63 Teenage apprentice to the late Lawrence Alaye at work on a relief panel, Ile-Ife, Nigeria, 1978

To even begin to chart the complex spectrum of work produced by African artists, one must deconstruct the important differences in training, knowledge, attitude and types of artistic production among untrained artists (so-called autodidacts), those who are informally trained (usually in workshops or cooperatives), and those formally schooled in universities or independent art schools (some of whom spend all or part of their careers outside Africa). Different critics and curators have identified the cultural production of one or another of these groups as ‘the’ significant African art of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, while relegating the other two to secondary importance. Such arguments are caught up in both authenticity debates and the economics of the art market. Untangling these issues is one of the aims of this book. Although they occupy different class positions, trained and untrained artists live in and react to the same world and many of the same collective experiences. The linkages of history and social differentiation form the warp and the weft of a single fabric.

Colonialism forced a restructuring of existing artistic practice, but did not do away with it. We know, for example, that in Yorubaland, Areogun (1880–1954), who was perhaps the greatest of the Yoruba sculptors from Ekiti of his generation, spent some sixteen years in his apprenticeship before he left his master. But since Areogun’s time, apprenticeships have had to compete with academic and vocational training schools and new forms of artisanship, such as electronics and car repair. By 1980 they typically lasted no more than four years and were preceded by (or even ran concurrently with) a school education.

The late Lawrence Alaye, an Ekiti Yoruba sculptor who was active in Ile-Ife in the 1970s, was typical of the first postcolonial generation of Yoruba carvers who bridged the gap between the old apprenticeship system and the new.[63] Initially he learnt the traditional Ekiti forms, such as Epa masks, from his uncle, but like his more famous colleague Lamidi Fakeye (1928–2009), he also trained at Oye Ekiti and was later patronized by the academic community at the University of Ife, now Obafemi Awolowo University. To show his repertory to this wide variety of potential clients, he kept a photo album in the workshop showing pieces he had made. Both of his apprentices, then in their early teens, had been to primary school and spoke English. The several kinds of patronage Alaye received illustrate the beginnings of the modern workshop or cooperative which, although given over to new genres, was still faithful to the master-apprentice model. It is these continuities in practice, and not just a particular mix of genres, that have helped define contemporary African art.

Other traditional training practices have been less structured than the Yoruba apprenticeship model. In the Niger Delta in the 1960s, young Kalabari boys had a hands-on, informal training period as members of the junior Ekine society, during which they learned to fabricate mask ensembles. Similarly informal methods of training have continued to play a major role in many kinds of art-making. The essential ingredients are just three: aspirants with a need or desire to learn a fairly circumscribed set of procedures (whether mask assemblage or an imported technique such as linocut printing), an environment in which the skills can be acquired in a relatively short time (days or weeks instead of years), and a facilitator convinced of its importance. Once, that facilitator was the community or one of its important institutions (such as a masquerade association), but after the onset of colonial administration, the facilitator was just as likely to be an individual and an outsider to the culture. In the famous and high-profile examples such as the workshops run by Ulli and Georgina Beier and their colleagues in Osogbo, Nigeria, in the early 1960s, the facilitators were primarily (though not exclusively) expatriates and were impelled by a conviction that African creativity was a latent force, locked inside numerous (usually male) individuals, but fettered by the new social conditions imposed upon them through the demise of traditional society under colonial rule. The purpose of the workshop was, on a practical level, to provide would-be artists with skills that would enable them to be practitioners. But philosophically, the workshop’s purpose was to release the creative energies that were thought to lie deep within these individuals. This belief has its historical and intellectual origins in Rousseauian ideas of a highly integrated culture that is destroyed by the civilizing process – in this case represented by the colonial experience. It idealizes the ‘state of nature’ and ‘traditional society’ as pure sources of artistic inspiration while devaluing forms of cultural expression which arise out of conquest. Colonialism then becomes a kind of bondage from which the workshop artist breaks free. But ironically the particular brand of consciousness required to set this in motion (and more importantly, the contacts and resources) inevitably came from the colonizing culture.

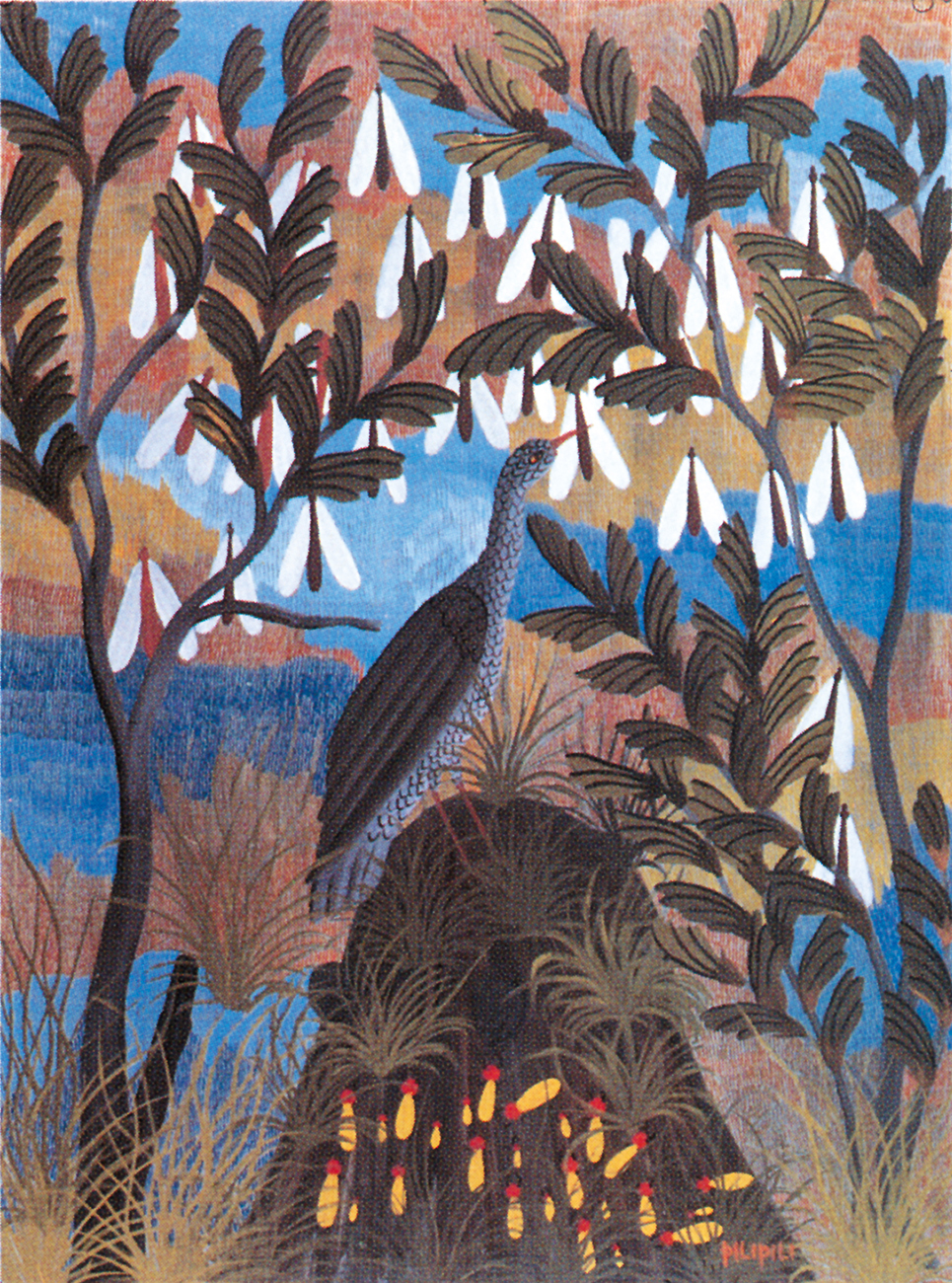

Among the expatriates who set up workshops were Frank McEwen (1907–1994), founder of the Salisbury Workshop School in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe; see Chapter 4) and Pierre Romain-Desfossés (1887–1954), whose Atelier d’Art ‘Le Hangar’ was founded in Elisabethville (now Lubumbashi) in 1953, during the last decade of Belgian rule in the Congo. Believing that his Katangais students would be contaminated by exposure to Western art and the ‘uniformizing aesthetics of White masters’, Romain-Desfossés sought to imprint on them a new visual sensibility at the crossroads of African creativity and late-colonial modernism. He insisted that they look around them and learn from what they saw. His rhetoric was familial: they were his ‘children’, he their ‘father’, but as V. Y. Mudimbe, Congolese philosopher and cultural critic, has pointed out, it was also oracular – they were his disciples. The painters he trained, such as PiliPili Molongoy, Mwenze, Bella and Kabala, developed individual styles based on a finely detailed representation of flora and fauna on a flat pictorial surface.[64] Romain-Desfossés’ students were not the first or the last Congolese artists to adopt this style and subject matter – it has an innocuous, dream-like appeal that makes it easily acceptable to a European audience, a Douanier Rousseau in Central Africa.

63 Teenage apprentice to the late Lawrence Alaye at work on a relief panel, Ile-Ife, Nigeria, 1978

64 PiliPili Molongoy, Termites and Birds, c. 1970

Both Romain-Desfossés in the Congo and McEwen in Rhodesia embraced the Jungian notion of a collective unconscious in which artists retained deeply ingrained archetypal ideas of form, imprinted as cultural memory. Even though neither worked with artists who were practising in traditional genres when they joined the workshops, both men wrote that traditional forms would always be retrievable from the memory. Such ideas were also current in the United States from the 1930s to the late 1950s, among New York artists and intellectuals such as Jackson Pollock, who studied and collected Native American art. In both Romain-Desfossés’ and McEwen’s schools and among the New York avant-garde, the tribal artist was seen as someone living in a familiar relationship to a mythic past, only superficially touched by the colonial experience (in Africa) or the realities of the ‘folkloric’ art market (in the USA).

However, in places where a fully realized visual art tradition (e.g. wood sculpture) had withstood the transformations of the colonial period, it was not necessary to retrieve long-forgotten mythologies and artistic practices under nurturing conditions. The challenge was to find a way to introduce new genres in an artistic environment dominated by ritual sculpture produced in family workshops.[65] Therefore the dynamic at work in the Yoruba workshops that were founded by expatriates was a different one from that in Romain-Desfossés’ and McEwen’s. As Ulli Beier himself once put it, if McEwen’s project ‘could be compared to an Israeli farmer fertilizing the Negev’, working in Osogbo was ‘more a case of trying to tell the wood from the trees’. Both Father Kevin Carroll of the Society of African Missions and Ulli and Georgina Beier found themselves supervising enterprises which did not require either Jung or Rousseau to understand, though they differed sharply from each other. A third Yoruba project begun by an outsider, the reconstruction of the sacred shrines around Osogbo, was instituted by the Austrian-born artist Susanne Wenger.[67, 68] While Wenger’s project could not be called a workshop, it overlapped the Beiers’ in time and space and so can be compared to the others.

65 Yoruba children carrying Christian images at Christmas, Oye Ekiti, Nigeria, 1951

Something different was happening in each of these situations. The carvers (including the subsequently famous Lamidi Fakeye) who trained at Father Kevin Carroll’s workshop at Oye Ekiti were engaged in a variant of the Yoruba apprenticeship system – they were learning a new artistic genre under the tutelage of Areogun’s son Bandele of Osi, but using traditional Ekiti carving styles and techniques to create Christian subjects suitable for use in the Church.[66] By definition then, there could be no wholly new inventions. Similarly, there was no notion of the artist ‘unfettered’, breaking loose from the shackles of colonial thinking. Instead, Carroll wanted to draw upon what he saw as the deep integrity of an established artistic practice in service of the sacred. Despite the enormous differences in their personalities and artistic philosophies, he and Wenger had this in common. She, too, took up the task of creating a new kind of sacred art in partnership with a small group of Yoruba artists, though everything about it contrasted with Carroll’s undertaking.

66 Lamidi Fakeye, Flight into Egypt (detail) panel on the doors of St Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, Oke Pade, Ibadan, 1956. The artist was originally trained in the Igbomina style, but adopted the Ekiti style after studying at Oye Ekiti.

67 People sit in front of the shrines in the sacred grove of Osun-Osogbo during the Osun-Osogbo Festival in Osogbo, southwestern Nigeria, 17 August 2018

68 Susanne Wenger, shrine for Iya Mapo at Ebu Iya Map near Osogbo, Nigeria, n.d.

The shrines in the sacred forest groves outside Osogbo, each consecrated to a different Yoruba orisha (deity), had fallen into disrepair and were threatened by the encroachment of farms and businesses. Wenger rebuilt these shrines during the 1960s and 1970s with the help of local artists Buraimoh Gbadamosi and Adebisi Akanji, among others. Wenger was very critical of conventional missionary teaching and instead embraced Yoruba religion, becoming an initiate and later a priest. To sceptics, including many Yoruba academics and intellectuals, she was simply one of the odd, but predictable, side-effects of colonialism, in search of a life untainted by the corruptions of the West. But to sympathizers, including her friends and associates in Osogbo, she was a charismatic artist with a life-long commitment. As she aged, she commanded the respect that Yoruba culture accords to powerful older women.

Wenger’s style and techniques bore no relationship to traditional Yoruba sculpture. In The Timeless Mind of the Sacred (1977), first published in German, she propounded a religious philosophy that focuses on the mystical nature of the sacred. Translated into shrine sculpture, this became a series of non-representational organic curves and wave-like forms, created first in the adobe-like mud used for housebuilding and later coated with cement, giving them both permanence and a very light colour uncharacteristic of African wood sculpture. Unlike the practice of both Carroll’s and traditional workshops, her methods sought to tap into something other than Yoruba artistic convention. An early example of this was the wall surrounding the Oshun grove, rebuilt by two bricklayers, Ojewale and Lani. Wenger encouraged them to draw in the wet cement, and even though they did not think of themselves as ‘artists’, they created a long frieze of whimsical low-relief figures.

Another more talented bricklayer and cement mason, Adebisi Akanji, became Wenger’s principal assistant in the shrines project. He was one of the first generation of Osogbo artists of the early 1960s who established themselves through a close relationship to Ulli and Georgina Beier or Wenger. The initial ‘discovery’ of Akanji as a sculptor is described by Ulli Beier in his book Contemporary Art in Africa, published in 1968. It reveals how contingent an artist’s recognition is upon not only talent, but also meeting the right patron at the right time. In 1962, while organizing an exhibition of Nigerian ‘folk art’ to be held in Ibadan, Beier invited a group of Osogbo bricklayers to try their hand at making the decorative cement lions found on older Yoruba ‘Brazilian-style’ houses that were no longer being made. Akanji proved to be the most talented of these young ‘folk artists’ – but what does one do with a cement lion? At first he was patronized solely by staff at the University of Ibadan, who ordered his cement animals as garden sculptures, but this work (in Beier’s words, ‘producing garden toys for intellectuals’) was very limiting for Akanji, both in the scope it offered him to develop as an artist and in the number of possible commissions he could receive.

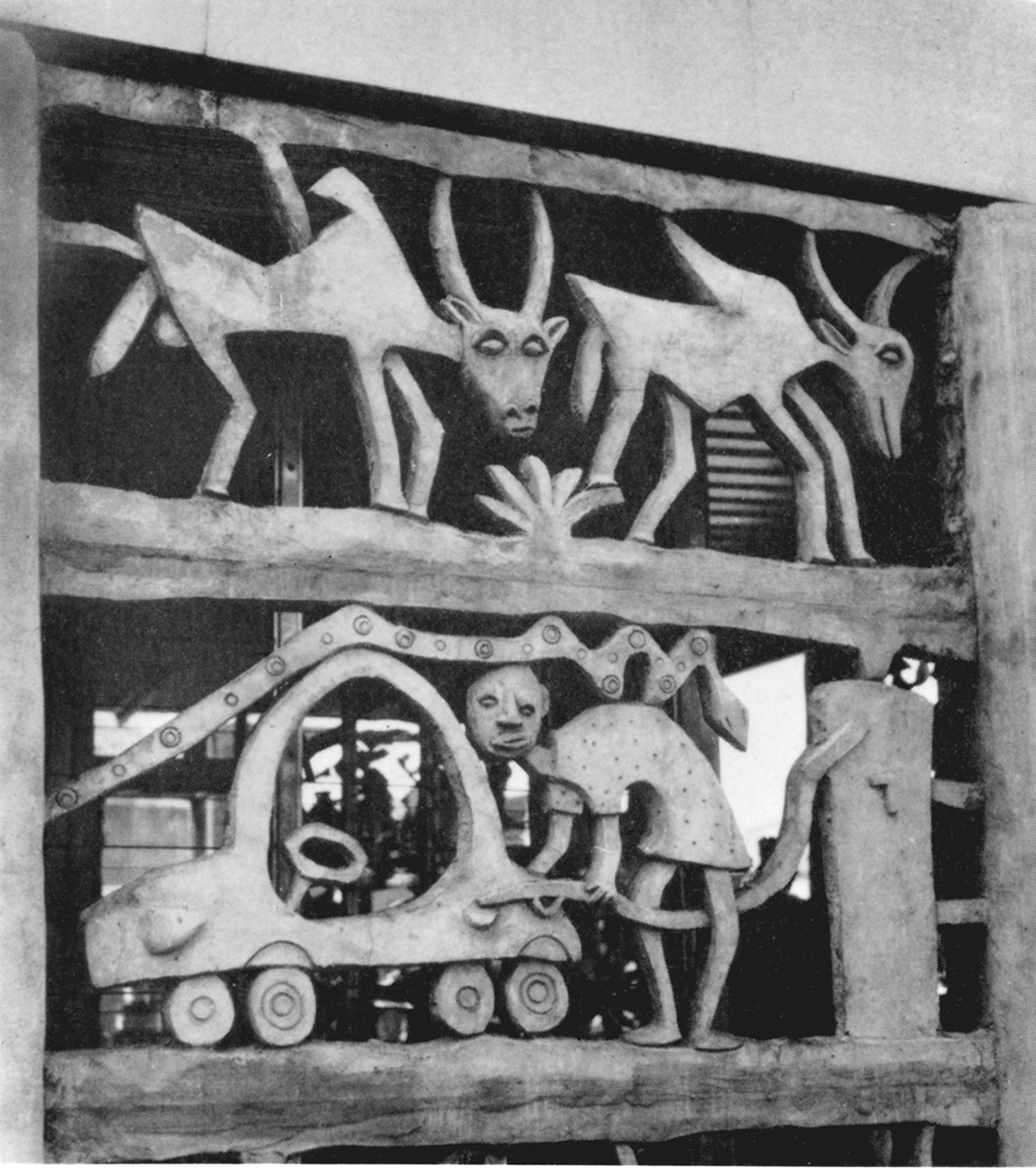

At this point, only an act of cultural entrepreneurship could move the artist beyond this stage. Beier had decided to construct a museum of popular art in Osogbo and, seeking another avenue for Akanji’s talent, asked him to make a cement screen of animals and figures at the entrance to the museum.[69] This was technically difficult, but Akanji came up with a solution whereby he made a perforated cement screen with multiple registers of flattened figures, attached at the top and bottom of each register, but otherwise free-standing in space. This was a new genre and lent itself easily to architectural forms, but could also work as sculpture on its own. The most widely known example of his cement-screen technique, an Esso Petrol Station in Osogbo, displays sport scenes from the creolized town culture of the mid-1960s – motorcars, palm-wine drinkers and masquerades.[70] In one scene, the artist plays on the idea of the car and petrol pump as living beings by depicting a real snake slithering across the car’s roof while an attendant pumps petrol through a hose, another ‘snake’. But Akanji was also able to adapt his whimsical icons and cement medium to the low-relief decoration of solid walls, and in the same year that he made the petrol-station screen he also completed the entrance to the Oshun grove, which Wenger had rebuilt.[71] It did not matter to him that one was a ‘secular’ and the other a ‘sacred’ commission, nor did it matter especially that he was a Muslim. Although such loyalties can come into conflict – a fact attested by the twentieth-century decline in active followers of the orishas – they continue to coexist for many people.

69 The artist Shangodare G. Ajala standing before Adebisi Akanji’s cement screen at Susanne Wenger’s residence, Osogbo, 1978

70 Adebisi Akanji, detail of a petrol station screen, Osogbo, 1966

71 Adebisi Akanji, Ilogbo shrine, n.d.

We can say then that there were several types of cultural mediation operating simultaneously in the Osogbo projects of the 1960s: one had to do with artists and patrons, another with the religious and cultural idiom in which the art was produced, and a third with the interplay between educated intellectuals, some of them expatriate and others Nigerian, and an emergent class of urban skilled workers (the artists) in Yoruba society.

A lack of training opportunities for prospective artists was common everywhere in Africa in the colonial period, but began to be rectified in the late 1950s and early 1960s when the majority of East, Central and West African countries achieved political independence. In southern Africa it was a different situation – the minority white governments were dissolved in Mozambique in 1975, in Zimbabwe (formerly Southern Rhodesia) in 1980 and in South Africa in 1994. The latter’s Bantu Education Act of 1953, a logical extension of apartheid policies of separate development, had stressed literacy and vocational training. The South African government saw no reason to encourage black artists to pursue academic study, but instead encouraged the development of ‘craft’ production in rural areas, because it fitted conveniently into a divide-and-rule Bantustans policy of emphasizing cultural distinctions among ethnic groups. But by establishing racially segregated residential areas, the government also created the conditions under which African township art would develop in the cities during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. In the townships, the informal workshop has been a vital aspect of art-making, and the place where black artists have developed not only their technical knowledge base, but also their consciousness of themselves as artists.

The most widely known of the early workshops was the Polly Street Centre in Johannesburg, which opened its doors in 1949 as part of a community centre programme for black township youth (see Chapter 4). Its success in training young artists in the 1950s and 1960s made it a model for other community centres, many of whose workshops were begun by Polly Street ‘graduates’. The term ‘workshop’ can mean several things – the Polly Street classes or sessions (and those following its model) were organized to take place weekly or twice weekly over an extended period of time, while the Ibadan and Osogbo workshops in Nigeria were annual, intensive two-week sessions and the Salisbury Workshop School in Rhodesia (see Chapter 4) went through continuous transformations over many years. Their common ground lay not in their periodicity or duration, but in the informal nature of the interaction between the participants and the organizers. This was not just an article of faith but a necessity, in that the artist-participants lacked the educational qualifications that might have gained them entry into more formally structured academic training. The workshops were goal-oriented, and in this sense resemble today’s cooperatives – they are about facture, not philosophy.

72 Dan Rakgoathe, Mystery of Space, 1975

The Swedish-sponsored Evangelical Lutheran Art and Craft Centre at Rorke’s Drift in rural KwaZulu-Natal was another important training centre for black South African artists, organized by Ulla and Peder Gowenius. It ran concurrently with Polly Street in the 1960s, but outran it, lasting into the early 1980s. If Polly Street resembled a workshop, Rorke’s Drift was more like a formal training school. Courses in pottery, textile design, weaving and fine arts were full-time and lasted two years, after which the student received a certificate. The fees, however, were very low, and anyone could apply, in keeping with the practical goal of providing students with the means of making a living. Rorke’s Drift’s most celebrated graduates have been printmakers, among them John Muafangejo, Cyprian Shilakoe, Dan Rakgoathe, Dumisani Mabaso and Lionel Davis.[72, 97] One of the key figures was Azaria Mbatha, who was not a graduate but one of the earliest teachers, and a strong influence on other graphic artists who passed through the school before he left to live in Sweden in 1970.[73] Though perhaps more ebullient and wedded to the use of text, Muafangejo’s linocuts, such as Zulu Land (1974), owe much to Mbatha in their compositional strategy, the grouping of figures and their narrative format.[74] By the 1980s, university art training was opening up to black students, and the fine arts section at Rorke’s Drift, which had been kept afloat financially by the more lucrative craft departments over the years, closed its doors.

73 Azaria Mbatha, The Greetings – Nativity, 1964

74 John Muafangejo, Zulu Land, 1974

Although the cultural setting could hardly be more different, many of the same issues first seen at Osogbo in the early 1960s were also at play in two workshops founded in the 1990s. The Kuru Art Project in Ghanzi District, Botswana, and the !Xun and Khwe Cultural Project of the Northern Cape, South Africa, were both started by South African artist and cultural worker Catharina Scheepers, with the aim of providing a means of artistic livelihood for displaced Nharo San, !Xun and Khwe-speaking people living on the edges of the cash economy.

The Kuru Development Trust, founded in 1986, grew out of the consolidation of several grassroots development projects started by churches in Botswana (Kuru is a Nharo word meaning ‘do it’). The Kuru Art Project, which combines elements of both a non-directive art workshop and a community self-help project, began in 1990 with a textile workshop for San women and was subsequently divided into a leather workshop, ‘crafts’ such as woodcarving and beadwork, a silkscreen fabric-printing workshop and the painting and printmaking group. Since then, the artists’ extraordinary creativity, coupled with the machinery of a well-run development project, has propelled them into the museum world, where they have exhibited in Poland, Finland, England, Germany (at Ulli Beier’s Bayreuth gallery at Iwalewahaus) and the USA, as well as in Botswana and South Africa. While at Rorke’s Drift and other rural workshop schemes the more traditional artisanal practices, such as leatherworking, have often remained gender-specific, at Kuru the painting and printmaking groups consist of both women and men.

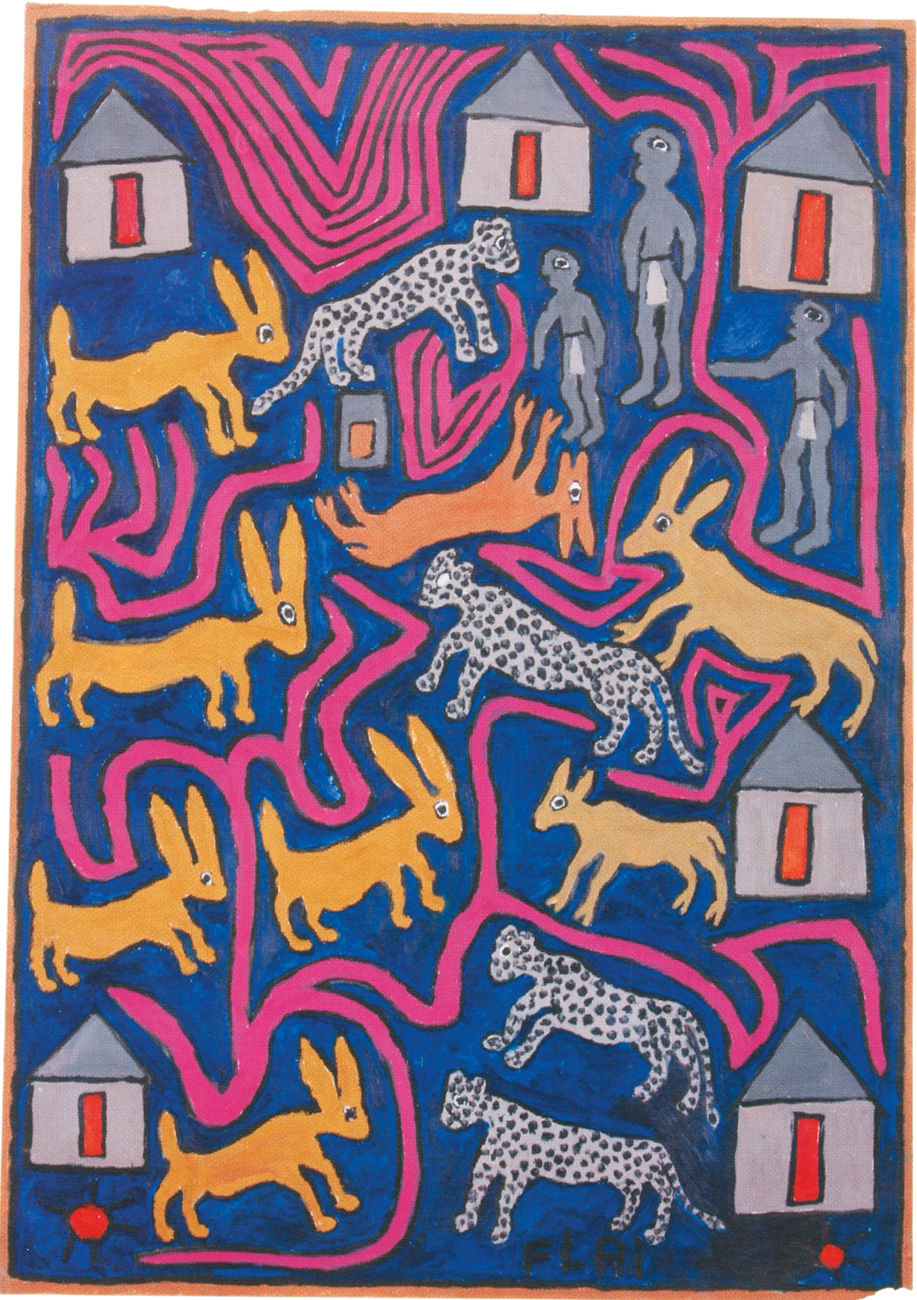

The work of some artists in the group is strongly reminiscent of rock painting, a traditional San artistic practice – not in subject matter or even style, but in the way the separate pictorial elements correspond to the varied surfaces they inhabit. There is often no imaginary ‘picture space’ other than this surface, and the choice of images resists easy analysis. One picture by Quaqhoo Xhare depicts skin bags and a tiger fish, objects with no obvious relationship to one another. Another work, by Thamae Setshogo, shows a dead tree and zebras. This apparent randomness is also found in the !Xun and Khwe work, such as Katala Fulai Shipipa’s The Leopard and the Hare (2005).[75] While outsiders attempt to unravel these images as symbols or create a narrative for them, they may be closer to a formal inventory of what is visible or imaginable to the artist. Researcher Jessica Stephenson adds:

Based on my interviews many of the works relate to folklore or what is called ‘the old story’ – which is related to values and times prior to what is called ‘the new story’ of the community when they worked for the military and then moved to South Africa. The ‘new story’ is associated with bad luck, ill health, social discord and sometimes blamed on acts of witchcraft. Artists paint ‘the old story’ in order to maintain its positive values for the health of their community.

75 Katala Fulai Shipipa, The Leopard and the Hare, 2005

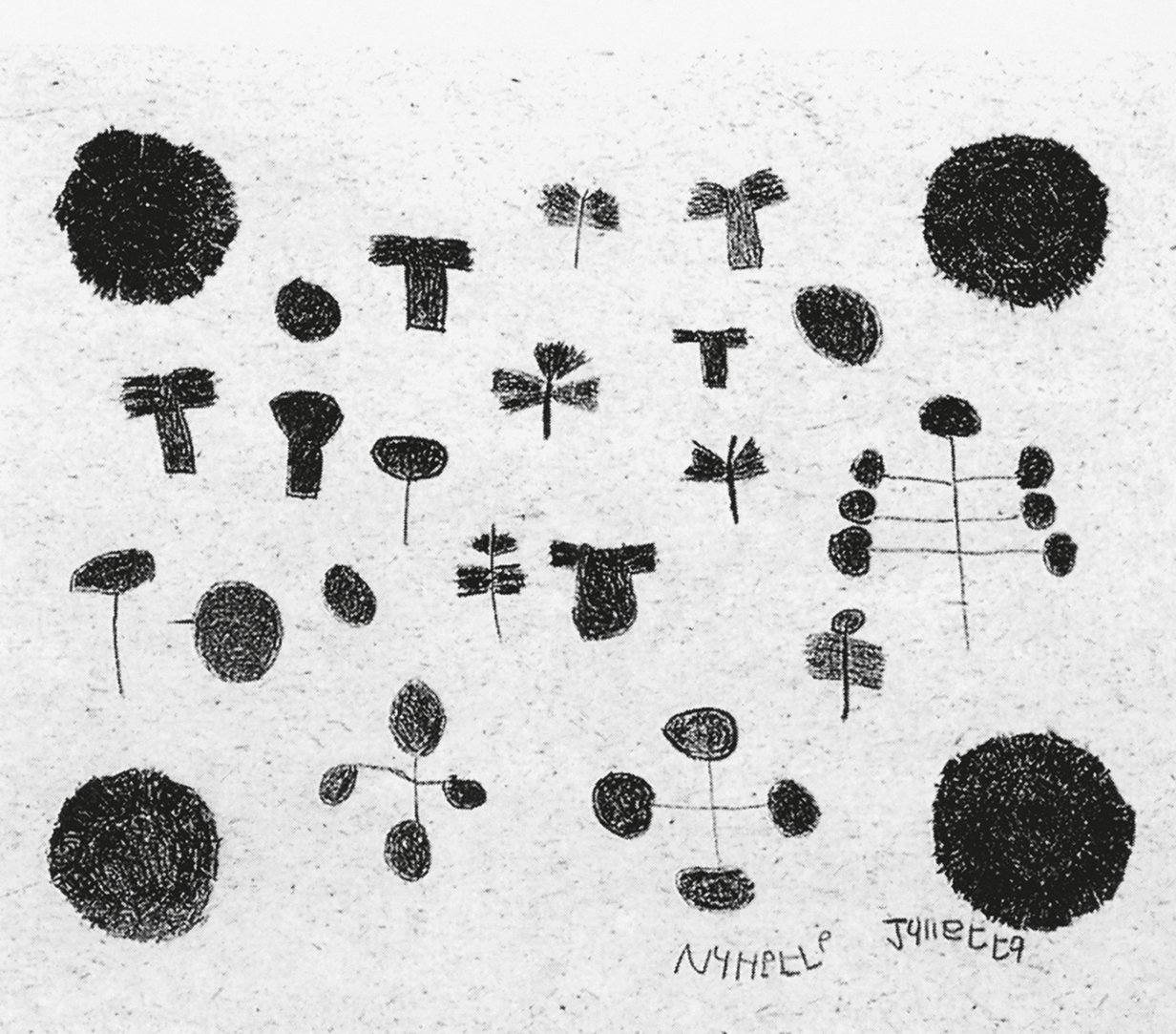

Despite similarities in the art itself, the !Xun and Khwe Cultural Project was founded to serve a rather different population to that of the Kuru Art Project. In 1990, after the end of the war for Namibian independence, the families of ex-South African Defence Force (SADF) soldiers and trackers had resettled at Schmidtsdrift, a South African army camp in the Northern Cape. They had previously lived in Namibia, and many in Angola before that, caught between the SWAPO guerrillas and the SADF. At Schmidtsdrift, art-making was used as both a community development strategy and a kind of therapy to counteract alcoholism and hopelessness. Army-camp life, as depicted in Thaulu Bernardo Rumao’s Tent Town (c. 1994), is rarely a subject of Schmidtsdrift pictures, but in some compositions the forms are drawn from experiences of conflict as well as from nature, creating startling juxtapositions such as that in Nests, Landmines and Plants (1995) by Julieta Calimbwe and Zurietta Dala.[76] The !Xun and Khwe living in Schmidtsdrift were eventually granted land based on their First Peoples status, and in 2003 were resettled in Platfontein.[77]

76 Thaulu Bernardo Rumao, Tent Town, c. 1994

77 Julieta Calimbwe and Zurietta Dala, Nests, Landmines and Plants, 1995

Partly because of the extreme poverty of the communities and their lack of experience in art-world dealings, the organizers initially took a protective stance towards the workshops, and played a supervisory role in presenting both the artists and their production to the public. While this was ostensibly to prevent the exploitation of the artists by unscrupulous outsiders, it also meant that the white organizers found themselves constructing and authenticating a ‘Bushman’ culture for the benefit of the rest of the world, including museums and institutions. By the early 2000s, the artists themselves were making use of this discourse, with certain elders censoring ‘modern’ subject matter because aspects of the ‘new story’ were associated with, for example, the negative effects of consumerism and alcoholism on the Bushman communities. The workshops therefore engaged not only in artistic production, but also in the production of a ‘Bushman culture’. A parallel, successful model for this exists in Southern African tourism, in which the Bushman is represented as living in close harmony with nature – although the reality is that many are hired workers on white farms or demobilized hired mercenaries. The power of the workshop organizers to frame both the art and its makers for global consumption and the problems this generates are considered in Chapter 5.