How John Mackey’s Vision Saved Whole Foods from Drowning

On Sunday, 24 May 1981, Austin, Texas, was hit by a severe flood: the first, and at that time only, Whole Foods store was eight feet underwater.

Overnight, the company went from being profitable, loved by its customers and employees alike, to $400,000 in the red.

There was no insurance, no off-site inventory, no backup of any kind.

Would the business survive?

At the time, the obvious answer was “No.”

The day after the flood was the Memorial Day holiday. Management and team members were despondent. As Whole Foods’ founder, John Mackey, relates the story in his book Conscious Capitalism, it was “the end of a dream” and “the end of the best job we ever had.”1

As they began to see what they could salvage, an amazing thing happened: “Dozens of our customers and neighbors started showing up at the store … bringing buckets and mops and whatever else they thought might be useful. They said to us, in effect, ‘Come on, guys; let’s get to work. Let’s clean it up and get this place back on its feet.’”2

Such customer reactions lifted the spirits of the entire Whole Foods team, founders and employees alike. It’s hard to imagine many other businesses so inspiring their customers.

CLUE #4

Driven by the Founder’s Vision and Passion

Every new company is driven by its founder’s vision for the company and passion for achieving its goals.

When, and only when, the founder communicates his vision to all company members, inspires them to make it their own, and creates a system that enables frontline employees to communicate that same vision to customers and other stakeholders through action, which in turn creates a high degree of customer involvement and loyalty, will that vision drive the company’s culture and provide a solid foundation for a great company that has a chance of surviving the founder’s retirement or death.

That’s just the beginning of this Whole Foods story. In addition to the customers who rallied around:

• Employees worked to clean up the store without pay. Of course, they would draw pay when Whole Foods was back on its feet—but would that ever happen? At the time, no one could know for sure.

• Suppliers extended credit “because they cared about our business and trusted us to reopen and repay them.”3

• Whole Foods’ shareholders came up with additional investments—and the company’s banks even loaned the company more money!

To understand the magnitude of Mackey’s achievement, imagine for a moment that your business was eight feet and $400,000 underwater.

Would your employees rally around? Would your neighbors and customers show up to help clean up the mess?

Even if they did, what’s likely to happen if you go down to your bank, red-inked balance sheet in hand, and ask your “friendly” banker to lend you more money? Which response would you expect:

1. “Sure, here’s another four hundred thousand dollars on top of what you already owe us, plus a line of credit to tide you over.”

2. Uncontrollable laughter—and the moment you’ve walked out the door, the lawyers are called in to initiate bankruptcy proceedings so the bank can grab whatever leftovers it can ahead of your other creditors.

Then you call your suppliers and ask them to replace, on credit, the ruined stock that you still haven’t paid for. The most likely result: a race between your bankers and your suppliers to see who’ll be first in line at the bankruptcy court.

Whole Foods’ suppliers and banks both chose the first option.

Why?

The “Counterculture Capitalist”

John Mackey fully embraced the counterculture movement of the sixties and seventies, studying ecology and Eastern philosophy, embracing yoga and meditation, becoming a vegetarian, topped off with a beard and long hair. He became involved in the food co-op movement, agreeing with their motto: “food for people, not for profit.”4 But he soon discovered that co-ops were dominated by internal politics, the “most politically active members” focusing more on “which companies to boycott” than on serving their customers. He concluded he could do better and “became an entrepreneur to prove it.”5

Immediately he was transformed in the eyes of his former associates into another “evil, exploiting businessmen” and came under fire for charging too-high prices and paying too-low wages.

Yet Mackey persevered, discovering that business is the opposite of the counterculture myth of venality and greed: that a business can only succeed with the voluntary cooperation of everyone it deals with—customers, employees, investors, and suppliers.6

John Mackey’s Vision: A Business Based on Love and Caring

Just one thing changed in Mackey’s transition from co-ops to a for-profit corporation: his preferred method of executing his vision. He saw for-profit as a better way to create an organization that truly cares for everyone it deals with—customers, employees, suppliers, and investors—and fulfill his (and the co-ops’) counterculture mission of persuading people to adopt a healthier lifestyle by eating “whole foods.”

Underlying Mackey’s vision is the insight that all businesses—indeed, all organizations—depend upon relationships.

The nature of those relationships, both within the company and without, determines the nature and culture of the company, the employee and the customer experience, and ultimately the health of the business, profit being just one measure of that health.

Whole Foods’ bankers and other suppliers, like its employees and customers, cared about the business because Mackey and his associates cared about them. They were partners in Whole Foods—not because of any equity or legal claim, but due to the nature of their relationship with the people at Whole Foods.

So when Whole Foods was eight feet underwater, its bankers and suppliers were ready to listen. What’s more, they wanted to be able to help—in the same way that you would wish to help a friend in trouble.

That doesn’t mean they opened their checkbooks the moment Mackey walked in the door. But they did want to hear what Mackey had to say and were willing, if not eager, to be persuaded. As Mackey could demonstrate that—despite the red ink—the flood was a onetime event unrelated to the underlying health of the company, they pitched in.

From this experience Mackey concluded, “What more proof did we need that stakeholders matter, that they embody the heart, soul, and lifeblood of an enterprise?”7

I doubt any other company founder has had his or her vision fully verified in such a dramatic manner.

The core of Mackey’s vision for Whole Foods is his belief that stakeholders matter.

Stakeholders Matter

Mackey’s stakeholder concept includes everybody who has a stake in your business, no matter how small or indirect: customers, employees, investors, and suppliers (including banks and other financiers), governments, neighbors, and the community at large—extending to the environment. While that stake may be emotional rather than financial, Mackey believes it’s just as real and just as significant to the health of the business.

Operationally, that means that all relationships, both within the company and without, must be based on the bottom-up partnership model, the opposite of the traditional top-down command-and-obey culture.

Investors or Creditors: Who Has the Greater “Stake”?

Legally, only investors have an ownership stake in a business. But—also, legally—creditors’ claims against a company’s assets rank ahead of investors’. Indeed, in a bankruptcy court, investors come dead last.

Creditors include bondholders, banks, suppliers, employees, and governments: everyone a business deals with daily except investors and customers.

All creditors’ financial well-being is tied, in part or—in the case of most employees, in whole—to the company’s financial health. So they clearly have a stake in the business’s future.

True, investors stand to lose more than creditors; but the creditors’ return on their investment is fixed, while the investors’ return is potentially unlimited.

We can argue about who has most at stake—but to do so is to accept the premise that they all have something at stake.

What About Customers?

Do customers have a financial stake in a business? Indirectly, yes. After all, they shop there because it’s cheaper and/or a better experience in some other way.

More important, every business has a crucial financial stake in its customers. No customers, no business.

“Love your customers” may sound like a counterculture mantra from the sixties—but given what you have at stake, why wouldn’t you love your customers?

And Your Neighbors?

Some of your new customers didn’t come to visit you: they came to shop at the store next door. You were just an afterthought.

So the healthier your neighbors are, the healthier you are, and vice versa.

For example, where’s the best place to open a secondhand bookshop? Somewhere you know you’ll find lots of book buyers—and where better than right next door to a Barnes & Noble or similar popular bookstore?

The last thing you want to happen is to see that store close down.

“Employee” or “Partner”?

It’s become fashionable to refer to employees as “partners” or “associates.” But is this change in terminology meaningful?

“Partnership” implies equality. This is certainly true in an incorporated partnership, where a majority or even unanimous vote is required for any significant change.

An employer-employee relationship is clearly not equal in this sense.

But it can be equal relationally, when owners and managers refuse to exercise their “employer” prerogatives and relate to employees as partners. This must include giving employees an effective veto power over management decisions.

A powerful example comes from Starbucks’ Philippines affiliate. In 2011, the management decided to ban smoking in the outdoor seating areas of all Starbucks stores. The result was a dramatic loss of business: stores that had been packed were suddenly half—or sometimes three-quarters—empty.

In one meeting with store managers, the central management proposed laying off probationary employees to cut costs. The store managers said, “You can’t do that; you’ll be breaking your agreements.”

The management agreed and realized it also had to listen to its customers and reinstitute the smoking areas to get them to come back.

What makes this example doubly powerful is that Filipino culture—like that of many other Asian and non-Western countries—encourages subservience, discouraging the development of self-confidence and self-esteem. Speaking up (especially to superiors) is actively frowned upon.

The ultimate test of whether a business is following the partnership model is:

• Do employees feel they are important?

• Are they encouraged to express their opinions and suggestions?

• Are they heard when they do?

• Do they have the sense they can make a positive, even transformative contribution to the business, beyond just punching the clock every day?

For the Partnership Model to Work, the “Deal” Must Be Spelled Out

Richard Branson could be unpredictably generous—or stingy. In 1970, he gave Nik Powell, his childhood friend and partner in the mail-order record business that was the foundation of Branson’s fortune, 40 percent of the company that became Virgin Music. Simon Draper, another early hire, received 20 percent of Virgin Music, also without payment. When Branson personally received a settlement of £500,000 from his lawsuit against British Airways in 1995, he distributed the entire amount to Virgin Atlantic staff.

So when Branson sold Virgin Music to Thorn EMI in 1992, for £560 million ($1 billion), most employees “had just taken it for granted that [they] would all share in the benefits that they had helped Richard, Ken, and Simon to build.” This expectation was one factor in Virgin employees’ willingness to work long hours for lower wages than they could have received elsewhere.

For example, Steven Lewis, who had walked in the door of Virgin Records when there were only six employees, had received several far richer offers from other record companies—and turned them all down. He and Simon Draper were the two people responsible for building Virgin Music into a billion-dollar company.

Lewis was in charge of Virgin’s music-publishing division, which accounted for 20 percent of the group’s profits—but only 10 percent of its revenues. Lewis had also been given equity, not in Virgin Music but the company that managed Virgin artists—which had been shut down several years before. So while Draper walked home with £112 million ($200 million) for his 20 percent share of the purchase price, Lewis received nothing.

As did Virgin’s employees. Despite their expectations, this time around Branson didn’t share the wealth.

At the time, Virgin was under considerable financial pressure. The 1991 Gulf War resulted in a dramatic decline in air travel and a spike in oil prices. To save Virgin Atlantic, Branson had to reduce debt—otherwise he would never have sold the group’s “jewel in the crown.”

But Branson’s stated business philosophy is to put employees (whom he calls “associates”) first, customers second, and shareholders last. When employees and customers are looked after, he says, the return to shareholders will take care of itself.

The lesson is clear: for the partnership model to work smoothly, for an employee to be a real partner in the business, the arrangement must be unambiguously defined—and top management must be emotionally committed to making the deal work as originally agreed, come hell or high water.

When treated as partners, employees are excited to come to work, and that excitement transforms the customer experience.

Working with suppliers on the same basis has similar results. As Mackey notes, most of the suppliers who stood by Whole Foods when it was underwater are still suppliers today, thirty-six years later.8 Loyalty is a two-way street.

A Culture of Fear

Most businesses, says Mackey—indeed, most organizations—are based on the opposite model of “carrot and the stick.” That is, incentives—and fear.

He claims a business such as Whole Foods that “loves its customers” (and other stakeholders) has a competitive advantage over that traditional business model.

Is he right?

Fear is an inefficient method of motivation. It results in masters who tell their servants what to do—and a servant’s job is not to “reason why.” Creativity is thus restricted to the higher levels of the organization. The lowly employee whose hands-on experience could result in an improvement saving or making thousands or even millions of dollars is hardly encouraged to open his mouth.

A fear-driven business inevitably alienates its employees, who turn to unions when they feel there’s no other way to protect their interests. As the 2009 Chapter 11 bankruptcy of General Motors all too clearly demonstrates, such a relationship can bring a company to its knees.

The overall differences between businesses driven by love or fear are shown in this table of extremes: there will inevitably be days when Whole Foods’ partners are bored on the job—or someone in a fear-driven company will challenge the boss and win.

The difference becomes startlingly obvious at the customer interface. The business based on love—or, as Howard Schultz phrases it, on creating an emotional connection with customers—results in a superior customer experience.

That, in turn, results in increased customer loyalty, which increases repeat business and reduces customer turnover, ultimately producing higher profits and a superior return on investment compared to businesses structured on the top-down, carrot-and-stick approach.

In other words—

Love Works

If your first reaction was “What’s love got to do with business and investing?,” you’re not alone. That was my attitude when I first learned about John Mackey’s unique approach to business.

Cynical me’s immediate thought: “Good marketing.” I certainly didn’t buy Mackey’s argument that his “stakeholder” approach should replace the traditional model where the primary, if not sole, purpose of a business is to make money for its owners.

When Mackey debated this issue with Nobel Prize–winning economist Milton Friedman, I was firmly in the Friedman camp.9

But the experience of a good friend of mine dramatically confirmed the accuracy of Mackey’s approach in a way that studies of large enterprises—including Whole Foods itself—never can.

Ramona is one of those lucky people who discover why they were born early in life. She lives to teach.

She could have worked anywhere but chose a small kindergarten where she was free to experiment, exercise her creativity, innovate, and create and refine her own teaching methods.

Love what you do—but your company should love you back.

—Howard Schultz

Ramona is one of those people who care “too much.” She cared about the students, cared about her assistants, and cared about the parents. She had never heard of John Mackey, yet her approach to management could have come right out of Mackey’s Conscious Capitalism.

Because she cared, she loved, demonstrated in this exchange between one of her students and a substitute teacher:

Student: “Do you love us?”

Teacher: “Of course!”

Student: “You’re lying. We know teacher Ramona loves us. We feel it. She doesn’t have to tell us. With you, we don’t feel it.”

Ramona enlisted the support and creativity of the assistants by always asking for their input, eager for any improvement regardless of whom or where it came from. Her management style was not to give orders but to make suggestions like “How about doing it this way? What do you think?”

The Results

The kids eagerly looked forward to going to school every day; the thought of playing hooky never occurred to them.

Parents were delighted with their children’s progress. When Ramona’s students went to “the big school,” they read at a grade two (and sometimes three or four) level, had a basic grounding in math and science, and were the kind of students some teachers love to hate. The ones with inquiring minds who are never afraid to point out teachers’ mistakes and ask questions adults would prefer not to answer. Self-confident, independent thinkers (and we’re talking about six-year-olds and younger in a world of adults, remember).

The Bottom Line

The school’s reputation skyrocketed; within eighteen months student numbers zoomed from thirty-five to sixty-one, with more on a waiting list, all by word of mouth.

And the school’s profits tripled.

If you employed people who’d tripled your profits, wouldn’t you reward them? Wouldn’t you appreciate their efforts, acknowledge their contributions, support them in every way you could … in sum, do everything within your power to make sure this person stayed with you indefinitely?

Doesn’t that sound like the logical thing to do?

But Ramona paid a high price for her freedom to teach her way.

The school’s owner was a penny-pinching control freak: her primary management tool was fear. She got away with paying undermarket wages by capitalizing on her employees’ insecurities, especially their fear of losing their jobs. Or, in Ramona’s case, by exploiting her passion to teach.

She greeted Ramona’s achievement not with appreciation and higher pay, but by accepting new students without apparent limit.

The success of Ramona’s approach depended, in part, on reaching every student as a unique individual. So each new student meant more preparation, less play, and even less sleep.

With twice the students and no additional help (“too expensive,” according to the owner), Ramona’s health suffered; after much agonizing, she quit.

The change in the school after Ramona left was dramatic—and immediate.

The owner stepped back into the saddle, having to give up other remunerative activities to do so. The rule of love was replaced with rule by fear, and the school ceased being a happy place.

In the first week, a dozen kids, 20 percent of the total, simply stopped showing up—a considerable achievement given most had to overcome their parents’ objections. The rest were waiting for Ramona to come back.

Ten months later the school’s attendance had shrunk to just thirty kids—fewer than the thirty-five students it had when Ramona started working there. The school’s owner paid a high price for her management style.

How to Destroy a Brand Name in One Easy Lesson

Van Morrison used to be one of my favorite artists. I still love his music—but I can’t listen to it anymore without wincing.

Here’s why.

Around 1980—that’s over thirty years ago, but it still sticks in my mind—my wife and I went to the Montreux Jazz Festival. We only had time for one show, so naturally it was Van Morrison’s.

Eyes closed, his music was as good as, if not better than, my CDs by him.

Eyes open was the problem.

Morrison sang behind a standing microphone at center stage. On top of the piano, some six feet behind him, was a drink plus an ashtray holding a lit cigarette. Between verses, Morrison would saunter back to the piano, lean on it—turning his back to the audience—take a drag from his cigarette, have a swig from his glass, and maybe chat quietly with the pianist—and get back to the microphone just in time for his next stanza.

To me, his message to the audience was loud and clear: I don’t give a damn about you.

I left the show feeling that I’d wasted my time and money—and been insulted to boot!

Morrison’s disdainful lack of engagement demonstrates, by counterexample, the power of total involvement with customers.

Why Love Works

Mackey’s love-and-caring approach works because profit is a residual.

Ramona, for example, had no incentive to increase the school’s profits—but she tripled them by attracting new students.

Sales went up.

Increased profits were a side effect of loving your customers.

Profits are the difference between income and expenses. As such they are what’s “left over” from two other activities: increasing sales and reducing costs.

You can’t increase profits by aiming to increase profits. You can only increase profits by targeting sales and costs.

Increased profits may be your ultimate aim, but you can only achieve that target by aiming somewhere else.

For example, if you want to drive from Los Angeles to New York, you first have to get onto the freeway. You then aim for, say, Las Vegas or Phoenix, and so on until you finally reach your target. Miss any one of those intermediate aims and you could end up in Miami or Toronto instead.

Arriving in New York is the result of thousands of intermediate aims; you’ll never arrive by simply aiming for New York.

So it is with any business.

Walmart’s “low, everyday prices” are achieved by, first, reducing its markup across the board and, second, by relentlessly cutting costs to the bone—so further reducing prices. As a consequence, sales’ volume goes up, as, ultimately, do profits.

Whole Foods’ and Walmart’s financial results are both a consequence of a narrow focus on somewhere else. In each case, that “somewhere else” is determined by the vision driving the company.

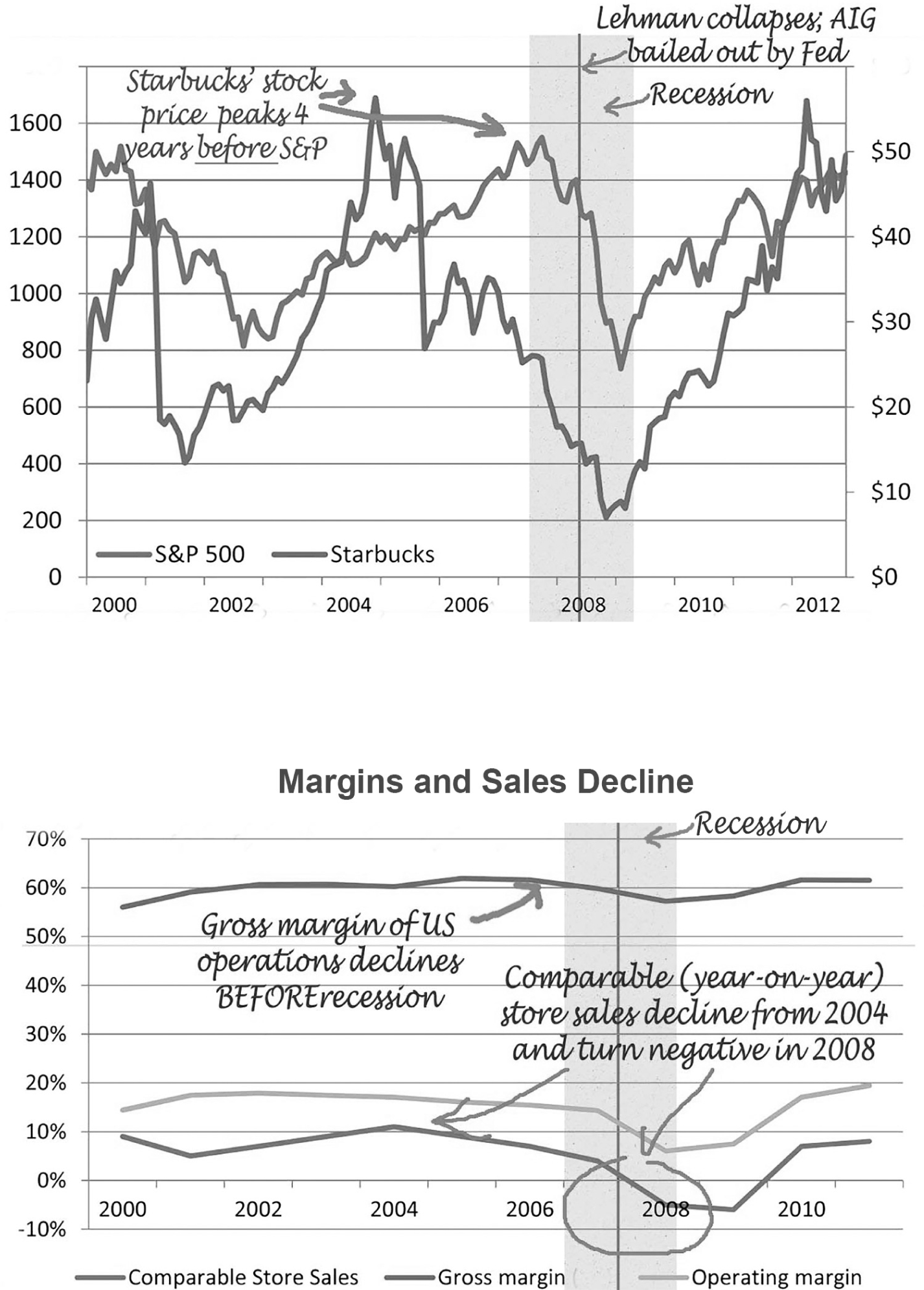

Arguably, though, Starbucks most dramatically demonstrates—

The Power of Vision

In 2000, Starbucks’ founder, Howard Schultz, gave up the position of CEO and stepped back from the company’s operations, becoming chairman and focusing on international expansion. Seven years later—despite the tremendous growth in the number of Starbucks stores, same store sales, revenues, and profits—he’d become convinced that Starbucks in the United States had lost its way and was in danger of losing its position as the “third place”—after home and office—where people gathered, whether to work, surf the Internet, or simply hang out. His concerns included:

Starbucks had ventured into unrelated businesses.10 CDs, books, even cuddly toys were some of the items offered in Starbucks stores. They added to sales and profits—but what did they (not to mention forays into music and movie production) have to do with coffee or the romance of Italian espresso bars? Absolutely nothing.

When Maximizing Shareholder Value Is Not Enough

Like profits, maximizing shareholder value is also a residual. A fact dramatically illustrated by Apple’s transitions from Steve Jobs to John Sculley (1983) and back to Steve Jobs (1993).

One of Sculley’s stated aims as CEO was to maximize shareholder value. Top management received generous stock options—in 1988, Sculley was the highest-paid CEO in the computer business—and to ramp the stock price, $2.218 billion was paid out in dividends and stock buybacks between 1986 and 1996.

Initially, it worked. But the massive “investment” in maximizing shareholder value was money diverted from developing new products and refining current ones. The long-term result: when Sculley became CEO on April 8, 1983, Apple’s stock closed at $4.92; when he left the company on October 15, 1993, Apple was at $7.06. A rise of 43.5 percent over his reign, compared to the S&P 500’s gain of 207.16 percent over the same period.

Only when Steve Jobs returned to the saddle, with his primary focus of creating beautiful products, did Apple’s shareholder value recover—becoming at one point the world’s largest company by market value as a side effect.

But they did increase same store sales, one way the management was—

Giving in to pressure from Wall Street.11 A rising focus on financial results at the expense of the customer experience was percolating through the company. The top management felt stressed by the need to exceed quarterly profit projections to keep Wall Street analysts happy.

This focus trickled down to dilute the customer experience. In one store, the manager excitedly told Schultz about cuddly toys’ high profit margins, and how they added to the store’s gross.12 To Schultz, the man seemed totally oblivious of Starbucks’ founding mission.

Starbucks was “no longer celebrating coffee.” 13 Coffee beans were no longer ground in-store but delivered ready to brew. The result: the smell of coffee had all but disappeared from Starbucks stores. All too often replaced by the smell of burning cheese!

Introduced in 2003, sandwiches quickly became popular with customers and were highly profitable, increasing the percentage of the company’s revenue from sales of food from 13 percent in 2003 to 17 percent in 2007. But it proved impossible to warm cheese sandwiches without the smell wafting through the stores.

Schultz wanted them banished—and was in no mood to compromise.

This became, symbolically as well as actually, a highly divisive issue within the company. Management split into two camps: those pointing to the immediate financial benefits, which were inarguable; and those who, like Schultz, felt those benefits were short-term, coming at the much-higher long-term price of losing Starbucks’ reason for existing.

In February 2007, Schultz shared his concerns in a memo titled “The Commoditization of the Starbucks Experience,” which he sent to Starbucks’ “most senior leaders.”14 A few extracts illustrate that his primary concern was (and remains) the customer experience:

I am not sure people today even know we are roasting coffee. You certainly can’t get the message from being in our stores.… Some stores don’t have coffee grinders, French presses … or even coffee filters.…

[We] desperately need to look into the mirror and realize it’s time to get back to the core and make the changes necessary to evoke the heritage, the tradition, and the passion that we all have for the true Starbucks experience. [Emphasis added.]15

By the end of that year comparable-store sales “dropped to levels we had not seen in years,”16 and the financial arguments lost their force; in January 2008, Howard Schultz returned to the position of CEO.

Restoring the Customer Experience

Among Schultz’s earliest acts as CEO was to banish those cheese sandwiches. Other ventures unrelated to the “Starbucks experience”—such as selling books, music, toys, and producing movies—were also wound down. But those changes were minor compared to what was to become Schultz’s “Transformational Agenda.”

Announced the day of Schultz’s return in a companywide e-mail titled “The Transformation of Starbucks,” his plan rested on three pillars:

• Improve the current state of the US retail business.

• Reignite the emotional attachment with customers.

• Make long-term changes to the foundation of Starbucks’ business.17

Over the following months, the agenda was developed from what Schultz termed “navigational guidelines” into a complete reinstatement of Starbucks’ mission and values, and a series of concrete actions that would bring them to life, the first of which was:

Own or Starting a Business? Why You Should Read Onward

What could the “Starbucks experience” have to do with a small company or a start-up?

More than you’d think. You can easily apply, with little adaptation, Howard Schultz’s plan for the transformation of Starbucks into a design for your own business, whatever it may be.

And if you’re starting from zero, his outline enables you to get it right from day one.

What’s more, the problems Starbucks faced are a cautionary tale every business owner should take to heart, illustrating the dangers that can arise from losing your focus and succumbing to the hubris of success.

Bringing back great coffee. In a bold move, on 26 February 2008, Starbucks stores across the United States closed their doors at 5:30 p.m. The purpose: to retrain baristas in the art of making the perfect espresso and espresso-related drinks. Schultz was concerned that in the name of efficiency, practices such as resteaming milk for cappuccinos (a definite no-no) had devalued the quality of Starbucks’ core coffee products.

He also wanted to bring back coffee’s romance.

Baristas watched a short film on one of the seventy-one hundred DVDs and DVD players the company had shipped, which went into the intricacies of preparing the perfect espresso. At the end, Schultz made it clear that if a barista felt the drink was less than perfect, “they had my permission to pour it out and begin again.”18

Reinspiring partners. As a result of the turmoil within the company, store closures, layoffs, and skepticism about Starbucks’ future—especially from Wall Street analysts—“Starbucks was losing not just money but also our partners’ trust.”19

Schultz felt the only way to overcome this disquietude, to recover partners’ enthusiasm, and to recommit them to Starbucks’ underlying vision was in person.

So on Sunday, October 26, 2008, ten thousand Starbucks partners—including eight thousand store managers—arrived in New Orleans for a weeklong conference.

Schultz and the company came under renewed fire for the $30 million cost of this gathering—a touchy-feely investment with no obvious, computable return to number crunchers at a time when the company’s US retail operations were in trouble. Schultz admitted that it was risky,20 and the week before the conference began, Starbucks’ stock traded at its lowest-ever price: $7.06—a mere third of the $21 recorded when Starbucks became a public company in 1992.

The leadership conference included workshops and panels, four “huge interactive galleries designed to bring Starbucks’ mission, values, operations, and store-management skills to life,”21 and involvement in the community as Starbucks’ partners helped rebuild some of New Orleans’s still-devastated neighborhoods. It culminated in a highly emotional general session in which management and partners alike recommitted themselves to the Starbucks mission and values.

At the end of the week, ten thousand partners returned to their posts, galvanized by their experience, and spread the meme companywide.

Devolving authority. Taking a page from John Mackey’s (then-yet-to-be-written) book Conscious Capitalism, frontline staff were empowered to make more operational decisions without reference to the head office. One example: when in-store partners stepped back to observe themselves from the customer’s point of view, they came up with significant organizational improvements that made the stores more efficient—and their job easier. These ideas were readily, if not eagerly, accepted by baristas in other stores, coming as they did from their peers rather than from the top down.

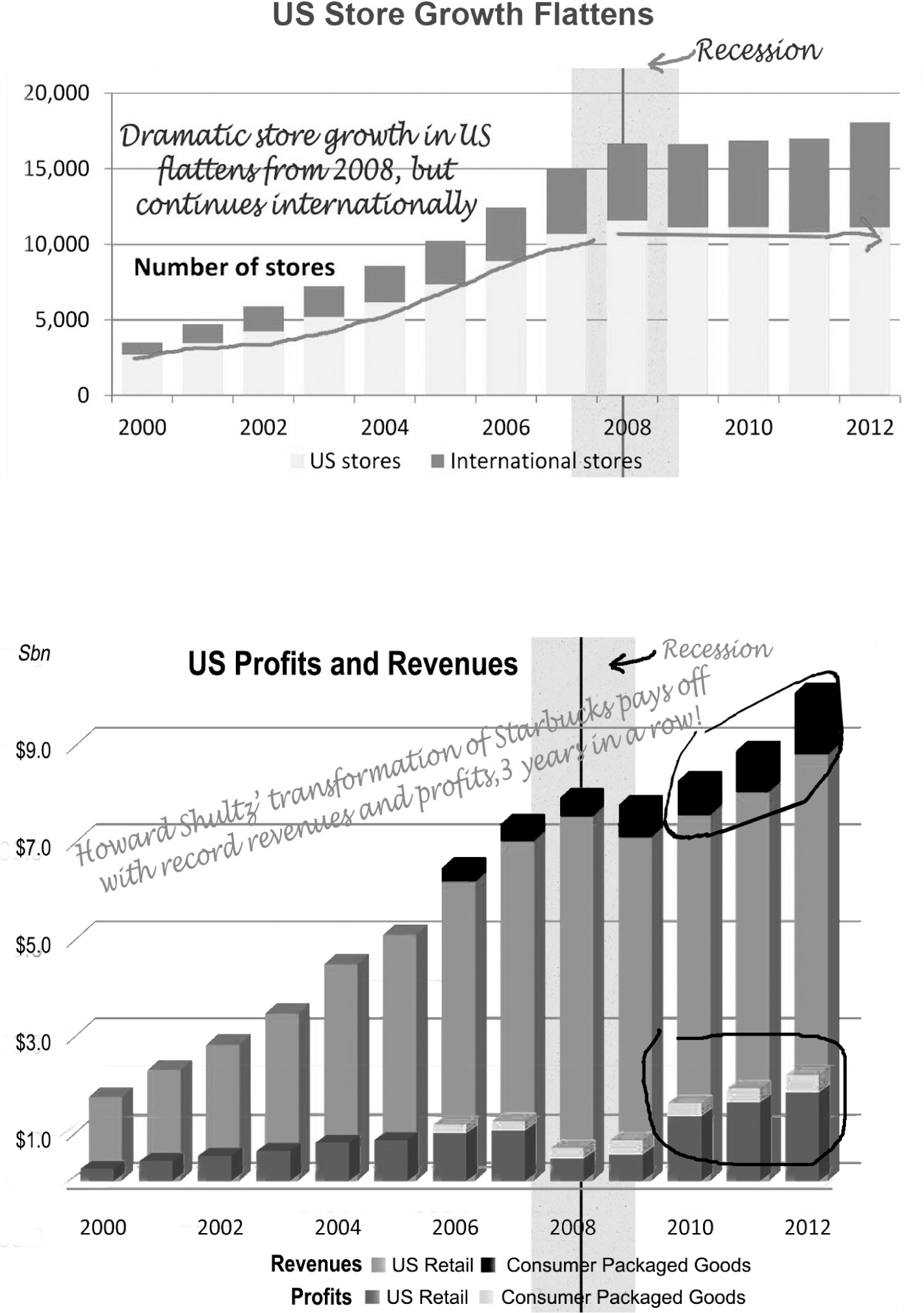

Expanding Starbucks’ coffee “footprint” by introducing new products in line with its core mission. Most significant: VIA Ready Brew, introduced in 2009, and Starbucks coffee pod system, the K-Cup, introduced in 2012.

These two new products account for most of the growth in the Consumer Products Group’s sales, which—as you can see from the chart that follows—have contributed approximately half the growth in the company’s US revenues since 2008.

Some other examples include purchasing the Clover company, opening several experimental espresso cafés in Seattle to test different store designs and product offerings, including one serving wine, expanding the Tazo Tea line, and the purchase of premium-tea retailer Teavana Holdings Inc.

These are all components of Schultz’s focus on restoring Starbucks’ mission, and the customer experience. But he did not ignore—

The Bottom Line

One consequence of the growing focus on pleasing Wall Street: costs had gotten out of control. The problem wasn’t obvious until revenues plateaued and began to decline.

A major area of neglect within the company: the supply chain, which had failed to keep up with the helter-skelter expansion of Starbucks stores. This became critical in September 2008 when all stores in the St. Louis area ran out of Ethos water—and the warehouses that supplied them had zero stock!

Two years later, 90 percent of store orders were fulfilled perfectly, compared to 35 percent in 2008, and supply-chain costs had been cut by a cumulative $400 million.

The financial results tell the story—before and after.

Sources: Starbucks stock price and S&P 500: Yahoo! Finance. All other data: Starbucks annual reports, 2000–2012 (http://investor.starbucks.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=99518&p=irol-reportsannual).

Consumer packaged goods—reported as a separate revenue stream from 2006—includes worldwide sales of products such as VIA Ready Brew, whole beans, and bottled Frappuccinos, sold through non-Starbucks outlets such as supermarkets. However, only a small portion of these sales are made outside the United States.

Note: In 2012, Starbucks restructured reporting of retail activities from United States and International to Americas; Europe, Middle East, and Africa (EMEA); and China/Asia Pacific (CAP). So with the exception of store numbers, “US” figures for 2012 are for the “Americas” group. (Courtesy of author)

A powerful example of how a tight focus on a company’s underlying vision ultimately flows through to the bottom line.

But successful implementation requires that short-term consequences be ignored in order to achieve long-term results. Although this management strategy has proven successful in companies as diverse as Berkshire Hathaway, Apple, and IBM, such companies are often penalized by Wall Street’s insane focus on short-term quarter-to-quarter results.

It’s a crying shame that supposed “professional money managers” fail to recognize that the power of vision is a fundamental key to long-term business and investment success.