It is a basic premise of this book that contact can make critical contributions to the expression of identity in art, whether interaction is in the form of armed conflict or trade, cooperation, competition, artistic migration, emulation, or from elsewhere. Yet it is clear that the idea of “interaction” itself is tangled up in the problematic way that we divide what we call Greece from the Near East. While it is convenient and justifiable to separate what we study geographically or chronologically, the last chapter demonstrated that it is more problematic to present Greece and the Near East, or Greek, Egyptian, and Phoenician art, as fundamentally different. We have seen that qualities most often associated with Greek art in the later Archaic period and beyond—its superior execution, innovation, naturalism, and so forth—are openly chauvinistic. One result is that much other Mediterranean art thought to be of comparable excellence is understood as the product of Greek artists or the imitation of Greek art. Works such as picture mosaics or the Sidonian relief sarcophagi (see Chapter 5) attract attention from classical art historians who engage in a discourse largely uninterested in Near Eastern arts, a discourse that presents these works as a part of Greek art history and perpetuates stereotypes of each tradition. This way of thinking is so deeply entrenched that “one does not have to be an advocate of [the] particular theory in order to propagate it.”1 Belief in the idea of fundamental difference between Greece and “the East” is implicit in Orientalizing and Hellenization. The terms imply temporally bounded interactions of otherwise discrete traditions. For this and many other reasons Orientalizing and Hellenization are really quite easy to criticize, even while they continue to have a solid grip on scholarship.

One major hurdle is a reluctance to give up on the idea of “East and West” language that continuously reifies and reaffirms the very problematic points of view most scholarship ostensibly wishes to overcome.2 Of course, comparative studies of broad geographical scope will always lack the refinement we might find elsewhere, in, say, the history of specific persons (biography, agency, or cognitive archaeology), individual monuments, or even a single city. But the problem is not only one of scale or particular terminology. Rather, generalization is a constant threat in comparative studies because, just like “West” and “East,” “Greeks” and “Phoenicians” are arbitrary categories. They are ideal, not real, entities, imagined communities of modern scholarship most of all.3 Ideas about “the Greeks” and “the Phoenicians” were and are malleable, contextually based, and subject to regional, disciplinary, and temporal variation. Further, the people we call Greeks in the first millennium BCE did not always conceive of themselves as a collective, and, even when they did, Hellenism in the sense of “behaving like a Greek” was only occasionally the most important part of their identity.4 The idea of a culturally defined Hellenism is as stubbornly vague as it is commonly held.

A still greater challenge is that we have trouble recovering information that might tell us what—or if—Phoenicians thought of Greeks or of themselves as a collectivity.5 So before we turn to the rise and expression of Phoenician collective identity in the following chapter, the way scholars use evidence to define and interpret these groups must first be explored in this one, in order to think about how we came to create Greek and Phoenician collectivities and assign to them artistic traditions. We will do so by following through on the problems raised in the previous chapter concerning the limitations and abilities of art to signal collective identity. In thinking through how scholarship has drawn identity on a large scale to arrive at the ideas of “Greeks” and “Phoenicians,” I will show how tacit attachment to essentialism—race, most of all—encourages us to resist changing our fundamental ideas about identity. The final step is to show how we have come to apply these labels to art. I argue that while it is possible to rely on textual evidence to understand Greeks and Greek art, the very ideas of Phoenicians and Phoenician art are problematic.

From Hesiod (especially at the end of the Theogony) to Herodotos and the Hellenistic geographers we learn that first-millennium Greek texts were interested in the makeup of different groups and that non-Hellenes were always an important part of the oikoumenē. Even so, Hellenes were deeply self-interested, meaning the roles played by others in their self-perceptions were usually peripheral.6 By contrast, Phoenician histories that date before the Roman era are lacking, leaving us with no narrative to guide our understanding of their attitudes about identity or reactions to the events of the first millennium.7 We must be content to work primarily with the rich Greek sources, both written and visual, while the Phoenician reaction can be sought in its artistic output and corpus of inscriptions. These sources indicate that the first half of the first millennium was marked by periodic connectivity and receptivity among eastern Mediterranean elites, suggesting that aristocratic mores and aspirations were driving forces encouraging contact and the expression of group identity. Identity transgressed some of the limits of geography, as made clear in gift exchange, the spread of the Lyre-Player Group seals, and perhaps also in social phenomena, such as the Greek adoption of the Phoenician alphabet.

The “Phoenicians” whom Greeks encountered would not have been members of the princely class, however, as the scattered Greek evidence assures us. Given this testimony and what we can infer from the archaeological record, it is likely that mobile Phoenicians were artisans, traders, merchants, and sailors.8 Possibly even literacy was transferred via this group.9 These transnational developments connected some members of Greek, Phoenician, and other societies while, at the same time, leading to deep structural changes in Hellas. Ethnic distinctiveness seems to have played an increasingly important role in the formation of the political communities that gave rise to and solidified the city-state.10 Precisely when or if we can pinpoint transpolitical or common Greek or Phoenician identities is debatable.11

Some see colonization as an important catalyst for Hellenism. Most scholarship agrees that Greek self-awareness was cemented in, or at least was developed by, its confrontation with the Persians. This idea is deeply rooted in our understanding of the Classical era, specifically, and Greek history in general.12 The Persian Wars, it is said, mark the recognition of the fundamental (cultural? ethnic? racial?) difference between Greeks and Near Eastern peoples, which in turn made various Greeks aware of their similarities. From this point, the complex idea of the supraethnic, culturally defined Hellene emerged.13 According to this way of thinking, it was on the field of Marathon that exceptional Hellenism really took shape. The idea is too neat and has been rightly criticized. But there is no disputing the importance of the Persian Wars to Greek identity in several areas. To some Greeks of this period, anti-Persian sentiment was driven by the physical consequences of the conflict—war casualties, ruined cities, and desecrated sanctuaries. Ostentatious opposition to Persia was useful for poleis with imperial aspirations, notably Athens, a tool that could be deployed strategically and, apparently, without fear of its obvious hypocrisy.14

Some of the Phoenician city-states were, of course, deeply involved in this conflict from the time Cambyses created a navy out of his maritime territories. Our only sources for their involvement are Greek, and they have the familiar terminological and conceptual problems.15 Herman Wallinga argues that Cambyses created the fleet, likely in response to the invention of the trireme and its potential to add to the strength of the Saïte navy. Our sources report that Phoenician naval service for the king began with his mostly successful Egyptian campaign in circa 525. Phoenicians were active in the war against the Greeks as early as the battle of Ladē in 494 (Hdt. 6.6, 6.14). They constructed one of the bridges over the Hellespont (Hdt. 7.34) and appeared at key battles, including Artemision (Hdt. 7.89), Salamis (Hdt. 8.85, 8.90), and Eurymedon (Thuc. 1.100; they were dismissed at Mykale according to Hdt. 9.96). In Herodotus (3.19.3) one gets the impression that Phoenicians make up most of Cambyses’s fleet or were the most important part of it.16 Phrynikhos’s 476 Phoenissae—for which Themistokles was chorēgos—shows that Athenians thought Phoenicians made up the bulk of Xerxes’s navy, too. Thucydides refers to the Persian navy as simply the “Phoenician fleet.” Yet a Corinthian war monument erected on Salamis names both Persian and Phoenician ships,17 and we have testimony of the use of Greek and Egyptian ships as well (such as Hdt. 3.13.1, 3.14.5, 5.33.2; Diod. Sic. 11.3.7, 11.17.2).

The fleet was part of the ongoing naval conflicts with and among Greeks throughout the fifth century (e.g., Thuc. 1.110, 1.116), even operating as an extension of Spartan power through Sparta’s alliance with Tissaphernes in the Peloponnesian War (e.g., Thuc. 8.87–88). And yet, Phoenicians were rarely the specific focus of Greek antipathy in literature or in art, even in Athens where naval defense formed the basic justification for its empire.18 (We can recall that Herodotus claims it was the Persians, not any Greeks, who blamed Phoenicians for the wars.) In this respect Phoenicians were similar: there are no examples in text or in art that I am aware of expressing antipathy toward Greeks. This does not mean, however, that the Achaemenid campaigns in which the Phoenicians participated left them feeling neutral toward Greeks. Greek sources indicate that the Phoenicians suffered some very heavy losses. These conflicts could have contributed to a Phoenician sense of collective identity, an idea I explore in the next chapter.

Collective identities can be formed around any kind of common characteristic—class, gender, age, place of birth, language, physical ability, and so forth (for the difficult idea of culture, see Chapter 1). Here the concern is what was Greek or Phoenician, individually or collectively. The question, however innocent, presupposes that these categories were significant in antiquity. There is some ground to cover first. It is prudent to begin with questions about what we mean by terms such as Greek and Phoenician: What kind of identity do they signal and what do they exclude? How are they meaningful labels of groups of people? And to what extent can we associate those terms or groups with art? The discussion that follows considers how scholarship arrived at general ideas about Greek and Phoenician identity—about Hellenism and what I call, after Jo Crawley Quinn, Phoenicianism.19 Neither of these identities should be confused with ethnicity, as both could encompass more than one ethnic group. But neither are these synonyms for culture, as there are many who participated in Greek or Phoenician cultural spheres that were little concerned with Hellenism and Phoenicianism. Rather, taking a page from ethnic studies, and from those who believe in the self-ascription of ethnicity, I understand each of these terms to refer to a conscious collective identity that draws from both social (artistic, linguistic) and ethnic (religious, kinship) identities but is not synonymous with either.

The path to understanding art’s expression of Hellenism or Phoenicianism takes us through some tricky, but important, territory, beginning here with the roles played in classical scholarship by ethnicity and its difficult conceptual companion, race. We begin with ethnicity, as it has a clear ancient pedigree. Ethnicity comes from to ethnos, “band,” “tribe,” “people,” “flocks (of animals).” It signaled a self-conscious and subjective expression of a commonality, sometimes coexisting with polis identity, and sometimes on a still greater scale (as Thuc. 1.18).20 It follows that an individual could have multiple ethnicities: according to his or her deme, polis, region, or tribe, with regional ethnicities being by far the most common.21 These ethnicities shifted, sometimes according to ephemeral factors such as an individual’s location. So Alcibiades might be “of the Skambonidai” in Athens but simply “Athenian” when abroad.22 In the oft-cited passage in Herodotos (8.144.2), Athenians define “to Hellēnikon [ethnos]” as common blood, language, religion, and customs. This description is deceptively straightforward, particularly when cited outside its rhetorical context. The varied usages of ethnē in Greek literature defy a single definition, not least of all within Herodotos’s own history.23 An ethnos might take shape for a variety of reasons. It is popular now to think of ethnicity as a largely aggregate ideological phenomenon that centers on perceived sameness and difference, some of which was not particularly historical. As mythical kinship was an important part of the ethnic group, the basis of a given ethnos was grounded in fictions and memories expressed through, to cite two examples, toponyms and rituals. Ethnicity could be expressed also through the material record that concerns us here, in dress and hairstyle, prestige goods (sometimes imported), symbols, and cuisine.

However appealing the open-ended idea that ethnicity is an expression of commonality over time—what can be called, generally, a common past—it is a very difficult thing to observe. Moreover, ethnic markers are unstable. Greek speech, as discussed in Chapter 1, may have been an important marker of a growing sense of Hellenic ethnicity in the Archaic era, but by the Hellenistic period, it does not reflect even a collective identity. Not only did ethnic markers vary because of changes over time or space, they varied also through deliberate manipulation in order to gain particular advantage. Ethnicity formation was a continuous and subjective process with constantly shifting criteria, which makes its study both very compelling and incredibly difficult. We cannot fully reconcile the existence of ethnē against the imprecision of the term “ethnos” and the ambiguity—sometimes apparently deliberate—of the ideas underpinning it. Of the many scholars working on ethnicity, few approach the topic in the same way or value the different kinds of evidence equally—notably, the archaeological evidence.24 When Isokrates (Paneg. 50) claimed that the name Hellene was no longer a designation of ancestry (genos) but had become a way of thinking—a system of education (paideia)—he seems to challenge the idea that ethnicity and culture are independent.25 Although these tensions are not the subject of this book, I believe that ethnicity can be expressed through the material record even though ethnicities are not stable “culture-bearing units.” There is no such thing as a stable ethnic style.26

In contrast to ethnicity, the term “race” is not Greek in origin, but it is nevertheless very important to our understanding of ancient people. The etymology of “race” prior to the fifteenth century is disputed. It is widely believed that the concept of race was not known in antiquity, which makes race’s prominence in classical scholarship that much more intriguing. The term appears in a few key places. In the LSJ, “race” is offered as a translation of genos, a definition familiar from the word “genocide” and a translation used frequently in modern scholarship, such as the Hesiodic “myth of the races” in Works and Days.27 While the term and concept of race are apparently modern, the use of race to discuss ancient Greek identity might be justified, to some extent, by the biological aspect of ancient Greek self-perception. As Herodotos (8.144.2) and Isokrates (Paneg. 50) show, shared blood was a component of the understanding of ethnicity, even when ethnic kinship was used to trace an ultimately fictive lineage.

Clearly the Greek understanding of these ideas was quite entangled. Yet ethnos and genos were different, and both might be important to collective identity. Modern scholarship would seem to distinguish the two terms more precisely, with ethnicity expressing who you think you are in a subjective manner and race/tribe/people indicating what you are in a primordial or biological sense. But the entanglement of these ideas is a major component of modern scholarship as well, one that is dangerous to ignore, since the idea of clearly bounded races is unscientific.28 It is because of these problems, not in spite of them, that I agree with Denise McCoskey’s claim: “The concept of race remains essential to the study of antiquity.”29

Most investigations of collective identity that concern ancient Greeks and Phoenicians engage race on some level, even, or perhaps especially, when essentialism is not overt. The tendency to view Greeks and easterners (“Orientals”) in axiomatic terms is explicit in art history classifications. The field’s desire to move past the idea of Greece as the birthplace of Western civilization lags behind its ability to let go of or challenge concepts rooted in Greek exceptionalism. Hellenization is explicitly about the power of the Greek origins of things, whether a stylistic and cultural superiority or, I would argue, a tacit biological one. To call a group “Hellenized” is to imply the existence of a people that is very close to a Greek one but is still, at its core, somehow not identical. In the perceived difference between a Greek and, say, a “fully Hellenized” Phoenician, I do not detect a difference in subjective collective identity but rather detect a categorical difference, one that seems difficult to distinguish from the kind of essentialism that drives the theory of race, and one that dredges up the unfortunate traditions of anti-Semitism and Orientalism in classical scholarship.30 This is not to deny the adoption of Greek things and behaviors by Phoenicians, of course, but rather to challenge the way we characterize that adoption as change that is simultaneously fundamental and superficial and altogether less authentic than the real Greek thing. It does not matter to this way of thinking that very many of these real Greek things are also perceived to have come to Greece from the Levant during the Orientalizing period. While this selective commitment to origins seems to contradict the field’s clear shift to discussing Greeks in Mediterranean terms,31 our reluctance to let these ideas go is revealing.

I believe that “Greek” is often employed in an essential or racial sense. Greekness is associated first and foremost with language but fleshed out with a certain flexibility in geographic range and the various qualities associated with culture that still somehow draw a hard line between it and non-Greekness. Ancient Hellenes only very rarely saw themselves this way, as a group defined by certain unchangeable characteristics. “Greek” is also used in modern scholarship to signal an ethnicity, that is, the conscious subjective identity of the Hellene that coexists with ethnic identities on the level of regional, polis, and still smaller scales. It is very difficult to pin down how this idea might have worked, as the maintenance of such a large ethnic consciousness would have required tremendous intellectual effort. It was difficult enough on the level of the polis.32 While the emphasis on paideia to structure identity in Isokrates or during the Second Sophistic comes to mind, those Hellenic identities were clearly class based.33 Surely the differences between Hellenes were nearly always more numerous, apparent, and important than the similarities between them: in common kinship (on many scales), language (dialects do not map neatly onto Dorian or Ionian ethnic identities), and customs (clearly varied).34

Hellenism in other words, was not primordial, nor necessarily sustainable outside political rhetoric and poetic ideology (e.g., Pin. Ol. 10). Further, Panhellenism as a political or religious ideal seems to have been far more important in the Roman era than previously, although there certainly are earlier examples to be found.35 I tend to agree with Jonathan Hall’s claim that Hellenism in his sense of Hellenicity was a supraethnic idea, one that only mattered to some Hellenes some of the time, even while I dispute the idea of a stable “Greek culture.” If Hellenism is a cultural identity, it is impossible to argue that it is fixed or tied directly to ethnicity or geography, which opens up interesting questions about the difference between Hellenism and what we mean by Greeks.

Like “Greek,” and like many other terms we employ to signal ancient collective identities, “Phoenician” is often used in an essentialist, racial sense. Phoenician is a difficult idea for several reasons, a few of which require mention here. The fact that the word is etic and Greek is of course a great challenge (compare the so-called Skythian archer, Plate 6). Modern use of the term is no less fraught.36 The pioneers of Phoenician studies—Renan, Perrot, and others—were unapologetic Orientalists who sometimes expressed ideas that many would now consider racist. Our simple awareness of that fact has been an established part of the academic discourse since Said’s 1978 critique of de Sacy, Renan, and their legacies. Yet it has not changed the way classicists continue to characterize Phoenicia as Eastern by studying it through a colonialist lens. Further complications come from the fact that, despite gradual improvements in our knowledge, many gaps in the basic understanding of Phoenicianism persist, such as when in history Phoenician might be distinguished from Canaanite, or distinguished as a group at all.37 No Assyrian, Achaemenid, Egyptian, or biblical texts settle the matter, either.38 A straightforward example of the confusion can be found in the Peoples of the Past handbook series, in which Jonathan Tubb’s Canaanites and Glenn Markoe’s Phoenicians overlap in time and place even though each author presents his subject as a discrete ethnocultural entity.39

How we arrived at these ideas about Greek and Phoenician needs consideration. From its emergence in the eighteenth century, the field of classical studies, which then encompassed various subdisciplines, pursued with passion the idea of the particular, exceptional qualities of the peoples that inhabited Greece and Rome.40 These qualities might be presented in cultural terms. Yet, as Winckelmann’s pioneering 1764 Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums shows, they were widely understood to have emerged from essential genetic and geographical factors that distinguished Greeks and Romans from other Mediterranean peoples. These studies appeared at the very time human taxonomy became popular and European imperialism was forging qualitative differences between imperial rulers and their subjects.41 Classics is fundamentally teleological,42 and the field was from the start conflated with imperial, nationalist, and racial ideologies that make it difficult to this day to approach ancient Greece in dispassionate terms.

At the same time, it is important to acknowledge classical scholarship’s lasting commitment to exploring the relationships between Greeks, Romans, and their neighbors. Some of the greatest achievements in early art history and archaeology were classifications that underscore the kinds of similarities and differences on which identity studies are based: Winckelmann began the process of distinguishing Greek and Roman art, Heinrich Schliemann (1822–1890) coined the descriptor “Mycenaean,” and Arthur Evans (1851–1941) gave us “Minoan.” Classics has been interested in identity and contact studies long before they had these names.

Persistent interest in the “classical character”43 has taken many forms, however, the lowest and most notorious of which was its use in Nazi propaganda and eugenics. Understandably the racial approach to classical history became unpalatable during this time, as Ashley Montagu’s 1942 Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race forcefully articulates.44 Fleeing the specter of prejudice, other aspects of collective identity such as language became more popular scholarly topics, although often these, too, were—and still are—presented in essentialist terms that fail to distinguish them from racial or other determinisms. A generation later, however, a revised understanding of ethnicity in the field of anthropology yielded a way of understanding subjective and permeable social organization that made ethnic studies legitimate again. The work of Fredrik Barth is critical to understanding this sea change.45 For much of the later 1970s, the 1980s, and the 1990s, studies of collective identity, often characterized specifically as ethnicity, were very much in vogue in classics. Great strides were made in recognizing the subjectivity of Greek history, and interest in the Greek perception of the oikoumenē—barbaroi, “Greek homosexuality,” women, children, and other “Others”—was high.46 Some works focused expressly and carefully on the Near Eastern impact on Greece with great sensitivity to the visual arts.

Despite the success of much of this work, or perhaps because of it, problems arose. Some of this scholarship’s focused interest on Others contributed to a false impression of large-scale static binaries between Greek and barbarian (ethnicities?) that do not reflect well the complexity of the evidence and increasing sophistication of available methodologies. Much of this discussion depends on arbitrary selections of Athenian art, often without addressing their specific approaches to representation. The meaning of the term “ethnicity” and its relationship to identity seemed to become increasingly elusive as these studies proliferated.47 Such problems have arisen from a combination of two powerful factors: the fear or refusal to talk about the extent to which racial ideologies continue to underpin our ideas about the ancient world, and the insufficient attention paid to the point that culture and ethnicity, like race, are theories, not ontological categories. Understandably, there are those who believe that the time for ethnicity studies has passed and who now prefer to speak instead more generally of identity. The term “identity,” too, is rather problematic, however, when it serves merely as a way to elude precision.48

Beginning in the late 1990s and early 2000s, more classical scholars were willing to engage directly the idea of race.49 Again classics was following on broader trends and the increased popularity of other taboo or seemingly passé topics, such as environmental determinism.50 Global politics in this period—the end of apartheid, ethnic cleansing and genocide51 in the Bosnian Wars and Rwanda, the Kurdish independence movement, the Afghan and Iraq wars, the debates concerning immigration and terrorism—have helped race stay in the spotlight. In the United States the fascination with race is persistent even as it maintains its ability to provoke discomfort. Although in 1997 the American Anthropological Association called unsuccessfully for the United States Census to do away with race as a category, the Census and equal-opportunity surveys signal that race and ethnicity are still among the most valued metrics of American identity.52 A similar commitment to and confusion about the meaning of race and its relationship to identity, physical appearance, institutions, and behaviors is an ongoing issue in classics as well, especially in classical art history.

To illustrate these points I will turn briefly to the intellectual setting and reception of Martin Bernal’s three-volume Black Athena series (1987, 1991, 2006),53 which engages many of the very same topics as this book. The first volume appeared nine years after Said’s Orientalism and just four years after the publication of Frank Snowden’s Before Color Prejudice.54 Bernal’s work has clear similarities to both. Although it can be compared to Said’s postcolonial critique of classical Eurocentrism,55 Black Athena, while also very unforgiving of traditional discourse, was not interested in theory. Bernal was a positivist, like Snowden. In Before Color Prejudice and its 1970 predecessor Blacks in Antiquity, Snowden demonstrated that skin-color prejudice was not a feature of classical art. What his argument means in terms of collective identity is rather confused by the focus on skin color, however, because skin color was not a major interest of Greeks and Romans in their perceptions of themselves or others.56 As Snowden admits, while Greeks and Romans were certainly aware of the existence of black skin,57 and of the difference between it and their own, lighter skin color, they did not consider themselves to be, in contrast, white.58

John Dee has shown that Greeks and Romans had no specific vocabulary to describe their own skin color. By contrast he cites evidence that Greeks did not consider themselves “λευκοί by nature.”59 Odysseus is once described as black or at least very dark in appearance (Od. 16.175). Elsewhere Homer describes Achilles shining in his dark bronze armor, an aesthetic comparison that speaks to the visual appeal of bronze statuary.60 White skin was associated sometimes with women as an unnatural feature and with some non-Greek people, such as Persians, who lacked andragathia—manly virtue—as conveyed through swarthiness (see Plates 21 and 22).61 Such passages suggest that both relatively light and relatively dark skin could be remarkable to Greeks. In art, skin-tone colors were varied according to the conventions of the medium. For example, while women were often painted white on pottery, Vinzenz Brinkmann has shown that the skin of korai such as Phrasikleia was painted “a very light ochre brown, or orange-brown” (see Plates 7 and 8).62 Although it began to emerge in the late antique and medieval periods, the idea of “whiteness” did not exist fully before it was invented in the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries in concert with the beginning of the African slave trade and, later, the creation of scientific racism. Whiteness was first understood as a meaningful feature of antiquity only when Winckelmann (1717–1768) mapped it onto Greek ideal beauty and the perfect, unified surfaces of marble sculpture.63

Tanner has pointed out that “no field better illustrates” Bernal’s critique of systemic prejudice in ancient studies than art history.64 As a white Englishman with newly discovered Jewish ancestry, Bernal arguably shared with many others—including at times Burkert, Droysen, Momigliano, and Snowden—an interest in “working out his own cultural issues on the canvas of antiquity.”65 But unlike the texts of any of these other scholars, Black Athena sparked the popular imagination, while much of its scholarly reaction can be characterized as outrage.66 Bernal was trained as a Sinologist, and although autodidacticism is a tradition long established in classics, his work does not rise to the high level of the work of notable amateurs like Michael Ventris (1922–1956). Black Athena is prone to errors of fact and interpretation. It relies on problematic, and by most accounts false, theories of Egyptian and Phoenician colonization of Greece and takes for granted the historicity of debunked ideas like the “Dorian Invasion.” Bernal’s use of sociology is inconsistent; his ideas are often contradictory or opaque. His claim that nineteenth-century classicism was the root of racism in the Western tradition is selective and exaggerated.67 So not only are many of the facts wrong, the approach, too, is poor.

Why, then, did what appears to be a mediocre scholarly project incite such a strong response? Bernal struck a nerve. It is clear that he embraced his status as an alternative historian, drawing inspiration from others who made their own very bold, diffusionist claims on the basis of flawed linguistic and archaeological evidence.68 His project has a deliberately pugilistic tone, and he reached out to Afrocentrists for support for his work.69 These strategies shifted the discourse away from scholarly self-critique and the innovative use of data to position Black Athena and its supporters as judges of the failings of the modern university. The marketing and popular perception of Bernal’s text, more than the obvious weakness of his scholarship, drove his detractors.70 The strength of the response to Black Athena was both more vigorous and more palatable because Bernal was a tenured faculty member at an elite American institution, Cornell; because he had an elite pedigree, his Cambridge degree; and because, unlike most Afrocentrists, he was white.71 Bernal’s “insider” status lessened the sense, to some, that critique of Black Athena was overtly racist or another episode in the so-called culture wars waged between social conservatives and various opposing groups.72

There are also lessons to be learned from the project itself. While the title Black Athena equates a black skin color to Egyptianness, Bernal does not present race as an ontological category. He understood race correctly as an ideological construct. He argued that racism was systemic and might be perpetuated unwittingly, a point that seems to have been missed by some of his harshest critics. For these reasons, his work continues to be useful not only for self-identifying Afrocentrists but also for those who engage the ideological basis of race in order to explore the “institutional patterns and social practices” that contribute to racism.73 Bernal’s greatest contribution might be how openly he showed that race was integral to classical scholarship’s perception of the past—such as the belief in the whiteness of Greeks—when most scholars are content to tiptoe around these issues, preferring to cloak the particular classical “character” in the cover of culture.74

The explanations for the hesitancy to address race head-on are complex. The use of classics in racist discourse is clearly important, but the distaste for race has only increased in recent decades, and not only in classical studies.75 Another is the popular idea that neither race nor racism was part of the classical worldview. The argument underpins both Snowden’s and Bernal’s projects, albeit in divergent ways. Yet it is easily refuted by even a cursory read of the environmentally deterministic Airs, Waters, Places and, according to Susan Lape, the Athenian citizenship law.76 Still another challenge is the fear, one that I share, that the discussion of race will bolster a belief in race as a valid human classification. While recent studies do not try to assert the axiomatic existence of Greek, Ionic, or Athenian races, with some disputing outright the existence of race,77 they do run the risk of revivifying the racial ideologies lingering in the legacy of classicism or perpetuating the unacceptable prejudice in the ancient source material by presenting it neutrally. Benjamin Isaac’s important 2004 study The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity is notable for its care in handling these very issues.

Thus far we have seen that probing the modern terms of convenience “Greek” and “Phoenician” reveals that they rest on some difficult essentialist ideas that have an uneasy relationship with ancient Hellenes and “Phoenicians” and modern racial modes of thinking. Now it is necessary to consider briefly the representational strategies of Greeks and Phoenicians, to describe, in other words, what we mean by Greek and Phoenician art. The discussion starts with Greek art, because it offers, as usual, a richer record. In Greek art the visual expression of identity takes multiple forms, as the arts were used to construct ideal and, to a lesser extent, negative character, both emic and etic. It can be argued that all Greek representation is a form of self-representation, including also art that makes foreigners its subject.

Greeks are not by any means the first people to show foreigners in their art. Monumental Near Eastern and Egyptian art frequently shows foreigners, usually through imagery of conflict, conquest, and propitiation in relief, sculpture, and wall painting.78 Phoenician art is less interested in the subject of conflict between different visually marked people, though examples, such as the Alexander Sarcophagus, can be cited and are discussed in Chapter 5’s consideration of hybridity. State-sponsored art is one seemingly clear context for the expression of collective identity; it could be used to promote civic identity, as seen, famously, in the Parthenon. Of course, not all visual expressions of official civic identity were made on such a large scale; horoi and other inscription-bearing stelai, official weights and measures, and coins were important small-scale sociopolitical markers.

Greek art’s commitment to natural subject matter and animation is balanced by its preference for rich materials, pattern, tendency toward virtuoso display, and use of arbitrary techniques to stipulate its object. Like the use of silver for teeth and quartz for eyes in works of bronze, technē itself ultimately underscored artifice. Conventional symbols (such as Alexander’s anastolē) and denotation (“I am the sēma of Phrasikleia”) were just two of Greek art’s arbitrary representational tools. Our evidence suggests that nearly all sculpture honoring people required denotation—writing of some sort—to identify the honorand, votary, or deceased.79 All of these tendencies indicate that Greek art operated in a manner at once more sophisticated and more ambiguous than mimesis in the Platonic (Resp. 10.596e–597e) or Aristotelian (Poet., Metaph.) sense of copying.80 Here we can recall the value of the kouros as a recognizable type and how the schematic formal approach to the human form seen also in the Classical era’s Doryphoros is a key component of its admiration, both modern and ancient.81

Greek art of the Classical period may be explicitly engaged in the discussion of what it means to represent.82 Monumental anthropomorphic and zoomorphic painting and sculpture were celebrated for their ability not only to please but also to persuade, even fool, the eye by using a combination of anatomical accuracy and implied action. The bronze cow sculpted by Myron and dedicated on the Athenian akropolis in circa 450 was lauded especially for its pleasing and skillful naturalism (Pliny HN 34.57–58).83 Yet even highly naturalistic art was not very much concerned with representing individual objects (see Xen. Mem. 3.10.1–5), unless we believe that Myron’s cow was representing one cow in particular. Nor did naturalistic art have a straightforward relationship with verisimilitude, meaning that some artistic conventions, such as nudity, have a logic all their own, one that is neither internally consistent nor, as discussed in the previous chapter, possible to map directly on Greek behaviors.

The astonishment expressed at such length in the more than thirty epigrams on Myron’s cow, and in Pliny’s description of the competition between the painters Zeuxis and Parrhasios (HN 35.61–66), draws attention to their artists, to their technē, and thence to the pleasing disingenuousness of the works.84 The same can be said for portraits of this period that express simultaneously an individual, a generic archetype (athlete, hero, statesman), and a portrait type (standing male nude, standing draped female). Such thinking allowed reinscription of portraits of even famous individuals with no alteration to the likeness (e.g., Paus. 1.18.3).85 Some famous portraitists, such as the late classical master Lysippos, were especially adept at wrestling specific traits, whether real physical features or deliberately constructed ideal ones, into typologically appropriate portraits that gave the impression or effect of somatic realism.86 The evidence of artists working from live models and casts is first attested in the fourth century, but even then, as with Lysippos’s portraits of Alexander, the final result was very much a manipulation (Plut. Mor. 335b).87

Greek artwork was not necessarily concerned with originality, either, in the sense of the unique—a point to which we will return. The two Riace bronzes, for example, likely either came from the same model or one was cast from a mold made of the other.88 The practices of reusing models and replicating types were standard in both major sculptural media because Greek art was highly conventional. Our difficulty in agreeing on who is represented in works such as the Riace Warriors or the Doryphoros is further revealing of the complexities of representation and underscores how unimportant specific physical features could be to the understanding of what was seen. In both cases, attributes, context, or inscriptions were needed to lend the works the particularity that their highly naturalistic bodies lacked. Naturalistic representations functioned also as symbols and allegories, as, for example, Lysippos’s Kairos, “Point of Decision.” Standing on one toe as if running, stretching its wings, and balancing scales on the tip of a razor blade, the Kairos underscores the intimate relationships between physical naturalism, conceptual abstraction, and meaning in allegorical art. The point is made elegantly in Poseidippos’s third-century epigram in which the statue speaks to an inquisitor.89

Much Greek art is interested in communicating ideal traits, as evinced by the proliferation of certain somatic and character types and themes rich with metaphorical value. Yet Greek art is interested also in contrast—in difference—in both the physical and the ideological sense. The kouros embodies both, balancing its typological consistency with individual poikilia, which together put the world of the kouros in the realm of the aristocratic and divine and at some distance from that of the middling and lower classes. The kouros shows how contact could be a very important contributor to the expression of identity in art. But given the complex relationship between representation and “the real” sketched briefly here, it is somewhat puzzling that works of Greek art, both monumental sculpture and, especially, vase painting, are often treated as documents of Greek observations of historical Others. Representations we know to be fictitious continue to be identified as though documentary, as when the archer in Plate 6 is identified as “a Skythian” through vague associations of costume and character.90 This does not mean that art has no value as a record of physical appearances or behaviors. Rather images, like the written record, are only more pieces of evidence deserving scrutiny. The study of representation, like the study of identity, should not be allowed to languish in essentialism.

The complex logic of representation is evident in heroic archetypes, which, excepting beefy Herakles or child heroes, are usually physically indistinguishable from one another and from humans, contributing to our inability to determine whether the Doryphoros represents a man or Achilles. Memnon is a good example of a foreign figure who was somatically indistinguishable from a Greek (see Plate 9).91 He is a generic, aristocratic hero, his Ethiopian origins suggested sometimes not at all, as in Plate 9, and elsewhere by pairing him with one or more attendant figures with coarse, curly hair and other physiognomic features that recall Egyptian art’s conventions for Nubians.92 He is almost never shown with Ethiopian physical markers, though examples exist, such as the red-figure krater of circa 490–480 where his hair is rendered in relief dots (see Plate 10).93 Rarely is he shown in foreign costume, though we do have the Attic red-figure column krater of circa 450 on which Memnon battles Amazons on horseback while clad in a chitōniskos cheiridōtos, patterned trousers, and Greek helmet.94

As discussed above, color was very important to painting, sculpture, and architecture, yet color was not necessarily naturalistic. The technical limits of black- and red-figure vase painting usually make it impossible to know the extent to which black skin alone sometimes signaled “Ethiopian.” There are a few examples, however, where black is used deliberately for skin color, as on the plastic drinking horn of circa 460 showing a boy battling a crocodile (see Plate 11).95 His black skin would have played off the once-green crocodile and contrasts the visual logic of the red figure on the horn itself. Antiheroes, such as the Egyptian pharaoh Bousiris, on the other hand, could be represented in a variety of non-Greek ways. Miller has demonstrated how Bousiris was shown by Athenian vase painters in different costumes in the late Archaic and Classical periods, from Egyptian pharaoh to generalized tyrant to Persian great king.96 In other words, even when Bousiris’s dress was rendered with specificity, it was not necessarily concerned with ethnic accuracy. There is a kind of parallel here with naturalism.

Already in the late sixth century the long-lapelled cap (kidaris) and patterned costume were generalized as what has been called “Oriental,” “Eastern,” or “Skythian” dress. This costume was used for some Amazons, as seen in the skyphos of circa 510–500 shown in Plate 8, and for Trojan Paris (a rendering common in the later fifth century and ubiquitous in the fourth). Soon these costumes would be extended to a variety of other characters, sometimes inconsistently, as with Andromeda in Athenian pottery.97 The only Phoenician to appear in Greek art is Kadmos, the founder of Thebes and father of the Greek alphabet (see Figure 1). He is never Orientalized. On Athenian, Lakonian, and south Italian vases, Kadmos is shown in standard heroic ways, in full armor or wearing some combination of chitōniskos, chlamys, pilos or petasos, and sandals or boots but otherwise nude. His identity is made clear through inscription or context, usually battling the dragon of Thebes, which is also how he appears in Etruscan funerary art, or sowing its teeth.98 This is the same way Kadmos appears on Roman coins of Tyre.99

It is more difficult still to summarize the approaches to representation in Phoenician art, because, simply put, “Phoenician art” as a category is difficult. Even though objects are on record as early as the 1624 discovery of a terracotta anthropoid sarcophagus on Malta, sustained academic and museological interest in Phoenician art history began only in the mid-nineteenth century.100 From these early days, the corpus of Phoenician art was drawn widely from the Mediterranean and characterized comparatively, often in opposition to the classical. As Vella has suggested, for Grand Tourists and academics such as Winckelmann, “who often made the crossing to Malta from the port of Girgenti (modern Agrigento) after having been to see the Greek temples . . . ‘Punic’ came to represent what ‘Greek’ clearly was not.”101 The idea of a Phoenician artistic style first emerged through study of discoveries of metal bowls by Layard and others. The sometimes dismissive and prejudicial attitudes toward Phoenicians and Phoenician art found in these early publications has persisted, and not only from outside Near Eastern studies.102

The context in which the archaeology of Phoenicia began was likewise colonialist. One must travel to Istanbul and Paris to see the most famous Sidonian sarcophagi. There are parallels here with Greek art history, but a major difference is that relatively few North American and European scholars make the trip to Lebanon and Syria, whereas Athens has some twenty foreign schools and a number of active foreign excavations. A lack of personal familiarity with the terrain, people, and institutions in Syria and Lebanon, and to a lesser extent northern Israel, as well as the ongoing political instability of that region contribute to the idea that Phoenicia is peripheral. Although Phoenician art history and archaeology have developed substantially in recent years, a clear picture of a Phoenician artistic tradition remains elusive.103 Weak support for a collective Phoenician identity in the Greek and Near Eastern textual sources seems to be verified by what remains of Phoenician art, making the use of “Phoenician” to describe a style of art quite problematic. As I claim in the Introduction, the disconnect between Phoenician art history and Phoenician archaeology is one of the most pressing issues facing our understanding of Phoenicianism. Ironically, the problem is quite acute in the Iron Age, meaning that the worked ivory and metal bowls that formed the basis of our initial understanding of Phoenician art are suspect (see Figures 3 and 4).

One clear solution is to deal directly with material that has been excavated in Phoenicia. The archaeological record is poorly known in mainland Phoenicia for the Iron Age, however. While it is tempting to ascribe to lack of excavation the problem of discovering the “true” Phoenician origins of worked ivory and metal bowls, the idea is probably fantastical. We have very little direct evidence of metal working or ivory working on the mainland.104 Published areas of the well-excavated Sarepta (Sarafand, Lebanon) yielded fewer than ten ivory objects, only three of which are figurative, and not even one scrap of a “Phoenician” metal bowl.105 And, as Hans Niemeyer and others point out, neither bowls nor ivories appear in the main colonies, not at Carthage, Malta, Sicily, or elsewhere.106 Even Markoe, the foremost expert on “Phoenician” metal bowls, admitted regarding those from Assyria, “we simply do not know where these vessels were produced.”107 The contrast with widely exported objects from Greek poleis, such as sixth-century Corinthian pottery, is clear and significant. Several other scholars have pointed out the keen problems of settling on sites of manufacture, suggesting the bowls were traded or moved as booty, were made by itinerant craftsmen, or were made in a variety of locations by local craftsmen.108 Each theory is speculative, though the idea that these objects should be assigned to specific cultural or ethnic groups is perhaps the thorniest problem.

Marian Feldman has recently argued that the worked ivories and bowls should not be assigned to specific Syrian or Phoenician workshops.109 She believes that it is so difficult to assign these objects to particular regions because doing so is an academic exercise doomed by the connectivity, decentralized networks, and, as she calls it, “mobility of style” that created demand for ivory inlays and metal bowls among members of a shared habitus.110 In other words, in using the terms “Phoenician,” “North Syrian,” and “Etrurian” to classify these objects, we have, in effect, fixed imperfect evidence into false categories, presenting cogent ethnically and geographically determined groups for objects that were in fact produced in a number of locations that cannot be divided ethnically or geographically according to their findspots, styles, or iconographies.111 For Feldman, following Bourdieu’s idea of taste, “style constitutes community identity rather than simply reflects it.”112 She argues that the ivories are best called generally Levantine, although she does not, of course, deny that stylistic differences within them are apparent and important. With the bowls, the very objects first used to identify a “Phoenician style,” even that loose Levantine designation is probably too narrow. Vella has arrived at a similar conclusion, reframing the metal bowls as “boundary objects” composed of the “encoded knowledge of connections between landscapes and practices far and wide, bridging old traditions and dissimilar places.”113 I agree that the impetus for the metal bowls and worked ivories was most likely ongoing Mediterranean contact in a fashion comparable to the Lyre-Player Group seals and foreshadowing the Hellenistic picture mosaic. Assigning manufacture of these objects to phantom Phoenicians seems spurious.114 Even if we are to do so, we cannot argue that such objects were important to them: we do not have evidence that Phoenicians used them.

If we are to cleave these objects from Phoenicians, what remains of Iron Age “Phoenician art”? One class of excavated object that can be associated with the “incipient Phoenician culture” of this period is bichrome pottery, which is succeeded by black-on-red and, later still, red slip (see Plate 1).115 These objects are not made exclusively on the Phoenician mainland, however, and do not continue seamlessly, or at all in some cases, into later periods. Circulation of pottery and change in ceramic production is, of course, natural even if it frustrates efforts to isolate Phoenicians in the archaeological record. There are still more challenges.116 Several key sites, such as Arwad, have not been systematically excavated (see Map 3). Others, such as Tyre, have impressive but uneven excavations owing to dense modern occupation. In Tyre’s case, the modern city stretches from the mainland over the mole originally constructed by Alexander in 332 and onto the former island. So while exposure of Roman and later periods is fairly extensive, the best published information to date about the Iron Age city comes from a sounding.117 It is not unusual to see scholars summon images and descriptions of Tyrian tribute to the Assyrians to flesh out this picture, but it is not possible to use these sources to separate items of Tyrian manufacture from other amassed wealth.118

Sidon likewise has dense modern occupation limiting archaeological activity, although the ongoing “College Site” excavations carried out by the British Museum in collaboration with the Department of Antiquities of Lebanon have contributed much to our understanding of the city. Some impressive finds—such as a forty-meter-high mound of used murex shells for the making of purple dye—offer a window on to what was once a great center of commercial activity. Most impressive of all in Tyre and Sidon are the cemeteries. Tyre’s al-Bass cemetery has yielded a number of inscribed and iconic Iron Age tombstones of nonelites.119 South of Sidon is the Dakerman cemetery with hundreds of tombs dating from the Bronze Age to the Roman period. Recent excavations at Beirut have added to our poor knowledge of the early city, including the tenth- or ninth-century glacis. At Sarepta, a shrine was excavated that dates to the second half of the seventh century. Offerings were presented on a table near a cutting thought to be for an incense altar or standing stone (in this case, a cut stone) that seems to have been associated with the cult of Aštart.120 More than any other major city-state, Byblos has produced very impressive finds, especially from its Bronze Age tombs and its “Obelisk” and Ba‘alat Gebal temples that continued in use into the Hellenistic period.121 Iron Age Byblos is still poorly understood, however, even though this period coincided with the city’s greatest power.122

In sum, we do not have a clear picture of what these city-states looked like in the Iron Age, although we have a better understanding of mortuary spaces and sanctuaries. Finds include the aforementioned Cypro-Phoenician pottery as well as figurative terracottas and masks, the occasional carved ivory or gold object, imported Greek pottery (especially at Tyre), and very few monumental objects. These include the sarcophagus of Ahiram of Byblos (thirteenth century or later; the inscription is tenth century), the relief of a storm god from ‘Amrit or Tell Kazel (ninth or eighth century), an eighth-century Egyptianizing striding figure in high relief from Tyre, and the statue of Pharaoh Osorkon I given to Eliba‘al of Byblos, the last certainly a gift imported from Egypt.123 By comparison to these monumental arts and elite offerings, nonelite Iron Age funerary stelai can seem cohesive. Fifty-two stelai from the Khaldé (near Beirut), Dakerman (Sidon), Tell el-Burak (Sidon), and al-Bass (Tyre) cemeteries were recently surveyed by Sader.124 These are generally crude affairs bearing inscriptions and simple linear decorations: ankhs that may or may not be related to Tanit (discussed in Chapters 2 and 5), crescent moons, disks, uraei, heads, standing stones, and other symbols. Those that could be dated on archaeological or paleographic grounds range from the tenth to the sixth centuries, which fits well with the chronology of the Tyre al-Bass cemetery proposed by its excavators. The distribution of the stelai is, however, erratic, with none coming from north of Beirut—so, none from Byblos—and with the largest cemetery of all, Dakerman, yielding only one, compared to the many from al-Bass. The Iron Age tombstones might be a mostly Tyrian phenomenon.125

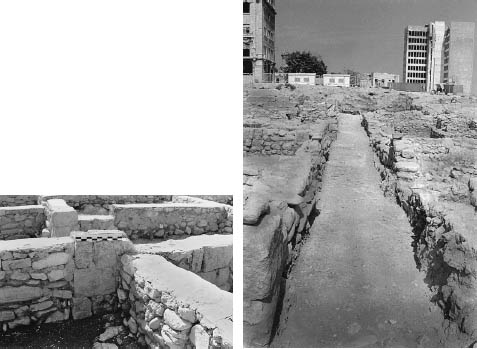

Our understanding of the archaeology of mainland Phoenicia in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman periods is usually better, if still woefully incomplete. Excavations at Beirut have revealed whole Persian period insulae (Figure 17).126 Sidon’s Persian and Hellenistic elite cemeteries of Magharat Abloun and ‘Ayaa once held the looted Egyptian, anthropoid, and relief sarcophagi. Near Tyre, Kharayeb’s Persian and Hellenistic sanctuary deposit yielded more than a thousand terracottas.127 The Persian and Hellenistic sanctuaries at Umm el-‘Amed and Bostan esh-Sheik (near Sidon), both of which are discussed in the next chapter, were loaded with dedications of different genres, techniques, and styles. At the other extreme of the mainland is ‘Amrit, the mainland port of Arwad, well known for its Persian and Hellenistic remains.128 Its most famous finds are a sanctuary, two monumental stone tombs, and smaller naiskoi. No pre-Roman Phoenician temple is better preserved than the so-called Ma‘abed, a porticoed courtyard with a stone shrine at its center set in basin cut from bedrock (Figure 18). A nearby offerings pit contained hundreds of fragments of limestone sculpture. Although some scholars are keen to privilege various external influences on its design, the sanctuary is demonstrably Levantine.129 The statues from the offerings pit that could be typed, however, are Cypro-Archaic.

Figure 17. Domestic quarter at the port/souk excavations of Beirut, sectors A and D. Photo: after Élayi 2010, figs. 4 and 6.

Even this brief look at archaeological remains suggests it is unwise to attempt to circumscribe Sidonian, Tyrian, or other architectural or artistic styles, and incredibly difficult to assemble even a general “Phoenician” one.130 We are not yet able to delineate precise phases of artistic activity in Phoenician art history, and archaeological remains are inconsistent from site to site, making it is nearly impossible to talk about developments over time across genres. Rather, we must look within them. First, there are some architectural features and decorations that are found in disparate sites from the Iron Age and well into the Hellenistic period, such as crenellations and uraei, as well as the ashlar pier wall construction technique (seen in Figure 17).131 The Yehawmilk and Umm el-‘Amed stelai (see Figures 19, 33–34), and Egyptianizing/Phoenician and Cypriot/Cypriot-type sculpture in the round from Sidon, Umm el-‘Amed, and ‘Amrit (see Figure 32) show that there were many approaches to sculptural representation available at around the same time in the Phoenician mainland, even among the Sidonian elite. Only certain genres of sculpture, such as the anthropoid sarcophagi or Aštart thrones,132 are unique to Phoenicia or Phoenicians, the former including Punic areas.

Figure 18. The sanctuary at ‘Amrit. Photo: Jerzy Strzelecki, available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License.

From there things get more difficult. There are the genres of art in which Phoenicians might have played a role that should be instead understood as generally Levantine or broader still, such as the worked ivories, metal bowls, Lyre-Player Group seals, painted ostrich eggs, and carved tridacna shells. There are other artistic traditions to which Phoenicians are thought to have contributed that includes glass, faience (sometimes imitation faience), and metal amulets, scarabs, and other seals; metal and terracotta figurines and masks/protomes/plaques; ceramic and bone vessels and small objects; and a variety of metal objects from gold jewelry to bronze votive razors to silver coins. Although imported painted vases, primarily from Athens, are a component of the Phoenician material record from the first half of the fifth century, there is no contemporary Phoenician figurative pottery tradition. (Some painted ostrich eggs have anthropomorphic features.) Traces of color are found on reliefs, naiskoi, and monumental sculpture, and Hellenistic era tombs show that at least by that time wall painting was part of Phoenician art, but it is difficult to know how extensive the monumental painting tradition was.133 “Tyrian purple” was, of course, famous (Pliny HN 9.127), although archaeological evidence shows that other people made blue, red, and purple dye from the murex snail.134 Garments woven from dyed fabrics might have been finished at the point of final sale, so they cannot be associated absolutely with Phoenician craftsman. There is no evidence of illusionism in Phoenician art before the later Hellenistic era when it is found in, for example, a few preserved mosaics that can be associated with Phoenicia or Phoenicians, such as the dolphin mosaic at Delos discussed in the previous chapter (Plates 4–5).

There are some observable similarities to Greek art that are probably coincidental. For example, Phoenicians are thought to have put a premium on rich materials, but Phoenician art had a lively tradition in the cheaper ones, especially terracottas. Both artistic traditions are anthropomorphic, sometimes schematizing the human form, sometimes exploring it naturalistically, and nearly always relying on iconography, context, or inscriptions to identify individuals. Both traditions valued pattern (and presumably the skill it took to achieve it) and made judicious use of symbol (such as the ankh and caduceus) and allegory (such as the Master of Animals). Both have a tradition of aniconic representation as well. In sum, we do not yet have a handle on what constitutes a Phoenician style of art or what belongs or not to Phoenician art history.

A few different approaches to art from the Persian-Hellenistic periods are currently being explored. Some publications concern the scientific presentation of excavated material, as in the aforementioned work of Sader. Rolf Stucky’s publications of the Eshmun sanctuary at Bostan esh-Sheik are invaluable for our overall understanding of the site and for organizing the approach to specific monuments. Stucky is interested in culture contact, but he neither takes a critical approach to the idea of “Greek influence” nor to the terminology we use to distinguish Greek from Near Eastern.135 Katje Lembke’s monographs of the anthropoid sarcophagi and sculpture from ‘Amrit are essential reading.136 In both, she stresses the gathering of information from archaeological context, especially important with art resistant to easy stylistic analysis, as well as scientific testing. Like Stucky, Lembke’s interest in this material, and in who made what and when, does not necessarily encourage reflection on how we move from style and technique to the ethnicity of the artist. Josette Élayi’s strategy to promote the study of Persian period Phoenicia is relentless publishing. Her work emphasizes Phoenician initiative while remaining fairly conservative in its framing of Phoenicia’s eventual Hellenization.137

Some recent publications pursue new interpretive strategies. Vadim Jigoulov has stressed the importance of treating Persian period Phoenicia as part of the Achaemenid empire, using coin imagery especially to make his case.138 Jessica Nitschke’s critiques of Hellenization ask scholars to pay more attention to what makes sanctuaries and monumental sculpture Phoenician.139 Jennifer Stager’s publication of a Greek-Phoenician funerary stele from Athens (discussed in the next chapter) explores visual and textual bilingualism as well as the importance of Phoenician patronage in shaping art.140 What all of these studies have in common is their focus on objects that were or are thought to be excavated in Phoenicia, or were made or patronized by Phoenicians. Altogether they suggest that the art history of the Persian-Hellenistic periods has a promising future.

Racial and colonial modes of thinking led directly to the construction of Greeks, Phoenicians, and their art histories in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Yet these modes are not located only in the past; they continue to encourage resistance to structural changes in thinking about their subjects. Art history from the eighteenth century has had a profound impact on ideas about the Greeks. Winckelmann’s work on Greek art was an important expression of emerging Western values, qualities that were lacking, in his opinion, in Egyptian and Phoenician art.141 The consequences of this mindset are arguably greater still for the way we have constructed Phoenicia and its artistic traditions. It will not do to call Phoenicia “a Mediterranean state of mind”142 or to use “Phoenician” to describe a category of objects that coalesce loosely around the coastal Levant and the objects conveyed by “men in boats.”143 Such perspectives do not fit even the limited evidence we have, and they serve to reduce the idea of Phoenician culture to Orientalism itself.144

Important as Phoenicians seem in the Iron Age Mediterranean, from the development of trade to colonization to the transmission of culture, we do not really know who they were or if they were as a collective entity.145 They did not seem to share a pantheon.146 Of the more than forty mentions of Phoenicians in Herodotos, only one or two seem concerned with a region in the Levant. We cannot be certain that even Greeks had cause to view these people collectively, although when they did so, the reasons seem to have been linguistic. In Near Eastern sources we find more persuasive evidence of some of these same people using a common language and associated with maritime prowess, control of strategic ports, and natural resources. Domination of some city-states over others is attested, as in the ninth century when Tyre’s power grew under Ithoba‘al I (r. 887–856) to eventually encompass Sidon. These episodes might be evidence of political confederations,147 and it is through Tyre’s maritime expansion that use of Phoenician was spread to Anatolia.

What we seem to have in the Iron Age is evidence of what we call, following Greek literary sources, Phoenicians, but no conclusive evidence of Phoenicia as a place or a Phoenician collective identity.148 The existence of Phoenicia as a particular, even if dynamically interpreted, place would seem a prerequisite to the existence of “a” Phoenician culture. In this period, it is one for which we have only tentative evidence. While it might be tempting to dismiss such problems as unfortunate gaps in the historical record, or to suggest that Phoenician history suffers merely from very “limited chronological resolution,”149 I believe it is preferable to avoid creating Phoenicians where none can be shown to exist. To be clear, I do not deny that there were Levantine people who used the language we call Phoenician inhabiting the region from Nahr ‘Amrit to the Carmel coast, nor that these people were involved in trade and colonization that brought them to the Balkan Peninsula and into contact with Greek-speaking colonists in the western Mediterranean. But I maintain that the “Phoenician art” of the Iron Age is an invention of modern scholarship and insist that it does us little good to continue to study ivories and metal bowls as examples of it. Portable objects of course have a place in the discussion of what might have constituted a Phoenician art or visual culture, especially those that come from controlled excavation. Excavated material from Cyprus and the western Mediterranean fits, too, but scholarly emphasis must shift as much as possible to monuments and objects retrieved from Iron Age Byblos, Sidon, Tyre, and other sites to ground future discussions in reality.

Whatever the complex of causes, the archaeological record suggests that something different happens in this region after the significant political upheavals of the later Iron Age. Following the early Persian period, that is from around 530 BCE, we begin to find many more monumental works of art and architecture that can be ascribed without hesitation to Phoenician patronage and use contexts. I think it is both historically tenable and intellectually responsible to talk about Phoenician art and identity in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman periods. The seeds for this development were planted in the Iron Age, but, as I argue in the next chapter, they bloomed after the Persian Wars encouraged sustained, large-scale collective thinking—peer-polity interaction. Literature and coinage of the Roman imperial era suggest that this was not a one-time event, although it is impossible to say whether these were merely episodes or part of broader trend.