‘The occasion of my death’

Jonah Andrew found John Lees some time between two and three o’clock on Monday 16 August, long after the crowd had been dispersed. He was visibly distressed, and said to his friend, ‘I have been dangerously hurt, Andrew, which has affected my body very much.’1 Andrew recalled that, rather than walk to the infirmary nearby, where some of the injured were being treated, he declared, ‘I must return home, for I am getting very sick and poorly, which I think will be the occasion of my death.’

It was just before dark when Hannah Lees saw her stepson at the gate of the family home in Oldham. She had already been told by one of her sons, James, that John had been ‘cut’ and so she told him to come into the house so that his arm could be cleaned and dressed.2 John entered the house and had tea and toast, after which his other stepbrother, Thomas, helped him up the stairs to bed. But, having made slow progress to reach the top of the stairs, John appeared to faint.3 By the time they had reached the bedchamber, he had turned very pale. As Thomas tried to help him out of his clothes, he realized that John’s shirt was stuck fast to his body by blood and ‘the flesh was cut to the bone’.4 He later described the wound as ‘a foul cut’.5 Having slowly removed the shirt, Thomas washed the wound as best he could, while John ‘told me that was not the worst, and he desired me to look at his shoes, how they were cut off by the horses’.6 Thomas saw how the left shoe was sliced off and the leather torn. He stayed with John the whole night, afraid to leave him alone in this severely battered condition.

Hannah recalled that John’s shirt ‘was cut in many a place, and his coat was cut over his shoulder and elbow’, yet it was Thomas’s comment that it was a ‘foul cut’ which alerted her that her stepson was in a very bad way. On the left shoulder, both John’s coat and waistcoat had been cut through. The top of his hat had been completely removed, although she was uncertain whether it, too, had been cut with a sword. Hannah observed that the wound on John’s elbow was about two inches long and opened to the breadth of her little finger. She advised him to see a doctor, which he did the following day, and the wound was dressed.7

Robert Lees saw his son at his factory on the morning of Tuesday 17 August, between eight and nine o’clock. John was without his coat and waistcoat and the shirt he wore was ‘all over blood’.8 Robert also recalled seeing blood on John’s arm.9 Despite this Robert was irritable with his son, still angry that John had attended the meeting against his wishes, telling him that if he could not work, he should go to the overseer. John did not utter a word in response.

Over the coming days, Robert observed his son’s condition getting worse and worse, but, surprisingly, was not much concerned: ‘I thought he would get better; and I did not think there was any danger.’10 Although he had been cut and beaten, John was young, and he had fought in and survived major battles, so, with care, he might well make a full recovery.

John remained in the family home, usually in his bed, although he occasionally had strength enough to go out for a walk and take some fresh air. Over this period, Thomas and he walked into Oldham, to Middleton and to Stockport. While on their way to Middleton, the brothers drank ale at the Dusty Miller Inn and several other places and John was ‘rather tipsy like; not what they call drunk; he walked well enough’.11 The two of them even ventured to Manchester, travelling by cart there and back.12 This might have suggested that John’s strength and health were returning.

But as time passed John became less able to hold down his food, eventually vomiting every time he ate. He also complained of a violent pain in his left shoulder, where Hannah had observed the cuts through his clothing. Whenever Hannah tried to lift him up to give him water to drink, he winced and ‘made faces’.13 She said that he was ‘very low and down-spirited’.14 Then John’s left leg began to swell and became mottled with purple spots from the foot upwards. At this point a surgeon, Mr Earnshaw, was called. He remained in attendance for the next few weeks. The left side of John’s body gradually became completely numb. Eventually he lost the use of his left leg and arm and the sight of his left eye.15

William Harrison saw John on Thursday 2 September. He was lying on a couch in the kitchen, his face ‘as white as a cap’. John ‘told me he was at the battle of Waterloo, but he never was in such danger there as he was at the meeting; for at Waterloo there was man to man, but at Manchester it was downright murder’.16

The following day, Thomas observed that his brother ‘had no knowledge at all of what was done or said to him’,17 and on Sunday the 5th Hannah describes him as being so poorly that he had to be carried downstairs by his brothers so he could sit in the kitchen for company, as was his habit. She also says that by this time he had difficulty responding with a ‘No’.18 James Clegg, a spinner who worked in Robert Lees’s factory, sat up with him that night and confirmed that John was unable to respond to anything.19 John’s brother Thomas said that by the Sunday he had become ‘speechless’.20 From that time on John remained in his bed until, in the early hours of Tuesday 7 September, he died. He was twenty-two years old.

Mr Earnshaw, the surgeon, certified that his death had been the result of violence. Several householders were duly summoned to attend the coroner’s inquest, initially conducted by George Battye (a clerk and deputy to the coroner of the Rochdale district, Thomas Ferrand), at the Duke of York Inn at Oldham, on Wednesday 8 September at half past ten.21 The eyewitness accounts cited here come from the transcript of this inquest.

As part of the inquiry, several surgeons were asked to inspect the body. William Basnett saw John’s body the day after he died and said that it ‘was in a high state of putrefaction’. He also observed that the cut to John’s elbow was ‘livid’ and that the bone ‘was separated’ so much so that when he bent the elbow ‘the bone was protruded’ and ‘cut partly in two’.22 He described the discolouration to the skin on the shoulders, back and loins. Basnett considered that this was the result of ‘violence, inflicted with some blunt instrument’ and that as a result of these injuries John would have been ‘in excruciating pain for some days previous to his death’.23 The loss of eyesight and the use of limbs, the sickness, low spirits and dwindling appetite were all a consequence, in his opinion, of a spinal injury. In sum, William Basnett concluded, ‘the wounds and bruises caused the mortification’.24

John Cox also examined the body. He stated that the wound to the elbow was consistent with a sword cut, as if the victim had raised his arm to deflect a blow. He had removed a piece of loosened bone from the wound the size of a sixpence.25 The fact that John’s back was bruised rather than cut suggested that, if he had been attacked with a sword, the flat rather than the edge had been used.26 John Cox had opened up the body, noting that the omentum, the fatty layer that covers the intestines and organs of the lower abdomen, was very inflamed and that ‘on moving the body, much blood gushed from the mouth and nostrils. On opening the larynx, or windpipe, it was full of blood. The right lobe of the lungs was full of blood.’27 Cox was asked whether, if the deceased had been bled, he might have survived. The surgeon thought this a possibility: ‘if he had received proper surgical and medical assistance… if copious quantities of blood had been taken from him, as I should have done, the injury might have been checked.’ Cox had not conferred with Earnshaw prior to examining the body, nor was Earnshaw requested to be present during Cox’s examination, as was the usual practice.28 Cox stated that with the injuries John had suffered, it would be expected that he would have complained more, certainly, than had been reported by various people who were with him at the time, but Cox also observed, ‘I understood he was afraid of complaining to his father on account of the circumstances under which he received the injury.’29 James Clegg was present at the autopsy, and recalled that Cox said that the bruises, rather than the cut, had been the cause of death.30

All this detail was vital. Was it the cuts he had suffered from the cavalry – whether Yeomanry or Hussars – that had killed John or the sustained beating he had received at the hands of the special constables, as many witnesses came forward to testify?

Betty Ireland and James Clegg laid out John’s body before it had turned cold.31 Betty, the wife of the local shoemaker, declared that ‘I have seen many dead people, but I never saw such a corpse as this, in all my life’.32 In general appearance, ‘there was hardly a free place on his back; it was exactly as if he had been tied to a halberd and flogged.’ She continued, ‘I have often seen dead bodies discoloured, but I never saw one like this. I think his inside was putrified [sic].’ She confirmed that the wounds were mainly on his back and sides, not on his front and breast.33 One wound, she recalled, refused to heal and, while she was preparing the body, it opened up. ‘He bled most when he was put into his coffin.’34

James Wroe, in Peterloo Massacre, declared the investigation into John Lees’s death as being of ‘extreme importance’, for the ‘issue of this Inquest, if it ever be suffered to come to an issue, will, we have no doubt, give a decisive blow to Lord Sidmouth and the rest of his crew: for we have no hesitation in anticipating the verdict of twelve honest men and independent men, from the nature of the evidence which has already come before them.’35 If the inquest had the capacity, whether in and of itself or through a future prosecution, to bring someone to account for the death of John Lees, it was thanks to the efforts of two resourceful solicitors, James Harmer* of London, the son of a Spitalfields weaver, and Henry Denison of Liverpool, who had arrived in Oldham accompanied by as many witnesses to the events at St Peter’s Field as would fill three or four coaches.36 James Harmer, now representing Robert Lees, had attempted to serve indictments against several of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry at Lancaster the previous week, but this had been thrown out by the Grand Jury.37 This was in the wake of an application to any Justice of the Peace in the County of Lancashire to accept charges against the Manchester magistrates, which was, unsurprisingly, rejected.38 It was then that Harmer heard that John Lees had died from his wounds, and, after some enquiry, discovered where and when the coroner’s inquest would be held.

Despite delaying tactics, several changes of venue (from the Duke of York to the Angel Inn in Oldham and then the Star Inn in Manchester), a change of coroner from Battye to Ferrand and the exhumation of John’s body as a result, and several attempts to throw out witness statements or close down the entire procedure, Harmer, Denison and their team managed to keep the inquest going, on and off, for a month. The failure, thus far, to instigate legal proceedings against the magistrates meant that this inquest became the main focus for the reformers and, as a result, carried a great burden of expectation. The evidence given by a relentless parade of witnesses, all attesting to the brutality with which John and his fellows were treated, seemed to point to one conclusion in this case: death from injuries inflicted during a prolonged and violent attack by the special constables. Murder, in fact.

However, as the first coroner, Mr Battye, admitted at the start of the inquest, the presumption had been a straightforward verdict of death caused by crushing from the crowds.39 And despite Harmer’s persistence, on 13 October the inquest was adjourned until 1 December, ostensibly because of the jury’s fatigue. There was also a suggestion of intimidation, as the authorities saw it, from the unruly crowds that gathered in and around the inn. An application, with a joint affidavit from Harmer and Dennison, was made to the King’s Bench to compel the coroner to proceed and the case was heard on 29 November. However, the inquest was abandoned on the technicality that, contrary to procedure, the jury and coroner had viewed John’s body at different times.40 In a petition to the House of Commons, Robert Lees declared that despite the evidence, ‘the Coroner throughout evinced a manifest partiality for the Magistrates and Yeomanry Cavalry of Manchester, to whose illegal and violent conduct your Petitioner attributes the premature death of his Son.’ Robert Lees was convinced ‘that a verdict of Wilful Murder must and would have been given against many individuals engaged in the cruel attack… and your Petitioner has good reason to believe that the last-mentioned adjournment was made solely with a view to screen and protect the delinquents, who were likely to be affected by the verdict of the Jury’. Having no other recourse ‘to bring to justice the authors of his son’s death’, he ‘presumed to lay a simple statement of the facts before your Honourable House’.41 The petition was presented to the House of Commons by Sir Francis Burdett and debated on 16 December.42 But even then, the case was not reopened or re-examined.43

Some years later Archibald Prentice contemplated the amazing restraint displayed by the people of Lancashire, who had not retaliated against either those individuals who had actually maimed, disabled and even killed the victims of Peterloo, or the men who had ordered them into the crowd. He arrived at a simple answer: ‘The population of Lancashire had faith in the just administration of the law.’ The working men may have been rough in manner and ‘rude in speech’ but they were ‘shrewd, intelligent’, ‘possessing much of the generous qualities of the Anglo-Saxon race’. They would not ‘stoop to cowardly assassination. They had faith in their principles and greater belief in moral than physical force.’44

Many of the leading radicals, including Henry Hunt, now placed their faith in the courts for legal redress, rather than trying to maintain pressure on the authorities via the mass demonstrations that had formerly served them so well. As seen at Oldham, the battle ground had moved to an arena where the authorities had the upper hand.45 Yet although the inquest into John Lees’s death failed to develop into a criminal prosecution (in fact no one was ever charged with his murder), another opportunity soon arose to expose the perpetrators and bring them to account. At the Lancaster Assizes in September, ten prisoners, including Henry Hunt, Joseph Johnson, James Moorhouse, John Knight, Joseph Healey, John Thacker Saxton and Samuel Bamford, were indicted, not for high treason but on the lesser charge of conspiracy and unlawful assembly. All were granted bail, with the trial fixed for 16 March 1820: not, however, in Salford or even Lancaster, but seventy miles away on the other side of the Pennine Hills, at York. Hunt had petitioned for this, in order, as he thought, to have any hope of a fair trial.46

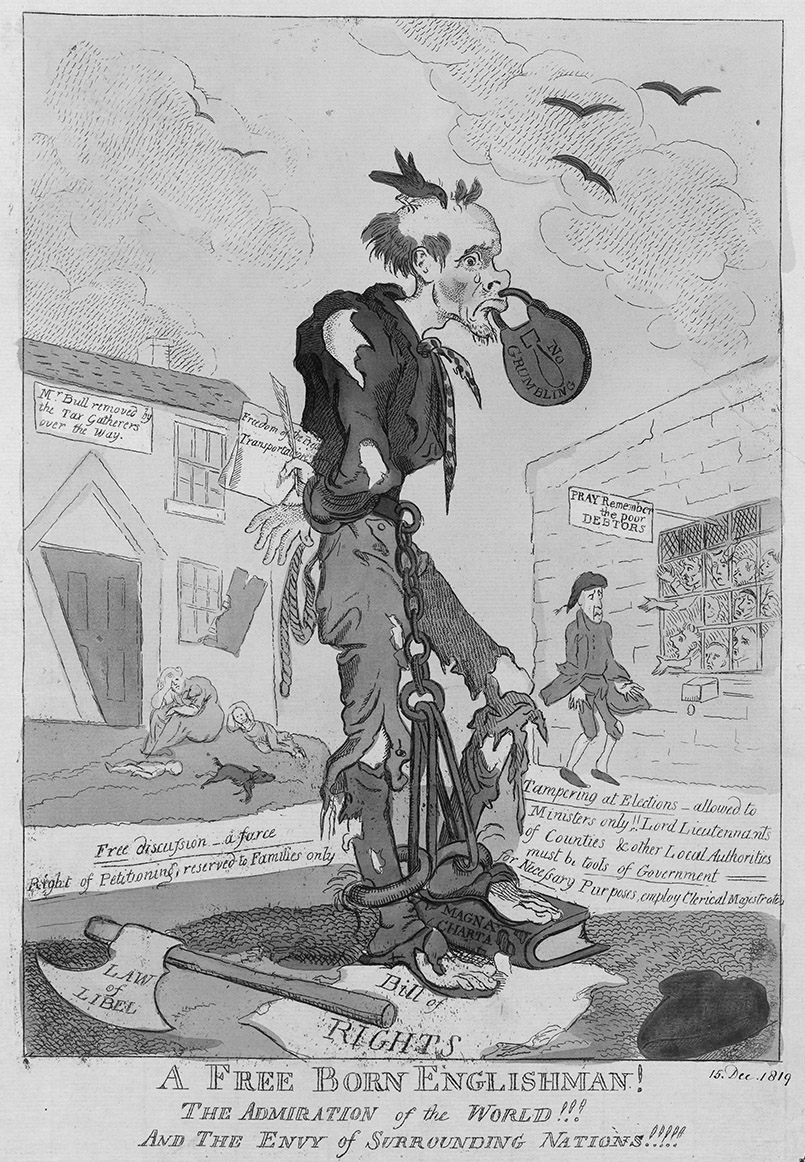

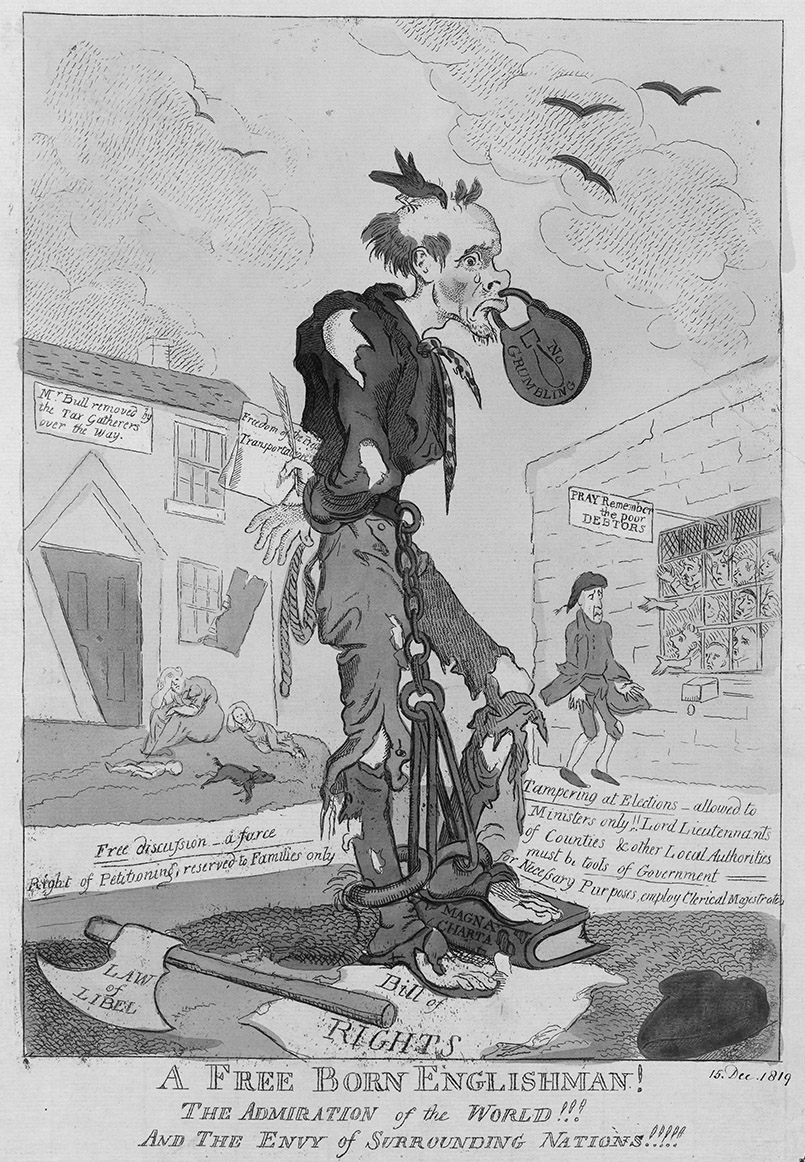

A Freeborn Englishman! The admiration of the world!!! And the envy of surround nations!!!!, by George Cruikshank, 1819.

(© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Hunt had already begun agitating from his solitary confinement in the New Bailey. After his release on bail, with the surety provided by Sir Charles Wolseley, he paraded back to Manchester from Lancaster in triumph, led by a thousand working men – colliers, weavers and crofters. To the local magistrates, as James Norris said, it seemed that Hunt was once more ‘in possession of this part of the country’.47 But in London, moderate reformers such as Sir Francis Burdett were attempting to take advantage of the post-Peterloo environment, while also attempting to remove Henry Hunt from their deliberations: he had created too many enemies and, as the figurehead for what was viewed as a principally working-class movement, he was something of a pariah.

The beleaguered Hunt might have had some cause for cheer with the arrival at Liverpool on 22 November of William Cobbett. Cobbett did not arrive empty-handed. Amongst his baggage were the remains of the ‘immortal’ Thomas Paine, which he had removed from the grounds of the New Rochelle cottage in New York State that had been Paine’s home between 1802 and 1806 (Paine had died in 1809). What genuine benefit Cobbett might have gained from bringing such a relic back to England is debatable. Cobbett himself declared in an open letter to Henry Hunt that their reburial in England would create a focus for the reform movement, a place of homage and even pilgrimage for the people.48 In fact, he was widely ridiculed for this peculiar and faintly macabre gesture. Realizing his mistake, according to William Hazlitt, Cobbett had scarcely landed in Liverpool ‘when he left the bones of a great man to shift for themselves’.49 In the 1820 pamphlet A Parody on the Political House that Jack Built, Cobbett was caricatured carrying a coffin on his back containing what was left of the great English radical.†

In the meantime, Lord Sidmouth had heard that the Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding of Yorkshire, Lord Fitzwilliam, was organizing a petition for a government enquiry into the events of 16 August. With the support of the Prince Regent and the cabinet, Sidmouth quickly forced Fitzwilliam to resign. In any case, by the end of 1819, the Liverpool government had devised a sequence of bills to repress reformist activity, which became known as the Six Acts. The legislation targeted radical newspapers and mass meetings; drilling, of the kind that had been seen before the meeting on 16 August, could now result in arrest and even transportation. Through the Seditious Meetings Prevention Bill even the carrying of banners was prohibited, while attendance at political meetings was now restricted to those who lived within the parish in which the meeting was held: in future there would be no marching to Manchester from all over Lancashire. The Blasphemous and Seditious Libels Act increased the maximum sentence for such crimes to fourteen years’ transportation, while the Newspaper and Stamp Duties Act extended taxation to publications that expressed opinions as well as news. This draconian legislation effectively ended the post-war radical mobilization.50

* Harmer is said to be the model for Charles Dickens’ Mr Jaggers in Great Expectations (first serialized in 1860–1).

† Rather than abandoned, as Hazlitt’s comment might suggest, they were, in fact, still in Cobbett’s possession when he died twenty years later, but then disappeared.