167 Bacary Dieme, Water Carrier, c. 1970

If most of the new African art of the 1950s was born through the agency of European midwifery, a second, decolonizing stage led by African intellectuals began soon afterwards. This counter-movement, which began during the anticolonial wave that followed the Second World War, peaked in the ‘independence decade’ of the 1960s and has levelled off since, attempted to create national identities and public cultures that would reflect a distinctively African art, literature, theatre and music. Its rhetorical underpinnings were very different from place to place – some Marxist or Pan-Africanist, others Négritudist, or in large postcolonies, such as Nigeria, a whole spectrum (including those that were expressly anti-ideological). There was also a move to divest intellectual institutions – universities, museums, theatres – of their late-colonial aura. When Okot p’Bitek, a Ugandan poet, took over as director of the National Theatre in Kampala in 1967, he promptly and ceremoniously replaced the British Council’s grand piano on a stage with a drum post driven into the ground outside, announcing, ‘Our national instrument is not the piano – tinkle, tinkle, tinkle – but the drum – boom, boom, boom!’ Such pronouncements fed the debates over neo-colonial, national and pan-African identity which punctuated the first decade of political independence.

But beyond anti-colonial rhetoric, the very idea of a national culture raised difficult issues for the practising artist: was the art of Osogbo not demonstrably ‘Yoruba’ before all else? The more specifically an art and its practitioners are identified with a particular culture, the harder it would seem to replace this identity with a more inclusive national one. It has been easier to create a Senegalese or a Ugandan national art than a Nigerian one, because Senegal and Uganda did not possess the elaborate and complex traditions of pre-twentieth-century image-making found in Nigeria. But despite these major differences, all African countries have felt a similar need at the time of political independence to refashion their cultural identities – not only to distance themselves from the British Council’s piano, but also to move beyond perceptions of the tribal and traditional towards a much-vaunted but tentative modernity in the form of the nation-state. However, unlike ethnicities formed over generations through a continual process of local fission and fusion, the idea of a post-independence national identity had to be imposed all at once from the top down, by political leaders, government bureaucrats and intellectuals. Not surprisingly, this produced a wide gap between official and unofficial versions of a national culture, with most of its visibility confined to urban centres where universities, newspapers, museums and other institutions were clustered. In rural areas where most of the arts were produced by those who had minimal contact with either the colonial or the postcolonial state, being Tiv, Dogon or Acholi had a far greater immediacy than being Nigerian, Malian or Ugandan.

167 Bacary Dieme, Water Carrier, c. 1970

But beyond the urban–rural contrast, the divergent colonial experiences of anglophone and francophone African countries also mattered a great deal. The British principle of Indirect Rule meant that there was little interference in the day-to-day cultural life of the colonized, while all French colonial subjects were technically citizens of France and in some urban centres were even represented in the French parliament. While the British actively discouraged the idea of creating ‘black Englishmen’, France regarded assimilation of French cultural values as its greatest gift to its colonies. These attitudes – both of which were predicated on the idea of European superiority – deeply affected colonial subjectivity and the postcolonial construction of national cultures. Nowhere were these differences as obvious as in Nigeria and Senegal.

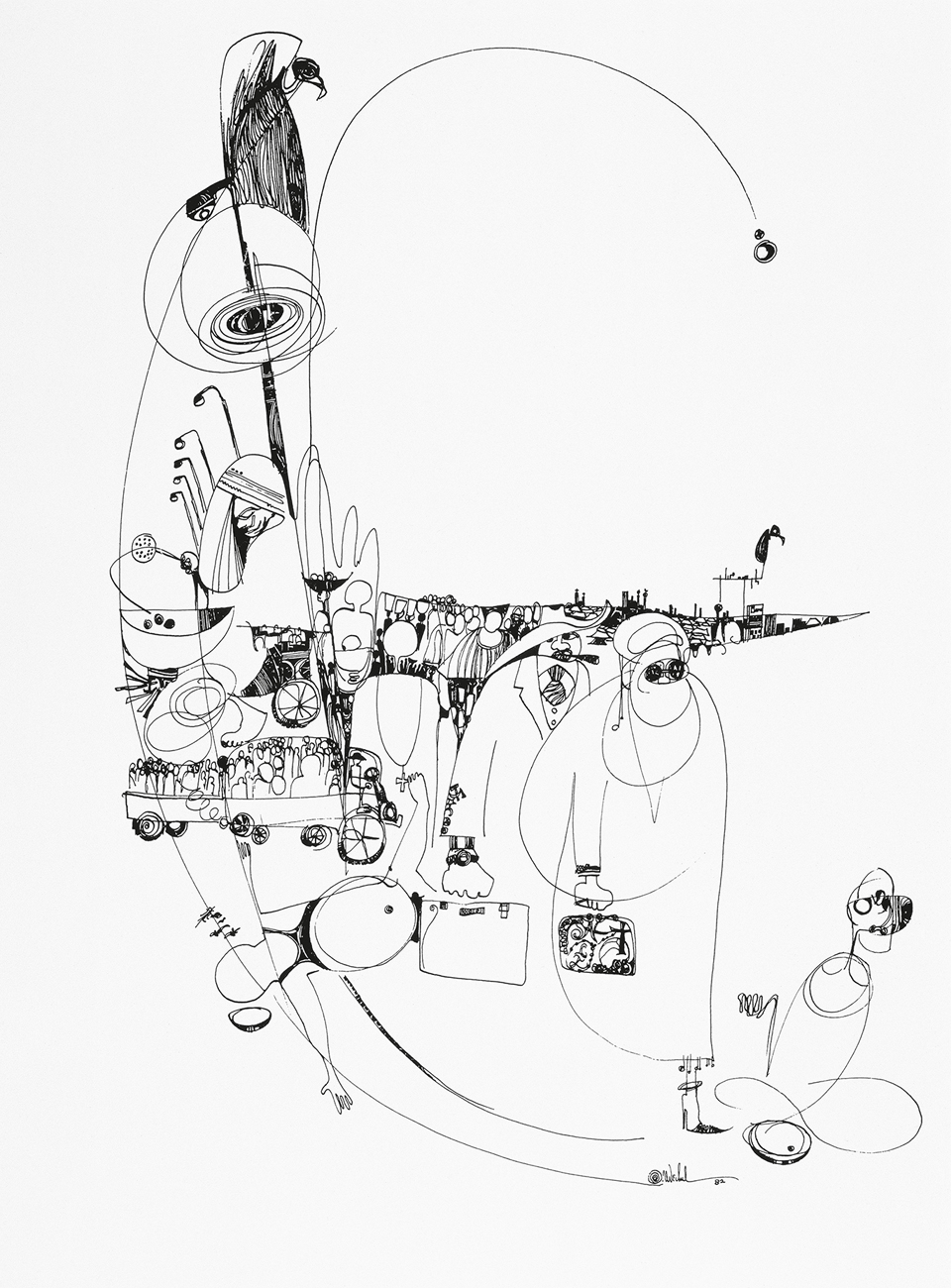

The primary ingredients of post-1960 Senegalese art were initially pictorial, and within that framework, much more abstract and decorative than the narrative realism that defines so much postcolonial African art. The group of artists who came to be called the ‘École de Dakar’ were the exemplars of this art in the 1960s and 1970s, when it enjoyed strong government patronage and international recognition. Although its subject matter was ostensibly ‘traditional’, the cultural distance of many artist-intellectuals from such traditions often turned them into decorative motifs. Boubacar Coulibaly’s Meeting of the Masks (1976) typifies this approach – Coulibaly was a sophisticated artist for whom masks had no independent reality, but were objects of compelling design.[168] In like fashion, tapestry artist Bacary Dieme’s Water Carrier (c. 1970) assimilates both mask faces and pottery silhouettes into a highly decorative but also very structured composition, in which traditional life is ‘referenced’ but not narratively described.[169] The tapestry medium itself, both in its decorative regularities and its very large scale, further objectifies and distances the subject.[167] Where this art came from, and how it earned its ‘Senegalese’ identity, reveals the powerful role a well-placed African intellectual can play in the game of cultural politics.

Whereas artists, poets and philosophers in most African countries find themselves outside the centres of power, Léopold Senghor was a major African poet, an eloquent spokesman for the philosophy of Négritude and the President of Senegal between 1960 and 1980 – the embodiment of what today would be called a ‘public intellectual’. This unusual juxtaposition of roles allowed him to play a decisive part in constructing a national cultural policy that recuperated ‘tradition’ (in its Négritudist reading as the primordial African past) and at the same time pragmatically embraced modernism (particularly in the acceptance of European-derived techniques and genres). At the opening of the Musée Dynamique during the historic Premier Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres (First World Festival of Black Arts) held in Dakar in 1966, Senghor stressed the longevity of the arts of Africa as well as their ability to ‘deepen our vision by setting the imagination free, by putting it back in touch with its intuitive qualities’. For more than a generation he continued to speak of a pan-African aesthetic based in the same Négritudist philosophy, but also to uphold the complementarity between African and European art-making as an essential basis for the birth of a national Senegalese art:

[Black African aesthetics] are the aesthetics of feeling, are object-related, harmonious, and are images impregnated with rhythm…. They offered [to European artists] a revolutionary example…. If Western art has changed under the influence of African sculpture, then contemporary African painting has cultivated a symbiosis between its own graphic tradition and the techniques of European cultures.

168 Boubacar Coulibaly, Meeting of the Masks, 1976

169 Boubacar Coulibaly, Le Masque I, 1973

Senegal’s artists and its national cultural agenda also had to resolve its anomalous position vis-à-vis African art history itself. As the historian Cheikh Anta Diop had observed in 1948, in Senegal, ‘sculpture had disappeared and painting had not yet developed’. Into this gap, which was occupied by textile arts, fine metalworking and other genres, on the eve of independence in 1960 Senghor proposed the establishment of a national art curriculum that would pursue both the conventional topics covered in the French academies and the more elusive subject of African aesthetics. In what is now the École National des Beaux-Arts du Sénégal, Senghor’s dual agenda was made concrete by the establishment of the Department of Fine Arts (Section Arts Plastiques), which taught drawing from plaster models, still life, anatomy, perspective, painting, sculpture and European and African art history, and the Workshop for Research in Black Visual Arts (Atelier de Recherches Plastiques Nègres), which was more experimental and amorphous.

The Department of Fine Arts was headed by Iba N’Diaye (1928–2008), an extraordinary master of line who had trained in Paris at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and was an independent artist not associated with the Négritude movement.[170] Sceptical of its ideology and the dangers of its confirmation of European stereotypes about Africans, he refused to ‘serve up folklore’ or the naive or bizarre – a position echoed by those artists today who resist the association of African art with primitivism. The workshop was headed by Papa Ibra Tall, also Paris-trained and, like Senghor, committed to the exploration of African expressive values in art and literature. Tall had studied not only painting but also tapestry and ceramics while in France, and wanted to incorporate them into the curriculum to develop ‘Art Nègre’ by modernizing African textiles and pottery arts.

The tapestry workshop was moved out of Dakar to Thiès in 1965, and the following year was inaugurated by President Senghor as the Manufacture Nationale de Tapisserie. In his speech he situated the origin of the tapestry technique in ancient Egypt, thus providing it with an African pedigree. It was to become the major artisanal technique by which contemporary Senegalese art made its debut internationally, in the form of large-scale public commissions. Most of the tapestry designers, such as Bacary Dieme, Ibou Diouf and Ousman Faye, had been practising painters as well.

170 Iba N’Diaye, Blues Singer, 1986. N’Diaye studied in Paris from 1949 to 1958 before returning to Senegal, where he was head of the Fine Arts Department at the École National des Beaux-Arts du Sénégal from 1959 to 1967. He distanced himself from the Négritude aesthetic, but shared its internationalism and thorough grounding in French intellectual life.

Tall was assisted by Pierre Lods, the Belgian expatriate who had founded the Poto-Poto School of Art in Brazzaville, Congo, and who was later recruited personally by Senghor. Ima Ebong, in Africa Explores (1991), has pointed out the inherent irony in bringing a European expatriate to help artists find the African essence in Senegalese creativity, but this flows from the importance of the colonial metropole, especially Paris, to the intellectual project of African modernism and the forming of national cultural identities. There African, African diaspora and European artists, students, critics and curators defined and contested the theories of Art Nègre, primitivism and modernism in ways that would dictate the framework of creative experiments in Africa during the years to follow.

Senghor experienced much the same Paris as McEwen, and formed his early intellectual agenda in encounters with many of the same artists and writers as McEwen had, including Picasso. He was fond of later recounting Picasso’s statement to him that, ‘We must remain savages’, to which Senghor says he replied, ‘We must remain negroes’, and then ‘[Picasso] burst out laughing, because we were on the same wavelength.’ Senghor later used Picasso as an example of the dialectic he hoped Senegalese art would engage: an artist who, although at the forefront of modernism, never forgot his Andalusian ancestry, and who after seeing the African masks at the Musée Trocadéro in Paris remarked, ‘[Painting] is not an aesthetic process; it is a type of magic which stands between the hostile universe and us, a way of seizing power, by giving shape to our fears and our desires.’ The philosophical principles of Négritude made the parallel claim that African art was anti-rational and deeply intuitive. In fact, both Picasso’s ‘magic’ and the ‘intuition’ of the École de Dakar painters were often challenged by their obvious formalist concerns, but the homage Senghor felt for Picasso was personal and deep.

On the one hand, the kind of sustenance that artists enjoyed under Senghor’s patronage was extraordinary, but, on the other, it contained serious limitations, because to receive full government support, artists had to subscribe to the official ideology of Négritude, which when translated into a set of formal practices eventually produced its own form of academicism. What began as an open-minded experiment evolved and hardened into official cultural policy. Meaningful criticism faded. Two things were inevitable – that the support would one day cease when Senghor left office, and that an artistic counter-movement would develop among those who refused to conform to the official ideology. This counter-movement began to gain momentum in the 1970s, as new initiatives were launched by artists in the converted army barracks which came to be known as Dakar’s ‘Village des Arts’, among them theatre workshops, films and jazz performances.

Out of this creative ambience, which was largely unofficial, Galerie TENQ (a Wolof word for ‘connection’) was inaugurated and staged four annual events between 1980 and 1983. Laboratoire AGIT’Art, a loose collective of visual artists and intellectuals involved in performance and led by El Hadji Sy, Issa Samb, Amadou Sow and Bouna Seye also worked in the Village during those years. But despite Senghor’s attempts to protect the Village for the future, in 1983 the new government evicted the artists from their subsidized living quarters and studios, unceremoniously tossing their possessions into the street.[171] In 1988, the Musée Dynamique, which had held the major Salons of the past twenty years, was handed over to the Department of Justice, who needed the site for a new building. Ultimately, the fragility of political patronage had proved to be as much a problem for artists in Senegal as elsewhere in Africa.

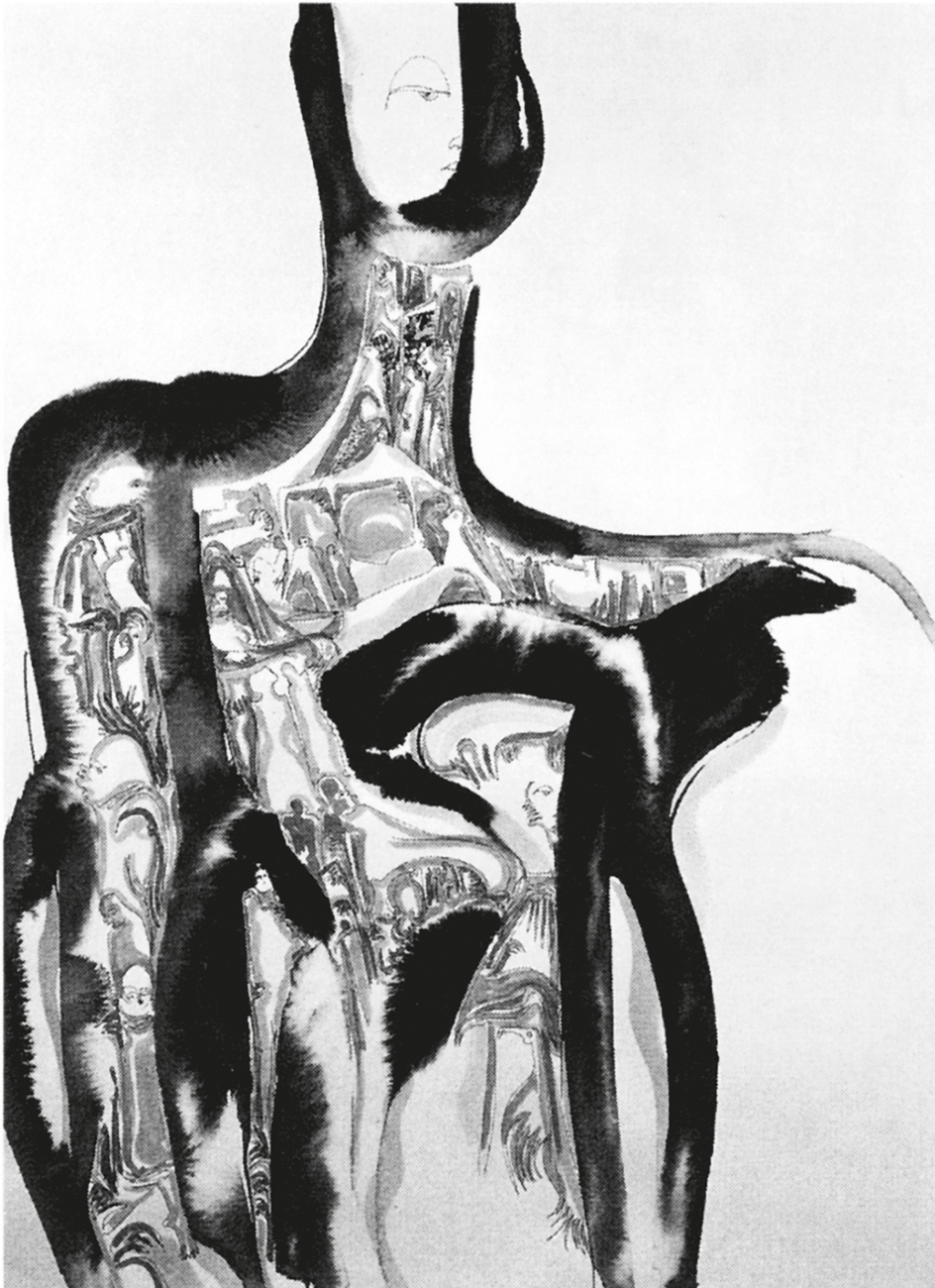

The AGIT’Art group at first included artists trained during the 1970s, who distanced themselves from the apolitical and often lushly decorative work of the École de Dakar painters and tapestry designers and experimented instead with conceptual art forms with explicit political and social content. El Hadji Sy (b. 1954) is a multifaceted artist whose work bridges that of Négritudist philosophy and the conceptualist and performance-centred AGIT’Art group, which he co-founded. ‘For the black African’, he wrote in 1995, ‘the visible is merely a manifestation of the invisible, which informs surface appearances, giving them colour, rhythm, life and meaning’. In a long career, he has remained true to forms such as his early painting Mother and Child (1987), which he redeployed in installation pieces for an exhibition at Frankfurt’s venerable ethnology museum in 2014, now renamed the Museum of World Cultures.[172] Issa Samb (1945–2017), trained originally in philosophy and law, was both an activist and group theorist, eclectically reworking an early modernist anti-aesthetic based in collage, objets trouvés and later, conceptual strategies such as blackboard sketches or handwriting combined with figuration.[173]

171 El Hadji Sy in his studio, Dakar, Senegal, 1992

172 El Hadji Sy, Mother and Child, 1987. The rough, wide horizontal brushstrokes suggest wrapping and binding – as with infants’ swaddling clothes or a mummy bundle.

173 Issa Samb, Untitled, 1992

Following the AGIT’Art example and inspired by the music of Youssou N’Dour’s Set (1990), a spontaneous youth movement called Sét Sétal (Wolof for the act of cleansing) emerged in 1991 and, in the space of a few weeks, erected sculptures and covered hundreds of walls in and around Dakar with impromptu murals.[174] Reminiscent of the Peace Parks that youths erected in certain South African townships towards the end of 1985, these artworks, wildly variable as they were, bridged the gap between aesthetics and social activism. They were ‘popular’ art, in the intellectual’s sense of a politically charged people’s art.

But the Senegalese genre that has been most ‘popular’ (in the rather different sense of appealing to the broadest public) is Souwer (glass painting), which more than either Négritudist painting or avant-garde AGIT’Art could lay claim to being a ‘national’ art form in the years preceding and following Senegal’s independent statehood. The glass-painting technique was imported from North Africa in around 1900, and the first examples were brought back to Senegal as souvenirs from religious pilgrimages. This accounts for the most popular subjects, which derive from the Koran or portray charismatic religious leaders. Prior to their discovery by collectors, they appeared in many homes as devotional images, though there was also a genre of satirical and decorative subjects, and they were used to frame photographs.[175] Gora Mbengue’s Le Grand Marabout (1984) exemplified the most prevalent iconic style among highly skilled artists – employing large areas of flat but strongly coloured shapes, which take on the luminosity of the glass. Later, Anta Gaye used glass painting as an experimental medium, in which she also employed collage and embedded fabric or small boxes behind the glass. While Senegalese cultural institutions originally resisted attempts to include glass painting in their ‘fine art’ collections and exhibitions, it has been eagerly bought by tourists and foreign collectors and ultimately has been canonized through scholarly attention.

Senegal is the best example of a country where a national art was brought into being through the efforts of African intellectuals, but it happened partly because there was no strong competing interest from indigenous art forms at the eve of independence in 1960. It was also, however, because one cultural ideology, that of Négritude, had its strongest voice in President Léopold Senghor himself, and for twenty years this ideology was synonymous with Senegalese national culture. In contrast, Nigeria was a country with a multitude of pre-independence plastic arts. The second major difference was that in Nigeria, artists and writers were not running the government. A third factor, which sets Nigeria apart from all other African states, was its sheer size and cultural diversity. There were more than two hundred languages spoken (each with several dialects) and many of these were paralleled by distinctive traditions of art-making. All of this worked towards a lively (and often competitive) heterogeneity at the time of independence, making any smooth transition to a ‘national’ art, culture or identity exceedingly complex.

174 Sét Sétal mural, Dakar, 1991

175 Gora Mbengue, Le Grand Marabout, 1984

Nigerian intellectuals themselves, helped or hindered by the politicians, have been central to the formation of new artistic identities, whether national, pan-African, international, counter-national or simply modern. But the example of the original Mbari movement and its subsequent transformation in Osogbo demonstrates the complexity of cultural politics in Nigeria and the way in which internal dynamics eventually outdistance the initial plans of the organizers. Although it ended up as a primarily Yoruba cultural phenomenon, Mbari began as something else, intended to be much more broadly Nigerian and even Pan-African. Two generations later, Mbari (which ceased to exist as an organization in the early 1970s) has entered oral tradition and acquired its own mythologies, each version reflecting the memories and positional role of its narrator. In some accounts, the initial impetus in 1960 came from Wole Soyinka (b. 1934), then a young playwright who had returned from studying in the UK and hoped to set up an acting company. Having learned of the Bauhaus and other European experiments, he says he was equally fascinated by the idea of artists coming together and creating ‘a mini culture of their own, apart from the general political culture…but always in relation to [it]’. The other crucial actor, cast in the role of fundraiser and facilitator, was Ulli Beier, who had been in Nigeria since 1950. Beier had extracted a promise of foundation support for new cultural initiatives, and urgently needed a concrete arts funding proposal to give them. Soyinka, then based in Ibadan, called together a group of young writers including the South African Ezekiel (Es’kia) Mphalele and Nigerians Cyprian Ekwensi and John Pepper Clark, the composer Akin Euba, and artists including Demas Nwoko, Uche Okeke and Bruce Onobrakpeya. At this stage, the group was still a loose collection of artists and writers from various parts of Nigeria or abroad, most of whom shared an interest in performance genres. Had it continued in this vein, the Mbari Club might have remained a group of intellectuals interested in developing a public culture through performances, exhibitions and workshops.

But through a series of chance happenings, a different version of Mbari was developed, transforming into something Yoruba-centred and primarily a means of expression for unschooled artists and performers. Beier, then an extra-mural teacher at the University of Ibadan, was living in the Yoruba town of Osogbo in the compound of Duro Ladipo, a primary-school teacher. Ladipo, who was also a mission-educated Christian, first revealed his prodigious musical talent in an Easter Cantata he composed and performed for the Anglican church in Osogbo and then, at Beier’s invitation, at the Mbari Club in Ibadan. In the flush of this initial success Ladipo returned to Osogbo with the idea of forming his own opera troupe under the organizational umbrella of Mbari.

The Osogbo outpost was therefore also called Mbari – as was another centre begun in Enugu – but this unfamiliar Igbo word was translated by the local townspeople into the Yoruba term mbari (said with a different tone pattern), which meant ‘if I were to see or encounter’, to which was later added mbayo, ‘I would rejoice’. Because the new Mbari Mbayo was located in an up-country Yoruba town – slightly down-at-heel economically but an important ritual centre because of the Oshun river and sacred groves – rather than in the culturally heterogeneous and sophisticated Ibadan, it attracted a broad cross section of the young and jobless from the community rather than the artist-intellectuals usually found in university settings. They were all Yoruba, and few had been educated beyond primary school. Their ‘Yorubaness’ was both vital and unselfconscious, and formed the context for the images and narratives they created. Unlike elites, they did not have to unlearn European teaching. At the same time, the commitment to a national cultural identity was now being filtered through a specifically Yoruba sensibility.

The other point to note about the Mbari example is the crucial role played by Ulli and Georgina Beier, and also Susanne Wenger (see Chapter 3). They were not the only expatriates involved: the format of a brief workshop to teach techniques was dependent on a synergy created by bringing in a stranger to work with local participants. These included the African-American artist Jacob Lawrence, the Guyanese artist and art historian Denis Williams and the Mozambican painter Valente Malangatana.[176] These expatriate artists, many of them black, were also interested in using the workshops as a stimulus for their own work.[122] Mbari Mbayo was later criticized by some Yoruba intellectuals for being too much of an expatriate creation. Conversely, it has been criticized by other Nigerians for being too Yoruba-centric. The right circumstances to produce a modern, but also Nigerian, art have proved to be elusive. Such a scenario would have to be culturally heterogeneous, unofficial (to avoid becoming overly institutionalized), participatory (from the bottom up, instead of top down) and with a healthy dose of past artisanal traditions thrown into the mix.

176 Jacob Lawrence, Nigerian Series, Street to Mbari, 1964

A Nigerian movement that came somewhat closer to this ideal was a group of artists based mainly at the University of Nigeria at Nsukka, loosely known as the Nsukka Group. Like the Mbari Clubs and the École de Dakar of the 1960s, the Nsukka development was fed by the encounter of a group of academically trained modernist intellectuals with their ethnic identities and ancestral past. The central figure in the early stages was Uche Okeke. In 1958, while an art student at what later became Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, northern Nigeria, he and fellow students formed their own unofficial organization called the Zaria Art Society (aka the Zaria Rebels), which tried over the next four years to structure a new approach to art by moving beyond the Eurocentric art academy curriculum. At least three of its leading members – Uche Okeke, Demas Nwoko and Bruce Onobrakpeya – became part of the Ibadan Mbari Club, and continued to be major influences in Nigerian culture for over a generation. While still a student, Okeke became spokesman for the Rebels’ position:

Nigeria needs a virile school of art….Whether our African writers call the new realisation Negritude, or our politicians talk about the African Personality, they both stand for the awareness and yearning for freedom of black people all over the world….I disagree with those who live in Africa and ape European artists….Our new society calls for a synthesis of old and new, of functional art and art for its own sake.

But what soon divided Nigeria sharply from the other newly independent states was the experience of Biafra: a war of secession that isolated the Igbo and their Eastern Region neighbours. Nigeria’s first military coup in January 1966 was soon followed by pogroms by northern Muslims against the Igbo and other Christian southerners living in the northern cities, forcing the Igbo in these cities to return to their Eastern Region homeland. In the early 1960s the new University of Nigeria at Nsukka, in northern Igbo country, had adopted an American-style curriculum as an alternative educational model to the British one. But the pogroms of 1966 forced Igbo students studying in Zaria to return to the safety of Nsukka, while non-Igbo teachers and students at Nsukka did the opposite and returned to their home regions. This quickly ‘Igbo-ized’ what had been an American-style art department, and also brought in the Natural Synthesis ideology from Zaria. The northern massacres and subsequent bombing raids by federal planes forced these artists, along with everyone else, to come to terms with their Igbo identity. When the war forced the closing of the University from 1967 until 1970, artists such as Okeke became involved in the Biafran war propaganda effort. When the war ended, the badly damaged university reopened and Okeke became the acting head of the Department of Fine and Applied Arts.

How did the Civil War experience affect the earlier idea of Natural Synthesis? Okeke’s Zaria group was multi-ethnic, like the Ibadan Mbari Club of the same period, so it was important to lay claim to all of the Nigerian past, not just one piece or another, as a context for their modernity. But a decade later at Nsukka, everything had been reconfigured – just as the change of location from Ibadan to Osogbo inevitably changed the focus of the Mbari workshops, so the transition of artists and art education from Zaria to Nsukka did the same. After finishing at Zaria, in 1962 Okeke had travelled to Germany before returning to Enugu, where he directed the local Mbari cultural centre from 1964 to 1967. Okeke’s interests at Enugu centred on a revival of precolonial Igbo art forms, especially the uli designs painted by women on the female body and on the walls of houses and shrines.[177] These differed from one part of Igboland to another, ranging from semi-abstract representations such as the sacred python to non-figural graphic symbols and free-form curvilinear patterns. The rope-like, calligraphic lines of the uli designs were reinterpreted by Okeke in his Mma-Nwa-Uli (1972), although he added a coloured ground and reversed the uli patterns from the usual deep blue or black to white.[178]

177 Painted uli body designs, Awka District, Nigeria

178 Uche Okeke, Mma-Nwa-Uli, 1972

Okeke introduced this interest in specifically Igbo forms such as uli into a department where both teachers and students had experienced the extremes of ethnic violence and displacement. The initial interest in uli was both aesthetic and political – it linked their modern intellectualism to a specifically Igbo subjectivity. But in the university and on the streets, this was now tempered by the fact that the Igbo had lost the war, and they were all Nigerians now. This mattered because it opened people’s minds up to other kinds of experimentation; only a few of the Nsukka-based artists who became known as ulists continued to use uli as their main design source.

Obiora Udechukwu (b. 1946) was drawn to uli when he was one of Okeke’s students, but he was also influenced by the calligraphic style of the Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi (see Chapter 6) with whose work his own pen and ink drawings display a deep affinity.[179] Udechukwu was forced to leave Zaria in 1966 and return to the Eastern Region, where he began studying at Nsukka. His studies were interrupted by the war, but later he was awarded two degrees and eventually replaced Okeke as the most influential teacher in the department along with Chike Aniakor (b. 1939), another significant uli artist.[180] Aniakor’s best work is also strongly calligraphic, and like Udechukwu’s goes well beyond the straightforward replication of uli symbols in a new context. If Okeke’s work can be compared with Chinua Achebe’s concern for the survival of Igbo culture in his early novels such as Things Fall Apart and Arrow of God, the comparable literary genre for the work (particularly drawings) of Aniakor and Udechukwu would be found in Igbo poetry. Nearly all of the Nsukka artists have written poetry themselves, which suggests that it is the lyric quality of line as well as its concise narrative ability that seems to connect poetry and drawing.

179 Obiora Udechukwu, Road to Abuja, 1982

180 Chike Aniakor, Allegory of Power, 1996. Simon Ottenberg describes this series as visual equivalents to the oral narratives recited by African minstrels. Aniakor calls them ‘visual epitaphs’, each containing stanzas or messages.

Udechukwu has also drawn freely on the script and secret sign system known as nsibidi, from the neighbouring Cross River region of Nigeria, sometimes using one or two isolated signs, such as the spiral or mirror, and at other times creating a band of nsibidi signs resembling a cartouche of Egyptian hieroglyphs.[181] In Writing in the Sky (1989), a group of unidentified people are silhouetted against the background of the Nsukka hills while above their heads a large sun-like spiral hangs in the sky with an attached band of nsibidi, like an unreadable message or prophecy. Udechukwu is an artist of great complexity as well as a highly perceptive critic and intellectual, qualities which made him the central figure in the Nsukka Group after Okeke’s premature retirement in 1986. Like several of his former students, he later emigrated to the USA to avoid the repressive military regime. He taught at St. Lawrence University in upstate New York until his retirement.

181 Obiora Udechukwu, Writing in the Sky, 1989

182 Tayo Adenaike, Evolving Cosmos, 1996. The artist has explored myths, legends and symbols from Igbo and Yoruba cultures, and says, ‘stylistically the Igbo uli rhythmic elements have [been] and still remain a source of fascination to me. Circles in my work have always been used to depict the “single eye of heaven” that lights and perhaps makes us see the world.’

Not all the Nsukka artists are Igbo or even Nigerian, though they all trained or taught at Nsukka, and so share a common set of experiences. Younger artists who became known through the Nsukka connection include Tayo Adenaike, who is Yoruba but studied under Udechukwu, Okeke and Aniakor between 1974 and 1982. Although he briefly worked with acrylic, he has developed as a fully realized watercolourist, beginning from a strong connection with the work of his mentor Udechukwu. Adenaike’s Evolving Cosmos (1996) deals with the event of cosmic creation through the use of overlapping planes of cloud-like colour pierced by a central opening and embellished with uli dots (ntupo), suggestive of a face or human presence.[182] He also became a successful commercial designer.

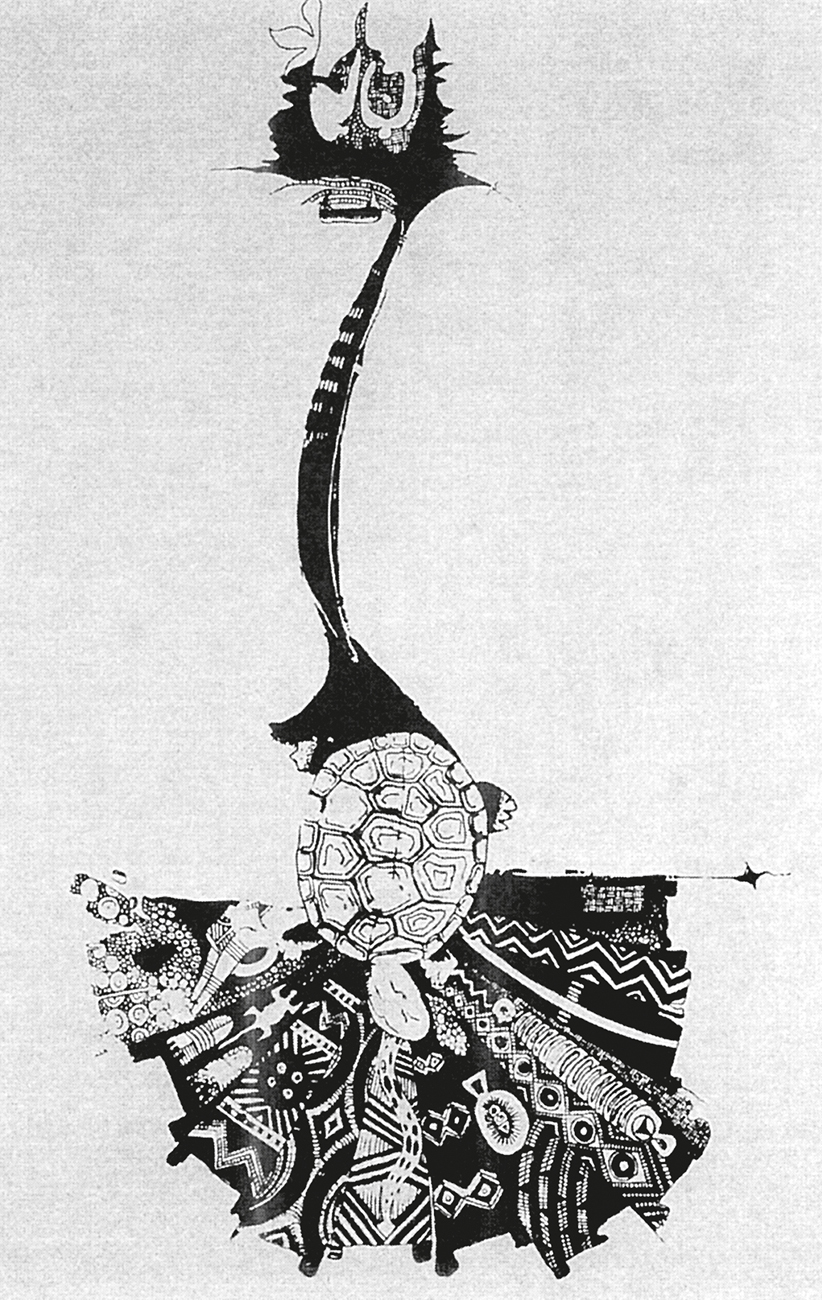

Barthosa Nkurumeh, another protégé of Udechukwu, created a highly decorative style reminiscent not only of his mentor’s, but of Aubrey Beardsley drawings and tapestry designs by Senegalese artists such as Bacary Dieme.[183] Nkurumeh referenced uli along with a wide variety of textile and weaving patterns, and a calligraphic, linear style.[167]

El Anatsui (b. 1944), a Ghanaian, joined the teaching staff at Nsukka in 1975 and only recently retired, though he retains his house and studio in the Nsukka hills.[8] He is exceptional not just because he is an expatriate, but also because he is deeply involved with wood as a medium. However, like the others, he shares a strong commitment to working with an African visual grammar and extending it into new techniques and media. He has identified this principle with the Twi expression sankofa (‘go back and pick’). The ‘going back’ includes, in his visual repertory, the patterns of Ewe weaving and the adinkra and kente cloth designs that he absorbed during his student days at the College of Art, Science and Technology in Kumasi.

Combining his interest in cloth and wood, his early work comprised a series of relief panels made from narrow vertical strips of wood cut with a power saw on which designs are burned in and sometimes overpainted. The strips, which are analogues of strip-woven cloth, can be reassembled in different orders and relative heights, a process meant to involve the viewer in making aesthetic decisions. His monumental 1992 installation Erosion is constructed from a central stepped pillar and pieces at the base which appear to have fallen off. Although produced for an environmental art workshop that preceded the Earth Summit in Brazil, El Anatsui told the critic Chika Okeke-Agulu that it was not about soil erosion, but something more basic – the erosion of cultures.

183 Barthosa Nkurumeh, Nna Mbe, 1991. In the artist’s own words, ‘In Igbo folk tales, Mbe the tortoise is a trickster. Thus I imposed him on a fan-like composition portraying aspects of the Igbo world. A cord links him with a ritual pin and people telling the tales.’

After 2000, these complex works in wood gave way to the development of a new medium. The artist began to produce flexible wall hangings fashioned from brightly coloured discarded plastic bottle caps from European liquor bottles, attached together with fine copper wire. Over the years these have grown in size and complexity, resembling shimmering textiles from a distance, and calling to mind both Ghanaian kente cloth and free-form relief statue. Their extraordinary beauty and size have led to international fame for El Anatsui, whose work is now collected by a number of major museums globally. In 2007 he was awarded first prize at the Venice Biennale, and in 2015 received the Golden Lion award for lifetime achievement on the recommendation of that year’s curator, Okwui Enwezor.

184 Bruce Onobrakpeya, Shrine Set, n.d. The critic Chika Okeke-Agulu remarked on the interface created here between ‘subject and object’ and ‘artist and priest’.

Although not a member of the Nsukka Group, former Zaria Rebel and Mbari Club member Bruce Onobrakpeya’s work as an independent printmaker had a strong affinity with Nsukka-produced graphics and has undoubtedly influenced many Nsukka students and teachers.[184,185] His installation work converged in interesting ways with that of El Anatsui, imprinting small written symbols on larger, harder materials such as wood. If there is any single shared preoccupation in this group of artists it is the liberating use of symbols of a West African past plucked from numerous artisanal traditions and reworked as a form of modern cryptography.

185 Bruce Onobrakpeya, Emeravwe (Lunar Myths), 1983