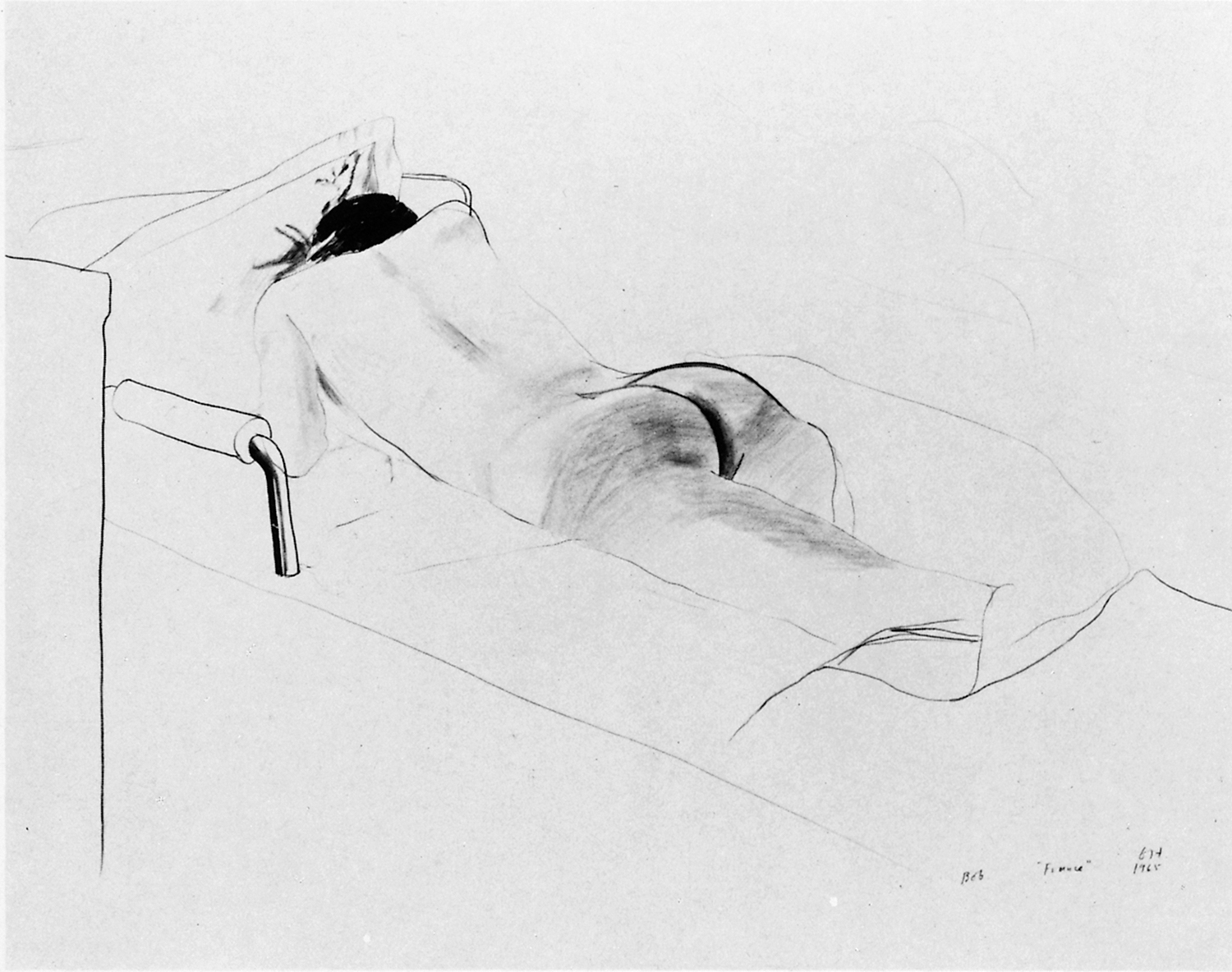

58 Bob, ‘France’, 1965

Hockney’s delight in artifice emerged in its most extreme form in the still-life paintings of 1965. At the time it might have seemed that he was once again on the verge of eliminating figurative references, as he had done for a short time during his initial year at the Royal College, but this was not to be the case. The still-life paintings are not quasi-abstractions but pictures about abstraction [54, 55]. In form they are deceptively empty, consisting of nothing but artistic devices, but Hockney has drawn attention to these devices as his subject, thus providing the pictures with a content that was lacking in his non-representational paintings of early 1960. Hindsight allows us to see these pictures as the culmination of one line of development within his work, as his purest statements concerning style as subject.

It may at first seem surprising that at the same time that he was making pictures about abstraction, Hockney in his drawings was beginning to transcribe ‘natural’ appearances in a way that had not greatly concerned him since his departure from Bradford College of Art in 1957. Working in contradictory modes, however, was entirely consistent with his view of style as an element to be chosen and used at will. It was a question simply of exchanging one set of pictorial conventions for another.

Since his arrival at the Royal College in 1959, Hockney had painted sporadically, but not consistently, from life. During this time he was involved with the ‘look of things’ mainly through the filter of a stylistic device. In California, on the other hand, he became much more interested in the specific appearance of objects and places. He began to use drawing as a medium for noting down what he saw as directly as possible, seeking to retain his sensations of the moment by tying them immediately to the page rather than attempting to hold them in the mind as vague memories.

Hockney’s use of drawing as a visual diary was an important factor in the emphasis on descriptive exactness in the paintings that followed in 1966, for it directed his attention to the characteristics that differentiate one object from another rather than to the general types or categories to which these objects belong. Without losing sight of the fact that there is no such thing as a ‘styleless’ style, that any form of representation makes use of a set of conventions, there nevertheless occurs a shift away from self-conscious style in favour of depiction. Devices continue to be in evidence, but they are now placed at the service of the image rather than brought to our notice as the primary subject of the picture.

Major changes were effected in Hockney’s drawing methods between 1965 and 1966. Many of the drawings of the early 1960s were in coloured crayons, with the emphasis on the surface texture as in the paintings of the same period. The style of execution was deliberately loose, the figure style consciously disjointed or schematized, and there was a tendency to organize a composition through the relation of fragments. Even when drawing from direct observation, as he did in Egypt in 1963, the strong element of exaggeration and stylization distanced the scene portrayed from reality.

The shift in function of drawing as a tool for observation can be seen as early as Bob, ‘France’ [58], drawn aboard ship on his return to England towards the end of 1965. It is self-evidently drawn from life, not only because of the convincing treatment of anatomy and the avoidance of stylization but also because of the way that the pencil lines and areas of pink crayon suggest the softness of the flesh and rounded mass of the figure. Amassing evidence in the most economical and expressive manner possible, contour rather than surface is the essential feature, since the enclosing line alone serves to define the form. The pencil line both describes the form and expresses the inner forces of the figure, while the selective use of pink crayon across the buttocks and the pose itself emphasize the man’s sexual desirability, taking for granted the homo-eroticism which less than five years earlier Hockney had promoted as a subject for strident propaganda. The sense of heaviness of the figure sprawled out on the bed, along with the carefully chosen details such as the guardrail by the edge of the bed and the sheets gathered over the man’s feet, convince us that the scene was witnessed rather than invented. Hockney ensures, however, that we experience the figure sensually, and not only in terms of its beauty, by concentrating our attention through line as well as colour; the right buttock trails off into nothing, leaving the figure with only one visible leg, and the pinkness of the flesh is presented in those areas that Hockney finds especially appealing.

58 Bob, ‘France’, 1965

59 Michael and Ann (Upton), December 1965

A similar combination of selectiveness with attention to observed detail can be found in Michael and Ann Upton [59], a crayon drawing from December 1965. This heralds a new use of the medium of coloured crayons in Hockney’s work. The concern for surface textures found in his earlier crayon drawings persists, but it is now subservient to a more tightly descriptive form and to the decorative impact of colour and mise-en-page. The medium continues to serve as an equivalent on a reduced scale for his paintings, but where he once would have emphasized the invented quality of the images and their physical presence as a deposit of colour on the surface, he now draws our attention to the subject as an observed reality and to the fabrication of the image as a direct response to what he sees. The sitters in this, as in many of Hockney’s later drawings, are close friends. Because he knows them well, there is no need to insist on achieving a likeness; it is assumed that this will emerge naturally and that it can be caught as much in the pose and facial expressions as in the person’s features. Essentially these drawings arise from an urge to make or deepen contact with other people, and as such their role is a far more intimate one on the whole than that of the paintings. ‘I did learn quickly,’ Hockney recalls, ‘not to bother what the reaction of the sitter was. It’s not much to do with them, really. I’m not making the drawings for them, I’m making them for myself.’

60 Kenneth Hockney, 1965

Kenneth Hockney [60], a portrait of the artist’s father drawn in 1965, was one of his first line drawings in ink, and it is evident from the rather awkward result that he was still struggling with the medium. There are particular difficulties with the head, parts of which have been redrawn twice in an attempt to find the right contour, and the rather arbitrary marks on the sleeves and trouser legs reveal that the problem of depicting folded cloth through line alone proved equally troublesome. Hockney acknowledges that he has not captured the character of the sitter, but adds that ‘if you’re going to experiment, you must expect failure’. The idea of making line drawings of the figure attracted him because of the very difficulty of the enterprise, a challenge which appealed to him even more because of the fact that so few twentieth-century artists had attempted them. There are still resemblances, almost certainly as a result of habit rather than intention, between the drawing of his father and the rather caricatural drawings he had made in the early part of the decade under the influence of George Grosz. Stylization in this case appears to be the result simply of inexperience. Hockney’s solution was to improve his technique by giving himself an intensive course in drawing from life. It is difficult not to agree with his own estimate that his line drawings are among his greatest achievements and that they have consistently improved over the years, with the line itself becoming more beautiful as well as more economical in transmitting information.

61 Boys in Bed, Beirut, 1966

62 In the Dull Village from Illustrations for Fourteen Poems from C. P. Cavafy, 1966–67

The expressive potential of line suggested by the new drawings was vividly realized in the Illustrations for Fourteen Poems from C. P. Cavafy, 1966–67 [62, 63], Hockney’s first major series of etchings since A Rake’s Progress [1, 25]. Hockney had made occasional reference to Cavafy’s writing in earlier prints and in A Grand Procession of Dignitaries [27] of 1961, but it was only with this book of etchings that he was able at last to produce a major statement inspired by the poet. The idea for the series was Hockney’s own, but his original intention of illustrating a far more ambitious range of poems proved impracticable and it was decided only to include those on the subject of homosexual love. Plans to use John Mavrogordato’s translations were also rejected because of copyright problems, so it was decided to produce a new translation. Stephen Spender, who had earlier purchased etchings from Hockney, introduced him to Nikos Stangos, and together the two poets devised the texts that were published with the etchings in 1967.

Hockney went to Beirut at the beginning of 1966 to draw, as a way of researching imagery for the prints. Beirut seemed to him to be the contemporary equivalent of Cavafy’s Alexandria, in that it had now replaced Alexandria as the most cosmopolitan city of the Middle East. The trip provided Hockney with architectural settings of suitably Arabian character for three of the prints, but what he most wanted was simply to get the flavour of the place and its way of life. The poems, however, have a far more general application as reveries on human relationships, and Hockney thus felt free to take inspiration from his own experience and environment. Boys in Bed, Beirut [61], an ink drawing which (unusually for Hockney) was copied on to the plate for one of the prints, According to the Prescriptions of Ancient Magicians, was actually drawn in London using two of his friends as models. The demands of the project forced Hockney to break some of his own habits, since if he had planned this as a self-sufficient drawing it would not have occurred to him to pose the boys in the middle of an action in this way. Some alterations were made in redrawing the image on to the plate: the figure in bed has been cropped by the framing edge, and the entire image has been shifted further up the page; the vertical line defining the corner of the room has been eliminated; and details such as the hand of the standing figure, which is badly defined in the drawing, have been redrawn, though judging from the still awkward result it is questionable whether this was done from direct observation.

Photographs were also used as reference material, especially for the prints which Hockney describes as ‘very posed’, such as In an Old Book and The Beginning, as well as for the portraits of Cavafy, where he had no choice. It is a solution, however, which he finds far from satisfactory: ‘Things like weight and volume are very hard to get from a photograph. You don’t get the information you need to be able to do the line. You could draw in another way from a photograph or you could draw it imaginatively, you could really interpret it, but if I was trying to draw you now I would find it a lot better to have you there rather than for me to take a photograph. I can often tell when drawings are done from photographs, because you can tell what they miss out, what the camera misses out: usually weight and volume, there’s a flatness to them.’

63 Portrait of Cavafy II from Illustrations for Fourteen Poems from C. P. Cavafy, 1966–67

Portrait of Cavafy II [63] depicts the poet in front of an architectural setting copied from a drawing made by Hockney of a police station in Beirut. Although the mise-en-page has been altered and the entire image has been reversed in printing, the drawing has otherwise been transcribed faithfully, retaining even the modern car in the foreground. Hockney seems unworried about any such anachronisms, for if modern Beirut has the flavour of Cavafy’s Alexandria, then it follows that it is more important for him to be faithful to his observations than to attempt an accurate historical reconstruction. The images, like the English texts which they accompany, are conceived as a translation into a language in current use.

The appeal of Cavafy’s lines for Hockney lies not so much in particular images as in the atmosphere they generate: the sense of wistful nostalgia for events in the past, for fleeting experiences, for people with whom one has had brief but memorable contact; the conviction that history is not only continuous in a linear fashion, but that the past remains alive because human nature is essentially constant; and the sense of being torn between a deep interest in other people and the ultimate need to remain aloof, a spectator of other people’s lives. These attitudes are strongly present in Hockney’s own work. By nature they are rather intangible qualities, and it is difficult to say whether Cavafy has influenced Hockney’s way of thinking or whether Cavafy’s writing could be assimilated by the painter because he already ‘thought like a poet’. One thing that is clear is that the accuracy with which Hockney presents these encounters has much to do with the fact that he has observed and participated in similar situations himself. His own memories of experiences such as that depicted in the 1964 drawing Two Figures by Bed with Cushions [47] inevitably will have coloured his conception of the prints, and it is this capacity to draw on personal insights which provides this series with its sense of authenticity.

Only a small number of the Cavafy etchings (He Enquired After the Quality, The Shop Window of a Tobacco Store) depict a particular place or scene as described in the poem. The prints demand, instead, to be appreciated as a group of recollections or visions which in their totality provide an experience similar to that suggested by the poems. This is attested to by the fact that Hockney did not have the poems by his side while he was working and did not conceive of each image as an illustration of a particular poem; the reverse is, in fact, the case, for instead of choosing the poems first, he and Nikos Stangos assigned poems to the etchings only after the prints were done. Five etchings planned for the series were rejected at this stage, either because Hockney did not consider them good enough or because they disrupted the continuity of the set. If Hockney can be said to resort to illustration in many of his paintings, it is paradoxical that when he does come to illustrate literary texts his approach is not that of the conventional illustrator. The Cavafy prints are not literal depictions of the subject-matter of each poem but a visual equivalent to the mood and theme of all Cavafy’s homo-erotic poetry, just as the later Grimm etchings are evocations of a particular world rather than illustrations of events described in the narrative. The Cavafy images create an almost musical sequence in their variations on the theme of two men, the deliberate repetition of the pairings conveying the sense of ritualized action at which the poet hints: the endless pick-ups in anonymous settings, the urgent need to relate to another human being. The delight in physical sensation is transmitted not only by the imagery of lithe nude bodies but also by the formal sparsity of the compositions and by the emphasis on tactility effected by the contrast of the wiry etched lines against the smooth surfaces of white paper.

The Cavafy etchings are conceived almost entirely in terms of line, unlike Hockney’s earlier prints in the medium, which relied to a great degree on aquatint, on gestural scribbles and on variations of tone and surface. Two years had passed since he had made any etchings, and when he now returned to them it was with the intention of putting to use what he had learned from drawing the figure in pen and ink. The Cavafy prints are, in effect, the most accomplished line drawings that Hockney had yet made.

Hockney has consistently favoured etching over other printmaking media; he appreciates its flexibility and the fact that he can retain full technical control over its production. The equipment and technical expertise required for lithography, for instance, is more complicated, and it was for this reason that Hockney, having made three lithographs at art school in 1954, did not return to the medium until invited to do so ten years later by the Atelier Matthieu in Zürich. He experimented only once with screenprinting, probably the most popular and certainly the most influential graphic medium of the 1960s, at the instigation of the Institute of Contemporary Arts. The result, Cleanliness is Next to Godliness [64], he regards as his worst print; he allowed it to be published only because it was part of a commission involving other artists. This was the only occasion on which Hockney used a camera-produced image in a print, rather uncomfortably masking a photograph culled from a physique magazine with a hand-cut stencil representing a shower curtain. It is a disjointed and incoherent image; the pool of water, for instance, is a fragment of a Harold Cohen screenprint, a witty reference but an unsatisfactory visual solution. What Hockney most disliked about screenprinting, however, was the mechanical nature of the process, the fact that it does not depend on the autographic mark. Curiously, the flat areas of colour in Hockney’s paintings of the mid-1960s have much in common with the formal qualities of screenprints produced with the aid of hand-cut stencils, implying that his sensibility may have been affected by the work of other artists in this graphic medium. Hockney agrees that some of the imagery he was using in his work at that time, above all the swimming pools, might have lent itself to screenprinting, but says that in California there was no screenprinter with whom he could have worked who was comparable to Chris Prater of the Kelpra Studios in London. In any case, his dissatisfaction with the one print he did produce with Prater caused him to reject the possibility of working again in this medium.

64 Cleanliness is Next to Godliness, 1964

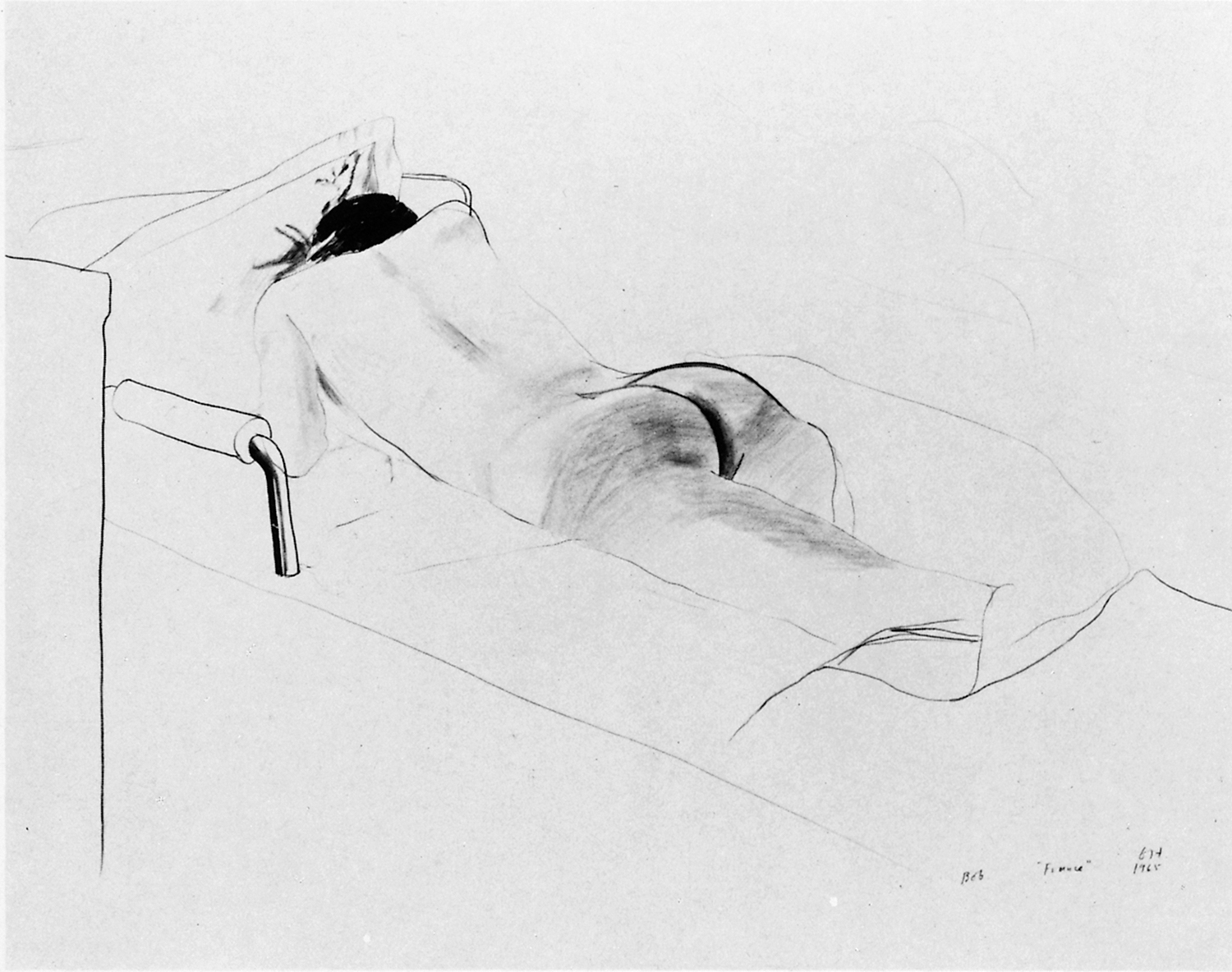

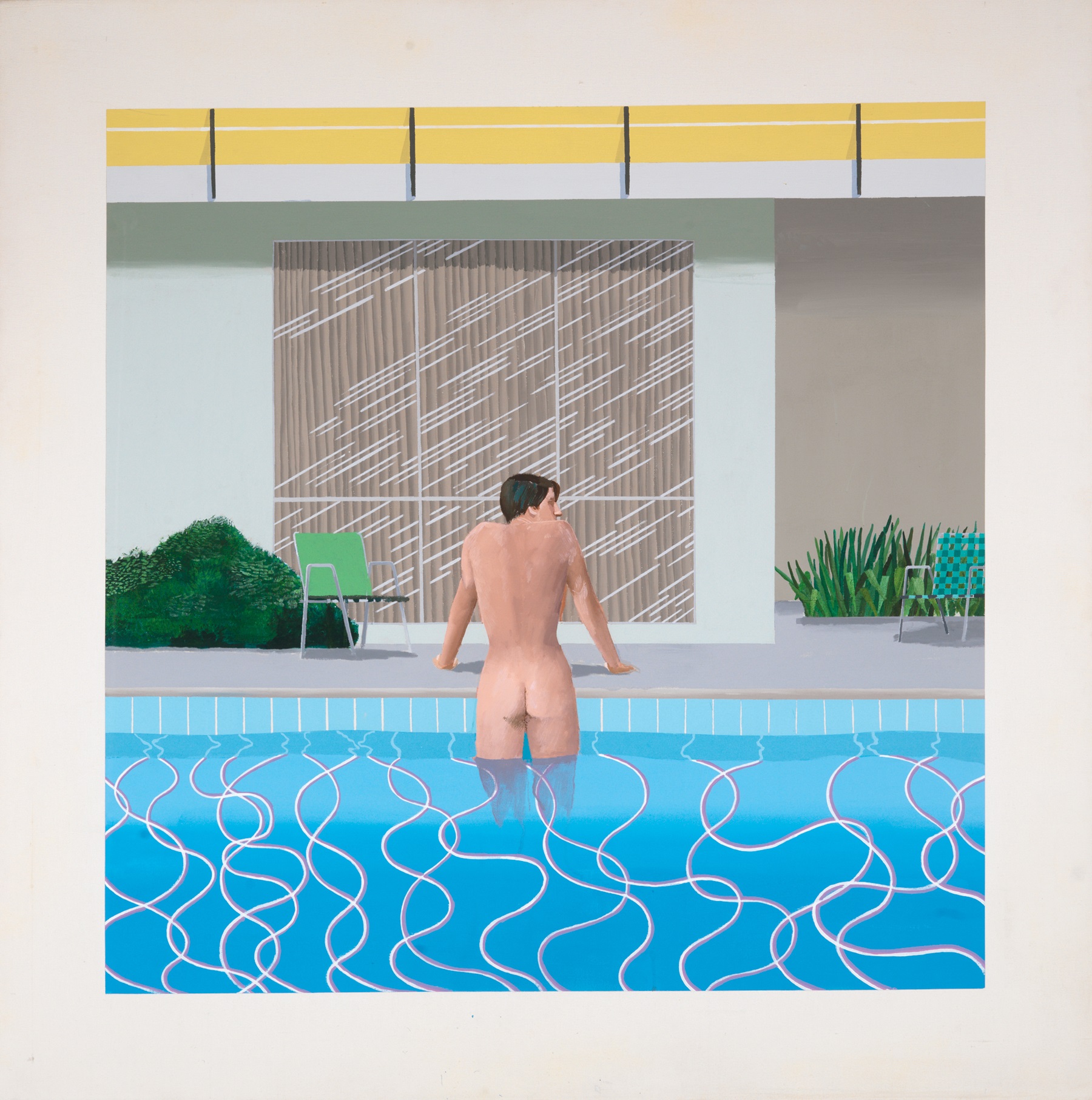

One of Hockney’s strengths has been his willingness to extend his work, even at the risk of failure, into a new medium or context. It is this enthusiasm for experiment that led him to accept a commission from the Royal Court theatre to design a production of the Alfred Jarry play Ubu Roi in 1966. Even though his own preoccupations in recent months had been with devising a more naturalistic rendering of the human figure in his life drawings and the Cavafy prints, the challenge of working from the imagination for the stage greatly appealed to him. He was afraid at first that the theatrical devices he had used in his earlier paintings would simply disappear if transferred again to the stage, but he was encouraged by the knockabout humour of the play, its rapid scene changes and the author’s written instructions to keep the designs simple rather than bothering with traditional scenery. Hockney followed the spirit of the advice very closely and presented the play, first performed in 1896, as a series of conceptual tableaux. Much of the fun lies in establishing a simple visual equivalent for the often riotous action of the play. The entire Polish Army consists of two uniformed men with an identifying banner wrapped round them [65], while the parade ground is established simply by placing on stage a series of letters which spell out the location. Most of the scenes were done as small backdrops measuring eight by twelve feet, so they are presented in effect as a series of static visual images which define a specific space for the human participants. Hockney’s favoured framing device is used for the arrival of the Polish royal family [66], describing the scene as a picture within a picture by mimicking the conventions of official group portraiture.

65 Polish Army from Ubu Roi, 1966

66 The Polish Royal Family fromUbu Roi, 1966

The Ubu designs come at the end of Hockney’s period of involvement with the notion of versatility of style. Both the requirements of the play and Hockney’s delight in the artificial led him to an exaggerated and anti-naturalistic treatment that was at odds with the development of the rest of his work at that time. It is doubtful, however, that naturalism would ever have appealed to him in the theatre in the way that it did in his paintings. He did not work for the stage again until he designed The Rake’s Progress [140–41] nine years later, simply because no one asked him, but his delight in contradiction leads one to suspect that he would always have favoured a more stylized idiom in this context. The fact that real people are making real actions appears to encourage him to provide a blatantly artificial setting for their activities, so that their metaphorical content can be better perceived. The audience should remain conscious that what they witness is a parallel to, or analysis of, life rather than its imitation. Hockney recognizes that there is a danger, too, in over-simplification, for if the sets are too minimal they can be distracting and obtrusive. What matters fundamentally is that it all be of a piece: ‘In the theatre you must believe. And you can believe many things, so long as they have a unity!’

The backdrops which Hockney used in the Ubu plays may well have clarified his ideas for the more naturalistic paintings which followed on his return to California in the summer of 1966. The notion of the rectangle of the canvas as a setting for human activity exists in seminal form in earlier works, but usually in terms of a generalized stage, as in The Hypnotist, 1963, or in terms of scattered objects and props within the neutral setting of the canvas, as in the Domestic Scenes of 1963 [34, 36, 37]. In 1964 he had begun to devote much more attention to the architectural settings, in the shower paintings as well as in California Art Collector [67], but it was only in the second half of 1966 that he began to place real people within identifiable settings.

A comparison between Beverly Hills Housewife [68], the first painting that he began on his return to California, with his treatment of a similar subject in California Art Collector, 1964, displays the enormous shift which had occurred in Hockney’s work over this two-year period. The earlier picture is, in his own words, ‘a complete invention’, although details such as the primitive head, the William Turnbull sculpture and the fluffy carpets are drawn from his observations of typical homes of well-to-do collectors in Los Angeles. The figure, however, is not a portrait, and the house is only a notional one, borrowed from the simplified settings characteristic of Early Renaissance paintings (see, for example, the figure beneath a loggia in the scene of the Annunciation to St Anne by Giotto in the Scrovegni Chapel, Padua). The swimming pool in the background was copied from a newspaper advertisement, although Hockney insists that the photograph is not the real source material but only a visual reference that happens to be in a convenient and accessible form. He had observed that swimming pools were a common feature of Los Angeles homes, and decided to put one in his painting; only now did he set about looking for a picture of a pool as a ‘memory-jogger’.

67 California Art Collector, 1964

Beverly Hills Housewife [68], measuring six by twelve feet, was Hockney’s largest and most ambitious picture for some time. The relationship of the figure to its architectural setting continues to refer to Early Renaissance prototypes such as Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation of Christ [69], in which the figures are depicted as if performing on a platform, but Hockney has based the details of his painting on a small group of grainy, badly lit black and white photographs of Betty Freeman standing on the porch outside her home [70]. Hockney had purchased his first camera, a Polaroid, in 1964, and he used it at first only for ‘odd little details’, still relying on invention rather than using the photograph as a source of information for the picture as a whole. The close-up of Betty Freeman is so small and lacking in definition as to provide only the most meagre assistance in building up the stance and features of the figure. Hockney has used other elements visible in the photographs, such as the curtained window and the Turnbull sculpture, but has taken enormous liberties in interpreting these images in paint. The position of the pole which holds up the balcony has, for example, been moved back to avoid a sense of clutter in the foreground, and the spiky plant which occupies a central position in the right-hand panel has been added as a kind of companion for the woman.

68 Beverly Hills Housewife, 1966–67

69 Piero della Francesca The Flagellation of Christ, 1455

In spite of Hockney’s rather casual attitude to photography at this time, its introduction as an integral part of his working methods had a great impact in changing the orientation of his work. The use of photographs as an adjunct to drawings corresponds to a highly traditional system of organizing a composition with its subsidiary details, a procedure which inevitably places a premium on depiction and leads to an increasing clarification of image. The process of making a picture began to take longer, also as a result of the characteristics of acrylic paint, which he had begun to use in 1964; because acrylic dries quickly and cannot be scraped off the canvas, it demands a greater degree of pre-planning than oil. Hockney’s naturalistic paintings, conceived one step at a time and painted with great deliberation, by definition cannot have the apparent spontaneity of image and fluidity of paint of the earlier work. The emphasis on intuition and immediacy was bound to give way to a more rigid and calculated conception and technique.

70 Betty Freeman, Beverly Hills, 1966

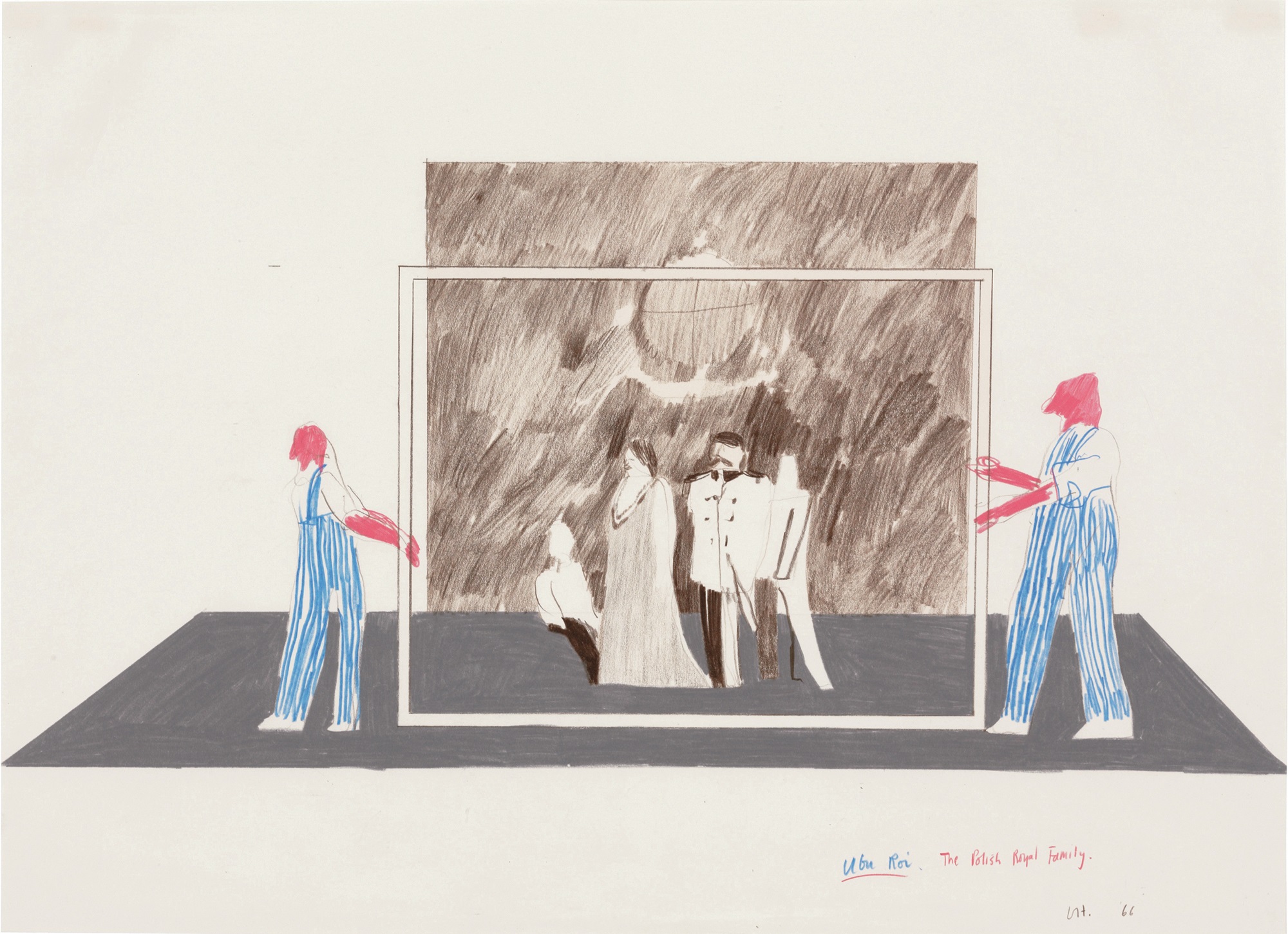

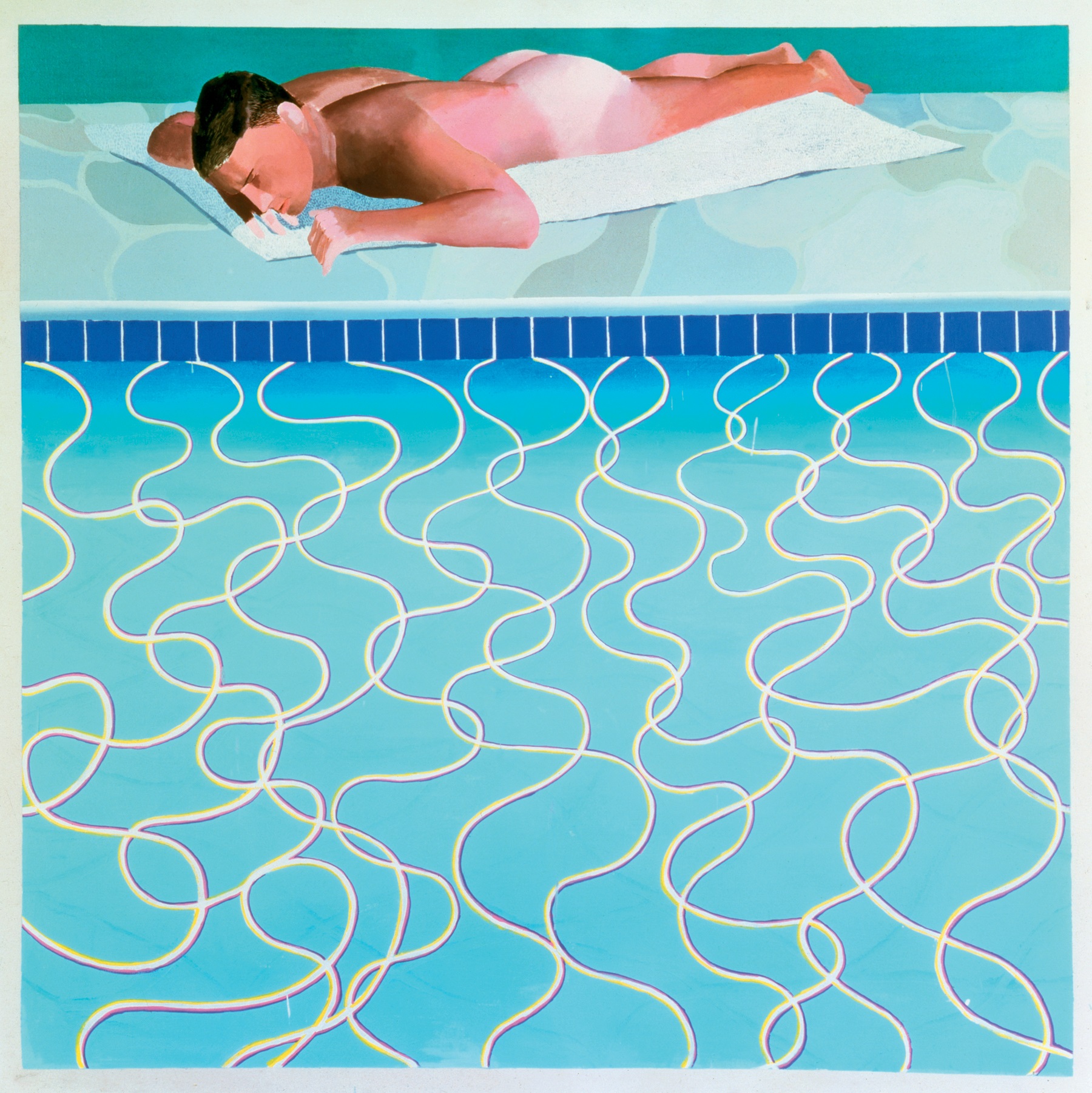

Hockney did not simply chance upon the camera and then allow it to exert its influence. It is clear, rather, that he became interested in the camera at this time because he surmised that it would be a useful tool in making pictures which communicated his pleasure in the specific qualities of the environment in which he was now living. Paintings such as Beverly Hills Housewife [68] and Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool [71] are, in the first instance, evocations of southern California as a land of sunshine, leisure and affluence. If in certain works, such as Sunbather, 1966 [73], there is more than a hint of the language of the travel brochure, this is not inappropriate, for Hockney’s idyllic vision of carefree life in Los Angeles is unashamedly that of a foreigner. The dozing figure in this painting is, in fact, based on an illustration in a magazine.

71 Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool, 1966

‘I think that buying the camera’, Hockney recalls, ‘coincided with an interest in making pictures that were depicting a place and people in a particular place. Certainly in California in ’65/’66 when I had begun to do that, using only rather poor Polaroid photographs to jog my memory – the paintings on the whole still invented – I’d never taken that much interest in photography at all. I still go hot and cold now.’

It was only in 1967 that Hockney collected his photographs together, many of which had in fact been taken by other people, and began to mount them in large leather-bound albums. By 1980 he had filled more than sixty. The first album, however, covers a period of six years, July 1961–August 1967, whereas subsequent albums cover a period of months or even days. This testifies to the casual attitude which he took to photography at first:

‘When I first took photographs I just took them rather like anybody takes snaps. The more you travelled, the more you took photographs. They were mostly just of friends. I didn’t bother composing photographs, the compositions weren’t that important. It took me a while to realize you could compose with a camera in a certain way, simply because I didn’t take it very seriously. It was just a record, like anybody would keep a record of photographs of friends. Then I started photographing things that I thought I might use, architectural details of things as you travelled. I’ve fluctuated over the years with the camera, sometimes using it a lot, sometimes not.’

72 Photograph taken for painting Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool, 1966

Polaroid photographs were referred to in painting both the figure and architecture of Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool [71, 72]. The intermediate role of the camera is made evident in the format of a square image within a plain canvas border, which immediately calls to mind a photographic print. In a sense it is a snapshot souvenir of his experience of America, and specifically of the homosexual subculture of Los Angeles; Peter Schlesinger was his new boyfriend, an art student whom he had met while teaching at U.C.L.A., and the owner of the pool, Nick Wilder, was a dealer specializing in contemporary art with whom Hockney had lived earlier in the year. Making the canvas look like a grossly enlarged snapshot also provides an updating of the canvas as object-equation which had interested him in the Tea Paintings and related works of five years earlier. Since the viewer knows that a photograph is flat, the artist is free to imply spatial depth while maintaining the literal reality of the image as paint on a flat surface.

This painting is not a mere transcription of a single photograph. Peter was leaning against a car, not pulling himself out of a swimming pool, when Hockney snapped the shutter, and the play of shadows across his back in the Polaroid is disregarded. The reflections on the window here and in Beverly Hills Housewife [68] were not set down from direct observation outdoors nor even based on the evidence of the photographs; the regular diagonal lines are copied from the type of illustrations found in mail-order catalogues, where they function as a kind of visual shorthand signifying light on a hard reflective surface. The interlaced curved lines in the pool are not exactly as Hockney would have perceived the patterns on the tiled floor through moving water; they are abstracted signs of flowing movement that are knowingly borrowed from the sinuous forms of Art Nouveau. What might have appeared at first sight as a straightforward naturalistic description thus emerges as a composite view. Each element, carefully studied and (in the best sense) highly contrived, has passed through a filtering process of simplification and stylization. Through the combination of references, Hockney insists on the role of long-established pictorial devices allied to direct observation in the formulation of the painted image.

As late as 1965, Hockney’s fascination with pictorial devices was presented within formats which deliberately scattered the viewer’s attention across the surface, drawing attention to these devices only to deny their apparent function. In his new paintings such self-evident devices would have jarred and become intrusive to the point of obliterating the subject, breaking the spell of the ideal vision he was transmitting. His attention thus shifted to the formalized structure of the composition in support of the picture’s theme. For the sake of convenience, this could be labelled a ‘classical’ impetus in his work of this period, in the sense, for instance, of Seurat’s involvement with linear directions and with rigid geometrical frameworks as aids to the communication of feeling or of the urge to seek order in the visible world.

A firm vertical/horizontal structure, often accounted for by settings of severe rectilinearity, is a characteristic feature of Hockney’s paintings of this period. The architecture in a picture such as Portrait of Nick Wilder [74] provides a metaphor for the construction of the composition. The rectilinear grid, moreover, establishes a strong consciousness of the surface on which the image rests, while at the same time suggesting real space through the identification of this grid with a three-dimensional setting. The urge to assert the primacy of the picture plane, the most-discussed feature of Modernist painting at the time, is particularly noticeable in Hockney’s paintings from 1966 in spite of his wish to provide his figures with a convincing solidity of mass. In many of these pictures a continuous horizontal band extends across the whole of the image area as a visual echo of the framing edge, as with the band of blue tiles in Sunbather [73], reminding the viewer that the only space contained by a painting is the distance across its surface. Hockney had recently met Frank Stella, whose work he already knew through exhibitions with his London dealer Kasmin, and it seems likely that the American’s early paintings of horizontal bands directed Hockney to relate the image to the external form of the canvas in this fashion. At the very least one can say that the overt formalization of structure, notwithstanding its antecedents in the art of Poussin and other ‘classical’ painters, is the product of a mid-twentieth-century sensibility.

73 Sunbather, 1966

The crispness and descriptive clarity of Portrait of Nick Wilder would be unthinkable without the experience provided by Hockney’s recent, more exacting line drawings, just as the devotion to a more homogeneous space and to the observation of the fall of light within a particular setting owes much to the lessons learned from photography. This is, moreover, Hockney’s first fully explicit portrait in a painting since that of his father eleven years earlier, since even Beverly Hills Housewife [68] does not make a particular point of the identity of the sitter. In contrast to the first swimming pool pictures of 1964–65, paintings still deliberately crudely worked and full of spatial distortions and inconsistencies, the Portrait of Nick Wilder and related works reveal an urge to depict the world perceived through the eyes with as great a specificity as possible. The very title of the picture suggests that Hockney realized at once that it was something of a breakthrough to depict someone so that he could be recognized, after years of making pictures about people without dealing fully with their individuality.

74 Portrait of Nick Wilder, 1966

‘Painting portraits took quite a while to come to. I think I always wanted to do portraits, but you were so tied to those boring old Royal Academy ideas. The portraits, after all, of Picasso and Matisse were not the ones that were being thrust at you, they’re not even now. Now I have come to the conclusion that painted portraits are infinitely more interesting than photographic portraits. Painting has completely abdicated to the camera in portraiture, which is a pity; I’m sure it will come back. The painting of people is too deep in us, everybody is interested in faces. To tell you about another person is a very deep thing in people, and it’s going to come out in some way or other.’

75 Nick Wilder, 1966

In planning the Portrait of Nick Wilder Hockney referred to photographs [74, 75] taken in the pool by the painter Mark Lancaster under his directions, but his excitement at painting a portrait led him at the same time to draw portraits from life with greater determination than ever. Single-figure studies are rare in Hockney’s paintings, probably because the larger scale and the technical requirements of the medium demand a degree of formality and detachment, whereas drawings of one person are much more frequent, since they can be made anywhere in one sitting as an intimate and essentially private confrontation. With the move towards naturalism, drawing becomes for Hockney not only a way of learning how to look, but also a means of getting to know a person through intense concentration. He thus tends to return incessantly to the same models, finding out about the different facets of their appearance as clues to the complexity of their personality and of their relationship to the artist.

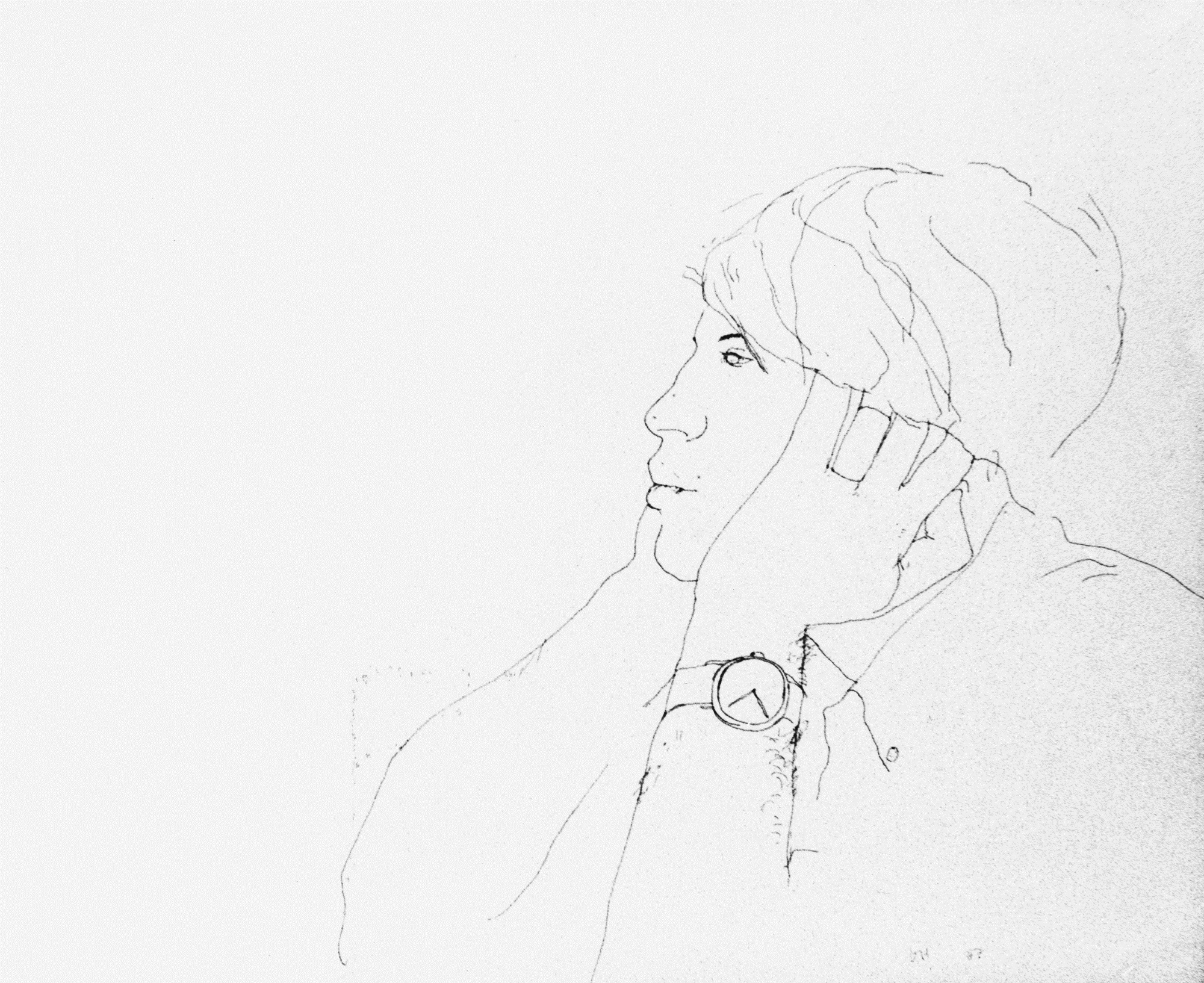

Peter Schlesinger, whom Hockney had met and become sexually and romantically involved with on his return to California that summer, became his preferred model almost at once. A group of line drawings made in the last months of 1966 were the first to capitalize on the economy of outline first evident in the Cavafy etchings, with a similar sense of the tactile sensual appeal of the blank paper itself and a handling of a continuous contour as a physical caress of the forms described. One such drawing, Peter, La Plaza Motel, Santa Cruz [76], is especially revealing of the increased authority of Hockney’s line because of the similarity in subject to some of the Cavafy prints. More is achieved with fewer lines; each line now seems absolutely necessary to the description of form as well as to the elegance of the surface design. Some critics have criticized Hockney’s drawings as lacking in passion, saying for instance that Peter is drawn with the same detachment as any object which happens to catch his eye. The reticence is deceptive, however, for in the choice of subject alone Hockney has already declared an emotional attachment. In a drawing such as Peter Schlesinger, 1967 [77], everything is pared away save for the young man, who is described with a tautness and sensitivity of line that strongly avows a tenderness of feeling and intensity of involvement.

76 Peter, La Plaza Motel, Santa Cruz, 1966

77 Peter Schlesinger, 1967

Hockney’s drawings of Peter reveal a remarkable advance in his assurance. The delicacy of Dream Inn, Santa Cruz, October 1966 [78], is in full contrast to the boldness, sense of urgency and even roughness of much of his earlier work. The figure is drawn entirely in pencil, its fragility emphasized by the crayoned areas of deep blue at the right and the balancing strips of yellow and orange at the left. It is an image imbued with silence, particularly undeclamatory when compared with the more robustly decorative quality of Hockney’s other crayon drawings of this period. The tranquillity and gentleness of this picture evidently has much to do with the peace of mind that Hockney had within the relationship, just as his delight in his friend’s physical beauty encouraged him to depict him with an acuteness of vision free of distortions and stylistic conceits. Peter was himself training as an artist and seemed to Hockney to have everything he sought in another human being: ‘It was incredible to me to meet in California a young, very sexy, attractive boy who was also curious and intelligent. In California you can meet curious and intelligent people, but generally they’re not the sexy boy of your fantasy as well. To me this was incredible; it was more real. The fantasy part disappeared because it was the real person you could talk to.’

78 Dream Inn, Santa Cruz, October 1966, 1966

79 Peter Having a Bath in Chartres, 1967

Thanks to his intimacy with the artist, Peter is often caught in informal moments, less posed than is the case with other sitters. There are practical reasons for drawing people when they are asleep or otherwise unaware that they are being drawn: they will not become impatient or restless and with luck they will not even move. Moreover, they will be more relaxed and there will be no opportunity for them to ‘put on a face’ for the sake of a drawing. The picture will thus relate more successfully the artist’s view of that person rather than the sitter’s self-image.

No amount of intimacy, affection or informality, however, can save Hockney’s excursions into watercolour from outright failure or awkwardness at best. Having tried the medium in 1961 and again in Egypt two years later, Hockney returned to it on his tour of Italy and France with Peter and fellow-painter Patrick Procktor in 1967. Peter Having a Bath in Chartres [79] is one of the more successful watercolours, but even here he seems unable to control its flow properly or to give substance to the portrayal of mass without the assistance of a clearly defining line. Now that his handling of paint had changed to a thin application of colour contained within tightly drawn boundaries, the formlessness of watercolour must have been even less sympathetic to him. After this trip, he experimented with the medium only occasionally before 2002. Similarly, Hockney made a series of ink drawings of Peter in a very loose idiom reminiscent of his more subjective, almost caricatural drawings of the early 1960s. Hockney has kept these simply because he can see no reason, other than the exigencies of the art market, to throw them away, but he would not consider selling them or making them public because he regards them as failures. He has continued to this day to experiment with different styles and techniques in the full knowledge that many of the results will be unsatisfactory. It is a risk he is prepared to accept if he is to extend his range.

80 The Room, Tarzana, 1967

81 François Boucher Reclining Girl (Mademoiselle O’Murphy), 1751

Following Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool [71], Hockney did not use his friend again as the protagonist of a painting until the next year, for The Room, Tarzana [80]. The example of Boucher’s painting Reclining Girl (Mademoiselle O’Murphy) [81] has often been cited as a reference for the positioning of the figure, but the erotic charge of Hockney’s painting is equally the result of the contrast between the deliberately provocative pose and the otherwise antiseptic and impersonal interior. (The room was copied from a colour photograph of furniture which Hockney found in a local newspaper, an advertisement for Macy’s, which appealed to him for its formal simplicity and almost sculptural sense of volume.) The white socks and shirt emphasize the vulnerable nudity of the young man, while the cool blue atmosphere and dreamlike stillness complete the impression that a fantasy has been frozen in memory. If one is to speak here of Hockney’s relationship to other artists, the borrowing of a pose from Boucher is of minor significance by comparison with the example of painters who had systematically explored the psychological and emotional implications of a figure within an enclosed architectural setting. Vermeer, Balthus and Edward Hopper, though isolated in time and style from each other, all share this basic concern. Hopper’s etching Evening Wind, 1921 [82], provides a particular point of contact with its sensual image of a female nude in a room bathed in a strong unifying light. Now that Hockney was working in a naturalistic idiom and dealing with a more traditional conception of spatial continuity, he began to study the work of these painters with great interest in order to achieve in his own work a similar integration of figure with environment.

The Room, Tarzana [80] was accompanied in the same year by The Room, Manchester Street [83], a portrait of the artist Patrick Procktor in his London studio. Each depicts a close friend in an appropriate indoor setting, an enclosed space which defines the entire ambiance of the place and of its way of life. The Room, Manchester Street is one of Hockney’s rare pictures of London; England in general has provided little stimulus to his imagination. The light that emanates through the Venetian blinds of the two windows, a contre-jour effect to which Hockney returned on several occasions in later years, has a cool silvery quality appropriate to the greyness of England. The light in The Room, Tarzana, on the other hand, is clear and intense, casting crisply defined shadows across the interior.

The titles of these two pictures tell us nothing more than the location of the scene, real in one case and contrived in the other. Other captions at this time tell us the obvious, drily identifying an image which is already self-evident: A Table [84], A Lawn Being Sprinkled [87], A Bigger Splash [86]. Even in the explicit portraits such as American Collectors (Fred & Marcia Weisman) [57] we are given only the names of the people and occasionally a brief description of who they are, but what we wish to know about the complexities of their relationships must be deduced from the pictures themselves. It is right that the words should now emphasize the importance of choice in interpreting the visible world, since this is a fundamental theme of the paintings and perhaps the most vital influence on their construction.

83 The Room, Manchester Street, 1967

84 A Table, 1967

85 René Magritte Souvenir de Voyage III, 1951

Hockney recalls that the image of A Table [84], with its strong sculptural presence, was suggested by the similar emphasis on mass in The Room, Tarzana [80]. The frozen quality of the image, its dry dead-pan humour, the foreboding silence and the playfulness with which the illusion is revealed all suggest, however, that Hockney was beginning to look at the work of the Belgian Surrealist painter René Magritte. It recalls particularly Magritte’s pictures of tables and still lifes made of stone, such as Souvenir de Voyage III, 1951 [85], in which the disturbing quality of the image is called to our notice through the very blandness with which it is depicted. The objects on Hockney’s table, for all their simplicity, also seem charged with mystery, if only because they are isolated and presented to our gaze for contemplation. It is the very act of looking with such unaccustomed intensity that turns a prosaic scene into something like an apparition.

The immediate decorative impact of colour and design in Hockney’s work at this time belies the undercurrent of emptiness and silence that becomes more compulsive the longer one looks. There is something jarring about the apparent depopulation of Los Angeles, in which the only signs of movement come from mechanical objects such as lawn-sprinklers. Even A Bigger Splash [86] into the swimming pool betrays no sign of the diver. Unconsciously, perhaps, a sense of isolation emerges, not so much the sombre melancholia of Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical paintings as a feeling of aloneness as induced by Edward Hopper’s pictures of deserted American city streets.

There are many elements that contribute to the forcefulness of pictures such as A Lawn Being Sprinkled [87] and A Bigger Splash [86]: the wit in devising new signs for representing water, the strong sense of design and boldness of colour, and the playful way in which an observed scene has been used to construct an almost abstract painting. Yet it is the stillness of the images that lingers longest in the mind. Earlier painters, Vermeer being the most notable example, had occasionally contrived pictures which appeared to deny the passage of time. The advent of the photograph, particularly with the introduction of the high-speed camera, made it possible literally to capture an instant. The situation seized by a photographer is thus removed from our customary experience, which consists of a succession of events in relation to each other. Twentieth-century artists are in the position of being able to use the evidence provided by photography at the service of the slow and deliberate process of painting, in which a far greater degree of control is possible in selecting or exaggerating particular effects. While availing himself of the camera, Hockney takes advantage of the contrast between the mechanically produced and the hand-drawn image, playing on the precision of form and smoothness of surface that can be achieved with acrylic paints. As Hockney himself has pointed out, the congealed gesture of A Bigger Splash [86] arouses our interest because of the way in which an image captured instantaneously with the camera has been laboriously translated into paint. There are two time scales, that of the initial action and that of its restatement on canvas, and it is the interplay of the two that creates the peculiar intensity of the picture.

86 A Bigger Splash, 1967

87 A Lawn Being Sprinkled, 1967

Pictures such as A Bigger Splash are among the last in which Hockney continued to use a framing device round the image. He had begun to wonder whether the border was not merely a sign of timidity, a redundant element, and from 1968 he consistently investigated whether there was really any need to continue admonishing the viewer that what he is looking at is merely an artificial reconstruction of reality on a two-dimensional surface. As the framing device disappears, there emerges a greater attention to the portrayal of an illusionistic space through traditional perspective. There is no question of misleading the viewer, as everything is clearly calculated. The figures are shown in formal hieratic poses, with a preference for straight frontal and profile views, as in the paintings of Piero della Francesca, which he was studying closely. The architecture as well as the objects within it are disposed on perspective grids as highly defined as those of another fifteenth-century Italian painter, Paolo Uccello. We are left in no doubt about the artist’s control in composing the picture.

Hockney’s first purchase of a ‘good camera’ in 1967, a 35 mm Pentax, made a great impact on the shift of his interests during that year. The Polaroids he had used previously were casual snapshots, helpful as aide-mémoires but ultimately rather limited and inflexible. The 35 mm camera allowed him greater subtlety of lighting, focus and format, and he now began to take photographs much more seriously, sometimes taking dozens of shots in planning a particular picture. The camera also renewed his interest in traditional pictorial devices for the representation of space, with the result that his pictures begin to open out and to deal as much with the illusion of depth as with the surface of the canvas. Hockney recalls that he realized that to paint convincing figures, he had to deal with volume, and this led him to reject Modernism’s insistence on flatness. His own lingering fears that he might be retreating from the art of his own time still find reassurance in Picasso’s apparent about-face from Cubism to a personal form of Neo-Classicism in the 1920s:

‘You know perfectly well that wonderful art has been made within these old conventions. When conventions are old, there’s quite a good reason, it’s not arbitrary. So Picasso discovered that, as it were, and I’m sure that for him that was probably almost as exciting as discovering Cubism, rediscovering conventions of ordinary appearance, one-point perspective or something. The purists think you’re going backwards, but I know you’d go forward. Future art that is based on appearances won’t look like the art that’s gone before. Even revivals of a period are not the same. The Renaissance is not the same as ancient Greece; the Gothic Revival is not the same as Gothic. It might look like that at first, but you can tell it’s not. The way we see things is constantly changing. At the moment the way we see things has been left a lot to the camera. That shouldn’t necessarily be.’

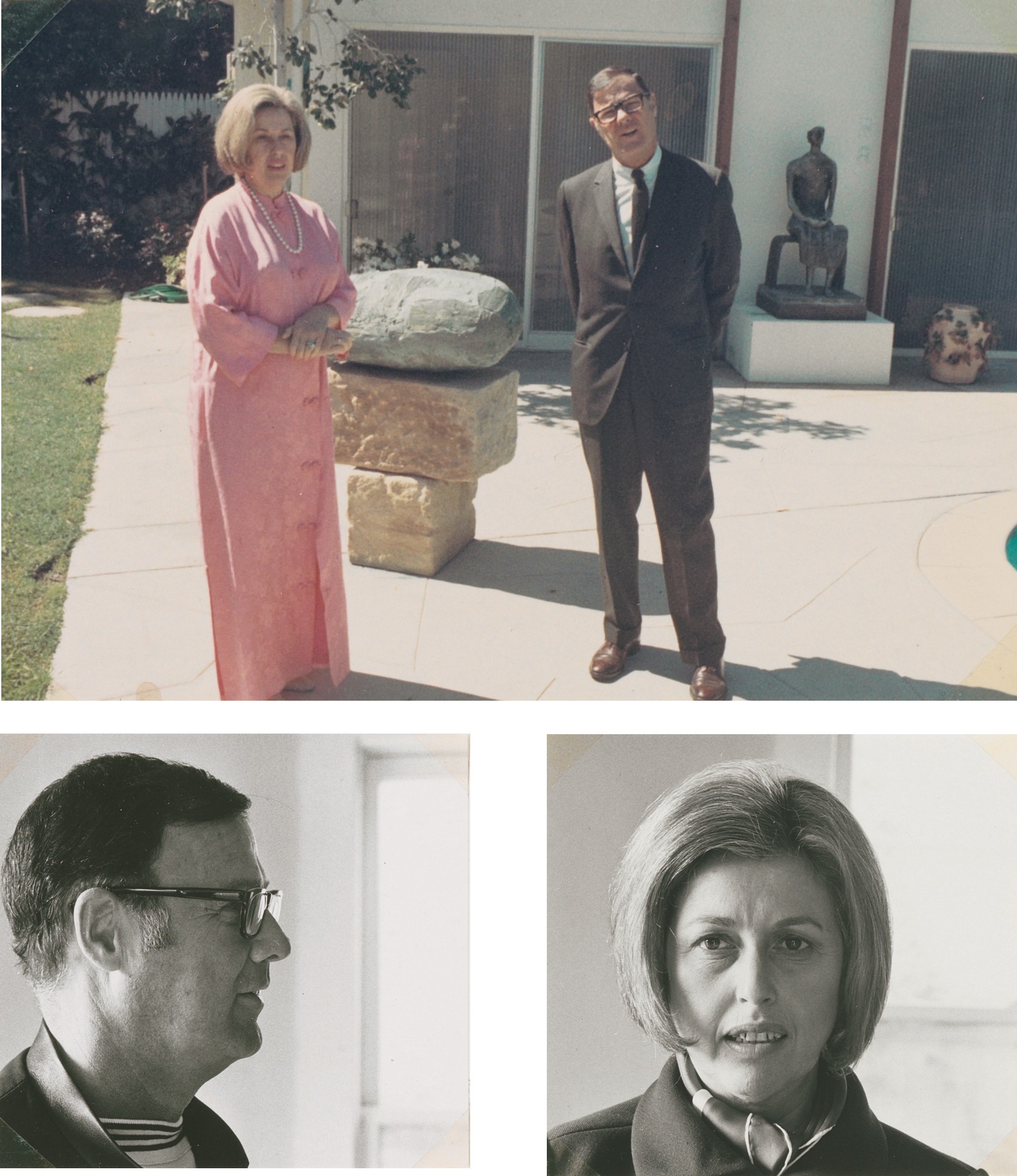

The theme of intimate relationships between people is one that had concerned Hockney since the early 1960s, but it was only now that he had devised a more naturalistic framework for his pictures that he was able to treat the subject in terms of the subtleties of particular friendships. American Collectors (Fred & Marcia Weisman) [57] and Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy [89], both painted in 1968, initiated a series of double portraits that was to occupy Hockney for the next seven years, and which still survives as a subject in his current work in a modified form. Only on one occasion, for the Portrait of Sir David Webster, 1971, has Hockney allowed himself to be persuaded to paint a portrait on commission. The double portraits are all of close friends of the artist, and they are invariably emotionally attached to each other as friends, lovers and married couples. Each picture in the series measures seven by ten feet, a size which corresponds to that of a wall in a small room. This establishes an immediacy of contact between the spectator and the people portrayed, since the continuity of our space and scale into the picture invites us to be participants as well as witnesses to an essentially private event. Each scene is set in the home of the people depicted, and the objects and environment that surround them are as much a part of the portrait as the capturing of their likenesses. They are ‘domestic scenes’ in a much fuller sense than the canvases for which that phrase was devised in 1963.

88 Fred and Marcia Weisman, Beverly Hills, 1968

89 Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, 1968

Photographic studies taken by Hockney were used heavily for reference for all the major double portraits [88, 90, 91], although in most cases the camera was used primarily as a guide in setting up the composition, and details, particularly of the figures, were painted directly from life. The portrait of the Weismans, however, was painted entirely in the studio with the aid of a group of colour and black and white photographs [88]. One such colour photo established the basic format – it is not by accident that the proportions of these double portraits are approximately the same as those of photographs produced with a 35 mm camera – as well as a number of the details and even the colour scheme for the painting. Further details of objects such as the totem-pole provide more information, and the faces are painted from two black and white close-ups of the collector and his wife. Although Hockney has felt free to stylize the representation of certain areas, such as the light glancing off the windows, and to effect changes in the placement of the objects, he has otherwise imposed himself little on the scene as described by the camera.

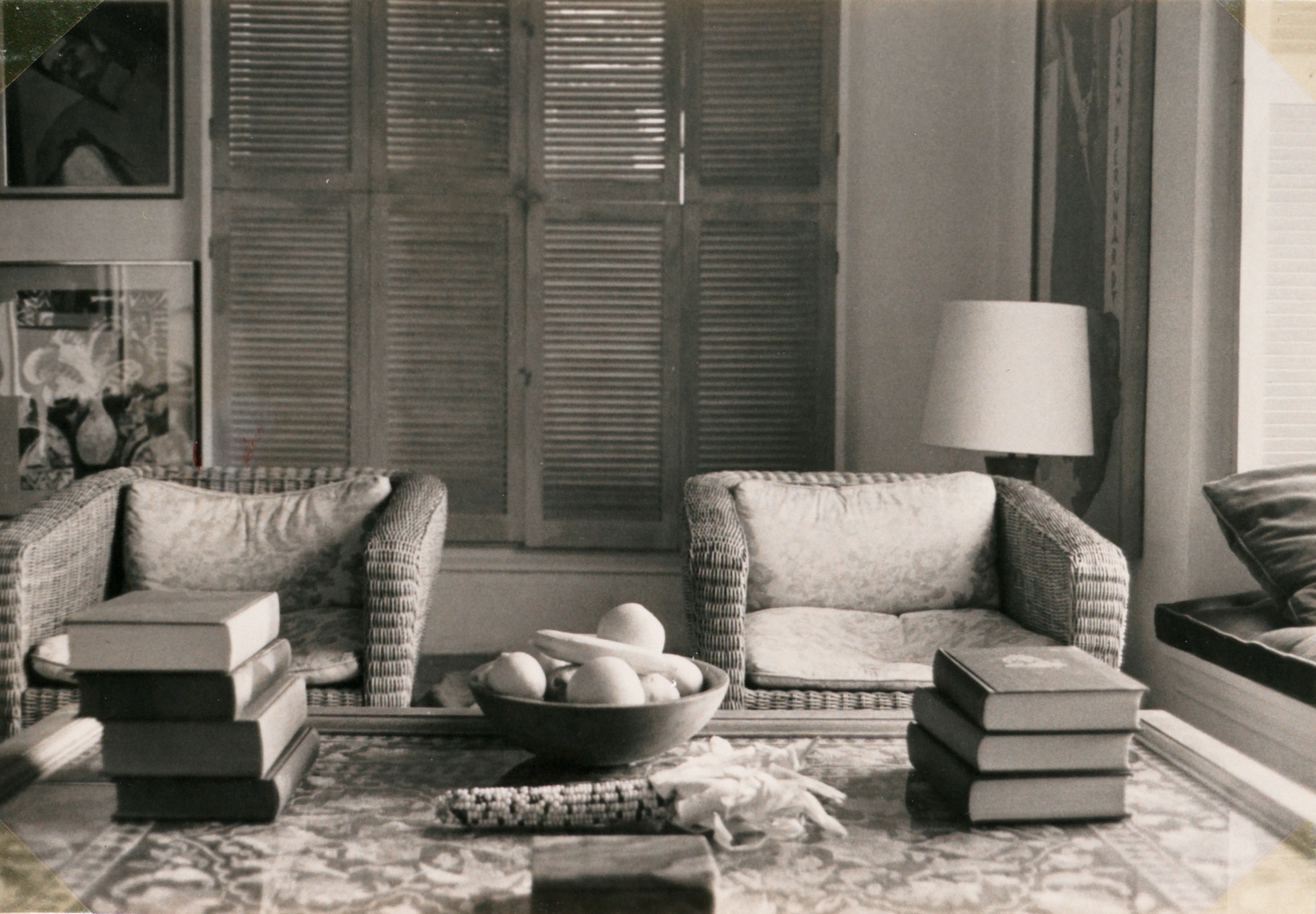

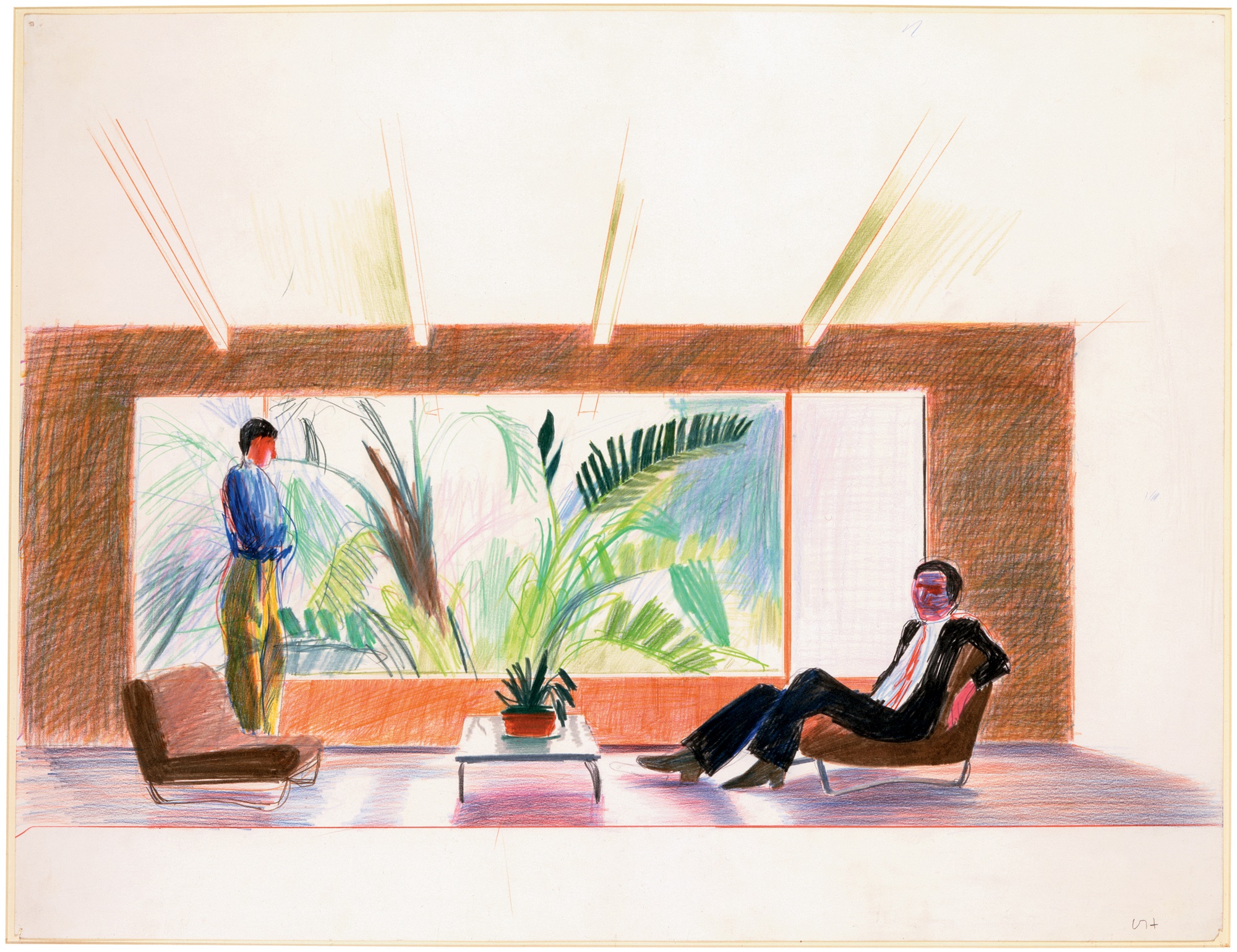

An even larger number of photographs was shot for the portrait of the writer Christopher Isherwood, a close friend of Hockney’s since 1964, and his companion, the artist Don Bachardy [89]. Hockney amassed as much information as he could in preparing the picture because it was his intention ‘to depict them, the way they lived and everything’, but as much as possible of the actual painting was done from life in Isherwood’s own living-room [91]. Before setting to work on the canvas he also made at least one watercolour study and two pencil drawings to work out the composition and determine the most effective poses. In the final picture Isherwood is seen shooting a piercing glance across to Bachardy, who in turn looks straight out at the spectator, establishing a triangular relationship. Through this orchestration of pose and expression, as well as by means of the bilateral division of the canvas round a vertical axis, Hockney alludes to the bonds uniting the two men as well as to their separateness, their need for a degree of independence.

In each of the double portraits the sitters are conscious of each other’s presence, yet they are also apart. Mr and Mrs Weisman, for instance, look resolutely in different directions, each enclosed in his or her own thoughts. The picture of Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott [92–94] has been compared to traditional Annunciation scenes, in which the peace of one person is suddenly interrupted by the intrusion of another. The sense of struggle between the impulse to connect with another human being and the need to remain separate, already implicit in the Cavafy illustrations, is now treated with greater directness. These observations of human nature are achieved through purely pictorial means, both through the gestures of the participants and by means of the formal division of the architectural settings into compartments or separate spaces.

90 Christopher Isherwood, March 1968

91 Santa Monica, 1968

92 Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott, 1969

93 Henry Geldzahler, 1968

94 Christopher Scott, 1968

The Geldzahler and Scott picture is divided into three vertical panels of approximately equal width which provide separate enclosures for the two figures. The triptych format is a characteristic of the traditional altarpiece, strengthening the analogy to the Annunciation and leading one to view the frontally seated man as a transformation of the standard icon of the Madonna enthroned. This might be an over-interpretation of Hockney’s thoughts at the time, but he is willing to accept such overtones because ‘slightly unconsciously, there are many things you think about when you’re making a picture’. On one level, this is after all a private devotional picture, an image of the commitment of two men to each other. Geldzahler also has a public role, however, as an influential museum curator and a leading figure in the American art world, and the picture thus also relates to the tradition of the society portrait. There are echoes, in fact, of a particularly famous precedent, the early nineteenth-century portrait of Madame Récamier by Jacques-Louis David [95]. It may be that Hockney was not mindful of the connection when he selected the sofa and the elegant lamp as the essential props, but this does not affect the resonance which the picture holds as a transformation of a familiar image of an earlier taste-maker. Geldzahler’s sense of purpose as a promoter of contemporary art takes on an almost aggressive air if we contrast his unflinching gaze and forthright frontal posture with the reticence of Madame Récamier’s reclining pose. We know from Geldzahler’s own account that even though the picture seems perfectly plausible as the record of a particular place at a precise moment, the artist has in fact added objects that were not originally there and substituted another view through the window. The painting is indeed a composite, but as a self-sufficient image it needs no justification.

95 Jacques-Louis David Madame Récamier, 1800

An unpublished pencil drawing, depicting Peter sitting cross-legged on a sofa with Hockney walking towards him in profile from the right, appears to be the only extant evidence of a self-portrait with his boyfriend contemplated by Hockney but never brought to fruition. Hockney says simply that, as with many of his other plans, he ‘never got “round to it”,’ but he acknowledges that the scarcity of self-portraits in his work as a whole may be due to a reluctance to examine himself too closely. ‘I admit I avoid some things about myself, as I avoid some things about life,’ he says, adding however, ‘I think my work develops slowly. It takes me a long time to find out things, and of course I do believe my work will get better, richer. I also assume that in the end I’ll deal with things that I avoided when I was younger, partly because you will face them more anyway.… I’m assuming I will come to self-portraits. Partly I’m aware that in the past there was a certain innocence of vision and is there still at times, but I’m also aware that perhaps it can’t go on, might not go on. It’s not going to change quickly. If you don’t know how to deal with it, you put it aside, and anyway it will force itself in the end. I think if I looked at myself carefully, it would probably be the end of that innocent vision. Maybe therefore I should do it.’

96 Swimming Pool, Le Nid du Duc, October 1968

Hockney filled five large photograph albums between September 1967, when he first started using his new camera, and February 1969. Of the thousand or so images that these contain, only a few suggested possibilities for paintings. Certain photographs, such as Swimming Pool, Le Nid du Duc [96] and others of the same series taken in October 1968, seemed complete in themselves without the need for further elaboration. His growing experience with the medium was changing his appreciation of it and directing him to emphasize the formal qualities of the images as seen through the lens. This photo and others of equally bold and simple design satisfied Hockney’s persistent urge towards abstraction, and in a sense left him free to emphasize the central role of depiction in his paintings.

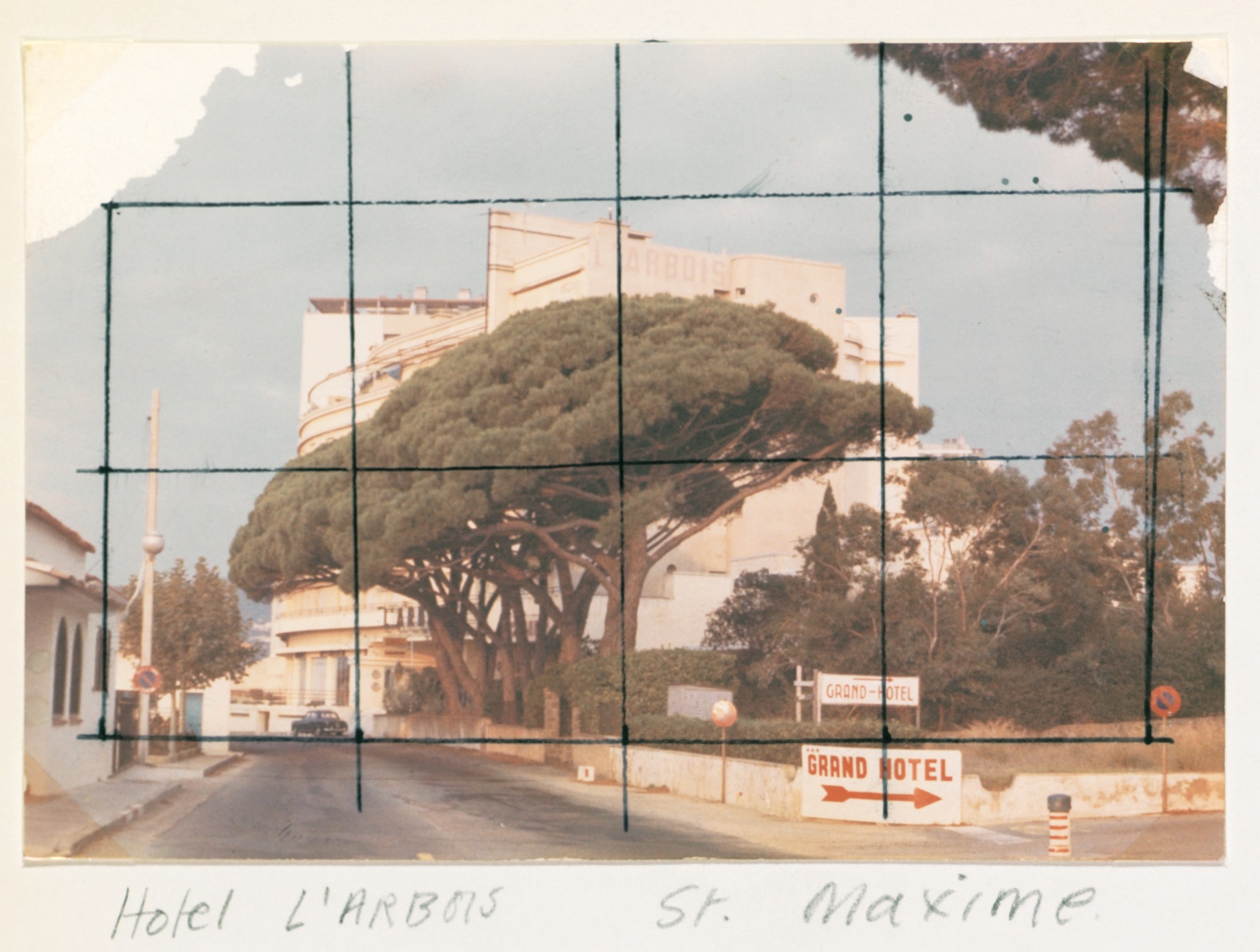

Fascinated by the technical possibilities offered by the camera, Hockney did allow himself for a moment to be seduced by what he discovered with it. Two paintings executed over the winter of 1968–69 transfer with little alteration photographs he had taken at Sainte-Maxime in October 1968. One of these canvases, L’Arbois, Sainte-Maxime [97], simplifies to a great degree the information provided by the squared-up photograph [98], eliminating certain details such as the wording on the signs and the car on the street, but otherwise transfers the image intact in a way that was not true in his earlier work. The other painting, Early Morning, Sainte-Maxime [99], displays an even more slavish reliance on what was in any case a rather gushingly pretty photograph of a garish sunset. Hockney now regards this as his worst painting. He was by this time aware of the new movement known as Photo-Realism – his meeting with the painter Malcolm Morley at a party in June 1969 is recorded in a photograph – but he soon realized that he saw no purpose in fashioning a virtual reproduction of a photograph in paint. ‘It seemed pointless doing that, because then the subject is not really the water or whatever, it becomes the fraction of a second you’re looking at it. This is the problem with photography for me, really, it’s obviously its inherent weakness. A photograph cannot really have layers of time in it in the way a painting can, which is why drawn and painted portraits are much more interesting. It’s a problem I still keep thinking about. Sometimes I think photography isn’t really much at all, and people have got it all wrong.’

97 L’Arbois, Sainte-Maxime, 1968

98 Hotel L’Arbois, Sainte-Maxime, October 1968

99 Early Morning, Sainte-Maxime, 1968

As a reprieve from the excesses of naturalism, Hockney turned to a project which he had been thinking about since the early 1960s, a set of etchings – Illustrations for Six Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm [100–02]. He had made two prints of Rumpelstiltskin in 1961 and 1962, but only now decided that he was ready to produce a full set of illustrations. After reading the more than two hundred Grimm’s fairy tales, he settled on twelve, some of them obscure since it was the vividness of the imagery which attracted him, and began making preliminary drawings as well as etching directly on to the plates. He soon realized that six tales would produce enough illustrations for the volume and stopped there, with a plan for producing a further volume at a later date; at the moment he has no intention of going back to this, as he is involved with projects which now interest him more, but it remains a possibility. Even in its curtailed state, the project took up more than a year of his time, from his trip on the Rhine in September 1968 to collect suitable architectural details to the etching of the plates in London between May and November 1969. They were published in 1970.

The Grimm series brought Hockney much closer to the characteristics of his earlier work. The deliberately conventional, even archaic, techniques which he employed here, such as cross-hatching, were a refreshing change from the extremes of naturalism in his most recent paintings. His very delight in etching as a medium, and its requirements in simplifying the imagery in terms of one colour and line alone, saved him from the excesses to which he was disposed when working on canvas.

‘Naturalism was never as much of a problem in my graphic work, because to me graphic work is about marks, part of its beauty is the marks, whereas I’d gotten to the point where I didn’t seem to care about the painted mark that much. You then go into the depiction of nature very realistically, with light and everything, but I don’t think it ever really occurred in the graphic work at all. I think in that sense there was more consistency in it. Somehow I’ve been a lot freer in the graphic work than in the painting. Somehow a kind of painting block took over. Probably in the end acrylic paint did it, the burdens of it, whereas I think in everything else, in the graphic work, there is a delight in the medium itself, etching or lithography. The joy in the medium gives you joy, often, in spirit in the thing.’

Hockney’s imagination was stimulated, moreover, by the return to a literary source; the last time he had worked in this way was for his last major print series, the Cavafy illustrations, three years earlier [62, 63]. Fairy tales are collaborative efforts in the sense that they are passed on from person to person and modified in the course of retelling. Hockney’s prints rely on similar transformations of images and techniques devised by others, stressing the continuity of pictorial rather than oral traditions. The enchantress in the Rapunzel story [100], for instance, is pictured in the pose of a Virgin and Child by Bosch, though severely deformed by age and ugliness. It is not especially important to detect the source in Bosch’s Prado Epiphany, but it is vital to recognize the blackly humorous mutation of the Virgin and Child theme, for in the identification of the enchantress as a virgin lies Hockney’s interpretation of the story: the woman is so ugly that no one would have sex with her, and that is why she demands her neighbours’ child for herself.

Hockney chose to illustrate the stories not in the usual terms of dramatic narrative but rather as a succession of memorable static images. To achieve this end, he has freely borrowed from the work of other artists. In order to depict the sexton standing perfectly still in front of ‘The boy who left home to learn fear’, he plays humorously on a literal interpretation of the phrase ‘stood still as a stone’ [101]. Taking his cue from Magritte’s paintings of objects made of rock-like surfaces [85], Hockney has devised a striking image in the form of a visual pun. He has recourse to Magritte also for the story of Rumpelstiltschen, conveying the enormity of the task demanded of the miller’s daughter by adapting the unnerving dislocations of scale from certain paintings by the Surrealist to the picture of A Room Full of Straw.

100 The Enchantress with the Baby Rapunzel from Illustrations for Six Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm, 1969

101 The Sexton Disguised as a Ghost Stood Still as Stone from Illustrations for Six Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm, 1969

The imagery in other prints from the set draws on the work of artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Paolo Uccello and Carpaccio, but it is in terms of technique, as well, that Hockney has recourse to previous solutions. He recognizes that the range of marks that can be made within a particular medium forms a kind of visual language, and that each artist who has conceived or perfected a particular technique can be said to have enriched the vocabulary and extended the range of expression of that language. Hockney borrows from other artists not because he is lacking in imagination or because he wishes to impress us with his knowledge, but as a means of controlling the ‘emotional’ content by expressing it in the most vivid and economical form possible. How better to project a sense of the irrational than through Goya’s dense and dramatic aquatint, or to achieve a contemplative stillness than by way of Morandi’s restrained and delicate cross-hatchings? By seizing in this way any technique that he deems suitable to his purposes, Hockney pays tribute to all his predecessors who have made a contribution to the medium.

In view of the length of time alone that he spent on the Grimm etchings, Hockney is right to consider them one of his major works. Certainly the series contains some of his most memorable and poetic inventions, and as a contemporary illustrated book it is virtually without rival. Ironically, though, it is the very elements which provide much of the aesthetic and intellectual pleasure of the prints, the insistence on beauty and the constant references to the work of other artists, which also make one conscious of the artist’s limitations. There is no real sense of unbridled horror. Hockney’s characteristic detachment furnishes considerable humour and insight into the underlying themes of the stories, but fails to convey their more tragic or morbid aspect. Like ‘The boy who left home to learn fear’ in one of the lesser-known tales chosen for illustration, Hockney seems fundamentally incapable of producing a genuine shudder.

102 The Pot Boiling from Illustrations for Six Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm, 1969

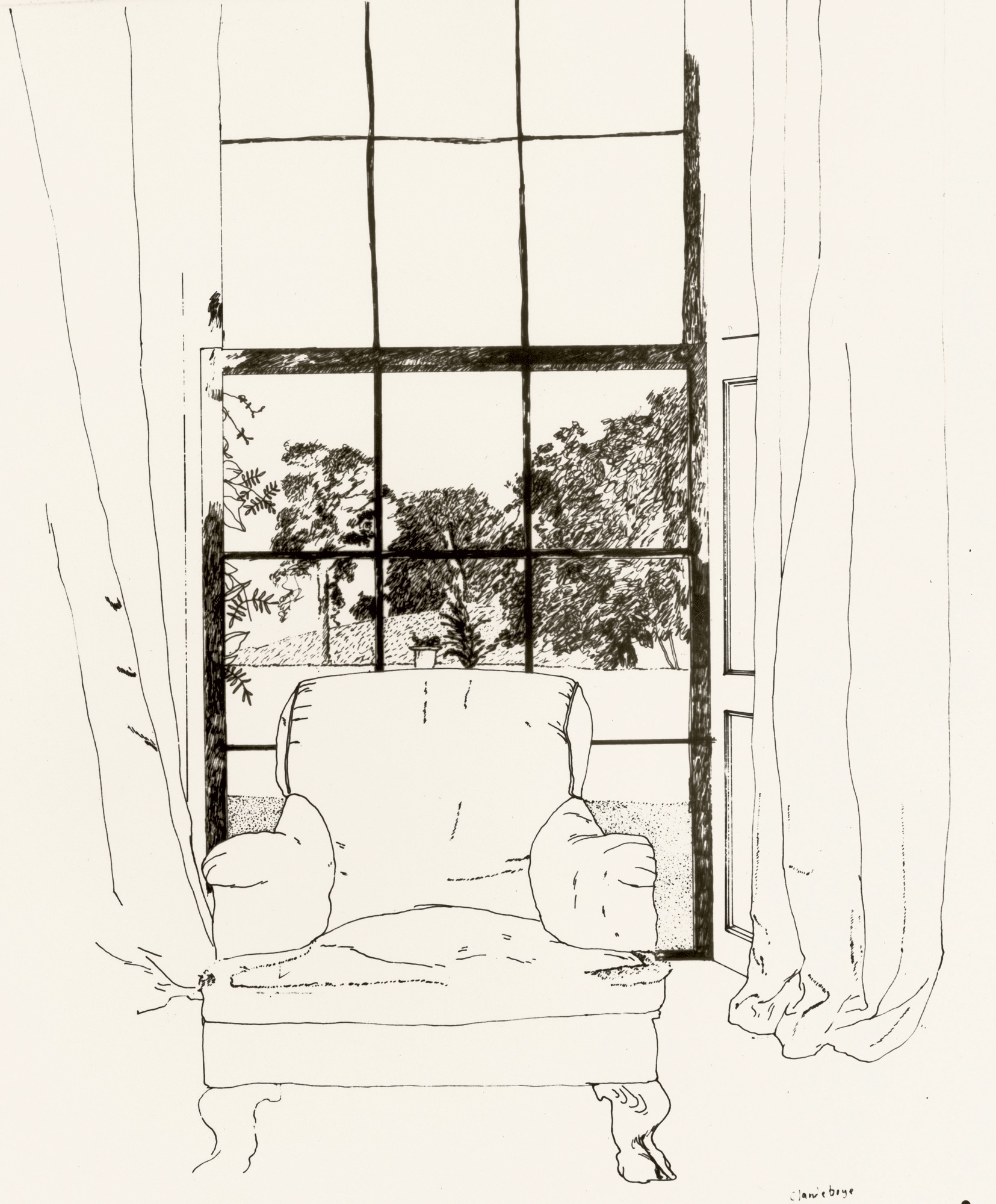

A number of the fairy tales stress the magical qualities of objects in themselves, a notion which Hockney demonstrates in the prints by presenting isolated articles detached from their surroundings: the rose, the tower and the pot in ‘Fundevogel’ [102], the lathe in ‘The boy who left home to learn fear’, the piles of straw and gold in ‘Rumpelstiltschen’. Armchair, 1969 [103], one of the few precise line drawings made in preparation for the series, carries the symbolic function even further. Copied on to the first plate for ‘The boy who left home to learn fear’, where it is titled Home, it represents the departure of the younger son from the security of his own environment. The chair is explicitly a stand-in for the figure: the image is presented in the guise of a formal portrait, and the dented cushions reveal that it is only moments since the chair has been vacated. The motif of the chair was soon to become a favourite human metaphor in Hockney’s work [108, 118], but in the context of the Grimm illustrations each of the separate images claims our attention with equal force as we read through the text and thus takes on a powerful talismanic quality. The implication is that the real source of magic in figurative art lies not within the object but as the result of the act of picturing itself.

Just as naturalism ceased to be an issue in the Grimm illustrations, so in the prints that followed Hockney was able to avoid the problems of excessive fidelity to appearances that plagued his paintings at this time. Peter [104], a three-foot-high etching of a complete figure, uses a high vantage point and two sets of perspective, one for the lower half of the body and the other to describe the figure from the waist up. Seen from above, the legs appear truncated by the effects of foreshortening. The torso, on the other hand, is viewed at a lesser angle and the head is seen from straight across.

The proportions of the figure, though somewhat startling if interpreted in naturalistic terms, correspond to our experience of looking at someone standing near us, as if we had started by looking at the ground and then slowly turned our gaze upwards towards the man’s face. The picture is thus analogue and metaphor of the artist’s act of scrutinizing another human being.

103 Armchair, 1969

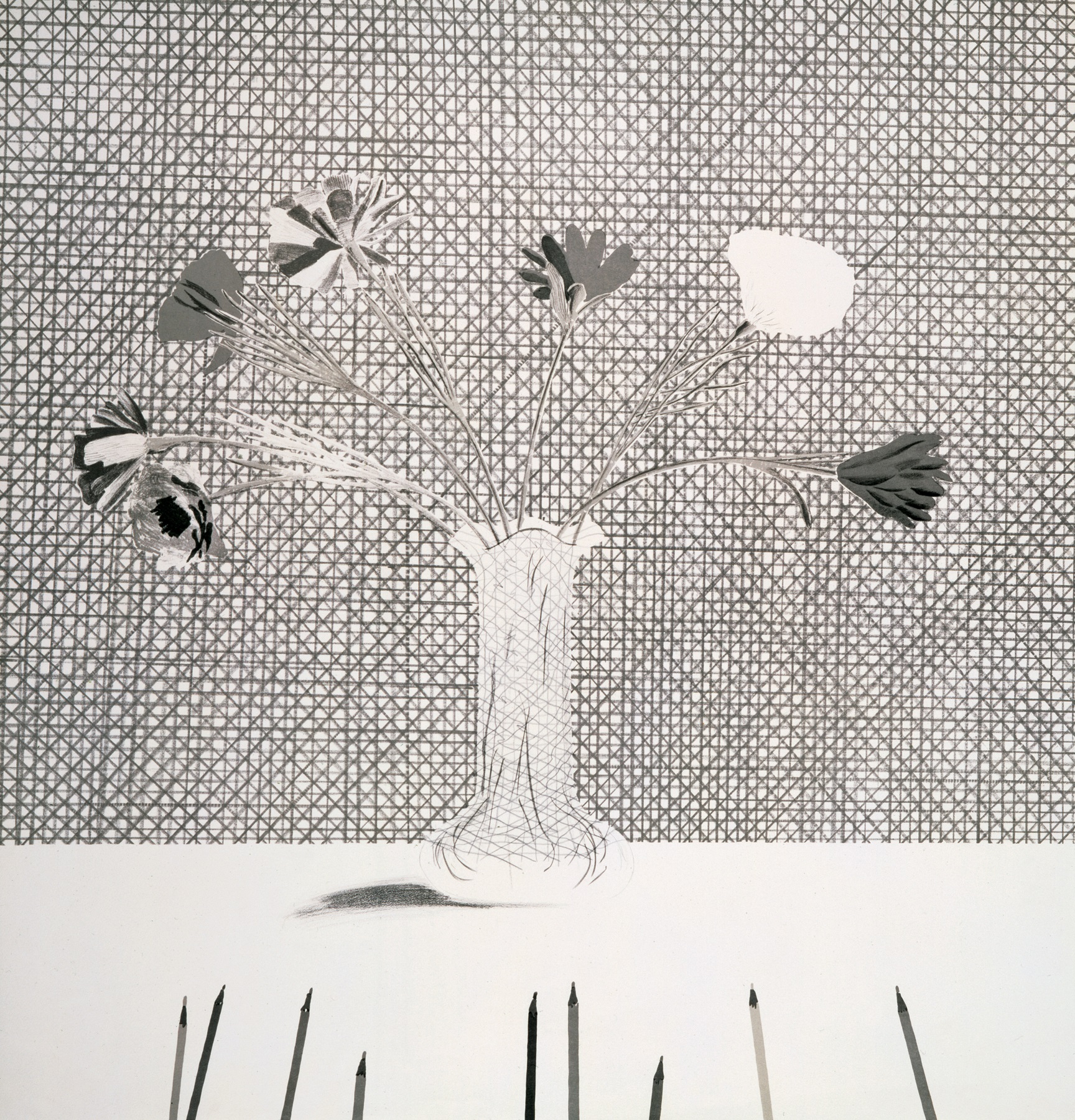

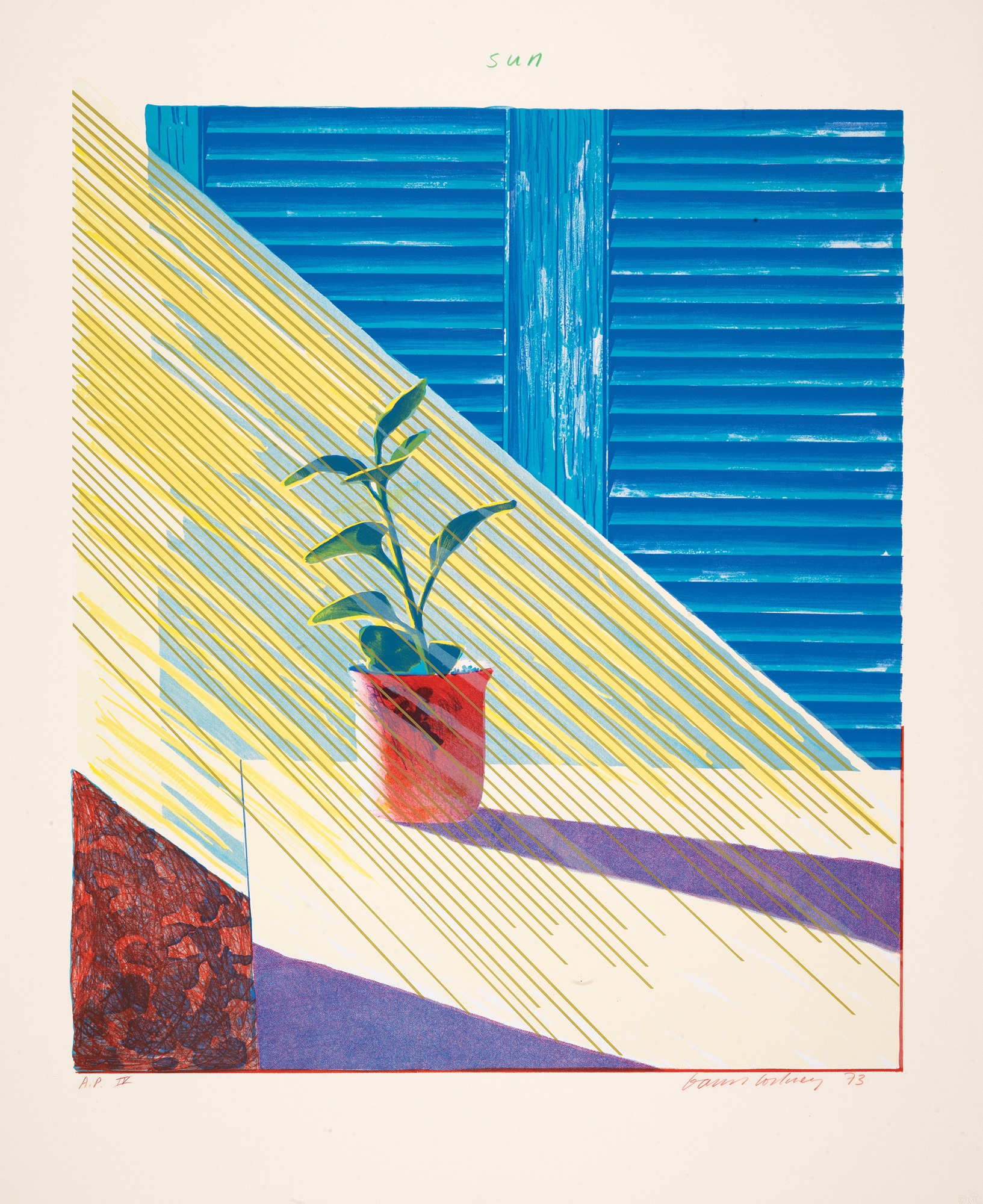

Flowers Made of Paper and Black Ink [105], a companion to Coloured Flowers Made of Paper and Ink which is printed from the same set of ten lithographic plates, acknowledges with a similar sense of purpose the artifice by which the image is composed. The title and the image both allude to the process of constructing the picture. The pencils on the table are not only his drawing tools but also the key to the superimposition of ten printings; this is especially obvious in the colour version, in which the image is colour-coded to the pencils. In laying out these drawing instruments in the immediate foreground, cropped by the edge of the picture, Hockney symbolically sets his tools before us, implying that in studying the picture we become surrogate artists ourselves. For the background he has used the cross-hatching technique that he had favoured in the Grimm etchings, transposing it to a medium where it is redundant as a means of shading. Hockney clearly enjoys the decorative pattern of lines for its own sake, regardless of its necessity for technical reasons. His delight in ornamental beauty and in the old-fashioned theme of simple still life is almost in conscious defiance of current practice. In an era which has prized rigorousness, austerity and grandness of intention, Hockney has not been afraid to court accusations that his work is lightweight. One lithograph of 1969 is actually titled Pretty Tulips, not in irony but as a simple celebration of beauty.

104 Peter, 1969

105 Flowers Made of Paper and Black Ink, 1971

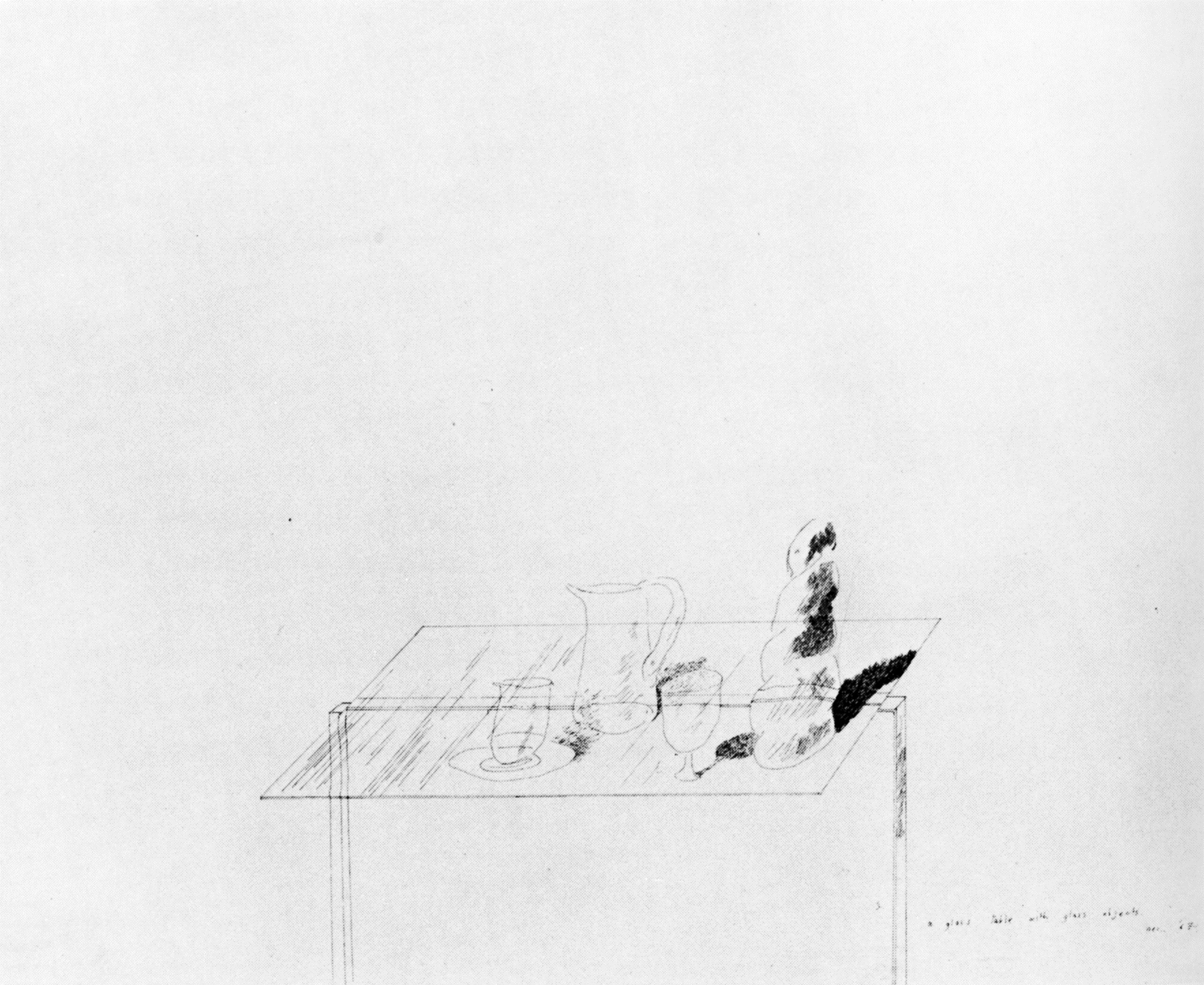

Still Life with T.V. [106], one of a very small number of paintings completed in 1969, treats the still life theme in terms of wholly contemporary imagery. The heightened presence of the objects in this and the paintings that followed, a strong consciousness of the human use and connotations of inanimate things, seems to owe much to the experience of the Grimm etchings. Equally important, however, is his concern with the specific delineation of each detail, by comparison for instance with A Table [84] painted only two years earlier. A photograph of the objects arranged on the furniture, taken by Hockney simply as a record rather than as a working aid, reveals the extent to which he has simplified and altered the evidence, ignoring a framed print on the wall and reducing the complicated play of shadows so that they gain in force. Implicit in the imagery itself is an assertion of drawing, an emphasis on the artist’s hand, over mechanically produced images; the television screen here, as in the 1968 crayon drawing Sony TV, is blank, and all the imagery is created round it.

106 Still Life with T.V., 1969

Hockney recalled in an interview with Charles Ingham in 1979 that all the objects in Still Life with T.V. were ‘food for thought’ while working: ‘I used to watch TV sometimes making paintings. … And there’s the paper here waiting to be drawn on. And there’s food to keep you going, this little sausage is literally food, and there’s some other food here for the mind, a dictionary, full of words.’ He acknowledges, however, that within the cool presentation there is an emotionally charged atmosphere, and that the painting might carry further meanings of which he was not conscious at the time. The inexpressively uniform surface of acrylic paint by its very blandness intensifies the unease caused by the violent foreshortening, an exaggerated perspective which is anchored to the picture plane by means of a device, favoured by Cézanne as well as by the Cubists, of a drawer placed frontally along the lower edge of the picture.

Where Hockney in his earlier work had used devices as subjects in themselves, he uses such mechanisms in his naturalistic pictures to support the theme and construction of the image. Le Parc des Sources, Vichy, 1970 [107], for instance, is not simply concerned with the false perspective which so intrigued him at this French spa, in which two rows of trees are planted in the form of a triangle to increase the impression of distance. Certainly it was direct observation that triggered him off, and he made much use, for the colour as well as for the composition, of a series of photographs he took on site in September 1969. He was struck, however, by the sense of the landscape as a picture within the picture, a favourite theme which he now realized he could deal with in the context of naturalism simply by finding the right subject. The seated figures, Ossie Clark and Peter Schlesinger, witness the view as a theatrical or cinematic spectacle, while the artist has vacated the third chair so as to contemplate the entire scene and produce his picture of it.

Merely by depicting what is there, choosing his vantage point but inventing nothing, Hockney has created a picture about illusion which by his own admission has ‘strong surrealist overtones’. It could almost be described as a ‘found’ Magritte. The implications of the picture’s form, however, could be taken even further, for if it is a construction of triangles it concerns also a romantic triangle in which Hockney and his two friends are the participants. Although he was only vaguely aware of it then, the first strains in his relationship with Peter were beginning to show, and this emotional tension, teamed with the false perspective, produces a sense of unease and insecurity.

107 Le Parc des Sources, Vichy, 1970

A further variation on the theme of the picture within a picture occurs in Three Chairs with a Section of a Picasso Mural, 1970 [108], which is based on photographs taken in March of that year at the Château de Castille, the home of the art historian Douglas Cooper. Hockney has remained faithful to one particular photograph of the mural, which is painted on the wall of a covered outdoor patio, but he has removed part of the foreground as well as the crazy-paving pattern of the floor. More important, he has transferred the date ‘1.11.62’ from another photograph of a separate part of the mural, tampering with the evidence provided by the camera in order to call attention to the fact that this is a re-creation of a picture by someone else. Picasso was beginning to interest Hockney much more again. The mural in Hockney’s picture is an example of the fluency and dexterity of the drawing technique for which Picasso was renowned. The apparent ease of Hockney’s transcription makes it a particularly cheeky form of homage.

108 Three Chairs with a Section of a Picasso Mural, 1970

In the spring of 1970 Hockney began work on a painting he had been planning since the previous year, a double portrait of the recently married fashion designers Ossie Clark and Celia Birtwell [109]. In addition to making some drawings as early as 1969, he took more photographs for this painting than for any of his previous works, both in colour and in black and white. The figures were painted largely from life, but the large size of the canvas made it necessary to do this work in his studio rather than in the home of the sitters. The photographs thus occupy a particularly important role here in providing information, not only in terms of the architectural setting but more significantly for the colour scheme. Along with The Room, Manchester Street, 1967 [83], this is the only explicit picture of London that Hockney has painted, and it was thus of the utmost importance to capture the muted, veiled quality of the light streaming in through the window. Hockney’s own description of the genesis of this picture makes it clear that it was precisely this problem of light, in particular the contre-jour effect from the centre, which was his main concern. So dominant is this aspect, in fact, that it is only on closer inspection that one realizes how little he actually concerns himself with detail other than in the description of the figures and a small number of objects. Large areas, notably of the walls and the carpet, are treated simply as abstract surfaces and patterns of colour. Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy [109] is not, therefore, the slave to naturalism that it might appear; not only has Hockney put the picture together from different sources, but he has also felt free to move these elements around and even to invent large sections of the surface in order to ensure the aesthetic self-sufficiency of the picture.