1

Green Labyrinth

Ecuador was and is the center of the planet, and it has been the cultural center of our planet since uncharted times.

The Tayos Caves are, without a doubt, one of the most complex mysteries an archaeological detective could come upon. Some will see them from a pragmatic angle, others from a mystical one, and others from an almost fanatically subjective point of view.

Unfortunately, many of the main witnesses have already left us, and they have taken their truths and their lies with them. Those of us who remain are the ones who learned about the story directly from some of those who set the stage, and from others who have gotten on that same stage with passion in order to defeat boredom and find meaning in their lives.

The Tayos represent many things. They are Ecuador at its finest; they are its essence, its impenetrable jungles, and the mystery of more than one race but especially the indigenous people known as the Jíbaros or Shuar. They are the sum of the archetypes that take us back to a South America that was reinterpreted from the outside, only to be reviewed again from within; in this case, from the subterranean or intraterrestrial world, a dark hell that opens up from under that green inferno.

The many years that have gone by since the legend first came out and the lack of evidence through time have led many to regard the matter as false. This is particularly true for Ecuadorians, who have not believed in this phenenomenon ever since it first came to light.

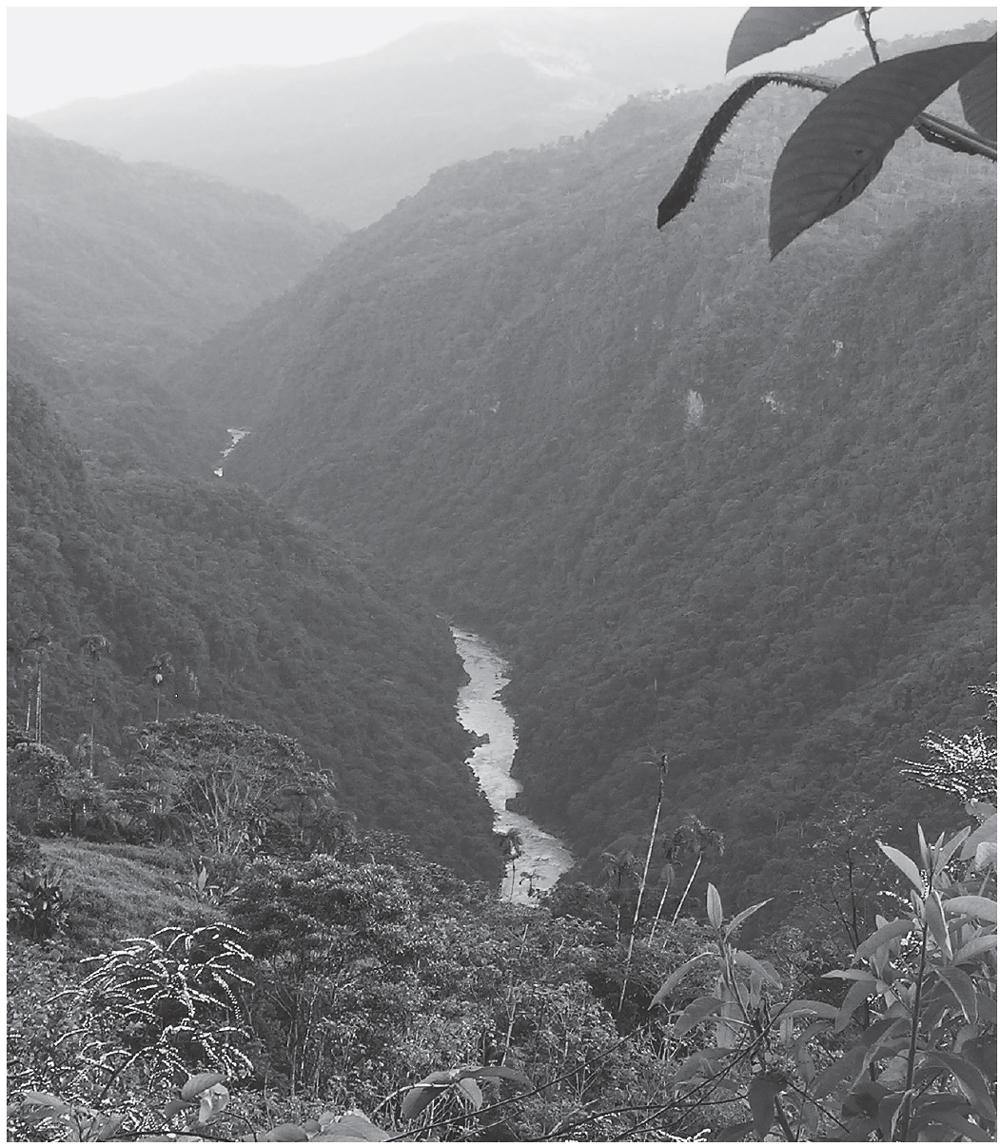

The Namangoza River surrounded by thick jungle

The Basque-Argentinian speleologist Julio Goyén Aguado, a good friend of mine, may be the reason I stuck with this enigma for so long—him and the Scottish engineer Stanley Hall, who always thought those studying the Tayos were ugly ducklings with the potential to become swans. (Later on I would understand the meaning behind that expression.) This book is not a biography of them, but I couldn’t have written it without talking about the life and work of the protagonists of the last three decades of this saga.

EARLY MADNESS FOR THE TAYOS MYSTERY

My interest in the Tayos can be seen in my first book Mundos paralelos (Parallel worlds), where a brief chapter mentions Julio Goyén Aguado, one of the individuals responsible for the diffusion of the story of the Tayos back in the late seventies. Aguado first contacted me through some mutual friends. I timidly arrived at his office and met a sober-looking man who seemed to be angry with me. To write that chapter, I had extracted his comments from 1969 for a magazine called 2001: Periodismo de Anticipación (2001: the journalism of anticipation), in which he had talked about the lost continent of Lemuria and its connection to the Andes. He had said: “The spiritual masters who worked on the path of good started recording precious chronicles and documents of the library of Lemuria to preserve the scientific and spiritual knowledge of the history of Earth. They are the ones who possess the secrets that are the legacy of men in South America.”

In our conversation, Aguado told me that many of the things mentioned in that article didn’t really happen that way. As I came to learn more about the topic over time, and as my friendship with him grew, I would understand that fantastic realism could better describe reality than a distorted or surreal image of it.

Aguado was a wonderful human being in every sense, one of those magical people who are so hard to find, and his work remains tinted with enchanting genius. Our twenty years of friendship went by very fast, maybe because of my self-exile and my rare trips to my home country. Fortunately, in the last years of his life we reconnected, and the friendship we had started years before grew even more.

Even if others who came into the picture tried to downplay Aguado’s leading role in the story of the Tayos Caves, his presence and the enigma around him remain unforgettable. Without his influence, it is possible that Ecuador and the Tayos would never have become a part of my destiny. There are countless letters, documents, and witnesses to corroborate this claim. The mysterious Juan Moricz would have never gone to Ecuador without Aguado, and if Moricz had never gone on this journey, the story, the legends, and the discovery of the caves would have been forgotten. Without Moricz there would be no book by von Däniken, and this story would be just another undisclosed tale of the Andean heights, valleys, and jungles, in wait of new explorers. Without von Däniken, there would have been no Stanley Hall, and the cave would not have gotten international attention. And without Hall, the story would not have been complicated by the involvement of Petronio Jaramillo Abarca, who originally claimed that he was taken into the cave by a childhood friend.

The story of the Tayos belongs to Latin America, not to Britain, in spite of the work of Stanley Hall. Unfortunately, what is written or visually documented in English has more international scope. Even Hispanics give greater value to texts written in a language other than Spanish.

In 1997 I spent a lot of time with Aguado, maybe because a part of me knew I would never see him again, but also because we had the same exploratory ideals. He was excited to go back to the caves and had promised he would try to get the necessary permits so that we could reach the chamber of the metallic library.

Back then I was trying, with superhuman patience, to convince the Latin division of the Discovery Channel to help us with a filmed expedition. I didn’t know that trying to convince both the Latin and the American divisions of the importance of the subject was a difficult crusade that would make me feel I was casting pearls before swine, as so often happens when you try to make a program about culture these days. I later learned that the topics showcased in the Latin and American divisions were, and still are, controlled mostly by the channel’s European division.

I was moved by Aguado’s humility when I told him about my endeavor. He simply asked me if I could take him with me on my Ecuadorian expedition. Two years of presentations and negotiations went by, but when everything was almost ready, he died in an accident in the Argentinian Andes.

In 1970 Aguado founded the Argentinian Center for Speleology (its Spanish acronym is CAE). This was the same year my exploration of the Brujas Cave (also known as the Witches’ Cave) in Malargüe, Mendoza, Argentina, took place. I had my speleological “initiation” around 1980, and I did my first small expedition, a preamble to what would come years later. During that trip, Aguado and the members of his team made the following statement to the local media: “Subterranean caverns connected with Ecuador will be studied in Mendoza.”

Since my first meeting with Julio in the winter of 1979, the subject of the connection between the Brujas and the Tayos Caves was as common as hearing that under the mountain range these tunnels connected countries and continents, and that beings from a benign brotherhood lived among them and watched over the destiny of humankind.

The newspaper that covered the expedition also said that “the whole American continent, from the Rocky Mountains to Patagonia, could be connected by artificial caves. If confirmed, this would be the greatest discovery ever made, a discovery that would undoubtedly change the history of humanity. The expedition will include specialists in anthropology, archaeology, geology, philology, and speleology with the hopes of finding one of the sites of the subterranean network located in Ecuador.”

MY FIRST TWO EXPEDITIONS

My journals are the best way to help the reader understand the story of the Tayos because they vividly illustrate what I experienced and explored. It took me almost three decades to get to Ecuador and the Tayos Caves. This odyssey has shown me that, like the rivers that cross the Amazon basin from north to south and west to east, the passing of days is unstoppable. (To see maps I have made showing the various areas explored, see plates 1 and 2.)

Notes from My Travel Journal

I was like a teenager coming back from his first Andean trip, in love with the “blue mountains,” as I called them back then—words that remain with me even today. The first trip to the Andes changed me in many ways.

I grew up in Argentina closer to my European roots, but I was lucky enough to have a couple of mentors who awoke in me the need to look west, deep into the South American continent, a trapeze of ancestral lands that made me daydream of the dawn of time.

These dreams are still the same today. Even after the rivers and gales of time and space have swollen my face and given me wrinkles, I am still thirsty for wind and sun and the Andes. Those holy mountains that pour out their rivers, the blood of the earth and life, running to the interior of the maternal womb—that was where I wanted to go. I went there with a purpose: to find the truth and break the spell.

Those mountains helped me follow that dream to find the truth. To accomplish this, I didn’t need to take hallucinogenic plants because I had broken my ego decades ago and more recently, maybe for thousands of years, trying to find the light at the end of the tunnel of truth. I had died a thousand deaths in quest of this truth and had always been resurrected.

These expeditions aimed to find the lost steps in the search of mystery and to corroborate if my friend Julio had lied to us about what he saw when he visited the Tayos Caves with Juan Moricz in 1968, or if he had had a peak experience.*1 Sometimes we need these uncertainties to be able to move forward and to reach a better future—one that stems from a cryptic past whose glories, more often than not, we don’t know how to interpret.

The stars still shine above us and send us messages we don’t understand. Every day we find things from the past. We leave them there, or we are moved to display them in museum cabinets, as dead as they were before their discovery.

I found this was common with the topic of the Tayos. Those who knew sometimes talked about it, sometimes kept quiet, but in the end they didn’t know and were not completely sure if their experience had been real. I sailed against the rivers of uncertainty, the lack of resources, and contrived disinformation to finally get there decades after my initial impulse.

It was a sublime obsession, or maybe a recurring madness. The grail was and is in the depths, and I had to look at it at least once. That is what I did in the end, and that gave me the temporary satisfaction of fulfilling a disregarded duty.

My work has been lonely, and I haven’t had many allies. I didn’t need governments, or crowns, or official science to accomplish my task. People tried to make me give up (even those who had supported me and claimed to be my friends); they told me to put it off until the area was more at peace. But that area had always been hostile, and it would continue being so. I have to thank them for having recognized my decisiveness in reaching the goal.

I have never been surer that the mind and the heart shape our reality, and that our intention is the secret formula we all have for accomplishing our tasks—the fire we can’t measure or contain, but which exists within us as a part of our human magic, of our lineage as terrestrial yet divine beings.

This essay has been written by a man in search of truth, a man who, like the Little Prince, believes that “what is essential is invisible to the eye.” And if I keep on believing, maybe what my friend Julio Goyén Aguado and his friend Juan Moricz told us could still be true in spite of all the doubts and the rivers of time that have endlessly gone by over the same place. This is where my expeditions and observations begin. They corroborate some beliefs and destroy others.

The only thing I can say is that I am free, and that nature is above us with its spectacular caverns and forests. That life force is much more important than any legacy of gold, copper, or brass. We are of the same essence, and we all come from one human being who may have had extrahuman origins. Today we are still here, with a sun that warms us and prepares us to wait for the next day with the hope or desire to evolve a little, to ascend, to be better human beings. An awareness of an American past that was ahead of its time may give us the strength to project ourselves ahead, toward an uncertain but exciting future.

Finally, Ecuador (2006)

Just like the last time, this time it wasn’t easy to get here because of the delays that had taken so long. This time too many factors coincided. I had the mission of finding more evidence to validate my research of the Masma*2 culture that I had studied since the early eighties, and I knew that in Ecuador, as in all the Andes, there were more keys to unravel.

Even if I had relocated to Europe and I had found my soul mate there, the restlessness aroused by an incomplete task would not leave me. It was more than just destiny or karma. There was something I had to begin so that I could end other things that were hanging by a thread between realities and dreams.

So after many letters back and forth with adventurer and treasure hunter Stan Grist, we both agreed it was time to do an expedition to the cave, thirty years after Stanley Hall’s international expedition of 1976. At the same time, I was still preparing the documentary I had been working on since the mideighties with my longtime friends the Alvarados, from Ecuavisa, the Ecuadorian TV channel.

I arrived in Quito on a rainy day, at the time of the elections. A part of me was finding it difficult to recover from a personal loss I had recently suffered. It meant surrendering and dying before moving on; and that syndrome of the explorer who can’t find his source of gold was showing its symptoms in advance.

With Grist we started reviewing the texts and clues from Stanley Hall’s book Tayos Gold, and we compared it to our own notes. He was looking for answers and had met my friend Aguado. Destiny had taken me to Buenos Aires just one year before I saw Aguado for the last time. Our destinies met and brought us together, all of us who had been and still are a part of the web of the Tayos.

We were supposed to go to the coordinates Hall had published as the real ones for locating the golden library that had eluded Moricz and followers in previous expeditions over several decades.

Before our departure Grist and I got to meet and interview Petronio Jaramillo Abarca’s widow. In the late sixties and early seventies, the writer and researcher Pino Turolla had interviewed Jaramillo, who was the self-proclaimed first person to discover the treasure of the Tayos Caves. Grist and I had come to the conclusion that Jaramillo was a key character, because we had both read Turolla’s book and had compared notes through the years.

This is why we headed toward Guayaquil for some interviews and to maybe come closer to Coangos, the Shuar town closest to the main caves of the same names. There we learned of the ideas of Gastón Fernández Borrero, Hernán Burgos Stone, and Monica Williams, who were part of the story of the Tayos through Juan Moricz. Before the Coangos expedition, I realized the relationship with Grist would not survive such a long journey into the jungle, because we were both too used to traveling alone. I still tried to invite him to join the first expedition, but my associates from Ecuavisa could not find a place for him. This was better for all of us, because the expedition would not get to its destination, and we had limited space and other inconveniences typical of jungle explorations. (Later, Grist would erase our experiences together from public commentaries and turned into a renegade.)

So I got to Guayaquil, to the Hotel Rizzo where Moricz lived for two decades until his death in 1991.

The Bizarre Death of Juan Moricz

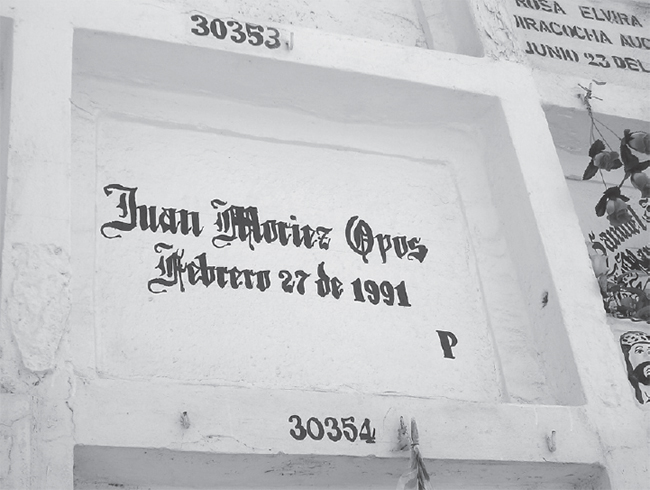

Moricz spent his last days at Hotel Rizzo in Guayaquil, where he had lived since 1968, when it was called the Continental. In 1991 he was found dead in the bathroom of room 409.

Moricz talked a lot with the hotel’s bellboys and waiters. He told Joel Condo, one of the managers, that “there was a treasure in the cave that was millions of years old.” Moricz was always late with the rent, so one time the manager pushed him to pay, and this angered Moricz. “Come over here, I want to show you what I have,” Moricz said. He hailed a cab, and they went to the intersection of Aguirre and Malecón. The manager followed him to a fifth floor, where Moricz had his office, and there Moricz showed him some rocks in a glass cabinet with geological samples, maps, and photographs. “I have golden ingots in the Bank of Uruguay, and at the moment I am waiting to finish a contract with the Japanese.”

Cesar Gavilanes, the head waiter at the Continental at the time, said, “Moricz was very quiet; he was more Argentinian than Hungarian. In his last years a woman much younger than him looked after him. When he passed away, she came while the superintendent and the commissioner drew up the death certificate.”

One day when I was interviewing the hotel personnel, something weird happened in the room. The bathroom mirror of the room where Moricz had stayed up until his heart attack cracked for no reason at all, hurting the bellboy’s hand. When I got to the room, I found blood everywhere, even on the cracked pieces of mirror on the floor. The people at the hotel believed this happened because I had bothered the muertito or “little dead guy,” as the personnel described him. This coincided with my intuition that Juan had left us with many unresolved issues; maybe he was still roaming the Earth.

There were many speculations around his death. People talked about curses and urban legends; they had exalted him and vilified him, but his presence remained. Not too far away, the iguanas at the plaza slept under the sun, just like the day Moricz had died, taking a thousand secrets with him to the grave.

The tomb of Juan Moricz

Andreas Faber-Kaiser*3 said that it would be good to search the grave, because it was hard for him to believe the Hungarian was no longer with us, and he also believed that Moricz’s work would be left unfinished. Faber-Kaiser was suspicious as to whether Moricz was buried beneath his tomb marker and thought the tomb should be opened to verify Moricz’s death. In Guayaquil, I found some of Moricz’s friends, who gave me more information. The most important ones were the Peña Matheus brothers, the true patrons of the life and adventures of the explorer of the Tayos Caves.

Back in Quito I would continue to finding more links of the chain of events that allowed me to rebuild Moricz’s life from the moment he arrived at the Ecuadorian capital and other places in the country between 1964 and 1991. So the dots started connecting after every meeting I had with the other protagonists of the story.

I met a member of the Rosicrucian order, who said Moricz had shown them some plates that did not belong to those of Father Crespi. Professor Soto remembers seeing Moricz showing his colleagues a stack of golden plates piled one over the other; he had wrapped them in Kraft paper under his arm.

Another pillar of support would be Jorge Salvador Lara, whom I met researching the Jesuit Library. He was one of the first persons Moricz visited when he first arrived in Ecuador, and he admitted that the Hungarian’s search could have some truth behind it, even if it broke with the dogmas of traditional history.

The First Expedition: Notes from the Travel Journal

During my first three months in Ecuador I researched the Tayos system in the eastern part of the country. For this I did two joint expeditions, the first one with the support of GITFA (Tactical Intervention Group of the Air Force of Ecuador), which focused on the caverns of the Morona-Santiago province (plate 3 shows a photo of this area).

These members of the Ecuadorian Air Force were trained for all types of terrain, but the members who went with me had not been specifically trained in climbing, nor did they have experience in caves.

The main Tayos Cave was the setting of Moricz’s 1969 expedition for CETURIS (the Ecuadorian Corporation of Tourism) as well as the setting for the international (or British-Ecuadorian) expedition of 1976. When we tried to get there from the Coangos River, I discovered that the situation with the natives was very unstable. There was also a military director in our group who was too cautious (he was a desk officer; as has happened for centuries in the armed forces, unpopular officers end up being sent to the jungle), and he wanted to avoid risks more than he wanted to reach the objective.

When we returned to Macas, I was informed there had been an attack in Sucua. There we interviewed Colonel Marco Ortiz and Governor Joaquín Estrella. In the end, my expedition helped create a connection for Ecuavisa, because this network, like all those from the main cities, did not cover the eastern part of Ecuador. We were informed that the police had been attacked when they tried to evict a Shuar group that was invading lands and properties. The place had been the Bumbaza/Wamba Center, 20.4 miles in the direction of Gualaquiza.

Since we could not cross the Namangoza River, we went back to Macas. After a night of frustration and insomnia, I decided we would explore the other Tayos Cave. Little did I know this cave was the one for which Stanley Hall, a previous explorer of the cave, had given the coordinates for in his new online notes and in a book he had recently self-published.

The purpose of my first expedition was to verify Stanley Hall’s declarations, as Hall was a controversial follower of Juan Moricz’s theories. But at the beginning of 2005, Hall surprised those interested in the metallic library by believing Jaramillo’s account of the caves and moving the location of the treasure from one cavern to another located 62 miles away.

After twenty-seven years of research, I finally decided to begin the first part of my explorations with the most novel aspect of the topic: the declarations that the library was in one of the caverns of the Pastaza River, and not in the Coangos, as everyone had believed since the late seventies, and where the expeditions of 1969 and 1976 had focused, the latter of which was organized by Hall himself. All those expeditions concluded without ever finding the metallic library that had been seen by Moricz and Aguado in 1968.

Second Expedition (The Pastaza River): Notes from the Travel Journal

The expedition managed to go almost all the way to the bottom of the Chumbitayo Cave located close to the Pastaza River (see plate 4).

We photographed and studied the behavior of the tayos, birds considered sacred by the indigenous Shuar people since ancient times. The Shuar still hunt the squabs in nests found in the high cavern walls.

Along the subterranean river, I found several unexplained sculptures that appeared to be from the Masma culture, which reminded me of my repeated explorations for similar structures on Peru’s Marcahuasi Plateau. These sculptures are shaped like condors or pigeons, piranha-like fish, which are abundant in the area, and a combined bird-fish that is common in Shuar iconography. During our expeditions to the Chumbitayo Cave (which, Hall believed, had been where Jaramillo initially found the library and the metallic treasure), other sculptures that stand out are birds and other creatures, such as mammals or canines, chasing after them. Among these anomalies we could also observe other animals, such as a dolphin (which could very well be a river dolphin), and a spectacular piranha sculpted on a low embankment. Its perfection and its location, leveled over the subterranean river, make it impossible to say that it is a natural occurrence caused by erosion. This too reminded me of the Masma sculptures in the Marcahuasi Plateau, where figures of marine creatures, such as seals, sea lions, or fish, are undoubtedly found in an area of small lakes that only fill up on certain periods of the year.

Another geological anomaly was an anvil-like stone that protruded from one of the walls of the subterranean river. This was unusual and could not be explained by natural causes (see plate 5 to see me inspecting the rock of this cave). These elements are also found in the Tayos Cave at Coangos, such as the angular stone and the brick and polished arches, elements that remain unexplained, even though the British-Ecuadorian expedition of 1976 attempted to describe them as formations caused by fluvial erosion. (You can read their report.)

In one part of the caves, thanks to the observant eye of my photography director, Mathias Spatz, we discovered an area with golden metallic reflections with perfectly delineated rectangles that stood out and may have contributed to the legend of the gold plates in the Tayos Caves (see plate 6).

Could these golden swaths be what was glimpsed by those explorers of the past? Logic and the intrinsic truth don’t always apply in the universe of the Tayos. Perhaps the explorers before me reasoned the treasure of the caves into existence; but then again perhaps they did not. What I saw and what they saw may be completely unrelated, or our observations may indeed be linked. Perhaps we will never know for certain, unless undeniable evidence is unearthed, but we can continue to wonder, debate, and dream. The pages that follow may introduce you to the story of the Tayos for the first time. If you are a seasoned researcher, may they illuminate your quest.