The Yoga technique places central emphasis upon controlled breathing and related means of inducing apathetic ecstasy. In this connection it concentrates the conscious psychic and mental functions upon the partly meaningful, partly meaningless flow of inner experiences. They may be endowed with an indefinite emotional and devotional character, but are always controlled through self-observation to the point of completely emptying consciousness of anything expressible in rational words, by gaining deliberate control over the inner motions of heart and lungs, and finally, auto-hypnosis. (Weber, 1913, p. 164)

There are many reasons to include yoga in this book:

Expressed differently, body and mind are activated in resonance with each other, in a way that allows certain particular soulful states to emerge. For the yogis,1 posture, gesture, breathing, physiology, relaxation, mental concentration, and intellectual knowledge are dimensions that constitute an individual. The yogi of old knew all of these distinctions. For him, an individual cannot transform himself deeply without mobilizing these dimensions of human experience.

Indian philosophers have explored nearly every imaginable avenue of speculation.2 Although Yoga is already a particular trend of thought, it nevertheless includes a great variety of schools. Their common ground is a form of self-development that aims to commune with the dynamics of the universe.

The first known book dedicated to yoga is the Yoga Sutra of Patanjali, which appeared 2,300 years ago. The word yoga comes from the root word yuj, which peasants use to harness two buffaloes to a plow. Yoga is that mix of methods that permits an individual’s spirit to experience what links him to the Great All (Paramatma or Supreme Spirit) of which he is a part.3 These methods help an individual slow down the rush of thoughts and feelings that habitually distracts him, to create a space of tranquility and thus an experience of the winds of the universe that penetrate his organism and enliven him. Consequently, the individual experiences the welling up of a form of bliss that by far surpasses what reason can comprehend: “The aim was to harness ‘the powers of the human person (intelligence, activities of the senses, etc.) so as to master them and to access, beyond consciousness, spiritual states susceptible to rescue the soul (atman or purusa) from the “prison of the body”’” (Varenne, 1970, pp. 621–622, translated by Marcel Duclos).

I discuss, in the following sections, the hatha yoga that is known worldwide. Although the use of posture is only a part of that approach, its expertise on postural dynamics remains without rival, even today. Yogis assume that one needs a set of highly differentiated approaches to grasp and master the complexity of an individual human system. Thus, Iyengar identifies eight limbs of yoga4 that promote an individual’s quest:

For Bellur Krishnamachar Sundararaja Iyengar,6 these limbs are the pillars of a coherent method. If the practicing individual has not acquired an ethics that leads to yoga (1 and 2), he has a lesser chance to find the inner strength and enthusiasm to travel the arduous paths that lead to illumination (8). The practice of postures allows a yogi to train his body to hold a posture without moving for hours and without disturbing his attention (3). Once a posture can be sustained, it can become a bowl capable of containing the pulsations of life: the respiratory movements and the beating of the heart (4). The practicing yogi must then be able to contain in his spirit the forces that grow in him and further be able to enter into contact with the essence of the forces that animate him (5, 6, and 7).

Each limb designates a method that relates to a dimension of the human being. It is not only the combination of these methods that fosters an existential quest; it is also a certain internal alchemy that cannot crystallize unless the quest occurs in a specific spirit.

The yogis are aware of the unbelievable adventure that they propose and of the complexity of the task. For them, this total transformation of one’s being is not possible unless it is in a process that lasts millions of lifetimes. A psychotherapist can be inspired by yoga but his goals are clearly other. The psychotherapist aims at goals that are achievable within a few years at the most.

We can find this kind of vision in a number of Far Eastern schools, as in the writings attributed to the Buddha, such as in The Sutra on the Full Awareness of Breathing.7 It supposes that each dimension has its particularities and demands an approach adapted to these particularities. Gradually the devotee will learn to recognize the functioning of the dimensions within; he will find creative ways of living while sensing the heteroclite dynamics that animate him.

Yogis thus assume that there are many dimensions of the human being and that each has need of a different pedagogy. We can imagine that the individual is a house of many stories. Entering a school of yoga, the individual can participate in different courses that seek to develop a particular level. These courses are like scaffolding erected around an individual. Each level of the scaffolding is constructed in such a way as to be able to support the particularities of each story of the house. The scaffolding allows the individual to rearrange his structure, all the while following a number of developmental constraints (the function of the cellar is not like that of the roof). Similarly, a school acquires the experience relative to a type of scaffolding that sustains a certain type of transformation of the whole individual. This teaching thus acquires a relative coherence that corresponds to its own way of conceptualizing how the different activities necessary for the development of an individual (morality, compassion, body, physiology, meditation, etc.) can be coordinated.

There are a great number of religious and mystical movements that profess to liberate an individual’s essence from the body. Theories on “essence” vary from one movement to another. However, we do not need to enter into the multiple Hindu theories on this topic.

Yoga subscribes to this enterprise. Its originality is to have explored, in a particularly exhaustive way, the tools the body places at the disposal of those who attempt to influence the soul by voluntarily manipulating the bodily dimension.

The bodily methods of hatha yoga are centered on the notion of the postures, designated in the yogi’s vocabulary by the term asana. I do not know of another movement that has gathered such an extensive knowledge of what posture and respiration allow in terms of the transformation of a human being. Physical therapists, sports trainers, martial arts instructors, orthopedic surgeons, and psychotherapists continue to have confidence in this approach. They often recommend the postural and respiratory exercises of hatha yoga and of pranayama, independently from their original context (the eight pillars).

Hatha yoga does not use postures as they are used in everyday life. The yogis select postures that have an orthopedic relevance. These postures, like the gestures proposed today by a physical therapist, have nothing spontaneous about them. They are defined by criteria appropriate to their approach and theoretical principles.

When a researcher attempts to study the postural repertoire of daily life, he is confronted by an immense repertoire.8 The utilization of posture responds to such a varied mix of causes that today’s researcher is rapidly drowned by more data than he can manage. It is possible to propose a list of relatively stable postures observed in a given situation. To define the postural repertoire of a population would require so much work that the task has not yet been undertaken. The yogi’s solution to this dilemma, thousands of years before the invention of the camera and automatic data processing, was to focus on a restricted repertoire of postures. These postures can be held long enough to be observed and analyzed in detail. A practicing yogi can inwardly experience (through introspection) what is going on and can observe what happens when others use the same posture. The research then divides itself between the pupils and the masters. A pupil can learn to observe how he reacts to a posture, and thus form a personal clinical profile of how he functions. He notices that certain postures are more or less comfortable, more or less stimulating, provoke certain types of dreams, help when he has a headache, and so on. Given that a posture is static and that its configuration is consciously and explicitly observable, they can examine what a posture induces during long periods in their life and can find related constants. Pupils are also able to discuss among each other and compare their experiences. They can notice that a detail renders a posture more comfortable for everyone or interacts with respiration in a certain way. Some of these followers are also masters who discuss the results of their observations relative to a posture with their colleagues. Thereby, they attempt to understand general mechanisms that are not necessarily part of their personal experience, and also incorporate other forms of available knowledge into their discussions.

Hardly anyone takes a posture in exactly the same way, even one as simple as the “cross-legged position” (tailor’s position).9 A person tilts her head or keeps it straight, place hands on knees or on the thighs, may experience pain between the shoulder blades or in the hollow of the lower back, places his bottom more or less on the coccyx, and places the feet more or less near the genitals, and so on. Once we have observed the subtleties of a posture, the enormous number of variations is quickly evident, and the possible combinations reach astronomical numbers. Through the discussions with colleagues who gather the same type of data, the yogis slowly create a precise clinical approach relative to the links that can exist between one posture and the physical and mental dimensions of an organism, and on particular ways of constructing a posture.

Hatha yoga is both inspiring in its simplicity and powerful in its exploratory possibilities. Today, it is common in psychotherapy to build a knowledge base in this way from a practice. It is what we refer to as clinical research. This practical clinical knowledge is often included in theoretical speculations. Like psychotherapists, yogis have always tried to relate their practical knowledge to all the available information about the human organism. Yogis accommodate their knowledge to include what science discovers as much as possible; even if the practitioner does not always have the necessary expertise to integrate the most recent discoveries. It often occurs that yogis observe phenomena that the sciences have not yet studied or maintain a position with the assumption that further research will be needed. Scientists themselves know that their present formulations may be revised by future research.

I will now describe a typical meditation session, the way it is taught in the initial stages of meditation, by focusing on postural variables. I assume, here, that the person meditating is comfortably using the lotus (padmasana) posture. Most of my remarks also apply to someone who, because of a lack of flexibility, prefers to meditate sitting on a chair.

Sometimes, a moment will come when, like a deep-sea diver, the individual in meditation finally returns to the surface of his awareness. His legs are becoming numb, the blood circulates poorly, the tissues need more oxygen, and the joints need to move. To resurface, the individual follows a procedure quite like the diver who must return to the surface in stages so that the body can progressively re-accommodate to breathing like before, for his eyes to tolerate the surrounding light, and for his ears to be able to comprehend the words that someone will soon enough speak to him. One possibility is to bend an elbow again, move a few fingers, and then use them to repeat the alternating breathing exercises so that his physiology gradually accustoms itself to handling more oxygen. The individual is now able to auto-regulate to become active again. He opens and closes his eyelids repeatedly. At first, everything is blurred. He unfolds his arms and legs and stretches them. He also shakes them a bit to help restore the flow of blood to the extremities. To enter the meditative state, he paid attention to the setting and to himself. Now he retraces his steps as he rises, walks about, drinks something, and then gradually returns to his ordinary life.

In discussions with colleagues who regularly practice yoga, I came to realize that for them every chronic muscular tension is experienced as a chain that binds them to their passions and to those close to them. They assume that a chronic muscular tension that makes up the daily structure of the body is associated to affects that have become rigidly habitual. Hate directed at one’s parents becomes, for them, a tension maintained toward others, and consequently, a tie that the person tends to perpetuate. A person cannot relax his muscles without first having accepted to renounce an affective link to someone in his life. For the yogis, to relax the muscles is to liberate oneself from the emotional chains that bind a person to this earthly life and to others who hold him in a network of dependence and mutual demands. It is also to liberate his postural repertoire, and consequently to become capable of exploring all the postures a skeleton can adopt. To have access to all the postural repertoire of one’s skeleton is required to disinhibit all of the dimensions of the organism.17

This idea is taken up in almost all schools of body psychotherapy in the twentieth century.18 However, this notion has a different theoretical framework, because in psychotherapy, emotional ties are often valued. To paraphrase a famous distinction between Corneille and Racine, taught in most French schools: the yoga talks about man such as he ought to be; the psychotherapist talks of man such as he is. For Iyengar,19 a yogi renounces all that distances him from God or from the spirit of the universe. He renounces everything personal, especially his desires. Only the universe should animate an organism. The emotions create activations that block the influence of the “Great All” by linking the dynamics of the organism to interests that are mostly tied to human and social aims. While the yogi seeks a regular respiration, the emotions upset this equilibrium.20

Vignette on the turtle posture (kurmasana).21 The posture can be taken only by someone who has a highly flexible body. When a person gains the ability to hold this posture with comfort, and can maintain it for some time while breathing comfortably, the spirit calms itself and distances itself from all manner of sadness or joy. A person frees himself of anxieties caused by the fear and anger that controls his thoughts.22 The turtle posture creates an organismic context incompatible with emotional dynamics. The idea here is not that the yogis cut themselves off from their emotions, but that the emotions become useless, that they lose their relevance.23

To be able to take a posture like that of the turtle requires having gone beyond those thoughts that activate passions. This notion implies that the yogi no longer has thoughts and affects repressed into the Freudian unconscious. This point is often important for the psychotherapist who has a patient in front of him who has used hatha yoga to repress certain impulses more effectively.

It is customary to divide respiration into two series of mechanisms:

In body psychotherapy, the external respiration is mostly the focus of attention because it can be changed by the voluntary movement of the muscles. The body psychotherapist cannot directly affect the internal respiration, but he is mindful of it, for it has a great impact on the vegetative and affective dynamics. However, these internal interactions are for the moment not well understood, or more specifically, not sufficiently understood to allow an explicit handling in body psychotherapy.

The breathing exercises in yoga form the discipline of pranayama. They use hatha yoga to modulate the external respiration and call the effects of internal respiration on the organism, prana. Prana designates metabolic operations that remain difficult to explain as long as we do not have a full description of the impact of internal breathing on the organism, on affects, and on the vitality of the mind. The body psychotherapist of today has but a simplistic vision of what is described by the Hindu theories of prana, which has been associated with magical and alchemical properties. It is probable that some of these magical properties will be “revisited” by tomorrow’s scientists.

In spontaneous respiration, from being at rest, inspiration stretches the muscles of the torso in a way that can be likened to an elastic that we stretch. It is therefore an active movement. Breathing out is the passive reaction of this elastic once we release it. The muscles that are mobilized for respiration thus return to their initial tone.

In a breathing exercise that is found in most body-mind methods, the therapist asks the patient to let the thoracic cage and the abdomen drop during exhalation as if one were letting go of a stone. This letting go during exhalation is impossible for someone who is tense or anxious. Chronic muscular tension raises the level of the basic muscle tone. As the muscles are less elastic, the variations in respiratory volume are limited.

The relationship between anxiety and the inhibition of respiratory activity is a good example of what I mean when I speak of a robust ancient knowledge about mind-body phenomena. I do not know if all anxious people have a troubled respiratory function, but the correlation is frequently observed. It has since been confirmed by most practitioners who have not waited for scientific research to use breathing exercises to reduce anxiety. The important point for body psychotherapy is the observation that an emotion is, among other things, a breathing pattern.

It is only recently that researchers confirmed the existence of a correlation between respiratory problems and anxiety.24 The detailed descriptions provided by these researchers confirm the descriptions given by yogis and acupuncturists, as well as the impact of respiratory problems on almost all of the functions influenced by the vegetative regulatory mechanisms (circulation of the blood, sudden weaknesses, etc.). It is interesting to note that respiratory exercises can relieve anxiety for a moment, but only rarely provide a lasting modification of the connection between anxiety and the respiratory constriction. Yogis and Buddhists knew that anxiety is also caused by a way of thinking, a way of managing one’s affects. We still need more information on the complex mechanisms that influence the link between anxiety and breathing so that we can improve our way of working with respiration in the treatment of affective disorders. The difficulty is that once a physiological mode of functioning embeds itself in a stable organismic dynamic, it becomes difficult to change it. Body psychotherapists developed new methods to work on the emotional mechanisms that connect anxiety and breathing.

Try this: at the end of the next out-breath, just wait for the following in-breath to occur—as though you were a cat waiting for a mouse to emerge from its hole. You know that the next in-breath will come, but you have no idea precisely when. So while your attention remains as alert and as poised in the present as that of a cat’s, it is free from any intention to control what will happen next. Without expectation, just wait. Then suddenly it happens and you catch “it” breathing. (Batchelor, 1997, p. 95f.)

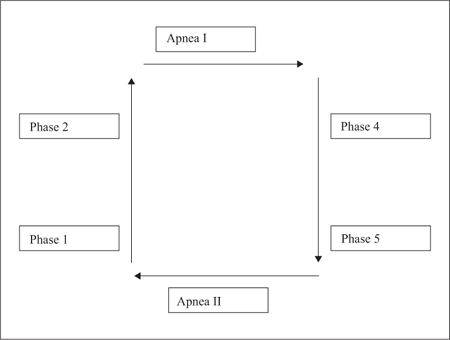

Besides exhalation and inhalation, yogis are very attentive to the apneas that separate breathing out from breathing in, and breathing in from breathing out. Finally, it is customary to distinguish thoracic respiration from ventral respiration. The first relates to the impact of the movements of the lungs on the rib cage, whereas the second relates to the impact of the movement of the diaphragm on the viscera of the abdomen. This leads to the basic schema shown in figure 1.1, which is utilized in many cultures.

THE TOPOGRAPHIC DIAGNOSIS OF RESPIRATION

The topographic diagnosis of respiration, based on the schema in figure 1.1, presents an analysis of respiration according to the degree of utilization at each phase. Certain diagrams are more refined, distinguishing, for example, the top and bottom of the thorax. Few persons utilize these six phases all the time. To propose a relevant respiratory diagnosis, the therapist takes note of the duration and the amplitude of each phase. This analysis sometimes changes when a person is either lying down or standing, or engaged in different kinds of activities. This type of diagnostic distinguishes above all between individuals who breathe mostly with their abdomen from those who breathe mostly from the thorax. It is generally recognized that the persons who breathe only from the thorax easily become affectively labile and overstimulated. The explanations of this relationship are rarely convincing, but the correlation is sufficiently robust. Most of the approaches to respiration recommend, above all, verifying that there exists a good ventral respiration that expresses a minimum functioning of the horizontal respiration (top ↔ bottom when a person is standing) of the lungs and a flexibility of the diaphragm. Typically, a citizen25 has a diaphragm that is only relatively mobile, to which voice teachers will attest. These deviations from the ideal norm are not necessarily pathological. Full breathing exercises demand that a person attempt to take in and let out as much air as possible. They make it possible to evaluate the degree of adaptability of the respiratory schema to demanding situations on the organism. The therapist, for example, asks a person who breathes mostly from the abdomen what is going on when he also breathes from the thorax.

FIGURE 1.1. The moments of respiration. Phase 1: Inhalation by the ventral segment. Phase 2: Inhalation by the thoracic segment. Phase 3, Apnea I: The duration between inhalation and exhalation. Phase 4: Exhalation of the thoracic segment. Phase 5: Exhalation of the ventral segment. Phase 6, Apnea II: The duration between exhalation and inhalation.

Another important element of a topographic diagnostic is the distinction between ventral, dorsal, and lateral respiration. Respiration that is visible on the front of the body is common to everyone. Fewer people have a respiration that visibly mobilizes the back. Still fewer have a respiration that mobilizes the sides of the rib cage other than in moments of breathlessness.

Most of the body psychotherapists who work with breathing make these distinctions. Typically, the mobilization of the dorsal respiration permits the patient to regain contact with an impression of strength, whereas the mobilization of the lateral respiration can help a person experience containment and calm.

DYNAMIC RESPIRATORY DIAGNOSTIC

The term dynamic refers to the unfolding of a mechanism in time. A dynamic analysis of respiration is based principally on the observation of the following two dimensions:26

It is useful for this kind of analysis, and especially for the observation of the diaphragm, to distinguish between spontaneous and voluntary respiration.

APNEAS AND RESPIRATION RHYTHM

One of the well-known characteristics of yoga is its work on the apneas. These moments of transition are often set aside in the body practices based on the information from anatomy and physiology, as if they were without importance. For a yogi, these moments are crucial. It is mostly at those moments that the mind can introduce a lever to master not only the rhythm and the volume of the external respiration but also the vegetative coordination that exists between the emotions and the internal respiration. By concentrating on these phases of transition, yoga facilitates the acquisition of a certain voluntary mastery of affect. It is at that moment that a yoga exercise becomes effectively a yoke that can master the body-mind connection.

Vignette on the mastery of the breath. In the Ujjyayi Pranayama, Iyengar27 proposes to explore what goes on when we breathe in as deeply as possible with the thorax, while pulling the abdomen back as close as possible to the spinal column. Once inspiration is complete, the pupil explores what is going on while holding his breath, keeping the air in the organism for a few seconds.

This is an example of respiratory retention, currently utilized in the practice of pranayama. Those who are following yoga classes in Europe will notice that they work mostly on the retention after inspiration. By contrast, those who practice tai chi chuan may spend more time exploring what is going on between exhalation and inhalation.

If we observe someone’s spontaneous respiration, we notice that these moments of transition take more or less time, varying from person to person and in function of circumstances. In a state of relaxation, my patients have the tendency to move rapidly from inhalation to exhalation (the release of the elastic), while the move from exhalation to inhalation spontaneously lasts longer. This moment of transition can be experienced as an end of respiration by a person who is not familiar with this kind of work. But the very reason that yogis work on these transitions is that these are moments of intense physiological and psychological activity.

One of the aims of pranayama is to slow down the rhythm of respiration by lengthening the four phases of the respiratory rhythm. According to Iyengar,28 a person has about fifteen respirations per minute.29 This rhythm accelerates in the case of indigestion, fever, a cold or a cough, or in conditions such as fear, anger, or desire. Anxious people often have a restrained but rapid respiration. Certain yogis think that the number of respirations a person can have in a lifetime is determined; consequently, the slower the rhythm, the longer the person will live. Sensory and instinctual activity activates the respiratory rhythm, while detachment diminishes it. Finding a lifestyle that is in synergy with the requirements of metabolic dynamics allows one to live with an even slower respiratory rhythm. This analysis is compatible with those proposed in a text on physiology (Bonnet and Millet, 1971, pp. 305–306) for adults. For children, the younger a child the more rapid the respiration (forty-four breaths per minute on an average for newborns).

In my practice, persons who observe their respiration think spontaneously like yogis. When they lie down for a relaxation session, they sense that something is not well when their breathing is rapid, superficial, and brief. When the exercise begins to have effect, they sense that their breathing is spontaneously deepening and slowing down. At that moment the diaphragm relaxes and the person yawns, and sometimes stretches.30 In general, the people who come to see me have never found it useful to think about their apneas. To become attentive to what is going on within them during spontaneous apneas is often, for them, an amusing, even intriguing, discovery. Once they have learned to observe this aspect of the respiratory rhythm, they notice that during their relaxation, these moments also lengthen. For certain individuals, the slowing down is mostly marked during one of the two apneas; for others, it is during both.

Internal respiration begins when air leaves the lungs to enter the arteries. The red blood cells carry the oxygen to nourish cellular activity in the whole organism, and bring back the carbon dioxide to the lungs. Somehow this dynamic also influences affects in a multitude of ways. The impact of internal breathing on moods and needs was already known by yogis centuries ago.

Three gases are inhaled and exhaled (average values):

The composition of the air inhaled and exhaled is thus grossly the same. Everything turns on an exchange of about 4 percent oxygen and 3 percent carbon dioxide.

The inhaled oxygen bonds to the iron atoms contained in the hemoglobin molecules that circulate in the arteries. Oxygen makes up about 20 percent of the volume of the arterial blood and 12 percent of the venous blood. The capacity of the blood to contain oxygen can easily double, but that happens very rarely. Carbon dioxide, transported mostly by blood plasma, makes up 50 percent of the plasma’s volume. Four percent of CO2 in circulation is freed through exhalation. The remaining amount is indispensable for the functioning of the internal respiration.

The issues linked to the ratio of iron in the blood introduce the concept of intermediary mechanisms. The more iron atoms in the blood, the more the blood can transport oxygen molecules. When the ratio of iron in the blood diminishes, the ratio of oxygen also inevitably diminishes. Respiration can then no longer respond to the demands of an increase in physiological activity, even when there is an increase of respiration and cardiac activity. Because the problem is not caused by the lungs or the heart but by a lack of iron, the organism soon finds itself in a crisis. If a physician gives a supplemental iron injection, and if the iron attaches well to the hemoglobin, the problem resolves immediately. The main causes of iron deficiency are poor absorption of iron by the body, inadequate daily intake of iron, pregnancy, blood loss due to heavy menstrual bleeding, or internal bleeding. Too much iron in the blood causes other problems.31

The equilibrium I have just described is important for the metabolic activity of the organism. For example, it is influenced by the energy sources utilized by the activity of the organism (sugars, proteins, or fats). This is an example of interaction between respiratory behavior and the dynamics of metabolism. The fatigue experienced by individuals who lack iron is an example of conscious awareness activated by physiological regulatory mechanisms of the organism.

Physiologists know that internal respiration is not a globally structured phenomenon but a multitude of operations that can be analyzed in many different ways. These operations take in oxygen and release carbon dioxide. They participate in the process through which these two molecules are distributed in the organism. These mechanisms are consumers of energy more than organismic regulators. They do not consume oxygen to produce carbon dioxide. They are content to carry out their mission utilizing their environment as a source of supply and as a means of waste disposal. Some global physiological mechanisms, like venous circulation, then gather the excess amount of carbon dioxide to expel it from the organism, notably through external respiration (exhalation) but also by other avenues like perspiration.

This introduction to internal respiration is also an introduction to the notion of prana. I do not know what the Hindus knew relative to internal respiration,32 but the yogis had observed, clinically at least, that respiration intimately influenced all of the physiological mechanisms of the organism. Prana is this dynamic interaction between respiration and the physiological mechanisms. Their theories were based on whatever knowledge and philosophical speculations were fashionable at a given moment. This explains why they sometimes appear folkloric and magical to some physiologists. What is astonishing with regard to the theories about prana is the extent to which the intuition of the yogis is fundamentally correct, in the measure in which they perceived how breathing had a profound impact on the dynamics of the organisms, moods, and thoughts. The yogis developed, in the course of the centuries, an impressive number of explicit techniques, capable of having foreseeable effect on this nebulous group of mechanisms that they called prana.

Yogis have developed refined ways of influencing the dynamics of the prana; yet most body psychotherapists who want to influence internal breathing tend to use only simplistic and rudimentary methods. Here are some points of reflection that highlight the minimum knowledge that a body psychotherapist ought to have on this topic. He will rarely find more information than this in the various textbooks dedicated to his profession.

THE EXPERIENCE OF RELAXATION

When a breathing exercise is correctly prescribed and well accepted, all those who practice it speak spontaneously of an intensification of body sensations (tingling, pins and needles sensations, warmth diffused throughout the body), a feeling of relaxation, and an impression of having become denser, more coherent, and more together. The power of this impression explains the importance accorded to internal respiration that has, as its first function, the maintenance of the vitality of the cells of the organism.

HYPERVENTILATION AND THE CRISIS OF TETANY

Hyperventilation occurs when the organism stores more oxygen than it spends. At that moment, the ratio between oxygen and carbon dioxide is not what the organism expects. At a weak level, this imbalance can activate an agreeable euphoric state. When it becomes stronger, it leads to a crisis of hyperventilation. During such a crisis, people complain of rapid and superficial respiration, an oppressive thoracic sensation, and suffocation.33 Some people experience a muscular tetany, with a sharp flexion of the wrist and ankle joints. Such a crisis accelerates the pulse and abruptly lowers arterial pressure. It can provoke buzzing and hissing in the ears and cramps (typically in the hands). Tetany is probably due to some modifications in the dynamics of the acids in the blood and the muscles.

One reason some therapists propose exercises that lead to hyperventilation is that it can sometimes provoke states of regression during which a person’s psychological defenses are weakened and unconscious content activated. When this happens, the patient becomes aware of past experiences that were repressed. Those regressions can be powerful and lead to an intense experience. In reliving such experiences, a person sometimes learns to no longer fear profound emotional experiences.

When an individual voluntarily hyperventilates for two to three minutes, we observe an automatic sequence (that cannot be controlled voluntarily) that William Francis Ganong calls periodic respiration.4 While holding her breath, the person experiences prolonged apnea. This moment can be experienced as an ecstasy by some, as panic by others, and as a mixture of both by the majority of people. When the person breathes spontaneously again, it is at first in a rapid and superficial fashion. One can then observe an oscillation between a phase of rapid breathing and apnea repeating itself several times, for not more than ten minutes:

If body activity stays the same, an increase in breathing will increase the rate of CO2 diffusing from the blood into the lungs. This can cause the CO2 concentration in the blood to fall, which will cause the acid level of the blood to drop, and its pH will become alkalotic (too alkaline). . . . When the pH exceeds 7.60, hyperventilation tetany takes place. If breathing is depressed, CO2 concentrations in blood will rise, causing the acid level to rise and the pH of the blood will become acidic. (Caldwell and Victoria, 2011)

Gradually, the respiration returns to its habitual dynamic.

The drawbacks of such a method of self-exploration are important. First, the euphoria resulting from such exercises often renders individuals dependent on the therapist with whom this experience was triggered and on the method he used. Then, with the momentary lowering of the defense system, individuals can become aware of affects and memories that they are unable to integrate, especially if they are intensely relived. Such an experience can be traumatizing, and generate a form of retraumatization during therapy. Finally, in the case of impulsive personalities, the experience of boundaries diminishes dramatically. They no longer fear that expressing what they experience can become dangerous for them and their entourage. For these reasons, most schools of body psychotherapy avoid using these methods or use them only in specific cases.35

It is difficult, in such instances, to sort out memories from fantasy, delusions, and hallucinations. They are often intermingled. Some psychotherapists have an excessive confidence in the material imagined in such states and may even suggest to the patient that all that is perceived is true. This attitude has proven itself dangerous, because the patient is inclined to reorganize himself on the bases of an unfounded belief.36 The case in point is that of individuals who reconstruct their self-understanding on the belief that they suffered from abuse in their early childhood or in a past life when nothing of the sort existed.37 The proper manner to use this material, sometimes available in abundance with this method, is to explore if the same material can be found through other methods (e.g., dream analysis) and take it up anew. Therapist and patient can then separate out what is remembered, what is delusional, what is a blend of both, and what is impossible to evaluate.

When a patient hyperventilates, it is better for the psychotherapist not to worry about it. Such crises tend to subside. It is essential to stay present with the patient in a reassuring and containing manner while he is going through it. There is usually no hyperventilation if the patient spends the energy taken in through inhalation by moving and speaking. If the patient’s hands take on the characteristic position that announces a crisis of tetany (fingers are hyperextended and touch each other while getting closer to the interior of the wrists), the therapist can encourage still more movements and more vocalizations to use up the excess oxygen.

PEOPLE WHO ARE EASILY IN A STATE OF OVER-OXYGENATION

Each organism has a particular way of associating metabolism and respiration. This association also varies in function of one’s lifestyle. Certain individuals therefore hyperventilate more easily than others. The hypothesis is that the more an organism can utilize a large quantity of oxygen, the more active it can become. This notion suggests that breathing exercises influences physiological resiliency. The neo-Reichian psychotherapists have also observed that, at least in some cases, reducing the quantity of oxygen one lives with is a way of reducing not only one’s vitality but also the intensity of one’s needs and affects.

In my practice, I have observed that some patients who breathe poorly grew up in an early environment that could not integrate the activities and demands of infants and little children.38 In the two schools (psychotherapy and yoga), for different reasons, practitioners work with the assumption that such individuals should learn to tolerate more oxygen to reinforce their physiological and affective vitality. Modifying the balance between a vast numbers of heterogeneous mechanisms without creating undesirable secondary effects is a complex business. Therefore, a process that wants to support the accommodation of physiological processes to a greater quantity of oxygen requires time and regularity. Time is necessary not only because regular practice is required to change the dynamics of organs but also because the therapist needs to calibrate the exercises he proposes in function of the patients particularities.

Certain ways to measure out overoxygenation via exercises can have complex implications for psychophysiology, notably in the modulation of the concentration of the neurotransmitters in the organism,39 the composition of the blood (the diaphragm is also a pump for the venous blood of the legs), and the nervous system. The rapport between the hormones and the respiration is so rich that Tarja Saaresranta and Olli Polo (2002) have even proposed that the studies of this topic form the discipline of respiratory endocrinology. For the moment, this research mostly shows how the hormones influence respiration, but—cybernetics duly noted—this implies that respiration is included in the regulatory systems of the hormones, which is also responsive to the functioning of respiration.40 It is therefore possible to relate effects of respiration to a cascade of chemical implications that diffuse themselves throughout the body.

Having said this, the recent knowledge on the influence of oxygen on the metabolic activity does not explain all of the phenomena associated with prana. Expressed differently, the clinical impression of the Hindus, concerning the relationship between their way of handling respiration and certain physiological phenomena, can be empirically sound. But that does not imply that their explanation is sound.

The yoga based on the sequence of static postures, taught by masters such as Iyengar, is the one the world knows best. There are other types of yoga. One of them is tantric or bhakti yoga, developed in the Himalayas.41 One of its particularities is a way to “let oneself go” (prapatti), which allows one to free oneself from all imaginable ties that an individual might establish with what surrounds him. In this way of thinking, sexuality and emotions are those human forces that permit an individual to experience the other, to abandon oneself to the forces that surround us all, and to submit oneself (seva) to the divine forces to be able to join with it.42 This school often uses techniques in which chant, dance, and trance allow the individual to feel enlivened by divine forces and unite to them. The tantric exercises sometimes utilize sexual intercourse. Men must become capable of refraining from ejaculating even during orgasm. The mastery of the breath that characterizes pranayama is also part of these practices.

The fact that there are tantric schools in many parts of the world indicates that it is almost as easy to be in a trance as to be hypnotized. A trance can be induced by a series of exercises that one can learn in a few days during a course or workshop. It often suffices to approach these exercises with curiosity, without becoming irritated by what is proposed. The fact that such states can be reached so easily demystifies the impression that a trance is a bizarre phenomenon. Just as there are persons who resist hypnosis, there are some who resist a trance.

Hindus gave a lot importance to the spine. The spine links the segments of the body and makes it possible for the central nervous system to coordinate gestures with thought. The spine is the axis of all the postures. A yogi’s spinal column can be as strong as a tree trunk and as flexible as a snake. They have developed highly effective massages of the spinal column, and hatha yoga always takes into account the interests of the spinal column. Because of its key function, yogis have situated the power that can animate the body and coordinate its segments at the base of the spine. They call this force the kundalini. It is an affirmative and sexual force, which leads to a form of sexual arousal mobilized by tantric yoga. To feel one’s kundalini is to feel a powerful, warm, and agreeable current rise up the spinal column from the coccyx to the crown of the head. This form of arousal is deemed so powerful that it can activate an involuntary movement of the spinal column that undulates like a snake. This movement of the spine engages the entire body in a global movement that goes from the feet to the head and activates a trance state. The body acquires an autonomic dynamic that mobilizes the resources of the organism independent of volition. The follower needs the containment of a group and a master to maintain a certain mastery over what is happening. At the beginning of a tantric process, the kundalini is like a sleeping serpent, wrapped around itself in the coccyx.43 This notion is included today in a more or less central fashion in the teachings of the majority of the schools of yoga.

Body psychotherapists know well the sensation of warmth that rises up the back when a patient rocks back and forth many times on his bottom, sensing the movement of the spine. This phenomenon is close to Wilhelm Reich’s Vegetotherapy method to elicit an orgasmic reflex. One’s gaze becomes clearer and one’s back more tonic while more relaxed. Thus, body psychotherapies often use the term kundalini to describe this phenomenon because they do not have a better one.

The model of the chakras is also used by many schools of body psychotherapy.44 It is a model built on the centers of every segment of the body coordinated by the kundalini. The flow of the kundalini must pass through a number of psychoorganic “doors” before being able to freely circulate the length of the spine and set the organism in an ecstatic trance. These doors, which are often closed when a student begins his yoga practice, are called chakras. According to many authors, these chakras are represented by wheels or flowers situated on the back, superimposed on the spinal column, or on the front of the body, parallel to the spine. We are thus very much in a segmental approach to the body because the front and the back of the body are linked to a chakra. The number of these wheels and their symbolism varies. Iyengar prudently mentions ten principal chakras.45 The most often mentioned are the following:

I present this list only as an example, because the literature on the segments is extremely varied. Iyengar wonders whether these zones might correspond to the endocrine glandular system that regulates the major movements of the organism.

To awaken a chakra, the devotee must be able to move the designated area of the body in coordination with the respiration, associated affective mechanisms and mental representations. When all of these can be vividly integrated, the disciple moves on the next door. Once two doorways have been opened, the metaphor of the snake is there to remind us that each door refers to a psychoorganic whole, and that the coordination of the segments must acquire the same continuous grace as that of a cobra that dances vertically to the sound of a flute.

You may try and see how difficult it is to get the spinal column to move like a serpent while you breathe comfortably for ten minutes. We often find this type of movement in dances from around the world.