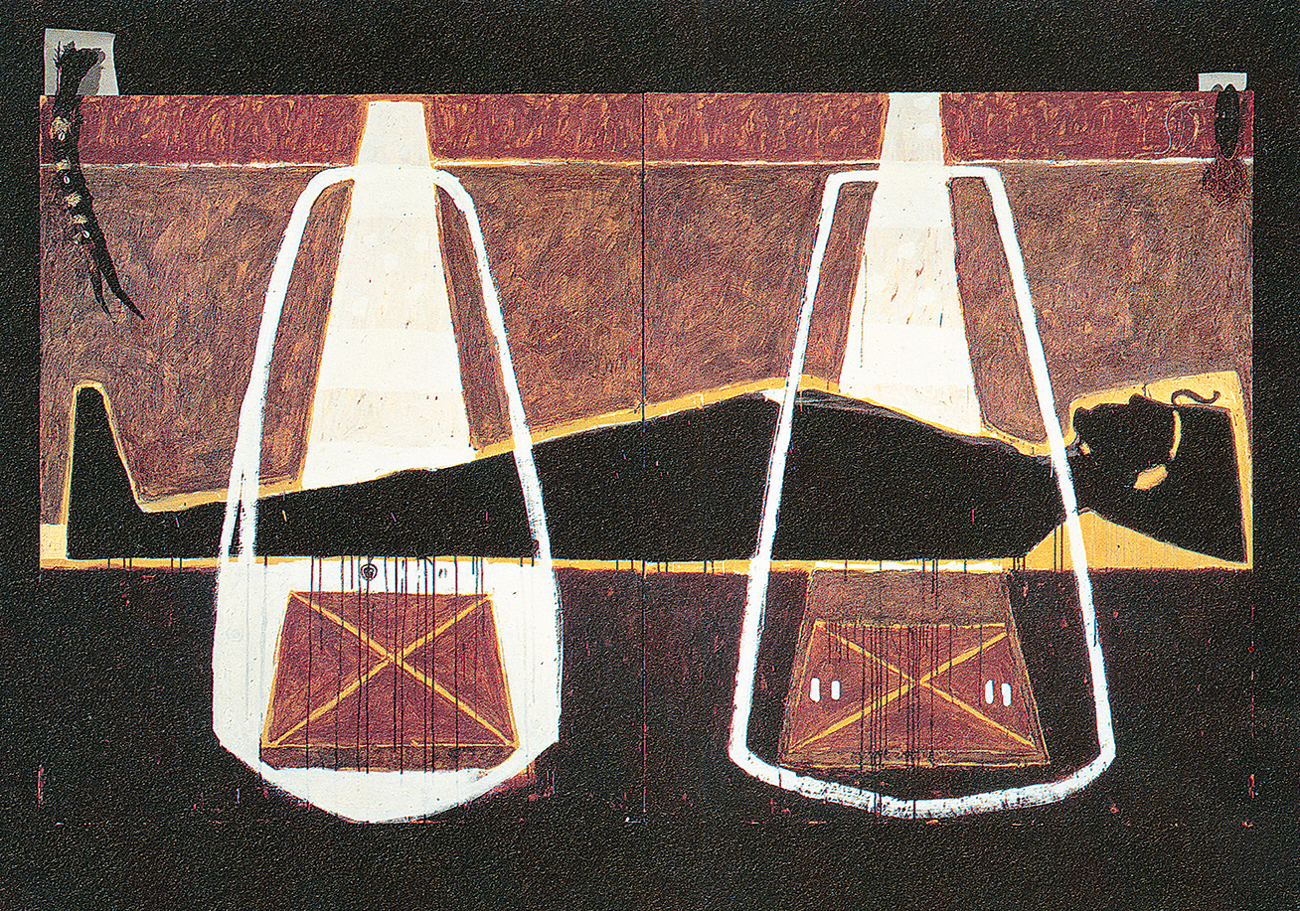

186 Skunder (Alexander) Boghossian, Climatic Effects, 1984–85

The condition of displacement or exile for African artists is not simply the reverse of the romantic impulse that has propelled certain Western artists out of their own milieu into a more ‘exotic’ one, but has often been a response to debilitating political repression or economic chaos at home. These journeys have in fact only been possible for a small minority – fluency in an international language, recognized paper qualifications, enough money to travel and a network of crucial contacts abroad all define who is able to travel. Most paths have led to the former colonial metropole or another country in the same language sphere. And overwhelmingly, it has been university-trained artist-intellectuals rather than untutored artists who have either settled permanently or spent substantial periods outside their own countries. Everything about their lives and careers has better prepared them to survive in a wider world than, say, the Kuru artists of rural Botswana or street painters in Lubumbashi.

The creation of conditions of exile has had two major historical thrusts, one fed by late-colonial education following the Second World War and the other by political and economic crises following the transition to independence in the 1960s. The inadequacy of art schooling was initially responsible for a small cadre of extraordinary African artists – mainly born in the 1930s and 1940s – being sent to training institutions in the colonial capitals: the Slade School of Fine Art in London, the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and several other European academies. The postcolonial migration that came later due to political instability and economic decline has affected certain African countries much more starkly than others. A few of the artists involved had initially travelled abroad as students, enabling them to develop contacts in the West and to serve later as contacts themselves for their counterparts still in Africa. Aside from those in London and Paris, one particularly cohesive group of artist-emigrés has been Ethiopian artists in the USA, while a more recent diaspora has been formed there by Nigerian artists. They have clustered in and around universities as postgraduate students and later, as teachers, and a new vocational space has emerged since 1990 for African intellectuals outside the university, as freelance critics and curators.

The experience of exile forces the individual to confront a new identity. Yet some migratory artists remain firmly or tenuously attached to their former local, national or regional identities and traditions all their lives. As the South African writer Njabulo S. Ndebele has observed, his overseas experience in the UK and the USA afforded him ‘a necessary distancing from South Africa. This, paradoxically, served as means of recall, of retaining a kind of distilled memory.’ In a similar comment, the Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi remarked, ‘the locality of one’s own home becomes almost a past dream, very, very dear. You have a longing for it, nostalgia, as if it were something from a distant past.’ But on a more pragmatic level, ‘When I was growing up I thought that England, France, the Philippines were on some remote periphery of Khartoum, which was at the centre of everything. But as I moved out to London [to attend the Slade], my new home then became the centre of the world.’

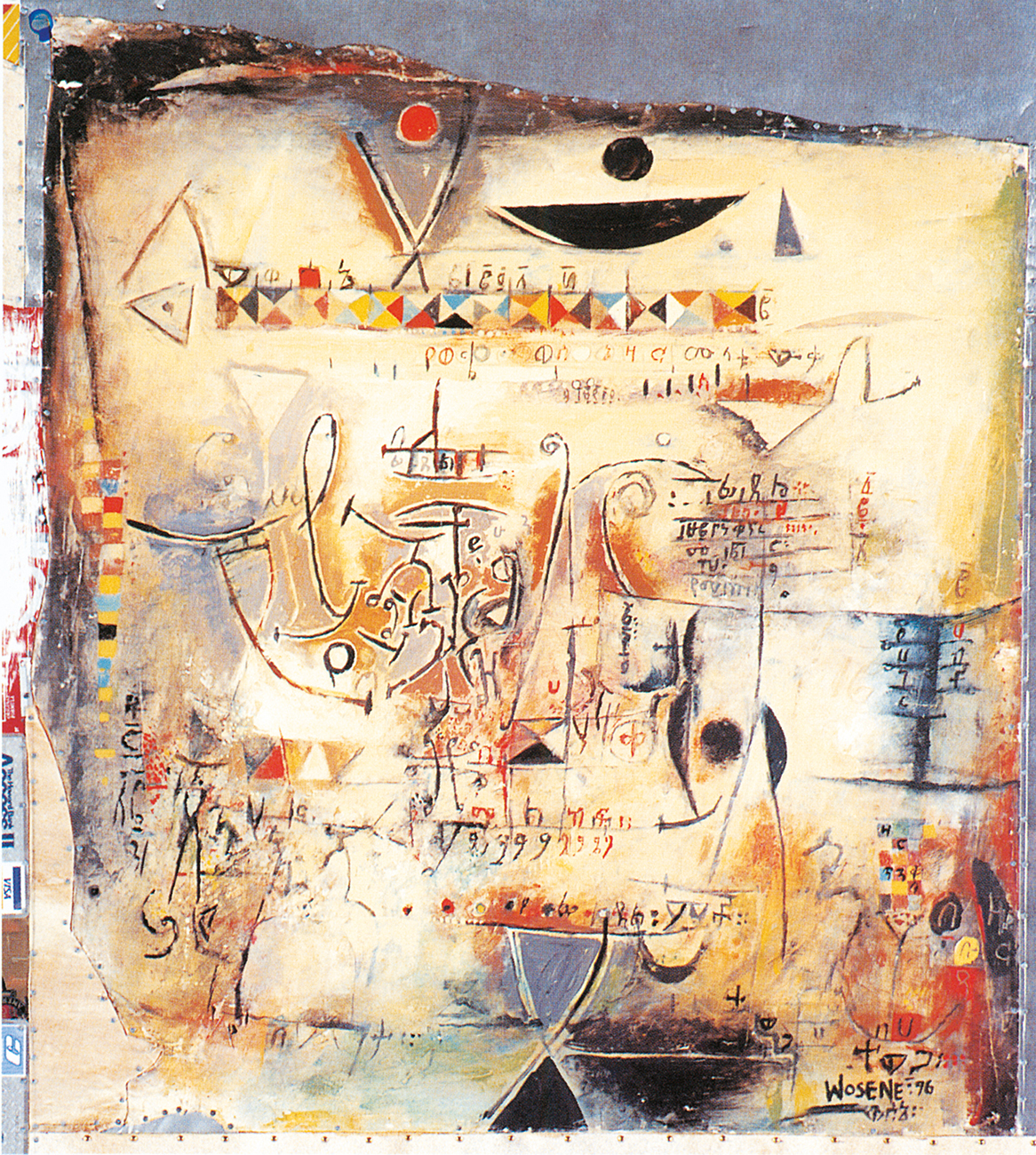

This push and pull of memory and sensibilities can work in different ways. Skunder (Alexander) Boghossian (1937–2003) trained in London and Paris and spent only four years teaching in Ethiopia (1965–69) before migrating to the USA in the early 1970s, but was nonetheless very much an ‘Ethiopian’ artist. His visual vocabulary – while it changed and evolved throughout his career, and at one time encompassed neo-surrealist elements developed in response to his early years in Paris – re-created the memory of the monastic scriptorium in contemporary artistic practice. It is relatively easy to isolate the factors which make this so: a luminosity which recalls the illuminated manuscript tradition of the Ethiopian Church; the pre-eminence of drawing in his work; and his use of a technique which involved the suspension of molecules of paint on a water-soaked surface, creating a strong sense of fission and the fusion of forms within an embryonic mass.

186 Skunder (Alexander) Boghossian, Climatic Effects, 1984–85

187 Skunder (Alexander) Boghossian, Rhonda’s Bird, 1974

188 Ahmad Muhammad Shibrain, Calligraphy, early 1960s

But it is considerably more difficult to explain what Boghossian’s paintings are about. Some of his earlier surrealist works evoked cosmogonic events wrapped in delicate tissues of animals and birds, such as Rhonda’s Bird (1974).[187] Another major strand of his work improvised on the tradition of parchment scrolls lettered in Ge’ez (guèze) – the liturgical script of the Ethiopian Church – or Amharic and decorated with intertextual figures. At first he created painted versions, and later turned these into three-dimensional assemblages using other traditional scriptorium materials such as stretched goatskin. These are in no sense simply referential works; they take off simultaneously forwards and backwards in art history.[186] In Climatic Effects (1984–85) a sun effaced by droplets of precipitating pigment is suspended above a line of scroll-shaped painted images which at first look like colourful neckties hung up to dry.

Boghossian left Ethiopia before the 1974 revolution that overthrew the monarchy, but the repressive military junta known as the Derge soon made returning home an unlikely possibility. Remaining in Ethiopia became an equally uninviting prospect for younger artists, who were pressured by the government to produce works of formulaic socialist realism. The extraordinary outcome was the migration of an important stream of Ethiopian painters to Howard University in Washington, D.C., where Boghossian began teaching in 1972. A diaspora of Ethiopian painters, devoted to him as a colleague or teacher and attracted to the advantages of studying and working in the USA, formed around him.

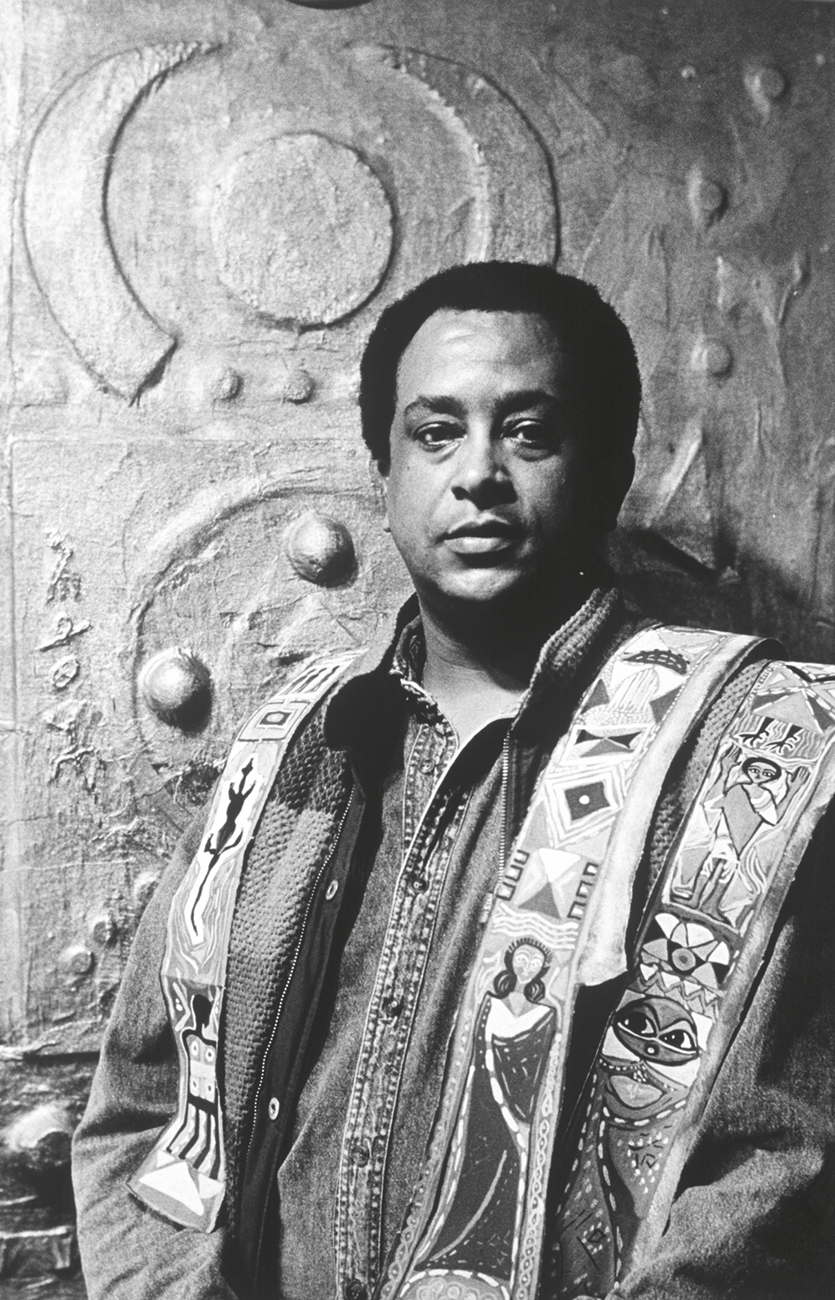

Another example is Wosene Kosrof (b. 1950), who like most migratory Ethiopian artists first studied at the School of Fine Arts in Addis Ababa.[189] He went on to teach there, before travelling to Howard on a fellowship in 1978. After eight years of teaching at Goddard College in Vermont, he moved to California, where he says he was forced to confront sky and water and their effects on light. Even more than Boghossian, Wosene has explored both the graphic and talismanic aspects of writing and the illusion of multiple overlapping surfaces in his painting. His models include the Sudanese artists Ibrahim El-Salahi and Ahmad Muhammad Shibrain, whose explorations of Arabic script in the early 1960s parallel and in some cases predate the investigations by Ethiopian artists into Amharic manuscript traditions.[188] El-Salahi and Shibrain were both students of Osman Waqialla (1925–2007), whose training abroad included the School of Arabic Calligraphy in Cairo and who, by the late 1950s, had established calligraphy as an important artistic genre in what came to be called the Khartoum School.[190]

Girmay Hiwet (b. 1948), whose early education parallels Wosene’s, chose to migrate to Switzerland instead of the USA, though he spent 1983 in Washington, D.C., where his contact with African-American artists was as important as his membership in Ethiopian circles.[191] His 1983 portrait of his Swiss-Ethiopian son Ezana both alludes to the child’s dual heritage and illustrates the strategy of double meanings known metaphorically as ‘wax and gold’ when writing Amharic poetry:[192]

It shows my son: this is the obvious – the wax. There is a saying in Ethiopia which goes: when you have a child, this is the only real way of seeing yourself eye to eye. In this sense the painting really represents me. This is the hidden content: the gold.

The incorporation of both Swiss and Ethiopian symbols in the portrait is a reminder that there are two sides to the question of personal agency raised by cultural nomadism: not only is the migratory artist uprooted from a familiar environment and set down in a different artistic scenario far from home, but he or she both affects and is affected by the practising artists who are already there. Through his presence at Howard University, a major centre of African-American intellectual life, Boghossian influenced not only fellow Ethiopian exiles, but a whole generation of African-American artists, including the AfriCOBRA group, who from 1969 consciously sought to create what they termed a ‘transAfrican’ movement or style. Conversely, transplanted Ethiopian artists such as Wosene were encouraged by their African-American students and colleagues to explore their African artistic sources. This means that work such as Boghossian’s has come to be identified not only as ‘Ethiopian’ art in a sense that other Ethiopians and art historians would understand, but also as ‘black’ and ‘African’ in the culturally mediated sense that is understood by both critics and public in the African diaspora, and in relation to important exhibition spaces such as the Studio Museum in Harlem. Even beyond this, once his work entered the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris, he reached another level of cultural abstraction for a much wider audience, as a ‘modern’ artist. Each of these identities coexists in a sometimes uneasy relationship with the others. For example, to be ‘Ethiopian’ was a positive attribute in the 1970s, but such labels are now criticized by many younger artists as part of a Western discourse of modernity that continually revisits ethnicity as a form of primitivism.

189 Wosene Kosrof, Almaz, 1982

190 Wosene Kosrof, Dancing Spirits, 1996. Wosene has said, ‘In this work I disassemble, exaggerate and distort the Amharic calligraphy…I let the fiedel free-float and dance in space.’

191 Portrait of Girmay Hiwet, 1989

192 Girmay Hiwet, To See Your Own Eyes With Your Own Eyes, 1983

Elisabeth Atnafu (b. 1956), another Ethiopian artist to have come through the Howard University system, partakes of the same culturally mediated identities.[193] As a woman artist in a primarily male circle, living in New York instead of Addis Ababa, gender becomes for her one more publicly marked category. In 1976, she won the United Nations’ International Women’s Artist Award. Although initially a painter, she followed the trend towards installation in work such as A Shrine for Angelica’s Dreams (1994), which transforms the white dress worn by highland Ethiopian women into an evocative, lace-edged 1920s Western-style dress and uses it as a framing device hung with memorabilia evoking transcultural memories. Her paintings of the 1980s identify her more closely with the Howard-Ethiopian circle, in their use of paper, a luminous palette of colours and fine, sgraffito-like line.

193 Elisabeth Atnafu, The Year of Love, 1984

Diasporic experience has not been the only formative influence for these artists. Several were trained first by Gebre Kristos Desta at the School of Fine Arts in Addis Ababa before migrating abroad. Born five years earlier, Desta’s early career paralleled that of Boghossian, training in Germany and returning to Ethiopia in the early 1960s at a time of cultural florescence across much of the continent. He continued to teach at the School long after Boghossian had left, making his influence felt on many artists, including Achamyeleh Debela and Alemayehou Gabremedhin. Although the son of a manuscript illuminator, he disclaimed the religious aspect of art in his own work, which was aggressively non-traditional and ranged from painterly abstraction to an emphasis on drawing and figural themes focused on contemporary poverty and oppression. Nonetheless, one of his seminal works, Golgotha (1963), uses the crucifixion of Christ as the metaphor for this oppression.[194]

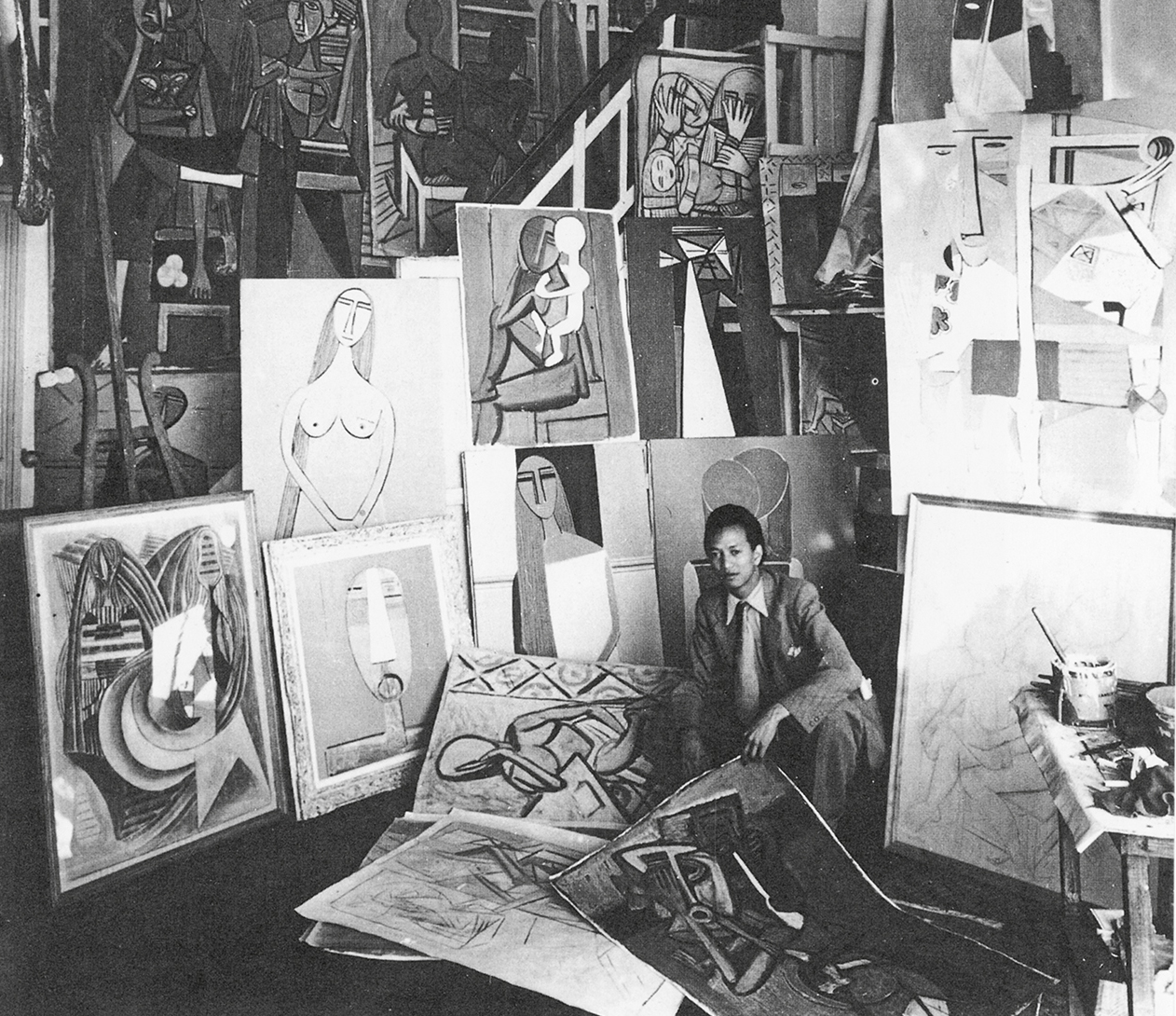

Achamyeleh Debela (b. 1947), Desta’s former student, migrated to the USA in 1972, where he rejoined Boghossian’s circle and later studied for a doctorate in computer art.[195] He has embraced technology in a way that reflects both the iconoclasm of his early teacher and the traditionalizing modernism of the Washington group. Alemayehou Gabremedhin, who also studied with Desta and Boghossian, works in Maryland and exemplifies the culturally balanced ‘transAfricanism’ which AfriCOBRA artist Jeff Donaldson has described as originating with the Cuban painter Wifredo Lam (1902–1982). The genealogical connection in Alemayehou’s case can be traced through Boghossian, who with Lam was part of a group of French, African and African diaspora artists, poets and intellectuals who interacted together in Paris during the late colonial period, experimenting with surrealism and the transcultural literary project of Négritude.[196]

194 Gebre Kristos Desta, Golgotha, 1963

195 Achamyeleh Debela, A Song for Africa, 1992–93

196 Wifredo Lam surrounded by his paintings in his studio at 8, rue Armand Moisant, Paris, 1940

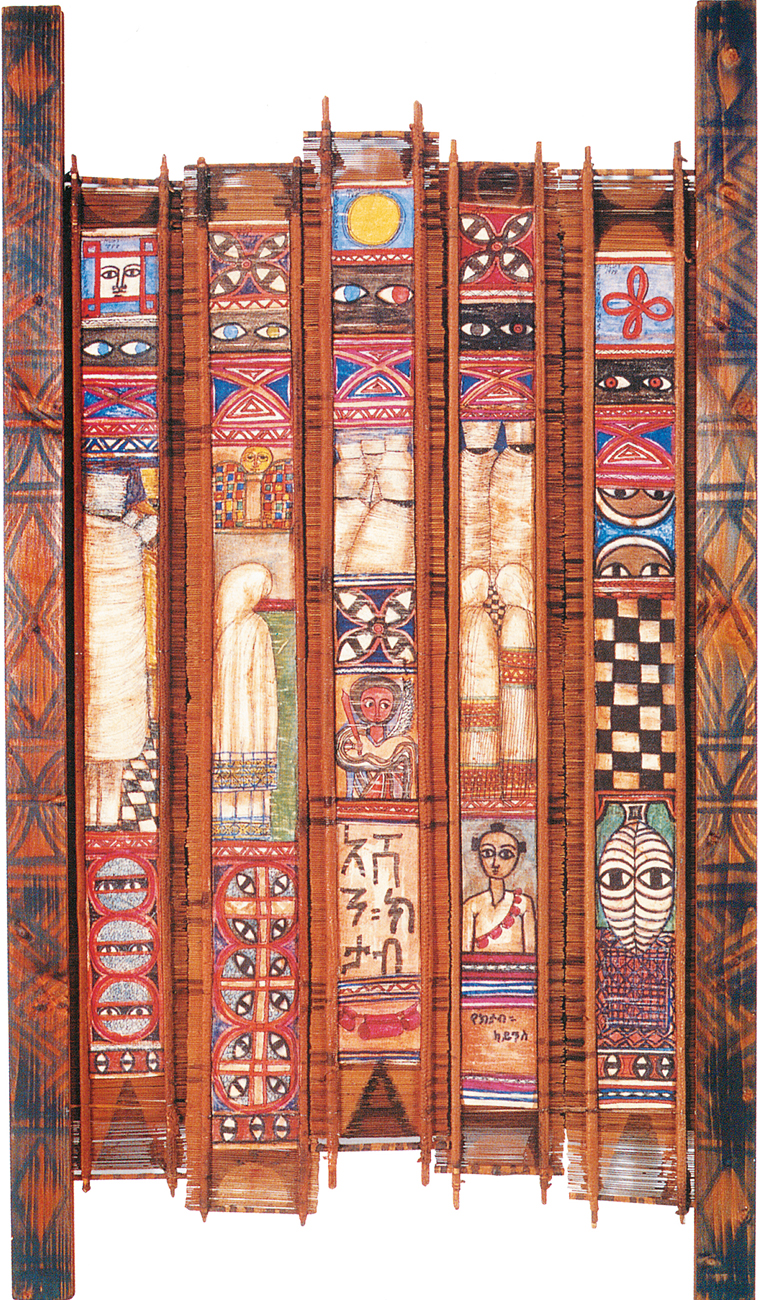

The careers of these Ethiopian artists exemplify one kind of diasporic movement of African art out of its place of origin and primary cultural identity. Theirs are richly textured narratives of displacement, the classic material out of which art histories are usually constructed. But what of those who didn’t leave? Zerihun Yetmgeta (b. 1941)attended the School of Fine Arts in Addis Ababa between 1963 and 1968, first taught by the German woodcut artist Karl Heinz Hansen (known as Hansen-Bahia) and then by Boghossian. This resulted eventually in mixed-media works made from long narrow panels of painted skin, framed on bamboo strips and depicting the history of Christian religion, the art of magic, the evolution of animal life, science and even women’s fashions. A fundamental theme in his work is enigma, suggested by the white-clad priest figures whose faces are hidden in Research from the Art of Magic (1988). To these are added the strange juxtapositions found in Fishing the Evil Eye (1989), a Solomonic icon which masks its hidden meaning: it is actually Jesus Christ, situated before a large television screen (an icon of competing but lesser power), guarded on both sides by birds while the sun with its aureole of crosses hovers above as another hidden symbol of Christ.[197] Yetmgeta stayed on at the School as an instructor in woodcutting after Hansen-Bahia had left.[198] He considers this fact crucial to his development:

It is a good thing I did not go abroad to study art…my studies…would have filled me with rules and beliefs which would have prevented me from being fully Ethiopian and unabashedly African, which is to say, I would not have been able to be fully myself as an artist.

Yet without these biographical details, it would be difficult for the spectator to single out Yetmgeta’s work among a group of Ethiopian artists of his generation as the only one not living abroad. This suggests right away that the model of how art actually ‘travels’ globally is too simplistic if it is assumed to involve only artists who themselves circulate. Clearly Yetmgeta saw illustrations of the work of Boghossian or Wosene or Hiwet from time to time, and they saw illustrations of his. Influence, as is clear with the case of Picasso and so many African artists, does not necessarily require rubbing shoulders.

Yetmgeta and many of the Ethiopian artists who formed the Washington diaspora employ talismanic signs and certain materials and techniques of the monastic scriptorium as points of connection to a cultural matrix that they claim, much as the Nsukka group of artists used uli or nsibidi (see Chapter 7). But just as there are still ‘real’ uli artists – the women who decorate compound walls and their own bodies – so there are also ‘real’ makers of talismanic art in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. The artist known as Gedewon lived in Addis Ababa and made what he calls ‘talismans of research and study’ as well as others which have a direct protective function – prayers, lists of evils and names of God written in ink on pieces of paper, which are divided into sections, each containing a text in Ge’ez (guèze), embellished by human and animal figures. The boundary between the sacred art of a practitioner and an art that references the same forms is sometimes clear and at other times blurred. Gedewon often seemed part-artist, part-priest.

197 Zerihun Yetmgeta, Research from the Art of Magic, 1988

198 Zerihun Yetmgeta, Fishing the Evil Eye, 1989

The Ethiopian case is unusually complex because it involves so many artists in close contact with one another, but there is another form of artistic migration which is much more solitary, itinerant and hand-to-mouth, and which follows the model of the lone entrepreneur. Some migratory art is carried by African artists who travel, rather than it making its way into New York or London or Johannesburg through the curatorial route of international exhibitions.[199] Tunde Odunlade, once apprenticed to Osogbo artist Yinka Adeyemi in Nigeria, combines the roles of artist and entrepreneur by travelling frequently from city to city in the USA attempting to exhibit and sell not only his own work, but also that of several others from Ife and Osogbo. Such art exists underneath the radar of the curatorial establishment, but has a wide audience because it is modestly priced and readily available.

199 Tunde Odunlade in Atlanta with his work Happy Faces, 1995

One of the original group of Osogbo artists, Jimoh Buraimoh, travelled to Atlanta in the USA to exhibit his bead mosaics in the 1996 Olympic Games Cultural Olympiad.[200,201] Following that, he worked part-time teaching children in Atlanta schools and completed a mosaic commission for the city’s Bureau of Cultural Affairs. He eventually bought a house in the northern suburbs of Atlanta and turned it into a gallery for his work. These kinds of connections are more difficult for workshop-trained artists to sustain than they are for artists who have the paper qualifications to enter the university teaching circuit. Buraimoh was an electrician for the Duro Ladipo theatre company in Osogbo when he attended Georgina Beier’s second workshop in 1964. As the only artist emerging from that milieu to work in the bead medium, his production was distinctive, yet shared the boldness and rough energy of the early linocuts and paintings. A decade later he completed a certificate course in design at Ahmadu Bello University, but it is his entrepreneurial skills that have enabled him to travel abroad – before embarking on this nomadic stage of his career, he opened a restaurant and music club in Osogbo, which supports his family in his absence. He is also an official in the international cultural tourism event, the Osogbo Festival.

200 Jimoh Buraimoh, bead mosaic in progress in the artist’s studio, Atlanta, 1997. From his smaller-scale work at Osogbo in the 1960s, Buraimoh moved towards working on larger, more geometric compositions.

201 Jimoh Buraimoh, Untitled, 1964

Another category of migrants are women who have found it difficult to be taken seriously as artists in their own cultures, among them Sokari Douglas Camp (b. 1958), a Nigerian sculptor who lives and works in the UK.[202] She was interviewed by Wendy Belcher in 1988, prior to the opening of her exhibition at the National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C.:

WB: What are the major influences on your work?

SDC: The major influences are the Kalabari festival and the fact that in the West women are allowed to make sculptures. In my own situation in Nigeria, I would not be given the opportunity to make art, because objects in my part of Nigeria are religious. If I were making objects in Nigeria, I would be a priestess. I wouldn’t be talking about art. I’d be talking about curing people or talking to spirits….

WB: Do you see yourself primarily as a Western artist or as an African artist?

SDC: I see myself as an artist. Being an African artist or being a Western artist has got nothing to do with it. I think that being an artist overrides all that.

It would be hard to imagine another answer to this question from an artist who was trained at the California College of Arts and Crafts and then in London, and has never practised art in her own country. At the same time, the thematic repertory for her work comes from Kalabari culture and is very strongly situated within it. The process of fabrication itself is tied in her memory to such things as helping her mother make thatching. She says, ‘I find myself preparing things in my work as if I am making the things I’ve seen women make. I am forever binding my stuff, cutting it into little bits, and fixing it into something else. I think my art has something to do with cooking or cleaning the house.’ In saying this, she revives the domestic artisanship of Kalabari women as something of ongoing relevance, yet reserves the right to be ‘just an artist’, neither African nor Western – she uncouples her past yet keeps it close to hand, like a particularly useful workshop tool.

202 Sokari Douglas Camp, Clapping Girl (Small Iriabo), 1986. Of her experimentation with moving metal sculptures, Camp has said, ‘movement I find very amusing, and I think you need humour….The serious side of it is that I would like to shock.’

These identity claims sometimes have more to do with artists’ everyday conditions of production than with their cultural memories, but it can also be the reverse. Magdalene Odundo of Kenya and Mohammed Ahmed Abdalla of Sudan are cases in point. Both are superb contemporary potters, African ceramic artists who live and work in the UK. Despite this, Abdalla has consciously worked within a formal tradition associated with the Nile Valley, adapting it to high-temperature firing and the wheel-thrown technique. Odundo, on the other hand, has chosen to do the reverse: her minimalist pottery style is completely her own and bears no formal resemblance to traditional Kenyan pots, but her technique combines the hand-building typical of African clay vessels with a variety of firing methods.[203] Furthermore, to learn traditional techniques (having been trained initially in Western ones), she not only returned to Africa and observed Kenyan and Nigerian women potters at work, but also studied the potters of San Ildefonso in the American Southwest. Her relation to any particular tradition is therefore much more ambiguous than either Abdalla’s or Sokari Douglas Camp’s, although she – unlike they – has chosen to employ an ancient technology.

203 Magdalene Odundo, Untitled #12 (front) and #8 (back), 1995

Western collectors, cultural institutions and audiences are decidedly more at ease with artists who lay claim to their African identity than with those who do not. For one thing, this identity is made to seem natural in the discourse of many African diaspora artists and critics and in the popular interpretation of multiculturalism. For another, it appears to provide some kind of necessary formula for decoding work that is assumed by critics and publics to be otherwise resistant to interpretation. In purely pragmatic terms, it is therefore easier for an African artist abroad to make use of this circumstance than to fight it. Nonetheless, several do, using some of the same arguments made by artists of Native American ancestry such as James Luna in, for example, ‘The Decade Show’ (1990). While there are many important differences between them and African artists working in the international arena, Native American artists have also had to position themselves for or against an art-world discourse that assumes any approach to their work must centre on their own relation to a primordial ‘tradition’. In 1992, Billy Soza War Soldier spoke for many of these artists when he said, ‘I really consider myself an American painter, although I am an Indian. No one calls Picasso and Dalí Spanish painters.’

204 Olu Oguibe, The Emperor, or the Beast in Landscape, 1990. The title makes the connection between the long-horned bull and aggressive political power – but the real power of this image lies in its extreme economy, with just the barest suggestion of a red sun and burnt-out landscape.

Olu Oguibe (b. 1964), a painter and writer living and working in the USA, has gone even further in distancing himself from his previous identification with ulism, Nsukka and Nigeria:[204]

An artist as transitory as myself would not fit into a style. I have referenced Uli, Nsibidi, Adinkra, Adire, Mbari, Dogon sculpture, Ndebele murals, San rock art, Maya and Inca textile art, European abstract expressionism, postmodernism, social realism and conceptualism, in addition to my own forms and ideas.

Part of this, as Simon Ottenberg suggests, is a conscious strategy to work through the implications of a collapse-of-history postmodernism. Another part is likely to be the constant exploration of new sources that characterize the trajectory of any inventive artist’s career. But both the strategy and the pursuit, when focused upon concrete cultural references such as nsibidi signs or San rock art (as opposed to less specific cross-cultural phenomena such as social realism or conceptualism) suggest a further motive, which could be summarized as the African artist-intellectual’s search for a ‘usable past’. That usable past becomes an encyclopaedic referencing of history in the work of Ouattara Watts (b. 1957), an Ivoirian-born painter who lives in New York.[205] In Samo the Initiated (1988), said to memorialize his friend, the diaspora artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, a partly mummified Egyptian lies inside a casket over which are suspended two divination boards with different messages encrypted, while a small lizard hangs in the upper left corner. Watts’s more recent work continues to evoke myth and retroactive surrealist elements such as the floating eye against a blank background.

205 Ouattara Watts, Samo the Initiated, 1988

206 Yinka Shonibare, Five Undergarments and Much More, 1995

London, once the centre of the British Empire, is closer to Africa than New York is, both geographically and psychologically. Yinka Shonibare, a Yoruba artist born in London in 1962, works on his installation pieces there, using the printed cotton (kitenge) derived originally from Dutch Java wax batik prints and factory-made in Manchester, England, for the African market, as his medium. The transnational character of the designs (Indonesian, transformed by British manufacturers to be generically ‘African’) and their tracing of colonial trade routes (Indonesia–Holland–England–Africa) gives them a vocality of their own, which interacts with the installations’ other messages.

Shonibare has had both critical and financial success by creating endless variations of his wax-print models. Aside from the cloth itself, his ‘signature’ is that the models are always headless. This is intended ironically, but it also serves to erase any hint of Africanness in the figures. In that sense they are ‘about’ whiteness and imperial power. Five Undergarments and Much More was created for the ‘Imagined Communities’ exhibition (London, 1995), itself a comment on Benedict Anderson’s 1983 study of the same title.[206] Anderson argued that representations of all kinds (artworks, flags, stamps, uniforms, etc.) are constitutive of, not merely reflections of, communities and, more broadly, nationalisms. In the catalogue essay, Kobena Mercer extends this point to the shaping of ‘counter-nationalisms’ – imaginary cultural maps with no corresponding territories, just emotional ties with a once-shared past or a fragmented present. In this sense, both Nigerian and Ethiopian artists abroad are part of imagined communities.