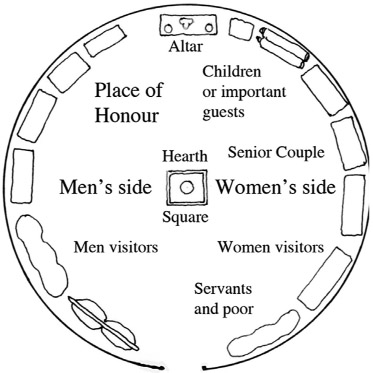

Figure 3.1.1 Plan of a Mongolian yurt Source: After Faegre 1979

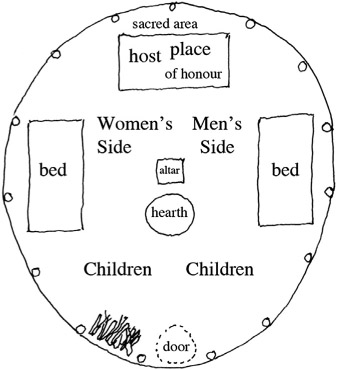

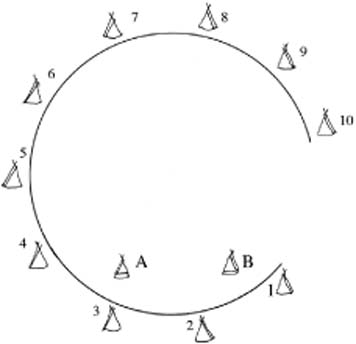

The experience of containment for every individual starts with the womb, and already there must be some haptic sense of being carried about, perhaps even some awareness of mother’s direction of walk; certainly of whether she is active or resting. The womb is the first centre of the child’s world; birth the first crossing of a threshold. Thereafter, mother’s embrace and her breast become centre, then the bed, the room, the house, the settlement or village, gradually discovered from the centre outwards as a nesting series. This idea of centre versus periphery is essential to human beings and basic for architecture, reflected in indigenous buildings throughout the world. The temporary Aborigine shelter was semicircular, centred on the small fire that kept everyone warm in the desert night.1 The Mongolian yurt and the Native American tipi (Figures 3.1.1 and 3.1.2) are circular buildings, again with a fire at the centre, both also with altars to connect with the powers above: the tipi with a square of bare earth to connect with powers below.2 When Native Americans came together in celebration, they would pitch their tipis in a circle, usually in clan order and with some medicine tipis for spirit contacts placed within the ring (Figure 3.1.3).3 The camp therefore had a protected centre of social space, while beyond the ring was the wild, the uncontrolled.

When the child starts to crawl, he or she creates a linear path, moving towards or away from things, and confronting other people. This is the beginning of an essential linear principle to complement the central one. The shared path out of the door of the yurt or tipi is the child’s introduction to the outside world, but it also changes the space within, generating an implied axis. The place opposite the door is presented most directly to the incoming visitor, and so becomes the place of honour, where the head of the family and honoured guest take their seats. In addition, with both examples, although they come from different continents, the internal space is gender divided, men on the right and women on the left in the case of the tipi, the reverse with the yurt.4 An order of seniority may also be observed, increasing towards the place of honour. Social relationships and hierarchies take many forms, but nearly always carry spatial implications.5 The axis made by the door is usually also orientated so that the dwelling’s entrance faces the rising sun, though there may also be reason to avoid the prevailing wind or, in a communal settlement, to face the centre. But awareness of direction is crucial, as it relates the house and village to world and cosmos; to sun, moon and stars.

Figure 3.1.2 Plan of a Native American tipi Source: After Faegre 1979

Figure 3.1.3 Plan of a Cheyenne camp: north is top. The numbers 1–10 designate the position of different tribal divisions, A and B the religious lodges of the Medicine Arrows and Buffalo Cap, respectively

Source: After Grinnell 2008 [1923]

For hunter-gatherers, paths are needed, which become the starting point for roads: shared paths. Landmarks are necessary for finding one’s way and one’s way back, and so awareness of the topography is essential. Passes between hills and places to cross rivers are especially memorable, as are springs and water holes at which one can quench one’s thirst, or places with fruit trees or trees used as medicines, places good for game and places risky because of predators. Only with high densities of walkers is a permanent road generated merely by footsteps, and so, on a thinly populated continent, the way demands more subtle definition, moving from landmark to landmark, perhaps taking advantage of animal trails. But even with as sparse a population as constituted by the Australian Aborigines before European arrival, there was a complete network of known paths right across the continent, which allowed peaceful relation with others, respecting their rights and practices and intermarrying with them.6

The central principle, the linear one, or both, are needed to define a space of action. As the child is never alone, this is social from the start and may begin with observations of the comings and goings of others and gestures of greeting and eye contact. As consciousness grows, so does the awareness of the relationships between people’s bodies and the paths they routinely take. In the tipi, for example, people were expected to move in a clockwise direction, and there was a particular order to be respected in the passing around of the pipe of peace.7 The choreography of activities matched the organisation of space, each supporting the other. To put it another way, the space was accompanied by implict rules about its use as understood and enacted by the users. Such rules did not need to be declared explicitly, for they could be learned through observation, but persons charged with the laying out of space (in this case, the setting up of the tent) had to know them.

The relationship between space and social choreography has not ceased in modern societies, but it is more complex and difficult to trace and, therefore, perhaps most clearly visible under the most marginal of conditions. The game of hopscotch, for example, is constantly rediscovered in different forms by children across the world. It needs a pitch marked on the ground, against which your footsteps and my footsteps can be measured.8 When we play it together, we recognise that we share knowledge of the rules, and, if it is my first time, I have just learned them from you. In this case, the defined space has just served as a demon -stration, a temporary bearer of knowledge about how space is organised for this purpose. All kinds of game and sport need marked out spaces, as defined by rules of play, and the scale is easily changed, as evinced by chess and chequers. The higher the social status of the game, the more pedantically rules tend to be enacted and space defined, but even children walking home from school can invent a football pitch by marking the goals with their coats and bags, which shows the presence of the shared idea.

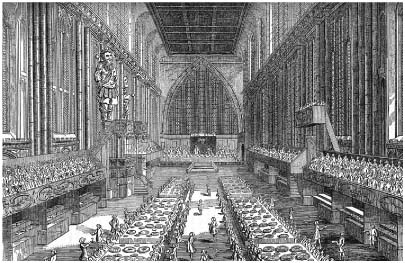

At the opposite end of the scale – the most definite and defined – is the Greek open-air theatre. That at Epidaurus is among the most enduring demonstrations of a multitude gathering around the few and, thus, of the central principle (Figure 3.1.4). Roundness tends to suggest togetherness and implies equal participation, which is why we talk about round-table discussions, King Arthur’s knights sat at the mythical round table, and the medieval chapter house was round or polygonal.9 Conversely, when a long, rectangular table is used for a meeting, the chairperson tends to occupy the end, which we customarily call the head of table, and this gives him or her added status. In the patriarchal Alpine farmhouse, the father of the family traditionally sat at the end next to God’s corner (the Herrgottswinkel or Coin du Bon Dieu), distributing food down the table, with the women on the left and men on the right, in order of age and seniority, and servants at the bottom (Figure 3.1.5).10 Kings, queens and judges preside in the highest seat, on axis at the end of the hall, which seems to be a universal, cross-cultural instance of hierarchy respecting the linear principle (Figure 3.1.6).11 The Chinese emperor in his audience hall, sitting at the centre of the forbidden city and at the culmination of the south–north axis, is an extreme example, following the central principle as well as the linear one, as he is also enfolded in many layers of walls and gates.

If, after millennia, Epidaurus exemplifies togetherness, it is sobering to reflect that its construction post-dated the golden age of Greek drama by several centuries, confirming an already long-established tradition. Monuments often have this consolidating and memorialising role and can catalyse the reactivation of the events for which they were intended. So, at

Figure 3.1.6 Royal banquet, Guildhall, London, with the Queen and Consort on axis

Source: From Thornbury 1872

Epidaurus, Greek drama is again being presented, to an audience arriving by car and coach. The theatre’s impressiveness lies in the way it is so spatially definitive, and not easily usable for other purposes. Theatre is thought to derive from the social rituals concerned with the harvest, and perhaps it is the choreography of those rituals, of bodies moving in space in a coordinated way, that first defined the nature of the setting.12 This was imagined in Goethe’s romantic reading of the classical amphitheatre, which envisaged people piling up carts and boxes to get a better view.13 A less imaginary and fascinatingly well-recorded example, involving almost no physical architecture at all, is the Walbiri Aborigine circumcision ritual, as witnessed by Mervyn Meggitt during the 1950s.14

The circumcision ritual was the most important social event, involving the whole tribe, as it marked, not only the transition of boys from childhood into manhood, but also the passing on of the tribe’s oral knowledge and their assurance of its continuity. It took place over several weeks, involving a long series of theatrical displays, with cult groups dressed up to present the stories of their Dreamtime animal ancestors. Meggitt includes a diagrammatic plan of the circumcision ground (Figure 3.1.7), marking the positions at which parts of the action took place and fires were lit to illuminate nocturnal performances. The space is just a clearing in the desert, scraped clear of scrub, with a low mound piled around the edge. It is linear and orientated to the setting sun, which symbolises the death of the child. The funnel-shaped east end accommodates the audience of women and children, and there is a sacred centre towards the west, where the actual circumcision takes place. This is sacred and forbidden to women and children, and so people come and go from the east. The choreography of the ritual dances is mostly organised along the central axis, sometimes with dancers appearing alternately from one side and the other to interweave, and, at one point, with a line of actors standing on the central line to pass the sacred symbol of territory above their heads, between their arms. Before use, the space is ritually defined by a man with a sacred board, who runs down the axis from one end to the other, knocking the instrument on the ground at each end. Meggitt gives too much detail to pursue here: the point is that, for this basic theatre to work, everybody must know where to be and what to do, and it is the temporarily constructed space that coordinates them. Some elder must know how to set it out and instructs the actors, and some children will learn about its use for the first time. Because it is hardly present and soon lost to the desert, its existence is fragile, but, while it exists, it frames the action and mediates between the participants. Without it, they could not organise themselves. It is a suggestive model for the origin of architecture in social order and choreography.

The combination of a linear path and a nesting series of layers around a centre necessitates the creation of one or many thresholds: house door, territorial gate, city gate, frontier. The very word points back to the beginning of our sedentary existence, when we started to depend on the precious harvest. Doors and gates have long been places for defining identity and possession, and also for ceremonies of arrival and departure and many other ritual practices involving good or bad luck.15 They are, therefore, always architecturally significant. Doors exclude as well as welcome, and the humble dwelling is in some ways the most exclusive of all, limited to family and invited guests. Even if we reject as archaic practices Black Rod’s ritual knocking on the door of the House of Commons, or a newly appointed bishop’s knocking on arrival at his cathedral,16 respect for the ownership of entries is still almost omnipresent, and nearly everyone in a particular cultural setting is aware of when he or she is trespassing. It is essential to know whether one is in or out of a territory, and how many layers one has penetrated. People can be guided by a written sign or kept out of a forbidden area merely by a flimsy piece of rope. We read these signals automatically. When we enter complicated buildings, we need to register our moves to be able to find the way out, and the sequence of remembered doorways marks the way.

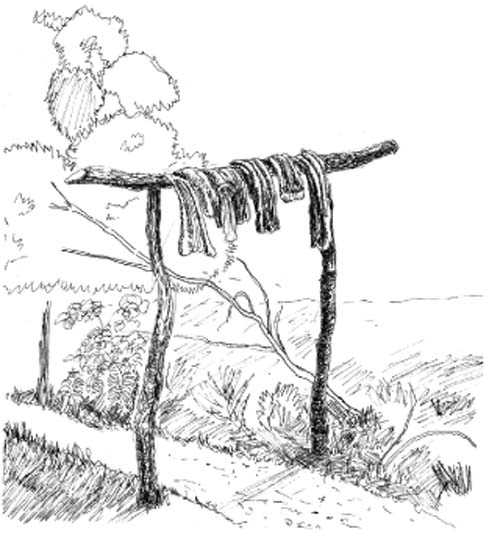

Carrying a bride across the threshold is still a familiar idea, and, in many parts of the world, it was thought to ally her fertility with that of the house, to avoid evil spirits or to mark the change in her life.17 Since Arnold van Gennep published his famous eponymous book in 1908, such life transitions have been called ‘rites of passage’, which also include birth, initiation and death.18 On his very first page, van Gennep links the metaphor of passage through life with the physical crossing of frontiers and thresholds, and this idea is widespread in literature, as, for example, with Tennyson’s poem ‘Crossing the bar’, or Dickens’s device in David Copperfield of a character dying as the tide goes out. Sometimes, rites of passage involve literal thresholds in support of symbolic ones, and again an anthropologist’s example can enlighten. Victor Turner, in his study of Ndembu initiation in Zambia in the 1950s, describes a special temporary gateway – the Mukoleku – made in the bush with two wooden sideposts and a lintel, which novice boys must pass through on their way to circumcision (Figure 3.1.8). It contains no door and interrupts no fence, and so one might call it a purely symbolic gateway, and yet it lies crucially placed on the border between the camp of separation and the actual site of circumcision. It is, therefore, as necessary in marking the prohibited boundary to the sacred site, warning women and uncircumcised males against accidental entry, as it is in registering the transition of the novices. As they pass through it, the boys remove their childhood garments and hang them on it, signifying their death as children, so that, until it decays, the Mukoleku serves as a memorial to this event. However, it also had a prior existence as a gate formed of bodies, for, before the wooden structure was erected, a ritual was held in the same spot in which the novices’ guardians were obliged to crawl through the tunnel of legs formed by the standing line of circumcisers. If, therefore, the Mukoleka was in the first instance a living gate, it subsequently became a physical gate and then, finally, a memorial of the rite that had occurred. The interchange between space of action, physical threshold and memorial is amply demonstrated.19

Figure 3.1.8 Mukoleku, the ritual gateway for a Ndembu circumcision: the initiates cast off their childhood clothes and hang them in it

Source: Drawn by Claire Blundell Jones after a published photograph by Victor Turner 1967

In a society living in grass huts, with no developed architecture, the Mukoleku stands out all the more. By contrast, the main tradition of Western architecture has never been short of free-standing symbolic gateways, not least the triumphal arches through which victorious Roman generals re-entered their city, but mostly, these places remember practices long gone. In the Eastern traditions, such gateways are even more prolific, especially in the example of imperial tombs of China considered in Chapter 3.5, in which the numerous freestanding gates may seem at first to contain nothing, but mark once-meaningful transitions across invisible layers of space.

1 Richard Gould, who lived with the Yiwara in the 1960s, has left a reasonably full description of making one, a process that takes about 2 hours: Gould 1969, p. 19.

2 The tipi is described in detail in Laubin and Laubin 1957/1989.

3 Examples shown and described in Fraser 1968 are derived from Grinnell 1923; the relevant description is carried over to Grinnell 2008, p. 132.

4 This apparent contradiction is common, because, when I enter a space, I may expect more important things to be on my right, but, when I turn around and my honoured guest sits to my right, he is, from the point of view of a person entering, on the left. Bourdieu comments on this in his essay on the Kabyle house, under the notion of ‘the world reversed’; see Bourdieu 1977.

5 Torvald Faegre’s book on nomadic architecture gives numerous variations with plan drawings; see Faegre 1979.

6 Spencer and Gillen 1899.

7 Laubin and Laubin 1957/1989, pp. 113–14.

8 I remembered this from Rykwert 1976, but cannot find the reference. Wikipedia and allied websites report numerous versions worldwide and possible origins in a Roman military drill, though Chinese origins are also suggested.

9 On the roundness of prehistoric buildings, see Bradley 2013.

10 Reported in Rapoport 1969, p. 54, drawn from Weiss.

11 Dictators such as Hitler and Mussolini pushed it to an extreme to bolster their power, but British democracy in the Palace of Westminister sets queen against speaker on the same axis, following a nineteenth-century interpretation of the balance of power.

12 Wilson 2007, Part 1.

13 Goethe 1970.

14 Meggitt 1962.

15 Countless interesting examples are collected in Trumbull 1896, even if his theory is greatly outdated.

16 On Black Rod, see Bond and Beamish 1976; on Archbishop Welby’s knocking on the door, see: www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-21876249

17 A very elaborate version can be found in Bourdieu’s essay on the Kabyle House, Douglas 2003, pp. 98–110. A longer version of this essay was originally included in the Outline (Bourdieu 1977), but omitted from the English version, perhaps because it had already been included in Bourdieu’s more obscure Algeria 1960.

18 Van Gennep 1908: a good introduction to the subject is the essay ‘Rites of passage: Process and paradox’, by Barbara Myerhoff, in Turner 1982, pp. 109–35.

19 Turner 1967, pp.151–279.