CHAPTER 4

From Protest to Propaganda

Establishing the relationship of one edition of “William Friess” to another is a slow and wearisome process in which slight and seemingly inconsequential variations are identified, compared, and categorized. I have reserved most of the details for the appendixes. Even for the brief summary presented here, it can be helpful to keep one eye on the schematic diagram of textual history in figure 1 (in chapter 3). The result of this effort is a view of how the text changed on a fine scale as it was transformed from political agitation, to sectarian polemic, to a commercial ware that could be openly printed and sold—and how it became, almost twenty years after its first printing, a prophecy that demanded a response.

The Tangled History of N

The most frequently reprinted version of “Wilhelm Friess,” the N redaction, split early on into two subfamilies. One of them, the “left branch,” is known only from the latest appearances of “Wilhelm Friess” in print at the end of the seventeenth century, which will be considered at somewhat greater length in chapter 7. Although these late editions altered the text substantially, they are similar in several places to the B version, which suggests that the exemplar for these editions of the 1680s and 1690s was a very early member of the N redaction. For example, where the conclusion of “Wilhelm Friess” warns that tribulation will quickly appear if people do not repent of their sins, both the latest editions and the B version add that the tribulation will quickly appear “upon you” (“über euch,” 483).

Johannes Wolf’s excerpt from the prophecy of Wilhelm Friess in his Lectionum memorabilium, his monumental, two-volume collection of histories, prophecies, and curiosities published in 1600, appears to provide another witness of the same branch of the N version.1 Apart from a short excerpt concerning clerical poverty from the end of “Wilhelm Friess,” Wolf included only the prophecy of woe upon the clergy, rendering what is clearly the N version of the prophecy into Latin and one word of Greek (115). Curiously, Wolf gives the year of Friess’s prophecy not as 1560 but as 1360, and one wonders if Wolf might have been aware of the connection between “Wilhelm Friess” and Johannes de Rupescissa. Wolf’s translation of the prophecy into Latin obscured the features that would make it possible to place Wolf’s excerpt any more specifically within the N tradition—with one exception. According to the French redaction of the Vademecum, the chastised clergy will no longer wear “purple, scarlet, or any other rich apparel.” Wolf’s Latin extract follows this closely (“Praelati Ecclesiarum non serico, non purpura, coccino, bysso, aut aliis preciosis vestibus induentu”), as do the B and L versions of “Wilhelm Friess,” while the editions of the 1680s and 1690s unfortunately omit this passage. The other branch of the N version, however, changes the purple clothing or rich apparel to “velvet, scarlet, or colorful cloaks” (61–63). Wolf’s Latin rendition appears to reflect an older version of the N redaction and, one is tempted to conclude, the same left branch as the late editions, although conclusive proof is elusive.

Curiously, a similar description of the clergy’s new clothes as colorful rather than purple appears in the genealogically distant D version. This and several other shared passages suggest that what distinguishes the two branches of the N family is not the age of the editions but, rather, contact between the “right branch” and the D redaction (or some precursor from the y side of the family; see figure 1) that resulted in the borrowing of several passages into the right branch but not the left. When “Wilhelm Friess” predicts that people will be troubled and frightened, versions D and L, from the y branch, add that the people’s sorrow will be due to “torments and deprivation” (“van der qualinge unde ungenochte” or “van wegen der groten quale unnd ungenöchte”), a phrase that is lacking in the French redaction, the B version, and the left-branch N editions of the late seventeenth century. The phrase has an equivalent, however, in the right branch of the N redaction, where it appears as “trials [literally, “crucifix”] and suffering” (“des Creutzes und leidens halben,” 152). The similar wording of the D and L versions would be difficult to explain if the borrowing had proceeded from N to D, rather than in the other direction. A similar innovation in D that was then borrowed by the right branch of the N version is the remark that the highest bishop would live such a holy life that he would be a “mirror of all virtue” (355–56). Another sign that the right N branch was influenced by the D version can be found in the doubled passages that include the readings found in both versions. The D version predicts that many people will be terrified by famine, while the left branch of the N version predicts that many people will die of famine. The right branch makes both predictions, using awkwardly redundant phrasing: “There will be such awful distress and deficiency because of famine and hunger in all lands that many people will likely die because of hunger and famine, and all people will be frightened because of the famine’s severity” (267–73). Similar doublings can be found in other passages.

If we have reconstructed the genealogy of “Wilhelm Friess” correctly, at least ten generations separate the earliest translation of x into German from the latest editions of the N redaction, all of which most likely appeared during 1558. While the N version was being so frequently reprinted, the text was also changing. Along the way, “Wilhelm Friess” lost some of the sharper polemical barbs. Where both branches of the N version had assailed the wicked emperor of the west for his “tyranny,” an edition on the right side that would become the ancestor to all others (N6) accused him instead of “cruelty,” avoiding the political overtones of an accusation of tyranny (231). On the basis of the typographic material, this edition might cautiously be attributed to the workshop of Urban Gaubisch in Eisleben.2 The next edition in the chain of transmission (N7) reduced the chance of offending possible customers by omitting the list of the Gnesio-Lutherans’ opponents as sects that would eventually be reconverted or destroyed. In addition, where the original conclusion had assailed Christians for casting the word of God into the puddle of filth (“Unreinigkeit”), this edition berated them for casting God’s word into the puddle of disunity (“Uneinigkeit”), which again blunted the prophecy’s political message (470). Some of the latest editions of the N version even avoid referring to Catholic rites similar to absolution and masses for the dead as “other kinds of devil’s filth,” instead preferring the more circumspect formulation “other things of that nature” (368). For “Wilhelm Friess,” becoming printable entailed a long process of adaptation that preserved enough polemical heat to attract readers while removing passages that would strike too many readers or too powerful of observers as subversive. Eventually, the text printed anonymously by Frans Fraet in Antwerp became something that a printer in Nuremberg could openly print under his own name.

The changes that affected the right branch of the N redaction, by far the most popular version of “Wilhelm Friess,” are closer to those treated by classical textual criticism. The alterations in one generation were passed on to the next, which, in turn, introduced new changes that were inherited by later generations. It is possible to construct a chart of textual variants with the original text at the top and the innovations below and with the oldest editions on the left and following generations arranged in order to the right, so that the chart resembles one side of a step pyramid, as each generation is separated from the previous one by a half-dozen, mostly minor variants.

The development of the N version of Wilhelm Friess is unusually well documented compared to most prophecies and other pamphlets of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, although some stages of the process remain obscure. The examination of relationships between redactions and the changes between editions enable us to consider it as a model for the development of prophecies in print. The earliest stages of transmission are characterized by rapid and significant revision by a limited but highly motivated audience that had access to multiple versions of the text. Consequently, the earliest texts are the most variable, as readers intensely studied, compared, and combined different redactions, thereby creating new versions of the text. Translation provided the opportunity for significant changes as the text crossed linguistic boundaries. In later stages of transmission, the pace of change slowed from edition to edition (though the editions may have appeared quite rapidly) as the text stabilized into a form that expanded its popular appeal while avoiding official sanction and that could therefore be printed and profitably distributed to a wide audience.

This type of textual history is reminiscent of “mouvance,” Paul Zumthor’s term for the mutability and instability of medieval texts that became a central concept in the New Philology of the late twentieth century. One might also compare this textual variability to what Joachim Bumke observed concerning medieval German epics, where the most variable texts and most uncertain relationships are found in the oldest manuscripts, while the more recent manuscripts can be much more neatly classified, in contrast to the assumptions of traditional textual criticism. According to Bumke, the greater variability of the older manuscripts is due to pronounced changes in literacy and the use of the written word between the twelfth and the fifteenth/sixteenth centuries, when the youngest manuscripts were copied.3 For scholars influenced by New Philology as well, the variability of medieval texts was a consequence of pre-modern oral and scribal culture. In the case of “Wilhelm Friess,” however, we find much the same kind of textual mutation occurring in print and within the space of a few years during the second half of the sixteenth century. As Bumke notes, textual transmission follows rules that are particular to a given time, place, and context. The complicated family tree of the prophecy of “Wilhelm Friess” is the consequence of a prophetic text that was being intensively read and revised at a dramatic pace before it reached Nuremberg, where it began to achieve a stable form as it was issued from the press of Georg Kreydlein and his imitators.

“Wilhelm Friess” in Nuremberg

One remaining puzzle is why the reception of “Wilhelm Friess” in southern Germany was so different from the bloody trail it left in Antwerp. While Frans Fraet was executed for printing a seditious prognostication, Georg Kreydlein of Nuremberg published at least eight editions of a similar text, usually with his own name on the title page. Kreydlein appears as a printer as early as 1554, but the single edition of that year was not followed by any others until 1558, when he published his editions of “Wilhelm Friess” and seven other pamphlets. The workshop address Kreydlein gave in 1554 and again in 1558—“auffm newen baw,” or “at the new building,” in Nuremberg—is the same as that used by another printer, Georg Merkel, from 1552 to 1557.4 Merkel was briefly imprisoned in 1557 because of conflicts with his wife, Barbara. Barbara Merkel appears as the press’s sole proprietor in 1560, until Georg Merkel briefly resumed business in 1561–62 before his death. To what degree Kreydlein cooperated with Georg or Barbara Merkel and how the turbulence in the Merkels’ press operation affected Georg Kreydlein are unknown, but it is clear that Kreydlein was attempting to establish his own workshop in 1558.

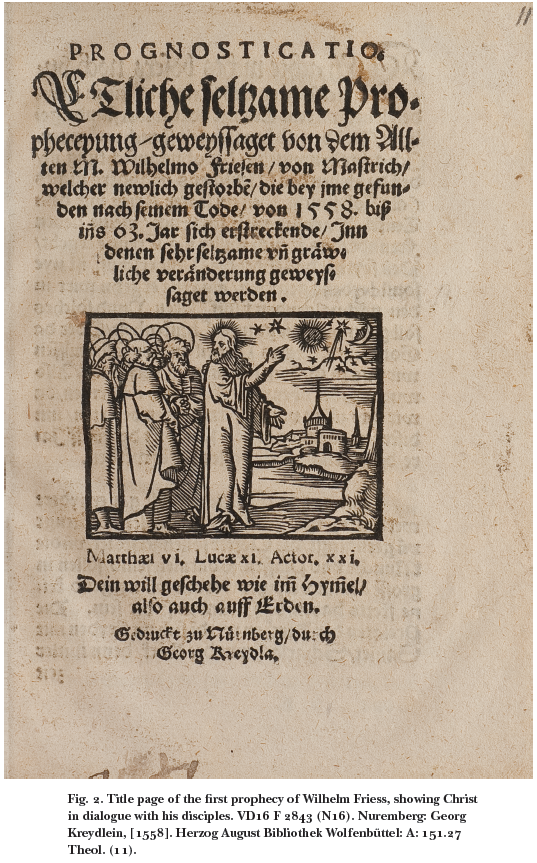

At this critical juncture in his printing career, Kreydlein published multiple editions of only three different works: two editions of a description of the entry of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V into Prague, five editions of a prophetically tinged astrological prognostication for the years 1559–65 by Nikolaus Caesareus, and eight editions of “Wilhelm Friess.” Kreydlein’s editions used three different title woodcuts, all of which show Christ standing with the apostles beneath astronomical signs of the times and against an urban background (see figure 2). In VD16, one of these editions (N14; VD16 F 2841), which combined the prophecy of “Wilhelm Friess” with the astrological prognostication of Nikolaus Caesareus, is dated to 1557, but the dating is certainly wrong. Caesareus’s prognostications for years beginning in 1559 would hardly be printed in 1557, and none of the other nine editions of Caesareus’s work are earlier than 1558. Caesareus furthermore foresaw that the common people would rebel against their rulers but would be violently defeated, “like the peasants in the Peasants’ War [of 1525] thirty-three years ago.” This edition likely appeared in late 1558.5 The catalog of the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel considers this edition to be a possible Erfurt reprint of a Nuremberg edition and dates it to 1558. Kreydlein continued publishing reports of tyranny, persecution, visions, prodigies, funerals, and other standard forms of pamphlet literature until his death in 1561. All forty-five of Kreydlein’s editions, nearly all of them booklets of four to eight leaves, are in German rather than Latin.

In the textual history of “Wilhelm Friess,” the Kreydlein editions form, except for one gap, a compact and continuous chain of transmission from one edition to the next. The editions N16–N19 are particularly similar to each other, sharing a title woodcut, text and decorative types, and much of their page layout. The type was changed significantly during the printing of N16, so that existing copies represent two different states of the type. The differences between later editions indicate only a partial resetting of type, affecting between 10 and 80 percent of the text for N17–N19.

At least two other printers found Kreydlein’s product promising enough to reprint. Johann Daubmann printed an edition under his own name in Königsberg (where the prophecy would also have been able to reach a Polish-speaking audience). Kreydlein’s multiple editions and the rapid reprinting of “Wilhelm Friess” by others are sure indications of a popular and successful pamphlet. Moreover, that there are twelve editions known from a single copy, two editions known from two copies, three known from three copies, and two known from five or more copies suggests that there may be several more editions that have not yet been discovered or that have disappeared entirely.

At the time that Georg Kreydlein was printing his pamphlets, Nuremberg was near the height of its political, commercial, and cultural ascendancy. The city had long been one of the free cities of the Holy Roman Empire, so it was subject to no other sovereign besides an emperor who was usually occupied with matters elsewhere. Territorial acquisitions in the preceding decades had brought neighboring lands under Nuremberg’s control, resulting in the largest geographic extent of any imperial city at midcentury. In addition to its economic significance, Nuremberg was also one of the most important printing centers of southern Germany, with several large and capable workshops operating within its walls. The Protestant Reformation, following the principles of Martin Luther, had been introduced in Nuremberg beginning in 1525, with Andreas Osiander providing substantial impetus. But while an uncompromising Gnesio-Lutheran text such as the earliest editions of the N version of Wilhelm Friess may have found many buyers in Nuremberg, it would not have been tolerated by the city authorities. In 1547, Charles V had soundly defeated the Lutheran nobility in the Schmalkaldic War, forcing their territories to accept the widely despised Interim, which brought Protestant worship to a halt and threatened to end the Reformation altogether. Nuremberg’s civic leaders accepted the Interim just enough to stave off invasion by the forces of the Holy Roman Emperor but attempted to avoid the most contentious compromises with Catholic forms of worship, in order to avoid popular revolt.6 The city’s printers were subject to censorship, and even after the Interim was lifted, the city maintained its position in support of Melanchthon and against the unyielding Gnesio-Lutheran orthodoxy exemplified by Mathias Flacius.

How could a pamphlet that meant a death sentence for Frans Fraet in Antwerp become a best seller for Georg Kreydlein in Nuremberg? The answer is a matter of geography: the meaning of “Wilhelm Friess” changed as it traveled from Antwerp to Nuremberg. If one overlooks the half-concealed sedition of “Wilhelm Friess”—and in Nuremberg, unlike Antwerp, there were few reasons to look for it—the prophecy appears little different from many other narrations of the end-time drama with an anticlerical sentiment that were published in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The actors in “Wilhelm Friess” are the stock characters of the Christian end-time narrative, and the future disasters that “Wilhelm Friess” warns of are entirely stereotypical. It lacks only the specific mention of the Antichrist, who had become a controversial figure that some Protestants rejected as a Catholic legend.7 “Wilhelm Friess” instead contrasts the Last Emperor with a “false heathen emperor from the west” who will “join with those in the east and come down upon the entire land,” where he will “persecute and torment the Christians with utmost cruelty and spare nothing, but rather devastate and destroy everything over which he gains power” (225–33). Unlike the nominal allegiance owed the emperor by the free imperial city of Nuremberg, Habsburg rule over Antwerp was stern and direct, and the geography of the false emperor was profoundly different. In Antwerp, the tyrant from the west with eastern allies who cruelly oppressed Christians could easily be read as a reference to Habsburg dominion emanating from Spain and Austria. It was certainly all too clear to Dutch Protestants that these lands were the source of their persecution. From the perspective of Nuremberg, however, the political geography of the Netherlands was much different. In the “Wilhelm Friess” pamphlets, the only time the Netherlands are mentioned is when the title pages refer to Wilhelm Friess’s citizenship in Maastricht. This city lay not far to the west of Aachen, which was the traditional site of the Holy Roman Emperor’s coronation as King of the Romans following his election and was also where Charlemagne was buried. For the customers of Georg Kreydlein in Nuremberg, Maastricht, once at the core of the Carolingian realm and then, in the sixteenth century, a part of the Habsburg hereditary lands, could serve together with Nuremberg as a point on the central axis of empire.

In southern Germany, imperial propaganda had long sought to connect the emperors of prophecy with whoever happened to hold the imperial scepter at the moment. Frederick III, great-grandfather of Charles V, had been compared to the Last Emperor in the mid-fifteenth century (to cite but one example).8 In Nuremberg, 650 kilometers to the southeast of Antwerp, there was little question that the Last Emperor was a Habsburg (and, hopefully, the current emperor or at least the next one). At the same time, the false emperor from the west and his eastern allies fit the geography of national rivalry with France and anxieties over Turkish incursions. One anonymous edition of “Wilhelm Friess” (N8) encouraged this identification by illustrating the title page with a woodcut of two turbaned soldiers putting children to the sword while a reclining figure looks on passively from his bed. King Francis I of France had been among the contenders in the election that made Charles V the Holy Roman Emperor in 1519, and war with France was nearly perpetual during Charles’s reign. Another constant of his reign was strife with the Ottoman Turks in Hungary, in North Africa, and at the gates of Vienna in 1529. From 1536 onward, France and the Ottoman Turks maintained a strategic alliance that included joint action against the forces of Charles V. In contrast to the printing by Frans Fraet, Georg Kreydlein’s printing of pamphlets lauding the emperor and his victories did not conceal any secret agenda. If it required no explanation in Antwerp that the false emperor with eastern allies could only refer to the Habsburg tyrant, it was equally clear in Nuremberg that only the Holy Roman Emperor could be the righteous Last Emperor of prophecy.

The status of the Last Emperor and other figures of the traditional end-time narrative was not at all clear in 1558, however. Like the Angelic Pope, the Last Emperor was a central figure in what was ultimately a pre-Reformation drama that was, in many ways, out of place in Lutheran Nuremberg. Charles V had begun his reign auspiciously with the 1527 sack of Rome, the very seat of the papal Antichrist in Protestant propaganda, and he had ended his reign as the Last Emperor was supposed to, with a formal renunciation of lands and offices. Charles had announced his abdication in 1556, and it was formally accepted in February 1558. According to the traditional narrative, however, the true Last Emperor was supposed to put off his crown on the Mount of Olives after defeating all heretics and enemies of Christendom. The Holy Land had not been reconquered, Christianity was divided against itself, the Ottoman Turks and other enemies remained a threat, and Ferdinand I had been crowned the new emperor. Clearly, the world was not yet ending. How did the new political reality fit the traditional narrative?

The accomplishments of Charles V in the realm of religion during his reign were even more troubling for Lutherans. While Charles had tolerated the Protestant Reformation in those cities and principalities where he had been powerless to stop it, he had strictly opposed it elsewhere and imposed the Interim on Protestant territories following the Schmalkaldic War. For apocalyptically minded Lutherans, the clash of the true faith with the diabolical enemy had ended not in ultimate fulfillment of evangelical hopes but, rather, in a negotiated settlement. In 1555, the Peace of Augsburg had regulated German religious affairs by establishing that individual territories would follow the religious dictates of their sovereigns.

What made “Wilhelm Friess” such a compelling product for German readers and printers was its insistence on the continued validity of the traditional end-time script at a time of political and religious change. As a new emperor began his reign and a new religious regime was implemented, the unusual specificity of the eschatological timeline in “Wilhelm Friess” forcefully reinscribed the present moment and the realigned political and religious foundations of German and European society into the traditional end-time narrative. As is often the case with printed prophecies, “Wilhelm Friess” was, in a German context, essentially conservative, placative, and optimistic. The prophecy insisted that future political and religious leaders would be wise and righteous men who would rule in harmony with each other, defeat all enemies, and fulfill the collective hopes of German society. For Georg Kreydlein, the hopes and fears of the Protestant citizens of the imperial city of Nuremberg represented a market opportunity that all but demanded something like “Wilhelm Friess.” Frans Fraet had concealed the subversive message of “Wilhelm Friess” so well that the surface message could be taken at face value. The imperial prophecies that had been appropriated to subversive ends in Antwerp were reappropriated to sell imperial hegemony in Nuremberg.

The Restless Ghost of Wilhelm Friess

The success of “Wilhelm Friess” in Nuremberg was a product of how it fit the ideological needs of a specific time and place, but that moment had come and gone by 1560. Almost certainly, all editions of the D and N versions were printed in 1558 and the one edition of the B version by 1559. Although “Wilhelm Friess” continued to find at least some readers into the 1570s, its prophecies for specific years had begun to diverge too noticeably from actual events for it to continue functioning as an interpreter of the present moment.9 In the following years, the prophecy of Paul Severus and the astrological prognostications of Nikolaus Weise for the years up to 1588 took the place of “Wilhelm Friess” in the market for popular prophetic pamphlets.10

The prophecy of the pseudonymous Paul Severus appeared in fifteen editions by 1563, most of which reproduce only the last section of what had been a longer astrological prognostication.11 In several passages, the prophecy of Paul Severus seems to echo “Wilhelm Friess,” including a prediction of tribulation for the Catholic clergy: “The pope and his people will abandon the seat in Rome and flee into the wilderness out of great fear in order to live safely there, and there will be no more pope. Churches and cloisters will also be destroyed everywhere in Germany, and the clergy will be chased out and driven away, and they will have no more benefices, and there will be great lamentation among the clergy everywhere in Germany.”12 A tyrant from the west will oppress Christians in the Netherlands, but God will cast him down. In another scene reminiscent of the conclusion of “Wilhelm Friess,” the prophecy attributed to Severus (hereinafter referred to as “Paul Severus”) foresees misfortune lasting from 1564 until 1570, when a new Reformation will bring about order and good laws and when a righteous emperor in the north will establish peace and reclaim Hungary, Constantinople, and Switzerland for Christendom and the empire.13 “Paul Severus” orients its prognostication with reference to the four cardinal directions more strongly than in “Wilhelm Friess,” and it includes a version of the prophecy that the Ottoman Turks would invade Germany and devastate the land but eventually be defeated. In the traditional version, the climactic battle takes place near Cologne on the Rhine, but “Paul Severus,” perhaps due to local patriotism, foresees that all Germans will gather for battle in Saxony.14 The context and influence of “Paul Severus” remain largely unknown, but it found its way to readers both in the 1560s and later; the astrologer and Lutheran dissenter Paul Nagel borrowed passages from “Paul Severus” for a prophetic work published in 1605.15

It would not be surprising if “Wilhelm Friess” had dissolved into nothing more than an influence on later prophetic texts such as “Paul Severus,” but odd things began happening that attest a prolonged effect of “Wilhelm Friess” on prophetic writing in Germany and the Netherlands. In 1562, when the printer Christian Müller of Strasbourg published an extract of Theodore Simitz’s astrological prognostications for 1563–66, he supplemented Simitz’s work, according to the title page, with “the prophecy that was made by the old Wilhelm Friess of Maastricht about the years 1563 and 1564.”16 The text attributed to Friess begins with a section about eclipses: “Now the evil and shocking years 1563, 1564, and 1565 are coming, for in these years great changes in the empire will occur whose equal has not happened in a hundred years.”16 Several observations concerning upcoming eclipses and planetary conjunctions follow, as well as citations of various astrological authorities on what these astronomic events portend. This text, printed together with Simitz’s prognostication under the name of Wilhelm Friess, was not “Wilhelm Friess” at all. It is not entirely unfamiliar, however. The text was an extract from the astrological prognostication by Nikolaus Caesareus that Georg Kreydlein had printed so frequently and, at least once, together with “Wilhelm Friess.” Other printers had reprinted Kreydlein’s editions of “Wilhelm Friess,” and now a printer was appropriating Friess’s authorship for the prognostication of Nikolaus Caesareus, just as Frans Fraet had once borrowed the authorial name of Willem de Vriese from pamphlets printed by Hans van Liesvelt. One might be inclined to regard Christian Müller’s attribution of Nikolaus Caesareus’s astrological prognostication to Wilhelm Friess in 1562 as a simple oversight on the part of the printer, were it not for the pattern of applying the name of Wilhelm Friess to new texts, which began with Hans van Liesvelt and Frans Fraet and would continue well beyond 1562.

The prognostication of Nikolaus Caesareus that was attributed to Wilhelm Friess has few parallels with the prophecies that Kreydlein had printed in Nuremberg. One does find a passage, however, that is similar to what Willem de Vriese had once written in Antwerp: the frequent conjunctions of Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars will cause the rise of new sects, “great changes in the empire and in matters of religion, devastation of many lands and cities, and the clergy will in truth be sorely attacked.” The upper planets will further “instigate the common people to war and rebellion against their rulers and against the clergy so that they will persecute them with great enmity and rob them of their honors and possessions and harm them.” The end, as already seen above, is foreordained: the rebellion will end as badly as the Peasants’ War had done in 1525.17 Just as the name of Willem de Vriese had once been attached to a variety of texts in Antwerp, the same had now happened to Wilhelm Friess in Germany. Rather than identifying a specific text, the name of Wilhelm Friess was on its way to identifying a type of prognostication at the intersection of prophecy, astrology, and reform.

Wilhelm Friess in Antwerp and Lübeck, 1566–68

VERSION L

The L version of “Wilhelm Friess” is known from two Low German editions printed by Johann Balhorn the Elder in Lübeck. The title pages of the two editions claim to contain prophecies for 1558–70, of which the last four years would be particularly turbulent. Not only do they identify the prophecy as something found under the pillow of the elderly “Wilhelm de Frese,” doctor and astronomer of Maastricht, after his death, but they also state for the first time that Friess was the author of the prognostication as well. The texts of the two editions differ little from each other, but the title woodcuts used very different strategies to attract customers. Balhorn’s first edition used a crude image of a scholar in robes and a cap as its title woodcut, but the next edition opted for a more dramatic scene: amid prostrate bodies, men and women raise clasped hands in pleading toward Christ, who is seated on a rainbow in the sky amid sun, moon, stars, comets, and fiery stars falling to the earth.

The L version has the most complicated textual history of any of the four redactions. It is the version with the most substantial additions and omissions, while still preserving some original passages found nowhere else. Because one of the editions has been misdated, the historical context of these editions has gone unrecognized.

Johann Balhorn also printed his two editions with a disconcerting lack of care. One of the lengthier additions found in the L version concerns the Whore of Babylon from Revelation 17:3. In Balhorn’s editions, she sits not on a red beast but on a “terrible Finnish beast,” a “growsamen fennischen derte” (85). This formulation may be a deformation of the Dutch rozijnverwich as found in the Biestkens Bible printed several times after 1558, which was based partly on the Bible of Jacob van Liesvelt.18 The curious phrase suggests that the sources of the L version include Dutch texts, and it also indicates the modest editorial care and comprehension to be found in Balhorn’s Lübeck workshop. One notes that the German verb verballhornen, meaning “to corrupt or mutilate a text, especially through well-intended attempts at improvement,” arose from a disastrously edited book printed by Johann Balhorn’s son.19

All versions of “Wilhelm Friess” retain traces of its original geography. Even in translation, the false emperor of the west and his eastern allies come down upon the land (niderwartz), that is, toward the Low Countries (228). One of the lengthy passages added in the L version contains the prediction of pestilence in averland (37), the higher elevations found in Germany, again reflecting a Dutch geographical perspective and suggesting that the substantial additions to “Wilhelm Friess” found in L were added to the text while it circulated in the Netherlands.

Several features shared with the D version place L firmly in the y branch, including the reordering of a lengthy exhortation to repentance that both versions move from its original location to the position immediately following the advice to store food for five years (47–52). As a representative of the y branch, the L version preserves some material omitted in D. Its prediction that monasteries would be destroyed uses a verb, vordestrueret, that echoes the phrasing of the French redaction, “les abbayes destruira” (56). In the other versions, the tormented clergy confess that their punishment is just. Only in the L version do they say that their punishment is also good, echoing the French “a bon droit” (98). When the small birds assault the large birds, only version L includes not just particular species but also a rendering of the collective term les grans oiseaulx de proie, or “birds of prey” (147), found in the French Vademecum manuscript. The phrase used in Balhorn’s first edition, however, is the nonsensical groff Vögel, which Balhorn perhaps misread from Dutch roofvogel (“bird of prey”; one might be tempted to see groff Vögel instead as a misreading of High German große Vögel, “large birds,” but that phrase does not appear in any of the High German editions). Balhorn’s second edition mistakenly corrected the passage to graue Vögel, or “gray birds.”

The L version leaves us with some unsolvable mysteries. All other versions cite Job—according to the B version, the seventh chapter (21)—that life is a war with the devil. That chapter says nothing about life as a war but emphatically states that life is vanity. Balhorn’s editions assert that life, according to Job, is the devil’s organ works (“ein Orgelwerck des Düvels,” 23). This is nonsensical, but might it reflect an early deformation of French orgueil, or “vainglory,” which the other versions turned into “warfare” (Low German orlog, High German urlog) in order to make sense of the passage? Or is it a late deformation of Dutch oorlog, or “war”? Where the N and B versions affirm that the worms who will attack the larger animals will appear as if one could easily (“leichtlich”) conquer them, as does the French redaction, Balhorn’s editions state that the worms will shine brightly (“licht”) over the earth (139–40). The use of the same root for descriptions that are entirely different in meaning points toward an inheritance from the original source, but the paths by which Balhorn’s worms achieved their luminescence are inscrutable.

In addition to its inheritance from the y branch of “Wilhelm Friess,” the L version borrowed from both the B and the N versions of the x branch. Only the B version omits mention of the little birds and instead states that the worms will attack birds of all kinds (145). The L version borrowed the B version’s innovation, even though it was redundant in the L version. Another passage expresses hope that God would turn aside his punishment if people repent, just as he spared the people of Nineveh, or as the B version puts it, “if we turned ourselves [uns kerten] to virtue.” The L version borrows and distorts the same phrase: “if we convert our hearts [unse herten] to virtue” (31). A telling case of borrowing from B involves the timeline of tribulation. The original text, as seen in versions D and B and the French redaction, had foreseen five years of catastrophe. Version B, printed a year after the D and N editions in 1559, changes the prediction to four years of disaster, which the L version borrowed despite a stated expectation of twelve years of tribulation (165). The borrowing from High German editions probably occurred in Lübeck, as Balhorn’s second edition corrected one innovation in his first so that it read more like the original text of the B version, changing unordentlike teiken, “disorderly signs,” back to the B version’s unerhörde teiken, “unheard of signs” (136). This correction and a few others that make Balhorn’s second edition more like the N version (18, 56) illustrate the complex textual history of printed booklets. A printer like Balhorn who printed a second edition would often have two or more exemplars on hand in the form of the original exemplar and the first edition, making every later edition potentially the result of “contamination” between a prior edition and an older exemplar. Because of this, the fact that one edition has a text more faithful to the original in a few places may be the result not of textual precedence but of reverting to the exemplar through correction.

Version L also borrowed numerous passages otherwise found only in N but not in the D or B versions or in the French redaction, such as the passage foreseeing not just a pestilence, as in the other versions, but one worse than anyone could imagine (184–85). The N and the L versions are likewise the only ones to add that there will be many of the foreseen false prophets (348). Where the D version follows the French redaction quite closely in stating that unrepentant sinners who were not killed in war would die in other tribulations, the N version states that they would be taken from the world in other ways, a formulation that the L version adopted (310). Where the French redaction and the D and B versions describe the Last Emperor’s conquest of the “Holy Land,” the N version refers to it as “das gelobte Landt,” the “promised land,” which the L version borrows as “dat landt van geloffden” (414).

A borrowing from either N or, perhaps more likely, the B version occurred early enough that the L version even preserves more faithfully than any other known edition a few words of the conclusion largely borrowed from Grünpeck by way of Egenolff. The conclusion calls on readers to put on the clothes of repentance and regret (“busse unnd rewe” in the N version), but the clothes of penitence and sorrow in the original (“penitentzen unnd leyd”). Only the L version has a combination of the older wording and the newer, “tehet an dat kleid der penetentien / unde draget ruw und leidt” (479). Those who fail to do so will flee to the shore and call on the water to gently accept them, or, in the original and in the L version, to gently receive their lives (485; “ewer leben” or “iw levent”).

The editions of “Wilhelm Friess” do not offer any single version that is a reliable guide to the original text in all cases. While the N version may be the most complete and overall the least altered, the complicated history of transmission and borrowing between versions means that unique fragments of the original can be found almost anywhere. The L version appears to have translated into Low German a Dutch text that had been expanded since 1558 and then to have extended it with borrowings from two different High German versions of “Wilhelm Friess,” but even Johann Balhorn’s handiwork did not erase all its unique fragments of the original text.

According to auction records now over two centuries old, a Dutch edition of “Wilhelm Friess” was printed in 1566, coincidentally the same year that Mathias Flacius traveled to Antwerp to oversee the Lutheran congregation there. Although no copy is currently known, the Dutch edition was very likely similar to the Lübeck editions: its title page also promised its readers prophecies for the years 1558–70, and it specified that the prophecy had been found under the head of Willem de Vriese (“onder zihn hooft”), just as only the Lübeck editions state that the prophecy had been found under Friess’s pillow (“under synem Höuet küssen”).20 This lost Dutch edition could have been Johann Balhorn’s source, as Balhorn’s first edition was almost certainly printed not in 1558 (as it is dated in VD16) but, instead, no earlier than 1566. Balhorn’s second edition bears the year 1568, while the first has no date. The dating of the first edition to 1558 in VD16 would make sense based on a title page that mentions prophecies for the years 1558–70, but the existence of editions printed in 1566 and 1568 should raise some suspicion about the dating of the first edition, and a look beyond the title page shows that these suspicions are justified. Despite the claim of prophecies beginning in 1558, all references to the years 1558–64 have been removed or shifted seven years into the future. Version L adds a new prophecy that the years 1566–70 will be marked by pestilence, signs, and wonders. The only reference to the years before 1566 in the L version is a prediction that there would be a severe famine from 1561 to 1566 (37). By 1566, this prediction no longer required any special insight: one history of the year 1566 in the Netherlands is entitled simply Het Hongerjaar (the year of hunger).21 In Johann Balhorn’s editions, the terrible reign of the false emperor is much reduced, as are the troubles predicted for France. Following the conclusion of France’s Italian Wars in 1559 with the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis, the prediction of impending war between France and Italy no longer had a place in “Wilhelm Friess,” especially since the growing influence of Protestantism among the French nobility let some Dutch Protestants hope for support from France in the struggle against Habsburg domination.22 Johann Balhorn’s first edition should certainly be dated no earlier than 1566, which makes a source in a Dutch version of “Wilhelm Friess,” perhaps the lost Dutch edition printed in 1566, a distinct possibility. Valkema Blouw surmised that the missing Dutch edition of 1566 was a reprint of Fraet’s edition, but if similar dates of tribulation can be taken as a reliable indicator, the lost Dutch edition belonged to the L redaction and was some generations removed from the text printed by Fraet.23

Beyond the reappearance of the prophecy a decade after its first appearance in print, something even more extraordinary happened with the L editions. Between 1566 and 1568, the prophecy of Wilhelm Friess—or at least part of it—came true.