CHAPTER 4

The Global Economy

Comparisons and Relations

Although it is difficult to “measure” the economic output of early modern Asia…every scrap of information that comes to light confirms a far greater scale of enterprise and profit in the East than in the West. Thus Japan, in the second half of the sixteenth century\ was the world's leading exporter of silver and copper, her 55,000 miners surpassing the output of Peru for the former and for Sweden of the latter. Though Western sources tend to stress the role of eight or so Dutch ships which docked in Japan each year, in fact the eighty or so junks from China were far more important. It was the same in south-east Asia: the Europeans…[and] their ships were outnumbered ten-to-one by Chinese vessels; and the Europeans' cargoes consisted in the main, not of Western wares but of Chinese porcelain and silk.

The output of both commodities was stunning. In Nanking alone, the ceramic factories produced a million pieces of fine glazed pottery every year, much of it specifically designed for export—those for Europe bore dynastic motifs, while those for Islamic countries displayed tasteful abstract patterns…. In India, the city of Kasimbazar in Bengal produced, just by itself, over 2 million pounds of raw silk annually during the 1680s, while cotton weavers of Gujarat in the west turned out almost 3 million pieces a year for export alone. By way of comparison, the annual export of silk from Messina…Europe's foremost silk producer [J was a mere 250,000 pounds…while the largest textile enterprise in Europe, the Leiden “new draper?, produced less than 100,000 pieces of cloth per year. Asia, not Europe, was the centre of world industry throughout early modern times. It was likewise the home of the greatest states. The most powerful monarchs of their day were not Louis XIV or Peter the Great, but the Manchu emperor K'ang-hsi (1662–1722) and the “Great Moghul” Aurangzeb (16S8-1707).

The Times Illustrated History of the World (1995: 206)

Quantities: Population, Production,

Productivity, Income, and Trade

The so-called European hegemony in the modern world system was very late in developing and was quite incomplete and never unipolar. In reality, during the period 1400–1800, sometimes regarded as one of “European expansion” and “primitive accumulation” leading to full capitalism, the world economy was still very predominantly under Asian influences. The Chinese Ming/Qing, Turkish Ottoman Indian Mughal, and Persian Safavid empires were economically and politically very powerful and only waned vis-à-vis the Europeans toward the end of this period and thereafter. Therefore, if anything, the modern world system was under Asian hegemony, not European. Likewise, much of the real dynamism of the world economy lay in Asia throughout this period, not in Europe. Asians were preponderant in the world economy and system not only in population and production, but also in productivity, competitiveness, trade, in a word, capital formation until 1750 or 1800. Moreover, contrary to latter-day European mythology, Asians had the technology and developed the economic and financial institutions to match. Thus, the “locus” of accumulation and power in the modern world system did not really change much during those centuries. China, Japan, and India in particular ranked first overall, with Southeast Asia and West Asia not far behind. The deficitary Europe was clearly of less significance than Asia in the world economy in all respects. Moreover, its economy was based on imports and not on exports, which were the sine qua non of industrial ascendance, then as now. It is also difficult to detect even any significant change in the relative position among the Asian powers, Europe included. Europe did not emerge as a Newly Industrializing Economy (NIE)challenging Asia until the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Only then and not before did the world economic center of gravity began to shift to Europe.

The preponderance of Asian economic agents in Asia and of Asia itself in the world economy has been masked not only by the attention devoted to “the rise of the West” in the world, but also by the undue focus on European economic and political penetration of Asia. This chapter will document and emphasize how very out of focus this perspective of European expansion is in real world terms. However, the argument is not and cannot remain confined to mere comparisons between Europe and Asia or its principal economies in China and India. The analytically necessary emphasis must be shifted to the worldwide economic relations, in productivity, technology, and their enabling and supporting economic and financial institutions, which developed on a global scale—not just on a regional, let alone European, scale. Contrary to the Eurocentric perspective, the Europeans did not in any sense “create” the world economic system itself nor develop world “capitalism.”

POPULATION, PRODUCTION, AND INCOME

Data on world and regional population growth before the nineteenth century, or even the twentieth, are admittedly speculative. Examination of a sizable variety of sources and the relatively small variations in their estimates nonetheless affords a clear and very revealing picture of world and comparative regional population growth rates. Still used are the estimates for the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries by A. M. Carr-Saunders (1936) and his revisions of Walter Willcox (1931), who in turn also revised his own earlier estimates (see Willcox 1940). Carr-Saunders's work has been slightly modified in various publications of the Population Division of the United Nations (1953, 1954, and later). Colin Clark (1977) constructs estimates using the above plus nine other sources; his tabulation is summarized below in table 4.2. M. K. Bennett (1954) relies on many of the same sources as well as others to make his own estimates. His data are the most comprehensive and detailed and are the source for table 4.1. These estimates were compared and found to be very similar to a variety of others that are not specifically used here and whose sources are not cited, if only because they group their regions differently (for instance including all of Asiatic Russia in “Europe”). However, the estimates are checked for the key year 1750 by comparing them with John Durand's (1967, 1974) evaluations of many population series, as well as against those by Wolfgang Kollman (1965) reproduced in Rainer Mackensen and Heinze Wewer (1973).

All of these world and regional population growth estimates reveal essentially the same significant story, so that we will not err much by using the figures from Bennett (1954). World (as well as European) population declined in the fourteenth century and resumed its upward growth from 1400 onward. World population grew by about 20 percent in the fifteenth century and by about 10 percent in the sixteenth century (all figures cited here are rounded percentages of the totals listed in table 4.1). However, subtracting the precipitous post-Columbian population decline in the Americas (which these tables underestimate in comparison to the more than 90 percent decline cited in chapter 2), in the rest of the world population still grew by 16 percent in the sixteenth century. Then world population growth accelerated to 27 percent in the seventeenth century, or 29 percent outside of the Americas. The mid-seventeenth century seems to have been a period of inflection and even further acceleration, so that in the century from 1650 to 1750 world population growth increased to 45 percent. These significant increases in world population growth were supported by concomitant increases in production, which were fueled by increases in the world supply and distribution of money, as argued in chapter 3.

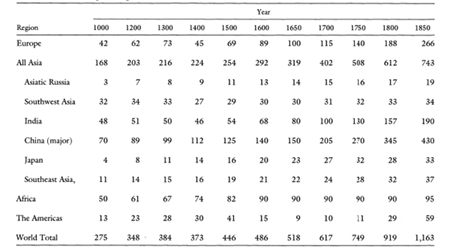

Table 4.1 World and Regional Population Growth (in millions, rounded)

SOURCE: M. K. Bennett (1954: table 1)

The regional distribution and variation in this population growth is significant as well. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, population growth was relatively fast in Europe at 53 and 28 percent respectively, so that Europe's share of world population rose from 12 percent in 1400 to 18 percent in 1600. After that however, the European share of world population remained almost stable at 19 percent until 1750, when it finally began to increase to 20 percent in 1800 and 23 percent by 1850. Yet at the same time from 1600 onward, population rose more and faster in Asia. Having been about 60 percent of world population in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Asia's share of world population rose from 60 percent in 1600 to 65 percent in 1700, 66 percent in 1750, and 67 percent in 1800, according to Bennett's estimates. That is because population grew at about 0.6 percent a year in the previously already more densely populated Asia, while in Europe it grew at only 0.4 percent per year. According to the later figure of Livi-Bacci (1992: 68), the rate of population growth in Europe was only 0.3 percent. That is, in relative terms Europe population grew at only half or two-thirds of what it did in the much larger Asia, where absolute growth was of course much greater still. This faster growth of population in Asia is also confirmed by Clark (1977), whose estimates of the Asian shares of world population are about 54 percent in 1500, 60 percent in 1600, and 1650, and 66 percent for 1700, 1750, and 1800. Mackensen and Wewer (1973) and Durand (1967,1974) also confirm the 66 percent estimate for the share of all of Asia for 1750.

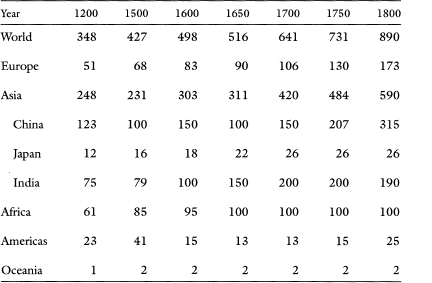

Moreover, population growth was even faster in Asia's most important regions and economies: 45 percent from 1600 to 1700 and even 90 percent over the century and a half from 1600 to 1750 in China and Japan, and 47 and 89 percent in India during the same periods—compared with 38 and 74 percent respectively in all of Asia, and only 29 and 57 percent in Europe. Clark's estimates (see table 4.2) suggest an even greater gap in population growth rates: 100 percent in India from 1600 to 1750, and after its mid-century crisis (see chapter 5), also in China from 1650 to 1750, compared with only 56 and 44 percent during the same periods in Europe. Only in the rest of Asia, that is in Central Asia (partly represented by Asiatic Russia in table 4.1), and West and Southeast Asia, was population growth slower, at 9 and 19 percent. For Southeast Asia, Bennett estimates 28 million in 1750 and 32 million in 1800, while Clark suggests 32 million and 40 million for the same dates but is apparently including Ceylon. Durand (1974) regards even this last estimate as too low. Thus for the 1600–1750 period, Southeast Asian population growth would have been 33 percent according to Bennett (table 4.1) and 100 percent according to Clark (table 4.2), that is the same as in China and India, which seems more reasonable from the evidence of their close economic relations reviewed in chapter 2. According to Durand's (1974) suggestion, population growth in Southeast Asia was higher still, and thus would also have been much higher than in Europe during this same 1600–1750/1800 period.

Table 4.2 World Population (in millions-, rounded)

SOURCE: Colin Clark (1977: table 3.1)

Clark's table 3.1 also includes estimates for A.D. 14, 350, 600, 800, 1000, and 1340 as well as additional detail since 1500.

Thus, population grew more slowly only in West and perhaps in Central Asia, and in Africa; and it was of course negative in the Americas. Total African population remained stable at 90 million (other estimates, including table 4.2, suggest stability at 100 million) over the three centuries from 1500 to 1800 and therefore was a declining share of world totals. As a result of the Columbian “encounter” and “exchange” of course, in the Americas population declined absolutely by at least 75 percent (but by 90 percent according to the more careful estimates cited in chapter 2). Therefore it declined relative to the growing world total between 1500 and 1650, and then grew only slowly till 1750.

In summary, and all variations and doubts about population estimates notwithstanding, during the period from 1400 until 1750 or even 1800 population grew much faster in Asia, and especially in China and India, than in Europe. Alas, we lack estimates of total and regional production for this same period, but it stands to reason that this much faster population growth in Asia can have been possible only if its production also grew faster to support its population growth. The theoretical possibility that production or income per capita nonetheless remained stable in Asia and/or declined relative to those in Europe seems implausible in view of our review in chapter 2, and is empirically disconfirmed by the estimates below of world total and comparative regional production in GNP terms and per capita incomes.

Hard data on global production and income are of course also hard to come by for this period, both because they are difficult to find or construct and because few people have been interested to do so. However, a number of scholars have taken the trouble to construct estimates for part of the eighteenth century because they have wanted to use them as a base line to measure more recent Western and world economic growth, in which there is more interest. So much the better for us, since these estimates also offer some indication of world and regional production and income for at least the end of our period.

Braudel (1992) cites world and regional GNP estimates by Paul Bairoch for 1750. Total world GNP was US $155 billion (measured in 1960 US dollars), of which $120 billion or 77 percent was in “Asia” and $35 billion in all the “West,” meaning Europe and the Americas, but also including Russia and Japan because of how Bairoch grouped his estimates (to highlight subsequent growth in the “West”). If we reallocate Japan and Siberian Russia to Asia, its share of world GNP was then surely over 80 percent. Out of $148 billion GNP in 1750, Bairoch himself allocates $112 billion or 76 percent to what is in the “Third” World today, including Latin America, and $35 billion or 24 percent to the countries that are today “developed,” including Japan. For 1800, after the beginning of the industrial revolution in England, Bairoch's corresponding estimates are a total of $183 billion, of which $137 billion or 75 percent were in the part of the world that is today underdeveloped. Only $47 billion, or only 33 percent of world GNP, was in what are today's industrialized countries (Bairoch and Levy-Leboyer 1981: 5). More than another half-century later in 1860, total GNP had risen to $280 billion, and the respective amounts were $165 billion or almost 60 percent for today's “Third” World and $115 billion or still only just over 40 percent for the now developed countries (recalculated from Braudel 1992: 534).

Thus, in 1750 and in 1800 Asian production was much greater, and it was more productive and competitive than anything the Europeans and the Americas were able to muster, even with the help of the gold and silver they brought from the Americas and Africa. If Asia produced some 80 percent of world output at the end of our period in the eighteenth century, we can only speculate on what the proportions may have been at the beginning or in the middle of that four-hundred-year period. Were they the same, because over four hundred years production in Afro-Asia and Europe together with the Americas grew at the same rate? Or was the Western proportion lower and the Afro-Asian one even higher, because Europe grew faster and its American colonies threw their output into the balance? The comparative population growth rates cited above must incline us against either of these hypotheses. Rather the reverse, the Asian share of the world total was lower in the fifteenth century and then grew because the Asian economies grew even faster in the following centuries than the Europeans did. The evidence on relative population growth rates above, as well as scattered evidence in chapters 2 and 3, and our argument about higher inflation in Europe than in Asia, all support this last hypothesis: production also grew faster in Asia than in Europe! Moreover, if inflation and prices were higher in Europe than in Asia, perhaps they may also have introduced an upward bias into Bairoch's calculations of GNP in the West, relative to the East. In that case, the gap in real production and consumption between Asia and Europe and America may have been greater still than the 80:20 ratio cited above.

Particularly significant is the comparison of Asia's 66 percent share of population, confirmed by all above cited estimates for 1750, with its 80 percent share of production in the world at the same time. So, two-thirds of the world's people in Asia produced four-fifths of total world output, while the one-fifth of world population in Europe produced only part of the remaining one-fifth share of world production to which Africans and Americans also contributed. Therefore on average Asians must have been significantly more productive than Europeans in 1750! A fortiori, the most productive Asians in China and India, where population had also grown much faster, must have been that much more productive than the Europeans. In Japan between 1600 and 1800, population increased by only about 45 percent, but agricultural output doubled, so productivity must have increased substantially (Jones 1988:155). By 1800, wages of cotton spinners, per capita income, life expectancy, and stature or height of people was similar in Japan and England, but by the early nineteenth century, average quality of life may have been higher in Japan than in Britain (Jones 1988: 160,158).

Indeed, Bairoch's estimate of per capita GNP for China in 1800 is (1960) US $228, which compares rather well with his estimates for various years in the eighteenth century for England and France, which range from $150 to $200. By 1850, China's GNP had declined to $170 per capita, and of course India's GNP also declined in the nineteenth century and probably had already declined in the last half of the eighteenth century (Braudel 1992: 534).

Indeed, all per capita income estimates also disconfirm the Eurocentric prejudices of those who might wish to argue that the greater production observed for Asia only reflects its higher population compared to that of little Europe. Bairoch (1993) reviews estimates of worldwide differentials in per capita income. As late as 1700 to 1750 he finds a maximum worldwide differential of 1 to 2.5. However he also cites a later estimate of 1 to 1.24 by Simon Kuznets, estimates of 1 to 2.2 and 2.6 by David Landes, and 1 to 1.6 or 1.3 or even 1.1 by Angus Maddison. Bairoch also reviews seven other estimates including contemporary eighteenth-century views, and himself arrives at an estimate of 1 to 1.1, or virtual parity of incomes or standards of living around the world.

Perhaps the most important standard of living “index”—the years of expectancy of life itself—was similar among the various regions of Eurasia (Pomeranz 1997: chap. 1, pp. 8–12). It was certainly not low in China if septuagenarians were common—and in 1726 nearly one percent of the population was over seventy years of age, including some more than one hundred years old (Ho Ping ti 1959: 214).

According to estimates by Maddison (1991: 10), in 1400 per capita production or income were almost the same in China and Western Europe. For 1750 however, Bairoch found European standards of living lower than those in the rest of the world and especially in China, as he testifies again in Bairoch 1997 (quoted in chap. 1). Indeed, for 1800 he estimates income in the “developed” world at $198 per capita, in all the “underdeveloped” world at $188, but in China at $210 (Bairoch and Levy-Leboyer 1981:14). Ho Ping-ti's (1959: 269, 213) population studies have already suggested that in the eighteenth century the standard of living in China was rising and peasant income was no lower than in France and certainly higher than in Prussia or indeed in Japan. Gilbert Rozman (1981: 139) also makes “international comparisons” and concludes that the Chinese met household needs at least as well as any other people in premodern times. Interestingly, even the per capita consumption of sugar seems to have been higher in China, which had to use its own resources to produce it, than in Europe, which was able to import it cheaply from its slave plantation colonies (Pomeranz 1997: chap. 2, pp. 11–15). For India, Immanuel Wallerstein (1989: 157–8) cites evidence from Ifran Habib, Percival Spear, and Ashok V. Desai, all to the effect that in the seventeenth century per capita agricultural output and standards of consumption were certainly not lower and probably higher than contemporary ones in Europe and certainly higher than Indian ones in the early and mid-twentieth century. Ken Pomeranz (1997) however suggests that European standards of consumption were higher than Asian ones.

That is, all available estimates of world and regional population, production, and income, as well as the discussion above on world trade, confirm that Asia and various of its regional economies were far more productive and competitive and had far and away more weight and influence in the global economy than any or all of the “West” put together until at least 1800. If this was not due only to Asia's greater population, as its ratios of population to production and its per capita income figures show indirectly and inferentially, how was this possible? Part of the answer lies in ample direct evidence on Asia's greater productivity and competitiveness in the world economy, to which we turn below. Moreover, Asia's preeminence was also rendered possible by technology and economic institutions, which we examine in the final two sections of this chapter.

PRODUCTIVITY AND COMPETITIVENESS

We have some direct evidence on Asia's absolute and relative productiveness and competitiveness, especially in industrial production and world trade. K. N. Chaudhuri (1978) rightly observes that the demand for industrial products, even in a pre-machine age, measures the extent of specialisation and the division of labour reached by a society. There is no question that from this point of view the Indian subcontinent and China possessed the most advanced and varied economies in Asia in the period from 1500 to 1750. (Chaudhuri 1978: 204–5)

Not only in Asia, however, but in the world!

It is clear that Asia's absorption of silver, and to a lesser extent gold for a limited period in the seventeenth century, was primarily the result of a relative difference in international production cost and prices. It was not until the large-scale application of machinery in the nineteenth century radically altered the structure of production costs that Europe was able to bridge the effect of the price differentials. (Chaudhuri 1978: 456)

Yet it has also been argued that Indian competitiveness in textiles was not so much due to more advanced or sophisticated mechanical productive equipment. Kanakalatha Mukund (1992) agues that the Indians' advantage lay in the highly developed skills of their (handicrafts) workers. That in turn was due in part to the also high degree of specialization in and subdivision among the various productive processes. Moreover, Indian competitiveness was also based on an organizational structure that permitted rapid flexible adaptation to shifting market demands for types and styles of textiles that were produced and exported. Additionally, India was preeminent in the growth and quality of its long-staple cotton and in the chemical technology and industry to dye it. Finally, costs of production were low because wages were low, because wage-good foodstuffs for the producers were cheap; and in turn that is because Indian agriculture produced them efficiently at low cost.

Chaudhuri summarizes some of the industrial production in Asia:

The three great crafts of Asian civilisations were of course textiles, cotton and silk, metal goods including jewellery, [and] ceramics and glassware. There were in addition a whole range of subsidiary craft manufactures which shared all the attributes of industrial technology and organization: paper, gunpowder, fireworks, bricks, musical instruments, furniture, cosmetics, perfumery; all these items were indispensable parts of daily life in most parts of Asia…. The surviving historical material, whether relating to the process of manufacturing or the system of distribution, shows quite clearly that most Asian craft industries involved intermediate stages, and the separation of functions was social as well as technical. In the textile industry before a single peace of chinz or muslim reached the hands of the public, it needed the services of farmers growing raw cotton, harvesters, those who ginned the cotton fibre, carders, spinners, weavers, bleachers, printers, painters, glazers, and repairers…. A list of historical objects fashioned from metal itself would be a long one. Agricultural tools and implements, metal fastenings, doors and locks in buildings, cooking utensils, heavy and fine armaments, religious artifacts, coins, and jewellery…. An active and varied trade developed in all parts of Asia in coarse cloth, earthenware pottery, iron implements, and brass utensils. Ordinary people as well as the well-off bought these simple goods of everyday use…. (Chaudhuri 1990a: 302,319,323, 305)

As a joke has it, a puzzled customs officer wondered about the guy who kept crossing the border with wheelbarrows that appeared empty. It took quite a while until the customs officer got wise to what the guy was doing: he was smuggling wheelbarrows! Well, it was no joke but serious business that the preponderant majority of shipping, albeit with goods of whatever origin and engaged in legal as well as contraband trade among Asian ports, was on Asian ships built with Asian materials and labor of West, South, East, and Southeast Asian origin and financed by Asian capital. Thus, shipping, naval and port construction, and their maintenance and finance were in and of themselves already a major, continuing, and growing “invisible” industry all around Asia, which dwarfed all European interlopers probably until the nineteenth-century advent of the steamship.

An analogous “invisible industry” was coinage—minting and reminting—for local, regional, and national use, and also very much so for export. The production, assaying, and exchange of gold, silver, copper, tin, iron, and other metal coins, specie in bar and other bullion form, and of cowrie shell, badam, and other currencies (including textiles) was big business for state and private interests, to which Frank Perlin (1993) and others have devoted extensive studies. In principle, coins could be accepted at face or weight value, although not entirely so in case they may have been debased; bullion had to be assayed for weight and purity, which implied a business cost but also provided still another state or private business opportunity.

In world economic terms China, not India, was the front-runner, exporting huge quantities of valuable commodities and importing vast quantities of silver. India, however, does not seem to have been far behind China in this regard, being the seat of very significant industrial centers, particularly in cotton textiles, and importing huge quantities of bullion, particularly gold (for which India was a “sink”). We have already countered in chapter 3 the Eurocentric myth that the Asians just hoarded the money they received. On the contrary, Asians earned this money first because they were more industrious and more productive to begin with; the additional money then generated still more Asian demand and production.

West Asia too seems to have continued to prosper both from its own industrial base, in cotton and silk textiles for instance, and from transshipments of commodities between Europe and the rest of Asia. Both Southeast Asia and Central Asia appear to have prospered, largely on the transshipments of bullion and goods between regions, but in the case of Southeast Asia, also in terms of its locally produced silk, exported especially to Japan.

Europeans were able to sell very few manufactures to the East, and instead profited primarily from inserting themselves into the “country trade” within the Asian economy itself. Europe's source of profits was overwhelmingly derived from the carrying trade and from parleying multiple transactions in bullion, money, and commodities in multiple markets, and most importantly, across the entire world economy. Previously, no one power or its merchants had been able to operate in all markets simultaneously or systematically to integrate its activities between all of them in such a coherent logic of profit maximization. The main key for the European ability to do so was their control over huge supplies of bullion. Their naval capabilities were a much smaller and long indecisive factor; and their imperial or private company forms of commercial organization were not so different from those of their competitors, as we will note below. Europeans did arbitrage the differentials in exchange rates between gold and silver across all the countries of Asia, and placed themselves in a middleman role in some trade circuits, particularly between China and Japan in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Nonetheless in world economic terms, for at least three centuries from 1500 to 1800 the most important, and indeed almost only, commodity that Europe was able to produce and export was money—and for that it relied on its colonies in the Americas.

One thing is very clear: Europe was not a major industrial center in terms of exports to the rest of the world economy. Chapters 2 and 3 demonstrate that in fact Europe's inability to export commodities other than money generated a chronic balance of payments deficit and a constant drain of bullion from Europe to Asia. Only Europe's colonial sphere in the Americas explains its viability in the world economy, without which it could not have made good its huge deficits in the commodities trade with Asia. Even so it never had enough money to do so as the poor Europeans wished, for as a Dutch trader reported home in 1632, “we have not failed to find goods…but we have failed to produce the money to pay for them” (Braudel 1979: 221). This problem was not overcome until the end of the eighteenth century and especially the nineteenth century, when the flow of money was finally reversed, go to from East to West.

WORLD TRADE 1400–1800

In view of the above documentation about Asian population, production, productivity, competitiveness, domestic and regional trade, and their continued growth, it should come as no surprise that international trade was also predominantly Asian. Yet the mythology has grown up that world trade was created by and dominated by Europeans, even in Asia. We confront below the several reasons for this myth.

The Portuguese, and after them Europeans generally, have “bewitched” historians into devoting attention to themselves all out of proportion to their importance in Asian trade. Giving credit where credit is due, this enthrallment with the Portuguese, the Dutch, and the British is due in part to the fact that it is they who left the most records of Asian trade. Of course, these records also reflect their own participation and interests, more than those of their Asian partners and competitors.

The Eurocentric position about European participation in Asian trade has however become subject to increasing revision. W. H. Moreland's (1936: 201) now classical Short History of India argued that “the immediate effects produced by the Portuguese in India were not great.” The next major salvo came from a former Dutch official in Indonesia, J. C. van Leur (1955), who challenged the then still dominant Eurocentric view in a series of comments:

the general course of Asian international trade remained essentially unchanged…. The Portuguese colonial regime, then, did not introduce a single new economic element into the commerce of southern Asia…. In quantity Portuguese trade was exceeded many times by the trade carried on by Chinese, Japanese, Siamese, Javanese, Indians…and Arabs…. Trade continued inviolate everywhere…. The great intra-Asian trade route retained its full significance…. Any talk of a European Asia in the eighteenth century [a fortiori earlier!] is out of the question. (Van Leur 1955: 193,118,165,164,165, 274)

Indeed, asserts van Leur (1955: 75),”the Portuguese Empire in the Far East was actually more idea than fact,” and even that had to give way to reality, as M. A. P. Meilink-Roelofsz (1962) repeatedly observes, despite her defense of the Europeanist position. She in turn challenges the van Leur thesis in her carefully researched text on the European influence on Asian trade, which she explicitly claims was greater and earlier than van Leur allows. Yet her own evidence, and her repeated disallowance of the real impact of the Portuguese, seem to lend even more support to “van Leur's thesis that it was only about 1800 that Europe began to outstrip the East” (Meilink-Roelofsz 1962:10). Her own research concentrates especially on insular Southeast Asia, which experienced the greatest European impact in Asia; and yet even there she shows that indigenous and Chinese trade successfully resisted the Dutch.

Now, more and more scholarship—for example, Chaudhuri (1978), Ashin Das Gupta and M. N. Pearson (1987), Sinnappah Arasaratnam (1986), and Tapan Raychaudhuri and Irfan Habib (1982)—has confirmed van Leur's message that Asian trade was a flourishing and ongoing enterprise into which the Europeans only entered as an added and relatively minor player.

Asian pepper production more than doubled in the sixteenth century alone, and much of that was consumed in China (Pearson 1989: 40). Of the relatively small share, certainly less than a third, that was exported to Europe, sixteen times more spices were transported overland by Asians through West Asia than went around the Cape on Portuguese ships in 1503, and even by 1585 almost four times as much went by the Red Sea route as the Cape route (Das Gupta 1979: 257). Even though shipping was their forte, the Portuguese never carried more than 15 percent of the Moluccan cloves to Europe, and the vast bulk of Southeast Asian pepper and other spices was exported to China. Moreover, some ships flying Portuguese flags were really owned and run by Asians, who used that “flag of convenience” to benefit from the lower customs duties accorded Portugal in some ports (Barendse 1997: chap. 1). Yet with all their military and political strong-arm attempts to “monopolize” trade and to charge tribute tolls to others, Portugal's nonetheless very small share of inter-Asian trade provided 80 percent of their profits, and only 20 percent came from their trade around the Cape of Good Hope, which they had pioneered (Das Gupta and Pearson 1987: 71, 78, 84, 90; Subrahmanyam 1990a: 361). This is illustrated by the itemized documentation in a Portuguese book published in 1580, which records in Portuguese cruzados just how profitable particular routes and voyages were. For the relatively short Macao-Siam, Macao-Patane, and Macao-Timor trips, the profits were 1,000 cruzados each; for Macao-Sunda, 6,000 to 7,000 cruzados; and for Goa-Malacca-Macao-Japan, 35,000 cruzados. By comparison, for the entire Lisbon-Goa voyage via the Cape of Good Hope the owner received 10,000 to 12,000 cruzados and the ship's captain 4,000 cruzados (cited in Lourido 1996a: 18–19).

Though so important for the Portuguese, their share of the exports of silver from Japan was never more than 10 percent of the Japanese total between 1600 and 1620 and only briefly rose to a maximum of 37 percent in the 1630s (Das Gupta and Pearson 1987: 76). In India also, even at the height of their sixteenth-century “penetration” of Asia, the Portuguese handled only some 5 percent of Gujarati trade. Despite their base at Goa, Portuguese procurement was less than 10 percent of southwestern Indian pepper production. The maintenance of Portugal's “Estado da India” cost its taxpayers and the state more than its direct earnings from India, although its private merchants did benefit from it, as other European “servants” did from their companies (Barendse 1997: chap. 1).

The small Portuguese trade in East and Southeast Asia was replaced by the Dutch. Yet despite all their efforts to monopolize trade at least in parts of Southeast Asia, the Dutch never succeeded in doing so, as we observe in chapter 2. Indeed, even the inroads that the Dutch made primarily at the expense of the Portuguese were again replaced by the Chinese and other East Asians, whose domination of their seas—not to mention their lands—was never seriously challenged. From the late seventeenth century onward, “European penetration was actually reversed” (Das Gupta and Pearson 1987: 67). Europeans were outcompeted by the Chinese, whose shipping between 1680 and 1720 increased threefold to Nagasaki and reached its maximum at Batavia, when the 1740 massacre of Chinese took place (Das Gupta and Pearson 1987: 87). For instance, in the four years after shipping was legally reopened again in 1684, Nagasaki received an average of nearly 100 Chinese ships a year, or two a week; over the longer period to 1757, the average was still over 40 a year. In 1700, Chinese ships brought over 20 thousand tons of goods to South China, while European ones carried away 500 tons in the same year. In 1737 it was 6 thousand tons, and not until the 1770s did Europeans transport 20 thousand tons (Marks 1997a).

Trade from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries in the East China Sea, bordering Korea, Japan,. and the Ryukyus, and the South China Sea around Southeast Asia is illuminated in an essay by Klein (1989). He finds that Europeans never achieved any control, much less domination, or even a partial monopoly. In the East China Sea, trade was exclusively in Asian hands; Europeans hardly entered at all. In the South China Sea, first the Portuguese and then the Dutch Europeans achieved at best a foothold by taking advantage of regional disturbances until the mid-seventeenth century. However, even that was reduced to no more than a toehold (later including the British), with the economic and political recovery of East Asia in the second half of the seventeenth and through the eighteenth centuries. Klein concludes that

The European penetration into the maritime space of the China seas during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries had only been possible due to the peculiar development of the domestic and regional power relations in the area itself. Its influence on the region's economy had been marginal. Its commercial effects on the world economy had been only temporary, restricting themselves to the rather weak and limited European trading network in Asia. After the region regained a new balance of power in about 1680, its internal maritime trade experienced a new era of growth within a well established framework of traditional institutions. This trade and its institutions were gradually eroded during the later part of the eighteenth century…[but included] European commerce…[that] also fell prey to disintegration. The establishment of European hegemony in the nineteenth century found no base in what had happened in pre-industrial times…[but was based on] entirely new conditions and circumstances. (Klein 1989: 86–87)

Even at the other, western end of Asia, where commercial access was easier for the Europeans,

the Arabian seas were part of an ancient, larger network of exchange between China, South-East Asia, India, the Middle East,…[where] Europeans were tied to pre-existing arrangements, relating to foreign traders…[who] were collaborating with Asians reluctantly, for the degree of mutual trust should not be exaggerated. (Barendse 1997: chap. 1)

Turning to the significance of Asian trade in world trade as a whole, one of the European historians after van Leur most sympathetic to Asia is Niels Steensgaard (1972). He also agrees that Portugal changed little in the Indian Ocean and that much more important—indeed the event of the sixteenth century—was the conquest of Bengal by Akbar in 1576. (Steensgaard 1987: 137).

So it is surprising to read that Steensgaard (i99od) regards Asian trade through the Indian Ocean to have been “marginal” and of little importance. “The point may seem like restating the obvious,” he adds, dismissing Asian trade by noting Moreland's (1936) and Bal Krishna's estimates of 52,000 to 57,000 tons and 74,500 tons, respectively, of long-distance trade annually at the opening of the seventeenth century. He compares that with half a million or closer to a million tons of shipping capacity in Europe. However, the weight of traded cargoes versus shipping capacity are hardly commensurate measures. Steensgaard himself notes that these Indian Ocean trade figures exclude coastal shipping, which was both greater per se and an integral part of long-distance trade that also relied on relay trade. Yet European ships primarily plied the Baltic and Mediterranean coasts for distances no longer, and mostly less so, than those along the Indian Ocean or the Southeast Asian seas for that matter. So this comparison hardly seems adequate to evaluate the relative weights of India (let alone Asia) and Europe in world trade.

Moreover, as noted in chapter 2, Asian overland and maritime trade were more complementary than competitive, as Barendse also observes:

The relation between land and seaborne trade is a complex one: the choice between them partly depended upon the circuits covered, partly on “protection rent.” Trade along the caravan roads was not substituted by trade overseas. In some cases seaborne trade might even stimulate caravan trade. In others, commerce partly shifted to the sea routes, particularly where overland trade became dangerous, like in India in the late seventeenth century…. Trade on the coast depended on that of the hinterland. Many fairs were mere satellites on the coast of metropolises in the interior: thus Barcelore of Vijayanagara, Dabhul of Bijapur and—as its name indicates—Lahawribandar of Lahore. The centres of both manufacture and government were located in the hinterland; the bulk of the agricultural production was redistributed there. (Barendse 1997: chap. 1)

We observed in chapter 2 that overland trade also flourished and grew. In India and to and from Central Asia, caravans of oxen, each carrying from 100 and 150 kilograms and numbering 10 to 20 thousand animals, were not uncommon and caravans as large as 40 thousand animals were not unknown (Brenning 1990: 69, Burton 1993: 26). Caravans could also include a thousand or more carts, each drawn by ten to twelve oxen. Caravanserai, rest stops located at a day's distance from each other, accommodated up to 10 thousand travelers and their animals (Burton 1993: 25). In the seventeenth century, just one of the merchant communities, the Banjaras, transported an average of 821 million ton miles over an average of 720 miles a year. By comparison, two centuries later in 1882, all Indian railways carried 2,500 ton miles (Habib 1990: 377).

By all indications, Asia's trade with Europe, though growing over these centuries, still remained a very small share of Asians' trade with each other (even including their long-distance trade). Sir Joshua Childe, the director of the British East India Company, observed in 1688 that from some Indian ports alone Asian trade was ten times greater than that of all Europeans put together (cited in Palat and Wallerstein 1990: 26).

In view of this review of trade in Asia and especially the analysis of trade in the China seas by Klein (1989), it is noteworthy that Carl-Ludwig Holtfrerich (1989: 4) claims, in his introduction to his edited volume of papers in which Klein's work appears, that “Europe dominated throughout the whole period.” Holtfrerich goes on to claim (1989: 5, table 1.2) a European share of all world tradé at 69 and 72 percent in 1720 and 1750 respectively, leaving only 11 and 7 percent for India in those two years (an additional 12 percent is claimed for Latin America and 8 percent for “Other” during each of the tabulated time periods).

This unabashedly Eurocentric claim is disconfirmed by the evidence discussed in the present book, as well as by Klein's (1989) analysis on Chinese and not European trade in the China seas. Moreover, in the period 1752–1754 according to figures from Steensgaard (1990dl 150), the relatively small exports to Europe from Asia (which were a very small share of Asia's trade) remained higher than Europe's imports from the Americas. (European exports to the Americas were higher, but of course the Europeans were still unable to compete successfully with their exports elsewhere, that is in Asia). Indeed, even in 1626 an anonymous Iberian observer wrote a “Dissertation” whose title claims to “Demonstrate…the Greater Importance of the East Indies than the West Indies by Virtue of Trade, and therefore we Find the Causes of Why the Oriental Trade is lost and Spain is Reduced to the Abject Poverty that we [now] Witness” (translated from Lourido 1996b: 19).

Terry Boswell and Joya Misra (1995) offer another graphic illustration of how these Eurocentric blinkers not only hide most of the world economy and trade from (Western) view but also distort the perception even of the European “world-economy.” First they write that, in Wallerstein's and their view “despite trade connections, Africa and Asia remained external [to the world-system]. Neither logistics not long waves should apply to them.” Then they disagree with Wallerstein: “We think it reasonable to consider East Asian trade a leading sector in the world-system, even if Asia itself is external” (Boswell and Misra 1995: 466, 471). So they include “East Asian trade” in their calculations of “global” trade, only to find that “thousands of ships were engaged in the Baltic trade, compared to only hundreds in the Atlantic and Asian.” Since the latter journeys were longer, they allot each of them greater weight in their estimations of total “global trade”(Boswell and Misra 1995: 471–2). Alas, their myopia allows them to see and include in their “global” trade only the hundreds of ships in the East-West trade, and not to see nor count any of the thousands in the intra-Asian trade, which Holtfrerich (1989) at least included even if he vastly underestimated them. However, Boswell and Misra also fall into another trap of their own making. First they argue that the observation that “East Asian trade showed a different [cyclical] pattern from the Atlantic and global trades supports considering the latter external” (Boswell and Misra 1995: 472). They do not even consider the possibility that the divergence of “East Asian trade” from East-West trade may be compensatory, as in a see-saw. That would make their observation evidence of the opposite: Asia and its trade would be not “external” but rather internal to the system! Then they argue that their own further investigation of cyclical ups and downs accidentally shows exactly that: “This finding suggests the Asian trade is more central to the capitalist world economy than expected” (Boswell and Misra 1995: 478)! Of course, what they “expected” is a function of their own Eurocentric blinkers, but it turns out that these distort even their own analysis of the “European world-system,” as well as of course blinding them to the existence of a much larger world economy and trade in Asia.

In conclusion, the Asian economy and intra-Asian trade continued on vastly greater scales than European trade and its incursions in Asia until the nineteenth century. Or in the words of Das Gupta and Pearson in their India and the Indian Ocean isoo-1800,

a crucial theme is that while the Europeans obviously were present in the ocean area, their role was not central. Rather they participated, with varying success, in an on-going structure…. [In] the sixteenth century, the continuity is more important in the history of the Indian Ocean than the discontinuities which resulted from the Portuguese impact. (Pearson and Das Gupta and Pearson 1987: 1, 31)

Even the European (ist) Braudel had long insisted that the world economic center of gravity did not even begin to shift westward until after the end of the sixteenth century, and it did not arrive there until the end of the eighteenth century and during the nineteenth. Indeed, “the change comes only late in the eighteenth century, and in a way it is an endogamous game. Europeans finally burst out, and changed this structure, but they exploded from within an Asian context” (Das Gupta and Pearson 1987: 20).

Thus, despite their access to American money to buy themselves into the world economy in Asia, for the three centuries after 1500 the Europeans still remained a small player who had to adapt to—and not make!—the world economic rules of the game in Asia. Moreover, Asians continued to compete successfully in the world economy. How could they do so if, as the received Eurocentric “wisdom” has it, Asians lacked science, technology, and the institutional base to do so? The answer is that Asians did not “lack” any of these and instead often excelled in these areas. So let us turn now to examine the development of science, technology, and institutions in the real world and how they too differ from what Eurocentric mythology alleges.

Qualities: Science and Technology

EUROCENTRISM REGARDING SCIENCE AND

TECHNOLOGY IN ASIA

The received Eurocentric mythology is that European technology was superior to that of Asia throughout our period from 1400 to 1800, or at least since 1500. Moreover, the conventional Eurocentric bias regarding science and technology extends to institutional forms, which are examined in the following section. Here I focus on the following questions: (1) Were science and technology on balance more advanced in Europe or in Asia, and until when? (2) After importing the compass, gunpowder, printing, and so on from China, was technology then developed indigenously in Europe but no longer in China and elsewhere in Asia? (3) Was the direction of technological diffusion after 1500 from Europe to Asia? (4) Was technological development only a local and regional process in Europe or China or wherever, or was it really a global process driven by world economic forces as they impacted locally? To preview the answers that will emerge below, all of them contradict or at least cast serious doubt on the received Eurocentric “wisdom” about science and technology.

Technology turns out not to be independently parallel. Instead, technology is rapidly diffused or adapted to common and/or different circumstances. In particular, the choice, application, and “progress” of technology turns out be the result of rational response to opportunity costs that are themselves determined by world economic and local demand and supply conditions. That is, technological progress here and there, even more than institutional forms, is a function of world economic “development” much more than it is of regional, national, local, let alone cultural specificities.

Nonetheless an oft-cited student of the subject, J. D. Bernal (1969) attributes the rise of Western science and technology to the indigenous rise of capitalism in the West (which he accounts for in the same terms as Marx and Weber). Robert Merton's now classic 1938 discourse on “Science, Technology, and Society” is entirely Weberian and even linked to the latter's thesis about the Protestant ethic and the “Spirit of Capitalism.” That in itself should make his derivative thesis on science and technology suspect, as already argued in chapter 1; for another critical discussion, see Stephen Sanderson (1995: 324 ff.). Coming full circle, Rostow's (1975) “central thesis” on the origins of modern economy is quite explicit: it all began in modern Europe—with the scientific revolution.

The study of the history and role of this scientific and technological revolution seems to be much more ideologically driven than the technology and science that allegedly support it. For instance, Carlo Cipolla (1976: 207) favorably cites one of the Western “experts” on the history of technology, Lynn White, Jr., who asserts that “die Europe which rose to global dominance about 1500 had an industrial capacity and skill vastly greater than that of any of the cultures of Asia…which it challenged.” We have already seen above that Europe did not rise to “dominance” at all in 1500 if only because exactly the opposite of White's Eurocentric claim was true.

The second volume of the History of Technology edited by Charles Singer et al. (1957: vol. 2, 756) recognizes and even stresses that from A.D. 500 to 1500 “technologically, the west had little to bring to the east. The technological movement was in the other direction.” Reproduced there is a table from Joseph Needham (1954) that traces the time lags between several dozen inventions and discoveries in China and their first adoption in Europe. In most cases, the lag was ten to fifteen centuries (and twenty-five centuries for the iron plow moldboard); in other cases the lag was three to six centuries; and the shortest time lag was one century, for both projectile artillery and movable metal type. “It was largely by imitation and, in the end, sometimes by improvement of [these] techniques and models…that the products of the west ultimately rose to excellence” (Singer et al. 1957: vol. 2, 756).

However, these accounts are themselves also excessively European-focused. There was indeed much technological diffusion; but during the millennium up to 1500 it was primarily back and forth among East, Southeast, South, and West Asia, and especially between China and Persia. Before any of this technology reached Europe at all, most of it had to pass via the Muslim lands, including especially Muslim Spain. The Christian capture of Toledo and its Islamic scholars and important library in 1085 and later of Cordoba significantly advanced technological learning farther “westward” in Europe. The Byzantines and later the Mongols also transmitted knowledge from east to west.

Singer's third volume, covering the period 1500–1750, is explicitly devoted to the West. Without any further comparisons, the assertion is made that “it is certain, however” that the balance had already shifted by 1500, so that “granted the immense European naval and military superiority, European control of the Far East was an almost inevitable consequence.” Moreover, it is claimed that there was a “generally higher level of technical proficiency in Europe in the seventeenth century compared with the rest of the globe”; this is attributed to a European and especially British more “liberal social system,” being “united in religion” and other such differences in “civilization.” Also mentioned is that all this is “in no way inconsistent with an inferiority” in silks and ceramics, but cotton textiles and other industries are not mentioned (Singer et al. 1957: vol. 3, 709–710, 711, 716, 711).

However, this reference to alleged sociocultural superiority is no more than the same Eurocentric prejudice that we already challenged in chapter 1 and will have to reject after the examination below of institutions also. In principle, it could indeed have been the case that Europe lagged behind in the important ceramics, silk, and cotton industries and yet had advanced more in other technologies. However, the History of Technology does not offer the slightest comparative evidence for what is taken for “granted,” and we will observe below that the evidence from elsewhere does not support the suppositions in this multivolume history. Indeed only a quarter of a century later, David Arnold (1983: 40) was already able to observe that “there is now much greater awareness than formerly of the relative narrowness of the technological gap between Europe and China, India and the Muslim world in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.”

The Eurocentric treatment of the history of science is similar, although there is serious doubt that science, as distinct from inventors working on their own, had any significant impact on technology in the West before the middle of the nineteenth century. The received and excessively Eurocentric treatment of science is illustrated by several well known multivolume histories. A. C. Crombie's (1959) review of medieval and early modern science from the thirteenth to seventeenth centuries does not even mention any science outside of Western Europe. The first volume of Bernal's (1969) Science in History, devoted to its emergence up through the Middle Ages, gives some credit to China and less to West Asia. However, Bernal's second volume, which begins with 1440, makes no further reference to science outside Europe. Only in volume 1 does he mention that, thanks to Needham (1954-), “we are beginning to see the enormous importance for the whole world of Chinese technical developments” (Bernal 1969: vol. 1, 311). Alas, when Bernal was writing Needham had only just begun his major work. So in the very next paragraph, Bernal repeats the same old litany, and even cites Needham in support, that “this early technical advance in China, and to a lesser extent in India and the Islamic countries, after a promising start came to a dead stop before the fifteenth century, and…resulted in…a high but static technical level” (Bernal 1969: vol. 1, 312). Accordingly, Asia disappears from Bernal's second volume. We observe below that the real world evidence is otherwise.

The more recent comprehensive review by H. Floris Cohen, The Scientific Revolution. A Historical Inquiry (1994), seems more promising at first sight; but on closer inspection it too is ultimately almost equally disappointing. Cohen does importantly distinguish between science and its use in technology, and he reviews the large body of literature on “the Great Question” of why “The Scientific Revolution” took place in Europe and not elsewhere. Much of his review, of course, reflects the same inquiries cited above as well as others, from Weber and Merton to Bernal and Needham. However, Cohen takes Needham seriously enough to devote sixty-four pages to the discussion of his work and another thirty-nine pages to Islamic and other “nonemergences” of early modern science “outside Western Europe,” in a section that takes up one-fifth of his text.

Yet the thread that runs through Cohen's entire review of “the Great Question” is that something about the embedment of science in society was unique in and to Europe. That is, of course, the Weberian thesis and its resurrection by Merton as applied to science. Alas, it was also originally Needham's Marxist and Weberian point of departure. As Needham found more and more evidence about science and technology in China, he struggled to liberate himself from his Eurocentric original sin, which he had inherited directly from Marx, as Cohen also observes. But Needham never quite succeeded, perhaps because his concentration on China prevented him from sufficiently revising his still ethnocentric view of Europe itself. Nor does Cohen succeed.

For, the more we look at science and technology as economic and social activities not only in Europe but worldwide, as Cohen rightly does, the less historical support is there for the Eurocentric argument about the alleged role of the (European!) scientific revolution in the seventeenth or any other century before very modern times. Another interesting and useful example is “Why the Scientific Revolution Did Not Take Place in China-Or Didn't It?” by Nathan Sivin (1982). Sivin examines and effectively rebuts several of the same Eurocentric assumptions about this issue, but he neglects to raise the also crucial question of what impact the scientific revolution had on the development of technology, if any.

Neither does Cohen, whose review of this “revolution” and its role is even more marred by both his point of departure and his final conclusion. To begin with, Cohen seems to accept the proposition that science emerged only in Western Europe and not elsewhere. Therefore, he as much as dismisses Needham's claim that by the end of the Ming dynasty in 1644 there was no perceptible difference between science in China and in Europe. Yet Cohen's own discussion of works by Needham and others about areas outside Europe shows that science existed and continued to develop elsewhere as well. That of course stands to reason if the alleged “East-West” social and institutional differences were far more mythical than real, and it is also confirmed by other evidence cited below. But if there still was science elsewhere as well, then what is the purpose of Cohen's focus on it primarily in Europe?

Maybe even more significant, however, is that Cohen never troubles to inquire if and how science impacted on technology, even though he insists on the distinction between the two. Yet the evidence is that in Europe itself science did not really contribute to the development of technology and industry at all until two centuries after the famed scientific revolution of the seventeenth century.

To inquire into the alleged contribution of Western science to technology in general and to its industrial “revolution” in particular, it is apt to paraphrase the opening sentence of Steven Shapin's (1996) recent study of the subject: “There was no seventeenth century scientific revolution, and [this section of] this book is about it.” Authoritative observers from Francis Bacon to Thomas Kuhn conclude that, whether “revolutionary” or not, these scientific advances appear to have had no immediate impact on technology whatsoever and certainly none on the industrial “revolution,” which did not even begin until a century later.

Bacon had observed “the overmuch credit that hath been given unto authors in sciences [for alleged contributions to] arts mechanical [and their] first deviser” (cited in Adams 1996: 56). Three centuries later the author of The Structure of Scientific Revolution (1970) commented that “I think nothing but mythology prevents our realizing quite how little the development of the intellect need have had to do with that of technology during all but the most recent stage of human history” (Kuhn 1969; cited in Adams 1996: 56–57). All serious inquiries into the matter show that this “stage” did not begin until the second half of the nineteenth century and really not until after 1870, that is two centuries after the scientific “revolution” and one after the industrial “revolution.” Shapin himself devotes a chapter to the question of “What was the [scientific] knowledge for?” His subtitles refer to natural philosophy, state power, religion's handmaid, nature and God, wisdom and will, but not to technology other than also to conclude that “It now appears unlikely that the ‘high theory’ of the Scientific Revolution had any substantial direct effect on economically useful technology in either the seventeenth century or the eighteenth” (Shapin 1996: 140).

Also, Robert Adams's (1996) Paths of Fire: An…Inquiry into Western Technology reviews any and all relations between technology and science, including the “seventeenth century scientific revolution.” He cites numerous observers regarding particular technologies as well as technology and the industrial revolution in general. On the basis of these observers and his own work, Adams concludes on at least a dozen occasions (1996: 56, 60, 62, 65, 67, 72, 98, 101, 103, 131, 137, 256) that scientists and their science made no significant visible contribution to new technology before the late nineteenth century. Adams writes that “few if any salient technologies of the Industrial Revolution can be thought of as science based in any direct sense. They can better be described as craft based in important ways”; and he concludes that “scientific theories were relatively unimportant in connection with technological innovation until well into the nineteenth century” (Adams 1996: 131, 101). Adams's most generous conclusion is that “it must be emphasized that scientific discovery was not the only initiating or enabling agency behind waves of technological innovation, nor was it apparently a necessary one” (Adams 1996: 256). Through the eighteenth century in Britain only 36 percent of 680 scientists, 18 percent of 240 engineers, and only 8 percent of “notable applied scientists and engineers” were at any time connected with Oxford or Cambridge; moreover, over 70 percent of the latter had no university education at all (Adams 1996: 72). Instead, Adams and others trace technological advances primarily to craftsmanship, entrepreneurship, and even to religion. Indeed, Adams credits technology with far more contribution to the advancement of science than the reverse.

Finally, even Nathan Rosenberg and L. E. Birdzell, who attribute the West's growing “rich” only to European developments, recognize that

evidently the links between economic growth and leadership in science are not short and simple. Western scientific and economic advance are separated not only in time [by 150 or 200 years between Galileo and the beginnings of the industrial revolution], but also by the fact that until about 1875, or even later, the technology used in the economies of the West was mostly traceable to individuals who were not scientists, and who often had little scientific training. The occupational separation between science and industry was substantially complete except for chemists. (Rosenberg and Birdzell 1986: 242)

On the other hand, Newton believed in alchemy; and in one example of the use of scientific measure in Europe, the Venetian Giovan Maria Bonardo found in his 1589 study, The Size and Distance of All Spheres Reduced to Our Miles, that “hell is 3,758 and 1/4 miles from us and has a width of 2,505 and 1/2 miles [while] Heaven is 1,799,995,500 miles away from us” (cited in Cipolla 1976: 226).

So the overwhelming evidence is that the alleged contribution of seventeenth-, eighteenth-, or even early nineteenth-century science to technology or to the industrial revolution is no more than “mythology” as Kuhn aptly termed it. And so what is the relevance of this entire “Great Question” about the seventeenth-century “scientific revolution” to our other “Grand Question” about “the Decline of the East” and “the (temporary) Rise of the West”? Not much, at least not within our present time frame before 1800. Therefore, it is just as well and most welcome that Cohen (1994: 500) himself ends by asking “Is the (fifty-year old concept of the) ‘Scientific Revolution' going the way of all historical concepts?” “Perhaps” he answers, for “the concept has by now fulfilled its once useful services; the time has come to discard it. After all, historical concepts are nothing but metaphors, which one should beware to reify.” Amen!

Except alas, not so fast: this Eurocentric mythology still seems to be alive and well also among Asians, whose resulting distortions of developments in science and technology are even more alarming. For instance, Aniruddha Roy and S. K. Bagchi (1986: v) call Irfan Habib a pioneer in medieval technology studies in India. Yet Ahsan Qaisar (1982) records his deep gratitude to Habib for suggesting his own research in The Indian Response to European Technology and Culture (A.D. 1498–1707). Indeed, Habib himself also contributes a chapter on the same theme to the book edited by Roy and Bagchi. Elsewhere, Habib (1969:1) himself writes that “it would be foolish, even if detailed evidence has not been studied, to deny that India during the seventeenth century had been definitely surpassed by Western Europe [in technology]. ” Habib does bring some of the evidence, to be examined below. As we observed in chapter 3, Prakash (1994) disputes much of Habib's reasoning and himself disputes many alleged differences between Asia and Europe and avows that Asia played a widely underestimated key role in the early modern world economy. Yet even Prakash (1995: 6) writes that “Europe had an undoubted overall superiority over Asia in the field of scientific and technical knowledge.”

Roy McLeod and Deepak Kumar (1995) also inquire into Western technology and its transfer to India from 1700 to 1947; despite the 1700 date in their subtitle, they explicitly disclaim any attention to the precolonial era; and yet, as we note below, some of their contributors (Inkster, Sanpal) do deal with that period. Even so, the editors permit themselves to introduce their book with unsubstantiated claims that are challenged by the evidence—cited below—from at least one of their own contributors. Yet the editors write that “technological change” in pre-British India “certainly was no match to what was happening in Europe. The whole technical process was skill-and craft-oriented [but not so in Europe, we may ask]; the output was excellent (for example, in steel and textile), but limited to local markets [if so, how then did India dominate world markets, we may ask]. European travellers…were wonder-struck by some Indian products, but invariably critical of Indian customs” (McLeod and Kumar 1995: 11–12). Yet, even their first contributor, Ian Inkster examines and rejects arguments of India's alleged inferiority on cultural grounds. The editors claim that these and other “prefixes” (better prejudices!) “point to the weakness of the Indian economy as compared to proto-industrial Europe, Tokugawa Japan, or even Ming China” (McLeod and Kumar 1995: 12). Alas, they see reality in reverse; for, on all the evidence in the present book, the order of economic “weakness” and strength was the reverse, with China strongest, Europe weakest, and Japan and India in between.

What is noteworthy is that all of these texts by Asian scholars inquire only into technological diffusion from Europe to India and its selective adoption there—not the other way around. Yet as we will note below, diffusion went in both directions; and adoption and adaptation in both places as well as elsewhere responded to common world economic development mediated by local circumstances.

For China, Joseph Needham's (1954-) monumental multivolume Science and Civilization in China is well known, although perhaps insufficiently examined because of its large bulk and detail. A four-volume extract has been prepared by Colin Ronan (1986), and Needham (1964) himself has written a summary, “Science and China's Influence on the World.” He explicitly challenges the dismissal by others: “In technological influence before and during the Renaissance China occupies a quite dominating position…. The world owes far more to the resilient craftsmen of ancient and medieval China than to Alexandrian mechanics, articulate theoreticians though they were” (Needham 1964: 238). Needham lists not only the well-known Chinese inventions of gunpowder, paper and printing, and the compass. He also examines co-fusion and oxygenation iron and steel technology, mechanical clocks, and engineering devices such as drive-belts and chain-drive methods of converting rotary to rectilinear motion, segmental arch and iron-chain suspension bridges, deep-drilling equipment; and paddle-wheel boats, foresails and aft sails, watertight compartments and sternpost rudders in navigation, and many others.

Moreover, Needham insists that scientific investigation was well accepted and supported and that technological innovation and its application continued through the early modern period, also in fields like astronomy and cosmology, and in medical fields like anatomy, immunology, and pharmacology. Needham explicitly denies the European notion that the Chinese only invented things but did not wish to or know how to apply them in practice. Although he examines some apparently parallel developments in East and West, he also speculates on the possible channels and extent of their mutual influence and interchange.

There are also similar studies and findings for India, albeit on a lesser scale than Needham's monumental work. For instance, G. Kuppuram and K. Kumudamani (1990) have published a history of science and technology in India in twelve volumes, and A. Rahman (1984) has edited another collection on the same topic. Both works testify to the continued development of science and technology in India not only before 1500 but also since then. Dharampal (1971) collected eighteenth-century accounts by Europeans, who testify to their interest in and profit from Indian science and technology. Indian mathematics and astronomy were sufficiently advanced for Europeans to import astronomical tables and related works from India in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In medicine, the theory and practice of inoculation against smallpox came from India. The export of Indian science and technology relating to shipbuilding, textiles, and metallurgy are noted below.

Similarly, S. H. Nasr (1976) and Ahmand al-Hassan and Donald Hill (1986) have written and edited histories testifying to the development and diffusion of Islamic science and technology from the earliest to recent times. George Saliba (1996) provides multiple examples of important Arab scientific influences on the Renaissance, not only before and during this period but into the seventeenth century. Only one example from Saliba is that Copernicus knew and had documents about Arab theories, which made crucial inputs to his own “revolution.”

So it is not enough to just go on “granting the immense European naval and military superiority,” as does Singer, or claiming that it “would be foolish, even if detailed evidence has not been studied, to deny” European technological superiority in other fields, as does Habib. Better to examine the evidence of Asian capacities with a bit more care, as Goody (1996) and Blaut (1997) begin to do, especially in these two fields. Another area of superiority mentioned in Singer's history of technology are coal and iron, while Habib and others also refer to printing and textiles. Upon any inspection, not only will we find that technology was far “advanced” in many parts of Asia, but it continued to develop in the centuries after 1400. That was the case especially in the globally more competitive military and naval technologies. Moreover, the alleged “Ottoman decline” is contradicted by a comparative examination of technologies in precisely these two areas (Grant 1996), as chapters 5 and 6 show in other respects as well. However, advanced technologies were also the case in more “local” arenas such as hydraulic engineering and other public works, iron working and other metallurgy (including armaments and especially steel-making), paper and printing, and of course in other export industries such as ceramics and textiles.

Guns. I say “other” export industries because arms and shipbuilding were important export industries. Not for nothing have the Ottomans, Mughals, and the Chinese Ming/Qing been termed “gunpowder empires” (McNeill 1989). They developed the latest and best in armaments and other military technology, which every ruling elite in the world sought to buy or copy it if it could use and afford it (Pacey 1990; see also chapter 5). Nonetheless, both Cipolla (1967) in his Guns and Sails and McNeill (1989) in his The Age of Gunpowder Empires 14S0–1800 repeatedly claim that European guns, especially when mounted on ships, were and remained far superior to any others in the world.

On the other hand, both Cipolla and McNeill themselves bring some contrary evidence. Both discuss the rapid development of Ottoman military technology and power. The Ottomans (but also the Thais) excelled in arms production, as Europeans and Indians recognized and also copied, adapting and reproducing Ottoman small and large arms technology to their own circumstances and needs. “Until about 1600, therefore, the Ottoman army remained technically and in every other way in the very forefront of military proficiency,” avers McNeill (1989: 33). Cipolla (1967) acknowledges the same high degree of Ottoman military technology in his Chapter 2, and Jonathan Grant's (1996) comparative examinations confirm it. Although all three authors signal Ottoman military weaknesses (and defeat against Russia) in the seventeenth century, the first two also stress that European development of military technology could not begin to shift the balance of land-based power anywhere in Asia before the second half of the eighteenth century.

On the seas and at the coasts, their naval artillery did give Europeans some military technical advantages, but never enough to impose even a small part of the economic monopoly they sought, as Cipolla and McNeill also recognize. The Ottoman Sultan said that even the 1571 European naval victory at Lepanto only singed his beard (quoted in Cipolla 1967: 101). The Portuguese sixteenth-century incursions in the Arabian Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the China Sea, using their bases at Hormuz, Goa, and Macao respectively, were only limited and temporary. The seventeenth-century Dutch offensive did much to displace the Portuguese but failed to impose the monopoly they sought in Asian waters, even in “Dutch” Southeast Asia, as we observed above.

Nor did their guns afford the Europeans any significant military impact in or on China and Japan, although there was some reverse diffusion of artillery technology. The Eurocentric fable that Chinese invented gunpowder but did not know how to use it is completely belied by Needham's (1981) evidence. He details widespread Chinese military use of powder for propulsion and also in incendiary devices and flamethrowers since at least A.D. 1000. Moreover, the Chinese also developed and used rockets with fifty and more projectiles, including two-stage rockets whose second propulsion was ignited after the first stage was in the air. Originally, the rocket launchers were stationary, but then they were made mobile as well. Europeans did not put gunpowder to military use until the late thirteenth century, and then only after they had themselves been victimized by the same in the eastern Mediterranean. Similarly, the Chinese and the Japanese also rapidly adopted and adapted advanced foreign gun technology, as Geoffrey Parker (1991) describes: