9.5. Flows with Oscillations

The unsteady flows discussed in the preceding sections have similarity solutions because there were no imposed or specified length or time scales. The two flows discussed here are unsteady viscous flows that include an imposed time scale.

First, consider an infinite flat plate lying at y = 0 that executes sinusoidal oscillations parallel to itself. (This is sometimes called Stokes’ second problem.) Here, only the steady periodic solution after the starting transients have died out is considered, thus there are no initial conditions to satisfy. The governing equation (9.20) is the same as that for Stokes’ first problem. The boundary conditions are:

(9.33, 9.34)

(9.33, 9.34)

where ω is the oscillation frequency (rad./s). In the steady state, the flow variables must have a periodicity equal to the periodicity of the boundary motion. Consequently, a complex separable solution of the form:

(9.35)

(9.35)

is used here, and the specification of the real part is dropped until the final equation for u is reached. Substitution of (9.35) into (9.20) produces:

(9.36)

(9.36)

which is an ordinary differential equation with constant coefficients. It has exponential solutions of the form: f = exp(ky) where k = (iω/ν)1/2 = ±(i + 1)(ω/2ν)1/2. Thus, the solution of (9.36) is:

(9.37)

(9.37)

The condition (9.34) requires that the solution must remain bounded as y → ∞, so B = 0 and the complex solution only involves the first term in (9.37). The surface boundary condition (9.33) requires A = U. Thus, after taking the real part as in (9.35), the final velocity distribution for Stokes’ second problem is:

(9.38)

(9.38)

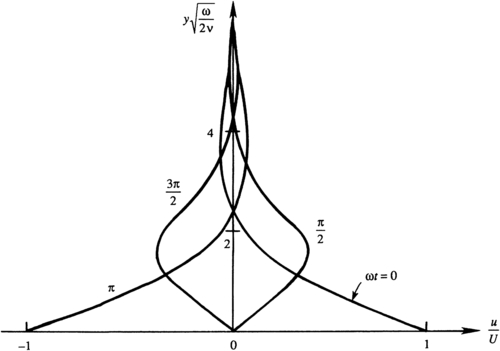

The cosine factor in (9.38) represents a dispersive wave traveling in the positive-y direction, while the exponential term represents amplitude decay with increasing y. The flow therefore resembles a highly damped transverse wave (Figure 9.16). However, this is a diffusion problem and not a wave-propagation problem because there are no restoring forces involved here. The apparent propagation is merely a result of the oscillating boundary condition. For y = 4(ν/ω)1/2, the amplitude of u is U exp { − 4 / 2 } = 0 . 06 U ,  which means that the influence of the wall is confined within a distance of order δ ∼ 4(ν/ω)1/2, which decreases with increasing frequency.

which means that the influence of the wall is confined within a distance of order δ ∼ 4(ν/ω)1/2, which decreases with increasing frequency.

which means that the influence of the wall is confined within a distance of order δ ∼ 4(ν/ω)1/2, which decreases with increasing frequency.

which means that the influence of the wall is confined within a distance of order δ ∼ 4(ν/ω)1/2, which decreases with increasing frequency.

Figure 9.16 Velocity distribution in laminar flow near an oscillating plate. The distributions at ωt = 0, π/2, π, and 3π/2 are shown. The diffusive distance is of order δ ∼ 4(ν/ω)1/2.

The solution (9.38) has several interesting features. First of all, it cannot be represented by a single curve in terms of dimensionless variables. A dimensional analysis of Stokes’ second problem produces three dimensionless groups: u/U, ωt, and y(ω/ν)1/2. Here the independent spatial variable y can be fully separated from the independent time variable t. Self-similar solutions exist only when the independent spatial and temporal variables must be combined in the absence of imposed time or length scales. However, the fundamental concept associated weith viscous diffusion holds true, the spatial extent of the solution is parameterized by (ν/ω)1/2, the square root of the product of the kinematic viscosity, and the imposed time scale 1/ω. In addition, (9.38) can be used to predict the weak absorption of sound at solid flat surfaces.

A second oscillating viscous flow with an exact solution occurs in a straight round tube with an oscillating pressure gradient (Womersley 1955a,b). The problem specification and the flow geometry are the same as that in Section 9.2 for steady laminar flow in a round tube with two exceptions. First, the unsteady term, ∂uz/∂t, in the axial momentum equation is retained:

(9.39)

(9.39)

because u = (0,0,uz(R,t)), and second, the pressure gradient oscillates at radian frequency ω:

(9.40)

(9.40)

where Δp is the pressure fluctuation amplitude between the ends of the pipe, and L is the pipe length (both are constants here). Substituting the equivalent of (9.35) for this geometry:

(9.41)

(9.41)

into (9.39) leads to:

(9.42)

(9.42)

This is a form of the zeroth-order Bessel equation. The solutions for f(R) are zeroth-order Bessel functions of complex argument with the radial coordinate R scaled by the diffusion distance (ν/ω)1/2:

where A and B are constants, and Jo and Yo are zeroth-order Bessel functions of the first kind. Here f(0) must be finite, so B must be zero since Yo grows without bound as it argument goes to zero argument. The remaining constant A can be determined from the no slip condition at r = a:

which leads to:

(9.43)

(9.43)

Even though evaluation of Bessel functions at arbitrary points in the complex plane requires special techniques (see Kurup & Koithyar, 2013), (9.43) does represent an exact solution of (4.10) and (9.1). It simplifies to the profile (9.6) in the limit as ω → 0  , and to an appropriate profile, similar to (9.38), in the limit as

, and to an appropriate profile, similar to (9.38), in the limit as ω → ∞  (see Exercise 9.32).

(see Exercise 9.32).

, and to an appropriate profile, similar to (9.38), in the limit as

, and to an appropriate profile, similar to (9.38), in the limit as  (see Exercise 9.32).

(see Exercise 9.32).