(Pastinaca sativa)

10 row feet per person

‘Lancer’ and ‘Andover’

Place in cold storage or freeze

One of the most vigorous root crops you can grow, parsnips will also keep through winter in the refrigerator, in a cold root cellar, or in the garden. More gardeners should grow these sturdy plants, which grow easily once the seedlings are up and going. Parsnip seeds are reluctant germinators, so the hardest part of growing a good crop is getting a good stand of seedlings. Pre-germinating seeds indoors helps to solve this problem.

Cooked parsnips have a unique creamy texture that makes them a natural addition to mashed potatoes or hummus, and there are endless variations on parsnip soup. White beans combine well in a savory parsnip soup, or you can try pear-parsnip soup made smooth with an immersion blender. Use a ribbon-type vegetable peeler to cut thick strips from large parsnips, then oil, lightly season, and bake into parsnip “bacon.” It is best to precook parsnips destined for the grill.

In my experience there is little difference between parsnip varieties, so I suggest working with an open-pollinated variety like ‘Lancer’ or ‘Andover’, which allows the possibility of saving your own seeds. Parsnip plants that have been well chilled in winter will bloom and set seed in June, with the seeds ready to harvest in late July. If you don’t save your own seeds, plan to buy a fresh supply every year.

Parsnips can be forgotten in the refrigerator for weeks at a time, which is part of their allure. Allow about 10 row feet per person, which should yield 6 to 8 pounds. Grow more if you want to try overwintering parsnips to dig first thing in spring.

When: With slow-sprouting parsnip seeds, it’s helpful to do everything you can to support the germination process, starting with warm soil. Wait until the soil has lost its chill and the weather has settled to plant parsnips, usually around the time of your last spring frost date. You can wait later if you like, but don’t start early and don’t try transplanting parsnips. In midsummer, look for a period of cool rainy weather for planting a second crop of parsnips to harvest in late fall or leave in the ground through winter.

Pre-germinating: Begin pre-germinating the seeds 5 to 7 days before you plan to plant them. Place the seeds in a clean jar, swish them gently in lukewarm water for a few minutes, and then pour into a strainer lined with a paper towel. After the excess water drips away, place the damp towel with seeds in a food-grade container, with the lid left slightly open. Keep the container at room temperature, and check daily to make sure the seeds are nicely moist. On the fifth day, look for tiny curled “tails” emerging from the seeds. When one-third of the seeds make this much progress toward germination, plant them immediately in prepared beds.

It’s time to plant pre-germinated parsnip seeds when one-third of the seeds have grown tails. You may not see seedlings for another week.

Planting: Thoroughly cultivate beds to be planted with parsnips, removing rocks and other obstructions while mixing in a generous 2-inch layer of rich compost, or compost amended with organic fertilizer. Plant pre-germinated parsnip seeds in straight rows at least 10 inches apart, spacing seeds about 1 inch apart. Even pre-germinated parsnip seeds can be slow to emerge, so it helps to reduce weed competition by covering the seeds with weed-free potting soil. After the seedlings are up and growing, thin them to at least 4 inches apart. Parsnips are big, robust plants that need ample space if they are to grow big roots.

Parsnips have few problems with pests, though the roots are eagerly eaten by voles. Misshapen parsnips can be caused by any disturbance to the roots, which is why parsnips are always direct-seeded and never transplanted.

When: When older leaves begin to yellow and fail, dig a sample root to see if it has attained good size. Keep in mind that garden-grown parsnips may be larger than what you see in stores, but this is good!

Parsnips that mature in cool fall soil can be left in the ground longer, but they should be dug before the ground freezes. Leave a few plants in the ground to overwinter, and dig them first thing in spring, as soon as the little tops start to grow. If you want to save your own parsnip seeds, allow two or three overwintered plants to bolt, bloom, and produce a fresh crop of seeds.

How: Before pulling parsnips, use a digging fork to loosen the soil just outside the row. Rinse harvested parsnips with cool water, or gently hand-wash them to remove clods of soil. Use a sharp knife to cut off the parsnip tops. Pat the parsnips dry with clean towels and store in plastic bags in the refrigerator or a cold root cellar, packed in damp sand or peat moss. Wait until just before using your parsnips to scrub them clean.

Parsnips will store for months in the refrigerator or in very cold storage in a root cellar or unheated basement. As long as temperatures are kept constantly cool, ideally around 40°F (4°C), parsnips packed in damp sand or sawdust will keep very well.

Use your refrigerated or cold-stored parsnips as needed in the kitchen. Should a planting have issues from root-tunneling insects that render the roots unworthy of long-term refrigeration, peel, cook, and purée the parsnips, and store the soup-ready parsnip purée in the freezer.

(Pisum sativum)

15 row feet per person for snap peas, 10 row feet per person for snow peas, and 20 row feet per person for shell peas

‘Sugar Snap’, ‘Oregon Giant’ snow peas, ‘Green Arrow’ shell peas

Freeze, pickle (snap peas), or ferment (snap and shell peas)

When peas pop out of the ground in spring, the world is suddenly filled with promise. Cold-hardy peas open the season for crops you can keep, and their sweet, delicate flavor puts them on everyone’s planting list. There is reason to hurry. Garden peas stop flowering and wither away when temperatures rise above 85°F (29°C), which happens in early summer in many climates. In areas where fall lasts long and winters are mild, a small fall crop of peas is often worthwhile.

Low-acid peas are poor candidates for canning because long processing times cause them to soften, but all peas are easy to freeze. If you like fermented foods, you must try fermenting snap peas or shell peas, which keep their crisp texture through the fermentation process. Snow peas cut into bite-size pieces bring color and crunch to homemade kimchi.

The most productive pea varieties share three characteristics: moderate height, determinate growth habit, and a talent for producing pods in pairs. Determinate varieties produce flowers and pods all at once after the plants reach their full height, which for the most productive varieties is between 2 and 3 feet tall.

You can feed four people with 1 pound of snap peas, but you will need to shell out twice as many shell peas to obtain four nice servings.

There are four different types of peas: snap peas, snow peas, shell peas, and soup peas. Most gardeners favor snap peas because they are so productive. You can feed four people with 1 pound of snap peas, but you will need to shell out twice as many shell peas to obtain four nice servings. Snow peas fall in between.

In all pea types, very fast-maturing varieties produce small pods compared to those produced by plants that take a little longer to mature. Unless you need to grow your peas very early so they can mature before summer’s heat, choose varieties that are rated at about 60 days to maturity.

Some pea varieties make beautiful edible ornamentals to grow near garden entryways or other high visibility spots. ‘Golden Sweet’ snow pea has buttery yellow pods; those of ‘Blue Podded’ soup peas are blue.

People can eat a lot of peas when allowed to do so, so unless you live in a very pea-friendly climate, I suggest sticking with the reasonable guideline of 15 row feet per person of snap peas (about 12 pounds), 10 row feet per person of snow peas (about 5 pounds), and 20 row feet per person of shell peas (about 8 pounds shelled). Keep records, and adjust up or down based on your family’s needs.

When gardeners in warm climates speak of peas, they are usually talking about crowder peas (Vigna unguiculata), also known as field peas or Southern peas. Originating in Africa, crowder peas are a warm-weather crop planted in early summer, after tomatoes. The purple blossoms set fruit even in humid heat. You will get the most peas per square foot with semi-vining varieties like ‘Pinkeye Purple Hull’ or ‘Mississippi Silver’. Crowder peas make great freezer crops, or you can dry them and use them like dry beans.

When: Weather has a huge impact on the growth and productivity of peas, which can grow fast or slow, depending on how much sun and warmth the plants receive after getting a cool start. Peas definitely sprout and grow in cold soil, but they grow faster and better in springtime warmth. Start an early planting about 1 month before your last frost date, with the rest of your peas about 2 weeks later. To ensure strong germination, soak peas in water overnight before planting them.

Planting: Peas like closer spacing compared to other vegetables, so plan to grow them in dense double rows on either side of a trellis. Ignore seed company claims that some varieties need no support. Even the shortest-growing peas will end up on the ground when they become top-heavy with pods, and besides, few plants are more fun to trellis than peas. Whether you use bare branches saved from tree pruning or weave a string tapestry between posts, peas eagerly grab on with their curling tendrils, and they won’t let go. Do anticipate that your peas will grow slightly taller than seed catalogs say, and make a trellis for determinate varieties at least 3 feet high.

Prepare a wide planting bed by loosening the soil to at least 10 inches deep while mixing in compost. If you grew peas last year, scatter a few spadefuls of soil from the previous season’s pea patch over the new planting bed. This step ensures that plenty of nitrogen-fixing bacteria are present to assist the plants in feeding themselves. It’s a more reliable way to inoculate soil than using powdered inoculants, which often are stored under conditions that render them worthless. Amend the bed with a balanced organic fertilizer, using just enough to get peas off to a strong start. Poke seeds into the prepared site 2 inches apart and 1 inch deep. Thinning is rarely needed with peas.

Maintenance: Water peas as needed to keep the soil lightly moist, and weed regularly until the plants develop blossoms. After the plants start blooming, try not to disturb the roots with weeding activity.

When grown in cool spring weather, peas have few insect pests except pea aphids, which can be controlled with insecticidal soap should they become numerous. Much more common is powdery mildew, a fungal disease that causes white patches to form on leaves and pods. Grow resistant varieties where powdery mildew is a recurrent problem. Resistant varieties also are available for pea enation virus, a common problem in northern climates that causes new growth to be curled and distorted. Similar leaf curl symptoms can be caused by herbicide contamination in soil or by herbicide drift.

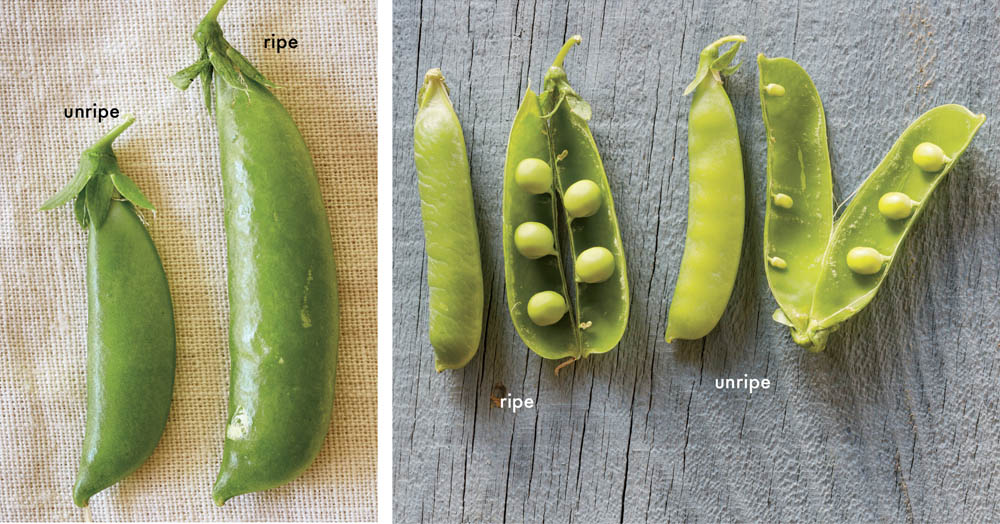

When: Pick peas every other day, preferably in the morning. Pick snow peas when the pods reach full size and the peas inside are just beginning to swell. For best flavor and yields, allow snap peas to change from flat to plump before picking them; snap peas in stores are picked flat and underripe because they ship better that way. Gather sweet green shell peas when the pods begin to show a waxy sheen, but before their color fades. Soup peas can be left on the vines until the pods dry to tan.

How: To avoid mangling the vines, use two hands to harvest peas. Immediately refrigerate picked snow, snap, and shell peas to stop the conversion of sugar to starches and maintain the peas’ crisp texture.

Crush soup pea pods in a paper bag to release the peas. After shelling and sorting, allow soup peas to dry at room temperature until they are so hard that they shatter when struck with a hammer. Store in airtight containers in a cool, dry place.

Many vegetables love being grown in soil recently vacated by peas. After old pea vines have been pulled, spinach, carrots, or fall cabbage are fine choices for follow-up crops.

Left: In home gardens, snap peas can be allowed to plump up fully before they are picked.

Above: Shell peas put their energy into plump peas enveloped in tough, stringy pods. The pods of ripe shell peas have a waxy sheen, and the peas inside are full and round.

Peas are such snackable veggies straight from the garden that many of them will be eaten before they ever reach the kitchen. You’ll want plenty of peas for fresh cooking when peas are in season, but hopefully you will still have some to freeze.

The standard practice is to blanch all types of peas before freezing them, which helps to preserve their color and probably protects some vitamins, too. But in the case of peas, blanching is not done for food safety reasons, so nobody will get sick if you try freezing your peas without blanching them first. Snow peas are prime candidates for raw freezing, because blanching and freezing turns them into soft, watery versions of their former selves.

Canning. Low-acid peas can be canned in a pressure canner, but the overcooked results only vaguely resemble garden peas. However, snap peas pickled in a vinegar brine need only a short processing time and produce a crisp yet earthy pickle well worth making when snap peas are in season. It is also nice that snap peas look so orderly when packed on end into half-pint canning jars. Follow the recipe for Pickled Green Beans to make pickled snap peas.

Fermenting. Both snap peas and shell peas are candidates for fermentation, but several small details are important. First, you must use whole pods that have not had their caps removed. If the little caps are torn off, the damaged tissues are prone to going slimy in the fermentation jar. Air trapped inside the pods makes fermenting peas float, so it is best to pack them into wide-mouthed pint canning jars on end so they can hardly move, cover them with a salt brine, and exclude air with a partially filled bag of water, as shown in Fermenting Veggies Step-by-Step. After about 7 days at cool room temperatures, drain off the cloudy brine, rinse the peas once or twice with cold water, and then cover them with fresh salt brine. Keep refrigerated, and eat the fermented peas as snacks. Eat only the peas from fermented shell peas.

Both shell peas and snap peas (shown here) are delicious when fermented whole, with their caps on.

Peas are open-pollinated and self-fertile, so saving seeds is a simple matter of allowing a few pods from your best plants to mature until the pods dry to brown. Better yet, grow several plants in a bed dedicated to seed growing, and let the plants put all of their energy into the production of seed-quality peas. Shell the seeds and let them dry indoors at room temperature for a couple of weeks before storing them in a cool, dry place. Pea seeds will keep for at least 3 years, and often longer.

(Capsicum annuum)

5 sweet pepper plants and 2 hot per person

‘Sweet Banana’, ‘Lipstick’, and ‘Early Jalapeño’

Freeze, dry, can, or ferment

Many people become passionate about peppers, probably because they are nutritious, beautiful, and never fail to excite the palate. These warm-natured plants can be a challenge to grow in climates with short summers, but in most areas both sweet and hot peppers are as easy to grow as tomatoes. For top flavor, peppers should be allowed to ripen until they begin to change colors. Except for a few dark green southwestern peppers such as poblanos, green peppers have fewer vitamins and lack the flavor complexities of ripe ones.

Peppers can be frozen, dried, or combined with tomatoes and other seasonings in canned salsa or pasta sauce (see the recipes). Both sweet and hot peppers make wonderful refrigerator pickles, and the types of hot sauces you can make with hot peppers are truly endless, including several fermented versions.

Grow a diversity of flavorful peppers, such as pimentos, paprika peppers, banana peppers, and small-fruited bells.

The most versatile peppers for year-round eating are sweet peppers, plus some hot peppers that won’t blow your head off, such as jalapeños. Among sweet peppers, many of the best home garden varieties have conical shapes or are smallish versions of traditional bell peppers, which grow best in warm climates. Pepper varieties that produce medium to small fruits tend to produce earlier and better than large-fruited peppers, which require a bit more patience and luck. For garden planning purposes, I divide peppers into three main groups: small sweet peppers that produce early enough to use in tomato canning projects, large sweet peppers for fresh eating and freezing, and hot peppers for canning, drying, and creative condiments. Here are some excellent varieties within each group.

Pepper varieties that produce medium to small fruits tend to produce earlier and better than large-fruited peppers, which require a bit more patience and luck.

The varieties listed above are productivity champs in a wide range of climates, but if you live where summers are long and warm — or have a passion for hot peppers — there are specialty peppers to fill every need. Many southwestern peppers tend to mature quite late when grown in northern latitudes, but they can be phenomenal producers farther south. Habaneros are too hot to put on the table, but if you’re dreaming of making your own mango-habanero sauce, by all means make room for a couple of plants.

When: Plant peppers in late spring, after the soil has warmed and the last frost has passed. Start seeds about 6 weeks before your last frost date. Pepper seeds take longer to germinate compared to tomatoes, and they are prone to rot under very wet conditions. Provide very bright light, and transplant to 4-inch containers after the first true leaves appear.

Planting: Prepare the soil in a sunny spot with a near-neutral pH. Scatter a sprinkling of wood ashes or ground eggshells over soil that tends to be slightly acidic. Allow at least 2 feet of space between pepper plants. Into each planting hole, mix a standard dose of balanced organic fertilizer and a heaping shovelful of compost. Set peppers deeply so that their seedling leaves are just covered, and water well.

Maintenance: Peppers can tolerate high heat, but they produce best when they never run short of water. A thick mulch of grass clippings pleases most peppers. Late in the season when peppers become top-heavy with fruits, the plants are likely to fall over. Propping up fallen plants may do more harm than good, because the branches are brittle and break easily. It is best to prevent peppers from falling over by staking them early or growing them in small tomato cages.

Tomato hornworms and swarming insects. Pepper foliage is sometimes consumed by tomato hornworms (see Tomato Pests and Diseases), which are easy to spot and hand-pick from pepper plants. In some locations, swarming insects, including blister beetles and brown marmorated stink bugs, can ruin ripening fruits; the best defense is a lightweight row cover tent or tunnel installed before the hordes appear.

Viruses. Leaves that show distorted crinkles or grow into thin strings display symptoms of virus infection. Many varieties are resistant to common pepper viruses, which tend to be most common in warm climates.

Sunscald. When plants set fruit but have a sparse cover of leaves to protect them from bright sunshine, the fruits may develop patches of light-colored sunscald, which never ripen properly. Where sunscald is a chronic problem, try growing peppers in a row between rows of tall sweet corn or sunflowers. In small plantings, a shade cover made from lightweight cloth can be attached to thin stakes with clothespins.

A healthy pepper plant can produce more than 5 pounds of peppers, but only one or two fruits will ripen at a time, with the biggest harvest coming in the fall. Warm summer weather helps peppers produce heavier crops, while short, cool seasons mean fewer peppers per plant.

A good rule of thumb is to grow five sweet pepper plants and two hot pepper plants per pepper eater in order to have enough for eating fresh, pickling, freezing, and canning.

When: Peppers can be harvested as soon as they begin to show blushes of red, yellow, or orange color, and then allowed to finish ripening indoors for up to 2 days.

How: Use floral snips or scissors to cut peppers from the branch, leaving a short stub of stem attached. Some peppers readily break away when pulled, but others cling to brittle branches, causing the branches to break.

You can let peppers ripen on the plants in warm weather, but bring them indoors to finish ripening in the fall, when cool nights slow the ripening process. Before your first frost, gather all almost-ripe peppers (extremely underripe peppers will just collapse) and bring them indoors. They will show signs of ripening within a few days. Fully ripened peppers should be refrigerated.

After peppers start to change colors, you can let them finish ripening indoors, where they are safe from insects and stressful weather.

Freezing is the easiest way to preserve peppers, because peppers cut into strips or squares don’t need to be blanched first. You can dry peppers without blanching them, too, and dried peppers can be used in cooking or pulverized into concentrated powders (paprika and chili powder are made from powdered dried peppers). Many people grow peppers for making salsa, and refrigerator pickled peppers are equally popular among those who have discovered them (see the recipe). And when made with low-sugar pectin, canned pepper jelly works great as a quick base for sauces (barbeque or Asian sweet-and-sour sauces, for example). If peppers are your pride, you will eventually dabble in fermented hot sauces. Sriracha, Tabasco, and many other popular hot sauces are made from salt-fermented ground peppers to which vinegar is added as a stabilizing agent.

When made with low-sugar pectin, canned pepper jelly works great as a quick base for sauces, such as barbeque or Asian sweet-and-sour sauce.

The most versatile way to freeze peppers is to cut them into narrow strips and put them in freezer bags. Each time you add more to the bag, give it a shake to keep the peppers loose in the bag. I like to set aside perfect peppers, cut them in half and remove the cores and ribs, and freeze them for stuffing later. In this instance I do recommend steam blanching pepper halves until barely soft (no more than 4 minutes) before cooling and freezing them. I also blanch peppers like poblanos and Anaheims, to be stuffed as rellenos, but blanching is not a food safety rule as much as a culinary preference. Peppers that have been roasted or grilled are great when frozen, too.

Unless you live in an arid climate, you will need a dehydrator to dry peppers. Cut clean sweet or hot peppers into strips or squares, and dry until almost crisp. Drying times will vary with pepper variety and thickness of the flesh. Spice peppers that are to be ground into paprika or other powders dry quickly, and fresh paprika is wonderful! Store your dried peppers in vacuum-sealed containers or in canning jars kept in the freezer.

One of the tastiest ways to preserve peppers is to smoke them on a covered grill before drying. Peppers pick up smoke flavors and aromas better than other vegetables, so only 30 minutes in apple wood smoke infuses them with flavor. After smoking, the peppers can be dried or frozen.

In the Southwest, thin-walled peppers often are dried whole on strings, called ristras. Chiles dried this way concentrate their flavors as they cure, but this method works best in dry climates.

Care must be taken when canning jalapeño rings or other pepper products, which require acidification to ensure that the pH is low enough to inhibit the growth of bacteria. When canning pickled peppers or salsa, always follow a trusted recipe that includes one of three acidifying agents: powdered citric or ascorbic acid (1⁄4 teaspoon per pint), bottled lemon juice (1 tablespoon per pint), or vinegar (2 tablespoons per pint).

You can use salt fermentation to extend the refrigerator shelf life of firm-fleshed peppers, such as jalapeño slices. Sliced peppers that ferment for 5 to 7 days can be repacked in fresh salt brine and stored in the refrigerator for months.

Popular pepper sauces such as sriracha and Tabasco are made from peppers that are softened via fermentation, but the shorter route is to press poached or steamed hot peppers through a sieve or food mill and use the paste as a basis for unique hot sauces such as mango-habenero sauce or garlicky green jalapeño sauce. Recipes that include a high concentration of vinegar and little or no water can be canned in a water-bath or steam canner, but keep other pepper sauces in the refrigerator.

Or keep it simple. Pack small hot peppers into a jar and cover them with vinegar. After 2 weeks or so on the countertop, the vinegar will be hot enough to use as a hot sauce, and the little peppers can be chopped into recipes to add warmth and bite to cooked dishes.

The recipes for Garden Salsa and Garden Pasta Sauce call for plenty of peppers, as do many spicy relishes. Note that when low-acid peppers are added to canned food products, proper acidification becomes crucial. Follow the recipe!

Thin-walled peppers like paprika peppers (shown here) and cayennes can be dried whole in warm, dry weather. Store dried peppers in the freezer until you are ready to grind them into spice powders.

Makes 3 pints

(Solanum tuberosum)

20 row feet per person

‘Caribe’ early, ‘Kennebec’ midseason, and ‘Russian Banana’ fingerling

Place in cool storage, dry, or can

Easy to grow and simple to store in a cool pantry or basement, potatoes are one of the best sources of food energy you can grow in a garden. It’s also easy to save and replant your favorite strains, or you can plant purchased potatoes you like that show signs of sprouting. A single small spud can multiply itself into a cluster of fresh, juicy potatoes.

All potatoes naturally break dormancy after a few months, and by spring you may find yourself with sprouting potatoes more fit for the garden than the table. This is why it is important to preserve your imperfect or excess potatoes soon after you harvest them. Drying is the best long-term storage method. Whether you grate cooked, cooled potatoes for hash browns or cut them into slices, dried potatoes are a top convenience food in your homegrown pantry.

There are many perfect potatoes, including yellow and pink fingerlings, all-purpose potatoes with blue or yellow flesh, and waxy red potatoes for boiling or roasting.

To have garden-grown potatoes on the table most of the year, you will need to grow at least two different types: early-maturing varieties to enjoy as fresh potatoes in summer and fall, and mid- or late-season varieties for storing into winter. If you have space, a planting of fingerling potatoes will bring welcome diversity.

When: Plant potatoes 2 to 4 weeks before your last spring frost date, or when the soil has started to lose its winter chill. It is always better to delay planting until the soil warms than to plant potatoes in cold, wet soil. Plant your early potatoes first, followed by your storage crop. An unexpected late freeze will kill potato foliage back to the ground, but the plants will regrow. An old quilt or comforter spread over the little plants overnight will usually prevent freeze damage.

In hot summer climates where late-maturing potatoes are difficult to grow, make a second planting of fast-maturing potatoes in late summer. Fall potatoes will begin forming tubers when soil temperatures fall below 70°F (21°C), but the crop will be light compared to spring, when potatoes grow vigorously in response to longer days and warming temperatures.

Handling seed potatoes: Starting in late winter, place potatoes you want to grow or purchased seed potatoes in a warm, sunny spot indoors. The warmth will encourage sprouting, and exposure to sunlight makes the skins turn green and bitter, which makes the potatoes less appetizing to critters. A few days before planting, cut any seed potatoes larger than a golf ball into pieces that have at least three puckered “eyes” on each piece. Allow the cut pieces to dry, and don’t be alarmed if they turn black. The darkened, leathery surfaces will resist rotting better than freshly cut ones. If you can’t plant right away and need to hold cut seed potatoes, place them in a paper bag with the top folded down.

Potatoes smaller than a golf ball can be planted whole. Whole potatoes start growing faster than cut pieces, so if you plan to save and replant your own seed potatoes, set aside the small ones as your planting stock. Walnut-size potatoes are perfect for planting whole.

Planting: Potatoes grow best in rich, well-drained soil with a slightly acidic pH. Before planting, incorporate a 1-inch blanket of compost into the planting bed along with a half ration of a balanced organic fertilizer. Sawdust that has rotted to black also makes a fine soil amendment for a potato bed.

Space potatoes 14 inches apart; very vigorous late varieties may need more space. Crowding causes plants to produce numerous small potatoes, with wider spacing leading to larger spuds. Some people prefer growing potatoes in hills, with three plants per 24-inch-wide hill.

After planting potatoes 2 to 3 inches deep, you can let the soil warm in the sun for a few weeks or go ahead and mulch over the planted space. The emerging stem tips will push through any biodegradable mulch like shredded leaves or grass clippings, but you will get better weed control and warmer soil by waiting until the plants are 10 to 12 inches tall to mulch them.

Maintenance: As you weed, hill up loose soil around the base of the plants. In early summer, mulch potatoes with a 3-inch-deep mulch, which will keep the soil cool and block sunlight that will turn shallow tubers green. Mulches also serve as an obstacle course to Colorado potato beetles and other insects that travel on foot. Many materials work well, including grass clippings or half-rotted leaves (straw is often laced with pesticides). Every week or so, check for gaps or thinned spots, and pile on more mulch.

Warm sunlight turns seed potatoes green and encourages them to sprout.

The color of potato blossoms reflects the variety’s skin color. Red- or blue-skinned potatoes bloom pink or lavender, while the flowers borne by tan-skinned varieties are white.

Colorado potato beetles. These are the biggest insect threat to potatoes. Start looking for the brick-red, soft-bodied larvae just as flower buds form, and either hand-pick them or treat the plants with spinosad (an organic biological pesticide). Flea beetles often make small holes in potato leaves, but they do not seriously weaken the plants.

Late blight. Extended periods of cool rain can set the stage for outbreaks of late blight, the dreaded disease that also infects tomatoes. Plants appear to melt down over a period of a few days. Promptly dig and eat any potatoes from infected plants, and compost the foliage. Do not save and replant potatoes produced in a bad blight year. Though they may seem fine for eating, they can be the source of early-season disease outbreaks when planted in the garden.

Voles. In many areas, small tunneling rodents called voles help themselves to garden potatoes. When ready-to-harvest potatoes mysteriously disappear, voles are the most likely explanation.

Depending on your soil, chosen varieties, and the kindness of the weather, expect to produce 1 to 11⁄2 pounds of potatoes per row foot. A 4- by 6-foot bed will produce about 25 pounds of potatoes, as will a 10-foot-long double-wide row or a 20-foot-long single row.

If you divide your potatoes into early potatoes for fresh eating and later potatoes for storage, plan on 20 row feet per person for each planting, with the goal of growing a total of 50 pounds plus per person per year, or more if you plan to share. In climates that are too cool to grow good crops of sweet potatoes (see Sweet Potatoes), you may want to increase the size of your regular potato plantings.

When: Harvest early potatoes when the foliage stops growing and begins to look tired and pale. Harvest storage potatoes at least 2 weeks after the tops have died back, but before the first frost. Potatoes grown in intensive beds can be gathered by hand; a follow-up light forking will turn up most of the spuds in hiding.

Cleaning and sorting: Handle fresh potatoes gently, and resist the temptation to wash them. The skins are much too fragile, but they will toughen up as they cure. Do sort through your spuds carefully, and place sound potatoes in one pile, and those with any type of issue — from green ends to unexplained holes — in another. You can trim, cook, and eat these culls, or preserve them using one of the food preservation options discussed here.

Storing summer potatoes: Your first storage challenge will come in summer, when you need temporary quarters for early potatoes that won’t be eaten for a couple of months. If your summer harvest is modest, cure your potatoes as described below for a few days, and then store them in boxes in the coolest place you can find. Our bedroom stays cool in summer, so I store boxes of precious summer fingerlings under my bed. Do not refrigerate potatoes, because very cold temperatures cause potatoes to convert starches to sugars, which in turn causes them to darken when they are cooked.

You can also store your summer potatoes in a trench or hole where they are covered with at least 6 inches of loose soil. Then cover the mound with several folds of newspaper to help it shed excess rain. The buried potatoes will wait out warm weather in cool, moist conditions and can be gathered as needed for use in the kitchen.

Curing for long-term storage: Flawless potatoes that stay in the ground until the plants’ tops wither are the best candidates for long-term storage. Curing or drying the potatoes for 7 to 10 days further improves their storage potential. If you have clay soil, you may want to lightly rinse off excess soil, then pat the spuds dry. Lay them out in a dim room and cover them with a cloth or towels to block out sunlight. During this time, the skins will dry, small wounds will heal over, and new layers of skin will form where the outer layer peeled or rubbed off. After 3 or 4 days, turn the potatoes over so all sides can dry.

Cured potatoes can be stored in a basement, unheated garage, root cellar, or any other place where temperatures will range between 45 and 55°F (7 and 13°C). Keep them covered with a thick cloth to block light (see Seven Ways to Storage Potatoes). Check your stored spuds every 2 weeks for signs of spoilage and, later on, sprouting. Many varieties are finished resting and ready to start growing after 3 to 4 months.

Work carefully when gathering potatoes to avoid slicing or spearing your beautiful crop.

Basement steps serve as a cool, dark storage spot for a fresh crop of potatoes.

If you have little or no cool storage, or more culls than keepers, you can dry or can your potatoes for long-term storage. Freezing is not recommended, because the flesh and water separate as potatoes freeze and thaw, with unpleasantly mealy results.

Pressure canning brings out the buttery notes in waxy potatoes, and you can process a batch at 12 pounds of pressure in 35 minutes. The pieces should be blanched before packing them into hot jars, but they need not fit tightly. Fresh boiling water amended with citric acid (to prevent discoloration) is poured over the prepared potatoes before they go into the pressure canner. Note: Potatoes are a low-acid food and cannot be canned in a water-bath or steam canner.

Dehydrated potatoes are an essential ingredient in dry soup mixes, and dried potato slices make excellent scalloped potatoes or potatoes au gratin. Using the culls from the main crop, I like to dry at least one batch of potatoes each year. In spring when the fresh potatoes are gone, dried potatoes can save the day.

The most common way to dry potatoes is to dry slices. Slice well-scrubbed potatoes into uniform pieces and drop them into a bowl of cold water with a teaspoon of citric acid mixed in (to prevent discoloration). Bring a pot of water to a boil, and blanch the pieces until they are barely done, about 5 minutes. Cool slightly before arranging on dehydrator trays. Dry potato slices until hard and opaque — your house will smell like baked potatoes!

Cooked potatoes dry quickly and save preparation time when you need potatoes for soups or casseroles.

As you harvest your crop, set aside potatoes with cracks, sprouting ends, or other issues, and make a big batch of Tomorrow’s Hash Browns, which can be dried or frozen.

(Cucurbita pepo, C. maxima, C. moschata)

4 to 6 plants

‘Baby Pam’, ‘Long Pie’, ‘Winter Luxury’, ‘Jarrahdale’, ‘Long Island Cheese’, and ‘Dickinson Field’

Freeze or dry

Like winter squash, pumpkins were important pantry items for many Native American tribes. Just as we might do today, cooks stirred pieces of pumpkin into porridge and dried the surplus in strips hung by the fire. Then pastry-minded colonists arrived, and the pumpkin pie was born. The culinary world was forever changed for the better.

Pumpkins come in a huge range of sizes and colors, and botanically speaking, there is no clear dividing line between pumpkins and winter squash. But as a culture, we define pumpkins as round, orange fruits with jack-o’-lantern potential. The best pumpkins for eating are small to medium in size and have dense, thick flesh enclosed in a thin skin. Pumpkins sold for carving are very different, with thin flesh and sturdy skins.

Pumpkins will keep in a cool, dry place for a couple of months, which gives you time to enjoy them in nutritious soups, pies, and baked goods. If you have a bumper crop, extra pumpkin can be dried or frozen as pie-ready purée or spicy pumpkin butter.

Depending on which varieties you choose, you can grow a few large pumpkins or a number of smaller ones. Good small pumpkins include ‘Baby Pam’ and ‘New England Pie’. Robust ‘Long Island Cheese’ pumpkins need more space to produce their 6- to 10-pound fruits.

In addition to hard rinds, most pumpkins grown to be jack-o’-lanterns have watery, weak-flavored flesh compared to varieties selected for their culinary and nutritional qualities. Small-fruited pumpkins are the best varieties for climates with short growing seasons, because they grow quickly and the fruits continue to ripen after they are harvested. In warmer climates where pest pressure is severe, pumpkins classified as C. moschata resist squash vine borers. Here are six good-tasting varieties, from smallest to largest.

Small-fruited pumpkins are the best varieties for climates with short growing seasons; pumpkins classified as C. moschata resist squash vine borers and are best in warmer climates.

I like to grow one planting of a big storage pumpkin and a second planting of a variety that bears smaller fruits. In my pantry, the dream yield is four to five heavy 15-pound pumpkins for processing, and a dozen or so small pumpkins for decorating, sharing, and fresh cooking. This goal can be accomplished by growing only four to six plants of any individual pumpkin variety, because a successful vine will produce 20 pounds of fruit, or maybe twice that much! For pollination purposes you also need four to six plants of a given variety, though pumpkins classified as C. pepo can share pollen with summer squash, and butternuts help provide pollen for pumpkins classified as C. moschata.

Whole pumpkin seeds consist of a hard, woody outer hull with a flattened, oblong seed inside. You can clean, dry, roast, and eat the seeds (also called pepitas) from any pumpkin, but you will get the best seeds from special pumpkin varieties grown exclusively for their dark green, oil-rich seeds. In addition to the plump pepitas, seed pumpkins bear seeds whose hulls are so thin that they fall away as the seeds dry. ‘Kakai’ (C. pepo) produces splashy green-striped orange fruits that weigh 6 to 8 pounds, usually producing two to three fruits per plant. ‘Lady Godiva’ (C. pepo) has semi-hull-less seeds. It produces 6- to 8-pound fruits in about 110 days, usually two to three per plant. Each seed pumpkin should produce a half cup of dried seeds.

Pumpkin seeds are rich in protein, manganese, zinc, and a long list of other nutrients. When pressed, they yield a delicious yet heat-sensitive oil. You can utilize the oily nature of raw pumpkin seeds by pulverizing them into a meal using a food processor. A sprinkling of pumpkin seed meal releases enough fat to lubricate a warm pan for the cooking to come.

Oil-seed pumpkins are grown just like other pumpkins, but they are processed very soon after harvesting in order to collect the seeds in peak condition. The discarded pumpkins can be composted. Like jack-o’-lantern pumpkins, they don’t taste very good. The few commercial producers of oil-seed pumpkins in the United States have teamed up with farmers who feed the pumpkins to their pigs.

When: Pumpkins are planted late, after the soil has warmed, and where summers are very long they are not planted until early July for harvesting in October.

Preparing seedlings: You can plant pumpkin seeds where you want the plants to grow, but you will have better control over timing and spacing if you start seeds in containers and set out 3-week-old seedlings exactly where you want them. You won’t need fluorescent lights because you can grow the seedlings outdoors, in real sunlight. Pumpkin seedlings grown outdoors in 4-inch pots need no hardening off and can be set out when the first true leaf appears, when they are about 3 weeks old.

Planting: Small pie pumpkins can be planted 12 to 14 inches apart, but allow more space between plants when growing hefty storage pumpkins. A well-prepared 5-foot-diameter hill will support four plants of any type of pumpkin. Enrich it first with a 2-inch layer of compost and a balanced organic fertilizer. You can set out six plants and thin back to the strongest four after a couple of weeks. Gaps in rows of early corn are another great place to slip in a few pumpkin plants. Just be sure that the corn is at least 24 inches tall before interplanting it with pumpkins.

Squash vine borers. Like summer squash, pumpkins classified as C. pepo are at high risk for damage from squash vine borers (see Summer Squash Pests and Diseases). Many gardeners choose C. moschata varieties for their main crop pumpkins because they have a very high level of resistance to this widespread pest.

Squash bugs. All pumpkins can be seriously damaged by squash bugs, which suck juices from pumpkin stems, leaves, and fruits. See Summer Squash Pests and Diseases for strategies for controlling squash bugs in your pumpkin patch. You may be able to sidestep problems with squash vine borers and squash bugs by planting late and growing the plants beneath floating row covers until they begin to bloom heavily.

Powdery mildew. As pumpkin vines age, they often become infected with powdery mildew; infected vines will produce, but the fruits may be weak of flavor. Pumpkin hybrids with powdery mildew resistance are available where disease pressure is severe. When used preventively, milk sprays (1 part any type of milk to 4 parts water) applied every 7 to 10 days from late July onward can delay the onset of cucurbit powdery mildew.

Some gardeners don’t grow pumpkins because they take up so much space, and it’s true that pumpkin vines will grow anywhere from 10 to 30 feet long, depending on variety. Why not grow them outside your garden, and let the vines run over grass you would otherwise have to mow? Or on the edge of your corn patch, so the vines run among the withering stalks? You don’t necessarily need a cushy garden bed, because pumpkins grow as well in hills enriched with compost as they do in the ground. Which would you rather do — grow pumpkins or mow the lawn?

When to harvest: Allow pumpkins to ripen on the vine as long as possible, at least until the vines begin to die back. The rinds should be hard enough to resist puncturing with a fingernail. Fruits of small pie pumpkins may be partially green, but they will turn orange as the fruits are cured. Ripe moschata pumpkins have no green stripes, and they turn from pinkish beige to a rich brown beige as they ripen.

Use pruning shears to cut pumpkins from the vine, leaving at least 1 inch of stem attached.

How to harvest: Use pruning shears to cut pumpkins from the vine, leaving at least 1 inch of stem attached.

Curing: Wipe pumpkins clean with a damp cloth, then cure in a 70 to 80°F (21 to 27°C) location for 2 weeks. In late summer, this usually can be done outdoors.

Storing: Store cured pumpkins in a cool, dry place such as a basement or unheated greenhouse. Check weekly for signs of spoilage. Be watchful for mold forming around the base of the stem or soft spots anywhere on the pumpkin. Rather than take chances, eat or process pumpkins that show signs of deterioration.

If you have a lot of pumpkin, you can put your freezer and food dehydrator to work saving your pumpkin for late-winter meals.

Freezing is the best way to put by a lot of pumpkin in ready-to-use form for baked goods, pies, and soups. After wiping the pumpkin clean, cut it into chunks no bigger than your hand and scrape off the strings and seeds with a grapefruit spoon or small serrated knife. Place the cleaned pieces on their sides in a large baking dish, and roast uncovered at 350°F (180°C) for about 45 minutes, or until the pumpkin pieces soften and release their juices. Allow the pieces to cool, pour off the liquid, and scrape the cooked flesh from the rind. If the flesh is extremely drippy (this can vary from one individual pumpkin to another), drain it in a colander for an hour or so. You can freeze the cooked pumpkin in chunks, mash it with a potato masher, or purée it in a food processor before freezing it in freezer-safe containers.

Native Americans and early settlers preserved their pumpkins by hanging thin strips by the fire to dry. The pumpkin chips were then added to the cooking pot in winter, along with dried beans and meat. In the modern kitchen, you can quickly cut raw pumpkin into thin slices using a mandoline; the slices can then go straight into the dehydrator. Raw pumpkin chips take only a few hours to dry.

You also can steam 1-inch chunks of raw pumpkin until just done, toss them with sugar and spices, and dry the pieces until leathery in the dehydrator. The “pumpkin chews” make a great snack, and they are a tasty and nutritious addition to grain salads or oatmeal.

Make “pumpkin chews” by steaming 1-inch chunks of raw pumpkin until just done, tossing them in sugar and spices, and drying them in a dehydrator until leathery.

Until the 1980s, garden cooks routinely made and canned sweet and spicy pumpkin butter, a dark brown, spreadable alternative to apple butter if you have no apples. The problem is that pumpkin butter can be up to two full pH points less acidic than apple butter, making it unsafe to can in a water-bath or steam canner. Even making a hybrid apple-pumpkin butter with added lemon juice will not bring the pH of pumpkin butter down to 4.6, the safe level for jams, jellies, and fruit butters.

Even though you can’t can it, pumpkin butter is still well worth making (see the Harvest Day Recipe below). You can slather pumpkin butter over waffles or pancakes, and it makes a great filling for cinnamon rolls or crumb cakes. If you like fruit leathers, you will love “pumpkin pie jerky” made by drying sheets of pumpkin butter in a food dehydrator.

Bubbling-hot pumpkin butter is extremely dense, and I have found that when I spoon it into hot pint jars — kept waiting in a 150°F (65°C) oven — and screw on new lids, the lids seal as the jars cool. I store the cooled, sealed jars in the fridge, where they keep beautifully for a couple of months.

Or simply freeze your pumpkin butter for future use. You can freeze small portions in a silicone muffin pan, and then transfer the frozen pumpkin butter to a freezer bag for long-term storage.

Makes 5 half-pint jars

(Raphanus sativus)

Up to 15 row feet

‘Champion’, ‘Easter Egg’, ‘French Breakfast’, and ‘Misato Rose’

Refrigerate, ferment, or pickle

If you think of radishes exclusively as a salad vegetable, think again. Roasting radishes tames and mellows their flavors, so they become like savory little turnips, only with more color, and you can use radishes as stir-fry vegetables, too. Or preserve raw radishes by combining them with cabbage and other vegetables in delicious veggie ferments.

Radishes often are regarded as the perfect spring vegetable for beginning gardeners, but this is a myth. Spring’s changeable weather is hard on radishes, and hungry flea beetles make things worse, so spring radishes usually need attentive help from their keeper. The story changes in the fall, when the soil is getting cooler rather than warmer. Radishes that plump up when fall weather gets nippy are always the best ones of the year.

You won’t need special radish varieties for roasting or fermenting, because the same radishes that bring color and flavor to salads are great in cooked dishes or fermented with cabbage. In addition to fast-maturing round radishes, consider varieties with elongated roots, including Chinese radishes, which take less time to scrub and slice. If you love fermented foods, you will definitely want to grow big daikon radishes in the fall, too.

Radishes mature quickly and all at once, so it is best to make multiple small sowings. In addition to growing radishes in their own row or bed, you can use them as markers between rows of slow-growing vegetables like carrots, parsley, or parsnips. We eat all of our spring radishes fresh, so those plantings are very small. Grow more radishes in fall — up to 15 row feet — to use in vegetable roasts and fermentation projects.

When: Be patient when growing radishes in spring, and wait until 3 to 4 weeks before your last spring frost to start planting them. The best spring radishes grow when the soil is still cool but days are getting steadily warmer. In fall, start planting radishes about 8 weeks before your first fall frost.

Planting: Radishes are not heavy feeders, so enrich their planting space with either 1 inch of good compost or a light sprinkling of a balanced organic fertilizer. Radish seeds are dependable germinators, but you can enhance fast, uniform sprouting by covering the seeded bed with a double thickness of fabric row cover until the seedlings appear.

Maintenance: It is almost always necessary to thin radish seedlings to no less than 2 inches apart. Thin radishes early, when they have only two or three leaves, by using scissors to snip off extra seedlings at the soil line. This type of thinning minimizes disturbance to roots of neighboring plants, which is an important consideration when growing radishes. Weeding should be done early and often for the same reason.

In any season, fast-growing radishes must be kept constantly moist — a little wet is better than dry. Consistent moisture is the essential key to growing good radishes. Radish flavor is primarily determined by variety, but hot weather and drought encourage the development of spicy flavor compounds, which are similar to those found in horseradish.

The longer radishes stay in the ground, the more likely they are to develop cosmetic problems caused by weevils, wireworms, or cracking due to changing soil moisture levels. Growing radishes quickly, in ideal weather, is the best way to avoid these problems.

Spring crops of radishes are often hit hard by flea beetles, which leave tiny holes in the leaves but do not injure the roots. You can avoid them altogether by growing radishes under row cover tunnels installed at planting time. Keep in mind that skin imperfections disappear when radishes are cut up and cooked.

All spring-sown radishes are inclined to bolt, especially if they are planted very early and exposed to cold weather. Planting later in spring reduces the likelihood that plants will bolt instead of producing plump roots. Bolting is rare with radishes grown in late summer and fall.

When: As radish roots plump up, they push up out of the soil. Harvest radishes within a few days after the roots swell.

How: Immediately cut off the leaves with a sharp knife or kitchen shears. Wash the radishes gently to remove soil, but wait until just before using them to scrub them clean. Dry between clean kitchen towels before storing in plastic bags in the refrigerator for up to 2 months.

Oriental daikon radishes (Raphanus sativus var. longipinnatus) are one of my favorite fall crops. In addition to eating the long, lovely roots, daikons produce an abundance of foliage for composting. I plant daikon radishes for the table and for the soil, and also use them as a fill-in crop when other fall planting plans go asunder. Weeds don’t have a chance once the daikons get going, and I love the way the roots push up out of the ground when they reach perfect condition for harvesting.

Daikon radishes are at peak eating quality when they are less than 12 inches long, but many varieties will continue to grow much larger if given the chance. Cold winter weather causes daikon radishes to die back and rot, but this is what you want to happen! When you use unharvested daikons as a cover crop, the deep roots create a vertical vein of organic matter in the soil. As a “biodrill” crop to improve soil tilth and health, daikon radishes have it all — they suppress weeds, penetrate compacted subsoil, and can easily be killed by chopping off their heads in climates mild enough to permit their winter survival.

Which daikons to eat, and which to allot to the soil? The dilemma will never go away, but it is most easily handled by growing plenty of daikon radishes every fall.

Radishes store well in the refrigerator, but make plans for excess radishes soon after they are harvested, while they are still in perfect condition. Radishes are ideal fermentation partners for cabbage — the simple combination of shredded cabbage, sliced radishes, and salt makes a delicious sauerkraut (see here for step-by-step instructions). Or ferment sliced daikon radishes with plenty of garlic for the crunchiest “pickles” of fall. Small, one-bite radishes can be pickled in a vinegar brine and kept in the refrigerator for use in salads. Processing softens radishes, but they stay crisp for weeks when handled as refrigerator pickles.

Fermented red radishes

Many people eat sliced radishes on buttered bread, which is the idea behind radish butter. This is a great use for cracked or blemished radishes.

Makes about 3 cups

Coarsely chop the radishes in a food processor, then add the butter, herbs, and salt, and mix until combined. Store in the refrigerator for up to 3 days. Allow to soften at room temperature for an hour before serving on bread or crackers.

(Rheum × hybridum)

3 plants

‘Victoria’, ‘McDonald’, ‘Crimson Red’, and starkrimson (‘K-1’)

Freeze, can, or dry

From its Himalayan home, robust rhubarb got a lift to Europe with Marco Polo and was introduced in America around 1820. Hardy and resilient, rhubarb is now grown in temperate climates around the world. One of only a few perennial vegetables, rhubarb plants often produce for years with little care.

Growing rhubarb is easy in climates that are cold enough to grow tulips as perennials, or in Zones 3 to 7. The plants must have a cold-induced period of winter rest, and they also suffer when temperatures rise above 90°F (32°C). In the northern half of North America, rhubarb plants can be phenomenally productive, yielding stalk after stalk for pies, preserves, baked goods, and teas. Rhubarb’s sour lemony flavor is due in large part to oxalic acid, which reaches toxic levels in rhubarb leaves. Rhubarb leaves should never be eaten but are perfectly safe to use as compost or mulch.

Rhubarb varieties vary in stem color, vigor, and heat tolerance, but the differences are small.

Two older rhubarb varieties that have stood the test of time, ‘Victoria’ and ‘McDonald’, produce light green stalks tinged with red. The vigorous, disease-resistant plants are good choices for hot summer areas, though they thrive in colder climates, too.

Red stalk color is more pronounced in rhubarb varieties that can do double duty as edible ornamentals, such as ‘Crimson Red’ and starkrimson (‘K-1’). While red rhubarb is often preferred in markets, red stem color has no bearing on flavor.

If one of your neighbors is growing rhubarb, you may be able to get an excellent locally adapted strain for the asking. Most gardeners with established rhubarb plants have plenty of divisions that can be cut off and shared.

For most households, three established rhubarb plants will easily produce a year’s supply. More than five plants is probably too many unless you have a very large family.

When: Planting rhubarb is best done in spring, a few weeks before your last frost date, in moist, fertile soil in full sun to partial afternoon shade.

Planting: Space plants 4 to 5 feet apart, or use them as focal point plants around your garden’s boundary. Enrich planting holes generously with compost as well as a standard application of a balanced organic fertilizer when planting rhubarb.

Maintenance: Allow a year for transplanted rhubarb to become established in the garden. Mulch to prevent weeds, and provide water during dry spells. In many areas, rhubarb plants deteriorate in midsummer and then make a comeback in fall. Rhubarb plants are killed to the ground by hard freezes, and the roots remain dormant through winter.

In late winter, rake up and compost old mulch and plant debris from your rhubarb patch, and scatter a balanced organic fertilizer over the soil. Top off with a thick organic mulch that will deter weeds until the plants leaf out.

Propagation: Established rhubarb plants multiply by division. New offshoots can be dug away and replanted or shared in late spring, when plants are showing vigorous new growth, or in late summer. Plants that have more than three crowns should have the outermost ones removed to preserve plant vigor. Use a sharp spade to sever offshoots without digging up the main crown.

The most common cause of holes in rhubarb leaves are slugs, which take shelter beneath the low leaves during the day. Remove withered leaves to reduce slug habitat, hand-pick the slugs at night, or put out slug traps baited with beer. In some years, Japanese beetles develop a strong appetite for rhubarb leaves, but they are easy to hand-pick into a broad bowl on cool mornings.

Leaf spots often become numerous on older rhubarb leaves in hot, humid weather, and in some seasons the plants may melt down to a few stalks in midsummer. Then the plants come back in early fall and produce a few nice young stems for eating or drinking.

Rhubarb stems contain much less oxalic acid than the leaves, so they are safe to eat in reasonable quantities and provide vitamins A and C. But eating too much rhubarb too often might not be a good idea because of possible stress to kidneys, inflammation of joints, or even death. An adult would need to eat several pounds of rhubarb to feel ill effects, with 20 to 25 pounds of fresh rhubarb as a lethal dose.

Possible death by rhubarb is an entirely modern fear, because until refined sugar became cheap and widely available, rhubarb’s sour flavor naturally kept people from eating too much. Limiting how much sugar you eat will limit your rhubarb intake, too. The sugar dilemma has also led me to rediscover several old uses for rhubarb, like using rhubarb juice in place of lemon juice to prevent discoloration of apples and other cut fruits. Small pieces of lightly cooked rhubarb readily give up their juice.

When: A year after planting, harvest two or three rhubarb stalks per plant weekly in late spring by twisting them away from the base. In subsequent seasons, harvest all the stalks you want for 6 weeks in late spring, and then allow the plants to grow freely. In many years, rhubarb plants may struggle through summer hot spells to the point of near collapse, and then produce lovely new stems in late summer and fall. Late-summer rhubarb is infinitely edible.

How: After harvesting, cut off the rhubarb leaves. Cut the rhubarb stalks into uniform lengths and store in plastic bags in the refrigerator. To prepare rhubarb for use in recipes, remove long strings from large stalks, as you might do with celery. Slice the rhubarb into bite-size pieces, place them in a heatproof bowl, and cover with boiling water. Drain after 1 minute. This process removes excess astringency so that recipes don’t require quite as much sugar.

In late spring, after the plants show vigorous growth, watch for the emergence of huge flower clusters, and cut them off to keep plants from expending energy producing flowers and unwanted seeds.

Rhubarb is famous for producing too well, which is not a problem if you store the excess in a variety of ways. Rhubarb can be frozen, canned, or dried. Sugar is a major ingredient in most rhubarb recipes, but a few preservation methods require no sugar, such as drying small pieces of rhubarb to use in tea or freezing rhubarb juice to use as a lemon juice substitute.

Rhubarb is easy to freeze, with no blanching required. However, because rhubarb softens as it thaws, it is best to remove strings and have pieces cut the way you want them before you put them in the freezer. Freeze rhubarb on cookie sheets and transfer the frozen pieces to freezer-safe containers.

To save space, you can freeze unsweetened rhubarb juice, which can be used in place of lemon juice in hundreds of recipes. Cook chunks of rhubarb in just enough water to cover until soft, about 20 minutes. Mash gently with a fork. Strain the mixture through a strainer, and freeze the liquid in ice cube trays.

If you take warm rhubarb juice and mix it with an equal measure of sugar, you will have rhubarb syrup, which can serve as the base for many great drinks. Adding only a light splash of rhubarb syrup turns sparkling water into soda, or you can use it to make sweet not-really-lemonade or lemon tea. Freeze rhubarb syrup in ice cube trays, or can it in small half-pint jars. Process them in a water-bath or steam canner for 10 minutes.

In addition to canning versatile rhubarb syrup, many families treasure their homemade rhubarb-strawberry jam or rhubarb-ginger marmalade, which always turn out good because common recipes contain large amounts of sugar — usually more sugar than fruit. Strawberries, raspberries, or cherries bring a soft juiciness to rhubarb jam, and you can make rhubarb-and-berry jams using low-sugar pectin products.

Thin slices of rhubarb are fast and easy to dry in a food dehydrator. The dried rhubarb makes an excellent addition to herb teas by giving every brew a citrusy edge. And should you be making a recipe that calls for lemon and you have none, a few little nuggets of dried rhubarb can fill the need.

Candying rhubarb is a form of drying, and it is one of very few drying recipes that can be done in a warm oven that can be kept below 180°F (80°C). If you like sour candies, you will love candied rhubarb.

Unsweetened rhubarb juice can be used in place of lemon juice in hundreds of recipes.

Makes about 1 quart