and the flux integral on the left in (7.54) is zero, so:

and the flux integral on the left in (7.54) is zero, so:7.5. Forces on a Two-Dimensional Body

In Section 3 the drag and lift forces per unit length on a circular cylinder in steady ideal flow were found to be zero and ρUΓ, respectively, when the circulation is clockwise. These results are also valid for any object with an arbitrary non-circular cross section that does not vary perpendicular to the x-y plane.

Blasius Theorem

Consider a stationary object of this type with extent B perpendicular to the plane of the flow, and let D (drag) be the stream-wise (x) force component and L (lift) be cross-stream or lateral (y) force (per unit depth) exerted on the object by the surrounding fluid. Thus, from Newton’s third law, the total force applied to the fluid by the object is F = –B(Dex + Ley). For steady irrotational constant-density flow, conservation of momentum (4.17) within a stationary control volume implies:

(7.54)

(7.54)

If the control surface A∗ is chosen to coincide with the body surface and the body is not moving, then u · n = 0  and the flux integral on the left in (7.54) is zero, so:

and the flux integral on the left in (7.54) is zero, so:

and the flux integral on the left in (7.54) is zero, so:

and the flux integral on the left in (7.54) is zero, so: (7.55)

(7.55)

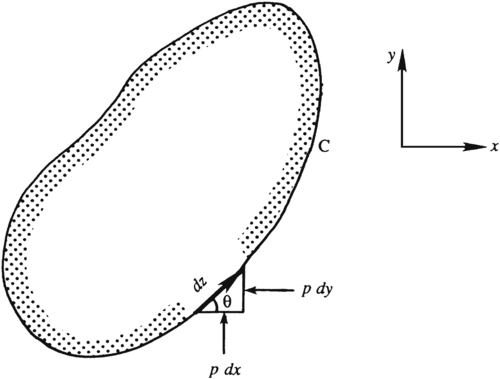

If C is the contour of the body’s cross section, then dA = Bds where ds = exdx + eydy is an element of C and ds = [(dx)2 + (dy)2]1/2. By definition, n must have unit magnitude, must be perpendicular to ds, and must point outward from the control volume, so n = (exdy – eydx)/ds. Using these relationships for n and dA, (7.55) can be separated into force components:

(7.56)

(7.56)

to identify the contour integrals leading to D and L. Here, C must be traversed in the counterclockwise direction.

Now switch from the physical domain to the complex z-plane to make use of the complex potential. This switch is accomplished here by replacing ds with dz = dx + idy and exploiting the dichotomy between real and imaginary parts to keep track of horizontal and vertical components (see Figure 7.18). To achieve the desired final result, construct the complex force:

(7.57)

(7.57)

where ∗ denotes a complex conjugate. The pressure is found from the Bernoulli equation (7.18):

where p∞ and U are the pressure and horizontal flow speed far from the body. Inserting this into (7.57) produces:

Figure 7.18 Elemental forces in a plane on a two-dimensional object. Here the elemental horizontal and vertical force components (per unit depth) are –pdy and +pdx, respectively.

(7.58)

(7.58)

The integral of the constant terms, p∞ + ρU2/2, around a closed contour is zero. The body-surface velocity vector and the surface element dz = |dz|eiθ are parallel, so (u + iv)dz∗ can be rewritten:

(7.59)

(7.59)

(7.60)

(7.60)

a result known as the Blasius theorem. It applies to any steady planar ideal flow. Interestingly, the integral need not be carried out along the contour of the body because the theory of complex variables allows any contour surrounding the body to be chosen provided there are no singularities in (dw/dz)2 between the body and the contour chosen.

Kutta-Zhukhovsky Lift Theorem

The Blasius theorem can be readily applied to an arbitrary cross-section object around which there is circulation –Γ. The flow can be considered a superposition of a uniform stream and a set of singularities such as vortex, doublet, source, and sink.

As there are no singularities outside the body, we shall take the contour C in the Blasius theorem at a very large distance from the body. From large distances, all singularities appear to be located near the origin z = 0, so the complex potential on the contour C will be of the form:

When U, qs, Γ, and d are positive and real, the first term represents a uniform flow in the x-direction, the second term represents a net source of fluid, the third term represents a clockwise vortex, and the fourth term represents a doublet. Because the body contour is closed, there can be no net flux of fluid into the domain. The sinks must scavenge all the flow introduced by the sources, so qs = 0. The Blasius theorem, (7.60), then becomes:

(7.61)

(7.61)

To evaluate the contour integral in (7.61), we simply have to find the coefficient of the term proportional to 1/z in the integrand. This coefficient is known as the residue at z = 0 and the residue theorem of complex variable theory states that the value of a contour integral like (7.61) is 2πi times the sum of the residues at all singularities inside C. Here, the only singularity is at z = 0, and its residue is iUΓ/π, so:

(7.62)

(7.62)

Thus, there is no drag on an arbitrary-cross-section object in steady two-dimensional, irrotational constant-density flow, a more general statement of d’Alembert's paradox. Given that non-zero drag forces are an omnipresent fact of everyday life, this might seem to eliminate any practical utility for ideal flow. However, there are at least three reasons to avoid this presumption. First, ideal flow streamlines indicate what a real flow should look like to achieve minimum pressure drag. Lower drag on real objects is often realized when object-geometry changes are made or boundary-layer separation-control strategies are implemented that allow real-flow streamlines to better match their ideal-flow counterparts. Second, the predicted circulation-dependent force on the object perpendicular to the oncoming stream – the lift force, L = ρUΓ – is basically correct. The result (7.62) is called the Kutta-Zhukhovsky lift theorem, and it plays a fundamental role in aero- and hydrodynamics. As described in Chapter 14, the circulation developed by an air- or hydrofoil is nearly proportional to U, so L is nearly proportional to U2. And third, the influence of viscosity in real fluid flows takes some time to develop, so impulsively started flows and rapidly oscillating flows (i.e., acoustic fluctuations) often follow ideal flow streamlines.