8.3. Influence of Surface Tension

As described in Section 1.6, the interface between two immiscible fluids is in a state of tension. The tension acts as another restoring force on surface deformation, enabling the interface to support waves in a manner analogous to waves on a stretched membrane or string. Waves that occur and propagate because of surface tension are called capillary waves. Although gravity is not needed to support these waves, the existence of surface tension alone without gravity is uncommon in terrestrial environments. Thus, the preceding results for pure gravity waves are modified to include surface tension in this section.

As shown in Section 4.10, there is a pressure difference Δp = σ(1/R1 + 1/R2) across a curved interface with non-zero surface tension σ when the surface’s principal radii of curvature are R1 and R2. The pressure is greater on the side of the surface with the centers of curvature of the interface, and this pressure difference modifies the free-surface boundary condition (8.19).

For straight-crested surface waves that produce fluid motion in the x-z plane, there is no variation in the y-direction, so one of the radii of curvature is infinite, and the other, denoted R, lies in the x-z plane. Thus, if the pressure above the liquid is atmospheric, pa, then pressure p in the liquid at the surface z = η can be found from (1.5):

(8.53)

(8.53)

where the second equality follows from the definition of the curvature 1/R and the final approximate equality holds when the liquid surface slope ∂η/∂x is small. As before we can choose p to be a gauge pressure and this means setting pa = 0 in (8.53), which leaves:

(8.54)

(8.54)

as the pressure-matching boundary condition at the liquid surface for small slope surface waves. As before, this can be combined with the linearized unsteady Bernoulli equation (8.20) and evaluated on z = 0 for small slope surface waves:

(8.55)

(8.55)

The linear capillary-gravity, surface-wave solution now proceeds in an identical manner to that for pure gravity waves, except that the dynamic boundary condition (8.21) is replaced by (8.55). This modification only influences the dispersion relation ω(k), which is found by substitution of (8.2) and (8.26) into (8.55), to give:

(8.56)

(8.56)

so the phase velocity is:

(8.57)

(8.57)

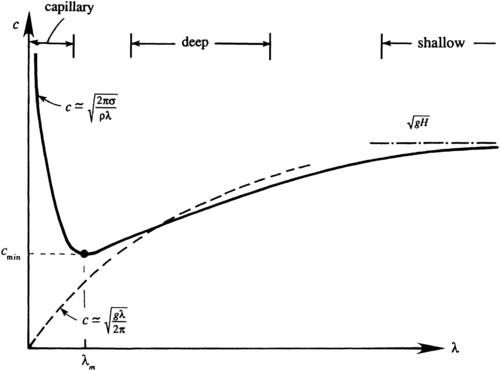

A plot of (8.57) is shown in Figure 8.10. The primary effect of surface tension is to increase c above its value for pure gravity waves at all wavelengths. This increase occurs because there are two restoring forces that act together on the surface, instead of just one. However, the effect of surface tension is only appreciable for small wavelengths. The nominal size of these wavelengths is obtained by noting that there is a minimum phase speed at λ = λm, and surface tension dominates for λ < λm (Figure 8.10). Setting dc/dλ = 0 in (8.57), and assuming deep water, H > 0.32λ so tan h ( 2 π H / λ ) ≈ 1  , produces:

, produces:

, produces:

, produces: (8.58)

(8.58)

For an air-water interface at 20°C, the surface tension is σ = 0.073 N/m, giving:

(8.59)

(8.59)

Therefore, only short-wavelength waves (λ < ∼7 cm for an air-water interface), called ripples, are affected by surface tension. The waves specified by (8.59) are readily observed as the wave rings closest to the point of impact after an object is dropped onto the surface of a quiescent pool, pond, or lake of clean water. Surfactants and surface contaminants may lower σ or even introduce additional surface properties like surface viscosity or elasticity. Water-surface wavelengths below 4 mm are dominated by surface tension and are essentially unaffected by gravity. From (8.57), the phase speed of pure capillary waves is:

Figure 8.10 Generic sketch of the phase velocity c vs. wavelength λ for waves on the surface of liquid layer of depth H. The phase speed of the shortest waves is set by the liquid’s surface tension σ and density ρ. The phase speed of the longest waves is set by gravity g and depth H. In between these limits, the phase speed has a minimum that typically occurs when the effects of surface tension and gravity are both important.

(8.60)

(8.60)

where again tanh(2πH/λ) ≈ 1 has been assumed.