UNDERLYING SKILLS

“One’s ultimate success depends on one’s own meticulous self-analysis . . .

—Desmond T. Burke

The ultimate skill that we all want to acquire is the ability to “read the wind,” but this is made up of several individual skills, such as observation and memorization. We believe that each individual skill can be learned and practiced, both on and off the range.

Off the range, you can easily practice paying attention to the wind, describing its pattern, assessing its value, and estimating your sight settings . . . take your wind meter with you when you take the dog for a walk or go shopping.

On the range, one of the best ways to get good as a wind reader is to spend time as a wind coach. We use the classic team setup to train our students in wind reading.

• The shooter’s job is simply to fire a perfect shot.

• The plotter’s job is to keep the group centered and, by keeping a record of shot fall, to assist in identifying wind conditions.

• The wind coach’s job is to focus completely on the process of reading the wind and determining the correct sight setting for each condition.

In Figure 62, you can see the team setup we used during our competition rifle course in Florida in 2003, which was hosted by the Bermuda Rifle Team.

• As a wind coach, you never have to take your eyes off the wind; this will improve your observation skills.

• If the wind changes during shot execution, you will see it. This will improve the accuracy of the feedback you are getting while you are building your sense of cause and effect, and in the long run will improve your ability to identify critical factors and analyze shot placement.

Figure 62. Plotter, wind coach, shooter.

• Many wind coaches have told us that by practicing in this way, their decision-making skills improve. They think it’s because they are forced to separate the wind call from shot execution. They don’t hedge their bets, riding on one side of the bull or the other; they always try to make a fully centered call. Because making the wind call is their only job, they do it better. The effect is carried over into their own shooting.

• Your confidence (and your ability to take risks) will improve as you develop your skill. If you have the opportunity to be part of a large team-coaching situation, where you are “wired for sound,” do it! In this type of situation, the coaches are joined together by intercom, along with a central (lead) coach, to talk together about the wind calls they are making. This is a particularly good way to learn from other people’s wind calls and probably the only opportunity you will have to compare your wind reading with that of others.

We believe that improving your ability to perform these underlying skills will improve your ability to read the wind. One of Canada’s top shooters (and one of the top shooters in the world) is Alain Marion. He acknowledges that he has very good eyesight. This undoubtedly helps him in delivering an excellent shot, because he is very sure of his sight picture. But we believe that it also helps him observe the indicators that will contribute to his wind decision. His superior eyesight has made him more sensitive to these indicators than someone who sees the world less clearly. Now, you can’t practice to get better eyesight, but you sure can practice to put more attention into observing the details of the indicators!

IDENTIFYING THE CRITICAL FACTORS

More than any other skill, this is perhaps the one that separates the champions from the rest. It is the ability to identify and focus on the critical factors, and to dismiss and ignore the noncritical ones.

Some time ago, we wrote an article for Tactical Shooter magazine entitled “How Good Shooters Think,” based on research conducted by Edward F. Etzel Jr. as a part of his master of science in physical education at West Virginia University. His findings were published in the Journal of Sport Psychology (1979) under the title “Validation of a Conceptual Model Characterizing Attention among International Rifle Shooters.”

Etzel identified the following skills and tested rifle shooters to measure which skills were most important:

1. Duration, the ability to think/concentrate for an extended period

2. Capacity, the ability to think about complex things

3. Flexibility, the ability to change the focus or topic of thought easily

4. Intensity, the ability to be alert and focus intently on a subject

5. Selectivity, the ability to focus on only the few things that are directly relevant to the task at hand

What Etzel found was that, of all the attention skills that he tested, by far the most important was selectivity, “the ability to discriminately perceive relevant information, as well as the ability to screen out irrelevant information.” Research has generally indicated that human beings are extremely limited in this ability. Since selectivity is a rare skill and it is the most important skill identified in Etzel’s study, it is possibly the defining skill for champion shooters.1

The purpose of identifying the critical factors is to make your analysis as simple and as accurate as possible. This brings out the principle of “keep it simple.” During competition, it is essential that you identify the smallest number of things that you need to pay attention to so that you can focus your attention on the right things.

One of the ways you can train to identify critical factors is to watch other people shoot. For example, if you see a flag movement (e.g., the safety flag at the butts) that results in shots being blown off, you may have found a critical factor.

Another way to identify critical factors is to talk to people who know the range to find out which of the indicators they believe are the most critical to watch.

A third way is to do a postmortem analysis of your match (preferably with your coach) to identify which factors you used and which you missed and need to use next time.

OBSERVATION SKILLS

“The marksman must develop an accurate mental picture of the wind indicators and the ability to remember it from shot to shot.”2

The purpose of training observation skills is purely to improve your ability to see the details of the wind indicators. At this point, you don’t care about the wind value in minutes or your sight settings; you are simply training to observe the initial condition accurately and to see the changes.

If you are a visually oriented person, you may be able to take a mental “snapshot” of, for example, a flag’s position and perhaps record your observation with a little drawing. However, if you are a verbally oriented person, you may need to record a verbal memory, such as “the tip of the flag is an apparent finger width above the tree line.” The point is that you must find your own way to ensure that you have fully appreciated the indicator.

In some cases, you need to find ways to make the indicator more vivid to your brain, so you focus on what sets it apart from the rest of the scenery. In other cases, you need to focus your attitude: when you see a flag change from 12 to 1 o’clock, it should scream at you the way a red traffic light hollers “stop!”

If you’re interested in observation as a human skill, search the Internet under “visual perception” or “psychology cognition”; there’s a lot of ongoing research in this field, attempting to figure out how we humans acquire, process, and act on visual stimuli.

Observing Flags

To fully observe a flag or other wind indicator, you need to see, recognize, and appreciate the details of the flag.

• Observe the tip of the flag as it relates to the flagpole or a reference point such as a distant horizon—this gives you a detailed reference from which to note changes.

• Notice the centerline of the flag, and the angle it makes to the flagpole—as the wind speed increases, so does the angle.

• Appreciate the number of ripples in the main body of the flag, as well as in the tip—even after the flag angle is 90 degrees from the pole, the flag will continue to flatten out (ripples become smaller, and there are more of them) as the wind speed increases. Along the same lines, look at the softness or stiffness of the flag—more wind makes the flag stiffen. See how the base end of the flag arches away from the pole, straining against its mounting rope—when the flag is showing maximum wind speed, you can see subtle differences in the way the flag strains against its mooring.

• If the flag is near you, you can sometimes hear the flap of the cloth in the wind—the louder it flaps, the stronger the wind.

To train your flag observation skills, start by taking every opportunity to be on the range where you can see wind flags. Bring your wind meter and your notepad with you. Observe the flags, seeing all the details mentioned above, and relate them to the speed indicated by the wind meter. Practice deciding what speed each flag represents. If you feel a wind change, or if your wind meter detects one, notice and record the change in the flags. The purpose of this exercise is to improve your ability to see and recognize the subtle changes in the flags when wind conditions change.

Take pictures of flags that represent various wind speeds and wind directions. Compare the pictures to the flag diagrams you use. Practice observing the details of the flags and categorizing the wind they represent.

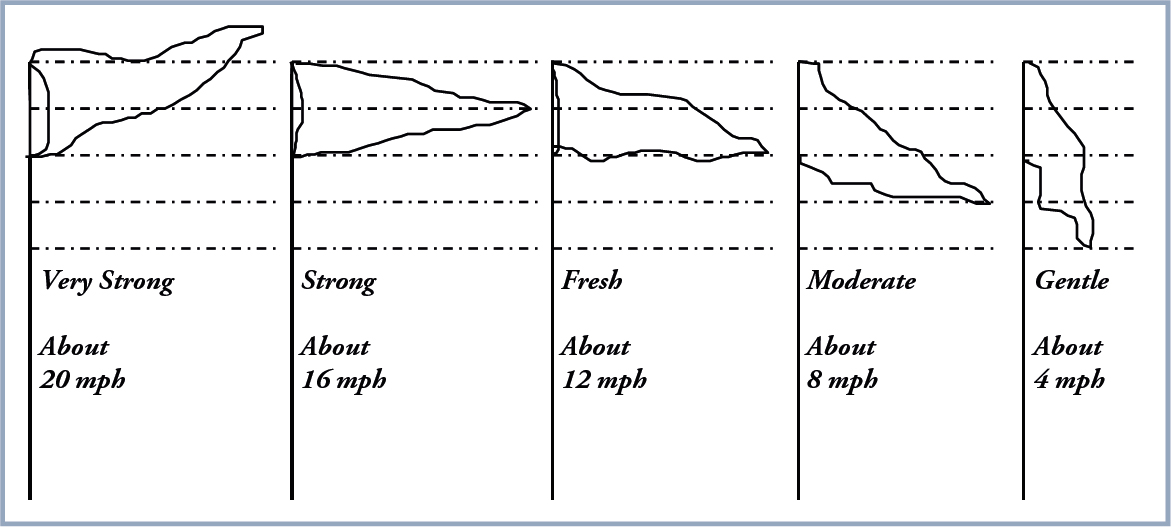

Figure 63a. Observing flags—diagrams.

Figure 63b. Observing flags—pictures.

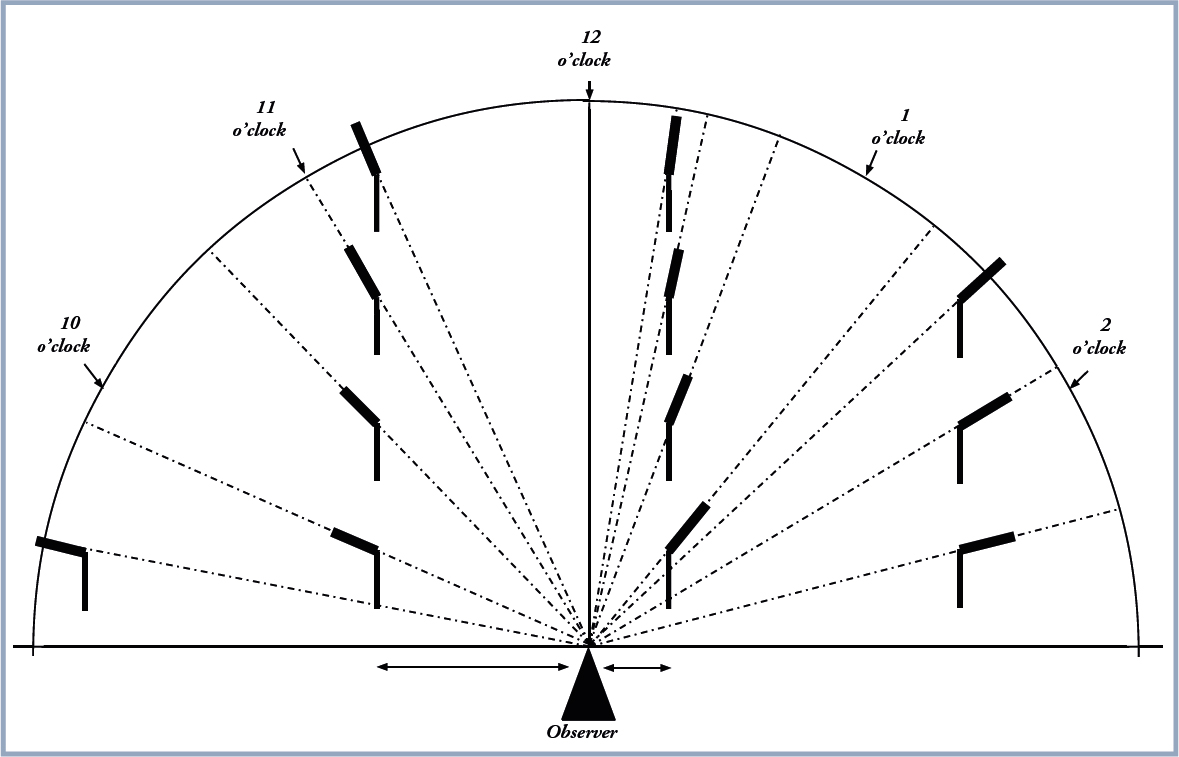

In addition to noting the flags you are using for wind speed, you need also to notice the flag that you are using for wind direction. You can sharpen your observations by drawing a little sketch of the range and its flags, and then calculating the angles of the flags that you might use for direction. Recall that your wind direction flag is one that is blowing straight away or straight toward you.

Figure 64. Range diagram.

In the range diagram (Figure 64), you can see that the flags that are nearer to 12 o’clock will give you directional readings that are closer to 12 o’clock. Notice also that a row of flags that is very near your line of sight gives you a steeper angle than flags that are farther to your left or right.

To train your angle observation skills, pick a flag that is flying straight away from you and watch it for a while. Note which side of the pole the flag moves toward and then notice the details of how much of the flag is showing on that side—the more of the flag that is showing, the greater the direction change. (See Figure 65.) Use your range diagram to estimate the angle toward which the flag has moved.

Observing Mirage

It seems that almost everyone experiences mirage a little differently. Most people cannot describe what they see in any detail. Usually, if you ask for a description, you get something like, “It’s the heat waves. You know, the air moving.” Actually, that’s pretty much what it is!

The mirage that we shooters refer to is the same kind of mirage that produces images of distant ships floating over the water. It is created by the same type of light refraction, caused by light traveling through layers of air that are at different temperatures. The interesting thing is that the mirage we watch is a mirage of the air itself. And because wind is air in motion, we “see” the wind in the mirage.

Figure 65. Observing flag direction changes.

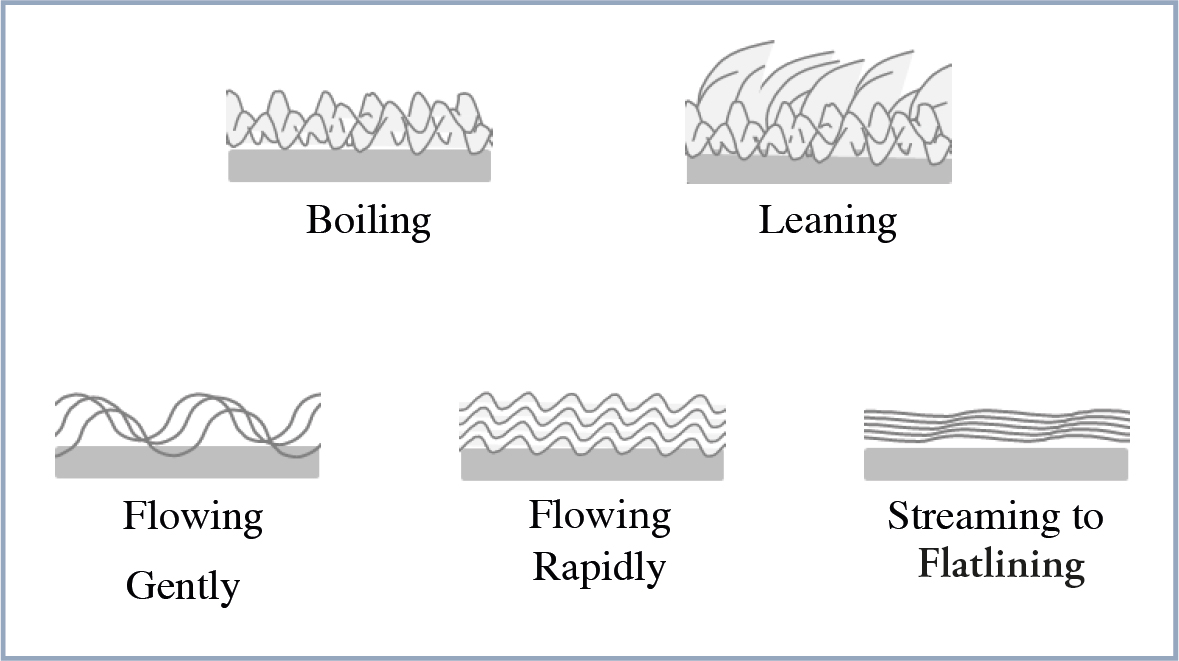

As we mentioned in chapter 1, most people describe five basic mirage formations:

1. Boiling: 0 to 1 mph

2. Leaning: 1 to 3 mph

3. Flowing gently: 4 to 7 mph

4. Flowing rapidly: 8 to 11 mph

5. Streaming to flatlining: 12 mph and more (but not much more)

Sophisticated mirage readers report they are able to distinguish several stages between “flowing gently” and “flowing rapidly,” which gives them more detailed wind estimates. Others, and some very good shooters among them, say that they can discern only three stages: “boiling,” “flowing gently,” and “flatlining.” Several of the people we consulted in preparing this book indicated that their best use of mirage is only to assess direction, and especially early warning for direction changes in light winds—only because, for them, it is hard to see changes in the faster mirage. (See Figure 66.)

As with learning to observe the details of the flags, the shooter needs to take every opportunity to set up his spotting scope and watch mirage—you don’t need to be at a range to do this—any open field, yard, or parking lot where you can see mirage will do. As with the flags, find the primary condition and recognize its detailed characteristics. For many people, the way to really see mirage is to attempt to draw the mirage, noting the amplitude and frequency of the waves. When your wind meter tells you that the wind has increased, notice how the amplitude and frequency of the waves have changed.

Try to find a way of describing the mirage that makes sense to you. If you are a fly fisherman, perhaps descriptions that you’d use to describe a trout stream would be helpful. Or, as one shooter who is familiar with syrups told us he describes the mirage in terms of the heaviness of syrup. We have also heard shooters describe mirage in terms of the number of “bumps” in the waves across the top of the target frame.

Figure 66. Observing mirage.

One thing we cannot overemphasize: the scope you use to view mirage is very important. It’s no accident that the national teams from many countries use enormous astronomical telescopes. To see mirage as soon as it is present is a competitive advantage, and to see its details clearly is equally important.

RECORDING AND RECORD KEEPING

Good record keeping and administrative procedures are required to ensure that you are working with facts. If you have moved your sight and not recorded it on your plot, or if you incorrectly mark the shot position on your target replica, you will not be able to analyze the situation properly. Even the accuracy of your target replica for your particular rifle system (sight radius and rear sight movement being the keys) is part of the overall accuracy of the information you will be using to analyze shot placement.

We have seen otherwise careful shooters plot their shots ¼ to ½ minute out of position.

There is a strong tendency to plot a shot near a scoring ring, either just outside or just inside the ring. One way to counteract this tendency is to look at the shot indicator in terms of how it lines up with the edges of two scoring rings.

And yes, these small errors can make a big difference. If you don’t remember, take another look at the diagrams that show “grouping high in the bull” (Figure 54) and “grouping slightly high and slightly left” (Figure 55). Small plotting errors can produce the same effect as a poorly centered group—only you won’t necessarily be able to see it.

A final check of your accuracy is this: when you finish the match, record the settings on your sight and check reality against the record you kept. If you finish within ¼ minute on vernier sights, you are doing well. On telescopic sights with easy-to-read scales, we expect an exact match.

MEMORIZING

The purpose of memorizing the condition is to enable you to compare one condition to the next when conditions are changing and to recognize when a condition returns.

This is where recognizing the primary condition really comes into play. It is simpler to be looking for one or two specific conditions—and recognize all the rest as exceptions or variants of the known conditions—rather than to try to keep an image of all possible conditions.

To improve your recall and your ability to recognize patterns, you can make a record of the conditions by drawing little diagrams or making notes using word pictures. Our preference is to have templates (like the flag diagrams shown in Figure 63a) that we can match to conditions. We find it easier, for example, to say that a given flag looks like the “fresh” flag (its tip level with the base of the hoist) than to try to estimate the angle of the flag from the pole (“looks like 57 degrees”).

There are some basic indicators and conditions you should master first:

• The five flag velocities

∘ Gentle

∘ Moderate

∘ Fresh

∘ Strong

∘ Very strong

• The four flag directions

∘ 12 o’clock

∘ 1 o’clock

∘ 2 o’clock

∘ 3 o’clock

• The five mirage patterns

∘ Boiling

∘ Flowing gently

∘ Flowing rapidly

∘ Streaming or flatlining

Once you’ve mastered the basics, you can start working toward increasing the level of detail. There are three techniques that will help your ability to memorize:

• Identify patterns.

• Match conditions to known patterns.

• Look for exceptions.

When you are first learning to read the wind, strive to identify, memorize, and recognize a single condition. Then learn one more and add it to your repertoire. Focus on what you do know, apply it, and learn more. Gradually you will build your own personal database of experience, and gradually you will move from novice to master.

As Reynolds and Fulton wrote in Target Rifle Shooting, the shooter must use his own judgment based on visual cues about what the wind is really doing. There is no instrument that he can use to measure what the wind is doing to the bullet as it travels along its trajectory. There is no easy way to learn how to read the wind; there is no substitute for experience. Top shooters are often able to assess the wind conditions and make judgments with remarkable accuracy. “The best that a beginner can expect to do is to learn and memorize the known effect of certain defined wind forces, and make a reasonable guess at the prevailing wind’s strength and direction.”3

ANALYZING SHOT PLACEMENT

The purpose of analyzing shot placement is to ensure that you understand why the shot landed where it did so that you can correct the right factor. When a shot does not go where you expected it to, any of the following factors can be the cause:

• Technical capability of your rifle and ammunition

• Your ability to fire a perfect shot

• Your ability to “call” a less-than-perfect shot

• Your ability to center the group

• Your sight setting

• The effect of the wind

You need to understand the technical capability of your equipment to appreciate its grouping capability—shots that are within the grouping capability cannot be assessed for wind effects. If you can consistently fire a perfect shot (within the technical capability of your equipment), you will vastly improve your ability to establish the effect of wind versus the effect of your shooting ability.

Whenever your shot is less than perfect, you need to be able to “call your shot” (i.e., recognize an error in the sight picture at the moment the shot is fired and anticipate where the shot will land) so that you can discount the error in the sight picture (including canting errors) before you attempt to calculate any wind effect. In addition to understanding the grouping capability of your system (you, your rifle, and your ammunition), you need to have the group as perfectly centered as possible.

And, finally, you need to be sure of your sight setting (including your wind zero) before you can start to analyze the effect of the wind on your shot placement. Correcting most of these is beyond the scope of this book, yet they are prerequisites to being able to effectively call the wind.

DECISION MAKING

The purpose of the decision-making skill is to be able to produce a correct outcome, using a defensible (and repeatable) method.

Often, the shooter will get lulled into an “easy shoot” and stop making decisions altogether! Or sometimes a bit of panic or wishful thinking will make the shooter leap to a conclusion without using a clear decision-making process. And, in hard conditions, sometimes the shooter will come to the right conclusion (e.g., a 6-minute sight correction) but lack the confidence in his decision-making process to follow through and make the change on his sights.

The best way to make sure that you are always making good decisions is always to follow a solid decision-making process. The following thought process (detailed in chapter 2) is a good place to start:

• Is the wind the same or different?

• Has the wind increased in value or decreased?

• Is the change a little or a lot?

Your ability to observe and memorize will bear strongly on the quality of the information you bring to the decision-making process. And if you follow the same thought process each time, you will improve your chances of making the correct wind call.

FOLLOWING YOUR HUNCHES

There is “an intuitive sixth sense that a shooter develops with experience wherein he consciously or unconsciously recalls similar experiences and just ‘knows’ [what he needs to do].”4 Learning to trust your intuition can be a challenge, especially for those of us who are naturally analytical and live life very consciously.

We all have a sixth sense that has at times caused us to make a decision just because it felt right. Reading the wind is a complex skill that involves all parts of the brain, including the most mysterious parts. Your body can know something that you cannot articulate. You make a good decision that you cannot explain. We sometimes call this following a hunch.

Following a hunch is not the same as sloppy thinking. Sloppy thinking means accepting an inferior set of facts or an inferior decision process. Following a hunch is based on good data and good process, plus something more that you can’t define right at the moment.

Following your hunches won’t make you right all the time, but the more you practice it, the better you will get. Hunches that are based on both conscious and subconscious facts can give you better decisions than either one alone.

“If you see some apparently variable factor arise . . . the chances are that any intelligent attempt to make allowances for those changed circumstances will probably be better for your results than doing nothing at all . . . if you see/feel/ sense/suspect the wind has changed enough to take you out, the worst thing you can do is to ignore your gut feelings. Better by far for your next bullet’s chances to do something, pretty much anything, by way of a sensible adjustment in the right direction.”5

COURAGE, RISK TAKING, AND CONFIDENCE

Perhaps the best way to describe courage is the feeling that you get when you make your first 5-minute sight change and go from “bull” to “bull.” Many points have been lost because shooters were caught in a comfort zone, and while they may have seen changes that were outside that comfort zone, they could not force themselves to leave it and make a bigger sight correction. Sometimes a shooter who is uncertain about making a change will make half of the correction or will make a correction that is inside the group showing on his graph or Plot-o-Matic (EZ-Graf), even though the wind is clearly showing a new and stronger condition. We are not talking about tactics here—we are talking about having the courage of your convictions!

The following are a few ways to develop your courage and confidence:

• Armchair analysis after your shoot. As you debrief your match with your coach, identify all the opportunities you had to make a more aggressive wind call and assess what difference that might have made.

• “Attaboys” for overcorrection versus undercorrection— since the vast majority of our incorrect wind calls are undercalls, reward yourself for having the courage to make the perfect call and reward yourself for the next best situation, the overcalled shot.

• Pretend it’s your first sighter. When faced with a major change, especially one outside your bookends, pretend that you are making your first sighter and focus on all the factors you would use to decide your sight setting at the beginning of the match—and then have the courage to listen to yourself.

• Pretend it’s a practice. Too often, we focus on “not losing points” instead of learning how to make center shots, especially since many of us rarely get a genuine practice opportunity. Sometimes we need to keep the importance of winning a given match in perspective and favor our learning opportunity by taking a risk that we otherwise would not.

And on that last point, remember the quotation from Des Burke, when he shot a 49 by having the courage to leave his sights alone in hard conditions? Well, here’s the entire passage:

I recall a blustery wind varying from 16 to 20 minutes at 900 yards . . . The wind was fluctuating so rapidly that I did not feel capable of coping with it . . . I therefore corrected from my sighters and during the score made no wind changes and totally ignored the indicators and finished with 49! The fact that it was a practice probably made such a course easier to follow.6

SUMMARY

Of all the skills we have discussed, most experienced shooters would emphasize the importance of these two:

• Observation

• Memorization

The ability to observe the details of the conditions in the flags and mirage and any other indicators is a fundamental requirement for learning to read the wind. This really is a matter of practice: the more often you observe in an attentive way, the more sensitive you will become to details.

The ability to memorize and recall your observations is the next most critical skill that a shooter can develop. Certainly this is more challenging to some people than to others, but all of us can work on memory skills simply by exercising them.