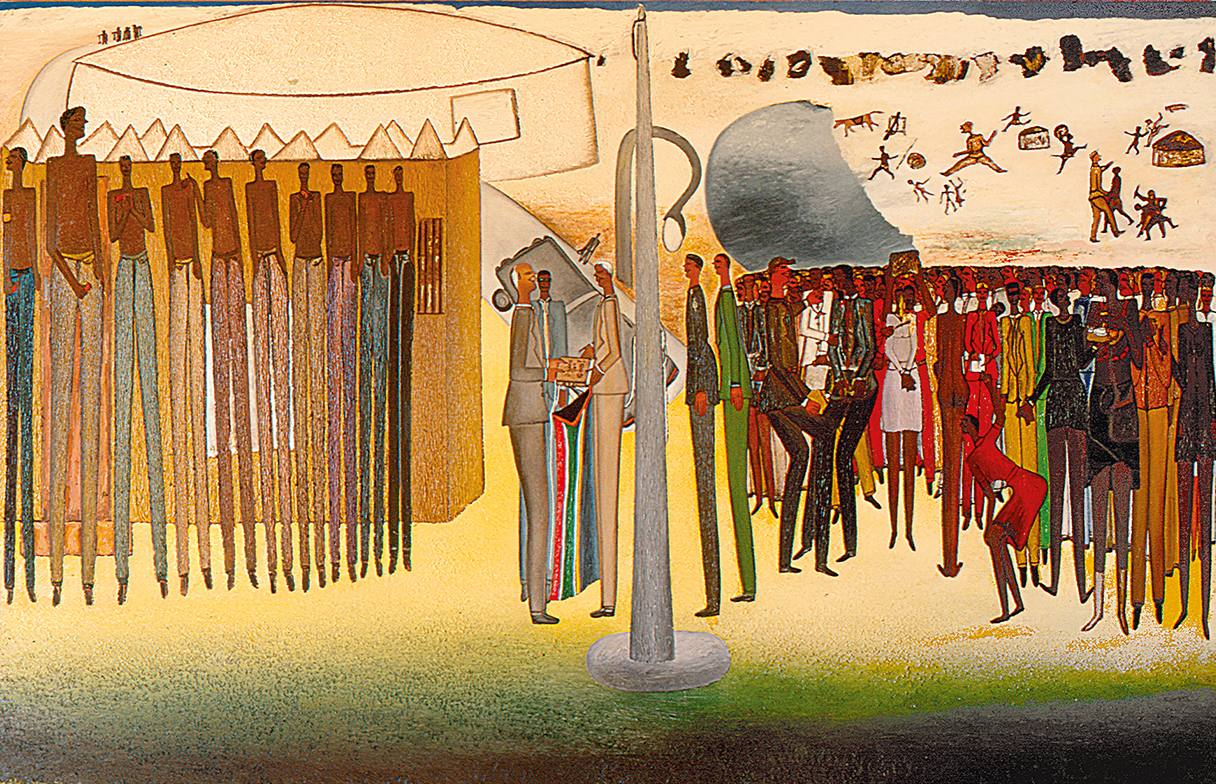

127 Makerere student finalist preparing for painting exhibition, Kampala, Uganda, 1996

The strikingly different attitudes towards the actual process of making among different types of contemporary artists across the African continent reflect not only their modes of training, but also their experience of patronage and the degree to which they are familiar with art and art-making beyond their own communities. There is no simple way to chart or explain all of these differences, but it is possible to make certain important connections. For example, it would be difficult for one of the Weya workshop artists (see Chapter 5) to define herself as an ‘intellectual’, given the fact that in rural Zimbabwean life, intellectualism does not exist as a recognized social category. There even the designation ‘artist’ fits awkwardly with being young and female, although the success of the Weya women has begun to change that assumption locally. On the other hand, colonial education opened up radical new possibilities of self-definition by situating artistic practice in a new relationship to pedagogy. In African countries, as elsewhere, universities are the breeding grounds for the intellectual class, and authoritarian governments fear them, which gives students a much greater sense of their potential and power to effect change than in Western democracies.[127] Where the training of artists is part of the curriculum, they too are caught up in this euphoria of self-invention.

This sense of potential invested in the young and well educated, which in most African states reached its peak in the 1960s, immediately following independence – although it still exists in a more tempered form – has a double-edged significance. It is largely responsible for the vitality and adventurousness seen in the best work by academically trained artists, but because of its connection to a highly developed self-awareness, it also accounts for occasional pretentiousness and self-absorbed rhetoric. Any fair assessment of the role of African artist-intellectuals must take into account the same range of talent and creativity as found among untrained and informally trained artists.

A formal art-school education does two things in addition to the creation of this artistic consciousness: it offers a mastery of techniques that take time, practice and also specialized materials and equipment, and confers some level of familiarity with world art history. These experiences distinguish formally trained artists from their untrained or informally trained counterparts. Taken together, they inculcate both a sense that art-making is a true profession in which one is qualified through a long and demanding course of study, and the Western-derived ideology that to be significant, artworks must place a high premium on originality and uniqueness (unlike either traditional African genres or commodified forms, both of which situate originality within the boundaries of a prototype).

Training, or the lack of it, therefore deeply affects attitudes towards originality or its opposite, emulation. In an apprenticeship there is a pre-existing set of models which the aspiring practitioner must learn to emulate, and it makes little difference whether it is a traditionally organized kin-based workshop or a much larger, modern cooperative. On the other hand, in a short-term workshop in which participants are more or less of equal status, everyone except the organizer is cast into the role of a learner, and replication is usually discouraged as a matter of principle. In art-school instruction, which is more highly structured, more comprehensive and longer term than the workshop, students receive a mixed message – ‘do not slavishly copy’, but on the other hand, in the art history lectures, ‘here is the significant art which has changed the course of history…learn from it.’ Students are encouraged to develop a knowledge base that situates their practice within a wider and longer art history than any workshop or untrained artist usually encounters. In the best schools, this includes African art history as well as European and Asian, which in turn creates its own pedagogic issues: the development of a more pan-African sensibility, but also the tendency to folklorize unfamiliar traditions. Finally, the relation between art-school students and teachers is firmly lodged in African notions of respect for authority which permeate all levels of schooling and reach back into the much older pedagogy of apprenticeship.

127 Makerere student finalist preparing for painting exhibition, Kampala, Uganda, 1996

As young intellectuals, these students also develop an awareness of the postcolonial condition. Some student artists become so mired in the implications of this that they substitute a politicized notion of ‘origins’ for the less certain outcomes of solitary experimentation. One such case was the École de Dakar (see Chapter 7). Others engage in what David Hammond-Tooke, a South African curator, calls ‘highly personal attempts at psychotherapy.’ A few are able to break through this intensive self-consciousness and see beyond themselves, but they constitute quite a small vanguard, working for the most part in isolation or in small experimental settings which resemble either the workshop or the apprenticeship model.[128] Laboratoire AGIT’Art in Senegal exemplifies an egalitarian work site, while Bruce Onobrakpeya’s Ovuomaroro Art Studio and Gallery in Nigeria, with its students and assistants, more closely approximates a master–apprentice model.

By contrast, non-academically trained artists are simply not encumbered in this way: their encounters with Picasso or with contemporary art in far-flung places is haphazard rather than academic. Those who are ‘discovered’ by critics and collectors are often sent abroad to participate in symposia or international exhibitions such as ‘Africa Explores’ in New York in 1991. The scenario in that case is the hoped-for dialogue between authentically ‘naive’ artists and ‘sophisticated’ foreign critics and audience, which frequently, in fact, reveals the sophistication of the artists and naiveté of the critics and audience. Conversely, world art occasionally comes to them, either from books or travelling exhibitions. As we have already seen in Chapter 4, Frank McEwen, the first director of the National Gallery of then-Rhodesia and well connected in the art world from years spent in Paris, arranged for a travelling Picasso show to come to Salisbury in the early 1960s. Thomas Mukarobgwa remembered it well, although he saw Picasso not as one of the great paradigm-shifts in Western art history (since he did not have that kind of academic knowledge) but as a moral exemplar, someone whose worth lies in the fact that he did not copy other artists.[129] Mukarobgwa’s aversion to emulation came from his long membership in the Workshop School, where McEwen’s primary injunction was ‘never copy!’ In a 1996 interview he explained:

Picasso, he was doing a straight thing from his mind. He didn’t used to look in the book anyway. [Artists in Zimbabwe] are now looking at the work of Picasso and trying to do some of those things now. But it won’t work, you see what I mean?…there are quite a number of our children who never grow out in the bush and who never see the natural things in the bush. They’ve grown in the city, became older…without seeing the bush very much….You can see women even now trying to stretch their hair and become white. You can’t compare with someone out in the bush. It’s different. So those kinds of women, one from the bush, one from here [Harare], they do different thing. I think this [imitation of things foreign] is what spoiled the people when they are doing their work.

128 Objects of Performance, Laboratoire AGIT’Art, Dakar, Senegal, 1992

129 Thomas Mukarobgwa with a work in progress, 1996. Mukarobgwa’s practice was based in ‘doing the thing straight from the mind.’

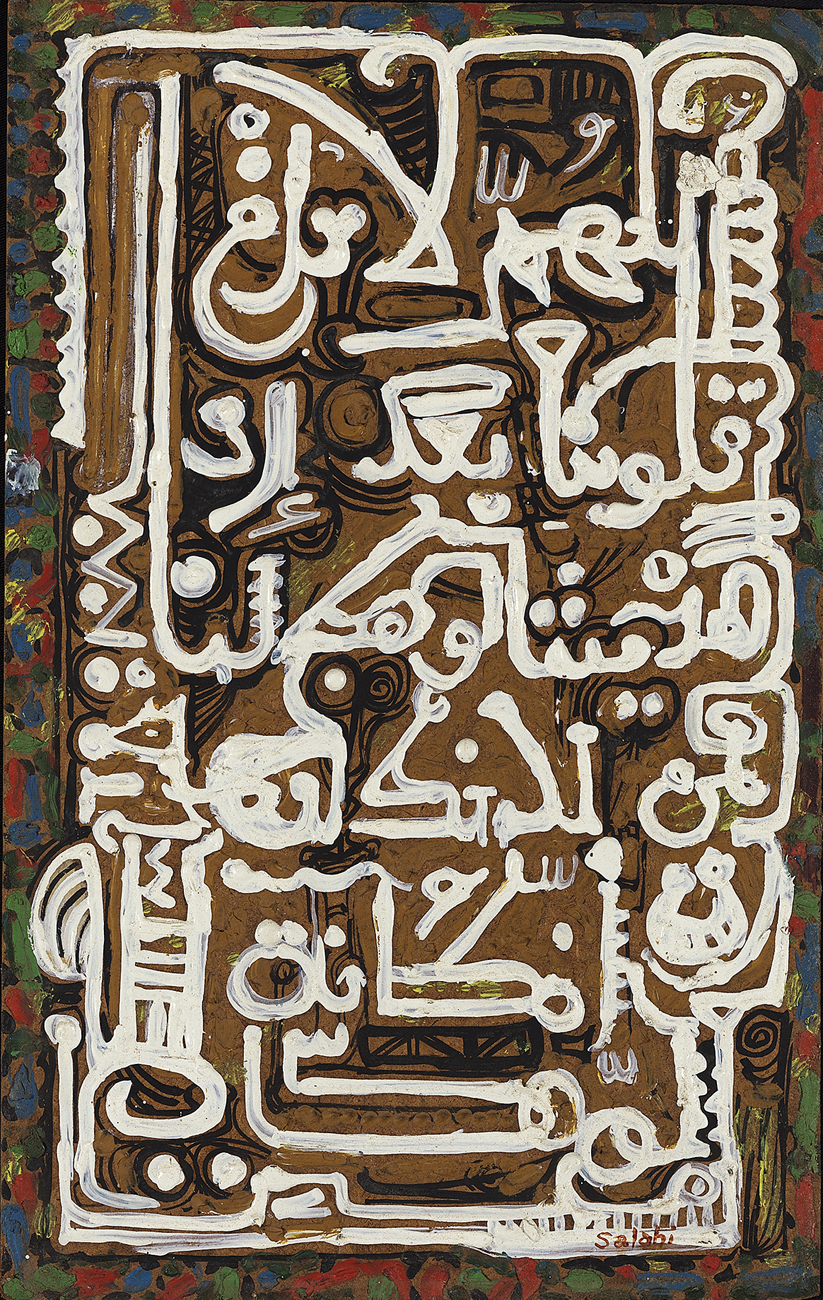

Picasso is an all-encompassing symbol in the minds of many African artists. The Sudanese painter Ibrahim El-Salahi (b. 1930) says that he applied the lesson of Picasso’s Cubism to break apart and reconstitute Sudanese calligraphy. In Senegal in the 1960s, poet-President Léopold Senghor tried to convince artists at the École des Beaux-Arts that Picasso was the best role model for them because he had helped invent modernism while retaining his Andalusian cultural identity. At Makerere Art School in Uganda this mediation has come most recently through the influence of artist-teachers such as Francis Nnaggenda who, trained in Europe, has continued to pose for himself some of the problems raised initially by Picasso and Braque with analytical Cubism.[131] Those issues, now several times removed, were picked up nearly a century later by Nnaggenda’s students and appear in their own work.[132] Given Picasso’s well-publicized receptivity to African sculpture in his early visits to the Musée Trocadéro in Paris, it is especially ironic that the ghostly presence of African forms in the work of a European artist from the early twentieth century should have filtered back into contemporary African art practice by this circular route: from colony to metropole and now back to the postcolony.[130]

130 Kizito Maria Kasule, Painting of the Mother and Child in progress, 1997

131 Francis Nnaggenda, Untitled studio sketch, 1997. Here, Nnaggenda uses the lessons of Cubism to work through, for example, the issue of how to represent the interpenetration of the mother’s gaze with that of her child.

132 Pablo Picasso, Seated Woman, 1927

What this throws into sharp relief is not only the difference between academically trained artists who see themselves as part of an interconnected web of world art and those whose sense of artistic identity is very localized, but also an attitude towards the exemplary which is radically different from the Euro-American one. Far from a mark of weakness, emulation was until very recently a sign of competence – especially in formally structured apprenticeships. And far from there being negative connotations to copying the work of a master, it was, and still is, a worthy form of respect. It was also pragmatic, a solution which was seen to work.

Western notions of originality sit uneasily in such a situation because they require the rejection of African cultural models of how teaching and learning take place. In this sense African practice is culturally much closer to Asian than to contemporary European models. While African art school students do absorb notions of one-of-a-kind originality, these are deposited upon a foundation of early learning that stresses emulation as the proper and natural path towards competence. In an effort to banish such notions, not only art schools, but also workshops run in the 1950s and 1960s by expatriates inculcated the importance of originality and the idea that it was wrong to ‘copy’. Such cases were not just the sanctimonious imposition by expatriates of the tenets of modernism: they became part of a constellation of ideas which African intellectuals themselves promoted. In East Africa, the artist Elimo Njau’s widely quoted dictum became, ‘Copying puts God to Sleep’. But the fact that such declarations were required at all is proof of the problematic nature of emulation.

The attitudes towards selling art further exacerbate the differences in artistic self-consciousness between artists who have been academically trained and those who have not. Artists working in cooperatives have a clear goal when they make something – it is to be sold. Its commodity status is therefore unambiguous at all stages in the creation process, but art school training is a good deal less candid on this point (as it is also in the West). The commodity status of the artwork is clothed in, and even denied by, a rhetoric which says that art is created as an act of self-realization for the artist. What eventually happens to it once it is completed is treated as a secondary issue. At the same time, it is obvious to all students that one of the main measures of success for an artist is the recognition that comes from having their work collected, which is to say, purchased. So the work’s commodity status is simultaneously affirmed and denied. The unsettling nature of this premise was expressed in a discussion between the author and a group of Ugandan artists in 1996. The economic realities of the art market are very difficult to ignore in Uganda, a small country where a large number of formally trained artists have struggled to survive in the aftermath of twenty years of chaos, civil war and the disappearance of art patronage. Yet several of the artists disagreed very fundamentally over whether art had to be market-driven at all.

First artist (an unidentified middle-aged female printmaker):

Today we have to live on art. We have to be able to play the tune. Given your [means of] expression, you have to know what is ‘flying’ on the market…. In the end, you are producing art which is channelled along certain lines.

Second artist (Kizito Maria Kasule, a young male painter and sculptor):[130]

Dealers are saying to us, please do work like this, I want it to be with this approach. If you are the type of person who is one hundred per cent independent in art, you are going to be rejected, you are not going to be ‘advancing’ in art. About the art being produced in Uganda, I can classify it in two categories: there is real art, which you produce with all your heart, you put it in your studio, if someone comes, you negotiate, if he doesn’t give you money [he shrugs], he leaves the work….There’s another category. You produce cheaper work: instead of spending [a long time], you complete it in three days and sell that work cheaply. But this kind of art…is destroying real art.

Patronage also affects the artist’s self-awareness, through the channelling of work by different types of artists into correspondingly different venues for it to be exhibited and sold. According to one criterion, used by both local art establishments in African cities and the average foreigner, work sold in places that call themselves a ‘gallery’, ‘museum’ or ‘cultural centre’ are automatically accorded the status of art. Paintings, batiks, carvings and other media which are sold by hawkers on the street, or by small traders in places like the Blue Market in Nairobi (an entrepreneurial haven of kiosks, which until it was bulldozed by the city council in July 1998 overflowed from the City Market), have a much more uncertain status. Scoured by both the local cognoscenti and tourists looking for ‘finds’, such places operate with very low overheads, correspondingly low prices and no gallery aura. Even serious galleries such as Tuli Fanya and Nommo Gallery in Kampala include a crafts section to help cover costs.

A third kind of postcolonial art venue, the ‘boutique’ (Nigerian pidgin: butik), mediates the gap between gallery and souvenir or craft market. Some, like Cassava Republic in Kampala, Uganda, are artist-entrepreneurs aiming at a tourist market for hand-painted cards, posters and T-shirts. Others, such as African Heritage in Nairobi, Kenya, and Ndoro Traders in Harare, Zimbabwe, are well-capitalized businesses which stock handmade goods ranging from paintings and sculpture to nomadic jewelry, wire toys, baskets and textiles. Nonetheless, they retain the cultural rules of the craft market in which the individual artist’s identity is submerged by an ethnic, group or regional identity.

The work of a university-trained artist such as Kizito Maria Kasule is clearly out of place in the boutique, the city market and, most of all, on the street. Everything such artists have been taught, especially the denial of the commodity status of their work, militates against it being presented to the public as merchandise. The other major obstacle is the anonymity of the artist that customarily accompanies the sale of art in the street or market. The corollary to the conviction that a work of art ought to be original and one-of-a-kind is that its maker ought to be recognized as an individual, not just as a member of a group. Galleries reinforce these convictions and are therefore the only venues that give due respect to trained artists’ own ideas of selfhood and singularity. But there are few galleries in African cities which are not boutiques in disguise. This places trained artists in a difficult position – they either accept the policies and conditions of the local gallery or they resign themselves to exhibiting their work in the houses of friends or, increasingly, in galleries abroad. Those fortunate enough to teach in universities or run their own workshop-studios (such as Bruce Onobrakpeya in Nigeria) develop small circles of disciples and admirers who create the profile needed for direct patronage. However, many trained artists are cut off from the public by the scarcity of acceptable exhibition spaces, which makes them a beleaguered, if privileged, minority.

133 Adebisi Fabunmi, The Birth of Osogbo, 1977. Fabunmi emerged as a highly original printmaker in the 1964 Osogbo workshop, and began to experiment with yarn in the late 1960s.

Those who are workshop-trained, especially in Nigeria, have seemingly blurred the differences between themselves and academically trained artists by both their critical and their financial success on the international art circuit. But for many years the Nigerian cultural bureaucracy denied them that recognition. During the planning for FESTAC, the Second International Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture held in 1977 in Lagos and throughout the country, there was an attempt (later overruled) to exclude workshop artists altogether. The festival was supposed to highlight Nigeria’s official commitment to the arts, but workshop artists found themselves left out of the bureaucratic vision of ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’ art exhibitions, the former consisting of the treasures of the National Museums in Jos and Lagos, and the latter of the work of art-school-trained artists.

134 Yinka Adeyemi, Baboon Hunter and Magical Antelope, 1977. Adeyemi was traned in batik by Susanne Wenger. Though he did not participate in the Osogbo workshops, his work shows a similarly fantastical setting for the encounter between humans and spirit creatures.

The apparent invisibility of artists such as Adebisi Fabunmi, Yinka Adeyemi and Jimoh Buraimoh, despite their by-then international recognition through the Osogbo workshops a decade earlier, exposed the sharp divides between the official and unofficial versions of Nigerian art.[133] In the government’s vision of art in the late 1970s, the minds of cultural bureaucrats were still comfortably focused on the seemingly sharp and irresolvable contrast between tradition and modernity, the dominant cultural paradigm of the early 1960s when they had been students themselves.[134]

This ‘two worlds’ approach is echoed in numerous writings of the pre- and early independence period, from R. Mugo Gatheru’s Child of Two Worlds (1964) and Camara Laye’s L’Enfant Noir (1953) to Chinua Achebe’s great novels Arrow of God (1964) and Things Fall Apart (1958). Because workshop artists of this period were not educated elites, and in the two-worlds model of African culture ‘modern’ certainly meant educated, they did not seem to be essential players in this dialectic of progress. But in the 1980s and 1990s, ironically, it was precisely these artists who came to seem most representative of contemporary artistic practice.

In this reversal of fashion, a considerable number of French, German and Italian critics, galleries, museums and collectors who publish and exhibit contemporary African art were increasingly disposed to bypass the work of trained artists in favour of that by practitioners without diplomas and degrees. As early as 1968, Ulli Beier’s seminal Contemporary Art in Africa devoted less than one-fifth of its text to formally trained artists and pointed out the derivative nature of much of their work and the inherent problem in introducing Western models. André Magnin and Jacques Soulillou’s Contemporary Art of Africa, published nearly thirty years later in 1996, selected artists to be discussed according to this same criterion. Of the sixty-odd artists included, nearly all were trained through apprenticeships, workshops or by self-experimentation.[135] A handful, such as the Vohou-Vohou painters of Côte d’Ivoire or the well-known Senegalese artist-activist Issa Samb (1945–2017), are included as examples of artists in rebellion against their original academic training. The authors make their position on this point clear:

Many artists formed in the schools of art, where they acquired a solid background in modern art of the West…produce work that all too often stays well within the realm of that tradition….For them, the field of art basically remains confined to technical issues and begs the more fundamental question of the purpose of that technique….Such recourse to these characteristic styles and techniques of Western modern art inevitably favours a hybridization…ceaselessly fuelled by its sources. Unhappily, such a fuzzy aesthetic in which confusion reigns, which refuses to strike out in unknown territory, runs the risk of being fatal to art.

The attack on hybridity seems somewhat misplaced in this context – it is the very fact of its hybridization and a ‘fuzzy aesthetic’ that gives much of the work of untrained artists its emergent quality and thus makes it interesting to critics such as Magnin and Soulillou.

135 Théodore Koudougnon, Beads, 1988. Koudougnon was one of the Vohou-Vohou artists, whose rebellion had a distinctly francophone feel – issuing manifestoes invoking African identity while simultaneously making fun of the writing of manifestoes.

As the Cuban critic Gerardo Mosquera has noted, instead of colonizing the Third World, the West now sends curators as postcolonial explorers on ‘voyages of discovery’. To extend his metaphor, collectors are then a kind of advance-guard, scouting the territory and trading with the natives before any treaties are signed. The first major travelling exhibition of contemporary African art, ‘Kunst Aus Afrika’ (1979), exhibited the private collection of Gunter Peus and featured (though not exclusively) the work of untrained artists from the young Chéri Samba to Middle Art (see Chapter 1). The same was true of the travelling show ‘Africa Hoy!’ (1991), which was based on the collection of Jean Pigozzi. This encyclopaedic and highly visible collection also provided all but a few of the artworks in Magnin and Soulillou’s Contemporary Art of Africa and many of the examples for this book. The tastes and preferences of a handful of private collectors and the curators who work closely with them have had a great influence on the way in which contemporary African art is defined for its various publics – ‘autodidacts’ are privileged over formally trained artists, women artists are nearly invisible, and with the exception of South Africa (which has its own corps of curators and critics), the anglophone countries are severely underrepresented relative to their artistic importance.

Two important exhibitions of contemporary African art that were shown as part of the ‘Africa ’95’ festival in London illustrated both this set of emerging preferences and a major attempt to challenge them. In the Serpentine Gallery’s ‘Big City’, which was also based on the Pigozzi collection and curated by André Magnin, the dominant themes were enigma and fantasy – as in Kimbéville, the imaginary cardboard city and icon to modernity built by the Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez (1948–2015). Five of the six artists then appeared in Magnin and Soulillou’s survey.[136] Taking a very different stance, the Whitechapel Art Gallery’s more inclusive project ‘Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa’ presented the work of academically trained, workshop and untrained artists, and gave anglophone Africa long overdue attention, as well as women artists and curators a voice. Part of its ambition stemmed from the organizer Clémentine Deliss’s desire to have a group of African curators and contributors for the show who would also write and organize texts for the catalogue. Some contributors (Everlyn Nicodemus, El Hadji Sy, David Koloane and Chika Okeke) were also practising artists, others (Wanjiku Nyachae and Salah Hassan, as well as Clémentine Deliss herself) were closely involved with contemporary art, working as curators or critics. As the Whitechapel’s director Catherine Lampert put it:

Gradually, the romantic authenticity automatically associated with the ‘untrained’ artist has become an exhausted assumption, except in the media and among some collectors. Indeed the curators and galleries participating in this exhibition have chosen an approach that welcomes educated and intellectually rigorous thinking and acknowledges African art as being cosmopolitan while at the same time its content may abound in local and personal references.

The overall effectiveness of ‘Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa’ (some of the ‘stories’ more compelling than others) restored both French- and English-speaking artist-intellectuals to the contemporary art discourse.

This statement, made in an interview by the American poet laureate Robert Pinsky, expresses not only the observation that the work of every artist is in part conceived out of the work of other artists either past or current, but also the conviction that it ought to be that way. It is a powerful idea considered axiomatic by most art historians and critics. But what is perhaps overlooked by its otherwise compelling simplicity is the political force its meaning has in a colonial context. A palpable tension between identity and pedagogy developed along with the independence movement in many late-colonial states. One of the results of this tension has been the ‘schizophrenia in the arts’ described by another poet, Chinweizu, writing about intellectual life in the Nigeria of the 1970s. African artists and writers, composers and filmmakers have wanted both to break onto a world stage, to assert that Africa is a player and not simply a peripheral audience, and at the same time have wanted to express an identity which is not only ‘not European’ but is both African and anticolonial. This has led to a dilemma driven by both the uncertainties of postcolonial identity and an equally uncertain role played by colonial-style education. In its simplest form, expressed in the 1960s, it was the child-of-two-worlds argument about the conflict between tradition and modernity, Africa and the West. Since that time, these terms have been substantially criticized and redefined, and in the mind of a self-reflexive artist such as the Sudanese Ibrahim El-Salahi, what is old or new, African or Islamic or modern, do not exist as free choices, but as partly intentional and partly predetermined.[137-139] In a Third Text interview with Ulli Beier, El-Salahi revealed that he often felt caught between two elements in his work – one over which he has no control; which simply appears unbidden in his work and which he recognizes as the same images t hat used to appear to him as a child in Khartoum, and the other which he consciously tries to impose as a trained artist with an arsenal of imagery and techniques at his disposal.

UB: How then does the Sudanese element fuse with your Qatar or English experience?

IE-S: Well, the Sudanese experiences are in the images. As a child I had images of people. They appeared and I saw them physically. The things I draw are not imagined; they appear in front of my eyes….Sometimes, like a fraction of a second, the horizon opens and I see them….I work like a medium, so my imagery is not something I think about. I do not create them, they create themselves. When I came to England, I learned two things: I learned about techniques, and I learned about the people. I was keen to acquire the tools of painting….But I was also anxious to know about…the background of the Renaissance, about early Christian painting, the contemporary movements….When I went to live in the Arab world my experience linked again with my early childhood. Arab culture is linked with the Arab language, with the Koran and calligraphy. And calligraphy is a most important subject for me, because it is abstracted form, with symbols which carry sound and meaning. First, I used to write calligraphy as it is: poetry or words of wisdom. But later on, I applied some of the techniques I had learned in Europe. I like what Picasso had done with Cubism, taking the visual form and breaking it into it original components, and then reconstructing it in a new form. I think I did the same thing with calligraphy….I tried to go deeper and break [down] the actual shape of the symbol to its origin – to take it back to animal forms, or water….And once I opened this door and went through it, it was like breaking glass! I had to walk carefully: sometimes you could cut yourself….I was breaking and breaking…and figures appeared…the same figures or spirits that used to come to me as a child! They came to me when they were freed of the rigid form of the letter.

UB: …These images were strikingly African. You could almost have thought they had emerged from some culture in the Ivory Coast. There was this extraordinary affinity: maybe there is some deep layer of consciousness that reaches out way beyond its narrow geographical location….

IE-S: That is quite true. At first I was just taken in by them. I couldn’t even think about it, because they wanted to come out and I brought them out; and they kept coming and coming….Later I used to think: here I am, thinking of myself as an Arab, but these do look like African masks! How come? I am trying to refine my calligraphy and these kinds of images emerge!….This can cause a dilemma, this process of wedding what flows from within with what you have acquired from outside. How to weigh the two elements, which may be quite contradictory with each other, that is the nature of the work. Because ideas are ideas, not art. Art is what you make of the ideas.

UB: …Could you say that this image that appears, uncontrolled and unsolicited, is really some kind of archaic identity, and that the intellectual process then finds some common denominator between it and all the other acquired identities?

IE-S: Yes. Let us say that the work of art is the meeting point.

Finally, what is most interesting here is that both El-Salahi and Beier were intellectually ‘formed’ in the 1950s and 1960s, and that consequently both artist and critic see the unbidden element as a kind of African essence which refuses to be completely controlled by outside forces. It is part of a larger argument about the existence of primordial identities, which a younger generation would view with a certain scepticism.

136 Bodys Isek Kingelez, Kibembele Ihunga (Kimbéville) (detail), 1993–94

137 Ibrahim El-Salahi, Calligraphy, n.d.

138 Ibrahim El-Salahi, Self-portrait of Suffering, 1961

139 Ibrahim El-Salahi, Faces, early 1960s

It is also possible to follow this dialectic of the inner and outer consciousness as it was played out in the education of those African artists who did not go to Europe to be trained. Nowhere can this rhetoric be traced more clearly than in the development of one of the continent’s major art schools at Makerere University in pre- and post-independence Uganda. Margaret Trowell, its founder, represented a colonial pedagogy which grew out of British Colonial Office notions of native perfectibility and progress. As a governing strategy, Indirect Rule had adhered to the principle of least interference with existing tradition. In like manner, Trowell advised, ‘We start from it, study it, and honour it.’ Her instincts were therefore to build upon the artisanal practices which already existed, but to introduce new technical knowledge as a pragmatic way to ‘develop’ the visual arts in a region of Africa where representational art was rare.

140 Peter Mulindwa, The Owl Drums Death, 1982. An example of classic Makerere work, in which mythology carries both a pictorial and narrative load. The Ugandan Martyrs died at the order of a despotic kabaka (king), and so have also come to symbolize those who have been martyred by modern despots.

Trowell’s teaching strategy was a conscious rejection of the model put forward by European modernism, and set Makerere on a course which, while later redirected, earned it an early reputation among outsiders as an old-fashioned late-colonial institution. Uganda is not even mentioned in Ulli Beier’s text of 1968, although Makerere was well established by that time as the major centre for training artists from a wide region of eastern Africa, from the Sudan to Rhodesia. Trained as an artist at the Slade, London, and as an art teacher at the Institute of Education at the University of London, Trowell introduced her students to Western techniques such as easel painting and silkscreen printing. Within these pictorial genres she encouraged the use of narrative, which until then had resided mainly in oral tradition. The pictorial narrative, which was rare prior to 1900 aside from prehistoric rock art, has become a staple of representation in African art almost everywhere, from the heroic exploits of the gods to the struggles of everyday life and chilling allegories of military rule.[142] Sculpture, while unable to carry the same complex narrative load as painting, could thematize both mythic and genre subjects.[140] Trowell’s most outstanding early student, the Kenyan Gregory Maloba, developed a powerful monumental style using Ugandan hardwoods and other materials, and assisted Trowell as an instructor at Makerere during the 1950s, later returning to Kenya to head the Department of Design at the fledgling University of Nairobi.[141]

141 Gregory Maloba, Death, c. 1940

In the early period, the first East African artist to be exhibited abroad was the Tanzanian Sam Ntiro. His career as a painter and Maloba’s career as a sculptor were both initially promoted by Trowell.[143] Their trajectories were in many ways parallel to Ben Enwonwu’s in Nigeria; Enwonwu’s career had been encouraged by the legendary Kenneth Murray.[144] As expatriate art teachers, both Murray and Trowell had insisted on grounding their students in their own local systems of knowledge and artistic practice – a deep interest in preserving these traditions led Murray to become Nigeria’s first Director of Antiquities and to collect both objects and ethnographic documentation for the Lagos Museum.

Trowell was director of the Uganda Museum (1939–45) when she initiated art classes at Makerere, and she later wrote two influential studies, Classical African Sculpture (1954) and African Design (1960). Both Murray and Trowell also arranged for their most promising students’ work to be shown in London – Trowell’s students at the Imperial Institute in 1939 and Murray’s at the Zwemmer Gallery in 1937. They sent their best students on to the Slade School of Fine Art or the Royal Academy of Arts in London for further training. But paradoxically this assured that these early students would take on larger-than-life reputations as archetypes of the ‘modern African artist’ in the minds of the British public as well as at home in the colonies. They were expected to epitomize the educated colonial elite, but also to represent an essential ‘Africanness’.

If Trowell represented a traditionalizing approach common to the projects of the 1950s, her South African successor Cecil Todd was fully committed to an African modernism based on a knowledge of twentieth-century developments in Europe as well as canonical African art. Students were given a thorough training in world art history, scientific colour theory and life drawing. Like Trowell, Todd insisted on students achieving a high level of technical skill and making use of indigenous materials. As a white South African, he shared some of the same goals in training young African artists as his counterpart Cecil Skotnes had at the Polly Street Centre in Johannesburg a few years earlier. But whereas in South Africa the early Polly Street artists – Durant Sihlali and Lucas Sithole, among others – were not encouraged to learn about styles and movements elsewhere, Todd and his staff sought to make Makerere students conversant with a wide range of world art. Ironically, while Todd’s position was considered a neocolonialist one in the 1960s, in the 1990s it was reinterpreted by many younger African artists as a form of enlightened ‘internationalism’. If early South African attempts to avoid ‘contaminating’ artists with Western ideas now seems paternalistic and short-sighted, this shifting of values among the emerging generation of artists and critics is partly the result of their greater likelihood to exhibit, publish and live abroad.

142 Shangodare, The Triumphant Return of Shango from Battle, 1977. Unlike Mulindwa’s piece (140) this work does not draw parallels with contemporary events but acts as a validation of Oyo Yoruba culture’s mythic past – here, Shango, the god of thunder and lightning, is shown.

143 Gregory Maloba teaching at Makerere Arts School, Uganda, 1950s.

144 Ben Enonwu in his London studio, 1957. The West African Review captioned this photo ‘Enonwu the Bohemian’ and remarked ‘Apart from the telephone at his elbow, this could be a garret in 19th-century Paris.’

The Makerere of the 1960s, caught up in the intellectual euphoria of nationalism and anticolonialism, was very different from either the late-colonial Makerere of Trowell or the postcolonial internationalism of today. Todd was unwilling to condone student radicalism that rejected British pedagogy, symbolized in the University (though not the Art School) through the official subordination of Makerere’s degree-granting status to the University of London at that time. While the intellectual debate was usually couched in terms of African literature and the importance of teaching the work of African writers along with Shakespeare, it also spilled over into art and music.

Three young artists whose ideas Todd opposed were the Ugandan painter Eli Kyeyune and the Tanzanians Sam Ntiro and Elimo Njau.[146] Njau, an outspoken and charismatic artist who had been trained by Trowell herself and graduated in the first diploma class, was not invited by Todd to teach in the Art School, and Kyeyune, who later won an international artists’ competition sponsored by the then-fledgling journal African Arts, left without finishing his degree to follow Njau to Nairobi. There, Njau set up Paa ya Paa (‘the antelope rises’) Arts & Cultural Centre, which despite an inadequate staff and operating budget managed to survive over the years with a changing clientele of visiting artists, tourists and international student groups until it was tragically destroyed by a fire in December 1997. It partly reopened with the help of local and donor support only a year later, and is now fully rebuilt.

Ntiro had been Trowell’s protégé, and after completing further training at the Slade in London, he returned to the Makerere Art School but was dismissed by Todd, at which point he went back to Tanzania and became a commissioner for culture in the socialist government of Julius Nyerere. Todd was assisted by a teaching staff of extraordinary younger (and predictably more iconoclastic) artists including Ali Darwish (Zanzibar), Jonathan Kingdon (Tanzania) and Michael Adams (UK), all with burgeoning careers of their own.[145] For all of these artists, as well as their protégés among the students, the Nommo Gallery in Kampala provided necessary access to patrons and audience. Adams and Kingdon were also responsible for teaching printmaking after hours to the Art School’s custodian Richard Ndabagoye, who proved to be a more formidable talent than most of the students and held a one-man show at the Nommo Gallery – though he was imprisoned shortly after and his career cut short.[147]

145 Michael Adams, View from Fazal Abdullah’s Mother’s House, Lamu, c. 1966

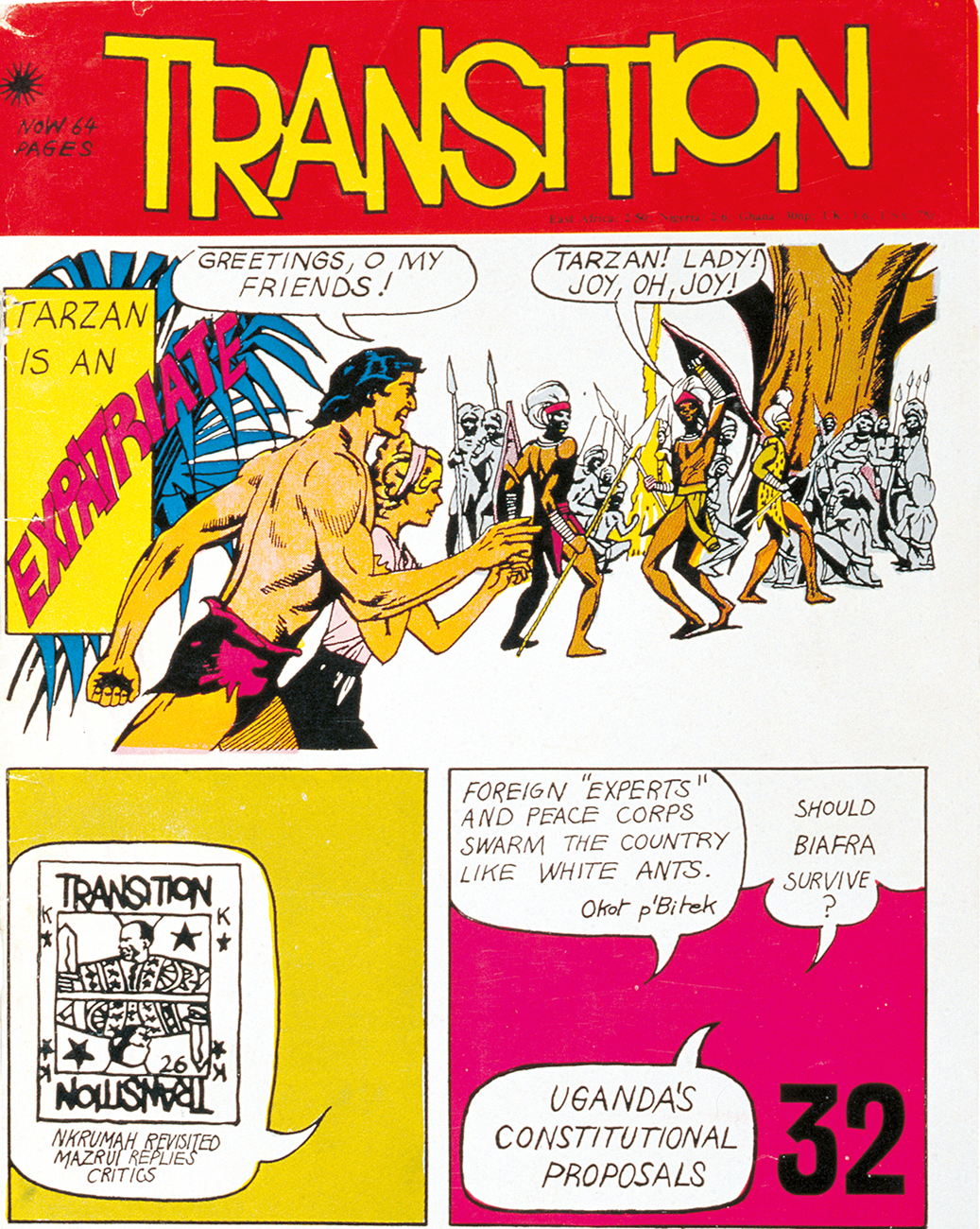

Todd’s major project was the construction of a gallery at the School to house the permanent collection of works by staff and students, funded by the politically conservative Gulbenkian Foundation. This, too, drove a wedge between him and the group of radical East African intellectuals who were setting the terms of the first discussions about postcoloniality. Many of these debates took place in the pages of Transition magazine, the literary and political journal founded by Rajat Neogy in Kampala in 1961 and supported by the same group of artists, writers and intellectuals who founded the Nommo Gallery and directed such projects as the National Theatre and the national dance troupe ‘Heartbeat of Africa’.[148]

146 Elimo Njau, Milking, 1972

147 Richard Ndabagoye, Mume na Mke (Husband and Wife), 1969. The contrast between elderly husband and young, inscrutable wife has much to say about arranged marriages. Their stiff, hieratic pose is reminiscent of subjects posing for a photographer.

Unlike Nigeria, South Africa or Congo, Uganda is a small country with a single intellectual centre, Kampala. Every artist, poet, playwright, novelist, gallery director, newspaper journalist and public intellectual knows one another, creating a high level of cross-fertilization in the arts. In Paul Theroux’s words it was a ‘small green city…full of distinguished people’. But while writers’ work could be published and sold abroad, visual artists were dependent primarily on local patronage by elites and the government. This evaporated with the coup d’etat of 1971, which brought Idi Amin to power. Within a short time, all public criticism was stifled, and artists and intellectuals who survived – some did not – either went into exile or tried, like other Ugandans, to live by their wits. One effect of the Amin regime was to force the departure of expatriates, as well as politically outspoken Ugandans, from the University. As more and more Ugandans, including the University’s own vice chancellor, ‘disappeared’ into Makindye or Luzira prison, never to be seen again, Makerere struggled to stay open by employing its own recent BA graduates as teachers; ironically, as a result this reign of terror became a time of opportunity for some young artists, particularly if they were able to turn out commissions for the regime. One of the artists who narrowly escaped imprisonment was the Ugandan sculptor Francis Nnaggenda, whose large-scale sculptures in wood and metal explore the ‘machine in the garden’ metaphor, as well as the resilience of the human body and spirit under the assault of war, violence and technology.[149]

Today internationalism is in the air once again, which worries some of the older artists who have lived through each of these phases in turn. Nnaggenda, who generally supports the international curriculum, also sees it as a process which inevitably erodes African systems of knowledge.

FN: Today you’ll find a young fellow, when you talk to him in Luganda, he will tell you that I don’t understand what you’re saying, please speak in English…even you may say a certain proverb and he has never heard of it.

SLK: Are you suggesting that there is now such a distance for this person from his own culture that he approaches it from the outside looking in?

FN: Exactly. It is true…these students who are here, they should learn about Yorubas, they should learn about Asantes, they should learn about Dogons, because when the Dogons talk, although we are distant here on the continent, I’ve come to realize that when you look at the core, we are the same, we are the same…if we can’t learn from ourselves then we become, how do you call it, thin.

148 Michael Adams, cover for Transition 32, 1967. Here Adams has illustrated Paul Theroux’s lead article, ‘Tarzan is an Expatriate’. Transition flourished in Uganda until the government accused its founder of treason. It moved to Ghana under the editorship of Wole Soyinka but did not do well in West Africa; since 1991 it has been published as a diasporic journal, edited in the USA.

149 Francis Nnaggenda with an untitled sculpture, Makerere

A parallel set of pedagogic debates took place at the same time in Nigeria, first in what was to become the Fine Art Department at Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, and then at the University of Nigeria at Nsukka (see Chapter 7). In each of these countries – Sudan, Uganda, Nigeria – the actors and scenery changed, but the cultural script remained the same – how did one continue to be African and still be a modern artist? It was the burning question of the 1960s among artists across much of the continent. It is still salient for many artists who came of age during that period, and is belatedly being played out in South Africa today, tied as it is to issues of cultural nationalism. But to even ask this question is to betray one’s psychological distance from what Thomas Mukarobgwa referred to simply as ‘the bush’ – it is an intellectual’s question.

150 Dossou Amidou, Yoruba (Nago) Gelede mask, Benin, n.d.

151 Efiaimbelo, One is Never Better Served than by Oneself, Mahafaly aloalo (funerary post), Madagascar, 1994

It would be wrong, however, to locate the issue of artistic consciousness solely in those who have studied art in universities and art academies. It requires an awareness borne out of an engagement between self and world, and the postcolonial condition encourages this on a regular basis – particularly through museums and their curators, which not only influence the way that artists such as Frédéric Bruly Bouabré (1923–2014) and Georges Adéagbo (b. 1942) work, but are also active agents themselves in constructing postcoloniality.[152] By juxtaposing the work of international artists in a shared space, the curators of ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, for instance, suggested shared intentions between artists, whether a Navajo sand painter, a carver of Gelede masks from Benin, a maker of funerary markers from Madagascar or a conceptual artist from New York.[150] Their side-by-side exposure conveys, promotes and mediates the claim for some common intelligence or consciousness.[151]

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré was a government official in Côte d’Ivoire who worked for the French Institute for Subsaharan Africa (IFAN). The IFAN Museum was housed in the same building in Abidjan and although it was smaller than the one in Dakar it was nonetheless a major presence. Bouabré explained in a 1995 interview about the ‘Big City’ exhibition featuring his work that he loved museums in the way that one might love old books. ‘I do not work from my imagination. I observe, and what I see delights me. And so I want to imitate.’ This imitation, despite Bouabré’s own declaration, was highly imaginative, yet meticulously controlled.

The archaeology of knowledge wrapped inside objects, performances and their interpretation, which we call history, has also been a preoccupation for Georges Adéagbo of the Republic of Benin. Initially trained in law and political science in France, he returned to Cotonou, his birthplace, in 1971, where he began constructing installations in the sandy courtyard of his compound. Of necessity the components, which included such things as newspapers held down by stones, dolls’ heads, deflated soccer balls and objects from vodou altars (these from the installation he called ‘Histoire de France’ in 1992) had to be laid out horizontally on the ground. Later, when he became recognized and exhibited in galleries, he could add a vertical dimension by covering the walls too.[154]

Throughout a long career he has remained remarkably consistent with this exhibition format, though the actual contents are always fresh. In the 11th Shanghai Biennial in 2016 he created an installation called La révolution et les revolutions.[153] Two of the many components were the inner portion of a red Egun costume tacked to the wall and an old chair holding a small statuette of the deified general Guan Yu who died in 220 CE. Both chair and statue came from a Shanghai antique shop, where they were displayed together. But the artist cautions that meaning in all his objects lies in their interaction with each other and not individually. His curatorial and logistics advisor Stephan Köhler at Kulturforum Sud-Nord refers to them as ‘laboratories of encounters.’

152 Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Knowledge of the World – in the Bowels of the Verdant Earth, the Subterranean Blue Sea Washes Our ‘Dead’ Before Being Reborn as Drinking Water, 1991

Postcoloniality in what had been French West Africa has had several generations to sink into people’s consciousness. But in South Africa it was only achieved in 1994 after the first free elections. The period between the 1976 Soweto Uprising and the elections can be seen as a time of intense self-examination by artists and writers searching for a viable way to be South African and also part of the world. Artistic consciousness has therefore been a constant symptom of South Africa’s social fragmentation, both for white artists conditioned by their professional training to think in terms of self-realization, and for their black and other non-white counterparts because they moved within a society officially closed to their representations.

153 Georges Adéagbo finding items for his installation La révolution et les révolutions (The revolution and the revolutions), August 2016

154 Georges Adéagbo, general view of room installation with Chinese figure on chair and Egun costume on wall, 11th Shanghai Biennial, 2016

While there was a spectrum of possible alliances, both artistic and critical practice during the 1970s and 1980s responded to the African National Congress’s Leninist-derived position that artists were ‘cultural workers’ who ought to be engaged in actively resisting an oppressive regime. Few artists or even critics were so explicitly doctrinaire, but there was nonetheless a clear recognition that the discourse about race was at the heart of the ANC’s goal of a ‘non-racial society’, which, in turn, made it the recurrent theme of most art, whether by black or white artists. For the latter this forced upon them the contradiction between their professed political ideals and their privileged socio-economic position.

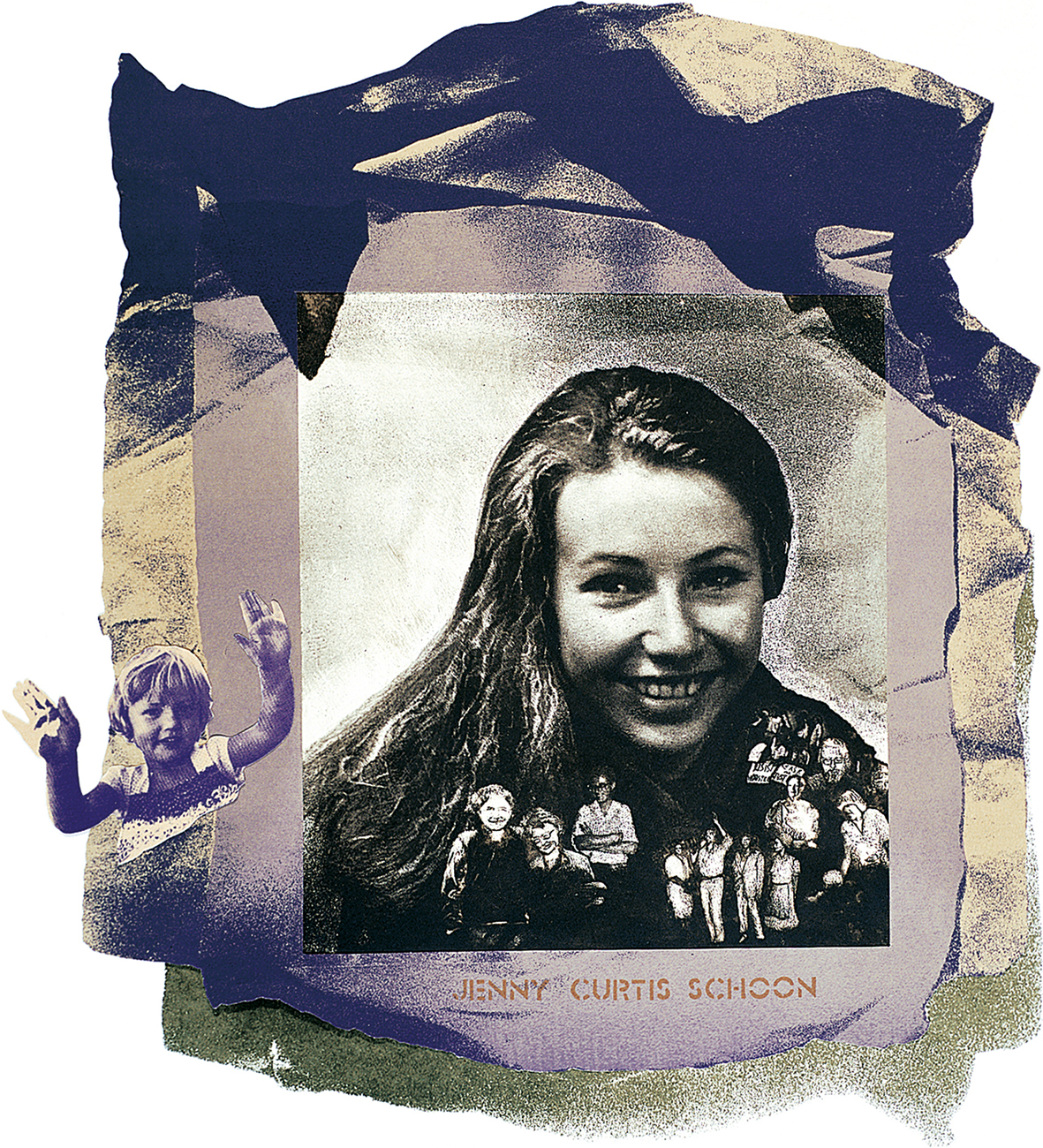

The response of some white artists was to incorporate their activism into the explicit content of their work. In 1982, Sue Williamson (b. 1941) began a series of screen-printed photographic collages honouring women involved in the apartheid struggle. Most of these were black women such as Annie Silinga (1910–1984), involved in the Defiance Campaign of the 1950s, and Mamphela Ramphele (b. 1947), one of South Africa’s leading public intellectuals, who as a medical student had been an activist in the black consciousness movement with Steve Biko.[155] Also included were Jenny Curtis Schoon, a young white political activist who died in 1984 when she and her small daughter were blown up by a parcel bomb.

William Kentridge’s (b. 1955) sensibility has been closely tempered by the city of Johannesburg, where he has always lived. In 1990 he wrote, ‘In the end all the work I do is about Johannesburg, a rather desperate provincial city. I have never tried to make illustrations of apartheid, but the drawings are certainly spawned by and feed off the brutalized society left in its wake. I am interested in a political art, that is to say an art of ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures and uncertain endings. An art [and a politics] in which my optimism is kept in check and my nihilism at bay.’ Kentridge began to combine drawing with animation in the 1980s. The government had declared a state of emergency in 1985 and imposed press censorship, resulting in newspapers with blank spaces where stories had been expunged. Expanding on this idea, he created his own version:

The film was made in my studio on one sheet of paper. It chronicles a history of images, events, people, and interactions, all of which are subsequently erased leaving a blank, but bruised sheet of paper. The sheet of drawing paper was exhibited…with the film projected alongside….Subsequently, even blank spaces in newspapers were deemed to be subversive and prohibited.

155 Sue Williamson, A Few South Africans: Jenny Curtis Schoon, 1985

Kentridge initiated a six-film series in 1989, beginning with Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris. Another was Sobriety, Obesity and Getting Old (1991).[156] A recurrent image in the drawings for these works was an empty advertising billboard, set in a burnt-out landscape that held traces of what had happened there, a powerful symbol also deployed by artists such as Jane Alexander (b. 1959).[163]

Penny Siopis (b. 1953), an introspective painter concerned with the large themes of history, has described her use of images of opulence – satin drapery, flowers, food – in the mid-1980s as a way of commenting upon the decadence of white South African society.[157] Tiny figures and whole narratives are embedded almost microscopically in larger ones, creating an account that is baroque in its detail. They are rhetorical and require close reading – not an art for a broad public but one encrypted with meanings from literature, psychoanalytic theory and more localized South African history.

156 William Kentridge, Soho and Mrs Eckstein in the Landscape, for Sobriety, Obesity and Getting Old, 1991. Soho Eckstein was an ageing mining magnate and property developer, pictured here with his neglected wife in a landscape showing traces of what has been visited upon it.

The issue of consciousness worked in reverse for non-white artists under apartheid: as the subjects of constant government surveillance they were always at risk of arrest and imprisonment, but as the disenfranchised they were impelled to find ways of expressing a political voice. Their art-making was therefore always carried out in a state of intellectual tension. When Alfred Thoba (b. 1951) painted the obviously political Race Riots (1977), he had to move it with him from place to place because it was incriminating evidence.[158] Willie Bester (b. 1965) is one of many artists who occupy an intermediate position between the overly stereotyped polarities of the white, formally schooled artist with literary-philosophical leanings and the black, informally trained artist who depicts the reality of life under an apartheid regime.[160] Designated ‘coloured’ in South African official parlance, he grew up in Montague, a section of Cape Town, but was ‘removed’ under the Group Areas Act that segregated residential areas. His formal instruction was minimal – he spent a year at CAP (Community Arts Project), the major training centre for non-white artists in Cape Town. Although his subject is township life, he is far less literal and more inclined towards layers of interpretation than either the earlier ‘township artists’ of the 1960s or the CAP poster artists working in the ‘straight resistance mode’. Bester employs the detritus of the street along with oil or watercolour in a collage-like format augmented by minute calligraphic figures and symbols.

157 Penny Siopis, Cape of Good Hope – A History Painting, 1989–90

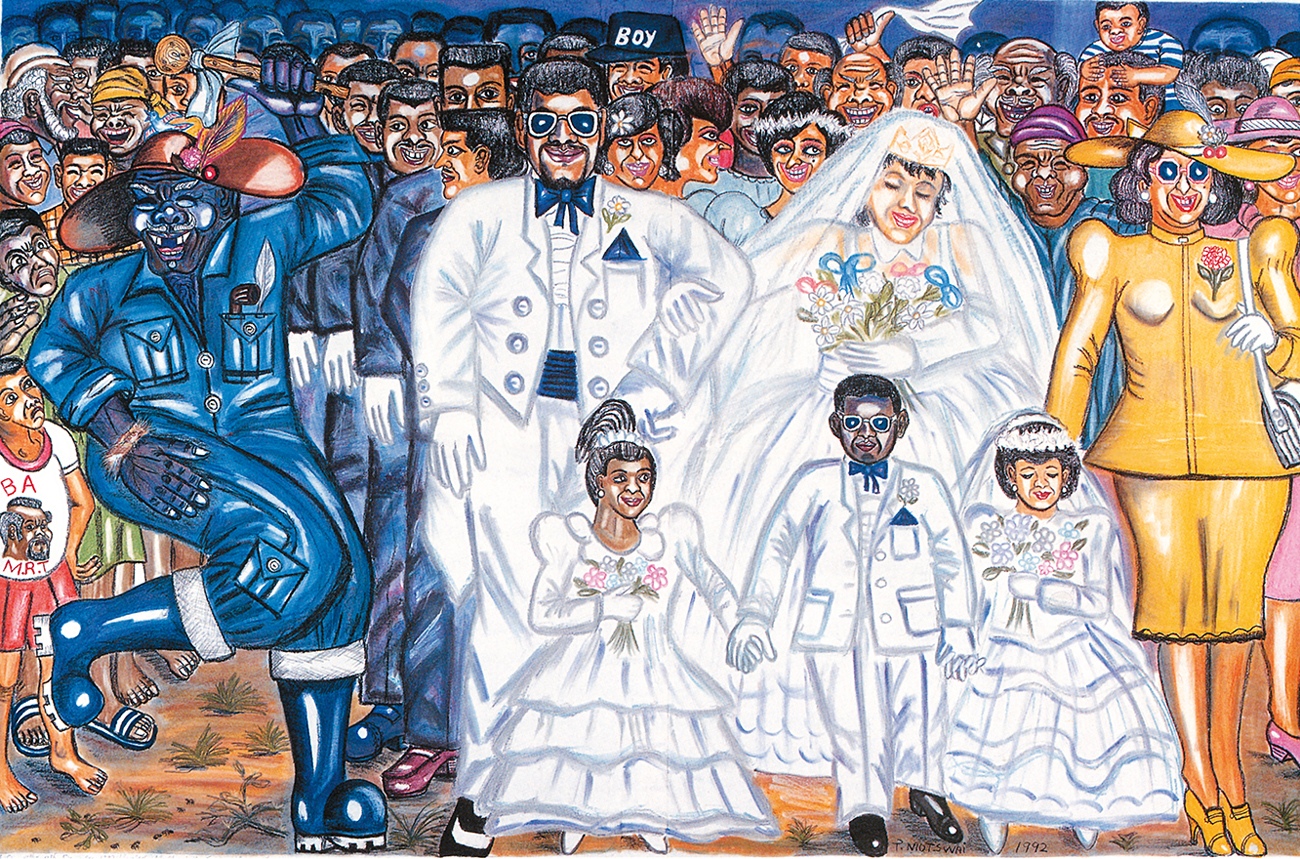

Finally, there is the expression of consciousness through satire, of which Tommy Motswai is South Africa’s master practitioner, rivalling the best of the flour-sack painters in Kinshasa (see Chapter 1). Informally trained at FUBA (the Federated Union of Black Artists) and in Bill Ainslie’s studio, he developed a richly descriptive style in which everyday urban life, as well as rituals such as the township wedding of an upwardly mobile politician, reveal the borrowings of European custom – the tea party, the white wedding dress, figures with modish haircuts and clothing – recontextualized into something uniquely South African.[159]

158 Alfred Thoba, Race Riots, 1977

The unifying agenda of art as a form of cultural resistance came to an end in 1994 with the beginning of majority rule. Resistance art’s first major repositioning as a critical response to the New South Africa took place in 1996 in ‘Faultlines’, an exhibition organized by playwright-curator Jane Taylor in Cape Town Castle, the Intelligence Headquarters for the South African Defence Force. ‘Faultlines’ invited activist artists to work with the Mayibuye (the Xhosa term for ‘come back’) Archive, an extraordinary collection of purloined and donated photographs, videos and paper documents gathered by friends and members of the ANC while in exile and returned to South Africa after independence. The exhibition also reflected the controversies surrounding the formation of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to hear accounts of government-perpetrated atrocities under the apartheid regime. The exhibits included Siopis’s Mostly Women and Children (1996), a room installation depicting the aftermath of violence, which featured a body cast of an African woman lying amidst a scene of destruction, while a fire flickered and cast shadows over the room.[161] It continued her longstanding focus on women as victims and witnesses in South African society and her penchant for layers of historical meaning (the body cast was taken from an ethnology museum storeroom).[162] Alfred Thoba’s White Nation Has Ill-treated Blacks. Thank You Mr F W de Klerk for Handing Over South Africa to Nelson Mandela. Your Kindness is So Handy (1996) continued his earlier political activist stance, but with an added element of scepticism for the new political order. Kevin Brand’s Pieta (1996), a duct-tape mosaic on an outside wall of the Castle became, at the proper distance, a pixellated TV image of the first student killed in the Soweto riots of 1976.[164] At the other end of the spectrum from these graphically realist works was Moshekwa Langa’s untitled installation (1996) of ghostly paper shapes putrefying with organic garbage, suggesting the fate of forgotten people not at the centre of the political stage. But the most controversial piece, Clive van den Berg’s Men Loving (1996), dealt not only with political violence of the past, but also with the homophobia of both black and white South Africans.[165] Two male figures, one black and one white, lay together on a shared grave with grass growing over them, a reference to an infamous event in South African history when just such a pair were punished by being tied together and drowned off the coast of Robben Island. The ‘Faultlines’ exhibition opened up both artists’ and the South African public’s consciousness to a much broader range of conflicting issues.

159 Tommy Motswai, On the 8th to 9th December 1990, Married Mr T and Mrs Evelyn, 1992

160 Willie Bester, Semekazi (The Story of a Migrant Worker), 1993

161 Penny Siopsis, Mostly Women and Children, 1996

162 Alfred Thoba, White Nation Has Ill-treated Blacks. Thank You Mr F W de Klerk for Handing Over South Africa to Nelson Mandela. Your Kindness is So Handy, 1996

Prior to the partial lifting of the ANC’s cultural boycott in 1987, even the most recognized South African artists worked in cultural isolation from the rest of the world, but that began to change with the ‘Art from South Africa’ exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford in 1990, followed by the first Johannesburg Biennale in 1995 and the second in 1997. The South Africa-centred view of art as a form of struggle, upheld by the ANC’s Cultural Desk and various Party committees, began to be destabilized in the more international critical climate ushered in by non-South African intellectuals, first by David Elliott at Oxford and then by visiting curators and art critics such as Rasheed Araeen and Thomas McEvilley in 1995 and Okwui Enwezor in 1997. Outside critics remain the newest brokers on the scene. While they have not replaced South African critics and curators such as David Koloane, Ivor Powell and the late Colin Richards, their operational bases in New York, Oxford and London mean that their opinions have more readily found a non-South African audience. Enwezor, a founding editor of the influential contemporary African art journal Nka, was artistic director of the Johannesburg Biennale in 1997. He brought an awareness of the cultural politics of art-making in both the USA and Nigeria, both of which gave him reason to see South Africa differently from most South Africans. His position that white South African artists either framed black subjects as voiceless and passive or sentimentalized them as victims essentially paralleled the critique made during the 1980s by Native American artists in the USA that white culture was only capable of representing them as stereotypes. This spawned newspaper and internet debates which ranged from sharply worded denials by some white artists to calculated self-promotion by others. If South African artists were seemingly moving towards ‘one South Africa’ in 1994, that sense of common identity has now been ruptured by global art institutions such as the Biennale and their accompanying critiques.

163 Jane Alexander, Street Cadets with Harbinger: Wish, Walk/Loop, Long, 1997–98. Alexander lives on Long Street in Cape Town, which has many street children – here referred to as ‘Street Cadets.’ Many of her works combine human and animal features, which create a sense of dread but also block easy recognition.

164 Kevin Brand, Pieta, 1996

165 Clive van den Berg, Men Loving, 1996

166 Kendall Geers, Mandela Mask (performance), 1996