1.11. Dimensional Analysis

Interestingly, a physical quantity’s units may be exploited to learn about its relationship to other physical quantities. This possibility exists because the natural realm does not need mankind’s units of measurement to function. Natural laws are independent of any unit system imposed on them by human beings. Consider Newton’s second law, generically stated as force = (mass) × (acceleration); it is true whether a scientist or engineer uses cgs (centimeter, gram, second), MKS (meter, kilogram, second), or even US customary (inch or foot, pound, second) units in its application. Because nature is independent of our systems of units, we can draw two important conclusions: 1) all correct physical relationships can be stated in dimensionless form, and 2) in any comparison, the units of the items being compared must be the same for the comparison to be valid. The first conclusion leads to the problem-simplification or scaling-law-development technique known as dimensional analysis. The second conclusion is known as the principle of dimensional homogeneity. It requires all terms in an equation to have the same dimension(s) and thereby provides an effective means for error catching within derivations and in derived answers. If terms in an equation do not have the same dimension(s) then the equation is not correct and a mistake has been made.

Dimensional analysis is a broadly applicable technique for developing scaling laws, interpreting experimental data, and simplifying problems. Occasionally it can even be used to solve problems. Dimensional analysis has utility throughout the physical sciences and it is routinely taught to students of fluid mechanics. Thus, it is presented here for subsequent use in this chapter’s exercises and in the remaining chapters of this text.

Of the various formal methods of dimensional analysis, the description here is based on Buckingham’s method from 1914. Let q1, q2, …, qn be n variables and parameters involved in a particular problem or situation, so that there must exist a functional relationship of the form

(1.42)

(1.42)

Buckingham’s theorem states that the n variables can always be combined to form exactly (n − r) independent dimensionless parameter groups, where r is the number of independent dimensions. Each dimensionless parameter group is commonly called a “Π-group” or a dimensionless group. Thus, (1.42) can be written as a functional relationship:

(1.43)

(1.43)

The dimensionless groups are not unique, but (n − r) of them are independent and form a complete set that spans the parameteric solution space of (1.43). The power of dimensional analysis is most apparent when n and r are single-digit numbers of comparable size so (1.43), which involves n – r dimensionless groups, represents a significant simplification of (1.42), which has n parameters. The process of dimensional analysis is presented here as a series of six steps that should be followed by a seventh whenever possible. Each step is described in the following paragraphs and illustrated via the example of determining the functional dependence of the pressure difference Δp between two locations in a round pipe carrying a flowing viscous fluid.

Step 1. Select Variables and Parameters

Creating the list of variables and parameters to include in a dimensional analysis effort is the most important step. The parameter list should usually contain only one unknown variable, the solution variable. The rest of the variables and parameters should come from the problem’s geometry, boundary conditions, initial conditions, and material parameters. Physical constants and other fundamental limits may also be included. However, shorter parameter lists tend to produce the most powerful dimensional analysis results; expansive lists commonly produce less useful results.

For the round-pipe pressure drop example, select Δp as the solution variable, and then choose as additional parameters: the distance Δx between the pressure measurement locations, the inside diameter d of the pipe, the average height ε of the pipe’s wall roughness, the average flow velocity U, the fluid density ρ, and the fluid viscosity μ. The resulting functional dependence between these seven parameters can be stated as:

(1.44)

(1.44)

Note, (1.44) does not include the fluid’s thermal conductivity, heat capacities, thermal expansion coefficient, or speed of sound, so this dimensional analysis example will not account for the thermal or compressible flow effects embodied by these missing parameters. Thus, this parameter listing embodies the assumptions of isothermal and constant density flow.

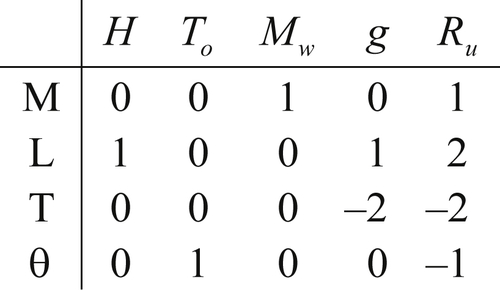

Step 2. Create the Dimensional Matrix

Fluid flow problems without electromagnetic forces and chemical reactions involve only mechanical variables (such as velocity and density) and thermal variables (such as temperature and specific heat). The dimensions of all these variables can be expressed in terms of four basic dimensions—mass M, length L, time T, and temperature θ. We shall denote the dimension of a variable q by [q]. For example, the dimension of the velocity u is [u] = L/T, that of pressure is [p] = [force]/[area] = MLT−2/L2 = M/LT2, and that of specific heat is [cp] = [energy]/[mass][temperature] = ML2T−2/Mθ = L2/θT2. When thermal effects are not considered, all variables can be expressed in terms of three fundamental dimensions, namely, M, L, and T. If temperature is considered only in combination with Boltzmann’s constant (kBθ), a gas constant (Rθ), or a specific heat (cpθ or cvθ), then the units of the combination are simply L2/T2, and only the three dimensions M, L, and T are required.

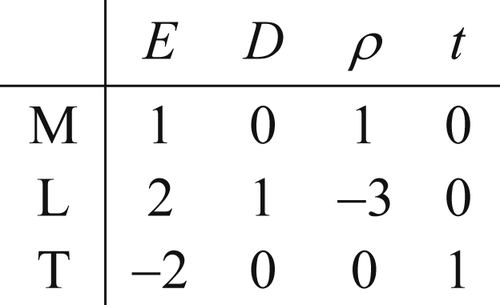

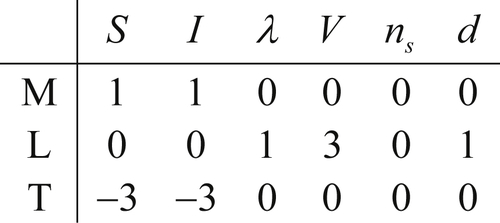

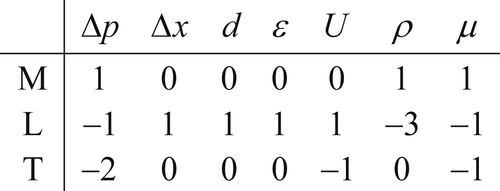

The dimensional matrix is created by listing the powers of M, L, T, and θ in a column for each parameter selected. For the pipe-flow pressure difference example, the selected variables and their dimensions produce the following dimensional matrix:

(1.45)

(1.45)where the seven variables have been written above the matrix entries and the three units have been written in a column to the left of the matrix. The matrix in (1.45) portrays [Δp] = ML–1T–2 via the first column of numeric entries.

Step 3. Determine the Rank of the Dimensional Matrix

The rank r of any matrix is defined to be the size of the largest square submatrix that has a nonzero determinant. Testing the determinant of the first three rows and columns of (1.45), we obtain

However, (1.45) does include a nonzero third-order determinant, for example, the one formed by the last three columns:

Thus, the rank of the dimensional matrix (1.45) is r = 3. If all possible third-order determinants were zero, we would have concluded that r < 3 and proceeded to testing second-order determinants.

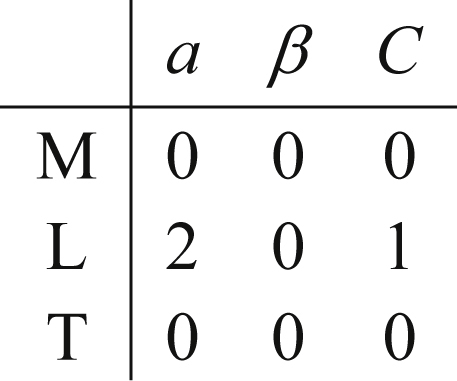

For dimensional matrices, the rank is less than the number of rows only when one of the rows can be obtained by a linear combination of the other rows. For example, the matrix (not from (1.45)):

has r = 2, as the last row can be obtained by adding the second row to twice the first row. A rank of less than 3 commonly occurs in statics problems, in which mass or density is really not relevant but the dimensions of the variables (such as force) involve M. In most fluid mechanics problems without thermal effects, r = 3.

Step 4. Determine the Number of Dimensionless Groups

The number of dimensionless groups is n – r where n is the number of variables and parameters, and r is the rank of the dimensional matrix. In the pipe-flow pressure difference example, the number of dimensionless groups is 4 = 7 – 3.

Step 5. Construct the Dimensionless Groups

This can be done by exponent algebra or by inspection. The latter is preferred because it commonly produces dimensionless groups that are easier to interpret, but the former is sometimes required. Examples of both techniques follow. Whatever the method, the best approach is usually to create the first dimensionless group with the solution variable appearing to the first power.

When using exponent algebra, select r parameters from the dimensional matrix as repeating parameters that will be found in all the subsequently constructed dimensionless groups. These repeating parameters must span the appropriate r-dimensional space of M, L, and/or T, that is, the determinant of the dimensional matrix formed from these r parameters must be nonzero. For many fluid-flow problems, a characteristic velocity, a characteristic length, and a fluid property involving mass are ideal repeating parameters.

To form dimensionless groups for the pipe-flow problem, choose U, d, and ρ as the repeating parameters. The determinant of the dimensional matrix formed by these three parameters is nonzero. Other repeating parameter choices will result in a different set of dimensionless groups, but any such alternative set will still span the solution space of the problem. Thus, any satisfactory choice of the repeating parameters is equvialent to any other, so choices that simplify the work are most appropriate. Each dimensionless group is formed by combining the three repeating parameters, raised to unknown powers, with one of the nonrepeating variables or parameters from the list constructed for the first step. Here we ensure that the first dimensionless group involves the solution variable raised to the first power:

The exponents a, b, and c are obtained from the requirement that Π1 is dimensionless. Replicating this equation in terms of dimensions produces:

Equating exponents between the two extreme ends of this extended equality produces three algebraic equations that are readily solved to find a = −2, b = 0, c = −1, so

A similar procedure with Δp replaced by the other unused variables (Δx, ε, μ) produces:

The inspection method proceeds directly from the dimensional matrix, and may be less tedious than exponent algebra. It involves selecting individual parameters from the dimensional matrix and sequentially eliminating their M, L, T, and θ units by forming ratios with other parameters. For the pipe-flow pressure difference example we again start with the solution variable [Δp] = ML–1T–2 and notice that the next entry in (1.45) that includes units of mass is [ρ] = ML–3. To eliminate M from a combination of Δp and ρ, we form the ratio [Δp/ρ] = L2T–2 = [velocity2]. An examination of (1.45) shows that U has units of velocity, LT–1. Thus, Δp/ρ can be made dimensionless if it is divided by U2 to find: [Δp/ρU2] = dimensionless. Here we have the good fortune to eliminate L and T in the same step. Therefore, the first dimensionless group is Π1 = Δp/ρU2. To find the second dimensionless group Π2, start with Δx, the left-most unused parameter in (1.45), and note [Δx] = L. The first unused parameter to the right of Δx involving only length is d. Thus, [Δx/d] = dimensionless so Π2 = Δx/d. The third dimensionless group is obtained by starting with the next unused parameter, ε, to find Π3 = ε/d. The final dimensionless group must include the last unused parameter [μ] = ML–1T–1. Here it is better to eliminate the mass dimension with the density since reusing Δp would place the solution variable in two places in the final scaling law, an unnecessary complication. Therefore, form the ratio μ/ρ which has units [μ/ρ] = L2T–1. These can be eliminated with d and U, [μ/ρUd] = dimensionless, so Π4 = μ/ρUd.

Forming the dimensionless groups by inspection becomes easier with experience. For example, since there are three length scales Δx, d, and ε in (1.45), the dimensionless groups Δx/d and ε/d can be formed immediately. Furthermore, Bernoulli equations (see Section 4.9, “Bernoulli Equations”) tell us that ρU2 has the same units as p so Δp/ρU2 is readily identified as a dimensionless group. Similarly, the dimensionless group that describes viscous effects in the fluid mechanical equations of motion is found to be μ/ρUd when these equations are cast in dimensionless form (see Section 4.11).

Other dimensionless groups can be obtained by combining esblished groups. For the pipe flow example, the group Δpd2ρ/μ2 can be formed from Π 1 / Π 4 2  , and the group ε/Δx can be formed as Π3/Π2. However, only four dimensionless groups will be independent in the pipe-flow example.

, and the group ε/Δx can be formed as Π3/Π2. However, only four dimensionless groups will be independent in the pipe-flow example.

, and the group ε/Δx can be formed as Π3/Π2. However, only four dimensionless groups will be independent in the pipe-flow example.

, and the group ε/Δx can be formed as Π3/Π2. However, only four dimensionless groups will be independent in the pipe-flow example.Step 6. State the Dimensionless Relationship

This step merely involves placing the (n – r) Π-groups in one of the forms in (1.43). For the pipe-flow example, this dimensionless relationship is:

(1.46)

(1.46)

where φ is an undetermined function. This relationship involves only four dimensionless groups, and is therefore a clear simplification of (1.42) which lists seven independent parameters. The four dimensionless groups in (1.46) have familiar physical interpretations and have even been given special names. For example, Δx/d is the pipe’s aspect ratio, and ε/d is the pipe’s roughness ratio. Common dimensionless groups in fluid mechanics are presented and discussed in Section 4.11.

Step 7. Use Physical Reasoning or Additional Knowledge to Simplify the Dimensionless Relationship

Sometimes there are only two extensive thermodynamic variables involved and these must be proportional in the final scaling law. An overall conservation law can be applied that restricts one or more parametric dependencies, or a phenomena may be known to be linear, quadratic, etc. in one of the parameters and this dependence must be reflected in the final scaling law. This seventh step may not always be possible, but when it is, significant and powerful results may be achieved from dimensional analysis.

Once the dimensionless groups have been identified, and the dimensionless law has been stated and possibly simplified, the resulting relationship can be used for similarity-scaling analysis between two or more different scenarios involving the same physical principles. For example, consider (1.46) the final dimensional analysis result for incompressible flow in a round rough-walled pipe. If Δx/d = 10, ε/d = 10–3, and μ/ρUd = 10–5, this could represent the flow of room temperature and pressure air at 15 m/s in a 0.10-m-diameter pipe over a distance of 1.0 m with a wall roughness of 100 μm. Alternatively it could represent, the flow of room temperature water at 10 m/s in a 1.0-cm-diameter tube over a distance of 0.10 m with a wall roughness of 10 μm. If Δp is measured in the air case to be 30 Pa, then the function in (1.46) can be evaluated for this condition: φ(10,10–3,10–5) = ( Δ p / ρ U 2 ) a i r = 30 P a / ( 1.2 k g m − 3 · ( 15 m s − 1 ) 2 ) = 0.11  . This value of φ, also applies to in the water case, Δpwater = φ(10, 10−3, 10−5)·(ρU2)water =

. This value of φ, also applies to in the water case, Δpwater = φ(10, 10−3, 10−5)·(ρU2)water = 0.11 ( 10 3 k g m − 3 · ( 10 m s − 1 ) 2 ) = 11 k P a  . Thus, quantitative knowledge of one situation immediately applies to the other through a relationship like (1.46). This is an illustration of the principle of dynamic similarity which is more fully discussed in Section 4.11.

. Thus, quantitative knowledge of one situation immediately applies to the other through a relationship like (1.46). This is an illustration of the principle of dynamic similarity which is more fully discussed in Section 4.11.

. This value of φ, also applies to in the water case, Δpwater = φ(10, 10−3, 10−5)·(ρU2)water =

. This value of φ, also applies to in the water case, Δpwater = φ(10, 10−3, 10−5)·(ρU2)water =  . Thus, quantitative knowledge of one situation immediately applies to the other through a relationship like (1.46). This is an illustration of the principle of dynamic similarity which is more fully discussed in Section 4.11.

. Thus, quantitative knowledge of one situation immediately applies to the other through a relationship like (1.46). This is an illustration of the principle of dynamic similarity which is more fully discussed in Section 4.11.