CHAPTER 2

The Global Trade

Carousel 1400–1800

‘World economic integration’ is as significant a fact of organized life in earlier centuries (despite all appearances to the contrary) as it more obviously is in the days of instant computerized markets…. We must conclude that major changes involve transitions informs of integration and not, as is alleged, the emergence of integration itself…. The history of the world should not be characterized as a movement from locally constituted closures toward increasing world integration and homogenization…. The conventional notion of ‘diverse cultures’ being ‘penetrated’ by emergent universalist forces is misfounded…. Whether in the ninth and tenth centuries, twelfth and thirteenth centuries, or seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the world has always been complex in its connectedness…. The continuum of medieval and early-modern times has no single centre, not even a handful of particular centres conceived as the sources affecting integration. Instead, its character is prolific multicentredness.

Frank Perlin (1994: 98, 102, 104, 106)

An Introduction to the World Economy

The major thesis of this book is that, contrary to widespread doubts and denials, there was a single global world economy with a worldwide division of labor and multilateral trade from 1500 onward. This world economy had what can be identified as its own systemic character and dynamic, whose roots in Afro-Eurasia extended back for millennia. It was this world political economic structure and its dynamic that had motivated Europeans to seek greater access to the economically dominant Asia ever since the European Crusades. The same Asian magnet led to the “discovery” and incorporation of the Western Hemisphere “New” World into the Old World economy and system after the 1492 voyage of Columbus and to closer European-Asian relations after the 1498 circum-African voyage of Vasco da Gama. An alternate route to China via the Northwest Passage around and/or through North America—and also eastward through the Arctic Sea—continued to be eagerly sought for centuries thereafter.

The world economy continued to be dominated by Asians for at least three centuries more, until about 1800. Europe's relative and absolute marginality in the world economy continued, despite Europe's new relations with the Americas, which it used also to increase its relations with Asia. Indeed, it was little more than its new and continued access to American money that permitted Europe to broaden, though hardly to deepen, its participation in the world market. Productive and commercial economic activities, and population growth based on the same, also continued to expand faster and more in Asia until at least 1750, as this and the following two chapters document.

This chapter oudines the globe-encircling pattern of world trade relations and financial flows, region by region. The examination of the structure and operation of these global economic relations will demonstrate the existence of a world market in the early modern period beyond a reasonable doubt. My insistence on the same is intended to counter the widespread neglect and even frequent denial of the existence of this world economy by so many other students of that period. Indeed, it has recently become fashionable to claim that the world economy is only now undergoing “globalization.” Moreover, the explicit denial, not to mention neglect, of the early modern world market and its underlying division of labor is still the mistaken basis of much historical research and social science theory about the “European world-economy” by Braudel and the “modern world-system” by Wallerstein and by their many disciples, not to mention their detractors like O'Brien, cited in chapter 1.

An “intercontinental model” of world trade between 1500 and 1800 on the basis of interregional competition in production and trade was proposed by Frederic Mauro (1961). However, its early existence was already observed by Dudley North in 1691: “The Whole World as to Trade, is but one Nation or People, and therein Nations are as Persons” (quoted in Cipolla 1974: 451). Moreover, this world market and the flow of money through it permitted intra- and intersectoral and regional divisions of labor and generated competition, which also spanned and interconnected the entire globe:

The records show that there was competition…between alternative products, such as East Indian and European textiles; between identical products from different regions enjoying similar climates, e.g., sugar from Java and Bengal, sugar from Madeira and Sao Tome, and Brazilian and West Indian sugar; or between products grown in different climatic regions, as in the case of tobacco…. Chinese, Persian and Italian silk; Japanese, Hungarian, Swedish and West Indian copper; the spices of Asia, Africa and America; coffee from Mocha, Java and the West Indies: all of these competed…. The best barometer, however, is represented by the prices on the commodity exchange of Amsterdam. (Cipolla 1974: 451)

The Amsterdam that Cipolla singles out may have been the best market price barometer for a time, but that should not be confused with the climate itself and the ups and downs in its economic and financial weather, which were worldwide. Of course, the global inter- and intraregional competitive and complementary or compensatory division of labor went far beyond Cipolla's few examples. For instance, Rene Barendse observes regarding the Arabian Sea and the operation of the Dutch East India Company (or VOC, from its commonly used Dutch initials) there and elsewhere that

The production was centralized on places where the costs of labour were lowest. This, not primarily low transport-costs, explains [that]…comparative cost-advantages were pulling Asian and American markets together—no matter what mercantilist restriction. Another case was the substitution of Indian, Arab and Persian products like indigo, silk, sugar, pearls, cotton, later on even coffee—the most profitable commodities traded in the Arabian seas in the late seventeenth century—by goods produced elsewhere; generally the American colonies…. Due to this global process of product-substitution, by 1680 the transit-trade of the Arabian seas with Europe had disappeared or was in decline; this was for a brief period cushioned by the rise of the coffee-trade. But it contributed to a prolonged depression in the commerce between the Gulf, the Red Sea and the Indian west coast. This decline of transit-trade was smoothed by internal trade within the Arabian seas. But the Middle East had to pay for imports from India by selling bulk products in the Mediterranean, like grain or wool. A precarious balance…spawned an inflationary pull both on the Ottoman and the Safavid currency. (Barendse 1997: chap. 1)

These globe-encircling world market relations and their underlying division of labor and its resulting (im) balances of trade are outlined in this chapter and illustrated in the accompanying maps.

In the “regional” accounts of this chapter, we repeatedly see how the changing mix and selection of crops, or indeed the replacement of “virgin” forested land by crops, and the choice of manufactures and the commercialization of all of the above responded to local incentives and exigencies. We observe in both this and the following chapter how that resulted in the clearing of the jungle in Bengal and the deforesting of land in southern China. As a result, land, rice, sugar, silk, silver, and labor were exchanged for each other and timber or its products, which were then imported from Southeast Asia. However, we also see how many of these local and sectoral incentives were transmitted by regional and interregional market forces. Many of these in turn emanated from competitive or compensatory activities on the opposite side of the globe. Indeed, some of these pressures met, say in a village in India or China, after being simultaneously transmitted halfway around the globe in both eastward and westward directions, as well as in additional crisscross directions. Of course as chapter 6 stresses about Europe as well, the import of sugar from the Americas and of silk and cotton textiles from Asia supplemented the local production of food and wool and liberated forest and cropping land; thus the extent to which “sheep ate men” and men ate at all was also a function of the world market.

The wheels of this global market were oiled by the worldwide flow of silver. In chapters 3 and 6 we see how it was only their newfound access to silver in the Americas that allowed the Europeans even to participate in this expanding world market. More detailed attention to how the production and flow especially of silver money stimulated and extended production and trade around the globe is reserved for chapter 3, which demonstrates how the arbitraged interchange of different currencies and other instruments of payment among each other and with other commodities facilitated a world market for all goods. All this trade was of course made possible only by commonly acceptable forms of money and/or the arbitrage among gold, silver, copper, tin, shells, coins, paper money, bills of exchange, and other forms of credit. These had been in circulation across and around Afro-Eurasia for millennia (and according to some reports, also across the Pacific especially between China and the Western Hemisphere). Nonetheless, the incorporation into this Old World economy of the New World in the Americas and their contribution to the world's stocks and flows of money certainly gave economic activity and trade a new boost from the sixteenth century onward.

THIRTEENTH-AND FOURTEENTH-CENTURY

ANTECEDENTS

Two recent books begin to offer a non-Eurocentric alternative reading of early modern world history. They are Janet-Abu-Lughod's (1989) Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250– 1350 and N. K. Chaudhuri's (1990a) Asia Before Europe, which peruses its theme to 1750. Abu-Lughod offers an especially suitable point of departure for the analysis of the present book. She argues that eight interlinking city-centered regions were united in a single thirteenth- century Afro-Eurasian world system and division of labor. The eight interlinked regions are categorized as three related and interlocked subsystems: (1) the European subsystem, with the Champagne fairs, industrial Flanders, and the commercial regions of Genoa and Venice; (2) the mideastern heardand and its east-west routes across Mongol Asia, via Baghdad and the Persian Gulf, and through Cairo and the Red Sea; and (3) the Indian Ocean-East Asian subsystem of India, Southeast Asia, and China. Their major fortunes and misfortunes, as well as the mid-fourteenth-century crisis and the Black Death epidemic, were more or less common to all of them.

Europe was “an upstart, peripheral to an ongoing operation” in Asia, so that “the failure to begin the story early enough has resulted…in a truncated and distorted causal explanation for the rise of the west,” rightly insists Abu-Lughod (1989: 9, 17). Indeed she sees Europe's own twelfth- and thirteenth-century development as at least in part dependent on trade with the eastern Mediterranean, which had been generated by the Crusades. These in turn would not even have taken place or would have been fruidess, had it not been for the riches of “the Orient.” Indeed, the trade, industry, and wealth of Venice and Genoa were due primarily to their middlemen roles between Europe and the East, some of which the Italian cities had preserved even through the Dark Ages. During the periods of economic revival after A.D. 1000, both tried to reach into the trade and riches of Asia as far as they could. Indeed, Genoa attempted in 1291 to reach Asia by circumnavigating Africa.

Failing that, Europe had to make do with the three major routes to Asia that departed from the eastern Mediterranean: the northern one through the Black Sea, dominated by the Genovese; the central one via the Persian Gulf, dominated by Baghdad; and as its replacement, the southern one through the Red Sea, which gave life to Cairo and its economic partner in Venice. The expansion of the Mongols under Genghis Khan and his successors cemented the decline of the middle route after the capture of Baghdad in 1258 and favored the southern one. The Mongols then controlled the northern route onward from the Black Sea and also promoted the trans-Central Asian routes through such cities as Samarkand, which prospered under Mongol protection. Yet all of these trade routes suffered from the long world economic depression between the mid-thirteenth-century and the end of the fourteenth century, of which the Black Death was more the consequence than the cause (Gills and Frank 1992; also in Frank and Gills 1993). The economic determinants of this growing and ebbing trade, production, and income, however, lay still farther eastward in South, Southeast, and East Asia. As we will observe below, a long cyclical economic revival began there again around 1400.

But before that, according to Abu-Lughod's (1989) reading, this world system experienced its apogee between 1250 and 1350 and declined to (virtual) extinction thereafter and was then reborn in southern and western Europe in the sixteenth century. In her words, “of crucial importance is the fact that the ‘Fall of the East’ preceded the ‘Rise of the West’” (Abu-Lughod 1989: 388). We must agree with the latter statement but not with her timing nor with her claim that there was no continuity between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries in a single world economy and system. I have criticized Abu-Lughod's interpretation of the “substitution” of one “system” by another, rather than the “restructuring” of the same system elsewhere (Frank 1987, 1991a, 1992, Frank and Gills 1993), and she has answered (Frank and Gills 1993). We may now take up our examination of the global world economy and system where Abu-Lughod's account ended around 1400.

The world economy was predominantly Asian-based and so were the economic enterprise and success of Venice and Genoa, both of which derived their wealth from their intermediary position between the riches of Asia and the demand for the same in Europe. Their trade with the western terminus of Asian trade in West Asia, from the Black Sea, via the Levant to Egypt was also the precursor of European expansion into the Atlantic Ocean and eventually down it around Africa to India and across it to the Americas, also in search of Asia. The reasons for the voyages of Columbus in 1492 and of Vasco da Gama in 1498 have been long debated. These events were not accidental. After all, Columbus “discovered” America because he went in search of markets and gold in East Asia. That happened when a growing bullion shortage and the consequent rise in the Afro-Eurasian world market price of gold made such an enterprise attractive and potentially profitable (which it turned out to be). As John Day, admittedly a monetarist, writes

The problem [of specie shortages], in the long run, engendered its own solution. Rising bullion prices, the corollary of contracting stocks, largely account for the intensified prospecting for precious metal all over Europe, as well as the ultimately successful search for new techniques of extraction and refining. And it was the acute “gold fever” of the fifteenth century that was the driving force behind the Great Discoveries which would end by submerging the money-starved European economy with American treasure at the dawn of modern times. (Day 1987: 63)

Moreover, Iberian access to that treasure was blocked not so much by the oft-heralded Muslim expansion and the advance of the Ottomans and their capture of Constantinople in 1453, as has often been alleged. Probably more important were Venetian and Genovese competition on the trade routes through the eastern Mediterranean, Genovese interests in Iberia, and their attempts to circumvent the Venetian stranglehold on commerce through Egypt. That is the significance, Lynda Shaffer (1989) points out, of the oft-quoted observation by the Portuguese Tome Pires that “whoever is lord of Malacca has his hands on the throat of Venice.” Recall that Columbus was Genovese, first offering his services to Portugal to open a new route to the Orient, and only later accepting Spanish patronage.

Moreover, whatever the immediate incentives for the voyages of Columbus, Vasco da Gama, and then Magellan and the others, they had a long-standing and widely shared European impulse. As K. M. Panikkar (1959: 21–22) insists, “the full significance of da Gama's arrival at Calicut can be recognized only if we appreciate that it was the realization of a 2oo-year-old dream and of seventy-five years of sustained effort. The dream was shared by all mercantile peoples of the Mediterranean, with the exception of the Venetians; the effort was mainly that of Portugal.” However, C. R. Boxer (1990: ix) quotes an official 1534 Portuguese document which observed that “many people…say that it was India which discovered Portugal.” We will have further occasion to reflect on this European enterprise regarding Asia in chapters that follow. Here we shall proceed to examine some of the results.

THE COLUMBIAN EXCHANGE

AND ITS CONSEQUENCES

Three major consequences of the 1492 and 1498 voyages and their subsequent migratory and trade relations merit more attention than the brief reference they can receive here. The first two are “the Columbian exchange” of germs and of genes and “ecological imperialism,” as Alfred Crosby (1972, 1986) has termed them. The germs that the Europeans brought with them were by far their most powerful weapons of conquest. They were most devastating in the New World, whose population had no immunities to the disease germs the Europeans brought with them. This devastation is described by, among others, Crosby (1972, 1986) as well as by William McNeill in his Plagues and People (1977). In the Caribbean, almost the entire indigenous tribal population was wiped out in less than fifty years. On the continent, the germs of disease were carried faster, further, and far more devastatingly than the conquering troops of Cortez and Pizarro, who found that the smallpox they brought on shore preceded them inland. The new weeds and animals they also brought spread their damage more slowly.

In the New World of the Americas, the consequences were devastating. The populations of the Mesoamerican Aztec and Maya civilizations were reduced from about 25 million to 1.5 million by 1650. The Andean Inca civilization fared similarly, with a population decline from perhaps 9 million to 600,000 (Crosby 1994: 22). In North America also, the germs brought by the first European arrivals, probably in 1616–1617, cleared the land of many indigenous inhabitants even before the bulk of the settlers arrived. One estimate for the ultimate European impact in the United States is a decline of the indigenous population from 5 million to 60,000 before it began to rise again. Some estimates suggest a population decline in the New World as a whole from some 100 million to about 5 million (Livi-Bacci 1992: 51).

Even in nomadic Inner Asia, the Russian advance through Siberia would be spurred on by the germs of the soldiers and settlers as much as by their other arms. As Crosby (1994: 11) observes, “the advantage in bacteriological warfare was (and is) characteristically enjoyed by people from dense areas of settlement moving into sparser areas of settlement.” On the other hand, the transfer of germs within Afro-Eurasia never caused population declines on a scale remotely comparable to the population decline in the Americas initiated by the new transatlantic contacts. The reason of course is the much greater immunity the peoples of Afro-Eurasia had already inherited from their many generations of mutual contacts through prior invasion and migration as well as long-standing trade. Similarly, the relatively greater impact of the Black Death on Europe had also been a reflection of the isolation and marginality of Europe within Eurasia.

The Columbian gene exchange involved not only humans but also animals and vegetables. Old World Europeans introduced not only themselves but also many new animal and vegetable species to the New World. The most important animals, but by no means the only ones, were horses (which had existed there previously but had died out), cat-de, sheep, chickens, and bees. Among vegetables, Europeans brought wheat, barley, rice, turnips, cabbage, and lettuce. They also brought the bananas, coffee, and, for practical purposes if not genetically, the sugar that would later dominate so many of their economies.

Through the Columbian exchange, the New World in turn also contributed much to the Old World, such as animal species like turkeys as well as many vegetables, several of which would significantly extend cropping and alter consumption and survival in many parts of Europe, Africa, and Asia. Sweet potatoes, squash, beans, and especially potatoes and maize vastly increased cropping and survival possibilities in Europe and China, because they could survive harsher climates than other crops. The absolute and probably the relative impact was greatest on new crops in the more populated China where New World crops contributed to doubling agricultural land and tripling population (Shaffer 1989: 13). The growing of sweet potatoes is recorded in the 1560s in China, and maize became a staple food crop in the seventeenth century (Ho Ping-ti 1959: 186 ff.). White potatoes, tobacco, and other New World crops also became important. Indeed as we note below, the resultant population increase was far greater in China and throughout Asia than in Europe. Today 37 percent of the food the Chinese eat is of American origin (Crosby 1996:5). After the United States, China today is the world's second largest producer of maize, and 94 percent of the root crops grown in the world today are of New World origin (Crosby 1994: 20). In Africa, subsistence was extended especially by cassava and maize, along with sunflowers, several nuts, and the ubiquitous tomato and chili pepper. Later Africa also became a major exporter of cacao, vanilla, peanuts, and pineapple, all of which were of American origin.

Of course, the third major consequence of the Columbian exchange was the New World's contribution of gold and silver to the world's stocks and flows of money, which certainly also gave a new boost to economic activity and trade in the Old World economy from the sixteenth century onward. These flows are examined in detail in chapter 3, but some of their consequences for trade flows and balances are reviewed in the present chapter.

SOME NEGLECTED FEATURES

IN THE WORLD ECONOMY

Several features of the interregional world trade network deserve special preliminary comment (though they cannot receive as much attention in this summary as they probably merit in reality). They are regionalism, trade diasporas, documentation, and ecology.

The identification of “regions” below—”the Americas,” “Europe,” “China”—is in part an arbitrary heuristic notational convenience and in part a reflection of reality, as Lewis and Wigen (1997) stress under the title The Myth of Continents. There have been and are regions in the world, within whose “boundaries” the division of labor and the density of trade relations is greater than across them. That greater “internal” than “external” density of trade relations may be due to geographic factors (mountains, deserts, or seas that divide and therefore also bound), political ones (the reach and cost of empires and their competition with each other), cultural factors (ethnic and/or religious affinity and language), and other factors, or any combination thereof. The bounding of the grouping depends on the purpose and changes from time to time, sometimes very suddenly. The regional “unit” or “group” may be an individual, a nuclear or an extended family, a village or town, a local “region,” a “society,” a “country,” a “regional” region (the circum-Mediterranean), or a “world” region (the Americas, West Asia, Southeast Asia, the South Pacific). The very mention of these examples illustrates how ill-defined (indeed ill-definable) and fluid these “regional units” are and how arbitrary their identification is. The same exercise also serves to emphasize that the intra-regional ties, no matter what their density, are no obstacle to having inter-regional ones as well. Indeed, what is intra- or interregional is itself a function of how we identify the region or regions to begin with. If the world is a “region,” then all are intrarelations. Similarly, the assertion that there is or was a world economy/system does not dispute that it is or was also composed of regional ones. Where, what, and when such regions existed, however, all depends.

So whether the Americas, or Europe, or Southeast Asia, or China were “regions” in our 1400–1800 period or not depends on our definitions. Intra-American trade, not to mention cultural affinity and contact or political relations, were surely less among most Western Hemisphere “subregions” than they were between each of them and one or another part of Europe. Some parts of Europe also had less relations among themselves than they did with peoples and areas in the Americas and Asia. On the other hand, perhaps most major regions (or, subregions?) on the Indian subcontinent or within “China” probably had denser intra-Indian or intra-Chinese interregional trade (also outside the changing confines of the Mughal and Qing empires) than they did with other parts of the world. (There are some observations about Indian intra- and interregional trade below and in the maps). However, parts of Southeast Asia, especially Manila and Malacca, and also Aden and Hormuz in West Asia, were entrepots whose sixteenth- and seventeenth- century trade relations with many other parts of the world were greater than those with their own essentially nonexistent “regional” hinterlands.

Another notable but related feature of interregional trade in the world economy were the expatriate merchant and trade diasporas. They had already played important roles in the facilitation of trade in the Bronze Age and certainly did so in the early modern period. They also continue to do so today, as is testified by the “overseas” Chinese who now invest on the mainland and by expatriate Japanese and American “colonies” and even their “local” newspapers like the International Herald Tribune, a U.S. periodical originally published in Paris and now printed in a dozen cities around the world.

In the period under review, Malacca was peopled almost entirely by expatriate merchants, so much so that Pires counted eighty-four different languages spoken among them. Maharatshi merchants from Cambay and Surat were probably the most numerous in Malacca, but they were also residents—not to mention seasonal arrivals—in dozens of other port cities in Southeast, South, and West Asia. Manila counted up to 30,000 Chinese residents in the seventeenth century to oil the wheels of the transpacific-China silver and porcelain trade. Armenians from a landlocked country in western Central Asia established an also landlocked trade diaspora base in the Safavid Persian city of Isfahan, used it to trade all across Asia, and published an Armenian how-to-do-it handbook in Amsterdam. Arab and Jewish merchants continued to ply their worldwide trade as they had for at least a millennium and continue to do so today. New Englanders not only sought Moby Dick and other whales throughout the world oceans; they also plied the slave trade between Africa and the Caribbean, and they regularly buccaneered off the coast of Madagascar. Thousands if not millions of Chinese—not to mention Muslim trading expatriates, who “indianized” Southeast Asia—migrated overseas. Central Asia also continued to be a crossroads for itinerant merchants and migrating peoples, as it had from time immemorial.

Ironically, most of the still-extant documentary evidence on Asian trade comes from private European companies, who of course only recorded what was of commercial or other interest to them, especially in regard to these trade diasporas. Therefore much of the evidence on Asian production and trade fell through the European cracks. This is particularly the case with the inland economies and the transcontinental caravan trade, which the Europeans hardly saw. However, there is reason to believe that they were fully as important as, and complementary to, the maritime trade throughout this entire period up to 1800.

All this “development” also had other far-reaching impacts, which recent studies call ecological or green imperialism. A major consequence has been widespread deforestation, both to make way for new cropland and to provide timber for shipping and other construction and even more wastefully for charcoal for smelting ores and refining metals and for other fuel (Chew 1997, and forthcoming). On the other hand, planting potatoes and maize presumably relieved pressure on land more suitable for other crops. And New World sugar supplied calories to Europe that it did not have to provide for itself. Later of course, imports of wheat and meat from the New World fed millions of Europeans and permitted them to put their scarce land to other uses, as did the import of cotton, replacing wool from sheep that had grazed enclosed land. We will return to the matter of ecological imperialism in some of the regional reviews below and again in chapter 6.

World Division of Labor and Balances

of Trade

Of course, there were some abrupt and then secular changes in interregional relations, particularly because of the incorporation of the Americas by Europeans and the consequent growing participation of Europe in Afro-Eurasian and world trade from the sixteenth century onward. There were also—in other contexts important—cyclical changes, some of which are examined in Frank (1978a, 1994, 1995) and in chapter 5 below. Moreover, there was the rise to dominance of Europe beginning at the end of the eighteenth century, which we analyze in chapter 6. By and large however, the pattern of world trade and division of labor remained remarkably stable and displayed a substantially continuous, albeit cyclical, development over the centuries, if not millennia (as examined for the period before 1400 in Gills and Frank 1992; also in Frank and Gills 1993). There was certainly sufficient continuity in the period 1400–1800 to recognize the pattern outlined below.

MAPPING THE GLOBAL ECONOMY

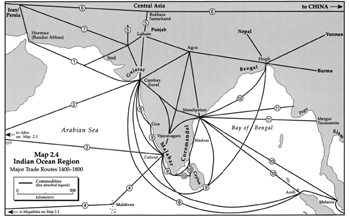

A schematic and incomplete mapping and summary of the global division of labor, the network of world trade with its balances and imbalances, and how they were settled by flows of money in the opposite direction is set out in the maps and their legends below. It seems most efficient to use maps to identify some of the large variety of commodities—including many bulk commodities such as rice—that were exchanged in a complex network of trade in the world division of labor between about 1400 and 1800. The most schematic and least detailed world economic overview is in map 2.1.1 have chosen a “Nordic/ polar” global projection to permit a summary representation of circumglobal trade, including particularly the shipments of silver across the Pacific on the Manila Galleons. The reader should be aware however that to simplify and clarify their presentation, all trade routes on this and the following regional maps are only schematic. They do not pretend to be accurate, even if an effort was made to reflect global and regional geographical realities as well as the schematic representation permits. Moreover, contrary to the tide and message of this book, the global Map 2.1, like map 3.1, is not oriented toward Asia as I wished. The reason is that my cartographer's university geography department in Western Canada did not have a less Eurocentric sample map to guide his computerized design, and even his cartographic software is not flexible enough to meet my request to spin this one just a little on its polar axis in order to reorient the map. So here we have yet another example of how difficult but therefore also how necessary it is to reorient. Related problems in the representation of land mass and distance appear on the regional maps; for instance, India appears smaller and regions to its north and south relatively larger than they are in reality.

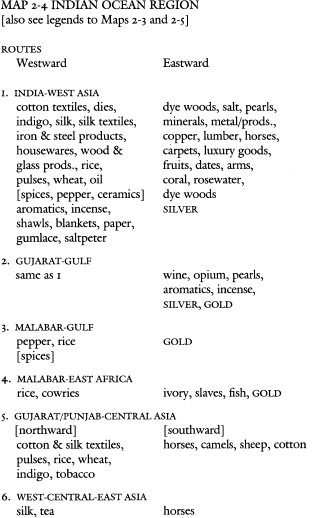

The regional maps and their respective legends present in more detail the major regional and interregional trade routes. Map 2.2 represents the Atlantic region, including the Americas, Africa, and Europe, Map 2.1 with their famous “triangular” trades along with the important transatlantic shipments of silver from the Americas to Europe. Map 2.3 overlaps with the previous one and features the major trade routes between Europe and West, South, and Central Asia, both around the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa and through the Baltic and Red seas and the Persian Gulf. Map 2.4 details the continuation of these major East-West trade routes through the Indian Ocean (and Arabian Sea), whose maritime trade connected East Africa and West Asia with South and Southeast Asia. However, the same map also shows some of the important overland caravan routes across parts of West and Central Asia and between them and South Asia, which, as the text below will insist, were more complementary to than competitive with the maritime routes. The western part of map 2.5 also overlaps with the previous one but features the major Bay of Bengal and South China Sea trade routes between India, Southeast Asia, Japan, and China as well as their connection with the transpacific trade at Manila. However, it is also intended to emphasize maritime and overland trade among the various Indian regions like Punjab, Gujarat, Malabar, Coromandel, and Bengal as well as the oft-neglected overland trade between China and Burma, Siam, and Vietnam in continental Southeast Asia as well as with India.

Map 2.1 Major Circum-Global Trade Routes, 1400 - 1800

These four regional maps are constructed also to illustrate the major interregional imbalances of trade and how they were covered by shipments of silver and gold bullion. Therefore, these maps represent commodity trade routes by solid lines, which are numbered from 1 to 13 and are accompanied by correspondingly numbered legends that list the major commodities traded along each of these major routes. Chronic trade deficits, resulting from insufficient exports of commodities to cover imports of others had to be paid for and balanced by corresponding exports of gold and mostly silver bullion or coin. This chapter and the next (on money) emphasize the predominant eastward flow of silver—and profit from the export of bullion or coin itself—to balance the trade deficits that most westerly regions maintained with those farther to the east. The global overview map 2.1 represents this flow of mostly silver by eastward-pointing arrows, except westward-pointing ones from the Americas and Japan to China, placed on the commodity trade lines themselves.

The regional maps use a different convention: silver flows and their directions are represented by dashed lines and gold flows by dotted lines parallel to the solid, numbered ones representing commodities. Therefore, an eastward-pointing arrow on a dashed line of silver exports also indicates a predominant reverse commodity export surplus from east to west along the parallel solid line representing a commodity trade route. In particular, almost all European imports from the east were paid for by European exports of (American) silver. This is represented by the dashed lines with eastward-pointing arrows between Western Europe and the Baltics as well as West Asia, and from these regions onward successively to South, Southeast, and eventually East Asia, that is predominantly China. That was the “sink” for about half of the world's silver, as will be shown in chapter 3, which offers a separate map of major world silver production and flows.

Multilateral world trade around the globe is also discussed region by region in this chapter, beginning with the Americas and proceeding eastward around the globe. As we visit each major region in the world, we will note some of the specificities of each region and how these intervene in and help generate its relations with other regions, particularly those immediately to the west and east.

The net export of silver and/or gold bullion and coins is evidence of a negative, or deficitary balance of trade, except perhaps in some cases where the exporter is also a producer and commercial exporter of precious metals (for example, American and Japanese silver and African and Southeast Asian gold). Records of the shipment and remission of bullion and/or coin therefore offers the most readily available evidence of interregional trade deficits and surpluses, and of how these were settled and balanced. Unfortunately, we know less about the undoubtedly also very extensive use of bills of exchange and letters or other instruments of credit.

Europe, the Americas, and even Africa will receive relatively short shrift in this review for the following good reasons: First, as we have noted above, their economic weight, participation, and importance in the world economy (except for the exceptional role of American money distributed by the Europeans), was far less than that of many other regions in the world, in particular of East and South Asia, but probably also of Southeast and West Asia. Second, the available historical, economic, and social literature has already devoted an immense amount of ink and attention to Europe and the Americas, and of the relation of Africa to both, which is all out of proportion to their relatively small importance in the world economy before 1800. Moreover, far too much of the literature (including Frank 1978a, b) has been written from an excessively Eurocentric perspective, which the present book is intended to help correct and replace. Therefore it seems only right and proper to focus on those other regions and their relations that have been neglected out of all proportion to their real weight and importance. That is not to say, of course, that this modest effort here can hope thereby to right the wrongs that have been done. The third reason for giving short shrift to Europe, the Americas, and Africa is that the purpose here is not so much to right such wrongs by examining different “regions”; their identification is in any case arbitrary, as was noted above. The more important purpose is to demonstrate the nature, kind, and changes in the relations among these regions.

Thus, the real object and fourth reason for the choices made below is to add to a basis for the inquiry into the structure and dynamic world economy and system as a whole. As cannot be repeated often enough, it is the whole (which is more than the sum of its parts) that more than anything else determines the “internal” nature of its parts and their “external” relations among each other. So we begin our historical around- the-world-in-eighty-pages by going predominantly eastward around the globe, starting in the Americas but always keeping this holistic perspective in mind.

THE AMERICAS

We have already examined the reasons for the “discovery” and incorporation of the Americas into the world economy and the impact on its native peoples, beginning with their population decline from about 100 million to 5 million people. For the rest of the world, the early impacts were mostly the Americas” contribution of new plants, the export of plantation crops, and of course the production and export first of gold and then of large amounts of silver. Gold exports started from the “discovery” in 1492 and large-scale silver exports by the mid-sixteenth century. To what extent this American production and export of silver declined, only slackened off, or indeed even increased during the seventeenth century has been the subject of much debate. Either way, production and trade appears to have continued to increase during the “seventeenth century crisis,” either despite (or perhaps because of?) less stimulus from European-supplied American money or making still better use of its supply. During the eighteenth century, the production and export of bullion increased again (or continued its rise still farther), and so did the production and trade of other goods around the world.

Over these same centuries and especially during the eighteenth century, the well-known “triangular” trade across the Atlantic developed into a significant adjunct of the Afro-Eurasian trade and the world economic division of labor (see map 2.2). Actually, there were several related transatlantic triangles in operation. The most important one coordinated European, and especially British, manufacturing exports, including many re-exports of textiles and other goods from India and China to the Americas and Africa; African exports of slaves to the Caribbean and the South and North American slave plantations; and primarily Caribbean exports of sugar and secondarily North American exports of tobacco, furs, and other commodities back to Europe. In the seventeenth and even more the eighteenth centuries, North America, the Caribbean, and Africa also became ever more important export markets (which were still not available in Asia) for European manufactures, including especially guns to Africa for use in rounding up the supply of slaves. There was also a large European re-export of Asian goods, especially of Indian textiles to Africa, the Caribbean, but also to the Spanish colonies in Latin America.

However, there were also other related triangles, which involved particularly the North American colonies as importers of sugar and molasses from the Caribbean in exchange for exports of grain, timber, and naval stores to the latter and the export to Europe of rum produced with the imported molasses. The most important secondary trade in these triangular trades, however, was trade itself, including shipping, financial services, and the slave trade. The earnings from this trade served especially the American colonists to cover their perennial balance of trade deficits with Europe and to accumulate capital themselves. The literature on this transatlantic trade is vast (for my own analysis, see Frank 1978a) and much more abundant than on the quantitatively much greater and more important trans-and circum-Afro-Eurasian trade. Yet far too neglected in this literature is how much the attraction of North America continued to be its own role as a waystation to the East. The continually sought-after Northwest Passage to China defined much of the history of Canada, which in turn was valued as a conduit and counterpoint to the United States and its also still intermediary position. As recently as 1873, a Canadian Tory paper welcomed a contract for a railroad to the Pacific for “bringing the trade of India, China and Japan to Montreal by the shortest route and the cheapest rate possible” (Naylor 1987: 476).

AFRICA

African population was at about 85 million in 1500 but was still only about 100 million two and a half centuries later in 1750, of which about 80 and 95 million respectively were south of the Sahara (see tables 4.1 and 4.2 in chapter 4 below). Of course, the slave wars and trade intervened to subtract population and especially men (thus changing the ratio in favor of women, but also subtracting fertile women) from the slaving areas. Moreover, slaving was not limited to the Atlantic slave trade from West and Southwest Africa, but included intra-African slaving as well as in and from East Africa to Arab lands. However, the earlier suggestions of 100 million slaves exported by the slave trade have long since been revised downward to about 10 million and then up again to about 12 million; and the direct demographic impact appears not to have been very substantial (Patrick Manning: personal communication). Whether it had a more indirect one is hard to tell, although population and socioeconomic growth seems to have slowed relative to earlier centuries. It is certainly remarkable that African population remained stable while population throughout most of Eurasia expanded rapidly. That raises the question whether Africa, far from being further incorporated, was rather relatively more isolated from the worldwide forces stimulating the growth of production and population elsewhere (which of course also decimated the population in the Americas).

In the fifteenth century, intra-African trade far outweighed the better known African-European-transadantic trade (Curtin 1983: 232). Moreover, trans-Saharan trade grew in the succeeding centuries (Austen 1990: 312). West African long-distance trade—especially of gold—had been oriented northward across the Sahara (especially but not only on the heralded Timbuktu-Fez route) to the Mediterranean (see map 2.3). This trade was supplemented, but never replaced, by maritime trade around Senegal and then also by the slave trade across the Adantic, both from northwest and southwest Africa.

That is, Africa's participation in transatiantic trade neither initiated its far-flung trade relations and division of labor, nor did it replace trans-Saharan trade. On the contrary, in Africa (and as we will note below in West, South, Southeast, and East Asia as well), the new maritime trade instead complemented and even stimulated the old and still ongoing overland trade. As Karen Moseley (1992: 536) aptly observes, “the form and content of the new trade,…at least until the eighteenth century, was very much an extension of preexisting patterns.” “When the region was integrated into both desert and oceanic commercial systems, Sudanic trade and industry reached its peak” (Moseley 1992: 538, quoting Austen 1987: 82). So trans-Saharan trade continued to thrive in general, and in particular its transport of slaves from West Africa grew from 430,000 in the fifteenth century to 550,000 in the sixteenth, and to over 700,000 in each of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Moseley 1992: 543,534, also citing Austen 1987). There always also was some west-east trade, including the legendary amounts of gold carried by “pilgrims'” via or from the Maghreb overland via Libya or through the Mediterranean to Egypt and Arabia.

In West Africa, cowrie shells became a major medium of exchange. They were produced in the Maldive Islands, were in use as money in South Asia, and Europeans brought them to Africa to buy slaves for export. The import of cowrie shells increased massively—and later again decreased—concomitantly with the slave trade. The demand for cowries was African, so that they were imported into Africa, where cowrie shell money co-existed with and even displaced gold dust and gold and silver coins and sometimes became regionally dominant. Like metal and all money elsewhere, cowries served to expand economic activity and commercialization into the interior, especially among the poorer people. However, cowries could not again be exported, since Europeans and others refused to accept them in payment. This one-way cowrie trade therefore helped to marginalize Africans from world trade as a whole (Seider 1995; for further discussion of cowries, see chapter 3 on money). However, textiles were an important, and often more important, medium of exchange within Africa; but the imported cloth of higher quality was monetized less than African cloth was (Curtin 1983: 232).

East African trade, which had been described in Roman times in the Periplus of the Erytrean Sea, was predominantly oriented northward to the Fertile Crescent and eastward across the Indian Ocean. In the period under discussion in this book, exports were primarily “natural” products, especially ivory and gold, but also slaves; and the imports were Indian textiles and grains, Arabic earthenware, Chinese porcelain, and cowrie shells from the Maldives for use as money. East African ports served as conduits for trade between southern Africa, especially Zimbabwe and Mozambique, and northern Africa and/or Indian Ocean ports. The shipping and trade was largely in Arab and also Indian hands, although even Americans from New England were active on the southeast African and Madagascar coasts, if only as privateers:

The Americans switched between looting, preying on Arab or French ships and exchanging Indian textiles, ropes, sailcloth, arms or munitions against coral, beads, or other products in use in other slave-markets. For, besides to Madagascar, the Americans traded at Mozambique, Bela Goa Bay, the Swahili coast and—if we are to believe Defoe—even at Mogadishu. The hold would contain, in addition to the inevitable arms and rum, a good array of other goods since it was unknown how much and where products had been traded by the French, Dutch and metropolitan English competitors. (Barendse 1997: chap. 1)

EUROPE

The major importers and re-exporters of both silver and gold bullion were western and southern Europe, to cover their own perpetual and massive structural balance of trade deficits with all other regions, except with the Americas and Africa. Of course, the Europeans were able to receive African and especially American bullion without giving much in return, and much of that they provided as intermediaries in their re-export of Asian goods. Western Europe had a balance of trade deficit with—and therefore re-exported much silver and some gold to—the Baltics and eastern Europe, to West Asia, to India directiy and via West Asia, to Southeast Asia directly and via India, and to China via all of the above as well as from Japan.

An indication of the European structural balance of trade deficit is that gold and silver were never less than two-thirds of total exports (Cipolla 1976: 216). For instance in 1615, only 6 percent of the value of all cargo exported by the Dutch East India Company was in goods, and 94 percent was in bullion (Das Gupta and Pearson 1987: 186). Indeed, over the sixty years from 1660 to 1720, precious metals made up on the average 87 percent of VOC imports into Asia (Prakash 1994: VI-20). For similar reasons, the British state, representing also manufacturing and others interested in “export promotion,” obliged the British East India Company by its charter to include British export products of at least one-tenth of the value of its total exports. Yet, the company had constant difficulty to find markets even for this modest export, and most of that went only as far as West Asia. Later, a small amount of broadcloth woolen textiles were placed in India for use not in clothing but as household and military goods, such as rugs and saddles. Most European exports were of metal and metal products. Unable to fill even its 10 percent export quota, the company had to resort to over-and under-invoicing to reduce “total” exports, and it was under constant pressure to find financing for its Asian imports in Asia itself. Therefore, it engaged in the intra-Asian “country trade,” which was much more developed and profitable than the Asia-Europe trade.

In summary, Europe remained a marginal player in the world economy with a perpetual deficit despite its relatively easy and cheap access to American money, without which Europe would have been almost entirely excluded from any participation in the world economy. Europe's newfound sources of income and wealth generated some increase in its own production, which also supported some growth of population. That began to recover from the disastrous fourteenth-century decline in the fifteenth century, and for the next two and a half centuries Europe's population grew at an average of about 0.3 percent a year, to double from 60 or more million in 1500 to 130 or 140 million in 1750. By Eurasian standards however, European population growth was relatively slow; for in Asia in general and in China and India in particular, population grew significantly faster and to much higher totals (see tables 4.1 and 4.2).

WEST ASIA

West Asia (or more properly, the many different regions and cities scattered throughout the Ottoman and Safavid Persian empires and contiguous regions) contained an interlocking series of productive and commercial centers of its own. Ottoman population grew in the sixteenth century but leveled off after that, and by Eurasian standards West Asian population as a whole seems to have remained rather stable at about 30 million (see table 4.1).

Since time immemorial, the location of West Asia made it into a sort of commercial and migratory turntable between the Baltics/Russia/ Central Asia to the north and Arabia/Egypt/East Africa to the south, and especially between the transatlantic/West African/ Maghreb/European/Mediterranean economic centers to the west and all of South, Southeast, and East Asia to the east. Productive centers were widely scattered, and trade among them, as well as between them and the rest of the world, was both maritime and overland. There was also a combination of overland, maritime, and riverine trade, which were transshipped at many cities in West Asia. For centuries the Persian Gulf route to and from Asia had favored Baghdad as a meeting place and transshipment center of caravan, riverine, and maritime trade from and to all directions. Alternatively and in perpetual competition with the same, the Red Sea route favored Cairo, the Suez region and of course Mocha and Aden near the Indian Ocean. Trade was in the hands mostly of Arabs and Persians and—as also elsewhere in Asia—of merchants from the Armenian diaspora, based especially in Persia.

The Ottomans. The European view that the Ottoman Empire was a world onto itself and “virtually a fortress” (Braudel 1992: 467) is more ideological than factual. Moreover, the “traditional” Eurocentric put-down of the Ottomans as stuck-in-the-mud Muslim military bureaucrats only reflects historical reality insofar as it is an expression of the very real commercial competition that the Ottomans posed for European commercial interests and ambitions. Although the same Braudel also called the Ottoman Empire “a crossroads of trade,” it had a far more important place and role in the world economy than Europeans like Braudel recognized.

The Ottomans did indeed occupy a geographical and economic crossroads between Europe and Asia, and they sought to make the most of it. The east-west spice and silk trade continued overland and by ship through Ottoman territory. Constantinople had developed as and lived off its role as a major north-south and east-west crossroads for a millennium since its Byzantine founding. That also made it attractive for conquest by the Ottomans, who renamed it Istanbul. With a population of 600,000 to 750,000, it was by far the largest city in Europe and West Asia and nearly the largest in the world. As a whole, the Ottoman Empire was more urbanized than Europe (Inalcik and Quataert 1994: 493, 646). Other major commercial centers, which vied with each other over trade routes, were Bursa, Izmir, Aleppo, and Cairo. The fortunes of Cairo had always depended on the Red Sea route as an alternative to the Persian Gulf one. In the late eighteenth century, the competition between Caribbean and Arabian coffee undermined Cairo's prosperity.

Of course, the Ottomans like everybody else had no desire to choke off the goose that laid (or at least attracted) any golden eggs through transit trade. Particularly important was the transit trade of money even though “world economic and monetary developments often had consequences for the Ottoman monetary system…[which] was often vulnerable to and adversely affected by the large movements of gold and silver” which passed through from west to east (Pamuk 1994: 4). Moreover, the Ottomans were linked not only with Europe to the west but also directly with Russia to the north and Persia to the east:

Imperative economic interdependency compelled both [Ottoman and Persian] sides to maintain close trade relations even during wartime…. The impact of the expansion in the use of silk cloth and the silk industry in Europe cannot be underestimated. It formed the structural basis for the development of the Ottoman and Iranian economies. Both empires drew an important part of their public revenues and silver stocks from the silk trade with Europe. The silk industries in the Ottoman Empire…depended on imported raw silk from Iran…. Bursa became a world market between East and West not only for raw silk but also for other Asian goods as a result of the revolutionary changes in the network of world trade routes in the fourteenth century [and remained so through at least the sixteenth century]. (Inalcik and Quataert 1994: 188, 219)

However, the Ottoman court and others also had their own resources—and transcontinental trade connections—to import large quantities of distant Chinese goods, of which over ten thousand pieces of porcelain in only one collection today is testimony.

The wealth of the Ottoman Empire also derived from substantial local and regional production and commercialization, interregional and international specialization, division of labor, and trade. The Ottoman economy involved substantial intersectoral, interregional, and indeed international labor migration among the private, public, and various semipublic enterprises, sectors, and regions. Evidence for these comes from, among others, studies by Huri Islamoglu-Inan (1987) and Suraiya Faroqhi (1984, 1986, 1987) of silk, cotton and their derived textiles, leather and its products, agriculture in general, as well as mining and metal industries. For instance, Faroqhi summarizes:

First of all, the weaving of simple cotton cloth was in many areas a rural activity. Secondly, it was carried out in close connection with the market. Raw materials in quite a few cases must have been provided commercially, and linkages to distant buyers assured. In passing, a further document…reveals that here lay an opportunity for profitable investment. (Faroqhi 1987: 270)

Furthermore, the Ottomans expanded both westward and eastward. This expansion was motivated and based not only politically and militarily but also, indeed primarily, economically. Like everybody else, be they Venetians, French, Portuguese, Persians, Arabs, or whatever, the Ottomans were always trying to divert and control the major trade routes, from which they and especially the state lived. Therein, the main Ottoman rivals were these same European powers to the west and their Persian neighbors to the east. The Ottoman Muslims fought, indeed sought to displace, the Christian Europeans in the Balkans and the Mediterranean, where economic plums were to be picked, obviously including control of the trade routes through the Mediterranean. However, the Balkans also were a major source of timber and dye wood, silver, and other metals, and the conquest of Egypt assured the Ottomans a supply of gold from Sudanese and other African sources.

A realistic approach to this problçmatique from a wider world economic perspective is offered by Palmira Brummett (1994). She studies Ottoman naval and other military policy as an adjunct to and battering ram for its primarily commercial regional interests and world economic ambitions:

The Ottomans were conscious participants in the Levantine trading networks among which their empire emerged. Their state can be compared to European states on the bases of ambitions, commercial behaviours, and claims to universal sovereignty. The Ottoman state behaved as merchant, for profit, and to create, enhance, and further its political objectives. These objectives included the acquisition and exploitation of commercial entrepôts and production sites…. Pashas and vezirs, far from disdaining trade, were attuned to commercial opportunities and to the acquisition and sheltering of wealth to which those opportunities could lead…. There is evidence of the direct participation of members of the Ottoman dynasty and of [the administrative-military class] askevi in trade…particularly of long established grain export…. Also important were the Ottoman investments in the copper, lumber, silk, and spice trades. It is clear that the Ottomans were attracted by the prospect of capturing the oriental trade, rather than simply by the possibilities of territorial conquest, and that state agents urged the sultans to conquest for commercial wealth. Ottoman naval development was directed to the acquisition and protection of that wealth. (Brummett 1994: 176,179)

Eastward, the first obstacle to Ottoman ambitions for a greater share of the South Asian trade were the Mamluk traders from Egypt and Syria. However, many Mamluks were quickly put out of business—with Portuguese help. Arab traders also continued to do Indian Ocean business under Ottoman sovereignty, and there were few Turks in the trade. The next major obstacle, especially for Turkish-manned trade to the East, was the Safavid empire in Persia. That obstacle was never overcome, despite the Ottoman-Safavid wars and notwithstanding the tactical alliance of convenience between the Ottomans and the Portuguese against the Persians. Nonetheless, the Portuguese had their own ambitions in the Indian Ocean. They competed with both the Ottomans and Persians for the same trade. The Portuguese intervention did substantially eliminate the Venetian monopoly position in the silk trade and aided the Ottomans in establishing their own substantial monopoly position, at least in the Levant trade (Attman 1981: 106–7, Brummett 1994: 25).

Incidentally, these shifting tactical diplomatic, political, and military alliances and competitive maneuvering or outright war in pursuit first and foremost of commercial advantage belie the myth of alleged common fronts and interests between the Christian West on the one hand and the Muslim East on the other. Muslims (Mamluks, Ottomans, Persians, Indians) fought with each other, and they forged shifting alliances with different European Christian states (for example, Portuguese, French, Venetian, Hapsburg), which also vied with each other all in pursuit of the same end: profit. The Muslim Persian Shah Abbas I sent repeated embassies to Christian Europe to elicit alliances against their common Ottoman Muslim enemies, and later made commercial concessions to the English in compensation for their help in throwing the Portuguese out of Hormuz. Before that, however, the Portuguese had supplied the Muslim Safavids with arms from Muslim India to use against the Muslim Ottomans.

So only when it was convenient, “the use of religious rhetoric…was a strategy employed by all the contenders for power in the Euro-Asian sphere. It served to legitimize sovereign claims, rally military and popular support, and disarticulate the competing claims of other states” (Brummett 1994: 180). A case in point was the alliance among the Muslim Ottomans, Gujaratis in India, and Sumatrans at Aceh, to which the Ottomans sent a large naval mission as part of their common commercial rivalry against the Portuguese. Also incidentally, this “business” of ever-shifting alliances and wars of all against all also has another interesting implication: there is no foundation in fact for the alleged differences between European states and those in other parts of the world in their international behavior. That demolishes still another Eurocentric fable about European “exceptionality.”

So in conclusion and contrary to the conventional wisdom, we must agree with Faroqhi when he summarizes that

Trade between the Ottoman Empire and the Indian subcontinent, as well as Ottoman-Iranian commerce and interregional trade within the Empire itself…[largely] used the Asian land routes, and their control by the Ottoman state was a factor staving off European economic penetration…. The Ottoman Empire and Moghul India have both been placed in the category of “gunpowder empires.” But they share an even more significant feature: they were both cash-taxing empires, and as such they could not exist without internal and external trade. (Faroqhi 1991: 38, 41)

Safavid Persia. Persia was less vulnerable, perhaps both because its location gave it an even stronger trading position and because it had more of its own sources of silver, which it coined—also for circulation among the Ottomans.

Routes criss-crossed the Iranian plateau linking east with west, the steppes of Central Asia and the plains of India with the ports of the Mediterranean and north and south, down the rivers of Russia to the shores of the Persian Gulf carrying trade from the East Indies, India and China to Europe. Along the roads were strung the main towns, their sites determined as much by geographical and economic factors as political. It is notable that the main trading routes, while fluctuating in importance, remained almost constantly in use throughout (Jackson and Lockhart 1986: 412).

Moreover, Persian overland and maritime trade was more complementary than competitive, as we observed also in the Sahara and will again in India. Indeed, the caravan trade between India and Persia flourished through the eighteenth century and carried as much merchandise as the sea route. Merchants also diversified risks by sending some shipments through Kandahar and other inland hubs and others via Hormuz/ Bandar Abbas (Barendse 1997,1).

At Hormuz, long before the Portuguese arrived there, a mid-fifteenth-century observer reported the arrival of “merchants from the seven climates” (Jackson and Lockhart 1986: 422). They arrived from Egypt, Syria, Anatolia, Turkestan, Russia, China, Java, Bengal, Siam, Tenasserim, Socotra, Bijapur, the Maldives, Malabar, Abyssinia, Zanzibar, Vijayanagara, Gulbarga, Gujarat, Cambay, Arabia, Aden, Jidda, Yemen, and of course from all over Persia itself. They came to exchange their wares or buy and sell them for cash and to a lesser extent on credit. Merchants were in good standing. Persian trade with India and the East was particularly high at the end of the fifteenth century. Persia became the major West Asian producer and exporter of silk, at costs that were lower even than either those of China or later of Bengal (Attman 1981: 40). Major importers were Russia, Caucasia, Armenia, Mesopotamia, the Ottomans, as well as the Europeans via the Ottomans. This trade generated important earnings of silver and other income for the Persian producers from Russia, Europe, and the Ottomans, but also made profits for the Ottoman middlemen. Shah Abbas I (1588–1629) and his successors did all they could to promote and protect trade, including battling against the Ottomans, importing and the protecting Armenian artisans and merchants from embattled Ottoman territories, and recovering Hormuz from the Portuguese. The Ottoman-Safavid war of 1615–1618 and indeed other on-and-off conflicts between Persia and the Ottomans between 1578 and 1639 were over control of the silk trade and its alternative routes. The Persians sought to bypass the Ottoman intermediaries, and the latter to cement their position. Persian trade then turned increasingly eastward across the Indian Ocean, and after the fall of the Safavid monarchy in 1723, Persian silk was largely replaced by that from Syria.

First the Portuguese and after them the Dutch traded in and around Persia. Persian silk and some wool were the main items in European demand. They were paid for with Asian spices, cotton textiles, porcelain, assorted other goods, and European metal products—and gold. Chronic and recurrent commercial conflicts between Europeans and the Shah as well as with private traders in Persia generated frequent diplomatic and occasional military conflicts. However, the Europeans mostly lacked both the commercial bargaining power and political military power to get their way.

To say, for example, that the Dutch East India Company (VOC) made Persia subservient to its worldwide trading connection is to state a belief that would not have been shared by either Dutchmen or Persians. It is therefore sometimes necessary to look at historical reality—at how things probably really were…. [This] shows that Europeans did not order Persians about, but rather the other way around…. The Europeans might take action in the face of such a situation, and in fact they did, but they were unable to create a structural improvement of their situation throughout the entire 140 years that the VOC was present in Persia. (Floor 1988:1)

To summarize the trade of West Asia as a whole, it had a balance of trade surplus with Europe, but a balance of trade deficit with South, Southeast, and East Asia (and probably with Central Asia, across which silver moved predominantly eastward, but gold westward). West Asia covered its balance of trade deficits to the East with the re-export of bullion derived from its balance of trade surplus with Europe, the Maghreb and via it with West Africa, and gold from East Africa, as well as some of its own production of both gold and silver, especially in Anatolia and Persia. An observer wrote in 1621:

The Persians, Moores, and Indians, who trade with the Turkes at Aleppo, Mocha, and Alexandria, for Raw Silkes, Drugs, Spices, Indico, and Calicoes; have alwaies made, and still doe make, their returnes in readie money; for other wares, there are but few which they desire from foreign partes…[which] they do yearly vent in all, not for above 40. or 50. thousand pounds sterling [or only 5 percent of the cost of the above mentioned imports that had to be paid for in specie], (cited in Masters 1988: 147)

Nonetheless, Chaudhuri writes that

whether or not the Islamic world [of West Asia] suffered a perpetual deficit on its balance of trade is debatable. There is little doubt that its trade to India, the Indonesian archipelago, and China was balanced by the export of precious metals, gold and silver. [However] the Middle East appears to have enjoyed a financial surplus with the Christian West, Central Asia, and the city-states of eastern Africa. The favorable balances materialised in the form of treasure, and what was not retained at home as a store of wealth flowed out again in eastward directions. (Chaudhuri 1978:184–45)

INDIA AND THE INDIAN OCEAN

We may visualize a sort of necklace of port-city emporia strung around Asia (see map 2.4):

The most important of these port-cities were, going clockwise, Aden and later Mocha, Hormuz, several in the Gulf of Cambay (at different times Diu, Cambay, and Surat), Goa, Calicut, Colombo, Madras, Masulipatam, Malacca and Aceh. All no doubt rose and fell in importance during our period, but certain common characteristics can be mentioned. In all of them the population was exceedingly diverse, including usually representatives of all the major seafaring communities of the Indian Ocean, and sometimes from outside: Chinese in Malacca, Europeans in most of them…. all of these port cities also acted as transhipment centres. Some with unproductive interiors, such as Hormuz and Malacca, had this as their almost exclusive role, but even exporting ports funnelled on goods from elsewhere. Politically all these port cities had a large, or at least a necessary, degree of autonomy. Some were completely independent. (Das Gupta and Pearson 1987: 13)

The geographical and economic center of this Indian Ocean world was the Indian subcontinent itself. Much of it was highly developed and already dominant in the world textile industry before the Mughal conquest. However, that conquest further united, urbanized, and commercialized India, notwithstanding the imperial Mughal's alleged financial dependence on agriculture and its tax yields. In fact by the seventeenth century, the principal Mughal capitals of Agra, Delhi, and Lahore each had populations of some half million and some of the commercial port cities listed above had 200,000 inhabitants each. Urbanization in cities over 5,000 reached 15 percent of the population. This was significantly higher than later Indian urbanization in the nineteenth century and dwarfs the 30,000 inhabitants of European-controlled enclave cities in Asia such as Portuguese Malacca and Dutch Batavia (Reid 1990: 82). Total population in the Indian subcontinent also expanded, more than doubling in two and a half centuries from between 54 and 79 million in 1500 to between 130 and 200 million in 1750 (see tables 4.1 and 4.2). Other estimates are some 100 million in 1500, 140 to 150 million in 1600, and 185 to 200 million in 1800 (Richards 1996).

Turning to India, Chaudhuri explains that

taken as a whole, the caravan and seaborne trade of India was oriented more toward exports than imports, and the favorable balance was settled in precious metals…. India's trade to the Middle East was dominated by the import of treasure, just as exports to South East Asia were balanced by imports of spices, aromatics, and Chinese goods…. There was even considerable re-export of silver from the subcontinent in the direction of Java, Sumatra, Malaya, and China…. Large quantities of cotton textiles were exported to Manila and were then sent to Spanish America by way of the galleon trade to Acapulco. The returns were made largely in silver. (Chaudhuri 1978: 185)

So, India had a massive balance of trade surplus with Europe and some with West Asia, based mostly on its more efficient low-cost cotton textile production and also of course on pepper for export. These went westward to Africa, West Asia, Europe, and from there on across the Atlantic to the Caribbean and the Americas. However, India also exported food staples, like rice, pulses, and vegetable oil both westward (as had been the case as early as the third millennium B.C.—see Frank 1993) to the trading ports of the Persian Gulf and Red Sea (which also depended on Egypt for grain supplies), and eastward to Malacca and elsewhere in Southeast Asia. In return, India received massive amounts of silver and some gold from the West, directly around the Cape or via West Asia, as well as from West Asia itself. Mocha (which has given its name to coffee) was called “the treasure chest of the Mughal” for the silver from there. Since India produced little silver of its own, it used the imported silver mostly for coinage or re-export, and the gold for coinage (of pagoda coins), jewelry, and hoarding.

India also exported cotton textiles to and imported spices from Southeast Asia. The same route was used to exchange cotton textiles for silk and porcelain and other ceramics with China. However, India seems to have had a balance of trade deficit with Southeast Asia, or at least India re-exported silver to there, and especially to China. However, the vast bulk of this trade was in Muslim Indian hands and on Indian-built shipping, although some was also in Arab and Southeast Asian—also Muslim—hands. A very small, albeit in the eighteenth century growing, share was in one or another European country's ships, which however employed Asian captains, crews, and merchants as well (Raychaudhuri and Habib 1982: 395–433, Chaudhuri 1978).

Inland trade moved by water and overland. Ubiquitous short-haul (or, small-boat) shipping went all along and around the coasts of India. Inland waterways were available in many parts of India, especially in the south. Even in the north, shipping was built in many provinces, including Kashmir, Thatta, Lahore, Allahabad, Bihar, Orissa, and Bengal. Caravans numbering from ten to forty thousand pack and/or draught animals at a time moved overland. Combinations of all of the above crisscrossed the subcontinent and were transshipped to and from long-distance maritime trade. “We see the relation between activities on land and sea as asymmetric. Most of the time sea activities had less influence on those on land than vice versa” (Das Gupta and Pearson 1987: 5). Almost all the port cities were in organic symbiosis with the caravan routes into and from their respective hinterland interiors and sometimes also with distant transcontinental regions, especially in Central Asia. Indeed, Chaudhuri (1990a: 140) suggests that the continental overland trade and the Indian Ocean maritime trade should be viewed as mirror images of each other.

In southern India, the inland capital of Vijayanagara was for a long time the focal point of trade to and from Goa in the west, Calicut in the south, and Masulipatam and Pulicat on the Coromandel coast to the east. These and many other port cities, and of course especially those with no or relatively unproductive hinterlands, were highly dependent on staple food imports. These came via other port cities from father up or down the coast, but often also from ports with access to rice and other grain producing areas thousands of miles distant. Moreover, the first and last named port cities and Vijayanagara also had overland connections to the north, both to inland centers such as Hyderabad and Burhanpur and to the west Indian port of Surat (or at other times Cambay), which in turn were entrepots for the Punjab and Central Asia (for more details see Subrahmanyam 1990). However,

the trade of Central Asia had no such direct connections with the sea, and yet the whole region itself exercised a vital influence on the lives of the people closer to the monsoon belts of the Indian Ocean. In terms of direct relationships, the Central Asia caravan trade was complementary to the trans-continental maritime commerce of Eurasia. (Chaudhuri 1985: 172)

Moreover, there was the India-China trade across Nepal and Tibet, which had been going on for more than a millennium. Bengal and Assam exported textiles, indigo, spices, sugar, hides, and other goods to Tibet for sale to merchants there, who took them on for sale in China. Payment was in Chinese products, tea, and often gold (Chakrabarti 1990). (I have discussed some of these Central Asian routes and their “Silk Road” history in Frank 1992; Central Asia is covered in a separate section below in this chapter.)

Different Indian regions also traded and had balance of trade surplus and deficits with each other. The major coastal regions (Gujarat, Malabar, Coromandel, and Bengal) all traded with each other—and with Ceylon—and also served each other as entrepots in transoceanic and continental caravan trade. They also competed with each other as “exporters” to the interior of India, where their market areas overlapped. However in general, the interior had an export surplus with the coastal ports and in exchange received imported goods and coin, which had been minted from imported bullion (or melted-down foreign coins) in or near the ports. Silver tended to move north into regions governed by the Mughals, and gold went south, especially to Malabar and Vijayanagara. Below we look more closely at some major Indian regions.

North India. North India was active in interregional and international” trade with Central and West Asia, as we have already noted. B. R. Grover summarizes:

Trade in the industrial products of many a region of north India was well established. Most villages…produced a variety of piece goods…. The industrial products of commercial regions in many a province of north India were exported to other places. (Grover 1994: 235)