2 Portrait of My Father, 1955

David Hockney has commanded greater popular acclaim than any other British artist of this century. Born in Bradford, Yorkshire, in 1937, he had acquired a national reputation by the time he left London’s Royal College of Art with the gold medal for his year in 1962. The artists with whom he was associated at the College, notably R. B. Kitaj, Allen Jones, Peter Phillips, Derek Boshier and Patrick Caulfield, heralded by the press as the young stars of British Pop Art, all enjoyed early success, but Hockney from the start was in a category of his own. In 1961 he was awarded a prize for etching at the ‘Graven Image’ exhibition in London, as well as a painting prize at the John Moores Liverpool Exhibition. Before finishing his studies he had already been approached by a Bond Street dealer, John Kasmin, with whom he had his first one-man show in 1963, aged only twenty-six. In 1967 he was awarded first prize in the John Moores Exhibition, and three years later he was honoured with the first of several major retrospectives which have established his reputation internationally. His works now fetch higher prices than those of almost any living British artist.

It is doubtful whether any British artist since the Second World War has attracted so much newspaper coverage and been the subject of so many interviews. A number of substantial catalogues and specialized studies have been produced about his work. Hockney himself has published two volumes combining autobiography with theory (1976 and 1993), a picture book in paperback (1979), and monographs devoted to his Paper Pools series (1980) and to his trip to China (1982), all originating with the same British publisher, Thames & Hudson.

The present study might be regarded as yet another instance of the way in which the Hockney promotional enterprise has been fed. Surprisingly, however, for an artist who has been the centre of so much attention, this is the first critical study of his work. In view of the public’s interest in Hockney’s art, one can legitimately ask why no other book, nor even any substantial articles, appeared until well into the 1980s. Was it that Hockney was acceptable only as a social phenomenon rather than as a serious artist? Did other writers and publishers consider that their reputation might be discredited if they concerned themselves with his work?

Since the time of Courbet and increasingly during our own century, the committed artist has been considered to be in opposition to the taste of his time. In his essay on The Dehumanization of Art (1925), José Ortega y Gasset proposed the view, now widely accepted in the art world, that serious new art is not only unpopular but essentially ‘anti-popular’. In these terms, serious achievement in art is measured in inverse proportion to its popularity, for the two have been defined as incompatible.

Hockney’s work appeals to a great many people who might otherwise display little interest in art. It may be that they are attracted to it because it is figurative and, therefore, easily accessible on one level, or because the subject-matter of leisure and exoticism provides an escape from the mundanities of everyday life. Perhaps it is not even the art that interests some people, but Hockney’s engaging personality and the verbal wit that makes him such good copy for the newspapers. He may, in other words, be popular for the wrong reasons. But does this negate the possibility that his art has a serious sense of purpose?

In the view of some respected critics, such as Douglas Cooper, Hockney is nothing more than an overrated minor artist. To this one can counter that Hockney might seem minor because it is unacceptable today to be so popular, rather than because his work is lacking in substance. Hockney himself is not self-deluding; he is aware of his limitations and thinks that it is beside the point to dismiss his work because it does not measure up to an abstract concept of greatness. Hockney does not claim to be a great artist and is aware that only posterity can form a final judgment on his stature.

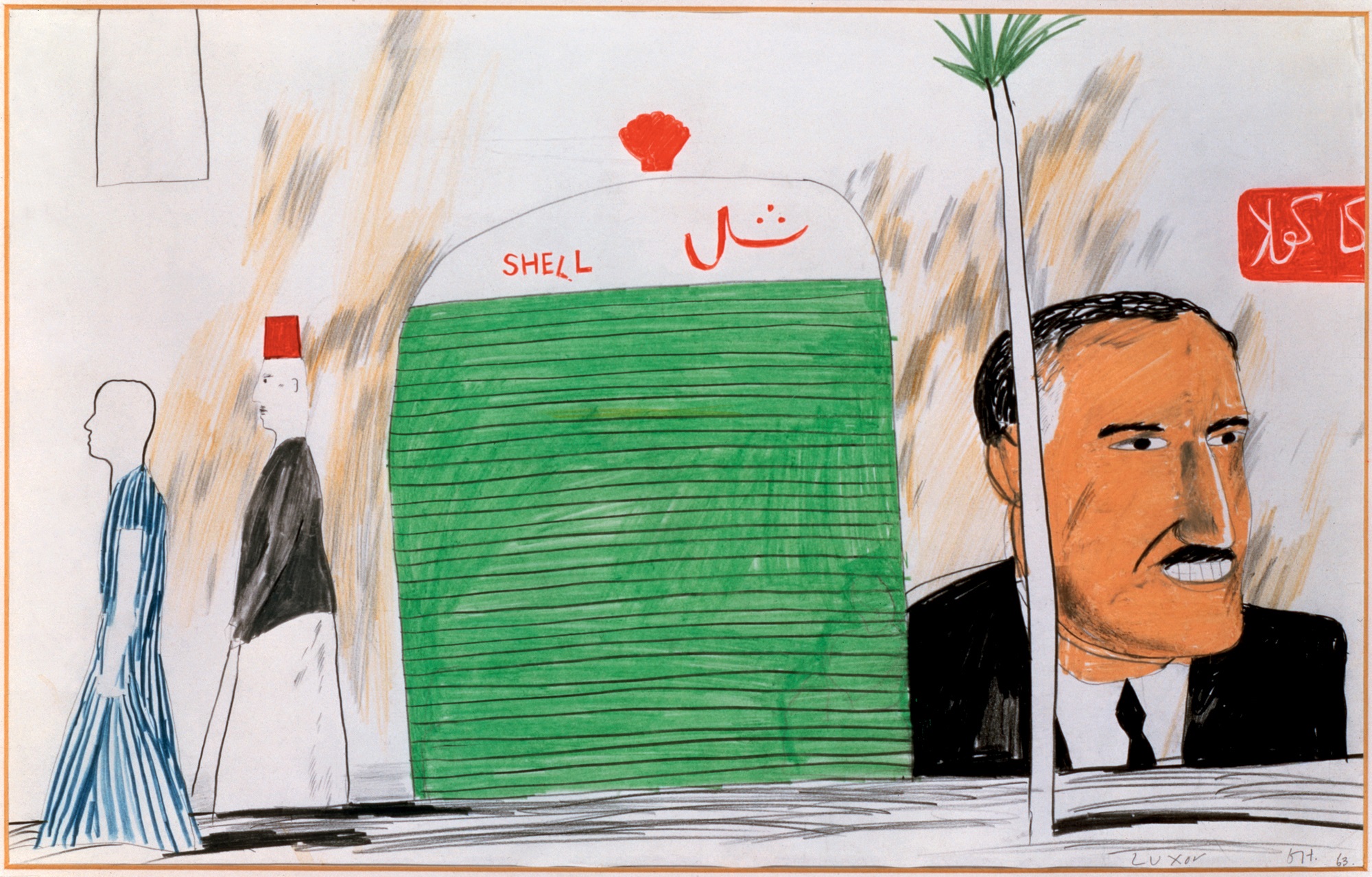

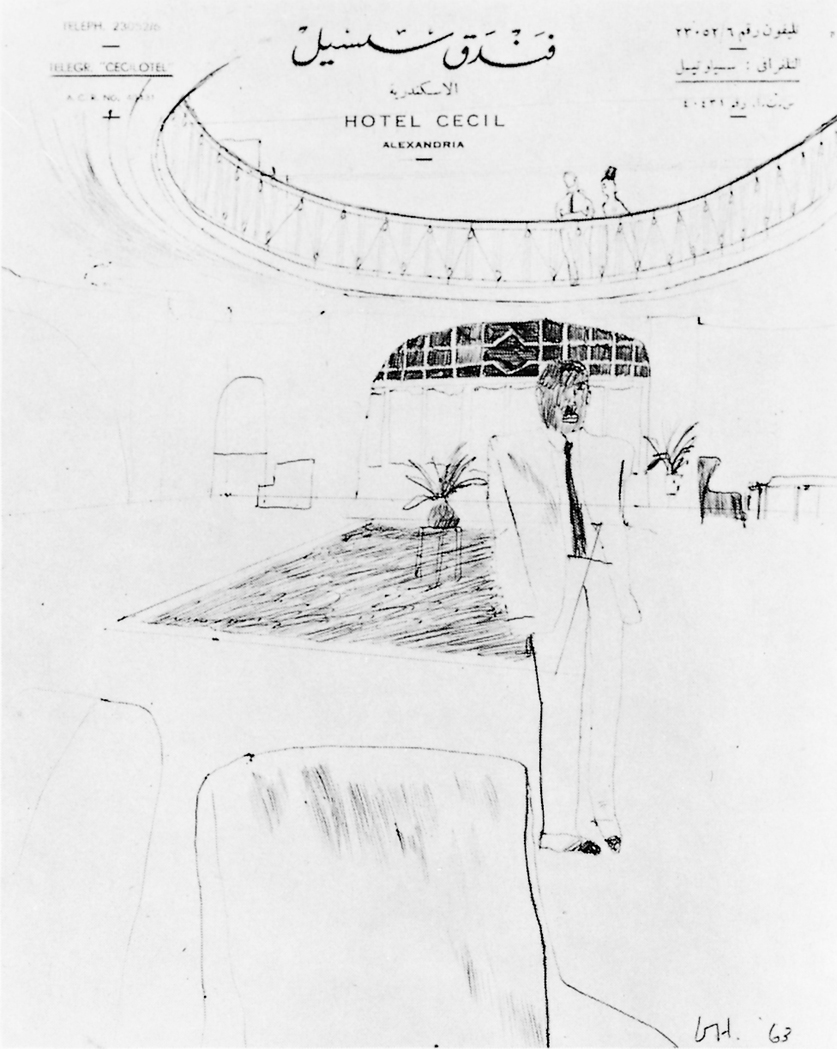

It has been said that Hockney’s work is shallow because of the life he leads and the people with whom he surrounds himself. Hockney is aware of this charge but finds it incomprehensible: ‘I know some people think one leads a glamorous life, but I must admit I’ve never felt that myself. Even when you’re sat here in Hollywood with a swimming pool out there, I still feel my life is just as a working artist, actually. That’s the way I see it.’ He feels no particular need to demonstrate his cultural credentials or political awareness in his work, although he is extremely well informed not only about current events but also about literature, music and the arts generally. The accusation that his world view is vacuous and circumscribed is based primarily on the drawings which he has produced in luxury hotels on his travels round the globe [123, 129]. It would be highly misleading, however, to base one’s estimation of Hockney’s art on such drawings, which he himself regards as a pastime peripheral to his main concerns. It is not unusual for an artist today to travel or to stay in luxury hotels, but Hockney is rare in spending his quiet moments drawing, through his very devotion to the activity. It would be wrong to condemn him for wanting to produce art in most of his waking hours.

Perhaps the most serious criticism of Hockney as an artist is that he makes superficial gestures towards Modernism as an illustrator would, rather than committing himself fully to a Modernist approach. Hockney recognizes the extent to which his own work has been conditioned by Modernism, which he regards as ‘one of the golden ages of art’, but takes issue with what he regards as the academicism of what is known as Late Modernist art. It may be that Hockney is trying to reconcile two things which in our own day would seem to be irreconcilable: serious aesthetic intentions and ease of communication with people outside the art world. It is a dangerous task, but one that is worth pursuing if the artist is to retrieve his position as a working member of society at a time when his isolation has reached an almost intolerable level.

Hockney’s popularity and commercial success, even if they have not destroyed his integrity, have nevertheless proved an inhibiting force. ‘There comes a point where you see it all as completely empty,’ says Hockney, ‘being a popular artist to the extent that people who are not necessarily interested in art know about things or take some little interest. I think that now for me it’s a burden. It’s a bit hard to deal with, and it wastes time as well.’ It is partly to escape the public glare that Hockney feels compelled to keep changing his country of residence, moving each time that he finds the social pressures have become too difficult to bear. Inevitably his work charts the path of his life, not only from place to place but also as a withdrawal into a private world populated mainly by close friends.

Hockney, of course, is not wholly blameless for the situation in which he finds himself. His decision to dye his hair blond during his visit to New York in 1961, for instance, is indicative of his desire to be noticed both as a person and as an artist. He ‘reinvented’ himself, to use his own term, in a sense making himself the trademark with which to market his work.

The confusion between man and work implied in the personal act of dyeing his hair is not altogether inappropriate, since to an unusual degree Hockney has consistently based his art directly on his experiences and on his relationships with other people. To dwell on biographical details, however, would be to promote further the serious misrepresentation of Hockney as a colourful personality rather than as a committed artist. As one of those rare painters who is as well known for who he is as for what he has achieved, he has suffered in terms of credibility in that his social role has tended until now to obscure the importance of the art. The popular appeal and easy seductiveness of that art have likewise masked its sense of purpose. It is necessary to redress the balance.

2 Portrait of My Father, 1955

Hockney’s astonishing self-confidence, nevertheless, provides a key to understanding his development. The bravado is evident in the generic title of his last student paintings, exhibited as a group in the 1962 ‘Young Contemporaries’ exhibition in London: Demonstrations of Versatility [27, 28, 29]. It is a phrase, however, which also reveals the paradoxical coherence of his work at that time [29, 30]. In these pictures Hockney insisted that any style could be chosen at will, that any form of representation, any type of image, any subject or theme was fit material for a picture. Like some of his colleagues at the Royal College of Art, Hockney was in search of a ‘marriage of styles’ that would free him from the limitations of any one way of picturing the world.

Unlike the change of Hockney’s hair colour, the declaration of freedom and detachment in his art was not achieved overnight. His decision to play with style was conditioned to a large degree by his own earlier history and training. It was because he had already experienced the strait-jacket of subservience to particular styles that he especially welcomed the prospect of emancipation through the deployment of contradictory modes.

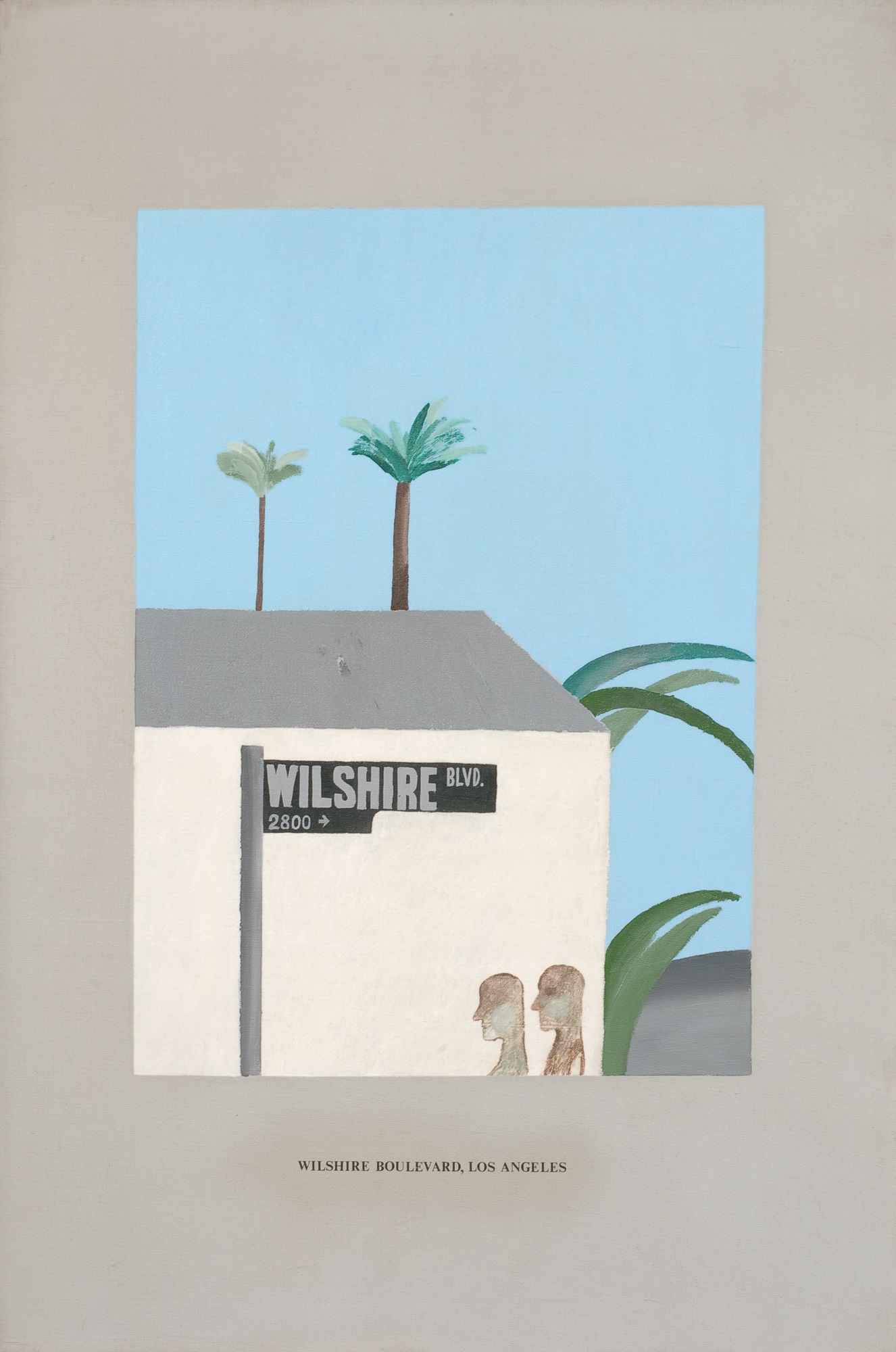

As a teenager in the mid- to late 1950s, Hockney, like many art students, experimented with various ways of making pictures, seeking a single workable process but ending, through restlessness and changes of heart, with a diverse and apparently contradictory body of work. At Bradford School of Art from 1953 to 1957 Hockney received a traditional training which inculcated a respect for close observation from life, for subdued handling of paint surface and colour, and for drawing as the essential process for transferring perceived sensations to canvas. The works made at this time betray an unfailing devotion to the motif, whether this be a cityscape of his native town or a portrait from life [2, 3].

The task underlying all of Hockney’s Bradford pictures is that of finding an equivalent in paint for what the eye can see. In the best of these pictures, notably the 1955 portrait of his father, elegant and accurate draughtsmanship is the essential ingredient in the construction of the picture. Paint is merely a vehicle for the conveyance of an image. Variations in the application of the paint, generally thinly applied, add surface interest, but colour is subdued in order to emphasize the subtlety of tonal variation. This method of working, as well as the insistence on finding all suitable subjects in one’s daily life and immediate environment, owes much to the teaching practices established in the 1930s by the so-called Euston Road artists such as William Coldstream, Victor Pasmore and Claude Rogers. Walter Sickert and Edgar Degas were the most modern painters held up as models at provincial schools such as Bradford, and training was based firmly on the traditional academic practice of drawing from life, an activity which greatly appealed to Hockney from the beginning and which he regards as vital to all his later work. To Hockney, drawing has always been a means of learning how to look, as well as a method of making marks in which the immediacy of the image takes precedence over self-consciousness of style.

3 Moorside Road, Fagley, 1956

Hockney appears at the time to have taken the Euston Road approach for granted, simply because in a town like Bradford in the 1950s there was little opportunity for studying contemporary art, and no clear alternatives were immediately available. It was primarily through reproductions in books that other paintings could be seen. Inevitably his awareness was bound to be limited mostly to the work of recognized earlier masters, and then only as something quite remote from his own immediate experience at art school, and to established contemporary figures such as Stanley Spencer.

The exhibition held in 1958 at Wakefield of the work of Alan Davie, recently a Gregory Fellow at Leeds, struck him as a revelation and increased his appetite for modern art. He seems to have realized at once that he had been a slave to a style which was only one of many possible approaches. Paintings by Davie such as Discovery of the Staff, 1957 [4], were influenced by American Abstract Expressionism (at that time still little known in Britain outside the capital) and particularly by Jackson Pollock, and consisted of a pared-down imagery of archetypes which to Hockney appeared to be essentially abstract. Here was Modernism as a living alternative to the kind of art he was being taught to make. Instead of working from the motif and emphasizing the image as the essential fact, one could take a completely opposite approach, inventing images from the imagination and concentrating on the accumulation of paint on canvas as the immediate reality for conveying sensation to the viewer. A painting, he now recognized, need not be a passive receiver of information about the visible world, but may adopt a far more aggressive role in providing the actual impetus to the viewer’s experience.

4 Alan Davie Discovery of the Staff, 1957

Hockney had no real opportunity to paint during his two years as a conscientious objector in the National Service, from 1957 to 1959, which he spent working in hospitals at Bradford and Hastings. When he took up his brushes again as a post-graduate student at the Royal College of Art in the autumn of 1959, the example of Davie’s work, and of other British abstract painters such as Roger Hilton, seems to have been uppermost in his mind. By this time he had seen the Jackson Pollock retrospective held at the Whitechapel Gallery and had heard about, though not visited, ‘The New American Painting’ exhibition shown at the Tate Gallery in February–March 1959. Both these shows of contemporary American art seem to have increased his ambition to be a ‘modern’ artist, even if there was little in their work which he wished to apply directly to his own.

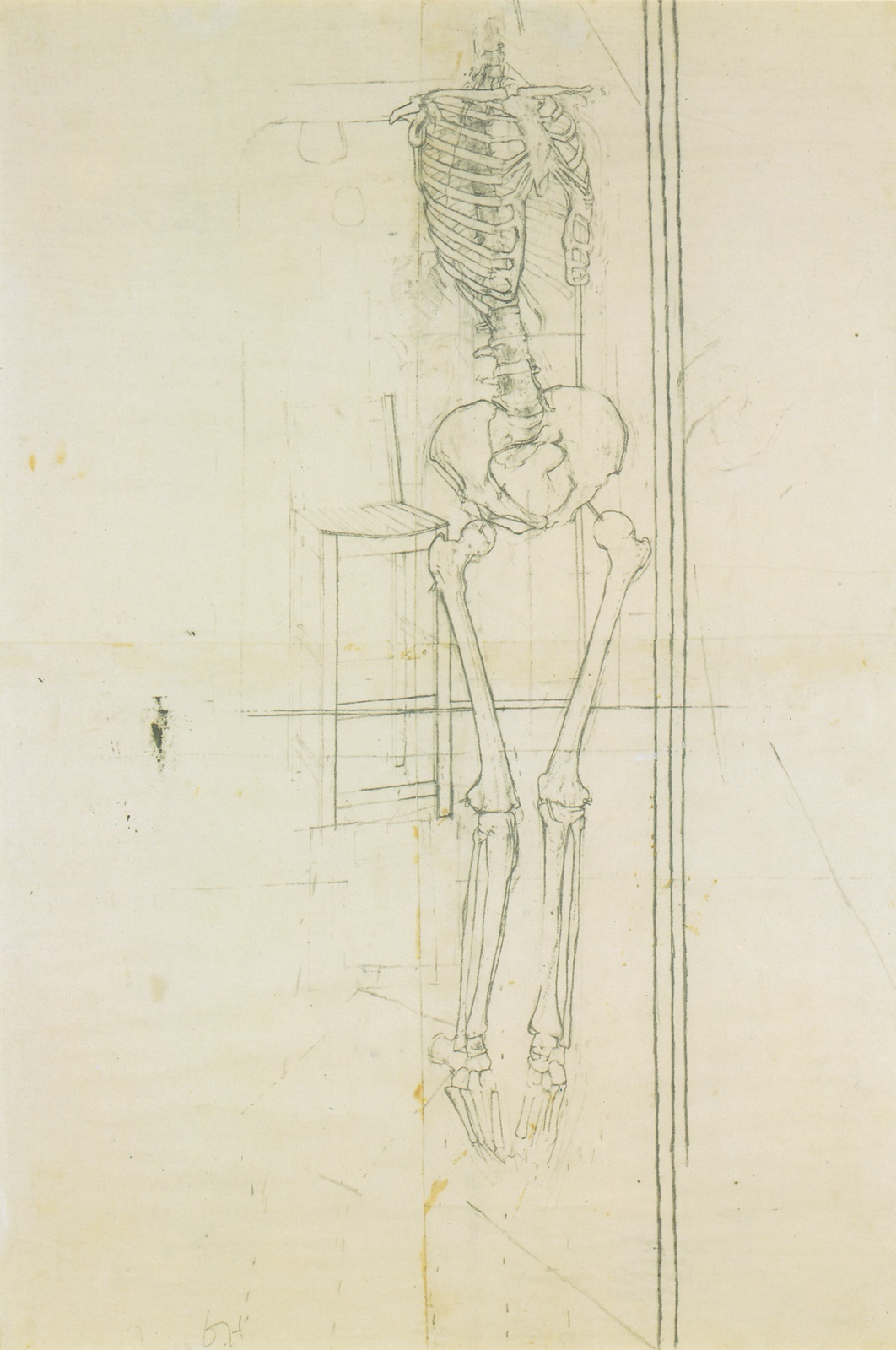

Having spent two years away from painting, Hockney was uncertain about what to do on his arrival at the Royal College and spent the first month there making two elaborate drawings, one in pencil and the other with turpentine washes, of a skeleton hanging in the room [5]. These were not intended as works of art but simply as an exercise in self-discipline along the lines of his previous art school training, a method of educating the eye and the hand. The painstaking accuracy and worked-over appearance of these large drawings based on close observation are the very antithesis of the spontaneously painted abstract pictures which followed.

For a short period during his first term, Hockney investigated the possibility of painting pictures which were totally non-referential. Painted generally on three-by-four-foot board issued by the College, these were larger than most of his previous pictures, although they stopped far short of the ambitious mural-like scale favoured by American artists of Pollock’s generation. In part this can be attributed to the fact that this was the largest size board available free from the College, but it is due also to the fact that Hockney was taking as his point of reference not American but British abstract painting of the 1950s, which was conceived still within the tradition of the easel picture.

5 Skeleton, 1959

Growing Discontent, which dates from the winter of 1959–60 [6], is a characteristic example of Hockney’s abstract pictures. Few of these paintings survive, as many were either destroyed or painted over by Hockney or by other students who had run out of supplies of hardboard. Hockney disliked the fashion for anonymous titles such as Painting No. 1, a practice he soon parodied in his series of Love Paintings, and thus chose evocative captions that would identify the picture more vividly. These titles are often drawn from poetry. Sometimes the name of the painting would relate closely to its content, as in the case of the slightly later Tyger, 1960 [7], which alludes to the William Blake poem ‘The Tyger’ from Songs of Experience; the two wedgelike forms are the last vestiges of a schematized tiger more clearly recognizable in a drawing produced by Hockney shortly before. The titles of other pictures from this period are less literally related to the forms on that piece of hardboard or canvas, but allude more generally to Hockney’s attitudes or situation as a human being. Another painting from this winter term, for instance, was called Erection, hinting for the first time at the theme of sexuality with which he was soon to be concerned, though one would look in vain for anything but the most abstruse erotic meanings in the imagery itself.

6 Growing Discontent, 1959–60

7 Tyger, 1960

Hockney’s increasing dissatisfaction with his own art is firmly stated in the title Growing Discontent. He was beginning to understand that in his eagerness to embrace Modernism whole-heartedly he had abandoned the content and subject-matter of his earlier figurative paintings. Worse yet, he had thrown off one stylistic strait-jacket only to find himself trapped in another. Having experienced this sense of confinement before, he was quicker to recognize it this time and to become aware of the need to find a personal voice. Various influences were soon to help him to the conclusion that style should not be imposed on the artist, but that it should simply be one of many tools at his service.

Each of the two phases of Hockney’s work of the 1950s was rejected as insufficient on its own, yet there were elements of each that he wished to retain. In the simplest terms, he rejected the extreme of abstract formalism as lacking in human content, while shying away from a traditional conception of figurative art as old-fashioned. He felt a need for subject-matter and recognizable imagery in his own pictures as a means of engaging the viewer’s interest, but was intent on demonstrating his awareness of the issues of modern art.

8 R. B. Kitaj The Red Banquet, 1960

Hockney was not alone in his urge to devise a figurative art which took into account the lessons of Modernism while dealing with a wide range of subject-matter normally considered outside the domain of painting itself. There were, in fact, several other students in his year at the Royal College who shared similar aims, foremost among them the American R. B. Kitaj [8], whose work and attitudes had a strong impact on Hockney as well as on painters such as Allen Jones, Peter Phillips and Derek Boshier. Kitaj’s work revealed ways in which picture-making could, and should, be a vehicle for intellectual as well as sensual communication. The making of images was viewed as the construction of a language of signs which would be ‘read’ in the way that words can be read. Kitaj was interested, furthermore, in the Surrealist notion of automatism and in the Abstract Expressionist corollary, the concept of gesture, both of which seized on image-making as a kind of writing expressive of the functioning of thought or of the assertion of personality.

Troubled by the apparent lack of content in abstract art, but not yet ready to reassert figurative references for fear of appearing reactionary, Hockney found in words a way of communicating specific messages without confronting the dilemma of illusionism. The idea was suggested to him by Cubist pictures in which words were written on the canvas as a substitute for, or as a clue to the identity of, objects and environments that would otherwise be difficult to decipher. It is a way of bringing in the rest of the world while maintaining the literal identity of all the marks on the canvas; a picture of something is not the thing itself, whereas a word, while alluding to another level of experience, retains the same form whether it is written on a sheet of paper or transcribed on to the surface of a painting.

When Hockney began writing on his paintings it was with the intention of communicating his interests to others. Poetry often supplied him with the words he needed; it seemed to Hockney that poetry involved a process of selection, distillation and allusion which was similar to that he was seeking in his painting. Tyger [7], borrowed from the poem by William Blake, was the first occasion on which he wrote on one of his paintings. Following this came a series of pictures still resembling his abstract paintings but including patches of red and green as signs for tomatoes and lettuce, as well as words such as ‘carrots’ and ‘lettuce’ as part of his self-declaration as a vegetarian. These paintings have all disappeared, the victims again of repainting or of systematic end-of-year disposal by the College staff.

At about the same time that he was painting the ‘vegetarian propaganda’ pictures, Hockney began, hesitantly at first, to treat another, even more personal theme: that of his homosexuality. Second Love Painting [9], a tiny canvas painted at the end of his first year at the College, introduces the subject by pairing an image of a heart with the word ‘LOVE’ written in small letters along its lower edge. The debt to Alan Davie is still visible, especially in the gestural brushwork, dry paint surface and colour scheme of deep reds and blues, yet the cryptic and very private aspects of his abstract work are now beginning to give way to a much greater openness.

It was precisely at this time that Hockney began to acknowledge publicly his homosexual orientation, largely under the encouragement of another American student at the College, Mark Berger. No longer afraid of being ‘discovered’, Hockney did not need to hide his impulses in abstract visual symbols; his new sense of confidence seems to have liberated his search for a greater directness than had been possible before. In the space of a few months he changed from a quiet introspection to a flamboyant gregariousness, and the hermetic, sombre nature of his earlier work gave way to an almost hectic exuberance. Hockney agrees that his first overtly figurative paintings following his abstract phase were those that dealt with his ‘coming out’, and is at pains to insist that it was in fact through his art that he made his declaration:

‘The openness was through the paintings, it wasn’t through anything else. In those days I didn’t talk very much. I was aware that I was homosexual long before that, it’s just that I hadn’t done anything about it. I mean I had done a little about it when I was very young, but then you didn’t worry about it, you didn’t think it was anything odd at all. The more you become aware of it, at first it simply seems quite private, and then the more aware of that you become, the more secretive you become. You’ve lost the innocence of not caring at all. Then the moment you decide you have to face what you’re like, you get so excited, it’s something off your back. I don’t care what they think at all now. In a sense, oddly enough, it kind of normalizes you.’

Unlike some of the other students, Hockney did most of his painting at the College, and relished the constant flow of people, among them some slightly older artists such as Peter Blake and Joe Tilson, who visited the studios. To Hockney this created a situation akin to a permanent exhibition, and the expectation of an instant public made him think of his pictures as messages to others rather than as private exercises. He was eager to tell others about himself, and saw that he could do this through his art. It was also a discovery that filled him with excitement and which accounts for the rather aggressive self-assertion of the various vegetarian and homosexual propaganda pictures:

9 Second Love Painting, 1960

‘I think it was both propaganda in the ordinary sense of the word, it was cheeky, and there was also an element of just ordinary excitement that you could deal with these things, that you’d reached a point where you could make paintings about these things for yourself. Painting in Bradford in the streets you’re not dealing with anything like that at all. The moment you learn to deal with it in art, it’s quite an exciting moment, just as in a sense when people “come out” it’s quite an exciting moment. It means they become aware of their desires and deal with them in a reasonably honest way.’

The change of approach in Hockney’s work from private messages to open declarations is most clearly evinced in a series of paintings on the theme of homosexual self-oppression, beginning with a tiny picture called Queer [10] and culminating in the clearly legible figurative imagery of the final version of Doll Boy in the late summer of 1960. The sequence of pictures reveals the gradual evolution of a hunched-over male figure, explicitly labelled ‘unorthodox lover’ in one of the studies and identified by the slang term ‘queen’ in another study and in the final painting.

10 Queer, 1960

At first sight Queer looks much like Hockney’s slightly earlier abstracts, and indeed when it was exhibited at a commercial gallery in London five years later it was listed as Yellow Abstract, a title which Hockney himself would never have chosen. Barely visible in the centre of the picture, more evident in reproduction than in the painting itself, is a series of scrawled forms which can gradually be seen to make up the derogatory label of the title. The minute size of the picture and the presence of the written message beckons the viewer closer and incites him to scrutinize the surface, which is a thick and dry mixture of oil paint with sand. The words thus have two functions, that of transmitting a message and – a basic goal of the modern artist – that of making the viewer aware of the material composition of the image as paint on canvas. If one stands close enough to these pictures to read the messages, it is possible to lose sight of the images as they seem to disappear into the deliberately rough surfaces of paint, so that one’s consciousness of the tactile qualities of the manipulated paint is increased.

The identification of the brown smudged area in the lower section of Queer becomes possible if one compares it with one of the studies for Doll Boy executed shortly afterwards [11]. The arch surmounted by a blotch can now be read as a male figure, pushed down by the weight from above as a symbol of self-oppression. The more explicit study makes clear through the graphic symbol of a heart pushing on the boy’s head that it is his own need for love which is causing him pain. The final painting retains the submissive posture of the figure yielding to the crush of antagonistic forces, but through the addition of further written phrases makes even clearer that the theme is that of the homosexual who refuses to acknowledge his orientation publicly. The words in the lower right-hand corner – ‘your love means more to me’ – suggest the graffiti found on the walls of public toilets, with all the furtiveness and isolation which that implies. The figure is identified through various codes as Cliff Richard, the pop singer on whom Hockney had a ‘crush’ at the time and whom he thought to be homosexual in spite of his wholesome image as the average boy-next-door. The numerals ‘3.18’ written under the figure identify his initials as C.R. according to the schoolboy code which Hockney borrowed from the American poet Walt Whitman, himself an outspoken homosexual: 1 = A, 2 = B, and so forth. The phrase ‘doll boy’ functions both as a term of endearment and as a reference to Richard’s recent hit song ‘Living Doll’, and musical notes emanate from his mouth.

11 Study for Doll Boy (No. 2), 1960

During the summer of 1960 a large exhibition of the work of Pablo Picasso was held at the Tate Gallery. Hockney visited it about eight times, impressed by the brilliance of Picasso’s draughtsmanship as well as by the scope of his inventions, and recalls it even today as ‘a very liberating influence’. The most important discovery for Hockney was that the artist did not need to limit himself to one kind of picture, but could move in any direction he wished. A large section of the exhibition was devoted to the series of fifty-eight canvases executed in 1957 on the theme of Las Meninas by Velázquez, all of which are characterized by an audacious mixture of styles, pictorial conventions and conceptions of space [12]. The major canvas of the series, dismissing any pretence at stylistic homogeneity, consists of a confrontation of a number of figures each in an unrelated idiom: an outlined diagrammatic figure, a cartoon character, and figures reflecting different stages of Picasso’s own development. The result is co-ordinated rather than visually indigestible not because it is unified in style but because it reveals a consistent attitude towards style. Hockney learned that ‘Style is something you can use, and you can be like a magpie, just taking what you want. The idea of the rigid style seemed to me then something you needn’t concern yourself with, it would trap you.’

Picasso’s example, combined with the stimulating atmosphere of activity among an exceptionally talented and ambitious group of students, produced in Hockney a feeling of exhilaration and limitless possibilities. ‘One has the advantage when you’re very young,’ he recalls, ‘that you’ve nothing to lose. Later on things become a burden, I think your past work sometimes becomes a burden. When you’re very young, you suddenly find this marvellous freedom, it’s quite exciting, and you’re prepared to do anything.’

12 Pablo Picasso Las Meninas, 2 October 1957

13 Jean Dubuffet Il tient la Flûte et le Couteau, 1947

It was only after Hockney’s trip to New York during the following summer that the full impact of Picasso’s free-ranging attitude to style made itself felt in his own work. He understood at once, however, how much freedom could be gained by borrowing from any source, whether this be from his own life or imagination, from poetry, from magazines and photographs, from commonplace objects or from the work of other artists. He also found an unexpected means of escaping the confines of an inflexible style. He could make his depictions in a deliberately rigid style such as that of children’s art, the characteristics of which seem to be so constant as to make invisible any sign of individual personality. This kind of anonymity was useful to Hockney at the time, for the subject-matter with which he was dealing was of such a personal and passionate nature that the paintings could otherwise have seemed a form of neurotic self-confession. Quoting a depersonalized style such as that of children’s art allowed Hockney a certain distance between himself and his subject-matter, and in so doing stressed the application of the theme not only to himself but to others in his situation.

The figure style of Hockney’s paintings from 1960 to 1962 owes much to the example of Jean Dubuffet, whose paintings of the previous two decades employed a similar crude form of drawing inspired by children’s art. Dubuffet’s work, first exhibited in London in 1955, appealed to Hockney not only for its textural paint effects but also for its use of graffiti on city walls as a public measure of private obsessions. George Butcher, who purchased Hockney’s Third Love Painting, had written, for example, of the ‘unsophisticated sources used as material for the expression of a personal vision’ in Dubuffet’s work (Art News and Review, 21 May 1960). In works such as Il tient la Flûte et le Couteau [13], the figure serves ‘as a sign, a direct hieroglyph’, like a ready-made example of an anonymous, unchanging mode of depiction merely placed in a new order by the artist.

The two figures in Adhesiveness [14], painted at the beginning of his second year in the early autumn of 1960, are of an even more schematized nature than the rather cursory doll boys which preceded them. Hockney is not interested in telling us what they look like, but only in making clear who they are and what they are doing. It is primarily on account of their spindly little legs and the single bowler hat that we recognize them as figures at all. The numerals ‘4.8’ and ‘23.23’ identify them as Hockney himself with the poet Walt Whitman, whose complete works Hockney had read during that summer. The picture is, in fact, a celebration of love between men expressed as an act of homage to Whitman and his writings. The figures are locked in the sexual position called ‘69’ with such involvement that it hardly seems to matter that the figure at the left has legs where his head should be. The sense of complete immersion in each other is reflected in the title, a term borrowed from Whitman expressive of closely bonded friendship between men.

14 Adhesiveness, 1960

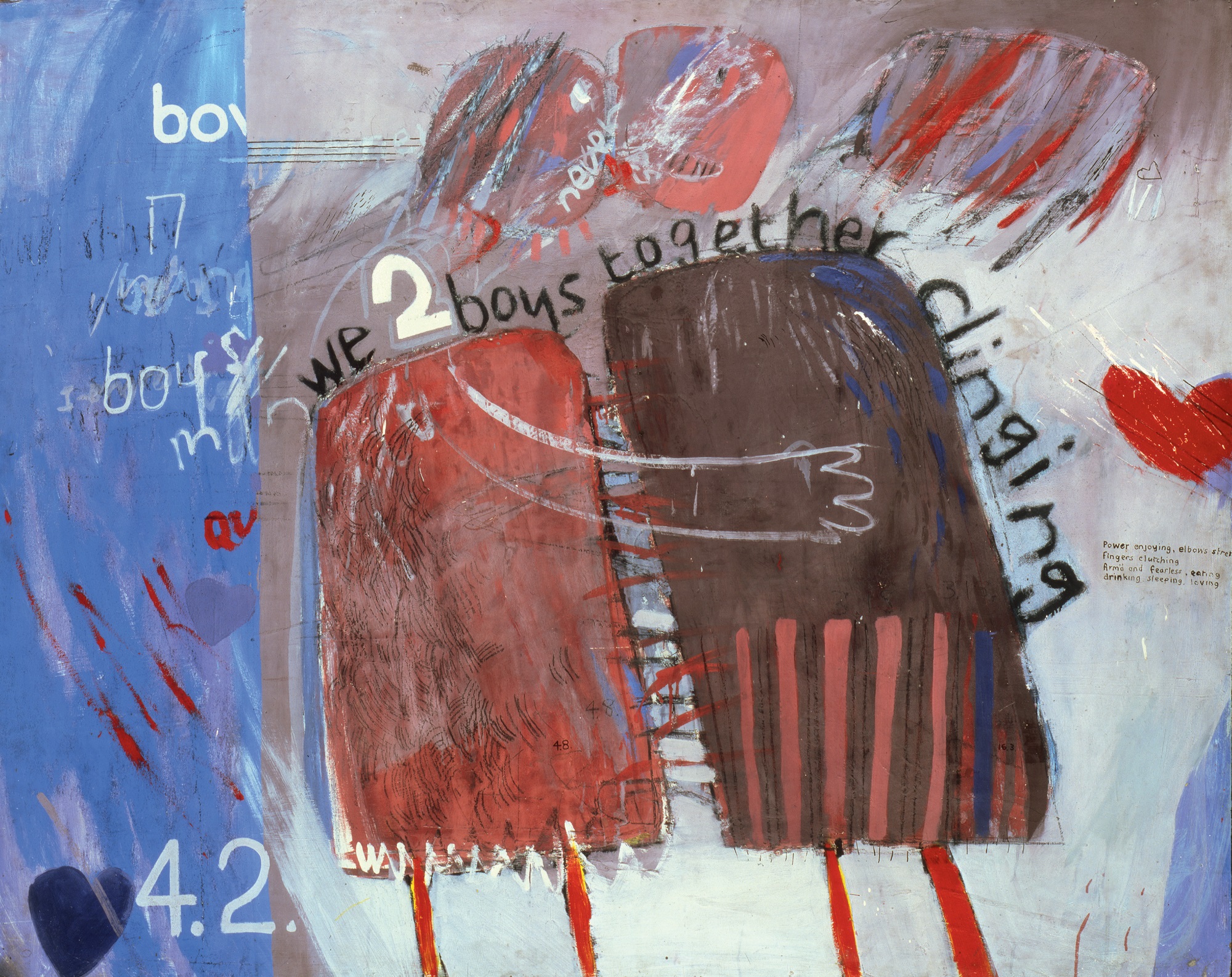

15 We Two Boys Together Clinging, 1961

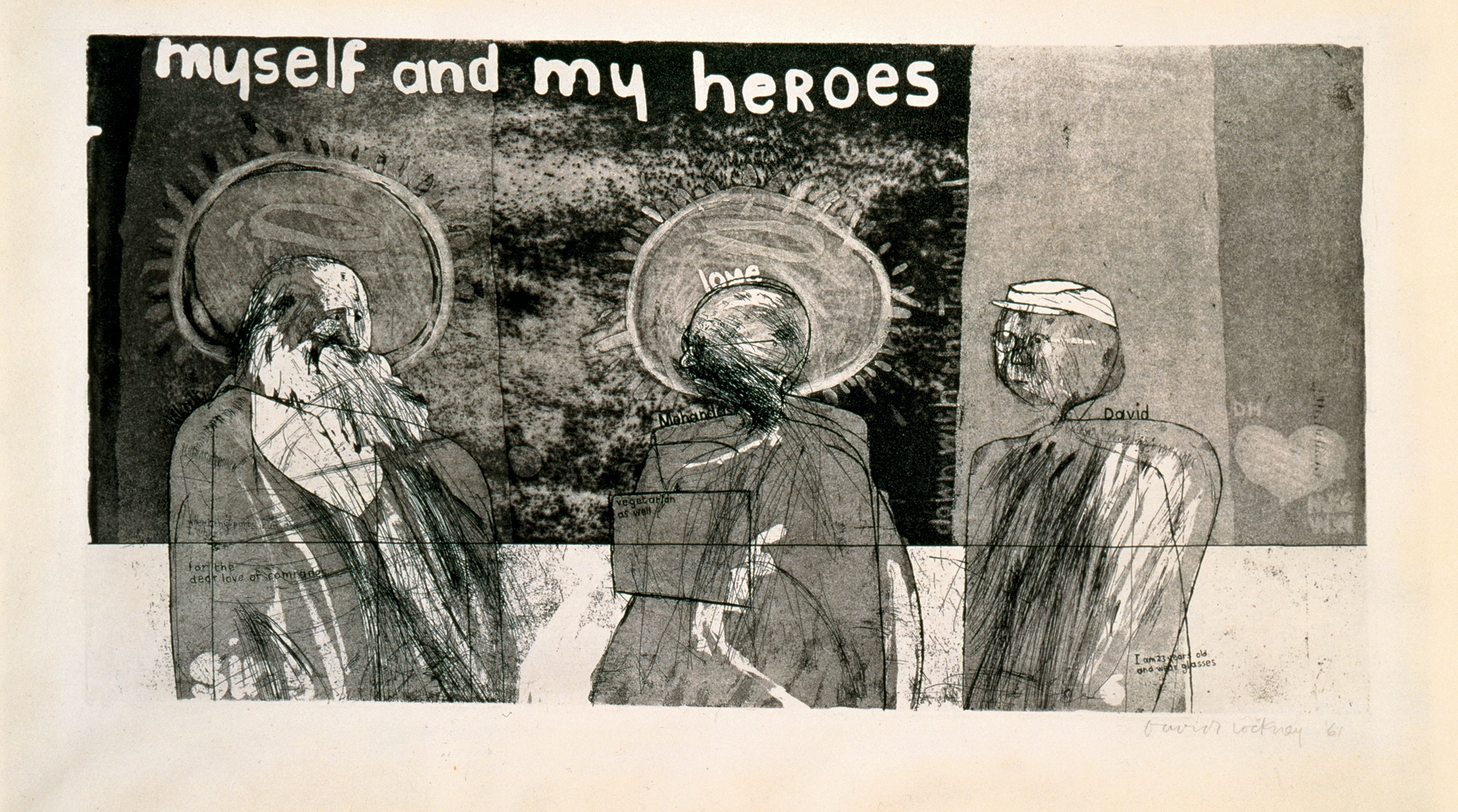

Whitman is a constant presence in Hockney’s early work, acknowledged as an admired figure in the 1961 etching Myself and My Heroes [24] and used as a direct source of imagery at least as late as the 1963 painting I Saw in Louisiana a Live-Oak Growing. The most lasting aspect of Whitman’s legacy is the effect it has had generally on Hockney’s imagery and subject-matter, for it is in these paintings of friendship between men that Hockney first established the two-figure compositions and the theme of personal relationships which have been such a dominant aspect of his art.

The title of We Two Boys Together Clinging [15], painted in the early months of 1961, is from another poem in Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Typically for Hockney’s work at this time, the subject-matter is at once determinedly public in its theme and cryptically private in its references. The closeness of the two men is made graphically evident by the zigzag markings physically uniting them as an indication of their spiritual bonds and sexual attraction. Two lines from Whitman’s poem are copied out on to the surface of the painting along the right edge as a sort of running commentary on the activities of the men: ‘Power enjoying, elbows stretching, fingers clutching,/Arm’d and fearless, eating, drinking, sleeping, loving.’ On the lips of the left-hand figure is the word ‘never’, extracted from the line ‘One the other never leaving’ as an indication of their passionate commitment to each other.

The private mythology of the painting is less immediately apparent. The prominent numerals ‘4.2’ in the lower left-hand corner refer once again to Doll Boy, Cliff Richard, as does the suggestion of a musical stave in the area above. Hockney’s attention had been attracted by a newspaper headline ‘TWO BOYS CLING TO CLIFF ALL NIGHT LONG’. Although it emerged that the article concerned a climbing accident and not the ultimate sexual fantasy, the humour of this coincidental reference nevertheless plays a part in the total meaning of the picture. So, too, does the alternative labelling of the figures with the numbers ‘4.8’ (Hockney) and ‘16.3’ (his boyfriend Peter Crutch, the subject of another painting of the same year), which transforms the general theme into a specific situation.

As a student at the Royal College Hockney produced a vast amount of work, often investigating the possibility of variations on a theme. So it is that the image of two men embracing appears also in a drawing of about the same time, with a title used for another of his paintings, The Most Beautiful Boy in the World [16]. This is one of a small group of drawings from 1961 in which Hockney tried watercolour for the first time, attempting to combat the apparent amorphousness of the medium by combining its veils of colour with a spiky linear underdrawing in ink in the manner of Paul Klee. The results did not satisfy him and he abandoned watercolour for the time being, returning to it in later years on several occasions only to dismiss it once again.

In view of the extremely personal nature of the subject-matter with which Hockney was dealing, the often comic aspect of his deliberately crude style at the time provided a useful balance. Humour can be a weapon, as Hockney realized in mocking the conventions of abstraction through the titles of his four Love Paintings of 1960–61, insisting through ironic contrast on the urgently human themes of his own work. By the time of The Fourth Love Painting [17], moreover, a softening had taken place of the blatantly propagandistic aims of the earlier pictures. It is not that Hockney had had a change of heart, but only that he had come to terms with his homosexuality and was able to take it for granted. Compared to the rather frantic repetition of the word ‘queer’ like some erotic mantra across the surface of Going to be a Queen for Tonight [18], painted in the previous year, Hockney’s paintings of 1961 are altogether more at ease in their acceptance of homosexual love.

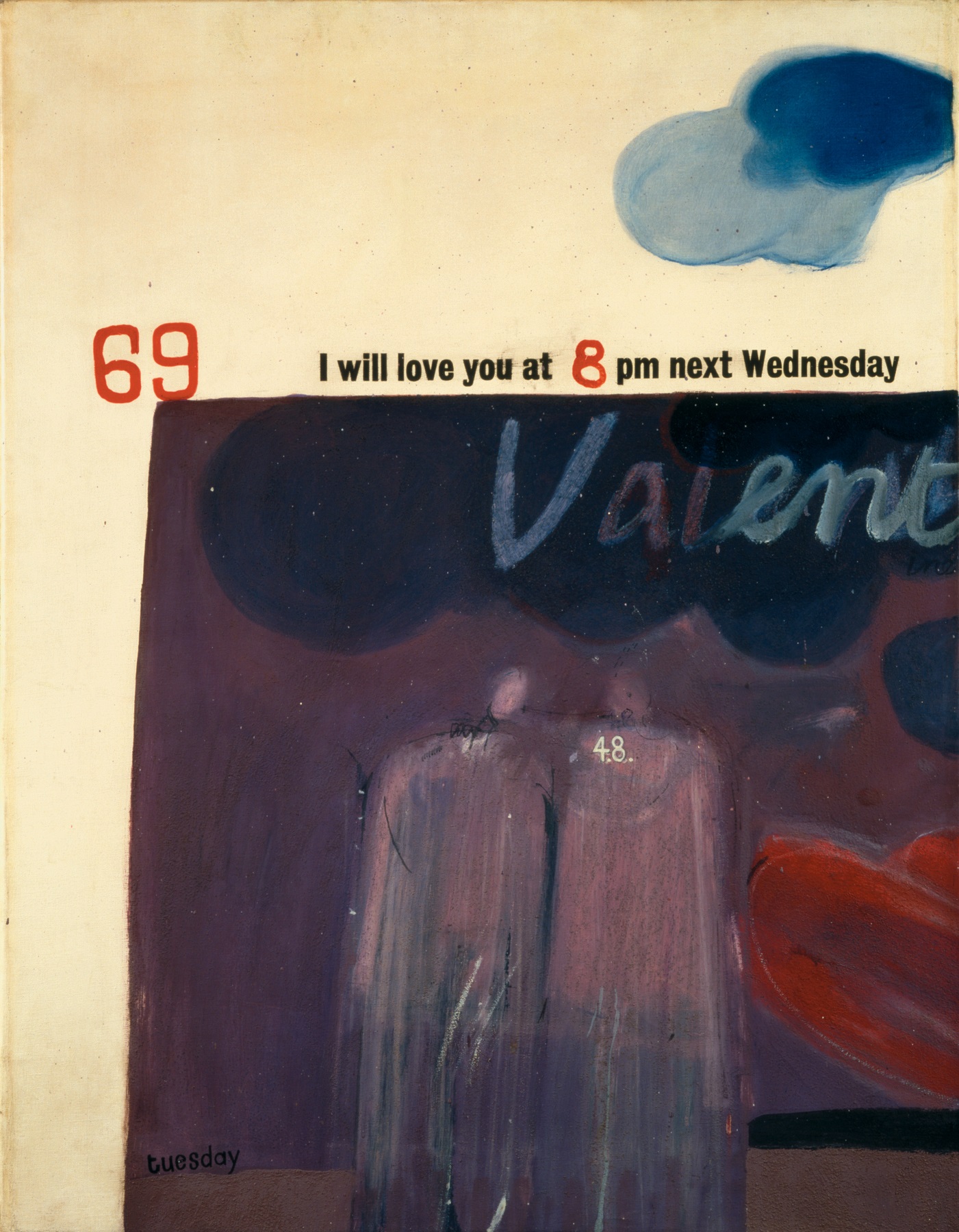

The Fourth Love Painting displays the relaxed and humorous attitude with which Hockney began now to treat themes of sex and love. Hockney took his cue for the line of type printed above the image (‘I will love you at 8 pm next Wednesday’) by paraphrasing W.H. Auden’s Homage to Clio: ‘“I will love You forever”, swears the poet. I find this easy to swear to. I will love You at 4.15 p.m. next Tuesday; is that still as easy?’ The title of the section from which this is quoted, ‘Dichtung und Wahrheit (An Unwritten Poem)’, is itself of significance, for Auden’s concern with ‘fact and fiction’ is echoed in Hockney’s picture. Love can take different forms, some more ‘real’ than others. It can be romantic affection, as signified by the embracing figures and the Valentine message. It can be a crush on someone one has never met; Valentine was the name of a magazine aimed at teenage girls which specialized in photographs of current pop stars. Love, finally, can be the sexual act itself, as revealed in the sly allusion of ‘69’ taking place at 8 p.m., which interprets the love of the message as a verb of action.

16 The Most Beautiful Boy in the World, 1961

17 The Fourth Love Painting, 1961

18 Going to be a Queen for Tonight, 1960

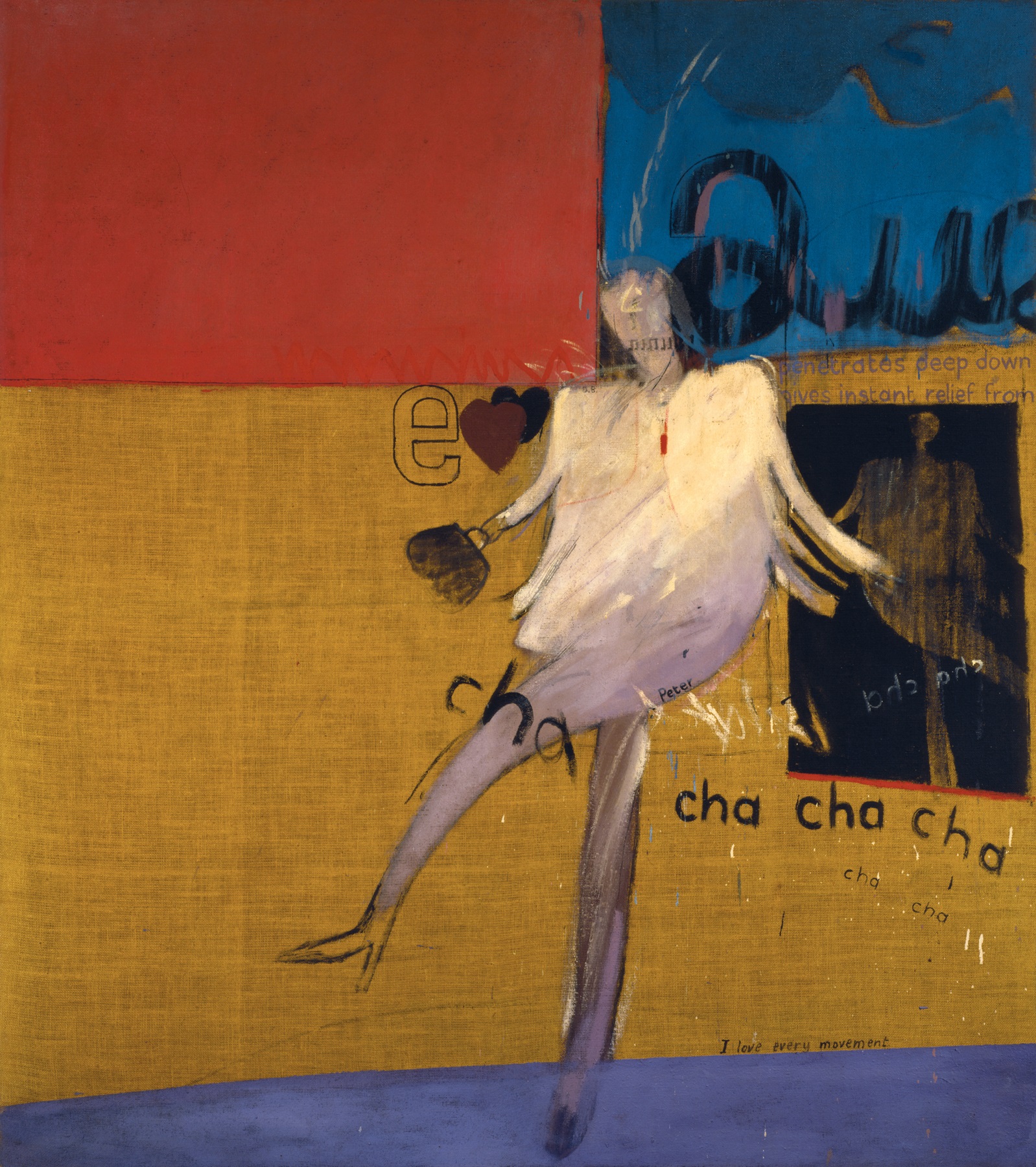

The transformation of sexual fantasy into reality is feted in another painting, The Cha-Cha that was Danced in the Early Hours of 24th March 1961 [19], through reference to an actual event: a fellow student whom he hardly knew, but who was aware that Hockney found him attractive, danced the cha-cha specially for his entertainment. A mirror in the background reflects the gyrating figure of the boy as well as the words ‘cha cha’, which themselves appear to be dancing across the surface. An etching that Hockney made in the same year, Mirror, Mirror on the Wall, includes a similar image along with a quotation from the last lines of the poem ‘The Mirror in the Hall’ by the Greek poet Constantine P. Cavafy (in John Mavrogordato’s translation): ‘The old mirror was … proud to have received upon itself/That entire beauty for a few minutes.’ Hockney thus suggests that the artist, like the mirror, is able to celebrate beauty not merely by witnessing it but also by reflecting it back to the viewer for his contemplation. A visual idea drawn from poetry thus again finds form as a poetic image in paint. Lest we are tempted into an overly serious appraisal of eroticism as a disinterested admiration of beauty, Hockney reminds us of the joy and physical pleasures of sex by copying on to the canvas an unintentional double entendre from the slogan on a box of medicated ointment: ‘penetrates deep down/gives instant relief from’.

19 The Cha-Cha that was Danced in the Early Hours of 24th March 1961, 1961

The smudged treatment of the dancing figure to suggest movement, along with the exposure of large areas of bare canvas, reveal Hockney’s interest at the time in the paintings of Francis Bacon [20]. Given Hockney’s return to an overtly figurative idiom, his admiration of Bacon’s work, which had impressed him in the one-man show held at London’s Marlborough Gallery in the spring of 1960, now found an outlet not only in openly homosexual themes but also in purely painterly concerns. Bacon consistently declared his opposition to pure abstraction, which he regarded as mere decoration lacking in content, yet his desire to make paint work directly on the nervous system instead of achieving its effects solely through the imitation of surface appearances constituted a significant application of the principles of recent abstract painting. Only a year earlier Hockney had been painting informal abstractions, and he was thus quick to seize the implications of that approach in a figurative context. From this moment he began to make frequent use of Bacon’s device of leaving bare large expanses of unprimed canvas, making evident that the image is formed in paint on a flat surface and thus destroying any illusion of depth. The painting is not to be a substitute for the world perceived through the senses but an equivalent to it, just as a poem creates a parallel to experience rather than its mere description.

20 Francis Bacon Figure in a Landscape, 1945

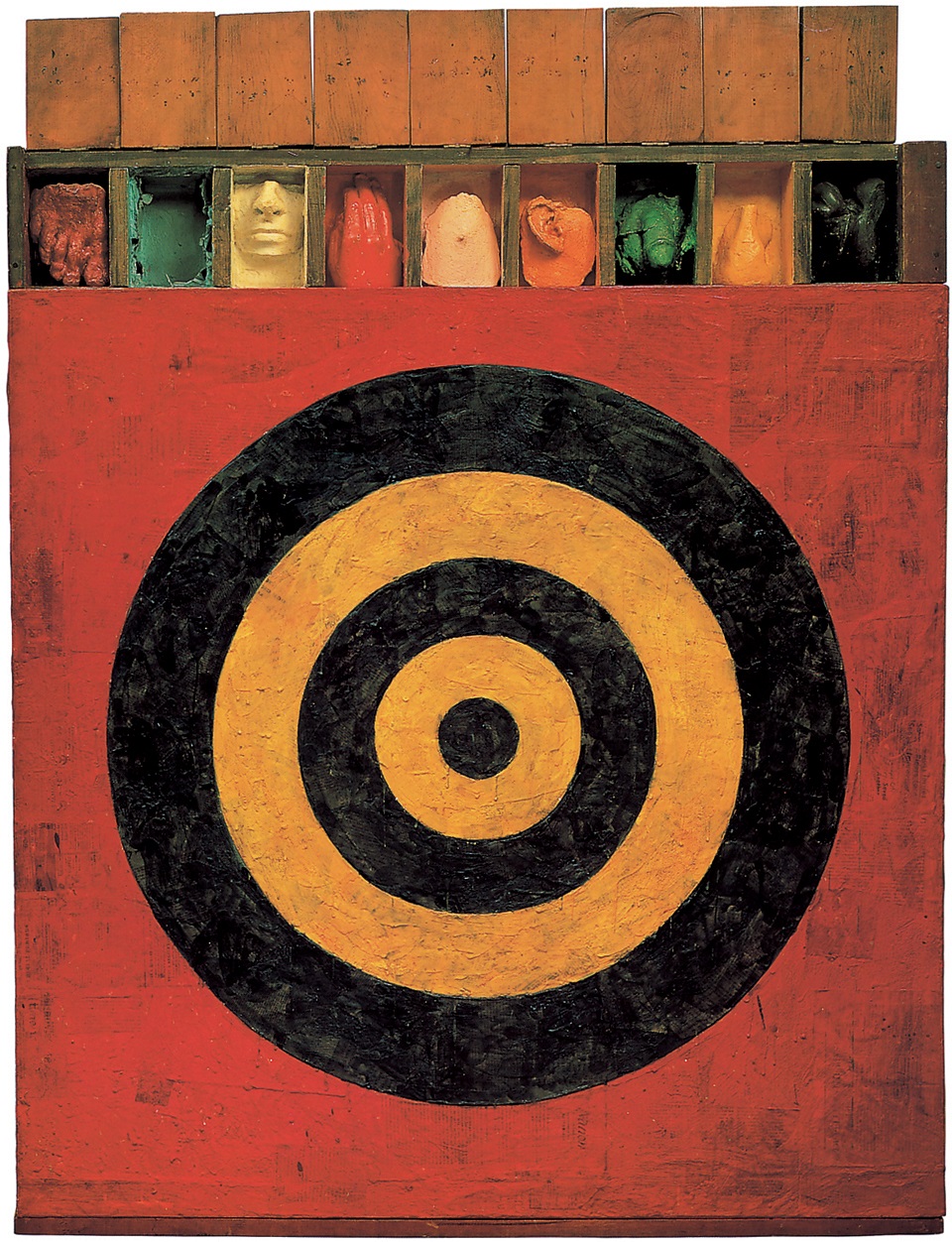

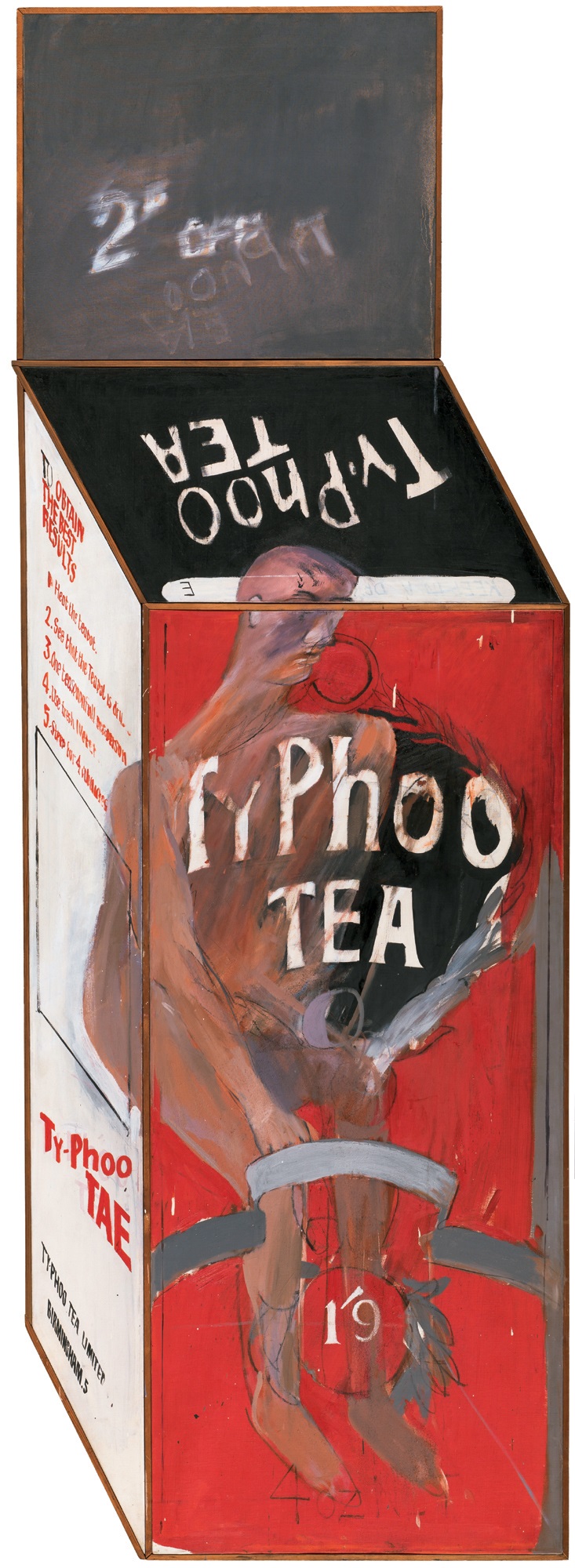

The influence of Bacon’s handling of paint is evident also in First Tea Painting [22], 1960, although here, for the first time in Hockney’s work, another solution is proposed for the concern with the material substance of the picture: that of equating the painting with a real object. A number of Hockney’s paintings of the early 1960s are based on commonplace objects which we know to be composed of flat printed surfaces. The Fourth Love Painting [17], for instance, mimics the format of a page in a calendar, carrying the reference so far as actually to print a caption on to the canvas surface. The notion of the painting as a real object was inherent already in Early Renaissance painting, for instance in shaped panels representing the Crucifixion, but it was enjoying a particular vogue about 1960 as a means of making figurative references while supporting the Modernist principle of the work of art as the thing-in-itself rather than as a pale reflection of reality. As early as 1955, for example in Target with Plaster Casts [21], the American Jasper Johns had influentially equated the canvas with the object it represented: an archery target, as in the case of this much reproduced work, or the American flag. Johns’s example had a counterpart, closer to home, in the work of British painters such as Richard Smith and Hockney’s fellow student Peter Phillips.

21 Jasper Johns Target with Plaster Casts, 1955

22 First Tea Painting, 1960

23 Kingy B, 1962

First Tea Painting [22], executed shortly after Adhesiveness [14] in the autumn of 1960, was one of Hockney’s first tentative steps back into a fully representational idiom, and as such attention is concentrated on the making of a legible sign rather than on the implications of the canvas as object. One senses a lingering Modernist prejudice about the act of depicting a three-dimensional object on a two-dimensional surface, a fear that the result will be a mere illustration. Hockney thus depicts only one side of the tea packet, reassembling a flat printed surface on to a flat painted surface, and taking care to leave ample evidence of the trail of the brush across the canvas. The rectangle of the tea packet, however, floats well within the boundaries of the canvas, creating a surface design which is essentially of the same nature as that of his abstract pictures from the beginning of the year.

The liberating influence of Picasso, the revelation that inspiration could be found anywhere, was by this time beginning to have an effect on Hockney, and the Tea Painting was soon followed by a series of pictures based on playing-cards. Intrigued by the reproductions in a book on the history of playing-cards which Mark Berger owned, Hockney began at first by making drawings from these illustrations. The image soon found its way on to canvas in paintings such as Kingy B [23]. Here was an ideal subject for the canvas as object equation, a printed artefact which itself was flat and which could be reconstituted in paint to the desired dimensions. The outline of the enlarged playing-card matches the boundaries of the canvas, freeing the artist to paint figures and even, if he so desires, to create sensations of space, in the full confidence that he is portraying these as pictorial conventions.

In contrast to the personal commitment characteristic of the imagery he was beginning to use in other works, there might appear to be something superficial and flippant about paintings of tea packets and playing-cards. To make this claim, however, would be to lose sight of the crucial fact that in the early 1960s Hockney was prepared to use anything in his work, and that it is this that gives his art at that time its sense of generosity and wide-eyed awe at what the world has to offer. It was in the same spirit that Hockney, having run out of painting materials and without the money to purchase more, decided early in 1961 to avail himself of the free plates offered by the graphic department in order to make his first etchings. At Bradford he had taken lithography as a subsidiary subject but he had never tried etching, and had it not been for circumstances beyond his control it might not have occurred to him to turn his attention to printmaking now. It was simply a question of making the best of the situation.

Myself and My Heroes [24] was conceived merely as a test plate, his first essay in etching, but it reveals a natural delight in the medium. In spite of its small size, it contains a number of the elements which he was to pursue in his subsequent prints – a combination of straightforward etched line, tiny scrawled messages, and several layers of aquatint for a full tonal range – as if, in his impatience, he wanted to investigate at once the full potential of the medium. Hockney says that he is ‘well aware that sometimes a medium turns me on’, adding that ‘often a medium can force you to work in a different way’.

The three figures in this first print by Hockney are set against three clearly differentiated panels, identifying the image as a rather wayward reflection of a traditional religious altarpiece. Hockney presents himself as a kind of donor figure standing in respectful admiration of two personal saints, each enshrined in a double nimbus: Walt Whitman and Mahatma Gandhi. Each man carries an identifying caption, Whitman speaking ‘for the dear love of comrades’, Gandhi promoting love and ‘vegetarian as well’, and Hockney himself, humbled by the achievements of his heroes, saying only ‘I am 23 years old and wear glasses.’ It is, however, an affectionate memento rather than a distant act of homage: the artist has drawn a heart and scratched his initials opposite those of his mentors.

Were it not for the spontaneity with which Hockney formulated his images at this time, one could almost say that there was a programmatic intention in these works of revealing his situation as a human being. Kitaj, with whom he had struck up a close friendship, was encouraging him to make pictures on themes about which he cared passionately, and it seems to have been Kitaj who disclosed to Hockney ways in which literature could be used as a legitimate source of imagery.

24 Myself and My Heroes, 1961

Kitaj often demonstrated a personal commitment to the content of his own pictures by taking literary and historical sources as his raw material; his proclamation in 1964 that ‘Some books have pictures and some pictures have books’ reflected a long-standing concern. Perhaps it was necessary that it be an American in self-imposed exile from his country, a man immersed in the writings of T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Henry James and others, who saw in literature such potential for picture-making. In England, where there has been a long tradition of the literary in the visual arts, ‘literary’ characteristics have taken on a pejorative connotation. Reminded of the excesses of sentiment and theatricality of Victorian set-pieces, we are too easily led to the conclusion that inspiration from books constitutes a failure of nerve or a disappointing compromise, an inability to construct a picture through purely visual means.

Hockney appears to have found it difficult to indulge his taste for storytelling in paintings, perhaps because he was still conditioned by the Modernist prejudice against such an activity, but in his prints he was able at once to depict a sequence of events rather than limiting himself to the presentation of a static situation as in the paintings. This is manifest already in some of his first etchings, such as the multi-frame Gretchen and the Snurl, 1961, based on a fairy tale written by Mark Berger and which ends in an image of embracing figures similar to that of We Two Boys Together Clinging [15]. There are also two etchings of Rumpelstiltskin, dating from 1961 and 1962, which are the first evidence of Hockney’s interest in the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, which he was to illustrate at the end of the decade in an elaborate book of etchings.

Hockney seems to have felt that there was a logic to telling a story in a print because of the similarity between the etched line and the printed word: ‘All the early etchings deal with line, and somehow the line telling the story seemed appealing, whereas in the paintings you get involved with other things, the paint, the texture, and narrative is harder to deal with. I could do it now, but at the time it was easier to work out in etching.’

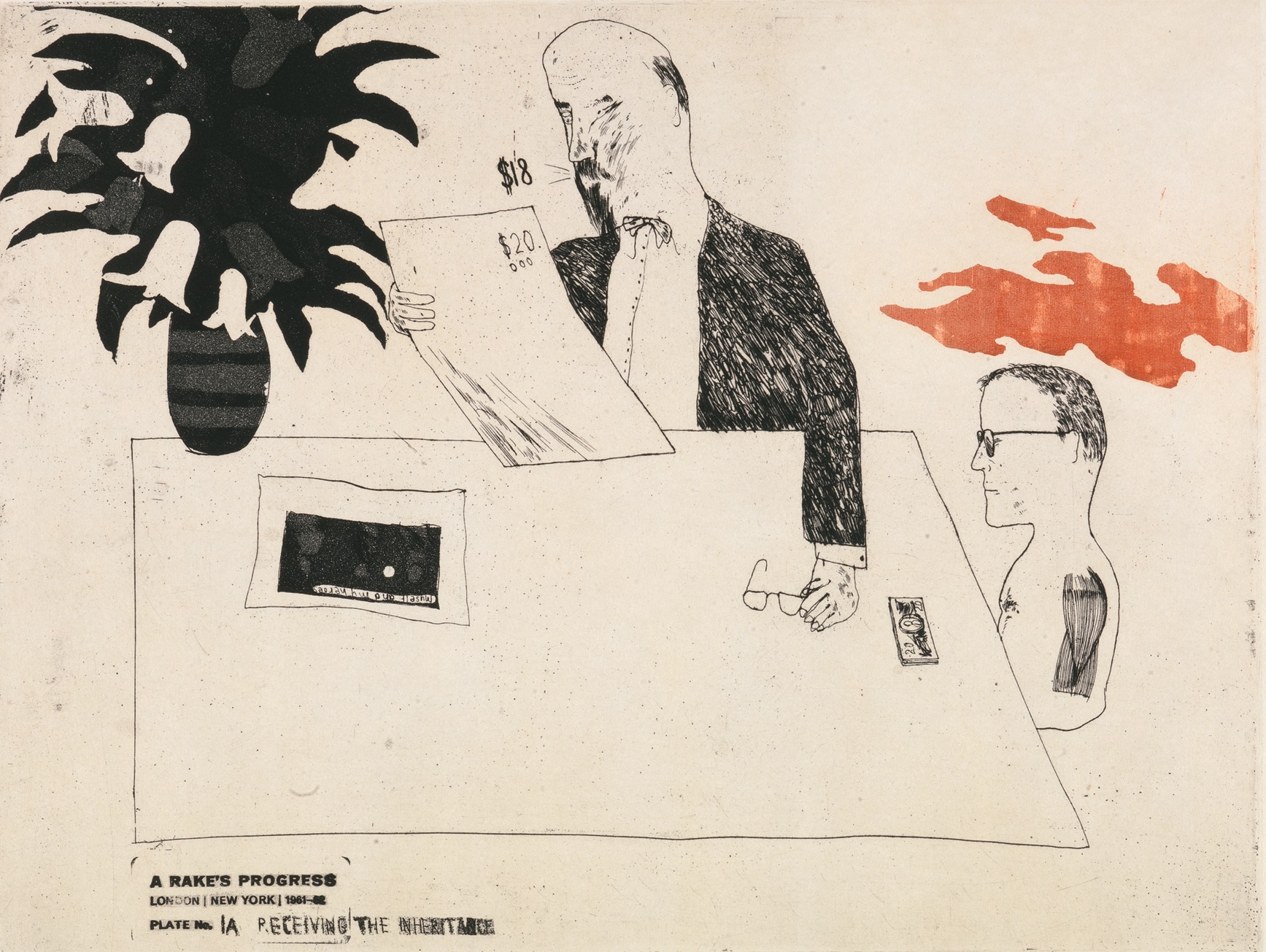

Hockney was aware, moreover, that there was a tradition for using prints to tell a moral, as testified by the work of William Hogarth. The importance of Hogarth’s example is openly acknowledged in Hockney’s first major series of prints, A Rake’s Progress, 1961–63 [1, 25], in which the strong narrative content was initially adapted directly from Hogarth’s series of the same name [26], transformed through reference to Hockney’s own time and experience. The idea for the series as well as much of its imagery arose from his first visit to New York City in the summer of 1961, a trip which was made possible with the first prize-money awarded to him at the ‘Graven Image’ exhibition held at the R.B.A. Galleries early in that year. Hockney’s original intention, when he formulated plans for the set on his return to London in the autumn of 1961, was to make eight plates, the same number as in Hogarth’s series and titled as in the eighteenth-century version. The Principal of the Royal College, Robin Darwin, encouraged him to increase the number so that it could be published also as a book by the College’s Lion and Unicorn Press. The number of plates was raised to twenty-four but eventually a compromise of sixteen was reached.

25 Receiving the Inheritance from A Rake’s Progress, 1961–63

Characteristically for Hockney’s subsequent development, his first major work was thus created in a graphic medium, a medium often regarded by painters as of subsidiary importance to their main body of work. Such categories seem not to have worried Hockney, who was more concerned to find a medium suitable to the subject, but what did concern him was the enormous amount of work that would be called for without the help of an assistant. The sixteen plates were not finished until the summer of 1963, all of them having been made in London apart from Plates 7 and 7A, which were etched in 1963 on a return visit to New York. It was only on completion that Paul Cornwall-Jones of Editions Alecto approached him with a view to publishing the set commercially. The plates, however, were planned essentially in 1961. A few preparatory drawings were made as a means of planning out the sequence, but generally, since etching is itself a form of drawing, they were drawn directly on to the plates.

26 William Hogarth The Rake’s Progress, Plate 1, 1735

A Rake’s Progress provides a visual account of the relationship between his life and personal interests and the work to which they give rise. The imagery is culled primarily from his visits to New York City, and the artist records private events such as visits to gay bars and the dyeing of his hair. Like Hogarth’s series, it is a cautionary tale, a warning to himself as well as to others of the loss of identity which occurs when one bows to external pressures. The destruction of innocence and individuality, we are reminded, is not simply a matter of personal morality. Also at issue is the corruption and debasement of art. In Plate 1A, under the title Receiving the Inheritance [25], we witness the reduction of art to the status of a mere commodity, as the artist haggles with a collector over the price of his own etching Myself and My Heroes [24]. The fact that this particular print is a statement of his own ethical stance makes the transaction all the more sordid and debasing. Elsewhere Hockney hints at the dilution of art in its transformation into the clichés of advertising, as in The Start of the Spending Spree and the Door Opening for a Blonde [1], where the artist admits to his seduction by the promises of eternal sunshine and carefree existence. Hockney is well aware of his own weaknesses: the swaying palm trees presented here as the product of his fantasy were later often to be depicted by him from direct observation.

27 A Grand Procession of Dignitaries in the Semi-Egyptian Style, 1961

There is a deliberate fragmentation of imagery and technique in these prints which makes sense only when interpreted thematically. References to advertisements jostle with film, with traditional religious iconography (as seen through a photograph by Cecil Beaton), and with images of monumental sculpture and twentieth-century architecture. The imagery printed in black from etching and aquatint is paired with textured surfaces printed in red from areas etched on to the plate using the sugar-lift technique. The dissolution of the rake is presented graphically in a number of the prints through his depiction as a limbless bust. In the last print of the series the rake is indistinguishable from the other robotic figures, all of them drawn in the same way and lined up like paper dolls with no facial features to indicate personality. Sealed off from human contact by the earphones of their transistor radios, this is Bedlam in modern guise.

Jarring juxtapositions of image and technique, as well as contrasts of spatial suggestions against the flatness of the support, are essential ingredients not only of the prints but also of the paintings executed by Hockney on his return from New York. This is particularly evident in the painting he began at the start of the autumn term, A Grand Procession of Dignitaries in the Semi-Egyptian Style [27], his largest canvas to date. Inspired by the poem ‘Waiting for the Barbarians’ by C. P. Cavafy, a resident of Alexandria, Hockney chose to paint his picture in the style of Egyptian tomb paintings, an idiom as rigid as that of children’s art but endowed with associations appropriate to the subject. The ironic tone of the poem appealed to Hockney as a wry comment on human nature: our tendency to inflate our self-image by contrasting ourselves with those we deem inferior, and the ease with which we can invent false motives for our actions and then delude ourselves into believing them. The clergyman, soldier and industrialist in Hockney’s picture all hide within the trappings of their public persona, inside which they are really very small. The hieratic stiffness of the modified Egyptian style suits well the pomposity with which they carry themselves, the formality of their postures betraying the fact that they are putting on an act. Hockney recalls that he set out to make a highly theatrical picture, including even the tassels of a curtain along the upper edge, as a means of emphasizing the human situation with which he was dealing. This theatricality, and the curtain motif in particular, immediately acquired a fascination in itself and ever since has been a recurring feature of his work.

A Grand Procession was one of the four Demonstrations of Versatility which Hockney exhibited at the ‘Young Contemporaries’ student show in February 1962. The others were Tea Painting in an Illusionistic Style [29], Swiss Landscape in a Scenic Style and Figure in a Flat Style [28]; the titles of these have since been amended. The playfully confident attitude towards style as an element that can be chosen at will is revealed even in the selection of titles. In a conversation with the American painter Larry Rivers published in Art and Literature 5 (summer 1965), Hockney later recalled: ‘I deliberately set out to prove I could do four entirely different sorts of picture like Picasso. They all had a sub-title and each was in a different style, Egyptian, illusionistic, flat – but looking at them later I realized the attitude is basically the same and you come to see yourself there a bit.’

With an imaginative group of pictures already behind him, Hockney now felt sufficiently assured to take up the challenge of the Picasso exhibition he had seen in 1960. Not only does he take up a succession of styles in different pictures, but within a single painting he moves freely from one mode to another, from flatness to illusionism, from bare canvas or areas of unmodulated colour to gestural surfaces, from depictions of figures to written messages to painted marks that are so self-sufficient that in any other context they would be assumed to be abstract.

28 Figure in a Flat Style, 1961

A self-conscious deployment of apparently contradictory styles is something that Hockney, along with other young painters with whom he was studying, had remarked also in the work of Kitaj. It is in this respect that one can detect a unity of purpose among a group of painters at the Royal College for a short period in the early 1960s. Each was seeking refuge from the Abstract Expressionist concept of the canvas as an arena of self-expression, the notion of painting as existential autobiography formulated by the critic Harold Rosenberg to describe the aims of the generation of American artists then considered the epitome of the avant-garde. While not denigrating the achievements of painters such as Jackson Pollock or Willem de Kooning, Hockney and his colleagues were wary of such concepts of self-projection, which they believed could make the artist a slave rather than the master of his own means. Just as an image was selected rather than simply discovered in a haphazard manner, so a particular style could be quoted rather than adopted unthinkingly. In so doing the artist declared the preeminence of choice and control in the making of his picture.

Figure in a Flat Style [28] relates to Hockney’s homo-erotic pictures from earlier in the year, but here he investigates the limits to which abstraction can be carried without sacrificing the legibility of the image as a figure. He achieves this through the form of the canvas itself, or more precisely through the relation of the three parts which make up the complete picture. A small square canvas functions as the head, a vertical rectangle as the torso, and the wooden supports of an easel are used as a sign for the legs. Thus even before the addition of the painted marks the shape of the picture as a whole identifies the subject. The head, represented within the square canvas as a grey circle within a white linear arch, is as severely schematized as the ungainly wooden legs. The arms and hands, by contrast, are clearly drawn in white across the central surface, bringing our attention to the urgency of the masturbatory gestures of the hands.

The sexual connotations of the image are alluded to in the alternative title of the picture, The fires of furious desire, written across the top of the main canvas. The awkward physique of the figure takes on strongly personal connotations when examined in the context of such lonely sexuality. The phrase is taken from a poem by William Blake, but the figure, built from the basic materials of the painter – canvas and easel – can be none other than Hockney’s self-portrait. The very anonymity of the geometrical style provides, through contrast, a poignancy to this extremely personal image of vulnerability.

Hockney followed up the implications of Figure in a Flat Style in another of the Demonstrations of Versatility, Tea Painting in an lllusionistic Style [29], in which he explored further the means by which the shape of the canvas alone could identify the subject of the picture or change our reading of the painted marks within. A preliminary drawing established the image of a figure trapped inside a box represented in isometric projection; when he came to make the painting, he decided to have the box-top open in order to make the image more immediately recognizable as the rendering of a box. The equation of the canvas with a real object, an idea which he had used a year before in his playing-card and early tea paintings [23, 22], here gives rise to the first work by any of the Royal College artists in which the shape of the stretcher departs from the traditional rectangle, so that even before any paint is applied the canvas is identified as a specific object. The containing shape alone establishes the subject, in this case a box in perspective, while maintaining the painting’s literal reality as an object: canvas stretched flat over a wooden framework. Since the illusion is ‘drawn’ in the shape of the canvas itself, the painter is left to make whatever kind of mark he wishes across the canvas surface. The figure, no matter how flatly it is painted, still resides convincingly within the illusion of an enclosed space. Other artists, notably Allen Jones in his Bus paintings of 1962, seized on the idea of the shaped canvas, but Hockney himself did not pursue it for long. The Second Marriage, 1963 [33], is the last picture of his to feature a shaped canvas, and this was stretched up long before it was painted. Hockney was interested more in other things, and felt the shaped canvas alone was too formal a device.

29 Tea Painting in an Illusionistic Style, 1961

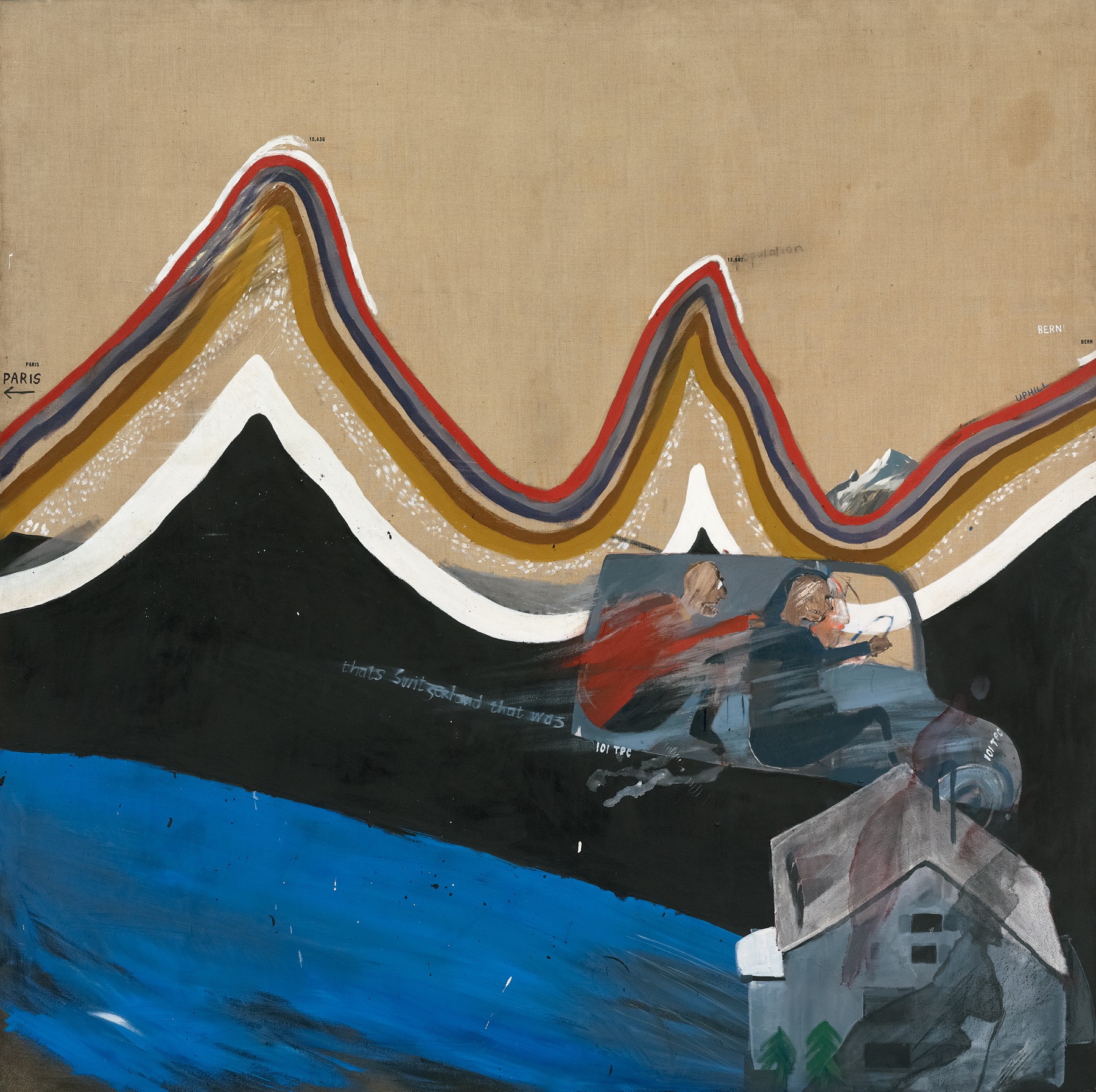

The last of the Demonstrations of Versatility, Swiss Landscape in a Scenic Style, followed soon after by a closely related larger canvas, Flight into Italy – Swiss Landscape [30], introduced another favourite habit, that of making reference to the work of other artists as a means of defining the characteristics of his own pictures and of making evident their relationship to other contemporary art. The bands of vivid colour in the latter picture, for instance, refer in the first place to the schematized depiction of mountains in geological maps, a wry comment on the fact that he failed to see the Swiss Alps from the back of the van in which he was driven to Italy (the momentary glimpse of a mountain peak rendered illusionistically was, in fact, culled from a colour postcard). The bands of colour, however, are also references to the abstract paintings by Harold Cohen, in which meandering lines direct the viewer’s eye across the surface of the canvas. The subject of Hockney’s picture, his rushed journey across Europe, is thus supported through this allusion to a pictorial device for movement.

30 Flight into Italy – Swiss Landscape, 1962

In other paintings of this time Hockney borrows the technique of staining colour into the weave of the canvas – a method used by the American abstract painter Morris Louis as a means of evolving images directly through the process itself – only to negate the self-sufficiency of that image as a material fact by providing it with a representational meaning. The rivulets of colour on the surface of bare canvas in Picture Emphasizing Stillness [31] paradoxically become the groundline supporting two figures, while the concentric rings in The First Marriage [32], a reference to the paintings of Kenneth Noland, are transformed into a sign for a tropical sun. The preoccupations of current abstract art are gently mocked, as in the ‘animation’ of the popular target motif into Snake in the 6 × 6 ft canvas of 1962. What Hockney is doing, in effect, is to assert the traditional concerns of figurative art, by which each mark functions both as an element within an enclosed formal system and as part of a recognizable image of something seen. The viewer’s experience centres on the interaction of these two functions of paint-as-paint and paint as a sign for a reality outside the picture.

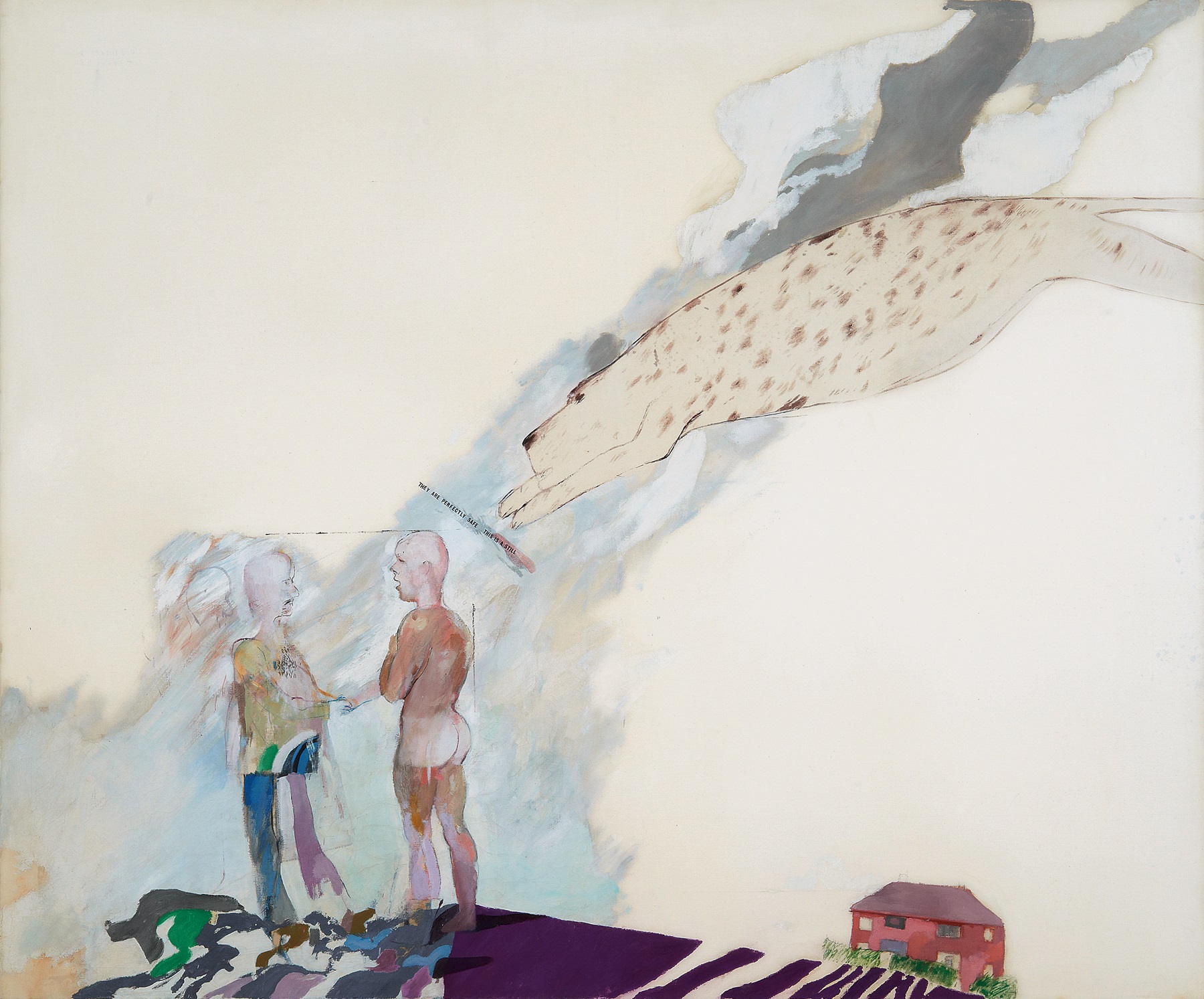

31 Picture Emphasizing Stillness, 1962

The ideas for Picture Emphasizing Stillness and The First Marriage both took form in drawings made by Hockney during his visit to Berlin with an American friend in August 1962. The former was suggested by a picture of a leopard which he saw in an East Berlin museum, and which made such an impression on him that he drew it as well as he could from memory on his return that evening to his hotel room. Using only this spontaneous ink sketch as a guide, he re-elaborated the image on canvas upon his return to London. The two men in the painting appear to be in imminent danger of attack by the animal leaping through the air. It is only when we approach the canvas that we realize how foolish we have been to be taken in by this imaginary situation, for underneath the leopard is the self-evident message: ‘They are perfectly safe. This is a still.’ The messages written on Hockney’s pictures, like the titles themselves, thus begin to have a different function, that of drawing our attention to the visual characteristics of the pictures rather than simply to their themes or literary sources. The message here is a serious one, that of relating the innate impossibility of presenting actual movement in the form of a static image, but Hockney manages to get it across by matching his detached attitude to style with a dead-pan literal-minded sense of humour.

The title of The First Marriage (A Marriage of Styles I) [32] also provides the key to its interpretation. The bridegroom and his wife are a most unlikely couple: the man, dressed in a conventional suit and tie, seems to be from our own society, but the stiffly formal woman with her exaggeratedly geometric breasts is not only not from our culture but not of flesh and blood either. The scene was, in fact, suggested by the sight of Hockney’s American friend standing in profile next to a stylized Egyptian figurine at the end of a corridor in an East Berlin museum. The bride retains the unyielding hardness of the wooden model, but the man, too, although based on studies from life, has a rather caricatural air. The setting has been left deliberately vague, not only because Hockney had not made notes about this at the time of the original encounter, but also because the large area of bare canvas exposes the image undeniably as a fabrication in paint. Using only four elements – a groundline, a wedge form like the Gothic arch of a church, a palm tree and a schematized sun – Hockney establishes that a marriage is taking place in an exotic location without distracting us from the essential relationship of the two people.

32 The First Marriage (A Marriage of Styles I), 1962

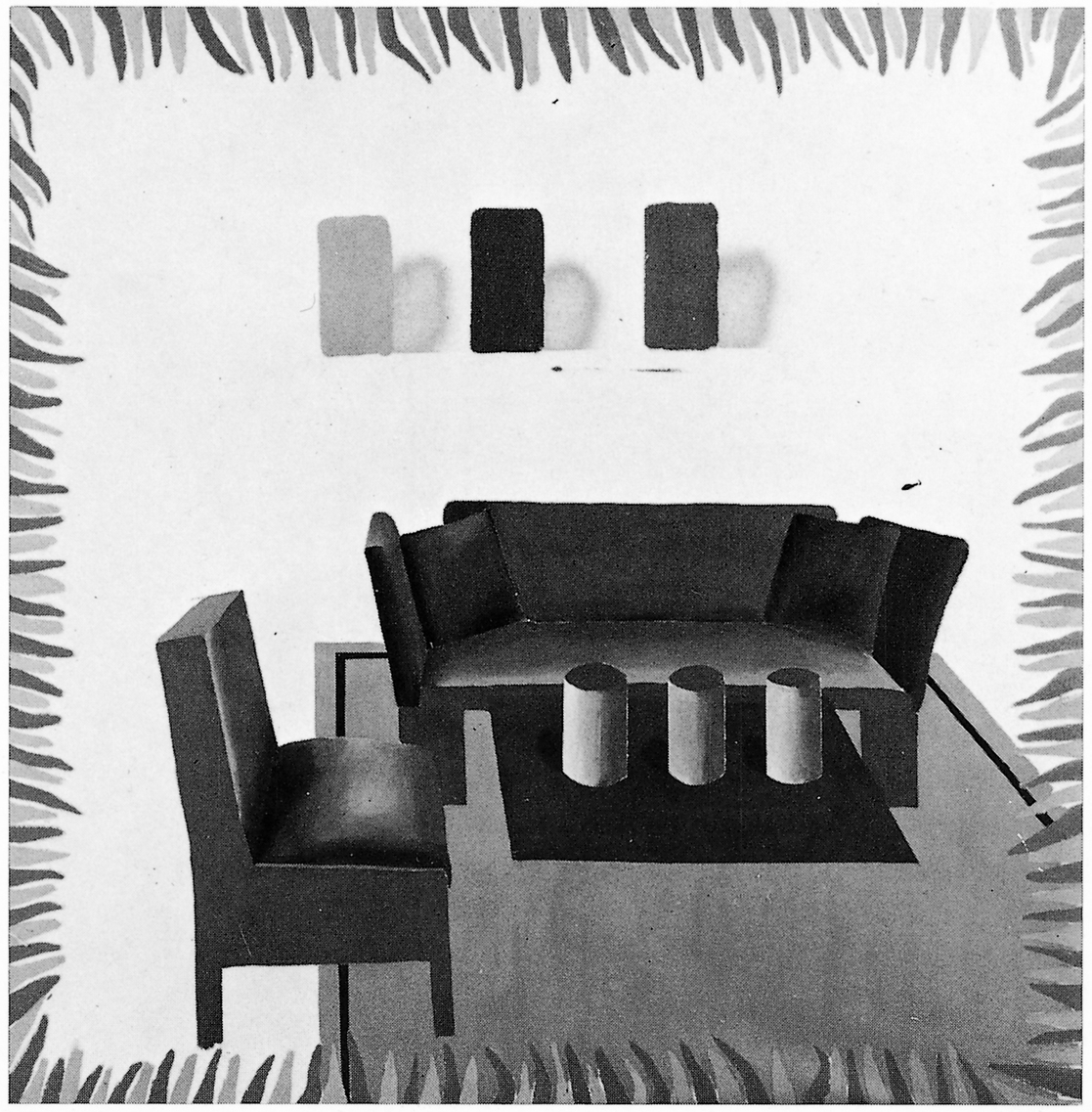

In spite of the high degree of stylization and the delight in contrasting idioms, The First Marriage is the first two-figure composition in which at least one figure can be said to have a specific identity. This quickly suggested the possibility of applying an even greater degree of particularity to the theme of intimate relationships which he had treated earlier in pictures such as We Two Boys Together Clinging [15]. Early in 1963, Hockney painted The Second Marriage [33], placing the two figures within a defined domestic setting. Since the shape of the canvas itself identifies the box-like space of a room interior, very few elements are needed to convince us that this is a home: a sofa, a wallpapered wall, a small table with wine bottle and glasses (each marked with a numeral for the appropriate figure), and a patterned floor which is as much an ancient mosaic for the Amarna princess copied from a book as it is a modern carpet for the gentleman at her side.

33 The Second Marriage, 1963

34 Domestic Scene, Broadchalke, Wilts, 1963

The Second Marriage could be described as a holding operation, a restatement of earlier themes and devices while the artist considered what to do next. Hockney had given some thought, in fact, to painting a rather different picture on this shaped canvas, which he had stretched up more than a year earlier. Prompted by memories of Duccio’s shaped crucifixion in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, which he had seen in 1961, Hockney’s original intention was to paint a crucifixion in a box: ‘But then I couldn’t deal with a crucifixion at all. It’s not that you have to be a believer, but I suddenly realized it was a genuinely “big” theme. It’s about pain and suffering, which is something I chose to avoid, as I’m sure I avoided it a lot later, but I assume it will actually become a theme as you go on through life.’

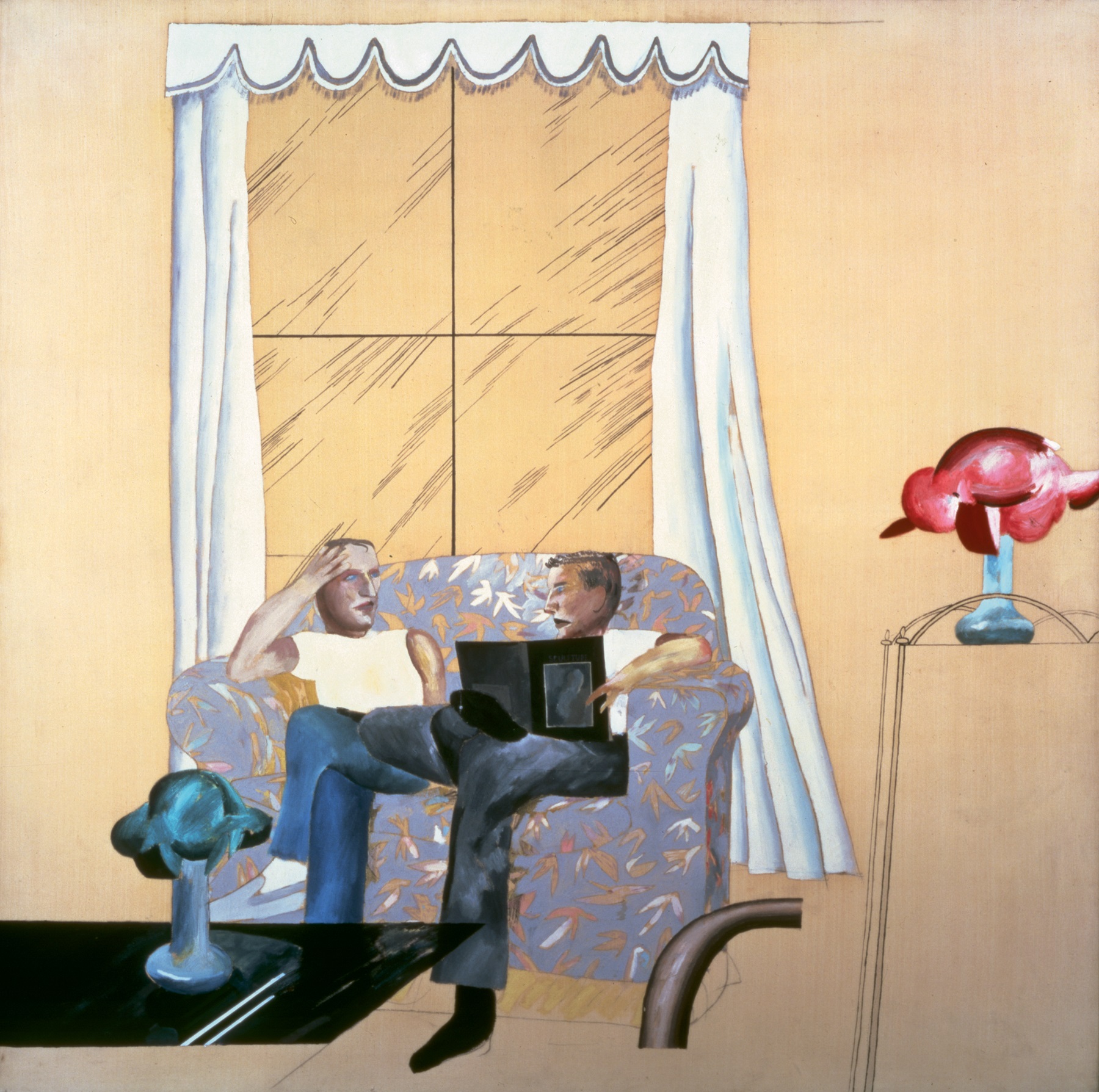

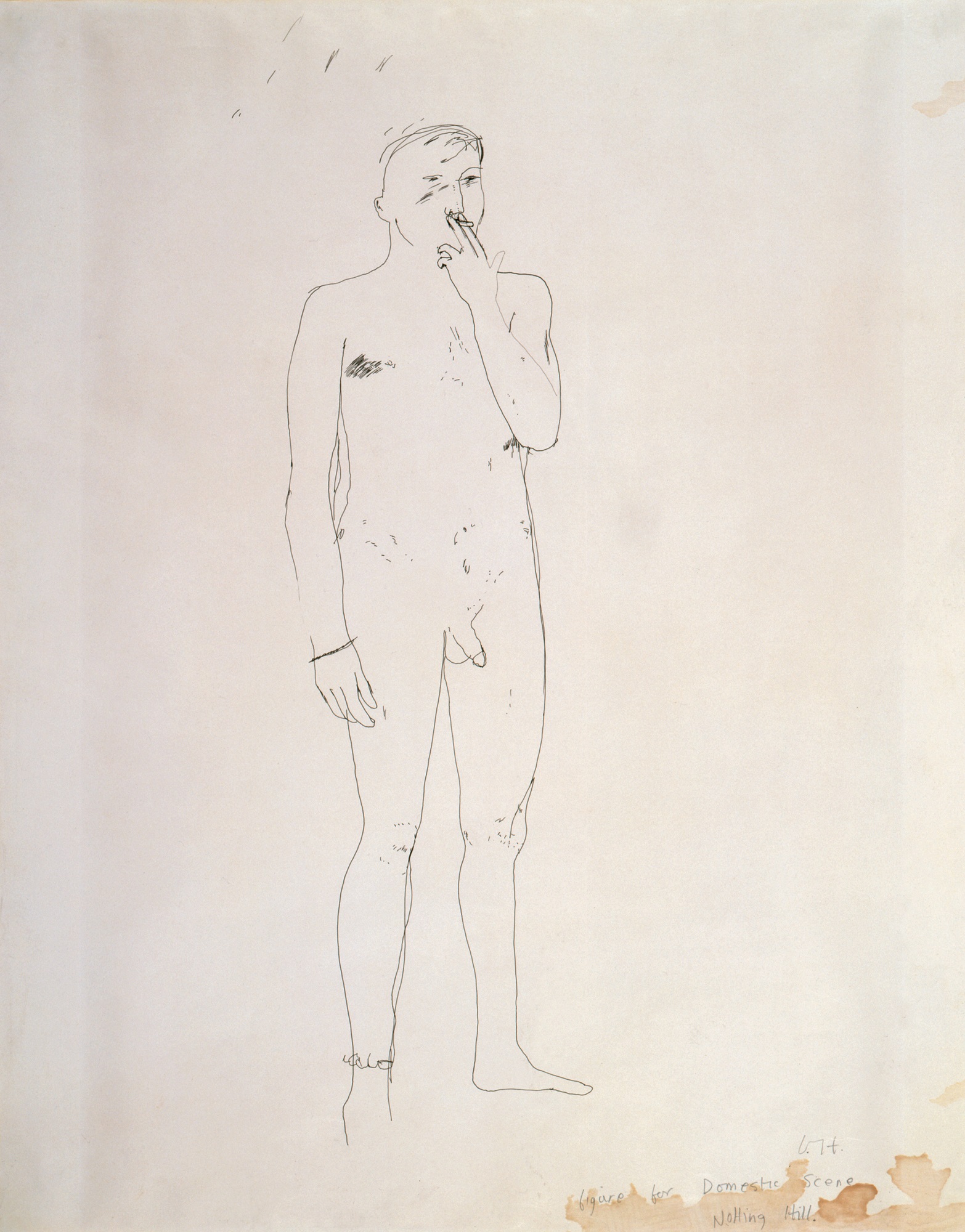

35 Standing Figure (Study for Domestic Scene, Notting Hill), 1963

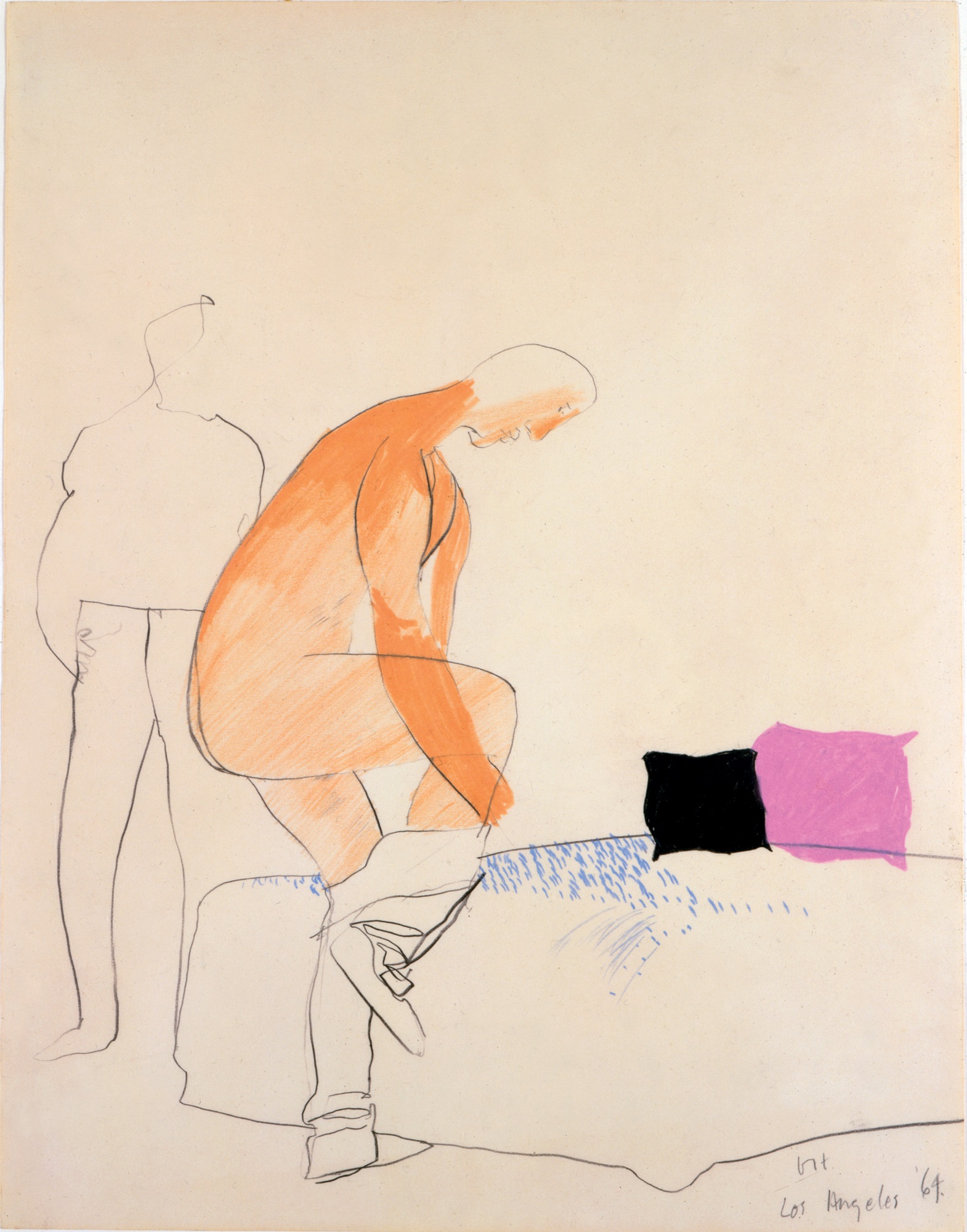

Recoiling from the idea of a grand theme, Hockney decided instead to make a series of intimate pictures of people in their homes. The three Domestic Scenes [34, 36, 37] which resulted are based both on observation and on imagination. The artist had recently moved into a flat in Powis Terrace in the Notting Hill district of London, and it is the objects in this interior which are recorded in Domestic Scene, Notting Hill [36]. The two figures, like the objects, were painted from life, and although Hockney was not concerned with likeness, it was essential to the sense of relaxed social contact that both men were close friends of his and of each other. The seated figure is Ossie Clark, who had been a fashion student at the Royal College at the same time that Hockney was there, and the man standing in the nude is Mo McDermott, Hockney’s model and assistant. The painting was preceded by two studies of Mo, one a sketchy rendering in crayon to test the colour and surface, the other a more detailed study from life which is one of Hockney’s earliest line drawings in ink [35]. The technique was suggested by the need to draw quickly from life, finding the essential contour, by his experience with a wiry descriptive line in etching, and by the work of other artists, including George Grosz, in which he had been interested for several years. (During his last year at the Royal College, Hockney had written an essay on Fauvism in which he called Matisse one of the ‘master draughtsmen’ of the twentieth century, praising his ‘extremes of economy’, but for many years he found Matisse’s style of drawing too free for his own purposes.)

36 Domestic Scene, Notting Hill, 1963

Hockney’s use of a study in line for the figure of Mo reveals a change in his painting habits at this time. Rather than forming the images directly in paint on canvas, as he had done from 1960 to 1962, he would now draw in the outline first and then fill in this enclosed surface. This in turn directed a shift in the role and, therefore, the character of some of his drawings, which became tighter and more linear in these circumstances for ease of transfer. The figures in Domestic Scene, Broadchalke, Wilts [34] were painted entirely from drawings, but those of Domestic Scene, Notting Hill [36] were done directly from life on to the canvas, using drawings only as a guide. Wishing to avoid the laborious appearance of an art school life painting, Hockney brushed the figures in quickly, worrying not about fidelity to natural appearance but only about the vitality of the painted marks.

37 Domestic Scene, Los Angeles, 1963

There are no walls and no floor in Hockney’s Notting Hill interior, which is recreated solely through a few eye-catching objects: a chair, a curtain, a lamp and a pot of plastic flowers. Hockney had observed, as he reiterated in 1979 in conversation with Charles Ingham, that ‘Vision is like hearing, it is selective, you decide what’s important, which means that other factors are determining what you see as well. Mind you that’s why painting is interesting, why in one way it’s far more interesting than the photograph, because the selection is even better and more related to personal feelings.’

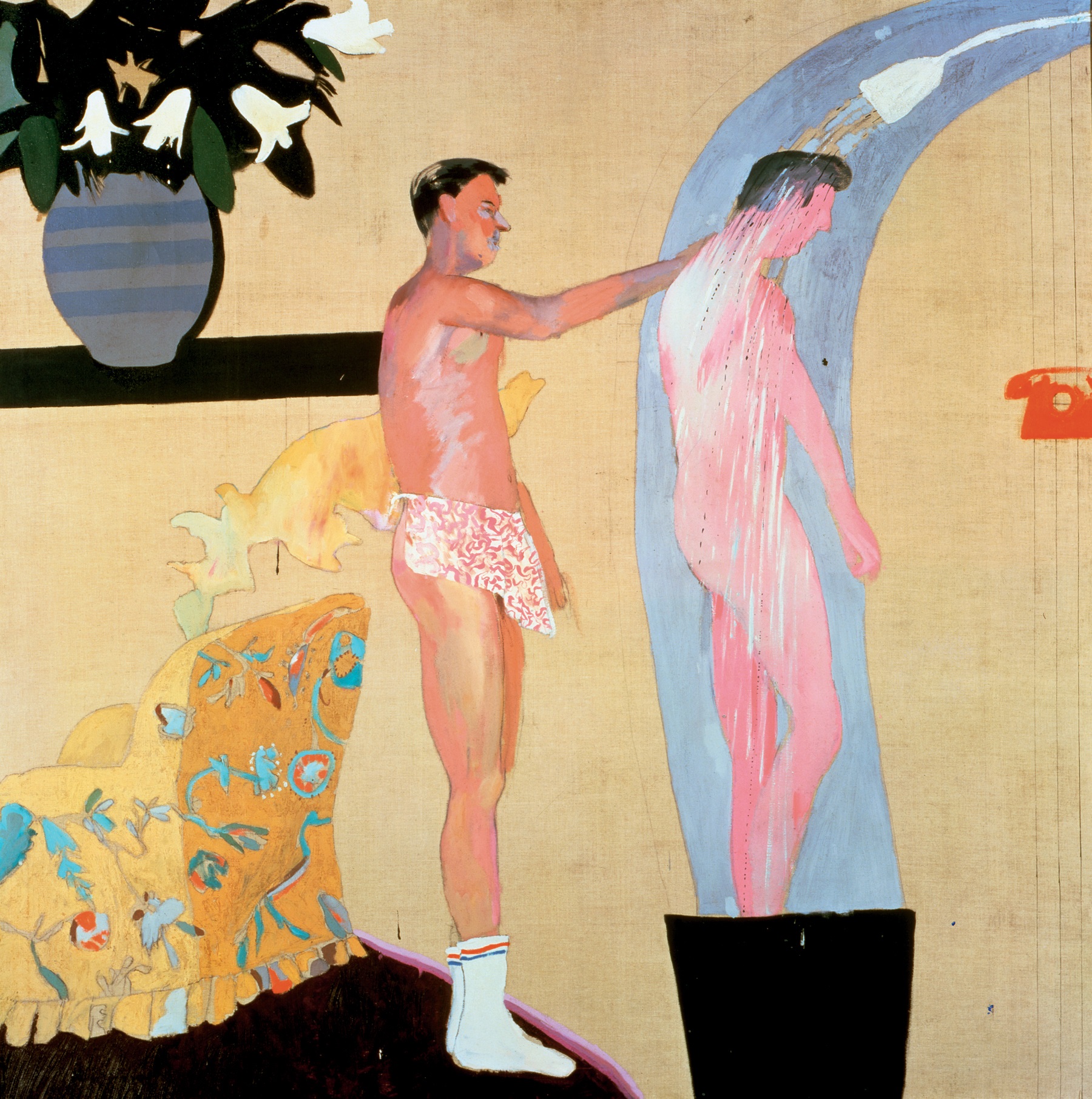

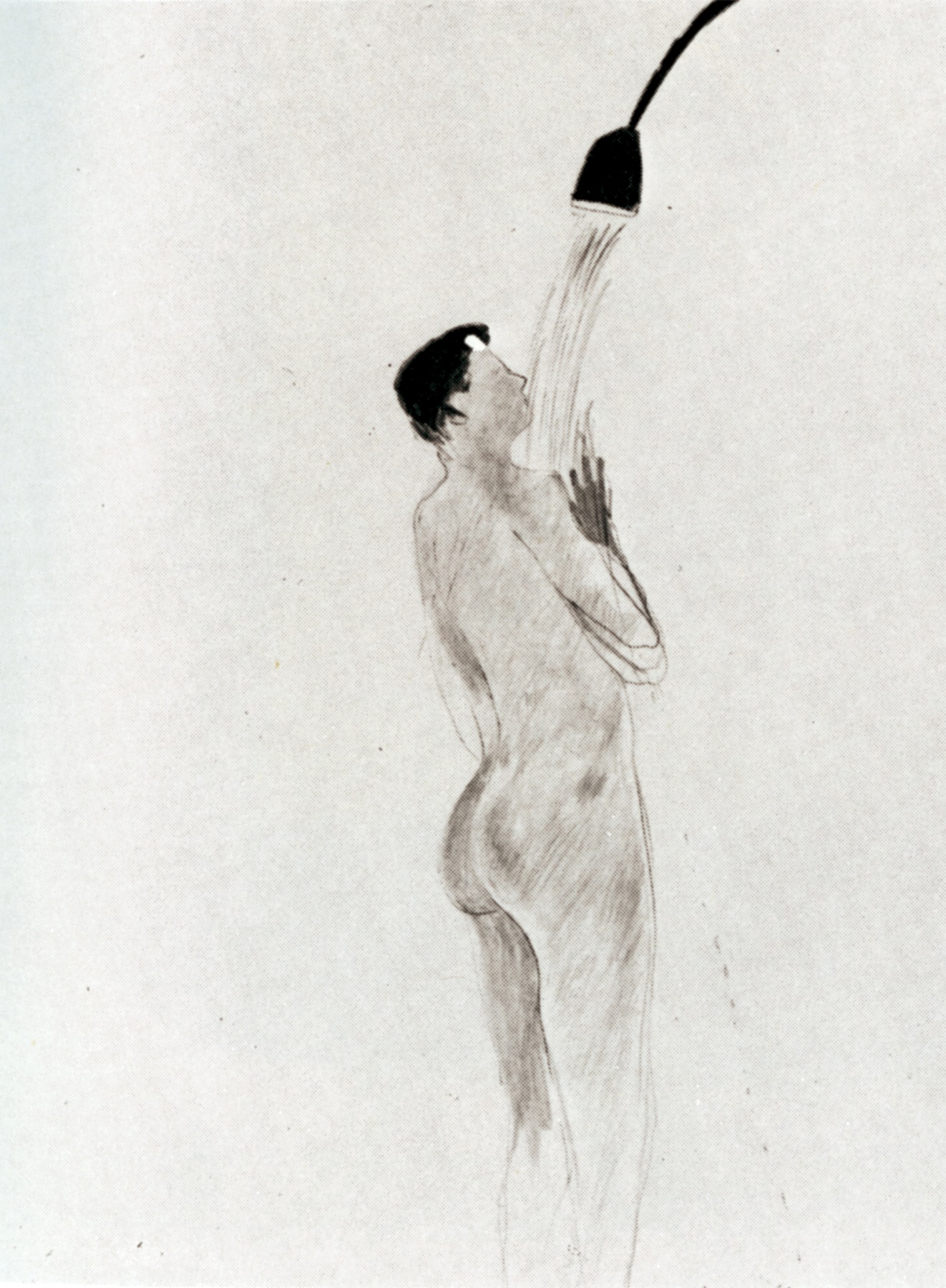

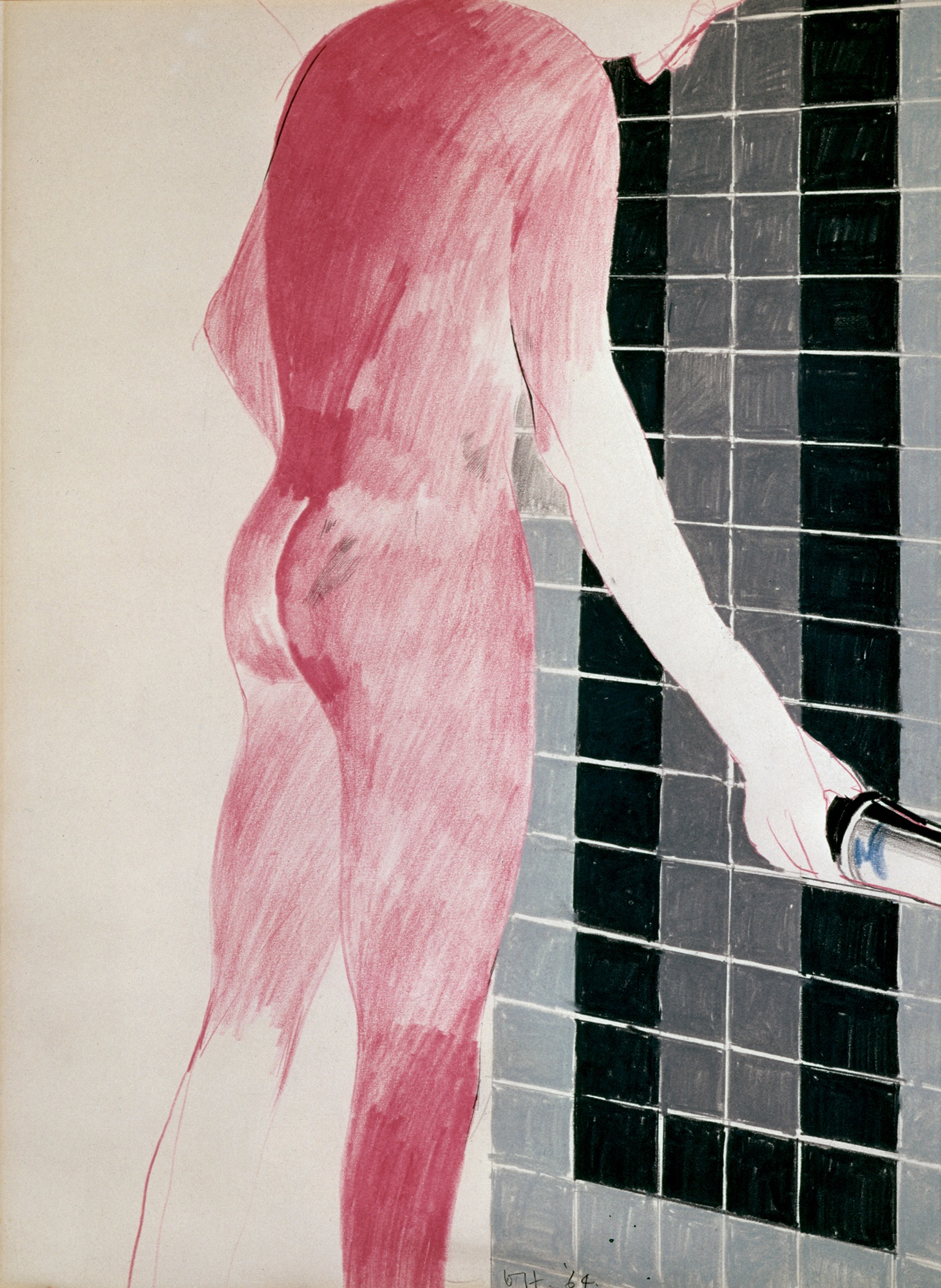

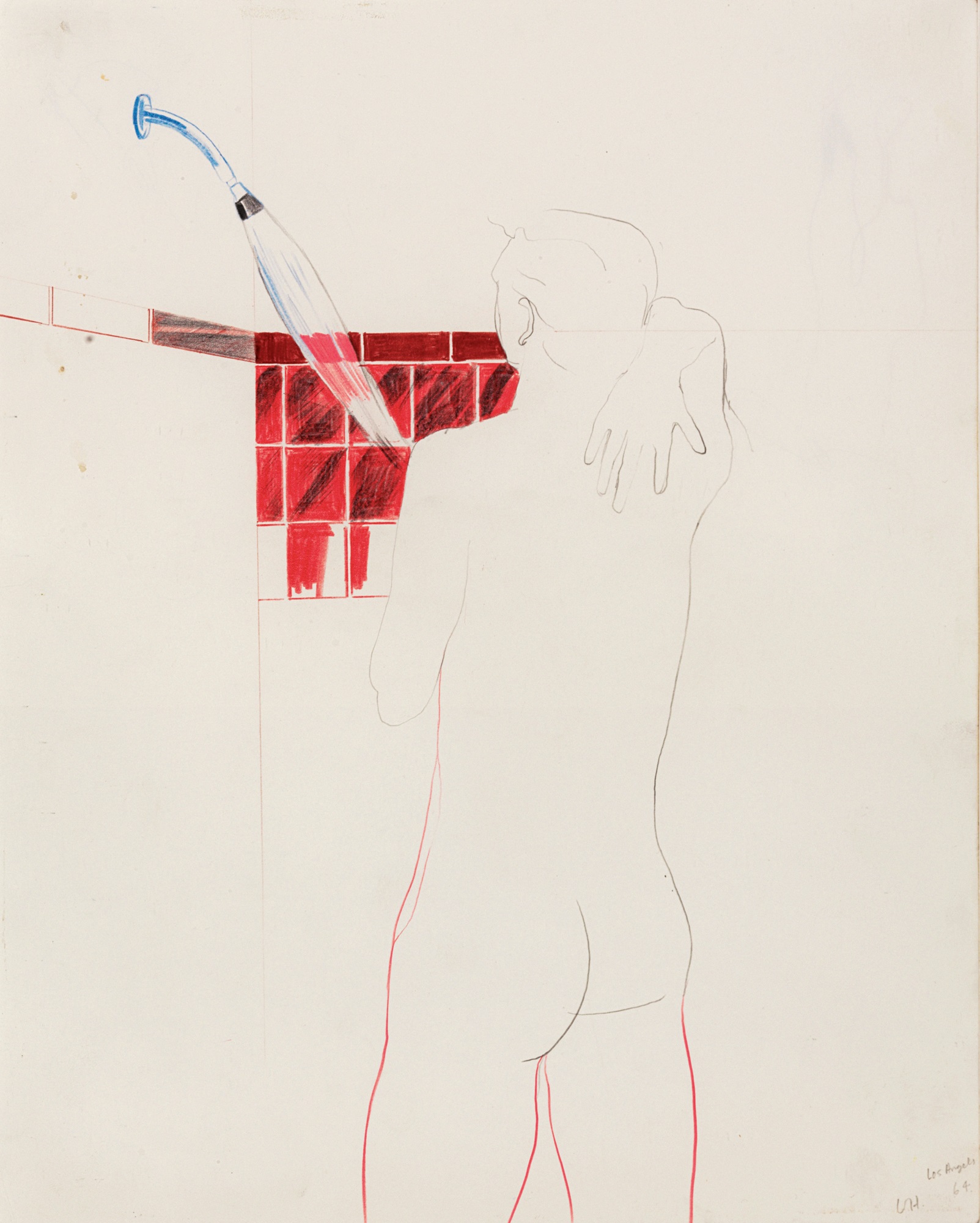

The same selectivity of vision marks the Domestic Scene, Los Angeles [37], painted early in 1963, many months before Hockney’s first visit to California. It is a mixture of observed fact, fabrication and fantasy. The subject itself is one which he saw as a contemporary version of the traditional theme of the bather, which has precedents as far back as the Renaissance and in our own century most notably in the paintings of Cézanne. The elements of Hockney’s picture, however, are wholly of his own time. The chair is the same one which had just appeared in Notting Hill, whisked into a new location simply through a change of context. The image of one man soaping another in the shower was borrowed from photographs in Physique Pictorial, a mildly homo-erotic magazine produced in Los Angeles; even the detail of the little apron coyly shielding one man’s genitals was suggested by a picture in this source. Hockney has not copied the photographs directly, however, but used them only as a source of ideas. The picture is invented with the aid of direct observation by recreating the scene for himself. Hockney remarks that he has always found it difficult to paint something unless he has seen it at some time for himself. Memory can be as useful a tool as working from life, but there is no substitute for experience. It was for this reason that he installed a shower on moving into his flat in Powis Terrace in 1962, encouraged no doubt by the vision of California hedonism to which he had already been introduced. Without further hesitation, he began at once to draw people washing in it. Boy Taking a Shower, 1962 [38], is one such drawing from life. The figure is depicted in an intentionally schematic manner, the legs trailing off into mere wisps of line and the anatomy brutally exaggerated, emphasizing the buttocks in particular, to intensify areas of erotic interest. Hockney’s concern is not to reproduce objectively what he has witnessed but to relate to us his own experience of what he has seen.

38 Boy Taking a Shower, 1962

39 Play within a Play, 1963

In the painting of the imaginary Los Angeles interior a similar stylization marks the representation not only of the figures but also of the water flowing from the spout. In a sense Hockney continues here to use the language of children’s art, depicting the falling water as a solid curve which is blatantly ‘unreal’ but which corresponds to the way in which we experience the motion of gravity. The image is thus strongly conceptual in its basis; it arises from what we think we know rather than simply from what we see. The same can be said of Domestic Scene, Broadchalke, Wilts [34], in which the highly formalized treatment of the reflections on the window as a series of thin diagonal lines reads as a sign for light rather than as an illusionistic representation of it. These images of water and glass are but the first of a continuing series in which Hockney meets the challenge of finding different ways of depicting transparent and reflective materials.

In a well-publicized statement written for the catalogue of the 1964 ‘New Generation’ exhibition, Hockney drew attention to the two extremes of his work, the concern with human dramas and the delight in technical devices, pointing out that the two approaches could sometimes be found within a single picture. The Domestic Scenes, although distinguished by Hockney’s usual delight in opposing styles, place the main emphasis on the confrontation of two figures. The specific identities of the men are not of particular importance; they are not named and there is no attempt to make them recognizable as particular people. If the artist did not tell us, we would be hard pressed to know that the men in Notting Hill were Ossie and Mo or that the two seated figures at Broadchalke were the artists Joe Tilson and Peter Phillips, since they are as anonymous as the pictures of people he would never meet, such as the bathers in the Los Angeles painting. The essence of the theme is a general one of friendship in its different forms of companionship, emotional commitment and sexual involvement. The homosexual milieu of Notting Hill is now presented as coolly as the meeting of artists in Wiltshire. Ossie and Mo are too involved in their lives even to take notice of the viewer; one sits in profile in contemplation, the other stands nonchalantly naked smoking a cigarette. The overtly propagandistic aspect of Hockney’s treatment of homosexuality has by this time more or less disappeared, since in depicting a world in which homosexual relationships and feelings are taken for granted, there is no longer any need for proselytizing.

The figure trapped between a pane of glass and a painted curtain in Play within a Play [39] can easily be identified as Hockney’s dealer John Kasmin. As the title makes clear, however, he is only an actor in a scene concocted by the artist, and for this reason we are unlikely to learn anything about him as an individual. The private joke of a dealer imprisoned by art does, however, deflect our attention on to the pictorial device from which the painting originated. The motif of the curtain as a picture within a picture, establishing a plane of illusion and a shallow pictorial space in which dramas could be enacted, was suggested by Domenichino’s Apollo Killing Cyclops [40], an early seventeenth-century painting which had just been acquired by the National Gallery. Hockney presents us with various levels of unreality, going so far as to depict the effect of Kasmin’s face and hands pressed against the back of the glass by adding painted marks to the front of the glass. The artist rests secure in the knowledge that the different levels of pictorial space will all meet, as they must do by definition, on the surface of the canvas, leaving him free to engage in illusions and to reveal dramatic human situations while maintaining the static quality of the image as an accumulation of painted marks. Hockney is thus able to maintain an allegiance to the tenets of Modernism while asserting the possibility of making pictures about anything he wishes.

40 Domenichino Apollo Killing Cyclops, 17th century

Excited by the possibility of finding inspiration anywhere and at any time, Hockney quickly developed the habit of drawing constantly. The imagery of many of his paintings of the early 1960s was first proposed on paper, sometimes, as in the sketch for the Tea Painting in an Illusionistic Style [29], as an invention towards a painting already in his mind. More commonly, however, it would appear that drawings were made in the first instance as independent works, and that of the many images thus produced only a certain number suggested possibilities for paintings.

41 Viareggio, August 1962

42 Shell Garage, Luxor, 1963