced during the seventh century.