To get to the heart of how we approach cultural and artistic contact, this chapter compares the two most widely used models in Greek art history, namely, Orientalizing and Hellenization. Most Orientalizing studies concentrate on specific media—metal work, ivories, and pottery, especially—all of which might implicate Phoenician art and traders. Hellenization studies differ because they can focus on a number of different topics and subjects and are not at all restricted to Greek-Phoenician contact. Both topics have attracted a good deal of excellent scholarship in the past few decades, some of which was introduced in the previous chapter; I do not intend to duplicate here what has been done elsewhere. This chapter focuses instead on the discourses surrounding what we consider Greek art, about which we know so much relative to Phoenician art, through the kouros and the picture mosaic. I aim to comment on persistent, fundamental problems in our ways of thinking about arts produced and disseminated by contact and how they contribute to our understanding of art’s expressiveness. Accordingly, it is important to touch upon the roles played in art making by patrons and viewers as well as artists.

I believe the kouros is a straightforward, although not uncontroversial, example of external contributions to Greek art of the Archaic period. It is a useful, if atypical, case study of the Orientalizing period because of the relatively good state of preservation of both the Egyptian prototype and the kouros itself. Hellenistic picture mosaics are likewise relatively well preserved by the standards of their genre and period. The idea that they are an outgrowth of culture contact is, however, my own, so I will make the case for it below. Juxtaposition of the kouros and the picture mosaic underscores the double standards that pervade thinking about Greek art relative to other arts of the eastern Mediterranean. The goal is to explore the tendency to distinguish the Greek tradition as exceptional, sui generis despite its obvious indebtedness to other traditions. I argue that the problems of interpretation stem from the habit of presenting each of these art forms as purely Greek.

I have chosen this unintuitive pairing deliberately in order to underscore the different ways one goes about discerning the “cultural identity” of an art object. The comparison starts with the invention of each art form, what is known, surmised, or proposed about its origins; how each is studied; and what debates arise in its scholarship. From there, I explore the cultural origins of both genres, which includes some comments on the roles of artists, patrons, and contexts. Oftentimes the question of origin is not itself very compelling or even very important to understanding an art form because “the medium of exchange of culture does as much or more to explain the cultural from.”1 But I will show that origins are important in each of these cases to consider—and to correct—our impression of what these art forms are trying to express in social terms. Finally, the double standard apparent in these different contact scenarios will be considered in its own right. I argue that these apparent extremes of art, one original and geographically particular, the other pluralistic and diffuse, cannot be understood as discrete cultural products, which raises again the question of culture’s relationship with art. At this point, Phoenicia is brought into the discussion through the invention of its monumental sculpture. The anthropoid sarcophagus is a type caught in an awkward space between Egyptian and Greek art. It allows us to think through different ways of characterizing arts produced by contact, especially the roles of artist and patron in the varied reactions to elite Egyptian funerary art.

The kouros is a well-known type of approximately life-sized or larger, sometimes colossal, Greek Archaic sculpture invented in the second half of the seventh century and produced until around 500. Most of the preserved votive dedications (agalmata and anathēmata) or tomb markers (sēmata or mnēmata) were made in marble; small-scale versions were often in bronze, terracotta, or gypsum. The ancient name of the statue type is not known. The word “kouros,” from the Greek term for “boy,” began being used in the late nineteenth century. The name became synonymous with the type only in 1942, however, when Gisela Richter entitled her influential study Kouroi.2 How and where the kouros type was invented is debated, as is the extent of its dependence on Egyptian or Near Eastern models. The earliest extant kouroi seem to have been made in the Cyclades, on Naxos.3 These are found in sanctuaries in Boiotia and Delos and in both sanctuary and funerary contexts in Thera and Samos.4 Some areas, such as Attika, develop the type later on, from circa 600. In situ, the kouros operated within the visually charged religious context of the sanctuary or the cemetery.5 Kouroi pleased the gods while pointing to their donors or the deceased, functioning simultaneously as agalmata and mnēmata, that is, as “delights” and “memorials.”

The most widely influential narrative about ancient art and the kouros comes from the Viennese-born art historian Ernst Gombrich (1909–2001). In his 1950 Story of Art and 1959 Art and Illusion, Gombrich drew inspiration from Richter’s 1942 monograph to show how the kouros embodied the priorities of the Western art historical tradition. He admired the kouros’s will to progress toward ever-increasing naturalism that would allow, eventually, the Greek sculptor to surpass his Egyptian teacher. To Gombrich, a key characteristic of the kouros was that it evolved in terms of its anatomic realism, an idea that fits well with modern Western ideals of cultural and artistic progress. This virtuous evolution was rooted firmly in empiricism and mimesis in the sense of emulating the natural world. And so, while Egyptians produced art analytically, in order to repeatedly express knowledge of an ancient formula, Greeks produced art through vision, experience, and a willingness to push boundaries, moving from Egyptian schēmata to something superior. This model of Greek art was both moral and highly political. As befits the post–World War II context in which his ideas emerged, Gombrich presents the invention of democracy in Athens as a part of the classical artistic revolution.6 Hence a brief moment of inspiration from Egyptian art led to experimentation and the “Greek revolution” that gave birth to the enduring Classical period, the acme of Greek art. Gombrich’s reading is passionate, its idealistic and historical flaws as obvious as its impact was long-lasting.7 Gombrich’s work demonstrates that the interpretation of the kouros says a lot about the conception of Greek art and its fundamental place in the canon of Western art. The “ideological stakes” of the kouros are high.8

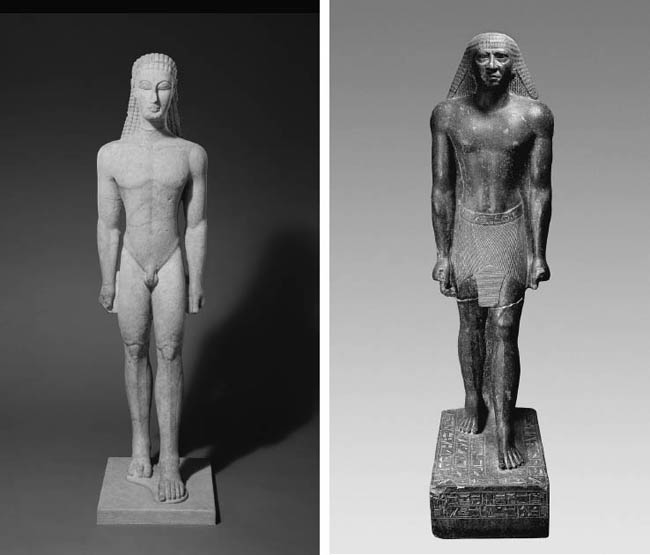

The decision to focus on the kouros, rather than the more complex history of female stone statuary, is telling.9 Unlike its female counterparts in stone, the kouros has remarkably consistent formal features over its wide distribution. Its resemblance to striding Egyptian male statuary is striking (Figure 7): both figures stand frontally, a position that emphasizes their broad shoulders and narrow waists; both have elaborate hair or wigs, usually long; both stand with arms at their sides and clenched fists; both deliberately ignore their viewers; and both, despite having their left legs forward in a striding pose, are flat-footed and “fundamentally immobile”—that is, they are represented in a kind of energetic stasis.10 Much has been made of the kouros’s nudity or near nudity. As many have pointed out, the formal similarity between the kouros and its Egyptian model helps to highlight this choice made by Greeks. There is no evidence of artists working out different ideas about the type. The kouros emerges fully formed. Thus concludes Rainer Mack: “The invention of the kouros [was located] within a material process of setting-off or distinguishing, that is within a practice of differentiation.”11 This is an important claim that requires further consideration below.

Figure 7. Left: kouros from Attika? early 6th c. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art 32.11.1. Marble. Ht. 1.94 m. Photo: Art Resource, N.Y. Right: statue of Mentuemhet from Karnak, ca. 650. Cairo, Egyptian Museum. Granite. Ht. 1.34 m. Photo: Jürgen Liepe.

First, let us look squarely at our evidence of the kouros. Nearly four hundred examples of the kouros type survive (compared to the approximately 250 surviving korai). This is truly an extraordinary number given what we believe are typical survival rates of other ancient Greek artworks, hovering at or below 1 percent of ancient production.12 Should a rate of even 5 percent preservation hold for the kouros, it is possible that tens of thousands of kouroi once existed. Given that around fifty are known from Attika, several thousand might have once stood in just that area. In a recent study, Nora Brüggemann has shown that, of those kouroi with known provenance, around 70 percent (n = ca. 270) were votive dedications, 13 percent (n = 50) were grave markers, and 17 percent (n = 65) were found abandoned in Cycladic quarries.13 Over the lifespan of the type, its main findspots were Attika (as usual), Boiotia, the Cyclades, and Ionia. In a funerary context, the kouros is found almost exclusively in Attika, the Cyclades, and Ionia. Attika is unusual, as a matter of fact, for having more funerary kouroi than votive ones (by contrast, fifty korai have been found on the Athenian acropolis).14 The largest concentration of votive kouroi by far is in the sanctuary of Apollo at the Ptoion in Boiotia, which counts some 120 examples.15 Although the kouros type is known in North Africa and Italy, it is clear that the Greeks’ neighbors were almost totally uninterested in it.16

Thus another advantage of studying the kouros type is that it is found almost exclusively in areas where we believe Greek speakers lived, and neither its distribution nor its manufacture is concentrated in only one or two sites. It is important to point out, however, that there are not many examples from western, central, and northern Greece or the Peloponnese and a number of islands, including Crete (and in this context we must remember that the sphyrelaton or “hammered bronze” male figure from Dreros of circa 700 did not foreshadow Cretan interest in the monumental stone kouros).17 In other words, the type is mostly Aegean in a narrow sense—Athenian, Boiotian, Cycladic, and Ionian—and not much at all a part of the life of Doric Greeks.18 More than 80 percent of votive kouroi with inscriptions are dedicated to Apollo. Understandably, scholars were initially inclined to view them as representations of Apollo as well, even though the type was dedicated to several gods, both male and female. Yet in vase painting from the seventh-century Cyclades, home to the earliest known kouroi, Apollo was shown bearded and fully clothed.19 For this and other reasons many now believe that kouroi show ideal male youths, aged probably in their late teens.20

A few characteristics of the kouros seem to encourage identification with the statues by onlookers. The form seems to be somatically indistinct.21 The kouros smiles to signal its elite status, shining (aglaos) and happy, just as aristocrats could refer to themselves as geleontes, the “smiling ones.” The smile further indicates the statue’s magical life force, an expression of the kind of vitality that Greeks admired in Egyptian art and had valued already in their own artistic production since the Daidalic period.22 Tanner has argued that sanctuary kouroi represented the deity whom they were meant to delight as agalmata.23 Slippage between the divine and the statue was not only allowed but expected, even though care seems to have been taken not to upstage Apollo.24 Kouroi sometimes received offerings, further strengthening connections to the gods.25 In the sanctuary and in the funerary setting—the latter deliberately invoking the former with its statuary, naiskoi, and offerings—the kouros reinforced the proximity of elite and god. Representing the youthful form in dynamic stasis, outside human time,26 heightened its special status.

The social function of the kouros was to thematize a specific kind of ideal sameness, what later Greeks called kalokagathia, meaning “beautiful and good.” The ideal of kalokagathia guarantees the endless youth of Olympians and heroes such as Theseus. It is also what causes Memnon, despite his Ethiopian origins, to be somatically indistinguishable from Greek-born heroes. Like these divine and heroic figures, the kouros remains forever in its akmē, its “jeweled springtime,” beautiful, isotheos (“godlike”), and sexually appealing.27 At the same time, this ideal underscored the critical social differences between the favored realm of the aristocracy and the other members of the demos.

Comparison of the New York kouros from Richter’s early Sounion Group (Figure 7, left) to kouroi from her “modeled” Tenea-Volomandra Group and “graceful” Melos Group shows how much styles of kouroi are varied by region.28 At the same time, the pose and schema of kouroi are remarkably consistent. In Egypt sculpture was made in more-or-less centralized royal workshops and from there was distributed and emulated by Egyptian elites. There was certainly no equivalent system in the Aegean. Yet the pose and schematic attention to certain passages of the sculpted body approach the visual stability of the Egyptian striding male figure from which the kouros borrows, counteracting the clichés of originality that have been used to separate Greek sculpture from Egyptian. If it is correct to think that attribute-free kouroi are heroic youths that can but do not necessarily represent any youth in particular—the kouros as Youth—here is a key difference from the Egyptian prototype, which was used to represent individuals. In this reading, the kouros’s lack of humanism and individuality might be the biggest conceptual contrast.29 I suspect, however, that the anonymity of the kouros has been exaggerated in modern scholarship. Egyptian statuary reminds us how art that appears formulaic should not be confused with the generic. If we understand Mentuemhet as a portrait (Figure 7, right), surely the New York kouros and other funerary kouroi should be portraits (eikones) as well, even if they do not seem like true likenesses to modern eyes.

Further, although the problem has been recognized for a long time, poor preservation of paint and perhaps other added features are creating a false impression that the kouros lacked specificity. Colorful jewelry and hair ornamentations would have enhanced the statue’s poikilia (“adornment,” “variegatedness”)30 and masculine charis (“beauty”),31 thus increasing its particularity. The kouros excavated with Phrasikleia once had a painted necklace and pubic hair. The New York kouros and the Dipylon head—thought to be by the same sculptor—have sculpted necklaces. The Sounion kouros of circa 590 had a painted tainia (long head band). The colossus dedicated by Isches in circa 580 was painted all over in reddish-brown ochre; paint was found also on the hair, eyes, lips, nipples, and pubic area. That statue might also have had a painted moustache or even a beard, traces of which are found on other kouroi (see Plate 2).32 These particular features have contributed to the idea that certain kouroi represent heroes.33 Ian Jenkins even suggests clothing might have been painted on to some kouroi. This is possible, but kouroi that preserve carved genitals indicate that at least that part of the body was exposed.34 Bearing these examples in mind, it is possible to imagine that other, or perhaps many, kouroi had distinguishing features that further challenge the idea that the type was meant to show undistinguished, teenaged Youth.

Since the discovery of the Thera kouros in the 1830s, the connection between the kouros and Egyptian statuary has been noted; by the early twentieth century, it had become a regular part of the scholarly discourse.35 Egyptian sculpture was known to Greeks long before the first kouros was made, however, which suggests that a specific, perhaps new, cause should be sought. Brunilde Ridgway claims that a new way of representing Apollo resulted from new thinking about him: “Perhaps the aftermath of the colonization movement, and a renewed wave of influence from the Orient, stressed a new conception of the god as a figure of action.”36 A similar claim has been made regarding dedications at the Samian Heraion and the learning of the lost-wax technique from Egyptians.37 It does seem that Greeks had a new interest in monumentality, as the kouros type appears near the beginning of monumental stone sculpture; interest in work of this scale might be connected to ideas about divinity, if not always to Apollo himself.38

For more than thirty years, scholarly consensus has held that the kouros was not only modeled after Egyptian statues but also sometimes employed their proportional system. Eleanor Guralnick, in an important series of articles based on her doctoral dissertation, argued that some kouroi were made throughout the sixth century using the so-called Egyptian second canon of proportions.39 If Guralnick’s thesis were correct, one would have thought that the possibility the kouros was a type developed first in Egypt or by Egyptian craftsman would have been taken seriously, but it was not. Instead, the kouros was and is presented as a product of “influence” or “inspiration.”40 The recent statistical analysis of the kouros by Jane Carter and Laura Steinberg argues that an overall ideal proportional approach does exist in preserved kouroi, and the kouros ideal is, indeed, similar to the ideal Egyptian approach. Yet these authors have proved that, contra Guralnick, kouroi do not reveal particular fidelity to an Egyptian proportional system (one that is, according to Egyptologists, not especially consistent).41 They can be more accurately divided according to regional styles (Carter and Steinberg’s Naxian/Attic and Parian/Attic groups) with independent chronological development.42

Nevertheless, there are other reasons some scholars favor the idea of Egyptian artistic “influence” over more direct artistic interaction. Recalling the emphasis on difference mentioned earlier, to us the kouroi look Greek, not Egyptian. First there is the nudity. Then there is the removal of stone from between the arms and torso and between the legs. There is also the appearance of the sources of inspiration, late Twenty-fifth Dynasty (Kushite) sculpture and Saïte sculpture, which was alternately more naturalistic or cartoonishly exaggerated in comparison to kouroi.43 In other words, despite its clear reliance on an Egyptian model, it is possible to understand the kouros as a Greek invention expressing the Archaic style (as Ridgway suggested), thereby stressing the originality of Greek artists from the very beginning of Greek monumental sculpture. Echoing Gombrich, Boardman explains the process thus: Greek artists “chose carefully, never merely copied”; what they chose, he claims, they turned into something “wholly Greek.”44

The invention of the picture mosaic seems like a complete inversion of the invention of the kouros. The earliest and finest tessellated mosaics, especially those picture mosaics produced in the technique we refer to as opus vermiculatum, are not concentrated in one part of the Mediterranean. The picture mosaic in particular, as a creation of the Hellenistic period, is to a significant extent detached from the Greek “mainland.”45 The ideological stakes of the mosaic would appear to be rather low compared to the kouros, although, as we will see, that does not necessarily follow. Because it lacks a clear nucleus of development, several competing ideas have arisen regarding mosaic’s invention.46 Much of the difficulty surrounding the question of mosaic’s origins stems from a familiar set of problems: limited preservation, a reluctance to excavate below floors (or otherwise damage them with scientific testing), and modern mishandling. Altogether these challenges encourage the dating of mosaics according to a theory of style that is difficult to corroborate.

Contra Pliny’s Historia naturalis 36.184, Greeks were not the first people to make paved, decorated floors, and no site, Greek or otherwise, has evidence of the transition from pebble, chip, and other early pavements to tessellation and thence to opus vermiculatum picture mosaics.47 Two main theories about the development of tessellation have been proposed. Echoing the origin theories of the symposion, one argument puts forward an eastern Mediterranean origin, and another favors the West.48 Neither is totally convincing at this stage. Tessellation does appear early at the site of Morgantina in Sicily. The Ganymede mosaic from the eponymous house at Morgantina is dated to the third century on firm evidence, making it one of the earliest examples of fully realized tessellation (Figure 8).49 The floor uses tesserae and some larger pieces of cut stone to create an energetic composition showing the boy’s abduction by Zeus. Ganymede’s expression is vivid, his body well modeled and foreshortened, showing mosaic’s illusionistic potential.

Figure 8. Mosaic from the House of Ganymede, Morgantina (Sicily), 3rd c. Various materials. 10.5 × 13.0 m. After Phillips 1960, fig. 4. Photo: courtesy of the Princeton Expedition to Morgantina.

Of course some pebble mosaics are highly illusionistic, too. Pella provides good examples, including Gnosis’s stag hunt, from probably the last quarter of the fourth century (Figure 9). As Katherine Dunbabin has noted, the approach to modeling at Pella can be compared favorably to the tessellated Ganymede mosaic despite the difference in technique.50 An anecdote about Hieron II, the tyrant of Syracuse, is sometimes taken as confirmation of mosaic’s early development in Sicily (Moschion ap. Ath. 5.206d–209e). According to the tale, Hieron presented the galley ship Syracusia to Ptolemy III Euergetes as famine relief after the failure of the Nile flood. The Syracusia was large, luxurious, and decorated with mosaic panels (abakiskoi) showing stories from the Iliad.51 If we understand that these panels were constructed in Syracuse, the passage offers further support that tessellation was developed in Sicily by the middle of the third century.52 The story is also noteworthy in that it presents mosaic as a valuable object in elite gift-exchange.53

Figure 9. Mosaic from Pella house I.5 signed by Gnosis, probably last quarter of the 4th c. Pella, Archaeological Museum. Pebbles, lead. 3.24 × 3.17 m. Photo: Frank and Helen Schreider/National Geographic/Getty Images.

Although they lack firmly dated early tessellated mosaics, the eastern royal courts were also significant sites of mosaic development and patronage.54 Pliny (HN 36.184) suggests that Pergamon was admired for its mosaics, and its most famous practitioner, Sosos—the only mosaicist mentioned in Pliny’s history (36.184–89)—made two generic mosaics there showing drinking doves and a floor dirtied by feasting (the asarōtos oikos), versions of which are known at Delos, Pompeii, Hadrian’s Tivoli villa, and elsewhere.55 Egypt’s importance in at least the dissemination of mosaics and subjects is suggested by papyrological evidence and attested by the lasting popularity of Nilotic themes, especially in mosaics from the Bay of Naples region.56 The well-known business contract, the Zenon papyrus 59665 (256–46 BCE), provides the sole extant example of how Hellenistic decorative floors were arranged. The contract describes in detail the plan of mosaics in two baths, one for each sex, for a villa in Egyptian Philadelphia. The paradeigma (“model”) for the men’s floor comes from a royal workshop,57 proving that the influence of royal workshops extended beyond the palatial centers to locations lacking resident craftsmen, in this case, from the tip of the Nile Delta into the Fayyum.

Egypt is also where evidence of mosaic’s potential to rival monumental painting is found for the first time. The mosaic said to be from Tell Timai (Thmuis) signed by Sōphilos is generally considered to be the earliest extant opus vermiculatum; it is dated to circa 200–150 (see Plate 3).58 At the center of the mosaic is a vivid female figure in red tunic and silver cuirass holding a ship’s flagstaff (stylis) and wearing an elaborate headdress in the form of a warship. A golden anchor fibula secures her chlamys. She is identified sometimes as a personification of Alexandria and sometimes as Ptolemaic Queen Berenike II (r. 246–221), though neither interpretation is certain.59 The overall impression of bust and headdress is of vibrant intensity. The signature “Sōphilos epoiei” appears at the upper left of the central field. The subject is rendered as though viewed at eye level, and it is thought that this mosaic and a second version (also said to come from Thmuis) are copies of the same painting.60 Here, and in other Hellenistic mosaics from the delta region—the mixed technique Shatby stag hunt or the vermiculatum wrestlers and “guilty dog” from the palaces area in Alexandria—we have precious evidence of technical virtuosity and a clear interest in illusionism.61 The urge to associate these works with lost Greek paintings is understandable. But neither Greek iconography nor a precedent in Greek painting was required to create illusionistic mosaics, as attested by the popularity of black and white floors, hunting and Nilotic scenes, and the famous asarōtos oikos of Sosos most of all.62 In fact, explicitly mythological or political scenes are relatively rare in Hellenistic mosaics, whereas theatrical, landscape, and generic scenes were very popular.63

In the interpretation of the picture mosaic, one notes a willingness to sever context and patronage from the cultural identity of a work of art and to associate technical virtuosity with a Greek style. The evidence points to a more complex history. The preceding discussion of tessellation’s early emergence in Sicily underscores the extent to which the marginalization of the western Mediterranean in histories of Greek art might be limiting our understanding of mosaic’s origins. We know that Italian artists were very important to the development of mosaic, especially black and white illusionistic floors.64 If the development of illusionistic pebble mosaics, tessellation, and opus vermiculatum occurred in several Mediterranean contexts in the fourth to second centuries, the extent to which all such floors should be collapsed into a single category of “Greek art” must be reconsidered. One can ignore patron and context in favor of iconography or argue that Greek craftsmen or members of the Macedonian court helped spread the demand for decorated floors to places like Pergamon and Alexandria, but the point remains that vermiculatum was achieved in Egypt only once Greeks, Macedonians, and various non-Greek-speaking people came into contact. Tessellated mosaics, we should note, have not been found in the Antigonid capital.

Further, in the few vermiculatum floors preserved in the delta, we find subjects ranging from the apparently Hellenic (wrestlers) to the universal (portraits, a dog). According to the available, though certainly imperfect, evidence of experimentation in multiple third-century locations, it is not clear that vermiculatum would have occurred without these contacts. Certainly we should avoid thinking that the popularity of mosaics in Egypt or Italy is a sign of Hellenization. There is no evidence of tessellated mosaics moving out from an imaginary core in the Balkan Peninsula to equally imaginary cultural peripheries.65 Instead, the appearance of picture mosaics in domestic contexts in Pompeii, in baths in the Egyptian Fayyum, and in houses in the mixed milieu of Hellenistic Delos underscores the idea that culture contact was essential to the genre’s development.

I believe that the origins of the kouros and the development and spread of the picture mosaic must be understood fundamentally as responses to the movement of people and ideas. The juxtaposition of these two genres exposes contradiction in the evaluation of arts of contact, first, in the uneven importance placed on origins of motives and techniques versus findspots of objects. Traditional interpretations of the kouros encourage the conclusion that sites of manufacture and display are most important when it comes to understanding an art form’s cultural identity or intended social function. Traditional views of the picture mosaic argue just the opposite, making the unconvincing claim that the site of manufacture and display are less important than the origins and style of motifs.

In order to do more than simply point to connectivity, we must now take a closer look at the way these objects functioned in context, putting aside for the time being Burkert’s warning that an object that points to “interconnections” cannot be parsed.66 While dedicatory inscriptions on kouroi or kouros bases are common, very few retain what might be artist signatures.67 One of the bases of the Delphic “Kleobis and Biton” (possibly the Dioskouroi) preserves a partial signature of [Poly]medes of Argos.68 Despite the paucity of signatures, which are in themselves no guarantee of artistic identity, the Greek identity of the artists and patrons of all kouroi is taken for granted. Indeed, the kouros is understood as an expression of Greek culture, leading Guralnick in 1978 to ask what, when looking at Figure 7, would seem an extraordinary question: “One persistent question, since the visual evidence has been subject to conflicting interpretations, is whether there is Egyptian influence on early Greek sculpture. There is at present no generally accepted theory of what would constitute such an influence, nor any objective proof of it. Thus some scholars have concluded that similarities are accidental or coincidental and common to the arts of primitive societies.”69 Others, Guralnick adds, see the Egyptian connection and believe that it testifies to the “observation of prototypes and the learning of techniques in established schools . . . of stone carving.”70 Thus the kouros is presented as a product of mimesis, in the sense of observation and imitation, and of education. Even this more plausible scenario reveals how our understanding of the invention of monumental sculpture by Greeks is framed by modern ideologies.

Following Ian Morris, we can characterize the kouros as an example of deliberately eastward-looking behavior, art created for internal conversation and elite competition.71 Given pervasive, though now seriously challenged, ideas about the symposion as an emulation of eastern luxury, and given the clear evidence that even Classical-era Athenians emulated their sworn enemy Persia in a number of ways, it seems curious to me how little notice is given to the idea that the impetus for the kouros was emulation of Egypt and elite Egyptians, one that made a profound, lasting, and structural change to Greek art.72 Only a few art historians, notably Rhys Carpenter, have been open and supportive of the idea of emulation. Compare the views of another classical art historian, Robert Cook, who was able to insist seriously that no Greek sculptor had even seen an Egyptian statue and that any similarities, if they existed, “might have been transmitted by hearsay.”73 It comes perhaps as little surprise that, rather than supposing a direct connection with Egypt, some scholars posit a Levantine connection (that better fits pervasive ideas about the Orientalizing period’s Syro-Levantine connections) supported in part by the style and iconography of the problematic carved ivories.74 But the claim that the similarity of the kouros to Egyptian statuary is coincidental stretches credibility to the breaking point.

No one is suggesting, however, that the kouros and its Egyptian prototype are indistinguishable—they are different stylistically from the start—or that all of the characteristics of kouroi over time resulted from a single episode of contact in the mid-seventh century.75 While it is of course impossible to prove exactly how the kouros came about, there is much better evidence of cultural and historical events that coincide with its invention than one will find for most ancient art. There already was awareness and admiration of Egypt and Egyptian art as indicated by earlier imports, anecdotes about Daidalos training in Egypt, and Greek art itself.76 Emulation of the Egyptian wig begins circa 700, as seen, for example, on subgeo-metric terracottas at Argos and Sparta,77 proving that Greek art had an established practice of selective emulation of Egyptian art prior to the Archaic period and the invention of the kouros.

The kouros’s invention likely arose following military, settlement, and trading activity in Egypt, rather than through imitation of imports or imports alone. In the seventh century, Psamtik (Psammetikhos, r. 664–610) hired Ionian and Karian mercenaries to help him reconquer and reunify Egypt, expel Assyria in the process, and usher in a brief period of Egyptian political domination. Some of these mercenaries were garrisoned in camps such as Tahpanes (Daphnae) in the northeast delta.78 Despite Cook’s suggestion to the contrary, we know that mercenaries saw Egyptian statues on campaign. Grave stelai inscribed in Greek and Karian have been excavated at Saqqara, and in the sixth century a few soldiers even inscribed their names on the legs of statues of the thirteenth-century pharaoh Ramses II (Ozymandias in Greek) at Abu Simbel, some seven hundred miles up the Nile.79 A handful of soldiers left polis ethnics naming Teos, Kolophon, and Rhodes. Psamtik also opened Egypt to Greek merchants.80 In the mid to late seventh century, Greeks established what would become a polis or emporion (Greek sources call it both) at Naukratis in the western delta.81 When Herodotos later visited the Temple of Neith (“Athena”) at Saïs (2.28), he was only twenty-five kilometers from Naukratis. It is impossible to deny that these experiences were hugely influential to Greek art and architecture, even while acknowledging that some techniques were likely learned from migrant Egyptian artisans. Exposure to Egyptian art in situ seems to have led directly to the rise of monumental and colossal stone architecture and stone sculpture, as was put forth freely by Greeks.82

The debated part of this prehistory of the kouros concerns how much Egyptian technology matters versus Greek originality, and how excess attention to the latter has shaped art history.83 Bearing in mind that the Egyptian precedent is clear, what makes scholars so certain that only Greeks produced kouroi? In truth, thanks to the circulation of skilled workers in the Mediterranean, it is much harder to know the particular cultural or ethnic identity of artists than some admit.84 We cannot really ever know about the identity of most artists, though it is possible to point out that the preserved signatures on kouroi, as well as the preserved dedicatory inscriptions, are written in Greek. Gypsum kouroi found at Naukratis (and elsewhere) offer different evidence. They bear a striking resemblance to Cypriot statuary, and it seems that Cypriot-trained sculptors made them.85 Although male nudity was not a common feature of Cypriot art, these nude statuettes show how Cypriot artists tailored their work for Hellenic patrons. It follows that Egyptian sculptors could have made kouroi, too, although one might expect that these would look more like Egyptian statues—in stylistic and technical terms, in the treatment of facial features, the overall approach to the body, the removal of stone, or the distribution of weight.86 Regardless, we must not take for granted that only Greek artists could produce the kouros. Bearing in mind the conventions of Archaic art for aristocrats, the expression of kalokagathia, we should not assume that all the kouroi represent Hellenes, either.87

Our evidence suggests that patronage was the most important factor in determining the formal features of the kouros, whereas artists had a significant amount of input into its style. But we have still not answered the question of why the type was invented in the first place. Does the kouros exist to represent a Greek identity in opposition to an Egyptian one? Does this priority explain its particular features, its nudity and its tendency toward naturalism? As Andrew Stewart and others have pointed out, one curiosity about nudity in Greek art is that, with the exception of the Knidia, our source material does not comment on it.88 Male and female nakedness is shown in some Egyptian art, too. It is generally perceived by Hellenists as a rare phenomenon, however, especially among the elite adult male statuary that kouroi were emulating. And so, the thinking goes, nudity emphasizes the conscious distinction of Hellenes through the body of the kouros.89

Greek art had already established a convention of male nudity before the emergence of the kouros. While nudity of both sexes is a feature of some late Geometric art (e.g., on the Dipylon krater of ca. 750), from the late eighth century women are typically clothed, while nudity becomes popular, if not a “default setting,” for males.90 What these examples show is that a major function of clothing or nakedness in Archaic art was to mark gender, that is, to mark difference between the sexes, not difference between Greeks and non-Greeks. Several contend that the nudity of the kouros is more than an artistic practice, however, thinking that it stems from a particular Greek interest in the anatomy and proportions of the human body. Richter, Gombrich, Boardman, and others date kouroi according to their increasing success at imitation of the eidos (“form”) of the body. Such thinking fits with the idea that nudity can be tied also to the Greek interest in improving the body through athletics and training without clothing. Both ideas are flawed. First, nudity in art cannot be only an imitation of social practice, because it is employed in artistic contexts where it never was in life.91 Second, nudity in art predates widespread nudity in athletics according to several ancient sources, which place its advent at the Olympics in 720.92

Further, Robin Osborne, following On Ancient Medicine 4.2 and other sources, has recently argued that the goal of athletics was not to train the body to make it more beautiful but to make it stronger. Beauty, Greeks believed, was the cause of athletic achievement, not its result.93 Greeks were hardly interested at all in the development of muscles themselves, Osborne has shown, but instead focused attention on the joints and hard or soft flesh.94 Thus the attention paid in sculpture to the cuirass-like abdomen, to the knees, and to the scapulae stemmed not from naturalistic concerns but rather from a particular ideology of the body. For example, Simmonides (fr. 542 PMG) wrote in the late seventh to early sixth century: “It is difficult for a man to become truly noble (agathos), foursquare (tetragōnon) in hands, feet, and mind, crafted without flaw.”95 We can infer that the “conventional irrealism”96 of the kouros’s body was as intentional as the emphases on its schema and bronze hardness.97 The kouros deliberately evokes visual properties very similar to those of bronze armor, both the cuirass and the greave.98

Even within the development of different regional types, this ideology of the body was highly valued, probably more valued than anatomical realism. One notes even in the most naturalistic kouros, Aristodikos, that mimesis was not the chief motivation for its formal properties. The goal of kouroi, then, was to look like other kouroi. It follows that their naturalism must be understood in relation to other kouroi, not to the real.99 As the “signifying relations among kouroi are fully ‘horizontal’” and “non-hierarchical,”100 Mack accordingly presents the kouros not as a generic entity but as a kind of simulacrum that was always part of a social network, one that embraced community while striving for personal differentiation. Seen this way, the somatic naturalism of some kouroi represents a choice, not an evolutionary achievement. I would take Mack’s reading a step further to argue that, like most social entities, the kouros’s impetus and evolution was almost entirely internal even though it never could have emerged without contact. Its nudity was symbolic, a marker of gender and the kind of beauty that was divinely given, not earned through training.101

So, although the nudity of the kouros represents a conscious choice not found in its prototype, I think it is a mistake to interpret that choice as motivated by a desire to articulate cultural difference—that is, to sculpt Hellenism in opposition to Egyptianism (if the idea of Hellenism even existed ca. 650). I would claim just the opposite of that now well-established view. The various structuralist approaches to the kouros misinterpret its symbolic nakedness by emphasizing the “removal” of the Egyptian kilt over the nearly identical use of the male body. Egyptian elite art was modest about male genitalia but not about the rest of the male body, which it used, nearly fully exposed, to promote vigor, virility, and divinity. One clear aim of the kouros was to retain the pose of its model, which suggests that the importance of Egyptian elite art—the particulars of which most Greeks were at least vaguely aware (Diod. Sic. 1.98.9)—continued to matter long after the Greek tradition was well established. In retaining this pose for the exposed male body, the kouros evoked precisely the same qualities as its Egyptian predecessors, albeit within the conventions of Greek art in which male genitalia played an important role, and the kilt none.102

Some have speculated in practical terms about the type’s invention. Greek artists might have apprenticed in Egyptian workshops, for example, an idea that comes from the assumption that artists could not simply “improvise” monumental stone sculpture, “nor [could stone sculpture] spring spontaneously expert from instinctive talent and innate skillfulness.”103 Carpenter concludes that the first kouroi sculptors must have been from poleis with traders in the delta, probably Ionians from Miletos, Samos, and maybe Chios.104 Jeffrey Hurwit suggests more than one origin and draws the reasonable conclusion that the inspiration for monumental stone work came from observation of, especially, New Kingdom kolossi in Egypt.105

In specific terms I think it likely that the first kouroi were made by craftsmen who had visited Egypt itself, not as Greek artists seeking an education (although that did, apparently, happen) but as bronze workers who traveled with the troops.106 The relationship between bronze body armor—the cuirass and the greaves—and the schematic representation of bone and musculature in kouroi encourages this idea, from the single line of the pectoral ridge to the attention paid to the anatomy of the knee. In both we see the play between naturalism and artifice, the general and the particular, all of which was meant to glorify the divinely wrought masculine body.107 It is possible the earliest kouroi were made in Egypt itself, but we lack evidence. Certainly the eastern Aegean islands, most of all Samos, were important sites for regular interchange with Egypt and developed art that looked toward Egypt even while the Cyclades supplied at least the raw material for the earliest kouroi.108 (The colossus in the Heraion dedicated by Isches is notably Egyptian looking.) Whatever its means, the transfer of technology and ideology from Egypt to the Aegean in both bronze and stone had a profound effect.

Early monumental female stone statues such as the Cretan “Lady of Auxerre” of circa 650–625 and the contemporary “Nikandre” from Delos illustrate key differences in the development of female statuary.109 Both works share a number of formal properties we associate with Orientalizing stone statuary, including the so-called Daidalic flatness and a triangular wig or wig-like treatment of the hair. As with much of what we call Orientalizing, the borrowing of these features and the technical skill to execute them is clear, even if the precise source material and means of transmission are disputed. Proximity of these works to Assyrian art is explicit.110 Nikandre, standing at 1.75 meters (to the Lady of Auxerre’s 0.65 meters), marks the beginning of life-sized and over life-sized korai and thus marks the transition from the Daidalic to the Archaic style. While early male figures such as the 0.8 meter sphyrelaton of Dreros of circa 700 could have taken a similar path, they did not. The Dreros male shares some qualities with the kouros, notably the schematized pectoral ridge, but not its wig, pose, or scale. Unlike the kore, and contra Cook, the stone kouros did not evolve out of even later Daidalic art. We can conclude that although monumental stone sculpture would still have been a part of Greek art without direct contact with Egypt, the kouros type as such would not exist without its Egyptian prototype. This conclusion should encourage us to reject once and for all Gombrich’s obviously overblown and ahistorical narrative of the kouros as transcendent.

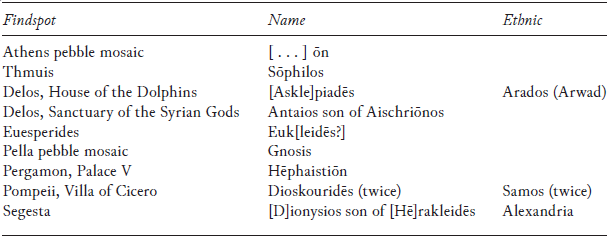

Retuning now to picture mosaics, we see another approach to the significance of origins. Mosaics made in situ in various Mediterranean locations imply the movement of skilled artists. Scholars regularly claim these artists were Greek. For example, in relation to the Egyptian tholoi designs described in the Zenon papyrus, Wiktor Daszewski wrote: “It is perhaps the enterprising sprit of the first generation of Greeks in a new country . . . that stimulates small experiments, improvements and adjustments of the older Greek prototypes and techniques to the realities and requirements of the new environment. . . . Most likely the mosaicist was of Greek origin.”111 This romantic reconstruction of events recalls claims about the independence of the kouros from Egyptian prototypes. It can be compared to this statement about tessellated mosaics in Hellenistic Italy: “We may safely assume either the actual presence of Greek craftsmen . . . or the importation of works ready-made from the Greek East.”112 And to this one regarding the Alexander Mosaic: “The mosaic was laid on the spot by a team of craftsmen, who may safely be taken to have been Greek.”113 There is some evidence about the identity of mosaicists that complicates this picture. Eight pre-imperial mosaics are inscribed with what seem to be artist signatures (Table 1). Here again all the signatures are written in Greek. Yet the accompanying ethnics and findspots suggest that mosaic was an art form that transcended the Greek cultural identity it has been ascribed.

A few comments can be made about the corpus. The signatures come from disparate areas, from Segesta, the Elyminian capital in northwest Sicily, to Pergamon, demonstrating that the practice was widespread and not at all common. Two are found on pebble mosaics in Athens and Pella (see Figure 9). The rest are tessellated, such as Plate 4. Fewer than half of the signatures include ethnics that identify individuals from Phoenician Arwad, Samos, and a place called Alexandria (we cannot be sure which one).114 These signatures were found on mosaics from Delos, Pompeii, and Elyminian Segesta, meaning that findspots and ethnics never match.115

Table 1. Pre-imperial Mosaics with Possible Signatures

Figure 10. Plan of the House of the Dolphins, Delos. Photo: courtesy École française d’Athènes.

Asklepiadēs of Arwad merits further consideration. In circa 100, he signed the mosaic in the House of the Dolphins on Delos (see Plates 4 and 5).116 Delos is the most important site for our understanding of Hellenistic picture mosaics.117 More than 350 have been found there in domestic contexts that postdate the island becoming a free port in 166. As I discuss in more detail in Chapter 5, Delos is known as a site of intense engagement of people from different parts of the Mediterranean. The house’s plan, with a vestibule leading to a Doric peristyle, is an Italian arrangement popular there.118 Its main entrance contains a tessellated image of the so-called sign of Tanit (Figure 10, room “A,” and Figure 11).119 The motif is characterized by a circle interpreted as a “head,” a cross-bar interpreted as “arms,” and a triangular “body” (a schematized dress). The origins of the form are not clear. Many possibilities have been proposed, ranging from the ankh to an anchor, palmette, or “bottle” motif.120 The identification of the “sign” with the Phoenician goddess Tanit might be supported by dedications naming the goddess and showing the motif, although the scholarship—much of it very conjectural—lacks consensus.121 On floors, the “sign” might have an apotropaic function,122 and it was very popular on grave stelai in Punic tophet cemeteries.123 The motif thus raises the possibility that a “Phoenician” patron employed a “Phoenician” mosaicist, perhaps intentionally.

Figure 11. Left: sign of Tanit mosaic from the entrance to the House of the Dolphins, Delos. Various materials. 3.27 m × 1.24 m. Photo: courtesy Sklifas Steven/Alamy. Right: detail of the mosaic. Various materials. Photo: École française d’Athènes.

The house’s eponymous mosaic is found in its open peristyle (Figure 10, room “D,” and Plates 4 and 5), whose main entrance passes through the Tanit vestibule (see Figure 11, left). The floor is framed by a series of black, white, and red rectangular bands and crenellations. At the floor’s center is a series of circular bands and patterned areas in opus vermiculatum, including crest waves, meander, guilloche, astragal, and a marine-inspired tendril with alternating lion and griffon heads, all surrounding a damaged rosette set on a dark floral ground. The small and fragmentary inscription lies between two patterned bands near the central motif: [ΑΣΚΛΕ]ΠΙΑΔΗΣ ΑΡΑΔΙΟ[Σ] ΕΠΟΙΕΙ (see Plate 4, bottom). Each of the floor’s four triangular corner areas contains a winged male figure, usually identified as Eros, riding a dolphin like a horse and leading a second on the rein. Each holds an attribute (see Plate 5): at northwest a caduceus, at southwest a thyrsos, at southeast a trident, and at northeast perhaps a club (it is very damaged), symbols of Hermes, Dionysos, Poseidon, and Herakles, respectively. The thyrsos-bearing figure seems to be the winner of this little race, as his dolphin carries a crown.

While the iconography of the vestibule mosaic seemingly identifies the patron as Phoenician, nothing about the peristyle mosaic’s virtuoso quality or iconography indicates that the patrons or artist were Phoenician. Or at least not until it is read in combination with the sign of Tanit, which can be paired in Phoenician art with one or more dolphins or the prow of a ship in allusion to seafaring, perhaps here a reference to the homeowner’s livelihood.124 The dolphins of the peristyle mosaic are stylized, with their tails intertwined and their postures aggressive. Their alert eyes and toothy jaws recall the similarly zoomorphic bows and long, pointed bronze battle rams of Phoenician triremes.125 These might be intentional references to naval power. When filled with rainwater, this mosaic would become more vital as the dolphins and their riders bearing symbols of divine power seemingly raced around the dynamic circular bands of crest waves, meander pattern, and sea creatures evocative of Ocean encircling the oikoumenē (the “known world”). Hallie Franks has shown that floor mosaics could function as virtual periploi, and here the illusion of movement around a body of water is clear.126 The implied movement might also have other seafaring overtones, encirclement being a naval tactic—one that was used, unsuccessfully, by the Persian fleet at Artemision.127 Three of the divine symbols on the Asklepiadēs mosaic have roles in Phoenician art and religion (the thyrsos does not). The club and the trident appear on coins ranging from the mainland to Spain, sometimes alongside dolphins.128 The caduceus is especially popular in Punic funerary stelai from the fifth century, where it is often shown near or held by the “sign of Tanit.”129

Without speculating as to the meaning of any one of these motifs, it is possible to read the mosaic iconography of this house as part of a single socioreligious program, one that is Phoenician in design, even if it appears to us Greek in terms of its technique and style and in most of its iconography. Yet even if the allusion to maritime prowess had personal meaning, it is likely that the Dolphin mosaic was generic, like most Delos mosaics. Marine themes were popular on the mercantile island.130 Thus in a number of different ways the Dolphin mosaic underscores the danger of assuming that iconography, and even style, are always good indicators of an artist’s or patron’s identity. Asklepiadēs’s work is indistinguishable from that of Sōphilos. (Of course we do not know that Sōphilos was a Hellene, either.) Lacking the ethnic “of Arados,” Asklepiadēs would be presumed a Greek with an appropriate theophoric name. Without the vestibule’s reference to Tanit, the patron and the program might have been viewed as Greek, too, or at least “fully Hellenized.” We must accept that many mosaicists, even those like Asklepiadēs who produced some of the genre’s finest works, would not have considered themselves Hellenes. The artist signature in the House of the Dolphins proves that the work of non-Hellenic mosaicists was acceptable. Perhaps it was even unremarkable. Further, because the Tanit mosaic, not the Dolphin mosaic, was in the most public area of the house, we must reject the idea that picture mosaics were intended to make their patrons appear more sophisticated in a particularly Greek manner.

The deployment of Greek iconography and style, the exclusive appearance of Greek in artists’ signatures, and the pro-Greek perspective of mosaic’s one appearance in literature have contributed to the idea that picture mosaics were invented and made by Greeks. Yet these assumptions cannot stand: there is no direct continuity between Greek pebble mosaics and tessellated ones; Hellenistic centers at Delos, Alexandria, and Pergamon were not populated exclusively by innovative Hellenic artists; the appearance and popularity of mosaics in Sicily and Italy cannot be explained only in terms of acculturation; Punes, Sicilians, Italians, Anatolians, Levantines, and Egyptians made clear contributions to the development of paved floors; and we cannot, with our current knowledge, propose meaningful or direct connections between Greek iconography, technique, and the origins of an artist or patron. Altogether these observations suggest that the cultural milieu of picture mosaics was not Hellenic, certainly not exclusively.

Moreover, the origins of tessellation itself upset the idea that tessellated mosaics were once Hellenic and later became part of the Mediterranean koine. Rather than signaling Hellenic culture, these mosaics seem to promote some other kind of status. Probably they should be read as a sign of participation in an ever-greater Mediterranean elite environment, one that in this case downplays or even lacks cultural specificity. It makes sense to think about what was new in this period in order to contextualize the invention of picture mosaics. While monumental painting was long established in parts of the Balkan Peninsula by this period, painted pavements were rare after the Bronze Age; the same can be said of Egyptian painted floors.131 The greatest concentration of preserved mosaics are in Pompeii, Delos, and Pergamon (we can only speculate about the Seleukid courts), that is, both in Hellenistic courts and in Hellenistic/Republican domestic contexts with known wall painting traditions. It seems likely that vermiculatum mosaics were a technological development stemming from the desire to increase the painterly qualities of durable floors. Although the evidence is entirely circumstantial, I think it is probable that, like the kouros, the picture mosaic was first created through contact between artists trained in Greek and Macedonian regions with Egyptian arts and artists, in this case, in the context of the Ptolemaic royal court.

While we should not assume all mosaics were patronized for the same reason, and while mosaics did serve practical purposes (Vitr. De arch. 7.1), conspicuous consumption was a key impetus. Ruth Westgate has discussed conspicuous consumption in the domestic sphere of the sort on display at Delos. A greater square area was used for circulation and entertainment in Hellenistic homes than in their counterparts from the Classical period. One result was the appearance of decoration in more rooms, especially those suited to receiving guests. A corresponding likelihood is that greater numbers of people saw their decoration, as suggested by the extensive mosaic program in the House of the Masks at Delos or the baths of the Philadelphian villa mentioned in the Zenon papyrus.132 Once again, caution should be taken in equating such status markers with Greekness. The signatures themselves remind us of this point: “of Alexandria,” “of Samos,” “of Arados.” Viewed in this light, individual mosaics might say, “like the royal court,” “from a distant island,” or “by an artist from our homeland.”

We do not know if Asklepiadēs ever worked on the Phoenician mainland or if the decorated floors in the House of the Dolphins mirror, in some way, what was happening in Phoenician cities. But I think it is accurate to say that some contexts, such as Hellenistic Delos, had specific social conditions that generated demands for ever more lavish and creative mosaic programs. Like these floors, the signatures may be expressing not the objective ethnic or cultural identity of an ancient artist or patron but rather civic or social identities particular to such contexts. Picture mosaics might have served a number of social functions. Their style and iconography signal they were generally decorative and playful, a physical manifestation of good taste derived from the strong connections that gave rise to tessellation, spread innovations in tessellation and vermiculatum far afield, and helped shape the very Mediterranean perspectives of which they were a part.

Greeks were quite interested in their cultural origins, and Egypt ranked highest among all sources (e.g., Hdt. 2.35). Yet because of fixed perceptions about the exceptional qualities of Greek art, the kouros is almost always presented as a response to Egyptian art that was eager to distance itself from its source. This oppositional reading seems to be an inversion of the function of the type. The connection between the divine, the elite, and the cultural authority of Egypt is constantly replicated in and reinforced by the form.133 The kouros operates in a way similar to its prototype insofar as both are signs that, for example, use walking to demonstrate vivacity.134 This point is evident when we remind ourselves that, for all the individuality, experimentation, and regional diversity seen in the type, the point of reference is not abandoned because of its lack of expressive naturalism. Instead, the type persists until a major political and social upheaval required that it be changed,135 which helps us understand that the most important role of the kouros within the polis was to demonstrate the power and privilege of elites.

Conversely, the popularity of the picture mosaic beyond the Hellenistic courts is regularly cast as emulation or acculturation. In order to maintain the idea that picture mosaics are evidence of Hellenization, scholarship, perhaps unwittingly, continually asserts the Hellenism of mosaics and their makers regardless of the lack of explicit evidence or evidence to the contrary. It should be clear that this reading cannot hold either. One of the chief social functions of the mosaic was to signal participation in the elite Mediterranean milieu, by which I mean costly signaling through art without cultural specificity. I do not claim, however, that the picture mosaic does not belong to the history of Greek art. Rather, unlike the case of the kouros, we possess direct evidence that neither its artists nor its patrons (and certainly not its contexts) were exclusively Greek, even in the broader sense in which one might employ that term in the Hellenistic era.

Although only rarely transported, the picture mosaic shares a number of similarities with objects that circulated. The later Iron Age Mediterranean provides a number of examples, such as the Lyre-Player Group of scaraboid seals. There is familiar debate about precisely where these objects were made and how to associate their iconography with any place in particular. They date to the second half of the eighth century.136 As their conventional name suggests, many show anthropoid figures playing the lyre.137 There is general agreement that the seals were made in the eastern Mediterranean, likely Syria, but their distribution spreads across the Mediterranean as far west as Huelva, Spain (Figure 12).138 The seals’ functions differ by region. At sites farthest west (with the possible exception of Huelva), they are found in burials and, at some of these sites, including Pithekoussai, mounted on silver hoops or thread for personal adornment or protection; nearly all come from sanctuaries in “mainland” Greece and Cyprus; and, in the Near East, they are found in occupational debris. So at Euboean Lefkandi, the Lyre-Player Group seals were used principally as dedications, whereas those from the Euboean colony of Pithekoussai were personal protective amulets found in funerary contexts.139

While such uses are not mutually exclusive, the regional division even among Greeks (although identity is complicated at Pithekoussai) suggests significant difference in beliefs while at the same time offering indisputable proof of widespread receptivity to the seals. We should pay attention to what the Lyre-Player seals tell us. They show how the function of similar-looking objects can vary in ways that are socially determined, even by people we imagine are closely related. All of these objects might be understood as art forms produced and sustained by ongoing interaction, although in the case of picture mosaics it seems to have been the artists, rather than the objects, that circulated. Each testifies to the art of contact’s resistance to easy definition. We should not expect arts produced by contact to belong exclusively to one region, cultural or ethnic group, or visual tradition.

Figure 12. Distribution of Lyre Player Group seals. Map redrawn with minor changes and additions by Sveta Matskevich after Boardman 1990, fig. 20.

The approach to these objects should be different from the approach to those with single sites of manufacture informed by a fairly cohesive visual tradition, such as Athenian pottery, even if the latter were also distributed broadly.140 Something quite different is happening with the kouros, as its consistency must be important to its function. It seems that the movement of patrons spread the type to specific sanctuaries and poleis. In suggesting that the kouros was an emulation of Egyptian art—and was not fundamentally interested in distinguishing the “homemade” from the “foreign,” least of all the “Hellenic” from the “barbarian”—I have challenged ideas about Orientalizing Greeks and the inherent originality of Greek art. A brief discussion of the origins of Phoenician monumental sculpture will show how entrenched and limiting these views can be in the discourse of Phoenician art as well.

What we know of Phoenician art of the Iron Age shows that it was openly engaged with Egyptian art, but there was no major tradition of monumental stone sculpture in this period.141 Once again military activity in Egypt seems to have been the key to the invention of a monumental sculpture industry. According to Herodotos (3.10–19), Phoenicians accompanied Cambyses (r. 529–522) on his Egyptian campaign. A careful reading of the source material suggests that the navy played an important role in this conflict.142 After the circa 525 Persian conquests of several cities, including Memphis, Cambyses made plans to advance on other areas (3.17).143 At some point when they were in Egypt, Sidonians took from a sculptor’s workshop, or perhaps directly from a Saïte nekropolis, three stone anthropoid sarcophagi made for local elites.144 The sarcophagus in Figure 13 already had an Egyptian inscription naming its occupant, a general named Pa-en-Ptah. Pa-en-Ptah’s sarcophagus was excavated in the ‘Ayaa nekropolis east of Sidon. It was interred with a new occupant, the king Tabnit, identified by a Phoenician inscription added to the foot of the figure (Figure 13; see Figures 21 and 23). Tabnit’s mummified corpse was found inside on a wooden plank.145

With Tabnit’s sarcophagus was found the second looted one, incomplete and lacking an inscription; a female was found inside.146 The third sarcophagus was found in another Sidonian cemetery, Magharat Abloun (Figure 14; see Figures 22 and 24). It was not yet complete when stolen, and a Phoenician inscription naming its occupant was added to the front of the body. This epitaph of Tabnit’s successor King Eshmunazar II is twenty-two lines long and well preserved.147

It is widely agreed that these looted sarcophagi were the progenitors of a peculiar Phoenician sculptural type known conventionally as anthropoid sarcophagi (Figures 15 and 16). Around one hundred and twenty of the sarcophagi are known. They come almost exclusively from Phoenician areas, the majority from Sidon (fifty-nine) and Arwad (twenty-eight). None has been found so far in Tyre.148 Unfortunately, no anthropoid sarcophagi have identifying inscriptions, although traces of paint are visible on some examples, suggesting there might once have been.149 Many were made of Parian or other Cycladic marble, and so Aegean quarries and, likely, Greek craftsmen were important parts of the production.150 The earliest anthropoid sarcophagi are thought to date to around 480 or 470; the latest are usually dated to around the time of Alexander, but probably the type persisted into the Hellenistic period.151 Their chronology within that range is also disputed and rests on several criteria concerning archaeology, changes in the overall form, and rightly disputed ideas about their relationship to Egyptian and Greek art.152

Figure 13. Sarcophagus and mummy of Tabnit from the ‘Ayaa Nekropolis near Sidon, ca. 525. Made in Saqqara or Giza. Istanbul, Archaeological Museum 800. Amphibolite. Ht. 2.32 m. Detail photo: author’s own. Overview photo: Art Resource, N.Y.

The anthropoid sarcophagus shares with its Saïte prototype its basic form and emphasis on the representation of the head. Occasionally other parts of the body are shown—feet, hands, knees, and so forth—or indicated on the lower half, such as the calves or buttocks. Some heads have Egyptian features, but they differ from the exaggerated and stylized features of the looted sarcophagi. As with the kouros, we lack for these objects a working out of the type in reaction to its Egyptian predecessor. The picture is only complicated by the sarcophagi that draw upon Greek art, both Archaic and Classical, in the approach to the hair or face (Figure 16, center and right).153 Some sarcophagi even combine features from Egyptian and Greek art, pairing a visage and hairstyle that recall Greek sculpture with the Egyptian box beard and klaft headdress (Figure 16, left).154 According to the accepted date for the invention of the type in around 480, sarcophagi with Archaic features such as snail curls might best be understood as Archaizing. The classical Greek sources upon which other sarcophagi draw, from Severe Style sculpture to Attic grave stelai to Pheidias and Polykleitos, have great longevity in Hellenistic and later sculpture.155 It is possible that those features are Classicizing. If so, the stylistic criteria used to date these objects must be reviewed.

Figure 14. Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II from the nekropolis of Magharat Abloun near Sidon, ca. 525. Made in Saqqara or Giza. Paris, Musée du Louvre AO 4806. Amphibolite. Ht. 2.56 m. Photos: Art Resource, N.Y.

As one should by now expect from Phoenician art history, nearly every argument about the sarcophagi can be contested. Especially problematic, given the general agreement on their Egyptian origin, is the claim that the sarcophagi were manufactured by Greek workshops in Sidon and accordingly are evidence of the Hellenization of the Phoenician elite.156 Somehow these monuments are caught in the crosshairs of Orientalizing and Hellenization. The presumed lack of Phoenician agency is not surprising given how difficult it is to recover Phoenicians from the material record, yet the numerous parallels in the invention of the kouros and the anthropoid sarcophagi show how much these agential perceptions are ideological. If Phoenicians were eager to emulate Greek monumental sculpture, anthropoid sarcophagi would be a poor choice. Even putting aside the Egyptian features, this stone sarcophagus type is unique to Phoenicians. The two typical approaches to these objects, one emphasizing the important role of Greek sculptors in the invention of the type, the other stressing their gradual Hellenization away from the Egyptian type, are not supported by extant evidence.157 The peculiarity of the type and the experimentation evident in its many variations reinforce the idea that these attempts to assign ethnocultural identities to the objects’ makers is unwise. The final artistic result only seems to us a pastiche, one that is surely indicative of specific, if unknown to us, Phoenician ideologies.

Figure 15. Anthropoid sarcophagi in the Beirut National Museum. Marble. Various sizes. Photo: Erich Lessing.

Those who insist that Greek sculptors carved the first kouroi have little grounds to deny the possibility that Phoenician sculptors made these sarcophagi (compare Figures 7 and 15 and 16). The types share similarities beyond their use in funerary contexts. Both emerge from Egyptian sculpture that is reconfigured according to new artistic conventions (it would not be hard to make the case that the Phoenician result was the more creative of the two). We see in both a lasting interest in the prototype and a desire to set the individual apart or not from other elites. Neither type can be dated on the basis of style without controversy, although this problem is much more acute on the Phoenician side of things, as usual.158 Finally, neither is found outside its cultural sphere. Through a favorable lens, inconsistences or variations in the kouros—nudity for a kilt, for example—have been seen as virtuous expressions of the Greek individual spirit. Yet similar variations—the combination of Archaic snail curls with a box beard, for example—could be interpreted as weaknesses or misunderstandings by more critical interpreters of Phoenician art.159 The “Greek spirit” does not explain the appearance of early kouroi, just as artistic fecklessness cannot explain the Sidonian theft of monumental sculpture from Egypt. It is more plausible to suppose that sixth-century Sidonians stole those sarcophagi from a freshly conquered Egypt because they could, whereas seventh-century Greeks in a newly stable Egypt had to make their own sculptures from the beginning. When Sidonians no longer had access to Egyptian sculpture, they innovated.

Figure 16. Left: anthropoid sarcophagus from the ‘Ayaa Nekropolis near Sidon, 475–450. Istanbul, Archaeological Museum 799. Parian marble. Ht. 2.16 m. Photo: Heidelberg University Library. Center, right: anthropoid sarcophagus from the ‘Ayaa Nekropolis near Sidon, 475–450. Istanbul, Archaeological Museum 798. Parian marble. Ht. 2.22 m. Photo: Heidelberg University Library.

In sum, the first kouroi and first anthropoid sarcophagi can be placed into refreshingly specific historical contexts, both of which emphasize the immense religious, political, and social capital of Egypt and Egyptian art. In clear contrast to the picture mosaic, each of these sculptural forms was found only in certain locations, ones that we would call Greek and Phoenician, respectively. I would again emphasize, however, that the cultural specificity we detect in these works of sculpture does not mean that either was interested primarily in expressing culture itself—as is easily demonstrated by the kouros that was not even patronized by all elite male Hellenes. To that end, it is not unimportant that neither the kouros nor the anthropoid sarcophagus has been found everywhere in areas inhabited by Greeks and Phoenicians, even in areas with other forms of monumental sculpture or stone architecture. Far from it. What each of these case studies shows is how much conventions of interpretation—which are so often shaped by the cultural capital of Greece in modern times—shape our perceptions of works of art, from how and why art was made to what it meant to express and to whom. Many have discussed the difficulty of moving past entrenched ideas of Greek exceptionalism and modern nationalism.160

Of course, Greek exceptionalism was a feature of some ancient thought, too, notably in Pliny’s presentation of Greek art for a Roman audience. There is some evidence that Greeks believed in their artistic exceptionalism. Pausanias comes to mind, as does, more obliquely, the funerary speech of Perikles, in which the statesman famously called on Athens to be “an education to all of Greece” for its appreciations of “grace” and “beauty” (Thuc. 2.41–43). But there is no reason for us to take this self-aggrandizing mythology at face value; indeed, we are obligated to critique it at least as much as we are obligated to critique scholarship that relies on it. One means of doing so is to change our approach, to consider what happens when we refuse to leave unchallenged the Hellenocentric logic of Orientalizing and Hellenization contact models. If we frame the kouros, picture mosaic, and anthropoid sarcophagi more neutrally as arts of contact, we can consider anew how connectivity even between the same areas can have very different artistic results. While these objects are material expressions of particular ideologies, those ideologies should not be understood as deliberately and consciously cultural, and certainly not at all “Western” or “Eastern.” They are much more limited in scope and historically and socially specific in their intent.