8.5. Group Velocity, Energy Flux, and Dispersion

A variety of interesting phenomena take place when waves are dispersive and their phase speed depends on wavelength. Such wavelength-dependent propagation is common for waves that travel on interfaces between different materials (Graff, 1975). Examples are Rayleigh waves (vacuum and a solid), Stonely waves (a solid and another material), or interface waves (two different immiscible liquids). Here we consider only air-water interface waves and emphasize deep water gravity waves for which c is proportional to λ .

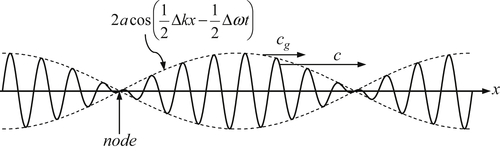

In a dispersive system, the energy of a wave component does not propagate at the phase velocity c = ω/k, but at the group velocity defined as cg = dω/dk. To understand this, consider the superposition of two sinusoidal wave components of equal amplitude but slightly different wave number (and consequently slightly different frequency because ω = ω(k)). The waveform of the combination is:

(8.66)

(8.66)

where the trigonometric identity for the sum of cosines of different arguments has been used, Δk = k2 − k1 and Δω = ω2 − ω1, k = (k1 + k2)/2, and ω = (ω1 + ω2)/2. Here, cos(kx − ωt) is a progressive wave with a phase speed of c = ω/k. However, its amplitude 2a is modulated by a slowly varying function cos(Δkx/2 − Δωt/2), which has a large wavelength 4π/Δk, a long period 4π/Δω, and propagates at a speed (wavelength/period) of:

(8.67)

(8.67)

where the approximate equality becomes full in the limit as Δk and Δω → 0. Multiplication of a rapidly varying sinusoid and a slowly varying sinusoid, as in (8.66), generates repeating wave groups (Figure 8.13). The individual wave crests (and troughs) propagate with the speed c = ω/k, but the envelope of the wave groups travels with the speed cg, which is therefore called the group velocity. If cg < c, then individual wave crests appear spontaneously at a nodal point, proceed forward through the wave group, and disappear at the next nodal point. If, on the other hand, cg > c, then individual wave crests emerge from a forward nodal point and vanish at a backward nodal point.

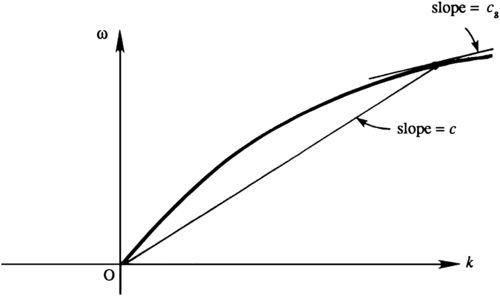

Equation (8.67) shows that the group speed of waves of a certain wave number k is given by the slope of the tangent to the dispersion curve ω(k). In contrast, the phase velocity is given by the slope of the radius or distance vector on the same plot (Figure 8.14).

Figure 8.14 Graphical depiction of the phase speed, c, and group speed, cg, on a generic plot of a gravity wave dispersion relation, ω(k) vs. k. If a sinusoidal wave has frequency ω and wave number k, then the phase speed c is the slope of the straight line through the points (0,0) and (k,ω). While the group speed cg is the tangent to the dispersion relation at the point (k,ω). For the dispersion relation depicted here, cg is less than c.

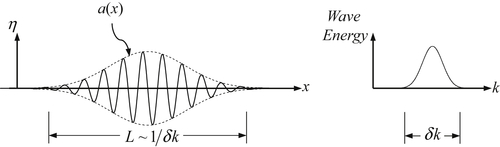

A particularly illuminating example of the idea of group velocity is provided by the concept of a wave packet, formed by combining all wave numbers in a certain narrow band δk around a central value k. In physical space, the wave appears nearly sinusoidal with wavelength 2π/k, but the amplitude dies away over a distance proportional to 1/δk (Figure 8.15). If the spectral width δk is narrow, then decay of the wave amplitude in physical space is slow. The concept of such a wave packet is more realistic than the one in Figure 8.13, which is rather unphysical because the wave groups repeat themselves. Suppose that, at some initial time, the wave group is represented by η = a(x)cos(kx). It can be shown (see, for example, Phillips, 1977, p. 25) that for small times, the subsequent evolution of the wave profile is approximately described by

(8.68)

(8.68)

where cg = dω/dk. This shows that the amplitude of a wave packet travels with the group speed. It follows that cg must equal the speed of propagation of energy of a certain wavelength. The fact that cg is the speed of energy propagation is also evident in Figure 8.13 because the nodal points travel at cg and no energy crosses nodal points because p' = 0 there.

For surface gravity waves having the dispersion relation (8.28), the group velocity is:

(8.69)

(8.69)

which has two limiting cases:

(8.70)

(8.70)

The group velocity of deep-water gravity waves is half the deep-water phase speed while shallow-water waves are non-dispersive with c = cg. For a linear non-dispersive system, any waveform preserves its shape as it travels because all the wavelengths that make up the waveform travel at the same speed. For a pure capillary wave, the group velocity is cg = 3c/2 (Exercise 8.9).

The energy flux for gravity waves is given by (8.44), namely:

(8.71)

(8.71)

where E = ρga2/2 is the average energy in the water column per unit horizontal area. This signifies that the rate of transmission of energy of a sinusoidal wave component is the wave energy times the group velocity, and reinforces the interpretation of the group velocity as the speed of propagation of wave energy.

In three dimensions, the dispersion relation ω = ω(k, l, m) may depend on all three components of the wave number vector K = (k, l, m). Here, using index notation, the group velocity vector is given by:

so the group velocity vector is the gradient of ω in the wave number space.

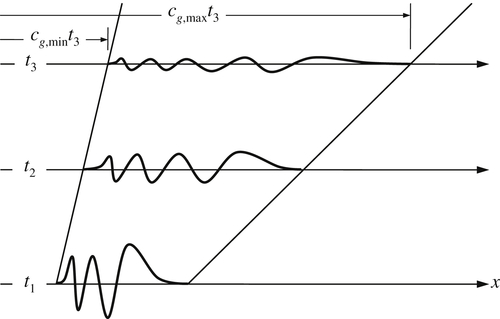

As mentioned in connection with (8.28) and (8.59), deep-water wave dispersion readily explains the evolution of the surface disturbance generated by dropping a stone into a quiescent pool, pond, or lake. Here, the initial disturbance can be thought of as being composed of a great many wavelengths, but the longer ones travel faster. A short time after impact, at t = t1, the water surface may have the rather irregular profile shown in Figure 8.16. The appearance of the surface at a later time t2, however, is more regular, with the longer components (which travel faster) out in front. The waves in front are the longest waves produced by the initial disturbance. Their length, λmax, is typically a few times larger than the dropped object. The leading edge of the wave system therefore propagates at the group speed of these wavelengths:

Of course, pure capillary waves can propagate faster than this speed, but they may have small amplitudes and are dissipated quickly. Interestingly, the region of the impact becomes calm because there is a minimum group velocity for water waves due to the influence of surface tension, namely cgmin = 17.8 cm/s (Exercise 8.10), and the trailing edge of the wave system travels at this speed. With cgmin > 17.8 cm/s for ordinary hand-size stones, the length of the disturbed region gets larger, as shown in Figure 8.16. The wave heights become correspondingly smaller because there is a fixed amount of energy in the wave system. (Wave dispersion, therefore, makes the linearity assumptions more accurate.) The smoothing of the waveform and the spreading of the region of disturbance continue until the amplitudes become imperceptible or the waves are damped by viscous dissipation (Exercise 8.12). It is clear that the initial superposition of various wavelengths, running for some time, will sort themselves from slowest to fastest traveling components since the different sinusoidal components, differing widely in their wave numbers, become spatially separated, with the slow ones closer to the point of impact and the fast ones further away. This is a basic feature of the behavior of dispersive wave propagation.

Figure 8.16 Generic surface profiles at three successive times of the wave train produced by dropping a stone into a deep quiescent pool. As time increases, the initial disturbance’s long-wave (low-frequency) components travel faster than its the short-wave (high-frequency) components. Thus, the wave train lengthens, the number of crests and troughs increases, and amplitudes fall (to conserve energy).

In the case of deep-water surface waves described here, the wave group as a whole travels slower than individual crests. Therefore, if we try to follow the last crest at the rear of the wave train, quite soon it is the second one from the rear; a new crest has appeared behind it. In fact, new crests are constantly appearing at the rear of the train, propagating through the wave train, and finally disappearing at the front of the wave train. This is because, by following a particular crest, we are traveling at roughly twice the speed at which the wave energy is traveling. Consequently, we do not see a wave of fixed wavelength if we follow a particular crest. In fact, an individual wave oscillation constantly becomes longer as it propagates through the train. When its length becomes equal to the longest wave generated initially, it cannot evolve further and disappears. The waves at the front of the train are the longest Fourier components present in the initial disturbance. In addition, the temporal frequencies of the highest and lowest speed wave components of the wave group are typically different enough so that the number of wave crests in the train increases with time.

Another way to understand the group velocity is to consider the k or λ determined by an observer traveling at speed cg with a slowly varying wave train described by:

(8.72)

(8.72)

in an otherwise quiescent pool of water with constant depth H. Here, a(x,t) is a slowly varying amplitude and θ(x,t) is the local phase. For a specific wave number k and frequency ω, the phase is θ = kx − ωt. For a slowly varying wave train, define the local wave number k(x,t) and the local frequency ω(x,t) as the rate of change of phase in space and time, respectively:

(8.73)

(8.73)

Cross-differentiation leads to:

(8.74)

(8.74)

but when there is a dispersion relationship ω = ω(k), the spatial derivative of ω can be rewritten using the chain rule, ∂ω/∂x = (dω/dk)∂k/∂x = cg∂k/∂x, so that (8.74) becomes:

(8.75)

(8.75)

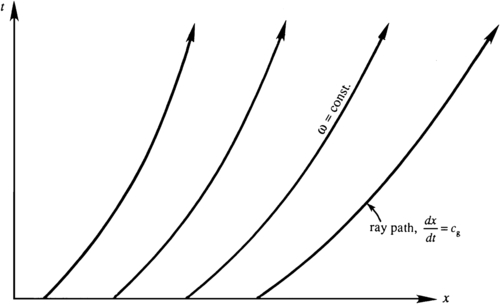

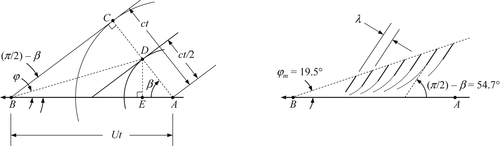

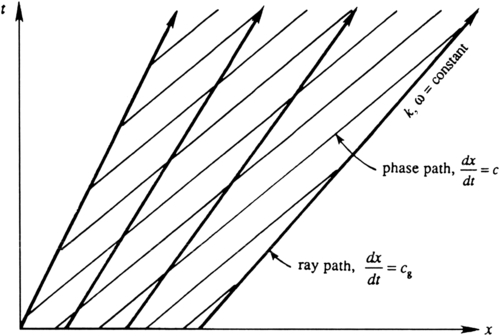

The left-hand side of (8.75) is similar to the material derivative and gives the rate of change of k as seen by an observer traveling at speed cg, which in this case is zero. Therefore, such an observer will always see the same wavelength. The group velocity is therefore the speed at which wave numbers travel. This is shown in the xt-diagram of Figure 8.17, where wave crests follow lines with dx/dt = c and wavelengths are preserved along the lines dx/dt = cg. Note that the width of the disturbed region, bounded by the first and last thick lines in Figure 8.17, increases with time, and that the crests constantly appear at the back of the group and vanish at the front.

Figure 8.17 Propagation of a wave group in a homogeneous medium, represented on an x-t plot. Thin lines indicate paths taken by wave crests, and thick lines represent paths along which k and ω are constant. M. J. Lighthill, Waves in Fluids, 1978, reprinted with the permission of Cambridge University Press, London.

Now consider the same traveling observer, but allow there to be smooth variations in the water depth H(x). Such depth variation creates an inhomogeneous medium when the waves are long enough to feel the presence of the bottom. Here, the dispersion relationship will be:

which is of the form:

(8.76)

(8.76)

Thus, a local value of the group velocity can be defined:

(8.77)

(8.77)

which on multiplication by ∂k/∂t gives:

(8.78)

(8.78)

(8.79)

(8.79)

In three dimensions, this implies:

which shows that ω, the frequency of the wave, remains constant to an observer traveling with the group velocity in an inhomogeneous medium.

Summarizing, an observer traveling at cg in a homogeneous medium sees constant values of k, ω(k), c, and cg(k). Consequently, ray paths describing the group velocity in the x-t plane are straight lines (Figure 8.17). In an inhomogeneous medium ω remains constant along the lines dx/dt = cg, but k, c, and cg can change. Consequently, ray paths are not straight in this case (Figure 8.18).