35 Jonathan A. Green, Oba Ovonramwen of Benin on board the SS Ivy on his way into exile, Bonny, Nigeria, 1897

The development of photography as a new medium, which began with the daguerreotype in 1839 and was followed by a series of technical improvements throughout the following three decades to 1871, coincided roughly with both the American Civil War and the European colonization of India and Africa, making these events landmark early subjects for the camera. It also coincided with important archaeological excavations in Egypt and Greece, which introduced ‘ruins tourism’ and an accompanying site-specific photography industry.

Also in this period, Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) stimulated a dialogue on natural selection that, while it was not Darwin’s intent, became a popular justification for the assumed racial superiority of Europeans over non-white colonized and enslaved populations. This in turn gave rise to a scientific interest in using photographic documentation to ‘prove’ these differences. A well-known example of this is the detailed photographic records and measurements of a group of seven male and female slaves in South Carolina, chosen from different places of African origin, compiled by Professor Louis Agassiz of Harvard. His motivation was to prove that Africans were not of the same physical species as white people, a theory known as polygenism, and that they were therefore not genetically entitled to the same individual freedoms.

What is evident from these few examples is that from its beginnings, the camera was far more than a neutral recording device. Whether romanticizing the subject (‘my trip to see the pyramids’) or dehumanizing the same (‘naked primitives carrying spears’), it appeared to solidify and prove some inescapable truth that mere discourse could not. Much later, theorists pointed out that the camera in fact presents only a fragment of reality, since it cannot reveal what lies outside the frame of the photograph. But in the early years, it seemed an unassailable kind of evidence to those who needed proof for their arguments.

35 Jonathan A. Green, Oba Ovonramwen of Benin on board the SS Ivy on his way into exile, Bonny, Nigeria, 1897

36 Camille Silvy, Sarah Forbes Bonetta (Sarah Davies), 15 September 1862

37 A.C. Gomes, Woman wearing leso and kanga, Zanzibar, c. 1890–1900

38 E.C. Dias or J.B. Coutinho, The famous slave trader, Tippu Tip, Zanzibar, c. 1890

The dominant early strands of African photography were either historical or scientific documentation, or in the case of elite portraiture a new mode of self-fashioning. The earliest photographic studios in the African colonies were most often begun by expatriate photographers, who were gradually supplanted by their African assistants as they learned the business and technology involved. Colonial governments and the individual administrators supplied much of the initial patronage, since photography was an efficient form of record-keeping as well as a way of creating personal memorabilia of ‘one’s time in the tropics.’

After 1858, all of these advances were simultaneously happening in India under the British Raj, with the result that, particularly in British East Africa, photographers migrated across the Indian Ocean and set up shop along the east African coast as well as in southern Africa.

Many of these were migrants from Goa, an old Portuguese colony on the coast of India, where the British navy had kept their fleet. A capacious view of African photography must include these Goan former immigrants, who were among the best-known portrait photographers in Africa even long after the end of colonialism. It also must include several white photographers in multiracial South Africa, both during the apartheid era and after.

The first strand, that of documentation, was initially a colonial governmental practice. Beginning in the 1950s, this developed into what is now modern photojournalism, shown most prominently in publications such as African Drum, a popular magazine with editions published in Lagos, Johannesburg and Nairobi. The South African edition in particular was the training ground for a number of highly skilled photographers, who documented everyday life as well as political violence in the segregated townships.[39, 40] Documentary photographers Alf Kumalo, Ian Berry and Jürgen Schadeberg, the latter its photography editor, all built their reputations through Drum, in which they recorded a visual history of apartheid and its many unguarded moments.

39 Alf Kumalo, Political Unrest, Soweto, 1976

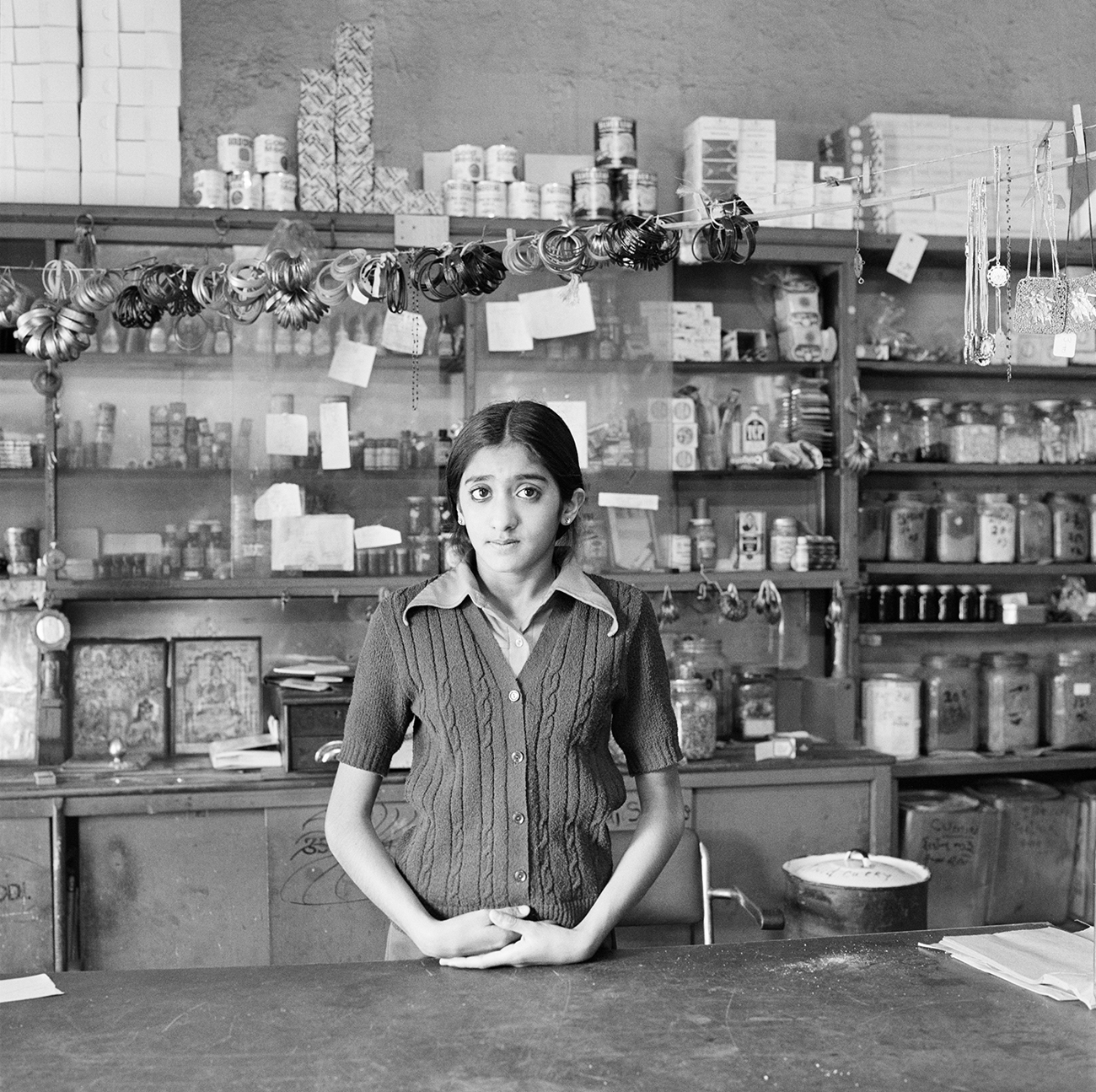

There is no sharp division between photojournalism and portraiture in South Africa; one can segue into the other when the photographer’s intentions change. For example, David Goldblatt’s depiction of a young girl, Yaksha Modi, in her father’s shop only reveals its full meaning through the second half of its title: Yaksha Modi, daughter of Chagan Modi, in her father's shop before its destruction under the Group Areas Act, 1976.[41] Without its full title it succeeds equally as a portrait of a young girl in a darkened interior, surrounded by the goods she sells. Goldblatt (1930–2018), a white South African, worked very effectively in both modes in his long career – for example in his series about sleeping commuters on an overnight bus, ‘The Transported of KwaNdebele’ (1984). These workers, forced to commute back and forth from their ‘tribal homeland’ daily in order to work for employers in white-only areas, spent up to eight hours a day on the bus. The photographer adopted the same blurred, out-of-focus reality as the exhausted workers themselves were made to feel, in order to convey the futility and arbitrary cruelty of apartheid regulations.

Santu Mofokeng (b. 1956) started a generation later than the Drum photographers or Goldblatt, first as a teenage street photographer and then a darkroom assistant.[42] He joined the photographers’ collective Afrapix in 1985, documenting life under apartheid, and in 1988 became part of the technical staff at the University of Witwatersrand. Dissatisfied with the strictures of photojournalism, in the late 1980s he began the transition from reportage to art photography and was able to acquire professional training in New York when, in 1991, he won an Ernest Cole Scholarship for study at the International Center of Photography. His post-New York work is strikingly different from most African photography of the time. It departs from portraiture and reportage in favour of often-enigmatic landscapes or locations such as the ruins of a WC in the Skeleton Coast of the Namibian desert, or the death train at Auschwitz, Poland, from which he snapped his own window reflection. He has also chosen to engage with historical portrait photographs, as shown in his 1997 project ‘Black Photo Album: Look at Me, 1890–1950’. This ‘album’ is a collection and re-presentation of photographers’ studio portraits from the pre-apartheid era; in other words, a record of how black South Africans wished to see themselves represented in the days before their lives were imprisoned in an intricate set of rules.

40 Ian Berry, Multi-racial Café with Jukebox, 1961

41 David Goldblatt, Yaksha Modi, daughter of Chagan Modi, in her father’s shop before its destruction under the Group Areas Act, 17th Street, Fietas, Johannesburg, 1976

42 Santu Mofokeng, Out-house of a soft drink and beer stall, Namibia, 1999

Slightly younger than Santu Mofokeng, Guy Tillim (b. 1962) also began his career with Afrapix, before he expanded his coverage of violence to African countries beyond his native South Africa. A memorable example is his 2002 series on teenage soldiers in the Congo, which captures the individuality of people normally envisioned as a faceless mass.[43]

In his exhibition catalogue Snap Judgments (2006), Okwui Enwezor spoke of two kinds of interest in African photography: the curatorial (including his own) and the anthropological. To put it this way is to shift the discussion subtly from the photographers to those who interpret and present their work, a different though interesting topic. While anthropological interest in African photography came earlier and is ongoing, albeit much more reflexively than in the past, curatorial interest is more recent, and is increasingly concerned with what Enwezor termed personal narrative and aesthetics. For this, he cites the work of David Goldblatt, Santu Mofokeng and Zwelethu Mthethwa (b. 1960), the youngest of the three.

Mthethwa studied at the Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town, from 1981 to 1984, by special dispensation; at the time, it was still an all-white university. His work embodies a non-traditional conception of African portrait photography, moving away from the artifice of the studio to show subjects at home or in their workplace.[44] Equally important is his choice of subjects themselves, who are typically everyday township dwellers or workers shown in their place of labour. An important precursor in both respects seems to be David Goldblatt’s earlier work on the lives of ordinary Afrikaners (‘Some Afrikaners Photographed’, 1975). The subjects look directly at the camera, their expressions suggesting that there is a prior understanding with the photographer that he respects them and their surroundings – not as an anthropologist or even a photojournalist, but as one who finds them and their lives admirable subjects, worthy of his attention. Importantly, Mthethwa works in colour, not black and white like most of his predecessors, which imparts a strong sense of contemporaneity rather than the feeling of timelessness in many of the earlier photographs.

43 Guy Tillim, Mai Mai Militia in Training for Deployment, DRC, 2002

Looking at the South African work discussed raises the question of whether there are recognizable national schools and not just something called ‘African’ photography. And if so, are these styles or are they genres? Do they come out of local journalistic or overseas training? Or, in South Africa’s case, are they responses to the overwhelming social presence dictated by the apartheid state? Whether one or all of the above, South African photography seems to have fragmented into different streams after 1994, which not only saw the end of apartheid policy itself but also the African National Congress’s official socialist ideology of ‘the artist as cultural worker’ and ‘art as a weapon of struggle’. In his position paper ‘Preparing Ourselves For Freedom’ (1990), the ANC theorist Albie Sachs, writing in anticipation of the ANC’s victory in the 1994 election, proposed that ‘black is beautiful, white is beautiful, brown is beautiful’ and from then on, artists should be free to express their agency in any way they chose. Although controversial at first, this fractured the somewhat narrow framework in which many artists had felt morally constrained until that time.

44 Zwelethu Mthethwa, Untitled, 2003

In late-1940s Bamako, Seydou Keïta (1921–2001) set up a photo studio to cater to burgeoning public interest in all forms of print media, including being photographed while looking one’s best. Working at first in the family business as a cabinet-maker, in 1935 Keïta received a Kodak Brownie from his favourite uncle and began snapping people at their request. Two of his old cabinet-making apprentices helped him to advertise by bringing samples of his work to the railway station. In the mid-1940s he purchased a 6 × 9 box camera, and in 1949 switched to the 13 × 18 in. format that became his signature.

Photography differs from painting or drawing in the precision of the medium; it makes strict technical demands that dictate the artist’s approach to the work. When talking about his studio portraits, Keïta dated them according to which cloth backdrop he was using that year – flowers, leaves, arabesques. He noted that in late 1940s Bamako, men began wearing European clothes to dress up, while for women these changes didn’t become common until the 1960s.[10] Women instead came to the studio dressed in their best robes, accompanied by a collection of their gold, coral and amber jewelry.[45] This gave rise to Keïta’s practice of posing them reclining on one side with an elbow propping up the head – a pose men would never consent to take (see p. 50).[34] This pose allowed him to spread out the voluminous robe’s pattern to its best advantage and use the jewelry as a focal point. While there is no question that Keïta’s photographs document real people from 1940s and 1950s Mali, by his own description he always tried to make the subject look as good as possible – a statement true of most portrait photography up to the present. This raises the ambiguity of just what is meant by ‘the truth of the camera’.

45 Seydou Keïta, Untitled portrait, Bamako, 1956–60

The Senegalese photographer Boubacar Touré Mandémory (b. 1956) discussed both portraiture and documentary work with Austrian curator Gerald Matt at Kunsthalle Vienna in 2001. In the beginning, he said, a photograph was always a portrait: ‘…reportage as we know it today is a relatively recent phenomenon in Africa. The French arranged for photographic services in the fifties and the Information Ministry at the time tried to re-train the portrait photographers into reporters with a camera. But this scheme never quite succeeded…[however] I do not believe that a confrontation between “unreal” studio photography and “authentic” documentation is meaningful. Even Keïta’s photographs contain chunks of reality.’

If photographers cannot, in theory, avoid the truth of the camera, they can nonetheless create more than one version of it. Keïta explained the ways in which he implemented his customers’ dreams of wealth, beauty and modernity matter-of-factly to the French gallerist André Magnin: the suits he kept for men, the spectacles, wristwatches and even a new motorbike used as studio props to fulfill their wishes without detracting from them as human subjects. For women, the suggestion of wealth and beauty came not from props but from Keïta’s elegant poses and strict standards of perfection, combined with their own or family-owned jewels and gowns.

Wealth and modernity are visualized and portrayed very differently depending on time and place. Roughly a generation later than Keïta, in Ghana, Philip Kwame Apagya (b. 1958) developed a technique in which he created an entire painted stage set of aspirational modern life, among which the subject is posed almost like a paper cutout.[46] The effect is poster-like, both in the use of flat colours and the relation of subject and ground. If the aesthetic reference point for Keïta’s subtle glamour was the black and white cinema of the 1940s, then Apagya’s was the much more immediate, glossy full-colour advertising poster or magazine cover.

46 Philip Kwame Apagya, Auntie Monica’s Bathroom, 2000

47 Sammy Big 7 Studio, Double portrait with lion and the Titanic, Likoni, Kenya, 1999

However aesthetically different they may have been, both of these styles were a part of the unstoppable flow of modernity and consumer culture that became a part of Africa’s urban scene under European colonization, and came to stand for worldly success. But the photographers largely saw themselves as skilled craftsmen performing a highly desirable service for their customers. The idea that photography was an art form or a means of self-realization was foreign to the studio setting, which was framed as a business transaction. It is sometimes hard to retain this sense of context once a photographer’s work has been subjected to the ‘gallery effect’ and is written about and collected. As John Peffer has observed, this separation of local photographers from their clients through public recognition magnifies their art-world singularity and at the same time reduces the importance of the client. In much the same way, printing, matting and framing inside a white-cube gallery transforms the effect of a photograph when compared to its appearance on a page in a domestic family album.

The fantasy world of studio props need not relate to actual aspirations, such as Apagya’s bathrooms: it can be intermedial, consisting of fantasies taken from film (images of the sinking Titanic), television news (the attack on the World Trade Center), the tourist trade (big-game hunting in Kenya) or even the latest clothing fashions from the USA.[47] Heike Behrend describes one enterprising young Kenyan who had a relative in the USA send him the current hip-hop fashions; the photographer and his American relative were reimbursed by the sale of both the clothes and photographs of customers wearing them. Behrend calls this transaction a ‘migrant archive’: it serves as reassurance to the family back home in the countryside that their absent relative is successful and cosmopolitan, even when the opposite may be true. In Kenya, secondary schools sponsor regional and countrywide group singing competitions, and photographers are present at the award ceremonies to memorialize the participants. Here, too, images of the Titanic or airplanes compete with big game.

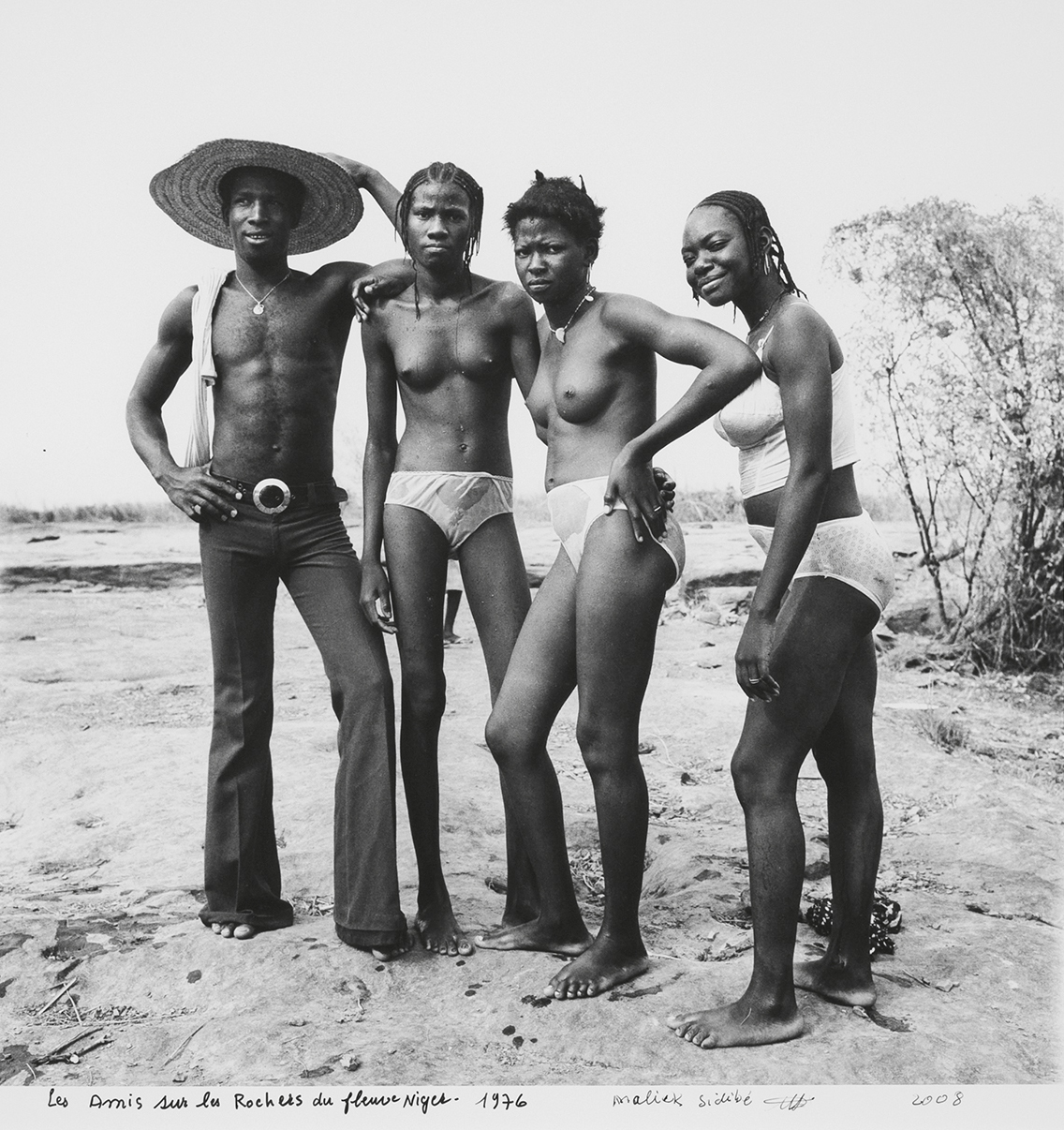

Seydou Keïta’s work represented a high point in black and white studio technique, and the realization of a cultural ideal. When the focus began to move out of the studio and into the streets and clubs and beaches, new genres of photography emerged: a novel kind of social realism encompassing youth culture and the lives of those living outside the social contract, such as the homeless and the insane. Malick Sidibé (1935–2016), a fellow Malian half a generation younger than Keïta, had a very different idea of what the camera could do. He was interested in depicting teenagers hanging out in their favourite spaces, rather than matrons with their jewels and staged family studio portraits.

48 Malick Sidibé, Les Amis sur les rochers au bord de fleuve Niger (Friends on the Beach of the River Niger), 1976

This diametrically opposite choice of subject made the brash ‘wannabe’ modernity of the younger generation the new centre of attention. Instead of married women dressed in capacious gowns and laden with expensive jewelry, it was teenage girls posing on the bank of the Niger, clad in bathing suits or underwear, who seemed to inhabit a different universe.[48] This new genre also included the club scenes of young people performing popular imported dances that became Sidibé’s signature. In 1999, Deitch Projects gallery in New York exhibited a sculptural version of one of Sidibé’s dancers in a room-size installation called, like the original photograph, Clubs of Bamako, thus elevating Sidibé to the embodiment of modernity in early post-independence photography.

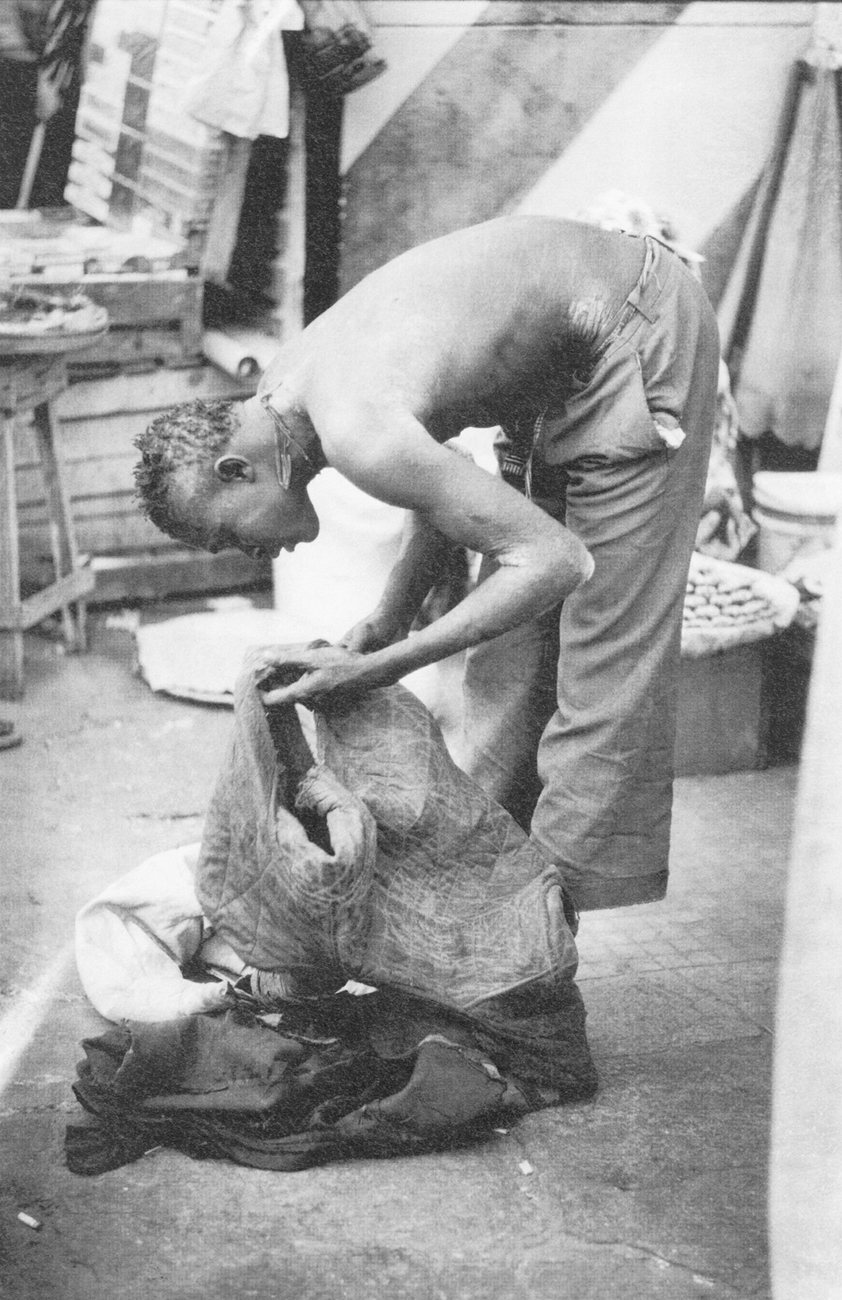

The obverse of the social realism coin was developed by a subsequent generation of photographers in Dakar and Abidjan. Bouna Medoune Seye (1956–2017) began to photograph street people on the sidewalks of Dakar in the 1990s, not as a form of updated photojournalism or ‘relational aesthetics’ but as socially engaged portraiture.[49] Born in Abidjan ten years later, Dorris Haron Kasco first became known for his series ‘Les fous d’Abidjan’ (The insane of Abidjan), which was created over a three-year period from 1990 to 1993. It also includes images of street children, whom Kasco says he befriended, unlike the ‘insane’, with whom the encounters were more one-sided.[50] In either case, he said, ‘If I take photographs of children or crazy people, then this is not a marketable commodity [unlike studio portraits]…I also had to make a living during this time and of course I did a great deal of commercial work to order: advertisements, fashion photography, and the like.’ It is an important reminder that, like the Nigerian fashion designer I know who makes and sells elaborate wedding cakes on the side, few African photographers, painters or other creative people live exclusively on the income from their formally exhibited work.

Popular photo studios along the East African coast arrived early in the twentieth century, with Goan immigrants who still inhabit a niche now dominated by indigenous Kenyans. But photography as an experimental art form has a much more recent genealogy in the region, stemming from increased use of digital technology. One member of this generation of young artists is Rumanzi Canon Griffin, a Kampala-based photographer and painter who shows his work on social media sites such as Instagram, Flickr, Tumblr and Facebook as well as in galleries.[51] In his Among the Mums of Earth, a panoptic view of some of the city centre’s most recognizable buildings hovers in the sky above an ordinary Kampala street scene. Griffin is also interested in the politically subversive and uses images made from election posters of politicians, including a series he shared on Instagram, tagged #politicianeyes (let me help you lead you) to suggest that the eyes reveal their owners’ hidden intentions. I met Griffin at the Nommo Gallery during the 2016 Kampala Bienniale, where he was dressed, despite the tropical climate, in an old-fashioned formal black suit and hat, like a visiting clergyman. But his interviews with Robertson suggest a very different person – one who would like to ‘make lots of money’, be ‘a big-shot artist’, ‘eat lots of steak’, ‘get a Nissan pickup’ – in other words, the same material things that many young strivers might want.

49 Bouna Medoune Seye, Les trottoirs de Dakar (The streets of Dakar), 1994

50 Dorris Haron Kasco, Les fous d’Abidjan (The insane of Abidjan), 1990–93

James Muriuki (b. 1977), a Nairobi-based artist, has already been ‘discovered’ by international curators. He has entered the artist residency circuit and exhibited abroad, in places such as Iwalewahaus in Bayreuth, and as a result his work displays less one-off experimentation than Griffin’s. It is more project-focused – for example on construction sites, buildings in various stages of completion, tools and workers. One such project, resulting from a residency at the Delfina Foundation in London, involves the international politics of food, while another saw Muriuki and a fellow artist set up a mock ‘popular’ portrait studio on the Kenya coast at Kilifi, employing the props of a doctor’s office.[52] Nairobi, his hometown and a churning metropolis, is still his sustaining interest.

Further south, in Mozambique, Rui Assubuji (b. 1964) began his career as a cameraman for national television and started to take stills in 1985. He has since had a tripartite career as a photographer, curator and PhD student at University of Western Cape, South Africa, where he researched the visual history of Portuguese colonialism between 1850 and 1930 using photographic archives. Assubuji lives and works in Maputo and has returned to Cabo Delgado, his birthplace, with visual anthropologist Paolo Israel in order to document the famous Makonde mapiko masquerade. In addition, he has produced a powerful series of images of syncretic religious ceremonies.[53]

51 Rumanzi Canon Griffin, Among The Mums of Earth, 2016. This abstract digital image of Kampala was exhibited as part of ‘The Unseen’ group exhibition at Afriart Gallery, Kampala, 2016.

52 James Muriuki, Matatus II, from the ‘Town’ series, 2005

53 Rui Assubuji, Mama Eva prays for a better life. Igreja Mazione – Maputo, Mozambique, 2005

The remainder of this chapter deals with photographers of African parentage who now live and work in Europe or the USA. When they return to Africa as their subject, it is as insider-outsiders, more or less the reverse of photographers such as Santu Mofokeng and Guy Tillim who travel outside their country to take pictures but still consider South Africa their home base. This presents itself as a problem of classification – which place do these artists identify with? – but also of what kind of work they engage in. In addition, which Africa are we, or they, talking about? Not the old ‘tribal map’, which consisted only of those places in equatorial Africa that had masks or figure sculpture. The past still figures strongly in the work of many of these artists – just not that particular past.

North Africa, despite its different art history, is now generally considered by curators and scholars to be a part of the contemporary African art map. This glosses over the fact that it also has its own cultural identity as part of the Arabic-speaking contemporary art world, which has its own infrastructure of exhibitions, conferences, artists and visual culture. Politically, that dual identity has always existed, and at present all North African countries belong to the Arab League as well as the African Union. But immigration both in and out of North Africa has blurred all these boundaries.

54 Lalla Essaydi, Les femmes du Maroc: Grande odalisque, 2008

Lalla Essaydi, born in Marrakesh in 1956 and trained in Paris and Boston, is a New York-based artist. Despite her cosmopolitan background, she has chosen to portray Moroccan women in a harem setting, in work which is intentionally Orientalist in style but overwritten in Arabic calligraphy and other signage using henna, a traditional form of female body painting.[54] Henna is both a deeply religious substance – the Prophet dyed his beard with it – and an aesthetic statement made by and for women. Essaydi has used the odalisque pose and calligraphic signage to express both bondage and ambiguity. As a modern woman living in New York City but preoccupied with these themes she is the exemplary insider-outsider, commenting from a geographic and historical distance but nonetheless recognizing the complexity of Moroccan gender norms as framed by both cultural outsiders and Moroccan women themselves.

Zineb Sedira, born in Paris in 1963 to Algerian parents and trained and working in London, is another North African artist whose earlier work was focused on the issue of her own subjectivity. Her 2002 short film Mother Tongue featured her Algerian mother, her British daughter and herself, a French citizen, as a reflection of the multiple layers in her identity. Later, she became absorbed by the subject of memory and its physical containers, including places such as shipwrecks and empty buildings.[55]

55 Zineb Sedira, The Lovers, 2008

Samta Benyahia, born in Algeria in 1950, trained at the École Nationale Supériere des Arts Décoratifs in Paris and taught in Algiers for eight years before returning to Paris, where she now lives and works. She has exhibited widely, including at the Venice Biennale in 2003 and the Dak’Art Biennale in 2004. Though she is a fine photographer, she is best known for her installations of openwork screens, which are used in Islamic architecture to cover the windows and balconies behind which women may see but not be seen.

Nabil Boutros was born in Cairo in 1954 and moved to Paris as a teenager. He lives and works in both cities, but his subjects are principally Egyptian, taking in a wide variety of contexts such as the ceremonies and lives of Coptic Christians, Cairo’s small traditional shops and its elderly inhabitants.[56] Boutros also works as a photojournalist, covering news events and the funerals of important people and taking pictures of politicians; in some senses, he is less intensely focused than either Sedira or Essaydi. Nonetheless, all four of these North African artists, born in the 1950s or early 1960s, situate their work within the broad parameters of the culture they came from and not in the Western cities where they have spent much of their lives.

Other photographers of this generation have turned their gaze inwards. Two well-known photographers, Samuel Fosso and Iké Udé, both born in the 1960s, use themselves as models, often cross-dressing and giving themselves theatrical, pop-culture or historical identities – but their methods and audiences are different.[57] At the beginning of his career, Fosso, who was born in Cameroon but works mainly in Bangui, Central African Republic, ran a portrait studio by day and took pictures of himself at night with any leftover film. He would send these pictures to his family in Nigeria. He developed increasingly elaborate costumes and personae, and these self-portraits became his signature style. In 1994 he was discovered by a talent scout for the first Bamako Biennale, and since then he has won international prizes (Rencontres de la Photographie, Bamako, 1994; Dak’Art Biennale, 2000) and recognition, including his 2007 Bamako retrospective. It was a visit to Paris to accept the Bamako prize in that stimulated his series of self-portraits in various genders and roles, which was commissioned by the Paris department store Tati in 1997.

56a Nabil Boutros, Good Friday, Vendredi Saint (detail) 1997–2004

56b Nabil Boutros, Good Friday, Vendredi Saint, polyptych, 1997–2004

57 Samuel Fosso, Autoportrait, from the ‘70's Lifestyle’ series, 1975–78

Iké Udé, born to a wealthy family in Lagos, was able to follow the elite path of attending college in New York instead of starting as a photographer’s assistant as Fosso did. He witnessed firsthand the ups and downs of postmodernism, as well as urban anglophone culture in the form of print media aimed at the socially ambitious. Vogue, GQ, Harper’s Bazaar, Cigar Aficionado and similar titles stimulated a series of photographs called ‘Covergirls’, in which Udé, in various disguises, placed himself on mocked-up magazine covers. These images play with gender and traditional ideas of masculinity and femininity, achieved using make-up and carefully chosen clothing.[58]

58 Iké Udé, GQ cover in ‘Covergirls’ series, 1994

Udé’s use of self-portraiture made possible his promotion of the artist as celebrity, in much the same way as Andy Warhol had done twenty years earlier. To this end, he also began to publish aRUDE magazine, which is now an online publication, in the mid-1990s. As they became well-known, both Fosso and Udé transitioned to a directorial role as the head of a team of assistants, retaining authorship of their photographs but not the technical work needed to make them happen. In this they resemble many other successful artists, of course, though they work in very different settings from one another.

Otobong Nkanga, born in 1974 in Kano, Nigeria, studied art in Amsterdam and now lives in Antwerp.[59] Her recent work is caught up in issues of earth, materiality and memory, and she has spoken of watching her mother make black (palm-oil) soap and dye cloth with indigo, both familiar Nigerian practices which suddenly came back to her when she began thinking about materiality. She has said that this experience made her realize that it is physical smells – indigo dye, palm oil being boiled – that are the containers of memories.

Moving southeast, from Nigeria to the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sammy Baloji, born in 1978 and now living and working between his hometown of Lubumbashi and Brussels, is probably the African photographer most discussed in the USA in recent years. This prominence is due largely to his exhibition ‘The Beautiful Time’, curated by Bogumil Jewsiewicki and shown first at the Museum for African Art (now the Africa Center) in New York in 2010 and subsequently at the Smithsonian Museum’s Focus Gallery in Washington DC in 2012. Baloji was already widely known in Europe, Japan and Morocco for an earlier exhibition, ‘Memoire’, which began in 2006 and documented the Union Minière du Haut Katanga (Mining Union of Upper Katanga) using a mixture of video and photographs. The huge colonial enterprise, founded in 1906 to mine copper, is now part of the postcolonial detritus of failed modernization in the DRC.

The sometimes shocking juxtapositions in his photomontages were created by superimposing archival photos of mine workers or their Belgian supervisors on top of recent photographs, taken by Baloji, of the abandoned copper-mining sites with now silent machinery.[60] In one, the Congolese dictator Mobutu Sese Seko is shown inspecting a mine. There are two villains here – not only the colonists’ exploitation of Congolese workers, but also the failure, through mismanagement and corruption, of the postcolonial government to sustain a successful modernization project developed by the colonizers. His most recent project is the 2016 book Suturing the City: Living Together in Congo’s Urban Worlds, and the related exhibition ‘Urban Now: City Life in Congo’, both in collaboration with the anthropologist Filip de Boeck. Asked why he would want to live in Brussels if his work is a critique of colonialism, Baloji says: ‘To me it’s enriching to live in Congo [Lubumbashi] on the one hand and stay in the heartland of the old colonial power on the other. Distance always creates clarity.’

59 Otobong Nkanga, Working Men II, 2005

60 Sammy Baloji, Untitled 25, from the ‘Memoire’ series. Imagery of a present-day copper mining site is overlaid with a 1960s archival image of President Mobutu Sese Seko and companions.

On the other side of the border, Kilembe, Uganda, was also once a thriving copper-mining town. Uganda and the DRC share many cultural features and historical realities, even with their different colonialisms, Belgian versus British. In the first postcolonial decade, each was taken over by an infamous dictator – Mobutu in the Congo (then Zaire) and Idi Amin in Uganda. Beginning in 1972, Amin ordered the deportation of all ‘Asians’ (Indians and Pakistanis, many of them citizens) from Uganda, so that he could ‘Africanize’ their businesses – i.e. so that his Uganda Army cronies could take over. At that time Asians formed most of the small business class in Uganda, economically sandwiched between colonized Africans and British colonizers and often held in contempt by both.

Zarina Bhimji (b. 1963) moved to the UK in 1974, and went on to train successively at Leicester Polytechnic, Goldsmiths College and in mixed media at the Slade, afterwards turning to photography, film and installation.[61] In 1996, the major Guggenheim Museum exhibition ‘In/sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present’ included several photographic light-boxes by Bhimji, which had been commissioned by the Public Art Development Trust, UK, for display at Charing Cross hospital. The works fell into two groups: four documentary-style photographs from the hospital’s pathology museum, which were displayed in the Teaching Laboratory and seen only by medics and students, and four still lifes, installed in the public area of the hospital. The titles of the works were matched, connecting the two groups.

61 Zarina Bhimji, Here was Uganda, as if in the vastness of India, 1999

Bhimji has the ability to invest inanimate objects with great emotion. In 2001, a very different series of her photographs, taken in Uganda, was included in ‘The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1945–1994.’ The Love series investigates architecture, emotion, light and space through the pictured dwellings. In 2007, Bhimji was shortlisted for the coveted Turner Prize for the photographs, of which she said ‘It is important the work expresses beauty and tenderness. The spaces have a special atmosphere and the space around it has an intense beauty.’

The Love photographs also formed the proposal for Bhimji’s 16mm film Out of Blue, with which she participated in Documenta11 in 2002. Her reputation was spread significantly by inclusion in these three major exhibitions, all curated by Okwui Enwezor, which also verified her art-world identification as an African artist, reiterating the capacious definition now allowed by many in the curatorial world (see pp. 7–8).

I end this chapter with a Kenyan artist who migrated to California. Allan deSouza (b. 1958) was, like Bhimji, born to East African Asian parents before moving to the UK; he too attended Goldsmiths College, but after the 1980s, their career paths diverged. In 1992, deSouza left the UK for the USA to participate in the highly competitive Whitney Independent Study Program in New York. He then went to California and completed an MFA degree in photography at UCLA. DeSouza is a writer as well as an artist, and his intellectual gifts as well as his sheer originality as an artist have qualified him for an academic as well as photographic career. His work deals with migration, loss and memory, often tinged with humour and irony, as in the image of a glittery electronic strip-club entrance juxtaposed with the political graffiti next door, which reads ‘if at first you don’t succeed – call an airstrike’.[62]

62 Allan deSouza, Garden of Eden, from ‘The World Series’, 2011