CHAPTER 3

From Avignon to Antwerp and from Antwerp to Nuremberg

The ways in which the text attributed to Wilhelm Friess changed from edition to edition run parallel to changes in who was reading it and where it was being printed. Those who published and redacted the prophecy left their marks on the text. By piecing together the history of the text (which will be referred to in quotation marks as “Wilhelm Friess” to distinguish the text from Wilhelm Friess, its alleged author), we will be able to trace how the prophecy entered Germany and understand how a text that was suppressed with the severest penalties in Antwerp could become a popular and openly printed pamphlet in Nuremberg. The textual history of “Wilhelm Friess” provides an example of how texts changed in the context of censorship, in the genre of early modern prophecy, and in the medium of print. By focusing on the details of textual history, we will later be able to attempt an answer to more fundamental questions: where do prophecies come from, and more broadly, how were texts made in the late Middle Ages and early modern period?

From Avignon to Antwerp: Johannes de Rupescissa and “Wilhelm Friess”

That Frans Fraet was printing something incendiary should have been apparent from the fact that the text he printed was first written by an author who spent most of his adult life in prison.1 In the 1330s, Johannes de Rupescissa, a young man of knightly heritage in southern France, began to have visions. Rupescissa described his visions as sudden illuminations of his mind that helped him understand scripture and extrabiblical prophecies, informed him of the Antichrist’s birth and impending appearance, and inspired him to become a Franciscan. Prophesying of things to come was a hazardous undertaking at that time in southern France, which had recently seen several lay and clerical prophesying religious enthusiasts denounced—and, in some cases, burned—as heretics. Rupescissa denied that he was a prophet in the same way that Jeremiah or Isaiah had been, but he did so by quoting the biblical prophet Amos.2 Rupescissa’s disavowal of the title of prophet did not prevent him from claiming that part of one of his works had been revealed to him by the Virgin Mary.3 Rupescissa was arrested in late 1344 and imprisoned until his trial in 1346. The inquiry found Rupescissa to be not a heretic but a fantast, and he remained confined for most of the remainder of his life. In 1349, during the Great Schism, Rupescissa was allowed to make his case before the papal court in Avignon. While Rupescissa’s imprisonment prevented him from preaching openly, his superiors respected his prophetic claims enough that he was allowed access to books and writing materials and allowed to work, although often under appalling conditions, and some interested observers began copying and circulating Rupescissa’s writings. Despite his imprisonment, Rupescissa read widely and composed an impressive list of his own prophetic commentaries and interpretations before his death in 1366.

In 1356, Rupescissa summarized his prior prophetic work in a short tract entitled Vademecum in tribulatione (Walk with me in tribulation). The Vademecum was soon known to readers in and beyond Avignon, and it eventually dispersed throughout Europe in various forms and in both Latin and several vernacular languages. Rupescissa divided his work into twenty sections or “intentions” that sketch out the primary events and actors of the end-time, including the rise of false prophets and Antichrists of the east and west, the purification of the clergy through poverty, and then the overthrow of heresy and other diabolical powers through the actions of righteous preachers and a final virtuous emperor. The Vademecum is unusually specific in its predictions: Rupescissa foresaw all these events occurring between 1356 and 1370.

The prophecy of “Wilhelm Friess” is considerably shorter than the Vademecum, and the material is treated in a somewhat different order, with many sections being omitted entirely. Comparing the two texts is made more difficult by the lack of a modern edition of the Vademecum. Considering the numerous manuscripts of the original version and many later adaptations in Latin and other languages, preparing a critical edition would be an enormously difficult undertaking. Yet without a critical edition of the Vademecum, one of the most well-known and influential prophetic texts of the later Middle Ages, we are left in the scandalous situation of relying on an edition from 1690 edited by Edward Brown. Even worse, the marginal notes in the printed edition rudely mock Rupescissa, the poor quality of the manuscript consulted, and the incompetence of the scribe who copied it: “All of these things are confused, partly because of the scribe’s flaws, and partly because of the author’s faulty discernment and coarse ignorance,” reads one of Brown’s notes. In another, the editor remarks, “The text is miserably corrupted here because of the exceptional ignorance of the copyist or transcriber: if anyone can make sense of these mangled words, well and good. Reader, take note of how much damage authors suffer when foolish copyists who don’t know how to read old manuscripts try to transcribe their works. The sweetest music of the ass upon the lyre!”4

Despite the inexact correspondences and the unsatisfactory state of the edition, the origin of “Wilhelm Friess” in the Vademecum is beyond doubt, as the numerous parallel passages demonstrate. To give one example, both texts predict an uprising of worms and small birds against larger creatures (134–48, here and in the following discussion, parenthetical references indicate lines from the edition in appendix 1).5 The changes to this passage are similar to the transformation of the text as a whole between the Vademecum and “Wilhelm Friess,” where some sections are reduced to a summary or omitted, others are expanded or have new material added, and entire sections are rearranged. The influence of Johannes de Rupescissa’s prophetic works in Germany is a topic still awaiting intensive study. Until now, the spread of the Vademecum in Germany was only known from a handful of fifteenth-century manuscripts and its inclusion in a number of Latin compilations in the sixteenth century as well as one rendition into German verse.6 By virtue of its appearance in print in nearly twenty vernacular editions by 1570, “Wilhelm Friess” was the most significant route by which the ideas of the Vademecum spread throughout Germany in the sixteenth century.

But the author of “Wilhelm Friess” was not working from the original Vademecum. The author was not even working with a Latin text. Much of the language not found in the Vademecum that shows up in “Wilhelm Friess” reflects a French redaction that is preserved in one manuscript now found in the Vatican library (BAV Reg. lat. 1728). The opening of “Wilhelm Friess,” with its disdain for those who do not experience trials, follows a preface added to the original Vademecum: “I consider nothing more wicked and unfortunate than when someone lives forever in joy and has never borne suffering or faced opposition,” or as the French manuscript begins, “Ha creature qui tousjours vivre vouldroies en ce monde en prosperité, riche aise, habundant en biens temporeulz et en sa voulenté, sans avoir point de tribulation, encombrement, ne nul meschief ne desolation . . . livré a dampnation.”7

While the Vademecum was highly influential, it was not well organized, and it treats several topics multiple times in various disconnected sections. The French redaction rationalizes the organization by bringing together into the same section material that the Vademecum mentions in disparate chapters, resulting in a more linear narration. In comparison to the Latin Vademecum, Barbara Ferrari calls this French redaction a “true rewriting, characterized not only by additions, deletions, and significant modifications compared to the source, but also by a profound reorganization of the material.”8

“Wilhelm Friess” continued the process of rationalization begun in the French redaction by bringing together all predictions of woe for the clergy into a single section at the beginning of the prophecy. It also omitted long sections while adding its own new material. Despite the differences, the similarity in wording between “Wilhelm Friess” and the French redaction is so close that there is little doubt that they both belong to the same tradition of the Vademecum. Striking verbal echoes are found in the Low German 1558 edition of “Wilhelm Friess,” where the word tribulation is found twice as the rendering of French tribulascion, a correspondence not found in other editions (219, 310). Another remarkable case concerns the clergy’s frantic searching for a place of refuge, which the French text says they will hardly find: “ce que a paine trouveront.” The same Low German edition and two later ones read “a paine” literally and instead foresee the clergy seeking refuge in great pain (“mit groter pyne” or “mit groter smarten,” 67).

The manuscript now found in the Vatican was written around 1470–75 on paper bearing a watermark that can be localized to the Champagne and Île-de-France regions of northeastern France.9 Geographically, chronologically, and textually, the manuscript represents a middle step between the Avignon of the 1350s and the Antwerp of the 1550s. The manuscript was not the direct ancestor of “Wilhelm Friess,” however, as the German pamphlets preserve a few passages found in the Latin Vademecum but missing in the French manuscript. The prediction in “Wilhelm Friess” of terrible earthquakes in Germany, Burgundy, and Spain (276–79) corresponds quite closely to the Latin of the Vademecum, for example, but no equivalent can be found where it would be expected in the French redaction.

Compared to its source, “Wilhelm Friess” often briefly summarizes material that the French Vademecum redaction treats in considerable detail. Beyond this tendency to summarize, “Wilhelm Friess” systematically omits references to Johannes de Rupescissa. The French redaction describes Rupescissa’s life in Avignon and mentions his name, but it usually refers to him as “le Cordelier” (the Franciscan). Other versions of the Vademecum tend to suppress the author’s name in a similar fashion.10 In “Wilhelm Friess,” this was done so rigorously that Wilhelm Friess shifted from the owner of a book of prophecies to their implicit author. The religious battlefield of the mid-sixteenth century was much changed compared to the fourteenth or fifteenth centuries, and the antagonists of “Wilhelm Friess” are different. Unlike the Vademecum in its original Latin or in the French redaction, “Wilhelm Friess” nowhere mentions Jews or faithless Christians. Although “Wilhelm Friess” has nothing good to say about monks or the French, it omits the disasters foretold for specific French and Italian cities and for each monastic order.

“Wilhelm Friess” contains many conventional elements of the standard end-time drama, with some notable exceptions. The rebellion of the common people against their lords begins a series of disasters, including an invasion of Saracens and Turks, pestilence, famine, storm, earthquake, war, and flood that are found in many end-time narratives of the late Middle Ages, as are the false prophets and false heathen emperor who persecute Christians with unspeakable harshness. The two holy men who preach against false prophets and restore the offices and sacraments of the church, as well as the righteous Last Emperor who joins them in establishing peace and extinguishing heresy, were similarly well known. However, the prophecy of “Wilhelm Friess” omitted several other elements that most readers would have expected. Compared to the original Vademecum or to its French redaction, Frans Fraet committed a number of striking sins of omission. “Wilhelm Friess” leaves out some material so consistently that it would seem to reflect the redactor’s agenda. The prophecy omits all mention of Gog and Magog, Enoch and Elias, Lucifer’s fall, the Second Coming of Christ, and the resurrection of the dead. The Vademecum has two Antichrists; “Wilhelm Friess” has none. Instead of Antichrists, the German prophecy describes false prophets and a tyrant from the west with allies in the east. A bishop and emperor bring peace and unity to the world as in the Vademecum, but “Wilhelm Friess” sees the future golden age continuing on indefinitely past the death of each, with suspiciously little to say about what kind of secular or ecclesiastic order will follow. Despite a clear grounding in the Christian end-time narrative, “Wilhelm Friess” seems almost secular and anarchic in comparison to its source. The lack of an impending end of history led Volker Leppin to categorize the prophecy as nonapocalyptic.11 While Leppin’s classification is appropriate for a theological study, the literary and cultural context of “Wilhelm Friess” lies firmly within the tradition of reworking and adapting the apocalyptic narrative. Perhaps “Wilhelm Friess” should be considered an apocalypse of a different kind.

Why Frans Fraet Had to Die

Understanding the source of “Wilhelm Friess” helps make clear what Frans Fraet was doing in Antwerp. While the Dutch astrological prognostications of Willem de Vriese were not used as a textual source for the prophecy of Wilhelm Friess, Frans Fraet may have thought that he recognized an unnamed source for de Vriese’s prognostications in a redaction of the Vademecum. The closest point of contact between the astrological prognostications and Rupescissa’s prophecy is found in their proclamations of woe upon the clergy, where the astrological prognostications are at their most prophetic. The image of clerical humiliation, impoverishment, and flight in the Vademecum redaction is similar to that found in de Vriese’s practicas, although it is also found in pseudo-Vincent Ferrer and other works.

Reading “Wilhelm Friess” against the Vademecum also helps us to understand what may have attracted Fraet to the text and what role he played not only in printing but also in adapting it. Certainly Fraet would have found much in the Vademecum with which he could sympathize, including its eschatological material, its predictions of troubles for the clergy, and its promise of relief from persecution for true Christians. According to Hofman, the whole philosophy of Fraet might be summarized as “evil oppresses good, but good will eventually prevail,”12 a view consistent with the tribulation followed by salvation foreseen in the Vademecum and in “Wilhelm Friess.” The prophecy culminates in a spiritual utopia without hierarchies, where authority for scriptural interpretation and access to divine inspiration are held in common and where no authority can be maintained by resort to weapons of violence.13 Scott argues that the utopian vision of a “leveling of worldly fortunes and rank,” emphasizing solidarity and equality, is typical of the religious convictions of the dominated.14 In “Wilhelm Friess,” it can be recognized as a protest against what Fraet saw around him in Antwerp.

If there were just one reason that Frans Fraet had to die, it is most likely to be found in the prophesied uprising of small birds against the birds of prey. In prophetic literature from the late Middle Ages and early modern period, the eagle had been a symbol of the Holy Roman Emperor and his dominion. The use of eagles and other birds to represent the nobility and their lands did not require explanation or comment in the numerous fifteenth- and sixteenth-century prophecies where they appear. While the eagle itself is absent among the birds of prey that sparrows, larks, and other small birds would attack and kill in great number in the prophecy of Wilhelm Friess, the threat to the Netherlands’ Habsburg regents would have been unmistakable, especially as the uprising of little birds against the birds of prey immediately precedes a prophesied rebellion of the common people against the nobility.15

The allegorical prophecy of birds, beasts, and worms in “Wilhelm Friess” exemplifies the prophecy’s subversive function. On the surface, “Wilhelm Friess” makes use of well-known elements of traditional imperial prophecies, but it turns those elements into a covert critique of imperial power and a veiled threat of rebellion, by creating ambiguity over the identities of the expected Last Emperor and the heathen false emperor, permitting the Habsburg emperor to be displaced from the starring role to that of the villain. In Antwerp, “Wilhelm Friess” was an example of what Scott terms “critiques within the hegemony,” because it turned the empire’s own narratives against Habsburg rule. Traditional symbols were manipulated to create messages “accessible to one intended audience and opaque to another.” If the censors did understand the concealed message, retaliation was complicated, because “sedition is clothed in terms that also can lay claim to a perfectly innocent construction.”16

Certainly Fraet had the rhetorical talent and experience to have been both the printer and the redactor of “Wilhelm Friess.” One might compare his role in printing the prognostication of Willem de Vriese with his editorial interventions in publishing a collection of religious songs, where Fraet not only selected but also corrected, improved, and extended the song texts.17 Fraet may have planned to resolve the conflict between state-imposed censorship and public demand for pro-Reformation literature by printing a pamphlet that appeared to reiterate imperial narratives but, beneath the surface and behind the mask of “Wilhelm Friess,” subverted imperial discourse. Seeing a hidden message in “Wilhelm Friess” is not reading too much into the text: we can be quite certain it was there, because Fraet was executed for it. Whether Fraet was the redactor or only the printer, suggesting that lower things might violently end their subordination to higher things was why Frans Fraet had to die.

From Antwerp to Nuremberg

At several critical junctures in the transmission of “Wilhelm Friess” from Dutch into German, the identities, locations, and motivations of those who adapted and printed the text are entirely unknown. For several steps in the path of transmission, our only guide is what happened to the text itself, so we will have to consider the textual history of “Wilhelm Friess.”

Textual history, source studies, and recension criticism are, at their core, arguments based on probability.18 The claims that one text is descended from another or that two texts share a common ancestor say, in effect, that the similarities between two texts are so striking and pervasive that it defies all reason to suppose that the two could have arisen independently. The possibilities of human language are so numerous that no two writers, even if they share personal backgrounds and historical contexts and intentions, would write precisely the same thing.

Yet some texts defy the odds. What seem to be improbable coincidences are made possible by the redundancy found in all languages, a common stock of phrases and literary influences, similar contexts and concerns, and shared knowledge of a traditional narrative. Two editions of the same version of “Wilhelm Friess,” for example, change the impending downfall of the “Christian cities” to the downfall of the “godless cities” (478). While the two editions are closely related, assuming that the change was inherited from a common source or borrowed from one to the other leads to multiple intractable problems, leaving independent innovations, motivated by a common wariness about seeming to predict Christian decline, as the least unlikely, if still unsatisfying, option. That a single change is not completely reliable evidence of shared ancestry is particularly the case with deletions, as shared anxieties about prophesying disruption and uproar could motivate two redactors to independently omit the same passage. The less significant a textual difference is, the more likely it is that it could arise independently. For binary choices—to break a sentence or not, to include an and or not, to treat a noun as a singular or an unmarked plural, and so on—the descendants will probably follow the choice of the ancestor but may choose the opposite, so that apparent similarities with other versions arise without a genetic connection between them. The relationships between the various editions of the most popular version in particular must be determined on the basis of the cumulative probability of a handful of minor distinctions. Our confidence in the reconstructed textual history is necessarily lower, and we must be content with general observations in some places. The least unlikely reconstruction of the history of “Wilhelm Friess” does not account for every similarity or difference, and it is still a history in which a number of improbable things must be assumed to have occurred. The extant editions are only the visible surface of a complex and often subterranean transmission history in both manuscript and print.

Textual history is not always precisely equal to print history, as two different editions might have identical texts, although this does not seem to occur among the editions of “Wilhelm Friess.” The opposite can also take place, where a single edition can have textually significant differences between copies because of corrections carried out during the course of printing. There is one example of this among the editions of “Wilhelm Friess,” where different states of one edition (identified as N16, as described shortly) are the precursors to two textually distinct editions (N17 and N18; see the list of editions in appendix 3 for fuller bibliographic records).

In classical textual criticism, the controlling assumption is that innovations can only be inherited by texts that descend from the innovator. The textual history of “Wilhelm Friess,” however, requires the assumption of multiple contacts between separate branches of the family tree, which complicates the work of identifying and describing the relationships between versions.19 Because of these contacts—“contaminations” in the terminology of textual criticism—and because of the dialectal differences between the known editions and the original Dutch text, it is impossible to precisely reconstruct the original wording. At most, we can say that shared innovations as compared to the French redaction indicate a shared history among versions of “Wilhelm Friess,” either through common descent or by borrowing.

But recovering a lost original is not our aim here. After all, we already have good models of what the original text looked like, in the Vademecum of Johannes de Rupescissa and in the French redaction. Instead, we are interested in discovering what a text meant to those who produced or read it, including both Frans Fraet and his executioners, as well as the translators, redactors, and printers who spread the prophecy to new audiences. For this, both the textual ancestors of the lost Antwerp edition and its German textual descendants help us determine what that edition must have contained. Each later edition had its own historical context and target audience, and we are also concerned with describing them. Every edition of “Wilhelm Friess” is potentially significant.20

The prophecy of Wilhelm Friess is found in four versions, which we will refer to as D (for Düsseldorf, where the only copy is found), N (for Nuremberg, where several editions were printed), L (for Lübeck, where its two editions were printed), and B (for the Bavarian State Library in Munich, where the sole copy is found). Not all versions were equally popular. The versions recorded in one of the Low German dialects of northern Germany, D and L, are known from just one and two editions, respectively. The High German version B is also known from a single edition, while the other High German version, N, is found in fifteen editions printed in or around 1558 and in all seven of the prophecy’s seventeenth-century attestations. All four versions state on their title pages that Wilhelm Friess of Maastricht had recently died and that the prophecies were found after his death. The titles of D and N indicate prophecies for the years 1558–63, B specifies the years 1559–63, and the title pages of the L editions indicate prophecies for 1558–70. That an edition belongs to one redaction or the other is clear in all cases, but the relationships between redactions and between the various editions of the N version are more complicated. Each of the four versions offers unique material, including both distinctive innovations and preservations of wording from the original text.

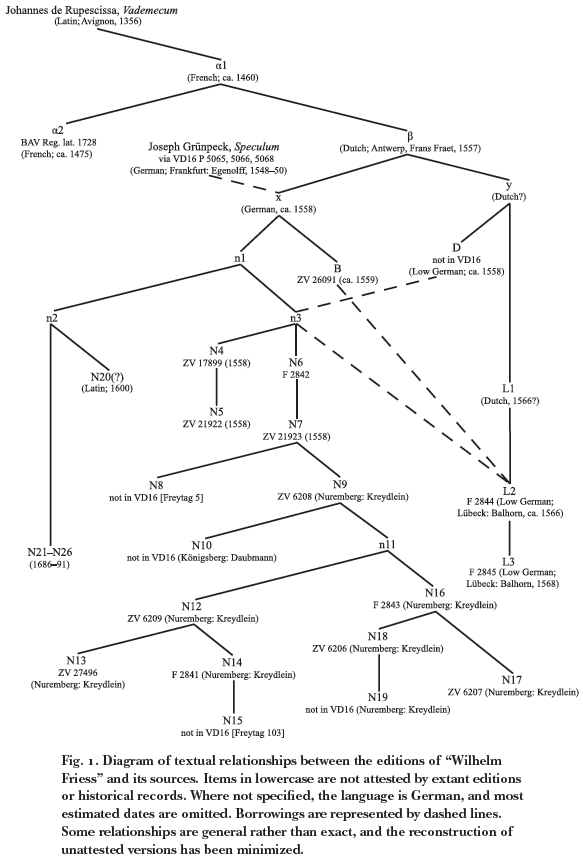

Figure 1 represents the relationship between versions D, B, N, and L, as well as the sources of the prophecy. In the following pages, I will discuss the relationships between texts that are asserted in the figure, as well as areas of uncertainty that the diagram cannot easily express, and I will examine the historical surprises that lurk behind seemingly inconsequential differences between closely related texts.

Version D

This version and version L both appear to be descendants of a common ancestor, which is designated as y in figure 1. Version D is somewhat shorter than the others. It does not include later additions to the text found in the other three redactions, it omits several passages that were found in the source, and a few passages have been moved to new places in the text (see the edition in appendix 1). The Latin mottoes on the title page and at the conclusion, “Fiat voluntas Dei, sicut in coelo sic et in terra” and “Soli Deo honor, nunc et in secula,” which other versions render in German, are curiously similar to the two Dutch mottoes known to be used by Frans Fraet, one for his signed editions and the other for his anonymous ones: “Alst God belieft” and “Gheeft God die eere.”21 As mentioned earlier, several passages that echo the language of the French redaction, preserved only in this version, suggest that it is perhaps only a generation or two removed from the original Dutch edition. To provide an additional example, a passage found only in the D version preserves a rhetorical contrast that has been leveled in the other three versions. All others predict flooding in many cities, with water so high that everyone will be terrified. Two versions, D and B, include an additional emphatic phrase, but only D’s phrasing—every man will be terrified of the flooding “no matter how bold [köne] he is”—yields good sense, contrasting fear and courage. In version B, every man will be terrified “no matter how pious he is”; the contrast has been lost (191). The other versions omit this phrase entirely, although it was found in the original source, with the same contrast between courage and fear found in the D version. The one edition of this version, a pamphlet of four leaves, fills the verso of the last leaf with three additional short prophecies. These include excerpts from the Prognostication for Twenty-Four Years of Paracelsus (actually combining two of its chapters and omitting some inconvenient lines about magica), a passage from the Extract of Various Prophecies (a section originally from Lichtenberger, who attributes it to Cyrillus), and a short Latin prophetic verse about the year 1560.22 The title page of the one D edition uses a decorative element that appears to be identical to one used by the Wittenberg printer Hans Lufft in three editions of 1558–59 (VD16 W 945, L 3452, and L 3345), but the printed text does not match Lufft’s typographic material, so the origin of this edition may lie in the region of Wittenberg but the printer is not likely to have been Lufft.

X: Gnesio-Lutherans and the Polemic Use of Prophecy

“Wilhelm Friess” took a different path into the High German dialects of southern Germany. Unlike version D, which omitted several passages, the common ancestor of versions N and B (which we will call x) preserved nearly all of the original text but expanded it by adding a new conclusion and sharpened and redirected its polemics. The x translation not only repeated the prediction that church prelates would be deposed but also added the gratuitous jab that they were currently living “in all forms of blasphemy and abominable filth,” a parenthetical aside not found outside the N and B versions (69–70). Compared to its exemplar, the German translation tended to indulge more often in superlatives and to engage more frequently in devotional exhortation.

The distinction between the descendants of x and y are most clearly seen in the shared innovations of the y redactions D and L, but there are also a few passages found only in N and B but not in the y redactions or in the French manuscript. The injunction for all who seek mercy to turn their hearts to God, for example, is an intrusion into the text that separates predictions of woe for France and Italy that is found only in N and B (206–8). The text is not so much extended by this passage as it is interrupted by it. The result is a separation of formerly connected thoughts, almost like the drift of tectonic plates, so that new material pushes apart coastlines that were once locked together.

The common ancestor of the N and B versions added a new conclusion (464–503), most of which it borrowed from a text that had already appeared in many German prophetic pamphlets and compilations of the sixteenth century. The passage first appeared in the Speculum naturalis coelestis et propheticae visionis of Joseph Grünpeck (1473–1532), first published in Latin and German in 1508.23 In Grünpeck’s Speculum, this passage forms the beginning of a sermon attributed to a prophet who had recently arisen in France, so the original source of the passage may well be older than 1508. Grünpeck was a humanist and scholar who had risen to a prominent position at the imperial court of Maximilian I before a syphilis infection led to Grünpeck’s dismissal. Following this, Grünpeck authored a number of works that spanned both astrology and prophecy, with the Speculum being his most substantive contribution in that arena.

Grünpeck was a serious student of rhetoric, but the passage as it appears in “Wilhelm Friess” does not give his talents their proper due. In its original form, Grünpeck sets up a striking contrast: “You have begun to be foolish and neglectful in the exercise of virtue, but very wise, cunning, and careful in doing evil.”24 Around 1516, an anonymous redactor compiled sections of Grünpeck’s Speculum together with passages taken from the Prognosticatio of Johannes Lichtenberger (ca. 1440–1503). The Prognosticatio was the most successful and influential prophetic compilation from its first printing in 1488 into the sixteenth century, and it was reprinted well into the late seventeenth century. The anonymous compilation, or Extract of Various Prophecies, was immensely popular in its own right, with twenty-one editions between 1516 and 1540 and several more appearances in compilation with other works. A Dutch translation of the pamphlet also appeared (although the date it bears, 1509, is certainly too early, perhaps by several decades).25 The Dutch translation of the Extract of Various Prophecies was not the source of the passage that is quoted in the prophecy of Wilhelm Friess, however. The prophecy instead cites the version found in a series of prophetic compilations published between 1532 and 1550 by the Frankfurt printer Christian Egenolff.26 While Egenolff’s compilation was originally a collection of sibylline prophecies, he began adding other texts to the collection in the early 1530s, including the Extract of Various Prophecies. The process of accretion culminated in a sizable collection of over one hundred leaves that included the Prognostication for Twenty-Four Years of Paracelsus and the complete Prognosticatio of Johannes Lichtenberger, as well as several shorter texts. Grünpeck’s rhetorical contrast of slothful virtue and crafty evildoing survives in the Extract of Various Prophecies, but in the compilations of Christian Egenolff, it was leveled to the simpler form later found in the prophecy of Wilhelm Friess.

The addition of German prophecies is significant because the earliest German editions of “Wilhelm Friess” also preserve an unusual reflex of the Vademecum: an enemies list. The original Latin and the French redaction look forward to the time when “Jews, Saracens, Turks, Greeks, and Tatars” would be converted. The earliest prophecy of Wilhelm Friess instead provided a list of sects that would be reconverted, which was omitted in all but a few later editions, as denouncing other Christians was a politically risky act that furthermore alienated potential customers. In the two earliest known editions of the N version, however, the list of sects remains intact and allows us to pinpoint quite precisely the religious setting of the prophecy’s entry into Germany, if not the geographical location. In one edition, the list includes “Papists, Calvinists, Adiaphorists, and Interemists,” while the other mentions “Papists, Calvinists, Adiaphorists, Majorists, Menianists, and Interemists” (38–40).

The first German readers of “Wilhelm Friess” were therefore not just Lutherans but Lutherans of a particular kind. Following the defeat of the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League in 1547, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V imposed the Interim, a cessation of Lutheran worship that lasted until 1552. While few Lutherans were satisfied with this development, some sought ways to accommodate the emperor’s decree while maintaining Lutheran beliefs. These moderates included most prominently Philipp Melanchthon, who took part in the negotiations and held that compromise was possible on matters that were not essential to faith, called adiaphora (from the Greek for “indifferent things”). Those who held similar views were sometimes referred to as Adiaphorists or Philippists. Other Lutherans—known as “Gnesio-Lutherans,” from the Greek for “genuine”—demanded unyielding resistance to the Interim, rejecting any concession as a compromise with the Antichrist. The disagreement between Philippists and Gnesio-Lutherans initiated a series of arguments within Lutheranism that lasted for several years.27 The Lutheran theologian Georg Major (1502–74), who sympathized with Melanchthon, held that good works were necessary for salvation. Outspoken Gnesio-Lutherans, including Andreas Osiander (1498–1552), Nikolaus von Amsdorf (1483–1565), and Mathias Flacius Illyricus (1520–75), rejected this view as a weakening of the doctrine of grace. In 1552, another theologian, Justus Menius (1499–1558), responded with a criticism of Osiander’s teachings on grace.

The sects listed in the German translation of “Wilhelm Friess,” the “Papists, Calvinists, Adiaphorists, Majorists, Menianists, and Interemists,” thus comprise a list of the theological opponents of the Gnesio-Lutherans in the 1550s. The German translation of “Wilhelm Friess” was not the only time that leading Gnesio-Lutherans had appealed to older prophecies in their polemics. Decades earlier, Andreas Osiander had published German translations of a prophecy of Hildegard of Bingen and, together with Hans Sachs, he had published the cycle of prophetic papal images known as the Vaticinia de summis pontificibus.28

More recently, Mathias Flacius had enlisted Hildegard of Bingen in his polemics as early as 1550, when he published a prophecy attributed to her concerning the papacy’s ruin and the reformation of the church.29 Flacius was born in 1520 in what is today Croatia. His studies brought him to Wittenberg by 1541, where he became an associate of Luther and Melanchthon. Although Flacius’s academic talent was initially rewarded with a professorship in Hebrew, conflict over the Interim with Melanchthon following Luther’s death led Flacius to leave Wittenberg in 1549. His ability and unyielding positions made him a leading voice among the Gnesio-Lutherans, but constant conflicts with other theologians limited the toleration for his presence in any place he stayed for the remainder of his life. After leaving Wittenberg, he held academic positions of short duration in Magdeburg, Jena, and Regensburg before traveling to Antwerp in October 1566 to lead the Lutheran congregation there. Protestant setbacks in the Dutch Revolt forced Flacius to leave Antwerp in February 1567 and travel first to Frankfurt and then to Strasbourg. Even Strasbourg was not a permanent refuge for him, as he was forced to leave Strasbourg in 1573 for Frankfurt, where he died two years later.

At the same time that Matthias Flacius was publishing diatribes against Georg Major and Justus Menius (not to mention against Osiander and Nikolaus von Amsdorf), he included several medieval prophecies in his Catalogus testium veritatis of 1556, a compendium of witnesses for the truth in all centuries of church history.30 Flacius cited as witnesses for the decadence of Catholicism such prophetic authorities as Lactantius, the sibyls, Osiander’s edition of the papal images, Joachim of Fiore, Hildegard of Bingen, Birgitta of Sweden, (pseudo-)Vincent Ferrer, Savonarola, (pseudo-)Methodius, Wolfgang Aytinger’s commentary on Methodius, Johann Hilten, Joseph Grünpeck’s Speculum, Dietrich von Zengg, and the Vademecum of Johannes de Rupecissa.

Flacius’s collection attests what Lutheran readers saw in the Vademecum less than a decade after Wolfgang Lazius had included excerpts from the Vademecum in a pro-Habsburg compilation of prophecies.31 In the reading of Mathias Flacius, the Vademecum was a witness that the pope was a minister of Antichrist, that the cardinals were false prophets, and that the Catholic clergy was facing imminent tribulation that would restore clerical poverty and return clerical wealth to the laity. In Flacius’s view, these things were in the process of being fulfilled.32 We do not know enough about the earliest history of “Wilhelm Friess” in Germany to say that Mathias Flacius was responsible for its translation or publication, but Flacius’s published works provided an opportunity for him or for others to take an interest in prophetic texts such as “Wilhelm Friess,” and we can be certain that whoever did translate and publish the first German version shared both Flacius’s religious perspective and his interest in the polemical use of prophecy.

The early circulation of “Wilhelm Friess” among German Gnesio-Lutherans tells us something about Frans Fraet’s activities in Antwerp. Frans Fraet was hardly a Gnesio-Lutheran and was more likely influenced by both Luther and Calvin, at a time when Dutch Protestantism was in a state of transformation.33 Yet Fraet clearly printed a text with which German Gnesio-Lutherans could sympathize and that they could adapt further for their own uses. Certainly, following the bitter experience of the Interim, a veiled critique of the Holy Roman Emperor would have found a sympathetic reading among German Gnesio-Lutherans. At every stage of its existence, “Wilhelm Friess” continued to be transmitted because it was valuable to those who read and published it. At the time of its first translation into German and its dissemination in Germany, it was a text that spoke to the situation of unyielding Lutheran hard-liners like Mathias Flacius Illyricus.

Version B

While the earliest German translation may have been stridently Gnesio-Lutheran, printing and selling such a work would have been fraught with political and commercial difficulties. Later editions mostly preferred milder rhetoric. The most rigorously moderate of the four versions is version B, a revision of x that omitted several passages and altered others. As a general rule, many prophecies and most astrological prognostications were printed either late in the year prior to or early in the year of the most imminent prediction. This rule of thumb can help establish an approximate timeline for undated editions. Version B foresees an onset of tribulations in the year 1559 and was therefore most likely printed in late 1558 or early 1559, around a year later than the first editions of the D and N redactions and a year after Fraet’s edition. Consequently, several passages in N that refer to the year 1558 have been altered or omitted in B.

Other passages that were changed in version B reflect an aversion to anything that seemed too radical. Where the N and L versions describe uproar in both human affairs and the animal kingdom, version B omits the list of small birds and any mention of their attack on the birds of prey, leaving it to the worms to attack the large birds. Where the original text foresaw rebellion among the common people against their lords, the B version more circumspectly predicts that the “common people will call on the LORD in great reverence” (153–54). (Even the original prophecy of “Wilhelm Friess” was far less radical than the Vademecum, which foresaw the nobility falling to the sword of popular justice; in “Wilhelm Friess,” it is the rebels who will face the nobility’s merciless retribution.)34 Predicting invasion and catastrophe is one thing, but the anonymous publisher of the lone B edition appears to have taken pains to remove suggestions that smaller things, whether people or birds, might rebel against their place in society. Pamphlets that prophesied small things rising against larger ones could easily have been understood as a threat against the hierarchical order of early modern society and may have attracted unwanted attention from civic authorities, and we can imagine the printer of B hesitating to print a text that dwelt too long on that point. In addition, the pamphlet removed the steps that one might take to prepare for the foreseen disasters, whether practical or spiritual, and reduces the ministries of the false prophets, the Angelic Pope, and the Last Emperor, but it adds that the Last Emperor will leave good governors to rule in his place upon his abdication (423). On the whole, version B takes care to avoid anything that might be taken as seditious or that would suggest practical responses to the text, rather than contemplative responses.

What may have been a politically prudent editorial intervention was not, however, a path to commercial success. The B version, which eliminated much of the prophecy’s sectarian polemic, is known only from a single edition. The earliest editions of the N version instead retained and at times even sharpened the rhetoric—for example, by attributing clerical wealth not to the clergy’s benefices, as do other versions, but to their lies and murdering (80–81). It was not the B version but this other descendant of x that became a best-selling pamphlet in Nuremberg and enabled “Wilhelm Friess” to go from Nuremberg out into the world.