Map: Madrid’s Historic Core Walk

Map: Madrid’s Museum Neighborhood

Map: Madrid Shopping & Nightlife

Map: Madrid Center Restaurants

Today’s Madrid is upbeat and vibrant. You’ll feel it. Look around—just about everyone has a twinkle in their eyes.

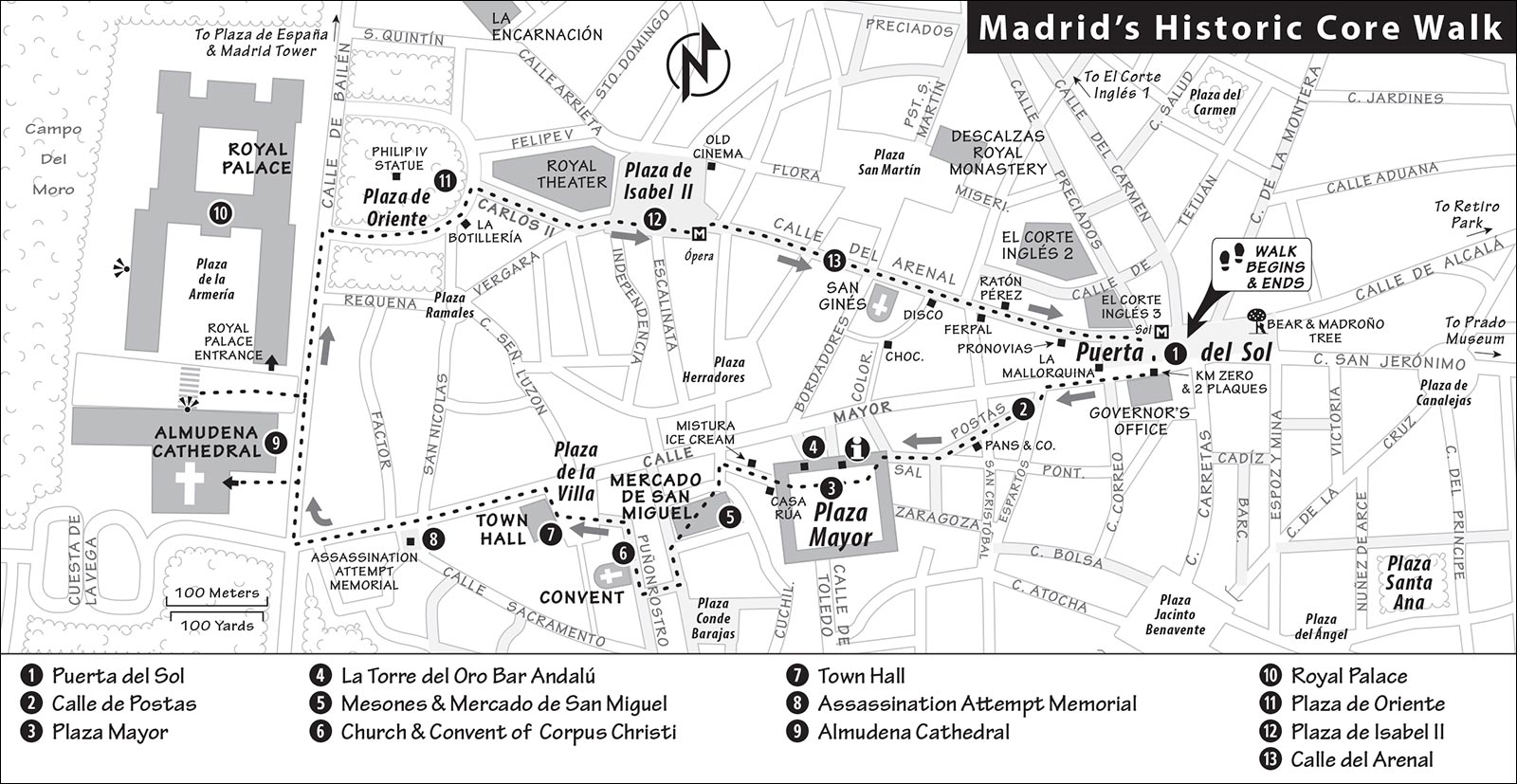

Madrid is the hub of Spain. This modern capital—Europe’s second-highest, at more than 2,000 feet above sea level—is home to more than 3 million people, with about 6 million living in greater Madrid.

Like its population, the city is relatively young. In medieval times, it was just another village, wedged between the powerful kingdoms of Castile and Aragon. When newlyweds Ferdinand and Isabel united those kingdoms in 1469, Madrid—sitting at the center of Spain—became the focal point of a budding nation. By 1561, Spain ruled the world’s most powerful empire, and King Philip II moved his capital from cramped, medieval Toledo (and the influence of its powerful bishop) to spacious Madrid.

Successive kings transformed the city into a European capital. By 1900, Madrid had 575,000 people, concentrated within a small area. In the mid-20th century, the city exploded with migrants from the countryside, creating modern sprawl. Today Madrid is working hard to make itself more livable. Massive urban-improvement projects—pedestrianized streets, new parks, extended commuter lines, and renovated Metro stations—are transforming the city. Once-dodgy neighborhoods are turning trendy, and the traffic chaos is subsiding. Madrid feels orderly and welcoming.

Fortunately for tourists, the historic core survives intact and is easy to navigate. Dive headlong into the grandeur and intimate charm of Madrid. Feel the vibe in Puerta del Sol, the pulsing heart of modern Madrid and of Spain itself. The lavish Royal Palace, with its gilded rooms and frescoed ceilings, rivals Versailles. The Prado has Europe’s top collection of paintings, and nearby hangs Picasso’s chilling masterpiece, Guernica. Retiro Park invites you to take a shady siesta and hopscotch through a mosaic of lovers, families, skateboarders, pets walking their masters, and expert bench-sitters. On Sundays, cheer for the bull at a bullfight or bargain like mad at a megasize flea market. Swelter through the hot, hot summers or bundle up for the cold winters. Save some energy for after dark, when Madrileños pack the streets for an evening paseo and tapeo (tapas crawl) that can continue past midnight. Lively Madrid has enough street-singing, bar-hopping, and people-watching vitality to give any visitor a boost of youth.

Madrid is worth two days and three nights on even the fastest trip. Divide your time among the city’s top three attractions: the Royal Palace (worth two hours), the Prado Museum (worth a half-day or more), and the contemporary bar-hopping scene.

Here’s a two-day plan that hits Madrid’s highlights. If the weather’s iffy on Day 1, you can reverse this plan. With more time, Madrid has several days’ worth of other museums to choose from (archaeology, city history, tapestries, the cultures of the Americas, clothing, local artists, and so on). Or, for good day-trip possibilities, see the Northwest of Madrid and Toledo chapters.

Morning: Get your bearings with my self-guided city walk, which loops from Puerta del Sol to the Royal Palace and back—with a tour through the Royal Palace in the middle.

Afternoon: Your afternoon is free for other sights, shopping, or exploring—consider my self-guided walk of the glitzy Gran Vía or self-guided bus tours of the busy Paseo de la Castellana or the funky Lavapiés district. Be out at the golden hour—just before sunset—for the evening paseo, when beautifully lit people fill Madrid.

Evening: End your day with a progressive tapas dinner at a series of characteristic bars.

Morning: Take a brisk good-morning-Madrid walk along Calle de las Huertas to the Prado, where you’ll enjoy some of Europe’s best art (purchase your ticket in advance). Art lovers can then head across the street to the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum.

Afternoon: Enjoy an afternoon siesta in Retiro Park. Then tackle modern art at the Reina Sofía, which displays Picasso’s Guernica (closed Tue).

Evening: Take in a flamenco or zarzuela performance.

While Madrid is a massive city, its historic core—which short-time visitors rarely leave—is compact and manageable. Frame it off on your map: The square called Puerta del Sol marks the center of Madrid. To the west is the Royal Palace. To the east are the great art museums: Prado, Reina Sofía, and Thyssen-Bornemisza. North of Puerta del Sol is Gran Vía, a broad east-west boulevard bubbling with elegant shops and cinemas. Between Gran Vía and Puerta del Sol is a lively pedestrian shopping zone. And southwest of Puerta del Sol is Plaza Mayor, the center of a 17th-century, slow-down-and-smell-the-cobbles district. Everything described here (roughly the area contained in the “Central Madrid” map in this chapter) is within about a 20-minute stroll or a €10 taxi ride of Puerta del Sol.

For exploring, a wonderful chain of pedestrian streets crosses the city east to west, from the Prado to Plaza Mayor (along Calle de las Huertas) and from Puerta del Sol to the Royal Palace (on Calle del Arenal). Stretching north from Gran Vía, Calle de Fuencarral is a trendy shopping-and-strolling pedestrian street.

Madrid has city TIs run by the Madrid City Council, and regional TIs run by the privately owned Turismo Madrid. Both are helpful, but you’ll get more biased information from Turismo Madrid.

The city-run TIs share a website (www.esmadrid.com), a central phone number (+34 915 787 810), and hours (daily 9:30-20:30 or later). The best and most central city TI is on Plaza Mayor. Additional branches are scattered all over the city, often in freestanding kiosks. Look for them near the Prado (facing the Neptune fountain), in front of the Reina Sofía art museum (across the street from the Atocha train station, in the median of the busy road), along Gran Vía at Plaza del Callao, at Plaza de Colón (in the underground passage accessed from Paseo de la Castellana and Calle de Goya), inside Palacio de Cibeles (up the stairs, and to the right), and at the airport (Terminals 2 and 4).

Regional Turismo Madrid TIs share hours and a website (Mon-Sat 8:00-20:00, Sun 9:00-14:00; www.turismomadrid.es). The main branch is just east of Puerta del Sol at Calle de Alcalá 31; branches are also inside the Sol Metro station (inside the underground corridor; this branch open daily 8:00-20:00), at Chamartín train station (near track 20), at Atocha train station (AVE arrivals side; this branch open Sun until 20:00), and at the airport (Terminals 1 and 4).

At most TIs, you can get the Es Madrid English-language monthly, which includes a map and event listings. Themed Madrid for You booklets on various topics (families, museums, viewpoints, gastronomy, and so on) are also available. The regional TIs hand out a handy public transportation map.

Entertainment Guides: For arts and culture listings, the TI’s printed material is good, but you can also pick up the more practical Spanish-language weekly entertainment guide Guía del Ocio (sold cheap at newsstands) or visit www.guiadelocio.com. It lists daily live music (“Conciertos”), museums (under “Arte”—with the latest times, prices, and special exhibits), restaurants (an exhaustive listing), TV schedules, and movies (“V.O.” means original version, “V.O. en inglés sub” or “V.O.S.E.” means a movie is played in English with Spanish subtitles rather than dubbed).

For more information on arriving at or departing from Madrid, including stations and connections, see “Madrid Connections,” at the end of this chapter.

By Train: Madrid’s two train stations, Chamartín and Atocha, are on both Metro and cercanías (suburban train) lines with easy access to downtown Madrid. Chamartín handles most international trains and the AVE (AH-vay) train to and from Segovia. Atocha generally covers southern Spain, as well as AVE trains to and from Barcelona, Córdoba, Granada, Sevilla, and Toledo. Many train tickets include a cercanías connection to or from the train station.

Traveling Between Chamartín and Atocha Stations: You can take the Metro (€2, line 1, 30-40 minutes; see “Getting Around Madrid,” later), but the cercanías trains are faster (€1.70, 6/hour, 13 minutes, Atocha-Chamartín lines C1, C3, C4, C7, C8, and C10 each connect the two stations, lines C3 and C4 also stop at Sol—Madrid’s central square). If you have a rail pass or any regular train ticket to Madrid, you can get a free transfer within three hours of your ticket times. At the Cercanías ticket machine, choose combinado cercanías, then either scan the bar code on your train ticket or punch in a code (labeled combinado cercanías), and choose your destination. These trains depart from Atocha’s track 6 and generally Chamartín’s track 1, 3, 8, or 9—check the salidas inmediatas board to be sure).

By Bus: Madrid has several bus stations, each one handy to a Metro station: Estación Sur de Autobuses (for Ávila, Salamanca, and Granada; Metro: Méndez Álvaro); Plaza Elíptica (for Toledo, Metro: Plaza Elíptica); Moncloa (for El Escorial, Metro: Moncloa); and Avenida de América (for Pamplona and Burgos, Metro: Avenida de América). From any of these, just ride the Metro or a taxi to your hotel.

By Plane: Both international and domestic flights arrive at Madrid’s Barajas Airport. Options for getting into town include public bus, cercanías train, Metro, taxi, and minibus shuttle.

Sightseeing Tips: The Prado and Royal Palace are open daily. The Reina Sofía (with Picasso’s Guernica) is closed on Tuesday, and many other sights are closed on Monday, including the Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial, a popular day trip outside of Madrid (see next chapter). If you’re here on a Sunday, consider visiting the famous El Rastro flea market (year-round) and/or a bullfight (most Sun and holidays in March-mid-Oct plus almost daily during the San Isidro festival in early May-early June).

Theft Alert: Be wary of pickpockets—anywhere, anytime, but especially in crowded areas such as Puerta del Sol, the busy street between the Puerta del Sol and the Prado (Carrera de San Jerónimo), El Rastro flea market, Gran Vía (especially the paseo zone: Plaza del Callao to Plaza de España), anywhere on the Metro (especially the Ópera station), bus #27, and at the airport. Be alert to the people around you: Someone wearing a heavy jacket in the summer is likely a pickpocket. Kids may dress like Americans and work the areas near big sights; anyone under 18 can’t be charged in any meaningful way by the police. Assume any commotion is a scam to distract people about to become victims of a pickpocket. Wear your money belt. For help if you get ripped off, see the next listing.

Tourist Emergency Aid: SATE is an assistance service for tourists who need help with anything from canceling stolen credit cards to reporting a crime (central police station, daily 9:00-24:00, near Plaza de Santo Domingo at Calle Leganitos 19). They can act as an interpreter if you have trouble communicating with the police. Or you can call in your report to the SATE line (24-hour +34 902 102 112, English spoken once you get connected to a person).

Sex Work: While it’s illegal to make money from someone else selling sex (i.e., pimping), sex workers over 18 can solicit legally. Calle de la Montera (leading from Puerta del Sol to Plaza Red de San Luis) is lined with what looks like a bunch of high-schoolers skipping school for a cigarette break. Don’t stray north of Gran Vía around Calle de la Luna and Plaza Santa María Soledad—while the streets may look inviting, this area is bad news.

One-Stop Shopping at El Corte Inglés: Madrid’s dominant department store, El Corte Inglés, fills three huge buildings in the pedestrian zone just off Puerta del Sol. From groceries and event tickets to fashion and housewares, El Corte Inglés has it all. For a building-by-building breakdown, see “Shopping in Madrid,” later.

Bookstores: For books in English, try FNAC Callao (Calle Preciados 28), Casa del Libro (English on basement floor, Gran Vía 29), and El Corte Inglés (guidebooks and some fiction, in its Building 3 Books/Librería branch kitty-corner from main store, fronting Puerta del Sol).

Laundry: For a self-service laundry, try Colada Express at Calle Campomanes 9 (free Wi-Fi, daily 9:00-22:00, mobile +34 657 876 464) or Lavandería at Calle León 6 (self-service Mon-Sat 9:00-22:00, Sun 12:00-15:00; full-service Mon-Sat 9:00-14:00 & 15:00-20:00, +34 914 299 545). For locations see the “Madrid Center Hotels” map on here.

Madrid has excellent public transit. Pick up the Metro map (free at TIs or at Metro info booths in stations with staff); for buses get the fine, free Public Transport map (available at some TIs). The metropolitan Madrid transit website (www.crtm.es) covers all public transportation options (Metro, bus, and suburban rail).

By Metro: Madrid’s Metro is simple, speedy, and cheap. Distances are short, but the city’s broad streets can be hot and exhausting, so a subway trip of even a stop or two saves time and energy. The Metro runs from 6:00 to 1:30 in the morning. At all times, be alert to thieves, who thrive in crowded stations. Metro info: www.metromadrid.es.

Tickets: A single ride ticket within zone A costs €1.50-2, depending on the number of stops you travel; zone A covers most of the city, but not trains to the airport. A 10-ride ticket is €12.20 and valid on the Metro and buses; it can be shared by several travelers with the same destination (two people taking five rides should get one).

To buy either a single ride or 10-ride ticket, you’ll first buy a rechargeable red Multi Card (tarjeta) for €2.50 (nonrefundable—consider it a souvenir). The first Metro ticket you buy will cost at least €4 and be issued on the card; thereafter, you can reload the card with additional rides (viajes). Ticket machines ask you to punch in your destination from the alphabetized list (follow the simple prompts) to load up the correct fare. You can also buy or reload Multi Cards at newspaper stands and Estanco tobacco shops.

I’d skip the tourist ticket (billete túristico) you may see advertised, which covers all Metro and bus rides for a designated time period; unless you’re riding transit like crazy, it’s unlikely to save you money over the 10-ride ticket.

Riding the Metro: Study your Metro map—the simplified “Madrid Metro” map in this chapter can get you started. Lines are color-coded and numbered; use end-of-the-line station names to choose your direction of travel. When entering the Metro system, touch your Multi Card against the yellow pad to open the turnstile (no need to touch it again to exit). Once in the Metro station, signs direct you to the train line and direction (e.g., Linea 1, Valdecarros). To transfer, follow signs in the station leading to connecting lines. Once you reach your final stop, look for the green salida signs pointing to the exits. Use the helpful neighborhood maps to choose the right salida and save yourself lots of walking.

By Bus: City buses, though not as easy as the Metro, can be useful. You can use a Multi Card loaded with a 10-ride ticket (see details earlier). But for single rides, you’ll buy a ticket on the bus, paying the driver in cash (€1.50; bus maps at TI or info booth on Puerta del Sol, poster-size maps usually posted at bus stops, buses run 6:00-24:00, much less frequent Buho buses run all night). The EMT Madrid app finds the closest stops and lines and gives accurate wait times (there’s a version in English). Bus info: www.emtmadrid.es.

By Taxi or Uber: Madrid’s taxis are reasonably priced and easy to hail. A green light on the roof and/or the word Libre on the windshield indicates that a taxi is available. Foursomes travel almost as cheaply by taxi as by Metro; for example, a ride from the Royal Palace to the Prado costs about €10. After the drop charge (about €3), the per-kilometer rate depends on the time: Tarifa 1 (€1.05/kilometer) is charged Mon-Fri 6:00-21:00; Tarifa 2 (€1.20/kilometer) is valid after 21:00 and on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays. If your cabbie uses anything other than Tarifa 1 on weekdays (shown as an isolated “1” on the meter), you’re being cheated.

Rates can be higher outside Madrid. There’s a flat rate of €30 between the city center and any one of the airport terminals. Other legitimate charges include a €3 supplement for leaving any train or bus station, €20 per hour for waiting, and €5 if you call to have the taxi come to you. Make sure the meter is turned on as soon as you get into the cab so the driver can’t tack anything onto the official rate. If the driver starts adding up “extras,” look for the sticker detailing all legitimate surcharges (it should be on the passenger window).

Uber works in Madrid pretty much like it does at home. Outside of peak times, an Uber ride can be slightly cheaper than a taxi.

To sightsee on your own, download my free Madrid City Walk audio tour.

To sightsee on your own, download my free Madrid City Walk audio tour.

Across Madrid is run by Almudena Cros, a well-traveled art history professor. She offers several specialized tours, including one on the Spanish Civil War that draws on her family’s history (generally €70/person, maximum 8 people, book well in advance, also gives good tours for children, mobile +34 652 576 423, www.acrossmadrid.com).

Stephen Drake-Jones, an eccentric British expat, has led walks of historic old Madrid almost daily for decades. A historian with a passion for the Duke of Wellington (the general who stopped Napoleon), Stephen loves to teach history. For €95 you get a 3.5-hour tour with three stops for drinks and tapas—call it lunch (daily at 11:00, maximum 8 people). He also offers a private version (€190/2 people) and themed tours covering the Spanish Civil War, Hemingway’s Madrid, and more (mobile +34 609 143 202, www.wellsoc.org).

Assemble your own group to share the cost of these tours.

Federico and his team of licensed guides lead city walks and museum tours in Madrid and nearby towns. They specialize in family tours and engaging kids and teens in museums, and size their city tours like cups of hot chocolate (small-€150/2 hours, medium-€200/4 hours, large-€250/6 hours, extra large-€300/8 hours, mobile +34 649 936 222, www.spainfred.com).

Letango Tours offers private tours, packages, and stays all over Spain with a focus on families and groups. Carlos Galvin, a Spaniard who led tours for my groups for more than a decade, his wife Jennifer from Seattle, and their team of guides in Madrid offer a kid-friendly “Madrid Discoveries” tour that mixes a market walk and history with a culinary-and-tapas introduction (€295/group of up to 5, kids free, 3-plus hours). They also lead tours to Barcelona, whitewashed villages, wine country, and more (www.letango.com, tours@letango.com).

At Madridivine, David Gillison and his team enthusiastically share their passion for Spanish culture through food and walking tours of historic Madrid. They connect you with locals, food, and wine from an insider’s perspective (€200/group of up to 6, 3 hours, food and drinks extra—usually around €40, www.madridivine.com, info@madridivine.com).

Other good, licensed local guides include: Inés Muñiz Martin (guiding since 1997 and a third-generation Madrileña, €125-190/2-5 hours, €35 extra on weekends and holidays, mobile +34 629 147 370, www.immguidedtours.com) and Susana Jarabo (with a master’s in art history, €200/4 hours, tours by bike or Segway possible, available March-Aug, mobile +34 667 027 722, susanjarabo@yahoo.es).

Madrid City Tour makes two different hop-on, hop-off circuits through the city: historic and modern (each with 16-21 stops, 1.5 hours, buses depart every 15 minutes). The two routes intersect at the south side of Puerta del Sol and in front of Starbucks across from the Prado. Your ticket covers both loops (€22/1 day, €26/2 consecutive days, pay driver, recorded narration, daily 9:30-22:00, Nov-Feb 10:00-18:00, +34 917 791 888, www.madridcitytour.es).

Julià Travel offers bus tours in Madrid and side trips to nearby destinations. Their 2.5-hour Madrid tour is narrated by a live guide in two or three languages (€29, drink stop at Hard Rock Café, one shopping stop, no museum visits, daily at 9:00 and 15:00, no reservation required—just show up 15 minutes before departure). Tours leave from their office at Calle San Nicolás 7 near Plaza de Ramales, just south of Plaza de Oriente (+34 915 599 605, www.juliatravel.com).

A ride on public bus #27 from the museum neighborhood up Paseo del Prado and Paseo de la Castellana to the Puerta de Europa and back gives visitors a glimpse of the modern side of Madrid (see here), while a ride on electric minibus #M1 takes you through the characteristic, gritty old center (see here).

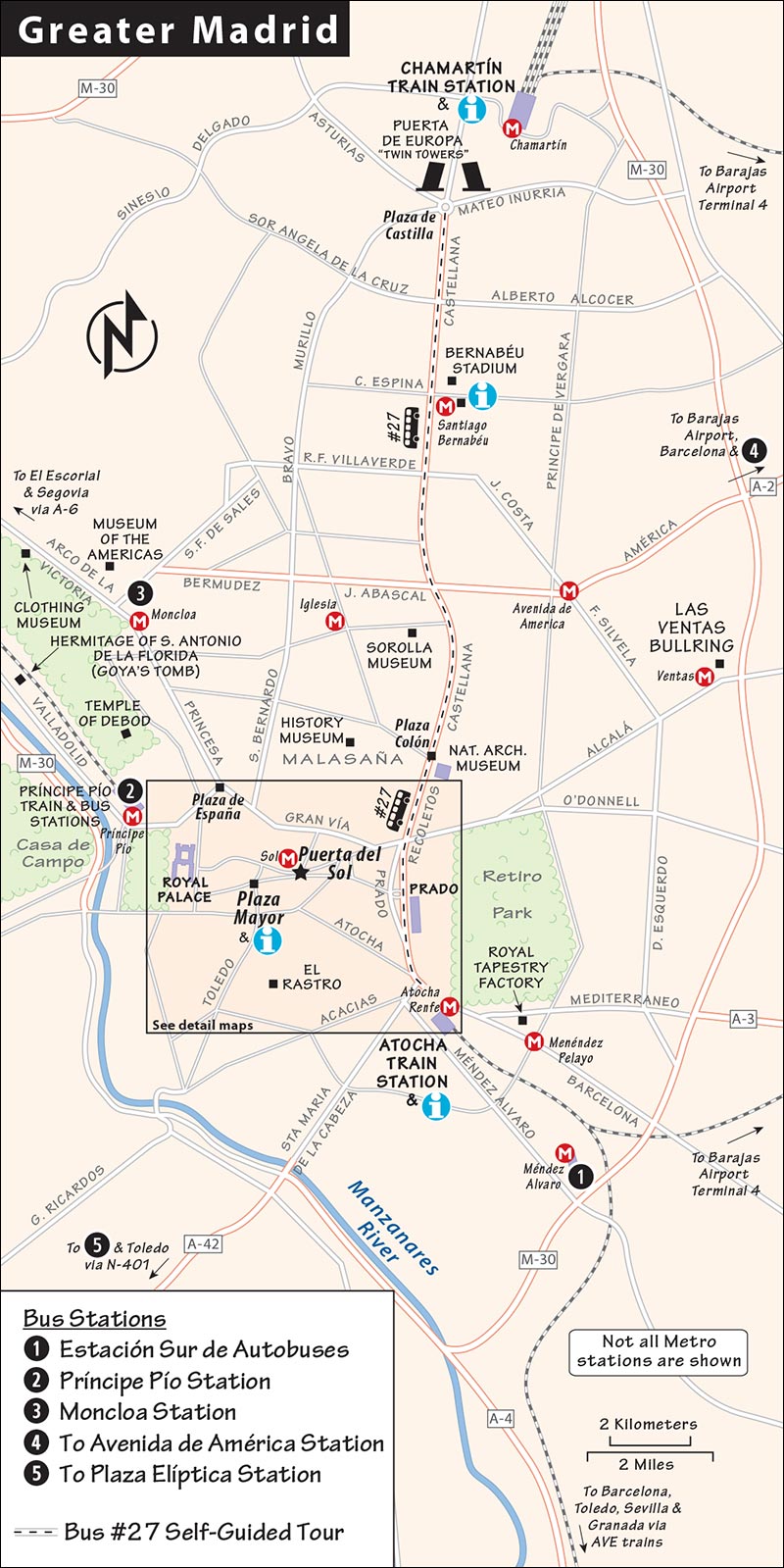

Map: Madrid’s Historic Core Walk

5 Mesones and Mercado de San Miguel

6 Church and Convent of Corpus Christi

8 Assassination Attempt Memorial

10 Royal Palace

Two self-guided walks provide a look at two sides of Madrid. For a taste of old Madrid, start with my “Historic Core Walk,” which winds through the center. My “Gran Vía Walk” lets you glimpse a more modern side of Spain’s capital.

Download my free Madrid City Walk audio tour, which complements this section.

Download my free Madrid City Walk audio tour, which complements this section.

Madrid’s historic center is pedestrian-friendly and filled with spacious squares, a trendy market, bulls’ heads in a bar, and a cookie-dispensing convent. Allow about two hours for this self-guided, mile-long walk that loops from Madrid’s central square, Puerta del Sol, to the Royal Palace and back to the square (Metro: Sol).

• Start in the middle of the square, by the equestrian statue of King Charles III, and survey the scene.

The bustling Puerta del Sol, rated ▲▲, is Madrid’s—and Spain’s—center. In recent years, the square has undergone a facelift to become a mostly pedestrianized and wide-open gathering place. For Spaniards, this place (with its iconic Tío Pepe sign) is probably the most recognizable spot in the country. It’s a popular site for political demonstrations and national celebrations. For Madrileños, Puerta del Sol is a transportation hub for the Metro, cercanías (suburban trains), and several main roads. It’s also a magnet for strolling locals, sightseers, pickpockets, revelers, and locals dressed as cartoon characters who pose for photos for a fee. In many ways, it’s the soul of the city.

The equestrian statue in the middle of the square honors the man who established the Puerta del Sol as an urban hub—King Charles III (1716-1788). His enlightened urban policies earned him the affectionate nickname “the best mayor of Madrid.” He decorated city squares with beautiful fountains, got those meddlesome Jesuits out of city government, established the public-school system, mandated underground sewers, opened his private Retiro Park to the public, built the Prado, made the Royal Palace the wonder of Europe, and generally cleaned up Madrid. (For more on Charles, see here.)

Head to the slightly uphill end of the square and find the statue of a bear pawing a tree—not much to look at, but locals love it. This image has been a symbol of Madrid since medieval times. Bears used to live in the royal hunting grounds outside the city. And the madroño trees produce a berry that makes the traditional madroño liqueur.

Charles III faces a red-and-white building with a bell tower. This was Madrid’s first post office, which Charles III founded in the 1760s. Today it’s the county governor’s office, home to the “president” who governs greater Madrid. The building is notorious for having once been dictator Francisco Franco’s police headquarters. A tragic number of those detained and interrogated by the Franco police tried to “escape” by jumping out its windows to their deaths.

Appreciate the harmonious architecture of the buildings that circle the square—yellow-cream, four stories, balconies of iron, shuttered windows, and balustrades along the rooflines.

Crowds fill the square on New Year’s Eve as the rest of Spain watches the Times Square-style action on TV. The bell atop the governor’s office chimes 12 times, while Madrileños eat one grape for each ring to bring good luck through each of the next 12 months.

• Cross the square and street to the governor’s office.

Look down at the sidewalk directly in front of the entrance to the governor’s office. The plaque marks “kilometer zero,” the symbolic center of Spain, from which the country’s six main highways radiate (as the plaque shows). Standing on the zero marker with your back to the governor’s office, get oriented visually: Directly ahead, at 12 o’clock, is the famous Tío Pepe sign. This big neon billboard—25 feet high and 80 feet across—pictures a jaunty Andalusian caballero with a sombrero and guitar. He’s been advertising a local sherry wine since the 1930s.

Beyond the sign is a thriving pedestrian commercial zone, anchored by the huge department store, El Corte Inglés. At two o’clock starts the seedier Calle de la Montera, a street with shady characters and prostitutes that leads to the trendy, pedestrianized Calle de Fuencarral. At three o’clock is a big Apple store; the Prado is about a mile farther to your right. Back over at 10 o’clock is the pedestrianized street called Calle del Arenal...where we’ll finish this walk.

Now turn around. On the walls flanking the entrance to the governor’s office are two white marble plaques. These commemorate two important dates, when Madrileños came together in times of dire need. The plaque on the right marks an event from 1808. An angry crowd gathered here to rise up against an invasion by France. Suddenly, French soldiers stormed the square and began massacring the Spaniards. The event galvanized the country, which eventually drove out the French. The painter Francisco de Goya, whose studio was not far from here, captured the event in his famous painting, The Third of May, which is now in the Prado museum.

The plaque to the left of the entry remembers a more recent tragedy, on March 11, 2004. That’s when brave Spanish citizens helped fellow citizens in the wake of horrific terrorist bombings in the city. We have our 9/11—Spain has its 3/11.

Finally, notice the civil guardsmen at the entry. They may be wearing curious hats with square backs, which it’s said were cleverly designed so that the guards can lean against the wall while enjoying a cigarette.

On the corner of Puerta del Sol and Calle Mayor (downhill end of Puerta del Sol) is the busy, recommended confitería La Mallorquina, “fundada en 1.894.” Go inside for a tempting peek at racks with goodies hot out of the oven. The crowded takeaway section is in front; the stand-up counter is in back. Enjoy observing the churning energy of Madrileños popping in for a fast coffee and a sweet treat. The shop is famous for its Napolitana pastry (like a squashed, custard-filled croissant). Or sample Madrid’s answer to doughnuts, rosquillas (tontas means “silly”—plain, and listas means “all dressed up and ready to go”—with icing). Buy something...there’s no special system, just order and pay. The café upstairs is more genteel, with nice views of the square.

Before leaving the shop, find the tiles above the entrance door and above the bar with the 18th-century views of Puerta del Sol. This was before the square was widened, when a church stood at its top end. Compare this with today’s view out the door.

Puerta del Sol (“Gate of the Sun”) is named for a long-gone gate carved with a rising sun, which once stood at the eastern edge of the old city. From here, we begin our walk through the historic town that dates back to medieval times.

• Head west on busy Calle Mayor, just past McDonald’s. Go a few steps up the side-street on the left, then angle right on the pedestrian-only street called...

The street sign shows the post coach heading for that famous first post office. Medieval street signs posted on the lower corners of buildings included pictures so the illiterate (and monolingual tourists) could “read” them. Fifty yards up the street on the left, at Calle San Cristóbal, is Pans & Company, a popular Catalan sandwich chain offering lots of healthy choices. While Spaniards tend to consider American fast food unhealthy—both culturally and physically—they love it. McDonald’s and Burger King are thriving in Spain.

• Continue up Calle de Postas, and take a slight right on Calle de la Sal through the arcade, where you emerge into...

This vast, cobbled square (worth ▲▲) dates back to Madrid’s glory days, the 1600s. Back then, this—not Puerta del Sol—was Madrid’s main square (plaza mayor). The equestrian statue (wearing a ruffled collar) honors Philip III, who made this square the centerpiece of the budding capital in 1619. Philip’s dad (Philip II) had founded Madrid, and the son transformed a former marketplace into this state-of-the-art Baroque plaza.

The square is 140 yards long and 100 yards wide, enclosed by four-story buildings with symmetrical windows, balconies, slate roofs, and steepled towers. Each side of the square is uniform, as if a grand palace were turned inside-out. This distinct look, pioneered by architect Juan de Herrera (who finished El Escorial), is found all over Madrid.

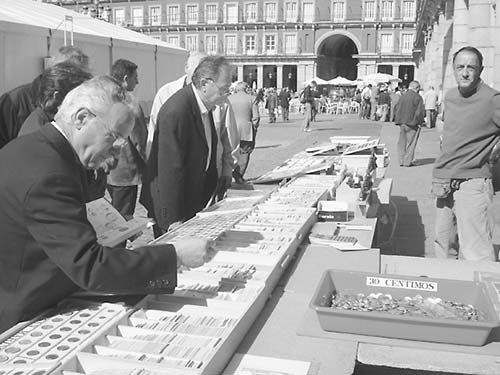

This site served as the city’s 17th-century open-air theater. Upon this stage, much Spanish history has been played out. The square’s lampposts have reliefs on the benches below illustrating major episodes: bullfights fought here, dancers and masked revelers at Carnevale, royal pageantry, a horrendous fire in 1790, and events of the gruesome Inquisition. During the Inquisition, many were tried here—suspected heretics, Protestants, Jews, tour guides without a local license, and Muslims whose “conversion” to Christianity was dubious. The guilty were paraded around the square before their executions, wearing placards listing their many sins (bleachers were built for bigger audiences, while the wealthy rented balconies). The heretics were burned, and later, criminals were slowly strangled as they held a crucifix, hearing the reassuring words of a priest as the life was squeezed out of them with a garrote. Up to 50,000 people could crowd into this square for such spectacles.

The square’s buildings are mainly private apartments. Want one? Costs run from €400,000 for a tiny attic studio to €2 million and up for a 2,500-square-foot flat. The square is painted a democratic shade of burgundy—the result of a citywide poll. Since the end of decades of dictatorship in 1975, Spain has had a passion for voting. Three different colors were painted as samples on the walls of this square, and the city voted for its favorite.

The building to Philip’s left, on the north side beneath the twin towers, was once home to the baker’s guild and now houses the TI, which is wonderfully air-conditioned.

A stamp-and-coin market bustles at Plaza Mayor on Sundays (10:00-14:00). Day or night, Plaza Mayor is a colorful place to enjoy an affordable cup of coffee or overpriced food. Throughout Spain, lesser plazas mayores provide peaceful pools in the whitewater river of Spanish life.

• Head to #26, which is under the arcade just to the left of the twin towers. This is a bar called...

For some Andalú (Andalusian) ambience, an entertaining (if gruff) staff, and lots of fascinating (if gruesome) bullfighting lore, step inside. Order a drink at the bar and sightsee while you sip. Warning: First check the price list posted outside the door to understand the price tiers: “barra” indicates the price at the bar; “terraza” is the price at an outdoor table. A caña (small draft beer), Coke, or agua mineral should cost about €3. Your drink may come with a small, free tapa, per the old Spanish tradition. But to avoid being charged by surprise, clarify, “Gratis?”

The interior is a temple to bullfighting, festooned with gory decor. Notice the breathtaking action captured in the many photographs. Look under the stuffed head of Barbero the bull (center, facing the bar). At eye level you’ll see a puntilla, the knife used to put poor Barbero out of his misery at the arena. The plaque explains: weight, birth date, owner, date of death, which matador killed him, and the location.

Just to the left of Barbero is a photo of longtime dictator Franco with the famous bullfighter Manuel Benítez Pérez—better known as El Cordobés, the Elvis of bullfighters and a working-class hero.

At the top of the stairs going down to the WC, find the photo of El Cordobés and Robert Kennedy—looking like brothers. Three feet to the left of them (and elsewhere in the bar) is a shot of Che Guevara enjoying a bullfight.

Below and left of the Kennedy photo is a picture of El Cordobés’ illegitimate son being gored. Disowned by El Cordobés senior, yet still using his dad’s famous name after a court battle, the junior El Cordobés is one of this generation’s top fighters.

At the end of the bar, in a glass case, is the “suit of lights” the great El Cordobés wore in an ill-fated 1967 fight, in which the bull gored him. El Cordobés survived; the bull didn’t. Find the photo of Franco with El Cordobés at the far end, to the left of Segador the bull.

In the case with the “suit of lights,” notice the photo of a matador (not El Cordobés) horrifyingly hooked by a bull’s horn. For a series of photos showing this episode (and the same matador healed afterward), look to the right of Barbero back by the front door.

Below that series is a strip of photos showing José Tomás—a hero of this generation (with the cute if bloody face)—getting his groin gored. Tomás is renowned for his daring intimacy with the bull’s horns—as illustrated here.

Leaving the bull bar, turn right and notice the La Favorita hat shop (at #25). See the plaque in the pavement honoring the shop, which has served the public since 1894.

Consider taking a break at one of the tables on Madrid’s grandest square. Cafetería Margerit (nearby) occupies Plaza Mayor’s sunniest corner and is a good place to enjoy a coffee with the view. The scene is easily worth the extra euro you’ll pay for the drink.

• Leave Plaza Mayor on Calle de Ciudad Rodrigo (at the northwest corner of the square), passing a series of solid turn-of-the-20th-century storefronts and sandwich joints, such as Casa Rúa (to the left), famous for their cheap bocadillos de calamares—fried squid rings on a small baguette.

Mistura Ice Cream (across the lane at Ciudad Rodrigo 6) serves fine coffee and quality ice cream. Its cellar is called the “chill zone” for good reason—an oasis of cool and peace, ideal for enjoying your treat.

Emerging from the arcade, turn left and head downhill toward the iron-covered market hall. Before entering the market, look downhill to the left, down a street called Cava de San Miguel.

Lining the street called Cava de San Miguel is a series of traditional dive bars called mesones. If you like singing, sangria, and sloppy people, come back after 22:00 to visit one. These cave-like bars, stretching far back from the street, get packed with Madrileños out on dates who—emboldened by wine and the setting—are prone to suddenly breaking out in song. It’s a lowbrow, electric-keyboard, karaoke-type ambience, best on Friday and Saturday nights. The odd shape of these bars isn’t a contrivance for the sake of atmosphere—Plaza Mayor was built on a slope, and these underground vaults are part of a structural system that braces the leveled plaza.

For a much more refined setting, pop into the Mercado de San Miguel (daily 10:00-24:00). This historic iron-and-glass structure from 1916 stands on the site of an even earlier marketplace. Renovated in the 21st century, the city’s oldest surviving market hall now hosts some 30 high-end vendors of fresh produce, gourmet foods, wines by the glass, tapas, and full meals. Locals and tourists alike pause here for its food, natural-light ambience, and social scene.

Go on an edible scavenger hunt by simply grazing down the center aisle. You’ll find fish tapas, gazpacho and pimientos de Padrón (fried small green peppers), artisan cheeses, and lots of olives. Skewer them on a toothpick and they’re called banderillas—for the decorated spear a bullfighter thrusts into the bull’s neck. The Campo Real olives are a Madrid favorite. You’ll find a draft vermut (Vermouth) bar with kegs of the sweet local dessert wine, along with sangria and sherry (V.O.R.S. means, literally, very old rare sherry—dry and full-bodied). Finally, the San Onofre bar is for your sweet tooth. You’ll probably hear “Que aproveche!”—the Spanish version of bon appétit.

• Exit the market at the far end and turn left, heading downhill on Calle del Conde de Miranda. At the first corner, turn right and cross the small plaza to the brick church in the far corner.

The proud coats of arms over the main entry announce the rich family that built this Hieronymite church and convent in 1607. In 17th-century Spain, the most prestigious thing a noble family could do was build and maintain a convent. To harvest all the goodwill created in your community, you’d want your family’s insignia right there for all to see. (You can see the donating couple, like a 17th-century Bill and Melinda Gates, kneeling before the communion wafer in the central panel over the entrance.) Inside is a cool and quiet oasis with a Last Supper altarpiece.

Now for a unique shopping experience. A dozen steps to the right of the church entrance is its associated convent—it’s the big brown door on the left, at Calle del Codo 3 (Mon-Sat 9:30-13:00 & 16:30-18:30, closed Sun). The sign reads Venta de Dulces (Sweets for Sale). To buy goodies from the cloistered nuns, buzz the monjas button, then wait patiently for the sister to respond over the intercom. Say “dulces” (DOOL-thays), and she’ll let you in. When the lock buzzes, push open the door. It will be dark—look for a glowing light switch to turn on the lights. Walk straight in and to the left, then follow the sign to the torno—the lazy Susan that lets the sisters sell their baked goods without being seen. Scan the menu, announce your choice to the sequestered sister (she may tell you she has only one or two of the options available), place your money on the torno, and your goodies (and change) will appear. Galletas (shortbread cookies) are the least expensive item (a medio-kilo costs about €10). Or try the pastas de almendra (almond cookies).

• Continue uphill on Calle del Codo, where, in centuries past, those in need of bits of armor shopped (as depicted on the tiled street sign on the building). Bend sharply left with the street—named “Elbow Street”—and head toward the Plaza de la Villa. Before entering the square, notice an old door to the left of the Real Sociedad Económica sign, made of wood lined with metal. This is considered the oldest door in town on Madrid’s oldest building—inhabited since 1480. It’s set in a Mudejar keyhole arch. Remember, for many centuries (from 711 to 1492), Spain was largely Muslim, and that influence lived on in its Mudejar craftspeople. Look up to see a tower, once used as a prison.

Now continue into the square called Plaza de la Villa, dominated by Madrid’s...

The impressive structure features Madrid’s distinctive architectural style—symmetrical square towers, topped with steeples and a slate roof...Castilian Baroque. The building was Madrid’s Town Hall. Over the doorway, the three coats of arms sport many symbols of Madrid’s rulers: Habsburg crowns on each, castles of Castile (in center shield), and the city symbol—the berry-eating bear (shield on left). This square was the ruling center of medieval Madrid in the centuries before it became an important capital.

Imagine how Philip II took this city by surprise in 1561 when he decided to move the capital of Europe’s largest empire (even bigger than ancient Rome) from Toledo to humble Madrid. Madrid proved to be a perfect choice. It was located in the geographical center of the country. It united the two great kingdoms of Philip’s great-grandparents, Ferdinand and Isabel. And with plenty of room to grow, Madrid became the ideal spot to administer the growing Spanish empire.

Philip II went on a building spree, and his son Philip III continued it. This particular building reflects the hasty development. It’s glorious, yes—but like much of Madrid, it’s built with inexpensive brick rather than costly granite.

The venerable Town Hall also bore witness to the decline of Spain’s fortunes after the Golden Age. The statue in the little garden is of Philip II’s admiral, Don Alvaro de Bazán, who defeated the Turkish Ottomans at the battle of Lepanto in 1571. This was Spain’s last great victory. Mere months after Bazán’s death in 1588, his “invincible” Spanish Armada was destroyed by England...and Spain’s empire began its slow fade.

• By the way, a cute little shop selling traditional monk- and nun-made pastries is just down the lane (El Jardin del Convento, at Calle del Cordón 1, on the back side of the cloistered convent you dropped by earlier).

From here, walk along busy, bus-lined Calle Mayor, which leads downhill (along the right side of the Town Hall) toward the Royal Palace. You’ll pass a fine little shop specializing in books about Madrid (at #80, on the right). A few blocks down Calle Mayor, where the street opens up a bit on the left, is a small plaza in front of a church, where you’ll find the...

This statue memorializes a 1906 assassination attempt. The target was Spain’s King Alfonso XIII and his bride, Victoria Eugenie, as they paraded by on their wedding day. While the crowd was throwing flowers, an anarchist (as terrorists used to be called) threw a bouquet lashed to a bomb from a balcony at #84 (across the street). He missed the royal newlyweds, but killed 28 people. The king and queen went on to live to a ripe old age, producing many great-grandchildren, including the current king, Felipe VI.

• Continue down Calle Mayor one more block to a busy street, Calle de Bailén. Take in the big, domed...

Madrid’s massive, gray-and-white cathedral (Catedral de Nuestra Señora de la Almudena, 110 yards long and 80 yards high) opened in 1993, 100 years after workers started building it. This is the side entrance for tourists. Climbing the steps to the church courtyard, you’ll come to a monument to Pope John Paul II’s 1993 visit, when he consecrated Almudena—ending Madrid’s 300-year stretch of requests for a cathedral of its own.

Unlike in most Spanish cities, Madrid’s churches aren’t its most interesting sights. Madrid was built as a capital, so its main landmarks are governmental rather than religious. This cathedral is worthwhile, but if you’re running out of steam, it’s skippable.

If you go in (€1 donation requested), stop in the center, immediately under the dome, and face the altar. Beyond it, colorful paintings—rushed to completion for the pope’s ’93 visit—brighten the apse. In the right transept the faithful venerate a 15th-century Gothic altarpiece with a favorite statue of the Virgin Mary—a striking treasure considering the otherwise 20th-century Neo-Gothic interior. Peer down at the glittering 5,000-pipe organ in the rear of the nave.

The church’s historic highlight is directly behind the altar: a 13th-century coffin. It’s made of painted leather on wood, and depicts scenes of cows, horses, and strolling people. The coffin is now empty, but it once held Madrid’s patron saint, Isidro. The story goes that Isidro was only a humble farmer, but he was exceptionally devout. One day, he was visited by angels. They agreed to plow his fields so he could devote himself to praying. When Isidro died, he was buried in this simple coffin. Forty years later, the coffin was opened, and his body was still perfectly preserved. This miracle convinced the pope to canonize Isidro. He is now the patron saint of farmers, and of the city of Madrid.

• Leave the church from the transept where you entered, go out to the street, and turn left. Hike around the church to its rarely used front door. Climb the cathedral’s front steps and face the imposing...

Since the ninth century, this spot has been Madrid’s center of power: from Moorish castle to Christian fortress to Renaissance palace to the current structure, built in the 18th century. With its expansive courtyard surrounded by imposing Baroque architecture, it represents the wealth of Spain before its decline. Its 2,800 rooms, totaling nearly 1.5 million square feet, make it Europe’s largest palace. Stretching toward the mountains on the left is the vast Casa del Campo (a former royal hunting ground, now a city park).

• You could visit the palace now, using my self-guided tour (see here.

Or, to follow the rest of this walk back to Puerta del Sol, continue one long block north up Calle de Bailén (walking alongside the palace) toward the Madrid Tower skyscraper. This was a big deal in the 1950s when it was one of the tallest buildings in Europe (460 feet) and the pride of Franco and his fascist regime. The tower marks Plaza de España, and the end of my “Gran Vía Walk” (see here). To Spaniards, it symbolizes the boom time the country enjoyed when it sided with the West during the Cold War (allowing the US and not the USSR to build military bases in Spain).

Walk to where the street opens up and turn right, facing the statue of a king on a horse, the park, and the Royal Theater.

As its name suggests, this square faces east. The grand yet people-friendly plaza is typical of today’s Europe, where energetic governments are converting car-congested wastelands into inviting public spaces. Where’s the traffic? Under your feet. A former Madrid mayor who spearheaded the project earned the nickname “The Mole” for all the digging he did.

Notice the quiet. You’re surrounded by more than three million people, yet you can hear the birds, bells, and fountain. The park is decorated with statues of Visigothic kings who ruled from the fifth to eighth century. Romans allowed them to administer their province of Hispania on the condition that they’d provide food and weapons to the empire. The Visigoths inherited real power after Rome fell, but lost it to invading Moors in 711. Throughout Spain’s history, the monarchs have traced their heritage back to these distant Visigothic ancestors. The fine bronze equestrian statue of Philip IV was a striking technical feat in its day, as the horse rears back dramatically balanced atop its fragile ankles. It was only made possible with the help of Galileo’s clever calculations (and by using the tail for extra support).

The king faces the 1,700-seat Royal Theater (Teatro Real), built in the mid-1800s and rebuilt in 1997. It hosts traditional opera, ballets, concerts, and that unique Spanish form of light opera called zarzuela.

• Walk along the right side of the Royal Theater to...

This square is marked by a statue of Isabel II, who ruled Spain in the 19th century and was a great patron of the arts. Although she’s immortalized here, Isabel had a rocky reign. She was a conservative out of step with Spain’s march toward democracy. A revolution in 1868 forced her to abdicate—bringing Spain its first (brief) taste of self-rule—and Isabel lived out her life in exile. Today, Isabel’s statue stands before her most lasting legacy—the Royal Theater she built.

Facing the opera house is an old cinema (now closed and under renovation). This grand movie palace from the 1920s is another example of Spain’s persistent conservatism. As the rest of the world embraced Hollywood movies and their liberal mores, Spain approached it cautiously. During Franco’s conservative rule, many foreign movies were banned. Others were allowed only if they were dubbed into Spanish, so Franco’s censors could edit out sexual innuendo or liberal political references.

• From here, follow Calle del Arenal (on the right side of the square), walking gradually uphill. You’re heading straight to Puerta del Sol.

As depicted on the tiled street signs, this was the “street of sand”—where sand was stockpiled during construction. Each cross street is named for a medieval craft that, historically, was plied along that lane (for example, “Calle de Bordadores” means “Street of the Embroiderers”). Wander slowly uphill. As you stroll, imagine this street as a traffic inferno—which it was until the city pedestrianized it a decade ago (and now monitors it with police cameras atop posts at intersections). Notice also how orderly the side streets are. Where a mess of cars once lodged chaotically on the sidewalks, orderly bollards (bolardos) now keep vehicles off the walkways. The fancier facades (such as the former International Hotel at #19—look up to see the elaborate balconies) are in the “eclectic” style (Spanish for Historicism—meaning a new interest in old styles) of the late 19th century.

Continue 200 yards up Calle del Arenal to a brick church on the right. As you walk, consider how many people are simply out strolling. The paseo is a strong tradition in this culture—people of all generations enjoy being out, together, strolling. And local governments continue to provide more and more pedestrianized boulevards to make the paseo better than ever.

The brick St. Ginés Church (on the right) means temptation to most locals. It marks the turn to the best chocolatería in town. From the uphill corner of the church, look to the end of the lane where—like a high-calorie red-light zone—a neon sign spells out Chocolatería San Ginés...every local’s favorite place for hot chocolate and churros (always open). Also notice the charming bookshop clinging like a barnacle to the wall of the church. It’s been selling books on this spot since 1650.

Next door is the Joy Eslava disco, a former theater famous for operettas in the Gilbert and Sullivan days and now a popular club. In Spain, you can do it all when you’re 18 (buy tobacco, drink, drive, serve in the military). This place is an alcohol-free disco for the younger kids until midnight, when it becomes a thriving adult space, with the theater floor and balconies all teeming with clubbers. Their slogan: “Go big or go home.”

Farther up on the right (at #7) is Ferpal, an old-school deli with an inviting bar and easy takeout options. Wallpapered with ham hocks, it’s famous for selling the finest Spanish cheeses, hams, and other tasty treats. Spanish saffron is half what you’d pay for it back in the US. While they sell quality sandwiches, cheap and ready-made, it’s fun to buy some bread and—after a little tasting—choose a ham or cheese for a memorable picnic or snack. If you’re lucky, you may get to taste a tiny bit of Spain’s best ham (Ibérico de Bellota). Close your eyes and let the taste fly you to a land of very happy acorn-fed pigs.

Across the street, in a little mall (at #8), are a couple of sights celebrating Spain’s answer to Mickey Mouse, called “Ratón Pérez”—Perez the Mouse. First, find the six-inch-tall bronze statue of the beloved rodent in the lobby. Ratón Pérez first appeared in a children’s book in the late 1800s, and kids have adored him ever since. He also serves as Spain’s tooth fairy, leaving money under kids’ pillows when they lose a tooth. Upstairs is the fanciful Casita Museo de Ratón Pérez (€3, daily, Spanish only) with a fun window display. A steady stream of adoring children and their parents pour through here to learn about this wondrous mouse.

Just uphill (at #6, on the left) is an official retailer of Real Madrid football (soccer) paraphernalia. Many European football fans come to Madrid simply to see its 80,000-seat Bernabéu Stadium. Madrid is absolutely crazy about football. They have two teams: the rich and successful Real Madrid, and the working-class underdog, Atlético. It’s like David and Goliath, or the Yankees vs. the Mets. Step inside to see posters of the happy team posing with the latest trophy.

Across the street at #5 is Pronovias, a famous Spanish wedding-dress shop that attracts brides-to-be from across Europe. These days, the current generation of Spaniards often just shack up without getting married. Those who do get married are more practical—preferring a down payment on a condo to a fancy wedding with a costly dress.

• You’re just a few steps from where you started this walk, at Puerta del Sol. Back in the square, you’re met by a statue popularly known as La Mariblanca. The statue, which is at least 400 years old, represents a kind of Spanish Venus, possibly a fertility goddess. at her feet, she has Madrid’s coat of arms, with our old friend, the bear and the berry tree. today, La Mariblanca stands tall amid all the modernity, as she blesses the people of this great city.

For a walk down Spain’s version of Fifth Avenue, stroll the Gran Vía. Built primarily between 1910 and the 1930s, this boulevard, worth ▲, affords a fun view of early-20th-century architecture and a chance to be on the street with workaday Madrileños. As you walk, you’ll notice that Madrid’s main boulevard was renovated with wide sidewalks and traffic is mostly limited to buses and taxis. I’ve broken this self-guided walk into five sections, each of which was the ultimate in its day, starting near Plaza de Cibeles and ending at Plaza de España.

• Start at the skyscraper at Calle de Alcalá #42 (Metro: Banco de España).

This 1920s skyscraper has a venerable café on its ground floor (free entry to enjoy its belle époque-style interior) and the best rooftop view around. Ride the elevator to the seventh-floor Azotea roof terrace/lounge and bar (€5, daily 11:00-23:00), a fine place to nurse a scenic drink on a sunny day.

On the roof, stand under a black Art Deco statue of Minerva, perhaps put here to associate Madrid with this mythological protectress of culture and high thinking, and survey the city. Start in the far left and work your way around the perimeter for a clockwise tour.

Looking down to the left, you’ll see the gold-fringed dome of the landmark Metropolis building (inspired by Hotel Negresco in Nice), once the headquarters of an insurance company. It stands at the start of the Gran Vía and its cancan of proud facades celebrating the good times in pre-civil war Spain. On the horizon, the Guadarrama Mountains hide Segovia. Farther to the right, in the distance, skyscrapers mark the city’s north gate, Puerta de Europa (with its striking slanted twin towers peeking from behind other towers). Round the terrace corner. The big traffic circle and fountain below are part of Plaza de Cibeles, with its ornate and bombastic cultural center and observation deck (Palacio de Cibeles—built in 1910 as the post-office headquarters, and since 2006 the Madrid City Hall). Behind that is the vast Retiro Park. Farther to the right (at the next corner of the terrace), the big low-slung building surrounded by green is the Prado Museum.

• Take the elevator back down and cross the busy boulevard immediately in front of Círculo de Bellas Artes to reach the start of Gran Vía.

This first stretch, from the Banco de España Metro stop to the Gran Vía Metro stop, was built in the 1910s as a strip of luxury stores. The Bar Chicote (at #12, on the right, marked Museo Chicote) is a classic cocktail bar that welcomed Hemingway and the stars of the day. While the people-watching and window-shopping can be enthralling, be sure to look up and enjoy the beautiful facades, too.

By the way, as you stroll along Gran Vía (or anywhere in Madrid), tune into the pedestrian traffic lights. In honor of Pride Day, in 2017 a progressive mayor replaced dozens of these with a version showing two men or two women holding hands as they wait or cross (see photo on previous page).

The second stretch, from the Gran Vía Metro stop to the Callao Metro stop, starts where two recently pedestrianized streets meet up. To the right, Calle de Fuencarral is the trendiest pedestrian zone in town, with famous brand-name shops and a young vibe. To the left, Calle de la Montera is known for prostitution. The action pulses from the McDonald’s down a block or so. Some find it an eye-opening little detour.

The 14-story Telefónica skyscraper (on the right) is nearly 300 feet tall. Perched here at the highest point around, it seems even taller. It was one of the city’s first skyscrapers (the tallest in Spain until the 1950s) with a big New York City feel—and with a tiny Baroque balcony, as if to remind us we’re still in Spain. Telefónica was Spain’s only telephone company through the Franco age (and was notorious for overbilling people, with nothing itemized and no accountability). Today it’s one of Spain’s few giant blue-chip corporations.

With plenty of money and a need for corporate goodwill, the building houses the free Espacio Fundación Telefónica (Tue-Sun 10:00-20:00, closed Mon), with an art gallery, kid-friendly special exhibits, and a fun permanent exhibit telling the story of telecommunications, from telegraphs to iPhones. This exhibit fills the second floor amid exposed steel beams—a space where a thousand “09 girls,” as operators were called back then, once worked.

Farther along is a strip of fashion stores, including Primark at #32, which occupies the building that held the first modern department store in town. Farther along and just before the Callao Metro station, on the left at #37, step into the H&M clothing store for a dose of a grand old theater lobby (don’t confuse it with the smaller H&M at the Primark).

The final stretch, from the Callao Metro stop to Plaza de España, is considered the “American Gran Vía,” built in the 1930s to emulate the buildings of Chicago and New York City. The Schweppes building (Art Deco in the Chicago style, with its round facade and curved windows) was radical and innovative in 1933. This section of Gran Vía is the Spanish version of Broadway, with all the big theaters and plays. These theaters survive thanks to Spanish translations of Broadway shows, productions that get a huge second life here and in Latin America.

Head a few blocks down the street. Across from the Teatro Lope de Vega (on the left, at #60) is a quasi-fascist-style building (on the right, #57). It’s a bank from 1930 capped with a stern statue that looks like an ad for using a good, solid piggy bank. Looking up the street toward the Madrid Tower, the buildings become even more severe.

The Dear Hotel (at #80) has a restaurant on its 14th floor and a rooftop lounge and small bar above that. (Walk confidently through the hotel lobby, ride the elevator to the top, pass through the restaurant, and climb the stairs from the terrace outside to the rooftop.) The views from here are among the best in town.

The end of Gran Vía is marked by Plaza de España (with a Metro station of the same name). While statues of the epic Spanish characters Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (part of a Cervantes monument) are ignored in the park, two Franco-era buildings do their best to scrape the sky above. Franco wanted to show he could keep up with America, so he had the Spain Tower (shorter) and Madrid Tower (taller) built in the 1950s. But they reminded people more of Moscow than the USA. The future of the Plaza de España looks brighter than its past. Major renovations are underway to limit traffic, invite more pedestrians, and link it up with some of the city’s bike paths.

▲▲▲ROYAL PALACE

BETWEEN THE ROYAL PALACE AND PUERTA DEL SOL

▲▲▲Prado Museum (Museo Nacional del Prado)

Map: Madrid’s Museum Neighborhood

▲Royal Botanical Garden (Real Jardín Botánico)

▲▲Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum (Museo del Arte Thyssen-Bornemisza)

▲▲Retiro Park (Parque del Buen Retiro)

▲▲National Archaeological Museum (Museo Arqueológico Nacional/MAN)

Royal Tapestry Factory (Real Fábrica de Tapices)

▲Museum of the Americas (Museo de América)

Clothing Museum (Museo del Traje)

▲Hermitage of San Antonio de la Florida (Ermita de San Antonio de la Florida)

Temple of Debod (Templo de Debod)

▲▲Sorolla Museum (Museo Sorolla)

▲Madrid History Museum (Museo de Historia de Madrid)

Spain’s Royal Palace (Palacio Real) is Europe’s third-greatest palace, after Versailles and Vienna’s Schönbrunn. It has arguably the most sumptuous original interior, packed with tourists and royal antiques. For three centuries, Spain’s royal family has called this place home.

The palace is the product of many kings over several centuries. Philip II (1527-1598) made a wooden fortress on this site his governing center when he established Madrid as Spain’s capital. When that palace burned down, the current structure was built by King Philip V (1683-1746). Philip V wanted to make it his own private Versailles, to match his French upbringing: He was born in Versailles—the grandson of Louis XIV—and ordered his tapas in French. His son, Charles III (whose statue graces Puerta del Sol), added interior decor in the Italian style, since he’d spent his formative years in Italy. These civilized Bourbon kings were trying to raise Spain to the cultural level of the rest of Europe. They hired foreign artists to oversee construction and established local Spanish porcelain and tapestry factories to copy works done in Paris or Brussels. Over the years, the palace was expanded and enriched, as each Spanish king tried to outdo his predecessor.

Today’s palace is ridiculously supersized—with 2,800 rooms, tons of luxurious tapestries, a king’s ransom of chandeliers, frescoes by Tiepolo, priceless porcelain, and bronze decor covered in gold leaf. While these days the royal family lives in a mansion a few miles away, this place still functions as the ceremonial palace, used for formal state receptions, royal weddings, and tourists’ daydreams.

Cost and Hours: €12, €13 with special exhibits; daily 10:00-20:00, Oct-March until 18:00, last entry one hour before closing; from Puerta del Sol, walk 15 minutes down pedestrianized Calle del Arenal (Metro: Ópera); palace can close for royal functions—confirm in advance.

Information: +34 914 548 800, www.patrimonionacional.es.

Crowd-Beating Tips: The palace is free for EU citizens—and most crowded—Monday-Thursday 18:00-20:00 in summer and 16:00-18:00 in winter. On any day, arrive early or go late to avoid lines and crowds.

Visitor Information: Short English descriptions posted in each room complement what I describe in my tour. The museum guidebook demonstrates a passion for meaningless data.

Tours: The €3 audioguide is good. Or download in advance the helpful Royal Palace of Madrid app ($2). The dry English guided tour (€4) runs infrequently and is and not worth a long wait.

Length of This Tour: Allow 1.5 hours.

Services: Free lockers, a WC, and a gift shop are just past the ticket booth. Upstairs you’ll find a more serious bookstore with good books on Spanish history.

Eating: Though the palace has a refreshing air-conditioned $ cafeteria upstairs in the ticket building, I prefer to walk a few minutes and find a place near the Royal Theater or on Calle del Arenal. The recommended $$$ La Botillería, boasting good lunch specials and fin-de-siècle elegance, is pricey but memorable, in a delightful park setting opposite the palace off Plaza de Oriente; for location see map on here.

Self-Guided Tour

Self-Guided TourYou’ll follow a simple one-way circuit on a single floor covering more than 20 rooms.

• Buy your ticket, proceed outside, stand in the middle of the vast open-air courtyard, and face the palace entrance.

The palace sports the French-Italian Baroque architecture so popular in the 18th century—heavy columns, classical-looking statues, a balustrade roofline, and false-front entrance. The entire building is made of gray-and-white local stone (very little wood) to prevent the kind of fire that leveled the previous castle. This became Spain’s center of power; notice how the palace of the king faces the palace of the bishop (the cathedral). Now, imagine the place in its heyday, with a courtyard full of soldiers on parade, or a lantern-lit scene of horse carriages arriving for a ball.

• Enter the palace. Here you’ll find an info desk, cloakrooms, and the meeting point for guided tours.

In the old days, horse-drawn carriages would drop you off inside this covered arcade. Today, stretch limos do the same thing for gala events. When you reach the foot of the Grand Stairs, you’ll see a statue of a toga-clad Charles III—the man most responsible for the lavish rooms we’re about to see (see the “Charles III” sidebar, later).

Stand at the base of the Grand Stairs and take in the scene. Gazing up the imposing staircase, you can see that Spain’s kings wanted to make a big first impression. Whenever high-end dignitaries arrive, fancy carpets are rolled down the stairs (notice the little metal bar-holding hooks).

Begin your ascent, up steps that are intentionally shallow, making your climb slow and regal. At the first landing, the burgundy coat of arms represents the current king, Felipe VI. He’s part of a long tradition of kings stretching directly back to the Bourbon King Philip V, and even further back to Ferdinand and Isabel—and (according to legend) all the way back to the Visigothic kings who arrived after the fall of Rome. Overhead, the white-and-blue ceiling fresco opens up to a heavenly host of graceful female Virtues perched on a mountain of clouds, bestowing their favors on the Spanish monarchy.

Continue up to the top of the stairs. Before entering the first room, look to the right of the door to find a white marble bust of Felipe VI’s great-great-g-g-g-g-great-grandfather Philip V, who began the Bourbon dynasty in Spain in 1700 and had this palace built. He was a direct descendant of France’s “Sun King” Louis XIV...in case you couldn’t tell from the curly wig.

• Now enter the first of the rooms. These were part of King Charles III’s apartments, and even today, they belong to Charles’ descendants. A big modern portrait of today’s royal family seems to welcome visitors to their home: “Mi casa es su casa.”

Immediately you get a sense of the palace’s opulence, brought to you by the man portrayed over the fireplace: Charles III. Charles also appears overhead in the ceiling fresco (in red, with his distinctive narrow face) as the legendary hero Aeneas, standing in the clouds of heaven. Charles gazes up at his mother (as Venus), the sophisticated Italian duchess who raised her son to decorate the palace with Italian Baroque splendor. Charles hired the great Venetian painter Giambattista Tiepolo to do this room and others in the palace (see the “Tiepolo’s Frescoes” sidebar, later). The fresco’s theme, of Vulcan forging Aeneas’s armor, relates to the room’s function as the palace guards’ lounge.

Notice the two fake doors painted on the wall to give the room a more regal symmetry. The old clocks, still in working order, are the first of several we’ll see—part of a collection of hundreds amassed as a hobby by Spain’s royal family. Throughout the palace, pay attention to the carpets. They’re part of a long tradition. Some are from the 18th century and others are new, but all were produced by the same Madrid royal tapestry factory and woven the traditional way—by hand.

The giant portrait depicts Spain’s royal family: the current king Felipe (right), his dad and mom Juan Carlos I and Sofía (center), and his two sisters (left). It was Juan Carlos who resumed the monarchy in the 1970s after Francisco Franco’s dictatorial regime. Rather than end up “Juan the Brief” (as some were nicknaming him), he steered the country toward democracy. (His image appears on older Spanish €1 and €2 coins.) Unfortunately, J. C. showed poor judgment in flaunting his wealth during Spain’s recent economic crisis, and was pressured to hand over the crown to his son, Felipe. Juan Carlos had commissioned this family portrait way back in 1993...and it was completed just in time for his abdication in 2014. (You can imagine the artist adding a few more wrinkles with each passing year.) Notice how Felipe stands apart from the rest of his family—a grouping that’s open to interpretation. Perhaps he’s the baby bird, being nudged from the nest, ready to shoulder the massive responsibility of a proud nation? Felipe’s wife and Spain’s current queen, Letizia Ortiz, isn’t pictured—when this portrait was begun, they had not yet met.

• Proceed into the...

In Charles III’s day, this sparkling, chandeliered venue was the grand ballroom and dining room. The tapestries (like most you’ll see in the palace) are 17th-century Belgian, from designs by Raphael. Appropriately, the ceiling fresco (by Jaquinto, following Tiepolo’s style) depicts a radiant young Apollo driving the chariot of the sun, while Bacchus enjoys wine, women, and song with a convivial gang. The message: A good king drives the chariot of state as smartly as Apollo, so his people can enjoy life to the fullest.

Today this space is used for intimate concerts as well as important ceremonies. This is where Spain formally joined the European Union in 1985, where Spaniards honored their national soccer team after their 2010 World Cup victory, and where Juan Carlos I signed his abdication in 2014.

• The next several rooms were the living quarters of King Charles III (r. 1759-1788). First comes his 5 drawing room (with red-and-gold walls), where the king would enjoy the company of a similarly great ruler—the Roman emperor Trajan—depicted “triumphing” on the ceiling. The heroics of Trajan, one of two Roman emperors born in Spain, naturally made the king feel good. Next, you enter the blue-walled...

This was Charles III’s dining room. The gilded decor you see here and throughout the palace is bronze with gold leaf. The furnishings reflect the tastes of various kings and queens who’ve inhabited this palace. The four paintings are of Charles III’s son and successor, King Charles IV (looking a bit like a dim-witted George Washington), and his wife, María Luisa (who wore the pants in the palace). They’re by Francisco de Goya, who also made copies of these portraits (now in the Prado) to meet the demand for his work. Velázquez’s famous painting, Las Meninas (also in the Prado), originally hung in this room.

The 12-foot-tall clock—in porcelain, bronze, and mahogany—sits on a music box. Reminding us of how time flies, it depicts Chronus, the god of time, both as a child and as an old man. The palace’s clocks are wound—and reset—once a week to keep them accurate.

(Gasp!) The entire room is designed, top to bottom, as a single gold-green-rose ensemble: from the frescoed ceiling to the painted stucco figures, silk-embroidered walls, chandelier, furniture, and multicolored marble floor. Each marble was quarried in, and therefore represents, a different region of Spain. Birds overhead spread their wings, vines sprout, and fruit bulges from the surface. With curlicues everywhere (including their reflection in the mirrors), the room dazzles the eye and mind. It’s a triumph of the Rococo style, with exotic motifs such as the Chinese people sculpted into the corners of the ceiling. (These figures, like many in the palace, were formed from stucco, or wet plaster, that was molded into shape and painted.) The fabric gracing the walls was recently restored. Sixty people spent three years replacing the rotten silk fabric and then embroidering the original silver, silk, and gold threads back on.

Note the table. The Roman temple, birds, and flowers in the design are a micro-mosaic of teeny stones and glass. This was a typical souvenir from any aristocrat’s trip to Rome in the mid-1800s. The chandelier, the biggest in the palace, is mesmerizing, especially with its glittering canopy of crystal reflecting in the wall mirrors.

The mirrors mark this as the king’s dressing room. For a divine monarch, dressing was a public affair. The court bigwigs would assemble here as the king, standing on a platform—notice the height of the mirrors—would pull on his leotards and adjust his wig.

• In the next small room, the silk wallpaper is clearly from modern times—note the intertwined “J. C. S.” of the former monarchs Juan Carlos I and Sofía. Pass through the silk room to reach the...

This was Charles III’s grand bedroom, and he died here in his bed in 1788. His grandson, Ferdinand VII, redid the room to honor the great man. The room’s color scheme recalls the blue robes of the religious order of monks Charles founded here. A portrait of Charles on the wall shows him also in blue. The ceiling fresco shows Charles (kneeling, in armor) establishing his order, with its various (female) Virtues. Along the bottom edge (near the harp player), find the baby in his mother’s arms—that would be Ferdy himself, the long-sought male heir, preparing to continue Charles’ dynasty.

The chandelier is in the shape of the fleur-de-lis (the symbol of the Bourbon family) capped with a Spanish crown. As you exit the room, notice the thick walls between rooms. These hid service corridors for servants, who scurried about mostly unseen.

This tiny but lavish room is paneled with green-white-gold porcelain garlands, vases, vines, babies, and mythological figures. The entire ensemble was disassembled for safety during the civil war. (Find the little screws in the greenery that hides the seams between panels.) Notice the clock in the center with Atlas supporting the world on his shoulders.

This was a study for Charles III. The chandelier was designed to look like a temple with a fountain inside. Its cut crystal shows all the colors of the rainbow. Stand under it, look up, and sway slowly to see the colors glitter. This brilliantly lit room gives a glimpse of what the entire palace would look like whenever it was lit up for an occasion.

• And if it were a special occasion, the next room is where everyone would gather and be dazzled.

This vast venue—perhaps the grandest room in the palace—is the main party room. The parquet floor was the preferred dancing surface when balls were held in this fabulous room. The room is lined with golden vases from China and fine tapestries. The ceiling fresco depicts the historical event that made Spain rich and made this opulent palace possible: Christopher Columbus kneels before Ferdinand and Isabel, presenting exotic souvenirs and his new, native friends (depicted with red skin).

Imagine this hall in action when a foreign dignitary dines here. Up to 12 times a year, the king entertains as many as 144 guests at this bowling lane-size table. If needed, the table can be extended the entire length of the room. The king and queen preside from the center. Find their chairs (slightly higher than the rest, and pulled out from the table a bit). The tables are set with fine crystal and cutlery. And the whole place glitters as the 15 chandeliers (and their 900 bulbs) are fired up.

• Pass through the next room, originally where the royal string ensemble played for parties next door, but now known as the 12 Cinema Room because the royal family once enjoyed Sunday afternoon movies here. From here, move into the...

Some of this 19th-century silver tableware—knives and forks, bowls, salt and pepper shakers, and the big punch bowl—is used in the Gala Dining Room on special occasions. If you look carefully, you can see quirky royal accessories, including a baby’s silver rattle and fancy candle snuffers.

Each display case has a different style from a different period and made by a different factory. The oldest and rarest pieces belonged to the man who built this palace—Philip V. His china actually came from China, before that country was opened to the West. Soon, other European royal families were opening their own porcelain works (such as France’s Sèvres or Germany’s Meissen) to produce high-quality knockoffs (and cutesy Hummel-like figurines). The porcelain technique itself was kept a royal secret. As you leave, check out Isabel II’s excellent 19th-century crystal ware.

• Exit to the hallway and notice the interior courtyard you’ve been circling one room at a time.

Like so many traditional Spanish homes, this palace was built around an open-air courtyard. The royal family lived on this spacious middle floor, staff lived upstairs, and the kitchens, garage, and storerooms were on the ground level. In 2004, this courtyard took on a new use when it was decorated to host King Felipe VI’s royal wedding reception. Felipe married journalist Letizia Ortiz, a commoner (for love), and the two make a point to be approachable with their subjects—they’re very popular. (But then, so was Juan Carlos I, not long before his abdication. Royal life is fickle.)

• Between statues of two of the giants of Spanish royal history (Isabel and Ferdinand), you’ll enter the...

This huge domed chapel is best known among Spaniards as the place for royal funerals. When a monarch dies, the royal coffin lies in state here before making the sad trip to El Escorial to join the rest of Spain’s past royalty (see next chapter). The glass coffin straight ahead contains the entire body of St. Felix, given to the Spanish king by the pope in the 19th century. Note the glassed-in “crying room” to the left for royal babies. While the royals rarely worship here (they prefer the cathedral adjacent to the palace), the thrones are here just in case.

• Continue around the courtyard, then pass through the green 17 Queen’s Boudoir—where royal ladies hung out—and into the...

Of all the instruments made by the renowned Italian violin maker Antonius Stradivarius (1644-1737), only 300 survive. This is the world’s best collection and the only matching quartet set: two violins, a viola, and a cello. Charles III, a cultured man, fiddled around with these. Today, a single Stradivarius instrument might sell for $15 million.

• The next room (on the left) is the...

This room is kind of like the palace’s “crown jewels” sanctuary. It displays the precious objects related to the long tradition of crowning a new monarch. In the middle of the room is the scepter of the last Spanish king of the Habsburg family, Charles II, from the 17th century. Alongside is the stunning crown of Charles III, from the succeeding (and current) dynasty, the Bourbons. There’s a lion-footed chair, one of Charles III’s thrones. Nearby is a golden necklace of the Order of the Golden Fleece, an exclusive club of European royalty (to which all Spanish monarchs belong) that dates back to medieval times. Many of these venerable objects are brought out whenever a new monarch is proclaimed, but today’s constitutional monarchs don’t go through an elaborate coronation ceremony or don a crown.