Madrid’s most visit-worthy monastery was founded in the 16th century by Philip II’s sister, Joan of Habsburg (known to Spaniards as Juana and to Austrians as Joanna). She’s buried here. The monastery’s chapels are decorated with fine art, Rubens-designed tapestries, and the heirlooms of the wealthy women who joined the order (the nuns were required to give a dowry). Because this is still a working Franciscan monastery, tourists can enter only when the nuns vacate the cloister, and the number of daily visitors is limited. The scheduled tours often sell out, so buy your ticket right at 10:00 for morning tours or 16:00 for afternoon tours (advance tickets available online, but usually for Spanish-language tours only; check www.patrimonionacional.es).

Cost and Hours: €6, visits guided in Spanish or English depending on demand, Tue-Sat 10:00-14:00 & 16:00-18:30, Sun 10:00-15:00, closed Mon, last entry one hour before closing, Plaza de las Descalzas Reales 1, near the Ópera Metro stop and just a short walk from Puerta del Sol, +34 914 548 800.

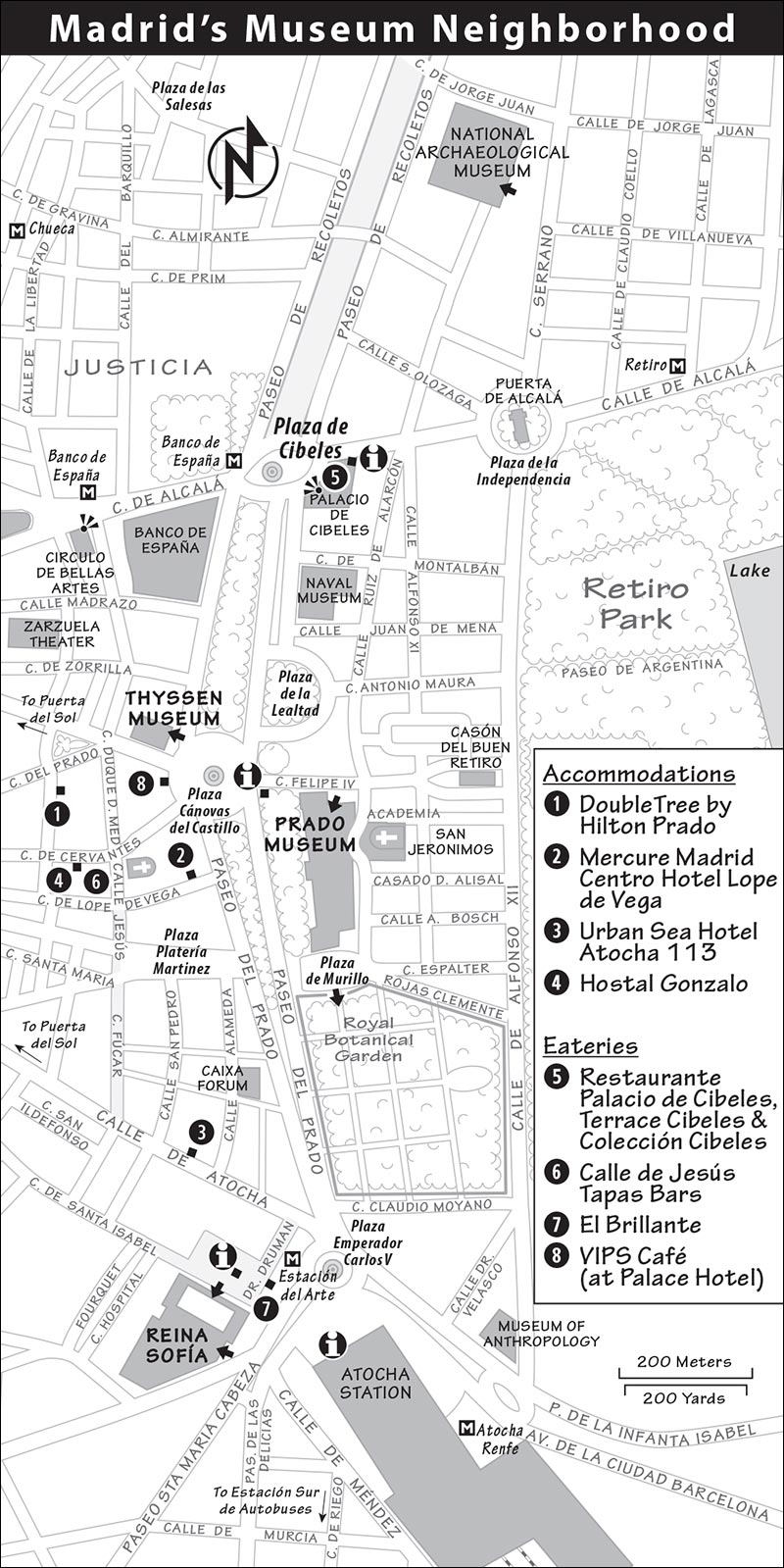

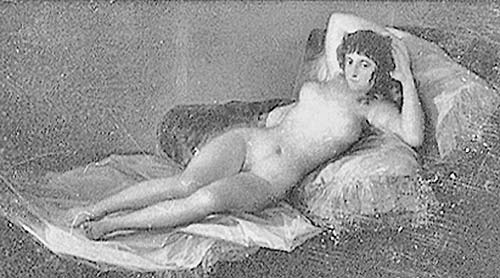

Three great museums, all within a 10-minute walk of one another, cluster in east Madrid. The Prado is Europe’s top collection of paintings. The Thyssen-Bornemisza sweeps through European art from old masters to moderns. And the Centro de Arte Reina Sofía has a choice selection of modern art, starring Picasso’s famous Guernica.

Combo-Ticket: If visiting all three museums, you can skip ticket lines and save a few euros with the Paseo del Arte combo-ticket (€31, sold at all three museums, good for a year).

Free Entry: The Prado is free to enter every evening, the Thyssen-Bornemisza’s permanent collection is free on Monday afternoons, and the Reina Sofía has free hours daily except Tuesday (when it’s closed).

With more than 3,000 canvases, including entire rooms of masterpieces by superstar painters, the Prado (PRAH-doh) is my vote for the greatest collection anywhere of paintings by the European masters. Centuries of powerful Spanish kings (and lots of New World gold) funded art from all across Europe, so you’ll see first-class works from the Italian Renaissance (Raphael, Titian) as well as Northern art (Rubens, Dürer, and Bosch’s fantastical Garden of Earthly Delights). Mainly, the Prado is the place to enjoy the holy trinity of Spanish painters—El Greco, Velázquez, and Goya—including Velázquez’s Las Meninas, considered by many to be the world’s finest painting, period. Because the Prado is so huge, my tour zeroes in on a “Top Ten” list of only the very best stops. Allow at least two hours to speed through these highlights—but many spend three hours or more.

Cost and Hours: €15/1 day, €22/2 days, additional (obligatory) fee for occasional temporary exhibits, free Mon-Sat 18:00-20:00 and Sun 17:00-19:00, temporary exhibits discounted during free hours, under age 18 always free; open Mon-Sat 10:00-20:00, Sun until 19:00.

Information: +34 913 302 800, www.museodelprado.es.

Crowd-Beating Tips: The only place to buy tickets on-site is the ground level of the Goya Entrance, where ticket-buying lines can be long. To save time, buy your ticket online in advance (€0.50/ticket fee, ticket good all day, same-day tickets may be available—if the ticket line is long, try purchasing from your phone). You’ll receive an email with a voucher which you’ll then need to exchange for a paper ticket at the Goya Entrance (use shorter online-ticket line), then join the line for security at the Jerónimos Entrance.

Those with a Paseo del Arte combo-ticket (described earlier) must also exchange their voucher for a ticket at the Goya Entrance, then line up at the Jerónimos Entrance. To save time, buy the Paseo del Arte online or at the less-crowded Thyssen-Bornemisza or Reina Sofía museums.

The Prado is generally less crowded at lunchtime (13:00-16:00) and on weekdays. It’s busiest on free evenings and weekends. Big spenders can pay €50 for a one-day ticket that allows entry one hour before the museum officially opens.

Getting There: It’s on Paseo del Prado. The nearest Metro stops are Banco de España (line 2) and Estación del Arte (line 1), each a 10-minute walk from the museum.

It’s a 15-minute walk from Puerta del Sol on traffic-and-pickpockets-clogged Carrera de San Jerónimo. For a more pleasant approach (which takes a few minutes longer), use your map to follow this route: From Puerta del Sol, head south to Plaza de Jacinto Benavente, then a block east, to Plaza del Ángel. From here, Calle de Las Huertas (with limited traffic) leads characteristically to Paseo del Prado, between the main Jerónimos Entrance and the Reina Sofía.

Getting In: The Jerónimos Entrance, where our tour begins, is the main entry (with all services except ticket sales/voucher exchange). It’s tucked around behind the north end of the building (to the left, as you face the Prado from the main road).

The nearby Goya Entrance, also at the north end of the building, has the ticket office—go here first to exchange your voucher or buy a ticket.

The Murillo Entrance (south/right end of the building, as you face it) is mostly for student groups. All entrances have airport-type security checkpoints. The Velázquez Entrance—in the middle of the building—is typically closed to the public.

Tours: The audioguide is a helpful supplement to my self-guided tour, allowing you to wander and dial up commentary on 250 masterpieces as you come across them (€4-6 depending on if there’s a temporary exhibit). Skip the Prado’s Second Canvas app.

Services: The Jerónimos Entrance has an information desk, bag check, audioguides, bookshop, WCs, and café. Larger bags must be checked.

No-no’s: No photos, drinks, food, backpacks, or large umbrellas are allowed inside.

Cuisine Art: The museum’s self-service $ cafeteria/restaurant is just inside the Jerónimos Entrance (Mon-Sat 10:00-19:30, Sun until 18:30, hot dishes served only 12:30-16:00). Across the street from the Goya Entrance, you’ll find $$ VIPS, a popular but characterless chain restaurant, handy for a cheap and filling salad or sandwich, with some outdoor tables facing the Neptune fountain (daily 9:00-24:00, across the boulevard from northern end of Prado at Plaza de Canova del Castillo, under Palace Hotel). Next door is Spain’s first Starbucks, opened in 2001. A strip of wonderful $$ tapas bars is just a few blocks west of the museum, lining Calle de Jésús (see here). If you plan to reenter the museum, get your ticket stamped at the desk marked “Educación” near the Jerónimos Entrance before you leave for lunch.

Self-Guided Tour

Self-Guided TourThanks to Gene Openshaw for writing the following tour.

The vast Prado Museum sprawls over four floors. This tour is designed to hit the highlights with a minimum of walking and in a (roughly) chronological way. We’ll see altarpieces of early religious art, the rise of realism in the Renaissance, the royal art of Spain’s Golden Age, and the slow decline of Spain—bringing us right up to the cusp of the modern world.

Paintings are moved around frequently, and rooms may be renumbered—if you can’t find a particular work, ask a guard or at information desks.

• Enter at the Jerónimos Entrance. Pick up a museum map—you’ll need it. Locate where you are on the map—on Level 0, at the Jerónimos Entrance. Our first stop should be nearby, in Room 56A.

To get there, find the corridor (near the security checkpoint) to the Edificio Villanueva. Head down the corridor about 30 yards and turn right into Room 55, then immediately right again (into 55A), then left into Room 56A. Let’s kick off this tour of artistic delights with a large three-panel painting of The Garden of Earthly Delights.

In his cryptic triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights (El Jardín de las Delicias, c. 1505), the early Flemish painter Bosch (c. 1450-1516) paints a wonderland of eye-pleasing details. The message is that the pleasures of life are fleeting, and we’d better avoid them or we’ll wind up in hell. Take your time here to unpack this dense masterpiece.

This altarpiece has a central scene and two hinged outer panels. All the images work together to teach a religious message. Imagine the altarpiece closed (showing the back side). The world is gray and bare, before God’s creation. Now open it up, bring on the people, and splash into this colorful Garden of Earthly Delights.

The left panel is Paradise, showing naked Adam and Eve before original sin. Everything is in its place, with animals behaving virtuously. Innocent Adam and Eve get married, with God himself performing the ceremony.

The central panel is a riot of naked men and women, black and white, on a perpetual spring break—eating exotic fruits, dancing, kissing, cavorting with strange animals, and contorting themselves into a Kama Sutra of sensual positions. In the background rise the fantastical towers of a medieval Disneyland. It’s seemingly a wonderland of pleasures and earthly delights. But where does it all lead? Men on horseback ride round and round, searching for but never reaching the elusive Fountain of Youth. Humankind frolics in earth’s “Garden,” oblivious to where they came from (left) and where they may end up...

Now, go to hell (right panel). It’s a burning Dante’s Inferno-inspired wasteland where genetic-mutant demons torture sinners. Everyone gets their just desserts, like the glutton who is eaten and re-eaten eternally, the musician strung up on his own harp, and the gamblers with their table forever overturned. In the center, hell is literally frozen over. A creature with a broken eggshell body hosting a tavern, tree-trunk legs, and a hat featuring a bagpipe (symbolic of hedonism) stares out—it’s the face of Bosch himself.

If you want more Bosch, check out the nearby table featuring his Seven Deadly Sins (Los Pecados Capitales, late 15th century). Each of the four corners has a theme: death, judgment, paradise, and hell. The fascinating wheel, with Christ in the center, names the sins in Latin (lust, envy, gluttony, and so on), and illustrates each with a vivid scene that works as a slice of 15th-century Dutch life.

Nearby, another Bosch triptych, The Haywain (El Carro de Heno, c. 1516), has still more vivid imagery about the consequences of sin and the transience of earthly life.

• The clock is ticking to see the rest of this museum’s delights, so let’s move on. We’re going to the source of European painting as we know it: the Italian Renaissance.

Backtrack the way you came. Reaching the corridor, turn right and go past the elevators (remember them—we’ll use the elevators later). About 30 yards along, turn right into Room 49—a large, long, sage-green hall labeled XLIX above the door you’ve just entered. You’ve reached...

During its Golden Age (the 1500s), Spain may have been Europe’s richest country, but Italy was still the most cultured. Spain’s kings loved how Italian Renaissance artists captured a three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional canvas, bringing Bible scenes to life and celebrating real people and their emotions.

• Start midway down Room 49, on the right-hand wall, with a guy in red painted by Raphael.

Raphael (1483-1520) was the undisputed master of realism. When he painted Portrait of a Cardinal (El Cardenal, c. 1510-11), he showed the sly Vatican functionary with a day’s growth of beard and an air of superiority, locking eyes with the viewer. The cardinal’s slightly turned torso is as big as a statue. Nearby are several versions of Holy Family and other paintings by Raphael.

• Now climb the four stairs in the middle of the room, up to Room 56B.

Fra Angelico’s The Annunciation (La Anunciación, c. 1426) is half medieval piety, half Renaissance realism. In the crude Garden of Eden scene (on the left), a scrawny, sinful First Couple hovers unrealistically above the foliage, awaiting eviction. The angel’s Annunciation to Mary (right side) is more Renaissance, both with its upbeat message (that Jesus will be born to redeem sinners like Adam and Eve) and in the budding photorealism, set beneath 3-D arches. (Still, aren’t the receding bars of the porch’s ceiling a bit off? Painting three dimensions wasn’t that easy.)

Also in Room 56B, the tiny Dormition of the Virgin (El Tránsito de la Virgen), by Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431-1506), shows his mastery of Renaissance perspective. The apostles crowd into the room to mourn the last moments of the Virgin Mary’s life. The receding floor tiles and open window in the back create the subconscious effect of Mary’s soul finding its way out into the serene distance.

• To see how the Italian Renaissance spread to northern lands, step into the adjoining Room 55B (to the left, as you face the main hall).

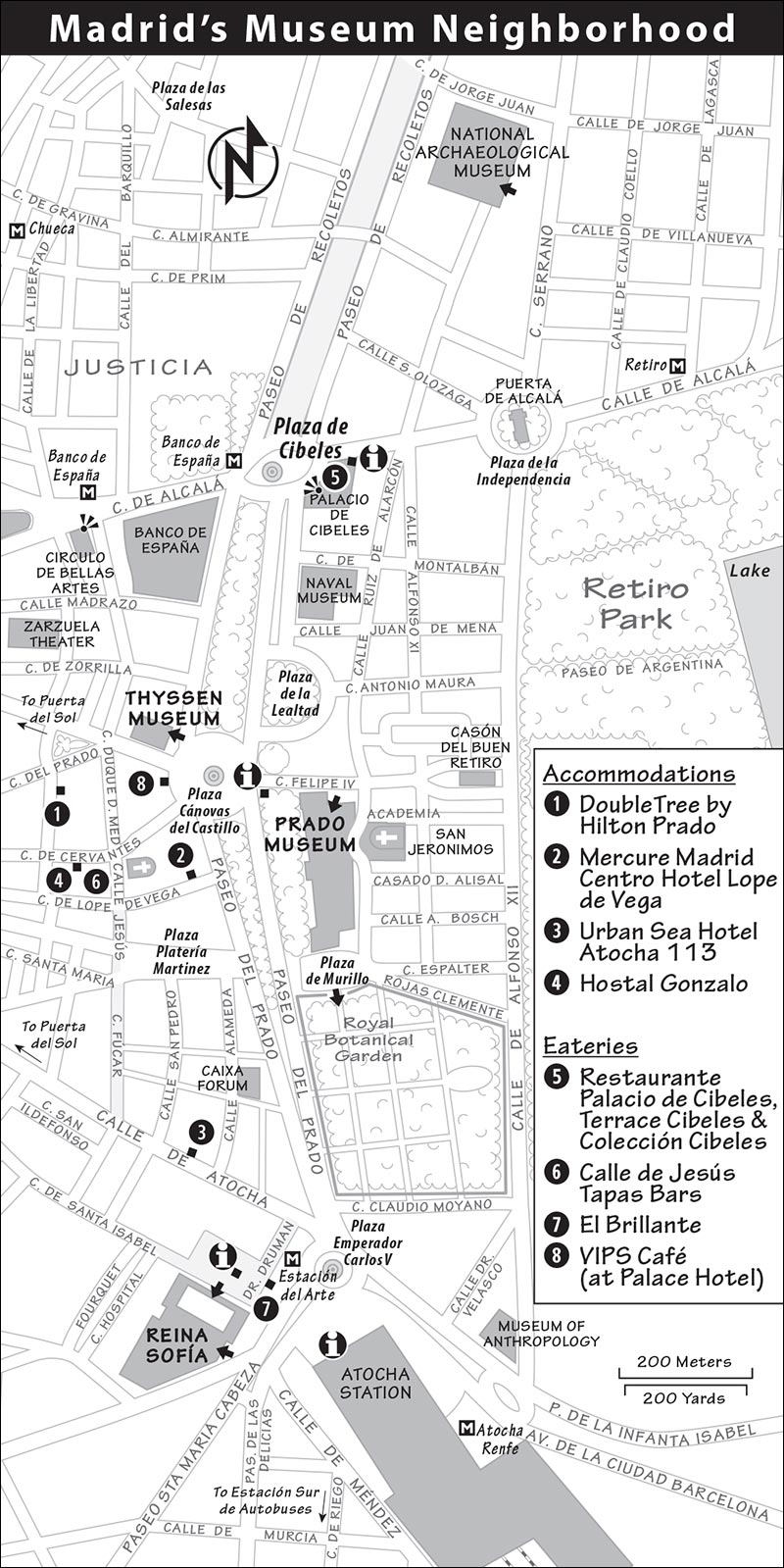

Albrecht Dürer’s Self-Portrait (Autorretrato), from 1498, is possibly the first time an artist depicted himself. The artist, age 26, is German, but he’s all dolled up in a fancy Italian hat and permed hair. He’d recently returned from Italy and wanted to impress his countrymen with his sophistication. Dürer (1471-1528) wasn’t simply vain. He’d grown accustomed, as an artist in Renaissance Italy, to being treated like a prince. Note Dürer’s signature, the pyramid-shaped “A. D.” (D inside the A), on the windowsill.

Nearby are Dürer’s 1507 panel paintings of Adam and Eve—the first full-size nudes in Northern European art. Like Greek statues, they pose in their separate niches, with three-dimensional, anatomically correct bodies. This was a bold humanist proclamation that the body is good, man is good, and the things of the world are good.

• The down-to-earth realism of Renaissance art soon spread to Europe’s richest country—Spain.

Backtrack down the four steps into Room 49, and make a U-turn to the left, to reach those elevators we saw earlier. Take the elevator up to level 1, and turn left into Room 11. A painting here (by Velázquez) of a radiant Apollo surprising the cuckold Vulcan and a gang of startled workmen introduces us to the main feature of Spanish art—unflinching realism.

Let’s begin next door, in the large, lozenge-shaped Room 12.

Diego Velázquez (vel-LAHTH-keth, 1599-1660) was the photojournalist of court painters, capturing the Spanish king and his court in formal portraits that take on aspects of a candid snapshot. Room 12 is filled with the portraits Velázquez was called on to produce. Kings and princes prance like Roman emperors. Get up close and notice that his remarkably detailed costumes are nothing but a few messy splotches of paint—the proto-Impressionism Velázquez helped pioneer.

The room’s centerpiece, and perhaps the most important painting in the museum, is Velázquez’s Maids of Honor (Las Meninas, c. 1656). It’s a peek at nannies caring for Princess Margarita and, at the same time, a behind-the-scenes look at Velázquez at work. One hot summer day in 1656, Velázquez (at left, with paintbrush and Dalí moustache) stands at his easel and stares out at the people he’s painting—the king and queen. They would have been standing about where we are, and we see only their reflection in the mirror at the back of the room. Their daughter (blonde hair, in center) watches her parents being painted, joined by her servants (meninas), dwarves, and the family dog. At that very moment, a man happens to pass by the doorway at back and pauses to look in. Why’s he there? Probably just to give the painting more depth.

This frozen moment is lit by the window on the right, splitting the room into bright and shaded planes that recede into the distance. The main characters look right at us, making us part of the scene, seemingly able to walk around, behind, and among the characters. Notice the exquisitely painted mastiff—annoyed by the little girl, but staying put...for now.

If you stand in the center of the room, the 3-D effect is most striking. This is art come to life.

• Let’s see more of Velázquez, whose work covers a wide range of subjects and emotions. Facing this painting, leave to the left, pass through Room 11, and enter Room 10.

Velázquez enjoyed capturing light—and capturing the moment. The Feast of Bacchus (Los Borrachos, c. 1628-29) is a group selfie in a blue-collar bar. A couple of peasants mug for a photo-op with a Greek god—Bacchus, the god of wine. This was an early work, before Velázquez got his court-painter gig, and shows off his admiration for “real” people. Hardworking farmers enjoying the fruit of their labor deserved portraits, too. Notice the almost-sacramental presence of the ultrarealistic bowl of wine in the center, as Bacchus, with the honest gut, crowns a fellow hedonist.

• Backtrack through the big gallery with Las Meninas, and continue straight ahead into Room 14.

Velázquez’s boss, King Philip IV, had an affair, got caught, and repented by commissioning The Crucified Christ (Cristo Crucificado, c. 1632). Christ hangs his head, humbly accepting his punishment. Philip would have been left to stare at the slowly dripping blood, contemplating how long Christ had to suffer to atone for Philip’s sins. This is an interesting death scene. There’s no anguish, no tension, no torture. Light seems to emanate from Jesus as if nothing else matters. The crown of thorns and the cloth wrapped around his waist are particularly vivid. Above it all, a sign reads in three languages: “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.”

• Continue on through Room 15 (with Velázquez’s insightful portraits of the royal court dwarves) and detour into Rooms 16 and 17.

Take a moment to appreciate these paintings by one of Velázquez’s admirers: Bartolomé Murillo. Murillo (1618-1682) soaked up Velazquez’s unflinching photorealism, but added a spoonful of sugar. In his most famous works—called The Immaculate Conception—Murillo put a human face on the abstract Catholic doctrine that Mary was conceived and born free of original sin. His “immaculate” virgins float in a cloud of Ivory Soap cleanliness, radiating youth and wholesome goodness. Mary wears her usual colors—white for purity and blue for divinity. (For more on Murillo, see here.) Murillo’s sweet and escapist work must have been very comforting to the wretched people of his hometown of Sevilla, which was ravaged by plague in 1647-1652.

• Backtrack to the Meninas room (12) and turn left. You’ll exit into the museum’s looooong grand gallery (Rooms 25-29) and come face-to-face with a large canvas of a knight on horseback.

Spain’s Golden Age kings Charles V and Philip II both hired Europe’s premier painter—Titian the Venetian (c. 1485-1576)—to paint their portraits.

In The Emperor Charles V at Mühlberg (Carlos V en la Batalla de Mühlberg, 1548), the king rears on his horse, points his lance at a jaunty angle, and rides out to crush an army of Lutherans. Charles, having inherited many kingdoms and baronies through his family connections, was the world’s most powerful man in the 1500s. (You can see the suit of armor depicted in the painting in the Royal Palace.)

In contrast (just to the right), Charles I’s son, Philip II (Felipe II, c. 1550-1551), looks pale, suspicious, and lonely—a scholarly and complex figure. He moved Spain’s capital from Toledo to Madrid and built the austere, monastic palace at El Escorial. These are the faces of the Counter-Reformation, as Spain took the lead in battling Protestants. Both father and son had one thing in common: underbites, a product of royal inbreeding (which Titian painted...delicately).

• The ultra-Catholic Philip II amassed a surprisingly large collection of Titian’s Renaissance playmates, which you could seek out elsewhere on this floor. But let’s turn to a quite different painter that Philip hired—El Greco.

Facing Charles and Philip, turn right, walk about 30 yards, and turn right at the first door, into Room 9B.

El Greco (1541-1614) was born in Greece (his name is Spanish for “The Greek”), trained in Venice, then settled in Toledo—60 miles from Madrid. His paintings are like Byzantine icons drenched in Venetian color and fused in the fires of Spanish mysticism. (For more on El Greco, see here.) The El Greco paintings displayed here rotate, but they all glow with his unique style.

In Christ Carrying the Cross (Cristo Abrazado a la Cruz, c. 1602), Jesus accepts his fate, trudging toward death with blood running down his neck. He hugs the cross and directs his gaze along the crossbar. His upturned eyes (sparkling with a streak of white paint) lock onto his next stop—heaven.

The Adoration of the Shepherds (La Adoración de los Pastores, c. 1614—likely next door in room 10B), originally painted for El Greco’s own burial chapel in Toledo, has the artist’s typical two-tiered composition—heaven above, earth below. The long, skinny shepherds are stretched unnaturally in between, flickering like flames toward heaven.

El Greco’s portraits of Spanish nobles and saints (such as The Nobleman with His Hand on His Chest, El Caballero de la Mano al Pecho, c. 1580) focus on their aristocratic expressions. A man’s hand with his fingers splayed out, but with the middle fingers touching, was El Greco’s trademark way of expressing elegance (or was it the 16th-century symbol for “Live long and prosper”?). Several paintings have El Greco’s signature written in faint Greek letters—“Doménikos Theotokópoulos,” El Greco’s real name.

• While El Greco was painting austere Christian saints, other European artists were painting sensual Greek gods, in a dramatic new style—Baroque.

Return to the main gallery, turn left, pass by Charles and Philip again, and proceed to the gallery’s far end (technically Rooms 28 and 29) for the large, colorful, fleshy canvases by...

A native of Flanders, Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) painted Baroque-style art meant to play on the emotions, titillate the senses, and carry you away. His paintings surge with Baroque energy and ripple with waves of figures. Surveying his big, boisterous canvases, you’ll notice his trademarks: sex, violence, action, emotion, bright colors, and ample bodies, with the wind machine set on full. Gods are melodramatic, and nymphs flee half-human predators. Rubens painted the most beautiful women of his day—well-fed, no tan lines, squirt-gun breasts, and very sexy.

Rubens’ The Three Graces (Las Tres Gracias, c. 1630-1635) celebrates cellulite. The ample, glowing bodies intertwine as the women exchange meaningful glances. The Grace at the left is Rubens’ young second wife, Hélène Fourment, who shows up regularly in his paintings.

• Rubens, El Greco, Titian, and Velázquez had all made their living working for Europe’s royalty. But that world was changing, and revolution was in the air. No painter illustrates the changing times more than our final artist—Goya.

From Rubens, continue to the end of the long main gallery and enter the round Room 32, where you’ll see royal portraits by Goya.

Follow the complex Francisco de Goya (1746-1828) through the stages of his life—from dutiful court painter, to political rebel and scandal maker, to the disillusioned genius of his “black paintings.” The museum’s exciting Goya collection is displayed on three different levels: classic Goya on this level; early cartoons upstairs; and his dark and political work downstairs.

In the group portrait The Family of Charles IV (La Familia de Carlos IV, 1800), the royals are all decked out in their Sunday best. Goya himself stands at his easel to the far left, painting the court (a tribute to Velázquez in Las Meninas) and revealing the shallowness beneath the fancy trappings. Charles, with his ridiculous hairpiece and goofy smile, was a vacuous, henpecked husband. His toothless yet domineering queen upstages him, arrogantly stretching her swanlike neck. The other adults, with their bland faces, are bug-eyed with stupidity.

Surrounding you in this same room are other portraits of the king and queen. Also notice the sketch paintings, quick studies done with the subjects posing for Goya. He used these for reference to complete his larger, more finished canvases.

• Exit to the right across a small hallway and turn left to find Room 36, where you’ll find Goya’s most scandalous work.

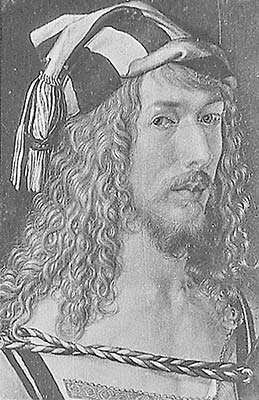

Rumors flew that Goya was fooling around with the vivacious Duchess of Alba, who may have been the model for two similar paintings, Nude Maja (La Maja Desnuda, c. 1800) and Clothed Maja (La Maja Vestida, c. 1808). A maja was a trendy, working-class girl. Whether she’s a duchess or a maja, Goya painted a naked lady—an actual person rather than some mythic Venus. And that was enough to risk incurring the wrath of the Inquisition. The nude stretches in a Titian-esque pose to display her charms, the pale body with realistic pubic hair highlighted by cool green sheets. (Notice the artist’s skillful rendering of the transparent fabric on the pillow.) According to a believable legend, the two paintings were displayed in a double frame, with the Clothed Maja sliding over the front to hide the Nude Maja from Inquisitive minds.

• Just off the next room, you’ll find an elevator and a staircase (farther down the hall). Use one of them to head up to level 2, to Rooms 85-87 and 90-94, for more Goya.

These rooms display Goya’s designs for tapestries (known as “cartoons”) for nobles’ palaces. Dressed in their gay “Goya-style” attire, nobles picnic, dance, fly kites, play paddleball and Blind Man’s Bluff, or just relax in the sun—as in the well-known The Parasol (El Quitasol, Room 86). It’s clear that, while revolution was brewing in America and France, Spain’s lords and ladies were playing, blissfully ignorant of the changing times.

• Goya’s later paintings took on a darker edge. For more Goya, take the stairs or elevator down to level 0, then go up and down the stairs (across the Murillo Entrance) to Room 66. Entering, start to the left, in Room 65, with powerful military scenes.

Despite working for Spain’s monarchs, Goya became a political liberal and a champion of the Revolution in France. But that idealism was soon crushed when the supposed hero of the Revolution, Napoleon, morphed into a tyrant and invaded Spain. Goya, who lived on Madrid’s Puerta del Sol, captured the chaotic events that unfolded there.

In The Second of May, 1808 (El 2 de Mayo de 1808, 1814), Madrid’s citizens rise up to protest the occupation in Puerta del Sol, and the French send in their dreaded Egyptian mercenaries. They plow through the dense tangle of Madrileños, who have nowhere to run. The next day, The Third of May, 1808 (El 3 de Mayo de 1808, 1814), the French rounded up ringleaders and executed them. The colorless firing squad—a faceless machine of death—mows them down, and they fall in bloody, tangled heaps. Goya throws a harsh prison-yard floodlight on the main victim, who spreads his arms Christ-like to ask, “Why?”

Politically, Goya was split—he was a Spaniard, but he knew France was leading Europe into the modern age. His art, while political, has no Spanish or French flags. It’s a universal comment on the horror of war. Many consider Goya the last classical and first modern painter...the first painter with a social conscience.

• Finish the tour with Goya’s final, late-in-life paintings. Turn about-face to the “black paintings” in Room 67.

Depressed and deaf from syphilis, Goya retired to his small home and smeared its walls with his “black paintings”—dark in color and in mood. During this period in his life, Goya would paint his nightmares...literally. The style is considered Romantic—emphasizing emotion over beauty—but it foreshadows 20th-century Surrealism with its bizarre imagery, expressionistic and thick brushstrokes, and cynical outlook.

Stepping into Room 67, you are surrounded by art from Goya’s dark period. These paintings are the actual murals from the walls of his house, transferred onto canvas. Imagine this in your living room. Goya painted what he felt with a radical technique unburdened by reality—a century before his time. And he painted without being paid for it—perhaps the first great paintings done not for hire or for sale. We know frustratingly little about these works because Goya wrote nothing about them.

Dark forces convened continually in Goya’s dining room, where The Great He-Goat (El Aquelarre/El Gran Cabrón, c. 1820-1823) hung. The witches, who look like skeletons, swirl in a frenzy around a dark, Satanic goat in monk’s clothing who presides over the obscene rituals. The black goat represents the devil and stokes the frenzy of his wild-eyed subjects. Amid this adoration and lust, a noble lady (far right) folds her hands primly in her lap (“I thought this was a Tupperware party!”). Or, perhaps it’s a pep rally for her execution, maybe inspired by the chaos that accompanied Plaza Mayor executions. Nobody knows for sure.

In Fight to the Death with Clubs (Duelo a Garrotazos, c. 1820-1823), two giants stand face-to-face, buried up to their knees, and flail at each other with clubs. It’s a standoff between superpowers in the never-ending cycle of war.

In Saturn (Saturno, c. 1820-1823), fearful that his progeny would overthrow him, the god eats one of his offspring. Saturn, also known as Kronus (Chronus, or time), may symbolize how time devours us all. Either way, the painting brings new meaning to the term “child’s portion.”

The Drowning Dog (Perro Semihundido, c. 1820-1823) is, according to some, the hinge between classical art and modern art. The dog, so full of feeling and sadness, is being swallowed by quicksand...much as, to Goya, the modern age was overtaking a more classical era. And look closely at the dog. It also can be seen as a turning point for Goya. Perhaps he’s bottomed out—he’s been overwhelmed by depression, but his spirit has survived. With the portrait of this dog, color is returning.

• Keep that hope alive for one more painting. Head back to Room 65 or 66, and look to your right.

The last painting we have by Goya is The Milkmaid of Bordeaux (La Lechera de Burdeos, c. 1827). Somehow, Goya pulled out of his depression and moved to France, where he lived until his death at 82. While painting as an old man, color returned to his palette. His social commentary, his passion for painting what he felt (more than what he was hired to do), and, as you see here, the freedom of his brushstrokes explain why many consider Francesco de Goya to be the first modern artist.

• There’s a lot more to the Prado, but there’s also a lot more to Madrid. For a nature break from all this art, exit through the Murillo Entrance and you’ll run right into the delightful Royal Botanical Garden, described next.

After your Prado visit, you can take a lush and fragrant break in this sculpted park. Wander among trees from around the world, originally gathered by—who else?—the enlightened King Charles III. This garden was established when the Prado’s building housed the natural science museum. A flier in English explains that this is actually more than a park—it’s a museum of plants.

Cost and Hours: €4, daily May-Aug 10:00-21:00, April and Sept until 20:00, shorter hours off-season, entrance opposite the Prado’s Murillo/south entry, Plaza de Murillo 2, +34 914 203 017.

Locals call this stunning museum simply the Thyssen (TEE-sun). It displays the impressive collection that Baron Thyssen (a wealthy German married to a former Miss Spain) sold to Spain for $350 million. The museum offers a unique chance to enjoy the sweep of all of art history—including a good sampling of the “isms” of the 20th century—in one collection. It’s basically minor works by major artists and major works by minor artists. (Major works by major artists are in the Prado.) But art lovers appreciate how the good baron’s art complements the Prado’s collection by filling in where the Prado is weak—such as Impressionism, which is the Thyssen’s forte.

Cost and Hours: €13, includes temporary exhibits, timed ticket required for temporary exhibits, free on Mon; permanent collection open Mon 12:00-16:00, Tue-Sun 10:00-19:00; temporary exhibits open Sat until 21:00; audioguide-€5 for permanent collection, €4 for temporary exhibits, €7 for both; Second Canvas Thyssen is a decent free app that explains major works—use museum’s free Wi-Fi to access; +34 917 911 370, www.museothyssen.org.

Getting There: It’s located kitty-corner from the Prado at Paseo del Prado 8 in Palacio de Villahermosa (Metro: Banco de España).

Services: The museum has free baggage storage (bags must fit through a small x-ray machine), a cafeteria and restaurant, and a shop/bookstore.

Connecting the Thyssen and Reina Sofía: It’s about a 20-minute, slightly downhill walk. You can hail a cab at the gate to zip straight there. Or take bus #27: Catch it in the square with the Neptune fountain in front of the Starbucks, ride to the end of Paseo del Prado, get off at the McDonald’s, and cross the street (going away from the Royal Botanical Garden) to reach Plaza Sánchez Bustillo and the museum.

Self-Guided Tour

Self-Guided TourAfter purchasing your ticket, continue down the wide main hall past larger-than-life paintings of former monarchs Juan Carlos I and Sofía, and at the end of the hall, paintings of the baron (who died in 2002) and his art-collecting baroness, Carmen. At the info desk, pick up a museum map.

Each of the three floors is divided into two separate areas: the permanent collection (numbered rooms) and additions from baroness Carmen since the 1980s (lettered rooms). The permanent collection has the heavyweight artists, though Carmen’s wing is also intriguing. Ascend to the top floor and work your way down, taking a delightful walk through art history. Visit the rooms on each floor in numerical order, from Primitive Italian (Room 1) to Surrealism and Pop Art (Rooms 45-48). Here’s a breezy stroll that hits the highlights:

Level 2: Start where Western art did—with religious altarpieces from Italy depicting holy people in the golden realm of heaven (Rooms 1-2). Meanwhile, Flemish painters were discovering oil paints, allowing them to give their Virgin Marys more detail and human tenderness (Room 3). The Italians pioneered 3-D realism, to bring heavenly scenes down into the real world (Room 4).

Turn the corner into the long hallway, featuring portraits of famous Europeans circa 1500, including King Henry VIII (Rooms 5-6). Pop into Room 11 for a few fine El Grecos. In Room 13, turn the corner into Rooms 14-18. It’s the 1600s, a time of very forgettable canvases, except for Canaletto’s views of Venice (Room 16).

• At Room 18, turn left.

Portraits by Rubens (Room 19) and a proud self-portrait by Rembrandt (Room 21) stand out.

• Go downstairs to...

Level 1: While Italians painted myths and goddesses, the practical Dutch enjoyed down-to-earth portraits, group portraits, everyday scenes, landscapes, seascapes, and detailed still-lifes of fruit and flowers (Rooms 22-26).

• Turn the corner into Room 28.

In the 1700s, France dominated Europe, with its porcelain-skinned aristocrats and their Rococo fashions. In art, the French pioneered the march toward modernism (Rooms 29-31). Artists painted in the open air to capture rural landscapes and the working poor with increasing spontaneity.

• Continue to Rooms 32-33, where the movement culminated in Impressionism.

The museum has a laudable collection of works by Manet, Monet, and their Impressionist contemporaries, who painted landscapes, Parisian street scenes, a night at the ballet with Degas, or Toulouse-Lautrec’s backstage scenes of the Moulin Rouge.

• Turn the corner as Impressionism becomes Post-Impressionism (Rooms 34-37).

Note the variety of painters who used Impressionist techniques but with brighter colors, thicker paint, and more furious brushwork. Increasingly, they simplified reality and flattened the 3-D, pointing the way to 20th-century art.

• In Room 37, turn left.

As a new century dawned, artists like Kandinsky stopped painting reality altogether and began creating beautiful patterns of pure line and color arranged in pleasing patterns—abstract art (Rooms 37-38). As World War I shattered societal norms, and fascism was on the rise, Expressionist artists expressed their fears in lurid colors and grim scenes (Rooms 39-40).

• Go downstairs to...

Level 0: The Spaniard Picasso and his Parisian roommate Georges Braque invented Cubism—a revolutionary new style many others would imitate (Rooms 41-42). As artists increasingly turned away from photorealism, Cubism reached its textbook example of purely abstract art with Mondrian’s simple rectangular grids of the primary colors—red, yellow, blue—on a white canvas (Room 43).

• Turn the corner into Room 44.

Cubists explored collage, literally gluing things onto the canvas to make it a kind of sculpture. See the many varieties of Cubism and other “isms,” including Picasso—the master of many styles (Room 45). Marc Chagall used modern art techniques to create a dreamlike world of weightless lovers and fiddler-on-the-roof villages. Moving into Room 46, see how World War II shifted the art world to America, where artists “expressed” their emotions in big, minimal “abstract” canvases—Abstract Expressionism. Francis Bacon captured the horror of World War II’s destruction with his screaming, caged, isolated figures in a barren landscape (Room 47). In Room 48, see how America’s 1960s prosperity elevated the elements of everyday pop culture to the level of art, including Roy Liechtenstein’s iconic scenes of comic books blown up to ridiculous proportions and presented as masterpieces.

• Whew. That’s five centuries of Western Art. Now you’re ready for Madrid’s museum of modern art, the Reina Sofía.

Home to Picasso’s Guernica, the Reina Sofía is one of Europe’s most enjoyable modern-art museums. Its exceptional collection of 20th-century art is housed in what was Madrid’s first public hospital. The focus is on 20th-century Spanish artists—Picasso, Dalí, Miró, and Gris—but you’ll also find works by Kandinsky, Braque, Magritte, and other giants of modern art. Many works are displayed alongside continuously running films that place the art into social context. Those with an appetite for modern and contemporary art can spend several delightful hours in this museum.

Cost and Hours: €10 (includes most temporary exhibits); open Mon and Wed-Sat 10:00-21:00, Sun until 19:00 (fourth floor not accessible Sun after 15:00), closed Tue.

Free Entry: The museum is free—and often crowded—Mon and Wed-Sat 19:00-21:00 and Sun 13:30-19:00 (must pick up a ticket to enter).

Information: +34 917 741 000, www.museoreinasofia.es.

Getting There: It’s a block from the Estación del Arte Metro stop, on Plaza Sánchez Bustillo at Calle de Santa Isabel 52. In the Metro station, follow signs for the Reina Sofía exit. Emerging from the Metro, walk straight ahead a half-block and turn right on Calle de Santa Isabel. You’ll see the tall, exterior glass elevators that flank the museum’s main entrance.

A second entrance in the newer section of the building sometimes has shorter lines, especially during the museum’s free hours. To get there, face the glass elevators and walk left around the old building to the large gates of the red-and-black Nouvel Building.

Tours: The hardworking audioguide is €5.50.

Services: Bag storage is free. The librería just outside the Nouvel wing has a larger selection of Picasso and Surrealist reproductions than the main gift shop at the entrance.

Cuisine Art: The museum’s $$ café (a long block around the left from the main entrance) is a standout for its tasty cuisine. The square immediately in front of the museum is ringed by fine places for a simple meal or drink. My favorite is $$ El Brillante, a classic dive offering pricey tapas and baguette sandwiches. But everyone comes for the fried squid sandwiches. Sit at the simple bar or at an outdoor table (long hours daily, two entrances—one on Plaza Sánchez Bustillo, the other at Plaza del Emperador Carlos V 8, see the “Madrid’s Museum Neighborhood” map earlier in this chapter, +34 915 286 966). And just a 10-minute walk north is my favorite strip of tapas bars, on Calle de Jesús (see here).

Self-Guided Tour

Self-Guided TourThe permanent collection is divided into three groups: art from 1900 to 1945 (second floor, including Guernica), art from 1945 to 1968 (fourth floor), and art from 1962 to 1982 (adjoining Nouvel wing). Temporary exhibits are scattered throughout. While the collection is roughly chronological, it’s displayed thematically, with each room clearly labeled with its theme.

For a good first visit, ride the fancy glass elevator to level 2 and tour that floor counterclockwise (Modernism, Cubism, Picasso’s Guernica, Surrealism), then see post-WWII art on level 4, and finally descend to the Nouvel wing for the finale.

• Pick up a free map and take an elevator (slow, hot, and crowded, so be patient) to level 2. Begin in Room 201—located between the two elevators—which introduces you to the dawn of the 20th century.

You could make a good case that the changes in society in the year 1900 were more profound than those we lived through in 2000. Trains and cars brought speed to life. Electricity brought light. Revolutions were toppling centuries-old regimes. Einstein introduced mind-bending ideas. Photography captured reality, and movies set it in motion. The 20th century—accelerated by technology and shattered by war—would produce the exciting and turbulent modern art showcased in this museum.

The collection kicks off with engravings by the 19th-century artist Goya, often considered the first “modern” painter (and the Reina Sofía’s one point of overlap with the Prado). He used art to express his inner feelings and address social injustice, and his dynamic style anticipated the formless chaos of Modern Art.

You may also see early works by young Pablo Picasso—a precocious teenager who skipped his art classes to sketch works by Goya, Velázquez, and El Greco in the Prado. In the year 1900, 19-year-old Picasso moved to the world’s art capital, Paris, where the Modern Art revolution was about to begin.

• We’ll tour this floor counterclockwise (in reverse order to how the rooms are numbered). Start in Room 210.

In Paris, Picasso and his roommate Georges Braque invented a new way of portraying the world on a canvas—Cubism. They shattered the world into a million pieces, then reassembled the shards and “cubes” onto a canvas. The things they painted—bottles, fruit, dead birds, playing cards, guitars, a woman’s head—are vaguely recognizable, but composed of many different geometrical pieces. It was a way of showing a three-dimensional object on a two-dimensional surface. (Imagine walking around a statue to take in all the angles, and then attempting to put it on a 2-D plane.)

Room 210 makes it clear that Cubism was very much a Spaniard-driven movement. Picasso was soon joined in Paris by Madrid’s own Juan Gris. Gris adored Picasso (the feeling wasn’t mutual) and added his own spin on the Cubist style. Gris used curvier lines, brighter colors, and more recognizable images, composing his paintings as if he were pasting paper cutouts on the canvas to make a collage.

In the same room, watch Georges Méliès’ film The Extraordinary Dislocation (1901), where a man’s head and limbs become fantastically detached from his body. It scrambles expectations—juxtaposing the familiar and the impossible—in much the same way as Cubist paintings.

Proceed through the rest of the Cubism exhibit (Rooms 208 and 207), tracing the development of this cornerstone of Modernism. You’ll see how various artists expressed this same idea in different ways. The techniques they pioneered—deconstructing reality and reassembling the pieces into a collage of arresting images—would reach its culmination in the world’s most famous Cubist work: Guernica.

• Continuing counterclockwise, you enter Room 206 (“Guernica and the 1930s”). This “room” is actually a series of sub-rooms (206.01, 206.02, and so on) offering context and a setup for the main attraction. Absolutely no photos are allowed in this area. Make your way through this wing and find the big room with a movie screen-size, black-and-white canvas. You’ve reached what is likely the reason for your visit...

Perhaps the single most impressive piece of art in Spain is Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937). The monumental canvas—one of Europe’s must-see sights—is not only a piece of art but a piece of history, capturing the horror of modern war in a modern style.

While it’s become a timeless classic representing all war, it was born in response to a specific conflict—the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), which pitted the democratically elected Second Republican government against the fascist general Francisco Franco. Franco won and ended up ruling Spain with an iron fist for the next 36 years. At the time Franco cemented his power, Guernica was touring internationally as part of a fundraiser for the Republican cause. With Spain’s political situation deteriorating and World War II looming, Picasso in 1939 named New York’s Museum of Modern Art as the depository for the work. It was only after Franco’s death, in 1975, that Guernica ended its decades of exile. In 1981 the painting finally arrived in Spain (where it had never before been), and it now stands as Spain’s national piece of art.

Guernica—The Bombing: On April 26, 1937, Guernica—a Basque market town in northern Spain and an important Republican center—was the target of the world’s first saturation-bombing raid on civilians. Franco gave permission to his fascist confederate Adolf Hitler to use the town as a guinea pig to try out Germany’s new air force. The raid leveled the town, causing destruction that was unheard of at the time (though by 1944, it would be commonplace). For more on the town of Guernica and the bombing, see the Guernica section of the Basque Country chapter.

News of the bombing reached Picasso in Paris, where coincidentally he was just beginning work on a painting commission awarded by the Republican government. Picasso scrapped his earlier plans and immediately set to work sketching scenes of the destruction as he imagined it. In a matter of weeks, he put these bomb-shattered shards together into a large mural (286 square feet). For the first time, the world could see the destructive force of the rising fascist movement—a prelude to World War II.

Guernica—The Painting: The bombs are falling, shattering the quiet village. 1 A woman howls up at the sky (far right), 2 horses scream (center), and 3 a man falls from a horse and dies, while 4 a wounded woman drags herself through the streets. She tries to escape, but her leg is too thick, dragging her down, like trying to run from something in a nightmare. 5 On the left, a bull—a symbol of Spain—ponders it all, watching over 6 a mother and her dead baby...a modern pietà. 7 A woman in the center sticks her head out to see what’s going on. The whole scene is lit from above by the 8 stark light of a bare bulb. Picasso’s painting threw a light on the brutality of Hitler and Franco, and suddenly the whole world was watching.

Picasso’s abstract, Cubist style reinforces the message. It’s as if he’d picked up the shattered shards and pasted them onto a canvas. The black-and-white tones are as gritty as the black-and-white newspaper photos that reported the bombing. The drab colors create a depressing, almost nauseating mood.

Picasso chose images with universal symbolism, making the work a commentary on all wars. Picasso himself said that the central horse, with the spear in its back, symbolizes humanity succumbing to brute force. The fallen rider’s arm is severed and his sword is broken, more symbols of defeat. The bull, normally a proud symbol of strength and independence, is impotent and frightened. Between the bull and the horse, the faint dove of peace can do nothing but cry.

The bombing of Guernica—like the entire civil war—was an exercise in brutality. As one side captured a town, it might systematically round up every man, old and young—including priests—line them up, and shoot them in revenge for atrocities by the other side.

Thousands of people attended the Paris exhibition, and Guernica caused an immediate sensation. They could see the horror of modern war technology, the vain struggle of the Spanish Republicans, and the cold indifference of the fascist war machine. Picasso vowed never to return to Spain while Franco ruled (the dictator outlived him).

With each passing year, the canvas seemed more and more prophetic—honoring not just the hundreds or thousands who died in Guernica, but also the estimated 500,000 victims of Spain’s bitter civil war and the 55 million worldwide who perished in World War II. Picasso put a human face on what we now call “collateral damage.”

• After seeing Guernica, view the additional exhibits here and in adjoining rooms that put the painting in its social context. No photos allowed here either.

On the back wall on the Guernica room is a line of photos showing the evolution of the painting, from Picasso’s first concept to the final mural. The photos were taken in his Paris studio by Dora Maar, Picasso’s mistress-du-jour (and whose portrait by Picasso hangs in the adjoining Room 206.10). Notice how his work evolved from the defiant fist in early versions to a broken sword with a flower.

The room in front of Guernica (206.6) contains studies Picasso did for the painting. These studies are filled with motifs that turn up in the final canvas—iron-nail tears, weeping women, and screaming horses. Picasso returned to these images in his work for the rest of his life. He believed that everyone struggles internally with aspects of the horse and bull: rationality and brutality, humanity and animalism. Notice the etching Minotauromachy (from 1935). The Minotaur—half-man and half-bull—powerfully captures Picasso’s poet/rapist vision of man. Having lived through the brutality of the age—World War I, the Spanish Civil War, and World War II—his outlook is understandable. The adjoining room plays newsreel footage of the civil war and of Franco’s fascist regime that kept Picasso from ever returning home.

In the next room (206.7), you’ll also find a model of the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris exposition where Guernica was first displayed (look inside to see Picasso’s work). Picasso originally toyed with painting an allegory on the theme of the artist’s studio for the expo. But the bombing of Guernica jolted him into the realization that Spain was a country torn by war. Thanks to Guernica, the pavilion became a vessel for propaganda and a fundraising tool against Franco. (Notice the pavilion flies the flag of the Republicans: red, yellow, and purple.)

Near the Spanish Pavilion, you’ll see posters and political cartoons that are pro-communist and anti-Franco. Made the same year as Guernica and the year after, these touch on timeless themes related to rich elites, industrialists, agricultural reform, and the military industrial complex versus the common man, as well as promoting autonomy for Catalunya and the Basque Country.

The remaining rooms display pieces from contemporary artists reacting to the conflict of the time, whether through explicit commentary or through new, innovative styles inspired by the changing political and social culture.

• Exiting back into the corridor, continue counterclockwise to Room 205.

Another Spaniard in Paris—Salvador Dalí (1904-1989)—helped found another groundbreaking Modern Art style, Surrealism. Dalí arrived in Jazz Age Paris in the 1920s, in the wake of World War I. He hung out with his idols, fellow Spaniards Picasso, Gris, and Joan Miró, as well as an international set.

Disillusioned by the irrationality of the war, they rebelled against traditional mores and the shackles of the rational mind. Influenced by Freud’s theories about the power of the subconscious, they let their emotions and primal urges speak freely on the canvas. They painted imagery from their dreams (mindscapes, rather than landscapes). They captured the realm beyond the world we see—it was “sur-real.”

You’ll see Dalí’s distinct, melting-object style. Dalí places familiar items in a stark landscape, creating an eerie effect. Figures morph into misplaced faces and body parts. Background and foreground play mind games—is it an animal (seen one way) or a man’s face? A waterfall or a pair of legs? It’s a wide shot...no, it’s a close-up. Look long at paintings like Dalí’s The Endless Enigma (1938) and The Invisible Man (1929-1932); they take different viewers to different places.

Face of the Great Masturbator (1929) is psychologically exhausting, depicting in its Surrealism a lonely, highly sexual genius in love with his muse, Gala (while she was still married to a French poet). This is the first famous Surrealist painting. Like a dream, it mixes and matches seemingly unrelated objects. Swarming ants. A limp earthworm hanging from a hook. Faceless mannequins roaming a desert. A teetering tower of rock, cork, seashell, and olive. What does it mean? What does any dream mean? You tell me.

During this productive period, Dalí collaborated with Luis Buñuel on the classic Surrealist film Un Chien Andalou (The Andalusian Dog, 1928, in the adjoining room). It’s hard to overstate how influential this little silent film is in the world of cinema. A cloud cuts across the night sky, slicing across the moon. A man holds a razor to a woman’s eye. And then the man slices through...the eye of a dead horse. Buñuel’s juxtaposition of images into a montage is something that filmmakers today are still reckoning with. Buñuel and Dalí were members of the Generation of ’27, a group of nonconformist Spanish bohemians whose creative interests had a huge influence on art and literature in their era.

Just outside of the screening room are photographs by Man Ray (1890-1976). What Dalí did with paint and Buñuel did with film, Man Ray did with photographs—creating surreal and, yes, dreamlike images that are as haunting today as they were nearly a century ago.

• Head up to level 4, where the permanent collection continues. Start in Room 401 (which may require a bit of searching depending on which elevator you take). From there, circle this floor counterclockwise.

The organizing theme in this part of the museum is “Art in a Divided World”—a world upset by war, divided by the Iron Curtain, and under the constant threat of nuclear war. Art, too, shattered into many styles and “isms.” As you browse, use the newsreel footage to put these trends in their historical context.

The collection starts in the troubled wake of World War II, with canvases that are often distorted, harsh-colored, and violent-looking. Picasso—still in Paris—continued to invent and reflect many international trends.

With Europe in ruins, the center of the art world was moving from Paris to New York City. As you browse counterclockwise, you’ll see the distorted yet recognizable figures of Picasso give way to purely abstract art—the geometrical designs and big empty canvases of Abstract Expressionism. More and more, artists focused on the surface texture of the canvas: thick paint, cutting the canvas, or piling on fibrous substances. The canvas became not a window on the world you look through, but a kind of standalone sculpture you look at.

Meanwhile (as you’ll see in numerous rooms), Spain was still recovering from its devastating civil war and ruled by a dictatorship. Its avant-garde could not be so avant, and they lagged a decade behind the trends. But old Spanish “masters” abroad like Picasso and Miró continued to be cutting-edge into the 1960s.

The final rooms (423-429) bring in the 1960s, with its Pop Art—everyday pop-culture objects displayed as art. By now, the lingering aftermath of World War II was coming to an end, and a new, equally revolutionary age was beginning. The one element of continuity through it all is that artists of any age will portray the times in which they live by depicting the human figure.

• End your visit in the Nouvel wing. The easiest “connection” between the main building and Nouvel wing is to descend to level 2, make your way to Room 206.01, enter the Nouvel wing, descend the stairs to level 1, and start your visit in Room 104.01. But regardless of where you start, the Nouvel wing is made for browsing.

Here you’ll see art from the 1960s to the 1980s, with a thematic focus on the complexity and plurality of modern times. As revolutions liberated Third World countries, art became more global. With new technologies, the quaint ideas of art-as-a-painted-canvas give way to multimedia assemblages and installations. While these galleries have fewer household names, the pieces displayed demonstrate the many aesthetic directions of more recent modern art.

And now, having seen this museum and followed the evolution of art over a century, you don’t need anyone to explain it to you...right?

Several other worthy sights are located in and around the museum neighborhood (see the “Madrid’s Museum Neighborhood” map, earlier). This is also where my self-guided bus tour along Paseo de la Castellana to the modern skyscraper part of Madrid starts (see here).

Once the private domain of royalty, this majestic park has been a favorite of Madrid’s commoners since Charles III decided to share it with his subjects in the late 18th century. Siesta in this 300-acre green-and-breezy escape from the city. At midday on Saturday and Sunday, the area around the lake becomes a street carnival, with jugglers, puppeteers, and lots of local color. These peaceful gardens offer great picnicking and people-watching (closes at dusk). From the Retiro Metro stop, walk to the big lake (El Estanque), where you can rent a rowboat. Enjoy the 19th-century glass-and-iron Crystal Palace, which often hosts free exhibits and installations. Past the lake, a grand boulevard of statues leads to the Prado.

This museum tells the story of Spain’s navy, from 1492 to today, in a plush and fascinating-to-boat-lovers exhibit. Given Spain’s importance in maritime history, there’s quite a story to tell. Because this is a military facility, you’ll need to show your passport or driver’s license to get in. A good English brochure is available. Access to the Wi-Fi-based English audioguide can be unreliable, but give it a try.

Cost and Hours: €3, Tue-Sun 10:00-19:00, until 15:00 in Aug, closed Mon, a block north of the Prado, across boulevard from Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Paseo del Prado 5, +34 915 238 789, http://fundacionmuseonaval.com.

Across the street from the Prado and Royal Botanical Garden, this impressive exhibit hall has sleek architecture and an outdoor hanging garden—a bushy wall festooned with greens designed by a French landscape artist. The forum, funded by La Caixa Bank, features world-class temporary art exhibits—generally 20th-century art, well described in English. Ride the elevator to the top, where you’ll find a café with a daily fixed-price meal for around €14 and sperm-like lamps dangling from the ceiling; from here, explore your way down.

Cost and Hours: €6, daily 10:00-20:00, audioguide-€2, Paseo del Prado 36, +34 913 307 300.

This former post-office headquarters, now a cultural center, features mostly empty exhibition halls, an auditorium, and public hangout spaces—and is called the CentroCentro Cibeles for Culture and Citizenship. (Say that five times fast!) Skip the temporary exhibits: The real attraction lies in the gorgeous 360-degree rooftop views from the eighth-floor observation deck (ticket office outside to the right of the main entrance). Visit the recommended sixth-floor Restaurante Palacio de Cibeles and bar for similar views from its two terraces. Entering the Palacio itself is free—take advantage of its air-conditioning and free Wi-Fi.

Cost and Hours: Building free and open Tue-Sun 10:00-20:00, closed Mon; observation deck-€2, limited number of visitors allowed every half-hour 10:30-13:30 & 16:00-19:00, ticket office opens 30 minutes early, advance tickets available online; Plaza de Cibeles 1, +34 914 800 008, www.centrocentro.org.

This well-curated, rich collection of artifacts and tasteful multimedia displays tells the story of Iberia. You’ll follow a chronological walk through the wonders of each age: Celtic pre-Roman, Roman, a fine and rare Visigothic section, Moorish, Romanesque, and beyond. A highlight is the Lady of Elche (Room 13), a prehistoric Iberian female bust and a symbol of Spanish archaeology. You may also find underwhelming replica artwork from northern Spain’s Altamira Caves (big on bison), giving you a faded peek at the skill of the cave artists who created the originals 14,000 years ago. (For more on the real Altamira Caves, see the Camino de Santiago chapter.)

Cost and Hours: €3, free on Sat after 14:00 and all day Sun; open Tue-Sat 9:30-20:00, Sun until 15:00, closed Mon; multimedia guide-€2; 20-minute walk north of the Prado at Calle Serrano 13, Metro: Serrano or Colón, +34 915 777 912, www.man.es.

Take this factory tour for a look at traditional tapestry making. You’ll also have the chance to order a tailor-made tapestry (starting at $10,000).

Cost and Hours: €5, by tour only, in English at 12:00, in Spanish at 10:00, 11:00, and 13:00; open Mon-Fri 10:00-14:00, closed Sat-Sun and Aug; south of Retiro Park at Calle Fuenterrabia 2, Metro: Menendez Pelayo—take Gutenberg exit, +34 914 340 550, www.realfabricadetapices.com.

To locate these sights, see the “Greater Madrid” map at the beginning of this chapter.

Thousands of pre-Columbian and colonial artworks and artifacts make up the bulk of this worthwhile museum, though it offers few English explanations. Covering the cultures of the Americas (North and South), its exhibits focus on language, religion, and art, and provide a new perspective on the cultures of our own hemisphere. Highlights include one of only four surviving Mayan codices (ancient books) and a section about the voyages of the Spanish explorers, with their fantastical imaginings of mythical creatures awaiting them in the New World.

Cost and Hours: €3, free on Sun; open Tue-Sat 9:30-15:00, Thu until 19:00, Sun 10:00-15:00, closed Mon; Avenida de los Reyes Católicos 6, Metro: Moncloa, +34 915 492 641, http://museodeamerica.mcu.es.

Getting There: The museum is a 15-minute walk from the Moncloa Metro stop: Take the Calle de Isaac Peral exit, cross Plaza de Moncloa, and veer right to Calle de Fernández de los Ríos. Follow that street (toward the shiny Faro de Moncloa tower), and turn left on Avenida de los Reyes Católicos. Head around the base of the tower, which stands at the museum’s entrance.

In a cool and air-conditioned chronological sweep, this museum’s exhibits illustrate the history of clothing from the 18th century through today. Displays cover regional ethnic costumes, the influence of bullfighting and the French, accessories through the ages, and Spanish flappers. The only downside of this marvelous, modern museum is its remote location.

Cost and Hours: €3, free on Sat after 14:30 and all day Sun; open Tue-Sat 9:30-19:00, Thu until 22:30 in July-Aug, Sun 10:00-15:00, closed Mon; Avenida de Juan Herrera 2; Metro: Moncloa and a longish walk, bus #46, or taxi; +34 915 497 150, http://museodeltraje.mcu.es.

In this simple little Neoclassical chapel from the 1790s, Francisco de Goya’s tomb stares up at a splendid cupola filled with his own proto-Impressionist frescoes. He used the same unique technique that he employed for his “black paintings” (described earlier, under the Prado Museum listing). Use the mirrors to enjoy the drama and energy he infused into this marvelously restored masterpiece.

Cost and Hours: Free, Tue-Sun 9:30-20:00, closed Mon, Glorieta de San Antonio de la Florida 5; Metro: Príncipe Pío, then eight-minute walk down Paseo de San Antonio de la Florida; +34 915 420 722, www.esmadrid.com (search for “Ermita de San Antonio de la Florida”).

In 1968, Egypt gave Spain its own ancient temple. It was a gift of the Egyptian government, which was grateful for the Spanish dictator Franco’s help in rescuing monuments that had been threatened by the rising Nile waters above the Aswan Dam. Consequently, Madrid is the only place I can think of in Europe where you can actually wander through an intact original Egyptian temple—complete with fine carved reliefs from 200 BC. Set in a romantic park that locals love for its great city views (especially at sunset), the temple—as well as its art—is well described.

Cost and Hours: Free, open Tue-Fri 10:00-20:00 in summer, shorter hours off-season, closed Mon year-round, north of the Royal Palace in Parque de Montaña, +34 913 667 415, www.esmadrid.com (search for “Templo de Debod”).

The delightful, art-filled home of painter Joaquín Sorolla (1863-1923) is one of Spain’s most enjoyable museums. Sorolla is known for his portraits, landscapes, and use of light. Imagine the mansion, back in 1910, when it stood alone—without the surrounding high-rise buildings. With the aid of the essential audioguide, stroll through his home and studio, zeroing in on whichever painting grabs you. Sorolla captured wonderful slices of life—his wife/muse, his family, and lazy beach scenes of his hometown Valencia. He was a late Impressionist—a period called Luminism in Spain. And it was all about nature: water, light, reflection. The collection is intimate, and you can cap it with a few restful minutes in Sorolla’s Andalusian gardens. Visit in the morning to experience the works with the best natural light.

Cost and Hours: €3, free on Sat 14:00-20:00 and all day Sun; open Tue-Sat 9:30-20:00, Sun 10:00-15:00, closed Mon; last entry 45 minutes before closing, audioguide-€2.50, General Martínez Campos 37, Metro: Iglesia, +34 913 101 584, www.museosorolla.es.

This building, a hospital from 1716 to 1910, has housed a city history museum since 1929. The entrance features a fine Baroque door by the architect Pedro de Ribera, with a depiction of St. James the Moor-Slayer. Start in the basement (where you can study a detailed model of the city made in 1830) and work your way up through the four-floor collection. The history of Madrid is explained through old paintings that show the city in action, maps, historic fans, jeweled snuffboxes, etchings of early bullfighting, and fascinating late-19th-century photographs.

Don’t miss Goya’s Allegory of the City of Madrid (c. 1810), an angelic tribute to the rebellion against the French on May 2, 1808. The museum is in the trendy Malasaña district, near the Plaza Dos de Mayo, where some of the rebellion that Goya painted occurred.

Cost and Hours: Free, Tue-Sun 10:00-20:00, closed Mon, Calle de Fuencarral 78, Metro: Tribunal, +34 917 011 863, www.esmadrid.com (search for “Museo de Historia”).

Many visitors leave Madrid without ever seeing the modern “Manhattan” side of town. But it’s easy to find. From the museum neighborhood, bus #27 makes the trip straight north along Paseo del Prado and then Paseo de la Castellana, through the no-nonsense skyscraper part of this city of more than three million. The line ends at the leaning towers of Puerta de Europa (Gate of Europe). This trip is simple and cheap (€1.50 or a single ride on a 10-ride Multi Card ticket, buses run every 10 minutes, see the “Greater Madrid” map at the beginning of this chapter for route). If starting from the Prado, catch the bus from the museum side to head north; from the Reina Sofía, the stop is a couple of blocks away at the Royal Botanical Garden, at the end of the garden fence. You’ll joyride for 30-45 minutes to the last stop, get out at the end of the line when everyone else does, ogle the skyscrapers, and catch the Metro for a 20-minute ride back to the city’s center (to Puerta del Sol). The ride is particularly enjoyable at twilight, when fountains and facades are floodlit. Possible stops of interest along the way are Plaza de Colon (National Archaeological Museum) and Bernabéu (massive soccer stadium).

Historic District: Bus #27 rumbles from the end of the Paseo del Prado at the Royal Botanical Garden (opposite McDonald’s) and the Velázquez entrance to the Prado. Immediately after the Prado you pass a number of grand landmarks: a square with a fountain of Neptune (left); an obelisk and war memorial (right, with the stock market behind it); the Naval Museum (right); and Plaza de Cibeles—with the fancy City Hall and cultural center. From Plaza de Cibeles, you can see the 18th-century Gate of Alcalá (the old east entry to Madrid), the Bank of Spain, and the start of the Gran Vía (left). Then you can relax for a moment while driving along Paseo de Recoletos.

Modern District: Just past the National Library (right) is a roundabout and square (Plaza de Colon) with a statue of Columbus in the middle and a giant Spanish flag. This marks the end of the historic town and the beginning of the modern city. (Hop out here for the National Archaeological Museum.)

At this point the boulevard changes its name (and the sights I mention are much more spread out). Once named for Franco, this street is now named for the people he no longer rules—la Castellana (Castilians). Next, you pass high-end apartments and embassies. Immediately after an underpass with several modern sculptures comes the American Embassy (right, hidden behind its fortified wall). Near a roundabout with a big fountain, watch on the left for some circa-1940s buildings that once housed Franco’s ministries (typical fascist architecture, with large colonnades). You’ll pass under a second underpass and see 1980s business sprawl on the left. One of these is the distinctive Picasso Tower, resembling one of New York’s former World Trade Center towers with its vertical black-and-white stripes (it was designed by the same architect). Just after the Picasso Tower is the huge Bernabéu Stadium (right, home of Real Madrid, one of Europe’s most successful soccer teams; bus stops on both sides of the stadium).

Your trip ends at Plaza de Castilla, where you can’t miss the avant-garde Puerta de Europa, consisting of the twin “Torres Kios,” office towers that lean at a 15-degree angle (look for the big green sign BANKIA, for the Bank of Madrid). In the distance, you can see the four tallest buildings in Spain. The plaza sports a futuristic golden obelisk by contemporary Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava.

It’s the end of the line for the bus—and for you. You can return directly to Puerta del Sol on the Metro, or cross the street and ride bus #27 along the same route back to the Prado Museum or Atocha train station.

For a relaxing ride through the characteristic old center of Madrid, hop the little electric minibus #M1 (€1.50, 5/hour, 20-minute trip, Mon-Sat 8:20-20:00, none on Sun). These are designed especially for the difficult-to-access streets in the historic heart of the city, and are handy for seniors (offer your seat if you see a senior standing).

The Route: Catch the minibus near the Sevilla Metro stop at the top of Calle Sevilla, and simply ride it to the end (Metro: Embajadores). Enjoy this gritty slice of workaday Madrid—both people and architecture—as you roll slowly through Plaza Santa Ana, down a bit of the pedestrianized Calle de las Huertas, past gentrified Plaza Tirso de Molina (its junkies now replaced by a faded family-friendly flower market), and through Plaza de Lavapiés and a barrio of African and Bangladeshi immigrants. Jump out along the way to explore Lavapiés on foot, or stay on until you get to Embajadores just a few blocks away. From there, you can catch the next #M1 minibus back to the Sevilla Metro stop (it returns along a different route) or descend into the subway system (it’s just two stops back to Sol).

The Lavapiés District: In the Lavapiés neighborhood, the multiethnic tapestry of Madrid enjoys seedy-yet-fun-loving life on the streets. Neighborhoods like this typically experience the same familiar evolution: Initially they’re so cheap that only immigrants, the downtrodden, and counterculture types live there. The diversity and color they bring attracts those with more money. Businesses erupt to cater to those bohemian/trendy tastes. Rents go up. Those who gave the area its colorful energy in the first place can no longer afford to live there. They move out...and here comes Starbucks.

For now, Lavapiés is still edgy, yet comfortable enough for most. To help rejuvenate the area, the city built the big Centro Dramático Nacional Theater just downhill from Lavapiés’ main square.

The district has almost no tourists. (Some think it’s too scary.) Old ladies with their tired bodies and busy fans hang out on their tiny balconies, watching the scene. Shady types lurk on side streets (don’t venture off the main drag, don’t show your wallet or money, and don’t linger late on Plaza de Lavapiés).

If you’re walking, start from Plaza de Antón Martín (Metro: Antón Martín) or Plaza Santa Ana. Find your way to Calle del Ave María (on its way to becoming Calle del Ave Allah) and on to Plaza de Lavapiés (Metro: Lavapiés), where elderly Madrileños hang out with swarthy drunks and drug dealers; a mosaic of cultures treat this square as a communal living room. Then head up Calle de Lavapiés to the Plaza Tirso de Molina (Metro stop). Once plagued by druggies, this square is now home to flower kiosks and a playground—a good example of Madrid’s vision for reinvigorating its public spaces.

For food, you’ll find plenty of tapas bars, plus gritty Indian (almost all run by Bangladeshis) and Moroccan eateries lining Calle de Lavapiés. For Spanish fare, try $ Bar Melos, a thriving, dinner-only dive jammed with a hungry and nubile crowd. It’s famous for its giant patty melts called zapatillas de lacón y queso (because they’re the size and shape of a zapatilla, or slipper—feeds at least two, Tue-Sat 20:00-late, closed Sun-Mon, Calle del Ave María 44).

Madrid’s Plaza de Toros hosts Spain’s top bullfights on most Sundays and holidays from March through mid-October, and nearly every day during the San Isidro festival (early May-early June—often sold out long in advance). Fights start between 17:00 and 19:00 (early in spring and fall, late in summer). The bullring is at the Ventas Metro stop (a 25-minute Metro ride from Puerta del Sol, +34 913 562 200, www.las-ventas.com). For more on this tradition, see the “Bullfighting” section of the Spain: Past & Present chapter.

Tickets: Bullfight tickets range from €5 to €150. There are no bad seats at Plaza de Toros; paying more gets you in the shade and/or closer to the gore. (The action often intentionally occurs in the shade to reward the expensive-ticket holders.) To be close to the bullfighters, choose areas 8, 9, or 10; for shade: 1, 2, 9, or 10; for shade/sun: 3 or 8; for the sun and cheapest seats: 4, 5, 6, or 7. Note these key words: corrida—a real fight with professionals; novillada—rookie matadors, younger bulls, and cheaper tickets.

Two booking offices sell tickets online and in person. When buying online, read conditions carefully: The purchase voucher usually must be exchanged for a ticket at the booking office. The easiest place is Bullfight Tickets Madrid at Plaza del Carmen 1 (Mon-Sat 9:00-13:00 & 16:30-19:00, Sun 9:30-14:00, +34 915 319 131, www.bullfightticketsmadrid.com; run by José and his English-speaking son, also José, who also sells soccer tickets; will deliver tickets to your hotel). A second option is Toros La Central at Calle Victoria 3 (Mon-Fri 10:00-14:30 & 16:30-20:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-13:00, +34 915 211 213, www.toroslacentral.es).

Getting tickets through your hotel or a booking office is convenient, but they add 20 percent or more and don’t sell the cheapest seats. To save money, you can stand in the ticket line at the bullring. Except for important bullfights—or during the San Isidro festival—there are generally plenty of seats available. About a thousand tickets are held back to be sold in the five days leading up to and on the day of a fight. Scalpers hang out before the popular fights at the Calle Victoria booking office. Beware: Those buying scalped tickets are breaking the law and can lose the ticket with no recourse.

For a dose of the experience, you can buy a cheap ticket and just stay to see a couple of bullfights. Each fight takes about 20 minutes, and the event consists of six bulls over two hours. Or, to keep your distance but get a sense of the ritual and gore, tour the bull bar on Plaza Mayor (see here).

Bullfighting Museum (Museo Taurino): This museum, located at the back of the bullring, is not as good as the ones in Sevilla or Ronda (free, daily 10:00-18:00, +34 917 251 857).

Madrid, like most of Europe, is enthusiastic about soccer (which they call fútbol). The Real (“Royal”) Madrid team plays to a spirited crowd Saturdays and Sundays from September through May (tickets from €50—sold at bullfight box offices listed earlier). One of the most popular sightseeing activities among European visitors to Madrid is touring the 80,000-seat stadium. The €25 unguided visit includes the box seats, dressing rooms, technical zone, playing field, trophy room, and a big panoramic stadium view (Mon-Sat 10:00-19:00, Sun 10:30-18:30, shorter hours on game days, bus #27—see self-guided bus tour on here—or Metro: Santiago Bernabéu, +34 913 984 300, www.realmadrid.com). Even if you can’t catch a game, you’ll see plenty of Real Madrid’s all-white jerseys and paraphernalia around town.

Madrileños have a passion for shopping. It’s a social event, often incorporated into the afternoon paseo, which eventually turns into drinks and dinner. Most shoppers focus on the colorful pedestrian area between and around Gran Vía and Puerta del Sol. Here you’ll find H&M and Zara clothing, Imaginarium toys, FNAC books and music, and a handful of small local shops. The fanciest big-name shops (Gucci, Prada, and the like) tempt strollers along Calle Serrano, northwest of Retiro Park. For trendier chains and local fashion, head to pedestrian Calle Fuencarral, Calle Augusto Figueroa, and the streets surrounding Plaza de Chueca (north of Gran Vía, Metro: Chueca). Here are some other places to check out: