11.10. Results for Parallel and Nearly Parallel Viscous Flows

The dominant intuitive expectation is that viscous effects are stabilizing. The stability of thermal and centrifugal convections discussed in Sections 11.4 and 11.6 confirm this expectation. However, the actual situation is more complicated. Consider the Poiseuille-flow and Blasius boundary-layer velocity profiles in Figure 11.21. Neither has an inflection point so both are inviscidly stable. Yet, in experiments, these flows are known to undergo transition to turbulence at some Reynolds number, and this suggests that viscous effects are destabilizing in these flows. Thus, fluid viscosity may be stabilizing as well as destabilizing, a duality confirmed by stability calculations of parallel viscous flows.

Analytical solution of the Orr-Sommerfeld equation is notoriously complicated and will not be presented here. The viscous term in (11.79) contains the highest-order derivative, and therefore the eigenfunction may contain regions of rapid variation in which the viscous effects become important. Sophisticated asymptotic techniques are therefore needed to treat these boundary layers. Alternatively, solutions can be obtained numerically. For our purposes, we shall discuss only certain features of these calculations for the two-stream shear layer, plane Poiseuille flow, plane Couette flow, pipe flow, and boundary layers with pressure gradients. This section concludes with an explanation of how viscosity can act to destabilize a flow. Additional information can be found in Drazin and Reid (1981), and in the review article by Bayly, Orszag, and Herbert (1988).

Two-Stream Shear Layer

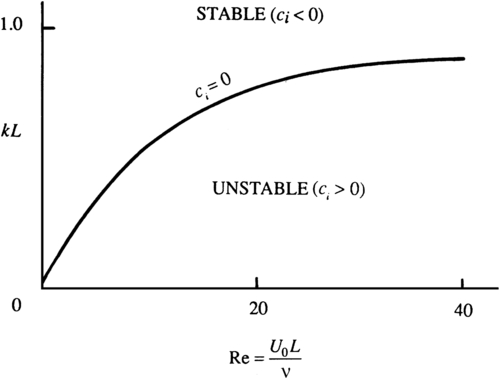

Consider a shear layer with the velocity profile U(y) = U0 tanh(y/L), so that U(y) → ±U0 as y/L → ±∞. This profile has its peak vorticity at its inflection point and is of the type shown in Figure 11.21f. A stability diagram for solution of the Orr-Sommerfeld equation for this velocity distribution is sketched in Figure 11.23. At all Reynolds numbers the flow is unstable to waves having low wave numbers in the range 0 < k < ku, where the upper limit ku depends on the Reynolds number Re = U0L/ν. For high values of Re, the range of unstable wave numbers increases to 0 < k < 1/L, which corresponds to a wavelength range of ∞ > λ > 2πL. It is therefore essentially a long-wavelength instability. In the limit kL → 0, these results simplify to those given in Section 11.3 for a vortex sheet.

Figure 11.23 Marginal stability curve for a shear layer with a velocity profile of U0tanh(y/L) in terms of the Reynolds number UoL/ν and the dimensionless wave number kL of the disturbance. This flow is only unstable to low wave number disturbances.

Figure 11.23 implies that the critical Reynolds number for the onset of instability in a shear layer is zero. In fact, viscous calculations for all flows with inflectional profiles show a small critical Reynolds number; for example, for a jet of the form u = Usech2(y/L), it is Recr = 4. These wall-free shear flows therefore become unstable very quickly, and the inviscid prediction that these flows are always unstable is a fairly good description. The reason the inviscid analysis works well in describing the stability characteristics of free shear flows can be explained as follows. For flows with inflection points the eigenfunction of the inviscid solution is smooth. On this zero-order approximation, the viscous term acts as a regular perturbation, and the resulting correction to the eigenfunction and eigenvalues can be computed as a perturbation expansion in powers of the small parameter 1/Re. This is true even though the viscous term in the Orr-Sommerfeld equation contains the highest-order derivative.

The instability in flows with inflection points is observed to form rolled-up regions of vorticity, much like in the calculations of Figure 11.6 or in the pictures in Figures 11.4 and 11.5. This behavior is robust and insensitive to the detailed experimental conditions. They are therefore easily observed. In contrast, the unstable waves in a wall-bounded shear flow are extremely difficult to observe, as discussed in the next section.

Plane Poiseuille Flow

The flow in a channel with a parabolic velocity distribution has no point of inflection and is inviscidly stable. However, linear viscous calculations show that the flow becomes unstable at a critical Reynolds number of 5780. Nonlinear calculations, which consider the distortion of the basic profile by the finite amplitude of the perturbations, give a critical Reynolds number of 2510, which agrees better with the observations of transition. In any case, the interesting point is that viscosity is destabilizing for this flow. The solution of the Orr-Sommerfeld equation for Poiseuille flow and other parallel flows with rigid boundaries, which do not have an inflection point, is complicated. In contrast to flows with inflection points, the viscosity here acts as a singular perturbation, and the eigenfunction has viscous boundary layers on the channel walls and around critical layers where U = cr. The disturbances that cause instability in these flows are called Tollmien-Schlichting waves, and their experimental detection is discussed in the next section. In his 1979 text, Yih gives a thorough discussion of the solution of the Orr-Sommerfeld equation using asymptotic expansions in the limit sequence Re → ∞, then k → 0 (but kRe ≫ 1). He follows closely the analysis of Heisenberg (1924). Yih presents Lin’s (1955) improvements on Heisenberg’s analysis with Shen’s (1954) calculations of the stability curves.

Plane Couette Flow

This is the flow confined between two parallel plates; it is driven by the motion of one of the plates parallel to itself. The basic velocity profile is linear, with U ∝ y  . Contrary to the experimentally observed fact that the flow does become turbulent at high Reynolds numbers, all linear analyses have shown that the flow is stable to small disturbances. It is now believed that the observed instability is caused by disturbances of finite magnitude.

. Contrary to the experimentally observed fact that the flow does become turbulent at high Reynolds numbers, all linear analyses have shown that the flow is stable to small disturbances. It is now believed that the observed instability is caused by disturbances of finite magnitude.

. Contrary to the experimentally observed fact that the flow does become turbulent at high Reynolds numbers, all linear analyses have shown that the flow is stable to small disturbances. It is now believed that the observed instability is caused by disturbances of finite magnitude.

. Contrary to the experimentally observed fact that the flow does become turbulent at high Reynolds numbers, all linear analyses have shown that the flow is stable to small disturbances. It is now believed that the observed instability is caused by disturbances of finite magnitude.Pipe Flow

The absence of an inflection point in the velocity profile signifies that the flow is inviscidly stable. All linear stability calculations of the viscous problem have also shown that the flow is stable to small disturbances. In contrast, most experiments show that the transition to turbulence takes place at a Reynolds number of about Re = Umaxd/ν ∼ 3000. However, careful experiments, some of them performed by Reynolds in his classic investigation of the onset of turbulence, have been able to maintain laminar flow up to Re = 50,000. Beyond this the observed flow is invariably turbulent. The observed transition has been attributed to one of the following effects: 1) It could be a finite amplitude effect; 2) the turbulence may be initiated at the entrance of the tube by boundary-layer instability (Figure 9.2); and 3) the instability could be caused by a slow rotation of the inlet flow which, when added to the Poiseuille distribution, has been shown to result in instability. This is still under investigation. New insights into the instability and transition of pipe flow were described by Eckhardt et al. (2007) by analysis via dynamical systems theory and comparison with recent very carefully crafted experiments by them and others. They characterized the turbulent state as a chaotic saddle in state space. The boundary between laminar and turbulent flow was found to be exquisitely sensitive to initial conditions. Because pipe flow is linearly stable, finite amplitude disturbances are necessary to cause transition, but as the Reynolds number increases, the amplitude of the critical disturbance diminishes. The boundary between laminar and turbulent states appears to be characterized by a pair of vortices closer to the walls that give the strongest amplification of the initial disturbance.

Boundary Layers with Pressure Gradients

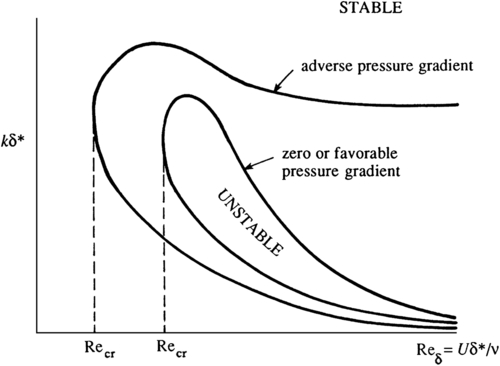

Recall from Section 9.7 that when pressure decreases in the direction of flow the pressure gradient is said to be favorable, and when pressure increases in the direction of flow the pressure gradient is said to be adverse. It was shown there that boundary layers developing in an adverse pressure gradient have a point of inflection in the velocity profile. This has a dramatic effect on stability characteristics. A schematic plot of the marginal stability curve for a boundary layer with favorable and adverse gradients of pressure is shown in Figure 11.24. The ordinate in the plot represents the longitudinal wave number, and the abscissa represents the Reynolds number based on the free-stream velocity and the displacement thickness δ ∗  of the boundary layer. The marginal stability curve divides stable and unstable regions, with the region within the loop representing instability. Because the boundary layer thickness grows along the direction of flow, Reδ increases with x, and points at various downstream distances are represented by larger values of Reδ.

of the boundary layer. The marginal stability curve divides stable and unstable regions, with the region within the loop representing instability. Because the boundary layer thickness grows along the direction of flow, Reδ increases with x, and points at various downstream distances are represented by larger values of Reδ.

of the boundary layer. The marginal stability curve divides stable and unstable regions, with the region within the loop representing instability. Because the boundary layer thickness grows along the direction of flow, Reδ increases with x, and points at various downstream distances are represented by larger values of Reδ.

of the boundary layer. The marginal stability curve divides stable and unstable regions, with the region within the loop representing instability. Because the boundary layer thickness grows along the direction of flow, Reδ increases with x, and points at various downstream distances are represented by larger values of Reδ.The following features can be noted in the figure. Boundary-layer flows are stable for low Reynolds numbers, but may become unstable as the Reynolds number increases. The effect of increasing viscosity is therefore stabilizing in this range. For boundary layers with a zero pressure gradient (Blasius flow) or a favorable pressure gradient, the instability loop shrinks to zero as Reδ → ∞. This is consistent with the fact that these flows do not have a point of inflection in the velocity profile and are therefore inviscidly stable. In contrast, for boundary layers with an adverse pressure gradient, the instability loop does not shrink to zero; the upper branch of the marginal stability curve now becomes flat with a limiting value of k∞ as Reδ→  ∞. The flow is then unstable to disturbances with wave numbers in the range 0 < k < k∞. This is consistent with the existence of a point of inflection in the velocity profile, and the results of the shear layer calculations (Figure 11.23). Note also that the critical Reynolds number is lower for flows with adverse pressure gradients.

∞. The flow is then unstable to disturbances with wave numbers in the range 0 < k < k∞. This is consistent with the existence of a point of inflection in the velocity profile, and the results of the shear layer calculations (Figure 11.23). Note also that the critical Reynolds number is lower for flows with adverse pressure gradients.

∞. The flow is then unstable to disturbances with wave numbers in the range 0 < k < k∞. This is consistent with the existence of a point of inflection in the velocity profile, and the results of the shear layer calculations (Figure 11.23). Note also that the critical Reynolds number is lower for flows with adverse pressure gradients.

∞. The flow is then unstable to disturbances with wave numbers in the range 0 < k < k∞. This is consistent with the existence of a point of inflection in the velocity profile, and the results of the shear layer calculations (Figure 11.23). Note also that the critical Reynolds number is lower for flows with adverse pressure gradients.

Figure 11.24 Sketch of marginal stability curves for a laminar boundary layers with favorable and adverse pressure gradients in terms of the displacement-thickness Reynolds number Uoδ∗/ν and the dimensionless wave number kδ∗ of the disturbance. The addition of the inflection point in the adverse-pressure gradient case increases the parametric realm of instability.

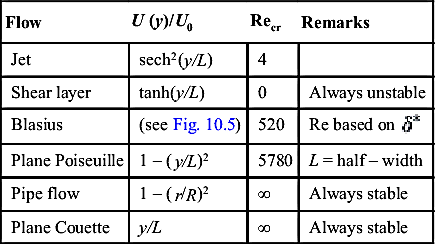

Table 11.1 summarizes the results of the linear stability analyses of some common parallel viscous flows. The first two flows in the table have points of inflection in the velocity profile and are inviscidly unstable; the viscous solution shows either a zero or a small critical Reynolds number. The remaining flows are stable in the inviscid limit. Of these, the Blasius boundary layer and the plane Poiseuille flow are unstable in the presence of viscosity, but have high critical Reynolds numbers. Although the idealized tanh profile for a shear layer, assuming straight and parallel streamlines, is immediately unstable, more recent work by Bhattacharya et al. (2006), which allowed for the basic flow to be two dimensional, has yielded a finite critical Reynolds number.

TABLE 11.1

Linear Stability Results of Common Viscous Parallel Flows

| Flow | U (y)/U0 | Recr | Remarks |

| Jet | sech2(y/L) | 4 | |

| Shear layer | tanh(y/L) | 0 | Always unstable |

| Blasius | (see Fig. 10.5) | 520 | Re based on  |

| Plane Poiseuille | 1 – (y/L)2 | 5780 | L = half – width |

| Pipe flow | 1 – (r/R)2 | ∞ | Always stable |

| Plane Couette | y/L | ∞ | Always stable |

While the results presented in the preceding paragraphs document flows where viscous effects are destabilizing, the mechanism of this destabilization has not been identified. One means of describing the destabilization mechanism relies on use of the equation for integrated kinetic energy of the disturbance:

(11.88)

(11.88)

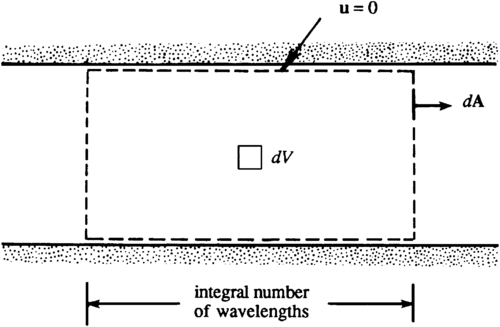

where V is a stationary volume having stream-wise control surfaces chosen to coincide with the walls where no-slip conditions are satisfied or where ui → 0, and having a length (in the stream-wise direction) that is an integer number of disturbance wavelengths (see Figure 11.25). In (11.88), Λ = ν∫(∂ui/∂xi)2dV is the total viscous dissipation rate of kinetic energy in V. This disturbance kinetic energy equation can be derived from the incompressible Navier-Stokes momentum equation for the flow (see Exercise 11.14).

For two-dimensional disturbances in a shear flow defined by U = [U(y), 0, 0], the disturbance energy equation becomes:

and has a simple interpretation. The first term is the rate of change of kinetic energy of the two-dimensional disturbance, and the second term is the rate of production of disturbance energy by the interaction of the product uv (also known as the Reynolds shear stress) and the mean shear ∂U/∂y. (The concept of Reynolds stresses is explained in Chapter 12.) The point to note here is that the value of the product uv averaged over a period is zero if the velocity components u and v are out of phase; for example, the mean value of uv is zero if u = sin(t) and v = cos(t). In inviscid parallel flows without a point of inflection in the velocity profile, the u and v components are such that the disturbance field cannot extract energy from the basic shear flow, thus resulting in stability. The presence of viscosity, however, changes the phase relationship between u and v, which causes the spatial integral of –uv(∂U/∂y) to be positive and larger than the viscous dissipation rate. This is how viscous effects can cause instability.

Figure 11.25 A control volume for deriving (11.88). Here, there is zero net flux across boundaries. This control volume can be extended to boundary-layer flow stability, when the boundary layer forms on the lower wall, by placing the upper control surface far enough from the lower wall so that the disturbance velocity ui → 0 on this control surface, even if this control surface may not abut the upper wall.