From the very beginning of the Achaemenid era there is evidence of cross-Mediterranean Phoenician group consciousness. Herodotus (3.19) reports that the Phoenician fleet on campaign in Egypt refused Cambyses’s demand to advance on the Carthaginians:

Φοίνικες δὲ οὐκ ἔφασαν ποιήσειν ταῦτα: ὁρκίοισι γὰρ μεγάλοισι ἐνδεδέσθαι, καὶ οὐκ ἂν ποιέειν ὅσια ἐπὶ τοὺς παῖδας τοὺς ἑωυτῶν στρατευόμενοι

But the Phoenicians said they would not do it; for they were bound, they said, by strong oaths, and if they advanced on their own children they would be doing an impious thing.1

The relationship with Carthage was not one-sided. According to several Greek sources (Arr. Anab. 2.24.5; Curt. 4.2.10–11; Diod. Sic. 20.14; Polyb. 31.12.12), the Carthaginians sent a delegation annually to their mother city with offerings of first fruits to their patron deity Ba‘al Ṣūr, the god of Tyre—Melqart. Tyre hoped for Carthaginian support during Alexander’s siege (Diod. Sic. 17.40.3; Just. Epit. 11.10.12), although Quintus Curtius reports that Carthage was overwhelmed by war at home and could only take wives and children to safety (Curt. 4.3.19–20). Carthage’s response to her 310 siege by Agathokles of Syracuse was to renew offerings to the mother city, having lapsed in the effort and angered Melqart (Diod. Sic. 20.14.1–3). We are reminded periodically in other accounts of the connectivity of Phoenicians, as when the Sidonians who helped Alexander lay siege to Tyre are said to have secreted away fifteen thousand Tyrians to safety (Curt. 4.4.15–16). Greeks, at least, saw connections between Phoenician city-states in the Persian and Hellenistic eras.

All the same, we must recognize that it is inherently problematic to seek Phoenician collective identity through Greek and Roman textual evidence. The same passage describing the siege of Carthage in Diodoros gives us one reason why: it describes a mass child sacrifice (Diod. Sic. 20.14.4–6). While there is good evidence that Carthaginians practiced child sacrifice in the tophet sanctuary, there is no evidence (yet?) of this practice at home.2 Moreover, Diodoros’s account is sensational in its description of the magnitude and callousness of the rites. Other reasons to be skeptical of Greek and Roman source material were articulated by Irene Winter, who showed that the supposed ethnonym phoinix was in fact principally literary, and by Jonathan Prag, who demonstrated poenus was as well.3 The same can be true for “Sidonian,” a sometime metonym for Phoenician (as at Il. 23.743). Homer’s Phoenicians are most explicitly literary; Herodotos’s are more historical, although still often vague (we have seen how the periploi can be confusing, too); and Thucydides’s repetition of the threat of the “Phoenician fleet” turns the very real power of the Persian navy into a looming off-stage character. The Hellenistic historians inherited these views.

Rather than survey this evidence, a project that has been undertaken several times before,4 this chapter seeks to understand the emic evidence. I argue that the Persian period is the first time one can point to explicit archaeological evidence of a self-conscious Phoenician identity, one that continues and grows even as imperial control over the Phoenician city-states changes hands from the Achaemenids (530s–330s) to Alexander (330s) and thence to a chaotic period in which various successors battled for control over Alexander’s empire.5 The process by which Phoenician identity emerged certainly began in the Iron Age, and it is likely that the crucible of the Persian Wars helped shape it. Greek sources suggest that the period between Alexander’s conquest and the eventual Ptolemaic takeover, a period in which the Phoenician city-states were frequently besieged and suffered great losses, could have helped this group consciousness along.

I want to acknowledge from the beginning that this kind of thinking is somewhat conventional, even if it has not been pursued seriously on the Phoenician side of things, and the arguments that follow stem from a conservative approach to historical analysis, source criticism. I hope to demonstrate that we can take the lessons of the previous chapter and apply them in a number of ways, here, by highlighting the Phoenician evidence and entertaining the possibility that some Phoenicians and some Greeks reacted to the events of the late sixth and fifth centuries in similar ways. The reasons for the rise of Phoenicianism are of course more complex than an upwelling of nationalism through armed conflict and occupation. I suggest that they must be understood in terms of fifth-century political changes that reshaped eastern Mediterranean economies. These changes never led to the creation of a Phoenician state, however, nor of a monoculture, and it remains difficult even in this period to pin down “a” Phoenician culture or artistic style.

To illuminate Phoenician self-ascription, this chapter discusses monumental art, including inscriptions, and portable art—coins—from the Persian and Hellenistic periods. The advantage of considering monumental art is that we can be reasonably certain of its intended context of display. It offers considerable insight into elite, often royal, self-presentation. This section closes with two bilingual inscriptions from Attika that allow for the comparison of emic and etic representational strategies. Coins flesh out the picture by showing how state identity was constructed and conveyed in portable form. Altogether the written and visual evidence reveals glimpses of a sophisticated self-consciousness and autonomy rarely acknowledged in Persian-and Hellenistic-period Phoenicians or their art. The stability of identity and evidence of independence are all the more remarkable for enduring through this often-turbulent period.

The compelling corpus of Phoenician epigraphy is for the most part published, but our understanding of the language’s vocabulary, grammar, and syntax is limited. There are around ten thousand texts in the extant corpus,6 and we know only about two thousand words total.7 Phoenician is a sometimes difficult, largely consonantal, language, in which small differences in the interpretation of letter forms can lead to major differences in translation or date. When inscriptions are not formulaic, experts can disagree about them to such an extent that the navigation of their arguments can seem nearly impossible.8 It is clear that we must proceed with caution and be wary of aligning inscriptions with historical events recorded in other sources. Difficulties of interpretation notwithstanding, these texts, as well those written in Greek by or for Phoenicians, are precious. Most Phoenician language inscriptions of the Persian and Hellenistic periods are votive and funerary, written in the varied dialects of the regions in which they were found.9 Inscriptions from these periods have turned up in all the major city-states and sites, with the fewest coming from Tyre. Byblos has only a handful, but they are important. The sanctuary of Umm el-‘Amed has a number of inscriptions, but Sidon (including the Eshmun sanctuary) is the richest source.

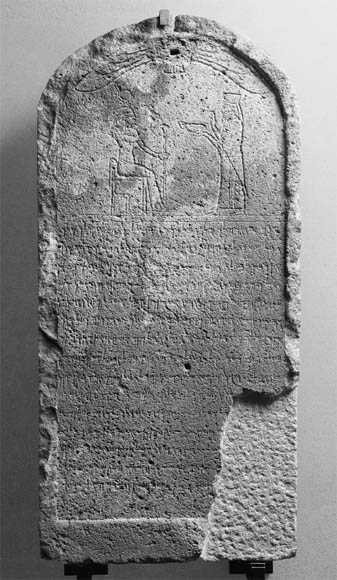

Evidence of a Phoenician approach to expressing identity begins with simple onomastic formulae.10 For both males and females, common folk and royals, theophoric idionyms were popular. In Phoenician-language inscriptions, family and civic identities are expressed, the former sometimes concerning multiple generations, the latter through toponyms (rarely ethnonyms as in Greek).11 Bilingual inscriptions likewise emphasize ancestry and use civic toponyms. Take for example the inscription on the Yehawmilk stele from Byblos, dated to the mid-fifth century on paleographic and archaeological grounds (Figure 19).12 It begins:

ʾnk yḥwmlk mlk gbl bn yḥrbʿl bn bn ʾrmlk mlk gbl ʾš pʿltn hrbt bʿlt gbl mmlkt ʿl gbl

I am Yehawmilk king of Byblos, son of Yeharba‘al, grandson of Urimilk king of Byblos whom the lady Gebal Ba‘alat made ruler over Byblos.13

The remaining lines describe Yehawmilk’s construction of a shrine or portico (ʿrpt) in honor of the city’s principal deity, Ba‘alat Gebal, familiarly known as the “Lady of Byblos”; a request for her to reciprocate; and warnings about violating her temple. The image on the upper portion of the round-topped limestone stele expands upon the text and the implied intimacy between goddess and king. At the top is carved a winged disk, a long-lived symbol of religious significance for Phoenicians and perhaps here a reference to Ba‘alat Gebal’s temple gateway inlaid with a golden winged disk (lines 5–6).14 A mark for a metal peg remains in the stone to surmount the stele with a metal attachment, raising the alternate possibility that the golden disk in the inscription refers to the stele itself.15 The carved disk stretches over an enthroned Ba‘alat Gebal fashioned as Hathor. She holds the wadj (papyrus scepter) and wears a headdress with horns flanking a sun disk. Before her is the robed king with a cylindrical crown, extending an offering cup with one hand and making a gesture of supplication with the other.

Yehawmilk’s costume is similar to the cylindrical hat and ceremonial costume found in Persian art.16 In concert with the representation of Ba‘alat Gebal as Hathor, the stele tempts scholars to emphasize external “influence” and emulations.17 There is no reason to see this particular combination of features as “foreign,” however. The selective use of Egyptian iconography and architectural elements is already familiar to us from the few extant examples of Phoenician Iron Age art, including gravestones, as well as the Persian period anthropoid sarcophagi and naiskoi at ‘Amrit. Use of Persian costume to signify state power is also found on coins of Sidon (see Figure 37, discussed below).18 Further reference to Persian-granted authority is found in other inscriptions, including the Eshmunazar sarcophagus (referencing ʾdn mlkm, “the lord of kings”).19 The result on the Yehawmilk stele is not disjointed but seamless, as self-assured as the content of the inscription itself (the letters are somewhat clumsily carved, however). We should not read the imagery in a totally different way from its inscription. The stele is evidence of self-fashioning in terms that are simultaneously interconnected and, like the Byblian dialect itself, distinct.

A funerary inscription from Byblos is found on the sarcophagus of Batnoam, dated to around 400 (Figure 20). It indicates that Byblian funerary practices were consciously conservative:

Figure 19. Yehawmilk stele from Byblos, ca. 450 (= KAI 10). Paris, Musée du Louvre AO 22368. Limestone. Ht. 1.12 m. Photo: Art Resource, N.Y.

Figure 20. Detail of inscription on Batnoam sarcophagus from Byblos, ca. 400 (= KAI 11). Beirut, National Museum. Marble. 0.94 m (length of inscription). Photo: author’s own.

bʾrn zn ʾnk btnʿm ʾm mlk ʿzbʿl mlk gbl bn plṭbʿl khn bʿlt škbt bswt wmrʾš ʿly wmḥsm ḥrṣ lpy kmʾš lmlkyt ʾš kn lpny

In this coffin lie I Batnoam, mother of king Azba‘al, king of Byblos, son of Palitba‘al, priest of the Lady, in a robe and with a tiara on my head and a gold bridle on my mouth, as was the custom with the royal ladies who were before me.20

Here as on the Yehawmilk stele is the onomastic formula tying together lineage with theophoric names (iterations of Ba‘al), city-state, and city deity, in this case shortened to just her honorific title, Ba‘alat. Batnoam’s ceremonial clothing is described as well as the “gold bridle” used to prepare her body for burial. Continuity of custom is emphasized in the final part of the inscription. While bearing in mind this is a funerary inscription, not a votive stele, and for a royal mother, not a king, it is nonetheless important to note how the accompanying visual properties are much different from those of Yehawmilk’s stele. Batnoam’s sarcophagus is in imported white marble, not limestone, and the surface is otherwise plain. It is not clear that it was meant to be plain, however, as tool marks are still apparent on all visible surfaces, proving that at least the fine smoothing was never done. Perhaps it was intended to take an anthropoid form,21 but it is usually presented as a deliberately rectilinear sarcophagus (called a thēkē, or “chest,” by scholars) of the type found also in Sidon. Unfortunately our evidence is insufficient to speculate further.

Figure 21. Details of Sarcophagus of Tabnit (Figure 13).

Three Sidonian royal funerary inscriptions can be used for comparison. Two were introduced in Chapter 2, the looted basalt sarcophagi of King Tabnit and his son Eshmunazar II (Figures 13 and 14; Figures 21 to 24). The lids of both sarcophagi represent the deceased wearing a funerary mask, wig, stylized beard, and broad collars terminating in falcon heads. Tabnit’s has a representation of a kneeling Isis with sun disk crown, wings outstretched in protection (Figure 21, left). While the two sarcophagi are similar stylistically, they are not by the same hand.

There are a number of differences in the approach to the facial features and hair (Figure 22). Eshmunazar’s overall form is squat, with virtually no articulation of the body (see Figure 14), which seems to be the intended result for the unfinished third looted sarcophagus holding an unidentified female, perhaps his mother, Amotaštart. Tabnit’s is slimmer, with more articulation of the form near the knees, the muscle and bones of the knees and shins being clearly visible below the hieroglyphs (Figure 21, right). For reasons that cannot be known to us, the extant hieroglyphic inscription on the cover for General Pa-en-Ptah was not removed from Tabnit’s sarcophagus. The eight-line inscription honoring Tabnit was written on the feet instead (Figure 23; see also Figure 13). It begins with the now familiar onomastic formula of name, city, and city goddess:

ʾnk tbnt khn ʿštrt mlk ṣdnm bn ʾšmnʿzr khn ʿštrt mlk ṣdnm škb bʾrn

I Tabnit, priest of Aštart, king of Sidon, son of Eshmunazar, priest of Aštart, king of Sidon, am lying here in this coffin.22

Figure 22. Detail of Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II (Figure 14).

The following lines concern warnings about violating the burial similar to those found on the Yehawmilk stele, although for a different context.23

Similar warnings are found on Eshmunazar II’s sarcophagus (Figures 14, 22, and 24).24 Eshmunazar’s inscription is in the expected location, on the lid of the sarcophagus, and is, fittingly, much longer (Figure 24). The twenty-two lines tell of his status, lineage, and untimely death; his mother Amotaštart’s regency; and their dedications to Aštart and Eshmun. Lines 18–20 give us the best extant information about Sidon’s political position in the early Persian period:

Figure 23. Detail of Sarcophagus of Tabnit (Figure 13).

[18] . . . wʿd ytn ln ʾdn mlkm

[19] ʾyt dʾr wypy ʾrṣt dgn hʾdrt ʾš bšd šrn lmdt ʿṣmt ʾš pʿlt wyspnnm

[20] ʿlt gbl ʾrṣ lknnm lṣdnm lʿl[m] . . .

[18] . . . furthermore the lord of kings gave us

[19] Dor [dʾr] and Joppa [ypy], the rich lands of Dagon/corn that are in the plain of Sharon, as a reward for the striking deeds that I performed; and we added them

[20] to the borders of the land, that they might belong to Sidon forever . . .25

The towns mentioned in line 19, Dor and Jaffa, have been identified in the north and south of the Sharon Plain, respectively, and prove that Sidon’s control southward was considerable.26

Figure 24. Detail of Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II (Figure 14).

Neither Eshmunazar II’s name nor any other name among the kings in his dynasty is recorded in Greek or other sources. The vague language of these inscriptions has led to a debate over the date of the dynasty. I follow what is called the “high chronology” by those who have worked on the date of the sarcophagus. In the high chronology, the inscriptions are thought to date to the late sixth or early fifth century. A conservative reading of the extant information suggests that the Sidonians obtained these sarcophagi on campaign in Egypt, possibly with Cambyses.27 I think it possible that Tabnit died on campaign and was prepared there for burial at home.28 This scenario might also explain why his funerary inscription was hastily put on the feet on the sarcophagus and why Eshmunazar II became king when still a child, perhaps an infant, and was richly rewarded for service to the king.29 If so, Cambyses or Xerxes would be the “lord of kings” mentioned in line 18, perhaps having granted power to Sidon for assistance with the Egyptian or Greek campaigns, respectively. This is, of course, just speculation, though it complements nicely the visual information. These prototype sarcophagi seem especially poignant in this historical moment, as they refer to Egypt and her domination by the Persians that was brought about, in part, by Sidonians.

Another royal inscription comes from the Eshmun sanctuary found near an orange grove just outside Sidon referred to as Bostan esh-Sheik (Figures 25 and 26).30 It was inscribed on the base of a marble child statue in the late fifth to mid-fourth century (Figure 27).31 The one-line inscription is for a prince Ba‘alshillem from another Sidonian dynasty:

hsml z ʾš ytn bʿlšlm bn mlk bʿnʾ mlk ṣdnm bn mlk ʿbdʾmn mlk ṣdnm bn mlk bʿlšlm mlk ṣdnm lʾdny lʾšmn bʿn ydl ybrk

This (is the) statue [sml] that Ba‘alshillem son of king Ba‘na, king of Sidon, son of king ‘Abdamun, king of Sidon, son of king Ba‘alshillem, king of Sidon, gave to his lord Eshmun at the Ydl-Spring. May he bless him!32

While the inscription is formulaic, the statue and its context are intriguing. The Ba‘alshillem II statue is one of a popular type at the sanctuary made of marble and limestone. These are sometimes referred to as “temple boys” after the conventional name for the Cypriot prototype.33 The earliest child statues at Bostan esh-Sheik are in limestone and stylistically Cypriot. Soon thereafter some statues are made of marble and are stylistically Greek. The Ba‘alshillem II statue is an example of the latter. We do not know exactly how these statues were used or where precisely they were originally displayed.34 The Ba‘alshillem II inscription indicates that this statue was meant to represent the prince himself as a gift to Eshmun in exchange for protection.

How we interpret this work in terms of Sidonian royal identity very much depends on understanding its general context. The Eshmun temple complex had a long use from the seventh century to the Byzantine period. In the early Persian period Bodaštart, grandson of Eshmunazar II, built its monumental platform.35 Owing to its long use, erratic excavation, and modern looting, very little is known about the structures that once stood on this platform, if any. The hundreds of architectural fragments recovered from the site, many of which have since been lost, show that builders drew on a variety of elements, most explicitly (and logically) Achaemenid royal architecture.36 A few features of the later Persian and Hellenistic sanctuary are especially relevant to this discussion. One is a structure northeast of the monumental platform of unknown function containing water basins, offerings, and a number of small rooms (Figure 28). In plan, the building’s closest extant parallels, although they are only general, come from Levantine-built structures on Delos, the clubhouse of the Poseidoniasts of Beirut (see Figure 39) and the sanctuary of the Syrian gods Atargatis and Hadad.37

The building’s decorative friezes are poorly preserved. They show children engaged in various activities and are original to the structure. Their style supports a Hellenistic date.38 The friezes are further proof of the activity of sculptors trained in Greek workshops. Sharing a wall with this building is a structure in front of the main platform, the so-called Bassin d’Astarté (Figure 26). The rectilinear building was once flooded. The back wall had a frieze of children engaged in a hunt and a niche in which was set a so-called Aštart throne, a quasi-aniconic object type found in Sidon, Tyre, and related sanctuaries that was composed of a throne flanked by lions or sphinxes. One throne from Tyre dated to the second century is inscribed with a dedication to the goddess.39 The functions of these adjacent buildings are not known, though water seems to have been important to both at different points in their use, recalling the ‘Amrit temple (see Figure 18).

Figure 25. View of Bostan esh-Sheikh taken in 2013. Photo: author’s own.

Figure 26. Site plan of the Sanctuary of Eshmun at Bostan esh-Sheikh. Plan redrawn by Sveta Matskevich after Liban, l’autre rive, 135.

Figure 27. Statue of Ba‘alshillem II found near the Eshmun complex at Bostan esh-Sheikh, ca. 425–350. Beirut, National Museum. Marble. 0.50 m (length of inscription). Photo: Jessica Nitschke.

Finally, at the base of the monumental platform was found the most famous object from the sanctuary, the so-called tribune of Eshmun that is said to have “enormous bearing on the ‘Hellenization’ of Sidon during the period of Persian domination” (see Plates 12 and 13; its findspot is indicated in Figure 26).40 It was set into a semicircular stone area, the centerpiece of which was a standing stone in the form of a pillar. To the right of the pillar was found the limestone foundation on which the marble “tribune” once stood. It was surely made by Greek-trained sculptors and takes the form of a Greek monumental altar in-antis. Because its moldings are similar to those used on the Alexander Sarcophagus and those sarcophagi found with it, possibly the same sculptor or workshop made all these works in the early Hellenistic period.41 Its two friezes show a gathering of the gods and, below, a revelry. This iconography is Greek, and although attempts have been made to tie the program to Eshmun, no connection is really detectable (that does not mean Sidonians made no connections, of course).42 The object’s function is debated. The fine marble Aštart throne seen in Figure 29 once sat on top of it, as seen in the reconstruction in Figure 30.43 Because it was set with its open side facing a retaining wall, it could not have functioned as an altar. The circumstances in which it was found suggest either reuse, misunderstanding, or rejection of its intended function.

Figure 28. Plan of the building of uncertain function with children friezes at Bostan esh-Sheikh, probably of early Hellenistic date. Plan redrawn with minor changes by Sveta Matskevich after Stucky 1997, fig. 3.

The combination of elements—aniconic standing stone, Greek altar with reliefs, and an Aštart throne—offers a fascinating window into the world of Sidonian art and religion of the early Hellenistic period. The use of this altar-as-statue base for an Aštart throne could only happen in the repertoire of Phoenician art. It is certainly poor evidence of acculturation. The Greek style of the late fifth-century statue of Ba‘alshillem II does not, therefore, signal a clear shift in the style of dedications at the sanctuary or a gradual loss of Sidonian religious practices to Greek ones. In fact, children statues appear in Greek sanctuaries in smaller numbers and only about a century after the Ba‘alshillem statue was dedicated in Sidon.44 In the second century and later, marble statues of Greek and Roman deities begin to appear at the site, mainly of Asklepios, Hygeia, and Dionysos and his retinue.45 These statues, too, might best be framed in terms of the complex aggregations that were long established in the sanctuary. Although Vella has shown that there is no single plan or style in Phoenician sanctuaries of the Persian and Hellenistic periods,46 it is possible to detect a number of conceptual parallels between the Eshmun sanctuary complex and the ‘Amrit sanctuary, from the stress placed on water in religious contexts to the strategic use of Achaemenid, Cypriot, or Greek imagery to the peculiar combinations of those traditions with extant (local, Phoenician) traditions of art and architecture.

Figure 29. Marble Aštart throne from Bostan esh-Sheikh that once sat on top of the so-called tribune (altar) (Plates 12 and 13). Beirut, National Museum 2067. Marble. Ht. 1.44 m. Photo: author’s own.

Figure 30. Reconstruction of the arrangement. Plan redrawn by Sveta Matskevich after Kawkabani 2003, fig. 8.

The sanctuary at Hammon, now called Umm el-‘Amed and located less than twenty kilometers south of Tyre, offers yet another opportunity to consider the approach to Phoenician self-representation in a religious context (see Map 3 and Figure 31).47 Although there is evidence of earlier occupation at the site, the initial phase of construction of the large sanctuary complex dates to the late fourth to early third centuries. The sanctuary was active until its decline in the first century BCE. It has two sacred enclosures, one dedicated to Milk ‘Aštart, a god related to Aštart and Melqart,48 and another to an unidentified deity in the so-called East Temple. In plan, both enclosures are courtyards surrounding their respective temples, a long-lived arrangement for sacred space in the Levant. Each has a number of other features, such as porticoes, various smaller rooms, and, in the Milk ‘Aštart enclosure, a colonnaded hall.49 The hall is a good example of the kind of combinations seen elsewhere at this and other sanctuaries. The form is found in ceremonial use in a number of locations, from Anatolia to Egypt and Achaemenid Persia. But the hall’s appearance here in a sacred enclosure is unique, as is its use of Greek-style columns, Ionic on the exterior and Doric on the interior. Additional structures including a portico in the Milk ‘Aštart complex also selectively employ Greek architectural orders, whereas other features are embellished with the long-popular disk and uraei.

Figure 31. Plan of the sanctuary at Umm el-‘Amed. Plan: after Dunand and Duru 1962, fig. 20 modified by Nitschke 2007, fig. 136. Courtesy of Jessica Nitschke.

Two fragmentary orthostats found in the Milk ‘Aštart complex show young bulls on the attack, one of which charges at a stylized tree.50 Their poses and style have drawn comparison to some of the carved ivories as well as a stele from the Eshmun sanctuary.51 Two other fragmentary orthostats show a cultic scene in which the human figure interacts with a column topped by a volute (“Aeolic”) capital, an architectural element also found in some ivories and, from a variety of periods, at sites in the upper Galilee (Hazor), Judah (Ramat Rachel), and Cyprus (Golgoi, Tamassos). A limestone block with reliefs on three of its four sides of uncertain function was also found in this complex.52 It shows male figures engaged in various cultic activities: interacting with a tree of life, carrying a censer, and making gestures of supplication. Stylistically and in terms of content, all of these reliefs seem to fit with Iron Age Levantine portable objects or preexisting art and architectural practices, though it is not clear how specific or significant these relationships might be. The small amount of sculpture recovered thus far from Phoenicia makes it difficult to say whether or not we should associate the reliefs with a monumental “Phoenician style” of Hellenistic art. The damaged state of these objects only makes that task more difficult.

There are works in the sanctuary that are exclusively Phoenician, however, such as the Aštart throne found in the East temple.53 Another example of Phoenician monumental art is the well-preserved statue of one ‘Abdosir that was found near the main entrance of the Milk ‘Aštart temple (Figure 32).54 It is inscribed in Phoenician, as are all the inscriptions from the site:

lʾdny lmlkʿštrt ʾlḥmn ʾš ndr ʿbdk ʿbdʾsr bn ʾrš zkrn kšmʿ ql[y] ybrk

To my lord, to Milk ‘Aštart, god of Hammon, that which your servant ‘Abdosir, son of Arish, vowed as a memorial when he heard (his) voice. May he bless him!55

The statue shows ‘Abdosir in the familiar striding pose wearing a short kilt. His right arm was once bent upward, likely in a gesture of supplication. The statue is dated to the third or second century and shows the use of a type known in the Iron Age and popular in some sanctuaries in the Persian period.56 There are other Egyptian/izing elements in the sanctuary that are new as well, such as the Egyptian- (not Levantine-) type sphinxes that Nitschke has interpreted as Ptolemaic portraits.57 A few marble dedications were executed in Hellenistic Greek styles.

Figure 32. Statue of ‘Abdosir from Umm el-‘Amed, 3rd or 2nd c. Beirut, National Museum 2004. Limestone. Ht. 1.02 m (preserved body), 0.45 m (base). Photo: Jessica Nitschke.

A group of sixteen Hellenistic limestone stelai from the site and its vicinity adds to this intriguing assemblage.58 These stelai show males and females engaged in ritual activities (Figures 33 and 34). Their precise function, votive or funerary, is debated.59 The best-preserved male reliefs have a number of parallels to the earlier Yehawmilk stele (see Figure 19): a winged disk with uraei is stretched out on the usually curved top of the stele. Below is a figure, barefoot and clean-shaven, gesturing in supplication with one hand and holding an offering or cult object, such as a box or a sphinx, in the other. The figures are typically identified as priests, but we cannot always be certain.60 Like Yehawmilk, most wear Persian ceremonial robes and cylindrical hats (Figure 33, left).61 One well-preserved stele shows instead a figure in a different costume, a long himation with sleeves that hit at the elbow and a soft, rounded head covering secured with a band that scholars call the kausia (Figure 33, right).62 It is inscribed:

Figure 33. Stelai from Umm el-‘Amed, 3rd or 2nd c. Left: Stele of Ba‘alyaton. Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek 1835. Limestone. Ht. ca. 1.81 m. Photo: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen/Ole Haupt. Right: Stele of Ba‘alshamar. Beirut, National Museum 2072. Limestone. Ht. 1.27 m. Photo: author’s own.

ʾš ṭnʾ lʾb ʾš ly ʿbdʾsr rb šʿrm

To Ba‘alshamar chief of the gate, son of ‘Abdosir, a commemoration which has been set up for his father ‘Abdosir, chief of the gate.63

The recipient, Ba‘alshamar son of ‘Abdosir, might be related to the same ‘Abdosir who is represented by the kilt statue.

The well-preserved female stelai follow the same format, usually rounded with a winged disk outstretched over a worshipper in similar pose (Figure 34).64 In their case, however, the figures consistently wear what appears to be Greek ritual attire, the chiton and himation. Stylistically some these reliefs look more Greek in the softer treatment of the face, hair, and drapery folds. The example on the left shows the himation worn over the head. On the stele at right, an attempt is made to carve the himation’s folds tightly across the figure’s right-hand side. The stelai show that some of the types seen in votive terracottas, such as those from the Kharayeb votive deposit, were becoming desirable in monumental art as well.65 By comparison, most of the male figures’ drapery is somewhat stiff. The body positions in both males and females can be awkward as well.

Figure 34. Stelai from Umm el-‘Amed, 3rd or 2nd c. Left: Beirut, National Museum 2071. Limestone. Ht. 1.62 m. Right: Beirut, National Museum 2075. Limestone. Ht. 1.21 m. Photos: Jessica Nitschke.

Umm el-‘Amed offers further proof that selective use of Levantine, Egyptian, Greek, and Achaemenid imagery was a way that at least some Phoenicians represented themselves to themselves. Again we see that these combinations cannot be divided neatly into successive episodes of Egyptian, Achaemenid, and Greek acculturation. Not only are some of the Egyptian elements at this site new, such as the Ptolemaic sphinxes, it also would appear that the Persian male dress on the limestone stelai is conservative, a tradition that began in the Persian period and by the Hellenistic period had become part of Phoenician elite representation (whether or not people actually dressed this way is separate matter, however). The coexistence of these elements marks the sanctuary in general terms as Phoenician, but it seems impossible given this evidence to decide what visual elements here might signal particular civic or broader Phoenician collective identities.

Although we have such compelling evidence of contact in visual art, we lack evidence that many Greeks or Macedonians immigrated to Phoenicia in the Persian and Hellenistic eras. The earliest known Greek monumental inscription dates only to circa 200, and not many more inscriptions are known before the Roman era.66 Some Phoenicians, however, did use Greek and lived or worked in Greek cities. Their perspectives are very important for thinking about differences in self-presentation at home and abroad. For example, a bilingual inscription from the port of Athens known as the “Piraeus Inscription” describes honors for a member of the community:

[1] bym 4 lmrzḥ bšt 14 lʿm ṣdn tm bd ṣdnym bn ʾspt lʿṭr [2] ʾyt šmʿbʿl bn mgn ʾš nšʾ hgw ʿl bt ʾlm wʿl mbnt ḥṣr bt ʾlm [3] ʿṭrt ḥrṣ bdrknm 20 lmḥt k bn ʾyt ḥṣr bt ʾlm wpʿl ʾyt kl [4] ʾš ʿlty mšrt ʾyt rʿt z lktb hʾdmm ʾš nšʾm ln ʿl bt [5] ʾlm ʿlt mṣbt ḥrṣ wyṭnʾy bʿrpt bt ʾlm ʿn ʾš lknt gw [6] ʿrb ʿlt mṣbt z yšʾn bksp ʾlm bʿl ṣdn drkmnm 20 lmḥt [7] lkn ydʿ hṣdnym k ydʿ hgw lšlm ḥlpt ʾyt ʾdmm ʾš pʿl [8] mšrt ʾt pn gw [9] τὸ κοινὸν τῶν Σιδωνίων Διοπείθ(η)ν Σιδώνιον

[Phoenician] [1] On the fourth day of the marzeah, in the 14th year of the people of Sidon, it was resolved by Sidonians (ṣdnym) in assembly (ʾspt):—to crown [2] Shema‘baal, son of Mgn, who (had been) a superintendent of the community (gw) in charge of the temple and in charge of the buildings in the temple court, [3] with a gold crown worth 20 full-weight darics, because he (re)built the temple court and did all [4] that was required by him by way of service;—that the men who are our superintendents in charge of the temple should write this decision [5] on a chiseled stele, and should set it up in the portico of the temple before the eyes of men;—(and) that the community (gw) should be named [6] as guarantor. For this stele the people from Sidon shall draw 20 full-weight drachmae from the temple treasury. [7] So may the Sidonians (ṣdnym) know that the community (gw) knows how to requite the men who have rendered [8] service before the community (gw).

[Greek] [1] The community of Sidonians (honors) [2] Diopeithes the Sidonian.67

The inscription points to a wealthy Sidonian community that was both independent of and conversant in Athenian civic matters. The Phoenician portion follows the model of Greek dedications.68 In it, the honorand is identified as one Shema‘baal son of Magon. Following a common Phoenician practice, an equivalent for his name is given in the Greek portion, Diopeithes, and the typical patronym is dropped in favor of the Greek ethnic.69 No god is mentioned outright, though scholars assume that Ba‘al, as the chief god of Sidon, is the intended recipient. It is not clear whether the temple in the inscription was in Attika or Sidon itself. Either way, the ties between this community (gw, koinon) to the Phoenician city-state are represented as ongoing. “Sidon” and its cognates appear here six times. In the Phoenician portion, Sidon is used to date the inscription (“in the 14th year of the people of Sidon”) and to specify the group (“the Sidonians in assembly”). In the Greek portion it is again used to describe the group and as a personal ethnic (“Diopeithes the Sidonian”).

The dating strategy in the inscription underscores the difficulties laid out in the beginning of this section about correlating even detailed Phoenician inscriptions with historical events. Although the formula is found also at Umm el-‘Amed,70 the meaning of bšt 14 lʿm ṣdn on the Piraeus Inscription has generated a lot of different interpretations. Edward Lipiński and other specialists assure us that the Greek inscription dates to the third century on paleographic grounds. Indeed “year one” of Sidon cannot be any later because of the monetary terms mentioned, Persian darics, whose use did not continue past the first quarter of the third century.71 Year one is sometimes counted from Alexander’s conquests in 333/2 or from the appointment of Alexander’s supposed client king, Abdalonymos.72 Lipiński points out that the inscription does not mention a king of Sidon, and he accordingly prefers to associate year one with the beginning of the Seleukid era in 312/11. Because we know hardly anything about the political organization of the Phoenician city-states in this or any period, including exactly how long the monarchies of different city-states were left in place, this is speculation.73 Whatever moment is marked by “year one,” it testifies to the existence of Sidonian collective identity in what was probably a very confused period.

Attika provides other examples of Phoenician self-presentation abroad. One especially rich example is a funerary stele from the Athenian Kerameikos that has recently been carefully studied by Jennifer Stager and again by Olga Tribulato.74 The stele has three inscriptions, Greek and Phoenician epitaphs followed by a longer Greek epigram. It probably dates to the early third century.75 In the epitaphs we learn the Greek and Phoenician names of the deceased and the man who paid for the stele:

Ἀντίπατρος Ἀφροδισίου Ἀσκαλ [ωνίτης]

Δομσαλὼς Δομανὼ Σιδώνιος ἀνέθηκε

ʾnk šm . bn ʿbdʿštrt ʾšqlny

ʾš yṭnʾt ʾnk dʿmṣlḥ bn dʿmḥnʾ ṣdny

[Greek] Antipatros, son of Aphrodisios, the Ashkel(onite)

Domsalōs, son of Domanō, the Sidonian, dedicated (this stele)

[Phoenician] I Shem . son of ‘Abdaštart the Ashkelon(ite)

(This is the stele) which I, Domseleh, son of Domhano the Sidonian set up.76

Here we see a juxtaposition of onomastic strategies, one opting for translation in Greek (Antipatros/Shem) and the other transliteration (Domsalōs/Domseleh). As Stager and Tribulato argue, these practices suggest degrees of linguistic and cultural bilingualism. The “cultural duality” of the deceased, Antipatros/Shem, is greater by comparison with his friend Domseleh.77

The accompanying imagery shows the deceased on a bier being attacked by a lion, which is, in turn, energetically repelled by a male figure in front of ship’s prow and naval standard. Stager argues persuasively that what we see here is a Phoenician funerary practice executed in Athenian style. The epigram goes some way to spelling out what is seen to Greek speakers but does not explain its full meaning. Tribulato argues that its hapax legomena, rather than its grammatical mistakes, are a key to understanding that a Phoenician, presumably Domseleh, closely supervised the language of the epigram.78 The stele’s imagery addressed two audiences, an Athenian one that might have had particular reactions to the male figure fighting a lion, and a Phoenician one that would understand its visual language differently. Stager argues that a Phoenician observer would have associated a lion and ship’s prow with astral navigation, Phoenician maritime religion, and Antipatros/Shem’s home city of Ashkelon.79

The compelling final line of the epigram reads:

Φοινίκην δ᾽ ἔλιπον τεῖδε χθονὶ σῶμα κέκρυνμαι

I left Phoenicia and I am, in body, here hidden in the earth.80

There are only half a dozen instances in which phoinix and its cognates appear in Greek-language inscriptions.81 On the Kerameikos stele’s epigram, “Phoenicia” is being substituted for the specific Ashkelonite and Sidonian identities in the epitaph. Stager argues that Phoenicia means something that was both different from and broader than a civic identity. Because the epigram and the epitaph are written in different hands, the epigram could have been part of the original dedication by Domseleh or it could have been added later. Accordingly, we cannot know if this Phoenicianism was internally expressed or externally imposed. But even without the epigram, the epitaphs and the image show a collectivity that coexisted with distinct civic identities—Ashkelon and Sidon are distinct and related, as are the Greek and Phoenician languages and the imagery on the stele.

The use of the Phoenician language, an important choice in this context, privileges a Phoenician audience while showing command of Greek and knowledge of an Athenian type of monument, as does the imagery despite its Athenian style. This last point is very important to the way that we react to Greek style or imagery in other contexts, such as the Eshmun sanctuary in the patron Domseleh’s home city. In fact, Stager and Tribulato disagree on how to interpret this monument’s aggregations, if they indicate that Antipatros/Shem died at sea en route to Athens (Stager’s view) or are proof that he lived in Athens (Tribulato’s view). Their close studies show how much we have to gain from taking the Phoenician components of such objects seriously. The Kerameikos and Piraeus inscriptions are representative of the Phoenician inscriptions in Attika, Thebes, and Corinth as a whole, which balance different degrees of bilingualism, civic heterogeneity, and Phoenician community.82

A few preliminary points can be drawn from this evidence. First, to get to the most obvious one, phoinix and its cognates are rare in the Greek epigraphic record. Explicit claims to be “a Phoenician” in Greek literature are more rare still. In Achilles Tatius’s second-century CE romance, the character Klitophōn identifies himself as a Phoenician from Tyre (1.3.1):

ἐμοὶ Φοινίκη γένος, Τύρος ἡ πατρίς, ὄνομα Κλειτοφῶν, πατὴρ Ἱππίας, ἀδελφὸς πατρὸς Σώστρατος

I am a Phoenician, my homeland is Tyre; my name is Klitophōn, my father is called Hippias, my uncle Sōstratos.83

Hints of self-adoption of phoinix are found elsewhere in the imperial period, in Herennius Philo of Byblos’s so-called Phoenician History, which was written in Greek in the second century CE, and the aforementioned single line of Heliodoros’s Aithiopika (10.41.4).84 There are more examples, which together speak to new, revived, or increasing interest in Phoenician identity in the imperial period,85 an interest that, however compelling, cannot be read as entirely emic or ethnic and cannot be pushed retroactively into the first millennium BCE. Just as important is the parallel evidence of the persistence of strong civic identities, some of which, such as the Piraeus Inscription, show no indication whatsoever of a broader Phoenicianism.

While iconography such as the disk and uraei was in use in the coastal Levant from the Bronze Age into the second half of the first millennium, what we see beginning in the Persian period are classes of monumental objects that are particular to Phoenicians. We also find in Phoenicia combinations of styles, iconographies, and types that are not found elsewhere, as Umm el-‘Amed and the Eshmun complex at Bostan esh-Sheik demonstrate. Most often the Greek and Phoenician points of contact are emphasized, such as the combination of Aštart throne and Greek altar, but that is only one small part of what was happening even in the Eshmun complex. Greek style was not a feature of the ‘Amrit sanctuary or even a factor in the limited evidence we have from Byblos. Instead we see evidence of various responses to tradition and to new contacts with different results. We should not necessarily conclude, however, that the city-state was the “chief horizon of identity”86 for the people we call Phoenicians. Hints of Phoenicianism are found in theophoric names that cannot be assigned to specific city-states, in anthropoid sarcophagi from multiple locations, and, in more general terms, in the approach to sacred spaces. Phoenicianism is explicit in the Kerameikos inscription that brings together Sidonian and Ashkelonite.

The earliest known Mediterranean coins come from late seventh- or early sixth-century western Asia Minor. Although the impetus for the invention of coinage is debated, early coins had very limited circulation, suggesting local needs were being met.87 The first coins to circulate more widely were minted in the silver-rich regions of Thrace and Macedon in the late sixth century. Aegina was the first Greek polis to mint, beginning in the mid-sixth century. These issues were not much to look at, “dumpy pieces with a turtle” on the obverse, and a crossed-line punch on the reverse.88 Yet even crude decorative schemes served as visual reminders of a coin’s value and issuing authority. Aeginitan turtles were the first coins to circulate in the Near East. Shortly after the full exploitation of the silver mines at Laureion began in 483,89 they were eclipsed in popularity by the Athenian silver tetradrachm—the Athenian owl—an overtly civic coin evoked in this choral passage from Aristophanes’s Birds:

γλαῦκες ὑμᾶς οὔποτ᾽ ἐπιλείψουσι Λαυρειωτικαί,

ἀλλ᾽ ἐνοικήσουσιν ἔνδον, ἔν τε τοῖς βαλλαντίοις

ἐννεοττεύσουσι κἀκλέψουσι μικρὰ κέρματα

Never shall the Lauriotic owls from you depart,

But shall in your houses dwell, and in your purses too

Nestle close, and hatch a brood of little coins for you.90

The owl spread throughout the eastern Mediterranean, becoming synonymous with coinage itself. It was widely imitated.91

The coin’s design is both elegant and straightforward (see Plate 14). On the obverse is the helmeted head of Athena, facing right. Beginning with the Classical issues (from post ca. 480–475) she is also laureate, surely to celebrate the victory over Xerxes, and a floral scroll is added to her helmet. On the reverse is Athena’s owl, standing with the body facing right, face front, large eyes upon the beholder.92 Athena’s olive branch is in the field over the back of the bird; a small crescent moon is between them, the latter another feature added in the Classical era. To the right of the owl is the legend with the polis ethnic AΘE for Athēnaiōn, “of the Athenians.” These elements are found on Athenian silver coinage, with some interruptions and many small die variations, until the mid-third century BCE. The style is kept Archaic deliberately, moving in small stages from the profile eye, to the three-quarter eye, to the early fourth century, when Athena’s naturalistic makeover was complete, her eye rendered in profile and her Archaic smile softened.

While Athena shows up on the coins of many states, this combination of Athena plus her owl points clearly to the city that bears her name and to their shared military strength and wisdom.93 The coins were minted throughout the fifth century (fewer in the first few decades after the wars) as Athens expanded its empire and brought the Delian League treasury home. Eventually Athens demanded use of its coinage by her subject-allies.94 Whereas major civic structures such as the Parthenon defined the Athenian identity at home for an audience composed of citizens, metics, and visitors, the Athenian tetradrachm distilled essential features of the state over incredible distances, declaring the stability and power of Athens as guaranteed by its patron deity and the remarkable purity of its coins.95

Although there is ongoing debate about the extent to which users paid attention to coin imagery, it is clear from imitation owls minted elsewhere that people at a remove from Athens understood the Athenian owl as the eastern Mediterranean’s primary coinage and an important commercial tool. It remains to be explored how much the coins projected a particular Athenian or even Hellenic identity and to whom. No mainland Phoenician cities imitated the owls directly. One reason for not doing so was practical, as imitations upset the confidence in a coin’s value.96 There is a time lag between the popularity of coinage in Greek poleis and the minting of coinage in Phoenicia and Egypt, one that has contributed to the idea that the minting of coins is symptomatic of Hellenization. There is no real support for this view. As Jigoulov points out in his brief review of the state of the field, Phoenician numismatics began as an offshoot of Greek numismatics. Only very recently has the study of Phoenician coins become a field in its own right, meaning that the approach to the topic is still Hellenocentric or in the early stages of reacting against Hellenocentrism.97 For this reason the discussion below concerning imagery is detailed, though not comprehensive. The goal is to emphasize the great extent to which the coinage of the Phoenician city-states from its inception operated with a visual logic all its own, a pattern that has been established already in the preceding discussion of monumental art and inscriptions. Like monumental stone sculpture, the coins’ standards and imagery are evidence of the independence of and competitive relationship between city-states that coexisted with elements of connectivity.

The fact remains that the Achaemenid Empire adopted coinage second hand from Lydia, just as Greek states did (Hdt. 1.94.1; see Map 4). The main mint seems to have been at Sardis. The first coins were lion and bull Croesus staters (“Croeseids”) minted after 546.98 Although the date of the introduction of the Achaemenid gold darics and silver sigloi (shekels) is debated, there is good evidence they were first minted by Darius I in the last decade of the sixth century as part of his major economic reforms.99 It is quite likely that payment for naval service, for the building and manning of ships, was an important motivation.100 The move to coinage in Phoenicia—where Persian coins hardly circulated, according to our available evidence101—was probably similarly motivated but must be understood also in the context of the increasingly important role of coins, Athenian owls chief among them, in eastern Mediterranean commerce.

Just before the middle of the fifth century, in the midst of ongoing conflict with Athens and perhaps owing to a dip in the production of and access to owls after 480,102 the four major Phoenician city-states begin minting coins. The traditional view is that the first city to mint was Byblos in circa 460, followed in succession by Tyre, Sidon, and Arwad (Figures 35–36, Plate 15).103 Probably the first silvers were made by melting down Greek coins, thus transferring the added value of the coin—on top of its raw material—to the Phoenician states.104 It appears that these coins did not circulate widely before the fourth century, although our understanding of their use is meager owing to limited publication of coins from controlled excavations. Their impetus is debated, sometimes attributed to a desire to participate in the coinage economy. No hoards of Phoenician coins have been found in Hellas, however.105 Beyond Arwad, which minted Persian-standard sigloi and staters, the main denominations of these coins deliberately but not exclusively employed an independent standard, what we call the “Phoenician standard,” tied to a silver stater or shekel of circa 13.9 grams that was divided into many smaller values.106

As Colin Kraay has argued for Athenian coins, the relatively large silvers were probably not minted for use in local markets, even though their circulation was initially rather limited. Kraay argued payments made to and by the state were the motivation for minting, although it must be emphasized that the minting of coins for such a purpose presupposes that both the state and its members would find coinage useful. Clearly the question of the origin of Phoenician coins is complex, though I favor the idea of internal factors brought about by external events. Beginning in the late sixth or early fifth century, Darius’s aforementioned reorganization of the Achaemenid Empire promoted changes in civic structures throughout Phoenicia. Accompanying these changes were new financial and tax systems and, critically, coin payment for military and naval service.107 Many of the very same conditions leading to the creation of Athenian owls were shared by the Achaemenids and Phoenicians, which led to their decision or ability to mint self-promoting coins. Even in Anatolia the importance of coinage grew under Achaemenid rule.108

Leslie Kurke has made an eloquent argument that Athenian coins were valued for what she calls essential and functional/symbolic factors. She places emphasis on the Athenians’ near-exclusive use of silver, a metal she associates with the middling identity and the polis in contrast to the golden ideology of elites.109 The primary use of silver for Phoenician coinage deserves attention, too. It is doubtful the Achaemenids would have allowed Phoenicians to mint in gold, and it is likely that the Phoenician states would not have had much use for such high-denomination coins. Achaemenid darics were informally called toxotai, or “archers,” by Greeks owing to their standard iconography of a striding figure in a long robe and crown carrying a bow and sometimes other weapons (as Plut. Artax. 20.4, Ages. 15.6). They were minted in a very pure (98 percent) gold.110 Greek sources suggest the idea of gold coinage was virtually synonymous with darics, which was one more reason Greeks associated gold with the East.111

Following on this idea and Kurke’s line of thinking, it is possible to infer ways that the materiality of Phoenician coinage was perceived in ideological terms. The use of silver for the highest denominations could have articulated the difference between Sidon and Tyre and their suzerain even while both of these cities employed some Achaemenid imagery on their coins (discussed below). The fact that most Phoenician city-states did not adopt the Persian silver denomination, the siglos, adds to the idea that these choices were in part ideological. Although their motivations were different from those of Athenians, Phoenicians could have perceived a similar dialectic of metals, with, in this case, gold as an emblem of Persia and silver as civic and quasi-independent. I follow Kurke in concluding that the civic coins constructed and controlled value, thereby increasing the authority and power of city-states tangibly (economically) and symbolically.112 Iconography reinforces this general picture.

Skill in miniature work is plain from the coins’ execution. Gubel has shown that some of their visual content stems from glyptic arts. The contextual study of seals is made difficult by their popularity in the art market, however, and some of his broader claims regarding seals of the Persian period have been criticized accordingly.113 Recalling what we have already seen in monumental arts, it is clear that the iconography of different civic issues was developed through a local tradition in combination with the selective use of reinterpreted foreign motifs. Our understanding of what is shown is often hampered by our generally poor grasp on Phoenician religious and state symbolism. For example, the early coins of Arwad show a fish-tailed deity with a warship on the reverse.114 There is no consensus on the identity of the ichthymorphic deity, and even the meaning of the warship is not straightforward—it might be a general reference to maritime prowess or a reference to or appropriation of Sidonian or Persian iconography. In the early part of the fourth century, the iconography on silver coinage changes. Some shows bearded faces (of the ichthymorphic deity?) or sea horses (Figure 35). In circa 380–350, waves are added to the reverse with the ship, and the eye of the bearded figure gets a naturalistic makeover—that is, after Athena does on her owls—as in the example illustrated here.

The coinage of Byblos is quite different.115 The earliest issues show a sphinx wearing a double crown and a number of reverses, some of which are seemingly generic (head of a helmeted figure), others expressly Egyptian (scepter, vulture, and ram). Circa 400 the obverse iconography becomes bellicose: a galley and soldiers. Some reverses are kept, and others, such a sitting lion, are added. The lion likely represents Aštart and might be a reference to the growing power of Sidon, where her cult was long established (compare the Shem stele from Athens). Changes again occur in the beginning of the fourth century when obverses are loaded with imagery (Figure 36). They show, from top to bottom, a galley, a winged sea horse (sometimes referred to in the literature as a hippocamp), and a shell. Reverses often show a lion attacking a bull, as in the illustrated example, a long-lived image that was embraced by Achaemenids and here seems to be a deliberate reference to Persia.

Sidonian coinage is consistent on its obverse: a galley with small variations in the details, sometimes with fortifications in the background, that recalls Herodotos’s statement that Sidonians were the best of the fleet (7.96–100; Figure 37).116 Reverses are varied, but they mostly relate to imperial Achaemenid imagery. They begin with a nod to Persian coinage, an archer. The use of this motif is somewhat remarkable because, despite its wide circulation in the Western Empire, only one Persian coin has been excavated so far in Phoenicia proper, a silver from Byblos.117 Our knowledge of the circulation of darics is poor, and only about 160 examples of Persian coins are known in all of the Transeuphrates.118 Nonetheless, it is clear the imagery was familiar to Phoenician kings, and it was an important part of Sidonian (and, as we will see, Tyrian) self-representation on coinage. From circa 430, the reverse shows a chariot with driver and royal rider, which from the end of the fifth century is followed by an attendant on foot (as in Figure 37, right). The rider, sometimes interpreted as a statue, is shown in Persian ceremonial dress. As on Arwadian and Byblian coinage, inscriptions of the king appear on Sidonian coins shortly thereafter, from circa 400. In the fourth century several changes occurred, including more denominations and the reappearance of an archer figure as well as a standing lion. The coins of ‘Abdaštart I (in Greek Straton I, r. ca. 365–352) stand out in this period, as they show further standard and iconographic changes. ‘Abdaštart minted bronzes with a bearded and diademed head and a galley on the reverse. Stylistically his coins look like other Sidonian issues, but they were minted on the Attic standard. A relationship between the king and Athens is attested also by a Greek inscription from the Athenian akropolis telling how ‘Abdaštart assisted an Athenian delegation to the Persian court.119 Sidonian traders were awarded tax breaks in return.

Figure 35. Silver stater minted in Arwad, later 4th c. Obverse: bearded male; reverse: ship and Phoenician inscription. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France FRBNF41741201. Silver. 10.7 gr. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Figure 36. Silver drachma of Elpa‘al, minted in Byblos, 4th c. Obverse: galley with soldiers, winged sea horse, shell; reverse: lion attacking bull. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France FRBNF41741215. Silver. 2.92 gr. Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Figure 37. Silver coin of Ba‘alshillem II, minted in Sidon. Obverse: ship; reverse: chariot carrying a royal figure followed by attendant, late 5th or earlier 4th c. London, British Museum 1918,0204.157. Silver. 28.3 gr. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Some see this coinage as evidence of Sidon’s increasing resistance to Achaemenid rule. It is important to this argument that Abdaštart’s successor, Tennes, openly rebelled against Persia.120 In Diodoros’s account of the so-called Tennes Rebellion of circa 350, Sidon is presented as instigator, but other city-states seem to be involved, too. Tyre and Arwad are implied participants.121 It is in this period that Sidonian and Tyrian standards are closest, a move that might have been meant to reinforce political unity.122 A parallel situation is found in Anatolia, where in the fourth century silver sigloi production slows and is replaced by different satrapal issues, including those with tiarate heads on the obverse. Elspeth Dusinberre has argued against this change as evidence of growing independence, however, because the tiara headgear shown on the coins is the same as what Persians wore into battle. Thus this type and other new issues functioned in a symbolic fashion that fit the original sigloi, even while the iconography changed and the style of their execution became Greek.123 In both cases, we have good evidence that standards and imagery were meaningful to the issuing kings, Persian imagery most of all.124 Sidon’s Persian-looking coins have been downplayed in most treatments of Phoenician art of this period, a consequence of the desire to see Sidon as leading the way in Phoenicia’s Hellenization. In fact, Arwad is the only city-state to produce coinage that responds to the style of Greek art, and only Tyre’s coins have iconographic similarities.

Tyre’s popular owl reverses are found on seven different Persian-period series (see Plate 15).125 The earliest Tyrian coins were minted with a variety of themes on their obverse: a dolphin over waves and a shell or a bearded figure on a winged sea horse flying over waves and also above a shell or dolphin (see Plate 15, top). Although we lack independent corroboration of his appearance in this period, the bearded figure is usually identified as Melqart, under the assumption that pride of place on Tyrian coinage belongs to the city god. The Melqart bowman becomes the standard imagery of Tyrian obverses in the fourth century. The winged sea horse, like the one on Byblian coinage, seems to stem from Phoenician seal imagery,126 while the pose of the bearded figure is derived from the Persian archer motif.127 Like the Persian archer, the Tyrian one holds a bow in his left hand. His costume is different, however, and he does not wear a crown. Instead of holding attributes in his right hand, the Tyrian figure holds the reins of his sea horse. As Nitschke has shown, the similarities and differences are both important to the presentation of Tyrian identity. Whereas the Persian archer shows the empire’s dominance over the land, the Melqart figure on his flying sea horse rules over the sea.128

It is in this context that we must turn to the owl reverses and their relationship with the Mediterranean’s dominant coinage. Like its Athenian counterpart, the Tyrian owl stands with its body usually to the right and its head facing front, looking out at the viewer. Both owls have their left foot in front of their right. Both have dots (sometimes lines) on their bodies to indicate mottled feathers, leaving the wings and tail feathers smooth. But that is where the similarities end. Whereas the Classical Athenian owl seen in Plate 14 is Archaizing, the Tyrian owl is just as clearly derived from an Egyptian prototype.129 In the fifth century, the Tyrian owl has a compact body and a long and wide wing that stretches from breast to back; a small head; a strong brow line plunging into the beak; squared tail feathers of equal length that descend all the way to the ground; and ear tufts.130 Many of these features are found also in the owl hieroglyph, the sure source of the Tyrian image (compare the many owl hieroglyphs on the Tabnit sarcophagus seen in Figure 21, right). Key similarities include the pose, shape of the body and tail, and emphasis on the V-shaped brow.131 Along with the owl on the coin’s reverse are the crook and the flail, symbols of Egyptian divinity and kingship. These attributes are arranged behind the owl’s body from upper left to lower right so that the owl is in chiastic superimposition.

Just because it is clear that these motifs were appropriated from Egypt, we should not forget to ask why. Why an owl, and why the crook and flail? Owls are not mentioned in any Phoenician inscriptions, and they hardly appear in Phoenician art before they become a standard image on these early Tyrian coins. They do not make frequent appearances afterward.132 It is possible that the owl had an apotropaic or magical role in Tyrian funerary rites, but the evidence is thin.133 While apotropaic imagery is known on coins, probably this is not the right connection in this case. The crook and the flail are curious, too. In Egyptian hieroglyphs, neither is shown together with the owl. When paired in art, they are usually held one in each hand, arranged in a chiastic or “V” shape. Examples can be found in funerary imagery of pharaohs and Osiris.134 When the crook and flail are aligned, as on the coins, it is because they are held in one hand. Examples include some images of Anubis, pharaohs, and Horus the Child.135 The flail also appears in chiastic juxtaposition with two common bird hieroglyphs, the vulture and the falcon. The falcon seems to be the link with Phoenician art. On seals thought to be of Phoenician manufacture, the crook and flail are attributes of Egyptian-type hawks or falcons in an arrangement similar to that on the Tyrian coins (see Plate 16).136 What we see on the coins are two elements of Egyptian visual art that are combined for the first and only time. The arrangement may have meant to evoke images of the Horus/falcon-flail hieroglyphs that seem to be the progenitors also of the seal imagery seen here.

The Tyrian owl image is equal parts appropriation and innovation, like the Melqart archer on a sea horse with which it was often paired. Both images show Tyre’s authority through their respective appropriation of Egyptian and Achaemenid symbols of leadership. Yet the particular choice of the Egyptian owl can only be explained in terms of Athenian owls.137 Rather than imitating or appropriating Athena’s owl as one might expect, the Tyrian owl is deliberately rejecting its visual qualities in favor of Phoenician ones. With its prominent ear tufts, small head, and particular body, the Tyrian owl even seems to be interested in representing a different species.138 As a construct of the Tyrian state, the owl issues are very sophisticated. At once they stake a claim to the growing coin-based economy, negotiate with three major powers through their own symbols of authority, and produce something unique—something Tyrian. The Tyrian owls appear as late as 275. The consistency of the imagery made them “more easily recognisable within and without the minting city.”139 Possibly the predatory owl was as synonymous with Tyre as the Melqart archer. Unlike the winged sea horse, shell, and dolphin, the owl is never found on the coins of other states.

The general message of the various Phoenician coins is clear enough. Power is expressed in economic, religious, and political terms by appropriating, recombining, and generating iconography. While there is evidence that golden archers were synonymous with Persia, we have less evidence about what Athenian owls signaled to users. Were they seen specifically as Athenian? Or were they read as Greek? The Athenian owls quite deliberately construct an identity for their city: the owl is Athena, and Athena is Athens. It would be a mistake to argue against the coins’ political particularity. It would be a further mistake to think that Phoenicians were incapable of understanding at least some of what the coins were trying to say. As the Tyrian owls ably demonstrate, the Athenian owl was seen as a major symbol of power. Changes to the owl—its species, attributes, and style—underscore an awareness that all of these visual components were significant.

Athenians were well known by Tyrians in the era of the coins’ emergence, as Athens was the main power in the Greek navy that opposed the combined Phoenician forces. Sidon, Tyre, and Arwad all contributed ships in service of Persia.140 At the same time, we should acknowledge that direct contact between Athenians and the Phoenician fleet did not inspire Greeks to discuss Phoenicians in a careful way. We must accept the possibility that Phoenicians showed the same degree of uninterest in Greeks or the parallel tendency to conflate a city-state with a larger collective, a point of view perhaps encouraged by the formation of the Delian League in 478. Further, the ubiquity of the Athenian owls might support the idea that, however particular their visual properties, they had superseded the scale of their particular minting polis.

Nonetheless, it seems plausible that the Athenian owls projected Athenian identity in Phoenicia, but there is no way to know the extent to which “Athenian” also meant “Greek” there. The identities associated with Tyrian coins, and Phoenician coins as a class of objects, are still more difficult to recover. Here again we will find reasons to argue for and against art’s expression of collective identity on a level exceeding the state. There is no reason to think that Phoenician coinage began as part of a unified effort, just as it is unlikely that the Phoenician fleet began as any sort of collective force. From our admittedly imperfect evidence, it appears that the major mints started up at different times, beginning, paradoxically, with the weakest of the four city-states, Byblos. These mints were not operating at the behest of Persia, as most employed their own standards and all clearly had free rein to choose their iconography. Further, no city-states minted coins identical in terms of their design.

Yet there are points of connectivity. Some coins share iconographic elements, such as the shell or the sea horse; they are made in silver or bronze but never gold; and they circulated primarily within Phoenicia. Importantly, Byblos, Sidon, and Tyre make an effort in this period to employ a similar weight standard, the aforementioned Phoenician standard, for some issues. In the mid-fourth century, it was employed also in Carthage.141 This standard not only set the Phoenician economic system apart from that of the Greeks and the Persians, it also distinguished Phoenicia from its closer neighbors, some of which, like Judah, had a special status within the Achaemenid Empire (Neh 5:15–18).142 The coins may be a rare statement of Phoenician political, or at least economic, unity that persists for some seventy years.

To conclude, we may reconsider what is at stake in the idea of an emerging Phoenician collective identity and what conditions might have shaped it. It is important to situate this discussion in the very small scale of mainland Phoenicia (see Maps 1, 3, and 4). From what can be determined, cities were small and surely densely populated: bigger city-states, such as Arwad and Sidon, are estimated to have measured between forty and sixty hectares at their largest extent; Beirut and Sarepta were considerably smaller. Even Tyre may have measured no more than sixteen hectares in its urban core.143 The distance between the two mainland mints at farthest remove—Tyre and Arwad—is only about two hundred kilometers. Tyre and Sidon are separated by about fifty kilometers, Sidon and Beirut by a mere forty or so. Corinth and Athens, by contrast, are about eighty-five kilometers apart; Athens and Delphi are separated by about 175 kilometers, Sparta and Delphi by some 320 kilometers (overland). While there is disagreement about how they developed, the Phoenician language and writing system suggest easy communication between different city-states. Moreover, members of these maritime cities were on the move and frequently traded with one another. These factors—scale, trade, mobility, and communication—mean that it is quite possible a collective Phoenician identity existed at some points in the Iron Age, even if we lack much evidence to support it.

All the same, the events of the late sixth and fifth centuries had a major impact on Phoenicia and the entire eastern Mediterranean. The incorporation of the Levant into the Achaemenid Empire drove many of these events. Major Phoenician city-states began fighting alongside one another in opposition to Greek forces at the 494 battle of Ladē. The Eshmunazar sarcophagus suggests that this type of service sometimes had handsome rewards, certainly among the main protagonists on the Phoenician side, the neighboring states of Sidon and Tyre. The anecdote regarding Carthage recorded in Herodotos might be a Greek projection, but legends on Hellenistic bronzes of Sidon and Tyre demonstrate the continuity of their close, yet very competitive, relationship. While second-century Sidonian coins were inscribed “Sidon, mother of Carthage, Hippo, Kition, and Tyre” (cf. Just. Epit. 18.3.5), contemporary Tyrian coins proclaimed that Tyre was the “mother of the Sidonians.”144 In these legends we see a deliberate doubling of meaning, a proclamation of one state’s superiority over her neighbor(s), notably her greatest regional rival, in Hellenic terms, a strategy that has echoes in the bilingual inscriptions from Athens and, more explicitly, in Persian-period Tyrian coinage.

In fact, Tyre was the state that most often expressed its Phoenicianism in the long run, even after it became a free port in 126 BCE. As late as the third century CE, Tyre minted coins showing Kadmos handing the Greeks their alphabet145 as well as coins commemorating the founding of Carthage.146 This evidence might suggest that Phoenician identity got stronger as the second half of the first millennium unfolded, reaching its acme in the first and second centuries CE, a phenomenon that can be compared to Michael Scott’s argument concerning the late development of Panhellenism.147 But, as I said previously regarding the self-ascription of phoinix, we cannot read these tantalizing late examples back onto the fifth century. Any attempt to plot a clear trajectory of Phoenician art or culture and identity is mired in unknowns.

Nevertheless, we can observe how the city-states’ coins show a remarkable degree of economic independence from their suzerain.148 Here, as in Egypt, the Persians seem to have ruled with “as light a hand as possible” and with better results.149 As a class of objects, the coins promote the viability of the Phoenician economic system versus an Athenian (or Greek or any other) one through the deployment of the Phoenician standard and particular motives. The imagery on the coins guaranteed their value not only to and among members of individual Phoenician city-states but also to those with whom they traded. Circulation of this imagery within the city-state was not restricted to elites, a point that has been underplayed in Phoenician numismatics. I believe that Phoenician coin production is further evidence of group consciousness emerging through a type of peer-polity interaction,150 the conditions for which were created in the period from the rise of the Achaemenid Empire to the Persian Wars and their aftermath. As we have seen, Phoenicia has many characteristics of this model. It was composed of small city-states—polities of comparable scale—in the same region that, because of Achaemenid political and economic policies, experienced simultaneous organizational change. Interaction within and among polities led to competitive innovation.

It is not, of course, strictly necessary to frame these events in terms of peer-polity interaction. Nor is it advisable to forget that texts figure heavily in similar arguments made on the Greek side of things. Miller has shown, however, that even in Athens, a vociferous opponent of Persia, interest in “Perserie” was widespread in the fifth century.151 Furthermore, “oppositional” thinking is not found in Herodotos. As I stressed in the previous chapter, we should be critical of the idea that Greeks considered themselves a national group in any period and must be open to challenging the Greek/anti-Greek approach so often associated with the Persian Wars and their aftermath.152 Hellenism, like Phoenicianism, is still mostly a modern construct.153 The point remains, however, that we have some evidence in the fifth century of collective “Phoenician” action. Coinage focuses our attention on artistic products we can confidently assign to specific groups, an opportunity as rare in Levantine portable art as it is commonplace in Athenian art. It follows that the Persian Wars could have shaped Phoenician as well as Greek collective identity, even while we recognize that these events had greater political and economic impact on some city-states, such as Athens, Tyre, and Sidon, than on others. When Sidon and some other Phoenician states moved their coinage to the Attic standard for a time in the fourth century, their motivations are unclear.154 Possibly different uses of the Attic standard, however short lived, signaled movement away from Persia. Whatever its impetus, the move serves to underscore the collective (although not universal) decision to otherwise use an independent standard.

The new political and economic realities of the Persian period had a major impact on trade that goes some way to explaining why more Greek elements appear in Phoenician art at this time and why there is altogether more Phoenician monumental art in the archaeological record, some of which was made in imported basalt or marble. It is popular to think that, by this time, mainland Phoenicians did not dominate the western Mediterranean. That role was increasingly assumed by Carthage where the increase of population and prosperity is well attested in the archaeological record.155 Mainland and southern Phoenician traders were thereby limited to the eastern Mediterranean, bringing them in ever-closer contact and competition with Cypriot and Greek merchants.156 Peter van Alfen has conducted a thorough study of Mediterranean commodities, in which he suggests that the Persian-Greek rivalry was a key factor affecting trade. He argues that trade in strategic goods—timber, pitch, and agricultural products—may have been restricted by both Persians and Greeks for obvious political reasons.