10 Seydou Keïta, Untitled, 1958/9. This image, among Keïta’s best-known, displays the aspiration towards modernity and close connection with French as well as indigenous ideals of beauty and status in late-colonial Bamako, Mali.

The introduction considered the continual renegotiation between the past and present in relation to precolonial art forms. This chapter introduces new genres of art that owe their emergence to three of the social processes that accompanied European colonialism in Africa: urbanization, the introduction of Western technology and material culture, and the expansion of literacy through formal schooling. To these must be added a fourth, considered fully in Chapter 5, that underlies all of these changes: the development of an ‘art market’ under European patronage. The first three set the stage for the development of a new, town-and-literacy-based popular culture, while the fourth pronounced certain of these developments ‘art’ and introduced them into institutionalized art-world settings.

The creation of large urban centres where none existed before, as well as the transformation of older, precolonial cities, brought together people from a plethora of ethnic groups and different visual and performance traditions. While most city dwellers in Africa have continued to retain strong ties to the upcountry communities where they originated, unlike their relatives in the rural areas they are no longer essentially self-sufficient. Instead, they depend upon salaries, wage labour or various forms of entrepreneurship to provide them with food, clothing, rent money and school fees, as well as whatever luxuries they can afford. While African cities have produced a large class of unemployed and under-employed workers, they have also created a distinctive urban class of consumers whose tastes and aspirations are different from those in rural areas and are frequently shaped by ideas and goods from the colonial (and ex-colonial) metropolis. These ideas and goods are creolized and reinvented in an African cultural setting that is distinctively different from the European one from which they originated. Not only are Western ideas and goods appropriated, but extensive cultural borrowing and reinterpretation also occurs among the many indigenous subcultures that make up the urban centre. To add further to the complexity, these cultural imports no longer come only from the former colonizing countries in Western Europe. Since independence, African markets have been saturated with cheap manufactured goods from China and other Asian countries and from Eastern Europe, and in many other respects, it is America and the African diaspora that are the sources of the most powerful images of modernity – not only clothing, hairstyles and luxury goods, but also musical styles such as reggae and rap, and in the colonial period, jazz.[12]

10 Seydou Keïta, Untitled, 1958/9. This image, among Keïta’s best-known, displays the aspiration towards modernity and close connection with French as well as indigenous ideals of beauty and status in late-colonial Bamako, Mali.

New arts and goods, new political awareness and daily contact with imported media were part of this urban subculture right from its late nineteenth-century beginnings – radios, newspapers, Bibles, telephones, postal systems, identity cards, imported foods (both crops and cuisine), bars and Western fashion all took root and in due course were transformed into local versions, some highly distinctive and others emulations of their European counterparts. In recent decades, imported films (often produced for ‘Third World’ consumption) and pirated music have become ubiquitous in African cities, while both imported and locally produced television programmes have found a ready market among urban consumers. Countries such as Nigeria, Ghana and South Africa have their own music and film industries. Indigenous filmmaking for international audiences has been limited mainly to South Africa and francophone West African countries such as Mali, but is sporadically developing elsewhere. In Nigeria, for example, the emerging film industry began with Ministry of Information documentaries and locally produced television dramas, which, in turn, were modelled on live performances of plays by local theatre troupes.

These new visual genres, like their counterparts in literature and oral culture, call for their own modes of interpretation, which are inevitably different from those applicable to older forms. Not only are the new genres frequently created out of materials and techniques not used in older ones, but they may also involve different production conditions. To paraphrase Elizabeth Tonkin’s argument about oral performances, while genres have certain ‘repeatable and stereotypic features’, they will be misunderstood if they are treated solely as expressive forms in themselves, detached from their production conditions. This is one reason why exhibitions of contemporary African art are so frequently misunderstood by both critics and the public, who see them only as ‘detribalized’ aberrations from tradition.

One major difference between francophone and anglophone countries in Africa stems from their distinctive colonial policies. The British policy of Indirect Rule, constructed by Lord Lugard after the First World War, stated that ‘native peoples’ (as they were described in the colonial documents) should be allowed to accept change at their own rate and in their own way. To implement this, British colonies were to be governed by indigenous rulers at district and local level. Indeed, where there were not any such local rulers, the colonial government created them by appointing salaried ‘white men’s chiefs’. Among other things, this meant there could be little British influence on everyday life and material culture. The French, on the other hand, tried consciously to acculturate the African populations of their colonies, making them citizens of France – the effect of which is readily seen today in the French influence on styles of dress, food and entertainment in urban areas. The Congolese sapeur, who imitates the latest Parisian men’s fashions in dress down to the smallest detail, has no counterpart in anglophone countries. The difference between French and British territories was most obvious when a single people was divided between the two. The Hausa homeland, for example, includes both northern Nigeria (a former British colony) and southern Niger (a former French colony). On the Niger side of the border, French baguettes were still being sold on street corners by Hausa traders in 1980, while on the Nigerian side, street vendors hawked traditional Hausa sweetmeats. Conversely, Hausa architecture is much better preserved on the Niger side, due to the French enthusiasm for mosque preservation programmes, inspired by architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, while in Nigeria buildings are crumbling, subject to the vicissitudes of weather and local politics.

Goods from abroad have had at least two major effects: they have turned Africans into global consumers and they have in certain areas strongly undercut local manufacturing traditions. This is most noticeable with locally made pottery, weaving and ironworking, all of which have been partly displaced by imported enamelware and plastic, factory-made cloth and mass-produced hoes and other iron implements. Goods that have survived this competition are specialized and particular to local cultures – certain types of prestige cloth used in ceremonies, elaborate leatherwork for horses or ritual pottery and iron ornaments, with which foreign manufactured goods cannot compete.[11] Where patrons have continued to demand them, these types of goods are still being made. Handmade crafts also survive, and occasionally flourish, particularly in areas far from urban markets where manufactured goods are expensive and hard to come by. Local goods that are easily and relatively cheaply replaced – handmade but strictly utilitarian clay pots for cooking and carrying water, or knives and hoes made by local blacksmiths – have disappeared on a large scale, giving way in most cities and rural areas to aluminium pots, plastic jerrycans and hoes imported from China. However, both old and new types do often coexist in the same community and even the same household.

11 A Hausa trader selling dyed leather horse trappings, Kurmi crafts market, Kano, Nigeria, 1989

Urban Africans are not only consumers and patrons of the new visual media, they are also its producers. In African cities, a majority of workers are employed in what economists call the ‘informal sector’, which includes all those businesses and industries, usually small-scale and conducted in alleys and marketplaces rather than in factories or offices, that operate without formal structures.[13] Among them are the sign-painters, furniture makers, blacksmiths, tailors, photographers, builders, drum makers, woodcarvers, street painters, jewelers and producers of all manner of curios from banana-fibre pictures to soapstone elephants. ‘Recyclia’, goods handmade from previously used materials, account for a good deal of this production, some of which is traditional (cow tails transformed into fly-whisks), some ingenious (Christmas-tree decorations used as hair ornaments), some merely cheaper substitutions (plastic replacing ivory ornaments) and some driven by utility (suitcases made from discarded rolled sheet metal). In Kenya, all these forms of material culture production, as well as related kinds of small-scale artisanship such as bicycle and radio repair, are known collectively as Jua Kali (Swahili: ‘hot sun’), which refers to the informal outdoor spaces where they are practised.

12 Ghanaian ‘expensive cut’ barber’s sign advertising the ‘flat-top’ hairstyle fashionable in the USA in the 1990s

13 A sign-painter’s kiosk, Government Road, Mombasa, Kenya, 1991

To understand fully that these urban forms are simultaneously art and commodity, historian Bogumil Jewsiewicki argues, one must re-examine the assumptions implicit in most critical discourse in the West. The most deeply grounded of these is the belief that an artwork ought to be singular – a one-of-a-kind creation. The other assumption is that an artwork is not a commodity (see Chapter 5). Much of the art being produced in Africa, especially in urban workshops, is marketed unpretentiously as merchandise. It only begins to take on an ‘art’ status when it becomes part of Western or elite collections.

Perhaps the best-documented example of a quintessentially urban genre enjoying both art and commodity status is the flour-sack paintings of Kinshasa, Kisangani and Lubumbashi, Congo (then Zaire), made during the 1970s.[14] The artist-entrepreneurs who made them originally created pictures for a clientele not very different, in economic and social terms, from themselves. Paintings on flour sack stretched over a frame were carried about and marketed on the streets, often by young boys working for the painters, and were intended for a local audience of urban workers and clerks. But given the vast distances and poor communications in a country such as the Congo, both the thematic content and the primary audience for this art populaire varied from place to place.

In Kisangani, the major city in northeast Congo, the invasion of paratroopers during the attempted Katanga secession became a popular theme for urban paintings. Historical themes such as this and the 1961 assassination of the Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba have been more characteristic of the eastern mining-zone cities than of Kinshasa.[15] Even though there is little or no tourist or foreign patronage, a market for paintings has also developed among an emergent entrepreneurial class involved in gold trafficking. Much more recently, a parallel genre has begun to develop at Kilembe copper mines in western Uganda. In Kinshasa, both themes and patronage have been more wide ranging. Gradually, as a few foreigners – scholars, journalists, resident expatriates – noticed and purchased the work of these street painters, it became known among a small group of cognoscenti and its status grew from straightforward decoration for the clerical worker’s rented rooms to collectible art. By this process of recognition, a few such artists gradually developed an international clientele as well as a local one.

14 Chin in front of his workshop, a popular painting studio, in Kinshasa, Congo, 1990

The most widely known of these, Chéri Samba (b. 1956), has emerged in critical circles as a highly successful painter following his inclusion in the ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ exhibition held in Paris in 1989. Prior to his ‘discovery’, Chéri Samba created flour-sack paintings for a Kinshasa audience. Moralizing was a dominant theme even in his early work, played out in popular stories such as that of La Sirene (the mermaid or Mamba Muntu, or in West Africa, Mami Wata, ‘mother of the water’).[16] The central icon of La Sirene is a voluptuous mermaid accompanied by snakes, who is usually represented in opposition to such symbols as the Bible. In Chéri Samba’s work, the moral dilemma is explained by text panels at the top or bottom of the picture: if one follows her one will become rich easily, but a high price will have to be paid for the transgression of moral principles which this implies. Chéri Samba also places himself in the narrative, by including a self-portrait figure who is speaking or reading the Bible near the upper edge of the picture space. Anthropologist Johannes Fabian regarded La Sirene as a representation of colonial power itself – distant and foreign (she has often been depicted as a European woman), capricious and arbitrary – hence her particular popularity in urban settings. Unlike the African rural farmer or herder who is largely self- sufficient, the urban worker is much more dependent upon the largesse and competence of the government (whether colonial or postcolonial), which controls the prices of basic commodities, local transportation, the water supply and many other things that can make the worker’s life either comfortable or miserable. La Sirene symbolizes, among other things, this unstable and unpredictable aspect of urban life.

From the late 1980s, Chéri Samba’s developing reputation among collectors allowed him to begin painting in acrylic on canvas. Many of his themes have continued to deal with the problems of urban life in Africa, from prostitution and AIDS to potholed streets. He has also commented eloquently on the desire for the acquisition of European goods – television sets, upholstered furniture, fashionable clothes – as well as on the dangers for Africans of European social behaviour. Both moralist and humourist, he has made himself the subject of his own incisive visual commentaries, as in his 1990 painting Why Have I Signed a Contract?, in which the artist, well-dressed and now obviously successful, is being pulled in opposite directions by ropes tied around his neck, which plainly represent the shackles imposed by an exclusive gallery contract.[17]

15 Tshibumba Kanda-Matulu, The Historic Death of Lumumba, 1970s. Beginning in 1973, Tshibumba Kanda-Matulu made a series of one hundred paintings on the history of the Congo, then Zaire, for the anthropologist Johannes Fabian – among them this image of the 1961 assassination of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba.

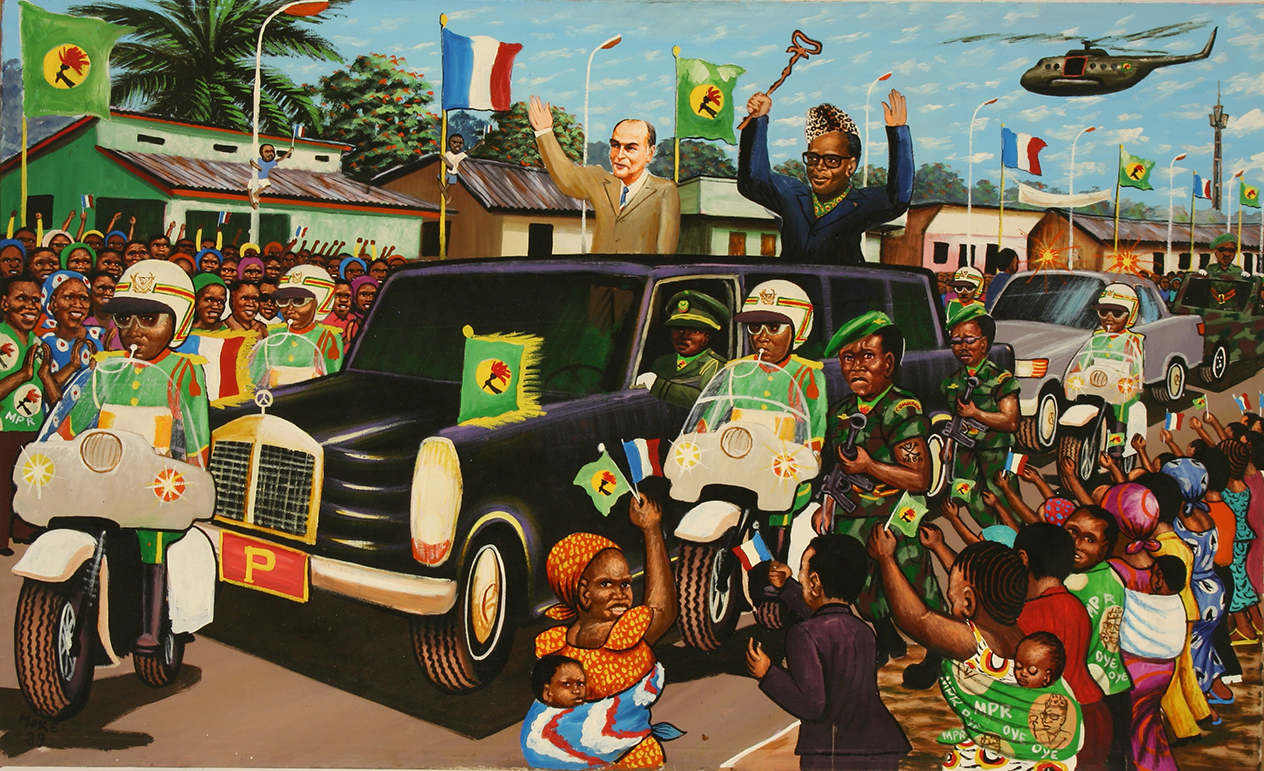

While Chéri Samba is the best known of the Kinshasa painters, his international success and his original choice of thematic subject matter make him atypical. Many themes popular with painters and their audiences in the 1970s and 1980s (the period when most of the work discussed here was collected) represented the inequalities of power under the colonial regime and subsequently in the postcolonial era. The subjects of urban Congolese painting encompass a wide repertory, from the idyllic representation of rural life in an unspecified time past, to parables of the colonial condition and postcolonial dictatorship spelled out in narrative and couched in a form that draws upon the collective memory of ordinary citizens. Unlike the work of Chéri Samba, paintings such as Moké’s Motorcade with Mitterand and Mobutu (1989), with its threatening symbols of sinister authoritarian power, are not about the encounter with modernity as epitomized by city life and material goods, but stand as witness to the political violence of the twentieth century.[18] Zambian artist Stephen Kappata (b. 1936) has explored the same range of pictorial themes as Moké and Chéri Samba, from his recollections of the late-colonial experience in Barotseland to the encounter between modern Zambian politicians and ‘traditional culture’ in the 1980s.[19] Kappata employs the flat perspective and linear narrative associated with ‘naive’ painters, but with a self awareness that is usually missing in their work.

16 Chéri Samba, La Seduction, 1984

17 Chéri Samba, Why Have I Signed a Contract?, 1990

18 Moké, Motorcade with Mitterand and Mobutu, 1989

19 Stephen Kappata, A Country without Her Own Traditional Culture is Dead Indeed, 1987

In contrast to these genres, the depiction of an idealized Africa undisturbed by change and epitomized in scenes of rural domestic life has had a wide currency with urban painters far beyond the borders of the Congo. Not only are such subjects very popular with tourists and expatriates, but they are also common in the homes of the African middle classes. They are painted by street artists (‘autodidacts’) in such places as Congo, Uganda, Kenya and Zambia, and also by workshop and academically trained artists. The street genres have been translated into banana fibre and batik, which have become the quintessential media for tourist versions of these themes. But it would be short-sighted to assume that their predictable appearance on the urban scene throughout the continent is entirely market-driven. We must also consider why Africans themselves wish to display these pictures, and why they have currency for artists who do not view their work as merchandise. Scholars such as Fabian and Bennetta Jules-Rosette see the idealized rural village as part of a larger phenomenon involving the historical and political themes of Zairian urban painting – so the village scenes are assimilated into a visual history of the past which extends from mythic time through colonialism and up to the present. They operate in a similar way to the images of La Sirene or Mami Wata – they can be read purely as narrative description (the way they would be read by an outsider such as a tourist), but they symbolize something else for their local audience. Regardless of where in Africa they are made, idyllic rural narrative paintings can lay claim to several possible readings, which vary according to the experience of the viewer – for instance, a collective social memory of an actual rural past (a recent experience for many urban dwellers), nostalgia for ‘tradition’ (a quite different reading requiring social, spatial or temporal distance on the part of the viewer), a cultural ideal of harmony couched in a rural family idiom, an escape fantasy driven by grinding urban poverty, or even a symbolic rejection of anything Western. It is this shifting quality – the ability to be interpreted on several levels – that has made the rural genre scene a viable choice for so many types of artists and audiences in so many places.

20 Landscape, early 1970s. Though signed by Tshibumba Kanda-Matulu, according to Bogumil Jewsiewicki it is more likely to have been painted by Burozi, the oldest of the flour-sack painters.

An important question raised by the case of the Kinshasa painters, and especially by the success of Chéri Samba, is what is ‘popular’ painting in the African context? If popular art is indeed something produced by ‘the people’ (in the sense of wananchi, i.e. ordinary non-elites) and for ‘the people’, one would have to conclude that financial success in the form of gallery patronage would exclude an artist from this category. The ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ exhibition and Chéri Samba’s debut there created an international audience for whom he was a major ‘discovery’. In turn, this audience, composed of foreign collectors, scholars and critics, is fundamentally very different from the flour-sack painters’ original audience – urban petit-bourgeoisie. Artists in Africa are both driven by, and limited by, the patronage they are given. Chéri Samba and others lucky and talented enough to be ‘discovered’ abroad have found new themes and techniques, as well as new financial success, and inevitably this has meant that their audience has shifted from a ‘popular’ one (in the sense of ordinary urban dwellers) to a more international one. This is not to say that such artists no longer feel attuned to the local scene and people – Chéri Samba has been emphatic that he is a ‘Kinshasa man’ – but that the focus of their creativity may alter to include other issues and arenas, and if they wish to maintain their ties to a local clientele, they must adopt a two-tiered strategy for making, pricing and marketing their work. The result may embrace two different genres being produced by the same artist – a practice discussed in Chapter 5.

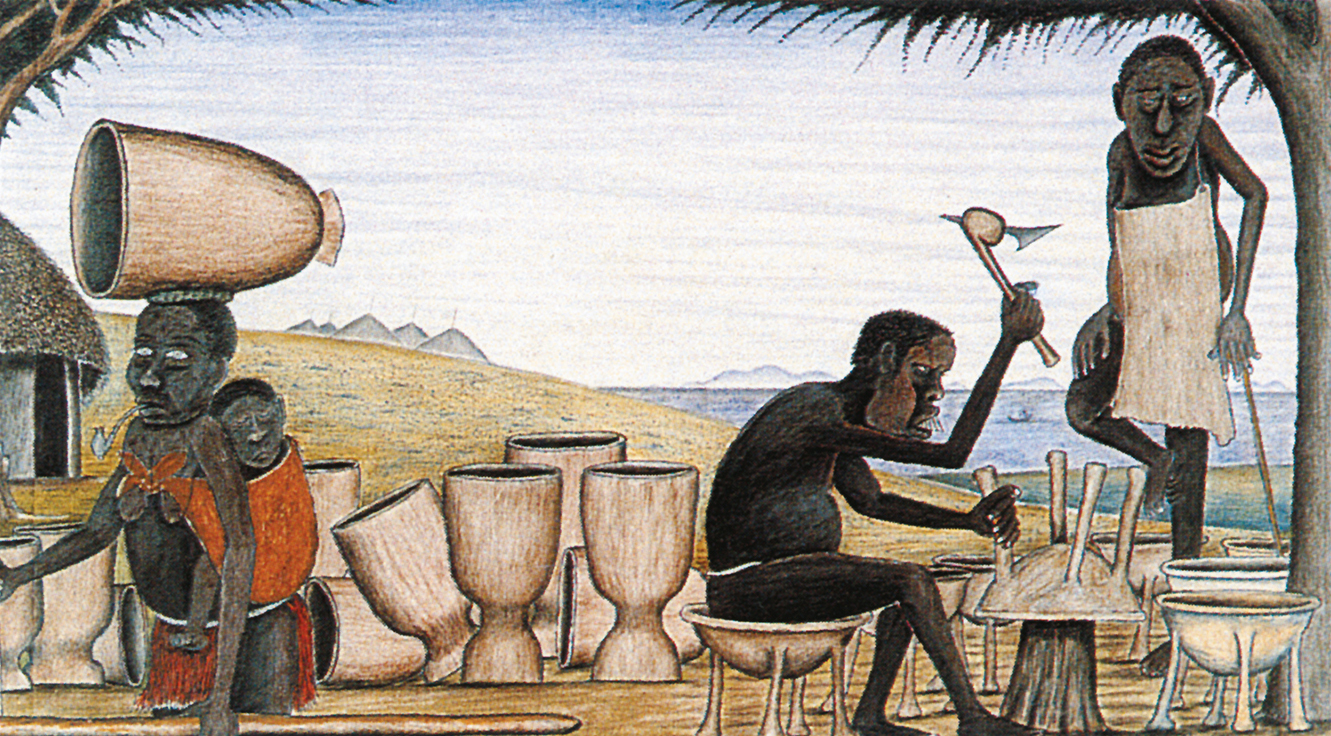

21 Joel Oswaggo, The Stoolmaker, c. 1987. Oswaggo, an artist from Western Kenya, has said ‘All my drawings are based on the ancient times and how those ancient people lived.’

An almost identical situation has arisen in the marketing of popular music in countries that have been ‘discovered’ by Western performers, impresarios and audiences. Recording stars such as Alhaji Chief Ayinde Sikiru Barrister and King Sunny Ade in Nigeria often produced one version of their music (both live performances and studio recordings) for local consumption and another for export, each geared to the tastes of the target audience. The production and marketing of exported music has become intertwined with the Western-based ‘world music’ industry in a way that reflects former connections between colony and metropole: Salif Keïta (Mali) and Angélique Kidjo (Benin) make their export recordings at sound studios in Paris and under contract to Western producers. In the same way, successful artists such as Chéri Samba have found themselves enmeshed in the Western gallery system to exhibit and market their work. This often has unexpected consequences, usually to the dismay of the African artists involved. Commercial galleries abroad frequently hold unsold work by African artists for years without either returning it or compensating them financially. Because artworks that circulate abroad are usually one of a kind, they are vulnerable to unscrupulous practices in ways that musical productions are not, though the latter also fall foul of contractual obligations, which often replay the former economic inequalities of colonialism.

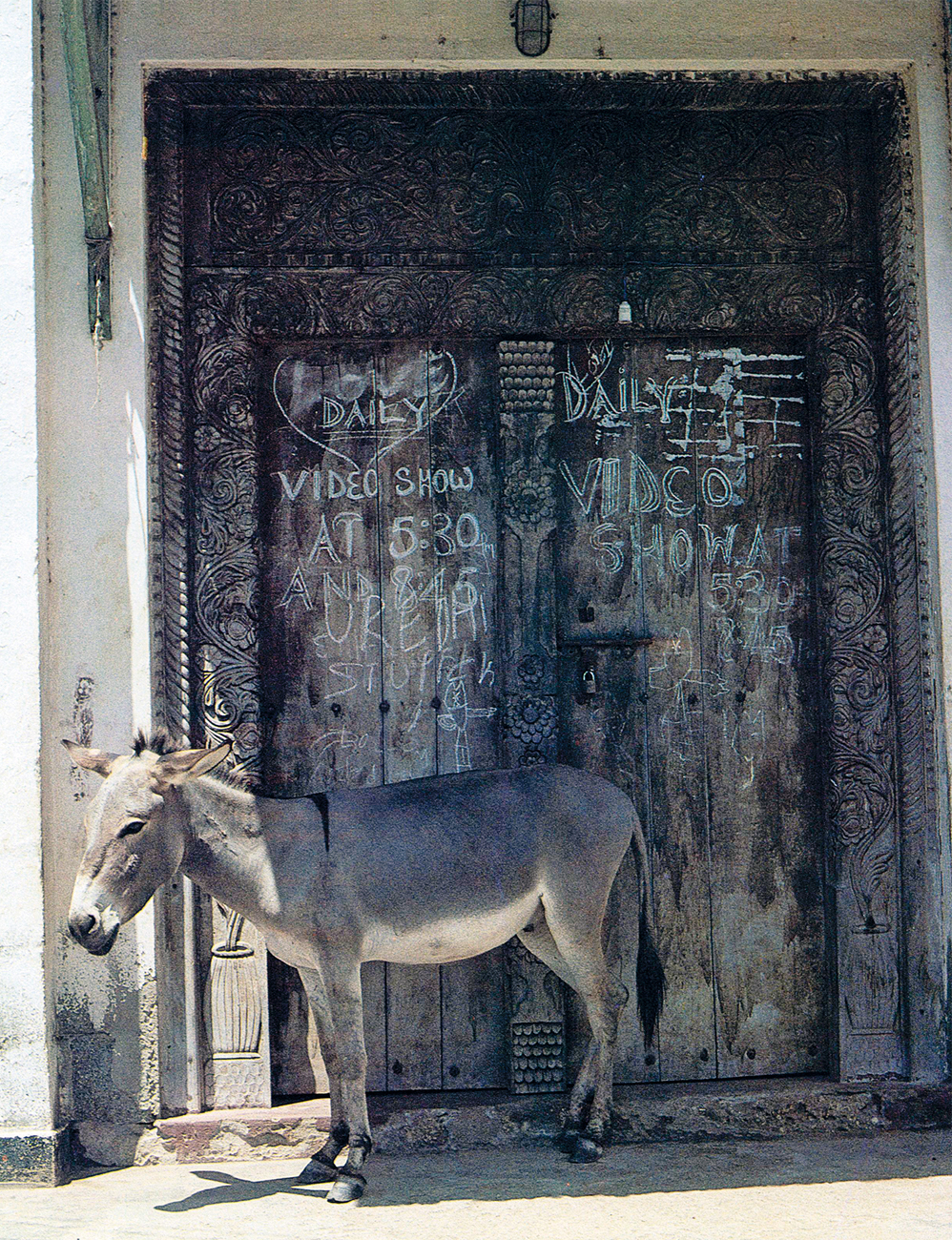

22 A nineteenth-century carved door on Lamu Island, off northern Kenya, with a chalked message advertising a ‘video show’.

While ‘popular’ cultural production in the newly postcolonial Africa of the 1960s and 1970s was intended for newly literate audiences of urban workers with strong ties to rural cultural idioms and values, popular culture has since been moving steadily towards an increasingly sophisticated audience with strong interests in electronic media such as film and television. The most stunning example of this shift has been the phenomenon of Yoruba travelling theatre. This started as a group of itinerant troupes who staged their repertory of plays in towns all over southwestern Nigeria, but, since the 1990s, filmed performances of the plays have instead travelled from town to town, not just in Nigeria but internationally.

How did this happen in the space of twenty years? Partly responsible was the new video cassette recorder (VCRs), which proved to be enormously popular in urban Africa just as in other parts of the world. Africans with the means to travel abroad brought them home as a way to circumvent the limited programming on local television and even more limited film offerings in cinemas. With Yoruba popular plays, the new technology was given its initial impetus through locally produced music videos, which are in turn a by-product of a large and competitive Nigerian music industry. Any African community urban enough to have electricity could have a ‘video theatre’, often simply a room with chairs and a VCR attached to a television screen.

A second factor was Nigeria’s downward economic spiral since the oil boom of the late 1970s. Under such conditions, it made perfect sense for the Yoruba travelling theatre troupes to cut their production costs and videotape their performances, which could be seen by a much wider audience, including Yoruba communities in other parts of Nigeria and beyond – some of these recordings have now made their way onto YouTube. Such a video could, in the words of one Nigerian performer, ‘walk on its legs’ from town to town. Itinerant theatre and music take numerous forms in Africa, most of them a good deal more low-tech than this. Popular theatre performances in Ghana are part of larger entertainments known as Concert Parties, and have produced a distinctive poster art which is used to advertise the performances and draw customers.[23] As such it is both commodity and expressive vehicle for the play. The road life of a poster (known locally as a ‘cartoon’) is short, as it must be stowed in the back of a lorry, but the best artists, such as Mark Anthony (b. 1943), also paint smaller versions on flour sacking which are intended for an art market of foreign collectors.

23 Mark Anthony, Farmer saved by an Angel, 1995. This poster advertises the play Some Rivals Are Dangerous by Super Yaw Ofori’s Band, Ghana.

Film and television have made major inroads into non-performative visual media as well. The urge to decorate a flat surface has led, as the Congo example shows, to murals being painted on the walls of urban buildings such as bars, hotels and cinemas, and to painting buses and lorries. In Nigeria the painted or low-relief decoration of mud-wall surfaces in rural settings was usually an art practised by women as an extension of their activity as potters and house builders or body-painting artists, but these new genres of mural painting are largely the province of young men raised on Kung-Fu, cowboy and Rambo films. As film characters move in and out of fashion, so too do their images as a subject of tailgate mural art.[24] Thus Django, a popular hero of Italian Westerns in the 1970s, who was depicted on Nigerian lorries of that period pulling his coffin containing his deadly machine-gun, faded from the truck art repertory of the 1990s, as did the deadly shark inspired by the film Jaws (1975).

Representations that employ local images of power and violence, such as lions and elephants, rather than imported ones of weapons and fighting, are more durable. In Kano and Kaduna in northern Nigeria – important centres for long-distance trade and hence lorry construction – these images include mikiya, a well-known representation throughout Muslim Africa, and the hawk, the subject of Hausa folktales.[25] In Yorubaland (southwestern Nigeria and Benin), the lion has long been a common subject of lorry painting. In the 1960s the lion was usually heraldic in form – derived from the nineteenth-century Afro-Brazilian architecture in Lagos – but gradually, under the influence of books, magazines and films, it has been incorporated into narratives of action. A second kind of power image employs the paraphernalia of real or imagined Western material culture – radios, bicycles, sleek motor vehicles or pistols, ammunition belts and holsters. A third, more prosaic, type of truck art straightforwardly advertises the products the vehicle transports, such as giant, perfect carrots or tomatoes. Even these, however, take on a specifically local character in their use of signage to contextualize the imagery.

24 Tailgate mural depicting Django, the Italian cowboy-film hero, northern Nigeria, late 1970s

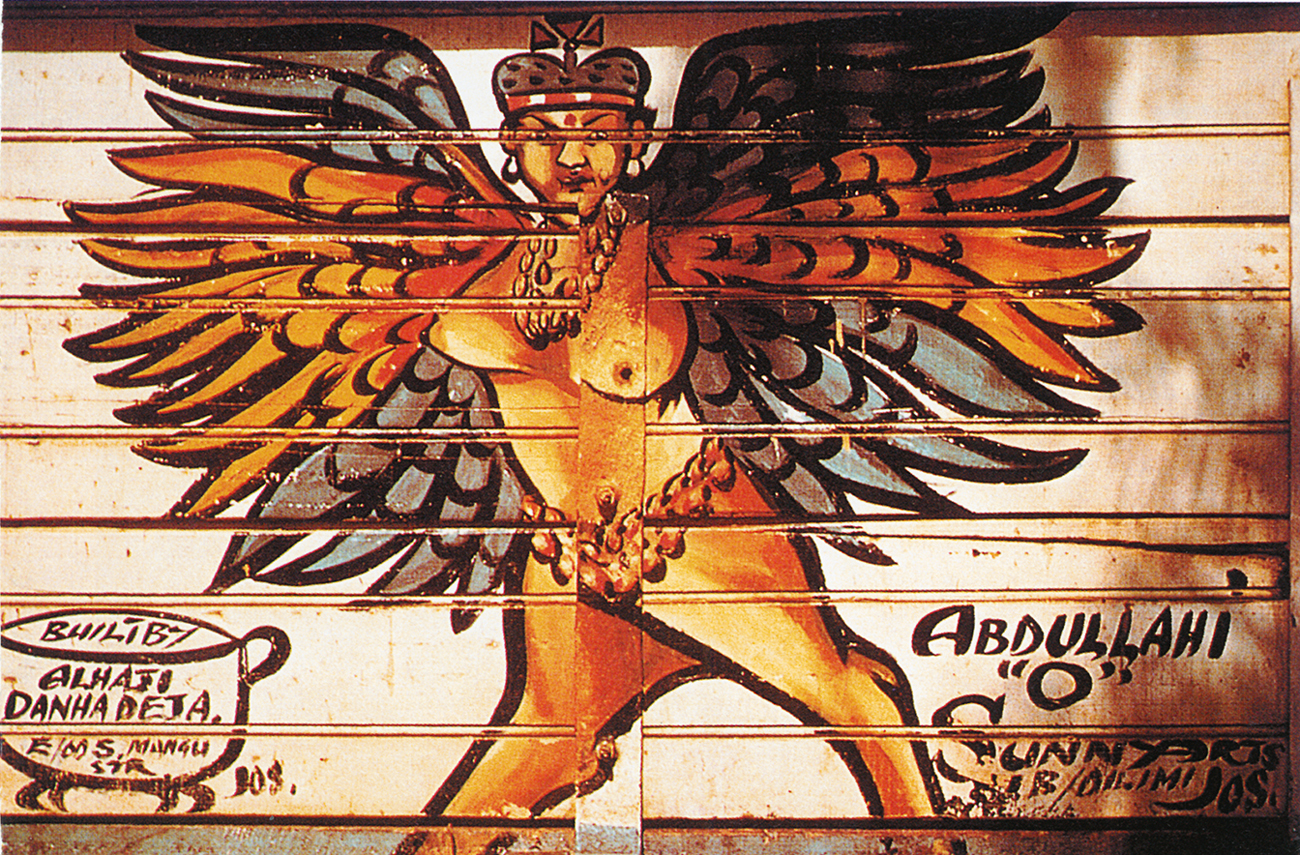

25 Abdullahi ‘O’, tailgate mural depicting mikiya, a power symbol in the Islamic north, Jos, northern Nigeria, late 1970s. The combination of human and animal features is visually similar to images of La Sirene or Mami Wata.

26 Babie Coach, Maralal, northern Kenya, 1996

Painted tailgate murals are not found everywhere in Africa, but the ubiquitous passenger vehicles, such as minivans, lorries and buses, are themselves icons of modernity and have become moving representations of urban culture. In Nairobi, the matatu (minivan) is the fastest and most convenient mode of transport between city and suburb; passengers are submitted to the brash behaviour of touts and loud popular music played on the driver’s radio. One could say without exaggeration that buses and lorries in Africa serve as portable stages for the encounter with modernity. In cities, they blend into an already heterogeneous mix of people and goods; in the hinterland, their appearances herald the arrival of an urban, commodity-driven way of life and serve as magnets for small-town youth. In Nairobi, matatus nowadays are painted with portraits of international soccer stars, representing yet another shift in popular interest as they replace the cowboy and Kung-Fu heroes of an earlier generation.

Due to the influx of various print media since the beginning of the colonial period and the widespread impact of literacy, text messages are often combined with visual images on these vehicles as well as in other mural work and smaller-scale paintings. Language is powerful whether spoken or written, and everywhere in Africa, lorries and buses display slogans and messages. In Nigeria, many are Islamic or Christian: ‘Allah ya kiyaye’ (Allah Protect Us), ‘Jesus My Protector’, or more cryptically, ‘Psalm 100’. These reflect the dominance of Hausa Muslims from Kano and Christian Igbo traders from Enugu in the long-distance trucking business, but also the real danger that road travel represents. Accidents are frequent and unlike in most countries, wrecks in Nigeria are left at the roadsides indefinitely, grisly reminders to other drivers and passengers of the possibility of sudden death.

Other slogans refer to the film characters depicted in the mural images – ‘Rambo’, ‘Challenger’ – or to the lorry or passenger vehicle itself, struggling against the odds presented by threadbare tyres, worn-out parts and untarred, potholed or flooded roads: ‘Road Warrior’, ‘No Fear’ (both Kenya). Others offer popular philosophy: ‘God’s Case, No Appeal’ (Nigeria), ‘No Condition is Permanent’ (both Ghana and Nigeria), ‘Fear Woman’ (Ghana) and ‘No Molest’ (Nigeria). In response to the frustrations of travel, or life in general, there is ‘No Hurry in Africa’ (Kenya), or the verbal shrug, ‘Ba Kome’ (No Matter) in Hausa (Nigeria) or ‘Hakuna Matata’ (No Problem) in Swahili (Kenya and Tanzania). Another, more recent, genre of messages and slogans in eastern Africa relates to the dangers of AIDS and reflects the fact that its main path of propagation there has been the truck route around Lake Victoria, which passes through Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania: ‘One Man, One Wife’, ‘Think First’ and ‘Zero Grazing’, which literally means ‘keep cows at home instead of putting them out to pasture’, but in Kenyan popular speech is a reference to marital fidelity.

Related to these mural forms and slogans on vehicles are the adverts that appear on roadsides, bars and hotels. Advertising art has two very different forms in most African countries – the features and layouts on television, roadside billboards (hoardings) and in glossy magazines, which closely emulate their Western counterparts, substituting African elite subjects for Western subjects, and the locally produced sign art which, like vehicle murals and slogans, reflects more directly the encounter between modern life, commodity and the African artistic imagination. While this kind of advertising would be expected in the unplanned urban sprawl of colonial cities like Nairobi and Johannesburg, it has also become a part of the visual environment in old cities like Mombasa and Lamu in Kenya, Djenne in Mali and Zaria in northern Nigeria. While some representations are homegrown and relate to local customs, people and places, many others are hybrids born of Western cinematic images and imported music, such as reggae, which has its own visual symbols associated with Jamaican Rastafarianism, but is itself a creolization of African symbols.

Sign artists rarely achieve an art-world reputation – despite the popularity of signage, particularly barbers’ and hairdressers’ signs, among collectors of contemporary African art, the work is not usually connected to a named artist when exhibited. Most commonly, it is treated as anonymous folk art, which allows it to be absorbed into either the notion of commodity suggested above or a fictionalized Western colonial idea of the ‘primitive artist’ as being one without individuality of style or even a traceable identity. Sign artists are firmly situated in the informal sector, on the street, and within a matrix of entrepreneurial activity that surrounds much urban popular art. One example of this was a painter who signed his work ‘Abdullahi “O”’ and was part of a lorry-painting firm based in Jos called SunnyArts. Abdullahi, whose specialities were Kung Fu and cowboy figures, was known all over northern Nigeria in the 1970s and 1980s because of the mobility of his art form.[25]

The work of Middle Art (Augustine Okoye), from Onitsha in eastern Nigeria, came to the attention of Ulli Beier, an important patron of Nigerian artists who was then at the University of Ife. In the 1960s Middle Art was lifted out of obscurity and his work exhibited as art rather than commodity. Sign art, when recontextualized in an art gallery, moves closer to the genre of popular paintings that contain text, such as those of Chéri Samba. While sign text usually advertises goods or services, and text included in paintings is usually an explanatory device to heighten their visual narrative, they both rely on the interplay between visual and verbal messages in an effort to attract an audience which is newly literate. It is not surprising, therefore, that Middle Art was able to cross the somewhat blurred boundary between the two genres to produce images that were no longer tied to advertising, such as his commemorative painting of Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna of Sokoto – a full-length portrait painted on plywood, in which the head is probably based on one of the official photographs of the Sardauna found in shops and homes in Nigeria’s northern Emirates.[27] Middle Art’s style combines a strong concern with the accuracy of small details, such as the Sardauna’s garments, with a lively realism achieved partly through the placement of the main figure very close to the viewer’s space, and partly through the careful modelling of the face after a photographic likeness. The very strong presence this creates is then placed within a narrative framework using the message of the text.

The urban sign artist’s work is marked by its place of origin. Middle Art’s home and usual place of business was Onitsha, a sprawling town on the Lower Niger River which was both home to a historically important precolonial Igbo state and at the same time the site of one of the largest markets in West Africa prior to the Nigerian Civil War. Thousands of small- and large-scale traders, hucksters as well as honest entrepreneurs, made their living here, and signwriters and mural painters were in constant demand. Middle Art, like Chéri Samba, was a moralist and specialized in cartoon-strip story pictures which emphasized the values of honesty and clean living while graphically depicting the evils that could befall a person if they were not vigilant. Later, after the Civil War (1967–70), his painting developed a visionary aspect, with depictions of heaven and hell and even angels dwelling on the moon and singing to the world through microphones, ‘We are angels of the moon. We are always happy. Your good acting will bring you here to enjoy with us.’

Still other forms of visual art production reflect the intersection of popular urban culture with tourism in the form of souvenirs of all kinds. All of these have close counterparts sold in street fairs and Africa-centred boutiques throughout the African diaspora, from London to Los Angeles. The term ‘Afrokitsch’ was coined to describe some of these artefacts when they appeared in Western markets, though this term, which defines them in relation to a largely foreign clientele, obscures their connection to a vibrant urban African culture where they are purchased by local people to decorate their homes. It is also a reminder of the artificiality of separating some types of ‘popular’ art from ‘tourist’ art. Both are largely urban, both exist in the streets and markets, usually (though not always) outside the gallery-museum circuit, and both are produced as unselfconscious commodities by people who usually think of themselves as artisans (unless they happen to develop an elite audience). While art historians such as Susan Vogel have held out for the exclusion of tourist art from the ranks of authentically ‘popular’ art production because it is not made primarily for a local clientele, anthropologist Karin Barber argues that all such genres are manifestations of popular culture, it is just that some are more commercially motivated than others. In doing so, she locates popular art and culture in an indeterminate, continually negotiable space between traditional and high culture, both of which are largely in the hands of elite patronage.

27 Middle Art (Augustine Okoye), ‘Oh! God Bring Peace to Nigeria’ said Bello in Praying, 1970s

The development of new popular genres in most African countries has initially taken place against a background of local patronage, with occasional outside interventions in the form of the ‘discovery’ of artists by foreign collectors, scholars and curators. Much of it – murals, advertisements, theatrical productions – is not collectible in any case. South Africa is somewhat different in that it alone has a largely local, mainly white and educated, patron/collector base. It also has artificially created ‘homelands’, which became repositories of ‘authentic’ African culture for white city dwellers. It has more galleries, curators and other art-world institutions than any other African state, and a class of vigilant intellectuals who, having long been unwilling participants in the apartheid system, are inclined towards continual self-examination and the search for a ‘real’ South African art. Beginning in 1980, new work, which until then had only been available to visitors to the rural homelands, was brought into the gallery circuit and labelled ‘transitional art’, in the sense of being neither ‘traditional’ (i.e. intended for ritual or domestic use) nor ‘modern’ (i.e. part of high-art notions of uniqueness). A formative moment was the 1985 ‘Tributaries’ exhibition in Johannesburg, curated by Ricky Burnett, which brought the work of Noria Mabasa, Dr Phutuma Seoka, Jackson Hlungwani and several others to the attention of the gallery-going public, decontextualizing and reframing their work not as tourist curiosities or rural souvenirs but as legitimate art. So is ‘transitional’ just another term for what Barber called ‘popular’? Or is it, in critic Colin Richards’ words, a convenient ‘form of invisible mending [in which] rends in the cultural fabric…are magically made good’? The artists’ histories have been important in this framing. Noria Mabasa, a Venda sculptor, first began making clay figures in 1974, drawing on images from local Venda life and from television, such as the highly publicized Siamese twins who were separated in a Soweto hospital. Although her work is commodified (as multiples of the popular clay figures) in much the same way as the flour-sack painters in Kinshasa, she is presented by galleries as a serious artist, usually by focusing on her one-of-a-kind wood sculptures and the fact that they are inspired by dreams. She appears to have two modes of working, one (the clay figures) which she sells in large quantities and which resembles high-end tourist art, and the other which is singular, private and not easily commodifiable.

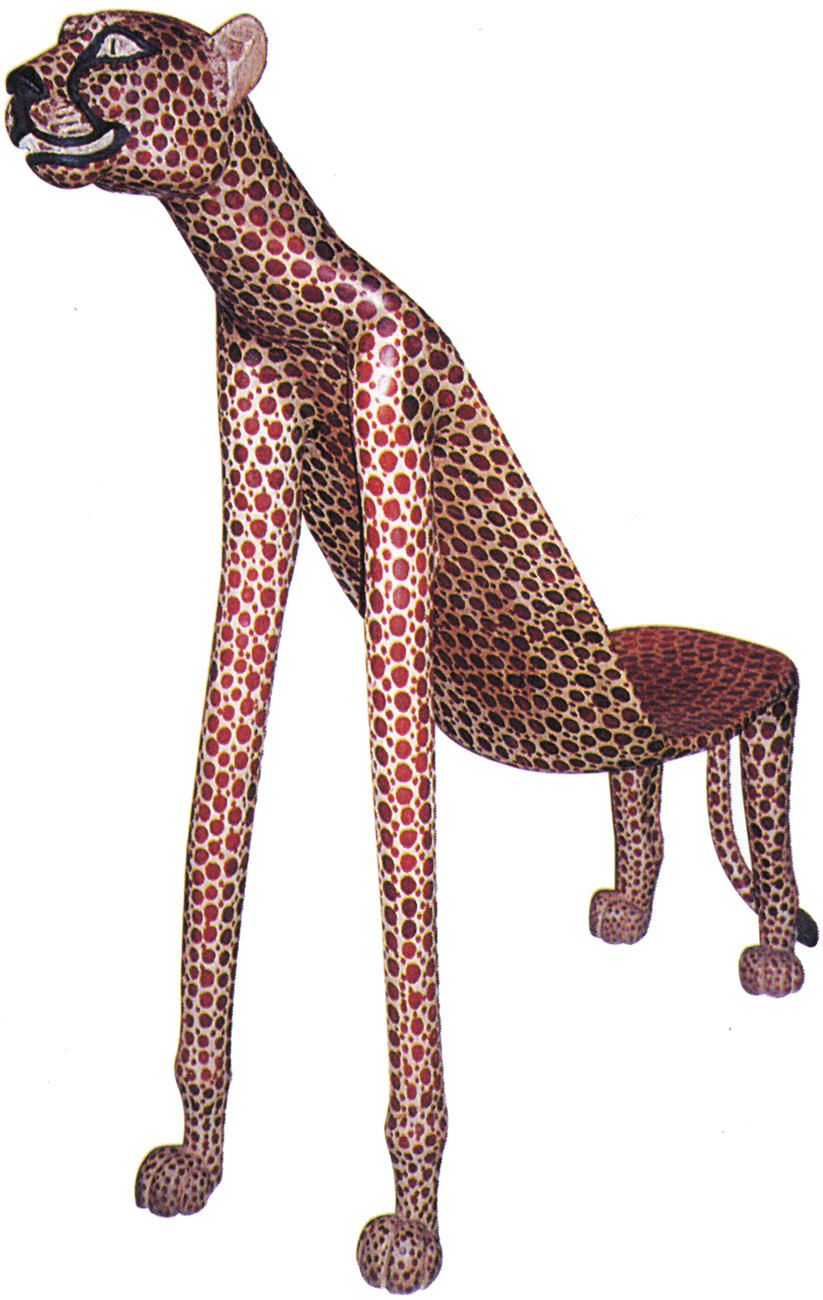

28 Mutunga, Cheetah Chair, 1998

29 Dr Phutuma Seoka, Dog/Leopard, 1989

Dr Phutuma Seoka by contrast is the consummate entrepreneur, a herbalist doctor and maker of patent medicines who started carving objects to sell to tourists back in the 1960s. He draws very freely on the work of other artists, aggrandizing styles and subjects, but is best known for his corkwood animal sculptures, which are both humorous and threatening. Jackson Hlungwani, like Seoka, lives in the northern Transvaal, but represents the other polarity seen in Mabasa’s work – that of the visionary directed by dreams.[29] He is a preacher in the African Zionist Church and has spent the last thirty years building an edifice to God, where he both preaches and sculpts on a monumental scale.[30] Is there something uniquely South African about the work of these artists? Or is it the art audience in South Africa which differs from that of other countries? Animal sculptures very like Phutuma’s are made by a few Kamba carvers in Kenya, and a disabled artists’ workshop makes whimsical pottery figure groups that could rival Mabasa’s, yet they lack the critical apparatus which might reframe them as ‘real art’, so are only seen in the curio markets. Nor are they publicized as the work of named individuals with known histories, another important step in breaking free from the tourist art mould. One can safely assume that there is plenty of ‘transitional art’ outside South Africa, but for the most part it lacks the backing necessary to propel it into gallery circles.

30 Jackson Hlungwani, Throne, 1989

31 Sunday Jack Akpan, Eleven funerary sculptures (two Akwa leaders, two Ibibio leaders, one Efik leader, one Rivers leader, one Anang leader, two leaders in European dress, one officer of the marines, one police officer), 1989

There are other kinds of art that should be considered ‘transitional’ – new genres that are nonetheless based on ideas already socially embedded in local communities. Unlike Mabasa’s or Seoka’s work these other genres were not originally produced for the art market, nor were they the ephemeral products of art populaire. Both the late Kane Kwei (and now his son Samuel Kane Kwei) in Ghana and Sunday Jack Akpan(b. 1940) in Nigeria make funerary art for their own communities. While their pairing has become an art-world cliché since the ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ (1989, Paris) and ‘Africa Explores’ (1991, New York) exhibitions, their work is very different. Monumental shrine and funerary sculpture in clay has an established history in central and southeastern Nigeria and neighbouring parts of Cameroon. When cement became available as a building material it gradually began to replace clay, and while art historians have rightly mourned the loss of spontaneity with the use of cement, local people prefer it for its permanence.

32 Workshop of Samuel Kane Kwei, Teshie, Ghana, 1993. The Mercedes coffin, a workshop favourite, was originally produced by Kane Kwei Sr for the burial of the owner of a taxi company.

Akpan’s innovation lies in his uncanny likenesses which are cast and then overmodelled in wet cement.[31] Kane Kwei’s coffins, on the other hand, do not have the same grounding in tradition. Coffins themselves were only introduced in the colonial period as a part of Christian burial practice, and Kwei’s designs represent ebullient innovation and serve as a monument to his clients’ worldly prestige based on this relatively new form.[32] The first coffins were made for local burials, but their development as an art form must be seen in a wider context; in the early 1970s, they were ‘discovered’ by a California gallery owner. In contrast, the patronage of Akpan’s cement funerary portraits has remained largely local and Nigerian.

As these examples demonstrate, new genres produced for a local clientele need not be crudely fashioned, inexpensive to own or ephemeral. On the contrary, they can also be costly status symbols, available only by commission and, like ‘high art’ categories in the West, an important investment for the owners.

33 CITA (Information and Tourism Centre), photographer unknown, Soba ou Autoridade Tradicional, Benguela, Angola, 1958

34 Seydou Keïta, Untitled portrait of a Woman, Bamako, Mali, 1956–57