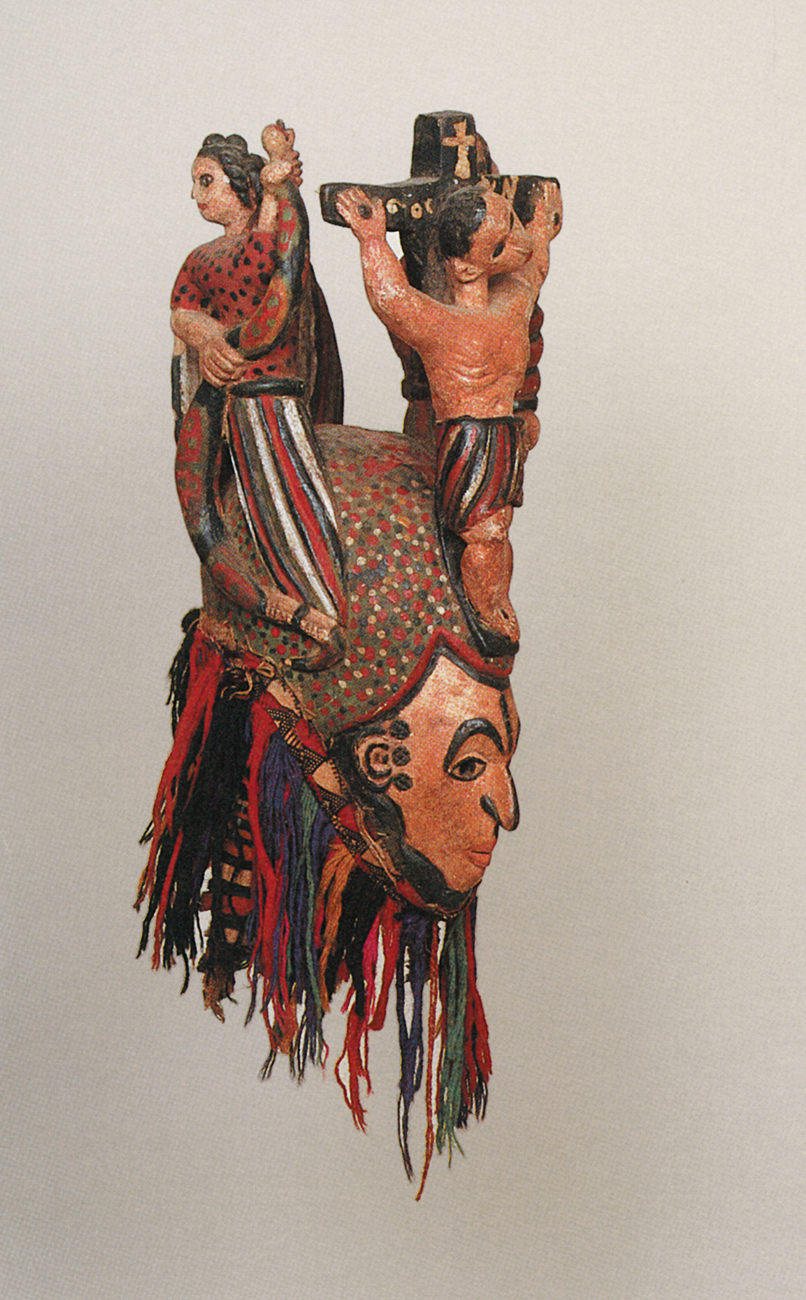

78 Igbo face mask (colonial period, depicting Jesus's crucifixion along with Mami Wata)

The most striking differences between pre- and postcolonial African arts are a result of both the different audiences for whom they are made, and the greatly expanded geography in which first colonial, and now postcolonial, art circulates and ultimately resides. Precolonial (and more specifically, premercantile) patronage was enmeshed in the same expressive culture as the artist, or at most a neighbouring one, but since 1900, if not before (and in the mercantile centres along the African coasts, centuries earlier), both old and new forms have increasingly been produced for patrons and audiences far removed from the originating culture. This shift has happened because of the major political ruptures of the last two centuries, and the widespread introduction of urbanization, schooling and literacy, the cash economy and links to the colonial metropole that have followed in their wake.

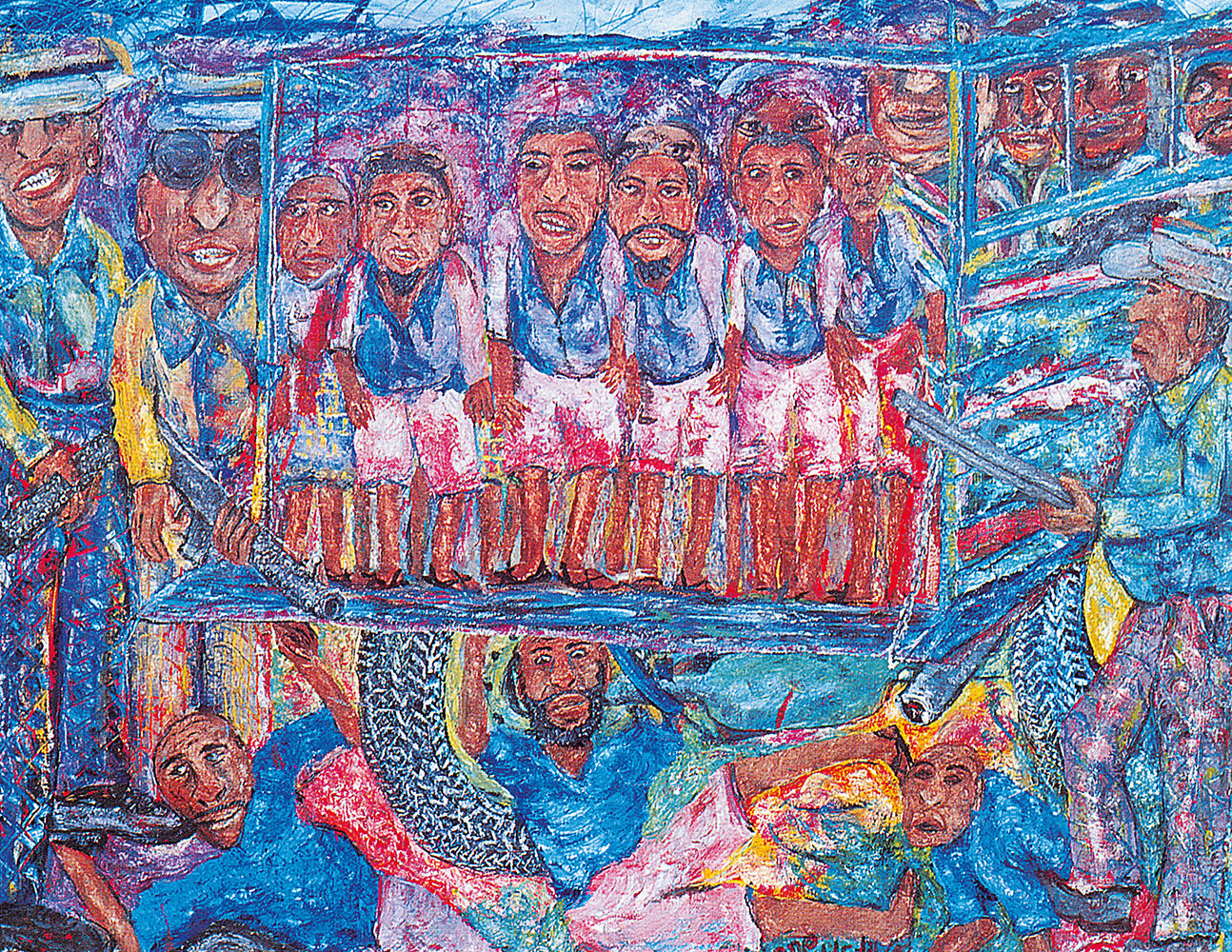

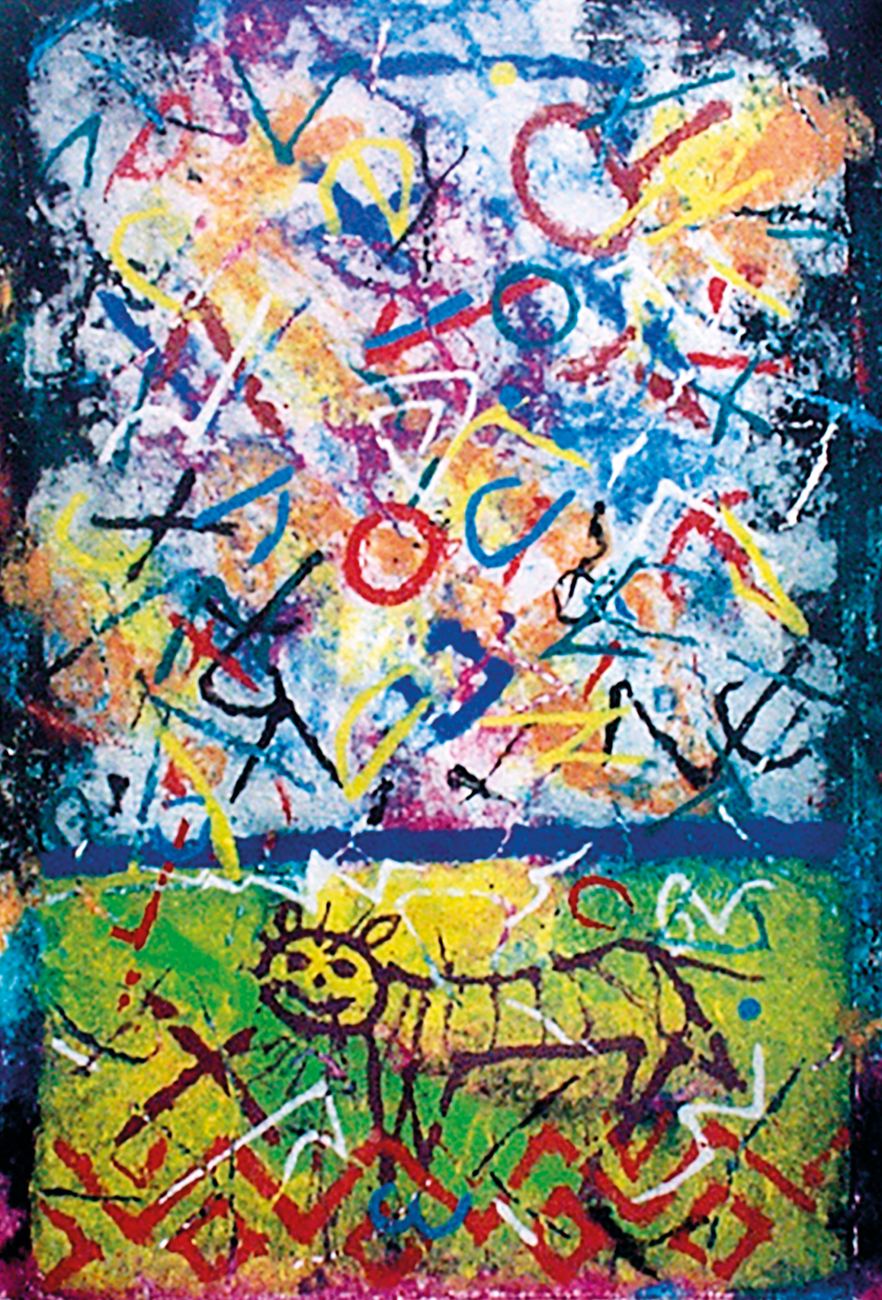

Just as these changes have produced new artists, genres and patrons throughout the continent, successful Christian and Muslim proselytizing and the advent of the modern state have in equal measure undercut the old art forms and patronage system. Some genres simply disappear once the old patronage fades away (such as women’s masks in the Senegambia region), while others incorporate new meanings which allow them to continue to exist in a situation of shifting patronage. Thus there are colonial-period masks depicting Jesus along with Mami Wata, or chiefs’ stools in the shape of early motor vehicles.[78] Undoubtedly, the patrons who commissioned these pieces were in different ways trying to come to terms with the changing meaning of power and authority. But once such objects are no longer in their intended context, they become open to various interpretations. What was seen as an aggrandizing of powerful symbols of modernity to an African artist and audience is frequently reframed by the Western spectator as parody, or quaint naiveté. In such a situation, meanings are no longer fixed and the role of the go-between or broker is called into play to frame and explain them for the new audience. Whether the go-between is an itinerant trader on a motorbike, a wealthy European collector or a museum educator, meaning that was once local and predictable is now distant and constantly renegotiable.

These altered realities have sociological, economic and political, as well as aesthetic, dimensions. The frequent lack of a viable indigenous art market and the resulting constant flow of ‘cultural capital’ to foreign patrons are not only part of a deeply seated postcolonial economic dependency, but more crucially, have shaped the work produced. Lega carvers from eastern Congo working in Uganda know that expatriates prefer either miniature figurines of ivory (or, nowadays, bone) or elaborate hardwood chests and chairs with animal figures carved in relief.[79] The former are part of the traditional Lega repertory, but the latter are strictly a colonially derived export genre.[80] If Gallery Watatu in Nairobi encouraged Jak Katarikawe (1938–2018) to make more ‘naive’ paintings of people and animals kissing rather than something more experimental, he was likely to do so.[81] The expatriates and galleries engage in acts of important cultural brokerage, determining what will be made and how it will be interpreted by potential buyers – in one case as ‘souvenirs of Africa’, and in the other as ‘authentically naive’ painting. To illustrate this more fully several case studies in which patronage has also acted as cultural mediation between artists, their production and their audience, or in the case of the Triangle workshop model, among artists of different backgrounds, are described in this chapter.

A ‘patron’ can be anyone from a favourite saint to a regular customer, or, according to one dictionary, anyone who ‘countenances, protects or gives influential support’. Brokerage or mediation, on the other hand, implies a specific kind of agency: one who actively intervenes as a go-between, in this context between artist and public, or artist and institutionalized art world. All patrons are not brokers, nor are all brokers patrons. Clearly some of the most famous patrons in art history have been content to add lustre to their names as protectors and supporters of artists, while others have been more actively engaged as brokers in the promotion and even sale of particular artists’ work. The emergence of new African art onto the world stage, beginning in the 1950s and 1960s, seems in retrospect to have been a major act of cultural brokerage by a small number of mainly European supporters. Some have been charismatic or merely driven, others paternalistic or romantic. In several instances, it has been African intellectuals rather than white foreigners who have created the conditions for this new art to flourish, and in the case of Osogbo (see Chapter 3) it was both. In these cases, a different set of premises was at work, connected to an emergent cultural nationalism.

78 Igbo face mask (colonial period, depicting Jesus's crucifixion along with Mami Wata)

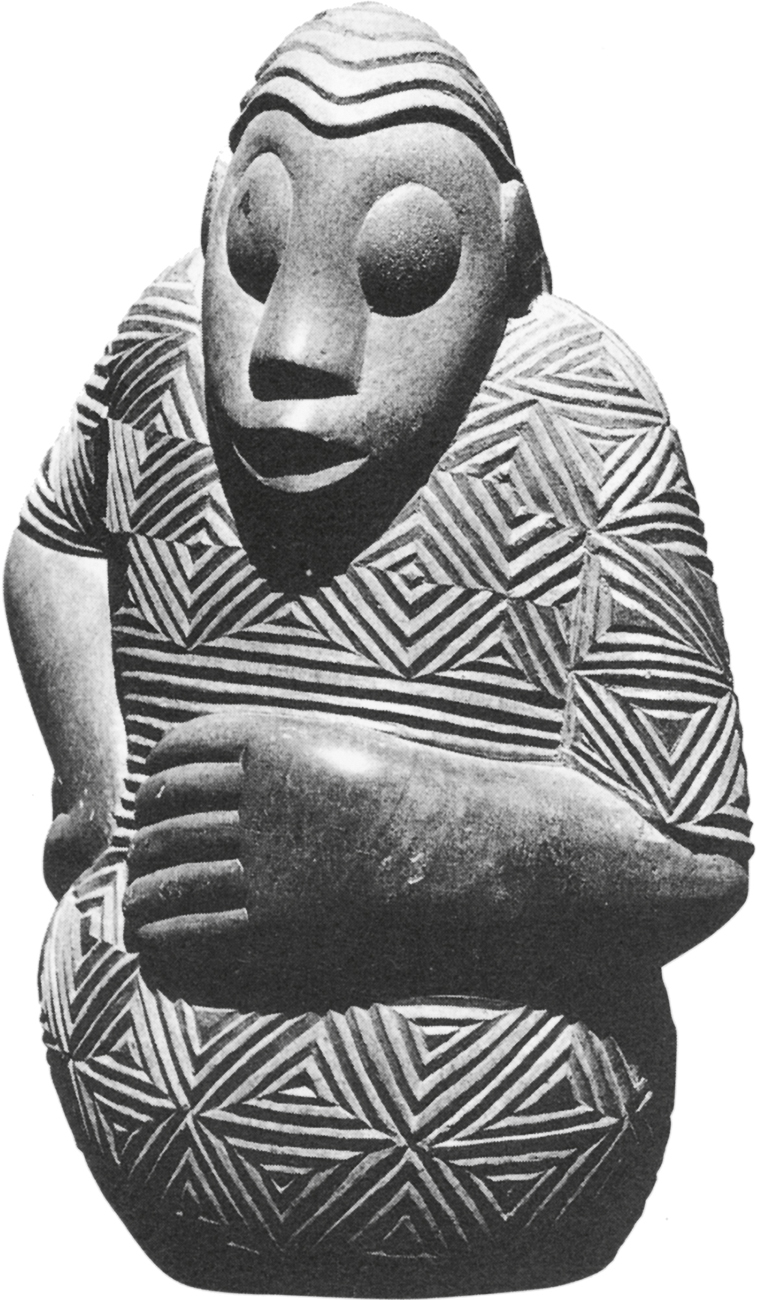

79 A Lega artist from eastern Congo, carving an ivory or bone figure once used in Bwami initiation and, since the 1980s, produced for export.

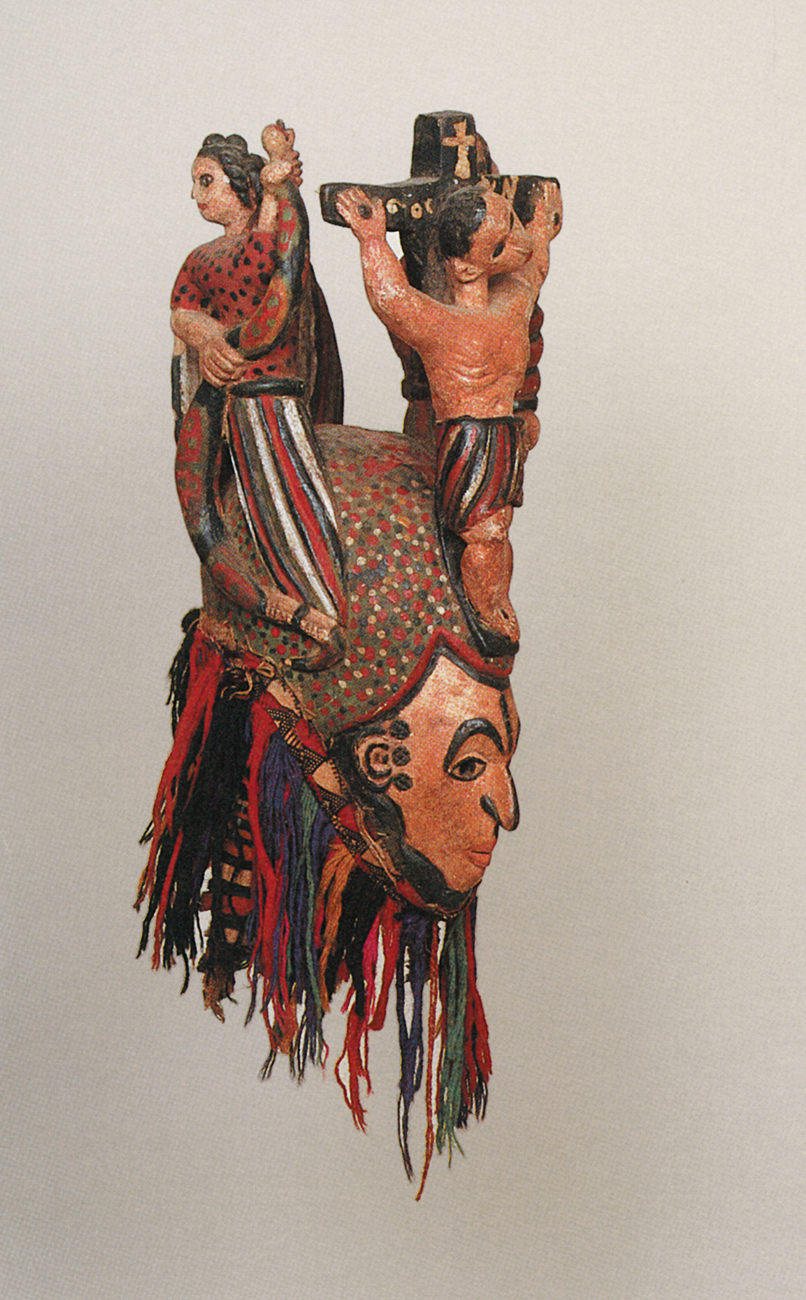

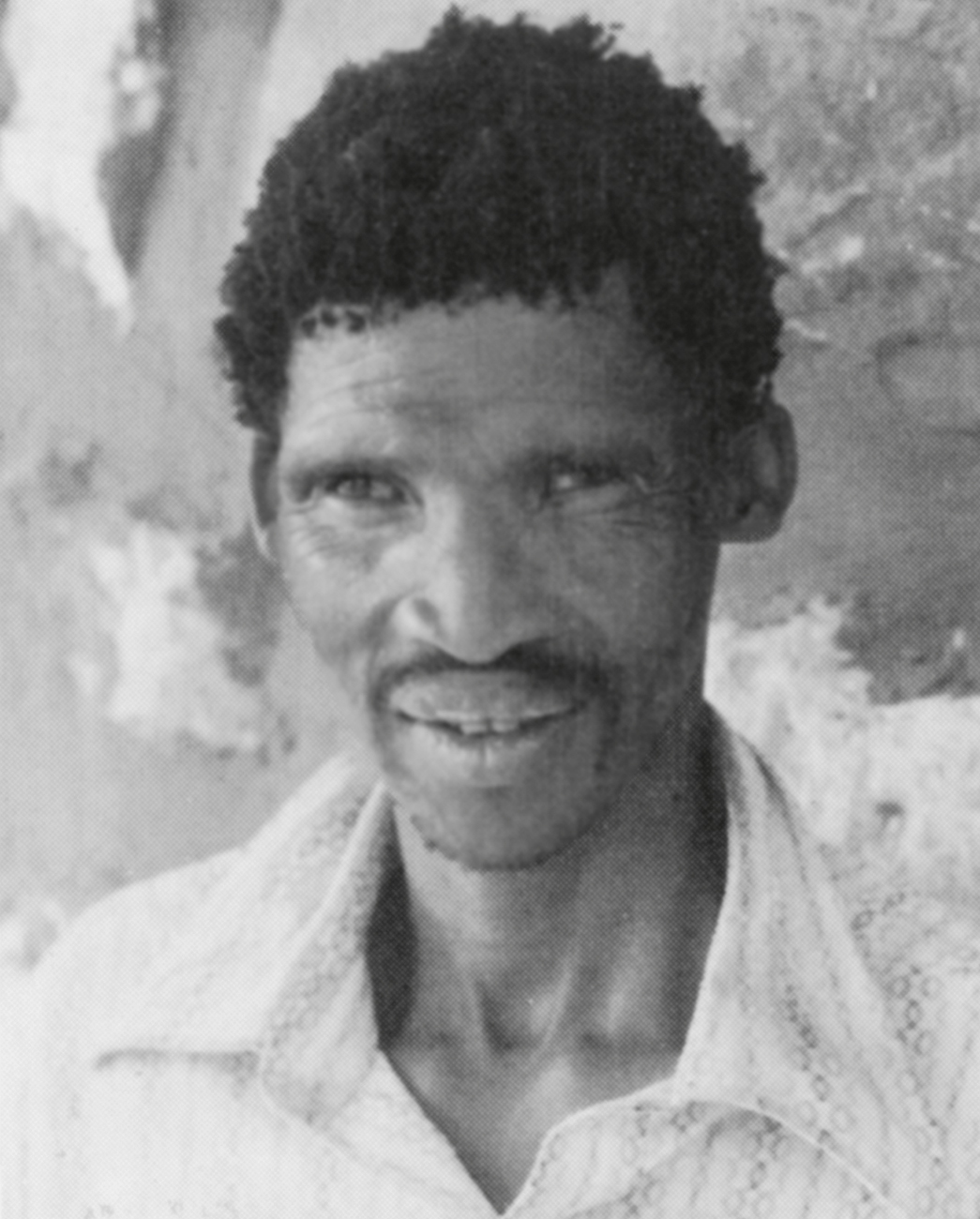

80 Mushaba Isa, a Lega artist who moved to Uganda in 1952 and specialized in carving chairs for the export market.

Many of these patrons and brokers are not known outside the countries in which they were active. Instead, we are limited to a handful of well-publicized cases dating from late colonialism through the early years of independent statehood, roughly a twenty-five-year period from the mid-1950s to late 1970s. They include Ulli and Georgina Beier as well as Susanne Wenger in Nigeria, Frank McEwen and Tom Blomefield in Rhodesia, Pierre Romain-Desfossés and Pierre Lods in the Belgian and French Congo and Pancho Guedes in Mozambique. Cecil Skotnes and later Bill Ainslie in South Africa could also be included, and besides this small core of independent agents, missionary-sponsored projects also developed important artists during the same period. The most written-about have been Father Kevin Carroll in Nigeria, Canon Paterson and Father Groeber in Rhodesia and Ulla and Peder Gowenius in South Africa. There were also influential expatriate art teachers in colonial schools and universities everywhere, including Kenneth Murray, Dennis Duerden and David Heathcote in Nigeria, Margaret Trowell in Uganda and dozens of others. Finally there were foreign philanthropists interested in promoting new African art – the Harmon, Farfield and Gulbenkian Foundations as well as the more controversial Congress for Cultural Freedom. While these usually did not interact with artists directly, they underwrote publications as well as bricks-and-mortar projects. In the same vein, certain large corporations such as Esso, BAT and BMW sponsored annual countrywide art competitions that uncovered artistic potential in unexpected places. Each functioned in crucial patronage roles.

81 Jak Katarikawe, People Happy at Christmas, c. 1986. Katarikawe was a taxi driver in Kampala before being encouraged towards art by David Cook, a professor of literature at the University of Makerere.

The most widely written about of these early patrons has surely been Frank McEwen, universally lionized in the 1960s and 1970s, but more recently held up to the cold scrutiny of postmodern criticism and judged as an excessively purist icon of high modernism. McEwen, born in Mexico in 1907 to a French mother and British art-dealer father, was brought up in England but made his way to Paris as an aspiring artist in 1925. There he studied painting and restoration, attended Henri Focillon’s lectures in art history at the Sorbonne, and came to know many of the artists active in the 1930s avant-garde as well as their patrons, both of whom were frequently collectors of African art. These included Picasso, Matisse, Braque, Léger, Daniel Henry Kahnweiler, Tristan Tzara and Michel Leiris. He was particularly drawn to the unconventional theories of Matisse’s teacher Gustave Moreau, which forbade direct instruction or copying and stressed the necessity for artists to reach inside themselves for the source of their creativity. These ideas were the focus of a workshop he organized in 1938 in Toulon, and again when he went to Africa in 1956 to become the first director of the new National Gallery in what was then Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia (since 1982, Harare, Zimbabwe). Between 1938 and 1956 he had established himself as an art reviewer and curator in Paris and in 1945 had brought the first Picasso and Matisse show to London. McEwen, like others in his circle, was influenced by Focillon’s notions of the archaic and the primitive in art, as well as by Carl Jung’s theories of the collective unconscious, all of which were critical in forming his views of what the sources of creativity in African art ought to be. But what he found on his arrival in Salisbury was little more than modest souvenir production, in a conservative white-settler-dominated society that had no use for either avant-garde modernism or the African collective unconscious. Despite this, in only a few years he was able to bring forth a thriving group of stone sculptors, and beyond that, to blur the boundaries of ethnography and patronage by establishing an intellectual framework for this sculpture to be interpreted within.

The ‘experiment’, as it was usually called, began with his giving painting materials to Thomas Mukarobgwa (1924–1999) and Paul Gwichiri (b. 1938), whom he had hired as young museum attendants.[83] McEwen frequently referred to their early paintings as a type of ‘adult child art’. A few years later, when the emphasis in the workshop had shifted to sculpture in stone, he referred to a ‘pre-columbian’ phase that followed a stage of ‘heavy primitivism’ before ‘achieving personal sophistication’. Even without Focillon and Jung looking over his shoulder, McEwen’s easy familiarity with the stone sculpture of Henry Moore and the work of Picasso and Matisse would have been sufficient for him to frame the workshop sculpture in this kind of discourse.[82] In news releases and interviews he attributed the early workshop paintings to an ‘innate African aesthetic’ from which the German expressionists drew their inspiration. This aesthetic, since it had no obvious local precursors in the immediate past, was endowed with a mysticism ‘at which we do not cease to wonder but for which there are no obvious explanations.’

82 Henry Moore, Divided Head, 1963

As the workshop became known, many of the artists came to speak in similarly mystical terms about their work, but initially they viewed it pragmatically – it provided a chance for economic security in a settler society with few avenues of advancement for Africans. For Mukarobgwa, it allowed him to give up his job as a bicycle messenger for a much more promising one as an attendant and fledgling painter at the new National Gallery. In an interview in 1996 he recalled how he had been hired after a chance encounter with McEwen at the gallery’s construction site:

TM: From [July 1957] I was working and he gives us…watercolour paint for us to go and try because I didn’t even know how to use the paint…and then we go work at our Township, in the African Township…then we show to him. He was pleased with mine…then he bought it….As I carried on, he decided that I should go out and talk to other people…so then we can open the workshop here in the National Gallery….All these artists – [Nicholas] Mukomberanwa, Sylvester Mubayi, Joseph Andika – all these who are expanding….They all come from the idea of Frank McEwen.

SLK [Sidney Littlefield Kasfir]: Why did he switch over from watercolours to sculpture?

TM: Why he has done that is that he knew there are some other things which you cannot put into painting which you can put into the sculptures. So they can give more movement in the sculptures than in the painting. [But] there are people born as a painter, he knew that because he had been with Picasso….Picasso had never been into Africa but he had influence.

McEwen’s all-embracing presence is evident in his role as teacher. Important lessons about originality were demonstrated to the workshop artists by the travelling exhibitions of Picasso and Moore which he brought to the gallery. In Moore’s case, his monumental figures must have also provided an explicit model of how to exploit stone as a sculptural medium.

SLK: So [McEwen] brought an exhibition of Picasso’s work here to this gallery…and did he go through the exhibition with you and talk about these things?

TM: That’s what he used to do. He used to take the whole group. Everyone would have to join in order to hear what he was explaining about. Because he used to explain nicely and he used to know every colour, why it was put there. He was such a wonderful genius. You know, he used to know quite a number of things.

SLK: Was he a painter himself?

TM: No, actually. Just because he had grown into art for all of his life. He was the person who loves art.

83 Thomas Mukarobgwa, Suggest Paintings: Adam and Eve, 1963

The shift in emphasis from painting to stone carving in the early to mid-1960s was a complicated leap of faith on McEwen’s part. It was a direction in which the hoped-for Jungian mythic connection to the past could be developed, perhaps around the controversial stone ruins of Great Zimbabwe, which the archaeologist Gertrude Caton Thompson had concluded were of local Shona origin. Local sculpture was also being produced, though not the kind he wanted – souvenir soapstone and woodcarvings and, more importantly, sculpture in the service of the Church at the Cyrene and Serima missions, the former of which trained Samuel Songo (b. 1929) in the early 1950s and the latter Nicholas Mukomberanwa (1940–2000) a decade later.[84, 85] Joram Mariga (1927–2000), who became a central creative force in the stone sculpture movement, had begun a steatite (soapstone) and wood-carving workshop in Nyanga in the mountainous eastern highlands in the late 1950s. McEwen was not aware of its existence until 1961, but soon afterwards he was exhibiting the work of Mariga and his nephew John Takawira in the National Gallery.

As various sculptors were assimilated into McEwen’s project, they abandoned their early representational pieces and heeded his advice to look deep within themselves to a collective Shona mythology and avoid anything that bore the taint of ‘airport art’ – a term he coined – including both realist representations of all kinds and common carving materials such as wood and soapstone. These were replaced by serpentine – a metamorphic rock, which can be soft or hard and capable of a high polish – and other harder stones. The sharp distinction that McEwen drew between pure, original artistic expression and a practice aimed at the craft and souvenir market was deeply impressed upon the early workshop sculptors. Mukarobgwa still spoke of it eloquently forty years later:

TM: We want to do something absent which you can bring from your mind into your eye and you talk with it until the last of your work and you can say, ‘Yes I’ve finished’. And that work which you finish can also say ‘yes’ to you when you have finished it in the way you feel because it has been created by your spirit…when you’re trying to do work on behalf of someone…that’s not yours. He [McEwen] was trying to explain that. He was trying to give an example of when you have a child, that child is not going to look like [another] man. Because if it is created definitely by your blood, you have created…a very original one. So that’s what he used to explain.

SLK: So your sculptures are like your children in that way.

TM: Yes. Sometimes you can do your features on your sculptures or even your painting figures.

Mukarobgwa frequently returned to the contrast between this inward-directed artistic process and the work being done now by younger Zimbabweans based on either international models or emulation of the stone sculpture of his generation. He acknowledged that a certain amount of copying must occur during the early stages of the learning process for any artist, but it should be temporary:

TM: Now you should find your own way, how to do things in order to develop. But if you stand still as the way you have been taught, you are nothing. You are not trying to make other people think how things should be done.

SLK: …once they get past the stage of being a student who’s learning, and can work on their own, you’re saying that they need to develop their own way of working. But what of all the things they’ve seen?

TM: They can combine, but not very much. They must show their tribes.

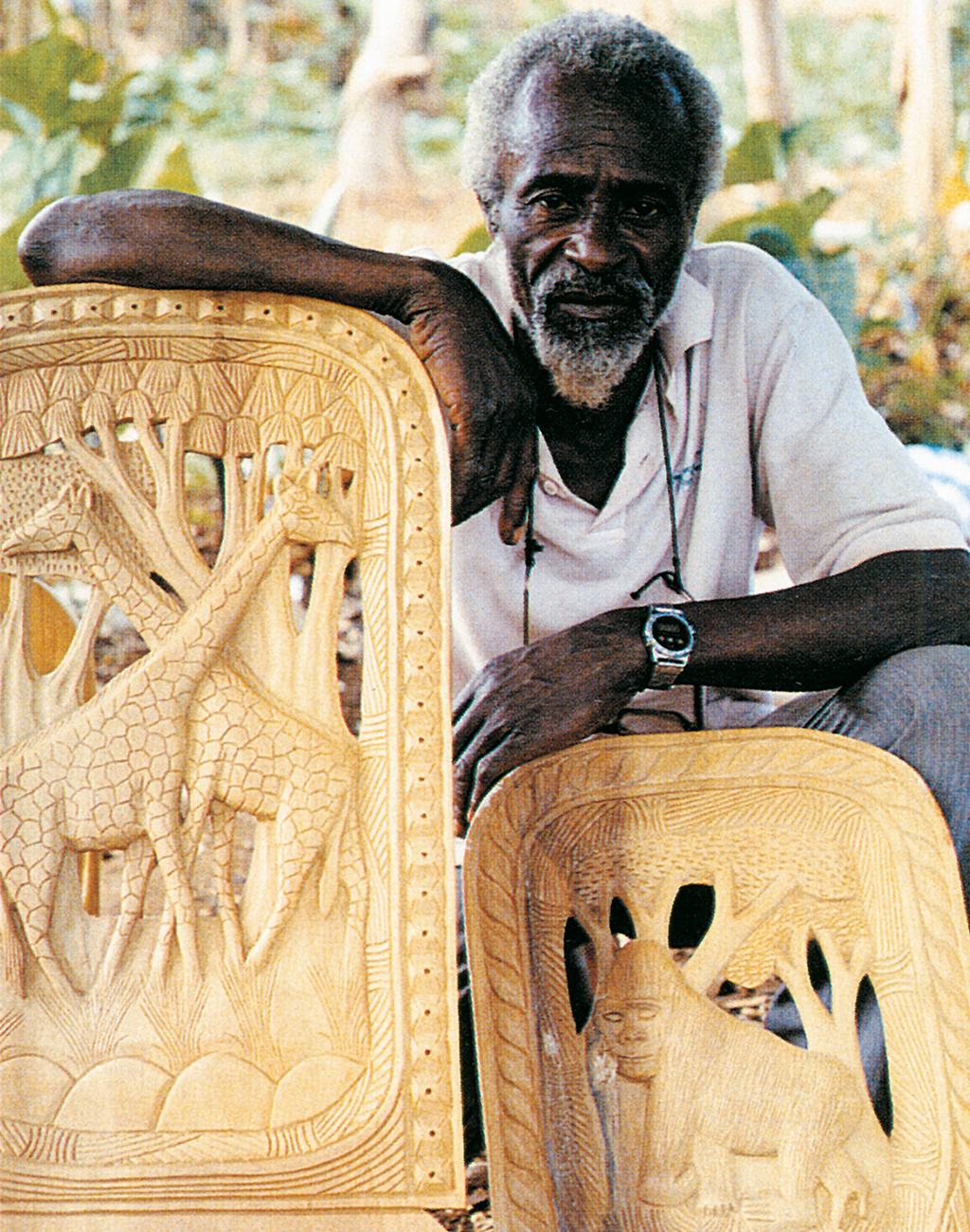

84 Nicholas Mukomberanwa, Man, 1969

85 Joram Mariga, Anteater, 1990

In this philosophy, which is Mukarobgwa’s personal reinterpretation of McEwen’s ideas (devolved in turn from Moreau, Jung and Focillon), originality is foremost and has two elements: a deeply individual consciousness unique to each artist, and a collective one drawn unconsciously from shared historical experience (‘their tribes’). But it disapproves of that element in art which intentionally plays with, comments upon or borrows from other art beyond ‘the tribe’.

Unbidden, the political independence movement intervened in the direction the workshop was to take. With the announcement of UDI (the Unilateral Declaration of Independence) Ian Smith’s white minority government broke all ties with Britain in 1965. and in retaliation the British government imposed an economic boycott that was to affect the development of new art deeply. Imports such as paint supplies disappeared almost overnight, making sculpture not just a workshop choice but a necessity. Smith’s government blacklisted McEwen, who fraternized with the workshop artists and violated white separatist principles. In 1969 Joram Mariga helped McEwen to move the workshop out of the National Gallery to Vukutu in the Nyanga mountains, to lessen government surveillance and remove the artists from market pressures to sell, but also to create a residential community for those artists already trained by Mariga at Nyanga. This new location inspired McEwen to reframe the workshop as a ‘bush school’ and to look to Shona ethnography and history for an explanation of the sculpture. The stories told to him by sculptors Joseph Ndandarika (‘previously apprenticed to a famous wizard’) and Thomas Mukarobgwa (‘a master of folk knowledge and ancient myth’) provided McEwen with the evidence he wanted. At Vukutu, his new American wife Mary McEwen encouraged sculptors to develop themes out of Shona tradition and a monthly prize was awarded for the best example. In an illustrated pamphlet on the Workshop School, McEwen alluded to the ‘mystic secret’ of ‘sacred caves concealing numerous and varied ancestor figures carved in stone’, as well as the handful of documented steatite bird sculptures taken from the Great Zimbabwe ruins. Photographs of a Nyau society masquerade performance link the artists in the workshop to an unspoiled, traditional Africa, while their sculpture is said to be ‘born directly, locally, from natural elements in the virgin ground.’ Two historical issues are skirted here, however. Firstly, some of the artists who joined the workshop had learned to carve at the Cyrene and Serima missions, and themes such as the Mother and Child were also biblical, not simply indigenous. Secondly, others – particularly those belonging to the Chewa Nyau society – were not Shona, undercutting the idea of an ancient Shona tradition of ancestor figures concealed in caves, or stone birds from Shona architectural ruins (zimbabwes) informing their work. These attempts to frame creativity as a response to a collective mythic past have ironically become the rhetoric upon which a ‘Spirits in Stone’ carving industry has been founded by the very entrepreneurs whom McEwen tried to keep at bay.

Nonetheless, the combination of the unquestionable power of much of the early workshop sculpture with McEwen’s interpretive strategies and unsurpassed art-world connections propelled this work onto the international stage of modern art. In 1962 he arranged the First International Congress of African Culture, in which art from all over the continent was exhibited in Salisbury, and its international participants (including the renowned African art scholar William Fagg and Alfred Barr Jr, the former director of the Museum of Modern Art, New York) were introduced to early workshop painting and sculpture. This was followed by an exhibition in London at the Commonwealth Institute in 1963, and after the expansion of the workshop to Nyanga, the Museum of Modern Art in New York organized a show of forty-six works that toured the United States during 1968 and 1969 under the title ‘New African Art from the Central African Workshop School’.

But after the imposition of the 1965 economic boycott, McEwen no longer exercised complete control over the promotion of stone sculpture in Rhodesia, and other styles of cultural brokerage and of sculpture itself emerged. The central figure in this was Tom Blomefield, a tobacco farmer from Tengenenge, 150 km north of the capital in the mountains of the Great Dyke. Blomefield had been hit hard by the British ban on the importation of Rhodesian tobacco. Discovering a large deposit of serpentine on his farm property, he enlisted the help of Lemon Moses, a sculptor from Malawi, to help set up a carving group among his migrant farm workers, most of whom were Chewa and Yao from Malawi or Mozambique and Mbunda from Angola. Between 1966 and 1969, these stone carvers, including the Shona sculptors Henry Munyaradzi and Bernard Matemera, the Yao artists Josia Manzi and Amali Mailolo and several others, exhibited under McEwen’s patronage at the National Gallery in Salisbury.[86] However, Blomefield’s approach differed radically from McEwen’s in the degree of control he thought it was crucial to exert.[87] Works that McEwen rejected were sent later by Blomefield to be exhibited and sold in South Africa – on the principle that the artists must be able to preserve their own independence, both aesthetically and economically. Blomefield’s personal style was different from McEwen’s: he spoke fluent Chewa instead of French, was an artist himself (trained by Mariga’s student Crispen Chakanyoka) and was able to operate in an environment of relaxed mutual respect which allowed talent to develop without being subjected to museum-style critique. Inevitably, his methods and McEwen’s could not coexist peacefully; McEwen thought that the workshop’s reputation would be undermined by the promotion of work that fell beneath his own standards. After 1969 the Tengenenge artists were not invited to exhibit at the National Gallery until McEwen left in 1973.

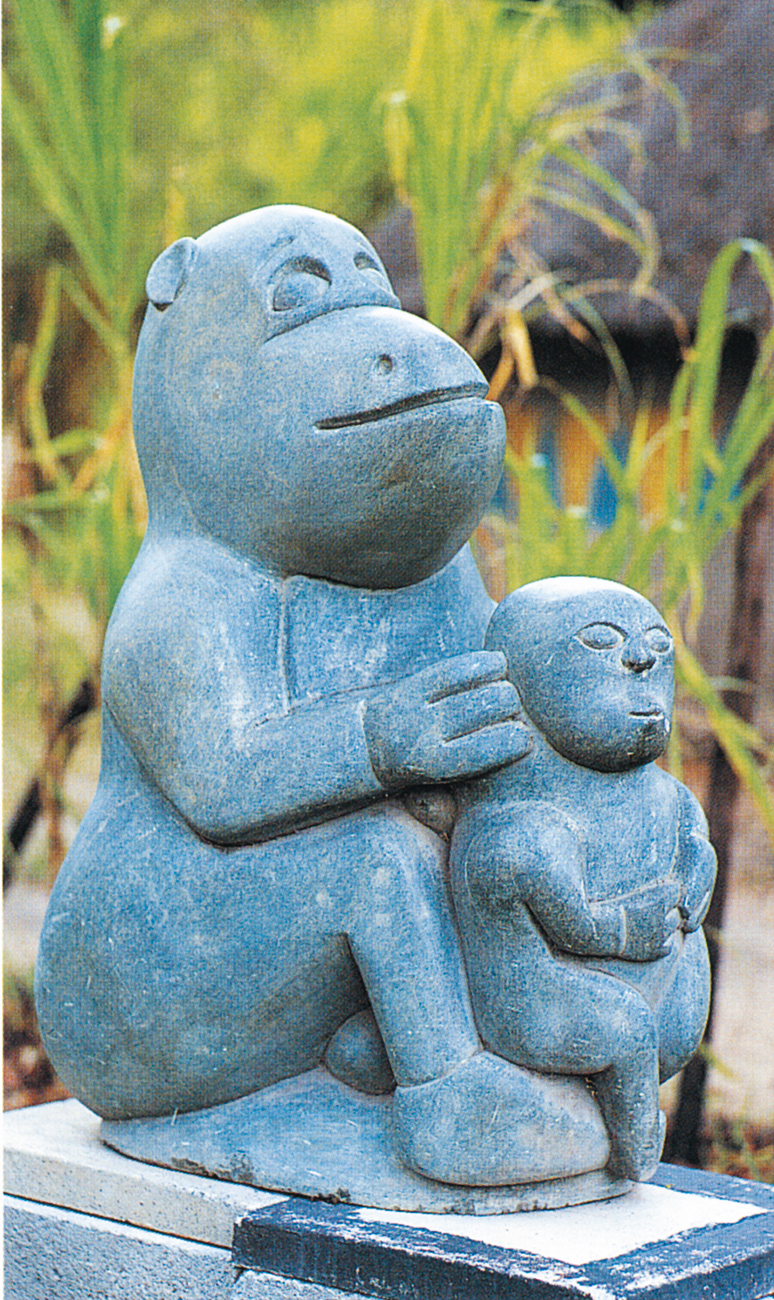

86 Josia Manzi, Baboon Stealing the Crop Guard’s Child, n.d.

87 Amali Mailolo, Man and Crocodile, n.d.

During the troubled years of the Chimurenga (war for independence), the greatest support for the sculptors came from Blomefield, who purchased houses for several of them in Salisbury, and from Roy Guthrie, who from 1973 was the director of Gallery Shona Sculpture, a private gallery in a complex on the outskirts of the city now known as Chapungu Sculpture Park. McEwen, by then in his seventies, never returned to Rhodesia, living out his years in France. He hoped to write a book about the Workshop School, but the economic boycott prevented the National Gallery from providing him with any funds.

Despite its crucial role, patronage alone cannot bring art into being, and Zimbabwe stone sculpture was not the creation of its patron-brokers. Significantly, the range of specific thematic content had little or nothing to do with either McEwen or Blomefield.[89] Joram Mariga had begun a workshop before either of them; if anyone is the ‘father’ of the movement, it is him. There is not a single style or attitude towards the stone itself, but a wide range, from the smooth-fleshed descriptive fantasies of Amali Mailolo to the rough and unfinished semi-abstraction of Damien Manuhwa.[88] Perhaps the one thing these artists have in common is an army of imitators, from street sellers to artists whose work is sold along with theirs in galleries and abroad by (mostly white) Zimbabwean dealers and promoters.

88 Damien Manuhwa, Creation of a Woman, n.d.

The elaborate and conflicting discourse that has resulted from this industry has helped sell Zimbabwe stone sculpture, but has also hurt it critically. While Newsweek proclaimed in 1987 that Shona sculpture was the most important art form to emerge from Africa in the twentieth century, it was not included in major exhibitions such as ‘Africa Explores’ in New York in 1991 (supposedly because the artists were well established) or ‘Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa’ in London in 1995 (perhaps because their ‘story’ had been heard too many times). The other, unspoken reason in both cases may be that the artists were too obviously successful, invoking curatorial suspicions of a descent into formulaic repetition. Furthermore, the high visibility of certain patron-brokers has, in the eyes of critics and scholars, cast the artists’ own agency into doubt. This has happened in many workshop situations – not only in Zimbabwe. Hierarchies of value were created in the early 1960s by the monthly prize at Vukutu for the ‘best traditional theme’, and in Osogbo, Nigeria, when Georgina and Ulli Beier selected the best workshop pictures each day and hung them for everyone to see. These hierarchies of value mattered at that moment, but are progressively diluted over time as artists gain experience and develop a greater awareness of what they are doing.

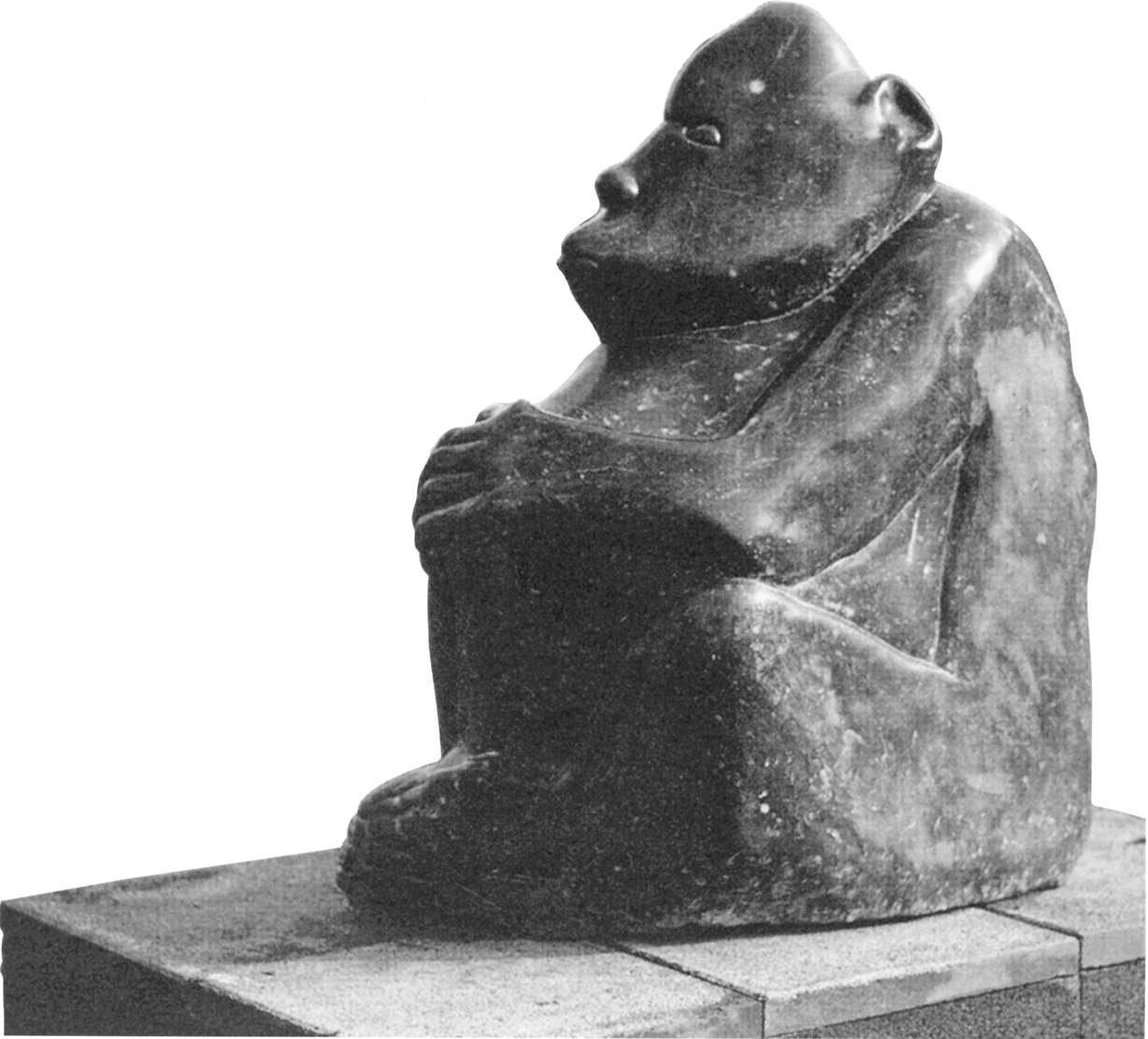

89 Joram Mariga, Chief Chirorodziwa, n.d.

Osogbo, the workshop movement whose issues run like a thread through this book, differed in two important ways from Salisbury. Georgina Beier, a painter herself, provided a strong experiential model, beginning with her stage sets for Duro Ladipo’s theatre productions, which were put together by the same individuals who later participated in the 1964 workshop. Other Osogbo workshops in the early 1960s and 1970s were also run by practising artists, from the Guyanan painter Denis Williams to Dutch printmaker Ru Van Rossem and Nigerian printmaker Bruce Onobrakpeya. At Salisbury, McEwen stage-managed, but did not play the artist role himself or put an artist in charge. However, his workshop project lasted more than a decade, and hundreds of artists passed through it. By contrast, workshops at Osogbo were extremely brief, the 1964 session only lasting a week. It is difficult to quantify influences, which ultimately depend as much on receptivity and chance encounters as on the duration or structure of the workshops.

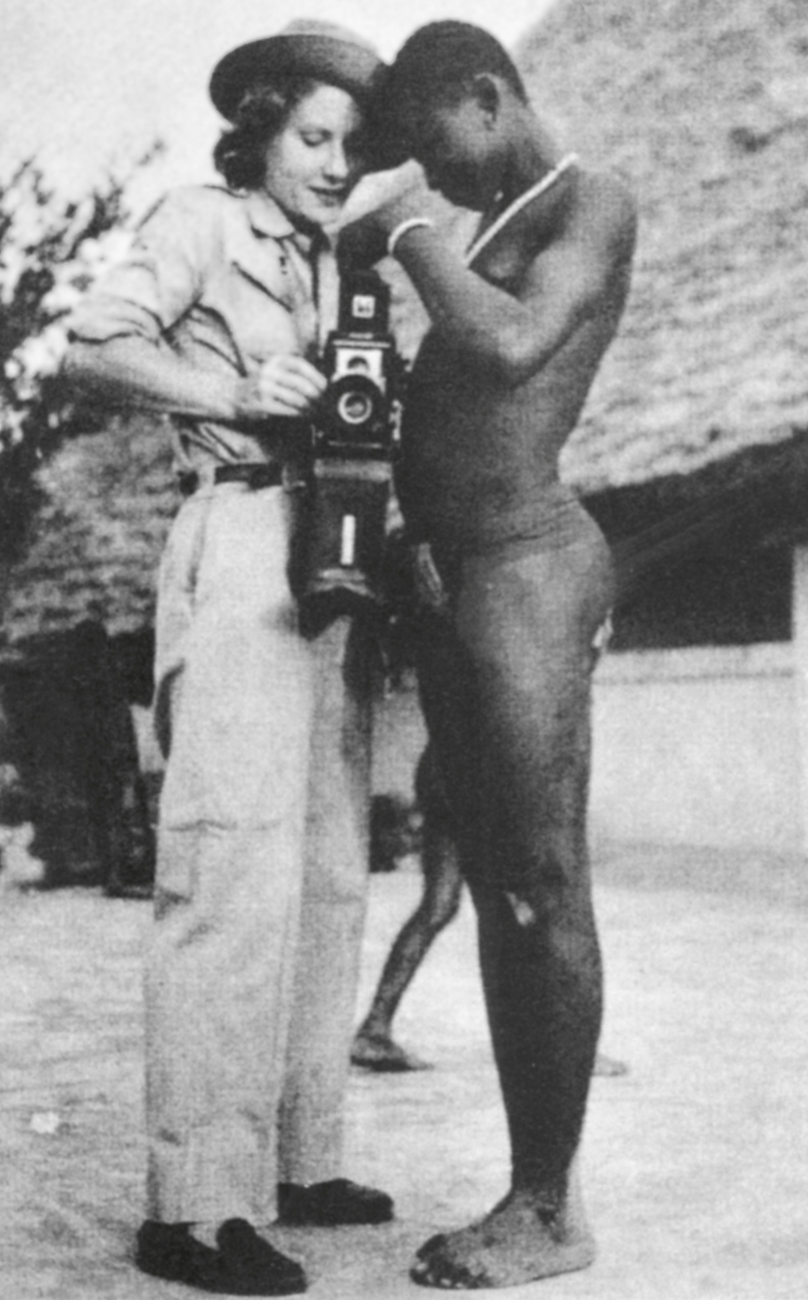

In the 1960s it was confidently assumed that Africa would develop indigenous patronage for new art forms as it emerged from the socio-economic climate of colonialism, but contemporary art patronage is still dominated by European, American and white southern African dealers, promoters and collectors, leaving the curios and dubious ‘antiquities’ to mainly African and Indian traders. Ruth Schaffner, the owner of Gallery Watatu in Nairobi, Kenya, from 1984 until her death in 1996 at the age of eighty-two, was a member of the same European generation as McEwen. Like him and her younger countryman Ulli Beier, she believed that academic instruction spoiled the innate creativity of African artists. The daughter of intellectual emigrés from Hitler’s Germany, she studied economics at the New School in New York and then began a career as a photographer. She travelled to Côte d’Ivoire in 1948 with her first husband, filmmaker Hassoldt Davis, but did not return to Africa until 1984, having spent more than a decade running galleries devoted to contemporary art in Los Angeles and Santa Barbara.[90]

At Watatu, Nairobi’s leading gallery until its closure in 2013, eighty per cent or more of the artists were ‘self-taught’. Schaffner’s relationship with them was complex and familial, despite her reputation as an astute businesswoman. She lent them money for painting materials, paid their children’s school fees and gave cash advances against hoped-for sales. In return she expected total loyalty, exclusive representation, and from the early 1990s took a fifty per cent commission on their sales. Her justification for this unusually high rate for an African gallery was that she could command much higher prices for their work than lesser-known galleries and could therefore make more money for them in the end, a point disputed by some of the artists.

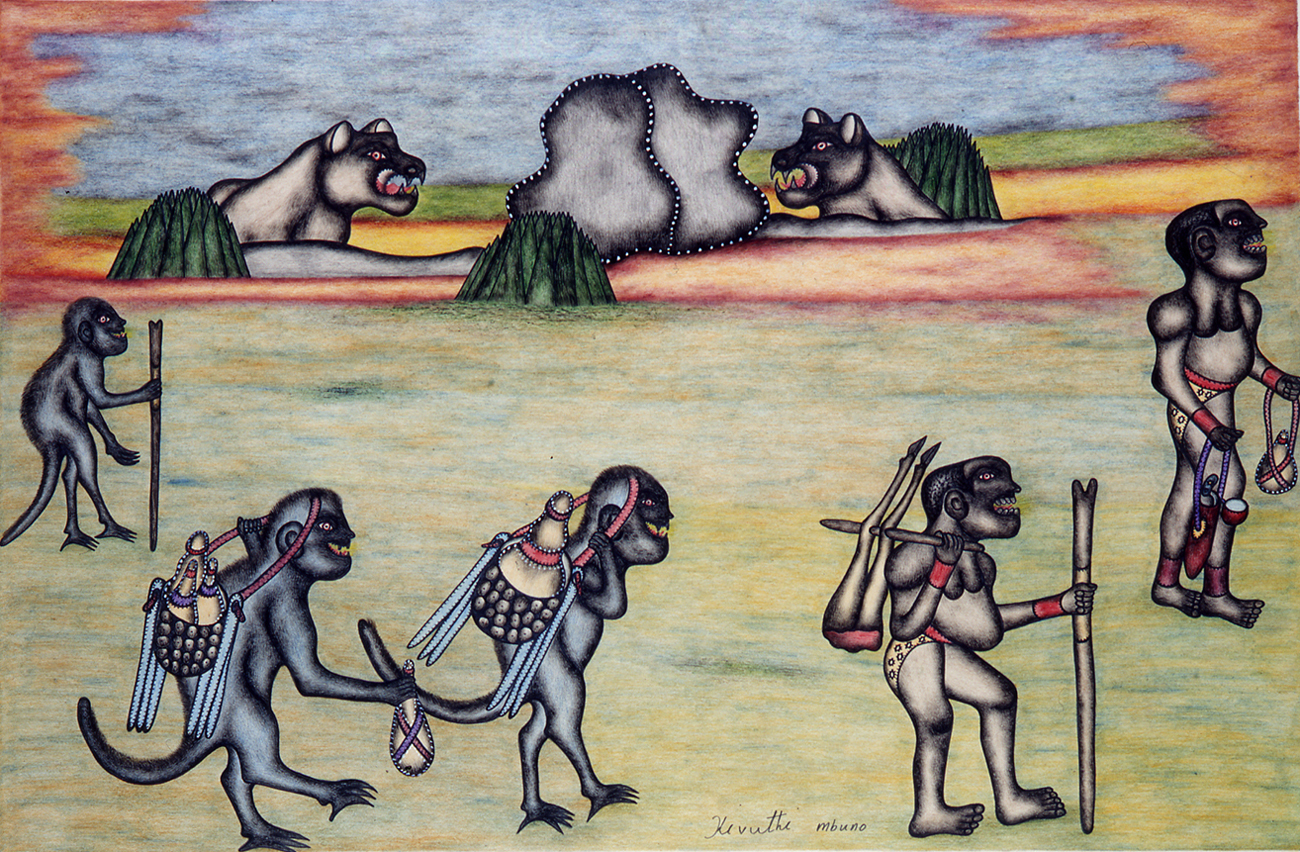

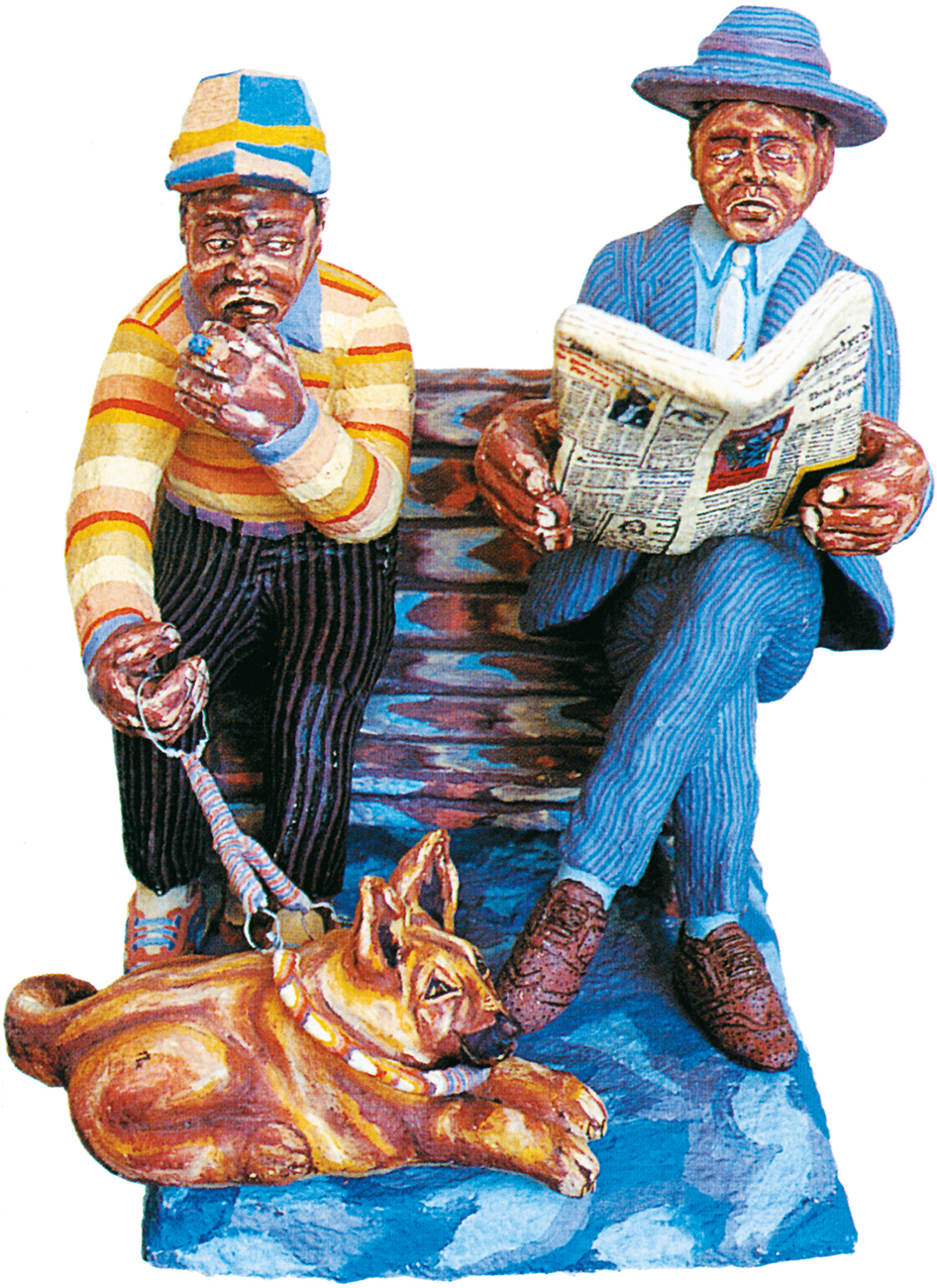

Like McEwen, she had strong opinions and her judgments were final. Once a month Watatu Foundation held an ‘artists’ day’ when new and would-be artists were encouraged to bring their work for appraisal and feedback. In her last years, Schaffner was too overburdened to perform this task herself and increasingly delegated it to her staff, but while she was alive it remained the litmus test of whether an artist’s work held possibilities and would fit within the range of cultural production that Watatu actively cultivated. This is not to say that all Watatu artists’ work bears a generic stamp of likeness – it clearly does not – but it does encompass certain possibilities and exclude others. Just as McEwen forbade descriptive realism, so Schaffner usually avoided pictorial styles that reflected academic training or European-derived preoccupations with abstraction. Scenes of urban and rural life, or those expressing fantasy, such as Kivuthi Mbuno (b. 1947), were encouraged because they fit with both the ‘primitivism’ preferred by buyers and the intellectual assumptions upon which Schaffner herself guided the gallery’s patronage.[91] Sane (Mbugua) Wadu (b. 1954) is an artist in point.[92] A former primary-school teacher who left the classroom to become a successful painter under Schaffner’s patronage, ‘Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa’ curator Wanjiku Nyachae has described how Wadu arrived at Gallery Watatu wearing an improbable canvas suit he had painted himself and carrying shopping bags containing rolled-up pictures. In his community people had begun to call him ‘Insane’ Wadu. Schaffner gave him materials, and four months later he had his first show at Watatu. He subsequently began to call himself ‘Sane’ and others followed. His thematic repertory, like that of the Kinshasa flour-sack painters or the Weya women (see Chapter 5), is full of narrative detail taken from the everyday life of ordinary people: bus passengers, a crowd listening to an evangelist in a Nairobi park, someone on a bicycle. But the crowded pictorial compositions, frontal stares of their subjects and swirling impasto brushstrokes give his work a wild energy not seen in that of most of the Watatu artists’ work.

90 Ruth Schaffner with a young Lobi woman, on location filming Sorcerer’s Village, directed by her husband, Hassoldt Davis, early 1950s

91 Kivuthi Mbuno, Mutinda, 1992

One outcome of Schaffner’s artists’ successes has been their emulation, usually by members of their family or community. As elsewhere among unschooled artists, imitating a successful model has been seen as both pragmatic and commendable, creating a problem for Schaffner and for Watatu, where originality was assumed to issue forth naturally from untrammelled artistic expression. People in Ngecha, Wadu’s hometown near Nairobi, soon began to see the benefits of becoming a painter and in the early 1990s started bringing samples of their work to the monthly artists’ days at Watatu.

In 1995 the artists (including Wadu’s talented sister, Lucy Njeri) formed the Ngecha Artists’ Association and workspace.[93] Not wishing to lose them, Schaffner responded by helping with fundraising, and held informal artist workshops at the Ngecha YMCA. What Schaffner’s patronage demonstrates is the fine line that exists between encouraging a whole community to become artists and the new direction, no longer within gallery control, which often results when the group organizes itself. The premise that ‘art comes from art’ (see Chapter 6) has two sides – it is the primary reason for the emergence of ‘movements’, ‘schools’ or group styles, but it is also the guiding principle of emulation and of commodification. This is not to say that a scaled-down art-world version of mass production is necessarily the outcome of such projects – highly personal styles of art-making may also emerge.

92 Sane Wadu, Waiting, 1991–92. This image of protests on the eve of the Kenyan elections includes a self-portrait – the bearded figure at the bottom – among the protesters.

93 Lucy Njeri, Can the Landers Invert?, 1998

94 Peterson Kamwathi, Untitled (Movement), diptych from Queue series, 2009–10. Kamwathi stands apart among Kenyan artists: while he is young, educated and highly articulate, unlike others he is largely self-taught as an artist and his choice of both medium (charcoal on paper) and subjects are atypical. Here, everyday life, such as the necessity of standing in queues for everything from postage stamps to identity documents, is revealed in a powerful way.

Banana Hill is another rural community near Nairobi with an artists’ association, now called Banana Hill Art Gallery. The painters Shine Tani (Shetani or ‘Devil’, aka Simon Njenga Mwangi, b. 1967), a former street acrobat and founding member of the association, and Cartoon Joseph (aka Joseph Njuguna Kamau, b. 1973) both make work which is far from emulative and possesses an exuberance which is extremely difficult for formally trained artists to achieve, partly because it ignores most of the rules of composition and partly because its subjects are taken from the street and not the studio.[96] But resounding artistic success itself also breeds imitation, whether in New York or Nairobi.[95]

95 Cartoon Joseph, Untitled village scene, 1998

96 Shine Tani, Homestead Acrobats, 1997

Not all workshop patronage has followed the McEwen–Schaffner model of a well-connected art professional from abroad organizing a group of previously untutored African artists on their home ground. Beginning in the mid-1980s, more egalitarian (though no less brokered) international workshops, which presume that the key to creativity lies elsewhere, in encounters with unfamiliar cultural models and artistic practice, have taken place. These developed out of the Triangle Workshop model, and in one sense have no ‘patron’ since they are organized by the artists themselves – though financial backers are necessary and in the African versions have been primarily corporate, cultural or development organizations such as the British Council. The original Triangle workshop was organized in New York in 1982 by the British collector Robert Loder and the artist Anthony Caro, and involved participants from the ‘triangle’ of the USA, Canada and the UK.

97 Dumisani Mabaso, Untitled, 1988

Because the ANC-imposed Cultural Boycott was still in effect in the 1980s, there were few opportunities then for South African artists to break out of their isolation. However, in 1984, South African artists Bill Ainslie and David Koloane joined those participating in the Triangle workshop in New York, and in the following year organized the first Thupelo workshop in Johannesburg.[98] Triangle participants were encouraged to return to their home countries and organize annual workshops there in subsequent years. The basic principles are simple enough – several of the artists should come from outside the host country, the workshops should be brief (two weeks long), the encounter is meant to be intense, and to make that happen, it has to be located in an out-of-the-way place where the artists will not be distracted. It is based on a kind of ‘combustion’ theory of creativity – not only does art come from art, but the more heterogeneous the mix and the further from a familiar environment the artist is, the more it is likely to catch fire.

The initial excitement that a workshop generates may linger for a while and die out, or may metastasize into several others. In South Africa, when Thupelo in Johannesburg had run out of energy, new workshops were started in Cape Town and Durban, while several artists from Thupelo became involved in the Bag Factory project in Johannesburg. But, as in the institutionalized art world of biennales and other group shows, there can also be a powerful cultural politics of inclusion that develops around the workshops once they have been established and become regular events. A core group of workshop veterans decides which artists should be invited; its choices may be even-handed, exclusionary or simply idiosyncratic, but are never neutral.

Pachipamwe, the first of these workshops set up outside South Africa, was organized in 1988 by the sculptor Tapfuma Gutsa (b. 1956) in Murewa, Zimbabwe. It brought together some of the country’s most established stone sculptors (Joram Mariga, Bernard Matemera and Brighton Sango) with younger artists who hoped to move Zimbabwean art in new directions. The following year the second Pachipamwe workshop took place at the Cyrene mission and included several artists from abroad – from the UK, Angola, Botswana and South Africa. From there, new workshops were spawned in Botswana (Thapong, 1989), Mozambique (Ujamaa, 1991), the UK (Shave Farm, 1991), Zambia (Mbile, 1993), Jamaica (Xayamaca, 1993), Namibia (Tulipamwe, 1994) and Senegal (Tenq, 1994).

98 Bill Ainslie, Pachipamwe No. 3, 1989

99 Namubiru Rose Kirumira, Untitled, 1996

Namubiru Rose Kirumira (b. 1962), then a young Ugandan sculptor trained by Francis Nnaggenda and now teaching at Makerere, is a typical Triangle participant.[99] She attended the 1995 Mbile workshop in Zambia and the Thapong workshop in Botswana during the same year. Ugandan artists were drawn into the workshop network after Robert Loder had visited Makerere in 1994 during the planning stages for the ‘Africa 95’ events in London. Kirumira and the painter Richard Kabito were selected for the Mbile workshop, and Francis Nnaggenda for a sculpture workshop in Yorkshire in August 1995. After participating in both Mbile and Thapong, in 1996 Kirumira organized a national workshop in Namasagali, to bring together artists from the four major regions of Uganda. She went on to coordinate an international workshop in Uganda, similar to the ones she had attended in Zambia, Botswana and Denmark.

Artists certainly do not participate in the Triangle workshops to make money. The sponsoring institution typically expects to be reimbursed with between thirty and forty per cent of the proceeds of works sold at the exhibition held at the end of the workshop, or by the donation of a work which can then be sold, or both. Despite this, the advantages of professional networking are obvious to many African artists, marginalized as they usually are within a global but Western-dominated system of exhibiting and collecting. Participating is one way to receive invitations to take part in future workshops, to be nominated for travelling fellowships and residencies in foreign countries, and most important of all, to become known on the international gallery circuit.

These advantages may even outweigh the chances for creative encounters, which are not as straightforward as they might seem: as a sculptor in wood and metal, Kirumira found it difficult to both interact with other artists and complete two pieces (the suggested output) in such a short time when she attended the Mbile and Thapong workshops. The two-week duration favours painting over sculpture and installation work, acrylic (because it dries fast) over oil paint and abstraction over figuration.

With the exception of Tenq in 1994, the workshops have been firmly embedded in the English-speaking world. This means that they tap into a particular subset of African countries, which prior to 1996 were mainly in southern Africa. This was not just an accident of the Triangle workshops beginning in New York instead of Paris, but reflects the real differences in anglophone and francophone attitudes towards patronage and perceptions of authenticity in contemporary African art. If one adopts the premise popular among French-speaking European intellectuals that only the untutored artist is likely to exhibit a truly African artistic sensibility, why would one want to create a network of international workshops to dilute it?

100 The San painter Qmao Nxuku, from the Thapong workshop catalogue, 1992

While many established artists do participate, a large number are younger artists, African or otherwise, who have had some professional training but are eager to be able to interact with a larger art world, on the assumption that their work will improve as a result. Those not likely to be involved, on the other hand, are either artist-intellectuals who value introspection over collaboration, or (far more numerous) those African artists who have neither gallery or patron connections, nor the resources to acquire a passport and plane ticket even if they somehow received an invitation. But overriding these tendencies are the real differences among African countries where the workshops have been established, which produce contrasting workshop scenarios.

In Botswana, for example, the population is sparse and there are comparatively few artists, so the National Museum has been an important sponsor for the Thapong workshops, thereby conferring on them a quasi-official status. Internationally, the best-known Botswana artists are the Nharo San of Ghanzi district, who have no formal schooling or regular contact with the art world. To leave them out of the Thapong project would be problematic from the perspective of national cultural politics, but to include them has created its own problems, since they work under the protective umbrella of the Kuru Development Trust and Cultural Centre (see Chapter 3). Kuru has attempted to preserve their artistic identities in relation to a remote rock-painting hunter-gatherer past, a strategy that works well in helping to explain and market their work abroad, but conflicts with the idea of creative exchange at the heart of the Triangle workshop format.

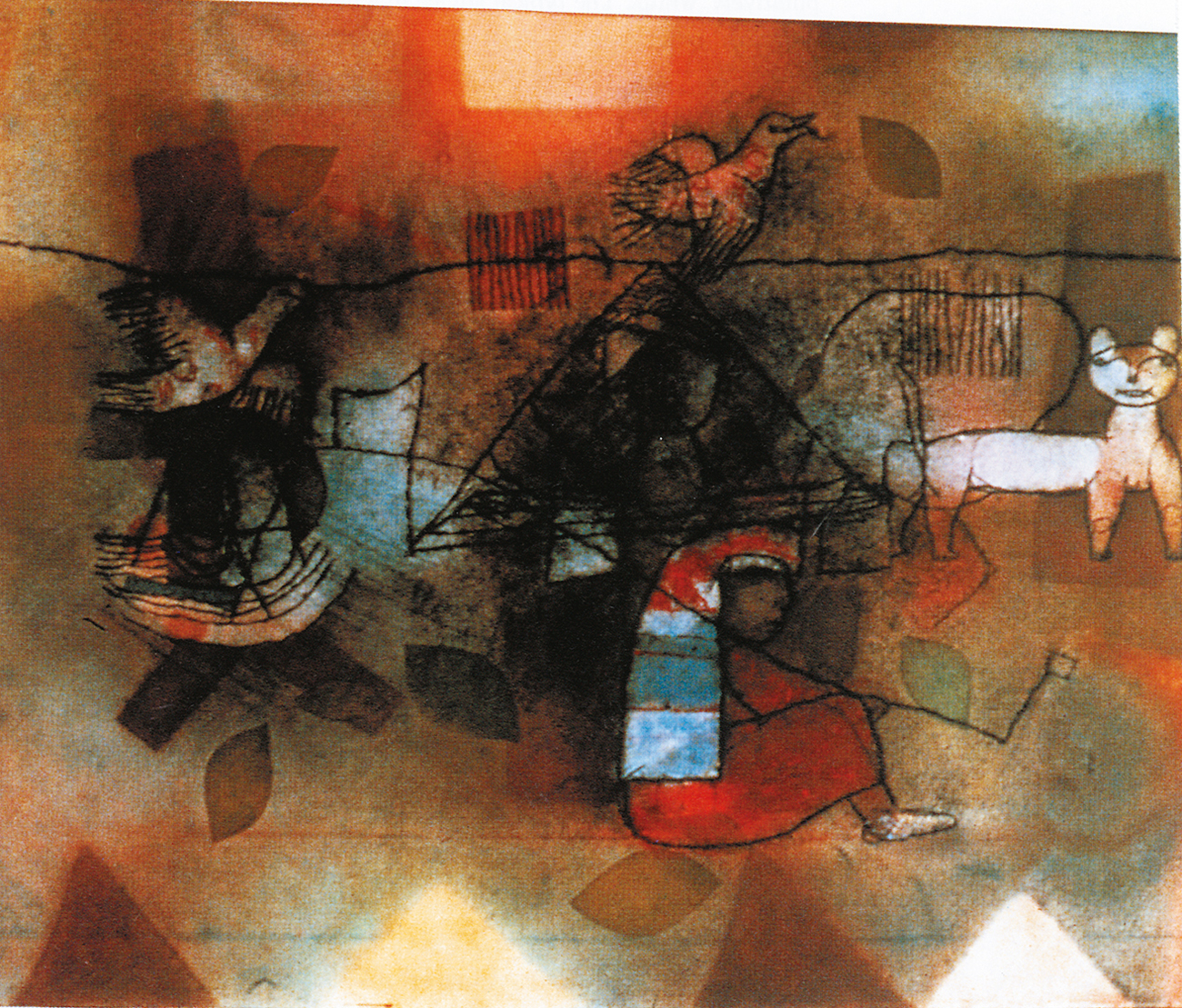

The 1992 Thapong workshop included San painters Qmao Nxuku and Xwexae Dada Qgam, whose participation was an important test of the workshops’ ‘cultural encounter’ thesis.[100, 101] However, !Xrii (1992), a painting Qmao did at the workshop, and The Old People, a lithograph he did in the same year at Kuru, reflect the same style and thematics – conceptually related but spatially unconnected objects and figures typical of Kuru, but not resembling anything else from the Thapong inventory of work produced that year.

101 Qmao Nxuku, !Xrii, 1992

Each of these accounts of brokerage has been centred upon a workshop or gallery, but just as common everywhere are one-to-one relationships between artists and individuals who create opportunities for them. Often these are collectors, but sometimes they are fellow artists. Pip Curling, a Zimbabwean painter, first encountered the work of Givas Mashiri on a street-corner kiosk. Mashiri, a self-fashioned sculptor in Harare who makes figures out of papier maché, was dependent on the street for displaying and selling his work.[103] But as a painter and active board member of the National Gallery, Curling was well-placed to raise Mashiri’s level of exposure by introducing his work to other artists, patrons and gallery owners. Curling also helped the painter Misheck Gudo by turning her garage into a studio for him and teaching him to mix pigments, and arranging a small show of his work in the National Gallery foyer.[102]

102 Misheck Gudo, The Squatter Camp, 1996. Gudo was originally a sculptor, but turned to painting after he was advised by a Harare gallery owner that Zimbabwe was full of sculptors but had few painters.

103 Givas Mashiri, Reading the Standard, 1997

When starting out in the resort town of Malindi on the Kenya coast, the artist Richard Onyango was assisted by a local businessman, Feisal Osman, and the contacts and patronage provided by the resident Italian community. Onyango, like many ‘self-taught’ artists, has paid meticulous attention to buses, cars and other symbols of modernity, but his signature paintings are a series about a white woman called Drosie and his brief involvement with her, her possessions and pastimes. In The Day of Permission (1990), she is lying on a sofa surrounded by a TV, a stereo and souvenir wall plaques with slogans like ‘No War’, and ‘No Shouting please!’, while the artist stands tentatively in the background.[104] Unlike the satirical depictions of South Africans by Tommy Motswai, these minutely observed paintings are not meant to be humorous or ironic. However, the depiction of such subjects is only possible because patronage has exposed the artist to new experiences. These interventions can be crucial to an artist’s repertory and ultimately, career.

104 Richard Onyango, The Day of Permission, 1990

While the political history of South Africa has been different from that of most African countries, achieving majority rule only in 1994, the late-colonial relations between black artists and white patrons has been similar. What has been distinctive is the presence of a resident white intelligentsia large enough to produce its own artists and writers, who during the apartheid era (roughly 1950–94) became brokers for, and sometimes collaborators with, their black counterparts. The same intelligentsia also produced the core of critics, gallery owners, curators and collectors. Today there is much more of an organized ‘art world’ in South Africa than in any other African country, and black artists there are positioned in ways that are reminiscent of African American, Native American and Hispanic artists in the United States – enclaved groups defined primarily by race or ethnicity in relation to art-world institutions, which are still overwhelmingly white. But unlike in the United States or the UK, in South Africa minorities and the majority are racially reversed, so that white artists and critics have emerged out of a small progressive element of the minority population and have been drawn ineluctably into the South African preoccupation with racial and identity politics. And again unlike their counterparts in New York or London, they cannot choose to ignore the conditions of their privilege.

Two kinds of issues have emerged out of this historical situation – that of the relation of black artists and the black subject to the white South African intelligentsia, and from the mid-1970s to the transition to democracy in 1994, the African National Congress’s rhetorical position of the artist as a ‘cultural worker’ in the political struggle to overthrow apartheid. A third issue has to do with the differences in consciousness reflected not only by white artists’ racial and economic privilege, but also by their pedagogical grounding in the Western-style art academy. The latter mirror the differences between formally and informally trained or untrained artists (see Chapter 6), since a majority of white artists fall into the former category and non-white artists into the latter.

The most critical role played by the white liberal intelligentsia, other than that of willing consumer and audience, was as providers of informal training, usually in community centres for the African townships. The custodianship of these artist-mentors allowed a cadre of modern black artists beyond the inevitable makers of wire airplanes and souvenirs or the producers of older genres of ‘tribal’ objects to be possible. Prominent among this initial group of artists were Durant Sihlali, Ephraim Ngatane and Sydney Kumalo, all of whom emerged at the Polly Street Centre in mid-1950s Johannesburg under Cecil Skotnes’ (1926–2009) tutelage.[105] But however well-intentioned and successful (and it was clearly both), this combination of white instruction and patronage was to determine both the direction and the limits of modernism for the black artists who came of age in the 1950s and 1960s.[106] At first glance, this does not set them apart from African artists elsewhere on the continent during those decades, but the difference was that in South Africa this occurred within the all-encompassing official ideology of racial separateness (apartheid), in which white as well as black artists were enmeshed.

Critics David Koloane (himself a non-figurative painter) and Ivor Powell have protested the tendency of white gallery owners and reviewers to encourage the development of ‘township art’ based in social realism, and to discourage artists from more experimental directions. While abstraction became the dominant international style in the 1950s, many South African promoters believed this was an inauthentic direction for black artists, who ought to be depicting the life that surrounded them instead of aspiring to membership of an art world whose centres were far away and putatively ‘white’. The typical advice to a new artist or writer – begin with what you know most intimately – is normally viewed as benign, but in this racially charged context can also be read as a way of setting limits for black artists alone. However, it needs to be seen as one fragment of a larger picture in which all South African art in the 1950s existed on the far periphery of a late-colonial Europe where even white South African artists were largely preoccupied with conventional genres such as landscape, still life and the figure. In such an atmosphere one would expect abstraction to be regarded as suspect. By the late 1970s, for many black artists, and certainly for the freedom movement led by the African National Congress, the human subject was the only subject worthy of exploitation. Therefore, despite being poles apart ideologically, both official white-run institutions and the ANC supported the idea that the proper subject for black artists was some variety of narrative realism.

105 Ephraim Ngatane, Washerwomen, c. 1970. From 1952 to 1954, Ngatane studied with Cecil Skotnes at Polly Street; he went on to study with Durant Sihlali. This painting is a generalized image of women working; its lack of detail renders it outside time and sociological reckoning.

106 Cecil Skotnes, The Commissioners, 1965. In 1963, Skotnes formed a group called Amadlozi (Zulu for ‘spirit of the ancestors’) with four other artists, and their work toured several European cities. The surface of this engraved wood panel has been rolled with black oil paint.

Even more revealing than the encouragement of township subject matter was the bureaucratic pairing of art lessons with games and sports under the general rubric of ‘recreation’. This made administrative sense because the township community centres were multi-purpose – the venues for weddings, funerals and indoor sports as well as art lessons – but it also made it clear that art instruction was not really ‘about’ becoming a practising artist, but instead creating a law-abiding urban worker class interested in self-improvement. Thus Cecil Skotnes was hired initially in 1952 as a ‘cultural recreation officer’ by the Non-European Affairs Department of the Johannesburg City Council. This very limited notion of African creative potential contrasted starkly with that of McEwen in neighbouring Rhodesia during the same period, who believed that he had tapped an ancestral wellspring of limitless possibilities with the Salisbury Workshop School.

The much-debated issue of whether township artists should receive direct academic instruction at these community centres, or should be given minimal technical advice and then left to work in their own way remained the most intractable issue in the construction of African modernism from the 1950s onwards (see Chapter 3). As we have seen, most Western intermediaries came down on the side of advice rather than direct training, on the assumption that Africans have innate (and by implication, unique) artistic abilities, which need only to be uncovered in practice. In Osogbo or Poto-Poto, this may have seemed merely romantic, but in South Africa it was inevitably open to a racial interpretation – that black practitioners were ‘natural’ rather than ‘created’ artists, so (unlike their white counterparts) did not need any formal instruction. Carried a step further, such artists would be ‘contaminated’ by the exposure to many European-derived ideas. It became a point of contention for Polly Street artists such as Louis Maqhubela, who wanted a more complete education in formal technique.[107] After winning a trip to Europe in a major art competition in 1966 he met Douglas Portway, an expatriate South African artist in Cornwall, and began to produce more abstract compositions combining fine linear figuration with diaphanous areas of colour, a development which David Koloane attributes to this post-Polly Street experience.

Durant Sihlali (1935–2004), another major artist who studied with Skotnes between 1953 and 1958, also moved from a documentary approach early in his career towards a more abstract and experimental one, making his own deeply textured paper, which became a crucial part of his finished compositions.[108] But this was a far from simple progression, since Sihlali was also a highly skilled wood and metal sculptor, at home in several media.[109]

107 Louis Maqhubela, Master, late 1960s/early 1970s

108 Durant Sihlali, Graffiti Signatures, 1997. In the words of the artist, ‘From markings on rocks, impressions on walls and caves, to engravings on wood and metal…inscriptions bear witness to the existence of those who lived during a specific period of history. It has been my study for many years…I then reconstruct these on paper or canvas.’

Skotnes himself, a gentle and self-effacing man despite his status as a major icon in South African art history, remembered the Polly Street years somewhat differently than his students. As someone suspicious of manifestoes, artistic or political, he said that he was reluctant to pursue a single set of recommendations for everybody under his tutelage. Classes at Polly Street were only held twice a week, but several of the artists supplemented this with visits to Skotnes’ own studio to work on specific technical issues. Aside from this, the artists, who came from different townships, did not spend much time together, which precluded the development of a Polly Street ‘school’ of painting. Skotnes’ tutelage was much less aggressive than that of many teachers and sponsors during the 1950s and early 1960s, neither insisting, like Margaret Trowell, Kevin Carroll and Kenneth Murray (see Chapter 6), that students draw upon tradition, nor, like Frank McEwen, that they conjure it out of a forgotten past.

109 Durant Sihlali in his studio with one of his bronze sculptures, 1996

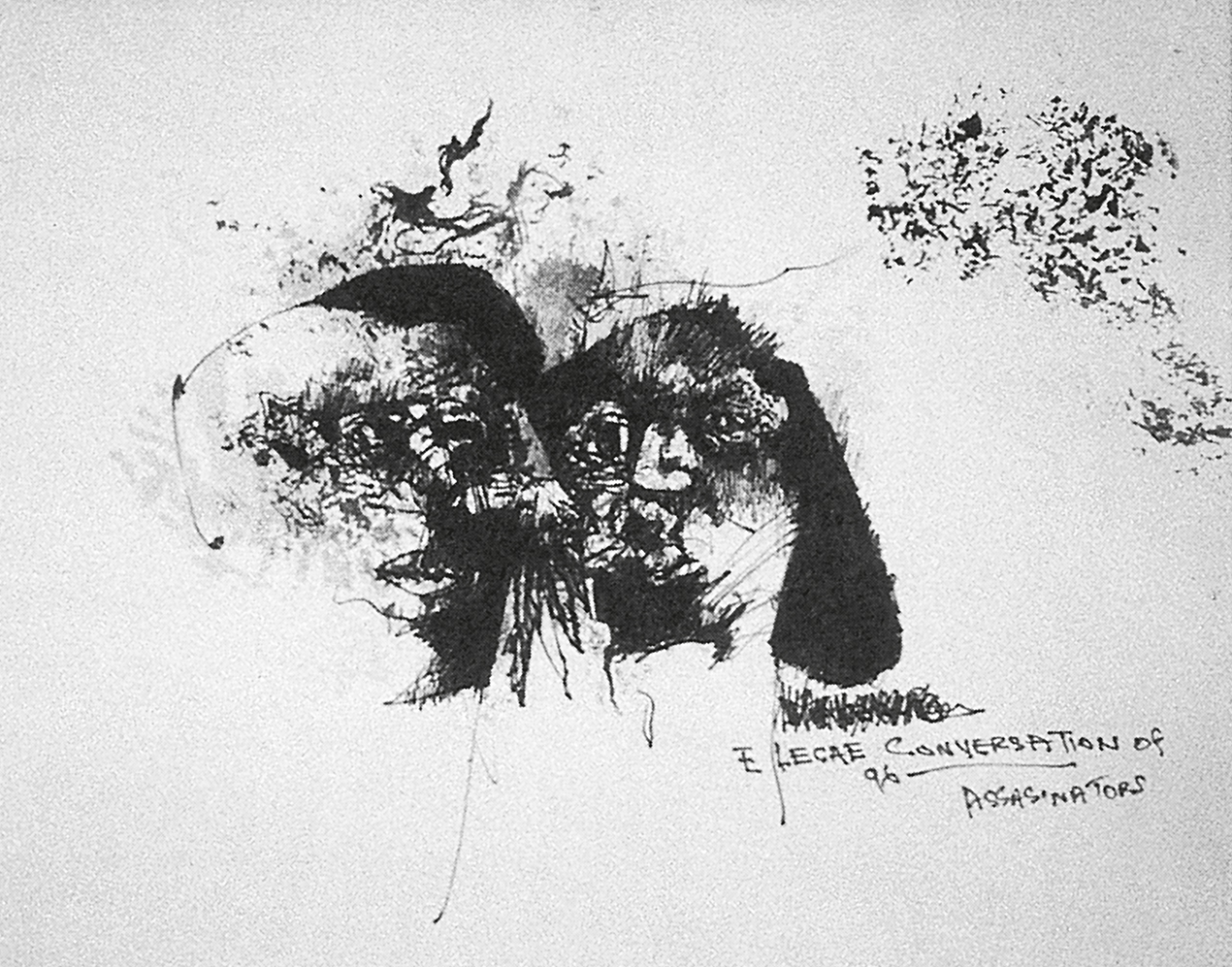

Just as the idea of a clear-cut European hegemony over the early workshops in Osogbo (Nigeria) and Salisbury (Rhodesia) begins to dissolve on closer inspection, so it does at Polly Street. In 1966, Skotnes left to pursue his own work full-time and was replaced by Sydney Kumalo, who had already passed through his classes and was employed as a sports organizer at the centre.[110] Kumalo, the first sculptor to train at Polly Street, was succeeded by Ezrom Legae, another ex-student, in 1968.[111] Technically the centre was no longer ‘Polly Street’, having moved to new premises, but it was perpetuated in a time-honoured African way, through the apprenticeship system in which pupil eventually becomes master. This was a kind of ‘inside brokerage’, no longer fixed in the old white tutor–black learner mould. The fact that, later, the Triangle workshop model could succeed when transformed into the Thupelo Project by David Koloane and Bill Ainslie (like Skotnes, a white artist who taught by example) was due not only to its intrinsic usefulness, but also because its modus operandi was already a familiar and accepted one in South Africa.

110 Sydney Kumalo, Horse, c. 1963–65. Kumalo’s work ranged from fluid semi-abstraction to the massive, quasi-descriptive realism shown here. He was a member of both the Amadlozi group and the Polly Street Centre with Cecil Skotnes.

111 Ezrom Legae, The Assassinator, 1996. Legae, an accomplished sculptor who worked at the Polly Street Centre, is best known outside South Africa for his fine drawings.