El Escorial • Valley of the Fallen • Segovia • Ávila

Spain’s lavish, brutal, and complicated history is revealed throughout Old Castile. This region, northwest of Spain’s capital city, is where the dominant Spanish language (castellano) originated and is named for its many castles—battle scars from the long-fought Reconquista. Before slipping out of Madrid, consider several fine side-trips here, all conveniently reached by car, bus, or train.

An hour from Madrid, tour the imposing palace at El Escorial, headquarters of the Spanish Inquisition. Nearby, at the awe-inspiring Valley of the Fallen, pay tribute to the countless victims of Spain’s bloody civil war. Segovia, an altogether lovely burg with a remarkable Roman aqueduct, fine cathedral, and romantic castle, is another worthwhile destination. And Ávila warrants a quick stop to walk its perfectly preserved medieval walls.

All of these sights are located in the rugged, mountainous part of Castile in and near the Sierra de Guadarrama range. Be prepared for hilly terrain, cooler temperatures (thanks to the altitude), and often-snowcapped mountains on the horizon...giving this area an almost alpine flavor.

History buffs can see El Escorial and the Valley of the Fallen in less than a day—but don’t go on a Monday, when both sights are closed. By bus, see them as a day trip from Madrid; by car, see them en route to Segovia.

If you just like nice towns, Segovia, also easy to reach from Madrid, is worth a half-day of sightseeing (and potentially more for lingering). If you have time, spend the night—the city is a joy in the evenings. Ávila, while charming, merits only a quick stop to marvel at its medieval walls and, perhaps, St. Teresa’s finger.

Thanks to speedy train connections, it’s possible to see Segovia on the way from Madrid to Salamanca. It’s trickier but doable to also squeeze in Ávila: Take the fast train (or bus) to Segovia, then bus from Segovia to Ávila, and finally continue to Salamanca by bus or train.

Note that Toledo and Salamanca (covered in separate chapters)—are also popular and doable side-trips from Madrid.

The Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial, worth ▲▲, is a symbol of power rather than elegance. This 16th-century palace, 30 miles northwest of Madrid, was built at a time when Catholic Spain felt threatened by Protestant “heretics,” and its construction dominated the Spanish economy for a generation (1562-1584). Because of this bully in the national budget, Spain has almost nothing else to show from this most powerful period of her history.

To its builder, King Philip II, El Escorial embodied the wonders of Catholic learning, spirituality, and arts. To 16th-century followers of Martin Luther, it epitomized the evil of closed-minded Catholicism. To architects, the building—built on the cusp between styles—exudes both Counter-Reformation grandeur and understated Renaissance simplicity. Today it’s a time capsule of Spain’s Golden Age, giving us a better feel for the Counter-Reformation and the Inquisition than any other building. It’s packed with history, art, and Inquisition ghosts. (And at an elevation of nearly 3,500 feet, it can be very cold.)

Most people visit El Escorial from Madrid. By public transportation, the bus gets you closer to the palace than the train. Remember that it makes sense to combine El Escorial with a visit to the nearby Valley of the Fallen.

By Bus: Buses to El Escorial leave from Madrid’s Moncloa bus station. At the station, follow signs to Terminal 1 (blue), go up to the platforms in the blue hallway, and find platform 11 (#664 and #661, 4/hour, fewer on weekends, 1 hour, €4.20 one-way, buy ticket from driver, Alsa, +34 911 779 951).

Either bus drops you downtown in San Lorenzo de El Escorial, a pleasant 10-minute stroll from the palace (see map): Exit the bus station from the back ramp that leads over the parked buses (note that return buses to Madrid leave from platform 3 or 4 below; schedule posted by info counter inside station). Once outside, turn left and follow the cobbled pedestrian lane, Calle San Juan, as it veers right and becomes Calle Juan de Leyva. A few short blocks later, it dead-ends at Duque de Medinaceli, where you’ll turn left and see the palace. Stairs lead past several decent eateries, through a delightful square, past the TI (Mon-Sat 9:30-14:00 & 15:00-18:00, Sun 10:00-14:00, free mini museum in back, +34 918 905 313), and directly to the tourist entry of the immense palace/monastery.

By Train: Local trains run to El Escorial from Madrid’s Atocha and Chamartín stations (cercanías line C-3A, 1-2/hour). From the El Escorial station, the palace is a 20-minute walk straight uphill through Casita del Príncipe park. Or you can take a shuttle bus (L1) from the station (2/hour, usually timed with train arrival, €1.30) or a taxi (€7.50) to the town center and the palace.

By Car: It’s quite simple and takes just under an hour. Head out of Madrid on highway A-6 (watch for signs to A Coruña). At kilometer 18, stay on A-6, skipping an exit for El Escorial. Later, around kilometer 37, you’ll see the cross marking the Valley of the Fallen ahead on the left. Keep going and exit at kilometer 47 to M-600 (following signs toward El Escorial/Guadarrama). The road goes right past the entrance to the Valley of the Fallen (after a half-mile, see a granite gate on right, marked Valle de los Caídos), then continues to El Escorial (follow signs to San Lorenzo de El Escorial, and then centro histórico).

Parking: After driving through the drab town of El Escorial, you have several options for parking near the monastery. To park in the convenient garage beneath Plaza de Constitución, watch for the very sharp turnoff on the right immediately before the monastery, then follow blue P signs on a loop through town to the garage entrance. Walking out of the garage, the monastery is just across the street and down the stairs (or turn left out of the garage to reach the TI in two short blocks). To park on the street alongside the monastery, bypass the garage turnoff, then turn right when you hit the monastery. Loop around it, watching for pay-and-display parking on your right. In a pinch, another underground garage (Parking Monasterio) is a few blocks east, under Parque Felipe II.

Leaving El Escorial: To return to Madrid (or continue to Segovia/Ávila, Toledo, or other points), follow signs to A-6 Guadarrama. After about six miles you pass the Valley of the Fallen and hit the freeway.

Cost and Hours: €12, Tue-Sun 10:00-20:00, Oct-March until 18:00, closed Mon year-round, last entry one hour before closing.

Free Entry: The palace is free to enter Wed-Thu beginning at 17:00 (Oct-March from 15:00).

Information: +34 918 905 904, www.patrimonionacional.es.

Tours: For an extra €4, a 1.5-hour guided tour takes you through the complex and other buildings on the grounds, including the House of the Infante and House of the Prince. There are few tours in English; if nothing’s running soon, go on your own: Follow the self-guided tour in this chapter, rent the €3 audioguide, or download the Monastery of El Escorial app ($2).

Visitor Information: English descriptions are scattered within the palace. For more information, get the Guide: Monastery of San Lorenzo El Real de El Escorial, which follows the general route you’ll take (€9, available at shops in the palace).

Eating: True to its austere orientation, El Escorial doesn’t even have a simple café; for food or drinks, you must venture across the street, into town. The Mercado San Lorenzo, a four-minute walk from the palace, is a good place to shop for a picnic (Mon-Fri 9:30-13:30 & 18:00-20:30—17:00-20:00 off-season, Sat 9:30-14:00, closed Sun, Calle del Rey 9). Plaza Jacinto Benavente and Plaza de la Constitución, just two blocks north of the palace complex, host a handful of nondescript but decent restaurants serving fixed-price lunches or tapas, often at shady outdoor tables.

SELF-GUIDED TOUR

SELF-GUIDED TOURThe giant, gloomy building made of gray-black stone looks more like a prison than a palace. About 650 feet long and 500 feet wide, it has 2,600 windows, 1,200 doors, more than 100 miles of passages, and 1,600 overwhelmed tourists. For even a quick visit, allow two hours.

The monasterio appears confusing at first—mostly because of the pure magnitude of this stone structure—but the visita arrows and signs help guide you through one continuous path.

• Pass through security, buy your ticket, and follow the signs to the beginning of the tour. You’ll go through a series of courtyards and stone halls that lead you into the big courtyard at the very center of the complex. Walk out into the middle of this courtyard and look back.

This is the main entrance to El Escorial. It feels less like a monastery or a palace, and more like a fortress—a fortress for God.

Four hundred years ago, the enigmatic, introverted, and extremely Catholic King Philip II (1527-1598) ruled his bulky empire from here, including giving direction to the Inquisition.

Imagine you’re Philip in the mid-1500s. Your power is derived from the Roman Catholic Church. Up north, in the German lands, a feisty monk named Martin Luther has been spreading dangerous ideas about how worshippers should create their own, unmediated relationships with God, cutting out the intermediary of priests and popes. You feel that your faith—the faith—is under fire. And so, with this bunker mentality, you devise the construction of a new national palace.

Philip II conceived the building to serve several purposes: a grand mausoleum for Spain’s royal family, starting with his father, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V; a monastery to pray (a lot) for the royal souls; a small palace to use as a Camp David of sorts for Spain’s royalty; and a school to embrace humanism in a way that promoted the Catholic faith.

Spanish architect Juan Bautista de Toledo, who had studied in Italy, was called by Philip II to carry out the El Escorial project, but he died before it was finished. His successor, Juan de Herrera, made extensive changes to Toledo’s original design and completed the palace in 1584. The style of architecture, herreriana, is known for its use of stone and slate, and is composed of straight lines and little decoration—austere to the extreme.

Look up to see the shiny crowns of the six Kings of the Tribe of Judah reigning over the immensity of this courtyard—invoking great biblical rulers to demonstrating the legitimacy of King Philip’s (and the Church’s) power.

• Now turn around and face the exit. Find the stairs in the corner (near the exit) and head upstairs to the...

Before you enter the library, pause and look at the top of the fancy wooden doorframe outside. The plaque warns “Excomunión...”—you’ll be excommunicated if you take a book without checking it out, or if you don’t show the guard your ticket. Who needs late fees when you hold the keys to hell? It’s clear that education was a priority for the Spanish royalty.

Step inside and savor this room. El Escorial was a place of learning—Catholic learning, of course, which meant that books held a special place. The armillary sphere in front of you—an elaborate model of the solar system—looks like a giant gyroscope, revolving unmistakably around Earth, with a misshapen, underexplored North America. (Galileo Galilei—another troublemaker who dared to defy the word of the Church—was formulating his dangerous heliocentric theories over in Italy even as El Escorial was being completed.) As you walk to the other end of the room, look up at the burst-of-color ceiling fresco. By Pellegrino Tibaldi, this depicts various disciplines labeled in Latin, the lingua franca of the multinational Habsburg Empire.

• Once at the far end of the hall, head downstairs. You’ll pass a WC, then go through a souvenir shop, before walking back across the Courtyard of the Kings. Go through the central arch under the six kings into the...

This basilica is the spiritual centerpiece and beating heart of this entire faith-driven enterprise. Walk through the vast, cavernous, dimly lit space until you’re positioned just in front of the high altar (at the base of the marble steps).

The basilica, the monastery, and the town adjoining El Escorial are named for San Lorenzo (St. Lawrence), who was martyred by being burned. Find the flame-engulfed grill in the center of the altar wall that features a reclining San Lorenzo taking “turn the other cheek” to new extremes. Lorenzo was so cool, he reportedly told his Roman executioners, “You can turn me over now—I’m done on this side.”

Flanking the altar are two sets of golden statues. These are cenotaphs (symbolic tombs) honoring two great Spanish kings who were instrumental in creating this place: on the left, Charles V (the first Habsburg ruler, who joined the mighty empires of Spain and Austria); and on the right, his son, Philip II, who built El Escorial. (Both monarchs are buried in the royal tomb below your feet, which we’ll visit later.) From here, you can’t see the faces of Charles or Philip...but you’re not the target audience. Later on, we’ll tour the royal apartments, upstairs. You’ll see how several bedchambers were strategically situated in a U-shape overlooking this altar area and these two great kings. The monarchs of Spain and their families could sit up in bed, peek through a window, and be reminded that all they did was in service to God and in honor of their divine ancestors.

The nave is ringed by 36 altars, each adorned with a Baroque canvas. Take a moment to view some of these. Then, on your way back up the nave toward the main door where you entered, detour to the right corner for the artistic highlight of the basilica: Benvenuto Cellini’s marble sculpture, The Crucifixion. Jesus’ features are supposedly modeled after the Shroud of Turin. Cellini carved this from Carrara marble for his own tomb in 1562 (according to the letters under Christ’s feet).

• Exit to your left and continue to the Gate House (Portería), which served as a waiting room for people visiting the monks. From here, you’ll enter the...

Turn right and work your way around the cloister, which glows with bright paintings by Pellegrino Tibaldi. Detour briefly up the main staircase, and marvel at the frescos. Luca Giordano depicted The Glory of the Spanish Monarch here, as well as painting 12 other frescoes in the monastery in 22 months—speedy Luca!

• At the end of the cloister’s first corridor, on the right, step into the...

This space was used from 1571 to 1586 while the basilica was being finished. During that time, the bodies of several kings, including Charles V, were interred here, and Philip II also had a temporary bedroom here. Among the many paintings, look for the powerful Martyrdom of St. Lawrence (by Titian) above the main altar.

• Continue circling the cloister. Along the next corridor, on the right, are the...

These rooms are where the monks met to do church business. They were (and continue to be) a small, disorganized art gallery lined with a few big names alongside many paintings with no labels—all under gloriously frescoed ceilings.

As you enter, you’re face-to-face with El Greco’s Martyrdom of St. Maurice and the Theban Legion (1580-82). Obsessed with saintly sacrifice, Philip II commissioned this from one of the most talented artists of the day. It was supposed to hang inside the basilica. But Philip was so disappointed, he commissioned a different artist to paint the same scene again...and the painting wound up here. Why? Because El Greco—in his drive to depict real human connection—made the beheading of the saint an afterthought of his composition (see the upside-down, headless body on the left edge of the frame). Instead, he focused on a moment he personally found more moving—when St. Maurice convinces his comrades not to give up on their Christian faith. Disappointed as Philip was, artistry wins out: Today, this is the most significant painting at El Escorial.

In the room on the left, look for Titian’s Last Supper.

• Head into the room on the right and go down the stairs at the far end. You’ll pass a wall of wooden archive boxes, then go through a shop, then continue into the...

El Escorial’s middle level (which we just left) is for the church. The upper level is for royal residences. And the lower level—where we are now—is for the dead. These corridors are filled with the tombs of lesser royals. Each bears that person’s name (in Latin), relationship to the king, and slogan or epitaph.

Partway through the pantheon is the evocative, wedding-cake Pantheon of Royal Children (Panteón de los Infantes), which holds the remains of various royal children who died before the age of seven (and their first Communion). This is a poignant reminder of the scourge of child mortality back in those days, even among super-wealthy royals.

• Continue down another hall of the Pantheon, with more tombs of lesser royals. You’ll walk up a flight of stairs, then down a long stairway to reach the...

This is the gilded resting place of 26 kings and queens...four centuries’ worth of Spanish monarchy in uniform gray-marble coffins, labeled with bronze plaques. All the kings are here—but the only queens allowed are mothers of kings.

A postmortem filing system is at work in the Pantheon. From the entrance, kings are on the left, queens on the right. (The only exception is Isabel II, since she was a ruling queen and her husband was a consort.)

The first and greatest, Charles V and his Queen Isabel (labeled in German, Elisabeth), flank the altar on the top shelf. Their son and the builder of El Escorial, Philip II, rests below Charles and opposite (only) one of Philip’s four wives. And so on. Spanish monarchy buffs can find all their favorites.

This prime real estate comes with a waiting process. Before a royal corpse can rest here, it needs to decompose in a nearby room for at least 25 years. The bones of the current king’s (Felipe VI) great-grandmother, Victoria Eugenia (who died in 1969), were transferred into the crypt in late 2011 (bottom left, as you face the door). And the last two empty niches are already booked: Felipe’s grandfather Don Juan (who died in 1993) has been penciled in for the top coffin above the door (see it faintly: Johannes III). Technically, he was never crowned king of Spain—Generalísimo Francisco Franco took control of Spain before Don Juan could ascend to the throne, and he was passed over for the job when Franco reinstituted the monarchy. Felipe’s grandmother who died in 2000 is the most recent guest in the rotting room (under Juan’s tomb—Maria de Mercedibus). So where does that leave Felipe’s parents, Juan Carlos and Sofía, and monarchs still to come (and go)? This hotel is completo.

• Head back up the stairs, and continue up to the...

This wing is named for the Habsburg monarchs who built El Escorial. Remember that Philip II’s father, Charles V, united the realms of Spain and Austria under the Habsburg crown, kicking off Spain’s Golden Age and funding El Escorial. We’ll meet the clan a few rooms from now. (At the end of this tour, we’ll also see the apartments of Spain’s next—and current—dynasty, the French-born Bourbons.)

You’ll begin in Philip II’s apartment. Look at the king’s humble bed...barely queen-size. Remember how Philip wanted to view Mass at the basilica’s high altar without leaving his bed? Peek through the window. The red box next to his pillow holds the royal bedpan. But don’t laugh—the king’s looking down from the wall to your left. At age 71, Philip II, the gout-ridden king of a dying empire, died in this bed (1598).

As you enter the King’s Antechamber, study the fine inlaid-wood door, one of a set of five (a gift from the German emperor that celebrates the exciting humanism of the age). The slate strip angling across the room on the floor is a sundial from 1755. It lined up with a (now plugged) hole in the wall so that at noon a tiny beam hit the middle of the three lines. Palace clocks were set by this. Where the ray crossed the strip indicated the date and sign of the zodiac.

A second sundial is in the Walking Gallery that follows. Here the royals got their exercise privately, with no risk of darkening their high-class skins with a tan. Study the 16th-century maps along the walls and look for Charles V’s 16th-century portable altar at the end of the room.

The Audience Chamber is now a gallery filled with portraits of the—let’s be honest—quite unattractive Habsburg royals. These portraits provide an instructive peek at the consequences of mixing blue blood with more of the same blue blood (inbreeding among royals was a common problem throughout Europe in those days). Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500-1558, who is known as King Charles I in Spain) is over the fireplace mantel. Charles, Philip II’s dad, was the most powerful man in Europe, having inherited not only the Spanish crown, but also control over Germany, Austria, the Low Countries (Belgium and the Netherlands), and much of Italy. When he announced his abdication in 1555, his son Philip II inherited much of this territory...plus the responsibility of managing it. Philip’s draining wars with France, Portugal, Holland, and England—including the disastrous defeat of Spain’s navy, the Spanish Armada, by England’s Queen Elizabeth I (1588)—knocked Spain from its peak of power and began centuries of decline.

The guy with the red tights to the right of Charles is his illegitimate son, Don Juan de Austria—famous for his handsome looks, thanks to a little fresh blood. Other royal offspring weren’t so lucky: When one king married his niece, the result was Charles II (1665-1700, to the right of the door you came in). His severe underbite (an inbred royal family trait) was the least of his problems. An epileptic before that disease was understood, poor “Charles the Mad” would be the last of the Spanish Habsburgs. He died without an heir in 1700, ushering in the continent-wide War of the Spanish Succession and the dismantling of Spain’s empire.

Continuing through the palace, notice the adjustable sedan chair that Philip II, thick with gout, was carried in (for seven days) on his last trip from Madrid to El Escorial. He wanted to be here when he died.

Go through the Guards’ Room to the King’s Apartments and find the small portrait of Philip II flanked by two large paintings of his daughters. The palace was like Philip: austere. Notice the simple floors, plain white walls, and bare-bones chandelier. Peek into the bedroom of one of his daughters, Isabel Clara Eugenia. The sheet warmer beside her bed was often necessary during the winter. If the bed curtains are drawn, bend down to see the view from her bed...of the high altar in the basilica next door. The entire complex of palace and monastery buildings was built around that altar.

• Go up several stairs to the...

Its paintings celebrate Spain’s great military victories—including the Battle of San Quentin over France (1557) on St. Lawrence’s feast day, which inspired the construction of El Escorial. The sprawling series, painted in 1590, helped teach the new king all the elements of warfare. Stroll the length for a primer on army tactics and formations.

• Head back down the same stairs, and then down again to the level where you entered. Follow exit signs through a series of courtyards; you’ll pass a hall on the right that houses good temporary exhibits. Step in and check out what’s on.

From there, carry on toward the exit. Just before you leave, notice the sign on the right, directing you up the stairs to the...

These royal apartments—the frilly yin to the Habsburgs’ austere yang—offer a delightful change of pace and an antidote to the otherwise oppressively somber palace.

Remember Charles II, the inbred, epileptic Habsburg king who never bore an heir? His death kicked off the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714). The result was that the French grandson of Louis XIV became King Philip V of Spain. And Philip V’s son, Charles III, modified this part of the palace to have a French-style layout. It was occupied by royalty in the fall, so they kept warm by covering the walls with tapestries, mostly with scenes of hunting, the main activity when they retreated here. Most of the tapestries were made in the Royal Tapestry Factory in Madrid (which you can still visit today).

As you wander through several rooms, look for tapestries made from Goya cartoons, including—in the first room, the Banqueting Hall—Dance on the Banks of the Manzanares Canal (the cartoon is in Madrid’s Municipal Museum). Continuing through the collection, savor several more playful, colorful Goya tapestries depicting cheery slices of life. Take a quick spin through room after vivid room of sumptuous apartments, listening for the ticking of the clock collection, a contribution of Charles IV. Wandering these grand halls, think of the through-line of Spanish history...today’s King Felipe VI is also a Bourbon, the great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandson of France’s “Sun King,” Louis XIV.

• Our tour is done. From here, you can head on outside. To get a nice view of El Escorial from its fine gardens—rather than the stark plaza that surrounds it on two sides, you can head to...

To reach the gardens (free to enter), circle all the way around the right side of the building as you face it. Going beneath the arcade running over the road, look left for the garden entrance. While the gardens are as stark and geometrical as the building itself (with sharply manicured hedges rather than flowers and trees), this is where you’ll enjoy the best views of El Escorial—especially in the afternoon light. Listen for a nagging peacock and enjoy the views over the wooded hillsides to the distant skyscrapers of Madrid.

Drivers can visit the nearby Silla de Felipe II (Philip’s Seat), a rocky viewpoint where the king would come to admire his palace as it was being built. It’s well-marked from M-505, which runs between Madrid and Ávila. If you leave El Escorial by first heading back toward Madrid and then turning off for Ávila, you’ll see the turnoff to Philip’s Seat on your left after about a mile. It’s a couple minutes’ drive up a twisty road to a hill adjacent to the monastery.

Six miles from El Escorial, high in the Sierra de Guadarrama Mountains, is the Valley of the Fallen (Valle de los Caídos). A 500-foot-tall granite cross marks this immense and powerful underground monument to the victims of Spain’s 20th-century nightmare—the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). That conflict is still extremely controversial in Spain today—rarely commemorated by monuments or even discussed in museums. Considering that, the Valley of the Fallen is a must for those interested in 20th-century history (or fascist architecture).

Until recently, the Valley of the Fallen was also the final resting place of Generalísimo Francisco Franco, Spain’s dictator from 1939 until his death in 1975. But in late 2019, after years of debate, Franco’s remains were exhumed and moved to his wife’s mausoleum in the Mingorrubio Cemetery in El Pardo, a suburb of Madrid.

Most visitors side-trip to the Valley of the Fallen from El Escorial. If you don’t have your own wheels, the easiest way to get between these two sights is to negotiate a deal with a taxi (to take you from El Escorial to Valley of the Fallen, wait 30-60 minutes, and then bring you back to El Escorial—figure €45 total). There’s also a bus service, but the timing isn’t the most convenient (€11.20 includes entrance fee, 1/day Tue-Sun at 15:15, 15 minutes, return bus to El Escorial leaves at 17:30—a long time to spend here).

Drivers can find tips under El Escorial’s “Getting There—By Car,” earlier. Pay at the booth as you enter from the main road, then drive about three miles through a pine forest to the site itself. A big parking lot is next to the café, a short walk from the basilica.

Cost and Hours: €9, Tue-Sun 10:00-19:00, Oct-March until 18:00, closed Mon year-round, +34 918 905 411, www.valledeloscaidos.es.

Mass: You can enter the basilica during Mass, but you can’t sightsee the central area or linger afterward. One-hour services run Tue-Sat at 11:00 and Sun at 11:00, 13:00, and 17:30 (17:00 in winter). During services, the entire front of the basilica (altar and tombs) is closed. Mass is usually accompanied by the resident boys’ choir, the “White Voices” (Spain’s answer to the Vienna Boys’ Choir).

Visitor Services: There’s a $$ café with WCs at the site’s main parking lot.

The main thing to see at the Valley of the Fallen is the basilica interior. While the cross at the top of the monument is undergoing a lengthy restoration, there is no access to it by funicular or by foot along the trail (marked Sendero de la Cruz). Given that, an hour is enough for a quick visit.

Approaching by car or bus, you enter the sprawling park through a granite gate. The best views of the cross are from the bridge (but note that it’s illegal for drivers to stop anywhere along this road). On the right, tiny chapels along the ridge mark the stations of the cross, where pilgrims stop on their hike to this memorial.

In 1940, prison workers dug 220,000 tons of granite out of the hill to form an underground basilica, then used the stones to erect the cross (built like a chimney, from the inside). Since it’s built directly over the dome of the subterranean basilica, a seismologist keeps a careful eye on things.

The stairs that lead to the imposing monument are grouped in sets of tens, meant to symbolize the Ten Commandments (including “Thou shalt not kill”—hmm). The emotional pietà draped over the basilica’s entrance is huge—you could sit in the palm of Christ’s hand. The statue was sculpted by Juan de Ávalos, the same artist who created the dramatic figures of the four Evangelists at the base of the cross. It must have had a powerful impact on mothers who came here to remember their fallen sons.

A solemn silence and a stony chill fill the basilica. At 300 yards long, it was built to be longer than St. Peter’s...but the Vatican had the final say when it blessed only 262 of those yards. It’s nearly empty inside, making it feel much larger.

After walking through the two long vestibules, stop at the iron gates of the actual basilica. The line of torch-like lamps adds to the shrine-like ambience. Franco’s prisoners, the enemies of the right, spent a decade digging this memorial out of solid rock. (Though it looks like bare rock still shows on the ceiling, it’s just a clever design.) The sides of the monument are lined with copies of 16th-century Brussels tapestries of the Apocalypse, and alabaster statues of the Virgin Mary perch above the arches of the side chapels. Notice the hooded figures peering out at you all over the space.

Take the long walk down the nave, then up 10 steps into the main part of the church, populated with rough wooden pews. Under a glittering mosaic dome is the high altar. At the base of the dome, four gigantic bronze angels look down over you.

Interred behind the high altar and side chapels (marked “RIP, 1936-1939, died for God and country”) are the remains of approximately 34,000 people, including both Franco’s Nationalists and the 12,000 or so anti-Franco Republicans who lost their lives in the war (the urns are not visible). This is also where Franco was interred until his body was moved to Madrid in 2019—you might still see flowers strewn on the site of Franco’s original grave.

In front of the altar is the grave of José Antonio Primo de Rivera (1903-1936), the founder of Spanish fascism, who was killed by Republicans during the civil war; as one of the fallen, he remains buried in the basilica. Next to the fascist’s grave, the statue of a crucified Christ is lashed to a timber Franco himself is said to have felled. The seeping stones seem to weep for the victims.

Today, families of the buried Republicans and Nationalists, along with many Spaniards, remain conflicted about the Valley of the Fallen. The war is still a deep wound in Spanish society, and the sight inspires heavy emotions and controversy about what the future of the monument should really be.

As you leave, stare into the eyes of those angels with swords and think about all the “heroes” who keep dying “for God and country,” at the request of the latter.

The expansive view from the monument’s terrace includes the peaceful, forested valley and sometimes snow-streaked mountains.

A beautiful city built along a ridge, Segovia is one of Madrid’s most tempting day trips...and even better overnight. Fifty miles from Madrid, this town of 55,000 boasts a thrilling Roman aqueduct, a grand cathedral, and a historic castle. Historically, Segovia was a Roman town that limped along through the centuries, finally becoming a medieval stronghold of the kings and queens of Castile.

While merely a footnote in the annals of Spanish history, Segovia enjoyed a certain prosperity (thanks to its lucrative textile industry) and remains one of Spain’s most pleasant towns. Since the city is more than 3,000 feet above sea level and just northwest of a mountain range, it’s exposed to cool northern breezes, and people come here from Madrid for a break from the summer heat. It’s a fun place to simply hang out and enjoy some low-impact sightseeing.

Day-Tripping from Madrid: Considering the easy train and bus connections, Segovia makes a fine day trip from Madrid (30 minutes one-way by AVE train, 1.5 hours by bus; see “Segovia Connections” for details). The disadvantages of this plan are that you spend the coolest hours of the day (early and late) en route, you miss the charming evening scene in Segovia, and you’ll pay more for a hotel in Madrid than in Segovia. If you have time, spend the night. But even if you just stay the day, Segovia offers a rewarding and convenient break from the big-city intensity of Madrid.

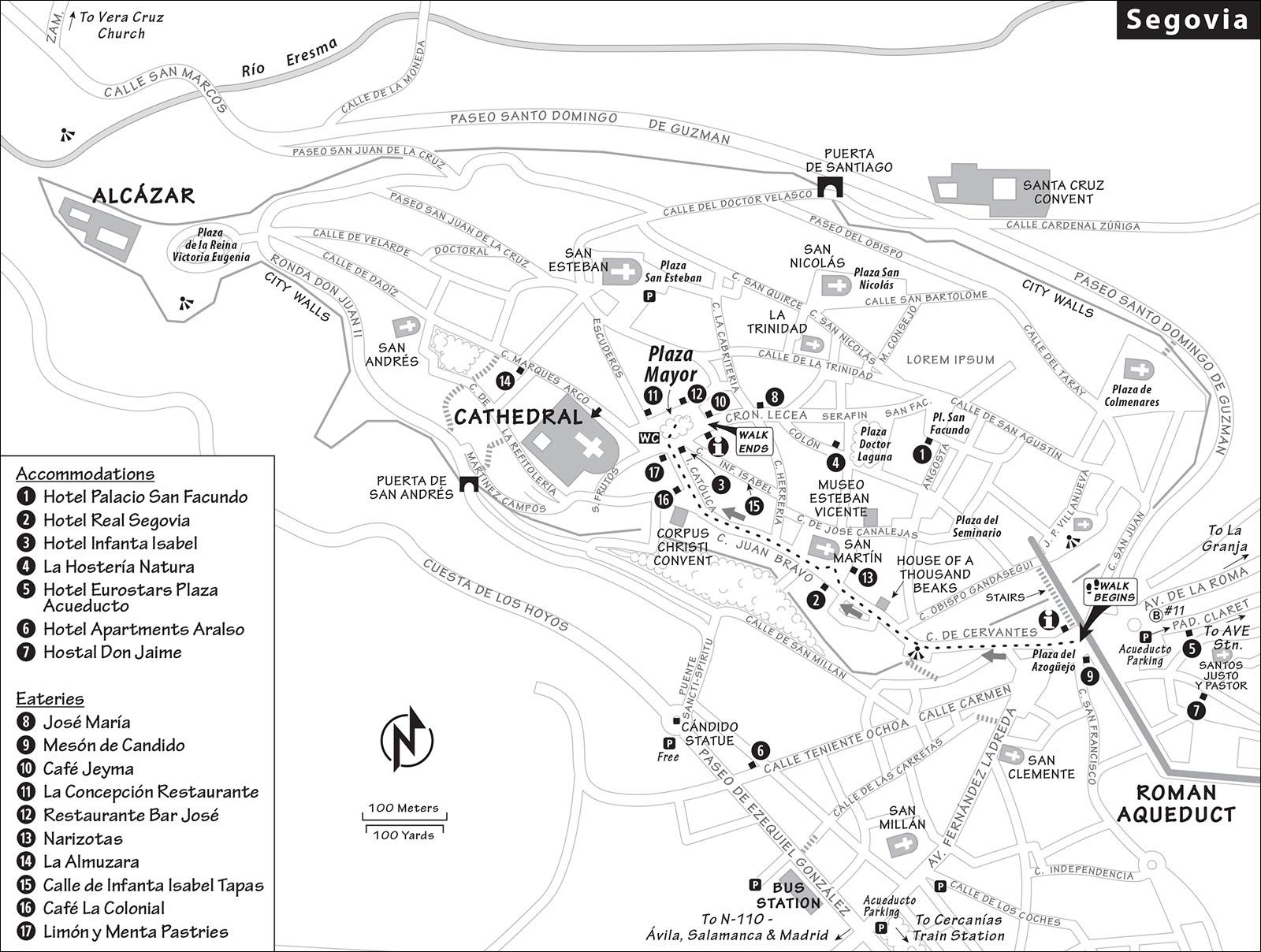

Segovia is a medieval “ship” ready for your inspection. Start at the stern—the aqueduct—and stroll up Calle de Cervantes and Calle Juan Bravo to the prickly Gothic masts of the cathedral. Explore the tangle of narrow streets around playful Plaza Mayor, then descend to the Alcázar at the bow.

Tourist Information: The TI at Plaza del Azogüejo, at the base of the aqueduct, specializes in Segovia and has friendly staff, two wooden models of Segovia helpful for orientation, pay WCs, and a gift shop (Mon-Sat 10:00-18:30, Sun until 17:00, +34 921 466 720, www.turismodesegovia.com). A different TI, on Plaza Mayor, covers both Segovia and the surrounding region (at #10; daily Mon-Sat 9:30-14:00 & 16:00-19:00, Sun 9:30-17:00, shorter hours mid-Sept-June, +34 921 460 334, www.turismocastillayleon.com). A smaller TI at the AVE train station opens for weekend day-trippers (Sat-Sun 10:00-13:30 only, +34 921 447 262).

If day-tripping from Madrid, confirm the return schedule when you arrive here.

By Train: There’s no luggage storage at the AVE train station (called Guiomar). From the station, ride bus #11 for 20 minutes to the base of the aqueduct. Bus #12 also takes you into town, but it drops you off at the bus station, a 10-minute walk to the aqueduct.

By Bus: You’ll find luggage storage near the exit from the bus station (tokens sold daily 9:00-14:00 & 16:00-19:00, gives you access to locker until end of day). It’s a 10-minute walk from the bus station to the town center: Exit left out of the station, continue straight across the street, and follow Avenida Fernández Ladreda, passing San Millán church on the left, then San Clemente church on the right, before coming to the aqueduct.

By Car: It’s best not to drive into the heart of town, which requires maneuvering your car uphill through tight bends. Instead, park in the free lot northwest of the bus station by the statue of Cándido, along the street called Paseo de Ezequiel González. If the walk up the hill from this lot to the Alcázar is too much—or if the lot is full (which happens often), there’s a central but pricey option—the Acueducto Parking underground garage. Enter this garage kitty-corner from the bus station, or—at its opposite end—from near the base of the aqueduct. If you must park in the old town, look for spots marked with blue stripes, pay the nearby meter, and place the ticket on your dashboard (pay meter every 2 hours; free parking 20:00-9:00, Sat afternoon, and all day Sun).

Free Churches: Segovia has plenty of little Romanesque churches that are free to enter shortly before or after Mass (see TI for a list of times). Many have architecturally interesting exteriors that are worth a look. Keep your eyes peeled for these hidden treasures: Church of Santos Justo y Pastor, above the aqueduct; San Millán church on Avenida Fernández Ladreda; San Martín church, on a square of the same name; and San Andrés church on the way to the Alcázar on Plaza de la Merced.

Shopping: A flea market is held on Plaza Mayor on Thursdays (roughly 8:00-15:00, food also available.

Group Tours: The TI on Plaza del Azogüejo, at the base of the aqueduct, offers a two-hour “World Heritage” tour in English (€14, includes entrance to the Alcázar and sometimes the cathedral, 3/week in English at 11:00, check schedule and reserve at TI, +34 921 466 720).

Walk with a View: With its trio of visually striking landmarks (aqueduct, cathedral, Alcázar) perched atop a ridge, Segovia boasts more than its share of fine views. If you’re up for a longish walk, consider following the valley road all the way around the base of Segovia’s promontory. Much of the route is labeled Ruta Turística Panorámica. From the bus-station area, follow Cuesta de los Hoyos west, loping around under the Alcázar (with striking views of its Disney-like towers). Then, when you cross the river, turn right and hook back around the north side of town—detouring to the Vera Cruz Church. From there, you can take the steep trail back up to the Alcázar, or continue all the way along the river, then cut back up to the aqueduct.

This 30-minute self-guided walk starts at the Roman aqueduct and goes uphill along the pedestrian-only street to the main square. It’s most enjoyable just before dinner, when it’s cool and filled with strolling Segovians.

• Start at...

This lively square, often enlivened by a cheery carousel, is named “small market” (compared to the big market—Plaza Mayor—at the end of this walk).

The square is dominated by Segovia’s defining feature: its 2,000-year-old, hundred-foot-high acueducto romano—worth ▲▲. Ancient Segóbriga was approximately the same size as today’s Segovia—with some 50,000 inhabitants, including soldiers at a military base, all of whom needed a reliable water supply. Emperor Trajan’s engineers built a nine-mile aqueduct to channel water from the Río Frío to the city, culminating at the Roman castle (today’s Alcázar). The exposed section of the aqueduct that you see here is 2,500 feet long and 100 feet high, has 118 arches, was made from 20,000 granite blocks without any mortar, and can still carry a stream of water.

The aqueduct was damaged in the Reconquista warfare of the 11th century and was later rebuilt by Queen Isabel. It functioned until the late 19th century. Notice the cross at the base and the statue in the high niche of the Virgen de la Fuencisla—Segovia’s patron saint. (In Roman days this held a statue of Hercules.)

From the square, a grand stairway leads from the base of the aqueduct to the top—offering close-up looks at the imposing work and a sweeping water’s-eye-view panorama over the length of the aqueduct. Back at ground level, as you walk through Segovia’s streets, keep an eye out for small plaques depicting the arches of the aqueduct, which tell you where the subterranean channel runs through the city.

Facing the square is the flashy Mesón de Cándido—the most famous of many Segovia restaurants serving the famous local specialty, roast suckling pig (cochinillo asado). (For recommendations of places to try this specialty, see “Eating in Segovia,” later.) On the other side of the aqueduct is a practical little roundabout where buses zip to and from the train station.

• Now head up...

With the aqueduct at your back, head uphill on Calle de Cervantes, appreciating the workaday nature of the town and some of its more imaginative architecture. This street is known as the Calle Real—the “Royal Street”—because it leads, eventually, to the Alcázar.

Pause after about a block, at the gap in the buildings on the left, and enjoy the viewpoint (Mirador de la Canaleja). Survey the rooftops of Segovia’s lower neighborhood, San Millán, and notice how the city is carved out of a very hilly terrain. On the horizon are the often-snowcapped Sierra de Guadarrama mountains that separate Segovia and Madrid.

Continue up the street. Just uphill on the right, you can’t miss the unmistakably prickly facade of the so-called “house of a thousand beaks” (Casa de los Picos). This building’s original Moorish design is still easy to see, despite the wall just past the door that blocks your view from the street. This wall, the architectural equivalent of a veil, hid this home’s fine courtyard—Moors didn’t flaunt their wealth. You can step inside to see art students at work and perhaps an exhibit on display, but it’s most interesting from the exterior.

Notice the house’s truncated tower—one of many fortified towers that marked the homes of feuding local noble families. In medieval Spain, clashing loyalties led to mini civil wars. In the 15th century, as Ferdinand and Isabel centralized authority in Spain, nobles were required to lop their towers. You’ll see the once-tall, now-stubby towers of 15th-century noble mansions all over Segovia.

Continue up the main drag (which has now become Calle de Juan Bravo). Another example of a once-fortified, now-softened house with a cropped tower is about 50 yards farther up, on the left, at tiny Plaza del Platero Oquendo.

Continue uphill until you come to the complicated Plaza de San Martín, a commotion of history surrounding a striking statue of Juan Bravo. When Spain’s King Charles V, a Habsburg who didn’t even speak Spanish, took power, he imposed his rule over Castile. This threatened the local nobles, who, inspired and led by Juan Bravo, revolted in 1521. Although Juan Bravo lost the battle—and his head—he’s still a symbol of Castilian pride. This statue was erected in 1921, on the 400th anniversary of his death.

In front of the Juan Bravo statue stands the bold and bulky House of Siglo XV. Its fortified Isabelino style was typical of 15th-century Segovian houses. Later, in a more peaceful age, the boldness of these houses was softened with the decorative stucco work called esgrafiado—Arabic-style floral and geometrical patterns—that you see today (for example, in the big house behind Juan Bravo). The 14th-century Tower of Lozoya, behind the statue, is another example of the lopped-off towers.

On the same square, the 12th-century Church of St. Martín is Segovian Romanesque in style: a mix of Christian Romanesque (clustered columns with narrative capitals) and Moorish styles (minaret-like towers built with bricks).

Continue up the street another 100 yards, until you reach a triangular square. The Gothic arch on the left is the entrance to the Corpus Christi Convent. For €1, you can pop in to see the Franciscan church, which was once a synagogue, which was once a mosque (closed Tue and Fri). It is sweet and peaceful, with lots of art featuring St. Francis, and allows you to see the layers of religious history here. Also in the building’s entryway, look for the little window where cloistered nuns sell the treats they make on the premises.

Back out on the little square, notice the narrow street forking off to the left, which leads to Segovia’s former Jewish quarter. As throughout Europe, Jews were relegated to the less-desirable land (lower on the hill, and therefore more vulnerable to attackers). While there’s not much to see from this time, those with a special interest can follow this street a couple of blocks down. The columned building on the left (at #12) was once the house of Abraham Seneor, who was a rabbi and an accountant for Spain’s royal family. This building now holds municipal offices, as well as an information center about the Jewish story of Segovia.

• To stick with the main part of this walk, back at the Corpus Christi Convent take the right fork up to pop out in Segovia’s inviting...

This was once the scene of executions, religious theater, and bullfights with spectators jamming the balconies. The bullfights ended in the 19th century. When Segovians complained, they were given a gentler form of entertainment—bands in the gazebo. Today the very best entertainment here is simply enjoying a light meal, snack, or drink in your choice of the many restaurants and cafés lining the square.

The Renaissance church opposite the twin-spired City Hall and behind the TI was built to replace the church where Isabel was proclaimed Queen of Castile in 1474. The symbol of Segovia is the aqueduct where you started—find it in the seals on the Theater Juan Bravo and atop the City Hall. Finally, treat yourself to the town’s specialty pastry, ponche segoviano (marzipan cake), at the recommended Limón y Menta, the bakery on the corner where you entered Plaza Mayor.

The three big sights in Segovia are its cathedral, Alcázar, and aqueduct. The aqueduct is covered on the “Segovia Walk,” earlier; the cathedral and Alcázar are described next.

Segovia’s cathedral, built from 1525 through 1768 (the third on this site), was Spain’s last major Gothic building. Embellished to the hilt with pinnacles and flying buttresses, the exterior is a great example of the final, overripe stage of Gothic, called Flamboyant. Yet the Renaissance arrived before it was finished—as evidenced by the fact that the cathedral is crowned not by a spire, but by a dome. The spacious and elegantly simple interior provides a delightful contrast to the frilly exterior.

Cost and Hours: €7 combo-ticket includes cathedral and tower, individual tickets available; cathedral—€3, free Sun 9:00-10:00, Nov-March 9:30-10:30 (cathedral access only—no cloisters), open daily 9:30-21:30, Nov-March until 18:30; tower—€7, visits by guided tour only, tours depart every 90 minutes 10:30-19:30 (fewer in winter), English tour at 15:00; +34 921-462-205, https://catedralsegovia.es/.

Visiting the Cathedral: As you enter, angle right to the choir, which features finely carved wooden stalls from the previous church (1400s). The cátedra (bishop’s chair) is in the center rear of the choir.

The many side chapels are mostly 16th-century and come with big locking gates—a reminder that they were the private sacred domain of the rich families and guilds that “owned” them. They could enjoy private Masses here with their names actually spoken in the blessings and a fine burial spot close to the altar.

Find the Capilla La Concepción (as you face the choir, it’s the last chapel ahead on the right, just inside the door to the terrace). Its many 17th-century paintings hang behind a mahogany wood gate imported from colonial America. The painting, Tree of Life, by Ignacio Ries (left of the altar), shows hedonistic mortals dancing atop the Tree of Life. As a skeletal Grim Reaper prepares to receive them into hell (by literally chopping down the tree...timberrrr), Jesus rings a bell imploring them to wake up before it’s too late. The chapel’s center statue is Mary of the Apocalypse (as described in Revelations, standing on a devil and half-moon, which looks like bull’s horns). Mary’s pregnant, and the devil licks his evil chops, waiting to devour the baby Messiah.

Opposite from where you entered, a fine portal (which leads into the cloister) is crowned by a painted Flamboyant Gothic pietà in its tympanum.

Step through that portal into the cloister, turn right, and circle counterclockwise. The first room you’ll come to is a nice little museum containing paintings and silver reliquaries. Continuing around the cloister, the next door leads into the sumptuous, gilded chapter room—draped with precious Flemish tapestries. Out in the bottom of the stairwell, notice the gilded wagon. The Holy Communion wafer is placed in the top of this temple-like cart and paraded through town each year during the Corpus Christi festival. At the top of the stairs is a collection of tapestries and vestments under delicate fan vaulting. Back out in the cloister, hanging on the wall between rooms, a glass case displays keys to the 17th-century private chapel gates. Circle the rest of the way around the cloister, enjoying the peace. From the cloister courtyard, you can see the Renaissance dome rising above the otherwise Gothic rooftop.

The 290-foot tower offers stunning views of the city and the surrounding area. You can climb 190 steps to the top on a guided tour several times a day (enter directly opposite the Capilla La Concepción).

Segovia has one of the most fanciful, striking castles in all of Spain, thanks to a Romantic Age remodel job. It’s the closest thing Spain has to its own Neuschwanstein. In the Middle Ages, this fortified palace was one of the favorite residences of the monarchs of Castile, and a key fortress for controlling the region. The Alcázar grew through the ages, and its function changed many times: After its stint as a palace, it was a prison for 200 years, and then a royal artillery school. It burned in 1862, after which it was remodeled in the eye-pleasing style you see today. First ogle the exterior. Then visit the finely decorated interior and view terrace. And finally—if you don’t mind the steps—you can climb to the top of the tower for the only 360-degree city view in town. This description quickly covers the highlights, but the audioguide is a good investment if you’d like the full story.

Cost and Hours: Palace—€5.50, daily 10:00-20:00, Nov-March until 18:00, €3 audioguide describes each room (45 minutes, €5 deposit); tower—€2.50, same hours as palace except closed in windy or rainy weather; +34 921 460 759, www.alcazardesegovia.com.

Visiting the Alcázar: Buy your ticket in the building on the left as you face the Alcázar (and ask for a map near the ticket desk). Then head over the drawbridge. Peer down into the deep, deep “moat,” and appreciate the strategic smarts of building a castle on a promontory at the tip of Segovia’s ridge.

Once inside, follow signs to the start of the tour. You’ll enjoy a one-way route through 11 royal rooms. What you see today inside the Alcázar is rebuilt, like the outside—a Disney-esque exaggeration of the original. Still, its fine Moorish decor and historic furnishings are fascinating. The sumptuous ceilings are accurately restored in Mudejar style.

Entering the exhibit, you’ll be greeted by knights on horseback, then find your way to the Throne Room, whose ceiling is the artistic highlight of the palace. Facing the throne are portraits of Ferdinand and Isabel, whose union made Spain a medieval powerhouse.

Next, in the Gallery Room—with another fine ceiling—is a big mural of Queen Isabel the Catholic being proclaimed Queen of Castile and León in Segovia’s main square in 1474. Enjoying the views of the countryside from the huge windows, it’s clear the current building was designed in the “just for show” late 19th century, rather than the original “danger lurks around every corner” Middle Ages.

Carry on through more rooms, including the Pine Cone Room, where 392 pinecone-shaped adornments hang from the Mudejar ceiling. The Royal Bedroom is made cozy by hanging tapestries on the stony walls.

Pause to savor the striking Hall of the Monarchs. The upper walls feature statues of the 52 rulers of Castile and León who presided during the long and ultimately successful Reconquista (711-1492): from Pelayo (the first, over the room’s exit door and a bit to the left), clockwise to Juana VII (the last). There were only seven queens during the period (the numbered ones).

From here, head through the small, window-lined Cord Room (decorated with the cord-like belts of the Franciscan order) to reach the chapel. As you face the main altar, notice the painting in the center of the altar on your left: A scene of St. James the Moor-Slayer—with Muslim heads literally rolling at his feet. James is the patron saint of Spain. His name was the rallying cry in the centuries-long Christian crusade to push the Muslim Moors back into Africa.

Exiting the royal rooms, step into the modest armory. The finest item is the 16th-century, ornately carved ivory crossbow, with a hunting scene shown in the accompanying painting.

From the armory, step out onto the terrace (the site of the original Roman military camp, circa AD 100; may be closed in winter and in bad weather). Taking in its vast views, marvel at the natural fortification provided by this promontory cut by the confluence of two rivers. The Alcázar marks the end (and physical low point) of the gradual downhill course of the nine-mile-long Roman aqueduct. Can you find the mountain nicknamed Mujer Muerta (“dead woman”)?

On your way back out, you can cut through the Museum of Artillery, recalling the period (1764-1862) when this was the royal artillery school. It shows the evolution of explosive weaponry, with old photos and prints of the Alcázar.

Finally, back at the drawbridge, you can choose to climb the tower. Hiking 152 steps up a tight spiral staircase rewards you with sweeping views over town and the countryside.

A collection of abstract art by local artist Esteban Vicente (1903-2001) is housed in two rooms of the remodeled remains of Henry IV’s 1455 palace. Wilder than Rothko but more restrained than Pollock, Vicente’s vibrant work influenced post-WWII American art. For contemporary art aficionados, the temporary exhibits can be more interesting than the permanent collection.

Cost and Hours: Free; open Tue-Fri 11:00-14:00 & 16:00-19:00 (July -Sept 17:00-20:00), Sat 11:00-20:00, Sun 11:00-15:00, closed Mon; +34 921 426 010, www.museoestebanvicente.es.

Perched on a ridge below the Alcázar is this unusual, historic church. Built in the 13th century by an order of chivalric knights (possibly the Knights Templar), this 12-sided Romanesque church once supposedly housed a piece of the “true cross.” Pick up an English flier at the entrance and step into the simple, nearly unadorned interior, where you’ll find a unique floor plan: a circular nave ringing a giant central column called an edicule. The inner chamber was used for chivalrous ceremonies. (While this architecture was typical of churches built by knights’ orders, few survive today.) You’ll see the red Maltese cross, signifying that the church is still linked with the Knights Hospitaller, who still use it from time to time. With its unique shape and history, the space carries a mystical feeling. And the views back up to the Alcázar from here are excellent as well.

Cost and Hours: €2, Wed-Sun 10:30-13:30 & 16:00-19:00, Tue 16:00-19:00 only, until 18:00 in winter, closed Mon and when caretaker takes his autumn holiday; outside town beyond the castle, 25-minute walk from main square; +34 921 431 475.

This “little Versailles,” six miles south of Segovia, is much smaller and happier than nearby El Escorial. The palace and gardens were built by the homesick French-born King Philip V, grandson of Louis XIV. Today it’s restored to its original 18th-century splendor, with its royal collection of tapestries, clocks, and crystal (actually made at the palace’s royal crystal factory). Plumbers and gardeners imported from France and Italy made Philip a garden that rivaled Versailles’. The Bourbon Philip chose to be buried here (in the adjacent church) rather than with his Habsburg predecessors at El Escorial.

Cost and Hours: Palace—€9, Tue-Sun 10:00-20:00, Oct-March until 18:00, closed Mon year-round, last entry one hour before closing, audioguide-€3, guided tour-€4 (ask for one in English—you might need to wait); park—free except when fountains are running (when you may need a palace ticket or €4 fountains-only ticket to enter), daily 8:00-20:30, until 21:30 in summer, shorter hours off-season; +34 921 470 019, www.patrimonionacional.es.

Getting There: Linecar buses make the 25-minute trip from Segovia (catch at the bus station) to San Ildefonso-La Granja (check schedule online, +34 921 427 705, www.linecar.es). Drivers find the palace at the top of town, facing a peaceful park; there’s no official parking lot, but plenty of free street parking nearby.

Visiting the Palace and Gardens: The palace interior ranks low on a European scale (nearby, Madrid’s Royal Palace and El Escorial’s Bourbon Palace are better). And it’s hard to appreciate without the audioguide. After touring three large rooms of tapestries, you’ll circulate through the typical lineup of royal apartments—ceiling frescoes, glittering chandeliers, gilded furniture, marble floors, and lots of paintings by little-known artists. The ground-floor halls are lined with Neoclassical states and garden views.

You’ll exit the palace into the real draw: the gardens. (You can also enter the gardens directly—for free—by circling all the way around the right side of the palace.) The sprawling grounds radiate out from the palace in a Versailles-like grid-and-axis layout, with a more rugged section just beyond. The pine trees and snowcapped peaks on the horizon help give it an almost alpine feel. The gardens are decorated with fanciful fountains, most featuring mythological stories. However, the fountains run only on certain days (check the website for the schedule and entry details; when they’re running, you may need a ticket to enter the gardens).

The best places are on or near the central Plaza Mayor. This is where the city action is—the best bars, most tourist-friendly and típico eateries, and the TI. During busy times—on weekends and in July and August—reserve in advance.

$$$ Hotel Palacio San Facundo, on a quiet square a few blocks off Plaza Mayor, is luxuriously modern in its amenities but has preserved its Old World charm. This palace-turned-monastery has 29 colorful, business-class rooms surrounding a skylit central patio (air-con, elevator, pay parking, +34 921 463 061, Plaza San Facundo 4, www.hotelpalaciosanfacundo.com, info@hotelpalaciosanfacundo.com, Isabel).

$$ Hotel Real Segovia is a classic hotel (quick to brag about the many old-time movie stars who stayed here). They rent 37 beautifully updated rooms with all the modern amenities right along the main drag, between the aqueduct and Plaza Mayor. In spite of its central location, many of its rooms face the quiet countryside, and its top-floor terrace has some of Segovia’s best views (air-con, elevator, pay parking, Juan Bravo 30, +34 921 462 663, www.hotelrealsegovia.com).

$$ Hotel Infanta Isabel, right on Plaza Mayor, has 38 elegant rooms—some with plaza views—and a welcoming staff. It faces both the main square and a popular tapas bar-lined street—it’s smart to request a quiet room (air-con, elevator, pay parking, Plaza Mayor 12, +34 921 461 300, www.hotelinfantaisabel.com, admin@hotelinfantaisabel.com).

$ La Hostería Natura is a hostal with more personality. Their 18 colorful, tiled rooms—accessed by an old wooden staircase—are a few short blocks away from Plaza Mayor (air-con, Calle Colón 5, +34 921 466 710, www.naturadesegovia.com, info@naturadesegovia.com).

$$$ Hotel Eurostars Plaza Acueducto has little character but provides the comforts of a business-class hotel. It’s right at the foot of the aqueduct and next to the bus stops for the AVE train station. Some of its 72 rooms have full or partial views of the aqueduct (air-con, elevator, gym, pay parking; Avenida Padre Claret 2, +34 921 413 403, www.eurostarshotels.com, reservas@eurostarsplazaacueducto.com).

$ Hotel Apartments Aralso is a practical choice—a 10-minute hike below the aqueduct, near the bus station. This solidly built guesthouse in a workaday residential area rents 12 well-appointed, functional rooms with fully equipped kitchens. Sweetly run by André and María, it’s a good choice for those who don’t mind being a bit outside the creaky old center (family rooms, air-con, elevator, nearby pay parking, Calle Teniente Ochoa 8, +34 921 444 816, www.apartamentosaralso.com, reservas@apartamentosaralso.com).

$ Hostal Don Jaime, on a gentle hill just above the aqueduct, is a friendly, family-run place with 38 basic, older yet well-maintained rooms in two buildings (a few single rooms with shared bath, family rooms, breakfast included for Rick Steves readers, pay parking, Ochoa Ondategui 8, +34 921 444 787, www.hostaldonjaime.com, hostaldonjaime@hotmail.com).

Look for Segovia’s culinary claim to fame, roast suckling pig (cochinillo asado: 21 days of mother’s milk, into the oven, and onto your plate—oh, Babe). It’s salty and tender, wrapped in crispy skin that’s the stuff of pork-lovers’ dreams—and worth a splurge here, or in Toledo or Salamanca.

For slightly lighter fare, try sopa castellana—soup mixed with eggs, ham, garlic, and bread—or warm yourself up with the judiones de La Granja, a popular soup made with flat white beans from the region. Segovia also has a busy tapas bar scene, featuring small bites served up with every drink you order.

Ponche segoviano, a dessert made with an almond-and-honey mazapán base, is heavenly after an earthy dinner or with a coffee in the afternoon (at the recommended Limón y Menta).

While some of the places listed later also serve this classic local dish, these two are the most renowned options for those who really want to pig out in the old town.

$$$$ José María doesn’t have the history or fanfare of Cándido (see next), but Segovians claim this high-energy place serves the best roast suckling pig in town. It thrives with a hungry mix of tourists and locals. The bar leading into the restaurant is a scene in itself. Muscle up to the bar and get your drink and tapa before going into the dining room. It’s smart to reserve ahead (daily 12:30-24:00, air-con, a block off Plaza Mayor at Cronista Lecea 11, +34 921 466 017, www.restaurantejosemaria.com).

$$$$ Mesón de Cándido, one of the top restaurants in Castile, is famous for its memorable dinners. Even though it looks like a ye-olde tourist trap at the base of the aqueduct, it’s a grand experience. Take time to wander around and survey the photos of celebs—from Juan Carlos I to Antonio Banderas and Melanie Griffith—who’ve dined here. Try to get a table in a room with an aqueduct view (daily 13:00-16:30 & 20:00-23:00, reservations recommended, Plaza del Azogüejo 5, air-con, under aqueduct, +34 921 428 103, www.mesondecandido.es). Three gracious generations of the Cándido family still run the show.

Plaza Mayor, the main square, provides a great backdrop for a light lunch, dinner, or drink. Compare menus and views and choose your best. Things here are fairly interchangeable, and you’ll pay a premium for the location, but café prices are generally reasonable, and many offer a good selection of tapas and raciones. Grab a table at the place of your choice and savor the scene. Good options include $$$ Café Jeyma, with a great cathedral view (but the worst reputation for food); $$$ La Concepción Restaurante, closer to the cathedral; and $$$ Restaurante Bar José.

$$$ Narizotas mixes traditional Segovian fare with a few imaginative and non-Castilian alternatives. Dine outside on a delightful square or inside with modern art under medieval timbers. For a wonderful dining experience, try their chef’s-choice mystery samplers, either the “Right Hand” (€36, about nine courses) or the “Left Hand” (€31, about six courses). They offer less elaborate three-course meals for €14-25 and an enticing à la carte menu (daily 9:00-17:00 & 20:00-23:00, Fri-Sat until 24:00, midway down Calle Juan Bravo at Plaza de Medina del Campo 2, +34 921 462 679, www.narizotas.net).

$$ La Almuzara is a garden of veggie and organic delights: whole-wheat pizzas, pastas, tofu, seitan, and even a few dishes with meat (Tue 20:30-24:00, Wed-Sun 12:30-16:00 & 20:00-24:00, closed Mon, between cathedral and Alcázar at Marques del Arco 3, +34 921 460 622).

Segovia’s Trendy Tapas Strip: Many of the eateries described above have good tapas bars up front. But to sample several bars in one go, stroll down Calle de Infanta Isabel (angling off the Plaza Mayor). The places here skew young and trendy, but inside you’ll find a mixed-ages crowd. Divinos (at #12) has creative tapas in a cut-rate industrial-mod plywood atmosphere (sit in the dining room in back, rather than the less appealing bar up front). Farther along, El Sitio (#9) feels more traditional. This street also has several music and dance clubs that don’t get going until late.

Breakfast: In the morning, I like to eat on Plaza Mayor (many choices) while enjoying the cool air and the people scene. Or, 100 yards down the main drag toward the aqueduct, $$ Café La Colonial serves good breakfasts (with seating on a tiny square or inside, Plaza del Corpus).

Nightlife: After hours, the bars on Plaza Mayor, Calle de Infanta Isabel, and Calle de Isabel la Católica are packed. There are a number of late-night dance clubs along the aqueduct.

Dessert: Limón y Menta offers a good, rich ponche segoviano (marzipan) cake by the slice—or try the lighter, crunchy, honey-and-almond crocantinos (Mon-Fri 9:00-20:30, Sat-Sun until 21:00, seating inside, Calle de Isabel la Católica 2, +34 921 462 141).

Market: An outdoor produce market thrives on Plaza Mayor on Thursday (roughly 8:00-15:00). Nearby, on Calle del Cronista Ildefonso Rodríguez, a few stalls are open daily except Sunday. Carrefour Express, a small supermarket, is across from the Casa de los Picos (daily 9:00-21:00, Calle Juan Bravo 54).

From Segovia to Madrid: Choose between the fast AVE train and the bus. Even though the 30-minute AVE train takes less than half as long as the bus, the train stations in Segovia and Madrid are less convenient, so the total time spent in transit is about the same. (Skip the cercanías commuter trains, as they take two hours and don’t save you much money.)

The AVE train goes between Segovia’s Guiomar station (labeled “Segovia AV” on booking sites) and Madrid’s Chamartín station (up to 4/hour, 30 minutes). An Alvia train goes from the same station to Salamanca (4/day, 1.5 hours). To get to Guiomar station, take city bus #11 from the base of the aqueduct (20 minutes, buses usually timed to match arrivals).

Buses run from Madrid’s Moncloa station to Segovia. If arriving at Moncloa station in Madrid, follow the signs for the color-coded terminals to Terminal 1 (blue). From there, signs marked Taquillas Segovia lead you to the ticket office, or look for the ticket machines, which accept cash or chip-and-PIN credit cards (2/hour, 1.5 hours, www.avanzabus.com).

When riding the bus from Madrid to Segovia, about 30 minutes after leaving Madrid you’ll see—breaking the horizon on the left—the dramatic concrete cross of the Valley of the Fallen. Its grand facade marks the entry to the mammoth underground memorial.

From Segovia by Bus to: Ávila (4/day, 2/day on weekends, 1 hour, Avanza, www.avanzabus.com). Some Ávila buses continue to Salamanca (3.5 hours)—but the train is much faster.

From Segovia to Salamanca (100 miles/160 km): Leave Segovia by driving around the town’s circular road, which offers good views from below the Alcázar. Then follow signs for Ávila (road N-110). Notice the fine Segovia view from the three crosses at the crest of the first hill. You could stay on N-110 all the way to Ávila, but it’s cheap to hop on the speedy AP-51 tollway at Villacastín, about halfway to Ávila. If time allows, exit at Ávila for a look at the town walls and to stretch your legs. Continuing from Ávila to Salamanca, be ready to pull over for the best views of the Ávila walls: Just after you cross the river at the far end of the town wall, watch for the Cuatro Postes pullout on the right (it’s just uphill from the river). Soon after, hop on the speedy and free A-50 expressway, which zips you to Salamanca in under an hour.

About 20 miles before Salamanca, you’ll spot a huge bull on the left side of the road. As you get closer, it becomes more and more obvious it isn’t alive. (It’s not realistic to pull over for a photo if you’re on the expressway, but it’s reachable if you take the slower N-501.) Soon you’ll see the massive church towers of Salamanca on the horizon and enjoy great panoramic views of the city from across the river as you get closer.

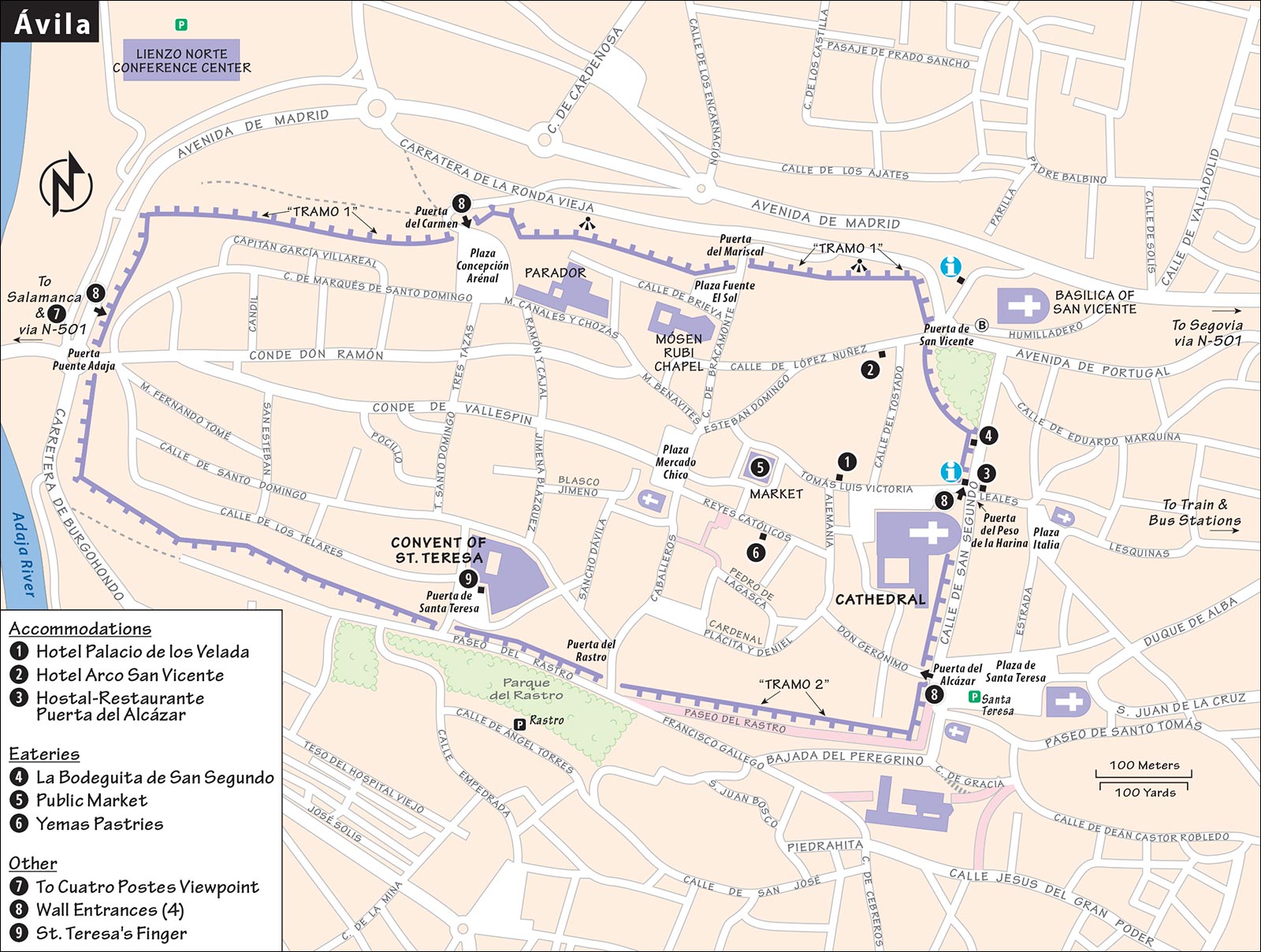

Ávila is famous for its perfectly preserved medieval walls, as the birthplace of St. Teresa, and for its yummy yema treats. For more than 300 years, Ávila was on the battlefront between the Muslims and Christians, changing hands several times—hence its heavily fortified appearance. But today, perfectly peaceful Ávila has a charming old town that weathers only occasional incursions of day-trippers from Madrid, Segovia, or Salamanca (each about an hour away by car). Ávila doesn’t quite crack the top tier of great walled European cities—it’s sort of a wannabe Carcassonne. But it’s handy to reach, has several fine churches and monasteries, and makes for an enjoyable quick stop between Segovia and Salamanca.

Surrounded by modern sprawl, Ávila’s walled old center is shaped like an elongated, backwards “D.” The flat side of the “D”—facing east—is where you’ll find the TIs, parking, and most of the sights (including two points to access the top of the walls). On a quick visit, most people focus on this busy little zone. Inside the walls, Ávila is sleepy: from the cathedral (which abuts the eastern wall), it’s a 10-minute walk on the main drag, Calle de los Reyes Católicos, past the market to the humble main square, Plaza Mercado Chico. A five-minute walk south of there is the only other important sight within the walls, the Convent of St. Teresa.

Tourist Information: Ávila’s city TI is just outside the northeast corner of the walls, facing the Basilica of San Vicente (daily 9:00-20:00, Nov-March until 18:00, free WCs, well-equipped shop, helpful wooden models of the town and important wall sections, +34 920 350 000 ext. 370, www.avilaturismo.com). A less helpful regional TI is inside the wall ticket office, near the cathedral (Mon-Sat 9:30-14:00 & 17:00-20:00, Sun 9:30-17:00, shorter hours mid-Sept-May, +34 920 211 387).

Sightseeing Pass: The VisitÁvila pass is €15 and valid for 48 hours. It includes the wall, cathedral, museum of St. Teresa, and a handful of other sights. If you plan on seeing them all you can save a few euros.

By Bus or Train: Ávila’s bus and train stations sit kitty-corner from each other about a mile east of the wall. There are lockers at Ávila’s bus station, but not at the train station. To reach the Basilica of San Vicente, you can walk (allow 15-20 minutes) or take city bus #4 or #1. From the bus station, exit to the right, go down through the underpass, and look right for the “Puente de la Estación” stop. To catch these buses from the train station, exit straight ahead to find the “Renfe” stop (to the right of the roundabout).

By Car: To get close to the sights, choose between two big, handy pay garages: Most convenient (and well-marked as you approach town) is the Sta. Teresa garage, a five-minute walk from the cathedral and main wall entry point, beneath Plaza de Santa Teresa (your license plate will be photographed as you enter; pay at the machine before you leave by punching in your plate number). The Rastro garage is just south of the city wall (use this only if you’re making a quick stop at the Convent of St. Teresa and nothing else). To save money, you could use the big, free lot behind the sprawling Lienzo Norte conference center, north of the city wall and farther from the main sights (20-minute walk to the cathedral). There’s also ample pay-and-display street parking outside of the walls (marked by blue lines), but there’s a two-hour limit—so this works only for a quick visit.

Built from around 1100 on even-more-ancient remains, Ávila’s fortified wall is the oldest, most complete, and best-preserved in Spain. Walking around the wall, climbing the towers, and peeking between crenellations is a fun stroll. But there’s not much to see up top—the views are better from ground level (and best from Cuatro Postes, across the river—see next). If it’s blazing hot and you’re short on time, the wall walk is skippable. But if you want to play “king of Castile”...it’s right there, waiting for you.

Cost and Hours: €5, includes audioguide, free Tue 14:00-16:00; open daily 10:00-20:00, July-Aug until 21:00; Nov-March Tue-Sat 10:00-18:00, closed Mon; last entry 45 minutes before closing, ticket includes English audioguide.

Walking the Wall: There are two stretches of wall that you can walk along (both covered by the same ticket—but you can’t re-enter a section you’ve already entered). The main section (called “Tramo 1”)—stretching eight-tenths of a mile, one way—is along the north side. Enter the wall by the gate closest to the cathedral (Puerta del Peso de la Harina). From here, you can head up to the northeast corner, then curve left and go all the way along the north side. There are two other entrances/exits for this stretch: Puerta del Carmen (about halfway along the north side) and Puerta Puente Adaja (on the far west end, opposite the cathedral). Go as far as you like. Then, either exit at one of those two points and return to ground level, or go back the way you came on top of the wall. The shorter section (“Tramo 2”), just about 300 yards one way, can be accessed at the Puerta del Alcázar, just off Plaza de Santa Teresa.

Viewing the Wall: The best views of the wall itself are actually from street level. If you’re wandering the city and see arched gates leading out of the old center, pop out to the other side and take in the impressive wall from the ground. Drivers can see the especially impressive north side as they circle to the right from Puerta de San Vicente.

Paseo Outside the Wall: An interesting paseo scene takes place along the outside of the wall each night—make your way along the southern wall (Paseo del Rastro) to Plaza de Santa Teresa for spectacular vistas across the plains.

The best overall view of the walled town of Ávila is about a mile away on the Salamanca road (N-501), at a clearly marked turnout for the Cuatro Postes (four posts). Drivers should keep an eye out on the right, after they cross the river and are on their way uphill. If you’re without wheels, you have a few options: You could walk or take a public bus to the far west end of the wall (to the bridge called Ponte de Allaja), then hike uphill for about 10-15 minutes to Cuatro Postes. Or you can catch a tourist trolley (€5.50, www.eltranvia.es) or tuk-tuk (€6.50, www.tuktukavila.com) for a little loop tour around town, which includes a sweat-free ride up to the viewpoint. All run infrequently—confirm your options at the TI.

While it started as Romanesque, Ávila’s cathedral, finished in the 16th century, is considered the first Gothic cathedral in Spain. Its position—with its granite apse actually part of the fortified wall—underlines the “medieval alliance between cross and sword.” The cathedral interior doesn’t rank very high on a Spanish scale (and even just in Ávila, San Vicente’s is more interesting). It’s heavy, stony, and bottom-heavy, with delicate Gothic windows illuminating a much lighter (and light-filled) top half. The focal point is the exquisitely carved outer stone wall of the choir (or “retrochoir”)—with Plateresque carvings of Jesus’ life. In the right transept, find your way into the sacristy, cloister, and museum (including a minor painting by El Greco).

Cost and Hours: €6, includes audioguide, Mon-Sat 10:00-21:00, Sun from 11:45, generally closes 2-3 hours earlier off-season, Plaza de la Catedral.

Tower: You can pay €2 for an assigned time, then climb the 130 spiral stairs of the cathedral tower, earning a great panoramic view over Ávila (1-3/day, more in July-Aug, Sat-Sun only in winter).

Sitting just outside the northeast corner of the wall (facing the TI), this hulking church—with its distinctive Romanesque-arch arcade facing the busy street—is worth a peek. The 12th-century interior oozes history, with rough tombstones embedded in the floor, heavy columns framing round windows, a glittering altarpiece, and a huge, canopied, colorfully painted tomb holding three local fourth-century martyrs.

Cost and Hours: €2.50, includes audioguide, Mon-Sat 10:00-18:30, Sun 16:00-18:00, off-season closed for lunch 13:30-16:00.

Built in the 17th century on the spot where the saint was born, this convent is a big hit with pilgrims (10-minute walk from cathedral). St. Teresa (1515-1582)—reforming nun, mystic, and writer—bought a house in Ávila and converted it into a convent with more stringent rules than the one she belonged to. She faced opposition in her hometown from rival nuns and those convinced her visions of heaven were the work of the devil. However, with her mentor and fellow mystic St. John of the Cross, she established convents of Discalced (shoeless) Carmelites throughout Spain, and her visions and writings led her to sainthood (she was canonized in 1622).

Inside the humble convent church, a lavishly gilded side chapel marks the actual place of her birth (left of main altar, door may be closed).

The finger is housed in the little Sala de Reliquias at the back of the church shop (as you face the church, it’s on your right). You’ll see Teresa’s finger, complete with a fancy emerald ring, along with one of her sandals and two bones of St. John of the Cross.

A museum dedicated to the saint is in the crypt (around the left side as you face the church). Inside under heavy stone vaults, you’ll see a wide collection of items relating to Teresa, including replicas of her spartan bedroom and items she might have used. There’s also an extensive collection of books, portraits, stamps, and coins of St. Teresa—helping explain why this woman and this convent are so important to so many people around the world.

Cost and Hours: Convent—free, daily 10:00-13:30 & 17:00-19:00, no photos of finger allowed; museum—€2, Tue-Sun 10:00-14:00 & 16:00-19:00, shorter hours off-season, closed Mon year-round.

These pastries, made by local nuns, are more or less soft-boiled egg yolks that have been cooled and sugared (yema means yolk). They’re sold all over town. The shop Las Delicias del Convento is a retail outlet for the cooks of the convent (€4 for a small box, Mon-Sat 10:30-20:00, Sun until 18:00, between the TI and convent at Calle de los Reyes Católicos 12, +34 920 220 293).