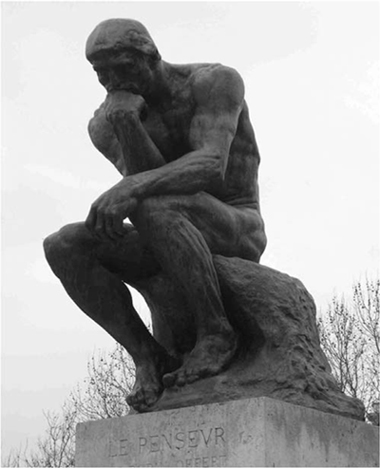

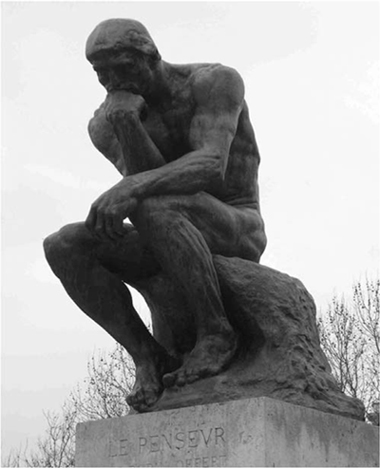

FIGURE 13.1. Rodin’s sculpture The Thinker. Source: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Rodin_le_penseur.JPG.

The Awareness of my body is not the awareness of an isolated entity or “block,” it corresponds instead to the knowledge of a postural schema, it is the perception of my body’s position in relation to the vertical, the horizontal, and to certain important axes of the environment’s coordinates in which my body is embedded. (Maurice Merleau-Ponty, 1967, Les relations avec autrui chez l’enfant [Relating to Others during Childhood], p. 23, translated in Rochat, 2010)

Up to now, I have described the organism as a closed system, a system of diverse dimensions that interact with each other in different ways. Such an approach of the individual is often useful during a body psychotherapy session. I have already showed in many places that the organism is in fact an open system. It is regulated by internal and external exigencies at the same time. The body psychotherapist must often switch from one vision to another. At one moment he needs to focus on how dimensions interact within the organism, and then on how dimensions interact with the external environment of a patient. The postural dynamics model that I describe can be used when one needs to coordinate these points of views.

To open this discussion, I show how three dimensions of the organism can be discussed when they are considered a subsystem of an open system:

In each of these cases, we observe the following factors:

I now illustrate the relevance of this model by showing how posture plays its role of interface between the organism and the environment. In gymnastics, the instructor explains to the consciousness of the student what he must do with his body and how he must listen to his body’s messages. In other words, the teacher gives instructions to the mind of the student. He then observes how these instructions are played out by the body. In ordinary life, things happen quite differently. The organism accumulates millions of postural habits that are automatically set in place. One way to characterize the social rituals is to indicate the postural repertoire that they create. To conform to a ritual is to accept a certain observable behavior, independently of what we think of the ritual. In the period of slavery, such body dynamics induced by society were inculcated by whippings. Today, the cultures generated by the economic markets have found even more effective ways to oblige everyone’s organism to act in certain ways. In all cases, the habitual postural dynamics structures, in parallel fashion, both the environment and the dynamics of the organism. Posture as an interface obeys the laws of modularity and parallelism. I can, in effect, have to adapt myself simultaneously to the customs of an enterprise and the particular requirements of an interaction with a colleague and the exigencies an ambient temperature imposes on me, and so on. At the same time, the dimensions of my organism react differently to all the stimuli that influence my organism and impose their own requirements (my health, my affects, my habits, my skills and particular interests, etc.) on how I act and react. All of these variables, all of these links, have their own proper ways to function and are set in place in a nonsequential manner. My hand does not wait to know what I think of my colleague to wave hello when he sits down in front of me.

The goal of the following sections is to give to the body psychotherapist tools for evaluating the postural behavior of his patients. He will be able to use the tools of the biomechanics of the body to understand its impact on the other dimensions of the organism and the communication strategies to which the posture participates.3

Think of throwing a ball. The arm gesture and the body adjustments that carry the arm gesture are generally merged in a well-coordinated athlete. They start and stop together, or flow smoothly into one another. Someone who has never thrown a ball will, at first try, have moments where only gesture or only posture is in motion at a given time. The act looks clumsy. (Daniel Stern, 2010, Forms of Vitality, p. 87)

A contemporary way of analyzing a body is to dissect it into segments, and then observe how these segments coordinate within the gravity field. Posture4 is the organization of the body’s segments in the space of gravity. Each cell of the body, each fluttering of an eyelid and the cardiac rhythm, are under the pull of gravity: a force that draws everything that exists on the planet toward its center. Posture allows for the organization of relationship that establishes itself between gravity and subsystems of the organism.

The segmentation of the body varies from one school of thought to another. The division depends on the way that the body is analyzed and the bodywork that is envisioned. Nonetheless, most of the body-focused methods include the following distinctions in their analysis:

Gravity is a very attractive force, and everybody is constantly exposed to its influence. The pull of this force makes us all stay on the ground. It even tries to pull us under the ground. But fortunately there is another force in us which does not permit that. That is energy. (Charlotte Selver, “Gravity, Energy and the Support of the Ground,” 2009)

Rodin’s The Thinker (figure 13.1), will serve as an example to describe for you how to analyze the architecture of a posture which is comprised of three main subgroups:

FIGURE 13.1. Rodin’s sculpture The Thinker. Source: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Rodin_le_penseur.JPG.

In The Thinker, all of the segments of the body are in either basic posture or auto-contact posture. There is consequently no other parts of the body to interact with the objects and the persons that surround The Thinker.

The principal functions of the posture are:

The analysis of a posture distinguishes two types of surfaces that make it possible to situate the parts of the body that participate in the construction of a posture:5

1.1. The parts of the body that transmit the greatest amount of body weight to the support surface form the anchoring point. When a person is sitting down, the principal anchor point is the pelvis. The anchor point defines how the body’s is grounded in methods such as Alexander Lowen’s Bioenergetic analysis.6

1.2. The pelvic angle is the angle formed by the trunk and the thighs. It is a determining factor to differentiate the postures. In the vertical positions, it is at 180°, but in the squatting and sitting positions it oscillates in the vicinity of 90°.

2.1. These parts of the body transmit the weight of one segment of the body to another segment that transmits this weight to the basic posture. This aspect of the auto-contact thus forms a secondary system in the mechanisms of regulation of the organism in the gravity field, as is so well illustrated in The Thinker. The Thinker is sitting down, leaning forward, both feet on the ground. This is his basic posture. His auto-contact posture includes many segments of the body. The weight of the head is carried by the right fist, which touches the chin. The right elbow transmits the weight of the head and the arm to the left thigh. The left forearm also rests on the left thigh, which makes it such that the weight of the upper body (from the head to the hands) is transmitted to the left thigh and then to the left foot. If The Thinker were standing up straight, the weight of the upper body would have been transmitted by the back to the pelvis and from the pelvis to the feet. Here, the work of the back and of the pelvis is lightened.

2.2. The auto-contact surface also participates in the physiological auto-regulation (especially vegetative) of the organism. For example, the posture of Rodin’s Thinker leaves less space for abdominal breathing than a posture that would maintain his thorax in a vertical position.

The basic posture forms the ground floor of a body structure; the auto-contact surface forms the other floors. The whole of the behaviors that seek to manage objects and persons with fine motor skills forms the surface of the posture, or the surface posture. To be able to play the piano for a long time, the musician must first master his basic posture so that his arms and hands might be able to interact with the piano with as much freedom as possible. This freedom supposes two postural functions:

Musicians know this dynamic between posture and gesture very well. To regulate the postural background of their fine motor activity, they often take courses in proper posture and carriage, which helps them master this dynamic. Violinist Yehudi Menuhin, for example, mostly used yoga, which he learned from the yogi Iyengar who is often quoted in chapter 1 on hatha yoga. Another technique frequently used by musicians is the method created by Australian Mathias Alexander at the beginning of the twentieth century.7

There is a relationship between the increase of the surface of contact, the increase in the number of centers of gravity, and relaxation. Consider the two most extreme examples, standing and lying down.

The choice of a basic posture, especially an anchor point, regulates two dimensions:

These examples show that even if the basic posture is rarely mentioned in psychotherapeutic writings, it is at the center of the central dynamics that characterize a therapeutic technique.

The notion of repertoire is rarely used in the human sciences and body psychotherapy, yet this tool facilitates the characterization of a set of practices in a particularly useful way.

The repertoire of a language is its vocabulary. The vocabulary of the French language is the collection of the terms accepted by the Académie Française. Most other European languages leave it up to dictionaries and custom to decide if a word is part of the language. We can contrast this linguistic definition with a cultural definition: the French vocabulary is the collection of the terms used by at least 50 percent of the people living on French soil.

Similarly, it is possible to distinguish two repertoires of the body associated to the French culture:

These are two different ways of defining the repertoire of gestures used in France. Some gestures (and a number of persons) are included in both repertoires; others would fit more strongly in one or the other.

Some postures are more often observable in certain countries than in others. Therefore, a postural repertoire is defined in function of two anthropological analyses:

We can observe a person who crouches in France and in India, but the probability of seeing a person actually squatting is higher in India than in France. In France, there is a greater probability of seeing a person crouching in a yoga studio than in a restaurant. Similarly, the postural repertoire that we observe in a school of hatha yoga in India is different from the one we would observe on the streets of Bombay. This time the differences are more subtle, given that the members of the yoga school in Bombay are also part of the population of the city. It is also possible to talk about a person’s repertoire of gestures, or of that person’s postural repertoire in a given situation. The behavioral repertoire of a child is not always the same with its mother, with its father, or when they are all together. The child uses different behaviors in each of the three situations. Some are used more often with the mother than with the father, and some are used with the father when the mother is not present. These variations in repertoires form the dynamics of an individual repertoire.

Some postures are considered universal, but it is not known whether they have the same function when the repertoire of which they are a part varies. Thus, being seated in a chair does not have the same implication in an office, on a throne, in a reception hall, or in a theater.

Physical therapists have tried to establish rules to analyze the functioning of a healthy body that are close to the definitions used as guides in orthopedics to repair a broken body. The reference body is the one described in an atlas of anatomy. The spinal columns are impeccable, the tones of each muscle are organized like the strings of a violin at the start of a concert. No deformity comes to trouble the idea that the human body has been planned by an engineer-god. This state of the body is often proposed by the schools of gymnastics.11 I use the concept of Max Weber’s “ideal type”12 to indicate this way of thinking about a healthy body.

Vignette on muscle tone. So Buddha went to the new monk and told him:

“I have heard that when you were a king you were a great musician, you used to play the sitar.” “Yes, but that is finished now, I have forgotten about it. That was my only hobby, I used to practice at least eight hours per day and I had become famous for that.”

Buddha said: “I have to ask you one question: if the strings of your sitar are too tight, what will happen?” He said: “What will happen? It is simple! The strings will break when you will attempt to play.” “Another question,” Buddha said. “If they are too loose, what will happen then?” “If they are too loose, no music can be produced on them, because there is no tension,” the answer came.

After this Buddha said: “You are an intelligent person—I need not say anything more to you. Remember, life is also a musical instrument. It needs a certain tension, but only a certain one. Less than that and your life is too loose and there is no music. If the tension is too much, you start breaking down, you start going mad. First you lived a very loose life and you missed the inner music; now you are living a very uptight life—you are still missing the music!13

This anecdote is a good way to introduce the notion of muscular tone. Each muscle would have its own degree of appropriate tension, called tone. The tone, like the well-tuned sitar, implies a certain stretching of the muscle. The muscles can become hypertonic (too hard too short) or hypotonic (flaccid and deformed).

Physiotherapists have a full array of models that describe body movements that are automatically (orthopedically) healthy and can be assimilated into ideal types of relations between physiology, body, and behavior. In the appendix dedicated to postures, I give some examples of sitting “correctly” on the ischia bones of the pelvis and the alignment of the body segments of a person standing according to the “plumb-line rule.”14

Conflicts become an inherent component of the phylogenetic equilibrium of the subject, because it is intrinsic to the “human condition” which determines the functional architecture of a human organism. (Guy Cellérier, 2010, Postface, p. 131; translated by Michael C. Heller and Marcel Duclos)

An individual who wants to understand how a skeleton, the muscles, the fascia, and the ligaments are coordinated can easily arrive at the conclusion that symmetry is the basic rule of the organism. On the other hand, as soon as this person includes the functioning of the organs into his observations, he will have to admit that there exists a manifest heterogeneity between the body system and the organ system. Some organs respect the rules of symmetry (the brain, lungs), whereas others are clearly asymmetric (heart and liver). To this, we have to add the functional asymmetry imposed by some organs, like the brain, which makes most of us either right- or left-handed. This differentiation implies a different calibration of the sensory-motor circuits and of the development of the muscular mass. The necessity to create modes of bodily compensation to integrate the asymmetry imposed by the organs is therefore a necessary part of the requirements that the physiologic dimension imposes on the body. The result is that most of the human bodies are more or less asymmetrical while the comfort and the health of the body seek symmetry. The health of the organs also imposes requirements on other dimensions, like the respect of the demands of the metabolism. Here are new conflicts of interest between the dimensions. Especially when the social environment provides for an ample supply of water and nourishment, behavioral and psychological propensions do not respect metabolic needs. They tend to take more. Everything happens as if the homeostatic mechanisms operate according to the following rules:

The yogi can only transform himself by remaining at the margin of social life. He would not be able to loosen all his joints in a more stressful environment. The citizen is someone who accepts that his body adapts itself to a lifestyle, to the demands of a culture, a profession, and the role of a parent. It seems that every form of adaptation has a price. The yogi pays a price constructing himself a space which is, in the end, social to the extent that yoga is also a socially constructed approach. The methods that the yogi uses, the position that he occupies at the heart of a culture, had been in development for centuries. The reference on the matter remains the model of the distinction by Pierre Bourdieu (1979), when he illustrates that the choice of a lifestyle (a habitus15) shapes the body and the social identity of an individual. The yogi defines one pole in which the habitus adapts itself to the necessities of anatomy and physiology. At the other extreme, we have the lifestyles in which the body dynamics are submitted to the demands of survival in a society. To have to bend over every day to garden imposes demands on the back that no physiotherapists could recommend. Here is a personal anecdote illustrating this point.

A vignette concerning Isaac Stern. Some time ago, in the 1970s, I went to hear violinist Isaac Stern with a friend who is a Rolfer16 and who was trying to straighten my back. Stern was already an old man. By dint of bending over his violin, he was almost hunchback between the shoulder blades. When he stopped playing, he greeted us with a broad and charming smile, but his back did not straighten and his head remained slightly bent toward the left shoulder on which he usually rested his violin. I asked my friend if Isaac Stern would still be as good a violinist if we straightened his back. It was my impression that we were looking at an adaptation of the body that allowed for an even better playing of the violin, even if it was detrimental from a medical point of view. Not every professional violinist adapts to his instrument in this way, but they are all in a struggle that their way of playing might be less detrimental to their body and allow them to play as well as possible. I recall that at the end of his life, violinist Sándor Végh, who had spent his life playing the violin in a quartet sitting on a chair, was also incapable of completely straightening his legs when he stood up.

The laws of behavior and the mind follow modes of functioning that force the organism to adapt to those demands of the environment that cannot be managed in a compatible way with the demands of physiology. It is precisely because the human organism is capable of managing dimensions that function differently, the human species was able to adapt to such varied natural and social contexts.17 This plasticity renders every notion of an ideal body hardly useful in psychotherapy. An examination of the rapport between the returning blood flow in the veins and the sitting posture provides me with the opportunity to develop this point with a few examples.

The interaction between the chair and the return of the blood via the leg veins illustrates how posture participates automatically, without conscious thought, in the way a lifestyle influences the mechanisms of physiological regulation.

In a wide and deep river, the water flows gently. If the river abruptly narrows, and boulders impede its way, the water becomes turbulent and the flow of the rivers is slowed down. This increases the pressure of the water on the boulders. The boulders retain the deposits carried by the water, and the current slowly erodes them. As for the circulation of the blood, each joint is a passage of this type.

A European, accustomed to eating sitting on a chair, soon enters in contact with this particularity when he arrives in Japan and sits on the floor with his buttocks on his heels. Unless his joints are particularly (for a European) flexible, he will soon experience pain in his legs. When he unfolds them to stretch, his legs will be numb and almost without sensation. He then has the impression that his legs and feet have become a formless tingling mass. After having moved his legs, he gradually acquires the impression of reappropriating them. They return to their usual state. This individual suffered from having placed himself in a position for which his venous circulation is not adapted. The folding of his knees and the compression of the muscular tissues of the leg seriously slowed down the venous circulation. Movement, stretching the muscles, opening the joints, breathing deeply, and massage are all ways to stimulate the circulation of the blood so that it might take up its habitual functioning. This example also illustrates that a lifestyle influences the adaptation of circulation to a postural repertoire. The Japanese generally do not have this kind of problem when they eat sitting on the floor, legs folded, feet under the pelvis.

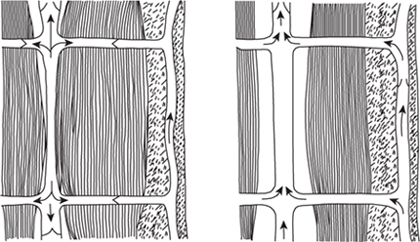

Each contraction of the muscles of the feet and of the legs pushes the venous blood upward (see figures 13.2 and 13.3). Valves situated in the veins allow the blood to flow toward the abdomen but stop it from going back to the feet. This mechanism is influenced by social behavior, independently of any cognitive and affective experience.

FIGURE 13.2. The venous pump of the muscles of the legs (the effect of walking on the plantar veins). Source: Bonnet and Millet (1971, p. 250).

FIGURE 13.3. The muscular pump of the calves. The arrows indicate the direction of the muscular contraction. Source: Bonnet and Millet (1971, p. 250).

The relationship between posture and the cardiovascular system is particularly close in the venous circulation of the legs. In most of the common positions, when the arterial blood descends from the heart to the feet, it is pushed by the cardiac pump and gravity. On the other hand, when the venous blood returns from the feet to the heart, it must fight gravity, and it receives no help from the heart because the venous circulation is largely independent of cardiac activity.

The legs are endowed with a device that pushes the blood upward. This engine depends on two fundamental mechanisms: the firmness of the veins and the valves. The valves are like mouths that open only in one direction. They open to let the upward-moving venous blood pass through when the surrounding muscles contract and close when the surrounding muscles relax to stop it from descending. This movement begins in the feet because they contain a thick venous channel that forms a sort of sponge. Every time an individual rests on this “sponge,”18 the venous blood escapes and rises toward the calves. This is why walking is excellent for the venous circulation. The return of the venous blood is also modulated by the following mechanisms:

The fact that the venous circulation depends on body movements and regulates the consistency of tissues is well known in hospitals. When a person remains immobile for hours, the tissues are no longer purified by the venous blood because of poor circulation. This causes the formation of ulcers on the skin that are often referred to as bedsores. The lesions of the skin mostly appear on the points of contact between the body and the mattress, like areas on the buttocks or the heels for a patient who is lying on his back. To avoid this, nurses regularly modify the patient’s position, rub the patient’s skin, and sometime change to a more proper mattress.20

Yoga teachers have always integrated recent discoveries into their understanding of the body. I do not know when they first found an explicit mechanical link between exercises and the return of the venous blood, but long ago they observed a correlation between certain exercises and the return of the venous blood.21 All the positions in which the legs are extended toward the ceiling (the sirsa-asanas) allow gravity to favor the voyage of the venous blood of the legs toward the heart, but these positions do not develop the abilities required during walking. On the other hand, the exercise called the sponge supports the development of the muscles-veins relationship. In this exercise, you contract and relax each muscle several times over as if each were a sponge that you wring out. This can be done without paying attention to the respiratory rhythm or done in coordination with it. For example, you inhale every time that you contract a muscle at the same time. Other combinations can be made in function of various refinements. Certain massage techniques enliven this mechanism. The massage therapist takes a regular rhythm marked by the compression of the muscle and its release. Once more, this rhythm can be coordinated with the respiratory rhythm or not.

The basic principle of this exercise is found in most gymnastics and massage methods in the world. This technique has been taken up, for example, by Edmund Jacobson’s relaxation. In a course where Gerda Boyesen taught her variation, she suggested that we massage the return of the venous blood from head to foot. She feared that by going from the feet to the head, the massage therapist would create too strong a venous flow, which the heart may not be able to manage.22 In the case of Europeans who have difficulty sitting as the Japanese do, chronic muscular tension probably inhibits the plasticity required by the interaction between the venous circulation and the muscles of the legs.

Venous Circulation and Social Ritual: The Necessity to Have a Varied Postural Repertoire

The studies on the varicose veins in the legs confirm and increase our knowledge concerning the rapport between posture, cultural behavior, the dynamics of the veins and the state of the tissues. I am thinking of a series of studies that coordinate three dimensions:

This interaction is notably studied in research23 that wants to demonstrate the impact of professional behavior on health. It would seem that all of the professions that impose a posture throughout the day considerably increase the probability that employees will have serious venous circulatory problems, like the formation of varicose veins.

Individuals who remain sitting in a chair all day long every day seem to be particularly vulnerable to circulatory problems of the venous return. Japan presents an interesting case. Since the Japanese traditionally does not often use chairs, they use a highly varied postural repertoire in their daily life. Before World War II, varicose veins were rare. On the other hand, ever since the lifestyle from the United States and Europe has increasingly influenced the behavior of the Japanese, they now spend more time sitting on chairs; cases of varicose veins have increased.

Another area of research on this theme studies the ergonomics of chairs.24 It consists in finding a way to design comfortable chairs that are also beneficial to one’s health. Chronic sitting not only has a detrimental effect on the return of venous blood but is also detrimental to the back, the muscle tone of the abdominals, the neck, the shoulders, the arms, and the hands. These studies show that there is no way to sit that is both comfortable in the long run and orthopedically healthy. Comfort and health obey, in this case, different laws that are not possible to coordinate in any harmonious manner.

It is thus possible to conclude that the human organism is poorly adapted to monopostural activities. The adaptation to sitting on a chair or a bench is particularly poor. These research studies draw attention to the fact that only recently (within the past few centuries) has sitting on a chair become a common human practice. It probably is not yet part of the mechanisms that have influenced the selection of human genes. It is thus possible that the dichotomies associated with sitting, like the one between comfort and proper orthopedics, are related to the fact that sitting does not figure among the anatomical and physiological innate adaptation mechanisms of the human organism. If sitting embeds itself into the human postural repertoire in centuries to come, and if humanity survives that long, it will be interesting to observe how the organism will adapt itself at the genetic level to the use of this posture.25