112 Contemporary Benin head presented to the American President Jimmy Carter by the Nigerian government in 1997. This is a modern version of the well-known sixteenth-century copper-alloy casting of the Iya Oba, or Queen Mother, of Benin.

Anthropologist Bruce Lincoln argues that one problem with conventional high-art discourse is that it creates a major distinction between ‘the privileged sphere of Art’ and all other goods. As the case of Frank McEwen and Zimbabwe stone sculpture demonstrates, one of the central tenets of this discourse maintained by museums, patrons and collectors is the difference between aesthetic objects made in response to an urge to create and those produced unabashedly to be sold. High or fine art, it is held, must be free of commercial motive because this reduces artworks to the status of household furniture. Historically, there have been two kinds of distinctions entangled in this belief, that between art (supposedly non-utilitarian) and craft (utilitarian) and a second between art (supposedly non-commercial) and commodity (commercial). Neither of these methods of categorization, which derive from European aesthetics and artisanal traditions, are, however, an accurate reflection of African cultural realities.

Before the intervention of European patronage in the nineteenth century, African art outside the major coastal trading networks was, as we have already seen in Chapter 4, typically a local phenomenon. Masks, ritual sculpture and other highly valued objects were similar to what the anthropologist Arjun Appadurai calls ‘enclaved commodities’, circulated mainly through local patronage by traditional elites and members of various religious associations and performance groups. But to assume that no other exchanges ever occurred is to ignore the obvious routes opened up by war, trade and diplomacy, often before the advent of European colonization. It is therefore quite wrong to assume that the movement of art objects only began in the colonial period with the entry of African art into a global market. What is, however, undeniably true is that the global market is different from the local and regional one.

112 Contemporary Benin head presented to the American President Jimmy Carter by the Nigerian government in 1997. This is a modern version of the well-known sixteenth-century copper-alloy casting of the Iya Oba, or Queen Mother, of Benin.

In the twentieth century, war, trade and diplomacy gradually overshadowed a once-dominant local patronage as the means by which African art circulated. In the Nigerian Civil War of 1967–70 an unprecedented number of artworks were smuggled out of Nigeria and onto the world market. In a similar fashion, the channels of diplomacy continue to be conduits for exchange. While the Africa Reparations Movement worked to convince British museums to return the Benin bronzes seized during the 1897 British Punitive Expedition to Nigeria, the Nigerian government was giving away contemporary versions of the same bronzes as official gifts to various heads of state and institutions around the world.[112] But it is trade – the global market – that has absorbed most postcolonial art production. For every piece of sculpture produced by a typical kin-based workshop for a local clientele, several more are made for export. This is not a simple shift in practice but a very complex one, because it engages both the art–craft and art–commodity distinctions made by Western aesthetics.

In reality, every artwork, whatever the original motivation of the maker or its purpose, takes on the status of a commodity once it moves into a system of exchange. But art-world institutions, as the keepers of high culture, must maintain that artworks and commodities are two different kinds of thing. It has also led to the imposition of their own criteria for differentiating genuine artworks from commodities. One well-known African art museum declined to collect sculpture that had been carved with imported knives or chisels, since this apparently indicated a commercial tendency – a principle that would disqualify most Zimbabwe stone sculpture, since modern power tools are used to cut and polish the stone. On the other hand, Kamba sculptors in Kenya, who are organized into large cooperatives to market their work, still use adze handles faced with rhino hide.

In Africa, the issue is further complicated by the fact that the masks, figures and other objects identified as ‘art’ by Western collectors did not occupy this ‘privileged sphere’ in relation to other valued artefacts in the minds of the people who made them. To their African makers and owners, valuable objects were ones that possessed visual power and ritual efficacy. Furthermore, the value attached to both ritual objects and utilitarian ones depended on how successfully they performed their intended function. In that sense a shrine figure and a water pot were both ‘functional’ and therefore valuable.

In Africa, emulation of one artist by another was an integral part of the workshop system and an important part of apprenticeship. Precolonial workshops (as well as individual artists outside the workshop system) turned out an established repertory of forms required by their patrons. The upshot is that African artists who have not been exposed to Western high-art categories do not make the same judgments about either utilitarian and non-utilitarian forms or the continued replication of a known prototype which are crucial to Western assumptions about either art versus craft or artworks versus commodities.

As the social anthropologists Jean and John Comaroff argue, a commodity is ‘not only a product but also the embodiment of an order of meaning and relations.’ In an African workshop or cooperative the ‘order of meaning’ assigned to artisanal practice, and to the relations between producer-artists and consumer-patrons, is often very different from the image of African practice imagined by far-away collectors. Just as precolonial African art production has been idealized as part of the romantic image of a pristine traditional society, postcolonial workshop art has been dismissed by the same collectors as commercial and derivative, and the differences between the two exaggerated.

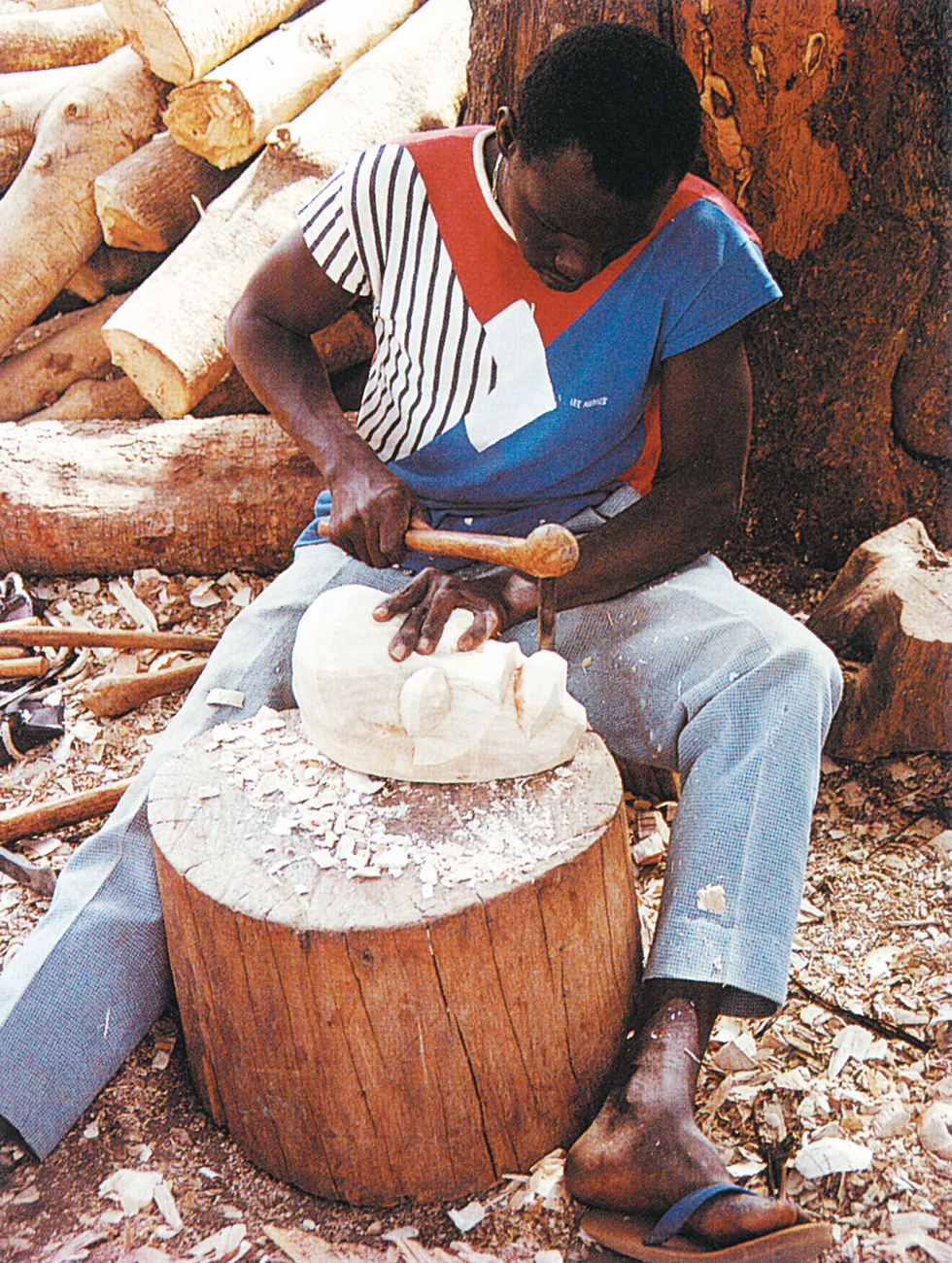

113 A Kulebele artist carving a Dan-Ngere style mask, Korhogo, Côte d’Ivoire, 1988. Photograph by Christopher Steiner. Copying, whether for the export market or local patrons, has generally been seen as a sign of professional competence, and market demand is closely linked with the development of artistic styles.

The greatest difference between African and non-African assumptions about art and commodity can be seen where they are actually produced – in the workshop, the cooperative or the individual workplace. By contrast, it is where they are sold, be it a gallery, kiosk, street corner or illustrated catalogue, that an accommodation is attempted between producer and consumer, African artist and foreign collector. The dealer or trader is charged with bridging this divide and, once again, cultural mediation comes into play. All sellers have a strong interest in making their inventory desirable, which can either be done by appealing to various beliefs held by the buyer – that authentic art must be old, for example – or through the introduction of new ‘stories’ that the buyer may not have heard. This chapter considers the commodity question both at the site of production and as a problem of reception, but these are not easily separable, since one influences the other. The other important starting point is that artistic production of all kinds needs to be viewed through the lens of the culture producing it, and not merely through Western assertions of what constitutes ‘traditional’ art and what are merely goods.

Since the late colonial period there have been three main kinds of artists’ groups which produce for global as well as local markets – old-fashioned kin-based workshops, cooperatives (which may be either outsider-founded or within the community) and experimental, non-traditional workshops (usually supported by external patronage) such as Osogbo, Nigeria (see Chapter 3), Tengenenge, Zimbabwe, or the more recent Triangle-inspired workshops (see Chapter 4). Production varies from souvenirs to versions of established traditional genres, to new media destined for the gallery circuit, but most are organized in ways that reflect local patterns of authority and artisanship. The distinction between workshops and cooperatives is sometimes blurred: some contemporary cooperatives are just overgrown local workshops with someone who keeps written records of financial transactions. But despite their genealogical link, they differ from their smaller and more traditional counterparts in the degree to which they are removed from their clientele and the change in the ‘order of meaning’ that structures their relationship to clients. In a typical cooperative, most transactions are with middle-man traders and distant, foreign consumers, while relatively few involve the artists in an ongoing commitment to supply ritual objects or prestige goods to the community or its leaders.

Nonetheless, some workshops and indigenous cooperatives manage to do both. Yoruba family-run workshops in Nigeria are known for their resilient traditional practices, but as the demand for shrine sculpture and other accoutrements of orisha worship has declined, they have increasingly sought new sources of patronage. In the early 1990s, workshop sculptors from Oyo State in Yorubaland gathered together to form a professional association and rented an exhibition space in Ibadan. The hope was that potential clients would come to see their work and then contact the artists whose names and addresses were attached. This was clearly an attempt to reach beyond the limited local patronage and a pragmatic recognition that art, once it is exhibited for sale, takes on a commodity status, with a changed ‘order of meaning’ between artist and client.

In Korhogo, Côte d’Ivoire, the postcolonial production of Senufo sculpture by Kulebele, a hereditary sub-group of specialist carvers, has evolved similarly into different art-market niches, though much more systematically than in the family-run Yoruba workshops.[113] Although in the past patronage of Kulebele sculptors was dominated by the Senufo men’s society, known as Poro, since the late colonial period Hausa middlemen have succeeded in creating a bridge to the European art market as well as to tourists in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire’s capital. As a result, there is a status hierarchy among carving groups based on different types of patronage, which in turn depends upon the level of carving skill.

When Dolores Richter studied the Kulebele carvers in and near Korhogo from 1973 to 1975 she found three types. First there were the barely competent ‘hack’ carvers and teenagers who would not have been carvers at all had there not been a tourist market. Their masks, which most could produce at the rate of one a day, would be unacceptable to local Poro society patrons as well as to knowledgeable foreign collectors, and were suitable only for sale to the most undiscriminating tourists. At the middle level were carvers who were technically competent, but had a narrow repertory and unremarkable personal style, and produced the bulk of their work for the tourist and overseas market and a few traditional commissions. But the most interesting were the highly accomplished carvers whose work was admired and discussed. They produced the carvings needed in Poro rituals as well as major pieces commissioned by Hausa, Senegalese and French dealers. They were also the tamofo (masters) of the apprenticeship system. Richter has argued that in their case, rather than detracting from the quality of their work, the export art market actually improved it, since it allowed them the opportunity to carve full-time and thus increase their technical skills. In other words, while commodification has lowered the overall quality of Kulebele carving (since there are now many more mediocre carvers than in the past), it has had the opposite effect on the best artists.

The same argument can be made for workshops and cooperatives where there is no traditional patronage at all, such as Kamba carvers in Kenya. The best carvers pay their dues to support the cooperative, but have nothing to do with the production of ordinary curios. Instead, they only work on commission for Nairobi galleries or private clients, producing complex pieces which can take several weeks to complete and sell for high prices. Sculptors who do this kind of work describe it as onerous, since it exists outside the established repertory of the cooperative and requires a good deal of mental as well as physical skill. In contrast, teenagers and the least skilled cooperative members carve trinkets, salad spoons and napkin rings or polish finished carvings, but even though their remuneration is small, it is still much higher than the wage of a common labourer, and the working conditions are much more congenial. There are, however, many carvers in between these two levels of competency.

Despite the fact that two of the three main Nigerian cooperatives are located in the biggest urban centres of Nairobi and Mombasa, recruitment is typically based on kinship ties in Ukambani, the Kamba homeland. Even the very large Kamba cooperative at Changamwe outside Mombasa, which has well over a thousand resident carver-members, is organized into small sheds of fewer than a dozen men.[114] These groups often stay together over many years and essentially replicate the conditions of the family workshop widely found among African cultures with a long wood-carving tradition, from the Yoruba in Nigeria and Benin to the Makonde in Tanzania and Mozambique. It functions as an informal apprenticeship system, with the passing-on of technical skills as well as genre specialization from the senior to the newer members.

What is unusual about the Kamba case is that these highly organized artisanal practices did not exist until the 1960s, although workshops had gradually developed following the First World War. In the nineteenth century, in Kamba culture there were at least two models of highly skilled artisanal practice – the blacksmith and the ivory carver. The Kamba were known as both elephant hunters and ivory traders, out of which both their skill in ivory carving and their entrepreneurial awareness developed. Prior to the large-scale importation of beads through trade late in the nineteenth century, Kamba blacksmiths produced fine chains and other metal adornments, which they exchanged in the Central Highlands and Rift Valley of what is now Kenya. Even during the Mau Mau revolt in Kenya in the early 1950s, Kamba who were held by the colonial government in detention camps spent their free time carving.

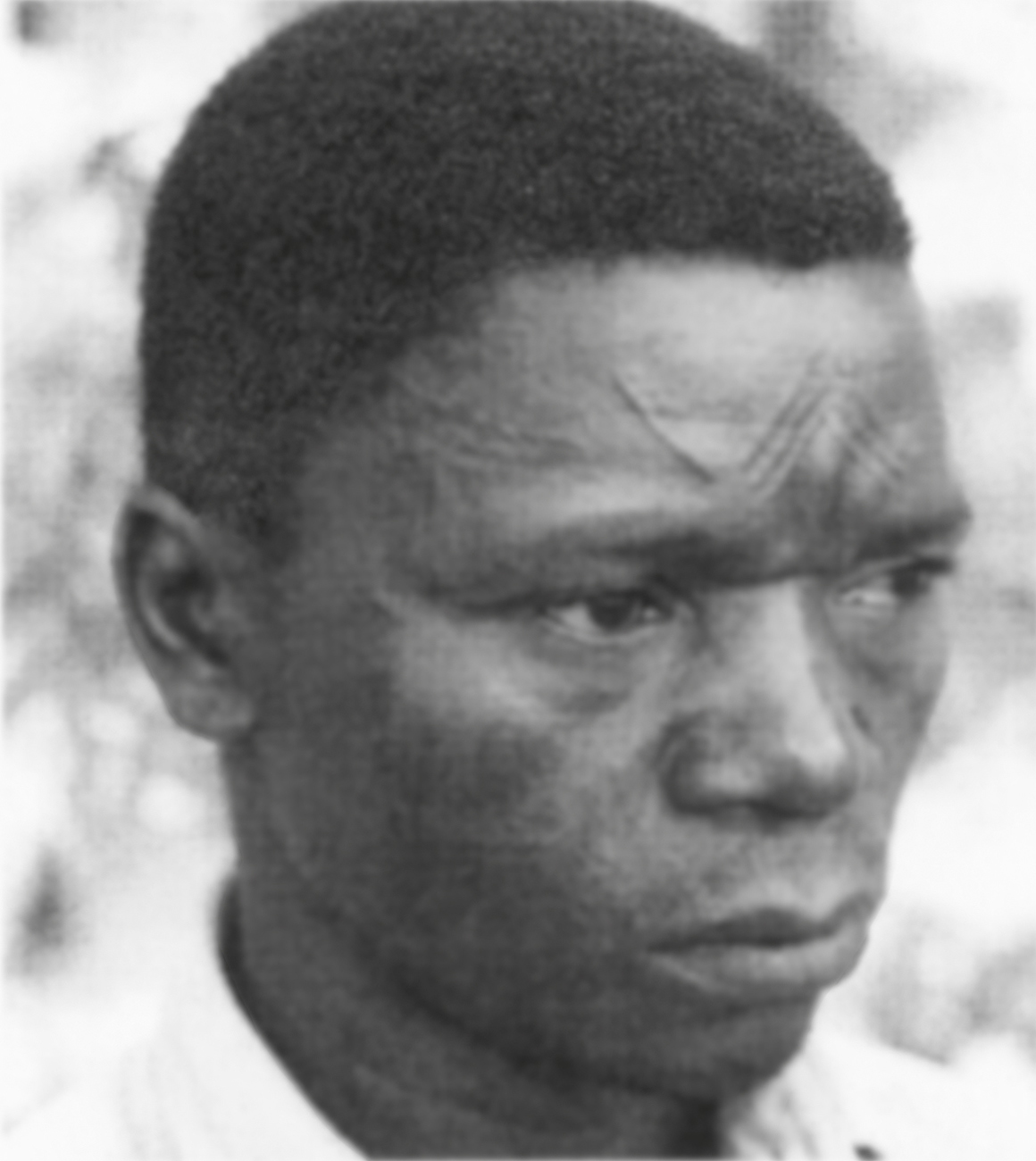

In contrast to Kamba artists in Kenya, who mainly produce highly naturalistic animal sculpture, the Makonde (also Makonde) sculptors of Mozambique and Tanzania raise awkward questions for Western museums regarding the entangled issue of commodification. Because Kamba work is marketed through cooperatives and is straightforwardly geared towards the curio market in Kenya and abroad, it sits mainly on the commercial side of the art–commodity divide in Western classification. But Makonde sculpture has a long history, with precolonial examples in many ethnology collections which predate its entry into the export market. It is produced by sculptors in small family groups, who regard themselves as having a deep cultural connection to their work regardless of its intended audience. Since the 1930s, they have been economic and political migrants moving from northern Mozambique to Tanzania, but most have resisted commercial opportunities to produce curios according to specifications from patrons in the manner of Kamba carvers in Kenya or neighbouring Zaramo in Tanzania. They also held fast to Makonde marks of identity, continuing to file their teeth, wear the upper-lip plug and display elaborate facial scarifications long after these customs had disappeared regionally. Regardless of this apparent cultural conservatism, their contemporary sculpture is dominated by forms that are radical departures from their precolonial art. This new genre and style, called nnandenga in the Kimakonde language, but better known by the Kiswahili terms jini (from the Arabic djinn) or shetani (satan), began to appear in Tanzania in 1959, beginning with the work of Samaki Likonkoa.[115] Unlike the angular realism that had characterized much precolonial Makonde figure sculpture and the earliest figures produced for Portuguese colonial administrators, the new sculpture was sinuous, anti-naturalistic and frequently employed erotic and social caricature.

114 Kamba carvers at the Changamwe cooperative near Mombasa, Kenya, 1991

115 Maconde sculptor Samaki Likankoa, Dar es Salaam, 1970

116 Maconde mapiko mask for initiation ceremonies. Likankoa has markedly similar facial tattoos – here added using beeswax.

Although seemingly a new sculpture genre and certainly a new style, the iconography of nnandenga was drawn directly from Makonde oral traditions concerning nature spirits and from a masquerade of the same name performed on the Makonde Plateau in Mozambique. Yet, despite traders’ claims to the contrary, no Makonde person would purchase or use such a figure: they were made explicitly for non-Makonde patrons and therefore intended as art-market commodities. Even so, the Makonde played little or no entrepreneurial role in their sale – there were no Makonde traders hawking carvings to tourists on street corners or beaches. Their marketing success was made possible through the promotions of Mohamed Peera, a knowledgeable curio and gemstone dealer in Dar es Salaam who, like Tom Blomefield in Rhodesia a few years later, encouraged carvers to find their own direction.

The Makonde have bifurcated their art production – unlike the West Africans (e.g. Yoruba and Senufo), whose precolonial mask and figure genres have been introduced as commodities into wider circles of exchange, or the Kamba, who did not make ritual sculpture and whose work is therefore for non-traditional patrons.[116] Makonde mapiko initiation masks continue to be made and used by Makonde themselves, while the new genres – the bulk of their production – are made by the same group of artists for a completely different audience. This has caused a good deal of ambivalence in Western art circles, since Makonde sculpture does not fit easily into either an ‘art’ or a ‘commodity’ designation.[117] Some European museums, especially in Germany and France, have admitted contemporary Makonde sculpture to ‘the privileged sphere of art’. A Makonde sculptor, John Fundi, was included in the high-profile ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ exhibition in 1989 in Paris, but in the equally important ‘Africa Explores’ show in 1991 in New York, Makonde art was effectively divided into two irreconcilable entities – initiation masks from Western collections were featured as fine examples of ‘traditional’ art while contemporary Makonde genres were omitted from the exhibition and only mentioned dismissively in the catalogue as ‘fantastical[ly] misshapen…ersatz style[s]’ which ‘respond to the Western buyer’s admiration of uniqueness and authorship.’ In this kind of summary judgment, Makonde sculpture is not treated as the work of individual artists, some of whom are master sculptors worthy of our attention and others more mediocre followers and imitators, but is rejected categorically because it is made for non-Makonde patrons. It is also wrongly assumed to have no connection with the culture from which it springs. Its commodity status casts it into a limbo from which it is difficult to escape.

To overcome this problem, enterprising dealers frequently try to authenticate Makonde sculpture by creating narratives around each piece, which are sold as texts along with the sculpture. One Nairobi gallery owner believed that the hidden meaning of Makonde sculpture was revealed by allowing it to cast its own shadows, and therefore exhibited his sculptures using special lighting. The same dealer employed local Kenyan artisans to put a high polish on the ebony (African blackwood), which Makonde artists leave in its natural state. In myriad ways Makonde art has been subjected to continual reinvention by both its supporters and its detractors.

117 Maconde sculpture in the National Arts of Tanzania Gallery, Dar es Salaam, 1971

There are cooperatives of weavers, dyers and calabash or basket makers, but what is most relevant here are those cooperatives that produce artefacts that can cross the boundaries separating ‘craft’ from ‘art’ in terms of their reception by a Western audience. Roughly speaking, these are artefacts that qualify as representations – sculpture and pictorial media. In their facture, replication from one form to another is inexact and variation a natural occurrence. In addition, the artist’s hand is more visible in the end product than in, say, weaving (though it is visible there also, to an experienced eye). For these reasons, sculpture and pictorial representations have greater potential to be seen as art by a Western audience that views uniqueness as the sine qua non for an object to transcend craft status. Cooperatives, with their very egalitarian nature and their emphasis on production, seem to work against this goal.

Two of the previous examples (Kulebele and Makonde) have involved a partnership between kin-based carving workshops and local traders or dealers who market their work beyond the region. The Kamba cooperatives are organized specifically to produce and market their own carvings and earn income for their members, so are more independent and entrepreneurial than the family workshops. Cooperatives of a different kind were set up with the assistance of outsiders, usually as a community development project. International aid organizations and volunteer services have made such cooperatives part of their income-generating strategies for both rural people and urban migrants and many of these focus on recruiting women artists.

The severe financial constraints under which so many unschooled artists must work is made even more complicated by the social position of most women as men’s dependents, even if they are financially self-supporting through their own labour. They are often not free to attend workshops or join cooperatives without the consent of a male family head. And even with such permission, if a woman does not have her own source of income she may be unable to join because she is not able to pay the modest fees for materials or membership dues. Yet some women do persevere against these odds and become artists by joining training centres.

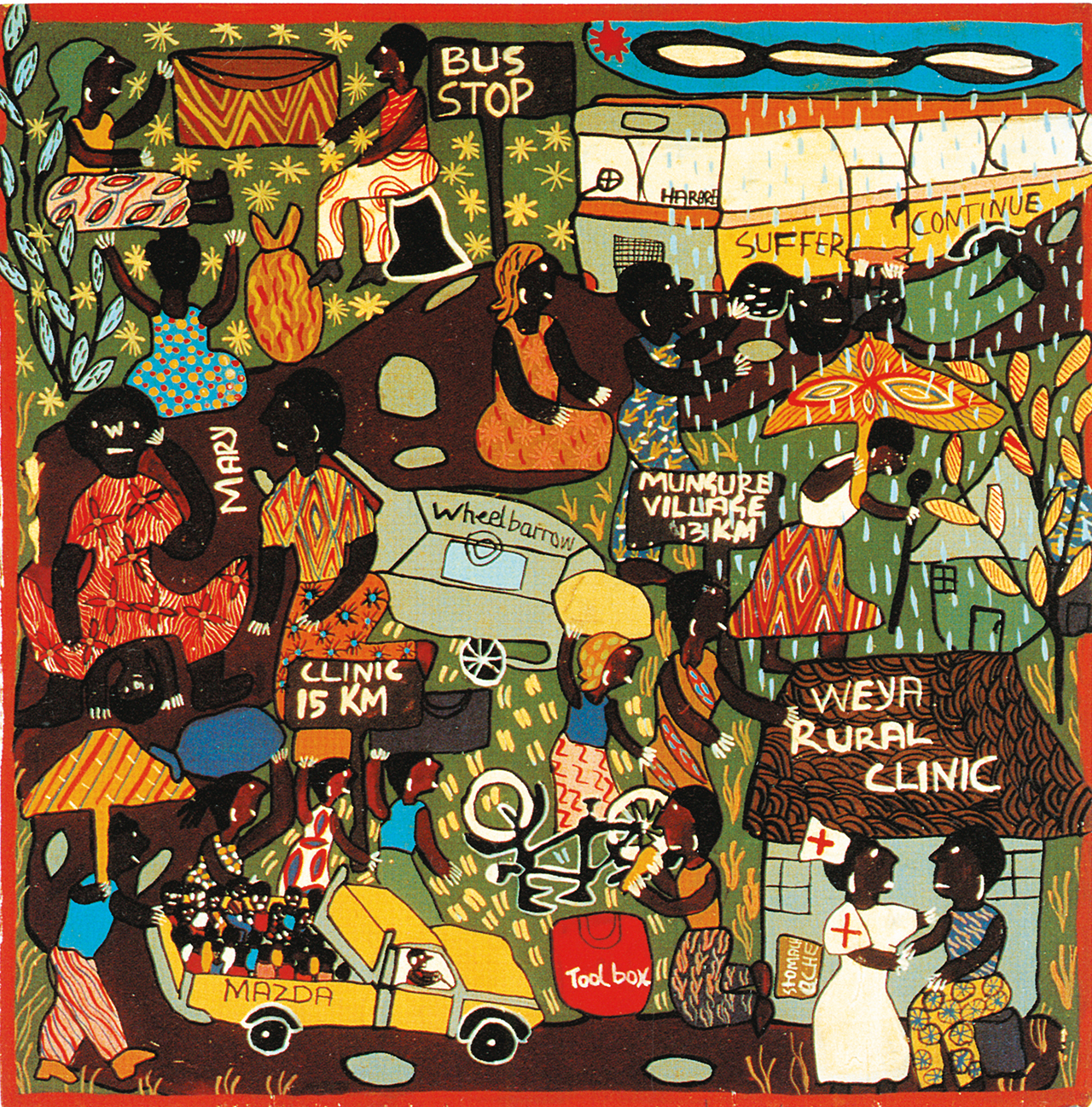

Cloth is easily commodified (in the past it was even used as a currency), and usually remains on the craft side of the art–craft distinction found in Western aesthetics. But it is also capable of being used as a one-of-a-kind pictorial or narrative medium, and can thus acquire the distinction of being ‘art’ according to the criteria used by museums and collectors. One of the best-documented examples of this was a project started by a German art teacher, Ilse Noy, who went to Zimbabwe in 1984 with the German Volunteer Service to work in a weaving cooperative. Between 1987 and 1991 she worked at Weya, a Shona-speaking communal area (former ‘native reserve’), 170 km northeast of Harare, where she and Agnes Shapeta, a local dressmaking instructor at the Weya Community Training Centre, taught women to make narrative compositions using various techniques; to be storytellers and ‘artists’, as well as seamstresses. The problems they encountered were formidable. An earlier dressmaking project had failed because women could not afford the necessary investment in a sewing machine, the cost of cloth alone was frequently as much as a factory-produced dress and, in any case, their rural neighbours were too poor to buy the dresses they had made.

In retrospect, Weya turned into an art workshop once it had been decided in 1987 that the machine-sewing courses should be dropped and replaced with hand-sewing techniques, which did not require any expensive equipment. Ilse Noy had originally wanted to develop a training course based on traditional pottery or basketry techniques, but women in the Weya area did not produce either. The crafts they knew, which reflected the European-derived artisanal skills women were encouraged to learn under the former colonial state of Southern Rhodesia, were knitting and crocheting. Noy realized that however skilful these goods might be, they did not look ‘African’ to an expatriate or foreign buyer and therefore had no chance of being marketed outside the local community. What happened next is paradigmatic of a workshop situation led by a cultural outsider – the introduction of a borrowed idea from outside the repertory of knowledge available to the local participants. In this case it was African, but from a different part of the continent altogether – Noy read about the appliquéd textile compositions produced by Fon artists in Abomey in the far-off Republic of Benin.[118] She reasoned that the hand-sewing skills of Weya women could be applied to the appliqué technique, which could be produced as wall hangings in the form of pictorial compositions.

118 Fon appliqué cotton textile, Republic of Benin, 1982

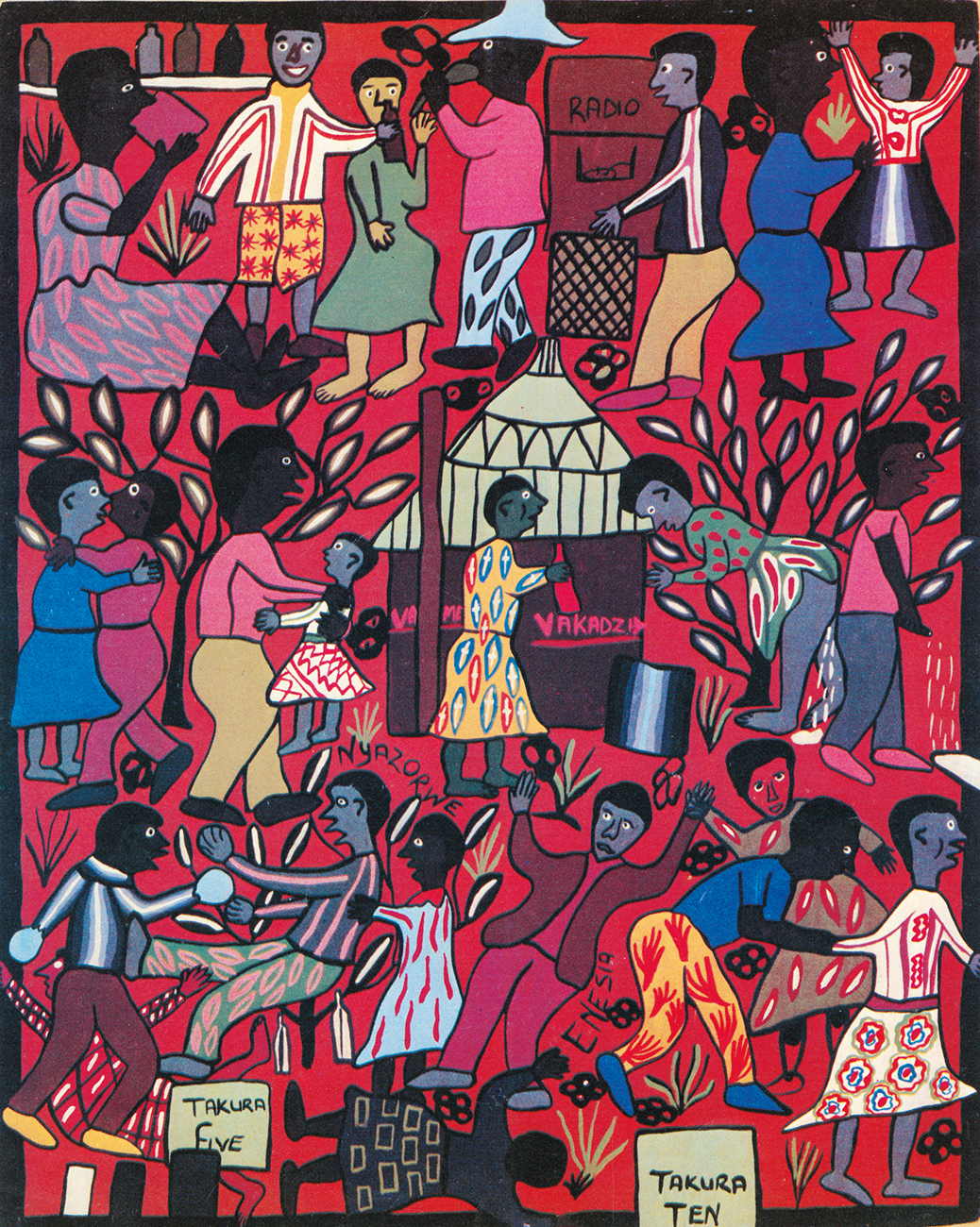

At first the women who had come to learn practical hand-sewing resisted the new genre. Many dropped out and those who stayed were sceptical, some because of its strangeness and others because they found it hard to believe that anyone would buy the wall hangings. The women had no previous experience of visual representation, and had to teach themselves how to shape figures and arrange them in meaningful compositions. But perhaps because it was clear from the start that the buyers for these works were not going to be local people, the women adopted a social documentary approach – depicting not only domestic village scenes of people and animals, but also of sex, prostitution, witchcraft, drunkenness and anything else around which a pictorial narrative could be constructed.[119] Many of the subjects are openly transgressive – topics women would never speak about in public or in the presence of men. Here the role of the workshop coordinator obviously came into play: the women were not admonished to stay within accepted social codes for female behaviour, which would have precluded their representation of taboo subjects such as male and female nudity or people urinating, so with the workshop’s encouragement they came to focus on stories that reflected some of their most powerful personal experiences.

In the Weya work there is less compositional sophistication and less realistic modelling of figures than in the work of untrained urban artists such as the Kinshasa painters. This is partly due to the technical limitations of cloth appliqué and partly due to the infrequent exposure of rural women to the variety of pictorial icons – in magazines, newspaper supplements, billboards – which are ubiquitous in the city. This means that Weya art conforms closely to Western notions of ‘folk art’, a category that the urban flour-sack paintings resist. Another difference is that the appliqué technique does not lend itself to the use of text and so as a result the story itself is not inscribed into the picture. To explain the often very complex narratives to customers, the texts may be written down separately on a piece of school notebook paper and sold with the picture. In Noy’s book on Weya, the texts are as important as the compositions themselves.

The themes in Weya art are as wide-ranging as those of urban popular paintings in Congo (formerly Zaire), but the major difference is that these artists are seeing the world through their experience as rural Zimbabwean women.[120] Nerissa Mugadza depicts the problems of the unmarried woman, who is not only marginalized socially, but is also a source of danger to her family:

If the person is not married (and has no child), maybe there is something else in this family causing her to be unmarried. When she dies maybe she will wake up as a ngozi (spirit), saying ‘Why did you not sort out your problem, leaving me to die like that?’

In the top left of Mugadza's picture a woman is carrying poles to build her house and in the next panel she is using grass to thatch it herself. Below, and presumably later, she is lying dead and others are sitting with her corpse. In the last panel she is carried to her grave to be buried with an empty maize cob because she is childless.

The stories range from prosaic descriptions of daily life to melodramas of good and evil. One source of conflict for these women is the love triangle – husband, wife and girlfriend (or husband, older wife and new wife).[121] In Mary Chitiyo’s sadza (maize-starch resist) painting, Kuoma Rupandi and Committing Suicide (c. 1989–92) eight narrative panels are read from left to right and top to bottom in a morality tale of greed, faithlessness, healing, retribution and death. In the first panel, husband and wife are cultivating the fields, and in the second he transports the maize to the Grain Marketing Board by ox cart. The third panel shows him giving some of the grain cash to his girlfriend and receiving mupfuhwira (powerful medicine used to make or destroy a love relationship) from her. In the fourth panel the wife, the dog and the cat have been stricken and paralysed by the mupfuhwira, which the husband put in the stew. The fifth panel shows the wife being cured by a n’anga (diviner) and then in the sixth she is learning to use a sewing machine so that she can become a dressmaker, while her estranged husband and his girlfriend, both now barefoot and without money, pass by. In the seventh panel the contrite husband returns home, only to be spurned by his wife and even the family dog. In the final panel, distraught, he hangs himself from a tree.

119 Enesia, Drinking Beer, 1989. In the words of the artist (top to bottom, left to right), ‘People are drinking beer…old men are in love with little girls because the old men are drunk. They are urinating outside the toilet. Now the men are fighting for a girlfriend. They are going home and some are falling down.’

120 Nerissa Mugadza, Life of an Unmarried Woman Who Has No Child, c. 1987

121 Mary Chitiyo, Kuoma Rupandi and Committing Suicide, c. 1989–92

The punishment of greed and moral weakness in these pictures is a theme common to such diverse artistic expressions as Weya art from Zimbabwe, Mami Wata and other paintings from Congo and the Yoruba travelling theatre performances of the 1970s (see Chapter 1). In all three cases the punishment is accomplished by superhuman intervention – for the Yoruba, it was the orisha (the gods) who appeared in the finale of the play to seal the fate of wrongdoers; in Congo, the Christian gospel; and in Weya art it is the n’anga.[16] But while the artist Chéri Samba depicts himself making a moral choice between good and evil, Chitiyo illustrates the inevitable outcome of moral weakness that causes so many men to make the wrong choice.

The earliest efforts were in cloth appliqué, but after its establishment as a viable art form, gradually Noy introduced other techniques into the training centre – painting on board, sadza painting, drawing and pictorial embroidery. Embroidery proved impractical because it was so labour intensive that artists could not realize a fair reward for their work. Painting, although totally foreign to all the participants, became popular very quickly because it was easy to execute, and although they did not employ the use of parallel text like the Congolese (Zairean) painters, the Weya women were able to introduce signage into the compositions. The painting group, once established, initially produced monotonously similar pictures of village life, which did not sell well in Harare – for one thing, they contained much empty compositional space, which the women filled in with dots and lines, not knowing what to do with the background. To inspire them to produce denser compositions, Noy showed them reproductions of paintings by Valente Malangatana (1936–2011), the well-known Mozambican painter.[122] They began to work in a new, richer compositional style, which they dubbed ‘Malangatana’. As with the Abomey appliqué cloths, it was Noy’s intervention that provided the women with an outside model, one that was unquestionably African, but far removed from the women's visual experience. The models were not chosen for either their historical or their ideological affinity with Weya art – they were chosen to demonstrate what ‘works’ in artistic terms.

Not all successful paintings were crowded ‘Malangatana’ compositions – some employed areas of empty picture space, but minimized these by including several focal points of action. In Problems of Transport (c. 1989) an exuberant artist called Mary comments wryly on one of the difficulties that lies at the heart of rural life, and in doing so rivals the work of Moké, a Congolese urban artist.[124] Moké’s rendition of an ‘express taxi populaire’ shows a mastery of anatomy, modelling in light and shade and certain aspects of linear perspective, while Mary’s figures are like appliqué cutouts, the perspective is vertical, and only the large bus, ‘Suffer Continue’, appears to be rendered in space.[125] But the narrative, read from top left to bottom right, is as revealing of the African condition as Moké’s – people wait for a bus, it breaks down, leaving one man to hire a wheelbarrow to transport his pregnant wife to the rural clinic many kilometres away, while some of the other passengers trudge back to their village in the rain and others crowd into the back of a Mazda pickup truck.

122 Valente Malangatana, The Last Judgment, 1961. Malangatana, who rose to fame in the 1960s, infuses his work with an apocalyptic, energized point of view that is not reserved for his religious and moral subjects, but extended even to visits to the dentist.

123 Filis, Village Life, c. 1987

While most of the compositions by Weya women deal with the dramas of domestic problems and rural life, many of the Weya artists experienced the Chimurenga, or war of liberation, against the white minority government of Ian Smith and the social disintegration which accompanied it.[126] But there were dangers associated with depicting politics as art, here as well as elsewhere. Certain topics emerged as off-limits – not within the workshop, but at the point where they were marketed in Harare. During the guerrilla war, accusations of selling out to the enemy, or of witchcraft directed against the struggle, were common and were punished summarily by freedom fighters (‘comrades’). Narratives other than the official version of the war of liberation were not accepted for exhibition in galleries or for sale in marketing outlets. Weya was an area of heavy fighting, but for the most part the women had to keep these stories out of their art.

124 Mary, Problems of Transport, c. 1989

The Weya workshops between 1987 and 1991 resembled many earlier workshops throughout the continent in at least four ways – they recruited individuals with little or no formal art training; they were founded and coordinated by a cultural outsider; their pedagogy focused on instruction in the basic techniques of non-traditional genres; and the workshop products were not intended for local audiences, but were aimed at an elite market in an urban capital or abroad. However, they were different in two important ways – the artists were women and, unlike most workshops, Weya has been a long-term phenomenon, a community training centre whose set-up more closely resembles a cooperative.

All of these realities have contributed to the commodification of Weya art – in the 1990s, it appeared on hand-painted one-of-a-kind coffee mugs in Starbucks coffee shops in the United States. The conditions of cultural production deeply affect the way artists think about their work. The Weya women worry about what will sell in Harare, because they use this income to lift themselves out of poverty – to pay for food, clothing and their children’s school fees. This uncertainty and lack of individual recognition heightens anxieties about success and failure. Although some of the Weya artists earn as much as secondary school teachers, they have no guaranteed income. This unpredictability, as well as their lack of educational qualifications, causes them to associate art-making with conditions of uncertainty and poverty, and to hope that their own daughters will attend secondary school and become nurses or teachers rather than artists.

125 Moké, Street Scene, 1990

These psychological constraints also have a great deal to do with how artists view the creative process. It is difficult to prize originality when driven by the need to sell, and similarly hard to imagine the artist as a lone creator when involved in group production. Furthermore, success and failure are often linked in people’s minds not only with diligence and hard work, but also with some form of superhuman intervention on the artist’s behalf. Many studies assert that success in contemporary African terms is usually thought of as a ‘zero-sum game’. Every win must be offset by someone else’s loss, which can trigger jealousy and witchcraft accusations.

In small, kin-based groups such as the immigrant Makonde carvers in Tanzania or the old-style Yoruba carving workshops in Nigeria, mutual ties of obligation are very strong. Personal animosities, when they arise, have to be contained. But in groups such as the Weya, where artisanal workshops are not part of the community’s experience and people may be working together for the first time, there are jealousies and anxieties both within and without. The women’s earnings set them apart from other members of the rural community, who have little or no access to money. Unmarried women artists become particular targets of village criticism – one young Weya artist told Noy that, ‘If we live here some of the people can kill me because I am earning more money and I am so young….The n’anga gives me the medicine to protect my body.’ In 1990, the two painting groups that were dominated by young unmarried women decided to leave Weya and to work together in Harare, far from family obligations and village conflicts. These kinds of fissions and fusions are common in workshops and cooperatives and serve as a reminder that with or without commodification, all workshop artists work in complex creative environments that deeply affect what they produce.

126 Abishell Risinamhodzi, Chimurenga, c. 1989. Freedom fighters shoot down parachutes and planes and attack a truckful of Rhodesian soldiers in this idealized vision of the war of liberation. Soldiers march across the top, while at the bottom the first free election takes place.