As a rule, the entrepreneurs who start a high-growth company are the ones who make the highest returns from it. Howard Schultz, John Mackey, Sam Walton, and Ray Kroc all turned their initial investment of, at most, a few hundred thousand dollars (plus many years of dedication, hard work, and, inevitably, twenty-four-hour days) into multibillion-dollar fortunes that put them on the Forbes 500 list.

The people who make almost as much money from a successful start-up are the investors who back the entrepreneurial founders at the beginning. So even if you have absolutely no interest in ever starting or owning a business yourself, walking through the process the successful founder follows helps you identify a strong candidate for the next Starbucks—while it’s still on the ground floor.

So let’s, temporarily, put ourselves in the shoes of someone whose intention is to start the next Starbucks (or Google), take the copycat route, or just have his or her own show. And see how applying the five clues to a start-up enables a new business to open its doors with all the essential ingredients to dramatically increase the chances of success.

As a reminder, here’s a quick—

“Recipe” for Starting Your Own

1. Identify an underserved market niche.

2. Define the vision and mission that will motivate customers, employees, investors, and other stakeholders. The bigger the vision, the better: if you want to hit the moon, aim for the stars.

3. Create a compelling customer experience.

4. Develop a system, with the focus on the customer experience, to ensure that experience is consistent across all locations (and enable your business to be run by nineteen-year-olds).

5. Even if you have only one location (e.g., online), you still need to ensure that the customer experience is consistent 24/7.

6. The previous four components will combine into what will become the company’s culture: the accepted way of doing things (to define culture simply).

7. Mental attitude and commitment. Years of unremitting effort and twenty-four-hour days go into the creation of a new business—with no guarantee of success. Climbing Mount Everest—though far more hazardous to your health—takes just a couple of months. But it can be years before the entrepreneur who creates a business from nothing is fully rewarded, so only someone who is highly motivated, powerfully committed to his goal—and hungry—has a chance of staying the course.

8. Finally, to qualify as a candidate for the next Starbucks, the business needs to be scalable with, at least potentially, a high ratio of owner earnings to the capital investment required for expansion, and have superb entrepreneurial management.

I came to see, in my time at IBM, that [a company’s] culture isn’t just one aspect of the game—it is the game.1

—Louis V. Gerstner Jr., the CEO who turned IBM around

Outside Looking In

As potential investors in a start-up, we’re looking for the same qualities, but with a different emphasis.

Bill Gross, founder of the venture capital firm Idealab, which has been involved in more than a hundred start-ups, thinks the key factor is the founding team.

The strongest correlation to success has been the founding team—much more than the idea, or the amount of money raised, or almost anything else I can think of. The best successes came when there were at least two strong people, with opposite but complementary skills, who had a great deal of mutual trust and respect for one another.… If I see a complementary team like that, I would try to find almost any way to work with them. [Emphasis added.]2

Gross could have been describing one of the most successful start-ups of all time: Apple Computer. A company synonymous with Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. Jobs was the visionary and salesman; “the Woz,” the developer/executioner.

This underlying theme of two (or, at most, three) founders who trust, respect, and are open and honest with each other seems to be a common factor in successful start-ups—according to a number of venture capitalists.*

Between them, the founders need to fill (or hire) the following roles:

Visionary: the driving force behind a growth company. The visionary is usually also the salesman or “hustler” who inspires and persuades employees, customers, investors, suppliers, and other stakeholders to come on his board. Howard Schultz, John Mackey, Sam Walton, and Ray Kroc all fall into this category.

Manager: the person with the “execution skill” who creates and delivers the product or service that fulfills the vision.

People person: to hire, retain the right people—and make sure they work as a team.

Administrator: to maintain smooth operations as the company grows.

That these are remarkably similar to the five “differences that make the difference” between a good company and a great one should hardly come as a surprise.

So when you find this combination of skills in the founders of a start-up, then you can have much greater confidence in its chances of success.

Develop Your Own Concept …

If you want to start your own business, where should you begin?

The first answer to this question is—anywhere.

You could start with a product idea, a manufacturing process, a sales or marketing method—or even a completely different kind of store design.

Investing on the Ground Floor

One way to get in on the ground floor of a start-up is when you know (or, like Harry Fruehauf, who became 50 percent owner of Burger King, can get to know) the founder(s).

Whether you think you’ve found a potential stock market flier, or simply a small business that could turn into a cash cow, to have reasonable certainty of making a profit you need to be able to realistically and objectively judge the founders’ abilities.

And as a partner in the business in its start-up phase, as one of the founders’ “coaches,” you can help keep them (and your money) on the right track.

You could look for a tailwind—a business niche that appears to be about to explode; follow your passion wherever it may lead; jump on a bandwagon—or perhaps you are a highly independent person who hates the idea of having a boss so any of the above will serve (though customers can often be far more demanding “bosses” than any CEO).

In other words, when developing the underlying concept of a business, it doesn’t matter where you begin.

But come the planning stage, building a great business requires a totally different perspective: begin at the end rather than the beginning.

Surprisingly, it’s rather like writing a novel.

A great novel requires a great ending, one that leaves you on a high, wishing the story went on for another hundred pages. Best to figure out THE END before you start writing page one.

In business, THE END is a customer experience so compelling that people walk out the door determined to come back.

… or Stumble Across the Next Starbucks

Alternatively, you could strike it lucky and follow in the footsteps of Harry Axene and Ray Kroc. Neither developed the original concept for the companies associated with their names: Dairy Queen and McDonald’s.

Instead, they literally stumbled over them.

Kroc had his introduction through the McDonald brothers’ purchase of eight MultiMixers. Axene’s discovery of Dairy Queen was a pure accident.

In 1944, while on a family visit to East Moline, Illinois, Axene, then a farm-equipment salesman for Allis-Chalmers, drove past a store and was intrigued by the long lines of customers he saw. “What are they selling, nylon stockings?” Axene asked his sister, referring to the scarcest product of the war. “No,” she replied. “That’s Dairy Queen.”3

The first Dairy Queen opened on 22 June 1940, in Joliet, Illinois, and by summer’s end had grossed $4,000 ($54,360 in 2016 dollars!). By 1942, there were eight Dairy Queens. But as materials were diverted into the war effort, the company’s expansion ground to a halt.

Impressed by Dairy Queen’s popularity and the product, Axene approached the owners and became a partner, later buying nationwide franchising rights.

In November 1946, he presented the profit potential of a Dairy Queen franchise to a group of twenty-six Chicago investors. The clincher was the investors’ reaction to samples of the product: they all loved it. He then knew “he had a product that nearly sold itself.”4

Which it did: all twenty-six investors were ready to put money on the table for an exclusive franchise. Some for whole states.

Axene was delighted to accommodate them, selling territories for between $25,000 and $50,000.

The bottom line: Kroc was sold on McDonald’s and Axene on Dairy Queen by the customer experience. Both their own, but even more important the behavior of others.

Ultimately, everything revolves around the customer experience. So if you ever stumble across something that blows you away, it may well be worth discovering whether it offers a business or investment opportunity.

For example, while I was staying in Melbourne a few years back, I went to an Italian restaurant for dinner simply because it was right near my hotel.

My meal began with the best Greek salad I have ever had, followed by a pasta dish I had never heard of before that was equally superb. After that I simply had to try their tiramisu.

It was divine.

No question: next time I’m in Melbourne, I’ll be back.

When you stumble across a customer experience of this kind, one that sticks in your mind, then you may have discovered a concept that could be the basis of a substantial business.

Creative Copycatting

As we have seen, most highly successful businesses are copycats.

Even when a business is begun with an entirely new concept, it’s a lot easier to be like Sam Walton and study and copy what other people are doing than it is to reinvent the wheel.

You can apply this same process when developing your own business concept. Somewhere in the world someone has probably started a business something like the one you are thinking of.

The Internet makes it easy to find out.

You’ll inevitably come across some highly unusual, if not weird, ideas that have proven successful. In half an hour I came up with these examples:

Lollypotz: expensive ($40 up to $100+: www.lollypotz.com.au) but beautifully packaged chocolate gifts delivered to your door. A combination of franchised outlets (some of them home businesses) and online ordering.

This Australian company has outlets in New Zealand—and a Web site in Ireland (www.lollypotz.ie) where you can order for delivery in Ireland and the UK.

Leather Doctor: There are actually two Leather Doctors: in Australia (www.myleatherdoctor.com.au), a franchised leather-cleaning and leather-restoration service; and in the United States an online store (www.leatherdoctor.com) offering a wide range of leather-cleaning products.

Metal Supermarkets: a Canadian company expanding into the United States (www.metalsupermarkets.com) that offers “Any metal. Any size.” Eight thousand different types, shapes, and sizes.

So take heart: if you think your business idea is off-the-wall, there’s bound to be a business somewhere in the world that makes your concept seem straitlaced by comparison.

A second way is to copy the principle rather than the business.

Consider Airbnb.

As at Expedia and Travelocity, at Airbnb you can book rooms pretty much anywhere in the world. Not hotel rooms, but spare rooms in somebody’s house, or whole apartments.

This was not a new idea: you could achieve the same aim on classified-ad Web sites such as Craigslist.

But, like eBay, which made it easy to monetize secondhand goods, Airbnb founders Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia harnessed the network effect to offer travelers more options and enable people to monetize unused space.

And, like eBay, which resulted in thousands of people starting businesses devoted to buying and selling secondhand items, thousands of people now own apartments for the sole purpose of renting them out on Airbnb.

In 2009, a year and a half after Airbnb was founded, Uber came into existence. Like Airbnb, Uber monetizes unused or partially used assets—in this case, automobiles.

Both Airbnb and Uber almost immediately inspired copycats. FlipKey, HomeAway, VacationRentals, and VRBO—of thousands of Airbnb copycats—are the main ones; while Lyft and Grab are Uber’s main competitors.

More recently, this same principle has been copycatted to moving (mober.ph—“If you own a van, be a Mober”) and package delivery, using travelers as delivery agents (muber.com—“Airbnb for package delivery,” which at the time of writing still wasn’t off the ground, even though founded in 2013.*)

Whether you develop your own concept, stumble across a winning idea, or copy an existing business, the customer experience remains the key to ultimate success.

So before investing a dime, put on your “customer’s hat” and in your imagination walk through the experience you want your customers to have when they buy from you. An experience that will communicate your vision and mission.

Following this exercise you’ll be able to note (and note down!) every aspect of the product and service you want to provide.

Working backward, you can then develop the system that will enable you to deliver that customer experience.

How the McDonald Brothers Perfected Their System

In 1952, American Restaurant Magazine ran a cover story trumpeting the enormous success of the brothers’ San Bernardino restaurant.

The result was a flood of inquiries, which led to their first licensing arrangement with a businessman from Phoenix.

The brothers decided to make this new store a model for future McDonald’s stores.

On their tennis court at home, they sketched out the kitchen design for the new restaurant. That evening, after their store had closed, the night crew came over and went through the motions of making, assembling, and serving hamburgers, milk shakes, and so on. The brothers followed them, marking the best places to locate all the kitchen equipment.5

By 3:00 a.m., they had a design that dramatically improved the efficiency of their Speedee Service System.

When designing your business, follow the McDonald brothers’ example.

Do more than simply imagine what it would look and feel like. Literally walk through it. First, as a customer. Then from the other side of the counter.

Continue working (or, should I say, “walking”) through all the steps you’ll need to take to turn your initial concept into a reality.

Applying similar “3-D processing” to every aspect of the business, from the underlying concept through vision and mission to the customer experience, and via system, management, and financing, back again, will dramatically improve your chances of success.

Too many new businesses falter or fail through lack of planning—like someone going on a business trip who hops on a plane, wanders around the destination looking for a hotel room, and then starts calling people he wants to meet (only to find they’re out of town).

Not something you’d ever do, right?

Planning, booking, and making appointments ahead of time lead to a smooth, successful, and time-efficient outcome.

Inevitably, you’ll make mistakes. By planning ahead in as much detail as possible, you’ll make far fewer mistakes. And be in a much better position to correct the ones you do make.

An alternative travel option is to buy an “off the shelf” travel package with airfare, hotel, sightseeing, and most everything else included. The business equivalent: becoming a franchisee (addressed in the next chapter).

Why Do You Want to Start a Business?

Clarifying your underlying motivation and defining your objectives—two sides of the same coin—can make it far easier to develop your vision, business concept, and even the managerial structure.

Nearly everyone who starts a business does so from one (or both) of two fundamentally different motivations:

1. Fulfilling Your Passion

That’s what just about everybody recommends. Indeed, it’s hard to find anyone who advises it’s better to start a business that you are not passionate about.*

No question. There’s nothing like doing what you love to do—and getting paid for it.

And as Ray Kroc, Sam Walton, Howard Schultz, John Mackey, Steve Jobs, Warren Buffett, and hundreds of others who’ve created Fortune 500 companies from nothing have proven, it can be a sure avenue to success.

The disadvantage of following your passion can be that you find it difficult, if not impossible, to delegate key tasks. After all, nobody else can perform them as well as you, right?

This may not prevent you from starting a successful and profitable business, but without the ability to delegate everything, including those creative tasks that are so close to your heart—you know, the ones you can always do better—chances are you’ll create a one-man band.

2. Follow the Money

An equally (if not more) powerful motivation is money, as the Brazilian model demonstrates (here).

When money is your prime objective, it can be far easier to focus on all the requirements of creating a successful business without being married to any specific aspect of it.

Whichever business model you choose, the biggest problem you will face is you.

For example, my own management flaw is delegation. My first business, an investment newsletter titled World Money Analyst, was a one-man show.

I had no problem delegating routine tasks, such as processing orders or updating the mailing list. But when it came to anything to do with writing, whether an issue of the newsletter or marketing materials, the buck stopped with me. I was the bottleneck. The more projects I took on, the slower everything happened.

The business was profitable, but its profitability was far outpaced by other people in the same business who were able to do what I was not: delegate successfully.

After I sold the World Money Analyst I teamed up with two friends and we started another newsletter business. One that was far more successful and far more profitable. My delegation problem was no longer a hindrance. All three of us had considerable experience in newsletter publishing, and the division of labor resulted in each of us doing what we were best at.

In the six years I was involved in this partnership, my one-third share of the profits added up to far more money than I’d made in the seventeen years of being a “one-man band.”

So if, like me, you find it hard to delegate, find partners or employees whose strengths are your weaknesses, and vice versa.

If delegation is not your weakness, something else is bound to be. Perhaps you’re impetuous. Find a partner who needs a lot of convincing before he’ll move. If you’re focused on the big picture, you need someone who’s going to handle the nitty-gritty. And so on.

In a one-man show, you can do everything yourself—except grow really big.

A business can be compared to a financially successful marriage: one person is in charge of making money; the other spouse is in charge of not spending it.

In a partnership, you are no longer in full control; with the right partner (or partners) your deficiency or deficiencies are easily overcome.

Figure out your strengths and weaknesses and find partners or employees who complement your strengths and cover your weaknesses. Otherwise, one day when you feel you’re about to hit the big time, those weaknesses will suddenly bite you in the you-know-what.

The Two Kinds of Motivation

The essential character trait for success is total commitment, and that kind of commitment can only come from a powerful motivation.

Types of motivation can be divided into two broad classes:

• Away from

• Toward

For example, if you’re motivated by the desire to get out of poverty, what happens when you succeed?

When you’ve accumulated “enough” money—whether a hundred thousand or a million dollars—then that motivation will no longer drive you.

An “away from” motivation has an expiry date.

Unless you acquired that away-from motivation as the result of a formative experience. For example, in 1944 Nazi Germany occupied Hungary. As a Jew and a teenager, George Soros spent the next twelve months hiding from the Nazis.

Surviving.

Years, and billions of dollars later, Soros admitted he had a “bit of a phobia” about being penniless again. As his son Robert recalled, “He talked all the time about survival. It was pretty confusing considering the way we were living” (overlooking Central Park).6

Similarly, a “toward” motivation can also have an expiry date—unless it is effectively unachievable. If you set out to change the world, that’s such a large goal that it’s unlikely anyone can achieve it in one lifetime.

Clarifying your motivations, dividing them into “away from” and “toward,” and determining whether they are perpetual or come with a use-by date, is a powerful exercise.

While a long-term goal can be a continual source of motivation, in the meantime you have to show up at the office every day. Including those days when so much has gone wrong you may begin to doubt that you’ll ever achieve your ultimate goal.

Getting Paid for Having Fun

Whatever your motivation, if a major source of day-to-day satisfaction comes from the process—from what you’re doing, from the journey rather than the goal—and when it feels like just plain fun, then, like Warren Buffett, you’ll “tap-dance to work.”

The most powerful combination of all is getting paid for having fun, together with powerful “toward” and “away from” motivations.

Have the Courage of Your Convictions

You think you’ve got a great business idea, so you start testing it by seeing what your friends and family think.

Pretty quickly you’ll find that they just don’t get it. Nearly all their comments are negative. Quite likely, even people who sound supportive, even encouraging, show by their body language that they don’t really believe it will work.

It’s easy to be put off by universal criticism. But it could be a mistake.

Psychologist Nathaniel Branden told the story of meeting a penniless twenty-one-year-old “kid” who’d just arrived in New York.

“What brought you to New York?” Branden asked.

“I’m going to make a million dollars on Wall Street,” said the kid.

“You’ll never do that.”

Obviously, the probability of someone without two dimes to rub together turning them into a million dollars in the stock market is so close to zero it’s hardly worth considering.

But it’s not zero, and before his thirtieth birthday the net worth of this “kid” was seven figures and counting, all made from buying and selling stocks on Wall Street on his own account.

From that experience, Branden learned to never again cast doubt on anyone’s ambitions, no matter how seemingly unrealistic they might be.7

Handling Rejection

When almost universally negative, criticism can be highly discouraging. So it’s crucial that you resist the possibly overwhelming pressure to give up.

Your family and friends may all be right, but only you, not they, have any real understanding of the opportunity you see. Especially when your concept is only half-formed, so your explanation may come across as half-baked.

Most people aren’t business oriented. So asking them to comment on a business idea is rather like a surgeon asking a patient to evaluate a new surgical procedure.

Useless information.

But everyone over the age of three is an expert customer. So never ask your friends to comment on your business idea. Instead, ask questions related to the customer experience.

Here are three possible approaches to experiment with:

1. Describe the customer experience you have created—and ask for reactions.

For this to work, you must first create a description of the customer experience you imagine that’s compelling and emotionally involving, so your listeners can visualize and feel it.

Consider the original GoPro camera, which early on was described as “a camera you can wear underwater.”

Put that way, to people who aren’t surfers or divers it sounds like a crazy idea.

As an experiment, I rephrased the slogan as “a Dick Tracy–style camera you strap on your wrist: just point and click—even underwater.” When I tested this line on a few friends, most could immediately imagine and feel the experience of wearing and using it. Though it may not be perfect—“Dick Tracy” does date me somewhat ☺.

This approach diverts the focus from the business to a product, making its potential appeal immediately understandable.

2. Base the customer experience on an existing brand “with this” and / or “without that.”

For example: “Would you like a café like Starbucks with a dedicated indoor smoking section?”

Smokers (a totally underserved, even if shrinking, market these days) will love you.

Or, given that thanks to menu bloat, drive-through lines at McDonald’s in the United States sometimes go around the block, how about a drive-through McDonald’s clone that promises “No waiting!”

3. Invite family and friends to brainstorm how they could make your concept (or brand X) better.

This is, perhaps, the simplest approach of all—when properly conducted. And the easiest way is to follow a proven format:

Brainstorming—the Walt Disney Way

Let’s say you’re thinking of starting a Starbucks clone. To involve people in brainstorming your concept, instead of telling them what you have in mind, ask an open-ended question like “What might make Starbucks better?”

Inevitably, you’ll get some weird suggestions. “Baristas in bikinis” was the first one that came up when I tried this with a few friends.

Crazy? Maybe—or maybe not.

What normally happens when someone throws up an off-the-wall idea like that is someone else immediately shoots it down.

That’s a mistake: the Critic, especially the loudmouthed one, can shut down everyone else’s creative thinking.

Instead, by following Walt Disney’s Creative Strategy (see next page) the critic in all of us must wait his turn: last. Letting the creative juices flow could lead to something interesting. For example:

“Well, there’s Hooters.”

“Right. But for a coffee shop? Maybe in resort areas. Florida, Bahamas, Surfers Paradise…”

“How about the Hawaiian Café?”

Immediately, we have a different, non-Starbucks image.

“And what would the guys wear? Bikinis, too?”

“Tank tops.”

“Hey, no fair! Swimming trunks.”

“Maybe the girls could wear sarongs.”

And so on.

Is this a marketable concept?

Possibly. But at this stage that question is decidedly not the point. In just a few minutes, the question “What might make Starbucks better?” produced a completely different and possibly intriguing idea.*

How many similar concepts could you come up with if you “dreamed” for just one hour?

Whichever approach you take, asking questions that inspire people to answer from their perspective as a customer harnesses their creativity and can get them excitedly involved in refining your original concept.

By comparison, the question “What do you think of this business idea?” invites a person’s internal Critic to come to the fore.

Market Research

A final step is to “test” the idea without spending a whole lot of money.

If your idea is in an existing market niche, the process is relatively simple: market research.

Walt Disney’s Creative Strategy

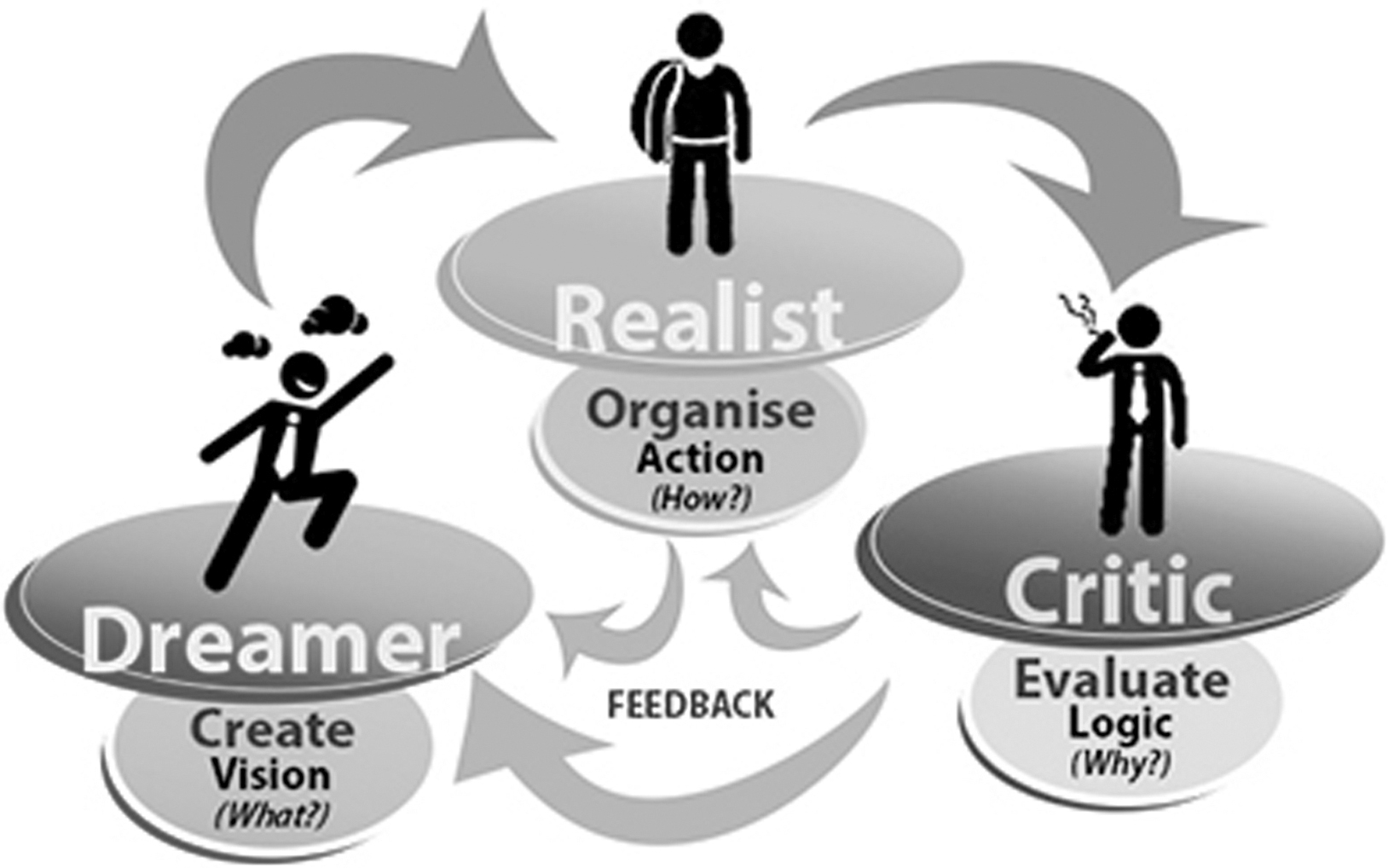

The Disney Strategy is a process developed by Robert Dilts, who applied NLP “modeling” to the way Walt Disney went about developing his movies. From concept to product.

Dreamer: begin by imagining as much as you can about your concept—how it and the product might look, feel, taste, and so on.

Realist: step away from the Dreamer’s position and look back at the Dreamer’s construct. Your task here is to figure out how it could work.

Critic: step far away so you’re looking back at what the Dreamer and the Realist have produced as if you were a third, unrelated person—and tear it apart.

At each stage, you can step back into the previous position(s) to incorporate any necessary adjustments.

Robert Dilts explains the process in more detail at www.nlpu.com/Articles/article7.htm.

As we’ve noted, the espresso revolution is far from over. So if you have the idea for an upscale coffee café—meaning a $7 instead of $4 latte—then it is easy to discover that several such companies with that same concept are prospering in many different parts of the world.

But what if your idea is something that seems completely different?

Experiment in your target market.

The GoPro camera originated when Nick Woodman, an extreme-sports enthusiast, decided he wanted to be able to show his surfing exploits to his friends.

On an extended surfing vacation, exploring Indonesian and Australian beaches, Woodman used a disposable Kodak camera to test various straps that would hold it to his wrist to make snapping pictures easier. Ideally, almost automatic.

Surrounded by surfers, he presumably received valuable feedback on his concept. On this trip he met his future partner, Brad Schmidt, who focused Woodman’s attention on the need for a durable camera, one that would survive the pounding of the waves as well as saltwater corrosion.8

A “Soft Opening”

Market research and the feedback you get from floating your business idea can provide valuable input to developing and refining your concept. But one crucially important factor is missing: nobody, yet, has actually put money on the table to buy what you plan to offer.

So before rounding up enough capital to open your first location, you need a real market test.

For example, Howard Schultz tested his espresso café concept in a corner of the original Starbucks store. Dairy Queen’s developers—John Fremont “Grandpa” McCullough, and his son Alex—tested their soft-serve ice cream in a friend’s ice cream store. When they sold over sixteen hundred servings in just two hours, they knew they had a winner.

Trade shows focused on your target market can be a good venue for such a market test. Nick Woodman made the first sales of his GoPro camera at an action-sports trade show in San Diego in September 2004.9 A market test that proved his concept in spades.

No matter if everybody raves about your business idea, you still need to find a relatively inexpensive way to discover if people are going to part with their hard-earned cash to have it—from you.

Financing the Idea

Taking the idea from concept to market requires money. Money that usually has to be raised from investors.

For many start-ups, family, friends, and acquaintances are a second source of debt or equity capital after the founders’ own resources.

When Ray Kroc, James McLamore, and Sam Walton started their businesses, the next steps up the “capital ladder” were private bond issues of the kind Harry Sonneborn arranged, finding an “angel investor” such as Burger King’s Harry Fruehauf, going public, or selling to a larger corporation.

The Zero-Capital Start-up

The ideal situation is to start a business with no capital whatsoever.

Is that possible?

Almost. Some capital is always needed, but it can be as little as a few thousand or a few hundred dollars.

That’s how I started the investment newsletter that grew into the World Money Analyst.

I was writing a book and had completed a section on inflation when a friend of mine suggested we publish that part. Which we did: Understanding Inflation was a forty-page minibook (self-published before there was self-publishing) with an initial order of five thousand copies from my partner. (And I never finished the book.)

“I’ve Never Known a Business to Succeed That Had Enough Money”

That’s according to Leon Richardson, founder of Magna Industrial (introduced here).

With not enough money, Richardson told me, founders are forced to economize and be creative to stretch the resources they have available. Too often, companies that have “enough” money in their early years spend $2 when $1 would be enough. As a result, when they hit a speed bump, they have neither the resources nor the nous to survive it.

I put an ad in the back for an investment newsletter. Twelve people sent in $100 each; suddenly I had $1,200 to start the business.

Cash-Flow Financing

Such cash-flow management is a common source of extra financing. It can occur anytime a sale is made before the product has to be paid for.

This arrangement enabled Amazon to begin with zero investment in inventory. Ingram, one of America’s two biggest book distributors, had a warehouse in Roseburg, Oregon. Amazon opened its doors in nearby Seattle. “When Amazon started, they were able to take a customer’s order and money; order and receive the book from Ingram and deliver it to the customer, and then sit on the cash for a while before they had to pay Ingram for the book.”10

Float

An even better form of cash-flow financing is float. Think of magazine and other subscriptions, Starbucks’ and similar loyalty cards, American Express traveler’s checks, and insurance of any kind.

What they all have in common is that customers pay in advance for the product or service. Until that product is delivered, the company has the use of the money. What’s more, the profit from those future sales is already in the bank.

As Warren Buffett describes float in the insurance industry: “If premiums exceed the total of expenses and eventual losses, we register an underwriting profit that adds to the investment income produced from the float. This combination allows us to enjoy the use of free money—and, better yet, get paid for holding it.” [Emphasis added.]11

Those avenues are still open. But over the past forty years, a sea change in the world’s capital markets has made it far easier for start-ups to raise money.

Venture Capital

Forty years ago there were no “venture capitalists” sitting on large pools of risk capital searching for the next Big Thing.

Today, with billions of dollars in venture capital funds looking for new small companies that could become big, finding equity capital is much easier. And its ready availability has changed the way businesses grow.

A driving force in the expansion of venture capital was the Internet. Profiting from the “network effect” requires significant risk capital to finance the losses in growing such a business to a “critical market mass”: the point where the network effect becomes a virtuous positive-feedback circle that will lead to profitability.

The Surge in Risk Capital

In the 1980s, the creation of a new form of risk capital, junk bonds, spurred a surge in leveraged buyouts. By 2012, $498 billion had gone into LBOs.

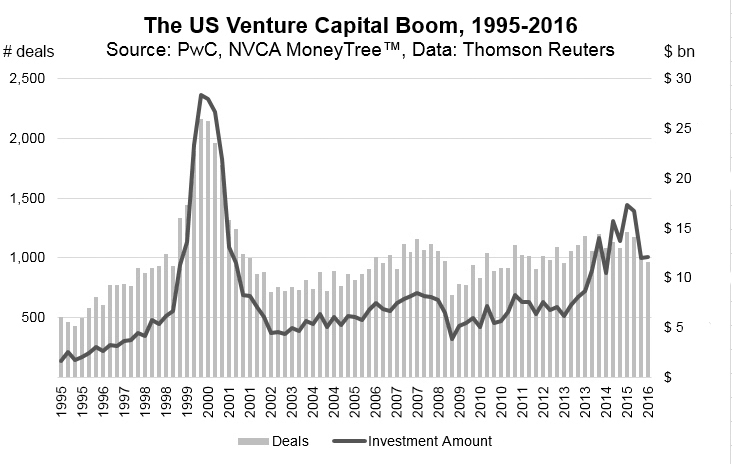

In the 1990s, an even larger source of risk capital was added to the pool: venture capital.

From 1995 to 2015, a massive $647.8 billion (an average of $31.6 billion per year, and thirteen hundred times the junk bond/LBO boom) had been invested in thousands of start-ups.

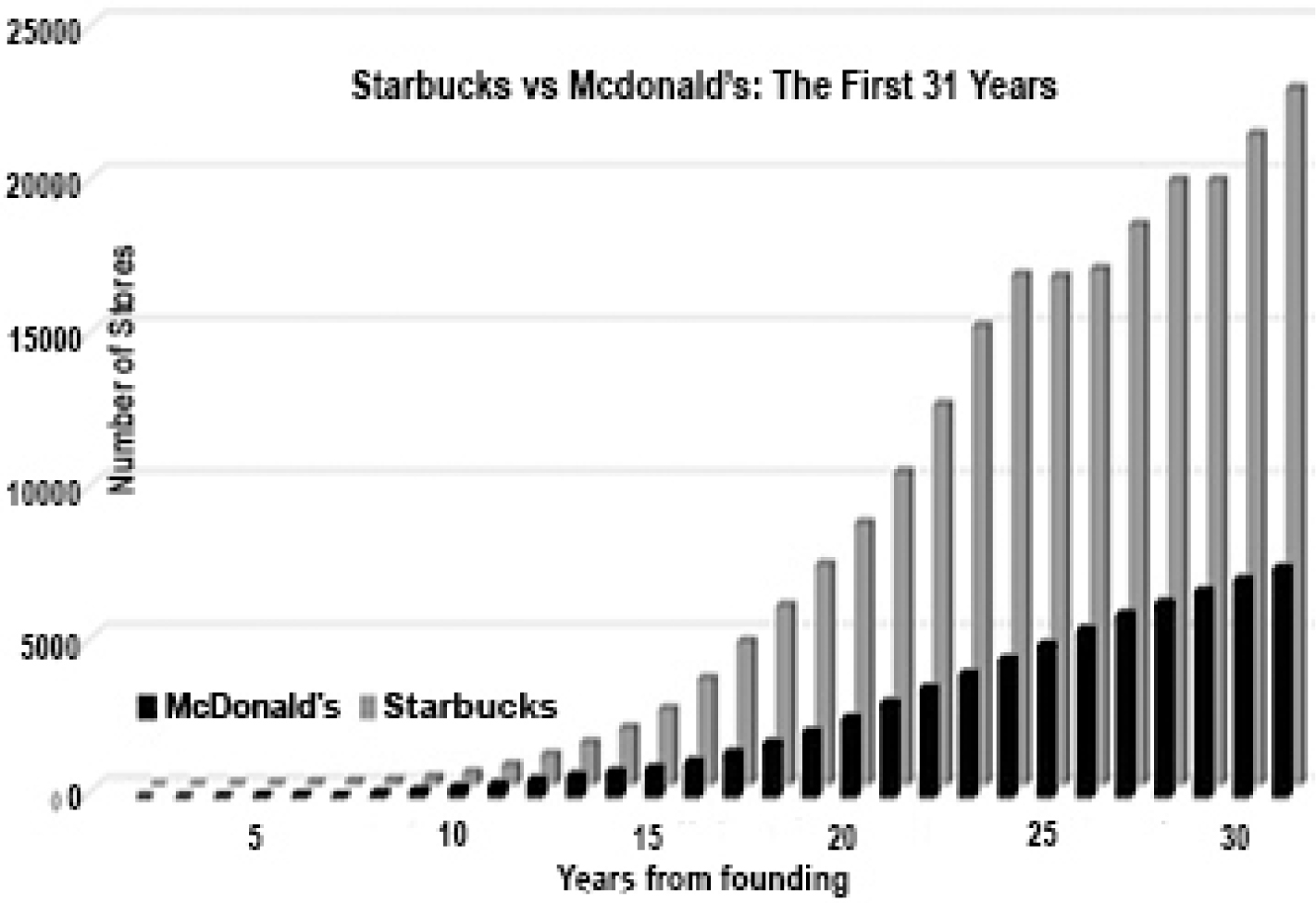

Although kicked off by the Internet boom, this larger pool of capital seeking profitable start-ups has also changed pre-Internet-style bricks-and-mortar businesses, a change dramatically illustrated by the growth trajectories of McDonald’s and Starbucks in their respective start-up phases. Thirty-one years after being founded (Howard Schultz’s Starbucks: 1985, as Il Giornale; Ray Kroc’s McDonald’s: 1954) Starbucks, with over twenty-one thousand stores, was three times bigger than McDonald’s, with “only” seventy-five hundred outlets.

The scarcity of risk capital and the difficulty of finding it in the 1950s resulted in McDonald’s focusing on the franchising model, thus attracting third parties to put up expansion capital—initially, one store at a time.

By contrast, from the beginning most Starbucks stores were company owned. Not just “at home”: while Starbucks more often than not enters foreign markets in a joint venture with a local partner, it will later increase its ownership to 100 percent, as it has done in Japan and China. Or, in countries that have a local-country franchisee, purchase an equity interest—as happened in 2013 when it bought 49 percent of Starbucks Spain.

And Starbucks sources, develops, and manufactures or acquires companies that make most of the products offered and much of the equipment used in its outlets. With mostly company-owned stores, Starbucks doesn’t have the conflict of interest that made Ray Kroc decide to completely avoid that practice himself.

In sum, by owning both stores and suppliers, Starbucks required far more capital than McDonald’s. Nevertheless, the greater availability of capital enabled the relatively greater capital-hungry Starbucks to grow three times faster:

The greater availability of the risk capital was not the sole cause of Starbucks’ faster expansion rate. For one thing, the median American household’s disposable income had almost doubled between the 1950s and ’90s. And Starbucks targeted the high end of the market while McDonald’s focus was and is remaining low-priced.

On the other hand, when McDonald’s started, it was moving into what was essentially a void in the food-service market, while Starbucks faced significantly more competition for consumers’ attention.

That said, other recently formed chains such as Chipotle and Pret A Manger have been able to finance their expansion from debt and/or equity markets while spurning the franchising model in favor of wholly owned stores.

Harnessing the Network Effect

Although our primary focus has been on retailers, exactly the same principles apply to the growth and development of Internet-based ventures that depend for their success on capitalizing on the network effect.

For such a company to become profitable it must first build a critical market mass of customers and suppliers—a size where the network effect takes over to drive further growth.

But how to reach that point?

It’s a bit like asking, “Which comes first, the chicken or the egg?”

There are two different formats:

• The Google/Facebook/Twitter model, which depends on building a wide customer base that can be monetized later.

• The eBay/Airbnb/Uber model, where, in order to have customers they must first have suppliers—and in order to have suppliers they must first have customers.

In both models, substantial financing is required to reach the point of profitability. With no guarantee that point will be reached. Twitter, for example, is still losing money—and losing more money—two years after its IPO. Even though its user base is still expanding.

To reach the “profit point,” it’s necessary to build first, build fast (to keep first mover advantage)—and monetize later.

In either approach, the founders must first build a model that’s scalable. One that can be rolled out quickly when the concept reaches a “critical market mass.”

Today, the existence of thousands of venture capital funds makes it far easier to raise start-up capital for any business concept. But their existence can also dramatically increase the competition every new start-up faces.

Crowdfunding

The advent of crowdfunding takes cash-flow management financing to a new level.

While crowdfunding can be used to offer equity (with severe limits depending on the jurisdiction), the most common model is “rewards funding.” In return for providing what is risk capital, you will receive something—when (and if) the project takes off.

Usually, the something is the product the company wants to finance.

Pebble Watch turned to crowdfunding when it was unable to raise any further money from venture capital investors. It offered a $150 smartwatch to anyone who put up $115—an effective 23.3 percent discount. The target of $100,000 was reached in just two hours. Six days later it reached a then-record $4.7 million for a Kickstarter campaign, closing out at $10.3 million.12

This money enabled the company to produce the product—while at the same time providing the perfect market test that proved the demand was there.

Similarly, M3D raised $3,401,361 from 11,855 backers to produce its Micro 3D printer,13 while Oculus Rift raised $2.4 million for its virtual-reality headset—and was later bought by Facebook for $2 billion.14 Which all went to the founders!

A successful crowdfunding results in an injection of risk capital—without giving away a single share of equity.

The key is to reward your funders with a product that gives them value for money—whether that be the specific product under development or, in the case of a retailer, say the right to buy $700 or even $1,000 of merchandise for every $500 in funding.

The Power of Marketing

Marketing and sales are two different (and complementary) sides of the same coin.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the legendary copywriter Claude Hopkins defined advertising as “salesmanship in print.” The advent of radio, TV, and the Internet have extended that definition to all forms of broadcasting, but not changed the essence of Hopkins’s meaning.

Advertising is a subset of marketing: sales at a distance. Marketing is impersonal in the sense that only the potential buyer is present.

Sales, by comparison, is interactive: a one-on-one (or small-group) exchange between the seller and the buyer.

The success of the Whopper in turning around Burger King’s fortunes is a stunning testament to the power of marketing.

McDonald’s answered the Whopper with the Quarter Pounder and the Big Mac, while Burger Chef introduced the Big Shef. But none of these other names have the same marketing impact as “the Whopper,” which suggests a mouthwatering treat even if you don’t like hamburgers.

Such is the power of a name that Burger King’s CFO, Joshua Kobza, noted that when Burger King returned to France in 2012, after an absence of fifteen years, “They still remember the Whopper.… We walked through the airport with Burger King logos on our shirts. The security people asked us, ‘Where’s the Burger King?’”15

Kroc was a salesman. His forte was one-on-one selling, honed from years of visiting kitchens and food-service managers around the United States. In the beginning, McDonald’s grew one location at a time through personal contact from Kroc and his associates.

Eventually, as McDonald’s grew, it, too, turned to marketing—as every large business must.

Word of Mouth

Ultimately, the most powerful form of marketing is word of mouth. Which results from a highly satisfactory customer experience.

But before word of mouth can become a factor, there must first be customers to spread that word. One way to get those first customers is to harness the power of marketing.

For example, after dinner at an exceptionally good Thai restaurant, my friend came up with what we both agreed was a great name for a Thai restaurant: Red Hot Mama’s.

A little brainstorming expanded the concept:

![]()

with dishes ranging from Medium through Hot—to Nuclear.

And to juice up business on a slow night, how about:

MAMA’S RED HOT CHALLENGE

Blow Your Mind!

Every Tuesday Night

Eat the Mostest of the Hottest and It’s on the House

Sound interesting?

Not if you don’t like it hot.

Which is part of the idea: telegraphing what your business stands for means you only attract customers who are potential buyers for your product. No one’s going to walk into Red Hot Mama’s asking, “What kind of food do you serve?”

Every newly opened business is an unknown to consumers. Selecting the right name, one that includes your USP (marketing shorthand for “Unique Selling Proposition”), telegraphs what you’re about, turns your storefront or Web site into an advertisement that works for you 24/7. At no extra charge.*

But remember: for sales and marketing to result in a long-run payoff—customers who keep coming back for more—it’s crucial that the customer experience lives up to the marketing message. Otherwise word of mouth will have a negative effect.

It’s always best to underpromise and overdeliver.